The

words in an English sentence are arranged in a certain order which is

fixed for every type of sentence and is, therefore, meaningful. There

exist two ways of arranging words—direct order and inverted order.

Word

order fulfils various functions. The two main functions of word order

are grammatical and communicative. The essence of the grammatical

principle lies in the fact that the sentence position of an element

is determined by its syntactic function. The

communicative

principle manifests itself in that the sentence position of an

element varies depending on its communicative value.

Direct

word Order

The

most common pattern for the arrangement of the main parts in a

declarative sentence is Subject-Predicate-(Object), which is called

direct word order.

I

promise to respect your wishes.

Direct

word order is also employed in pronominal questions to the subject or

its attribute.

Who

told you where I was?

Direct

word order allows of a few variations in the fixed pattern, but only

for the secondary parts.

End—Focus

and End-Weight

Inappropriate

word order may lead to incoherence, clumsy style and lack of clarity.

So when you are deciding in which order to place the ideas in a

sentence, there are two useful guiding principles to remember:

-

End-focus:

the new or most important idea in a piece of information should be

placed towards the end, where in speech nuclear stress normally

falls. A sentence is generally more effective (especially in

writing) if the main point is saved up to the end.

Babies

prefer sleeping on their back.

-

End-weight:

the more “weighty” part(s) of a sentence should be placed

towards the end. Otherwise the sentence may sound awkward and

unbalanced. The “weight” of an element can be defined in terms

of length(e.g. number of syllables) or in terms of grammatical

complexity (number of modifiers). Structures with introductory it

and there, for instance, allow to avoid having a long subject, and

to put what you are taking about in a more prominent position at the

end of the sentence.

It

becomes hard for a child to develop a sense of identity. There is

grief in his face and reproach at the injustice of it all.

Connected

with the principle of end-weight in English is the feeling that the

predicate of a sentence should be longer or grammatically more

complex than the subject. This helps to explain why English native

speakers tend to avoid predicates consisting of just a single

intransitive verb. Instead of saying Mary sang , they would probably

prefer to say Mary sang a song , filling the object position with a

noun phrase which adds little information but helps to give more

weight to the predicate.

For

such a purpose English often uses a general verb( such as have, take,

give and do ) followed by an abstract noun phrase:

He

is having a swim.—-He is swimming.

He

took a rest.——He rested.

He

does little work.—-He works little.

The

sentences on the left are more idiomatic than on the right and they

contribute to the impression of fluency in English given by a foreign

user.

Order

and Emphasis

English

grammar has quite a number of sentence processes which help to

arrange the message for the right order and the right emphasis.

Because of the principle of end-focus and end- weight, the final

position in a sentence or clause is, in neutral circumstances, the

most important.

But

the first position is also important for communication, because it is

the starting point for what the speaker wants to say: it is (so to

speak) the part of the sentence which is familiar territory in which

the hearer gets his bearings. Therefore the first element in a

sentence or clause is called the TOPIC (or THEME). In most

statements, the topic is the subject of the sentence.

Instead

of the subject, you may make another element the topic by moving it

to the front of the sentence( fronted topic). This shift, which is

called fronting, gives the element a kind of psychological

prominence, and has three different effects:

-

In

informal conversation it is quite common for a speaker to front an

element(particularly a complement) and give it nuclear stress:

An

utter fool I felt, too. (topic-complement).

Excellent

food the serve here. (topic-object).

-

Fronting

also helps to point dramatically to a contrast between two things

mentioned in the neighbouring sentences or clauses, which often have

parallel structure:

Rich

I may be, but that doesn’t mean I am happy. (topic-complement).

His

face I am not fond of, but his character I despise.(topic-object)

Willingly

he’ll never do it, he’ll have to be forced. (topic-adverbial of

manner)

-

The

word this or these is often present in the fronted topic, showing

that it contains given information. This type of fronting is found

in more formal, especially written English and serves the function

of linking the sentence to the previous text.

This

subject we have examined in an earlier chapter, and need not

reconsider (topic-object)

Besides

fronting there are other ways of giving prominence to this or that

part of the sentence.

*cleft

sentences (it-type)

The

cleft sentence construction with emphatic it is useful for putting

focus (usually for contrast)on a particular part of a sentence

expressed by a noun (group) ,a prepositional phrase, and an adverb of

time or place, or even by a clause.

It

was from France that she first heard the news.

Perhaps

it’s because he’s a misfit that I get along with him.

*cleft

sentences(wh-type)

What

he’s done is –spoil the whole thing.

—to

spoil the whole thing.

—spoilt

the whole thing.

Wh-clefts

can also be used to highlight a subject complement. Instead of Jean

and Bob are stingy, we can say: What Jean and Bob are is stingy! This

pattern is used when we want to express our opinion of something or

somebody.

What

we want is to see the child in pursuit of knowledge, and not

knowledge in pursuit of the child. (G.B.Shaw)

*Wh-clauses

with demonstratives

It

is a common type of sentence in English which is similar to wh-cleft

sentences.

This

is how you start the engine.

*Auxiliary

DO

You

can emphasize a statement by putting do, does , or did in front of

the base form of the verb.

I

do feel sorry for Roger.

But

it goes move.(G.Galilei).

*The

passive

Passive

constructions vary the way information is given in a sentence. The

passive can be used:

—for

end-focus

Who

makes these chairs?—They’re made by Ercol.

—for

end-weight where the subject is a clause

I

was astonished that he was prepared to give me a job. (Better than:

That he was prepared to give me a job astonished me.)

—for

emphasis on what comes first

All

roads to the north have been blocked by snow.

The

other common pattern of word order is the inversion. There are 2

types of inversion:

-

Subject-verb

inversion

Brightly

shone the moon that night…

-

Subject-operator/

auxiliary inversion

Seldom

can there have been such a happy meeting.

Sometimes

the inversion may be taken as a normal order of words in

constructions with special communicative value, and is devoid of any

special colouring.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Можно ли использовать вопросительный порядок слов в утвердительных предложениях? Как построить предложение, если в нем нет подлежащего? Об этих и других нюансах читайте в нашей статье.

Прямой порядок слов в английских предложениях

Утвердительные предложения

В английском языке основной порядок слов можно описать формулой SVO: subject – verb – object (подлежащее – сказуемое – дополнение).

Mary reads many books. — Мэри читает много книг.

Подлежащее — это существительное или местоимение, которое стоит в начале предложения (кто? — Mary).

Сказуемое — это глагол, который стоит после подлежащего (что делает? — reads).

Дополнение — это существительное или местоимение, которое стоит после глагола (что? — books).

В английском отсутствуют падежи, поэтому необходимо строго соблюдать основной порядок слов, так как часто это единственное, что указывает на связь между словами.

| Подлежащее | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|

| My mum | loves | soap operas. | Моя мама любит мыльные оперы. |

| Sally | found | her keys. | Салли нашла свои ключи. |

| I | remember | you. | Я помню тебя. |

Глагол to be в утвердительных предложениях

Как правило, английское предложение не обходится без сказуемого, выраженного глаголом. Так как в русском можно построить предложение без глагола, мы часто забываем о нем в английском. Например:

Mary is a teacher. — Мэри — учительница. (Мэри является учительницей.)

I’m scared. — Мне страшно. (Я являюсь напуганной.)

Life is unfair. — Жизнь несправедлива. (Жизнь является несправедливой.)

My younger brother is ten years old. — Моему младшему брату десять лет. (Моему младшему брату есть десять лет.)

His friends are from Spain. — Его друзья из Испании. (Его друзья происходят из Испании.)

The vase is on the table. — Ваза на столе. (Ваза находится/стоит на столе.)

Подведем итог, глагол to be в переводе на русский может означать:

- быть/есть/являться;

- находиться / пребывать (в каком-то месте или состоянии);

- существовать;

- происходить (из какой-то местности).

Если вы не уверены, нужен ли to be в вашем предложении в настоящем времени, то переведите предложение в прошедшее время: я на работе — я была на работе. Если в прошедшем времени появляется глагол-связка, то и в настоящем он необходим.

Предложения с there is / there are

Когда мы хотим сказать, что что-то где-то есть или чего-то где-то нет, то нам нужно придерживаться конструкции there + to be в начале предложения.

There is grass in the yard, there is wood on the grass. — На дворе — трава, на траве — дрова.

Если в таких типах предложений мы не используем конструкцию there is / there are, то по-английски подобные предложения будут звучать менее естественно:

There are a lot of people in the room. — В комнате много людей. (естественно)

A lot of people are in the room. — Много людей находится в комнате. (менее естественно)

Обратите внимание, предложения с there is / there are, как правило, переводятся на русский с конца предложения.

Еще конструкция there is / there are нужна, чтобы соблюсти основной порядок слов — SVO (подлежащее – сказуемое – дополнение):

| Подлежащее | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|

| There | is | too much sugar in my tea. | В моем чае слишком много сахара. |

Более подробно о конструкции there is / there are можно прочитать в статье «Грамматика английского языка для начинающих, часть 3».

Местоимение it

Мы, как носители русского языка, в английских предложениях забываем не только про сказуемое, но и про подлежащее. Особенно сложно понять, как перевести на английский подобные предложения: Темнеет. Пора вставать. Приятно было пообщаться. В английском языке во всех этих предложениях должно стоять подлежащее, роль которого будет играть вводное местоимение it. Особенно важно его не забыть, если мы говорим о погоде.

It’s getting dark. — Темнеет.

It’s time to get up. — Пора вставать.

It was nice to talk to you. — Приятно было пообщаться.

Хотите научиться грамотно говорить по-английски? Тогда записывайтесь на курс практической грамматики.

Отрицательные предложения

Если предложение отрицательное, то мы ставим отрицательную частицу not после:

- вспомогательного глагола (auxiliary verb);

- модального глагола (modal verb).

| Подлежащее | Вспомогательный/Модальный глагол | Частица not | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sally | has | not | found | her keys. | Салли не нашла свои ключи. |

| My mum | does | not | love | soap operas. | Моя мама не любит мыльные оперы. |

| He | could | not | save | his reputation. | Он не мог спасти свою репутацию |

| I | will | not | be | yours. | Я не буду твоей. |

Если в предложении единственный глагол — to be, то ставим not после него.

| Подлежащее | Глагол to be | Частица not | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peter | is | not | an engineer. | Питер не инженер. |

| I | was | not | at work yesterday. | Я не была вчера на работе. |

| Her friends | were | not | polite enough. | Ее друзья были недостаточно вежливы. |

Порядок слов в вопросах

Для начала скажем, что вопросы бывают двух основных типов:

- закрытые вопросы (вопросы с ответом «да/нет»);

- открытые вопросы (вопросы, на которые можно дать развернутый ответ).

Закрытые вопросы

Чтобы построить вопрос «да/нет», нужно поставить модальный или вспомогательный глагол в начало предложения. Получится следующая структура: вспомогательный/модальный глагол – подлежащее – сказуемое. Следующие примеры вам помогут понять, как утвердительное предложение преобразовать в вопросительное.

She goes to the gym on Mondays. — Она ходит в зал по понедельникам.

Does she go to the gym on Mondays? — Ходит ли она в зал по понедельникам?

He can speak English fluently. — Он умеет бегло говорить по-английски.

Can he speak English fluently? — Умеет ли он бегло говорить по-английски?

Simon has always loved Katy. — Саймон всегда любил Кэти.

Has Simon always loved Katy? — Всегда ли Саймон любил Кэти?

Обратите внимание! Если в предложении есть только глагол to be, то в Present Simple и Past Simple мы перенесем его в начало предложения.

She was at home all day yesterday. — Она была дома весь день.

Was she at home all day yesterday? — Она была дома весь день?

They’re tired. — Они устали.

Are they tired? — Они устали?

Открытые вопросы

В вопросах открытого типа порядок слов такой же, только в начало предложения необходимо добавить вопросительное слово. Тогда структура предложения будет следующая: вопросительное слово – вспомогательный/модальный глагол – подлежащее – сказуемое.

Перечислим вопросительные слова: what (что?, какой?), who (кто?), where (где?, куда?), why (почему?, зачем?), how (как?), when (когда?), which (который?), whose (чей?), whom (кого?, кому?).

He was at work on Monday. — В понедельник он весь день был на работе.

Where was he on Monday? — Где он был в понедельник?

She went to the cinema yesterday. — Она вчера ходила в кино.

Where did she go yesterday? — Куда она вчера ходила?

My father watches Netflix every day. — Мой отец каждый день смотрит Netflix.

How often does your father watch Netflix? — Как часто твой отец смотрит Netflix?

Вопросы к подлежащему

В английском есть такой тип вопросов, как вопросы к подлежащему. У них порядок слов такой же, как и в утвердительных предложениях, только в начале будет стоять вопросительное слово вместо подлежащего. Сравните:

Who do you love? — Кого ты любишь? (подлежащее you)

Who loves you? — Кто тебя любит? (подлежащее who)

Whose phone did she find two days ago? — Чей телефон она вчера нашла? (подлежащее she)

Whose phone is ringing? — Чей телефон звонит? (подлежащее whose phone)

What have you done? — Что ты наделал? (подлежащее you)

What happened? — Что случилось? (подлежащее what)

Обратите внимание! После вопросительных слов who и what необходимо использовать глагол в единственном числе.

Who lives in this mansion? — Кто живет в этом особняке?

What makes us human? — Что делает нас людьми?

Косвенные вопросы

Если вам нужно что-то узнать и вы хотите звучать более вежливо, то можете начать свой вопрос с таких фраз, как: Could you tell me… ? (Можете подсказать… ?), Can you please help… ? (Можете помочь… ?) Далее задавайте вопрос, но используйте прямой порядок слов.

Could you tell me where is the post office is? — Не могли бы вы мне подсказать, где находится почта?

Do you know what time does the store opens? — Вы знаете, во сколько открывается магазин?

Если в косвенный вопрос мы трансформируем вопрос типа «да/нет», то перед вопросительной частью нам понадобится частица «ли» — if или whether.

Do you like action films? — Тебе нравятся боевики?

I wonder if/whether you like action films. — Мне интересно узнать, нравятся ли тебе экшн-фильмы.

Другие члены предложения

Прилагательное в английском стоит перед существительным, а наречие обычно — в конце предложения.

Grace Kelly was a beautiful woman. — Грейс Келли была красивой женщиной.

Andy reads well. — Энди хорошо читает.

Обстоятельство, как правило, стоит в конце предложения. Оно отвечает на вопросы как?, где?, куда?, почему?, когда?

There was no rain last summer. — Прошлым летом не было дождя.

The town hall is in the city center. — Администрация находится в центре города.

Если в предложении несколько обстоятельств, то их надо ставить в следующем порядке:

| Подлежащее + сказуемое | Обстоятельство (как?) | Обстоятельство (где?) | Обстоятельство (когда?) | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fergie didn’t perform | very well | at the concert | two years ago. | Ферги не очень хорошо выступила на концерте два года назад. |

Чтобы подчеркнуть, когда или где что-то случилось, мы можем поставить обстоятельство места или времени в начало предложения:

Last Christmas I gave you my heart. But the very next day you gave it away. This year, to save me from tears, I’ll give it to someone special. — Прошлым Рождеством я подарил тебе свое сердце. Но уже на следующий день ты отдала его обратно. В этом году, чтобы больше не горевать, я подарю его кому-нибудь другому.

Если вы хотите преодолеть языковой барьер и начать свободно общаться с иностранцами, записывайтесь на разговорный курс английского.

Надеемся, эта статья была вам полезной и вы разобрались, как строить предложения в английском языке. Предлагаем пройти небольшой тест для закрепления темы.

Тест по теме «Порядок слов в английском предложении, часть 1»

© 2023 englex.ru, копирование материалов возможно только при указании прямой активной ссылки на первоисточник.

1. What is Word Order?

Word order is important: it’s what makes your sentences make sense! So, proper word order is an essential part of writing and speaking—when we put words in the wrong order, the result is a confusing, unclear, and an incorrect sentence.

2.Examples of Word Order

Here are some examples of words put into the correct and incorrect order:

I have 2 brothers and 2 sisters at home. CORRECT

2 brothers and 2 sisters have I at home. INCORRECT

I am in middle school. CORRECT

In middle school I am. INCORRECT

How are you today? CORRECT

You are how today? INCORRECT

As you can see, it’s usually easy to see whether or not your words are in the correct order. When words are out of order, they stand out, and usually change the meaning of a sentence or make it hard to understand.

3. Types of Word Order

In English, we follow one main pattern for normal sentences and one main pattern for sentences that ask a question.

a. Standard Word Order

A sentence’s standard word order is Subject + Verb + Object (SVO). Remember, the subject is what a sentence is about; so, it comes first. For example:

The dog (subject) + eats (verb) + popcorn (object).

The subject comes first in a sentence because it makes our meaning clear when writing and speaking. Then, the verb comes after the subject, and the object comes after the verb; and that’s the most common word order. Otherwise, a sentence doesn’t make sense, like this:

Eats popcorn the dog. (verb + object + subject)

Popcorn the dog eats. (object + subject + verb)

B. Questions

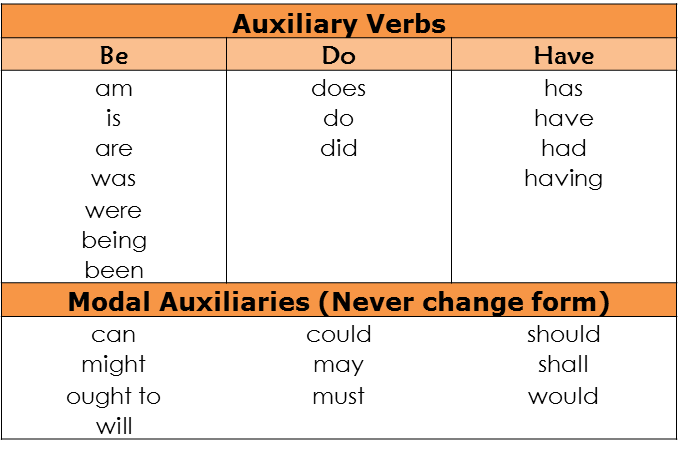

When asking a question, we follow the order auxiliary verb/modal auxiliary + subject + verb (ASV). Auxiliary verbs and modal auxiliaries share meaning or function, many which are forms of the verb “to be.” Auxiliary verbs can change form, but modal auxiliaries don’t. Here’s a chart to help you:

As said, questions follow the form ASV; or, if they have an object, ASVO. Here are some examples:

Can he cook? “Can” (auxiliary) “he” (subject) “cook” (verb)

Does your dog like popcorn? “Does” (A) “your dog” (S) “like” (V) “popcorn” (O)

Are you burning the popcorn? “Are” (A) “you” (S) “burning” (V) “popcorn” (O)

4. Parts of Word Order

While almost sentences need to follow the basic SVO word order, we add other words, like indirect objects and modifiers, to make them more detailed.

a. Indirect Objects

When we add an indirect object, a sentence will follow a slightly different order. Indirect objects always come between the verb and the object, following the pattern SVIO, like this:

I fed the dog some popcorn.

This sentence has “I” (subject) “fed” (verb) “dog” (indirect object) “popcorn” (direct object).

b. Prepositional Phrases

Prepositional phrases also have special positions in sentences. When we use the prepositions like “to” or “for,” then the indirect object becomes part of a prepositional phrase, and follows the order SVOP, like this:

I fed some popcorn to the dog.

Other prepositional phrases, determining time and location, can go at either the beginning or the end of a sentence:

He ate popcorn at the fair. -Or- At the fair he ate popcorn.

In the morning I will go home. I will go home in the morning.

c. Adverbs

Adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs, adding things like time, manner, degree; and often end in ly, like “slowly,” “recently,” “nearly,” and so on. As a rule, an adverb (or any modifier) should be as close as possible to the thing it is modifying. But, adverbs are special because they can usually be placed in more than one spot in the sentence and are still correct. So, there are rules about their placement, but also many exceptions.

In general, when modifying an adjective or adverb, an adverb should go before the word it modifies:

The dog was extremely hungry. CORRECT adverb modifies “hungry”

Extremely, the dog was hungry. INCORRECT misplaced adverb

The extremely dog was hungry. INCORRECT misplaced adverb

The dog was hungry extremely. INCORRECT misplaced adverb

As you can see, the word “extremely” only makes sense just before the adjective “hungry.” In this situation, the adverb can only go in one place.

When modifying a verb, an adverb should generally go right after the word it modifies, as in the first sentence below. BUT, these other uses are also correct, though they may not be the best:

The dog ran quickly to the fair. CORRECT * BEST POSITION

Quickly the dog ran to the fair. CORRECT

The dog quickly ran to the fair. CORRECT

The dog ran to the fair quickly. CORRECT

For adverbs expressing frequency (how often something happens) the adverb goes directly after the subject:

The dog always eats popcorn.

He never runs slowly.

I rarely see him.

Adverbs expressing time (when something happens) can go at either the beginning or of the end of the sentence, depending what’s important about the sentence. If the time isn’t very important, then it goes at the beginning of the sentence, but if you want to emphasize the time, then the adverb goes at the end of the sentence:

Now the dog wants popcorn. Emphasis on “the dog wants popcorn”

The dog wants popcorn now. Emphasis on “now”

5. How to Use Avoid Mistakes with Word Order

Aside from following the proper SVO pattern, it’s important to write and speak in the way that is the least confusing and the most clear. If you make mistakes with your word order, then your sentences won’t make sense. Basically, if a sentence is hard to understand, then it isn’t correct. Here are a few key things to remember:

- The subject is what a sentence is about, so it should come first.

- A modifier (like an adverb) should generally go as close as possible to the thing it is modifying.

- Indirect objects can change the word order from SVO to SVIO

- Prepositional phrases have special positions in sentences

Finally, here’s an easy tip: when writing, always reread your sentences out loud to make sure that the words are in the proper order—it is usually pretty easy to hear! If a sentence is clear, then you should only need to read it once to understand it.

Welcome to the ELB Guide to English Word Order and Sentence Structure. This article provides a complete introduction to sentence structure, parts of speech and different sentence types, adapted from the bestselling grammar guide, Word Order in English Sentences. I’ve prepared this in conjunction with a short 3-video course, currently in editing, to help share the lessons of the book to a wider audience.

You can use the headings below to quickly navigate the topics:

- Different Ways to Analyse English Structure

- Subject-Verb-Object: Sentence Patterns

- Adding Additional Information: Objects, Prepositional Phrases and Time

- Alternative Sentence Patterns: Different Sentence Types

- Parts of Speech

- Nouns, Determiners and Adjectives

- Pronouns

- Verbs

- Phrasal Verbs

- Adverbs

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

- Clauses, Simple, Compound and Complex Sentences

- Simple Sentences

- Compound Sentences

- Complex Sentences

Different Ways to Analyse English Structure

There are lots of ways to break down sentences, for different purposes. This article covers the systems I’ve found help my students understand and form accurate sentences, but note these are not the only ways to explore English grammar.

I take three approaches to introducing English grammar:

- Studying overall patterns, grouping sentence components by their broad function (subject, verb, object, etc.)

- Studying different word types (the parts of speech), how their phrases are formed and their places in sentences

- Studying groupings of phrases and clauses, and how they connect in simple, compound and complex sentences

Subject-Verb-Object: Sentence Patterns

English belongs to a group of just under half the world’s languages which follows a SUBJECT – VERB – OBJECT order. This is the starting point for all our basic clauses (groups of words that form a complete grammatical idea). A standard declarative clause should include, in this order:

- Subject – who or what is doing the action (or has a condition demonstrated, for state verbs), e.g. a man, the church, two beagles

- Verb – what is done or what condition is discussed, e.g. to do, to talk, to be, to feel

- Additional information – everything else!

In the correct order, a subject and verb can communicate ideas with immediate sense with as little as two or three words.

- Gemma studies.

- It is hot.

Why does this order matter? We know what the grammatical units are because of their position in the sentence. We give words their position based on the function we want them to convey. If we change the order, we change the functioning of the sentence.

- Studies Gemma

- Hot is it

With the verb first, these ideas don’t make immediate sense and, depending on the verbs, may suggest to English speakers a subject is missing or a question is being formed with missing components.

- The alien studies Gemma. (uh oh!)

- Hot, is it? (a tag question)

If we don’t take those extra steps to complete the idea, though, the reversed order doesn’t work. With “studies Gemma”, we couldn’t easily say if we’re missing a subject, if studies is a verb or noun, or if it’s merely the wrong order.

The point being: using expected patterns immediately communicates what we want to say, without confusion.

Adding Additional Information: Objects, Prepositional Phrases and Time

Understanding this basic pattern is useful for when we start breaking down more complicated sentences; you might have longer phrases in place of the subject or verb, but they should still use this order.

| Subject | Verb |

| Gemma | studies. |

| A group of happy people | have been quickly walking. |

After subjects and verbs, we can follow with different information. The other key components of sentence patterns are:

- Direct Object: directly affected by the verb (comes after verb)

- Indirect Objects: indirectly affected by the verb (typically comes between the verb and a direct object)

- Prepositional phrases: noun phrases providing extra information connected by prepositions, usually following any objects

- Time: describing when, usually coming last

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object | Preposition Phrase | Time |

| Gemma | studied | English | in the library | last week. | |

| Harold | gave | his friend | a new book | for her birthday | yesterday. |

The individual grammatical components can get more complicated, but that basic pattern stays the same.

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object | Preposition Phrase | Time |

| Our favourite student Gemma | has been studying | the structure of English | in the massive new library | for what feels like eons. | |

| Harold the butcher’s son | will have given | the daughter of the clockmaker | an expensive new book | for her coming-of-age festival | by this time next week. |

The phrases making up each grammatical unit follow their own, more specific rules for ordering words (covered below), but overall continue to fit into this same basic order of components:

Subject – Verb – Indirect Object – Direct Object – Prepositional Phrase – Time

Alternative Sentence Patterns: Different Sentence Types

Subject-Verb-Object is a starting point that covers positive, declarative sentences. These are the most common clauses in English, used to describe factual events/conditions. The type of verb can also make a difference to these patterns, as we have action/doing verbs (for activities/events) and linking/being verbs (for conditions/states/feelings).

Here’s the basic patterns we’ve already looked at:

- Subject + Action Verb – Gemma studies.

- Subject + Action Verb + Object – Gemma studies English.

- Subject + Action Verb + Indirect Object + Direct Object – Gemma gave Paul a book.

We might also complete a sentence with an adverb, instead of an object:

- Subject + Action Verb + Adverb – Gemma studies hard.

When we use linking verbs for states, senses, conditions, and other occurrences, the verb is followed by noun or adjective phrases which define the subject.

- Subject + Linking Verb + Noun Phrase – Gemma is a student.

- Subject + Linking Verb + Adjective Phrase – Gemma is very wise.

These patterns all form positive, declarative sentences. Another pattern to note is Questions, or interrogative sentences, where the first verb comes before the subject. This is done by adding an auxiliary verb (do/did) for the past simple and present simple, or moving the auxiliary verb forward if we already have one (to be for continuous tense, or to have for perfect tenses, or the modal verbs):

- Gemma studies English. –> Does Gemma study English?

- Gemma is very wise. –> Is Gemma very wise?

For more information on questions, see the section on verbs.

Finally, we can also form imperative sentences, when giving commands, which do not need a subject.

- Study English!

(Note it is also possible to form exclamatory sentences, which express heightened emotion, but these depend more on context and punctuation than grammatical components.)

Parts of Speech

General patterns offer overall structures for English sentences, while the broad grammatical units are formed of individual words and phrases. In English, we define different word types as parts of speech. Exactly how many we have depends on how people break them down. Here, we’ll look at nine, each of which is explained below. Either keep reading or click on the word types to go to the sections about their word order rules.

- Nouns – naming words that define someone or something, e.g. car, woman, cat

- Pronouns – words we use in place of nouns, e.g. he, she, it

- Verbs – doing or being words, describing an action, state or experience e.g. run, talk, be

- Adjectives – words that describe nouns or pronouns, e.g. cheerful, smelly, loud

- Adverbs – words that describe verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, sentences themselves – anything other nouns and pronouns, basically, e.g. quickly, curiously, weirdly

- Determiners – words that tell us about a noun’s quantity or if it’s specific, e.g. a, the, many

- Prepositions – words that show noun or noun phrase positions and relationships, e.g. above, behind, in, on

- Conjunctions – words that connect words, phrases or clauses e.g. and, but

- Interjections – words that express a single emotion, e.g. Hey! Ah! Oof!

For more articles and exercises on all of these, be sure to also check out ELB’s archive covering parts of speech.

Noun Phrases, Determiners and Adjectives

Subjects and objects are likely to be nouns or noun phrases, describing things. So sentences usually to start with a noun phrase followed by a verb.

- Nina ate.

However, a noun phrase may be formed of more than word.

We define nouns with determiners. These always come first in a noun phrase. They can be articles (a/an/the – telling us if the noun is specific or not), or can refer to quantities (e.g. some, much, many):

- a dog (one of many)

- the dog in the park

- many dogs

After determiners, we use adjectives to add description to the noun:

- The fluffy dog.

You can have multiple adjectives in a phrase, with orders of their own. You can check out my other article for a full analysis of adjective word order, considering type, material, size and other qualities – but a starting rule is that less definite adjectives go first – more specific qualities go last. Lead with things that are more opinion-based, finish with factual elements:

- It is a beautiful wooden chair. (opinion before fact.)

We can also form compound nouns, where more than one noun is used, e.g. “cat food”, “exam paper”. The earlier nouns describe the final noun: “cat food” is a type of food, for cats; an “exam paper” is a specific paper. With compound nouns you have a core noun (the last noun), what the thing is, and any nouns before it describe what type. So – description first, the actual thing last.

Finally, noun phrases may also include conjunctions joining lists of adjectives or nouns. These usually come between the last two items in a list, either between two nouns or noun phrases, or between the last two adjectives in a list:

- Julia and Lenny laughed all day.

- a long, quick and dangerous snake

Pronouns

We use pronouns in the place of nouns or noun phrases. For the most part, these fit into sentences the same way as nouns, in subject or object positions, but don’t form phrases, as they replace a whole noun phrase – so don’t use describing words or determiners with pronouns.

Pronouns suggest we already know what is being discussed. Their positions are the same as nouns, except with phrasal verbs, where pronouns often have fixed positions, between a verb and a particle (see below).

Verbs

Verb phrases should directly follow the subject, so in terms of parts of speech a verb should follow a noun phrase, without connecting words.

As with nouns and noun phrases, multiple words may make up the verb component. Verb phrases depend on your tenses, which follow particular forms – e.g. simple, continuous, perfect and perfect continuous. The specifics of verb phrases are covered elsewhere, for example the full verb forms for the tenses are available in The English Tenses Practical Grammar Guide. But in terms of structure, with standard, declarative clauses the ordering of verb phrases should not change from their typical tense forms. Other parts of speech do not interrupt verb phrases, except for adverbs.

The times that verb phrases do change their structure are for Questions and Negatives.

With Yes/No Questions, the first verb of a verb phrase comes before the subject.

- Neil is running. –> Is Neil running?

This requires an auxiliary verb – a verb that creates a grammatical function. Many tenses already have an auxiliary verb – to be in continuous tenses (“is running”), or to have in perfect tenses (have done). For these, to make a question we move that auxiliary in front of the subject. With the past and present simple tenses, for questions, we add do or did, and put that before the subject.

- Neil ran. –> Did Neil run?

We can also have questions that use question words, asking for information (who, what, when, where, why, which, how), which can include noun phrases. For these, the question word and any noun phrases it includes comes before the verb.

- Where did Neil Run?

- At what time of day did Neil Run?

To form negative statements, we add not after the first verb, if there is already an auxiliary, or if there is not auxiliary we add do not or did not first.

- Neil is running. –> Neil is not

- Neil ran. Neil did not

The not stays behind the subject with negative questions, unless we use contractions, where not is combined with the verb and shares its position.

- Is Neil not running?

- Did Neil not run?

- Didn’t Neil run?

Phrasal Verbs

Phrasal verbs are multi-word verbs, often with very specific meanings. They include at least a verb and a particle, which usually looks like a preposition but functions as part of the verb, e.g. “turn up“, “keep on“, “pass up“.

You can keep phrasal verb phrases all together, as with other verb phrases, but they are more flexible, as you can also move the particle after an object.

- Turn up the radio. / Turn the radio up.

This doesn’t affect the meaning, and there’s no real right or wrong here – except with pronouns. When using pronouns, the particle mostly comes after the object:

- Turn it up. NOT Turn up it.

For more on phrasal verbs, check out the ELB phrasal verbs master list.

Adverbs

Adverbs and adverbial phrases are really tricky in English word order because they can describe anything other than nouns. Their positions can be flexible and they appear in unexpected places. You might find them in the middle of verb phrases – or almost anywhere else in a sentence.

There are many different types of adverbs, with different purposes, which are usually broken down into degree, manner, frequency, place and time (and sometimes a few others). They may be single words or phrases. Adverbs and adverb phrases can be found either at the start of a clause, the end of a clause, or in a middle position, either directly before or after the word they modify.

- Graciously, Claire accepted the award for best student. (beginning position)

- Claire graciously accepted the award for best student. (middle position)

- Claire accepted the award for best student graciously. (end position)

Not all adverbs can go in all positions. This depends on which type they are, or specific adverb rules. One general tip, however, is that time, as with the general sentence patterns, should usually come last in a clause, or at the very front if moved for emphasis.

With verb phrases, adverbs often either follow the whole phrase or come before or after the first verb in a phrase (there are regional variations here).

For multiple adverbs, there can be a hierarchy in a similar way to adjectives, but you shouldn’t often use many adverbs together.

The largest section of the Word Order book discusses adverbs, with exercises.

Prepositions

Prepositions are words that, generally, demonstrate relationships between noun phrases (e.g. by, on, above). They mostly come before a noun phrase, hence the name pre-position, and tend to stick with the noun phrase they describe, so move with the phrase.

- They found him [in the cupboard].

- [In the cupboard,] they found him.

In standard sentence structure, prepositional phrases often follow verbs or other noun phrases, but they may also be used for defining information within a noun phrases itself:

- [The dog in sunglasses] is drinking water.

Conjunctions

Conjunctions connect lists in noun phrases (see nouns) or connect clauses, meaning they are found between complete clauses. They can also come at the start of a sentence that begins with a subordinate clause, when clauses are rearranged (see below), but that’s beyond the standard word order we’re discussing here. There’s more information about this in the article on different sentence types.

As conjunctions connect clauses, they come outside our sentence and word type patterns – if we have two clauses following subject-verb-object, the conjunction comes between them:

|

Subject |

Verb |

Object |

Conjunction |

Subject |

Verb |

Object |

|

He |

washed |

the car |

while |

she |

ate |

a pie. |

Interjections

These are words used to show an emotion, usually something surprising or alarming, often as an interruption – so they can come anywhere! They don’t normally connect to other words, as they are either used to get attention or to cut off another thought.

- Hey! Do you want to go swimming?

- OH NO! I forgot my homework.

Clauses and Simple, Compound and Complex Sentences

While a phrase is any group of words that forms a single grammatical unit, a clause is when a group of words form a complete grammatical idea. This is possible when we follow the patterns at the start of this article, for example when we combine a subject and verb (or noun phrase and verb phrase).

A single clause can follow any of the patterns we’ve already discussed, using varieties of the word types covered; it can be as simple a two-word subject-verb combo, or it may include as many elements as you can think of:

- Eric sat.

- The boy spilt blue paint on Harriet in the classroom this morning.

As long as we have one main verb and one main subject, these are still single clauses. Complete with punctuation, such as a capital letter and full stop, and we have a complete sentence, a simple sentence. When we combine two or more clauses, we form compound or complex sentences, depending on the clauses relationships to each other. Each type is discussed below.

Simple Sentences

A sentence with one independent clause is what we call a simple sentence; it presents a single grammatically complete action, event or idea. But as we’ve seen, just because the sentence structure is called simple it does not mean the tenses, subjects or additional information are simple. It’s the presence of one main verb (or verb phrase) that keeps it simple.

Our additional information can include any number of objects, prepositional phrases and adverbials; and that subject and verb can be made up of long noun and verb phrases.

Compound Sentences

We use conjunctions to bring two or more clauses together to create a compound sentence. The clauses use the same basic order rules; just treat the conjunction as a new starting point. So after one block of subject-verb-object, we have a conjunction, then the next clause will use the same pattern, subject-verb-object.

- [Gemma worked hard] and [Paul copied her].

See conjunctions for another example.

A series of independent clauses can be put together this way, following the expected patterns, joined by conjunctions.

Compound sentences use co-ordinating conjunctions, such as and, but, for, yet, so, nor, and or, and do not connect the clauses in a dependent way. That means each clause makes sense on its own – if we removed the conjunction and created separate sentences, the overall meaning would remain the same.

With more than two clauses, you do not have to include conjunctions between each one, e.g. in a sequence of events:

- I walked into town, I visited the book shop and I bought a new textbook.

And when you have the same subject in multiple clauses, you don’t necessarily need to repeat it. This is worth noting, because you might see clauses with no immediate subject:

- [I walked into town], [visited the book shop] and [bought a new textbook].

Here, with “visited the book shop” and “bought a new textbook” we understand that the same subject applies, “I”. Similarly, when verb tenses are repeated, using the same auxiliary verb, you don’t have to repeat the auxiliary for every clause.

What about ordering the clauses? Independent clauses in compound sentences are often ordered according to time, when showing a listed sequence of actions (as in the example above), or they may be ordered to show cause and effect. When the timing is not important and we’re not showing cause and effect, the clauses of compound sentences can be moved around the conjunction flexibly. (Note: any shared elements such as the subject or auxiliary stay at the front.)

- Billy [owned a motorbike] and [liked to cook pasta].

- Billy [liked to cook pasta] and [owned a motorbike].

Complex Sentences

As well as independent clauses, we can have dependent clauses, which do not make complete sense on their own, and should be connected to an independent clause. While independent clauses can be formed of two words, the subject and verb, dependent clauses have an extra word that makes them incomplete – either a subordinating conjunction (e.g. because, when, since, if, after and although), or a relative pronoun, (e.g. that, who and which).

- Jim slept.

- While Jim slept,

Subordinating conjunctions and relative pronouns create, respectively, a subordinate clause or a relative clause, and both indicate the clause is dependent on more information to form a complete grammatical idea, to be provided by an independent clause:

- While Jim slept, the clowns surrounded his house.

In terms of structure, the order of dependent clauses doesn’t change from the patterns discussed before – the word that comes at the front makes all the difference. We typically connect independent clauses and dependent clauses in a similar way to compound sentences, with one full clause following another, though we can reverse the order for emphasis, or to present a more logical order.

- Although she liked the movie, she was frustrated by the journey home.

(Note: when a dependent clause is placed at the beginning of a sentence, we use a comma, instead of another conjunction, to connect it to the next clause.)

Relative clauses, those using relative pronouns (such as who, that or which), can also come in different positions, as they often add defining information to a noun or take the place of a noun phrase itself.

- The woman who stole all the cheese was never seen again.

- Whoever stole all the cheese is going to be caught one day.

In this example, the relative clause could be treated, in terms of position, in the same way as a noun phrase, taking the place of an object or the subject:

- We will catch whoever stole the cheese.

For more information on this, check out the ELB guide to simple, compound and complex sentences.

That’s the end of my introduction to sentence structure and word order, but as noted throughout this article there are plenty more articles on this website for further information. And if you want a full discussion of these topics be sure to check out the bestselling guide, Word Order in English Sentences, available in eBook on this site and from all major retailers in paperback format.

Get the Complete Word Order Guide

This article is expanded upon in the bestselling grammar guide, Word Order in English Sentences, available in eBook and paperback.

If you found this useful, check out the complete book for more.

English word order is strict and rather inflexible. As there are few endings in English that show person, number, case and tense, English relies on word order to show relationships between words in a sentence.

In Russian, we rely on word endings to tell us how words interact in a sentence. You probably remember the example that was made up by Academician L.V. Scherba in order to show the work of endings and suffixes in Russian. (No English translation for this example.) Everything we need to know about the interaction of the characters in this Russian sentence, we learn from the endings and suffixes.

English nouns do not have any case endings (only personal pronouns have some case endings), so it is mostly the word order that tells us where things are in a sentence, and how they interact. Compare:

The dog sees the cat.

The cat sees the dog.

The subject and the object in these sentences are completely the same in form. How do you know who sees whom? The rules of English word order tell us about it.

Word order patterns in English sentences

A sentence is a group of words containing a subject and a predicate and expressing a complete thought. Word order arranges separate words into sentences in a certain way and indicates where to find the subject, the predicate, and the other parts of the sentence. Word order and context help to identify the meanings of individual words.

English sentences are divided into declarative sentences (statements), interrogative sentences (questions), imperative sentences (commands, requests), and exclamatory sentences. Declarative sentences are the most common type of sentences. Word order in declarative sentences serves as a basis for word order in the other types of sentences.

The main minimal pattern of basic word order in English declarative sentences is SUBJECT + PREDICATE. Examples: Maria works. Time flies.

The most common pattern of basic word order in English declarative sentences is SUBJECT + PREDICATE + OBJECT, often called SUBJECT + VERB + OBJECT (SVO) in English linguistic sources. Examples: Tom writes stories. The dog sees the cat.

An ordinary declarative sentence containing all five parts of the sentence, for example, «Mike read an interesting story yesterday», has the following word order:

The subject is placed at the beginning of the sentence before the predicate; the predicate follows the subject; the object is placed after the predicate; the adverbial modifier is placed after the object (or after the verb if there is no object); the attribute (an adjective) is placed before its noun (attributes in the form of a noun with a preposition are placed after their nouns).

Verb type and word order

Word order after the verb usually depends on the type of verb (transitive verb, intransitive verb, linking verb). (Types of verbs are described in Verbs Glossary of Terms in the section Grammar.)

Transitive verbs

Transitive verbs require a direct object: Tom writes stories. Denis likes films. Anna bought a book. I saw him yesterday. (See Transitive and Intransitive Verbs in the section Miscellany.)

Some transitive verbs (e.g., bring, give, send, show, tell) are often followed by two objects: an indirect object and a direct object. For example: He gave me the key. She sent him a letter. Such sentences often have the following word order: He gave the key to me. She sent a letter to him.

Intransitive verbs

Intransitive verbs do not take a direct object. Intransitive verbs may stand alone or may be followed by an adverbial modifier (an adverb, a phrase) or by a prepositional object.

Examples of sentences with intransitive verbs: Maria works. He is sleeping. She writes very quickly. He went there yesterday. They live in a small town. He spoke to the manager. I thought about it. I agree with you.

Linking verbs

Linking verbs (e.g., be, become, feel, get, grow, look, seem) are followed by a complement. The verb BE is the main linking verb. It is often followed by a noun or an adjective: He is a doctor. He is kind. (See The Verb BE in the section Grammar.)

Other linking verbs are usually followed by an adjective (the linking verb «become» may also be followed by a noun): He became famous. She became a doctor. He feels happy. It is getting cold. It grew dark. She looked sad. He seems tired.

The material below describes standard word order in different types of sentences very briefly. The other materials of the section Word Order give a more detailed description of standard word order and its peculiarities in different types of sentences.

Declarative sentences

Subject + predicate (+ object + adverbial modifier):

Maria works.

Tom is a writer.

This book is interesting.

I live in Moscow.

Tom writes short stories for children.

He talked to Anna yesterday.

My son bought three history books.

He is writing a report now.

(See Word Order in Statements in the section Grammar.)

Interrogative sentences

Interrogative sentences include general questions, special questions, alternative questions, and tag questions. (See Word Order in Questions in the section Grammar.)

General questions

Auxiliary verb + subject + main verb (+ object + adverbial modifier):

Do you live here? – Yes, I do.

Does he speak English? – Yes, he does.

Did you go to the concert? – No, I didn’t.

Is he writing a report now? – Yes, he is.

Have you seen this film? – No, I haven’t.

Special questions

Question word + auxiliary verb + subject + main verb (+ object + adverbial modifier):

Where does he live? – He lives in Paris.

What are you writing now? – I’m writing a new story.

When did they visit Mexico? – They visited Mexico five years ago.

What is your name? – My name is Alex.

How old are you? – I’m 24 years old.

Alternative questions

Alternative questions are questions with a choice. Word order before «or» is the same as in general questions.

Is he a teacher or a doctor? – He is a teacher.

Does he live in Paris or in Rome? – He lives in Rome.

Are you writing a report or a letter? – I’m writing a report.

Would you like coffee or tea? – Tea, please.

Tag questions

Tag questions consist of two parts. The first part has the same word order as statements; the second part is a short general question (the tag).

He is a teacher, isn’t he? – Yes, he is.

He lives here, doesn’t he? – No, he doesn’t.

You went there, didn’t you? – Yes, I did.

They haven’t seen this film, have they? – No, they haven’t.

Imperative sentences

Imperative sentences (commands, instructions, requests) have the same word order as statements, but the subject (you) is usually omitted. (See Word Order in Commands in the section Grammar.)

Go to your room.

Listen to the story.

Please sit down.

Give me that book, please.

Negative imperative sentences are formed with the help of the auxiliary verb «don’t».

Don’t cry.

Don’t wait for me.

Requests

Polite requests in English are usually in the form of general questions using «could, may, will, would». (See Word Order in Requests in the section Grammar.)

Could you help me, please?

May I speak to Tom, please?

Will you please ask him to call me?

Would you mind helping me with this report?

Exclamatory sentences

Exclamatory sentences have the same word order as statements (i.e., the subject is before the predicate).

She is a great singer!

It is an excellent opportunity!

How well he knows history!

What a beautiful town this is!

How strange it is!

In some types of exclamatory sentences, the subject (it, this, that) and the linking verb are often omitted.

What a pity!

What a beautiful present!

What beautiful flowers!

How strange!

Simple, compound, and complex sentences

English sentences are divided into simple sentences, compound sentences and complex sentences depending on the number and kind of clauses that they contain.

The term «clause»

The word «clause» is translated into Russian in the same way as the word «sentence». The word «clause» refers to a group of words containing a subject and a predicate, usually in a compound or complex sentence.

There are two kinds of clauses: independent and dependent. An independent clause can be a separate sentence (e.g., a simple sentence).

The main clause in a complex sentence and clauses in a compound sentence are independent clauses; the subordinate clause is a dependent clause.

Simple sentences

A simple sentence consists of one independent clause, has a subject and a predicate and may also have other parts of the sentence (an object, an adverbial modifier, an attribute).

Life goes on.

I’m busy.

Anton is sleeping.

She works in a hotel.

You don’t know him.

He wrote a letter to the manager.

Compound sentences

A compound sentence consists of two (or more) independent clauses connected by a coordinating conjunction (e.g., and, but, or). Each clause has a subject and a predicate.

Maria lives in Moscow, and her friend Elizabeth lives in New York.

He wrote a letter to the manager, but the manager didn’t answer.

Her children may watch TV here, or they may play in the yard.

Sentences connected by «and» may be connected without a conjunction. In such cases, a semicolon is used between them.

Maria lives in Moscow; her friend Elizabeth lives in New York.

Complex sentences

A complex sentence consists of the main clause and the subordinate clause connected by a subordinating conjunction (e.g., that, after, when, since, because, if, though). Each clause has a subject and a predicate.

I told him that I didn’t know anything about their plans.

Betty has been working as a secretary since she moved to California.

Tom went to bed early because he was very tired.

If he comes back before ten, ask him to call me, please.

(Different types of subordinate clauses are described in Word Order in Complex Sentences in the section Grammar.)

Базовый порядок слов

Порядок слов в английском языке строгий и довольно негибкий. Так как в английском языке мало окончаний, показывающих лицо, число, падеж и время, английский язык полагается на порядок слов для показа отношений между словами в предложении.

В русском языке мы полагаемся на окончания, чтобы понять, как слова взаимодействуют в предложении. Вы, наверное, помните пример, который придумал академик Л.В. Щерба для того, чтобы показать работу окончаний и суффиксов в русском языке: Глокая куздра штеко будланула бокра и кудрячит бокрёнка. (Нет английского перевода для этого примера.) Все, что нам нужно знать о взаимодействии героев в этом русском предложении, мы узнаём из окончаний и суффиксов.

Английские существительные не имеют падежных окончаний (только личные местоимения имеют падежные окончания), поэтому в основном именно порядок слов сообщает нам, где что находится в предложении и как они взаимодействуют. Сравните:

Собака видит кошку.

Кошка видит собаку.

Подлежащее и дополнение в этих (английских) предложениях полностью одинаковы по форме. Как узнать, кто кого видит? Правила английского порядка слов говорят нам об этом.

Модели порядка слов в английских предложениях

Предложение – это группа слов, содержащая подлежащее и сказуемое и выражающая законченную мысль. Порядок слов организует отдельные слова в предложения определённым образом и указывает, где найти подлежащее, сказуемое и другие члены предложения. Порядок слов и контекст помогают выявить значения отдельных слов.

Английские предложения делятся на повествовательные предложения (утверждения), вопросительные предложения (вопросы), повелительные предложения (команды, просьбы) и восклицательные предложения. Повествовательные предложения – самый распространённый тип предложений. Порядок слов в повествовательных предложениях служит основой для порядка слов в других типах предложений.

Основная минимальная модель базового порядка слов в английских повествовательных предложениях: подлежащее + сказуемое. Примеры: Maria works. Time flies.

Наиболее распространённая модель базового порядка слов в повествовательных предложениях: подлежащее + сказуемое + дополнение, часто называемая подлежащее + глагол + дополнение в английских лингвистических источниках. Примеры: Tom writes stories. The dog sees the cat.

Обычное повествовательное предложение, содержащее все пять членов предложения, например, «Mike read an interesting story yesterday», имеет следующий порядок слов:

Подлежащее ставится в начале предложения перед сказуемым; сказуемое следует за подлежащим; дополнение ставится после сказуемого; обстоятельство ставится после дополнения (или после глагола, если дополнения нет); определение (прилагательное) ставится перед своим существительным (определения в виде существительного с предлогом ставятся после своих существительных).

Тип глагола и порядок слов

Порядок слов после глагола обычно зависит от типа глагола (переходный глагол, непереходный глагол, глагол-связка). (Типы глаголов описываются в материале «Verbs Glossary of Terms» в разделе Grammar.)

Переходные глаголы

Переходные глаголы требуют прямого дополнения: Tom writes stories. Denis likes films. Anna bought a book. I saw him yesterday. (См. Transitive and Intransitive Verbs в разделе Miscellany.)

За некоторыми переходными глаголами (например, bring, give, send, show, tell) часто следуют два дополнения: косвенное дополнение и прямое дополнение. Например: He gave me the key. She sent him a letter. Такие предложения часто имеют следующий порядок слов: He gave the key to me. She sent a letter to him.

Непереходные глаголы

Непереходные глаголы не принимают прямое дополнение. За непереходными глаголами может ничего не стоять, или за ними может следовать обстоятельство (наречие, фраза) или предложное дополнение.

Примеры предложений с непереходными глаголами: Maria works. He is sleeping. She writes very quickly. He went there yesterday. They live in a small town. He spoke to the manager. I thought about it. I agree with you.

Глаголы-связки

За глаголами-связками (например, be, become, feel, get, grow, look, seem) следует комплемент (именная часть сказуемого). Глагол BE – главный глагол-связка. За ним часто следует существительное или прилагательное: He is a doctor. He is kind. (См. The Verb BE в разделе Grammar.)

За другими глаголами-связками обычно следует прилагательное (за глаголом-связкой «become» может также следовать существительное): He became famous. She became a doctor. He feels happy. It is getting cold. It grew dark. She looked sad. He seems tired.

Материал ниже описывает стандартный порядок слов в различных типах предложений очень кратко. Другие материалы раздела Word Order дают более подробное описание стандартного порядка слов и его особенностей в различных типах предложений.

Повествовательные предложения

Подлежащее + сказуемое (+ дополнение + обстоятельство):

Мария работает.

Том – писатель.

Эта книга интересная.

Я живу в Москве.

Том пишет короткие рассказы для детей.

Он говорил с Анной вчера.

Мой сын купил три книги по истории.

Он пишет доклад сейчас.

(См. Word Order in Statements в разделе Grammar.)

Вопросительные предложения

Вопросительные предложения включают в себя общие вопросы, специальные вопросы, альтернативные вопросы и разъединённые вопросы. (См. Word Order in Questions в разделе Grammar.)

Общие вопросы

Вспомогательный глагол + подлежащее + основной глагол (+ дополнение + обстоятельство):

Вы живёте здесь? – Да (живу).

Он говорит по-английски? – Да (говорит).

Вы ходили на концерт? – Нет (не ходил).

Он пишет доклад сейчас? – Да (пишет).

Вы видели этот фильм? – Нет (не видел).

Специальные вопросы

Вопросительное слово + вспомогательный глагол + подлежащее + основной глагол (+ дополнение + обстоятельство):

Где он живёт? – Он живёт в Париже.

Что вы сейчас пишете? – Я пишу новый рассказ.

Когда они посетили Мексику? – Они посетили Мексику пять лет назад.

Как вас зовут? – Меня зовут Алекс.

Сколько вам лет? – Мне 24 года.

Альтернативные вопросы

Альтернативные вопросы – это вопросы с выбором. Порядок слов до «or» такой же, как в общих вопросах.

Он учитель или врач? – Он учитель.

Он живёт в Париже или в Риме? – Он живёт в Риме.

Вы пишете доклад или письмо? – Я пишу доклад.

Хотите кофе или чай? – Чай, пожалуйста.

Разъединенные вопросы

Разъединённые вопросы состоят из двух частей. Первая часть имеет такой же порядок слов, как повествовательные предложения; вторая часть – краткий общий вопрос.

Он учитель, не так ли? – Да (он учитель).

Он живёт здесь, не так ли? – Нет (не живёт).

Вы ходили туда, не так ли? – Да (ходил).

Они не видели этот фильм, не так ли? – Нет (не видели).

Повелительные предложения

Повелительные предложения (команды, инструкции, просьбы) имеют такой же порядок слов, как повествовательные предложения, но подлежащее (вы) обычно опускается. (См. Word Order in Commands в разделе Grammar.)

Идите в свою комнату.

Слушайте рассказ.

Пожалуйста, садитесь.

Дайте мне ту книгу, пожалуйста.

Отрицательные повелительные предложения образуются с помощью вспомогательного глагола «don’t».

Не плачь.

Не ждите меня.

Просьбы

Вежливые просьбы в английском языке обычно в форме вопросов с использованием «could, may, will, would». (См. Word Order in Requests в разделе Grammar.)

Не могли бы вы помочь мне, пожалуйста?

Можно мне поговорить с Томом, пожалуйста?

Попросите его позвонить мне, пожалуйста.

Вы не возражали бы помочь мне с этим докладом?

Восклицательные предложения

Восклицательные предложения имеют такой же порядок слов, как повествовательные предложения (т.е. подлежащее перед сказуемым).

Она отличная певица!

Это отличная возможность!

Как хорошо он знает историю!

Какой это прекрасный город!

Как это странно!

В некоторых типах восклицательных предложений подлежащее (it, this, that) и глагол-связка часто опускаются.

Какая жалость!

Какой прекрасный подарок!

Какие прекрасные цветы!

Как странно!

Простые, сложносочиненные и сложноподчиненные предложения

Английские предложения делятся на простые предложения, сложносочинённые предложения и сложноподчинённые предложения в зависимости от количества и вида предложений, которые они содержат.

Термин «clause»

Слово «clause» переводится на русский язык так же, как слово «sentence». Слово «clause» имеет в виду группу слов, содержащую подлежащее и сказуемое, обычно в сложносочинённом или сложноподчинённом предложении.

Есть два вида «clauses»: независимые и зависимые. Независимое предложение может быть отдельным предложением (например, простое предложение).

Главное предложение в сложноподчинённом предложении и предложения в сложносочинённом предложении – независимые предложения; придаточное предложение – зависимое предложение.

Простые предложения

Простое предложение состоит из одного независимого предложения, имеет подлежащее и сказуемое и может также иметь другие члены предложения (дополнение, обстоятельство, определение).

Жизнь продолжается.

Я занят.

Антон спит.

Она работает в гостинице.

Вы не знаете его.

Он написал письмо менеджеру.

Сложносочиненные предложения

Сложносочинённое предложение состоит из двух (или более) независимых предложений, соединённых соединительным союзом (например, and, but, or). Каждое предложение имеет подлежащее и сказуемое.

Мария живёт в Москве, а её подруга Элизабет живёт в Нью-Йорке.

Он написал письмо менеджеру, но менеджер не ответил.

Её дети могут посмотреть телевизор здесь, или они могут поиграть во дворе.

Предложения, соединённые союзом «and», могут быть соединены без союза. В таких случаях между ними ставится точка с запятой.

Мария живёт в Москве; её подруга Элизабет живёт в Нью-Йорке.

Сложноподчиненные предложения

Сложноподчинённое предложение состоит из главного предложения и придаточного предложения, соединённых подчинительным союзом (например, that, after, when, since, because, if, though). Каждое предложение имеет подлежащее и сказуемое.

Я сказал ему, что я ничего не знаю об их планах.

Бетти работает секретарём с тех пор, как она переехала в Калифорнию.

Том лёг спать рано, потому что он очень устал.

Если он вернётся до десяти, попросите его позвонить мне, пожалуйста.

(Различные типы придаточных предложений описываются в материале «Word Order in Complex Sentences» в разделе Grammar.)

In linguistics, word order (also known as linear order) is the order of the syntactic constituents of a language. Word order typology studies it from a cross-linguistic perspective, and examines how different languages employ different orders. Correlations between orders found in different syntactic sub-domains are also of interest. The primary word orders that are of interest are

- the constituent order of a clause, namely the relative order of subject, object, and verb;

- the order of modifiers (adjectives, numerals, demonstratives, possessives, and adjuncts) in a noun phrase;

- the order of adverbials.

Some languages use relatively fixed word order, often relying on the order of constituents to convey grammatical information. Other languages—often those that convey grammatical information through inflection—allow more flexible word order, which can be used to encode pragmatic information, such as topicalisation or focus. However, even languages with flexible word order have a preferred or basic word order,[1] with other word orders considered «marked».[2]

Constituent word order is defined in terms of a finite verb (V) in combination with two arguments, namely the subject (S), and object (O).[3][4][5][6] Subject and object are here understood to be nouns, since pronouns often tend to display different word order properties.[7][8] Thus, a transitive sentence has six logically possible basic word orders:

- about half of the world’s languages deploy subject–object–verb order (SOV);

- about one-third of the world’s languages deploy subject–verb–object order (SVO);

- a smaller fraction of languages deploy verb–subject–object (VSO) order;

- the remaining three arrangements are rarer: verb–object–subject (VOS) is slightly more common than object–verb–subject (OVS), and object–subject–verb (OSV) is the rarest by a significant margin.[9]

Constituent word orders[edit]

These are all possible word orders for the subject, object, and verb in the order of most common to rarest (the examples use «she» as the subject, «loves» as the verb, and «him» as the object):

- SOV is the order used by the largest number of distinct languages; languages using it include Japanese, Korean, Mongolian, Turkish, the Indo-Aryan languages and the Dravidian languages. Some, like Persian, Latin and Quechua, have SOV normal word order but conform less to the general tendencies of other such languages. A sentence glossing as «She him loves» would be grammatically correct in these languages.

- SVO languages include English, Spanish, Portuguese, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Serbo-Croatian,[10] the Chinese languages and Swahili, among others. «She loves him.»

- VSO languages include Classical Arabic, Biblical Hebrew, the Insular Celtic languages, and Hawaiian. «Loves she him.»

- VOS languages include Fijian and Malagasy. «Loves him she.»

- OVS languages include Hixkaryana. «Him loves she.»

- OSV languages include Xavante and Warao. «Him she loves.»

Sometimes patterns are more complex: some Germanic languages have SOV in subordinate clauses, but V2 word order in main clauses, SVO word order being the most common. Using the guidelines above, the unmarked word order is then SVO.

Many synthetic languages such as Latin, Greek, Persian, Romanian, Assyrian, Assamese, Russian, Turkish, Korean, Japanese, Finnish, Arabic and Basque have no strict word order; rather, the sentence structure is highly flexible and reflects the pragmatics of the utterance. However, also in languages of this kind there is usually a pragmatically neutral constituent order that is most commonly encountered in each language.

Topic-prominent languages organize sentences to emphasize their topic–comment structure. Nonetheless, there is often a preferred order; in Latin and Turkish, SOV is the most frequent outside of poetry, and in Finnish SVO is both the most frequent and obligatory when case marking fails to disambiguate argument roles. Just as languages may have different word orders in different contexts, so may they have both fixed and free word orders. For example, Russian has a relatively fixed SVO word order in transitive clauses, but a much freer SV / VS order in intransitive clauses.[citation needed] Cases like this can be addressed by encoding transitive and intransitive clauses separately, with the symbol «S» being restricted to the argument of an intransitive clause, and «A» for the actor/agent of a transitive clause. («O» for object may be replaced with «P» for «patient» as well.) Thus, Russian is fixed AVO but flexible SV/VS. In such an approach, the description of word order extends more easily to languages that do not meet the criteria in the preceding section. For example, Mayan languages have been described with the rather uncommon VOS word order. However, they are ergative–absolutive languages, and the more specific word order is intransitive VS, transitive VOA, where the S and O arguments both trigger the same type of agreement on the verb. Indeed, many languages that some thought had a VOS word order turn out to be ergative like Mayan.

Distribution of word order types[edit]

Every language falls under one of the six word order types; the unfixed type is somewhat disputed in the community, as the languages where it occurs have one of the dominant word orders but every word order type is grammatically correct.

The table below displays the word order surveyed by Dryer. The 2005 study[11] surveyed 1228 languages, and the updated 2013 study[8] investigated 1377 languages. Percentage was not reported in his studies.

| Word Order | Number (2005) | Percentage (2005) | Number (2013) | Percentage (2013) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOV | 497 | 40.5% | 565 | 41.0% |

| SVO | 435 | 35.4% | 488 | 35.4% |

| VSO | 85 | 6.9% | 95 | 6.9% |

| VOS | 26 | 2.1% | 25 | 1.8% |

| OVS | 9 | 0.7% | 11 | 0.8% |

| OSV | 4 | 0.3% | 4 | 0.3% |

| Unfixed | 172 | 14.0% | 189 | 13.7% |

Hammarström (2016)[12] calculated the constituent orders of 5252 languages in two ways. His first method, counting languages directly, yielded results similar to Dryer’s studies, indicating both SOV and SVO have almost equal distribution. However, when stratified by language families, the distribution showed that the majority of the families had SOV structure, meaning that a small number of families contain SVO structure.

| Word Order | No. of Languages | Percentage | No. of Families | Percentage[a] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOV | 2275 | 43.3% | 239 | 56.6% |

| SVO | 2117 | 40.3% | 55 | 13.0% |

| VSO | 503 | 9.5% | 27 | 6.3% |

| VOS | 174 | 3.3% | 15 | 3.5% |

| OVS | 40 | 0.7% | 3 | 0.7% |

| OSV | 19 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.2% |

| Unfixed | 124 | 2.3% | 26 | 6.1% |

Functions of constituent word order[edit]

Fixed word order is one out of many ways to ease the processing of sentence semantics and reducing ambiguity. One method of making the speech stream less open to ambiguity (complete removal of ambiguity is probably impossible) is a fixed order of arguments and other sentence constituents. This works because speech is inherently linear. Another method is to label the constituents in some way, for example with case marking, agreement, or another marker. Fixed word order reduces expressiveness but added marking increases information load in the speech stream, and for these reasons strict word order seldom occurs together with strict morphological marking, one counter-example being Persian.[1]

Observing discourse patterns, it is found that previously given information (topic) tends to precede new information (comment). Furthermore, acting participants (especially humans) are more likely to be talked about (to be topic) than things simply undergoing actions (like oranges being eaten). If acting participants are often topical, and topic tends to be expressed early in the sentence, this entails that acting participants have a tendency to be expressed early in the sentence. This tendency can then grammaticalize to a privileged position in the sentence, the subject.

The mentioned functions of word order can be seen to affect the frequencies of the various word order patterns: The vast majority of languages have an order in which S precedes O and V. Whether V precedes O or O precedes V, however, has been shown to be a very telling difference with wide consequences on phrasal word orders.[13]

Semantics of word order[edit]