| New English Word | Meaning |

|---|---|

| A-game | One’s highest level of performance |

| ambigue | An ambiguous statement or expression. |

| Anglosphere | English-speaking countries considered collectively (the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and Ireland). |

| anti-suffragism | Opposition to the extension of the right to vote in political elections to women; the political movement dedicated to this. |

| Aperol | A proprietary name for an orange-coloured Italian aperitif flavoured with gentian, rhubarb, and a variety of herbs and roots. |

| April Fool’s | April Fool’s Day (1 April), a day on which tricks or hoaxes are traditionally perpetrated |

| ar | Used to express a range of emotions or responses, esp. affirmation, assent, or agreement. |

| arr | In humorous representations of the speech of pirates expressing approval, triumph, warning, etc. |

| assault weapon | A weapon designed for use in a large-scale military assault, esp. one used to attack a fortified or well-defended location. |

| athleisure | Casual, comfortable clothing or footwear designed to be suitable for both exercise and everyday wear |

| Aucklander | A native or inhabitant of city or region of Auckland, New Zealand. |

| awedde | Overcome with anger, madness, or distress; insane, mentally disturbed. |

| awe-inspiringly | So impressively, spectacularly, or formidably as to arouse or inspire awe. |

| awesomesauce | Extremely good; excellent. |

| awfulize | To class as awful or terrible |

| awfy | Terrible, dreadful; remarkable or notable. |

| awfy | As simple intensive; very, exceedingly, extremely. |

| bidie-in | A person who lives with his or her partner in a non-marital relationship; a cohabiting partner. |

| bigsie | Having an exaggerated sense of one’s own importance; arrogant, pretentious, conceited. |

| bok | A South African |

| broigus | Angry; irritated |

| bukateria | A roadside restaurant or street stall with a seating area, selling cooked food at low prices. |

| by-catch | A catch of unwanted fish |

| cab sav | Red wine made from the Cabernet Sauvignon grape |

| cancel culture | Call for the withdrawal of support from a public figure, usually in response to an accusation of a socially unacceptable action or comment. |

| chicken finger | A narrow strip of chicken meat, esp. from the breast, coated in breadcrumbs or batter and deep-fried. |

| chicken noodle soup | A soup made with chicken and noodles, sometimes popularly regarded as a remedy for all ailments or valued for its restorative properties |

| chickie | Used as a term of endearment, especially for a child or woman |

| chipmunky | Resembling or characteristic of a chipmunk, typically with reference to a person having prominent cheeks or a perky, mischievous character. |

| chuddies | Short trousers, shorts. Now it usually means underwear; underpants. |

| contact tracing | The practice of identifying and monitoring individuals who may have had contact with an infectious person |

| contactless | Not involving contact (physical and technological meanings of contactless are being used much more frequently). |

| coulrophobia | Extreme or irrational fear of clowns |

| Covid-19 | An acute respiratory illness in humans caused by a coronavirus, which is capable of producing severe symptoms and death, esp. in the elderly |

| deepfake | An image or recording that has been convincingly altered to misrepresent someone as doing or saying something that was not actually done or said |

| de-extinction | The (proposed or imagined) revival of an extinct species, typically by cloning or selective breeding. |

| deleter | A person who or thing which deletes something. |

| delicense | To deprive (a person, business, vehicle, etc.) of a license providing official permission to operate |

| denialism | The policy or stance of denying the existence or reality of something, esp. something which is supported by the majority of scientific evidence. |

| denialist | A person who denies the existence or reality of something, esp. something which is supported by the majority of scientific or historical evidence |

| destigmatizing | The action or process of removing the negative connotation or social stigma associated with something |

| dof | Stupid, dim-witted; uninformed, clueless. |

| droning | The action of using a military drone or a similar commercially available device |

| e-bike | An electric bike |

| eco-anxiety | A state of stress caused by concern for the earth’s environment |

| enoughness | The quality or fact of being enough; sufficiency, adequacy. |

| Epidemic curve | A visual representation in the form of a graph or chart depicting the onset and progression of an outbreak of disease in a particular population |

| e-waste | Worthless or inferior electronic text or content |

| fantoosh | Fancy, showy, flashy; stylish, sophisticated; fashionable, exotic. Often used disparagingly, implying ostentation or pretentiousness. |

| forehead thermometer | A thermometer that is placed on, passed over, or pointed at the forehead to measure a person’s body temperature. |

| franger | A condom. |

| hair doughnut | A doughnut-shaped sponge or similar material used as the support for a doughnut bun or similar updo |

| hench | Of a person having a powerful, muscular physique; fit, strong. |

| hir | Used as a gender-neutral possessive adjective (his/her/hir watch). In later use often corresponding to the subjective pronoun ze (he/she/ze wears a watch). |

| hygge | A Danish word for a quality of cosiness that comes from doing simple things such as lighting candles, baking, or spending time at home with your family |

| influencer | Someone who affects or changes the way that other people behave: |

| jerkweed | An obnoxious, detestable, or stupid person (esp. a male). Often as a contemptuous form of address. |

| kvell | Meaning to talk admiringly, enthusiastically, or proudly about something |

| kvetchy | Given to or characterized by complaining or criticizing; ill-tempered, irritable. |

| LOL | To laugh out loud; to be amused. |

| macaron | A confection consisting of two small, round (usually colourful) biscuits with a meringue-like consistency |

| MacGyver | To construct, fix, or modify (something) in an improvised or inventive way, typically by making use of whatever items are at hand |

| mama put | A street vendor, typically a woman, selling cooked food at low prices from a handcart or stall. Also a street stall or roadside restaurant. |

| mentionitis | A tendency towards repeatedly or habitually mentioning something (esp. the name of a person one is infatuated with), regardless of its relevance to the topic of conversation |

| microtarget | To direct tailored advertisements, political messages, etc., at (people) based on detailed information about them |

| misgendering | The action or fact of mistaking or misstating a person’s gender, esp. of addressing or referring to a transgender person in terms that do not reflect… |

| next tomorrow | The day after tomorrow. |

| oat milk | A milky liquid prepared from oats, used as a drink and in cooking |

| onboarding | The action or process of integrating a new employee into an organisation, team, etc |

| patient zero | Is defined as a person identified as the first to become infected with an illness or disease in an outbreak |

| pronoid | A person who is convinced of the goodwill of others towards himself or herself |

| puggle | A young or baby echidna or platypus. |

| puggle | A dog cross-bred from a pug and a beagle; such dogs considered collectively as a breed. |

| quilling | The action or practice of bribing electors in order to gain their votes, especially by providing free alcohol |

| rat tamer | Colloquial meaning for a psychologist or psychiatrist |

| report | An employee accountable to a particular manager |

| sadfishing | Colloquial the practice adopted by some people, especially on social media, of exaggerating claims about their emotional problems to generate sympathy |

| sandboxing | The restriction of a piece of software or code to a specific environment in a computer system in which it can be run securely |

| schnitty | Colloquial a schnitzel, especially a chicken schnitzel |

| Segway | A proprietary name for a two-wheeled motorised personal vehicle |

| self-isolate | To isolate oneself from others deliberately; to undertake self-imposed isolation for a period of time |

| shero | A female hero; a heroine. |

| single-use | Designed to be used once and then disposed of or destroyed |

| skunked | Drunk, intoxicated. In later use also under the influence of marijuana |

| slow-walk | To delay or prevent the progress of (something) by acting in a deliberately slow manner |

| social distancing | The action of practice of maintaining a specified physical distance from other people, or of limiting access to and contact between people |

| stepmonster | Colloquial (humorous) (sometimes derogatory) a stepmother |

| tag rugby | A non-contact, simplified form of rugby in which the removal of a tag attached to the ball carrier constitutes a tackle |

| theonomous | Ruled, governed by, or subject to the authority of God |

| thirstry | Showing a strong desire for attention, approval, or publicity. |

| title bar | A horizontal bar at the top of a program window, used to display information such as the name of the program in use, the file or web page that is active. |

| topophilia | Love of, or emotional connection to, a particular place or physical environment |

| truthiness | A seemingly truthful quality not supported by facts or evidence |

| UFO | UnFinished Object: In knitting, sewing, quilting, etc.: an unfinished piece of work |

| unfathom | To come to understand (something mysterious, puzzling, or complicated); to solve (a mystery, etc.) |

| weak sauce | That lacks power, substance, or credibility; pathetic, worthless; stupid. |

| WFH | An abbreviation for “working from home.” |

| WIP | Work in progress |

| zoodle | A spiralised strand of zucchini, sometimes used as a substitute for pasta |

Проектная работа «THE MEANING AND THE ORIGIN OF ENGLISH WORDS». Разработала Аниканова Ангелина, 11 класс. МОУ «Лицей №26», г. Подольск

Предпросмотр презентации к проектной работе

Introduction

This paper is devoted to the meaning of English words and their origin. We tried to look into the process of words coming into the language and to gain an understanding of what is meaning itself, though the question “What is meaning?” is one of those questions which are easier to ask than answer. The linguistic science at present is not able to put forward a definition of meaning which is conclusive.

However, there are certain facts of which we can be reasonably sure, and one of them is that the very function of the word as a unit of communication is made possible by its possessing a meaning. Therefore, among the word’s various characteristics, meaning is certainly the most important.

Generally speaking, meaning can be more or less described as a component of the word through which the concept is communicated, in this way endowing the word with the ability to denote real objects, qualities, actions and abstract notions.

The meaning of a word is made up of its lexical meaning and grammatical meaning. Besides, the meaning has two aspects: denotation, the meaning itself, and connotation, i.e. the associations that words can have in our minds.

The lexical meaning of a word is the realization of a notion by means of a definite language system. A word is a language unit while a notion is a unit of thinking. A notion cannot exist without a word expressing it in the language, but there are words which do not express any notion but have a lexical meaning. Interjections express emotions but not notions, but they have lexical meanings, e.g. Alas! (disappointment), Oh, my buttons! (surprise) etc. There are also words which express both notions and emotions, e.g. girlie, a pig (when used metaphorically).

A notion denotes the reflection in the mind of real objects and phenomena in their relations. Notions, as a rule, are international (especially with the nations of the same cultural level), while meanings can be nationally limited. The grouping of meanings in the semantic structure of a word is determined by the whole system of every language.

In the paper we dwelt on such notions as polysemy, semantic structure of the word, causes of development of new meanings, linguistic metaphor, linguistic metonymy, generalization and specialization om meaning. Moreover, we were keen on following the origin of some English words, sayings and customs and historic events that caused these words and expressions to appear in the language.

Thus, the aim of the paper is to show how the words originated and got their meaning. To achieve this aim we put forward the following tasks:

— to acquaint English learners with polysemy;

— to explain the causes of development of new meanings;

— to follow the process of narrowing or broadening meanings;

— to trace the origins of some English words, sayings and customs;

— to help English learners to avoid misusing some words which sound alike but mean different things;

— to provide teachers of English with supplementary material to be used in their teaching practice.

Field of research: the vocabulary of the English language.

Object of research: the meaning and the origin of some English words and expressions and historical events that favoured their development in the language.

The development of lexical meanings in any language is influenced by the whole network of ties and relations between words and other aspects of the language.

Words and Meaning

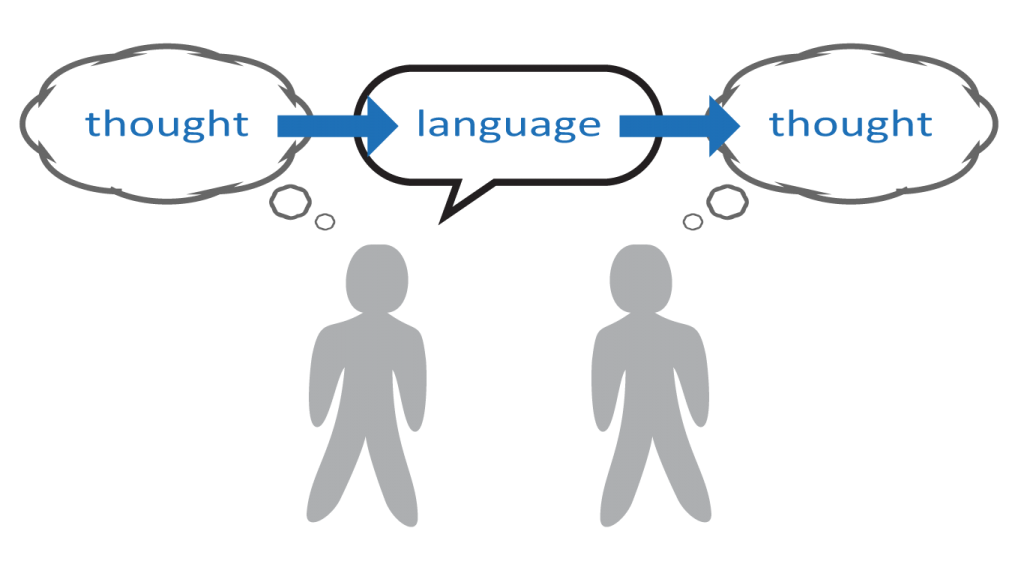

Isn’t it fantastic that the mere vibration of a speaker’s vocal chords should be taken up by a listener’s brain and converted into vivid pictures? If magic does exist in the world, then it is truly the magic of human speech; only we are so used to this miracle that we do not realize its almost supernatural qualities.

The meanings of all the utterances of a speech community are said by a famous linguist to include the total experience of that community: arts, science, practical occupations, amusements, personal and family life.

A very simple approach to words is to see them as labeling things in the world. This works well for some words. Concrete nouns like cat, sheep, frog, etc. are used to refer to certain animals that can be described or pointed to. However, there are many nouns for which this approach will not work. We cannot point to abstractions like feelings, employment or pleasure, even though we understand the meaning of these concepts.

It is useful to make a distinction between this kind of “naming” meaning, which is called denotation, and another kind of meaning, which is called connotation. Connotation refers to the associations that words can have in our minds. For example, the denotation of the word pig is a farm animal that is usually pink or black and has short legs, a fat body and a curved tail. For some people the word pig might have connotations of dirty and untidy; others will think of unpleasant or offensive.

Some words bring very different connotations to mind among different groups of people. Those whose profession is to persuade us, such as advertisers, politicians, preachers, and orators, need to be sensitive to the connotations of the words they use.

The connotations of words are culturally determined. In English, the word “red” can have negative connotations of “blood”. In Russian, the word for “red” has very good connotations. The Russian word for “beautiful” is prekrasnyi, which contains within it the word for “red”.

The inner form of the word (i.e. its meaning) presents a structure which is called the semantic structure of the word.

1.1 Polysemy. Semantic Structure of the Word

It is generally known that most words convey several concepts and thus possess the corresponding number of meanings. A word having several meanings is called polysemantic, and the ability of words to have more than one meaning is described by the term polysemy.

Most English words are polysemantic. It should be noted that the wealth of expressive resources of a language largely depends on the degree to which polysemy has developed in the language. Sometimes people who are not very well informed in linguistic matters claim that a language is lacking in words if the need arises for the same word to be applied to several different phenomena. In fact, it is exactly the opposite: if each word is found to be capable of conveying, at least two notions instead of one, the expressive potential of the whole vocabulary increases twofold. Hence, a well-developed polysemy is not a drawback but a great advantage in a language.

On the other hand, it should be pointed out that the number of sound combinations that human speech organs can produce is limited. Therefore, at a certain stage of language development the production of new words by morphological means becomes limited, and polysemy becomes increasingly important in providing the means for enriching the vocabulary. From this it should be clear that the process of enriching the vocabulary does not consist merely in adding new words to it, but, also, in the constant development of polysemy.

The system of meanings of any polysemantic word develops gradually, mostly over the centuries, as more and more new meanings are either added to old ones, or oust some of them. So the complicated processes of polysemy development involve both the appearance of new meanings and the loss of old ones.

Let’s see the meanings of the word dull.

Dull, adj.

- Uninteresting, monotonous, boring; e.g. a dull book, a dull film.

- Slow in understanding, stupid; e.g. a dull student.

- Not clear or bright; e.g. dull weather, a dull day, a dull colour.

- Not loud or distinct; e.g. a dull sound.

- Not sharp; e.g. a dull knife.

- Not active; e.g. trade is dull.

- Seeing badly; e.g. dull eyes.

- Hearing badly; e.g. dull ears.

One can distinctly feel that there is something that all these seemingly miscellaneous meanings have in common, and that is the implication of deficiency, be it of colour (III), wits (II), interest (I), sharpness (V), etc. The implication of insufficient quality, of something lacking, can be clearly distinguished in each separate meaning.

Dull, adj..

- Uninteresting – deficient in interest or excitement.

- Stupid – deficient in intellect.

- Not bright – deficient in light or colour.

- Not loud – deficient in sound.

- Not sharp – deficient in sharpness.

- Not active – deficient in activity.

- Seeing badly – deficient in eyesight.

- Hearing badly – deficient in hearing.

One of the most important “drawbacks” of polysemantic words is that there is sometimes a chance of misunderstanding when a word is used in a certain meaning but accepted by a listener or reader in another. It is only natural that such cases provide staff of which jokes are made, such as the ones that follow.

Customer: I would like a book, please.

Bookseller: Something light?

Customer: That doesn’t matter. I have my car with me.

In this conversation the customer is honestly misled by the polysemy of the adjective light taking it in the literal sense whereas the bookseller uses the word in its figurative meaning “not serious, entertaining”.

In the following joke one of the speakers pretends to misunderstand his interlocutor basing his angry retort on the polysemy of the noun kick: 1) — thrill, pleasurable excitement (inform.), 2) – a blow with the foot.

The critic started to leave in the middle of the second act of the play.

“Don’t go,” said the manager. “I promise there’s a terrific kick in the next act.”

“Fine,” was the retort, “give it to the author.”

It is common knowledge that context is a powerful preventive against any misunderstanding of meanings. For instance, the adjective dull, if used out of context, would mean different things to different people or nothing at all. It is only in combination with other words that it reveals its actual meaning: a dull pupil, a dull play, a dull razor-blade, dull weather, etc. Sometimes, however, such a minimum context fails to reveal the meaning of the word, and it may be correctly interpreted only through what Professor Amosova termed a second-degree context, as in the following example: The man was large, but his wife was even fatter. The word fatter here serves as a kind of indicator pointing that large describes a stout man and not a big one.

We’d like to give some more examples of polysemy in the following jokes:

“Where have you been for the last four years?”

“At college taking medicine.”

“And did you finally get well?”

Caller: I wonder if I can see your mother, little boy. Is she engaged?

Willie: Engaged! She’s married.

Booking Clerk: (at a small village station): You’ll have to change twice before you get to York.

Villager (unused to travelling): Goodness me! And I’ve only brought the clothes I’m wearing.

Professor: You missed my class yesterday, didn’t you?

Student: Not in the least, sir, not in the least.

1.2 How Words Develop New Meanings

Words develop new meanings due to certain reasons. The first group of these is traditionally termed historical or extra-linguistic. Different kinds of changes in a nation’s social life, in its culture, knowledge, technology, arts lead to gaps appearing in the vocabulary which have to be filled. Newly created objects, new notions and phenomena must be named. There are some ways for providing new names for newly created notions: making new words (word-building) and borrowing foreign ones. One more way of filling such vocabulary gaps is by applying some old word to a new object or notion.

When the first textile factories appeared in England, the old word mill was applied to these early industrial enterprises. In this way, mill added a new meaning to its former meaning “a building in which corn is ground into flour”. The new meaning was “textile factory”.

A similar case is the word carriage” which had (and still has) the meaning “a vehicle drawn by horses”, but, with the first appearance of railways in England, it received a new meaning, that of “a railway car”.

The history of English nouns describing different parts of a theatre may also serve as a good illustration of how well-established words can be used to denote newly-created objects and phenomena. The words stalls, box, pit, circle had existed for a long time before the first theatres appeared in England. With their appearance, the gaps in the vocabulary were easily filled by these widely used words which, as a result, developed new meanings.

It is of some interest to note that the Russian language found a different way of filling the same gap: in Russian, all the parts of the theatre are named by borrowed words: партер, ложа, амфитеатр, бельэтаж.

Stalls and box formed their meanings in which they denoted parts of the theatre on the basis of association. The meaning of the word box “a small separate enclosure forming a part of the theatre” developed on the basis of its former meaning “a rectangular container used for packing or storing things”. The two objects became associated in the speakers’ minds because boxes in the earliest English theatres really resembled packing cases. They were enclosed on all sides and heavily curtained even on the side facing the audience so as to conceal the privileged spectators occupying them from curious or insolent looks.

The association on which the theatrical meaning of stalls was based is even more curious. The original meaning was “compartments in stables or sheds for the accommodation of animals (e.g. cows, horses, etc.)”. There does not seem to be much in common between the privileged and expensive part of a theatre and stables intended for cows and horses, unless we take into consideration the fact that theatres in older times greatly differed from what they are now. What is now known as the stalls was, at that time, standing space divided by barriers into sections so as to prevent the enthusiastic crowd from knocking one another down and hurting themselves. So, there must have been a certain outward resemblance between theatre stalls and cattle stalls. It is also possible that the word was first used humorously or satirically in this new sense.

The process of development of a new meaning (or a change of meaning) is traditionally termed transference.

1.3 Transference of Meaning Based on Resemblance (linguistic metaphor)

This type of transference is also referred to as linguistic metaphor. Metaphor is a complex cognitive phenomenon. It is traditionally thought of as a kind of comparison. A new meaning appears as a result of associating two objects (phenomena, qualities, etc.) due to their outward similarity. Box and stalls, as is clear from the explanations above, are examples of this type of transference.

The noun eye, for instance, has for one of its meanings «hole in the end of a needle» (cf. with the R. ушко иголки), which also developed through transference based on resemblance. A similar case is represented by the neck of a bottle.

The noun drop (mostly in the plural form) has, in addition to its main meaning «a small particle of water or other liquid», the meanings: «ear-rings shaped as drops of water» (e. g. diamond drops) and «candy of the same shape» (e. g. mint drops). It is quite obvious that both these meanings are also based on resemblance. In the compound word snowdrop the meaning of the second constituent underwent the same shift of meaning (also, in bluebell). In general, metaphorical change of meaning is often observed in idiomatic compounds. You are the sunshine of my life compares someone beloved with sunshine. The expression candle in the wind likens life to a candle flame that may easily be blown out by any passing draft or gust. The fragility of life is thus emphasized. But metaphor is not just associated with poetic language or especially high-flown literary language. Metaphor is an extremely common process in language usage. For example, a cape-like garment that protected against the weather was given the name cloak, a word borrowed from French, in which it meant “bell”. The garment was given the name for a bell because of its cut: It created a somewhat bell-like shape when draped over the shoulders and allowed to fall vertically to the knees or below, where it “belled” out from the body.

The main meaning of the noun branch is «limb or subdivision of a tree or bush». On the basis of this meaning it developed several more. One of them is «a special field of science or art» (as in a branch of linguistics). This meaning brings us into the sphere of the abstract, and shows that in transference based on resemblance an association may be built not only between two physical objects, but also between a concrete object and an abstract concept.

The noun star on the basis of the meaning «heavenly body» developed the meaning «famous actor or actress». Nowadays the meaning has considerably widened its range, and the word is applied not only to screen idols (as it was at first), but, also, to popular sportsmen (e. g. football stars), pop-singers, etc. Of course, the first use of the word star to denote a popular actor must have been humorous or ironical: the mental picture created by the use of the word in this new meaning was a kind of semi-god surrounded by the bright rays of his glory. Yet, very soon the ironical colouring was lost, and, furthermore, the association with the original meaning considerably weakened.

The meanings formed through this type of transference are frequently found in the informal layer of the vocabulary, especially in slang. A red-headed boy is almost certain to be nicknamed carrot or ginger by his schoolmates, and the one who is given to spying and sneaking gets the derogatory nickname of rat. Both these meanings are metaphorical.

Also, the slang meanings of words such as nut, onion (head), saucers (eyes), hoofs (feet) and very many others were all formed by transference based on resemblance.

Sometimes what was originally a metaphor can completely lose its metaphorical force, when most or all speakers can no longer see the metaphor. Such cases are called dead metaphors. The word understand, for example, is a dead metaphor, having its origins in the idea that “standing under” meant knowing something thoroughly. Another example is the word consider which was originally a metaphor meaning “consult the stars (using astrological principles) when making a decision”; gorge which now means “a deep narrow valley with steep sides” meant “throat”, and so forth for thousands more.

1.4 Transference of Meaning Based on Contiguity (linguistic metonymy)

Linguistic metonymy is the use of one word with the meaning of another with which it is typically associated. The association is based on subtle psychological links between different objects and phenomena. The two objects may be associated together because they often appear in common situations, and so the image of one is easily accompanied by the image of the other; or they may be associated on the principle of cause and effect, of common function, of some material and an object which is made of it, etc. When someone uses metonymy, they don’t wish to transfer qualities, but to indirectly refer to one thing with another word for a related thing. The common expression the White House said today … is a good example of metonymy. The term White House actually refers to the authorities who work in the building called the White House. The latter is of course an inanimate object that says nothing. Similarly, in a monarchy the expression the Crown is used to mean the monarch and the departments of the government headed by the monarch. Crown literary refers only to a physical object sometimes worn by the actual monarch.

Metonymy can be seen as a kind of shorthand indirect reference, and people use it all the time. For example, a doctor or nurse might refer in shorthand to a patient by means of the body part treated (The broken ankle is in room 2); a waiter might use a similar metonymy for a customer, this time using the order as an identifying feature, saying The ham sandwich left without paying.

There are different kinds of transference based on contiguity. For example, the Old English adjective glad meant «bright, shining» (it was applied to the sun, to gold and precious stones, to shining armour, etc.). The later (and more modern) meaning «joyful» developed on the basis of the usual association (which is reflected in most languages) of light with joy (cf. with the R. светлое настроение; светло на душе).

The meaning of the adjective sad in Old English was «satisfied with food» (cf. with the R. сыт(ый) which is a word of the same Indo-European root). Later this meaning developed a connotation of a greater intensity of quality and came to mean «oversatisfied with food; having eaten too much». Thus, the meaning of the adjective sad developed a negative evaluative connotation and now described not a happy state of satisfaction but, on the contrary, the physical unease and discomfort of a person who has had too much to eat. The next shift of meaning was to transform the description of physical discomfort into one of spiritual discontent because these two states often go together. It was from this prosaic source that the modern meaning of «sad» «melancholy», «sorrowful» developed, and the adjective describes now a purely emotional state. The two previous meanings («satisfied with food» and «having eaten too much») were ousted from the semantic structure of the word long ago.

The foot of a bed is the place where the feet rest when one lies in bed, but the foot of a mountain got its name by another association: the foot of a mountain is its lowest part, so that the association here is based on common position.

By the arms of an arm-chair we mean the place where the arms lie when one is sitting in the chair, so that the type of association here is the same as in the foot of a bed. The leg of a bed (table, chair, etc.), though, is the part which serves as a support, the original meaning being «the leg of a man or animal». The association that lies behind this development of meaning is the common function: a piece of furniture is supported by its legs just as living beings are supported by theirs.

The meaning of the noun hand realized in the context hand of a clock (watch) originates from the main meaning of this noun «part of human body». It also developed due to the association of the common function: the hand of a clock points to the figures on the face of the clock, and one of the functions of human hand is also that of pointing to things.

Another meaning of hand realized in such contexts as factory hands, farm hands is based on another kind of association: strong, skillful hands are the most important feature that is required of a person engaged in physical labour (cf. with the R. рабочие руки).

The main (and oldest registered) meaning of the noun board was “a flat and thin piece of wood, a wooden plank». On the basis of this meaning developed the meaning «table» which is now archaic. The association which underlay this semantic shift was that of the material and the object made from it: a wooden plank (or several planks) is an essential part of any table. This type of association is often found with nouns denoting clothes: e. g. a taffeta («dress made of taffeta»); a mink («mink coat»), a jersy («knitted shirt or sweater»).

Meanings produced through transference based on contiguity sometimes originate from geographical or proper names. China in the sense of «dishes made of porcelain» originated from the name of the country which was believed to be the birthplace of porcelain. Tweed («a coarse wool cloth») got its name from the river Tweed and cheviot (another kind of wool cloth) from the Cheviot hills in England.

The name of a painter is frequently transferred onto one of his pictures: a Matisse = a painting by Matisse.

1.5 Broadening and Narrowing of Meaning

Sometimes, the process of transference may result in a considerable change in range of meanings. An example of the broadening of meaning is pipe. Its earliest recorded meaning was «a musical wind instrument». Nowadays it can denote any hollow oblong cylindrical body (e. g. water pipes). This meaning developed through transference based on the similarity of shape (pipe as a musical instrument is also a hollow oblong cylindrical object) which finally led to a considerable broadening of the range of meaning.

It is interesting to trace the history of the word girl as an example of the changes in the range of meaning in the course of the semantic development of a word. In Middle English it had the meaning of «a small child of either sex». Then the word underwent the process of transference based on contiguity and developed into the meaning of «a small child of the female sex», so that the range of meaning was somewhat narrowed. In its further semantic development the word gradually broadened its range of meaning. At first it came to mean not only a female child but, also, a young unmarried woman, later, any young woman, and in modern colloquial English it is practically synonymous to the noun woman (e. g. The old girl must be at least seventy), so that its range of meaning is quite broad.

The history of the noun lady somewhat resembles that of girl. In Old English this word denoted the mistress of the house, i. e. any married woman. Later, a new meaning developed which was much narrower in range: «the wife or daughter of a baronet» (aristocratic title). In Modern English the word lady can be applied to any woman, so that its range of meaning is even broader than that of the О. Е. In Modern English the difference between girl and lady in the meaning of woman is that the first is used in colloquial style and sounds familiar whereas the second is more formal and polite.

Origins of English Words, Sayings and Customs

It is always curious to know how this or that saying appeared in the language. We’ve found out some information about most popular sayings and customs. However, most of these definitions have been disputed by various sources, so, they should be treated as source of entertainment, not reference.

In the 1400s a law was set forth that a man was not allowed to beat his wife with a stick no thicker than his thumb. Hence, we have “the rule of thumb”, which now means a rough method of calculation, based on practical experience.

Many years ago in Scotland a new game was invented. It was ruled “Gentlemen Only, Ladies Forbidden”…and thus the word GOLF entered the language.

Most people got married in June because they took their yearly bath in May, and still smelled pretty good by June. However, they were starting to smell, so brides carried a bouquet of flowers to hide the body odour. Hence the custom of carrying a bouquet when getting married.

Baths consisted of a big tub filled with hot water. The man of the house had the privilege of the nice clean water, then all the other sons and men, then the women and finally the children, last of all the babies. By then the water was so dirty that you could actually lose someone in it. Hence, the saying, “Don’t throw the baby out with the bath water”.

Houses in England had thatched roofs with no wood underneath. It was the only place for animals to get warm, so all the cats and other small animals (mice, bugs) lived in the roof. When it rained it became slippery and sometimes the animals would slip off the roof. Hence, the saying “It’s raining cats and dogs”.

In the Royal Navy the punishment prescribed for most serious crimes was flogging. This was administered by the Boatswain’s Mate using a whip called a “cat of nine tails”. The ‘cat’ was kept in a leather bag. It was considered bad news indeed when the “cat was let out of the bag”. Other sources attribute the expression to the old English scam of selling someone a pig in a poke (bag) when the pig turned out to be a cat instead.

Teddy bear is clearly one of the most popular doll brands in the world. But why is the bear’s name Teddy? Why not Johnny or Willie or even Barry? Teddy bear was named after one of the most respectful presidents of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt. American people during his time called him Teddy as a nickname for Theodore and he actually liked to be called like that. Then, one smart couple produced bear dolls and named them after Theodore’s nickname which drove their products to be dramatically popular overnight. So now, when you see Teddy bear, you will understand that it is more than just a doll bear, it is also a memory of the most beloved president of the United States.

2.1 An Apple a Day Nursery Rhyme / Poem

The simple meaning behind the sentiment expressed in ‘An apple a day’ poem is one to encourage a child to eat healthily and wisely that is an apple a day! Although, in a modern day version of this poem ‘Doctor’ could be replaced with ‘Dentist’.

The picture depicts a Physician in the 16th Century — the thought of seeing someone like this would guarantee that a child would eat an apple a day!

The author of the poem «An apple a day» is unknown and the first publication date has been untraceable.

Poem — An apple a day keeps the Doctor away.

An apple a day keeps the doctor away

Apple in the morning — Doctor’s warning

Roast apple at night — starves the doctor outright

Eat an apple going to bed — knock the doctor on the head

Three each day, seven days a week — ruddy apple, ruddy cheek

2.2 Humpty Dumpty Nursery Rhyme (History and Origins)

Humpty Dumpty was in fact believed to be a large cannon! It was used during the English Civil War ( 1642 — 1649) in the Siege of Colchester (13 Jun 1648 — 27 Aug 1648). Colchester was strongly fortified by the Royalists and was laid to siege by the Parliamentarians (Roundheads). In 1648 the town of Colchester was a walled town with a castle and several churches and was protected by the city wall. Standing immediately adjacent the city wall, was St Mary’s Church. A huge cannon, colloquially called Humpty Dumpty, was strategically placed on the wall next to St Mary’s Church. A shot from a Parliamentary cannon succeeded in damaging the wall beneath Humpty Dumpty which caused the cannon to tumble to the ground. The Royalists, or Cavaliers, ‘all the King’s men’ attempted to raise Humpty Dumpty onto another part of the wall. However, because the cannon, or Humpty Dumpty, was so heavy ‘All the King’s horses and all the King’s men couldn’t put Humpty together again!’ This had a drastic consequence for the Royalists as the strategically important town of Colchester fell to the Parliamentarians after a siege lasting eleven weeks.

A Picture of typical Cavalier who would have fought for the Royalists during the English Civil War. The word Cavalier is derived from the French word Chevalier meaning a military man serving on horseback — a knight. A Roundhead ( Parliamentarian) was so called from the close-cropped hair of the Puritans

Humpty Dumpty poem

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall.

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the King’s horses, and all the King’s men

Couldn’t put Humpty together again!

2.3 This is the House that Jack built

The origin of the lyrics to ‘This is the house that Jack built’ cannot be traced to specific people or historical events but merely reflects the everyday characters and lifestyle which could have been found in rural England and dates back to the sixteenth century. The phrase ‘This is the house that Jack built’ is often used as a derisory term in describing a badly constructed building!

2.4 Remember, Remember the Fifth of November

The words of «Remember, Remember» refer to Guy Fawkes and Gunpowder plot with origins in the 17th century English history. On the 5th November, 1605 Guy Fawkes was caught in the cellars of the Houses of Parliament with several dozen barrels of gunpowder. Guy Fawkes was subsequently tried as a traitor with his co-conspirators for plotting against the government. He was tried by Judge Popham who came to London specifically for the trial from his country manor Littlecote House in Hungerford, Gloucestershire. Fawkes was sentenced to death and the form of the execution was one of the most horrendous ever practised (hung, drawn and quartered) which reflected the serious nature of the crime of treason.

The poem “Remember, remember the 5th of November” is sometimes referred to as ‘Please to remember the fifth of November’. It serves as a warning to each new generation that treason will never be forgotten. In England the 5th of November is still commemorated each year with fireworks and bonfires culminating with the burning of effigies of Guy Fawkes (the guy). The ‘guys’ are made by children by filling old clothes with crumpled newspapers to look like a man. Tradition allows British children to display their ‘guys’ to passers-by and asking for «a penny for the guy».

The picture is of the ‘Gunpowder Plot’ conspirators with Thomas Bates, Robert Wintour, Christopher Wright, John Wright, Thomas Percy, Guy Fawkes, Robert Catesby and Thomas Wintour.

Remember, Remember poem:

Remember, remember the fifth of November

Gunpowder, treason and plot.

I see no reason why gunpowder, treason

Should ever be forgot…

Confusing Words

There are words in the English language that present some difficulties for English learners. Such words sound alike but mean different things when put into writing, so, English learners often misuse them. This list will help them distinguish between some of the more common words that sound alike.

Accept, Except

- accept = verb meaning to receive or to agree: He accepted their praise graciously.

- except = preposition meaning all but, other than: Everyone went to the game except Alyson.

Affect, Effect

- affect = verb meaning to influence: Will lack of sleep affect your game?

- effect = noun meaning result or consequence: Will lack of sleep have an effect on your game?

- effect = verb meaning to bring about, to accomplish: Our efforts have effected a major change in university policy.

A memory-help for affect and effect is RAVEN: Remember, Affect is a Verb and Effect is a Noun.

Advise, Advice

- advise = verb that means to recommend, suggest, or counsel: I advise you to be cautious.

- advice = noun that means an opinion or recommendation about what could or should be done: I’d like to ask for your advice on this matter.

Conscious, Conscience

- conscious = adjective meaning awake, perceiving: Despite a head injury, the patient remained conscious.

- conscience = noun meaning the sense of obligation to be good: Chris wouldn’t cheat because

his conscience wouldn’t let him.

Idea, Ideal

- idea = noun meaning a thought, belief, or conception held in the mind, or a general notion or conception formed by generalization: Jennifer had a brilliant idea — she’d go to the Writing Lab for help with her papers!

- ideal = noun meaning something or someone that embodies perfection, or an ultimate object or endeavor: Mickey was the ideal for tutors everywhere.

- ideal = adjective meaning embodying an ultimate standard of excellence or perfection, or the best; Jennifer was an ideal student.

Its, It’s

- its = possessive adjective (possessive form of the pronoun it): The crab had an unusual growth on its shell.

- it’s = contraction for it is or it has (in a verb phrase): It’s still raining; it’s been raining for three days. (Pronouns have apostrophes only when two words are being shortened into one.)

Lead, Led

- lead = noun referring to a dense metallic element: The X-ray technician wore a vest lined with lead.

- led = past-tense and past-participle form of the verb to lead, meaning to guide or direct: The evidence led the jury to reach a unanimous decision.

Than, Then

- Than — used in comparison statements: He is richer than I am.

— used in statements of preference: I would rather dance than eat.

— used to suggest quantities beyond a specified amount: Read more than the first paragraph.

- Then — a time other than now: He was younger then. She will start her new job then.

next in time, space, or order: First we must study; then we can play, suggesting a logical conclusion: If you’ve studied hard, then the exam should be no problem

Their, There, They’re

- Their = possessive pronoun: They got their books.

- There = that place: My house is over there. (This is a place word, and so it contains the word here.)

- They’re = contraction for they are: They’re making dinner. (Pronouns have apostrophes only when two words are being shortened into one.)

To, Too, Two

- To = preposition, or first part of the infinitive form of a verb: They went to the lake to swim.

- Too = very, also: I was too tired to continue. I was hungry, too.

- Two = the number 2: Two students scored below passing on the exam.

Two, twelve, and between are all words related to the number 2, and all contain the letters tw. Too can mean also or can be an intensifier, and you might say that it contains an extra о («one too many»)

We’re, Where, Were

- We’re = contraction for we are: We’re glad to help. (Pronouns have apostrophes only when two words are being shortened into one.)

- Where = location: Where are you going? (This is a place word, and so it contains the word here.)

- Were = a past tense form of the verb be: They were walking side by side.

Your, You’re

- Your = possessive pronoun: Your shoes are untied.

- You’re = contraction for you are: You’re walking around with your shoes untied. (Pronouns have apostrophes only when two words are being shortened into one.)

One Word or Two?

All right/alright

- all right: used as an adjective or adverb; older and more formal spelling, more common in scientific & academic writing: Will you be all right on your own?

- alright: Alternate spelling of all right; less frequent but used often in journalistic and business publications, and especially common in

fictional dialogue: He does alright in school.

All together/altogether

- all together: an adverb meaning considered as a whole, summed up: All together, there were thirty-two students at the museum.

- altogether: an intensifying adverb meaning wholly, completely, entirely: His comment raises an altogether different problem.

Anyone/any one

- anyone: a pronoun meaning any person at all: Anyone who can solve this problem

deserves an award.- any one: a paired adjective and noun meaning a specific item in a group; usually used with of: Any one of those papers could serve as an example.

Note: There are similar distinctions in meaning for everyone and every one

Anyway/any way

- anyway: an adverb meaning in any case or nonetheless: He objected, but she went anyway.

- any way: a paired adjective and noun meaning any particular course, direction, or manner: Any way we chose would lead to danger.

Awhile/a while

- awhile: an adverb meaning for a short time; some readers consider it nonstandard; usually needs no preposition: Won’t you stay awhile?

- a while: a paired article and noun meaning a period of time; usually used with for: We talked for a while, and then we said good night

Conclusion

Having learnt the problem of words’ meaning we’ve come to understanding that the lexical meaning of a word is the realization of a notion. The number of meanings does not correspond to the number of words, neither does the number of notions. Their distribution in relation to words is peculiar in every language. In Russian we have two words for the English man: мужчина and человек. In English, however, man cannot be applied to a female person. We say in Russian: Она хороший человек. In English we use the word person in this case: She is a good person. A notion cannot exist without a word, but there are words which do not express any notion but have a lexical meaning. There are two kinds of meaning: denotation (the thing that is actually described by a word) and connotations (the feelings or ideas the word suggests).

Most English words are polysemantic and one should be careful in order not to misunderstand the interlocutor. Context is a powerful preventive against any misunderstanding of meaning.

In their development words underwent certain semantic changes due to historic or extra-linguistic factors. The process of development of a new meaning is termed transference. There is transference based on resemblance (linguistic metaphor) and transference based on contiguity (linguistic metonymy). Sometimes the process of transference may result in a considerable change in a range of meanings (broadening or narrowing).

The ways of enriching vocabulary with sayings and customs have always been a source of curiosity. Most of the sayings appeared in the language due to some historic events. We’ve traced the origins of some most popular of them.

We couldn’t cover all aspects of meaning in this paper, we’ve touched upon only some of them. However, the facts mentioned in it seem to be quite interesting in language learning. That’s why we suppose the work has practical value both for teachers and for students as the information given here will broaden the outlook of English learners and enrich their vocabulary. The material of the paper can be used by teachers in their practice.

Bibliography.

-

- Антрушина Г.Б., Афанасьева О.В., Морозова Н.Н. Лексикология английского языка /English Lexicology/ — М.: Высш.шк., 1985. – 223с.

- Арнольд И.В. Лексикология современного английского языка / И.В. Арнольд – 3-е изд., перераб. и доп. – М.: Высш. шк., 1986. – 295с.

- Балк Е.А., Леменев М.М. Причудливый английский /Queer English/ — М.: Изд-во НЦ Энас, 2002 – 168с.

- Интернет сайты: www.rhymes.org.uk, www.expats.org.uk

Файлы для скачивания

Презентация

(Скачивание документов доступно только для авторизованных пользователей)

Проектная работа

(Скачивание документов доступно только для авторизованных пользователей)

Читайте также

The English language has an astounding number of words, and this number continues to grow each year. From preparing for your SATs or IELTS to communicating better with your peers, here are 50 daily use of English words with meanings to add to your vocabulary!

Daily use English words | Some interesting facts

The English language is arguably the most widely spoken language in the world, with approximately 1.5 billion people speaking it regularly. An interesting fact to note is that over 1 billion of this population speak English as a secondary language. The Second Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (which has a whopping volume of 20) has registered around 171,476 common words in English that are currently in use. This, however, does not account for the wide range of jargon and slang worldwide.

How many words does an average person know? Robert Charles Lee writes that around 3000 words comprehensively cover everyday writing and reading. This includes speech, texts, movies, books, newspapers, and blogs.

Understanding the meaning of some of the most commonly used English words might help you improve your daily language and comprehension. Here are 50 common English words with definitions to help you with everything from discussing current events to writing an experience letter to simply communicating better at your workplace!

1. Absence – The lack or unavailability of something or someone.

2. Approval – Having a positive opinion of something or someone.

3. Answer – The response or receipt to a phone call, question, or letter.

4. Attention – Noticing or recognizing something of interest.

5. Amount – A mass or a collection of something

6. Borrow – To take something with the intention of returning it after a period of time.

7. Baffle – An event or thing that is a mystery and confuses.

8. Ban – An act prohibited by social pressure or law.

9. Banish – Expel from the situation, often done officially.

10. Banter – Conversation that is teasing and playful.

11. Characteristic – referring to features that are typical to the person, place, or thing.

12. Cars – Four-wheeled vehicles used for traveling.

13. Care – extra responsibility and attention.

14. Chip – a small and thin piece of a larger item.

15. Cease – to eventually stop existing.

16. Dialogue – A conversation between two or more people.

17. Decisive – a person who can make decisions promptly.

18. Delusion – false impression or belief.

19. Deplete – steady reduction in the quantity or number of something.

20. Derogatory – disrespectful person or statement.

21. Edible – something suitable to be eaten.

22. Effervescent – an event marked by excitement and high spirits.

23. Eloquent – an individual who expresses themselves effectively and clearly.

24. Elusive – a person skilled at evading capture; a daily use of English words used to describe evasive criminals.

25. Embody – represented in a physical form.

Just a few more…

26. Fabricate – an invention of untrue facts to a story or situation.

27. Feasible – an activity that is possible.

28. Feat – an activity that requires great strength, skill, and courage.

29. Feeble – a person or statement that is unconvincing and weak.

30. Fixation – An obsession over something or someone.

31. Generic – a group or class that does not have a brand name.

32. Gimmick – a device or trick delivered to attract attention.

33. Graffiti – Drawings or writings on a surface in public.

34. Grandiose – a person, plan, or situation that is ambitious, showy, and impressive.

35. Grievous – an event or person causing severe grief.

You’re almost there!

36. Hiatus – A noun among daily use English words describing a gap or a pause in a sequence.

37. Hogwash – Insincere or useless statements.

38. Hostile – an unfriendly person or situation.

39. Huddle – to gather together in a close mass or group.

40. Hindsight – the understanding of an event after it has already happened.

41. Idealistic – a person who is motivated by moral and noble beliefs as opposed to practicality.

42. Imminent – an event or a situation that is about to occur or close in time.

43. Impartial – a person who is free from preconceived notions or undue bias.

44. Imperative – an action that is necessary or crucial.

45. Impromptu – describing a situation that occurs without advance preparations.

46. Jeopardize – the endangerment to a person or situation.

47. Jovial – a cheerful, merry and good-natured person.

48. Jug – a utensil or container used to hold liquids.

49. Jostle – moving through a crowd by means of shoving and pushing.

50. Jubilant – a person or crowd that is full of delight and high spirits.

Key takeaways

- The English language is extensive, with a large number of diverse terms used in daily conversations.

- Regularly updating yourself with some common English vocabulary and learning how to use them will improve your communication in the language.

- You’ll be able to convey yourself and your views much more clearly with the correct words and phrases, making you quite the orator!

Feel free to check out our blog for more such tips! In case of any assistance, reach out to us or drop a comment below!

Happy Learning!

Liked this blog? Read: Improve your English speech with these 6 amazing tips!

FAQs

Q1. What are common sentences in English?

Answer- Some basic sentences that you should know are-

- How are you?

- Thank you so much.

- My name is___

- Nice to meet you.

- Where are you from?

- What do you do for a living

- Excuse me?

- I am sorry.

Q2. How do I improve my English speaking?

Answer- To improve your English you could listen to podcasts, watch movies, listen to music, and of course, read more. You can even make a list of new words you learn and try to incorporate them into your day-to-day activities.

Listen to the iSchoolConnect podcast to learn more about studying abroad and improve your English along the way!

Q3. Can I learn English by myself?

Answer- This might be challenging as you won’t know which areas need improvement, but you can do this on your own. Practice on your own through the tips mentioned above and ask your friends to help you when needed. You can also use different apps like Duolingo to learn English.

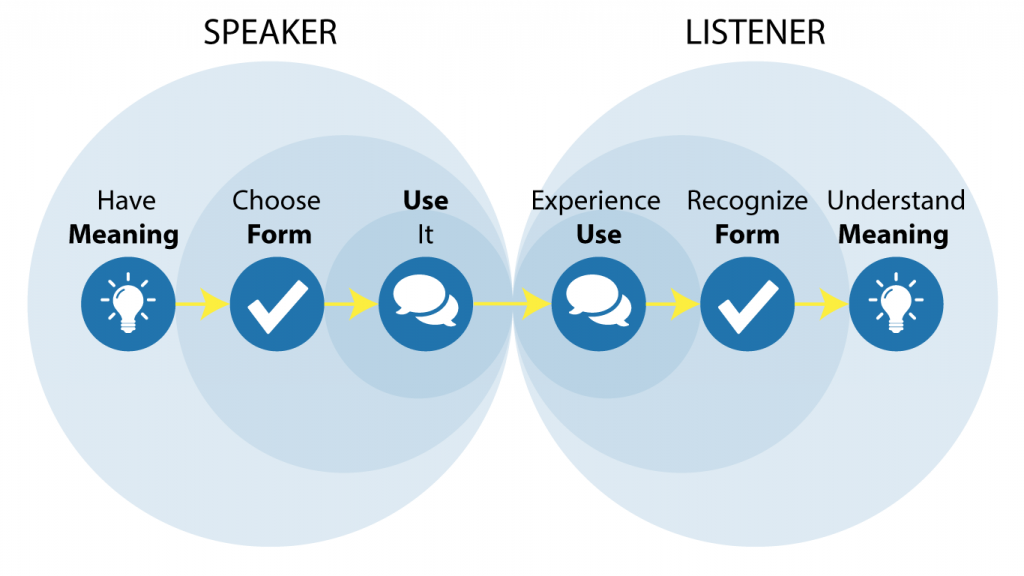

Language is an amazing thing, it gives us the ability to communicate and share our ideas and experiences with others. Understanding the connections between form, meaning and use helps learners develop a sense of how a language works and become more effective communicators.

Expert speakers know and use many grammatical forms. They understand the meanings of these forms and use them for effective communication. In order to use the language well, we need sound knowledge of the forms and what they mean.

The standard approach that grammar books take is to present a form and its uses. Rules are provided so students can memorize when to use each form. This is all well and good if you need to memorize some structures and pass a test, but for many learners this meaning-neglecting approach misses the main point of their study and learners have difficulty expressing themselves.

Having knowledge of forms and their uses is helpful, but to be truly proficient in a language, this is not enough. It is important that learners do not underestimate the importance of meaning. And obviously, not understanding what words and phrases mean makes communicating more difficult. So, in order to become better communicators, learners should deepen their knowledge of words and phrases and what they mean.

The difference between meaning and use

It can often be difficult to see the difference between meaning and use, and resources may say that a phrase means something, when in fact, that is not it’s core meaning, but a common use.

For example, let’s look at the phrase “used to”.

Merriam Webster defines it as:

1 —used to say a situation existed in the past but does not exist now

2 —used to say something happened repeatedly in the past but does not happen now

They have given two common uses (“used to say…”), but what about the meaning? People read it in a dictionary so they assume that the dictionary will tell them what the phrase means, but really, the dictionary only tells us two similar situations in which it can be used.

How do we find the meaning?

It is sometimes difficult to find meaning with grammar resources and dictionaries. They often choose examples to match their explanations of the target use. Sentences that don’t match the explanation are not included. However, this is backwards. As children we learn by being exposed to the full range of uses, and from there we develop our sense of what it means. It’s hard to understand anything if you don’t have all the information.

In order to truly understand the meaning, we need the full range of uses. And from these uses, we can develop a stronger sense of what it means.

We can ask ourselves questions that push the boundaries of dictionary definitions.

For “used to”, dictionaries typically say that it doesn’t happen/exist now. Is that true? Can we think of any examples where it still exists now?

Here are some that came to mind for me.

1. “When he was young, Jim used to practice soccer a lot. He’s a professional soccer player now.”

2. “Do you want to get a coffee?” “Yeah, there used to be a good cafe near here. I hope it’s still there.”

3. “After the accident, he can still do all the things he used to do.”

These are different uses to the dictionary definition.

– talking about the past to emphasize that it happened during that time.

– saying how it was over a period of time in the past because we don’t know about the present.

– comparing a period of time in the past with the present (like the dictionary definition) but the point is that it still happens now.

If we start with a simple sentence like “I played soccer” and compare it with “I used to play soccer” we can see that the only meaning in the words is that with “used to”, it’s about a period of time (many events). The sentence with “I played” is less clear and it could be a one-time event or it could have happened many times depending on the context.

We introduce the form (“used to”) with a range of examples.

Through the examples, the learner can see that we are simply saying that something happened or existed over a period of time in the past. This is the meaning.

Once we understand the meaning, we can understand the uses and how it helps us communicate:

– talk about a past period of time because: it’s different from the present, it is important, the present is unknown, or the past and present are the same.

More on used to.

Advantages of meaning-based grammar explanations

Presenting many uses may seem more complex, and some teachers may prefer to focus heavily on what they feel the students are likely to use or encounter. Practical forms and their uses are important, focusing solely on them is not only limiting, but it doesn’t accurately represent how language functions as a system.

When our goal is for students to find meaning, it fits with the “language as a system” line of thinking. Forms and their meaning can be used in a range of situations.

Students can direct their attention to the meaning encoded in the words. Although uncovering this meaning is more complex than memorizing a usage rule, understanding the meaning can make the language seem simpler.

Each word or phrase typically has one core meaning, and this meaning can be applied to a range of uses.

Instead of trying to learn every possible use for a range of phrases, learners only need to focus on one meaning, and from this meaning the uses seem reasonable instead of random.

And when more than one phrasing is possible, learners can consider the core meanings of each phrase and understand nuance. They understand the meaning more deeply. A deeper understanding of meaning allows for clearer communication.

Check out my book – Real Grammar: Understand English. Clear and simple.

When communicating, meaning comes first

Let’s think about the process of communication in simple terms.

I have a thought in my head. I want to share this thought with another person. We can easily do this through language. When we communicate choose words to express our thoughts.

- It all starts with meaning. The meaning is in the speaker’s head.

- The speaker chooses forms that represent this meaning.

- They use these forms.

- The listener hears the language.

- They recognize the forms that the speaker is using.

- They understand the meaning of these forms in this situation.

If all goes well, the speaker has successfully shared their thoughts with the listener.

In terms of communication, meaning is crucial. Without meaning, language is pointless.

When the connections in our heads between the form and meaning are strong, we better understand the language being used, and use phrases more appropriately when we communicate.

The form-meaning connection

As children, we develop strong connections between forms and meanings. In short, we learn what words mean. And this is all words, from vocabulary to grammatical words.

I remember in school, teachers told us that we should not say, “Can I go to the bathroom?” It is correct to say, “May I go to the bathroom?” They tried to give us a rule for when to use a form. It failed. Everyone I know still says, “Can I go to the bathroom?” because it makes sense to do so. There is a strong form-meaning connection that we developed as children by being exposed to many uses of the word “can”, and this meaning applies to this situation. When communicating, meaning is important. We often ignore form-usage rules.

However, with a second language, many books are all about form-usage rules. So, developing good form-meaning connections often doesn’t get enough attention. In many books, the focus is on “correct usage”. And as a result, learners may often know what correct usage is when they do a test, but many have trouble putting sentences together and communicating.

It is important to develop a good understanding of the forms and what they mean.

Learning in context

When learners experience authentic language in use, the first step is to recognize the forms. When learners recognize forms, they can think about how the form and meaning are connected and how it applies to the situation. The language should simple enough for learners to be able to decode the meaning in context. This is often referred to as comprehensible input. When learners understand the overall meaning of the words in context, they can then guess the meanings of forms they don’t know or are unsure of.

When learners are unfamiliar with the meaning of a form, a resource such as Real Grammar: Understand English. Clear and simple. can be used to help them see how the form relates to other forms they know and see the meaning that it adds to sentences. Sometimes learners may be completely unsure of what a form means. Sometimes the use doesn’t fit with what they thought the form meant. In either situation, they can then make some guesses about what it might mean, then consult the book for a quick explanation and more examples to help them pinpoint a clearer meaning of the form.

Once learners better understand the core meaning, they can use their knowledge to help them decode the meaning when hear or read the form being used in other situations. Thinking about the use of the form and its core meaning helps learners see why people choose to use it.

Raising awareness of forms

The forms exist, but there are no guarantees that a learner will notice them and think about their meanings. There are often forms in a learner’s L2 that don’t exist in their L1. So, learners may not give them much attention as they don’t see their value.

The learner can communicate without the form in L1, so it is hard for them to apply the form when communicating in L2. They focus more on the meaning, so they often choose words that get the general meaning across, but speak in an unnatural way that is more difficult for listeners to understand because it is missing several grammatical forms or features.

Looking into these forms by presenting them in class or reading about them allows learners to be aware that they exist, think about their meanings and discover why they are useful parts of the language. This improves the learner’s knowledge of the language and ability to communicate. When the learner understands why a form is useful by understanding its meaning, they are more inclined to use it themselves. Traditional grammar often focuses on usage rules and remembering what is the “correct” form. However, understanding how the form improves communication gives learners far more reason to want to apply it to the language they use.

For this reason, it is important to use a book that is descriptive rather than prescriptive, so learners can understand the flexible nature of language. Use a book that emphasizes learning the meanings of the forms and how they are used.

Well-chosen examples can pinpoint the differences between the form in question and other forms, which allows learners to develop a stronger sense of the core meaning of the form and the ways this core meaning is often applied in context.

Once learners are aware these exist, they are easier to notice in real-life context, and because the learner is developing knowledge of the core meaning, they will deepen this knowledge every time they encounter the form.

Real-life communication: forms are chosen, not prescribed.

Learners often rely on translation rules that convert L1 features to L2. But it doesn’t work well. We often can’t simply say that when you say X in L1, use Y in L2. The two languages express meaning in different ways.

It’s not a matter of just using different words. Learners studying English need to look at the situation from an English-speaking perspective and make choices that present the meaning clearly in the English way.

Many aspects of grammar are choices, such as the choice of tense, choice of modal verbs (can/could, will/would etc.) and the choice of prepositions (in, on, at, to, for etc.) We choose these grammatical features because they help us express the intended meaning. And these are the features that learners often find difficult.

Sometimes learners aren’t sure which structure to use, or use language in a way that is hard to understand or ambiguous. This may indicate that they don’t know the core meaning of the structure, or that they might be unaware of related structures that would express this meaning with more clarity. At this point learners can look at how the form is used by English speakers.

By looking at a range of examples learners can find the core meaning of the grammatical feature that always holds true. It is important that they go deeper and understand the meaning. Understanding the meaning behind the form allows them to understand the connection between form and use. They can then explore ways of using the feature in different contexts to express a range of ideas.

According to traditional grammar, a word is defined as, “the basic unit of language”. The word is usually a speech sound or mixture of sounds which is represented in speaking and writing.

Few examples of words are fan, cat, building, scooter, kite, gun, jug, pen, dog, chair, tree, football, sky, etc.

You can also define it as, “a letter or group/set of letters which has some meaning”. So, therefore the words are classified according to their meaning and action.

It works as a symbol to represent/refer to something/someone in the language.

The group of words makes a sentence. These sentences contain different types of functions (of the words) in it.

The structure (formation) of words can be studied with Morphology which is usually a branch (part) of linguistics.

The meaning of words can be studied with Lexical semantics which is also a branch (part) of linguistics.

Also Read: What is a Sentence in English Grammar? | Best Guide for 2021

The word can be used in many ways. Few of them are mentioned below.

- Noun (rabbit, ring, pencil, US, etc)

- Pronoun (he, she, it, we, they, etc)

- Adjective (big, small, fast, slow, etc)

- Verb (jumping, singing, dancing, etc)

- Adverb (slowly, fastly, smoothly, etc)

- Preposition (in, on, into, for, under, etc)

- Conjunction (and, or, but, etc)

- Subject (in the sentences)

- Verb and many more!

Now, let us understand the basic rules of the words.

Rules/Conditions for word

There are some set of rules (criteria) in the English Language which describes the basic necessity of becoming a proper word.

Rule 1: Every word should have some potential pause in between the speech and space should be given in between while writing.

For example, consider the two words like “football” and “match” which are two different words. So, if you want to use them in a sentence, you need to give a pause in between the words for pronouncing.

It cannot be like “Iwanttowatchafootballmatch” which is very difficult to read (without spaces).

But, if you give pause between the words while reading like, “I”, “want”, “to”, “watch”, “a”, “football”, “match”.

Example Sentence: I want to watch a football match.

We can observe that the above sentence can be read more conveniently and it is the only correct way to read, speak and write.

- Incorrect: Iwanttowatchafootballmatch.

- Correct: I want to watch a football match.

So, always remember that pauses and spaces should be there in between the words.

Rule 2: Every word in English grammar must contain at least one root word.

The root word is a basic word which has meaning in it. But if we further break down the words, then it can’t be a word anymore and it also doesn’t have any meaning in it.

So, let us consider the above example which is “football”. If we break this word further, (such as “foot” + “ball”), we can observe that it has some meaning (even after breaking down).

Now if we further break down the above two words (“foot” + “ball”) like “fo” + “ot” and “ba” + “ll”, then we can observe that the words which are divided have no meaning to it.

So, always you need to remember that the word should have atleast one root word.

Rule 3: Every word you want to use should have some meaning.

Yes, you heard it right!

We know that there are many words in the English Language. If you have any doubt or don’t know the meaning of it, then you can check in the dictionary.

But there are also words which are not defined in the English Language. Many words don’t have any meaning.

So, you need to use only the words which have some meaning in it.

For example, consider the words “Nuculer” and “lakkanah” are not defined in English Language and doesn’t have any meaning.

Always remember that not every word in the language have some meaning to it.

Also Read: 12 Rules of Grammar | (Grammar Basic Rules with examples)

More examples of Word

| Words List | Words List |

| apple | ice |

| aeroplane | jam |

| bat | king |

| biscuit | life |

| cap | mango |

| doll | nest |

| eagle | orange |

| fish | pride |

| grapes | raincoat |

| happy | sad |

Quiz Time! (Test your knowledge here)

#1. A word can be ____________.

all of the above

all of the above

a noun

a noun

an adjective

an adjective

a verb

a verb

Answer: A word can be a noun, verb, adjective, preposition, etc.

#2. A root word is a word that _____________.

none

none

can be divided further

can be divided further

cannot be divided further

cannot be divided further

both

both

Answer: A root word is a word that cannot be divided further.

#3. A group of words can make a ___________.

none

none

sentence

sentence

letters

letters

words

words

Answer: A group of words can make a sentence.

#4. Morphology is a branch of ___________.

none

none

Linguistics

Linguistics

Phonology

Phonology

Semantics

Semantics

Answer: Morphology is a branch of Linguistics.

#5. The meaning of words can be studied with ___________.

none

none

both

both

Morphology

Morphology

Lexical semantics

Lexical semantics

Answer: The meaning of the words can be studied with Lexical semantics.

#6. The word is the largest unit in the language. Is it true or false?

#7. Is cat a word? State true or false.

Answer: “Cat” is a word.

#8. A word is a _____________.

group of paragraphs

group of paragraphs

group of letters

group of letters

group of sentences

group of sentences

All of the above

All of the above

Answer: A word is a group of letters which delivers a message or an idea.

#9. A word is usually a speech sound or mixture of it. Is it true or false?

#10. The structure of words can be studied with ___________.

Morphology

Morphology

both

both

Lexical semantics

Lexical semantics

none

none