But this is a program that over time has not stopped evolving and growing. Thus, it has been receiving new updates and functions in order to meet the expectations and needs of its millions of users. Therefore and due to all this, at the moment we can find a multitude of functions, more or less useful or extended, but which try to cover all environments. At the same time we must bear in mind that here we are not only going to work with texts , but also that the application supports all kinds of additional elements. Here we find graphics, tables, images , videos, etc; many of them from the Insert menu.

To all that we have mentioned so far, another very interesting element as well as useful that we can add, are those called lists. In fact, in these we are going to focus on these same lines , a type of object as used and versatile as lists.

Surely, over the years, many of you have used these elements to add a plus to your documents. Well, that is why here we are going to focus on showing you in detail what these objects can offer us. We will also see the types of lists that we can use in Word , as well as the utility that they will offer us separately.

What is a Word list and what is it for?

First of all and as its own name lets us glimpse, the Word lists function allows us to carry out an accumulation of similar elements, and ordered properly. Thus, what we achieve is to generate our own personal lists that in the end will come in handy to show a set of elements, but in a structured way.

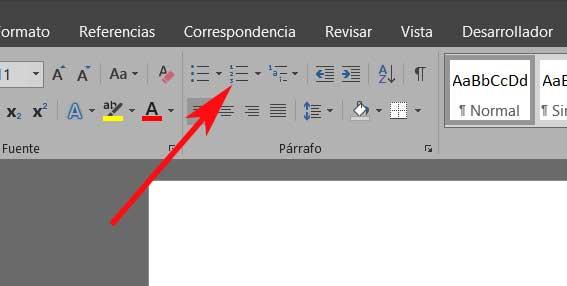

Of course, we must bear in mind that the advanced program of the Redmond , presents us with several ways, both to create those lists, and formats for them. For example, initially we have the possibility of accessing this type of elements directly from the Start menu option of Word itself. Thus, at the top of the section called Paragraph, we see the formats of the same that we can access and use below.

As we mentioned, a program of the potential of this Microsoft , presents us with several alternatives to choose from when dealing with its additional elements. Here come into play, as it could not be otherwise, the lists that concern us in these lines. That is why below we are going to talk about each of the types of lists that we are going to find here and that we can use. Each will be best suited for a type of use, or work environment.

Numbered lists

It is evident that the numbered lists are perhaps one of the most common ones that are often used when the time comes to make use of these elements. They could be considered as the most basic of the exposed formats, but perhaps they are also the most useful. These are represented, in the section discussed above, by a button with a series of numbers vertically. Therefore, to see what this format offers us, we will only have to click on it.

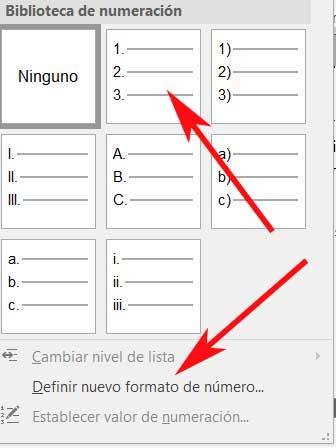

It is worth mentioning that despite being called Numbering Lists, here we can use other elements in the form of separators for the elements of the same. We will see these on the screen by clicking on the drop-down list to the right of the mentioned button. In this way, we can opt to use simple numbers , upper or lower case letters, numbers with a separator, etc. Say that when you click on the button directly, the list will begin to be classified by simple numbers.

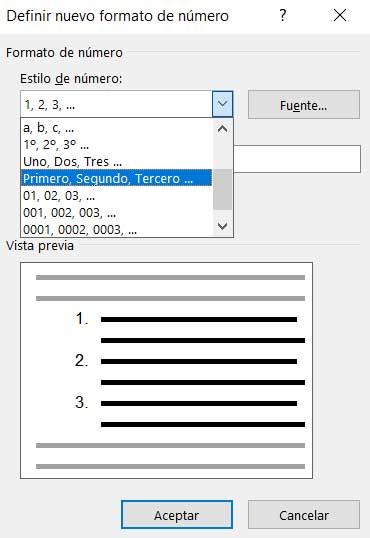

But that’s not all, but at the same time we can specify our own custom classifier, all through the link Define new number format.

Here the program itself proposes a wide range of formats that will serve as classification elements for the list that we will create. Similarly, we will have the possibility to create a custom one by adding characters to the Number format field. Say that in this same window we have a preview to visualize how the numerical list that we are going to create will look like. As you can imagine, this function opens up a wide range of possibilities when creating basic and original lists in Word.

Before we finish this type, we will tell you that a shortcut to creating numerical lists here is, for example, writing a 1 followed by a -. Thus, when pressing the space bar, Word will directly create a list of this type for us to fill in and customize.

Bullet lists

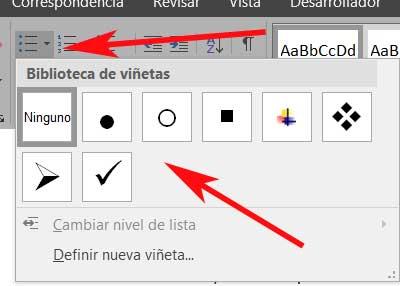

On the other hand, a little more original than those previously reviewed, we find the Bullet lists. These we will find in the same section of the main interface of the program that we discussed earlier. But in this case, if we choose to use this specific format, say that it is represented by a button with a series of small squares. As in the previous case, when you click on the small arrow on the right of it, the corresponding drop-down list appears.

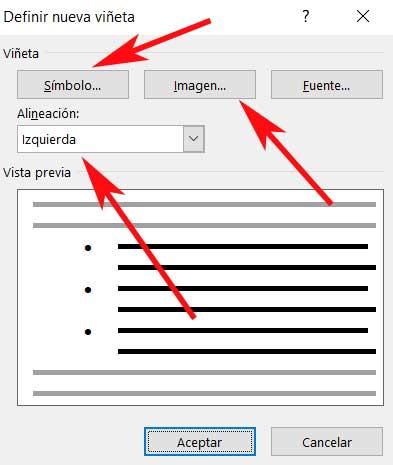

Here, as before, we are going to find a series of slightly more graphic elements or objects that will serve as cataloguers or separators for this new list. In this section, what we are going to find are a series of elements in the form of symbols that can act as separators for the elements of the new list. Thus, we find circles, squares, arrows, etc. But of course, as in the previous case, we can also define new ones. For this we click on Define new bullet from the mentioned drop-down list.

The most interesting thing about this is that here we can specify that we want to use some of the multiple symbols that we usually use throughout the operating system. But that is not all, we will also have the possibility to select an image that we have stored in the disk drives . Of course, we should be a little cautious, since this image will be repeated over and over again for each item on the list.

As in the previous case, we also have the possibility to shorten the process of creating a custom list. For this, it is enough that we write an asterisk on a new line, so that the bullet list starts automatically by pressing the space bar .

Multilevel lists

So far we have been able to see the main objective and how we can create both numerical and bulleted lists. Each format can serve us in an environment or type of independent use, we can also create both lists made up of generic classifiers, as well as more personalized and therefore original.

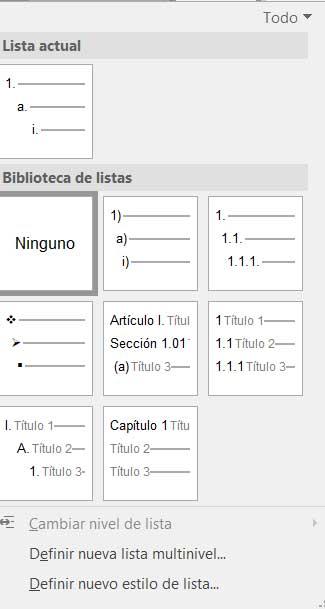

However, it is also worth taking a look at the so-called Multilevel lists. We will find these in the same section of the Word interface of the previous two. Of course, in this case they are represented by the levels of which they will be composed, in miniature. So, to start we will tell you these Multilevel are elements of this same type that we have seen, but they allow you to create a list within another. It is evident that for this the container must already exist, so within the primary list, we can create others. Say that these will keep the indentations that we added initially, as well as the numbering indicated in their design.

That is why it could be said that the use of these elements is like taking the use of the simple lists previously reviewed, one step further. In fact, if we deploy the corresponding drop-down menu on its button , we find designs similar to those we saw in the previous formats, but in this case, nested. In the same way we can create the design of our new multilevel list from the link Define new list style.

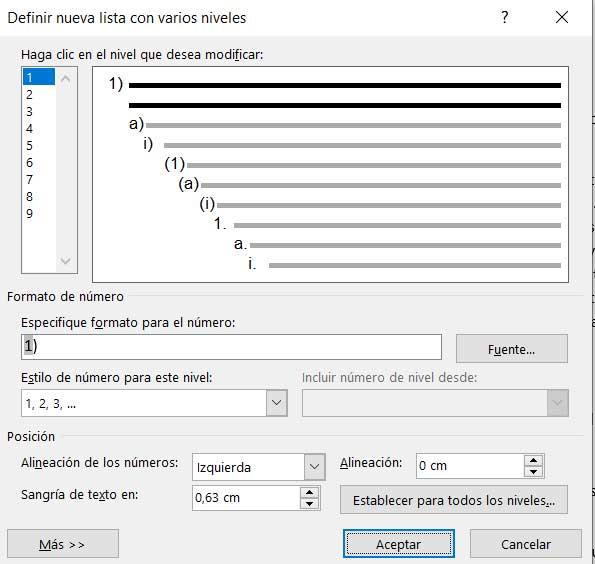

At the same time, we find another link in the same window that allows us to define a new, multilevel, personalized list. Here we will have the opportunity to specify various parameters of this nested list element. Among these we find the possibility of customizing the types of separators of the different lists, including the level number, the alignment of the elements, the distance of the indentation , etc.

How to sort a Word list

First, it must be clear that in order to sort the components of a Word list, we must first create an element of this type. For this we can use any of the types that we talked about previously, to later mark the list in its entirety.

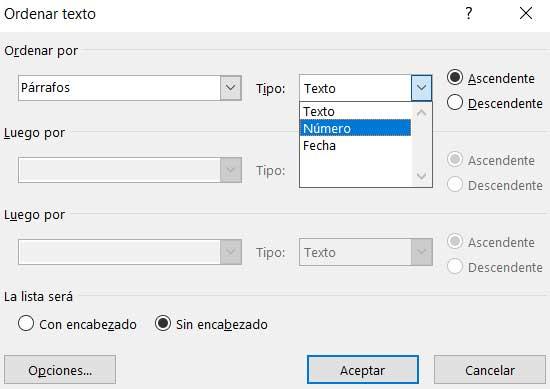

Well, once we have marked it with the mouse, we return to look at the Paragraph section, but in this case we opted for the button called Order. This is represented by the letters A and Z with an arrow, where we can directly click. There are no drop-down lists here, as before. But of course, by clicking on the mentioned button that we discussed, we find a new window that will give us the opportunity to customize the order to use in the marked list, depending on the needs of each case.

In this way, the program offers us the possibility of sorting the lists marked by paragraphs or titles on the one hand. When it comes to placing the elements that are part of it, Word offers us to order them by alphabetical, numerical order, or by date. Thus, if we are a little tricky and create the source lists in a structured way, this function will allow us to order their elements in a few seconds. And it is that the correct use of these elements will help to better understand our created documents.

The two most common types of lists in Word are numbered lists and bulleted lists. They can be handy for organizing your text, but you may not always like exactly how they behave. Fortunately, you have total control over the formatting of lists in Word. Use the following articles to learn about working with lists in your document.

Tips, Tricks, and Answers

The following articles are available for the ‘Lists’ topic. Click the

article»s title (shown in bold) to see the associated article.

Applying Formatting in Lists

If you want to change the formatting applied to numbers or bullets in your lists, you’ll appreciate the information in this tip. All you need to do is format the end-of-paragraph marker for each item in the list.

Converting List Types

There are two types of common lists you can create in Word: bulleted lists and numbered lists. You can switch between the type types by using the techniques described in this tip.

Counting Lists

Word makes it easy to add both numbered lists and bulleted lists to your document. If you are working with longer documents, you may need a way to count the number of lists that the document contains. Getting such a figure remains elusive, however, as explained in this tip.

Creating a List

You can format both numbered and bulleted lists very easily in Word. The tools available on the Home tab of the ribbon make it a snap.

Removing a Bulleted or Numbered List

If you want to convert bulleted or numbered lists back to regular text (so they appear just like the rest of your document), you can do so using the same tools you use to create the lists. This tip shows just how easy this conversion process is.

Removing a List

If you have lists in your document, either bulleted or numbered, you may want to change them back to regular text at some point. This is easy to do using the same tools you used to create the lists in the first place.

Understanding and Creating Lists

There are two types of common lists you can use in a document: bulleted lists and numbered lists. This tip explains the differences between the two and shows how you can easily create them both.

Understanding Lists

When designing documents there are two types of lists commonly used: numbered lists and bulleted lists. This tip introduces you to the types of lists available.

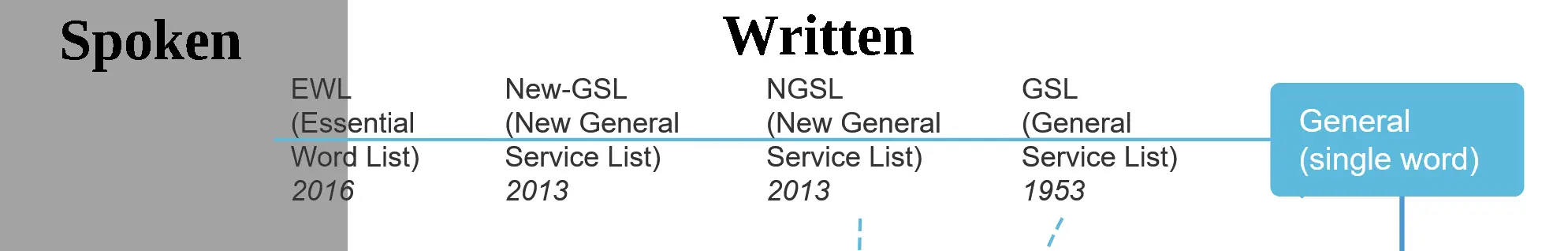

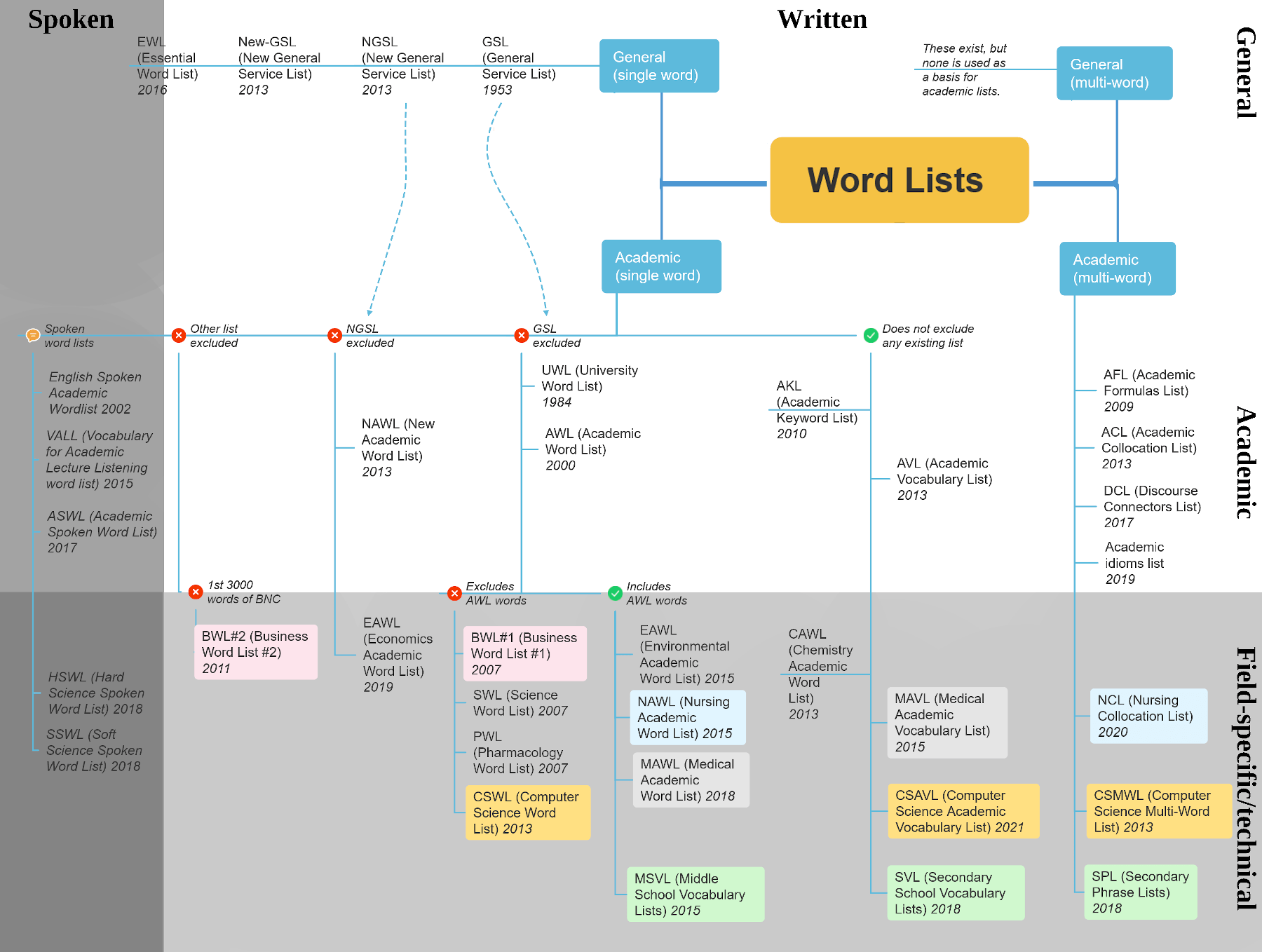

There are many word lists for general and academic English study. This page describes

the most important ones, first giving an

overview of the different types of word list, then presenting a

more detailed summary of individual lists.

The summary contains links to other pages on the site which have more detail of each list and (often) a complete copy of the list itself.

There is a companion page in this section which gives

information on why word lists are important (and tips on how to use them).

[Note: Links to other pages are in blue, links to other parts of this page are in red.]

Types of word list

Word lists can be divided into three types, namely

general word lists and

academic word lists, although as will be explained below, academic lists can be sub-divided into

general academic lists and

field-specific (i.e. subject-specific) academic lists.

An additional way to classify word lists is those which contain only single words (the majority of the lists are this type), and

multi-word lists. A final way to classify lists is written vs. spoken. Most of the lists that exist are

for written English, though many of the multi-word lists include both a spoken and written component.

General word lists (single words)

Interest in word lists began with studies of core or general vocabulary, that is, words having high frequency across a wide range of

texts. The first general word list to have important use in language study was the

General Service List (GSL), created by Michael West in 1953.

This list has been used to design EFL materials and courses, and, despite its age, it is probably still the most widely used list of general vocabulary.

Originally consisting of 2000 words (called headwords) and their corresponding word families, it was revised in 1995 by Bauman and Culligan,

with an increase in the number of headwords from 2000 to 2284.

One criticism of the GSL is its inclusion of too many low frequency words, some of which are a product of its age (e.g. shilling, headdress, cart, servant) while

excluding more recent vocabulary (e.g. computer, television, Internet). A second criticism is that it uses word families. The assumption behind the use of

word families is that once one word is known, other members of the family can be easily recognised; however, this may not always be the case. Examples of

distantly related word family pairs in the GSL are: please/unpleasantly, part/particle and value/invaluable. Additionally, some word

forms are used more frequently than others, and the inclusion of less frequent forms adds an unnecessarily burden to the learning load of students.

These criticisms have led to the creation of two updated versions of the list, both devised in 2013, both called the New General Service List.

Both lists use inflected forms and variant spellings (called lemmas), rather than extended word families.

The first, abbreviated to

NGSL, was developed by Browne, Culligan and Phillips. It is a list of 2801 words which give over 90% coverage.

It was generated from a corpus of 273 million words, 100 times larger than that used for the GSL.

The second list, abbreviated to

new-GSL, was devised by Brezina and Gablasova from a corpus of over 12 billion words.

It consists of 2494 words and gives around 80% coverage.

General word lists (multi-word)

The above are all single word lists. There are several multi-word lists for general vocabulary, such as the

First 100 Spoken Collocations (First 100) by Shin and Nation (2008), and the Phrasal Expressions List (PHRASE List) by Martinez and Schmitt (2012). However,

since none of these is used as a basis for academic word lists, in contrast to the general lists given above, they are not explained here in detail.

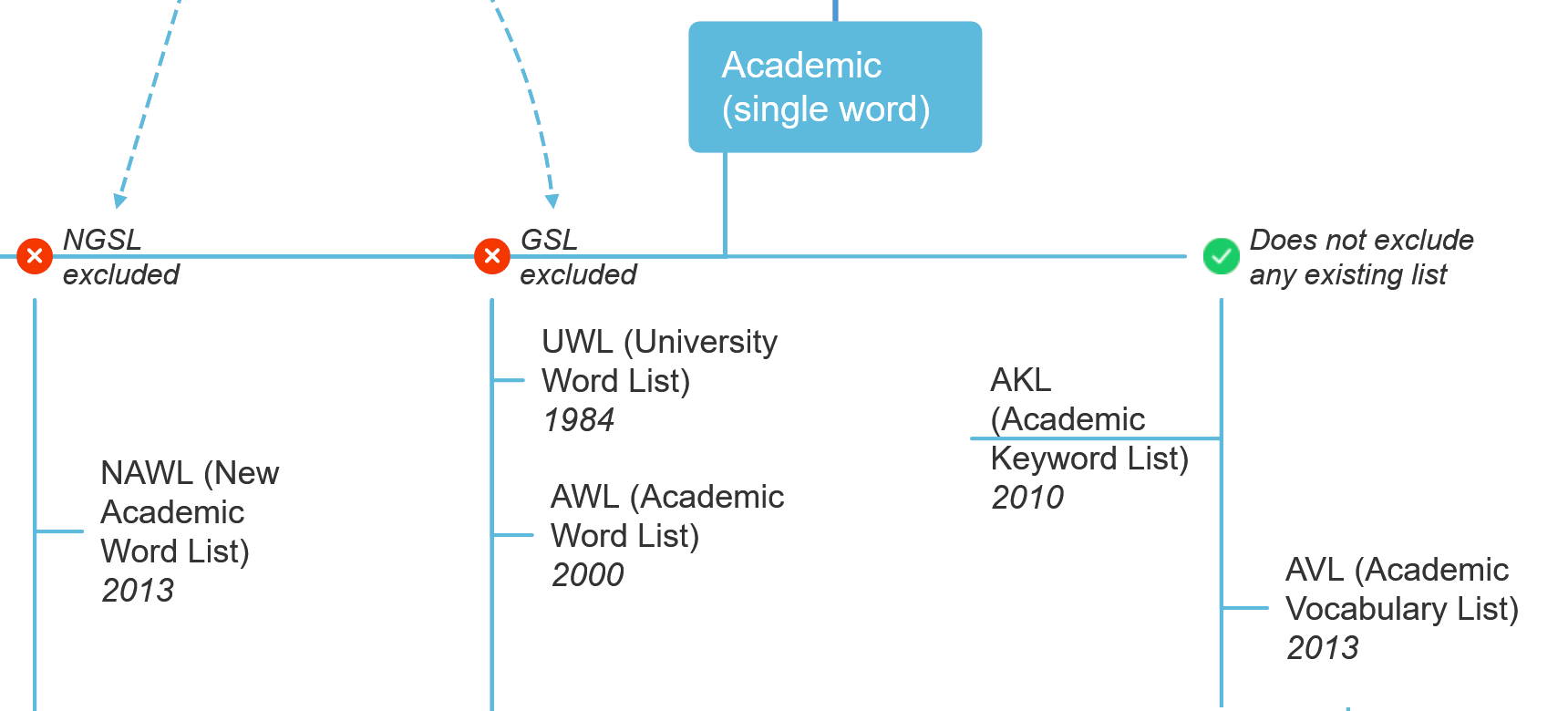

Academic word lists (single words)

Researchers have long been interested in defining and isolating academic vocabulary, and there have been many attempts to devise

lists which are of general use to students of academic English.

The first widely used academic word list was the

University Word List (UWL),

created in 1984 by Xue and Nation. It comprises 836 word families, divided into levels based on frequency.

It excludes words from the GSL, and gives 8.5% coverage of academic texts. It was developed by combining four existing lists.

A major update to the UWL came in 2000, when Averil Coxhead, of the University of Wellington, devised the

Academic Word List (AWL). This list

has been hugely influential and is perhaps the most widely known and used academic word list. Like the UWL, it comprises word families and is

divided into levels based on frequency. It gives similar coverage, around 10% of texts; however, it does so using far fewer word families, 570 in total.

Like the UWL, it excludes words from the GSL. It was devised in a more systematic way, using a corpus of texts from a range of academic disciplines.

Although the AWL is still widely used, it has received criticism in a number of areas. One criticism is that it is based on the

GSL, which is a very old list, dating from 1953. A second criticism is that, like the GSL, it uses word families, with the same problems as mentioned for

the GSL above.

In response to these criticisms, other academic word lists have been created. One of these is the

Academic Keyword List (AKL), developed by Paquot in 2010. This

consists of 930 words which appear more frequently in academic texts than non-academic ones, a tendency called keyness,

which leads to the name of the list.

A second list is the

New Academic Word List (NAWL) by

Browne, Culligan and Phillips. This list responds to the criticisms of the AWL by using lemmas rather than word families, and by basing itself on a more

updated general service list, the

NGSL, created by the authors at the same time, in 2013.

A third updated list is the

Academic Vocabulary List (AVL), developed by Gardner and Davies in 2013. This list, which is also lemma-based,

selects academic words by considering their ratio in academic versus non-academic texts, with words needing to occur 1.5 times as often in the

academic texts as in non-academic ones. This is similar to the approach used to devise the AKL (above), and in contrast to lists like the AWL and NAWL which

exclude an existing general service list. In addition, the authors considered the range of words in the academic disciplines used in their corpus,

the dispersion, and discipline measure, which required that words could not occur more than three times the expected frequency in any of

the disciplines. This approach has been influential in the development of other,

field-specific lists, as well as some

technical lists, as explained below.

There are several lists specifically for academic spoken English (as distinct from the spoken components of the multi-word lists, below).

These include the English Spoken Academic Wordlist, devised by Nesi in 2002,

the Academic Spoken Word List (ASWL), devised by Dang et al. in 2017, and

the Vocabulary for Academic Lecture Listening word list (VALL), devised by Thompson in 2015.

Academic word lists (multi-word)

Focusing exclusively on single words can lead learners to overlook valuable multi-word constructions which are commonly used in academic English.

For example, while use of the word thing is generally considered to be poor

academic style, it occurs in several phrases used by expert writers, such as

the same thing as and other things being equal.

Several multi-word lists have been developed for academic English. One is the

Academic Formulas List (AFL), devised by Simpson-Vlach and Ellis in 2009. This list

gives the most common formulaic sequences in academic English, i.e. recurring word sequences three to five words long.

There are three separate lists: one for formulas that are common in both academic spoken and written English (the ‘core’ AFL),

one for spoken English, and one for written English.

Another multi-word list is the

Academic Collocation List (ACL), developed by Ackermann and Chen in 2013. The ACL

contains 2469 of the most frequent and useful collocations which occur in written academic English.

A third list is the

Discourse Connectors List (DCL), devised by Rezvani Kalajahi, Neufeld and Abdullah in 2017. This list

classifies and describes 632 discourse connectors, ranking them by frequency in three different registers (academic, non-academic and spoken).

More recently, there is the

Academic idioms list, developed by Miller in 2019. This gives 170 idioms which are common in spoken academic

English, and 38 which are frequently used in written academic English.

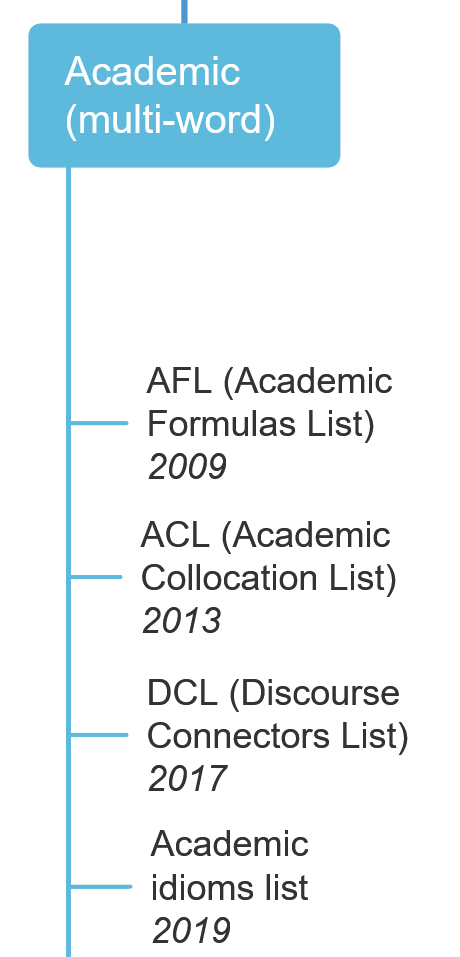

Field-specific academic word lists (single words)

Academic word lists such as the AWL are designed to be used by students of all disciplines. Researchers have found, however, that the AWL and other lists

provide varied coverage in different subject areas. For example, the AWL provides 12.0% coverage of the Commerce sub-corpus used to derive the list,

but only 9.1% for the Science sub-corpus (with only 6.2% for Biology).

Additionally, words in the AWL (and similar lists) occur with different frequencies in different disciplines.

For example, words such as legal, policy, income, finance and legislate,

which all fall in the first (most frequent) sublist of the AWL, may be common in Business or Finance,

but are very infrequent in disciplines such as Chemistry.

Words also have different collocations and meanings across different subject areas. Examples are base, which has a special meaning in Chemistry,

and bug, which has a different meaning in Computer Science than in general English.

Researchers have therefore become increasingly interested in field-specific (i.e. subject-specific) academic lists, in disciplines ranging

from science to business to medicine. These are generally not

technical word lists, since they are intended to comprise academic (sub-technical) vocabulary.

However, not all of them set out to exclude technical words (some actually set out to include them), and even for those that do,

the line between academic and technical words is often blurred.

Broadly speaking, there are three approaches used by researchers when devising field-specific academic lists.

The first of these is to use the GSL and AWL as a starting point, and to devise a third list which supplements the other two. These lists

exclude GSL and AWL words, and, since they are based on word family lists, also comprise word families.

These lists usually replace the ‘A’ of ‘AWL’ with a subject specific letter.

Examples are the

SWL (Science Word List), the

BWL#1 (Business Word List #1), the

Pharmacology Word List and the

CSWL (Computer Science Word List).

The second approach is to assume that learners are already familiar with general vocabulary and to devise a second list which replaces

other academic lists such as the AWL or NAWL for specific subject areas. As such, these lists exclude the GSL (or NGSL), but do not

exclude any other lists such as the AWL.

These lists usually add the subject letter before ‘AWL’ to derive their name.

Examples are the

MAWL (Medical Academic Word List) and the

NAWL (Nursing Academic Word List), both of which exclude the GSL and are word family lists (like the GSL), and the

EAWL (Economics Academic Word List), which excludes the NGSL and is a lemma-based list (like the NGSL).

The third approach is to devise a single, completely independent list, which includes words based on ratio, dispersion, and other measures, in a similar

way the AVL. These lists, which are usually lemma-based, tend to use ‘AVL’ in their name, preceded by an abbreviation for the subject. Examples are the

MAVL (Medical Academic Vocabulary List) and the

CSAVL (Computer Science Academic Vocabulary List). The

Chemistry Academic Word List (CAWL), although it broadly uses

the same approach, uses word families, and also predates the creation of the AVL, and does not follow the same naming pattern.

There are two further lists which deserve mention here. Both have been developed using the same principles as the lists above; however, they

are intended for school-age rather than university students.

The first is the

Middle School Vocabulary Lists (MSVL). These are a series of five lists developed in 2015 by Greene and

Coxhead, along similar lines to Coxhead’s earlier AWL, i.e. by excluding the GSL and working with word families. However, this list is

intended not for students at or preparing for university, but middle school students, and covers technical rather than purely academic vocabulary.

The lists cover the following subjects: English, Health, Mathematics, Science, and Social Science/History.

Another is the

Secondary Schools Vocabulary Lists (SVL). Developed in 2018 by Green and Lambert, the SVL are a series of lists of

discipline-specific words for secondary school education, covering eight core subjects: Biology, Chemistry, Economics, English, Geology, History,

Mathematics, and Physics. The lists were devised using methods similar to those used to create the

AVL and the

MAVL, which are lemma-based lists which consider measures such as range and dispersion along with word frequency.

The lists also include word family versions, as well as collocation lists. The SVL are designed to help students in secondary schools improve their

disciplinary literacy.

There are at least two field-specific academic lists of spoken English, both devised by Dang in 2018. They are the Hard Science Spoken Word

List (HSWL), and the Soft Science Spoken Word List (SSWL).

Technical word lists (multi-word)

There have been some attempts to create discipline-specific multi-word lists, using principles employed in the creation of academic lists.

One is the Computer Science Multi-Word List (CSMWL), created by Minshall at the same time as the

Computer Science Word List (CSWL). However, it comprises only 23 items.

Another example is the

Secondary Phrase Lists (SPL), developed in 2018 by Green and Lambert, who also developed the SVL (above).

This is a series of lists, for the same eight subjects as covered by the SVL, presenting noun-noun, adjective-noun, noun-verb, verb-noun and verb-adverb

collocations.

A third, more recent example is the

Nursing Collocation List (NCL), developed in 2020 by Mandić and

Dankić. It comprises 488 collocations which occur frequently in nursing journal articles.

Summary

The following image, and table below, provide an overview of the major word lists. Spoken word lists are only included in the table

(in italics). All word lists (except spoken ones) are explained in more detail later. Note: there is a higher resolution copy of the following image in the

infographics section.

| Single word | Multi-word | |

| General |

• GSL (General Service List) 1953 • NGSL (New General Service List) 2013 • New-GSL (New General Service List) 2013 |

These exist, but none are used as a basis for academic lists. |

| Academic |

• UWL (University Word List) 1984 • AWL (Academic Word List) 2000 • AKL (Academic Keyword List) 2010 • NAWL (New Academic Word List) 2013 • AVL (Academic Vocabulary List) 2013 • English Spoken Academic Wordlist 2002 • ASWL (Academic Spoken Word List) 2017 • VALL (Vocabulary for Academic Lecture Listening word list) 2015 |

• AFL (Academic Formulas List) 2009 • ACL (Academic Collocation List) 2013 • DCL (Discourse Connectors List) 2017 • Academic idioms list 2019 |

| Field-specific/ technical |

• SWL (Science Word List) 2007 • BWL#1 (Business Word List #1) 2007 • PWL (Pharmacology Word List) 2007 • MAWL (Medical Academic Word List) 2008 • AgroCorpus List 2009 • BEL (Basic Engineering List) 2009 • BWL#2 (Business Word List #2) 2011 • CSWL (Computer Science Academic Word List) 2013 • CAWL (Chemistry Academic Word List) 2013 • MAVL (Medical Academic Vocabulary List) 2015 • NAWL (Nursing Academic Word List) 2015 • EAWL (Environmental Academic Word List) 2015 • EAWL (Economics Academic Word List) 2019 • CSAVL (Computer Science Academic Vocabulary List) 2021 • MSVL (Middle School Vocabulary Lists) 2015 • SVL (Secondary School Vocabulary Lists) 2018 • HSWL (Hard Science Spoken Word List) 2018 • SSWL (Soft Science Spoken Word List) 2018 |

• CSMWL (Computer Science Multi-Word List) 2013 • SPL (Secondary Phrase Lists) 2018 • NCL (Nursing Collocation List) 2020 |

References

Granger, S., and Larsson, T. (2021), ‘Is core vocabulary a friend or foe of academic writing? Singleword vs multi-word uses of THING’, Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 52 (2021) 100999.

Hyland, K. and Tse, P. (2007). ‘Is There an “Academic Vocabulary”?’, TESOL QUARTERLY, Vol. 41, No. 2, June 2007.

Radmila Palinkašević, M.A. (2017), ‘Specialized Word Lists — Survey of the Literature — Research Perspective’, Research in Pedagogy, Vol. 7, Issue 2 (2017), pp. 221-238.

Therova, D. (2020), ‘Review of Academic Word Lists’, The Electronic Journal for English as a Second Language, Volume 24, Number 1.

Detailed summary of individual lists

Below is more detail about the lists above. The lists are sorted into the following categories:

- General (core) vocabulary single word lists (3 lists)

- Academic single word lists: general purpose (5 lists)

- Academic single word lists: field-specific (14 lists)

- Technical single word lists (2 lists)

- Academic multi-word lists (4 lists)

- Technical multi-word lists (3 lists)

General (core) vocabulary single word lists

The following gives a more detailed summary of the general word lists mentioned on this page. Blue links

are links to other pages (with even more detail, and, often, a copy of the full word list).

| Word list | About |

| General Service List (GSL) |

Author: West (1953) — Size: 2284 word families — Originally a list of the 2000 most frequent word families in English, covering around 80% of various types of texts. Further divided into the 1K (first 1000 words) and 2K (second 1000). Used as the basis for many graded readers and other ESL/EFL materials. The list was revised in 1995 by Bauman and Culligan, and their revision, which is the version most commonly used, contains 2284 words. — Examples: the, be, of, and, a, to, in, he, have, it |

| New General Service List (NGSL) |

Author: Browne, Culligan and Phillips (2013) — Size: 2801 words — The New General Service List (NGSL), an update of the GSL, is a list of 2801 words which comprise the most important high-frequency words in English, giving the highest possible coverage with the fewest possible words. Not to be confused with the new-GSL (below), also developed in 2013, the NGSL gives over 90% coverage of the corpus used. The NGSL was generated from a corpus of 273 million words, 100 times larger than that used for the GSL. Presents only inflected forms, not word families. Used as the basis for other lists, e.g. NAWL. Has yet to have the same influence as the GSL. — Examples: the, be, and, of, to, a, in, have, it, you |

| New-General Service List (new-GSL) |

Author: Brezina and Gablasova (2013) — Size: 2494 words — The new-General Service List (new-GSL), an update of the GSL, is a list of 2494 words drawn from four different corpora with a total size of 12 billion words. Not to be confused with the NGSL (above), also developed in 2013, the new-GSL gives around 80% coverage of the corpora used, similar to the GSL, though with fewer words overall, 2494 compared to approximately 4100 for the GSL. The 2494 words comprise a core list of 2122 words, which had a similar rank in all four corpora, plus 378 words which were common in the two more recent corpora. Like the NGSL, it uses lemmas i.e. inflected forms, not word families. Does not (yet) appear to have been used as the basis for other lists, and is yet to have the same influence as the GSL. — Examples: the, be, of, and, a, in, to, have, that, to |

Academic single word lists: general purpose

The following are the general academic word lists mentioned earlier.

| Word list | About |

| University Word List (UWL) |

Author: Xue and Nation (1984) — Size: 836 word families — One of the first widely used academic word lists, the UWL contains 836 word families divided into levels based on frequency. It excludes words from the GSL, and gives coverage of 8.5% of academic texts. Now largely replaced by the AWL. — Examples: alternative, analyze, approach, arbitrary, assess, assign, assume, compensate, complex, comply |

| Academic Word List (AWL) |

Author: Coxhead (2000) — Size: 570 word families — Perhaps the most widely known and used academic word list, the AWL is a list of 570 word families that are not included in the GSL but which appear frequently in academic texts, across a range of disciplines. Divided into 10 sublists based on frequency. It was designed to be an improvement on the UWL, and covers around 10% of words in academic texts: a similar amount to the UWL, but using far fewer word families. — Examples: analyse, approach, area, assess, assume, authority, available, benefit, concept, consist |

| Academic Keyword List (AKL) |

Author: Paquot (2010) — Size: 930 words — The Academic Keyword List (AKL) consists of 930 words which appear more frequently in academic texts than non-academic ones. This tendency is called keyness, which leads to the name of the list, since it identifies keywords in academic (vs. non-academic) texts (the AVL, below, uses a similar principle to select words). As such, the AKL does not exclude words from the GSL. 49.6% of words in the AKL appear in the GSL, 38.7% in the AWL, while 11.7% appear in neither list. — Example words: ability, absence, account, achievement, act, accept, account (for), absolute, above, according to |

| New Academic Word List (NAWL) |

Author: Browne, Culligan and Phillips (2013) — Size: 963 words — The New Academic Word List (NAWL) is a list of words that frequently appear in academic texts, but which are not contained in the New General Service List (NGSL) (by the same authors). The NGSL and NAWL in combination give 92% coverage of words (86% for the NGSL and 6% for the NAWL). The NAWL differs from the AWL in that it is more up-to-date, using the NGSL rather than the much older GSL as a basis. Additionally, it uses only inflected forms or variant spellings of words, rather than whole word families, meaning that although it has more headwords than the AWL (963 compared to 570), it has fewer word forms overall (2604 compared to 3112). — Example words: repertoire, obtain, distribution, parameter, aspect, dynamic, impact, domain, publish, denote. |

| Academic Vocabulary List (AVL) |

Author: Gardner and Davies (2013) — Size: 3015 words — The AVL is a list of 3015 academic words derived from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). The list excludes general high-frequency words as well as subject-specific (technical) words, though not by directly excluding any existing list. Key features of the list are ratio (words needed to occur 1.5 times as often in academic texts as in non-academic ones), range (words needed to occur frequently in at least seven of nine academic disciplines), dispersion (words needed to be evenly dispersed among the disciplines) and discipline measure (words could not occur more than three times the expected frequency in any of the disciplines). Like the NAWL and in contrast to the AWL, the AVL is based on words and inflected forms, not word families. — Example words: study, group, system, social, provide, however, research, level, result, include. |

Academic single word lists: field-specific

The following are the field-specific lists mentioned earlier.

| Word list | About |

| Science Word List (SWL) |

Author: Coxhead and Hirsh (2007) — Size: 318 word families — The Science Word List (SWL) provides a list of 318 word families which do not occur in the GSL or AWL but which occur with reasonable frequency and range in written science texts. The authors found that the GSL and AWL in combination give only 80% coverage of science texts, compared to 86.7% for Art, 88.8% for Commerce and 88.5% for Law. The 318 word families in the SWL make up for this shortfall, and provide an extra coverage of 3.79% of the science corpus used to derive the list. In comparison, the SWL gives only 0.61% coverage of an Arts corpus, 0.54% for Commerce and 0.34% for Law, demonstrating that it is a true science list. The SWL is divided into sublists based on frequency, in a similar way to the AWL. It contains 6 sublists, with the first 5 each containing 60 word families, and the last containing 18. — Example words: cell, species, acid, muscle, protein, molecule, nutrient, dense, laboratory, ion. |

| Business Word List #1 (BWL#1) |

Author: Konstantakis (2007) — Size: 560 word families — This is the first of two lists called Business Word List (BWL); the second is considered later. To compile the list, the author used a corpus of 33 popular Business English course books published between 1986 and 1996. The list consists of 560 word families, comprising 480 word families selected according to range (needed to occur in at least five of the text books), supplemented by a further 80 word families selected for frequency (needed to appear at least 10 times). The list excludes GSL and AWL words, and therefore provides a third, more specialised and business-oriented list for students. The BWL provided 2.79% coverage of the texts. A separate list of common abbreviations was compiled, which added a further 0.30% coverage. These two lists, together with the GSL and AWL, provided 93.47% coverage, although the author noted that, if proper names and nationalities were included (e.g. London, Mexican), the coverage reached 95.65%, which is above the 95% minimum comprehension threshold. The list is presented in alphabetical order, without frequencies. — Example words: above-mentioned, accessories, acid, adverse, aerospace, after-sales, agenda, aggressive, aircraft, airline. |

| Pharmacology Word List (PWL) |

Author: Fraser (2007) — Size: 601 word families — The PWL is intended to provide a list of words which are common in the field of pharmacology, but which are not contained in the GSL or AWL. The PWL gives around 13% coverage of pharmacology journal articles, and 15% coverage of pharmacology textbooks. — Example words: abbreviation, abnormality, abolish, absorb, abuse, accumbens, acetonitrile, acetate, acetylcholine, acid. |

| Medical Academic Word List (MAWL) |

Author: Wang, Liang, and Ge (2008) — Size: 623 word families — The Medical Academic Word List (MAWL) was developed from a study of a 1.09 million-word corpus of medical research articles from online resources. It contains 623 word families, and has a coverage of 12.24% of words in the corpus. The MAWL was developed in a similar way to the AWL (Academic Word List), by first eliminating words from the GSL (General Service List). In addition, members of the word family needed to occur in at least half of the 32 subject areas of the corpus, and occur at least 30 times in the corpus. It provides an alternative to the AWL for medical students. — Example words: cell, data, muscular, significant, clinic, analyze, respond, factor, method, protein. |

| AgroCorpus List |

Author: Martínez, Beck, and Panza (2009) — Size: 92 word families — The AgroCorpus List is a subset of the AWL, and consists of the word families that were found to be most frequent in an 826,416-word corpus of agriculture research articles. — Example words: environmental, accumulation, region, variation, chemical. |

| Basic Engineering List (BEL) |

Author: Ward (2009) — Size: 299 words — The Basic Engineering List (BEL), developed from a corpus of 250,000 words from 25 engineering textbooks, is intended to serve as a foundation for students in reading English language engineering textbooks. The list is purposely short and non-technical in nature, and focuses on word types rather than lemmas or families in order to encourage a focus on individual words. — Examples words: system, calculate, value, flow, process, column, factors. |

| Business Word List #2 (BWL#2) |

Author: Hsu (2011) — Size: 426 word families — This is the second of two lists called Business Word List (BWL); the first is considered above. This BWL gives 426 word families which occur frequently in business texts, but which are not general words. This list used a different approach to other specialist lists, by excluding the first 3000 word families from the BNC (British National Corpus), rather than excluding other word lists. The author used a corpus which consisted of business research articles across 20 business subject areas. The word families were chosen by range and frequency in the corpus and accounted for 5.66% of words. The words in the BWL are listed according to which 1000 word section of the BNC they appear in (BNC 4th 1000, BNC 5th 1000, etc.), then by frequency in the business corpus. Range (number of articles they occur in) is also given. As such, this BWL is more detailed than the first one. — Example words: asset, audit, statistic, review, transact, network, database, acquire, interact, construct |

| CSWL (Computer Science Word List) |

Author: Minshall (2013) — Size: 433 word families — This Computer Science Word List (CSWL) was designed for use by non-native English speakers studying computer science in UK universities. It was developed from a corpus of 3.66 million words from journal articles and conference proceedings covering 10 sub-disciplines of computer science as defined by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM). In combination with the GSL and AWL, the CSWL gave 95.11% coverage of the corpus. — Example words: accelerate, activate, acyclic, adversary, affine, afore, algebra, algorithm, align, alphabet. |

| CAWL (Chemistry Academic Word List) |

Author: Valipouri and Nassaji (2013) — Size: 1400 word families — The Chemistry Academic Word List (CAWL) was developed for EFL graduate Chemistry students. It comprises word families which occur frequently in Chemistry research articles. It includes both general and academic words, since many high frequency words have different meanings, frequencies and collocations in specialist contexts. Of the 1400 word families in the CAWL, 683 are from the GSL, 327 are from the AWL, while the remaining 390 occur in neither list. In total, the CAWL gives 81.18% coverage of the CRAC (Chemistry Research Article Corpus) used to derive the list. — Example words: use, show, react, results, solve, spectrum, can, form, temperature, high. |

| Medical Academic Vocabulary List (MAVL) |

Author: Lei and Liu (2015) — Size: 819 words — The Medical Academic Vocabulary List (MAVL) was developed based on a study of a 2.7 million-word corpus of medical academic English and a 3.5 million-word corpus of medical English textbooks. The coverage of the MAVL in the two corpuses was 19.44% and 20.18% respectively. The MAVL can be contrasted with the earlier Medical Academic Word List (MAWL), developed in 2008, in four ways. First, unlike the MAWL, which used only medical academic English texts, the MAVL used both medical academic English texts alongside medical English textbooks to develop the list. Second, unlike the MAWL, the MAVL did not exclude high frequency (general) words. Third, the MAVL is lemma-based not word family based. Fourth, it provides greater coverage, with the MAVL covering 19.44% of words in medical academic English texts, compared to 10.52% for the MAWL, and 20.18% of words in medical English textbooks, in contrast to 12.97% for the MAWL. — Example words: abdominal, ability, abnormal, abnormality, absence, absent, absolute, absorption, accord, accumulate. |

| NAWL (Nursing Academic Word List) |

Author: 2015 — Size: 676 word families — The Nursing Academic Word List (NAWL) contains the most frequent nursing words in a one million word corpus (called the NRAC) consisting of 252 English online nursing research articles. It is intended for graduate nursing students who need to read and publish nursing articles in English. The NAWL covers 13.64% of the NRAC. Not to be confused with the New Academic Word List (above), also abbreviated NAWL. — |

| Environmental Academic Word List (EAWL) |

Author: Liu and Han (2015) — Size: 458 word families — Not to be confused with the Economics Academic Word List, also abbreviated, EAWL (below), the Environmental Academic Word List (EAWL) is intended for environmental science learners. The list gives 15.43% coverage of the 862,242 word corpus used to derive the list, compared to 12.82% for the AWL. — |

| Economics Academic Word List (EAWL) |

Author: O’Flynn (2020) — Size: 887 words — The Economics Academic Word List (EAWL) is a list of words which frequently appear in economics texts, but which are not contained in the New General Service List (NGSL). The 887 words of the EAWL are divided into 9 sublists based on frequency. The EAWL, which, like the NGSL, is lemma-based, makes up around 5.5% of the words in university economics texts in English, based on a corpus study of texts ranging from economics journal articles to economics dissertations. Not to be confused with the Environmental Academic Word List, also abbreviated, EAWL (above). — Example words: administrative, aggregate, agriculture, allocation, aspect, audit, authority, best, better, calculation. |

| Computer Science Academic Vocabulary List (CSAVL) |

Author: Roesler (2021) — Size: 1606 words — The Computer Science Academic Vocabulary List (CSAVL) comprises two lists for use by Computer Science undergraduate students in the US. The first list gives 904 words, while the second supplementary list, CSAVL-S, gives more technical words. Words were chosen by frequency, range, dispersion and other criteria from a corpus of Computer Science textbooks and journal articles, and together give 19.90% coverage of a second corpus used to evaluate the list. This list, which is a stand-alone list, contrasts with the CSWL, which is intended as a third, supplementary list to the GSL and AWL. — Example words: system, data, algorithm, such, base, node, model, case, program, information. |

Technical single word lists

There are two important technical lists, both for school age students, which use the similar methodology to derive them as the other lists

on this page.

| Word list | About |

| Middle School Vocabulary Lists (MSVL) |

Author: Greene and Coxhead (2015) — Size: 600-800 word families per subject — The Middle School Vocabulary Lists (MSVL) are a series of lists developed in 2015 by Greene and Coxhead, covering English, Health, Mathematics, Science, and Social Science/History. The lists were developed from a corpus of 109 textbooks for grades 6-8 (11-14 years old). Like the AWL, the MSVL excludes words from the GSL and uses a word family approach. Text coverage of the lists is between 5.83% (Social Studies/History) and 10.17% (Science). — Example words [Health]: drug, physical, alcohol, stress, goal Example words [Mathematics]: equate, graph, area, fraction, chapter. |

| Secondary School Vocabulary Lists (SVL) |

Author: Green and Lambert (2018) — Size: Varies, from 253 words (Mathematics) to 880 words (Biology) — The Secondary School Vocabulary Lists (SVL) is a series of lists of discipline-specific words for secondary school education, covering eight core subjects: Biology, Chemistry, Economics, English, Geology, History, Mathematics, and Physics. The list was devised using methods similar to those used to create the AVL and the MAVL. The SVL does not present a single list. Rather, it comprises three different types of word list for eight different subjects, and therefore presents 24 lists in total. The three different list types are: lemma lists (sorted by frequency); word family lists (also sorted by frequency, of all words in the family); and collocation lists (the most common 10 word associations for each). — Example words [Biology]: cell, blood, plant, enzyme, molecule. Example words [Economics]: price, cost, demand, rate, firm. |

Academic multi-word lists: general purpose

The following are the general academic multi-word lists mentioned earlier.

| Word list | About |

| Academic Formulas List (AFL) |

Author: Simpson-Vlach and Ellis (2009) — Size: 607 formulas — The Academic Formulas List (AFL) contains the most common formulaic sequences in academic English, i.e. recurring word sequences three to five words long. There are three separate lists: one for formulas that are common in both academic spoken and academic written language (the core AFL, 207 entries), one for formulas which are used frequently in academic spoken English (200 entries), and one for those which are used frequently in academic written English (also 200 entries). — Examples [core]: in terms of, at the same time, from the point of view, in order to Examples [spoken]: be able to, blah blah blah, this is the, you know what I mean Examples [written]: on the other hand, due to the fact that, it should be noted |

| Academic Collocation List (ACL) |

Author: Ackermann and Chen (2013) — Size: 2469 collocations — The Academic Collocation List (ACL) contains 2469 of the most frequent and useful collocations which occur in written academic English. It was developed using the Pearson International Corpus of Academic English (PICAE), with advice from English teaching experts to ensure the collocations chosen would be useful to students of English. The ACL gives around 1.4% coverage of words in academic English, in contrast to only 0.1% coverage for a general corpus. — Example collocations: cognitive ability, abstract concept, sexual abuse, (in) academic circles, accept responsibility, allow access (to), brief account, great accuracy, achieve (a) goal, acquire knowledge. |

| Discourse Connectors List (DCL) |

Author: Rezvani Kalajahi, Neufeld and Abdullah (2017) — Size: 632 discourse connectors — The Discourse Connector List (DCL) classifies and describes 632 discourse connectors, ranking them by frequency in three different registers (academic, non-academic and spoken registers) in two different corpora, namely the BNC (British National Corpus) and COCA (Corpus of Contemporary American English). — Examples: and, or, as, if, when, also, however, after, even, because. |

| Academic Idioms list |

Author: Miller (2019) — Size: 170 idioms (spoken), 38 idioms (written) — The academic idioms list is derived from the British Academic Spoken English (BASE) corpus for spoken texts and the Oxford Corpus of Academic English (OCAE) corpus for written texts. Only idioms with a frequency of more than 1.2 per million words in the BASE corpus were included. Together the list accounts for approximately 0.1% of words in academic English. — Examples [written]: on the other hand, in (the) light of, on the one hand, in the hands of, bear in mind Examples [spoken]: the balance of power, at the end of the day, the bottom line, take on board, by and large |

Academic multi-word lists: field-specific

There appear to be no field-specific, academic multi-word lists at present.

Technical multi-word lists

The following are technical multi-word lists.

| Word list | About |

| Computer Science Multi-Word List (CSMWL) |

Author: Minshall (2013) — Size: 23 collocations — The Computer Science Multi-Word List (CSMWL) was developed by Minshall at the same time as the CSWL. It comprises only 23 items (listed in full below). — Complete list of CSMWL collocations: control flow graph, data flow, data mining, data set, data structure, data transfer, lower bound, flash memory, execution time, garbage collection, machine learning, operating system, polynomial time, response time, scratch pad, search engine, social network, software development, software engineer, steady state, upper bound, user interface, virtual machine. |

| Secondary Phrase Lists (SPL) |

Author: Green and Lambert (2018) — Size: Size varies according to list — The Secondary Phrase Lists (SPL) was developed by Green and Lambert at the same time as the SVL. It comprises collocations for the same eight subjects as covered by the SVL. — Example collocations [Biology]: carbon dioxide, amino acids, water potential, blood cells Example collocations [Economics]: demand curve, interest rate, supply curve, price level |

| Nursing Collocation List (NCL) |

Author: Mandić and Dankić (2020) — Size: 488 collocations — The Nursing Collocation List (NCL) is a list of 488 collocations which occur frequently in nursing journal articles. It was developed using the nursing scientific article corpus (NSAC), which consisted of 1.1 million words drawn from 262 nursing articles, from ten prominent nursing journals, all published in 2017 or 2018. The list includes only noun-adjective collocations (254, or 52.1% of the total) and noun-noun collocations (234, or 47.9%), since these are the most common in nursing articles. — Example collocations: alcohol abuse, open access, action research, acute care, medication adherence, chemotherapy administration, hospital admission, adverse effect, age group, significant amount. |

Overview

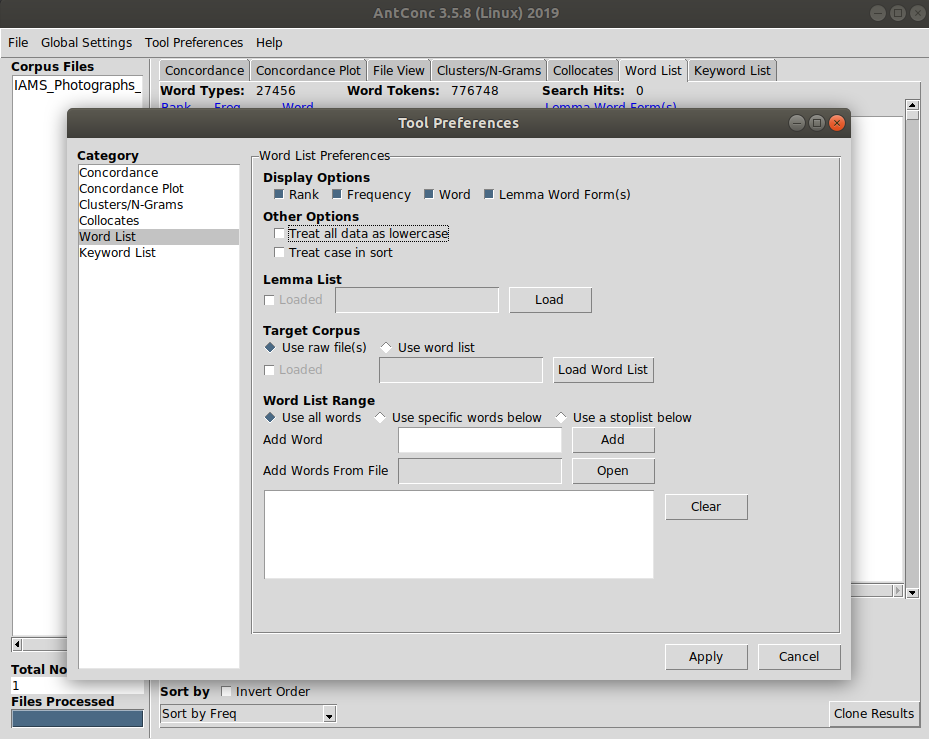

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

What are word lists in AntConc and when would you use it?

How do word lists work in AntConc?

How might I interpret word lists generated from catalogue data?

Objectives

Explain what word lists are in AntConc

Use word lists to start identifying the lingustic character of a corpus

Word lists

A word list counts how many times each word occurs in the selected text(s). Generally, in a word list we expect the most frequent words to be function words, e.g. for English-language texts, words like “the”, “of”, “and”, “but”, etc. However, for texts that are restricted by topic, genre and/or text type — which we would expect descriptive text in catalogue data to be — then the order of these words can vary and there will also be domain-specific vocabulary.

Word lists then are a useful starting point for getting an overview of the lingustic features of a corpus. For example, if you have a corpus that includes minor variations in data values — e.g. names of people, organisations, places, classification terms — creating a word list can be an effective way of spotting those variants. In the case of a large catalogue, it can also be useful for finding linguistic indicators of divergent practices within the corpus, which might indicate that entries were written by different people at different times, or those that some entries contain text quoted from third-party sources.

Making a word list

To use the ‘Word List’ function in AntConc, click on the Word List tab and press Start.

Antconc then returns the following information:

- The total number of words in the corpus (

Word Tokens). - The total number of unique words in the corpus, which is the vocabulary size of the corpus (

Word Types). - A ranking of every unique word type by its frequency in the corpus.

You will note that AntConc has treated all text as lowercase. Whilst this can be useful, it means that the word “cook” and the family name “Cook” are treated as the same word type in our count. Case sensitivity is also useful when examining curatorial voice, because knowing where words are used in relation to punctuation is a tell for features like sentence structure and length.

In AntConc you need to change case sensitivity settings for each tool individually. Change this now by going to Tool Preferences, choosing Word List, and unticking Treat all data as lowercase, and then pressing Apply. Back in the Word List tab hit Start again to see the difference.

What is a word?

Note here that depending on your dataset, an important setting is

Token DefinitionunderGlobal Settings(found in the top navbar). As we’ve seen, this defines what AntConc sees as a word, e.g. you need to specify that numbers, punctuation characters and symbols can be part of words in order for AntConc to see things like urls or other special characters that provide meaning (e.g. hashtags in tweets).

Interacting with a word list

There are a number of ways in which you can interact with your word list output:

First, turning to the Freq column you can select and highlight frequency values. If you click on an individual word, AntConc will move to the Concordance tab and plot a ‘concordance’ for that word: that is, a list that shows sentences that contain the word you clicked on. To test this choose a lower frequency word (ranked below 1000), click on it, and AntConc will move to the Concordance tab. We will look at concordances in the next episode. For now, move back to the Word List tab and observe that your results haven’t been lost.

Second, you can re-sort the output in the Word List tab using the options in the Sort by area. By default sorts in the Word List tab are set by rank, meaning that the most common word type is shown at the top, and the least common word type is shown at the bottom. The sort can be inverted by ticking Invert Order and pressing Start. Note that you are now presented with a long tail of infrequently used word types.

The sort can also be changed so that rather than sorting by the frequencty of words, the sort is made by the words themselves, listed in alphabetical order. To do this, untick Invert Order, select Sort by Word in the dropdown and hit Start. Browsing through an alphabetical sort can be a useful way of finding errors in the data (e.g. stray punctuation), spelling mistakes, variations in capitalisation, or — thinking of curatorial voice — different lemma forms of words.

Is AntConc thinking or has it crashed?

AntConc can often become non-functional. In most cases the software is processing your request rather than fallen over. For example, when looking at a word list it is ill-advised to click on a very frequent word as AntConc may take a while to process the concordance for that word. Of course, if a very frequent word is one your interested in, you’ll just have to be patient!

Saving your output

To save the output from your Word List go to the File menu in the navbar and select Save Output.

Good practice when saving outputs

All tabs in AntConc provide the option to save the output. This is vital for keeping a record of your findings. Note that the default output is a file called

antconc_results.txt. As this contains no information about your corpus, your query, your settings, or what version AntConc you are using, you are encourged to note that information in the output file name each time you save an output. The sad truth is that if you use the default name regularly, you may be more likely to overwrite previous results!

Browsing through the downloaded output can be instructive. In this case, we see many places and names. And as we get below the 500 most common words, some vocabulary choices that might benefit from further investigation: 132 occurrences of the word ‘poorish’ (used it turns out to describe the condition of photographs), 72 occurences of ‘Reconnaissances,’ (almost certainly the name of a secondary source regularly cited in the entry), and 64 occurences of ‘Hon’ble’ (likely text transcribed from a caption).

Tasks

Having learnt about the Word List tab in AntConc, work in pairs or small groups on the following challenges.

Task 1: What % of all word tokens are accounted for by the 30 most common word types?

- Use the

Word Listtab to count all word types and then use the output to make an estimate. Note: you may need to do some calculation outside of AntConc.Solution

- Remove any text from the search box, select

Sort by Freqand hitStart.- Observe the figure of

759930word tokens. Select the frequency values of the 30 most common word types, paste them into a spreadsheet programme, and sum them. You should get263874. Use these two figures to calculate a percentage:(263874/759930) x 100 = 34.72%

- It is common in English language corpora to find that roughly half the corpus is accounted for by a small number of frequent words. This observation goes a long way to explaining why corpus linguists often present and work with lists of ‘top’ words (not that word lists are the only tool in the corpus linguists armoury, as we shall see!). In this case, the slightly low percentage of all word tokens accounted for by the 30 most common word types may indicate a greater volume of frequently used words.

Task 2: What might the variant uses of the verb “enter” infer about language use in the dataset as a whole?

- Use the

Word Listtab to count all word types, then use the sorting options to help you navigate to variants of the verb “enter” and their use in context.Solution

- Remove any text from the search box, select

Sort by Wordand hitStart.- Browse to the string “enter”. There are six word varients of “enter” with frequencies as follows:

- enter: 15 (sum of “enter” and “enter.”)

- Entered: 1

- entered: 24 (sum of “entered” and “entered,”)

- Entering: 1

- entering : 18 (sum of “entering”, “entering,” and “entering.”)

- enters: 5

- An initial observation can be made that no one form of the verb “enter” dominates and the verb has several different meanings.

- The present tense form (“enter”) and active present participle form (“entering”) are typically used in relation to a visit/access to a site or to direct the gaze of a visitor/onlooker, such as in “The view shows that portion of the building immediately facing you as you enter the court”, “View of road entering gorge”. These forms appear in both curator/cataloguer descriptions and third-party text.

- The past tense form (“entered”) is often used to refer to people joining an army unit or a profession — “entered the Bengal Civil Service” — but also as archivist/compilor terminology — “The plates entered here also include photographs”.

- To explore the singular and plural uses of the verb, click on “enter”, “enters” or “entering” and look at the output in the

Concordancetab.

- Concordances are explained in more detail in a later episode.

- We can infer — pending further investigation — that the curatorial descriptions in the corpus describe a perspective/view upon someone entering or something being entered, and quote references to historical sources.

Task 3: Find the variants of the word “behind” and estimate their use relative to each other. Without looking at the concordances for these, discuss what hypotheses might explain this result.

- Use the

Word Listtab to count all word types and then use the output to make an estimate.Solution

- Remove any text from the search box, select

Sort by Wordand hitStart.- Browse to the string “behind”. There are two word variants in the corpus: “behind” and “Behind”. There are only 25 instances of “Behind” compared to 400 instances of “behind”. From these numbers we can infer a series of possible hypotheses about the corpus:

- There are very few instances of “Behind” being used at the start of a sentence. The low frequency of capitalised variants of prepositions, like “Behind”, may be indicate something about sentence length (because frequent capitalisation of prepositions may be an indicator of short sentence length).

- Out of 400 instances of non-capitalised “behind”, 41% of the prepositions appear before some sort of punctuation, such as the end of a clause or a sentence. “behind.” seems particularly high, and clicking on it gives us an insight into the peculiar way “behind” is used to close a sentence.

- Positional/spatial words might frequently be used at the end of sentences.

Key Points

Word lists are a way of getting an overview of the lingustic features of a corpus

AntConc provides a number of options for presenting word lists

When using AntConc to count things, we need to be mindful that machine readable strings are not the same as human readable words

Outputs from AntConc queries can be saved locally as text files

A word list (or lexicon) is a list of a language’s lexicon (generally sorted by frequency of occurrence either by levels or as a ranked list) within some given text corpus, serving the purpose of vocabulary acquisition. A lexicon sorted by frequency «provides a rational basis for making sure that learners get the best return for their vocabulary learning effort» (Nation 1997), but is mainly intended for course writers, not directly for learners. Frequency lists are also made for lexicographical purposes, serving as a sort of checklist to ensure that common words are not left out. Some major pitfalls are the corpus content, the corpus register, and the definition of «word». While word counting is a thousand years old, with still gigantic analysis done by hand in the mid-20th century, natural language electronic processing of large corpora such as movie subtitles (SUBTLEX megastudy) has accelerated the research field.

In computational linguistics, a frequency list is a sorted list of words (word types) together with their frequency, where frequency here usually means the number of occurrences in a given corpus, from which the rank can be derived as the position in the list.

| Type | Occurrences | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| the | 3,789,654 | 1st |

| he | 2,098,762 | 2nd |

| […] | ||

| king | 57,897 | 1,356th |

| boy | 56,975 | 1,357th |

| […] | ||

| stringyfy | 5 | 34,589th |

| […] | ||

| transducionalify | 1 | 123,567th |

MethodologyEdit

FactorsEdit

Nation (Nation 1997) noted the incredible help provided by computing capabilities, making corpus analysis much easier. He cited several key issues which influence the construction of frequency lists:

- corpus representativeness

- word frequency and range

- treatment of word families

- treatment of idioms and fixed expressions

- range of information

- various other criteria

CorporaEdit

Traditional written corpusEdit

Most of currently available studies are based on written text corpus, more easily available and easy to process.

SUBTLEX movementEdit

However, New et al. 2007 proposed to tap into the large number of subtitles available online to analyse large numbers of speeches. Brysbaert & New 2009 made a long critical evaluation of this traditional textual analysis approach, and support a move toward speech analysis and analysis of film subtitles available online. This has recently been followed by a handful of follow-up studies,[1] providing valuable frequency count analysis for various languages. Indeed, the SUBTLEX movement completed in five years full studies for French (New et al. 2007), American English (Brysbaert & New 2009; Brysbaert, New & Keuleers 2012), Dutch (Keuleers & New 2010), Chinese (Cai & Brysbaert 2010), Spanish (Cuetos et al. 2011), Greek (Dimitropoulou et al. 2010), Vietnamese (Pham, Bolger & Baayen 2011), Brazil Portuguese (Tang 2012) and Portugal Portuguese (Soares et al. 2015), Albanian (Avdyli & Cuetos 2013), Polish (Mandera et al. 2014) and Catalan (2019[2]). SUBTLEX-IT (2015) provides raw data only.[1]

Lexical unitEdit

In any case, the basic «word» unit should be defined. For Latin scripts, words are usually one or several characters separated either by spaces or punctuation. But exceptions can arise, such as English «can’t», French «aujourd’hui», or idioms. It may also be preferable to group words of a word family under the representation of its base word. Thus, possible, impossible, possibility are words of the same word family, represented by the base word *possib*. For statistical purpose, all these words are summed up under the base word form *possib*, allowing the ranking of a concept and form occurrence. Moreover, other languages may present specific difficulties. Such is the case of Chinese, which does not use spaces between words, and where a specified chain of several characters can be interpreted as either a phrase of unique-character words, or as a multi-character word.

StatisticsEdit

It seems that Zipf’s law holds for frequency lists drawn from longer texts of any natural language. Frequency lists are a useful tool when building an electronic dictionary, which is a prerequisite for a wide range of applications in computational linguistics.

German linguists define the Häufigkeitsklasse (frequency class) of an item in the list using the base 2 logarithm of the ratio between its frequency and the frequency of the most frequent item. The most common item belongs to frequency class 0 (zero) and any item that is approximately half as frequent belongs in class 1. In the example list above, the misspelled word outragious has a ratio of 76/3789654 and belongs in class 16.

where is the floor function.

Frequency lists, together with semantic networks, are used to identify the least common, specialized terms to be replaced by their hypernyms in a process of semantic compression.

PedagogyEdit

Those lists are not intended to be given directly to students, but rather to serve as a guideline for teachers and textbook authors (Nation 1997). Paul Nation’s modern language teaching summary encourages first to «move from high frequency vocabulary and special purposes [thematic] vocabulary to low frequency vocabulary, then to teach learners strategies to sustain autonomous vocabulary expansion» (Nation 2006).

Effects of words frequencyEdit

Word frequency is known to have various effects (Brysbaert et al. 2011; Rudell 1993). Memorization is positively affected by higher word frequency, likely because the learner is subject to more exposures (Laufer 1997). Lexical access is positively influenced by high word frequency, a phenomenon called word frequency effect (Segui et al.). The effect of word frequency is related to the effect of age-of-acquisition, the age at which the word was learned.

LanguagesEdit

Below is a review of available resources.

EnglishEdit

Word counting dates back to Hellenistic time. Thorndike & Lorge, assisted by their colleagues, counted 18,000,000 running words to provide the first large-scale frequency list in 1944, before modern computers made such projects far easier (Nation 1997).

Traditional listsEdit

These all suffer from their age. In particular, words relating to technology, such as «blog,» which, in 2014, was #7665 in frequency[3] in the Corpus of Contemporary American English,[4] was first attested to in 1999,[5][6][7] and does not appear in any of these three lists.

- The Teachers Word Book of 30,000 words (Thorndike and Lorge, 1944)

The TWB contains 30,000 lemmas or ~13,000 word families (Goulden, Nation and Read, 1990). A corpus of 18 million written words was hand analysed. The size of its source corpus increased its usefulness, but its age, and language changes, have reduced its applicability (Nation 1997).

- The General Service List (West, 1953)

The GSL contains 2,000 headwords divided into two sets of 1,000 words. A corpus of 5 million written words was analyzed in the 1940s. The rate of occurrence (%) for different meanings, and parts of speech, of the headword are provided. Various criteria, other than frequence and range, were carefully applied to the corpus. Thus, despite its age, some errors, and its corpus being entirely written text, it is still an excellent database of word frequency, frequency of meanings, and reduction of noise (Nation 1997). This list was updated in 2013 by Dr. Charles Browne, Dr. Brent Culligan and Joseph Phillips as the New General Service List.

- The American Heritage Word Frequency Book (Carroll, Davies and Richman, 1971)

A corpus of 5 million running words, from written texts used in United States schools (various grades, various subject areas). Its value is in its focus on school teaching materials, and its tagging of words by the frequency of each word, in each of the school grade, and in each of the subject areas (Nation 1997).

- The Brown (Francis and Kucera, 1982) LOB and related corpora

These now contain 1 million words from a written corpus representing different dialects of English. These sources are used to produce frequency lists (Nation 1997).

FrenchEdit

- Traditional datasets

A review has been made by New & Pallier.

An attempt was made in the 1950s–60s with the Français fondamental. It includes the F.F.1 list with 1,500 high-frequency words, completed by a later F.F.2 list with 1,700 mid-frequency words, and the most used syntax rules.[8] It is claimed that 70 grammatical words constitute 50% of the communicatives sentence,[9] while 3,680 words make about 95~98% of coverage.[10] A list of 3,000 frequent words is available.[11]

The French Ministry of the Education also provide a ranked list of the 1,500 most frequent word families, provided by the lexicologue Étienne Brunet.[12] Jean Baudot made a study on the model of the American Brown study, entitled «Fréquences d’utilisation des mots en français écrit contemporain».[13]

More recently, the project Lexique3 provides 142,000 French words, with orthography, phonetic, syllabation, part of speech, gender, number of occurrence in the source corpus, frequency rank, associated lexemes, etc., available under an open license CC-by-sa-4.0.[14]

- Subtlex

This Lexique3 is a continuous study from which originate the Subtlex movement cited above. New et al. 2007 made a completely new counting based on online film subtitles.

SpanishEdit

There have been several studies of Spanish word frequency (Cuetos et al. 2011).[15]

ChineseEdit

Chinese corpora have long been studied from the perspective of frequency lists. The historical way to learn Chinese vocabulary is based on characters frequency (Allanic 2003). American sinologist John DeFrancis mentioned its importance for Chinese as a foreign language learning and teaching in Why Johnny Can’t Read Chinese (DeFrancis 1966). As a frequency toolkit, Da (Da 1998) and the Taiwanese Ministry of Education (TME 1997) provided large databases with frequency ranks for characters and words. The HSK list of 8,848 high and medium frequency words in the People’s Republic of China, and the Republic of China (Taiwan)’s TOP list of about 8,600 common traditional Chinese words are two other lists displaying common Chinese words and characters. Following the SUBTLEX movement, Cai & Brysbaert 2010 recently made a rich study of Chinese word and character frequencies.

OtherEdit

Most frequently used words in different languages based on Wikipedia or combined corpora.[16]

See alsoEdit

- Letter frequency

- Most common words in English

- Long tail

- Google Ngram Viewer – shows changes in word/phrase frequency (and relative frequency) over time

NotesEdit

- ^ a b «Crr » Subtitle Word Frequencies».

- ^ Boada, Roger; Guasch, Marc; Haro, Juan; Demestre, Josep; Ferré, Pilar (1 February 2020). «SUBTLEX-CAT: Subtitle word frequencies and contextual diversity for Catalan». Behavior Research Methods. 52 (1): 360–375. doi:10.3758/s13428-019-01233-1. ISSN 1554-3528. PMID 30895456. S2CID 84843788.

- ^ «Words and phrases: Frequency, genres, collocates, concordances, synonyms, and WordNet».

- ^ «Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA)».

- ^ «It’s the links, stupid». The Economist. 20 April 2006. Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- ^ Merholz, Peter (1999). «Peterme.com». Internet Archive. Archived from the original on 1999-10-13. Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- ^ Kottke, Jason (26 August 2003). «kottke.org». Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- ^ «Le français fondamental». Archived from the original on 2010-07-04.

- ^ Ouzoulias, André (2004), Comprendre et aider les enfants en difficulté scolaire: Le Vocabulaire fondamental, 70 mots essentiels (PDF), Retz — Citing V.A.C Henmon

- ^ «Generalities».

- ^ «PDF 3000 French words».

- ^ «Maitrise de la langue à l’école: Vocabulaire». Ministère de l’éducation nationale.

- ^ Baudot, J. (1992), Fréquences d’utilisation des mots en français écrit contemporain, Presses de L’Université, ISBN 978-2-7606-1563-2

- ^ «Lexique».

- ^ «Spanish word frequency lists». Vocabularywiki.pbworks.com.

- ^ Most frequently used words in different languages, ezglot

ReferencesEdit

Theoretical conceptsEdit

- Nation, P. (1997), «Vocabulary size, text coverage, and word lists», in Schmitt; McCarthy (eds.), Vocabulary: Description, Acquisition and Pedagogy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 6–19, ISBN 978-0-521-58551-4

- Laufer, B. (1997), «What’s in a word that makes it hard or easy? Some intralexical factors that affect the learning of words.», Vocabulary: Description, Acquisition and Pedagogy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 140–155, ISBN 9780521585514

- Nation, P. (2006), «Language Education — Vocabulary», Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, Oxford: 494–499, doi:10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/00678-7, ISBN 9780080448541.

- Brysbaert, Marc; Buchmeier, Matthias; Conrad, Markus; Jacobs, Arthur M.; Bölte, Jens; Böhl, Andrea (2011). «The word frequency effect: a review of recent developments and implications for the choice of frequency estimates in German». Experimental Psychology. 58 (5): 412–424. doi:10.1027/1618-3169/a000123. PMID 21768069. database

- Rudell, A.P. (1993), «Frequency of word usage and perceived word difficulty : Ratings of Kucera and Francis words», Most, vol. 25, pp. 455–463

- Segui, J.; Mehler, Jacques; Frauenfelder, Uli; Morton, John (1982), «The word frequency effect and lexical access», Neuropsychologia, 20 (6): 615–627, doi:10.1016/0028-3932(82)90061-6, PMID 7162585, S2CID 39694258

- Meier, Helmut (1967), Deutsche Sprachstatistik, Hildesheim: Olms (frequency list of German words)

- DeFrancis, John (1966), Why Johnny can’t read Chinese (PDF)

- Allanic, Bernard (2003), The corpus of characters and their pedagogical aspect in ancient and contemporary China (fr: Les corpus de caractères et leur dimension pédagogique dans la Chine ancienne et contemporaine) (These de doctorat), Paris: INALCO

Written texts-based databasesEdit

- Da, Jun (1998), Jun Da: Chinese text computing, retrieved 2010-08-21.

- Taiwan Ministry of Education (1997), 八十六年常用語詞調查報告書, retrieved 2010-08-21.

- New, Boris; Pallier, Christophe, Manuel de Lexique 3 (in French) (3.01 ed.).

- Gimenes, Manuel; New, Boris (2016), «Worldlex: Twitter and blog word frequencies for 66 languages», Behavior Research Methods, 48 (3): 963–972, doi:10.3758/s13428-015-0621-0, ISSN 1554-3528, PMID 26170053.

SUBTLEX movementEdit