5 min read

We all have little tricks we use to help us in our daily lives. Some of these strategies help us prevent problems before they happen, like setting a timer on the oven so we won’t forget to take out the roast. Other strategies allow us to solve problems after they arise, like turning the TV down when we can’t hear someone talking from the next room. The more strategies we know, the more likely we are to successfully solve problems.

The Problem: Word-Finding Difficulties

For people with aphasia, the most common problem is not being able to think of the word they want. They might try to solve this problem by using a filler word: that thing, the whatchamacallit, oh you know, whatsherface. These generic words and phrases are devoid of meaning, so they fail to communicate the intended message. When communication breaks down, it’s time to use a strategy.

The Treatment: Word-Finding Strategies

There are many word-finding strategies people with aphasia can use when they can’t think of the word they want to say. Each person will find some strategies more helpful than others, so it’s a good idea to practice them all to learn which ones work best for you. Often a combination approach is most useful, trying one and then another. Each strategy gives a bit more information to the listener and stimulates the area of the brain that’s refusing to give up the word.

Here are 10 helpful word-finding strategies for people with aphasia:

Delay

Just give it a second or two. With a bit of extra time, the word may pop out on its own. Be patient with yourself, and ask your partner to give you time.

“Do you have any… um… oh… one sec… any scissors?”

Describe

Give the listener information about what the thing looks like or does. Any extra information can help them know what you’re talking about. It may even help you to say the word.

“Do you have any… oh dear, those things that cut? Scissors!”

Association

See if you can think of something related. Even if it’s not quite right, it may prompt the word or convey the meaning.

“Do you have any… ah my… they’re not knives, but like that?”

Synonyms

Think of a word that means the same or something similar.

“Do you have any…clippers?”

First Letter

Try to write or think of the first letter of the word. Scan the alphabet to see if any letter triggers anything for you.

“Do you have any… (traces an S in the air)… scissors?”

Gesture

Use your hands or body to act out the word, like playing a game of charades. Even gesturing with your hands in a non-specific way or tapping the table may help activate the brain.

“Do you have any… (makes cutting gesture with fingers)?”

Draw

Sketch out a quick picture of what you’re trying to say. You don’t have to be an artist to use drawing to communicate.

“Do you have any… (draws scissors on a notepad)?”

Look it Up

Think if there’s somewhere the word is written down or pictured. A communication notebook, the Contacts app in your phone, or a ticket stub in your pocket may hold the word.

“Do you have any… (points to scissors in a picture dictionary)?”

Narrow it Down

Give the general topic or category. Is it a person, place, or thing? A family member or a friend? Stating the topic can help your listener predict what you might be trying to say by providing some context.

“Do you have any…oh…they’re office supplies.”

Come Back Later

If you can’t think of the word and your partner can’t guess, it’s okay to give up for now. Our brains work out problems while we do other things, so it’s possible the word will simply pop out later. This is a last resort, so try other strategies first.

“Do you have any… [tries every other strategy]… oh, never mind… I’ll ask you later.”

Download these tips now!

Are these tips useful? Get your free PDF of the Top 10 Word-Finding Strategies for Aphasia.

In addition to receiving your free download, you will also be added to our mailing list. You can unsubscribe at any time. Please make sure you read our Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions.

Training Word-Finding Strategies using Apps

It’s important to practice using word-finding strategies in a supported environment with the help of a speech therapist or trained partner. The more you practice a strategy, the easier it will be to use when you need it. Many of the Tactus Therapy apps for aphasia can be used to practice word-finding strategies in the clinic or at home.

Naming Therapy

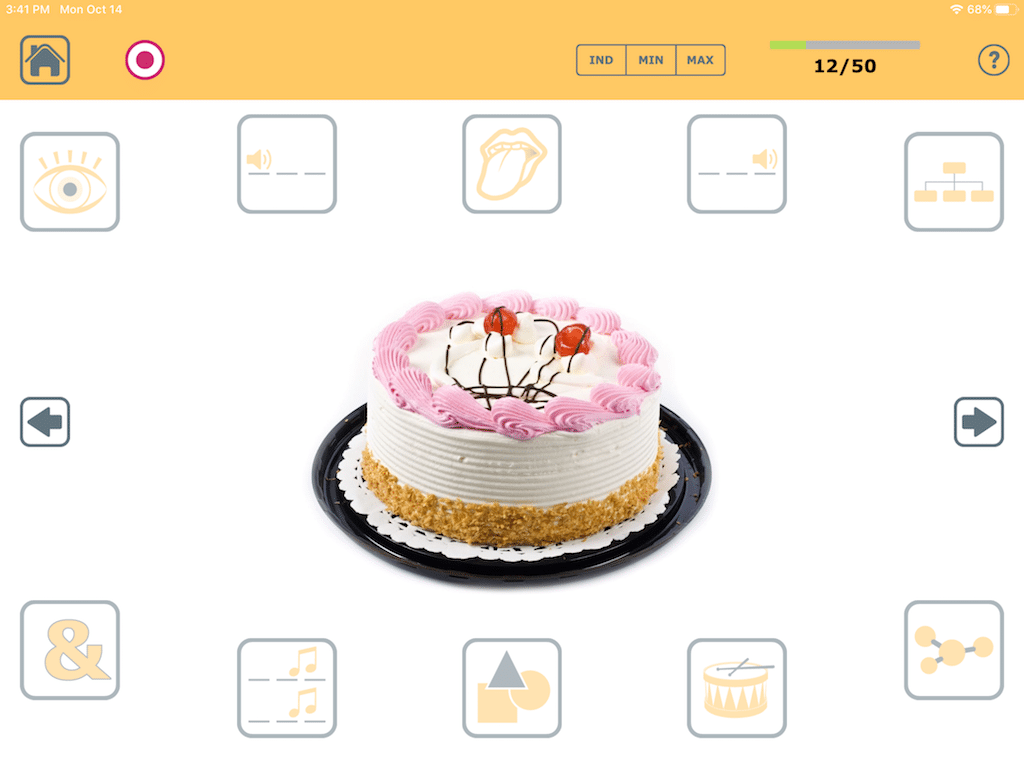

To practice describing (strategy #2), giving associates (strategy #3) and naming the category (strategy #9), use the Describe activity in Naming Therapy. The icons surrounding the pictures ask you questions that make you think about the various features of the objects and actions. The activity is based on the evidence-based treatment of semantic feature analysis.

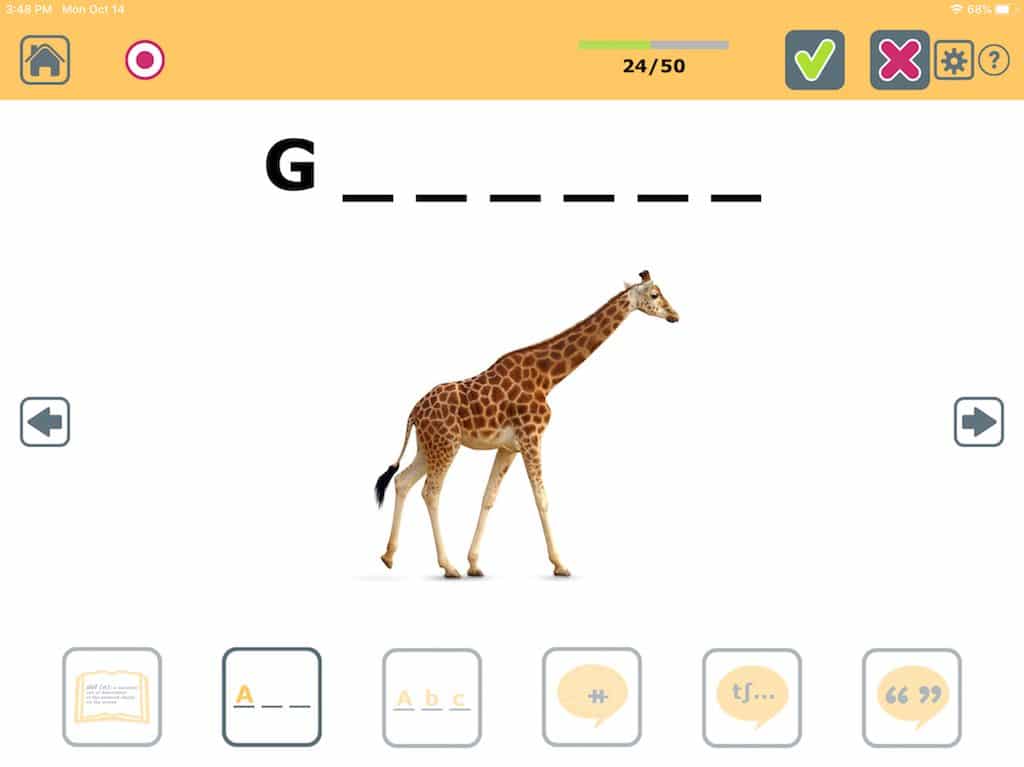

Use the Naming Practice activity to give yourself the first letter of the word (strategy #5). The cueing hierarchy gives you increasingly helpful hints to say the word. If you find the First Letter cue useful, you can start trying to think of the first letter yourself.

Practice gesturing words (strategy #6) using the 700+ words in the Flashcards activity.

Traveler’s dictionaries and ESL photo dictionaries are excellent communication tools. The Oxford Picture Dictionary is a staple, and comes in an app. Other great apps include BabelDeck and ICOON. Put them on your iPhone or iPad so you’ll have them when you need them (strategy #8).

Advanced Naming Therapy

Practice coming up with synonyms (strategy #4) using the Generate activity in Advanced Naming Therapy.

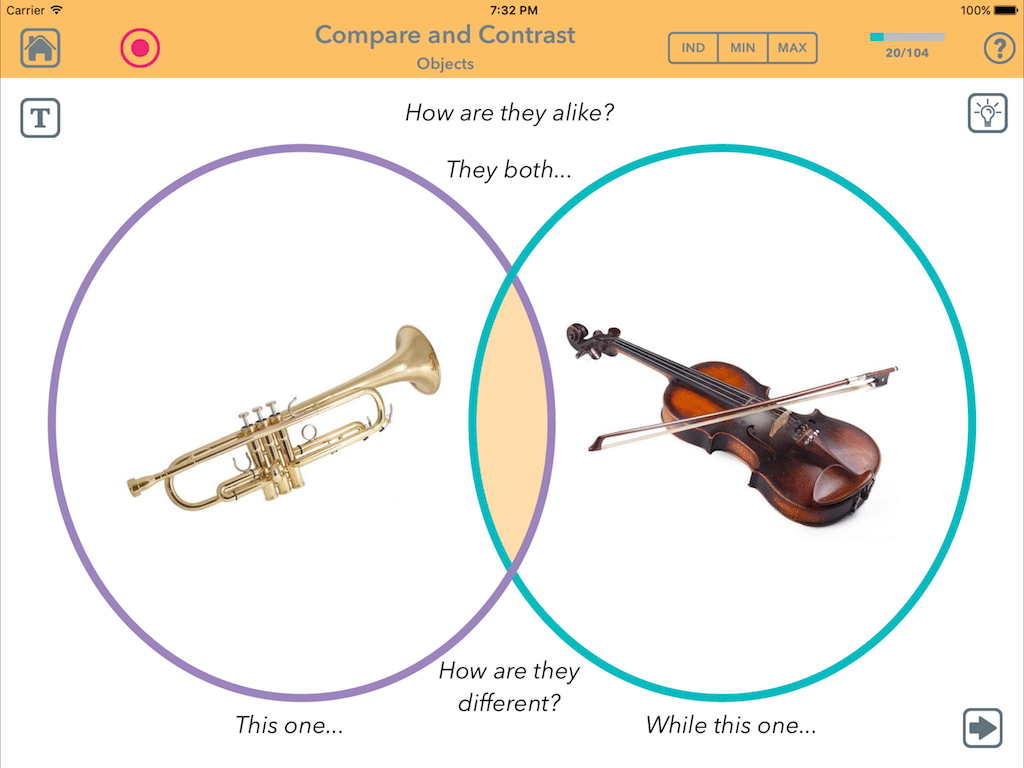

This app also provides an excellent opportunity to practice using all the word-finding strategies when you talk about the fun pictures in the Describe activity and discuss the concepts in the Compare activity.

AlphaTopics

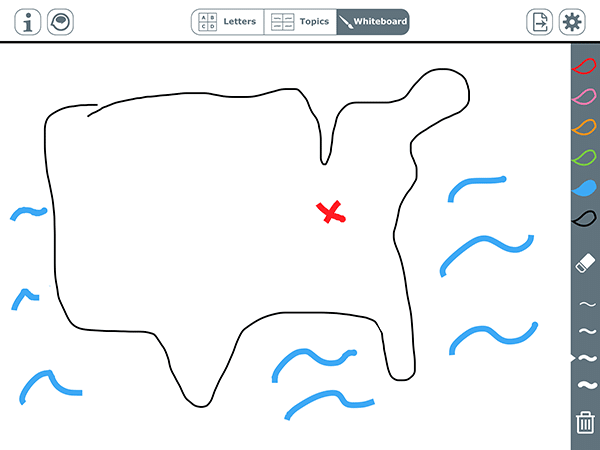

The whiteboard feature of AlphaTopics is perfect for writing the first letter or whole word (strategy #5) or for drawing a quick picture (strategy #7).

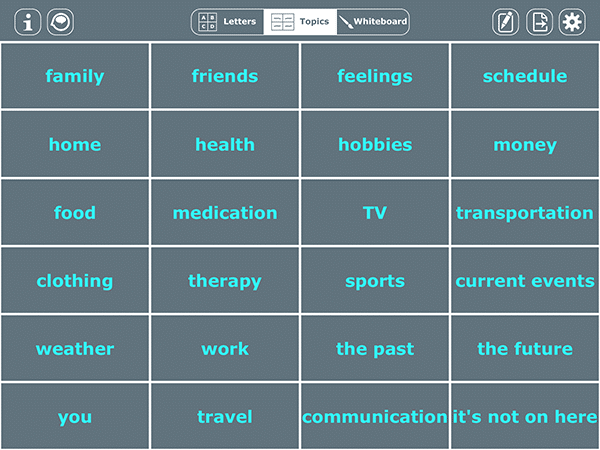

Use the letter board to scan the alphabet (strategy #5) or the topic board to help you narrow-in on the subject (strategy #9).

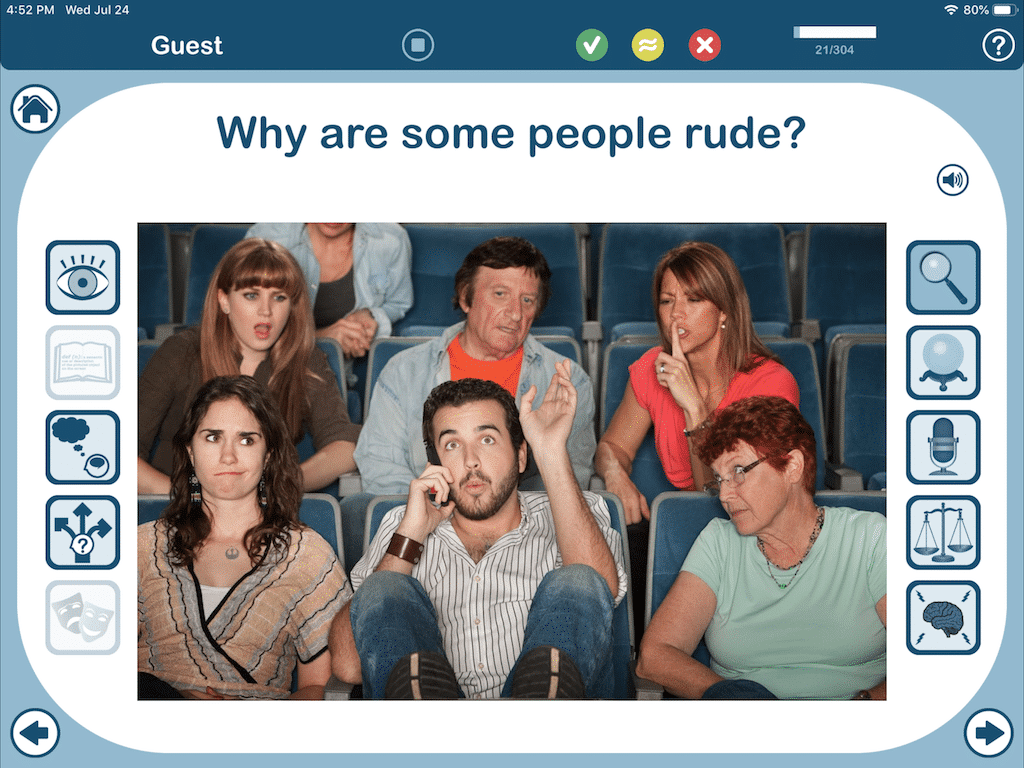

Conversation Therapy

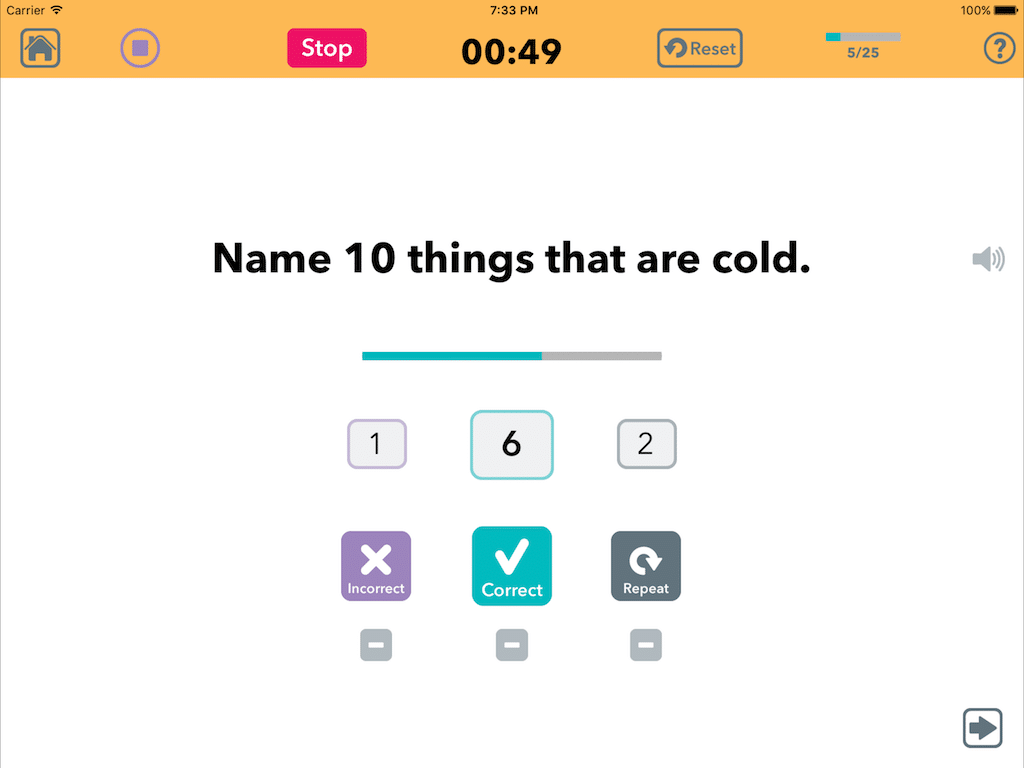

Once you’ve learned all these strategies, you can put them to use by answering the 10 different question types in Conversation Therapy. Ask for a few extra seconds (strategy #1) to think of the word when you get stuck. Then try the other strategies if the words still won’t come.

Not sure which apps to try? Our App Finder can help! Most apps have a free version for you to try.

Like this article? Learn “How To” do a lot more evidence-based speech therapy treatments in our full series of How To articles.

If you liked this article,

Share It !

Megan S. Sutton, MS, CCC-SLP is a speech-language pathologist and co-founder of Tactus Therapy. She is an international speaker, writer, and educator on the use of technology in adult medical speech therapy. Megan believes that technology plays a critical role in improving aphasia outcomes and humanizing clinical services.

More in ‘How To’

Source: US National Library of Medicine NIH ‘Word-finding difficulty: a clinical analysis of the progressive aphasias’ PMCID: PMC2373641 EMSID: UKMS1756 PMID: 17947337 Study Fig. 1

Word-finding problems increase as we age and we become slower in processing information. Retrieving words is difficult although there is not evidence we lose vocabulary as we age. Semantic structure, or the organization of words in memory, does not change. «Older adults probably have more trouble dealing with large amounts of information» and as they age may develop different strategies to accommodate their decline in processing speed and capacity.[1]

Words are said to be on the tip-of-the-tongue.

Word-finding problems «covers a wide range of clinical phenomena and may signify any of a number of distinct pathophysiological processes» and speech and language disturbances when dealing with dementias «present unique diagnostic and conceptual problems that are not fully captured by classical models derived from the study of vascular and other acute focal brain lesions.»[2]

Contents

- 1 Word-finding problems and ME/CFS

- 2 Prevalence

- 3 Presentation

- 4 Symptom recognition

- 5 Notable studies

- 6 Possible causes

- 7 Potential treatments

- 8 See also

- 9 Learn more

- 10 References

Word-finding problems and ME/CFS[edit | edit source]

Word-finding problems is an often reported symptom of ME/CFS. It is also referred to as language impairment. Etiology for language impairment with ME/CFS or fibromyalgia is undetermined at this time, but may be associated with a speech disorder called dysphasia (or aphasia, if it’s severe).[3]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

In a 2001 Belgian study, 75.5% of patients meeting the Fukuda criteria and 80.4% of patients meeting the Holmes criteria, in a cohort of 2073 CFS patients, reported difficulties with words.[4]Katrina Berne reports a prevalence of 75-80% for ‘aphasia’ (inability to find the right word, saying the wrong word) and/or dyscalculia (difficulty with numbers) — although she notes that this symptom is probably underreported and more prevalent than indicated.[5]

Presentation[edit | edit source]

Some examples:

- Increasing use of circumlocutions rather than specific terms (e.g., «I wonder where the thing that goes here is»).

- Use of empty phrases, indefinite terms, and pronouns without antecedents (i.e., referring to something or someone as «it» or «him / her» without first identifying them by name).

- Increased frequency of pauses.[1]

Anomic Aphasia refers to word-finding problems as a type of aphasia. Its typical characteristics are:

- Trouble using correct names for people, places, or things.

- Speaking hesitantly because of difficulty naming words.

- Grammatical skills are unaffected.

- Comprehension is normal.

- Difficulty finding words may be evident in writing as well as speech.

- Reading ability may be impaired.

- Having knowledge of what to do with an object, but still unable to name to the object.

- Severity levels vary from one person to another.[6]

Symptom recognition[edit | edit source]

The Wisconsin ME/CFS Association lists under the cognitive problem portion of Other Common Symptoms «word-finding difficulties» and then goes on to say about many of the symptoms of ME/CFS, «While these symptoms are also experienced occasionally by healthy people, the frequency and severity of their occurrence in people with CFS/FM/MCS is dramatically increased from their occurrence before they became ill.»[7]

The ME Association notes under the bullet Brain and Central Nervous System problems including Cognitive dysfunction such as «word finding abilities».[8]

The Hummingbirds’ Foundation for ME lists word-finding difficulties under Cognitive signs and symptoms.[9]

The Canadian Consensus Criteria lists difficulties with «word retrieval» under Neurological/Cognitive Manifestations as an optional symptom.

Notable studies[edit | edit source]

Possible causes[edit | edit source]

- Stroke

- Head Trauma

- Dementia

- Tumors

- Aging[10]

Potential treatments[edit | edit source]

See also[edit | edit source]

- Aphasia

- Cognitive dysfunction

- Dyscalculia

- Dysphasia

- Memory problems

- Speech difficulties

Learn more[edit | edit source]

- Jun 4, 2018, Victory For ME Disability Claim – U.S. Court Upholds Plaintiff’s Lawsuit After Being Denied Disability[11] — Brian Vastag was able to prove with qEEG and cognitive tests he had «significant problems with visual perception and analysis, scanning speed, attention, visual motor coordination, motor and mental speed, memory, and verbal fluency» winning his long term disability (LTD) claim.[11]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.01.1 «Word-finding problems | Mempowered». mempowered.com. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ↑ Rohrer, Jonathan D.; Knight, William D.; Warren, Jane E.; Fox, Nick C.; Rossor, Martin N.; Warren, Jason D. (2008). «Word-finding difficulty: a clinical analysis of the progressive aphasias». Brain : a journal of neurology. 131 (Pt 1): 8–38. doi:10.1093/brain/awm251. ISSN 0006-8950. PMID 17947337.

- ↑ Dellwo, Adrienne (February 12, 2018). «Do Fibromyalgia and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Cause Language Problems?». Verywell Health. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ↑ De Becker, Pascale; McGregor, Neil; De Meirleir, Kenny (December 2001). «A definition‐based analysis of symptoms in a large cohort of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome». Journal of Internal Medicine. 250 (3): 234–240. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00890.x.

- ↑ Berne, Katrina (December 1, 1995). Running on Empty: The Complete Guide to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFIDS) (2nd ed.). Hunter House. p. 59. ISBN 978-0897931915.

- ↑ «Understanding Word Finding Difficulty: Facts and Solutions». Speech-Therapy-on-Video.com. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ↑ «Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Help». Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Help. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ↑ «Symptoms, testing, and assessment». The ME Association. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ↑ «M.E. symptoms». The Hummingbirds’ Foundation for M.E. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ↑ «Understanding Word Finding Difficulty: Facts and Solutions». Speech-Therapy-on-Video.com. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ↑ 11.011.1 Tillman, Adriane (June 4, 2018). «Victory for ME Disability Claim — U.S. Court Upholds Plaintiff’s Lawsuit After Being Denied Disability». #MEAction. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

Info: 2860 words (11 pages) Nursing Essay

Published: 11th Feb 2020

Reference this

Tagged:

aphasia

A common condition that is an acquired language/communication disorder is known to be Aphasia. This disorder is usually caused from head trauma, brain tumors, stroke, or other neurogenic conditions in which it impairs a person’s speech and language. More adults than children are affected by this devastating disorder. Stroke is known as the number one leading cause of aphasia. Statistics show that over 1 million Americans struggle with the life-changing condition. An incline is expected as population ages in addition to what is now over 200,000 new cases each year. Broca’s aphasia is the most common type of nonfluent aphasia. An individual with non-fluent aphasia suffers with grasping the meaning of spoken words but without severe impairment of connected speech. The frontal lobe of the brain is the primary affected area which leads to several other symptoms. The affected area of the brain is specifically responsible for motor movements. Therefore, trauma to the frontal lobe leads one to experience right-side paralysis of the limbs.

Get Help With Your Nursing Essay

If you need assistance with writing your nursing essay, our professional nursing essay writing service is here to help!

Find out more

It is important for individuals to keep in mind that aphasia does not impair intelligence in any way. The language disorder specifically presents difficulty to understand, speak, read, or write. The human brain is divided into two equal halves, right hemisphere and the left hemisphere. Depending on where the damage is located on the patient determines the affected area. Impaired speech and language is anatomically different. The utmost impairment results in the language centers located in the left hemisphere. However, “Aphasia can also occur as a result of damaging to the right hemisphere; that is often referred to as crossed aphasia, to denote that the right hemisphere is language dominant in these individuals” (American Speech-Language- Hearing Association, 2018). Due to this trauma it is likely that patients with Broca’s aphasia and frontal lobe lesions struggle more with verb naming.

The two main causes of aphasia are stroke and traumatic brain injury. A stroke can occur either as an ischemic stroke or as a hemorrhagic stroke. Blockage that disrupts blood flow to a region of the brain is an ischemic stroke. A hemorrhagic stroke occurs when a ruptured blood vessel damages surrounding tissue in the brain. “According to the National Aphasia Association (n.d.), about 25%-40% of stroke survivors experience aphasia” (ASHA, 2018). Severity of the trauma to the brain depends on if aphasia could be transient or more permanent due to the traumatic brain injury. Frequently, traumatic brain injuries are accompanied by other cognitive challenges due to the involvement of multiple areas of the brain. Aphasic individuals can acquire this condition as simply from a quick concussion or from a hard fall.

There are four main types of aphasias: expressive aphasia, receptive aphasia, anomic aphasia, and global aphasia. Each specific aphasia contributes to a variety of characteristics in which one type can be identified. An individual with Broca’s (expressive) aphasia can comprehend what is being said, but unable to speak fluently due to the function of the brain. They deal with poor or absent grammar, poor syntax, omitting of words, verb or noun usage, word retrieval, phonemic errors called ‘phonemic paraphasias’, and difficulty articulating sound and words. Broca’s aphasia is considered ‘nonfluent’ because it affects the speech production (Healthline 2017). This type of expressive aphasia is the most important of the less severe forms of aphasias. Important skills that are needed through language that are affected with this disorder are attention and memory. These neurobehavioral characteristics are both poor when having Broca’s aphasia. One should note that language skills is caused from damage on the right side of the brain, while lack of memory of attention is caused from damage to the right side. This makes it more challenging for the individuals to develop sentences and process their oral output.

While some people recover from the acquired disorder, others need speech and language treatment. Providing the appropriate treatment to aphasic individuals is crucial after a stroke or other underlying causes of aphasia. While it is critical to provide intensive therapy, it is more imperative to provide a higher number of sessions. The effective amount of therapy significantly improves the individual’s production of speech, comprehension, and functional communication. Word retrieving is one of the most prominent symptoms that individuals have difficulty with and seek treatment for. Kang, Kim, Sohn, Cohen, & Paik, (2011) stated, “It has been reported that conventional word-retrieval training effectively induces partial clinical improvements, but that it rarely leads to complete functional recovery.” The appropriate strategies must be enforced for adequate effectives of word-retrieval protocols. Generally, through literature, therapist focus on single-word noun retrieval and picture naming during treatment. Speech-language pathologist provide the appropriate strategies to provide great progress.

Semantic Feature Analysis (SFA) is a treatment used with individuals with aphasia who struggling with word retrieval problems. This therapeutic technique is used during treatment to work on naming deficits occurring with aphasia. SFA is known to improve naming of targeted items with generalization in order to dictate the stimuli. Another advantage of using this treatment is the educational aspect that individual retrieves from it for accessing semantic networks and self-cueing. The treatment requires the individuals to retrieve features related to trained objects.

An article conducted by Magesh & Patil. (2013) consisted of four participants with aphasia, one female and three males. They were all right-handed, English speaking, and had high school educations. Each participant experienced a single episode of CVA. Treatment was twice per day two to three times per week. With the therapist controlling the session, the subject’s goal was to attempt producing words semantically associated with each target word given. The hypothesis of the study was that an efficient amount of practice would lead the subjects to minimize use of compensatory strategies. The subjects greatly benefited from the treatmen. Theresults of C-SFA (Semantic Feature Analysis) included improved production of nouns, generalization to noun from semantic categories both being untreated, four week duration of improvement after treatment ended. The study concluded participants with Broca’s aphasia improved in formativeness of discourse (Magesh & Patil, 2013).

Patients with word-retrieval benefit from another known treatment named Cathodal Transcranial DC Stimulation (ctDCS). This treatment is suggested to improve picture naming in aphasic patients. This technique eliminates volatility of cortical sites that are stimulated. The double blind, crossover study included ten right-handed patients with post-stroke aphasia. The applied intervention consisted of a week’s long randomized crossover manner allowing no less than one week difference between interventions. The focus of the treatment was to exercise the healthy side of the Broca’s homologue area on the right side with a supraorbital anodal location on the left side. Progression of picture naming task was expected from the post-stroke aphasic patients. The study concluded the positive affect of the word-retrieval treatment on the selected subjects. Cathodal transcranial DC stimulation did not propose any adverse effects per the article (Kang, Kim, Sohn, Cohen, & Paik2011).

Verb Network Strengthening Treatment (VNeST) is given to those with moderate- to- severe aphasia. Edmonds, & Babb (2011) conducted a study that include two participants recruited from the University of Florida Speech and Hearing Clinic. The individuals were diagnosed with aphasia, right-handed prior to stroke, and English speaking. They were examined using a multiple-baseline approach which covered four phases: baseline, treatment of trained items with administration of generalization and control probes, posttreatment probes, and maintenance. The designed protocol generated thematic roles related to the very network that represented relevant event schemas, influencing semantic knowledge that would activate world level forms. Sentence production for pictures and untrained semantically related verbs were the required task for the experimental design. Amongst the two participant in the multiple- baseline approach, both showed progress on the functional communication measure. One participant presented improvement on all generalization measures, while the other subject displayed limited generalization. The study concluded the participants rather did not show equal improvement with other observed participants with more moderate aphasia. The study proposed that Verb Network Strengthening Treatment for Aphasia is more appropriate for those who acquire moderate- to –severe aphasia (Edmonds, & Babb, 2011).

Evidence-based word retrieval treatment is the Cueing Hierarchy Treatment that places cues accordingly from least helpful to the most helpful. It systematically consist of a variety of cues in which aphasic individuals seek their words. Confrontation naming task consist of the therapist presenting the clinician with a picture or an object in representation of the target word. As expected, the client struggles with word retrieval independtly. A study was conducted to determine the effectiveness on syntactic cueing therapy on picture naming and connected speech with aphasic individuals. The study consisted of six individuals with aphasia all who presented with word-finding difficulties. Part of the assessment consisted of using 80 pictures of everyday items that they viewed on a computer screen. Only one word answers were accepted while being recorded. The experiment lasted for six sessions, each involving various components. They concluded that therapy for word-finding impairments needs to facilitate word form with the production of relevant syntactic structures. Through the production of the study researchers established the effectiveness for therapy can enhance word-finding in picture naming and connected speech (Herbert, Webster, & Dyson 2012).

NursingAnswers.net can help you!

Our nursing and healthcare experts are ready and waiting to assist with any writing project you may have, from simple essay plans, through to full nursing dissertations.

View our services

Two treatments were given in the same study to compare the effects for aphasic word retrieval. The purpose of the study was to expect that the use of gestural facilitation of naming (GES) would have an increasing effect of treatment compared to errorless naming treatment (ENT) alone. “Lexical-semantic system impairment will lead to difficulty in both spoken naming and auditory comprehension of words, as well as recognition and production of gestures” (Raymer, McHose, Smith, Iman, Ambrose, & Casselton, 2012). Eight subjects with stroke-induced aphasia and problems with word retrieval were used for the single participant crossover treatment design. The method of the study required evaluation of the two treatments for a daily picture naming/ gesture production probe measure. Additionally, Standardized aphasia test and communication rating scales were administered throughout the experiment (Raymer et. al., (2012).

Errorless naming approaches treatment consisted of the individual viewing a target picture along with the name of the picture. The participant was given a variety of opportunities to rehearse the correct name of the picture by oral reading and repetition. Errors were to be avoided during the training. Therapist considered this semantic-phonological treatment approach given the semantic mechanism and name repetition that builds up to phonological skills. This approach to treatment has been very effective to those who have aphasia. Studies advised that gesture is useful for activation of lexical retrieval between the relation of action and language (Raymer et. al., 2012).

An alternative treatment used in the studied was gestural facilitation of naming. This approached used gesture abililties in order to facilitate the impaired language system. The method consisted of being based off parallel errorless naming treatment but with a gestural component added. Using imitation, manipulation, and modelling, by the clinician the participant acquired word-retrieval skills through the treatment (Raymer et. al., 2012).

Both treatments presented improvements of naming of target words in individuals with semantic and phonological impairments. The treatments did not indicate a discrepancy between each treatment. Studies show satisfaction amongst both treatments to promote word retrieval and verbal production skills in those with aphasia. The participants showed substantial progress throughout various language measures to support the satisfactory of the treatments. “Placing persons in an enriched communication environment, whether itis through the use of errorless naming gestural facilitation, semantic-phonological activities, or orthographic cues, enhances activation of the lexical system and increases the likelihood of future word retrieval success” (Raymer et. al., 2012).

In conclusion, the devastating acquired disorder that leaves individuals with many questions has various treatments for them to reference to. Although only a few treatments were mentioned, it is safe to say that many studies have been conducted in order to provide aphasic patience’s with the proper interventions to help them live a better life. The treatments, etiologies, neurobehavioral characteristics for word finding in individuals with Broca’s aphasia were discussed. All studies represented the effectiveness of treatment options to generalize the word finding for our Broca’s patients. Some treatments will be more beneficial than others depending on the individual.

References

- American Speeh-Language- Hearing Association (2018). Aphasia. Retrived from https://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/aphasia/

- Code, C., & Petheram, B. (2011). Delivering for aphasia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13(1), 3-10.

- Edmonds, L. A., & Babb, M. (2011). Effect of verb network strengthening treatment in moderate-to-severe aphasia. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(2), 131-145.

- Healthline. (2017). Broca’s Aphasia. Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/health/brocas- aphasia

- Herbert, R., Webster, D., & Dyson, L. (2012). Effects of syntactic cueing therapy on picture naming and connected speech in acquired aphasia. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, (4), 609.

- Kang, E. K., Kim, Y. K., Sohn, H. M., Cohen, L. G., & Paik, N. J. (2011). Improved picture naming in aphasia patients treated with cathodal tDCS to inhibit the right Broca’s homologue area. Restorative neurology and neuroscience, 29(3), 141-52.

- Macoir, J., Leroy, M., Routhier, S., Auclair-Ouellet, N., Houde, M., & Laforce, R., Jr. (n.d.). Improving verb anomia in the semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia: the effectiveness of a semantic-phonological cueing treatment. NEUROCASE, 21(4), 448–456. https://doi-org.ezproxylocal.library.nova.edu/10.1080/13554794.2014.917683

- Magesh, R. co., & Patil, G. S.(2013). Efficacy of Semantic Feature Analysis as a Treatment for Word Retrieval Deficits in Individuals with Broca’s Aphasia. Journal of the All India Institute of Speech & Hearing, 32, 114–121.

- Medscape. (2016). Aphasia Clinical Presentation. Retrieved from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1135944-clinical

- Raymer, A. M., McHose, B., Smith, K. G., Iman, L., Ambrose, A., & Casselton, C. (2012). Contrasting effects of errorless naming treatment and gestural facilitation for word retrieval in aphasia. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 22(2), 235–266. https://doi-org.ezproxylocal.library.nova.edu/10.1080/09602011.2011.618306

- Rohde, A., Worrall, L., Godecke, E., O’Halloran, R., Farrell, A., & Massey, M. (2018). Diagnosis of aphasia in stroke populations: A systematic review of language tests. PloS one, 13(3), e0194143. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0194143

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

- APA

- MLA

- MLA-7

- Harvard

- Vancouver

- Wikipedia

- OSCOLA

Reference Copied to Clipboard.

Reference Copied to Clipboard.

Reference Copied to Clipboard.

Reference Copied to Clipboard.

Reference Copied to Clipboard.

Reference Copied to Clipboard.

Reference Copied to Clipboard.

Related Services

View all

Content relating to: «aphasia»

Aphasia has many etiologies, such as stroke, infection, brain abscess, brain tumour, nutritional deficiencies, or toxemia. However, the most common cause of aphasia in adults is cerebrovascular accident, which includes several types and classifications for aphasia.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on the NursingAnswers.net website then please:

Earn 10 Reward Points by commenting the blog post

If you participate in various speech language and education related forums you may frequently see a variation on this question: “How would you assess and treat a child with word finding difficulties?” Before I provide some recommendations on this matter I’d like to talk a little bit about what word-finding is as well as what impact untreated word finding issues may have in a child.

So how do word-finding deficits manifest in children? In a vast variety of ways actually! For starters they could occur at the word level, conversational level or both. Below are just a few examples of word-level errors from German, 2005:

- Error Pattern 1- Lemma Related Semantic Errors

- “Slips of the tongue” or semantic word substitutions such as fox→ wolf; clown → gnome

- Error Pattern 2 – Form Related Blocked Errors

- “Tips of the tongue” or responses characterized by word blocks, pauses, fillers (um, ah, etc), repetitions, metalinguistic or metacognitive comments such as “I know”, “I don’t know”, etc.

- Error Pattern 3 – Form & Segment Related Phonologic Errors

- “Twists of the tongue” which include phoneme omissions, substitutions and additions such as cactus → catus; octopus →opotus, etc.

Further complicating the above may be the speed (some delay or no delay) with which they retrieve words as well as accuracy/inaccuracy of their retrieval once the words are retrieved. Additionally, a number of secondary characteristics may also play a role which include gestures (e.g, miming a word, frustration, etc) as well as extra verbalizations (metalinguistic and metacognitive comments).

At discourse level, students with word-finding deficits typically occupy one of two categories: productive vs. insufficiently productive language users. While their narrative language profile may be marked by frequent pauses, word fillers, as well as word and phrase revisions and repetitions.

Moreover, word-retrieval deficits are not limited to discourse, they are also found in reading tasks. There word-finding issues may manifest as omitted words or almost stuttering/cluttering like behaviors. Interestingly German and Newman (2005; 2007) found that students with word retrieval difficulties are able to successfully correctly identify the words they missed during oral reading tasks in silent reading recognition tasks.

Difficulty coherently expressing oneself can have significant detrimental effect on the child’s academic performance, social relationships and ultimately self-esteem, which without appropriate intervention may potentially lead to poor school performance as well as mental issues (e.g., anxiety, depression, etc.)

So how can word-finding deficits be assessed for free? You can assess word-finding at narrative level using the clinical narrative assessment.

At word level you can adapt single word standardazed tests such as the Expressive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test (EOWPVT) in order to test the efficiency of the student’s word retrieval in single word context. Here, the goal is not necessarily to test their expressive vocabulary knowledge but rather to see what type of word finding errors the students are making as they are attempting to correctly recall the visually shown word. Depending on the extent of the child’s word finding deficits you may have some very useful information to derive from the presentation of this test.

To illustrate, I recently informally administered applicable portions of this test to a four-year old Russian speaking preschooler. Based on his performance I was able to determine that his errors are primarily Error Pattern 3 – Form & Segment Related Phonologic Errors or Twists of the tongue”. This was further confirmed when I had the child to participate in the narrative retelling task.

So where can we find reputable evidence-based practice information on effective assessment and treatment strategies for word finding deficits? Start with Dr. Diane German’s website, entitled Word Finding. She has a lot of good information to offer there for free to both speech language professionals as well as parents. Take a look at her recommended materials and resources, they are very helpful when it comes to assessing and treating children with word finding deficits. Now have fun and evidence-base practice on!

PS. Calculating percentage of word-finding difficulties in children.

Dr. German recommends the following procedure: “Obtain a language sample of 50 T-units (kernel sentence + subordinate clause) in length using stimuli of interest to the learner (or use one you have as long as all utterances in the sample are included). Then asses each T unit for the presence of one or more of the following 7 WF behaviors in discourse: repetitions, revisions (reformulations), substitutions, insertions (comment that reflects on the WF process like I cannot think of it, etc. ), time fillers (um, er, uh), delays with in the T unit, and empty words (thing, stuff). Learners with WF difficulties manifest one or more WF behaviors in 33% or more of their T units (often 40% – 50%). Typical language learners display WF behaviors in 19% or less of their T-Units (German, 1991)“ (German, 2015: SIG 16 Topic: Assessing Word-Finding Skills)

Helpful Related Materials:

- Clinical Assessment of Narratives in Speech Language Pathology

- Narrative Assessments of Preschool, School-Aged, and Adolescent Children

- Narrative Assessment Bundle

- The Checklists Bundle

- Creating Functional Therapy Plan

References:

- Dockrell, J.E., Messer, D., George, R. & Wilson, G. (1998). Notes and Discussion Children with word-finding difficulties-prevalence, presentation and naming problems. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 33 (4), 445-454.

- German, D.J. (2001) It’s on the Tip of My Tongue, Word Finding Strategies to Remember Names and Words You Often Forget. Word Finding Materials, Inc.

- Dr. German’s Word Finding Website: http://www.wordfinding.com/

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are the personal opinion of the author. The author is not affiliated with dr. Diane German nor PRO-ED publications in any way and was not provided by them with any complimentary products or compensation for this post.

Alzheimer’s disease can cause aphasia, which is a decline in language function due to brain disease. Alzheimer’s disease is progressive dementia that causes impaired memory, judgment, and general cognitive functioning.

Aphasia in Alzheimer’s disease often begins with word-finding problems, including difficulty choosing or recalling the right word. It can progress affect someone’s ability to express themselves, and it can involve comprehension too. Brain tumors, infections, and injuries can also cause aphasia,

This article explains some of the characteristics, symptoms, and causes of aphasia. It also describes how aphasia is diagnosed and treated.

What Is Aphasia?

Aphasia is a language deficit caused by brain disease or brain damage. It ranges in severity, meaning it can be very mild or so severe that communication is nearly impossible. There are several types of aphasia, each caused by damage to a specific region in the brain that controls certain features of language.

Aphasia is usually associated with stroke, head trauma, or dementia. It is rarely associated with other diseases, such as multiple sclerosis or Parkinson’s disease. The condition takes several forms:

- Dementia-associated aphasia is gradual and is associated with other effects of dementia, such as personality changes and memory loss.

- Aphasia from a stroke happens abruptly, when an area of the brain becomes damaged due to insufficient blood supply.

- Aphasia due to head trauma can have fluctuating symptoms.

Recap

Aphasia is an «acquired communication disorder that impairs a person’s ability to process language… Aphasia impairs the ability to speak and understand others.» It does not affect intelligence.

Symptoms

Aphasia can manifest with difficulty in comprehension and/or expression. Aphasia that’s associated with dementia includes word-finding problems. It may cause a person to hesitate at length, and mentally search for the right word, before speaking.

Alternatively, when they try to speak, they may use an incorrect word that starts with the same letter of the desired word («floor» instead of «flower» or «sack» instead of «sand»). Or they may describe what the word means («You know, the thing on the wall with the numbers and the time»).

Word-finding aphasia may manifest with:

- «Tip of the tongue» experiences

- Difficulty naming objects or people

- Impaired understanding of spoken or written words

- Diminished ability to write or writing the wrong words

- Hesitancy in speaking

Someone with early dementia may have greater difficulty speaking than comprehending. But sometimes, it’s hard to be sure. They may simply appear as if they understand (for example, by nodding their head).

Other early signs of Alzheimer’s dementia can also appear along with aphasia. These signs include forgetfulness, confusion, emotional outbursts, personality changes, and a sudden lack of inhibition.

Recap

Word-finding problems may cause someone with aphasia to hesitate at length and mentally search for the right word before speaking.

When to Seek Medical Help

Many adults can relate to the feeling of being unable to retrieve a word. They may call it a «brain jam» or «brain fog.» But if you’ve noticed this happening to a loved one with greater frequency, start taking note of when and how often it occurs. Does it happen when they’re tired, multi-tasking, or extremely stressed? Or does it happen when they’re calm and relaxed?

If you see a pattern that is truly interfering with their ability to communicate effectively, it may be helpful to ask a mutual acquaintance if they’ve noticed any changes in your loved one’s behavior before consulting a healthcare provider.

Types and Causes

Aphasia occurs when areas of the brain that control language are damaged, making it difficult to speak, read, and write. The four main types of aphasia are:

- Anomic aphasia, or when someone has difficulty remembering the correct word for objects, places, or events

- Expressive aphasia, or when someone knows what they want to say but have trouble saying or writing what they mean

- Global aphasia, or when someone lacks the ability to speak, read, write, or understand speech

- Receptive aphasia, or when someone hears someone speaking or reads something in print but cannot make sense of the words

Aphasia due to dementia is caused by the gradual degeneration of cells in the frontal lobe and limbic system of the brain. These areas control memory, judgment, problem-solving, and emotions. It generally does not follow the speech pattern of other types of aphasia.

With dementia, impairment of semantic memory (the memory for understanding and recognizing words) is a significant contributor to word-finding difficulties.

Primary progressive aphasia is a specific type of aphasia caused by dementia that results from degeneration of the frontal and temporal regions. It typically occurs in frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and also in Alzheimer’s disease. It starts gradually, usually with word-finding difficulty and problems with naming and pronunciation. As it progresses, people develop problems with comprehension, reading, and writing. They may also lose their ability to speak.

Diagnosis

Word-finding aphasia is a common symptom of early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, but there are others. Your doctor will ask about your loved one’s symptoms and may want to speak with family members. Interestingly, aphasia affects a person’s second language before it begins to affect their first language.

The doctor will also consider your loved one’s baseline language ability during the assessment. For example, your loved one would be expected to demonstrate familiarity with words in their field of work. Forgetting words that they’ve presumably used often and easily could be a warning sign of dementia or aphasia. The evaluation might also include;

- A physical examination, including a comprehensive neurological examination, to help distinguish different causes of aphasia

- The Verbal Fluency Test or the Boston Naming Test

- An online dementia test called the Self-Administered Gerocognitive Exam SAGE test. It evaluates thinking abilities.

- Diagnostic tests, such as brain imaging tests, if there is a concern that your loved one might have had a stroke.

Multiple Answers Possible

Unlike traditional tests that you may remember from school, there are multiple correct answers to some questions on the SAGE test. A physician should score a SAGE test.

Prevention

The best ways to try to prevent aphasia mirror prevention tips for many other diseases. And they all boil down to one point: Live a healthy lifestyle. In this case, your loved one should focus on reducing the risk of stroke. By now, you may know the drill:

- Eat a healthy, balanced diet.

- Maintain a healthy weight.

- Exercise regularly.

- Quit smoking and drinking (if applicable).

- Be proactive about keeping blood sugar, cholesterol, blood sugar, and blood pressure levels low.

- Stay mentally active with activities like puzzles and word games.

- Prevent falls and head injuries.

Exercise Matters

Exercising results in more blood flowing to the brain, which is a good thing. «Even a small amount of exercise each week is enough to enhance cognitive function and prevent aphasia.»

Treatment

If your loved one is at risk for stroke, lifestyle factors and medication can reduce the risk. Even if aphasia is caused solely by dementia, having a stroke can substantially worsen the symptoms.

Treatment for aphasia involves a multidisciplinary approach that might call for medication and therapy. A doctor can prescribe medication for the treatment of dementia, which may help slow the progression of the disease.

Otherwise, aphasia is treated by working with a speech and language therapist to improve your loved one’s ability to communicate with others. This should be an ongoing process, especially if the underlying cause of the aphasia continues to progress.

Research Continues

Researchers are studying two types of brain stimulation—transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation—to help improve recall ability.

Coping

No one ever said that it’s easy to care for or even be in the presence of someone whose communication skills are faltering. Being patient and supportive is your best coping strategy. For example:

- Maintain eye contact and adopt a calm tone of voice.

- Use short, simple words.

- Don’t offer guesses, rattle off word choices, or finish sentences. It’s easier than you think to frustrate and overwhelm someone with aphasia. Give your loved one time to speak.

- Don’t rolls your eyes, snicker, or show any other signs of impatience when you know your loved one is doing their best to communicate.

- Incorporate facial cues, gestures, and visual aids into communication rather than relying only on words.

- Ask for verbal and non-verbal clarification. For example, if your loved one says that their «fig» hurts, ask if their finger hurts and point to it.

- Don’t argue, even if your loved one baits you. Try to appreciate just being together, even when you aren’t talking.

Recap

When all is said and done, «you may find that the best ways to communicate are with your presence, touch, and tone of voice.»

Summary

Aphasia occurs when areas of the brain that control language are damaged. This impairs the ability to speak and understand. The symptoms often include an inability to understand spoken or written words and difficulty speaking or writing, The four main types of aphasia include expressive aphasia (someone knows what they want to say but have trouble saying or writing it); receptive aphasia (when someone hears a voice or sees the print but can’t make sense of the words); anomic aphasia (difficulty using the correct word for objects, places, or events); and global aphasia (when someone cannot speak, understand speech, read, or write). Prevention and treatment for aphasia involve a multidisciplinary approach that might call for medication and therapy.

A Word From Verywell

Aphasia can keep loved ones guessing, but you can eliminate one of the mysteries by taking your loved one to get their hearing and vision checked. If these senses are deteriorating, your loved one may feel more confused, agitated, or withdrawn than necessary. Faltering hearing or eyesight may also explain some behaviors that you’ve been attributing to aphasia. Plus, hearing and vision problems are usually simple to improve.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Isn’t it common to use the wrong words as you get older?

Absolutely. Sometimes, people use the wrong words when speaking due to mild dementia, strokes, or simple distraction. This can become more common as you get older.

-

What is it called when you have word-finding difficulty and use the wrong words when speaking?

When this happens repeatedly, it is called anomic aphasia.

-

How do you treat word-finding difficulty?

You can work with a speech and language therapist. You can practice using more words when you speak and when you write. You can also read, talk to people about a variety of topics, and listen to programs about topics of interest to keep your vocabulary strong.