It never fails. We’ll be out walking the dogs or preparing dinner or working out when Akemi will turn to me and ask: “What’s the English world for…”. And then proceed to lay out the most ridiculously detailed scenario like “What’s the English for when you’re trying to lose weight and keep at it for a while but, eventually, you give up and have, say, a piece of cake ?” or “What’s the English world for when you’re not hungry but you have something to eat because your mouth feels lonely?”. I’ll inform her there is no English equivalent, word or phrase, that perfectly encapsulates such a comprehensive definition and she is, as always, surprised and disappointed. Because, you see, the Japanese seem to have a word FOR EVERYTHING!

For example…

Age-otori: The state of looking far worse following a haircut.

Arigata-meiwaku: When somebody does you a favor you didn’t want them to do but they went ahead and did it anyway and, as a result, caused you a huge inconvenience but social convention requires you to thank them anyway.

Aware: The bittersweetness of fading moment.

Bakku-shan: A woman that looks far better from behind than from the front.

Boketto: The act of staring blankly out into space, devoid of any thoughts.

Happou bijin: The act of being ungenuinely nice to everyone out of fear of being disliked.

Karoshi: Death from overwork.

Kenjataimu: Period directly after the sexual act when a man is free of desire and can think clearly.

Kintsugi: The act of repairing broken pottery with gold.

Koi no yokan: The feeling, upon first meeting someone, that you will eventually fall in love.

Kuchi zamishi: When you’re not hungry but you eat because your mouth is “lonely”.

Kyoikumama: A mother who relentlessly pushes her child to study.

Shrinrin-yoku: “Forest bathing” – visiting a forest for some R&R.

Tsujigiri: The act of trying out a new sword on some random stranger.

Tsundoku: The act of buying a book and never getting around to reading it.

Wabi-sabi: A world view that accepts the transcendent and imperfect nature of life.

Yoko meshi: The stress experienced speaking a foreign language.

Familiar with any words in other languages that lack an English equivalent. List away!

on 05/15/2014 •

When talking about photography, English doesn’t cut it. As it turns out, Japanese does.

The Japanese have a word for everything, I think. I just learned “Komorebi. It means sunlight filtering through the leaves of trees,” and by extension, the natural filtering of light through anything.

It’s just the word I’ve needed. I’ve been chasing that light for more than 40 years.

Bokeh is my previously learned favorite Japanese photographic term. It defines something difficult to say in English: “Bokeh means the aesthetic quality of blur in the out-of-focus areas of an image produced by a lens.”

Like this?

Or that?

I’m sure there’s more, but this is my vocabulary lesson for the day.

Categories: #Photography, Light and Lights, Words

Tags: #Photography, bokeh, depth of field, Japanese, komorebi, sunlight, terminology

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

есть слово для

было слова для

есть специальное слово для

нет слова для

было слов, чтобы

нет такого слова

нет слов для

We have a word for animals that never feel distress, anxiety, fear, and pain.

У нас есть слово для животных, которые никогда не чувствуют стресса, тревоги, страха и боли.

They even have a word for that light, misty rain that seems to never stop — txirimiri.

У них даже есть слово для этого, туманный дождь, который, кажется, никогда не остановить-txirimiri.

Ironically the ancient Greek did not eaves have a word for death.

Интересно У древних греков не было слова для обозначения религии.

Ancient Greek does not have a word for religion.

We have a word for that; it’s called hypocrisy.

We even have a word for it, ‘hypocrite’.

They do say the Greeks have a word for it.

The Danes have a word for the thing you desperately want but can’t seem to manifest: hygge.

У датчан есть слово для того, чего вы отчаянно хотите, но не можете выразить: «хюгге».

Urban planners and city officials have a word for what the Netherlands and quite a few other European countries are experiencing: overtourism.

У голландских градостроителей и городских чиновников есть слово для того, что испытывают Нидерланды и довольно много других европейских стран, это называется овертуризм.

The locals have a word for it — Gemütlichkeit — that untranslatable intermingling of cosiness, well-being and laid-back attitude.

У местных жителей есть слово для этого — Gemütlichkeit — это непереводимое смешение уюта, благополучия и непринужденного отношения.

The Greeks have a word for cousin, and it was not used.

В Греческом есть слово для двоюродного брата, но оно не используется.

Grownups have a word for that.

SEALs have a word for that.

They have a word for that: leadership.

The problem is we don’t even have a word for this concept, much less a science to study it.

Проблема у нас даже нет слова для этого понятия, значительно меньше науки, изучающие его.

I don’t have a word for that yet, but I will.

We don’t seem to have a word for that.

And the fundamental problem is we don’t actually have a word for this stuff.

Фундаментальная проблема в том, что для этого у нас слова нет.

They don’t have a word for ‘government’.

Psychiatrists have a word for something like this: delusional.

Результатов: 168. Точных совпадений: 168. Затраченное время: 623 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

By

Last updated:

March 16, 2023

With these 250 essential Japanese words and phrases, you’ll be prepared for any situation.

The Japanese language might take years to master, but what if you need to get through a conversation right now? Start by learning these everyday conversational words and crucial survival phrases. The rest will follow.

And you can just click on a word or phrase to hear its pronunciation.

Contents

- Greetings and Starters

- Basic Conversation

- Saying Yes and No

- Saying “I Don’t Understand”

- Please, Thank You and Apologies

- Saying Goodbye

- Travel Vocabulary

- Basic Question Words

- Japanese Pronouns

- Phrases for Dining

- Phrases for Social Gatherings

- Phrases for Home

- Shopping in Japanese

- Phrases for Casual Conversations

- Japanese Slang

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Greetings and Starters

ohayou gozaimasu: おはようございます — Good morning

The casual version is ohayou (おはよう ). In a workplace, someone greeting a colleague for the first time that day might use this phrase even if the clock reads 7 p.m.

konnichiwa: こんにちは — Hello / good afternoon

Konnichiwa can be used any time of day as a general greeting, but it’s most commonly used between 11 a.m. and 5 p.m.

hisashiburi: 久しぶり — It’s been a while

Basic Conversation

o namae wa nan desu ka?: お名前は何ですか? — What’s your name?

This is a polite way to ask someone for their name. The more informal version is O namae wa? (おなまえは? ) — Your name is…?

… desu: …です — I am … / It is …

It’s easiest to think of desu like the English word “to be.” Unlike “to be,” desu stays the same regardless of the subject.

For example:

- Tomu desu (トムです ) — I’m Tom

- Atsui desu (暑い です ) — It’s hot/I’m hot

- Osoi desu (おそいです ) — You’re late!

watashi wa … desu: 私は…です — I am …

This is a longer version of the previous phrase. You also use this to say your name:

Watashi wa Pouru desu.

私はポールです。

I am Paul.

But this sentence pattern can also be used for any adjectives. For example:

- samui (寒い ) — Cold

- ureshii (嬉しい ) — Happy

- nemui (眠い ) — Sleepy

watashi wa … karakimashita: 私は… から来ました — I’m from …

Simply use this to describe what country you’re from. Here’s a list of some countries in Japanese:

- Igirisu (イギリス ) — United Kingdom

- Amerika (アメリカ ) — United States of America

- Ousutoraria (オーストラリア ) — Australia

- Doitsu (ドイツ ) — Germany

- Chuugoku (中国 ) — China

- Kangoku (韓国 ) — Korea

Many others are almost identical in Japanese, such as:

- Kanada (カナダ ) — Canada

- Furansu (フランス ) — France

- Supein (スペイン ) — Spain

If you don’t know how to say your country’s name, say it in English—chances are, people will understand where you mean.

suki desu: 好きです — I like it

You can say what you like by adding … ga suki desu (が好きです ). For example:

Okashi ga suki desu.

お菓子が好きです。

I like sweets.

ii desu yo: いいですよ — It’s good

You’ll often also hear ii yo (いいよ ), especially from women/girls.

suki dewa arimasen: 好きではありません — I don’t like it

dame desu: ダメです — It’s no good

In more casual conversation, you can also say just dame (だめ ) or dame da (だめだ).

takusan: たくさん — A lot

Takusan is similar to ooi (多い ). The main difference is that takusan can function as a noun, adjective or adverb, while ooi is only an adjective. For example:

Kooen ni hana ga takusan arimasu.

公園に花がたくさんあります。

There are lots of flowers in the park.

sukoshi: 少し — A little

Here’s an example of it in use:

Koohii ni sato wo sukoshi onegaishimasu.

コーヒーにさとをすこしお願いします。

A little sugar in my coffee, please.

ima nanji desu ka?: 今何時ですか? — What time is it?

In casual situations, saying Ima nanji? (今何時 ) will work just fine.

… ji desu: …時です — It’s … o’clock

This plus a number is all you need to tell the time! For example:

Ichiji desu.

一時です。

It’s 1 o’clock.

nihongo de hanashimashou: 日本語で話しましょう — Let’s talk in Japanese

Saying Yes and No

hai: はい — Yes

Another way to say “yes” is with non-verbal cues like nodding your head up and down or giving a thumbs up.

soudesuka: そうですか — That is right

Saying this while nodding is a polite way to show that you’re paying attention when someone tells you something new. You can also use soka そっか, soudane そうだね or soune そうね for variety. These are less formal, but generally acceptable and certainly not rude.

sou desu: そうです — That’s right

You can also say hai, sou desu (はい ,そうです ) — Yes, that’s right. However, the hai is implied and you can leave it off.

sou: そう — That’s right (informal)

un: うん / aa: ああ / ee: ええ

The Japanese use aizuchi (相槌 ), which are simple words or gestures that all mean “yes,” to indicate you’re listening. They don’t have a strict “definition,” but are similar to saying “uh-huh” or “mm-hm” in English.

mochiron: もちろん — Of course

ii desu yo: いいですよ — Okay

This literally means “That’s good!” and as such can be used to show your approval of something.

iie: いいえ — no

This is the no-nonsense way to say “no.” However, Japanese culture prefers less direct approaches.

There are also several non-verbal ways to express “no.” Rubbing the back of the neck, making an “X” with both arms or even taking in a deep breath all mean “no.”

uun: ううん

This is a sound that indicated you don’t quite agree, similar to saying “Umm…” in English.

iya: いやー

Whether this interjection is being used to mean “no” depends on the context. If you suggest dinner and someone responds with iya…, then their response is a non-committal “Well, you see…”

dame: だめ — It’s no good / You can’t do that

This is a fairly assertive way to say no. It’s saying that something is pointless or shouldn’t be done. This is one to use when someone is doing something you don’t want them to do, or if you’re trying to accomplish something that seems like it won’t work.

chotto…: ちょっと… — A little…

If you use chotto, remember to trail off at the end, as you’re basically saying, “It’s a little…” For instance, if someone asks what you’re doing tomorrow afternoon with the aim to meet up, you can respond “Chotto…” to mean that tomorrow afternoon’s not an ideal time for you.

In business settings, two simple phrases to convey “no” without saying “no” are:

muzukashii desu: 難しいです — It’s difficult

kangaete okimasu: 考えておきます — I’ll think about it

While not outright saying “no,” they express a refusal to the listener without sounding impolite.

Saying “I Don’t Understand”

wakarimasen: 分かりません — I don’t understand

If you’re around friends, you can use the casual variant, wakaranai (わからない ).

mou ichido itte kudasai: もう一度言ってください — Please say that again

yukkuri onegai shimasu: ゆっくりお願いします — Slowly, please

kikoemasen deshita: 聞こえませんでした — I didn’t hear that

mou ichido itte kudasai: もう一度言ってください — Please say it again

Please, Thank You and Apologies

arigatou gozaimasu: ありがとうございます — Thank you

The friendlier, more casual way to say thanks is arigatou (ありがとう ). You’ll also see its abbreviation, ari (あり ), pretty often on Japanese message boards. A friend might just thank you with doumo (どうも ).

iroiro arigatou gozaimashita: 色々ありがとうございました — Thank you for everything

douitashimashite: どういたしまして — You’re welcome

Although this is technically the correct response to “Thank you,” it’s rarely used these days in casual Japanese conversation. The following phrase is much more common.

mondai nai desu: 問題ないです — No problem

kudasai: ください — Please (requesting)

The word kudasai is used when making requests, as in these examples:

Isoide kudasai.

急いでください。

Please hurry.

Koohii o kudasai?

コーヒーをください?

Can I please have a coffee?

douzo: どうぞ — Please (offering)

Using douzo is like saying, “Please go ahead.” You can use it when ushering someone through the door before you, or offering a coworker some delicious snacks, for example.

otsukaresama desu: お疲れ様です — Thank you for your efforts

This expression is often said as a parting sentiment when you, or someone else, finishes their work. You can think of it as saying, “That’s a wrap for the day.”

shitsurei shimasu: 失礼します — Excuse me (for my rudeness)

Another expression commonly heard in the office, shitsurei shimasu is used when you’re leaving a room. It’s similar to saying, “Sorry to have bothered you.” You can also end a formal or polite phone call with this phrase.

sumimasen: すみません — Excuse me, I’m sorry

Sumimasen is often used to say “Excuse me” (like if you need help getting directions ) and “Sorry” (like when you accidentally nudge someone). It can also be said as a “thank you” when you’ve troubled someone (Think: “Thanks for letting me put you out”).

gomen nasai: ごめんなさい — I’m sorry

In casual situations and among family members and friends, gomen nasai replaces sumimasen when saying sorry.

gomen: ごめん — I’m sorry

You can use this less formal expression among those who are close to you.

Saying Goodbye

jaa, mata!: じゃあ、また! / mata ne: またね — See you!

You can use dewa mata (ではまた ) for a slightly more formal expression. There’s also jaa ne (じゃあね ), and then jaa mata ashita ne (じゃまた明日ね ) — see you tomorrow.

o genki de: お元気で — Take care

If “see you” is a little too casual for you, then you can say o genki de instead. This literally means “be healthy” and can be used to say, “Good luck!”

meado o oshiete moraemasu ka?: メアドを教えてもらえますか? — Could I have your e-mail address?

If that’s a little too long to memorize, you can ask:

Meruado o oshiete?

メルアドを教えて?

Can I get your e-mail address? (Literally, “Teach me your email?”)

tegami kaku yo: 手紙書くよ — I’ll write you letters

tsuitara, denwa shimasu/meeru shimasu: 着いたら、電話します / メールします — I’ll call/email you when I arrive

mata sugu ni kimasu yo: またすぐに来ますよ — I’ll be back soon

asobi ni kite kudasai ne: 遊びに来てくださいね — Come visit me

watashi no ie dewa, itsumo anata o kangei shimasu yo!: わたしの家でわ, いつもあなたを感じますよ! — You’re always welcome in my home!

Travel Vocabulary

These handy phrases will give you what you need to get around Japan and, in case of an emergency, ask for help.

sumimasen, chikatetsu / eki wa doko desu ka: すみません、地下鉄 / 駅はどこですか? — Excuse me, where’s the subway/station?

kono densha wa … eki ni tomarimasu ka?: この電車は… 駅に止まりますか? — Does this train stop at … station?

kono basu wa … ni ikimasu ka?: このバスは…にいきますか? — Does this bus go to … ?

takushi nori ba wa dokodesu ka?: タクシーのりばはどこですか? — Where is the taxi platform?

… made tsureteitte kudasai: …まで連れて行ってください — Please take me to …

Use this phrase to tell the taxi driver where you want to go.

yoyaku wo shitainodesuga: 予約をしたいのですが — I’d like to make a reservation.

yoyaku shiteimasu: 予約しています — I have a reservation.

chekkuauto wa nanji desu ka?: チェックアウトは何時ですか? — What time is checkout?

michi ni mayotte shimaimashita: 道に迷ってしまいました — I’m lost.

tasukete!: たすけて! — Help! (for emergencies)

tetsudatte kuremasen ka?: てつだってくれませんか? — Can you help me? (for everyday situations)

keisatsu / kyuukyuusha wo yondekudasai: 警察 / 救急車を呼んでください — Please call the police / an ambulance.

Here’s a useful note: the emergency numbers in Japan are 119 for an ambulance and 110 for the police.

Basic Question Words

Knowing some of the essential Japanese question words will go a long way toward getting your questions across to Japanese speakers.

nani: 何 — What

Nani can be used alone or in a sentence. When placed before desu, the word nani drops its -i and becomes nan. For example:

Kore wa nan desu ka?

これは何ですか?

What is this?

doko: どこ — Where

Doko is used when asking for a location, like this:

Toire wa doko desu ka?

トイレはどこですか ?

Where is the toilet?

If you don’t know the word for the place you’re looking for, another helpful option is pointing to it on a map and asking:

Doko desu ka?

どこですか ?

Where is it?

dare: 誰 — Who

If you’re referring to a specific person, add it before dare:

Kanojo wa dare desu ka?

彼女は誰ですか?

Who is she?

itsu: いつ — When

doushite: どうして — Why

If you need to ask politely, say it as Doushite desu ka? (どうしてですか?). If you’re with friends or family, you can use the casual form nande (何で ) instead.

naze: なぜ — Why

This is pretty similar to doushite, but a bit more formal. Naze is also used to ask the reason behind something, while doushite has a nuance of “how” to it.

ikura: いくら — How much

ikutsu: いくつ — How many

This is a general word to ask “how much” or “how many” of a numerical amount. For example:

Okashi wa ikutsu hoshii desu ka?

おかしはいくつ星いですか?

How many snacks do you want?

It can also be used to ask someone’s age:

Oikutsu desu ka?

おいくつですか?

How old are you?

nan …: 何… — How many

Nan is a more specific way of asking how much of something there is. It works by combining nan with a counter, such as:

- nanbon (何本 ) — How many long cylindrical objects?

- nannin (何人 ) — How many people?

- nanmai (何枚 ) — How many sheets?

To learn more about how to talk about quantities, check out our post about Japanese counting and numbers.

dochira: どちら — Which one (out of two)?

dore: どれ — Which one (out of many)?

Japanese Pronouns

Japanese has a wide variety of pronouns you can use, helping you make your sentences more direct when you’re referring to yourself, your friend or your friend’s boyfriend.

watashi: 私 — I (all genders)

Watashi is the go-to in polite situations. It’s sometimes pronounced watakushi (私) for extra formality, and some female speakers may shorten it to atashi (私) in casual settings.

boku: 僕 — I (usually male)

Boku is mostly used by men and boys when they’re among friends. Nowadays, some girls use boku, as well, which gives off an air of tomboyish-ness.

ore: 俺 — I (male)

While boku is sometimes used by girls, ore is an exclusively male pronoun. It gives off a bit of a rough image, so it’s only used among close friends in casual situations.

jibun: 自分 — Myself / yourself / themselves

Jibun is used to refer to a sense of self. It can also take a variety of forms, like jibun no (自分の ) — one’s own (something), and jibun de (自分で ) — by yourself. It’s also a more polite way of referring to someone else.

anata: あなた — You

Anata translates to “you,” but it’s not used in the way it’s used in English. Most of the time, Japanese omits “you” altogether, favoring a person’s name instead. This form can be used as a term of endearment between couples.

kimi: 君 — You

Kimi is largely used to talk to someone of lower status than yourself, such as a boss talking to their employees. It’s also used to add some pizzazz to writing, such as in the hit movie “Kimi no na wa” (君のなわ ) — Your Name.

kare: 彼 — He / him

While the Japanese language does favor using a person’s name over second or third person pronouns, using kare is perfectly okay. Plus, kare can be used to refer to someone’s boyfriend.

kanojo: 彼女 — She / her

Same as kare, but for women. In the same way as kare, kanojo can also be used to refer to a girlfriend!

tachi: …たち — “… and company” (pluralizes pronouns)

To turn a pronoun into a plural, just add -tachi. For example:

- watashi tachi (私たち ) — We

- kimi tachi (君たち ) — You (plural)

- kanojo tachi (彼女たち ) — A group of women

- Sasuke tachi (サスケたち ) — Sasuke and his friends

kore: これ — This

Used to refer to something close to the speaker.

sore: それ — That

Used to refer to something close to the listener.

are: あれ — That (over there)

Used to refer to something far from both the speaker and the listener.

Phrases for Dining

Okay, now that we’ve gotten the formalities out of the way, it’s time to talk about what’s really important: food!

onaka ga suite imasu: お腹が空いてます — I’m hungry

This literally means your stomach has become empty. Some variations are:

- onaka ga suita (お腹が空いた ), informal

- onaka ga hetta (お腹が減った ), informal, often interchanged with onaka ga suita

- hara hetta (はらへった ), masculine

- onaka ga pekopeko (お腹がぺこぺこ ), onomatopoeia that means your stomach is growling

mada tabete imasen: まだ食べていません — I haven’t eaten yet

For a more casual version, go ahead and say mada tabeteinai (まだ食べていない ).

menyuu, onegai shimasu: メニュー、お願いします — Please bring me a menu

You can also opt for the more formal version:

Menyuu, onegai dekimasu ka?

メニュー、お願いできますか?

May I have the menu?

sore wa nan desu ka?: それは何ですか? — What’s that?

kore o tabete mitai desu: これを食べてみたいです — I’d like to try this

… o kudasai: …をください — I’d like …

State whatever you’d like to order, and follow it with … o kudasai. For example:

Koohii o kudasai.

コーヒーをください?

I’d like a coffee, please.

… ga arimasu ka?: …がありますか? — Do you have … ?

As a reply, you’ll simply hear arimasu ( あります).

… tsuki desu ka: …付きですか? — Does it come with … ?

If you want to know if certain foods are included with your order, use this to ask. For example:

Furaido poteto tsuki desu ka?

フライドポテト付きですか?

Does it come with fries?

… ga taberaremasen: …が食べられません — I can’t eat …

This is a good phrase to learn for vegetarians, vegans and other people with dietary restrictions. For example, niku (肉 ) is “meat” and sakana (魚 ) is “fish.” So if you’re on a strict veg diet, you can say:

Niku to sakana ga taberaremasen.

肉と魚が食べられません。

I can’t eat meat and fish.

… arerugii ga arimasu: …アレルギーがあります — I’m allergic to …

State whatever you’re allergic to and add this phrase to the end. Just to be safe rather than sorry, you can ask: … ga haitte imasu ka? (が入っています か?) which means, “Are / Is there any … in it?” For example:

Tamago ga haitte imasu ka?

卵が入っていますか?

Are there any eggs in it?

oishii desu!: おいしいです! — It’s delicious!

If you’re eyeballing a slice of cake, then oishisou (美味しそう ), meaning “It looks delicious,” could be useful. A casual and “manly” way to say something is delicious is umai (上手い ).

mazui desu: まずいです — It’s terrible

onaka ga ippai desu: お腹が一杯です — I’m full

okawari: おかわり — Another serving, please

hai, onegaishimasu: はい、お願いします — Yes, please (when offered food)

iie, kekkoudesu: いいえ、結構です — I’m fine, thank you (when offered food)

itadakimasu: いただきます — Let’s dig in

This is used before digging into your meal, similar to “Bon appétit.”

okanjou / okaikei, onegai shimasu: お勘定 / お会計、お願いします — Check, please

warikan ni shite kudasai: 割り勘にしてください — Split the check, please

betsubetsu de onegaishimasu: 別別でお願いします — We’ll pay separately, please

gochisousama deshita: ごちそうさまでした — Thanks for the meal

Like itadakimasu, this phrase is a fixture at every meal. You say this when the meal is finished.

Phrases for Social Gatherings

Show your friends and colleagues you know how to have fun with these phrases during social gatherings.

tabemashou: 食べましょう — Let’s eat

When planning a fun day out with friends, there are a few casual phrases to use when discussing plans. If you decide to have lunch, state tabemashou!

nomimashou: 飲みましょう — Let’s drink

You can also suggest grabbing a drink by using this phrase.

ikimashou: 行きましょう — Let’s go

Once your plans are decided, it’s time to head out by saying this phrase.

yatta!: やったー! — Yay!

kanpai!: 乾杯! — Cheers!

Once the party has begun, it’s essential to clink your glasses together and say kanpai! You say this phrase before drinking, not after.

ureshii desu: 嬉しいです — I’m happy

okawari o kudasai: お代わりをください — Refill, please

daijoubu desu: 大丈夫です — I’m fine – This is a polite way to respectfully say “no,” such as when you’re done drinking for the night.

Phrases for Home

tadaima: ただいま — I’m back

Everyone says this when they arrive home. If you go out, say this when you get back to let everyone know you’ve arrived home safely. If you want to, you can also say it when coming back from the bathroom; it tends to go down well.

okaeri nasai: おかえりなさい — Welcome back

This is said in response to tadaima. You can use this when someone else gets home, like when a parent returns from work or when a sibling gets back from cram school.

ofuro ni haitte mo ii desu ka?: お風呂に入ってもいいですか? — May I take a bath?

In Japan, most families take a bath every night, and if you’re staying somewhere like with a host family, you’ll be welcome to have one too if you ask.

If you’d prefer to take a shower (I did), you can just replace the word ofuru (お風呂 ) — bath with shawaa (シャワー ) — shower. Just make sure you don’t throw the bath water out when you’re done, as the family shares the hot water.

oyasumi nasai: おやすみなさい — Good night

You can also leave off the -nasai to make it less formal.

Shopping in Japanese

With the streets brimming with food stalls and vendors, the high-end boutiques lining Ginza and the ultra-cool and unique souvenir shops, there’s no way to avoid shopping while traveling through Japan.

irasshaimase: いらっしゃいませ — Welcome

You will hear a chorus of irasshaimase! when you enter a shop.

kore wa nan desu ka?: これは何ですか? — What is this?

kore wa nan to iu mono desu ka?: これは何というものですか? — What’s this called?

kore wa ikura desu ka?: これはいくらですか? — How much is this?

chotto takai desu: ちょっと高いです — It’s a bit expensive

If you haven’t started your adventure of learning Japanese adjectives, then here’s some essential shopping vocabulary:

- yasui (安い ) — Cheap, easy

- takai (高い ) — Expensive, high

- takakunai (高くない ) — Inexpensive

hoka no iro ga arimasu ka?: 他の色がありますか? — Do you have another color?

sore o itadakimasu: それを頂きます — I’ll take it

kurejitto kaado wa tsukaemasu ka?: クレジットカードは使えますか? — Can I use my credit card?

If you’d like to use a traveler’s check, then replace kurejitto kaado with: toraberaazu chekku (トラベラーズチェック ) — traveler’s check.

Your Suica and Pasmo cards, which are rechargeable cards you can use on Japanese trains, can also be used to pay for taxis or your groceries at select stores. You can ask:

Suika wa tsukaemasu ka?

スイカわつかえますか?

Can I use my Suica?

tsutsunde itadakemasu ka?: 包んでいただけますか? — Can I have it gift-wrapped?

Phrases for Casual Conversations

Want to sound like a native when you know minimal Japanese? There are a few common phrases you can use with friends in casual conversations.

yoroshiku onegaishimasu: よろしくお願いします — Nice to meet you (formal)

yoroshiku ne: よろしくね — Nice to meet you (casual)

doushita no?: どうしたの? — What’s wrong?

yabai: やばい — Awful or cool

While talking, your friend may mention they have an important test or date. Use yabai and depending on the context, it can mean “Awful” or “Cool.”

yokatta: 良かった (よかった) — Good, excellent, nice

This is an expression of relief, a bit like, “Oh, thank goodness!”

ganbatte: 頑張って — Do your best

This simple word means either “Good luck” or “Do your best.” In more formal situations, you’d say Ganbatte kudasai (頑張ってください ).

omedetou!: おめでとう! — Congrats!

The formal variant is Omedetou gozaimasu (おめでとうございます ) — Congratulations.

zenzen: 全然 (ぜんぜん) — Not at all (with neg. verb)

In a nutshell, zenzen is the Japanese phrase of denial. It can be used either sincerely or not, such as when answering your mother when she asks, “Am I bothering you?”

maji de?: マジで? — Really?

You can express your surprise with this casual phrase.

hontou?: 本当? (ほんとう?) — Really? / Seriously?

This word translates literally to “truth, reality, actuality, fact.” In question form, it comes across more like a surprised, “Are you serious?”

uso!: うそー! — No way!

This is another way to express surprise, which literally means “Lie!”

yappari: やっぱり — As expected

If you’re not surprised, you can use this word to say, “I knew it!”

Japanese Slang

When you’re making friends, you’ll hear tons of these terms going back and forth. Many slang terms are written in katakana, which marks them as being casual words.

ukeru: ウケる — Funny, hilarious

Say your friend made a great joke—by saying ukeru, you’ll let him know he struck your funny bone.

chou: 超 — Super

This word is used to add emphasis, like the words “really” or “very.” You could say, for example, that something is chou ukeru (超ウケる ), or very funny.

dasai: ださい — Uncool

kimoi: キモい — Gross

Kimoi is a contraction of the words kimochi (気持ち ) — feeling, and warui (悪い ) — bad.

gachi: ガチ — Totally, really, seriously

Gachi implies that something actually took place, or was really as intense as the speaker claims.

hanpa nai: 半端ない — Crazy, insane

Hanpa nai means that something is awesome or insane, but in a good way, like an epic roller coaster ride.

As you can see, context matters a lot in Japanese. To get comfortable with conversational phrases faster, try watching Japanese movies, TV shows or vlogs and look out for the expressions above—they’re very common!

FluentU is a Japanese learning app that uses real Japanese media clips, helping you learn useful phrases in context. These videos also have interactive subtitles and vocabulary lists to show you how native speakers naturally use the phrases above in conversation.

And there you have it! With these phrases and some core vocabulary, you’ll be able to make small talk with new friends, or show others that you’re sincerely interested in learning Japanese.

Just by incorporating a few of these phrases into daily life or conversation, you’ll soon be sure to hear nihongo ga jouzu desu ne! (日本語が上手ですね ) — You’re good at speaking Japanese!

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

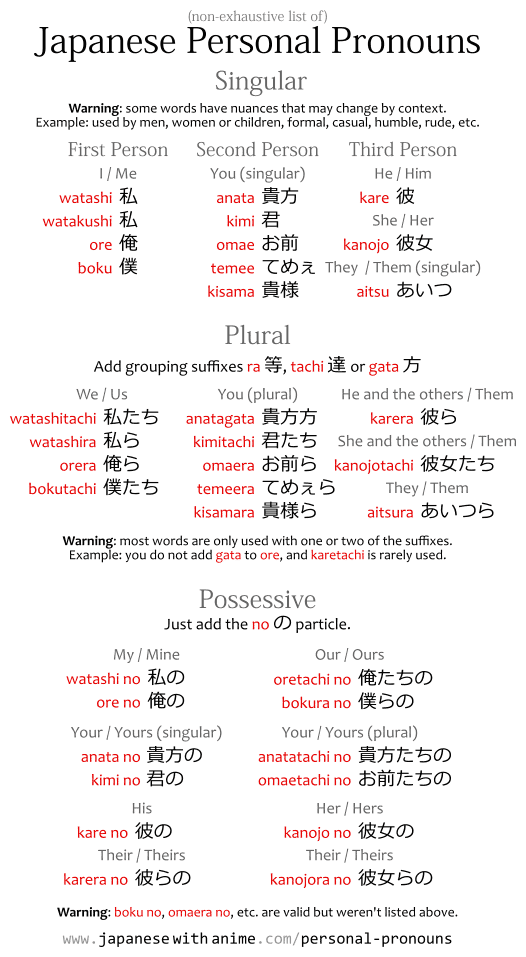

For reference, the pronouns of the Japanese language, and the posts which talked about them.

- Personal Pronouns

- First Person

- Second Person

- Third Person

- «It»

- Demonstrative Pronouns

- This, That, What

- Here, There, Where

- Plural Pronouns

- Object Pronouns

- Possessive Pronouns

- Personal Pronouns Chart

Personal Pronouns

First Person Pronouns

The following words can be used to say «I» in Japanese:

- watashi 私

- boku 僕

- ore 俺

- ore-sama 俺様 (anime trope, not used seriously.)

The above are the most common, but there are other first pronouns too.

Second Person Pronouns

The following words can be used to say «you» in Japanese:

- anata あなた

- kimi 君

- omae お前

- temee てめぇ

- kisama 貴様

There are immense differences between the words above.

Sometimes kono この means «you» when swearing. See kono yarou この野郎.

Third Person Pronouns

The following word can be used to say «he» in Japanese:

- kare 彼

And this is how you’d say «she» in Japanese:

- kanojo 彼女

Besides the above, the pronoun aitsu あいつ is sometimes used with a meaning similar to «he.»

The following demonstrating pronouns mean «this person,» «that person,» but can be understood as «me,» «you,» «»he,» or «she» depending on context.

- kono hito, sono hito, ano hito このひと, そのひと, あのひと

- kono ko, sono ko, ano ko この子, その子, あの子

- kocchi, socchi, acchi こっち, そっち, あっち

- kochira, sochira, achira こちら, そちら, あちら

- konata, sonata, anata こなた, そなた, あなた

- This anata means «he» and it’s archaic.

- The modern anata means «you» instead.

«It»

There’s no Japanese equivalent for the pronoun «it.» See the article «It» in Japanese for examples of how the functions of «it» in English translate to Japanese.

Demonstrative Pronouns

This, that, here, there, etc. in Japanese are expressed through the kosoado kotoba.

This, That, What

To say the nouns «this,» «that,» and «what» in Japanese:

- kore これ

- sore それ

- are あれ

- dore どれ

To say the adjectives «this,» «that,» and «what» in Japanese:

- kono この

- sono その

- ano あの

- dono どの

There are certain Japanese words like kou こう, konna こんあ, kochira こちら, and others. that also mean «this,» «that,» and «what,» each with a different nuance. See kosoado kotoba for details.

Here, There, Where

To say «this,» «there,» and «where» in Japanese:

- koko ここ

- soko そこ

- asoko あそこ

- doko どこ

Plural Pronouns

In Japanese, plurals don’t work the same way they do in English. In particular, Japanese has the so-called pluralizing suffixes tachi たち and ra ら, which can be combined with pronouns to form plural pronouns.

To say «we» in Japanese:

- watashitachi 私たち

- bokura 僕ら, bokutachi 僕達

- orera 俺ら, oretachi 俺達

To say «they» in Japanese:

- karera 彼ら

They. (he and the others) - kanojotachi 彼女たち

They. (she and the others)

To say «these» and «those» in Japanese:

- korera これら

- sorera それら

Object Pronouns

There are no words for «me,» «us,» «him,» «her,» and «them» in Japanese. There’s no distinction between subject pronouns and object pronouns in Japanese.

The only difference is in the usage of particles. This has been explained in simple sentences in Japanese. For example:

- watashi ga kare wo koroshita 私が彼を殺した

I killed him. - kare ga watashi wo koroshita 彼が私を殺した

He killed me.

Possessive Pronouns

There are no words for «my,» «his,» «her,» «their» in Japanese. There are no words for «mine,» «hers,» and «theirs» either.

Instead, the no の particle is used together with a pronoun to express what it possesses. For example:

- ore no kane 俺の金

My money. - anata no yume あなたの夢

Your dream. - kare no nozomi 彼の望み

His wish. - kanojotachi no kimochi

彼女たちの気持ち

Their feelings.

Personal Pronouns Chart

For reference, a chart with the personal pronouns: