| Tower of London | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Location | London Borough of Tower Hamlets |

| Coordinates | 51°30′29″N 00°04′34″W / 51.50806°N 0.07611°WCoordinates: 51°30′29″N 00°04′34″W / 51.50806°N 0.07611°W |

| Area |

|

| Height | 27 metres (89 ft) |

| Built |

|

| Visitors | 2,984,499 (in 2019)[1] |

| Owner | King Charles III in right of the Crown[2] |

|

UNESCO World Heritage Site |

|

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv |

| Designated | 1988 (12th session) |

| Reference no. | 488 |

| Country | England |

| Europe and North America | |

|

Listed Building – Grade I |

|

|

Listed Building – Grade II |

|

|

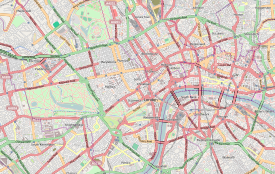

Location of the castle in central London |

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty’s Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separated from the eastern edge of the square mile of the City of London by the open space known as Tower Hill. It was founded toward the end of 1066 as part of the Norman Conquest. The White Tower, which gives the entire castle its name, was built by William the Conqueror in 1078 and was a resented symbol of oppression, inflicted upon London by the new Norman ruling class. The castle was also used as a prison from 1100 (Ranulf Flambard) until 1952 (Kray twins),[3] although that was not its primary purpose. A grand palace early in its history, it served as a royal residence. As a whole, the Tower is a complex of several buildings set within two concentric rings of defensive walls and a moat. There were several phases of expansion, mainly under kings Richard I, Henry III, and Edward I in the 12th and 13th centuries. The general layout established by the late 13th century remains despite later activity on the site.

The Tower of London has played a prominent role in English history. It was besieged several times, and controlling it has been important to controlling the country. The Tower has served variously as an armoury, a treasury, a menagerie, the home of the Royal Mint, a public record office, and the home of the Crown Jewels of England. From the early 14th century until the reign of Charles II in the 17th century, a procession would be led from the Tower to Westminster Abbey on the coronation of a monarch. In the absence of the monarch, the Constable of the Tower is in charge of the castle. This was a powerful and trusted position in the medieval period. In the late 15th century, the Princes in the Tower were housed at the castle when they mysteriously disappeared, presumed murdered. Under the Tudors, the Tower became used less as a royal residence, and despite attempts to refortify and repair the castle, its defences lagged behind developments to deal with artillery.

The zenith of the castle’s use as a prison was the 16th and 17th centuries, when many figures who had fallen into disgrace, such as Elizabeth I before she became queen, Sir Walter Raleigh, and Elizabeth Throckmorton, were held within its walls. This use has led to the phrase «sent to the Tower». Despite its enduring reputation as a place of torture and death, popularised by 16th-century religious propagandists and 19th-century writers, only seven people were executed within the Tower before the World Wars of the 20th century. Executions were more commonly held on the notorious Tower Hill to the north of the castle, with 112 occurring there over a 400-year period. In the latter half of the 19th century, institutions such as the Royal Mint moved out of the castle to other locations, leaving many buildings empty. Anthony Salvin and John Taylor took the opportunity to restore the Tower to what was felt to be its medieval appearance, clearing out many of the vacant post-medieval structures.

In the First and Second World Wars, the Tower was again used as a prison and witnessed the executions of 12 men for espionage. After the Second World War, damage caused during the Blitz was repaired, and the castle reopened to the public. Today, the Tower of London is one of the country’s most popular tourist attractions. Under the ceremonial charge of the Constable of the Tower, and operated by the Resident Governor of the Tower of London and Keeper of the Jewel House, the property is cared for by the charity Historic Royal Palaces and is protected as a World Heritage Site.

Architecture[edit]

Layout[edit]

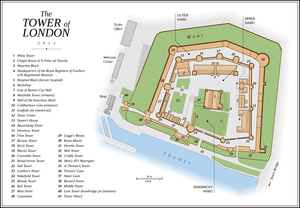

Plan of the Tower of London

The Tower was oriented with its strongest and most impressive defences overlooking Saxon London, which archaeologist Alan Vince suggests was deliberate.[4] It would have visually dominated the surrounding area and stood out to traffic on the River Thames.[5] The castle is made up of three «wards», or enclosures. The innermost ward contains the White Tower and is the earliest phase of the castle. Encircling it to the north, east, and west is the inner ward, built during the reign of Richard I (1189–1199). Finally, there is the outer ward which encompasses the castle and was built under Edward I. Although there were several phases of expansion after William the Conqueror founded the Tower of London, the general layout has remained the same since Edward I completed his rebuild in 1285.

The castle encloses an area of almost 12 acres (4.9 hectares) with a further 6 acres (2.4 ha) around the Tower of London constituting the Tower Liberties – land under the direct influence of the castle and cleared for military reasons.[6] The precursor of the Liberties was laid out in the 13th century when Henry III ordered that a strip of land adjacent to the castle be kept clear.[7] Despite popular fiction, the Tower of London never had a permanent torture chamber, although the basement of the White Tower housed a rack in later periods.[8] Tower Wharf was built on the bank of the Thames under Edward I and was expanded to its current size during the reign of Richard II (1377–1399).[9]

White Tower[edit]

The White Tower is a keep (also known as a donjon), which was often the strongest structure in a medieval castle, and contained lodgings suitable for the lord – in this case, the king or his representative.[10] According to military historian Allen Brown, «The great tower [White Tower] was also, by virtue of its strength, majesty and lordly accommodation, the donjon par excellence«.[11] As one of the largest keeps in the Christian world,[12] the White Tower has been described as «the most complete eleventh-century palace in Europe».[13]

The original entrance to the White Tower was at first-floor level

The White Tower, not including its projecting corner towers, measures 36 by 32 metres (118 by 105 ft) at the base, and is 27 m (90 ft) high at the southern battlements. The structure was originally three storeys high, comprising a basement floor, an entrance level, and an upper floor. The entrance, as is usual in Norman keeps, was above ground, in this case on the south face, and accessed via a wooden staircase which could be removed in the event of an attack. It was probably during Henry II’s reign (1154–1189) that a forebuilding was added to the south side of the tower to provide extra defences to the entrance, but it has not survived. Each floor was divided into three chambers, the largest in the west, a smaller room in the north-east, and the chapel taking up the entrance and upper floors of the south-east.[14] At the western corners of the building are square towers, while to the north-east a round tower houses a spiral staircase. At the south-east corner there is a larger semi-circular projection which accommodates the apse of the chapel. As the building was intended to be a comfortable residence as well as a stronghold, latrines were built into the walls, and four fireplaces provided warmth.[13]

The main building material is Kentish rag-stone, although some local mudstone was also used. Caen stone was imported from northern France to provide details in the Tower’s facing, although little of the original material survives as it was replaced with Portland stone in the 17th and 18th centuries.[15] Reigate stone was also used as ashlar and for carved details. Its location, in the lower courses of the building and at higher levels corresponding to a building break, suggest it was readily available and may have been used when access to Caen stone was restricted.[16] As most of the Tower’s windows were enlarged in the 18th century, only two original – albeit restored – examples remain, in the south wall at the gallery level.[15]

The tower was terraced into the side of a mound, so the northern side of the basement is partially below ground level.[17] As was typical of most keeps,[18] the bottom floor was an undercroft used for storage. One of the rooms contained a well. Although the layout has remained the same since the tower’s construction, the interior of the basement dates mostly from the 18th century when the floor was lowered and the pre-existing timber vaults were replaced with brick counterparts.[17] The basement is lit through small slits.[13]

St John’s Chapel, inside the White Tower

The entrance floor was probably intended for the use of the Constable of the Tower, Lieutenant of the Tower of London and other important officials. The south entrance was blocked during the 17th century, and not reopened until 1973. Those heading to the upper floor had to pass through a smaller chamber to the east, also connected to the entrance floor. The crypt of St John’s Chapel occupied the south-east corner and was accessible only from the eastern chamber. There is a recess in the north wall of the crypt; according to Geoffrey Parnell, Keeper of the Tower History at the Royal Armouries, «the windowless form and restricted access, suggest that it was designed as a strong-room for safekeeping of royal treasures and important documents».[17]

The upper floor contained a grand hall in the west and residential chamber in the east – both originally open to the roof and surrounded by a gallery built into the wall – and St John’s Chapel in the south-east. The top floor was added in the 15th century, along with the present roof.[14][19] St John’s Chapel was not part of the White Tower’s original design, as the apsidal projection was built after the basement walls.[17] Due to changes in function and design since the tower’s construction, except for the chapel little is left of the original interior.[20] The chapel’s current bare and unadorned appearance is reminiscent of how it would have been in the Norman period. In the 13th century, during Henry III’s reign, the chapel was decorated with such ornamentation as a gold-painted cross, and stained glass windows that depicted the Virgin Mary and the Holy Trinity.[21]

Innermost ward[edit]

The innermost ward encloses an area immediately south of the White Tower, stretching to what was once the edge of the River Thames. As was the case at other castles, such as the 11th-century Hen Domen, the innermost ward was probably filled with timber buildings from the Tower’s foundation. Exactly when the royal lodgings began to encroach from the White Tower into the innermost ward is uncertain, although it had happened by the 1170s.[15] The lodgings were renovated and elaborated during the 1220s and 1230s, becoming comparable with other palatial residences such as Windsor Castle.[22] Construction of Wakefield and Lanthorn Towers – located at the corners of the innermost ward’s wall along the river – began around 1220.[23][nb 1] They probably served as private residences for the queen and king respectively.

The earliest evidence for how the royal chambers were decorated comes from Henry III’s reign: the queen’s chamber was whitewashed, and painted with flowers and imitation stonework. A great hall existed in the south of the ward, between the two towers.[24] It was similar to, although slightly smaller than, that also built by Henry III at Winchester Castle.[25] Near Wakefield Tower was a postern gate which allowed private access to the king’s apartments. The innermost ward was originally surrounded by a protective ditch, which had been filled in by the 1220s. Around this time, a kitchen was built in the ward.[26] Between 1666 and 1676, the innermost ward was transformed and the palace buildings removed.[27] The area around the White Tower was cleared so that anyone approaching would have to cross open ground. The Jewel House was demolished, and the Crown Jewels moved to Martin Tower.[28]

Interior of the innermost ward. Right of centre is the 11th-century White Tower; the structure at the end of the walkway to the left is Wakefield Tower. Beyond that can be seen Traitors’ Gate.

Inner ward[edit]

The inner ward was created during Richard the Lionheart’s reign, when a moat was dug to the west of the innermost ward, effectively doubling the castle’s size.[29][30] Henry III created the ward’s east and north walls, and the ward’s dimensions remain to this day.[7] Most of Henry’s work survives, and only two of the nine towers he constructed have been completely rebuilt.[31] Between the Wakefield and Lanthorn Towers, the innermost ward’s wall also serves as a curtain wall for the inner ward.[32] The main entrance to the inner ward would have been through a gatehouse, most likely in the west wall on the site of what is now Beauchamp Tower. The inner ward’s western curtain wall was rebuilt by Edward I.[33] The 13th-century Beauchamp Tower marks the first large-scale use of brick as a building material in Britain, since the 5th-century departure of the Romans.[34] The Beauchamp Tower is one of 13 towers that stud the curtain wall. Clockwise from the south-west corner they are: Bell, Beauchamp, Devereux, Flint, Bowyer, Brick, Martin, Constable, Broad Arrow, Salt, Lanthorn, Wakefield, and the Bloody Tower.[32] While these towers provided positions from which flanking fire could be deployed against a potential enemy, they also contained accommodation. As its name suggests, Bell Tower housed a belfry, its purpose to raise the alarm in the event of an attack. The royal bow-maker, responsible for making longbows, crossbows, catapults, and other siege and hand weapons, had a workshop in the Bowyer Tower. A turret at the top of Lanthorn Tower was used as a beacon by traffic approaching the Tower at night.[35]

The south face of the Waterloo Block

As a result of Henry’s expansion, St Peter ad Vincula, a Norman chapel which had previously stood outside the Tower, was incorporated into the castle. Henry decorated the chapel by adding glazed windows, and stalls for himself and his queen.[31] It was rebuilt by Edward I at a cost of over £300[36] and again by Henry VIII in 1519; the current building dates from this period, although the chapel was refurbished in the 19th century.[37] Immediately west of Wakefield Tower, the Bloody Tower was built at the same time as the inner ward’s curtain wall, and as a water-gate provided access to the castle from the River Thames. It was a simple structure, protected by a portcullis and gate.[38] The Bloody Tower acquired its name in the 16th century, as it was believed to be the site of the murder of the Princes in the Tower.[39] Between 1339 and 1341, a gatehouse was built into the curtain wall between Bell and Salt Towers.[40] During the Tudor period, a range of buildings for the storage of munitions was built along the inside of the north inner ward.[41] The castle buildings were remodelled during the Stuart period, mostly under the auspices of the Office of Ordnance. In 1663, just over £4,000 was spent building a new storehouse (now known as the New Armouries) in the inner ward.[42] Construction of the Grand Storehouse north of the White Tower began in 1688, on the same site as the dilapidated Tudor range of storehouses;[43] it was destroyed by fire in 1841. The Waterloo Block, a former barracks in the castellated Gothic Revival style with Domestic Tudor details,[44] was built on the site and remains to this day, housing the Crown Jewels on the ground floor.[45]

Outer ward[edit]

A third ward was created during Edward I’s extension to the Tower, as the narrow enclosure completely surrounded the castle. At the same time a bastion known as Legge’s Mount was built at the castle’s northwest corner. Brass Mount, the bastion in the northeast corner, was a later addition. The three rectangular towers along the east wall 15 metres (49 ft) apart were dismantled in 1843. Although the bastions have often been ascribed to the Tudor period, there is no evidence to support this; archaeological investigations suggest that Legge’s Mount dates from the reign of Edward I.[46] Blocked battlements (also known as crenellations) in the south side of Legge’s Mount are the only surviving medieval battlements at the Tower of London (the rest are Victorian replacements).[47] A new 50-metre (160 ft) moat was dug beyond the castle’s new limits;[48] it was originally 4.5 metres (15 ft) deeper in the middle than it is today.[46] With the addition of a new curtain wall, the old main entrance to the Tower of London was obscured and made redundant; a new entrance was created in the southwest corner of the external wall circuit. The complex consisted of an inner and an outer gatehouse and a barbican,[49] which became known as the Lion Tower as it was associated with the animals as part of the Royal Menagerie since at least the 1330s.[50] The Lion Tower itself no longer survives.[49]

Edward extended the south side of the Tower of London onto land that had previously been submerged by the River Thames. In this wall, he built St Thomas’s Tower between 1275 and 1279; later known as Traitors’ Gate, it replaced the Bloody Tower as the castle’s water-gate. The building is unique in England, and the closest parallel is the now demolished water-gate at the Louvre in Paris. The dock was covered with arrowslits in case of an attack on the castle from the River; there was also a portcullis at the entrance to control who entered. There were luxurious lodgings on the first floor.[51] Edward also moved the Royal Mint into the Tower; its exact location early on is unknown, although it was probably in either the outer ward or the Lion Tower.[52] By 1560, the Mint was located in a building in the outer ward near Salt Tower.[53] Between 1348 and 1355, a second water-gate, Cradle Tower, was added east of St Thomas’s Tower for the king’s private use.[40]

The Tower of London’s outer curtain wall, with the curtain wall of the inner ward just visible behind. In the centre is Legge’s Mount.

History[edit]

Foundation and early history[edit]

Victorious at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066, the invading Duke of Normandy, William the Conqueror, spent the rest of the year securing his holdings by fortifying key positions. He founded several castles along the way, but took a circuitous route toward London;[54][55] only when he reached Canterbury did he turn towards England’s largest city. As the fortified bridge into London was held by Saxon troops, he decided instead to ravage Southwark before continuing his journey around southern England.[56] A series of Norman victories along the route cut the city’s supply lines and in December 1066, isolated and intimidated, its leaders yielded London without a fight.[57][58] Between 1066 and 1087, William established 36 castles,[55] although references in the Domesday Book indicate that many more were founded by his subordinates.[59] The Normans undertook what has been described as «the most extensive and concentrated programme of castle-building in the whole history of feudal Europe».[60] They were multi-purpose buildings, serving as fortifications (used as a base of operations in enemy territory), centres of administration, and residences.[61]

William sent an advance party to prepare the city for his entrance, to celebrate his victory and found a castle; in the words of William’s biographer, William of Poitiers, «certain fortifications were completed in the city against the restlessness of the huge and brutal populace. For he [William] realised that it was of the first importance to overawe the Londoners».[54] At the time, London was the largest town in England; the foundation of Westminster Abbey and the old Palace of Westminster under Edward the Confessor had marked it as a centre of governance, and with a prosperous port it was important for the Normans to establish control over the settlement.[58] The other two castles in London – Baynard’s Castle and Montfichet’s Castle – were established at the same time.[62] The fortification that would later become known as the Tower of London was built onto the south-east corner of the Roman town walls, using them as prefabricated defences, with the River Thames providing additional protection from the south.[54] This earliest phase of the castle would have been enclosed by a ditch and defended by a timber palisade, and probably had accommodation suitable for William.[63]

The White Tower dates from the late 11th century.

Most of the early Norman castles were built from timber, but by the end of the 11th century a few, including the Tower of London, had been renovated or replaced with stone.[62] Work on the White Tower – which gives the whole castle its name –[12] is usually considered to have begun in 1078, however the exact date is uncertain. William made Gundulf, Bishop of Rochester, responsible for its construction, although it may not have been completed until after William’s death in 1087.[12] The White Tower is the earliest stone keep in England, and was the strongest point of the early castle. It also contained grand accommodation for the king.[64] At the latest, it was probably finished by 1100 when Bishop Ranulf Flambard was imprisoned there.[20][nb 2] Flambard was loathed by the English for exacting harsh taxes. Although he is the first recorded prisoner held in the Tower, he was also the first person to escape from it, using a smuggled rope secreted in a butt of wine. He was held in luxury and permitted servants, but on 2 February 1101 he hosted a banquet for his captors. After plying them with drink, when no one was looking he lowered himself from a secluded chamber, and out of the Tower. The escape came as such a surprise that one contemporary chronicler accused the bishop of witchcraft.[66]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that in 1097 King William II ordered a wall to be built around the Tower of London; it was probably built from stone and likely replaced the timber palisade that arced around the north and west sides of the castle, between the Roman wall (to the east) and the Thames (to the south).[67] The Norman Conquest of London manifested itself not only with a new ruling class, but in the way the city was structured. Land was confiscated and redistributed amongst the Normans, who also brought over hundreds of Jews, for financial reasons.[68] The Jews arrived under the direct protection of the Crown, as a result of which Jewish communities were often found close to castles.[69] The Jews used the Tower as a retreat, when threatened by anti-Jewish violence.[68]

The death in 1135 of Henry I left England with a disputed succession; although the king had persuaded his most powerful barons to swear support for the Empress Matilda, just a few days after Henry’s death Stephen of Blois arrived from France to lay claim to the throne. The importance of the city and its Tower is marked by the speed at which he secured London. The castle, which had not been used as a royal residence for some time, was usually left in the charge of a Constable, a post held at this time by Geoffrey de Mandeville. As the Tower was considered an impregnable fortress in a strategically important position, possession was highly valued. Mandeville exploited this, selling his allegiance to Matilda after Stephen was captured in 1141 at the Battle of Lincoln. Once her support waned, the following year he resold his loyalty to Stephen. Through his role as Constable of the Tower, Mandeville became «the richest and most powerful man in England».[70] When he tried the same ploy again, this time holding secret talks with Matilda, Stephen had him arrested, forced him to cede control of his castles, and replaced him with one of his most loyal supporters. Until then the position had been hereditary, originally held by Geoffrey de Mandeville, but the position’s authority was such that from then on it remained in the hands of an appointee of the monarch. The position was usually given to someone of great importance, who might not always be at the castle due to other duties. Although the Constable was still responsible for maintaining the castle and its garrison, from an early stage he had a subordinate to help with this duty: the Lieutenant of the Tower.[70] Constables also had civic duties relating to the city. Usually they were given control of the city and were responsible for levying taxes, enforcing the law and maintaining order. The creation in 1191 of the position of Lord Mayor of London removed many of the Constable’s civic powers, and at times led to friction between the two.[71]

Expansion[edit]

The castle probably retained its form as established by 1100 until the reign of Richard I (1189–1199).[72] The castle was extended under William Longchamp, King Richard’s Lord Chancellor and the man in charge of England while he was on crusade. The Pipe Rolls record £2,881 1s 10d spent at the Tower of London between 3 December 1189 and 11 November 1190,[73] from an estimated £7,000 spent by Richard on castle building in England.[74] According to the contemporary chronicler Roger of Howden, Longchamp dug a moat around the castle and tried in vain to fill it from the Thames.[29] Longchamp was also Constable of the Tower, and undertook its expansion while preparing for war with King Richard’s younger brother, Prince John, who in Richard’s absence arrived in England to try to seize power. As Longchamp’s main fortress, he made the Tower as strong as possible. The new fortifications were first tested in October 1191, when the Tower was besieged for the first time in its history. Longchamp capitulated to John after just three days, deciding he had more to gain from surrender than prolonging the siege.[75]

John succeeded Richard as king in 1199, but his rule proved unpopular with many of his barons, who in response moved against him. In 1214, while the king was at Windsor Castle, Robert Fitzwalter led an army into London and laid siege to the Tower. Although under-garrisoned, the Tower resisted and the siege was lifted once John signed the Magna Carta.[76] The king reneged on his promises of reform, leading to the outbreak of the First Barons’ War. Even after the Magna Carta was signed, Fitzwalter maintained his control of London. During the war, the Tower’s garrison joined forces with the barons. John was deposed in 1216 and the barons offered the English throne to Prince Louis, the eldest son of the French king. However, after John’s death in October 1216, many began to support the claim of his eldest son, Henry III. War continued between the factions supporting Louis and Henry, with Fitzwalter supporting Louis. Fitzwalter was still in control of London and the Tower, both of which held out until it was clear that Henry III’s supporters would prevail.[76]

In the 13th century, Kings Henry III (1216–1272) and Edward I (1272–1307) extended the castle, essentially creating it as it stands today.[23] Henry was disconnected from his barons, and a mutual lack of understanding led to unrest and resentment towards his rule. As a result, he was eager to ensure the Tower of London was a formidable fortification; at the same time Henry was an aesthete and wished to make the castle a comfortable place to live.[77] From 1216 to 1227 nearly £10,000 was spent on the Tower of London; in this period, only the work at Windsor Castle cost more (£15,000). Most of the work was focused on the palatial buildings of the innermost ward.[22] The tradition of whitewashing the White Tower (from which it derives its name) began in 1240.[78]

Beginning around 1238, the castle was expanded to the east, north, and north-west. The work lasted through the reign of Henry III and into that of Edward I, interrupted occasionally by civil unrest. New creations included a new defensive perimeter, studded with towers, while on the west, north, and east sides, where the wall was not defended by the river, a defensive ditch was dug. The eastern extension took the castle beyond the bounds of the old Roman settlement, marked by the city wall which had been incorporated into the castle’s defences.[78] The Tower had long been a symbol of oppression, despised by Londoners, and Henry’s building programme was unpopular. So when the gatehouse collapsed in 1240, the locals celebrated the setback.[79] The expansion caused disruption locally and £166 was paid to St Katherine’s Hospital and the prior of Holy Trinity in compensation.[80]

Henry III often held court at the Tower of London, and held parliament there on at least two occasions (1236 and 1261) when he felt that the barons were becoming dangerously unruly. In 1258, the discontented barons, led by Simon de Montfort, forced the King to agree to reforms including the holding of regular parliaments. Relinquishing the Tower of London was among the conditions. Henry III resented losing power and sought permission from the pope to break his oath. With the backing of mercenaries, Henry installed himself in the Tower in 1261. While negotiations continued with the barons, the King ensconced himself in the castle, although no army moved to take it. A truce was agreed with the condition that the King hand over control of the Tower once again. Henry won a significant victory at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, allowing him to regain control of the country and the Tower of London. Cardinal Ottobuon came to England to excommunicate those who were still rebellious; the act was deeply unpopular and the situation was exacerbated when the cardinal was granted custody of the Tower. Gilbert de Clare, 6th Earl of Hertford, marched on London in April 1267 and laid siege to the castle, declaring that custody of the Tower was «not a post to be trusted in the hands of a foreigner, much less of an ecclesiastic».[81] Despite a large army and siege engines, Gilbert de Clare was unable to take the castle. The Earl retreated, allowing the King control of the capital, and the Tower experienced peace for the rest of Henry’s reign.[82]

Although he was rarely in London, Edward I undertook an expensive remodelling of the Tower, costing £21,000 between 1275 and 1285, over double that spent on the castle during the whole of Henry III’s reign.[83] Edward I was a seasoned castle builder, and used his experience of siege warfare during the crusades to bring innovations to castle building.[83] His programme of castle building in Wales heralded the introduction of the widespread use of arrowslits in castle walls across Europe, drawing on Eastern influences.[84] At the Tower of London, Edward filled in the moat dug by Henry III and built a new curtain wall along its line, creating a new enclosure. A new moat was created in front of the new curtain wall. The western part of Henry III’s curtain wall was rebuilt, with Beauchamp Tower replacing the castle’s old gatehouse. A new entrance was created, with elaborate defences including two gatehouses and a barbican.[85] In an effort to make the castle self-sufficient, Edward I also added two watermills.[86] Six hundred Jews were imprisoned in the Tower of London in 1278, charged with coin clipping.[68] Persecution of the country’s Jewish population under Edward began in 1276 and culminated in 1290 when he issued the Edict of Expulsion, forcing the Jews out of the country.[87] In 1279, the country’s numerous mints were unified under a single system whereby control was centralised to the mint within the Tower of London, while mints outside of London were reduced, with only a few local and episcopal mints continuing to operate.[88]

Later Medieval Period[edit]

A model of the Tower of London as it appeared after the extension of the wharf in the late medieval period and the addition of the brick Bulwark at the west end of the castle under Edward IV.[89]

During Edward II’s reign (1307–1327) there was relatively little activity at the Tower of London.[90] However, it was during this period that the Privy Wardrobe was founded. The institution was based at the Tower and responsible for organising the state’s arms.[91] In 1321, Margaret de Clare, Baroness Badlesmere became the first woman imprisoned in the Tower of London after she refused Queen Isabella admittance to Leeds Castle[92] and ordered her archers to target Isabella, killing six of the royal escort.[93][94][95] Generally reserved for high-ranking inmates, the Tower was the most important royal prison in the country.[96] However it was not necessarily very secure, and throughout its history people bribed the guards to help them escape. In 1323, Roger Mortimer, Baron Mortimer, was aided in his escape from the Tower by the Sub-Lieutenant of the Tower who let Mortimer’s men inside. They hacked a hole in his cell wall and Mortimer escaped to a waiting boat. He fled to France where he encountered Edward’s Queen. They began an affair and plotted to overthrow the King.

One of Mortimer’s first acts on entering England in 1326 was to capture the Tower and release the prisoners held there. For four years he ruled while Edward III was too young to do so himself; in 1330, Edward and his supporters captured Mortimer and threw him into the Tower.[97] Under Edward III’s rule (1312–1377) England experienced renewed success in warfare after his father’s reign had put the realm on the backfoot against the Scots and French. Amongst Edward’s successes were the battles of Crécy and Poitiers where King John II of France was taken prisoner, and the capture of the King David II of Scotland at Neville’s Cross. During this period, the Tower of London held many noble prisoners of war.[98] Edward II had allowed the Tower of London to fall into a state of disrepair,[40] and by the reign of Edward III the castle was an uncomfortable place. The nobility held captive within its walls were unable to engage in activities such as hunting which were permissible at other royal castles used as prisons, for instance Windsor. Edward III ordered that the castle should be renovated.[99]

One of the powerful French magnates held in the Tower during the Hundred Years’ War was Charles, Duke of Orléans, the nephew of the King of France. This late 15th-century image is the earliest surviving non-schematic picture of the Tower of London. It shows the White Tower and the water-gate, with Old London Bridge in the background.[100]

When Richard II was crowned in 1377, he led a procession from the Tower to Westminster Abbey. This tradition began in at least the early 14th century and lasted until 1660.[98] During the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 the Tower of London was besieged with the King inside. When Richard rode out to meet with Wat Tyler, the rebel leader, a crowd broke into the castle without meeting resistance and looted the Jewel House. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Simon Sudbury, took refuge in St John’s Chapel, hoping the mob would respect the sanctuary. However, he was taken away and beheaded on Tower Hill.[101] Six years later there was again civil unrest, and Richard spent Christmas in the security of the Tower rather than Windsor as was more usual.[102] When Henry Bolingbroke returned from exile in 1399, Richard was imprisoned in the White Tower. He abdicated and was replaced on the throne by Bolingbroke, who became King Henry IV.[101] In the 15th century, there was little building work at the Tower of London, yet the castle still remained important as a place of refuge. When supporters of the late Richard II attempted a coup, Henry IV found safety in the Tower of London. During this period, the castle also held many distinguished prisoners. The heir to the Scottish throne, later King James I of Scotland, was kidnapped while journeying to France in 1406 and held in the Tower. The reign of Henry V (1413–1422) renewed England’s fortune in the Hundred Years’ War against France. As a result of Henry’s victories, such as the Battle of Agincourt, many high-status prisoners were held in the Tower of London until they were ransomed.[103]

Much of the latter half of the 15th century was occupied by the Wars of the Roses between the claimants to the throne, the houses of Lancaster and York.[104] The castle was once again besieged in 1460, this time by a Yorkist force. The Tower was damaged by artillery fire but only surrendered when Henry VI was captured at the Battle of Northampton. With the help of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick (nicknamed «the Kingmaker») Henry recaptured the throne for a short time in 1470. However, Edward IV soon regained control and Henry VI was imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he was probably murdered.[101] In 1471, during the Siege of London, the Tower’s Yorkist garrison exchanged fire with Lancastrians holding Southwark, and sallied from the fortress to take part in a pincer movement to attack Lancastrians who were assaulting Aldgate on London’s defensive wall. During the wars, the Tower was fortified to withstand gunfire, and provided with loopholes for cannons and handguns: an enclosure called the Bulwark was created for this purpose to the south of Tower Hill, although it no longer survives.[104]

Prince Edward V and Richard in the Tower, 1483 by Sir John Everett Millais, 1878. They are known as the Princes in the Tower as they were lodged in the Tower of London, with their last recorded appearance being in June 1483.

Shortly after the death of Edward IV in 1483, the notorious murder of the Princes in the Tower is traditionally believed to have taken place. The incident is one of the most infamous events associated with the Tower of London.[105] Edward V’s uncle Richard, Duke of Gloucester was declared Lord Protector while the prince was too young to rule.[106] Traditional accounts have held that the 12-year-old Edward was confined to the Tower of London along with his younger brother Richard. The Duke of Gloucester was proclaimed King Richard III in June. The princes were last seen in public in June 1483;[105] it has traditionally been thought that the most likely reason for their disappearance is that they were murdered late in the summer of 1483.[106] Bones thought to belong to them were discovered in 1674 when the 12th-century forebuilding at the entrance to the White Tower was demolished; however, the reputed level at which the bones were found (10 ft or 3 m) would put the bones at a depth similar to that of the Roman graveyard found, in 2011, 12 ft (4 m) underneath the Minories a few hundred yards to the north.[107] Opposition to Richard escalated until he was defeated at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485 by the Lancastrian Henry Tudor, who ascended to the throne as Henry VII.[105] As king, Henry VII built a tower for a library next to the King’s Tower.[108]

Changing use[edit]

The beginning of the Tudor period marked the start of the decline of the Tower of London’s use as a royal residence. As 16th-century chronicler Raphael Holinshed said the Tower became used more as «an armouries and house of munition, and thereunto a place for the safekeeping of offenders than a palace roiall for a king or queen to sojourne in».[100] Henry VII visited the Tower on fourteen occasions between 1485 and 1500, usually staying for less than a week at a time.[109] The Yeoman Warders have been the Royal Bodyguard since at least 1509.[110] In 1517 the Tower fired its cannon at City crowds engaged in the xenophobic Evil May Day riots, in which the properties of foreign residents were ransacked. It is not thought that any rioters were hurt by the gunfire, which was probably meant to merely intimidate the mob.[111]

During the reign of Henry VIII, the Tower was assessed as needing considerable work on its defences. In 1532, Thomas Cromwell spent £3,593 on repairs and imported nearly 3,000 tons of Caen stone for the work.[37] Even so, this was not sufficient to bring the castle up to the standard of contemporary military fortifications which were designed to withstand powerful artillery.[112] Although the defences were repaired, the palace buildings were left in a state of neglect after Henry’s death. Their condition was so poor that they were virtually uninhabitable.[100] From 1547 onwards, the Tower of London was only used as a royal residence when its political and historic symbolism was considered useful, for instance each of Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I briefly stayed at the Tower before their coronations.[113]

In the 16th century, the Tower acquired an enduring reputation as a grim, forbidding prison. This had not always been the case. As a royal castle, it was used by the monarch to imprison people for various reasons, however these were usually high-status individuals for short periods rather than common citizenry as there were plenty of prisons elsewhere for such people. Contrary to the popular image of the Tower, prisoners were able to make their life easier by purchasing amenities such as better food or tapestries through the Lieutenant of the Tower.[114] As holding prisoners was originally an incidental role of the Tower – as would have been the case for any castle – there was no purpose-built accommodation for prisoners until 1687 when a brick shed, a «Prison for Soldiers», was built to the north-west of the White Tower. The Tower’s reputation for torture and imprisonment derives largely from 16th-century religious propagandists and 19th-century romanticists.[115] Although much of the Tower’s reputation is exaggerated, the 16th and 17th centuries marked the castle’s zenith as a prison, with many religious and political undesirables locked away.[115] The Privy Council had to sanction the use of torture, so it was not often used; between 1540 and 1640, the peak of imprisonment at the Tower, there were 48 recorded cases of the use of torture. The three most common forms used were the infamous rack, the Scavenger’s daughter, and manacles.[116] The rack was introduced to England in 1447 by the Duke of Exeter, the Constable of the Tower; consequentially it was also known as the Duke of Exeter’s daughter.[117] One of those tortured at the Tower was Guy Fawkes, who was brought there on 6 November 1605; after torture he signed a full confession to the Gunpowder Plot.[115]

Among those held and executed at the Tower was Anne Boleyn.[115] Although the Yeoman Warders were once the Royal Bodyguard, by the 16th and 17th centuries their main duty had become to look after the prisoners.[118] The Tower was often a safer place than other prisons in London such as the Fleet, where disease was rife. High-status prisoners could live in conditions comparable to those they might expect outside; one such example was that while Walter Raleigh was held in the Tower his rooms were altered to accommodate his family, including his son who was born there in 1605.[116] Executions were usually carried out on Tower Hill rather than in the Tower of London itself, and 112 people were executed on the hill over 400 years.[119] Before the 20th century, there had been seven executions within the castle on Tower Green; as was the case with Lady Jane Grey, this was reserved for prisoners for whom public execution was considered dangerous.[119] After Lady Jane Grey’s execution on 12 February 1554,[120] Queen Mary I imprisoned her sister Elizabeth, later Queen Elizabeth I, in the Tower under suspicion of causing rebellion as Sir Thomas Wyatt had led a revolt against Mary in Elizabeth’s name.[121]

Memorial To The Executed in the Tower, unveiled in 2006, designed by Brian Catling

The cobbled surface of Tower Hill to the north of the Tower of London. Over a period of 400 years, 112 people were executed on the hill.[119]

The Office of Ordnance and Armoury Office were founded in the 15th century, taking over the Privy Wardrobe’s duties of looking after the monarch’s arsenal and valuables.[122] As there was no standing army before 1661, the importance of the royal armoury at the Tower of London was that it provided a professional basis for procuring supplies and equipment in times of war. The two bodies were resident at the Tower from at least 1454, and by the 16th century they had moved to a position in the inner ward.[123] The Board of Ordnance (successor to these Offices) had its headquarters in the White Tower and used surrounding buildings for storage. In 1855 the Board was abolished; its successor (the Military Store Department of the War Office) was also based there until 1869, after which its headquarters staff were relocated to the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich (where the recently closed Woolwich Dockyard was converted into a vast ordnance store).[124]

Political tensions between Charles I and Parliament in the second quarter of the 17th century led to an attempt by forces loyal to the King to secure the Tower and its valuable contents, including money and munitions. London’s Trained Bands, a militia force, were moved into the castle in 1640. Plans for defence were drawn up and gun platforms were built, readying the Tower for war. The preparations were never put to the test. In 1642, Charles I attempted to arrest five members of parliament. When this failed he fled the city, and Parliament retaliated by removing Sir John Byron, the Lieutenant of the Tower. The Trained Bands had switched sides, and now supported Parliament; together with the London citizenry, they blockaded the Tower. With permission from the King, Byron relinquished control of the Tower. Parliament replaced Byron with a man of their own choosing, Sir John Conyers. By the time the English Civil War broke out in November 1642, the Tower of London was already in Parliament’s control.[125]

The last monarch to uphold the tradition of taking a procession from the Tower to Westminster to be crowned was Charles II in 1661. At the time, the castle’s accommodation was in such poor condition that he did not stay there the night before his coronation.[126] Under the Stuart kings the Tower’s buildings were remodelled, mostly under the auspices of the Office of Ordnance. Just over £4,000 was spent in 1663 on building a new storehouse, now known as the New Armouries in the inner ward.[42] In the 17th century there were plans to enhance the Tower’s defences in the style of the trace italienne, however they were never acted on. Although the facilities for the garrison were improved with the addition of the first purpose-built quarters for soldiers (the «Irish Barracks») in 1670, the general accommodations were still in poor condition.[127]

When the Hanoverian dynasty ascended the throne, their situation was uncertain and with a possible Scottish rebellion in mind, the Tower of London was repaired. Most of the work in this period (1750 to 1770) was done by the King’s Master Mason, John Deval.[128] Gun platforms added under the Stuarts had decayed. The number of guns at the Tower was reduced from 118 to 45, and one contemporary commentator noted that the castle «would not hold out four and twenty hours against an army prepared for a siege».[129] For the most part, the 18th-century work on the defences was spasmodic and piecemeal, although a new gateway in the southern curtain wall permitting access from the wharf to the outer ward was added in 1774. The moat surrounding the castle had become silted over the centuries since it was created despite attempts at clearing it. It was still an integral part of the castle’s defences, so in 1830 the Constable of the Tower, the Duke of Wellington, ordered a large-scale clearance of several feet of silt. However this did not prevent an outbreak of disease in the garrison in 1841 caused by poor water supply, resulting in several deaths. To prevent the festering ditch posing further health problems, it was ordered that the moat should be drained and filled with earth. The work began in 1843 and was mostly complete two years later. The construction of the Waterloo Barracks in the inner ward began in 1845, when the Duke of Wellington laid the foundation stone. The building could accommodate 1,000 men; at the same time, separate quarters for the officers were built to the north-east of the White Tower. The building is now the headquarters of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers.[130] The popularity of the Chartist movement between 1828 and 1858 led to a desire to refortify the Tower of London in the event of civil unrest. It was the last major programme of fortification at the castle. Most of the surviving installations for the use of artillery and firearms date from this period.[131]

During the First World War, eleven men were tried in private and shot by firing squad at the Tower for espionage.[132] During the Second World War, the Tower was once again used to hold prisoners of war. One such person was Rudolf Hess, Adolf Hitler’s deputy, albeit just for four days in 1941. He was the last state prisoner to be held at the castle.[133] The last person to be executed at the Tower was German spy Josef Jakobs who was shot on 15 August 1941.[134] The executions for espionage during the wars took place in a prefabricated miniature rifle range which stood in the outer ward and was demolished in 1969.[135] The Second World War also saw the last use of the Tower as a fortification. In the event of a German invasion, the Tower, together with the Royal Mint and nearby warehouses, was to have formed one of three «keeps» or complexes of defended buildings which formed the last-ditch defences of the capital.[136]

Restoration and tourism[edit]

The Tower of London has become established as one of the most popular tourist attractions in the country. It has been a tourist attraction since at least the Elizabethan period, when it was one of the sights of London that foreign visitors wrote about. Its most popular attractions were the Royal Menagerie and displays of armour. The Crown Jewels also garner much interest, and have been on public display since 1669. The Tower steadily gained popularity with tourists through the 19th century, despite the opposition of the Duke of Wellington to visitors. Numbers became so high that by 1851 a purpose-built ticket office was erected. By the end of the century, over 500,000 were visiting the castle every year.[138]

Over the 18th and 19th centuries, the palatial buildings were slowly adapted for other uses and demolished. Only the Wakefield and St Thomas’s Towers survived.[126] The 18th century marked an increasing interest in England’s medieval past. One of the effects was the emergence of Gothic Revival architecture. In the Tower’s architecture, this was manifest when the New Horse Armoury was built in 1825 against the south face of the White Tower. It featured elements of Gothic Revival architecture such as battlements. Other buildings were remodelled to match the style and the Waterloo Barracks were described as «castellated Gothic of the 15th century».[139][140] Between 1845 and 1885 institutions such as the Mint which had inhabited the castle for centuries moved to other sites; many of the post-medieval structures left vacant were demolished. In 1855, the War Office took over responsibility for manufacture and storage of weapons from the Ordnance Office, which was gradually phased out of the castle. At the same time, there was greater interest in the history of the Tower of London.[139]

Public interest was partly fuelled by contemporary writers, of whom the work of William Harrison Ainsworth was particularly influential. In The Tower of London: A Historical Romance he created a vivid image of underground torture chambers and devices for extracting confessions that stuck in the public imagination.[115] Ainsworth also played another role in the Tower’s history, as he suggested that Beauchamp Tower should be opened to the public so they could see the inscriptions of 16th- and 17th-century prisoners. Working on the suggestion, Anthony Salvin refurbished the tower and led a further programme for a comprehensive restoration at the behest of Prince Albert. Salvin was succeeded in the work by John Taylor. When a feature did not meet his expectations of medieval architecture Taylor would ruthlessly remove it; as a result, several important buildings within the castle were pulled down and in some cases post-medieval internal decoration removed.[141]

The main entrance to the Tower of London. Today the castle is a popular tourist attraction.

Although only one bomb fell on the Tower of London in the First World War (it landed harmlessly in the moat), the Second World War left a greater mark. On 23 September 1940, during the Blitz, high-explosive bombs damaged the castle, destroying several buildings and narrowly missing the White Tower. After the war, the damage was repaired and the Tower of London was reopened to the public.[142]

A 1974 bombing in the White Tower Mortar Room left one person dead and 41 injured. No one claimed responsibility for the blast, but the police investigated suspicions that the IRA was behind it.[143]

In the 21st century, tourism is the Tower’s primary role, with the remaining routine military activities, under the Royal Logistic Corps, having wound down in the latter half of the 20th century and moved out of the castle.[142] However, the Tower is still home to the regimental headquarters of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers, and the museum dedicated to it and its predecessor, the Royal Fusiliers.[144][145] Also, a detachment of the unit providing the King’s Guard at Buckingham Palace still mounts a guard at the Tower, and with the Yeomen Warders, takes part in the Ceremony of the Keys each day.[146][147][148] On several occasions through the year gun salutes are fired from the Tower by the Honourable Artillery Company, these consist of 62 rounds for royal occasions, and 41 on other occasions.[149]

Since 1990, the Tower of London has been cared for by an independent charity, Historic Royal Palaces, which receives no funding from the Government or the Crown.[150] In 1988, the Tower of London was added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites, in recognition of its global importance and to help conserve and protect the site.[151][152] However, recent developments, such as the construction of skyscrapers nearby, have pushed the Tower towards being added to the United Nations’ Heritage in Danger List.[153] The remains of the medieval palace have been open to the public since 2006 where visitors can explore the restored chambers.[154] Although the position of Constable of the Tower remains the highest position held at the Tower,[155] the responsibility of day-to-day administration is delegated to the Resident Governor.[156] The Constable is appointed for a five-year term; this is primarily a ceremonial post today but the Constable is also a trustee of Historic Royal Palaces and of the Royal Armouries. General Sir Gordon Messenger was appointed Constable in 2022.[157]

At least six ravens are kept at the Tower at all times, in accordance with the belief that if they are absent, the kingdom will fall.[158] They are under the care of the Ravenmaster, one of the Yeoman Warders.[159] As well as having ceremonial duties, the Yeoman Warders provide guided tours around the Tower.[110][118]

Garrison[edit]

The Yeomen Warders provided the permanent garrison of the Tower, but the Constable of the Tower could call upon the men of the Tower Hamlets to supplement them when necessary. The Tower Hamlets, aka Tower Division of Middlesex’s Ossulstone Hundred was an area, significantly larger than the modern London Borough of the same name, which owed military service to the Constable in his ex officio role as Lord Lieutenant of the Tower Hamlets.[160]

The earliest surviving reference to the inhabitants of the Tower Hamlets having a duty to provide a guard for the Tower of London is from 1554, during the reign of Mary I, but the relationship is thought to go back much further. Some believe the connection goes back to the time of the Conqueror.[161] The duty is likely to have had its origin in the rights and obligations of the Manor of Stepney which covered most or all of the Hamlets area.[162][161]

Crown Jewels[edit]

The tradition of housing the Crown Jewels in the Tower of London probably dates from the reign of Henry III (1216–1272). The Jewel House was built specifically to house the royal regalia, including jewels, plate, and symbols of royalty such as the crown, sceptre, and sword. When money needed to be raised, the treasure could be pawned by the monarch. The treasure allowed the monarch independence from the aristocracy and consequently was closely guarded. A new position for «keeper of the jewels, armouries and other things» was created,[163] which was well rewarded; in the reign of Edward III (1327–1377) the holder was paid 12d a day. The position grew to include other duties including purchasing royal jewels, gold, and silver, and appointing royal goldsmiths and jewellers.[163]

In 1649, during the English Commonwealth following Charles I’s execution, the contents of the Jewel House were disposed of along with other royal properties, as decreed by Cromwell. Metal items were sent to the Mint to be melted down and re-used, and the crowns were «totallie broken and defaced».[164]

When the monarchy was restored in 1660, the only surviving items of the coronation regalia were a 12th-century spoon and three ceremonial swords. (Some pieces that had been sold were later returned to the Crown.)[165] Detailed records of old regalia survived, and replacements were made for the coronation of Charles II in 1661 based on drawings from the time of Charles I. For the coronation of Charles II, gems were rented because the treasury could not afford to replace them.[166]

In 1669, the Jewel House was demolished[28] and the Crown Jewels moved into Martin Tower (until 1841).[167] They were displayed here for viewing by the paying public. This was exploited two years later when Colonel Thomas Blood attempted to steal them.[138] Blood and his accomplices bound and gagged the Jewel House keeper. Although they laid their hands on the Imperial State Crown, Sceptre and Orb, they were foiled when the keeper’s son turned up unexpectedly and raised the alarm.[164][168]

Since 1994, the Crown Jewels have been on display in the Jewel House in the Waterloo Block. Some of the pieces were once regularly used by Queen Elizabeth II. The display includes 23,578 gemstones, the 800-year-old Coronation Spoon, St Edward’s Crown (traditionally placed on a monarch’s head at the moment of crowning) and the Imperial State Crown.[169][170][171]

Royal Menagerie[edit]

There is evidence that King John (1166–1216) first started keeping wild animals at the Tower.[172][173] Records of 1210–1212 show payments to lion keepers.[174]

The Royal Menagerie is frequently referenced during the reign of Henry III. Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II presented Henry with three leopards, circa 1235, which were kept in the Tower.[175] In 1252, the sheriffs were ordered to pay fourpence a day towards the upkeep of the King’s polar bear, a gift from Haakon IV of Norway in the same year; the bear attracted a great deal of attention from Londoners when it went fishing in the Thames while tied to the land by a chain.[68][176][177] In 1254 or 1255, Henry III received an African elephant from Louis IX of France depicted by Matthew Paris in his Chronica Majora. A wooden structure was built to house the elephant, 12.2 m (40 ft) long by 6.1 m (20 ft) wide.[174][68] The animal died in 1258, possibly because it was given red wine, but also perhaps because of the cold climate of England.[178]

In 1288, Edward I added a lion and a lynx and appointed the first official Keeper of the animals.[179]

Edward III added other types of animals, two lions, a leopard and two wildcats. Under subsequent kings, the number of animals grew to include additional cats of various types, jackals, hyenas, and an old brown bear, Max, gifted to Henry VIII by Emperor Maximilian.[180] In 1436, during the time of Henry VI, all the lions died and the employment of Keeper William Kerby was terminated.[179]

Historical records indicate that a semi-circular structure or barbican was built by Edward I in 1277; this area was later named the Lion Tower, to the immediate west of the Middle Tower. Records from 1335 indicate the purchase of a lock and key for the lions and leopards, also suggesting they were located near the western entrance of the Tower. By the 1500s that area was called the Menagerie.[174] Between 1604 and 1606 the Menagerie was extensively refurbished and an exercise yard was created in the moat area beside the Lion Tower. An overhead platform was added for viewing of the lions by the royals, during lion baiting, for example in the time of James I. Reports from 1657 include mention of six lions, increasing to 11 by 1708, in addition to other types of cats, eagles, owls and a jackal.[174]

By the 18th century, the menagerie was open to the public; admission cost three half-pence or a cat or dog to be fed to the lions. By the end of the century, that had increased to 9 pence.[174][181] A particularly famous inhabitant was Old Martin, a large grizzly bear given to George III by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1811.[182][183] An 1800 inventory also listed a tiger, leopards, a hyena, a large baboon, various types of monkeys, wolves, and «other animals».[184] By 1822, however, the collection included only a grizzly bear, an elephant, and some birds. Additional animals were then introduced.[185] In 1828, there were over 280 representing at least 60 species as the new keeper Alfred Copps was actively acquiring animals.[186]

After the death of George IV in 1830, a decision was made to close down the Menagerie on the orders of the Duke of Wellington.[187] In 1831, most of the stock was moved to the London Zoo which had opened in 1828.[188] This decision was made after an incident, although sources vary as to the specifics: either a lion was accused of biting a soldier,[189][190] or a sailor, Ensign Seymour, had been bitten by a monkey.[174][191] The last of the animals left in 1835, relocated to Regent’s Park. The Menagerie buildings were removed in 1852 but the Keeper of the Royal Menagerie was entitled to use the Lion Tower as a house for life. Consequently, even though the animals had long since left the building, the tower was not demolished until the death of Copps, the last keeper, in 1853.[189]

In 1999, physical evidence of lion cages was found, one being 2×3 metres (6.5×10 feet) in size, very small for a lion that can grow to be 2.5 meters (approximately 8 feet) long.[175] In 2008, the skulls of two male Barbary lions (now extinct in the wild) from northwest Africa were found in the moat area of the Tower. Radiocarbon tests dated them from 1280 to 1385 and 1420–1480.[173] In 2011, an exhibition was hosted at the Tower with fine wire sculptures by Kendra Haste.[192]

In folklore[edit]

The Tower of London has been represented in popular culture in many ways. As a result of 16th and 19th century writers, the Tower has a reputation as a grim fortress, a place of torture and execution.[193]

One of the earliest traditions associated with the Tower was that it was built by Julius Caesar; the story was popular amongst writers and antiquaries. The earliest recorded attribution of the Tower to the Roman ruler dates to the mid-14th century in a poem by Sir Thomas Gray.[194] The origin of the myth is uncertain, although it may be related to the fact that the Tower was built in the corner of London’s Roman walls. Another possibility is that someone misread a passage from Gervase of Tilbury in which he says Caesar built a tower at Odnea in France. Gervase wrote Odnea as Dodres, which is close to the French for London, Londres.[195] Today, the story survives in William Shakespeare’s Richard II and Richard III,[196] and as late as the 18th century some still regarded the Tower as built by Caesar.[197]

Anne Boleyn was beheaded in 1536 for treason against Henry VIII; her ghost supposedly haunts the Church of St Peter ad Vincula in the Tower, where she is buried, and has been said to walk around the White Tower carrying her head under her arm.[198] This haunting is commemorated in the 1934 comic song «With Her Head Tucked Underneath Her Arm». Other reported ghosts include Henry VI, Lady Jane Grey, Margaret Pole, and the Princes in the Tower.[199] In January 1816, a sentry on guard outside the Jewel House claimed to have witnessed an apparition of a bear advancing towards him, and reportedly died of fright a few days later.[199] In October 1817, a tubular, glowing apparition was claimed to have been seen in the Jewel House by the Keeper of the Crown Jewels, Edmund Lenthal Swifte. He said that the apparition hovered over the shoulder of his wife, leading her to exclaim: «Oh, Christ! It has seized me!» Other nameless and formless terrors have been reported, more recently, by night staff at the Tower.[200]

See also[edit]

- Castles in Great Britain and Ireland

- List of buildings that survived the Great Fire of London

- List of castles in England

- List of prisoners of the Tower of London

- Zammitello Palace, built in imitation of the Tower of London

References[edit]

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Wakefield Tower was originally called Blundeville Tower.[23]

- ^ Flambard, Bishop of Durham, was imprisoned by Henry I «for the many injustices which Henry himself and the king’s other sons had suffered».[65]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Latest Visitor Figures». Association of Leading Visitor Attractions. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ «History». Historic Royal Palaces. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Tower of London Frequently Asked Questions, Historic Royal Palaces, archived from the original on 27 December 2013, retrieved 2 December 2015

- ^ Vince 1990 in Creighton 2002, p. 138

- ^ Creighton 2002, p. 138

- ^ Parnell 1993, p. 11

- ^ a b Parnell 1993, pp. 32–33

- ^ Wilson 1998, p. 39

- ^ Parnell 1993, p. 49

- ^ Friar 2003, p. 163

- ^ Allen Brown 1976, p. 15

- ^ a b c Allen Brown 1976, p. 44

- ^ a b c Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 16

- ^ a b Parnell 1993, pp. 19–23

- ^ a b c Parnell 1993, p. 22

- ^ Michette et al. 2020

- ^ a b c d Parnell 1993, p. 20

- ^ Friar 2003, p. 164

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 17

- ^ a b Allen Brown & Curnow 1984, p. 12

- ^ Parnell 1993, p. 32

- ^ a b Parnell 1993, p. 27

- ^ a b c Allen Brown & Curnow 1984, p. 17

- ^ Parnell 1993, p. 28

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 31

- ^ Allen Brown & Curnow 1984, pp. 17–18

- ^ Parnell 1993, p. 65

- ^ a b Parnell 1993, p. 67

- ^ a b Allen Brown & Curnow 1984, pp. 15–17

- ^ Parnell 1993, p. 24

- ^ a b Parnell 1993, p. 33

- ^ a b Parnell 1993, p. 10

- ^ Parnell 1993, pp. 34–35

- ^ Parnell 1993, p. 42

- ^ Wilson 1998, p. 34

- ^ Parnell 1993, p. 46

- ^ a b Parnell 1993, p. 55

- ^ Parnell 1993, p. 29

- ^ Bloody Tower, Historic Royal Palaces, archived from the original on 28 April 2010, retrieved 22 July 2010

- ^ a b c Parnell 1993, p. 47

- ^ Parnell 1993, p. 58

- ^ a b Parnell 1993, p. 64

- ^ Parnell 1993, p. 70

- ^ Historic England. «Waterloo Block (1242210)». National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ «Historic Royal… Patchworks?». Historic Royal Palaces. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ a b Parnell 1993, pp. 35–37

- ^ Parnell 1993, pp. 43–44

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 34

- ^ a b Parnell 1993, pp. 40–41

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 36

- ^ Parnell 1993, pp. 38–39

- ^ Parnell 1993, p. 43

- ^ Parnell 1993, p. 61

- ^ a b c Allen Brown & Curnow 1984, p. 5

- ^ a b Liddiard 2005, p. 18

- ^ Bennett 2001, p. 45

- ^ Bennett 2001, pp. 45–47

- ^ a b Wilson 1998, p. 1

- ^ Allen Brown 1976, p. 30

- ^ Allen Brown 1976, p. 31

- ^ Friar 2003, p. 47

- ^ a b Wilson 1998, p. 2

- ^ Allen Brown & Curnow 1984, pp. 5–9

- ^ Allen Brown & Curnow 1984, pp. 9–10

- ^ Wilson 1998, p. 5

- ^ Wilson 1998, pp. 5–6

- ^ Allen Brown & Curnow 1984, pp. 12–13

- ^ a b c d e Parnell 1993, p. 54

- ^ Creighton 2002, p. 147

- ^ a b Wilson 1998, pp. 6–9

- ^ Wilson 1998, pp. 14–15

- ^ Allen Brown & Curnow 1984, p. 13

- ^ Allen Brown & Curnow 1984, p. 15

- ^ Gillingham 2002, p. 304

- ^ Wilson 1998, pp. 13–14

- ^ a b Wilson 1998, pp. 17–18

- ^ Wilson 1998, pp. 19–20

- ^ a b Allen Brown & Curnow 1984, p. 20

- ^ Wilson 1998, p. 21

- ^ Allen Brown & Curnow 1984, pp. 20–21

- ^ Wilson 1998, pp. 24–27

- ^ Wilson 1998, p. 27

- ^ a b Parnell 1993, p. 35

- ^ Cathcart King 1988, p. 84

- ^ Parnell 1993, pp. 35–44

- ^ Wilson 1998, pp. 31

- ^ Wilson 1998, pp. 34, 36

- ^ «Records of the Royal Mint». The National Archive. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ «Tower of London World Heritage Site Management Plan» (PDF). Historic Royal Palaces. pp. xi–xii.

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 41

- ^ Lapper & Parnell 2000, p. 28

- ^ Wilson 1998, p. 40

- ^ Costain 1958, pp. 193–195

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1321–1327. p. 29

- ^ Strickland 1840, p. 201

- ^ Friar 2003, p. 235

- ^ Wilson 1998, pp. 34, 42–43

- ^ a b Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 42

- ^ Wilson 1998, p. 45

- ^ a b c Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 51

- ^ a b c Parnell 1993, p. 53

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 44

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 45

- ^ a b Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 46

- ^ a b c Impey & Parnell 2000, pp. 46–47

- ^ a b Horrox 2004

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (29 October 2013). «Roman eagle found by archaeologists in City of London». The Guardian.

- ^ Weir 2008, pp. 16–17

- ^ Thurley 2017

- ^ a b Yeoman Warders, Historic Royal Palaces, archived from the original on 29 July 2010, retrieved 21 July 2010

- ^ Bowle 1964

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 73

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 52

- ^ Wilson 1998, pp. 10–11

- ^ a b c d e Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 91

- ^ a b Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 92

- ^ Black 1927, p. 345

- ^ a b Parnell 1993, p. 117

- ^ a b c Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 94

- ^ Plowden 2004

- ^ Collinson 2004

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 47

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 57

- ^ Semark, H.W. (1997). The Royal Naval Armament Depots of Priddy’s Hard, Elson, Frater and Bedenham, 1768–1977. Winchester: Hampshire County Council. p. 124.

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 74

- ^ a b Impey & Parnell 2000, pp. 54–55

- ^ Parnell 1993, pp. 76–77

- ^ Dictionary of British Sculptors 1660-1851 by Rupert Gunnisp.129

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 78

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, pp. 79–80

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 81

- ^ Executions at The Tower of London (PDF), Historic Royal Palaces, archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2011, retrieved 31 July 2010

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 123

- ^ Sellers 1997, p. 179

- ^ Parnell 1993, pp. 117–118

- ^ Osbourne 2012, p. 167

- ^ Medieval Palace, Historic Royal Palaces, archived from the original on 30 May 2010, retrieved 19 July 2010

- ^ a b Parnell 1993, p. 111

- ^ a b Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 117

- ^ Parnell 1993, p. 96

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, pp. 118–121

- ^ a b Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 124

- ^ On This Day 1974: Bomb blast at the Tower of London, BBC News Online, 17 July 1974

- ^ «Regimental History», British Army website, Royal Regiment of Fusiliers, 2010, archived from the original on 5 September 2010, retrieved 16 June 2010

- ^ Royal Regiment of Fusiliers (London) Museum, Army Museums Ogilby Trust, archived from the original on 26 July 2011, retrieved 16 June 2010

- ^ The Ceremony of the Keys, Historic Royal Palaces, 2004–2010, archived from the original on 4 June 2010, retrieved 16 June 2010

- ^ The Queen’s Guard, British Army, 2010, archived from the original on 6 September 2010, retrieved 16 June 2010

- ^ Yeomen Warders, Royal Household of the United Kingdom, 2008–2009, retrieved 16 June 2010

- ^ Gun salutes, Royal Household of the United Kingdom, 2008–2009, archived from the original on 17 March 2015, retrieved 16 June 2010

- ^ Cause and principles, Historic Royal Palaces, archived from the original on 22 December 2009, retrieved 30 April 2010

- ^ UNESCO Constitution, UNESCO, archived from the original on 29 March 2019, retrieved 17 August 2009

- ^ Tower of London, UNESCO, retrieved 28 July 2009

- ^ UNESCO warning on Tower of London, BBC News Online, 21 October 2006

- ^ Medieval Palace: Press Release, Historic Royal Palaces, archived from the original on 21 December 2007, retrieved 19 July 2010

- ^ The Constable of the Tower, Historic Royal Palaces, archived from the original on 30 November 2009, retrieved 27 September 2010

- ^ Maj Gen Keith Cima: Resident Governor HM Tower of London, Historic Royal Palaces, archived from the original on 6 December 2008, retrieved 27 September 2010

- ^ General Sir Gordon makes history as first Royal Marine in charge of Tower of London, Royal Navy, 7 April 2022

- ^ Jerome 2006, pp. 148–149

- ^ «Why the Tower of London has a ravenmaster — a man charged with keeping at least six ravens at the castle at all times», National Post, 30 September 2018, retrieved 1 October 2018

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th Edition, 1993. Article on Tower Hamlets

- ^ a b The Metropolitan Borough of Stepney, Official Guide (10th ed.). Ed J Burrows & Co. 1962. pp. 25–29.

- ^ Bethnal Green, ed. (1998). «Stepney: Early Stepney». A History of the County of Middlesex. Vol. 11. T F T Baker. pp. 1–7. Retrieved 3 December 2021 – via British History Online.

- ^ a b Wilson 1998, p. 29

- ^ a b Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 106

- ^ «British Crown Jewels». Royal Exhibitions. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ Gibson, William (23 June 2011). A Brief History of Britain 1660 — 1851. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 9781849018159 – via Google Books.

- ^ Rennison, Nick (31 August 2010). The Book Of Lists London. Canongate Books. ISBN 9781847676665 – via Google Books.

- ^ Colonel Blood’s raid, Historic Royal Palaces, archived from the original on 6 July 2010, retrieved 22 June 2010

- ^ «The Royal Collection at The Tower of London: Jewel House». www.royalcollection.org.uk.

- ^ Humphreys, Rob (4 January 2010). The Rough Guide to London. Penguin. ISBN 9781405384759 – via Google Books.

- ^ «The Crown Jewels». Historic Royal Palaces.

- ^ Kristen Deiter (23 February 2011). The Tower of London in English Renaissance Drama: Icon of Opposition. p. 34. ISBN 9781135894061.

- ^ a b Steve Connor (25 March 2008). «Royal Menagerie lions uncovered». The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f «Menagerie». Royal Armouries. Retrieved 21 July 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b «Medieval Lion Skulls Reveal Secrets of Tower of London «Zoo»«. National Geographic. 11 November 2005.

- ^ Historic Royal Palaces. «Discover The Incredible Tales Of The Tower Of London’s Royal Beasts». hrp.org.uk. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013.

- ^ Lewis, Matthew (15 October 2016). Henry III: The Son of Magna Carta. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445653587 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mount, Toni (15 May 2016). A Year in the Life of Medieval England. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445652405 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Jones, Nigel (2 October 2012). Tower: An Epic History of the Tower of London. St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 9781250018144 – via Google Books.

- ^ William Harrison Ainsworth (1858). The Tower of London: An Historical Romance. p. 249.

- ^ Blunt 1976, p. 17

- ^ «The Tower of London: Discover The Wild Beasts That Once Roamed The Royal Menagerie». Historic Royal Palaces. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (18 October 1999). «Tower’s old grizzly back on show». The Guardian.

- ^ Kisling, Vernon N. (18 September 2000). Zoo and Aquarium History: Ancient Animal Collections To Zoological Gardens. p. 51. ISBN 9781420039245.

- ^ Bennett, Edward Turner (1829). The Tower Menagerie: Comprising the Natural History of the Animals Contained … p. 15. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ African History at the Tower of London. Tower Hamlets: Tower Hamlets African and Caribbean Mental Health Organisation. 2008. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-9551368-7-0.

- ^ «Big cats prowled London’s tower». BBC News. 24 October 2005.

- ^ Michael Allaby (2010). Animals: From Mythology to Zoology. p. 68. ISBN 9780816061013.

- ^ a b Parnell 1993, p. 94

- ^ Parnell, Geoffrey (2 December 1993). Book of the Tower of London. B. T. Batsford. ISBN 9780713468649 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (18 October 1999). «Tower’s old grizzly back on show». The Guardian.

- ^ Royal Beasts at Tower of London, View London, retrieved 14 April 2011

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 91

- ^ Nearing 1948, p. 229

- ^ Nearing 1948, pp. 231–232

- ^ Nearing 1948, p. 228

- ^ Nearing 1948, p. 233

- ^ Farson 1978, pp. 14–16

- ^ a b Hole 1951, pp. 61–62, 155

- ^ Roud 2009, pp. 60–61

General bibliography[edit]

- Allen Brown, Reginald (1976) [1954]. Allen Brown’s English Castles. The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-069-6.

- Allen Brown, Reginald; Curnow, P (1984). Tower of London, Greater London: Department of the Environment Official Handbook. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11-671148-9.

- Bennett, Matthew (2001). Campaigns of the Norman Conquest. Essential Histories. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-228-9.

- Black, Ernest (1927). Torture under English Law. University of Pennsylvania Law Review and American Law Register. Vol. 75. pp. 344–348. doi:10.2307/3307506.

- Blunt, Wilfred (1976). The Ark in the Park: The Zoo in the Nineteenth Century. Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-89331-9.

- Bowle, John Edward (1964). Henry VIII: A Biography. Allen & Unwin.

- Cathcart King, David James (1988). The Castle in England and Wales: an Interpretative History. Croom Helm. ISBN 978-0-918400-08-6.