- Popular

This article is about the place of counseling in the church.

Source: The Monthly Record, 2009. 2 pages.

The Therapy of the Word

Over the last decade, one of the growth industries within the church has been that of counseling. Various models of counseling are on offer out there in the theological marketplace, some obviously laced through with secular psychology, others more self-consciously based upon biblical principles. I have neither the time nor space nor interest to offer critiques and assessments of the material content of these various approaches; what interests me at this point is the phenomenon of such counseling.

The origins of biblical counseling arguably lie in the seventeenth century, when Catholic and Protestant theologians produced books of cases of conscience, i.e., books which took specific moral questions (‘Should I gamble?’, ‘Is it legitimate to be in business with a non-Christian partner?’, ‘Can I lend money at interest?’, etc.) and provided biblically grounded answers to them. In other words, they took general biblical principles and tried to apply them to specific situations.

That is the basic principle which holds today. Although many of the specific questions have changed (‘Should I sharpen my sword on a Sunday?’ is not a pressing concern for most Christians today), the basic idea is the same: individual Christians have specific problems; counseling seeks to address those problems by applying biblical principles. So far, so good.

What intrigues me, however, is the veritable explosion in interest in the area over recent years, an interest that sparks two questions in my mind: is this current Christian fascination with counseling simply the priorities of the world around dressed up in a Christian idiom? And what does this say about the nature of church?

I have not time to address the former question here; suffice to say that I suspect it is not susceptible to a simple answer. It is also intimately connected to the way one answers the second. What is interesting is that scripture says very little about the kind of one-to-one application of the Word which biblical counseling represents; rather, the focus in the New Testament (and, indeed, in the Old) is upon the Word of God coming to the people as a whole and impacting the community of believers as a whole. When Paul preaches in Acts, he speaks in specific contexts; but he does not engage in micro-applications to every one of his hearers, or even, on the whole, to obvious subsets within the crowds who listen to him. The same can be said of his letters, although here there are frequent applications towards the end to specific groups (widows, young men, etc.) and even on occasion to specific people (Euodia and Syntyche, etc.). But the burden of his ministry and the vast majority of sentences in his letters are devoted to expounding the Word of God in the most general and glorious terms. He seems confident that the Word will find its own application as it is preached, and that is because what he proclaims is not simply information but the very speech of God, which transforms that with which it comes into contact. Thus he does not need to overload on specific instances of how the Word should be applied to specific people or situations. This is also one of the reasons why what he says is of perennial relevance: it does not date or fade away as the generation to whom it was originally addressed dies out.

All of this leads me to ask the obvious question: does the rise in biblical counseling, and the growth in the number of biblical counselors, signal a crisis in confidence not simply in the pulpit but in the Word of God to achieve its purpose? Now, do not misunderstand me: I am not saying that counseling has no place, nor small group; but surely, if the biblical pattern is representative of healthy church life, then 95% of the problems addressed by counseling should actually be addressed and solved by simply proclaiming the perennial Word of God. Is it perhaps the case that fewer people would need counseling if more people actually listened prayerfully to what their pastors were telling them from the pulpit every Sunday morning?

Next time you find yourself in need of counseling, ask yourself: is this the result of exceptional and unforeseen circumstances that require peculiar wisdom and sensitivity which can only be found in one-to-one discussion with another Christian? Or have I screwed up because I haven’t been paying attention to what the pastor has been preaching these many months?

Review

. 2020 Dec;57(6):741-752.

doi: 10.1177/1363461519853652.

Epub 2019 Jun 10.

Affiliations

-

PMID:

31180296

-

DOI:

10.1177/1363461519853652

Review

Therapy of the word and other psychotherapeutic approaches in Ancient Greek medicine

Chiara Thumiger.

Transcult Psychiatry.

2020 Dec.

Abstract

One of the most distinctive aspects of contemporary psychiatry is its firm grounding in a neurological and biochemical framework for the interpretation of mental life and its disturbances. In the absence of any strong neurological understanding or systematic knowledge of active pharmaceutical substances, one might expect that early ancient medicine readily resorted to non-somatic approaches to healing mental suffering. Instead, what is usually labelled «therapy of the word» and other forms of what one may call psychotherapy emerge relatively late in Greek medicine, only in the first centuries of our era. This paper provides an overview and analysis of this development in ancient history of psychology, philosophy and medicine, covering a broad period of time from the fifth century BCE to the end of the late-antique period, the fifth century CE. The focus is on the very idea (or lack thereof) of the curability of mental disturbance, and on the particular branch of therapeutics which addresses the psychological and existential condition of the patient, rather than his or her physiological state.

Keywords:

Ancient medicine; Galen; Hippocrates; ethics; psychotherapy; therapy of the world.

Similar articles

-

Medicine and psychiatry in Western culture: among Ancient Greek myths and modern prejudices.

Fornaro M, Clementi N, Fornaro P.

Fornaro M, et al.

Med Secoli. 2009;21(3):1105-22.

Med Secoli. 2009.PMID: 21560777

-

The History of Greek Psychiatry through the texts of those who have shaped it.

Christodoulou GN, Ploumpidis DN, Karavatos A.

Christodoulou GN, et al.

Psychiatriki. 2011 Jul-Sep;22(3):191-4.

Psychiatriki. 2011.PMID: 21971194

English, Greek, Modern.

No abstract available. -

[Concept of insanity in classical Greece].

La Croce E.

La Croce E.

Acta Psiquiatr Psicol Am Lat. 1981 Sep-Nov;27(4-5):285-91.

Acta Psiquiatr Psicol Am Lat. 1981.PMID: 6753499

Spanish.

-

Hippocrates, Galen, and the uses of trepanation in the ancient classical world.

Missios S.

Missios S.

Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23(1):E11. doi: 10.3171/foc.2007.23.1.11.

Neurosurg Focus. 2007.PMID: 17961050

Review.

-

The Greek (Hellenic) rheumatology over the years: from ancient to modern times.

Sakkas LI, Tronzas P.

Sakkas LI, et al.

Rheumatol Int. 2019 Jun;39(6):947-955. doi: 10.1007/s00296-019-04261-4. Epub 2019 Feb 25.

Rheumatol Int. 2019.PMID: 30805680

Review.

Publication types

MeSH terms

LinkOut — more resources

-

Full Text Sources

- Atypon

-

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

January 10, 2009

3 min read

Communicating for behavior change.

ADD TOPIC TO EMAIL ALERTS

Receive an email when new articles are posted on

Please provide your email address to receive an email when new articles are posted on .

We were unable to process your request. Please try again later. If you continue to have this issue please contact customerservice@slackinc.com.

Hippocrates, the father of medicine, acknowledged that along with diagnosing

and prescribing treatment for diseases, the “therapy of the word” was

just as important a factor in providing medical care. It was just not what you

told patients they need to do, but how you engaged them in the conversation

about what they needed to do. Listening to their concerns was part of their

medical care.

As frustrating as it may be for all of us, patients don’t always follow

medical advice and often exhibit behaviors that are harmful to their overall

health and well-being.

|

|

We see patients who don’t take their medications as prescribed,

don’t get enough physical activity, don’t monitor their blood sugars

and who continue to smoke, eat unhealthy foods (too high in calories, fat,

sodium, etc) and engage in other unhealthy habits that we, as health care

professionals, want them to stop immediately.

We recognize that there may be serious health consequences if they

don’t and we feel somewhat responsible. After all, didn’t they come

to us for medical advice, so why don’t they follow it?

Telling patients what they should or shouldn’t do is not enough when it

comes to changing behavior. Behavior change requires more than knowledge (what

the medication is for) and competent skills (how to give an insulin injection).

Behavior change occurs only when patients want to change their behavior.

Patients, consciously or unconsciously, weigh both the advantages and

disadvantages of changing or continuing a current behavior.

For patients to adopt a new behavior, the reasons or motivation for changing

the current behavior have to become more important than the reasons for staying

the same. The reasons to change or adopt a specific behavior must become a

priority for change to occur.

In the process of deciding whether or not to adopt a new behavior or change

a behavior, ambivalence occurs. Exploring this ambivalence is a core skill in

motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing is a “directive

communication method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring

and resolving ambivalence.” Application of motivational interviewing

skills and communication techniques has been found to be especially effective

in facilitating behavior change.

Research has provided strong evidence that physician-patient interactions

can influence patient adoption of health-promoting behaviors. These

interactions are the basis of what commonly is known as a collaborative

patient-centered model of care as compared with the traditional compliance

model of care.

Two essential communication skills used in motivational interviewing are

asking open-ended questions and listening reflectively. These communication

techniques form the basis of understanding the patients’ ideas, attitudes

and feelings about changing a behavior.

Open-ended questions are a communication skill that can be effectively used

to explore motivation. The goal of open-ended inquiry is to obtain the

patient’s story. The goal is to be curious and to try to understand the

experience of the person and the meaning that the person attributes to that

experience. This may be very different from our training where we were taught

to gather information and facts.

To elicit the patient’s story, start with simple requests. For example,

“Tell me about how often you check your blood sugar at home.”

“What” and “How” questions are also effective, especially

as a follow-up question. For example, “How difficult is it for you to

check your blood sugars at work?” “Why” questions aren’t as

effective, since they may evoke defensiveness from the patient. For example,

“Why don’t you check your blood sugars more often?”

After you receive a reply, affirm the patients by validating their thoughts

and feelings. For example, “I appreciate your honesty in telling me your

concerns about checking your blood sugars at work.”

Listening reflectively is not just parroting back to the patient what you

have heard. You rephrase the patient’s statement to reflect what you think

you heard and what you think the patient meant. For example, “If I

understand what you are saying, you don’t like people at work knowing you

have diabetes and that you need to test your blood sugar, is that

correct?” This allows the patient to affirm or correct your understanding

of what they said.

At the end of the conversation, summarizing key points is helpful in

addressing discrepancy. Discrepancy exists when there is a conflict between

patients’ beliefs or behaviors and their actions. For example, “So I

hear you saying that managing your diabetes is very important to you, but that

not checking your blood sugar at work is more important.”

Another effective communication skill is expressing empathy. The evidence

for the effect of empathy as a communication tool for change is strongest.

Empathy helps develop patient rapport without being judgmental, critical or

blaming. Empathy stems from a sincere appreciation of the patients’

struggles and a genuine desire to understand their experience. For example,

“I can understand how taking your blood sugar at work may not be easy at

times, but I know you are interested in improving your diabetes

management.”

Most health care providers are not trained in communication skills and

techniques to encourage patient behavior change. These techniques require study

and a lot of practice. The following resources provide an excellent

introduction to behavior change and motivational interviewing.

Mary M. Austin, MA, RD, CDE, is Owner and President of The Austin Group,

LLC in Shelby Township, Mich., and is an Endocrine Today Editorial

Board member.

For more information:

- Rollnick S, Mason P, Butler C. Health Behavior Change: A Guide for

Practitioners. New York: Churchill Livingston; 1999.- Rollnick S, Mason P, Butler C. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care:

Helping Patients Change Behavior.New York: The Guilford Press; 2008.

ADD TOPIC TO EMAIL ALERTS

Receive an email when new articles are posted on

Please provide your email address to receive an email when new articles are posted on .

We were unable to process your request. Please try again later. If you continue to have this issue please contact customerservice@slackinc.com.

libcats.org

Главная →

The Therapy of the Word in Classical Antiquity

Pedro Laín Entralgo (author), L.J. Rather, John M. Sharp (editors and translators)

Ссылка удалена правообладателем

—-

The book removed at the request of the copyright holder.

Популярные книги за неделю:

#1

Ф.И.Бурдейный, Н.В.Казанский. Карманный справочник радиолюбителя-коротковолновика (1959, DjVu)

440 Kb

#2

Я.Войцеховский. Радиоэлектронные игрушки (1977, djvu)

13.76 Mb

#3

Подготовка саперов, подразделений специального назначения по разминированию

Категория: Научно-популярная литература (разное)

1.49 Mb

#4

128 советов начинающему программисту

Очков В.Ф., Пухначев Ю.В.

Категория: computers, computers, prog

8.91 Mb

#5

Английский язык в картинках

I.A. Richards; Christine M. Gibson

Категория: Иностранные языки

5.77 Mb

#6

Красота в изгнании. Королевы подиума

Александр Васильев

Категория: Исторические

21.01 Mb

#7

Ограждение участка. Ограды. Заборы. Калитки. Ворота

В.И.Рыженко

Категория: Строительство

1.23 Mb

#8

Эти загадочные зеркала

В. Правдивцев

Категория: Религия. Эзотерика

88.19 Mb

#9

Самоделки школьника

Тарасов Б.В.

Категория: science, science, technical, hobby, oddjob

41.91 Mb

#10

Наука и жизнь.Маленькие хитрости

Категория: E_Engineering, EM_Mechanics of elastic materials

3.50 Mb

Только что пользователи скачали эти книги:

#1

Краткий англо-русский технический словарь

None Provided

Категория: info, dict, science, technical, civil, society, lang

14.75 Mb

#2

Основы классической ТРИЗ. Руководство для изобретательного мышления

Орлов М.

3.28 Mb

#3

Английский язык в картинках

I.A. Richards; Christine M. Gibson

Категория: Иностранные языки

5.77 Mb

#4

Сборник рецептур блюд и кулинарных изделий

А.И. Здобнов, В.А. Цыганенко

Категория: house, , house, home, , house

34.26 Mb

#5

Основы классической ТРИЗ. Практическое руководство для изобретательного мышления

М. Орлов

Категория: ЧЕЛОВЕК

18.89 Mb

#6

Учебное пособие. Ремонт стартера

Категория: ТЕХНИКА, ХОББИ и РЕМЕСЛА

6.47 Mb

#7

История открытия логарифмов

Гиршвальд Л.Я.

Категория: Математика

1.67 Mb

#8

Очерки истории теории функций действительного переменного

Медведев Ф.A.

Категория: Математика

2.86 Mb

#9

Невропатология

Бадалян Л.О.

5.76 Mb

#10

Жак Адамар — легенда математики

Мазья В.Г., Шапошникова Т.О.

Категория: История

26.87 Mb

Writing therapy is a form of expressive therapy that uses the act of writing and processing the written word as therapy. Writing therapy posits that writing one’s feelings gradually eases feelings of emotional trauma.[1] Writing therapeutically can take place individually or in a group and it can be administered in person with a therapist or remotely through mailing or the Internet.

Writing therapy; relieving tension and emotion, establishing self-control and understanding the situation after words are transmitted on paper

The field of writing therapy includes many practitioners in a variety of settings. The therapy is usually administered by a therapist or counselor. Several interventions exist online. Writing group leaders also work in hospitals with patients dealing with mental and physical illnesses. In university departments they aid student self-awareness and self-development. When administered at a distance, it is useful for those who prefer to remain personally anonymous and are not ready to disclose their most private thoughts and anxieties in a face-to-face situation.

As with most forms of therapy, writing therapy is adapted and used to work with a wide range of psychoneurotic issues, including bereavement, desertion and abuse. Many of these interventions take the form of classes where clients write on specific themes chosen by their therapist or counsellor. Assignments may include writing unsent letters to selected individuals, alive or dead, followed by imagined replies from the recipient, or a dialogue with the recovering alcoholic’s bottle of alcohol.

Research into the therapeutic action of writingEdit

The expressive writing paradigmEdit

Expressive writing is a form of writing therapy developed primarily by James W. Pennebaker in the late 1980s. The seminal expressive writing study[2] instructed participants in the experimental group to write about a ‘past trauma’, expressing their very deepest thoughts and feelings surrounding it. In contrast, control participants were asked to write as objectively and factually as possible about neutral topics (e.g., a particular room or their plans for the day), without revealing their emotions or opinions. For both groups, the timescale was 15 minutes of continuous writing repeated over four consecutive days. It was also instructed that should a participant run out of things to write, they should go back to the beginning and repeat themselves, perhaps writing a little differently.

Typical writing instructions include:

For the next 4 days, I would like you to write your very deepest thoughts and feelings about the most traumatic experience of your entire life or an extremely important emotional issue that has affected you and your life. In your writing, I’d like you to really let go and explore your deepest emotions and thoughts. You might tie your topic to your relationships with others, including parents, lovers, friends, or relatives; to your past, your present or your future; or to who you have been, who you would like to be or who you are now. You may write about the same general issues or experiences on all days of writing or about different topics each day. All of your writing will be completely confidential.

Don’t worry about spelling, grammar or sentence structure. The only rule is that once you begin writing, you continue until the time is up.

Several measurements were made before and after, but the most striking finding was that relative to the control group, the experimental group made significantly fewer visits to a physician in the following months. Although many report being upset by the writing experience, they also find it valuable and meaningful.[3]: 167

Pennebaker has either written or co-written over 130 articles on expressive writing.[4] One of these suggested that expressive writing has the potential to actually ‘boost’ the immune system, perhaps explaining the reduction in physician visits.[5] This was shown by measuring lymphocyte response to the foreign mitogens phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) and concanavalin A (ConA) just prior to and 6 weeks after writing. The significantly increased lymphocyte response led to speculation that expressive writing enhances immunocompetence. The results of a preliminary study of 40 people diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder suggests that routinely engaging in expressive writing may be effective in reducing symptoms of depression.[6]

Reception and criticism of Pennebaker’s expressive writing theoriesEdit

Pennebaker’s experiments have been widely replicated and validated. Following on from Pennebaker’s original work, there has been a renewed interest in the therapeutic value of abreaction. This was first discussed by Josef Breuer and Freud in Studies on Hysteria but not much explored since.[citation needed] At the heart of Pennebaker’s theory is the idea that actively inhibiting thoughts and feelings about traumatic events requires effort, serves as a cumulative stressor on the body, and is associated with increased physiological activity, obsessive thinking or ruminating about the event, and longer-term disease.[3] However, as Baikie and Wilhelm note, the theory has intuitive appeal but mixed empirical support:

Studies have shown that expressive writing results in significant improvements in various biochemical markers of physical and immune functioning (Pennebaker et al, 1988; Esterling et al, 1994; Petrie et al, 1995; Booth et al, 1997). This suggests that written disclosure may reduce the physiological stress on the body caused by inhibition, although it does not necessarily mean that disinhibition is the causal mechanism underlying these biological effects. On the other hand, participants writing about previously undisclosed traumas showed no differences in health outcomes from those writing about previously disclosed traumas (Greenberg & Stone, 1992) and participants writing about imaginary traumas that they had not actually experienced, and therefore could not have inhibited, also demonstrated significant improvements in physical health (Greenberg et al, 1996). Therefore, although inhibition may play a part, the observed benefits of writing are not entirely due to reductions in inhibition.

In a 2013 article by Nazarian and Smyth,[7] writing instructions for the expressive writing task were manipulated — in that 6 conditions were created — i.e., cognitive-processing, exposure, self-regulation, and benefit-finding, standard expressive writing and a control group. While salivary cortisol was measured for each condition, none of the conditions significantly influenced cortisol, but instructions did impact mood differentially depending on the condition. For example, the cognitive-processing as measured post-intervention were influenced not only by the cognitive processing instructions but also by exposure and benefit-finding. These results demonstrate a spillover effect from instructions to outcomes. In related research Travagin, Margola, Dennis and Revenson[8] cognitive-processing instructions were compared to standard expressive writing for adolescents with peer problems and this research demonstrated better long-term social adjustment compared to standard expressive writing and greater increased positive affect for those adolescents who reported more peer problems than most.

Edit

An additional line of enquiry, which has particular bearing on the difference between talking and writing, derives from Robert Ornstein’s studies into the bicameral structure of the brain.[9] While noting that what follows should be considered «wildly hypothetical», L’Abate, quoting Ornstein, postulates that:

One could argue … that talk, and writing differ in relative cerebral dominance. … if language is more related to the right hemisphere, then writing may be more related to the left hemisphere. If this is the case, then writing might use or even stimulate parts of the brain that are not stimulated by talking.[10]

Julie Gray, founder of Stories Without Borders notes that «People who have experienced trauma in their lives, whether or not they consider themselves writers, can benefit from creating narratives out of their stories. It is helpful to write it down, in other words, in safety and in non-judgment. Trauma can be quite isolating. Those who have suffered need to understand how they feel and also to try to communicate that to others.»[11]

Clinical implications of writing therapyEdit

Additional research since the 1980s has demonstrated that expressive writing may act as an agent to increase long-term health.[12] Expressive writing can result in physiological, psychological, and biological outcomes, and is part of the emerging medical humanities field.[13] Experiments demonstrate quantitative physiological readout such as changes in immune counts, blood pressure, in addition to qualitative readouts relating to psychiatric symptoms.[14][15][16] Past attempts at implementing expressive writing interventions in clinical settings indicate that there are potential benefits for treatment plans.[17] However, the specifics of such expressive writing procedures or protocols, and the populations most likely to benefit are not entirely clear.

Potential benefits of expressive writingEdit

One of the most important aspects of expressive writing used in therapy is the short-term, and long-term effects on the individuals participating. Karen Baikie and Kay Wilhelm[18] go into a brief description of the effects people will have after completing a therapeutic expressive writing session.

The short-term effects after utilizing this form of therapy are usually a quick span of feeling distress or being in a negative mood. However, following up with clients after a longer amount of time to measure those effects finds evidence of many mental and physical health benefits.

These benefits include but are not limited to: “Reduced blood pressure, improved mood, reduced depressive symptoms, and fewer post-traumatic intrusion/avoidance symptoms.”

This study also showed that these positive long-term emotional outcomes correlated to positive physical outcomes such as: improved memory, improved performance at work, quicker re-employment and many more. While the short-term effects of this therapeutic practice may seem daunting, in reality they are just the steppingstones for individuals to begin a cycle of growth.

Potential benefits for cancer patientsEdit

Illness and disease are experienced on multiple different fronts: biological, psychological, and social. Recent research has explored how narrative medicine and expressive writing, independently, may play a therapeutic role in chronic diseases such as cancer.[19] Comparisons in practice have been made between expressive writing and psychotherapy.[20] Similarly, practices such as: integrative, holistic, humanistic or complementary medicine have already been incorporated into the field. Expressive writing is self-administered with minimal prompting. With further research and refinement, it may be used as a more cost effective alternative to psychotherapy.[20]

Recent experiments, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses examining the effects of expressive writing on ameliorating negative cancer symptoms yielded primarily non-significant initial results.[21][16][22][23] However, analysis of sub-groups and moderating variables suggest that particular symptoms, or situations, may benefit some more than others with the implementation of an expressive writing intervention. For example, a review by Antoni and Dhabhar (2019) examined how psychosocial stress negatively impacts the immune response of patients with cancer.[24] Even if an expressive writing intervention cannot directly impact cancer prognosis, it may play an important role in mediating factors such as chronic stress, trauma, depression, and anxiety.

Potential benefits for individuals recovering from addictionEdit

The impact of writing therapy for those struggling with addiction plays a significant role in their recovery treatment. Writing exercises – even simple ones such as poetry or stories – have the potential to improve those in addiction recovery the ability to cope with their conditions, and overall health.[25]

The role of the distance therapiesEdit

With the accessibility provided by the Internet, the reach of the writing therapies has increased considerably, as clients and therapists can work together from anywhere in the world, provided they can write the same language. They simply «enter» into a private «chat room» and engage in an ongoing text dialogue in «real time». Participants can also receive therapy sessions via e-text and/or voice with video, and complete online questionnaires, handouts, workout sheets and similar exercises.[26]

This requires the services of a counsellor or therapist, albeit sitting at a computer. Given the huge disjunction between the amount of mental illness compared with the paucity of skilled resources, new ways have been sought to provide therapy other than drugs. In the more advanced societies pressure for cost-effective treatments, supported by evidence-based results, has come from both insurance companies and government agencies. Hence the decline in long term intensive psychoanalysis and the rise of much briefer forms, such as cognitive therapy.[citation needed]

Via the InternetEdit

Currently, the most widely used mode of Internet writing therapy is via e-mail (see analytic psychotherapist Nathan Field’s paper «The Therapeutic Action of Writing in Self-Disclosure and Self-Expression»).[27] It is asynchronous; i.e. messages are passed between therapist and client within an agreed time frame (for instance, one week), but at any time within that week. Where both parties remain anonymous the client benefits from the online disinhibition effect; that is to say, feels freer to disclose memories, thoughts and feelings that they might withhold in a face-to-face situation. Both client and therapist have time for reflecting on the past and recapturing forgotten memories, time for privately processing their reactions and giving thought to their own responses. With e-therapy, space is eliminated, and time expanded. Overall, it considerably reduces the amount of therapeutic input, as well as the speed and pressure that therapists habitually have to work under.

The anonymity and invisibility provides a therapeutic environment that comes much closer than classical analysis to Freud’s ideal of the «analytic blank screen». Sitting behind the patient on the couch still leaves room for a multitude of clues to the analyst’s individuality; e-therapy provides almost none. Whether distance and reciprocal anonymity reduces or increases the level of transference has yet to be investigated.

In a 2016 randomized controlled trial, expressive writing was tested against direction to an online support group for individuals with anxiety and depression. No difference between the groups was found. Both groups showed a moderate improvement over time, but of a magnitude comparable to what one would expect to see over the time period concerned without intervention.[28]

JournallingEdit

The oldest and most widely practiced form of self-help through writing is that of keeping a personal journal or diary—as distinct from a diary or calendar of daily appointments—in which the writer records their most meaningful thoughts and feelings. One individual benefit is that the act of writing puts a powerful brake on the torment of endlessly repeating troubled thoughts to which everyone is prone. Kathleen Adams states that through the act of journal writing, the writer is also able to «literally [read] his or her own mind» and thus «to perceive experiences more clearly and thus feels a relief of tension».[29]

- Self-concealment

- Self-disclosure

- Reflective writing

ReferencesEdit

- ^ Singer, Jessica; Singer, George H.S. (2008). «Writing as Physical and Emotional Healing: Findings from Clinical Research». Handbook of Research on Writing: History, Society, School, Individual, Text. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc. pp. 485–98.

- ^ Pennebaker JW, Beall SK (August 1986). «Confronting a traumatic event: toward an understanding of inhibition and disease». Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 95 (3): 274–81. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.95.3.274. PMID 3745650.

- ^ a b Pennebaker JW (May 1997). «Writing about Emotional Experiences as a Therapeutic Process» (PDF). Psychological Science. 8 (3): 162–166. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00403.x. JSTOR 40063169. S2CID 15516728. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2003.

- ^ Pennebaker, JW (2010). «Expressive writing in a clinical setting». The Independent Practitioner. 30: 23–25.

- ^ Pennebaker JW, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R (April 1988). «Disclosure of traumas and immune function: health implications for psychotherapy». Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 56 (2): 239–45. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.56.2.239. PMID 3372832. S2CID 15923287.

- ^ Krpan KM, Kross E, Berman MG, Deldin PJ, Askren MK, Jonides J (September 2013). «An everyday activity as a treatment for depression: the benefits of expressive writing for people diagnosed with major depressive disorder». Journal of Affective Disorders. 150 (3): 1148–51. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.065. PMC 3759583. PMID 23790815.

- ^ Nazarian D, Smyth JM (2013). «An experimental test of instructional manipulations in expressive writing interventions: Examining processes of change». Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 32 (1): 71–96. doi:10.1521/jscp.2013.32.1.71.

- ^ Travagin G, Margola D, Dennis JL, Revenson TA (December 2016). «Letting Oneself Go Isn’t Enough: Cognitively Oriented Expressive Writing Reduces Preadolescent Peer Problems». Journal of Research on Adolescence. 26 (4): 1048–1060. doi:10.1111/jora.12279. PMID 28453210.

- ^ Ornstein R (1998). The Right Mind: Making Sense of the Hemispheres. Mariner Books.

- ^ L’Abate L (2001). Distance Writing and Computer-Assisted Interventions in Psychiatry and Mental Health. Westport: Ablex Publishing. pp. 9–10.

- ^ Gary J. «Transformative Writing». Stories without Borders. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ Pennebaker JW, Beall SK (August 1986). «Confronting a traumatic event: toward an understanding of inhibition and disease». Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 95 (3): 274–81. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.95.3.274. PMID 3745650.

- ^ Bolton G (June 2008). «Boundaries of Humanities: Writing Medical Humanities». Arts and Humanities in Higher Education. 7 (2): 131–148. doi:10.1177/1474022208088643. ISSN 1474-0222. S2CID 145209285.

- ^ Baikie KA, Wilhelm K (September 2005). «Emotional and physical health benefits of expressive writing». Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 11 (5): 338–346. doi:10.1192/apt.11.5.338. ISSN 1355-5146. S2CID 4695643.

- ^ Frisina PG, Borod JC, Lepore SJ (September 2004). «A meta-analysis of the effects of written emotional disclosure on the health outcomes of clinical populations». The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 192 (9): 629–34. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000138317.30764.63. PMID 15348980. S2CID 44735579.

- ^ a b Zachariae R, O’Toole MS (November 2015). «The effect of expressive writing intervention on psychological and physical health outcomes in cancer patients—a systematic review and meta-analysis». Psycho-Oncology. 24 (11): 1349–59. doi:10.1002/pon.3802. PMC 6680178. PMID 25871981.

- ^ Fioretti C, Mazzocco K, Riva S, Oliveri S, Masiero M, Pravettoni G (July 2016). «Research studies on patients’ illness experience using the Narrative Medicine approach: a systematic review». BMJ Open. 6 (7): e011220. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011220. PMC 4947803. PMID 27417197.

- ^ Baikie, Karen A.; Wilhelm, Kay (September 2005). «Emotional and physical health benefits of expressive writing». Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 11 (5): 338–346. doi:10.1192/apt.11.5.338. ISSN 1355-5146. S2CID 4695643.

- ^ Merz EL, Fox RS, Malcarne VL (2014-02-18). «Expressive writing interventions in cancer patients: a systematic review». Health Psychology Review. 8 (3): 339–61. doi:10.1080/17437199.2014.882007. PMID 25053218. S2CID 5214868.

- ^ a b LeRoy AS, Shields A, Chen MA, Brown RL, Fagundes CP (March 2018). «Improving Breast Cancer Survivors’ Psychological Outcomes and Quality of Life: Alternatives to Traditional Psychotherapy». Current Breast Cancer Reports. 10 (1): 28–34. doi:10.1007/s12609-018-0266-y. PMC 7061914. PMID 32153724.

- ^ Chu Q, Wu IH, Tang M, Tsoh J, Lu Q (August 2020). «Temporal relationship of posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters during and after an expressive writing intervention for Chinese American breast cancer survivors». Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 135: 110142. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110142. PMID 32485623. S2CID 219287973.

- ^ Fioretti C, Mazzocco K, Riva S, Oliveri S, Masiero M, Pravettoni G (July 2016). «Research studies on patients’ illness experience using the Narrative Medicine approach: a systematic review». BMJ Open. 6 (7): e011220. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011220. PMC 4947803. PMID 27417197.

- ^ Wu Y, Liu L, Zheng W, Zheng C, Xu M, Chen X, et al. (February 2021). «Effect of prolonged expressive writing on health outcomes in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial». Supportive Care in Cancer. 29 (2): 1091–1101. doi:10.1007/s00520-020-05590-y. PMID 32601853. S2CID 220261066.

- ^ Antoni MH, Dhabhar FS (May 2019). «The impact of psychosocial stress and stress management on immune responses in patients with cancer». Cancer. 125 (9): 1417–1431. doi:10.1002/cncr.31943. PMC 6467795. PMID 30768779.

- ^ Buda, Béla (May 2002). «Stephen J. Lepore & Joshua M. Smyth (Eds.) (2002). The Writing Cure: How Expressive Writing Promotes Health and Emotional Well-Being. By Béla Buda». Crisis. 23 (3): 139. doi:10.1027//0227-5910.23.3.139a. ISSN 2151-2396. PMID 26200669.

- ^ Harwood, T. Mark and L’Abate, Luciano. «Distance Writing: Helping without Seeing Participants.» Self-Help in Mental Health: A Critical Review. London: Springer, 2010. 47.

- ^ Belmont B (December 6, 2016). «Healing Through Words: The Benefits Of Writing Therapy».

- ^ Dean J, Potts HW, Barker C (May 2016). «Direction to an Internet Support Group Compared With Online Expressive Writing for People With Depression And Anxiety: A Randomized Trial». JMIR Mental Health. 3 (2): e12. doi:10.2196/mental.5133. PMC 4887661. PMID 27189142.

- ^ Adams K. «A Brief History of Journal Writing». The Center for Journal Therapy. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

Further readingEdit

- Baikie KA, Wilhelm K (2005). «Emotional and physical health benefits of expressive writing». Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 11 (5): 338–346. doi:10.1192/apt.11.5.338. S2CID 4695643.

- Graybeal A, Sexton JD, Pennebaker JW (2002). «The Role of Story-Making in Disclosure Writing: The Psychometrics of Narrative» (PDF). Psychology & Health. 17 (5): 571–581. doi:10.1080/08870440290025786. S2CID 143760087.

- Morisano D, Hirsh JB, Peterson JB, Pihl RO, Shore BM (March 2010). «Setting, elaborating, and reflecting on personal goals improves academic performance» (PDF). The Journal of Applied Psychology. 95 (2): 255–64. doi:10.1037/a0018478. PMID 20230067. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2016.

Free Speech Therapy Resources

You Need Right Now

You can never have too many Speech Therapy Resources.

Am I right or am I right or am I right…

…Right, Right, Right.

If there is something:

- you would like to add

- you think would be helpful for other SLPs

Please let us know.

We would be happy to put it on this page for others to access.

Since all of our resources are free, we ask that you use good «netiquette» and please refer others to our site to access them.

The best way to do this is by using the share buttons on this page.

Most of the documents are in PDF format.

Download the latest version of Adobe Reader

Thanks, and enjoy.

Explore Our Goal Reaching, Client Centered Products

Resources | Handouts | eBooks | Software| Videos | Misc

Speech Therapy Word Lists

Words are a huge part of doing any type of speech and language therapy.

All of the words were hand picked to be common, functional, and targeted for multiple uses as a resource therapy and/or home practice.

Return to top

Handouts

Unique Ways to Use Flashcards

If you’re getting tired of doing drill and practice and playing memory while you work on target sounds…

…let’s repurpose those flashcards that have been your staple since day one, and encourage carryover at the same time.

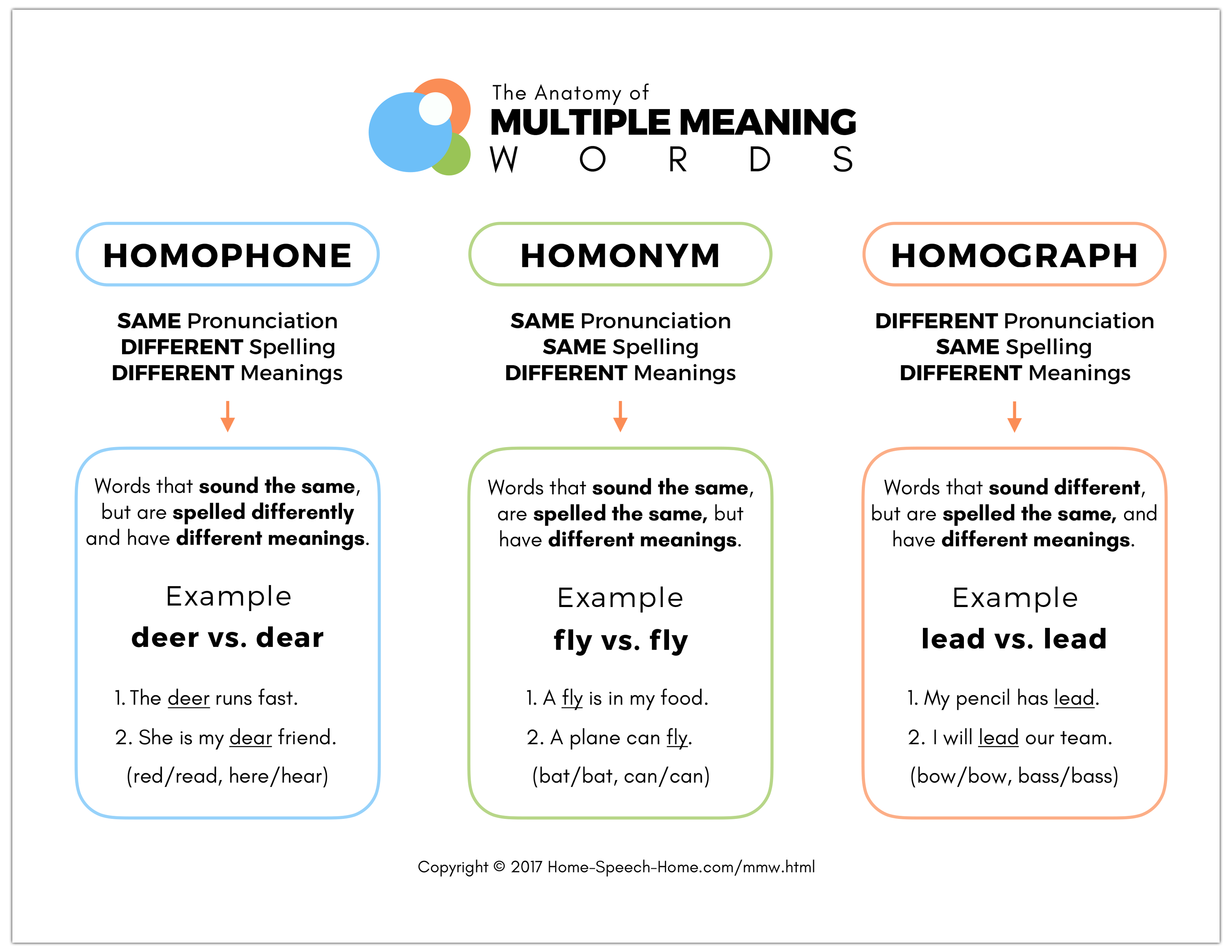

Anatomy of Multiple Meaning Words

Teaching multiple meaning words to students can be tricky enough without a visual.

This chart will save you time and help those you serve understand multiple meaning words more concretely.

Book List

This list will save you time searching for which books can teach what, along with examples of how to use them.

Report Templates

A List of 170+ test descriptions in English and Spanish from Apraxia to Phonology. Ready to copy and paste into your reports.

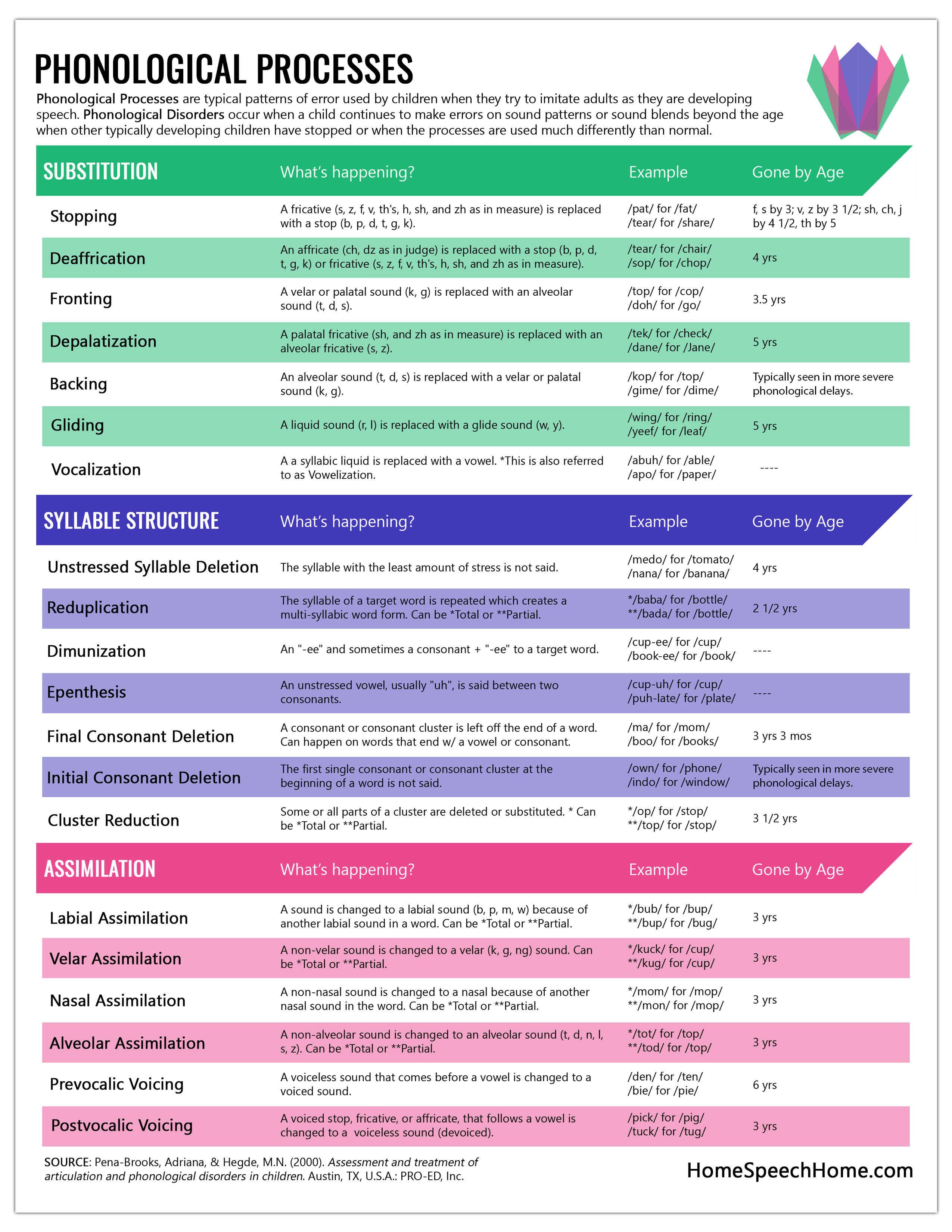

Phonological Process Chart

Nice visual chart of every phonological process with descriptions, examples, and age that they should be remediated.

Describing Worksheet

For children who need a little more assistance using descriptive language, show or give them a copy of this helpful handout for describing.

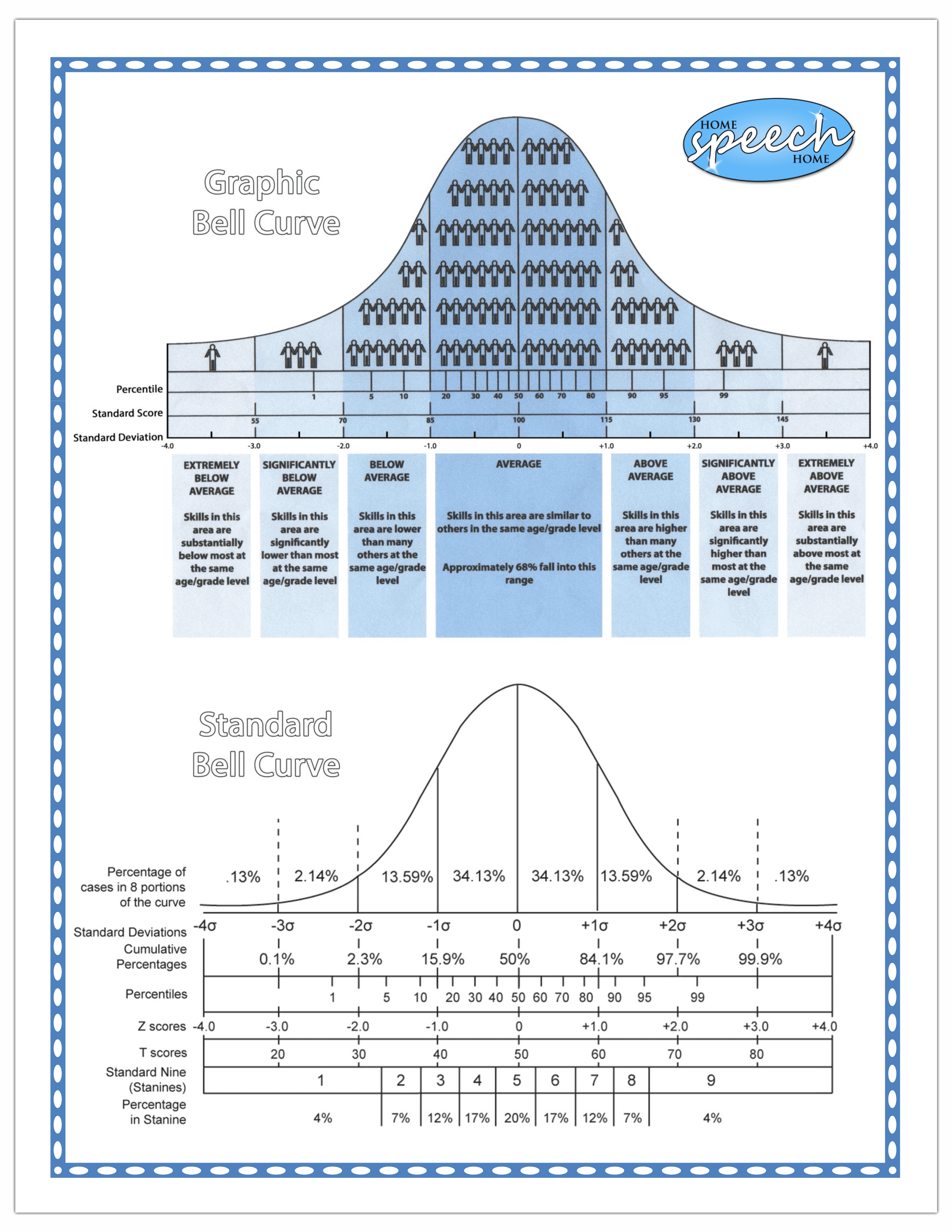

Bell Curve Chart

A bell curve chart that provides a really nice and simple visual representation.

Perfect for explaining test scores to individuals that are unfamiliar with normal distribution.

Top 10 Tips

A compilation of our top 10 Tips of for improving speech and language abilities at home.

These tips are reminders to live by.

Code to Successful

Speech Therapy

One time my student was getting bored during an activity and started saying the words and adding “poo” to the end.

I followed his lead and turned his “bad” behavior into a win-win. This made me think to write down my strategies or “code” that I follow to have my best therapy sessions ever.

Return to top

SEE ALSO: The Best Free App for Speech Therapy

eBooks

Speech Helpers

Print and use this visually loaded resource to teach your student’s about their Speech Helpers.

Each copy includes a hands-on coloring activity that helps children visually learn about their oral anatomy.

Read here about how teaching children about Speech Helpers can improve success.

SLP Job Choosing Guide

Free guide packed with information about key questions to discuss and interview questions to ask potential employers, personal factors to consider, and much more.

Return to top

Software

Free Chronological Age Calculator App

Use our App to calculate a child’s chronological age for comparing their current abilities with the milestone information on our site.

No iPhone or iPad? Use our online chronological age calculator instead.

Speech Language Screeners

These screening tests are designed to give you a comparison between what a child is currently doing and what they should be doing.

Both screeners provide detailed information that will help determine a child’s present levels of performance.

Return to top

Videos

Phonetics Videos

These videos from the University of Iowa are great visual animations of tongue movement how we make consonant and vowel sounds in our mouth

Available in English and Spanish

(after clicking scroll to the bottom

of the page for free access)

Return to top

Misc.

Question & Answer Forums

A dedicated place for every one of our site visitors to submit their comments and questions about anything related to speech and language.

SEE ALSO: The Best Books for Speech Therapy Practice

As Speech Pathologist’s I know we have a lot on our plate.

This section of our website is to provide speech therapy resources to make the lives of SLPs easier and help them be more organized.

First of all, I will admit, I go crazy when I’m not organized.

It’s just the way I am.

I have seen a lot of different tools on the internet and tried to compile as speech therapy resources into this section as possible.

I will always be adding more to this page as I get new ones.

Freebies, Activities, and Specials, Oh My!

Sign up for Terrific Therapy Activity Emails

Your information is 100% private & never shared.

Homepage

>

Speech Therapy Resources

терапия, лечение

существительное ↓

- лечение, терапия

X-ray therapy — мед. рентгенотерапия

cancer therapy — терапия рака

speech [physical] therapy — логопедия [физиотерапия]

occupational therapy — профессиональная переподготовка

therapy at the hospital — лечение в больнице, клиническое лечение

- pl. методы лечения

the therapies of cancer — методы лечения рака

- лекарственное действие

Мои примеры

Словосочетания

massage therapy as an adjunct treatment — массажная терапия в качестве дополнения к лечению

therapy to prevent the leg muscles from atrophying — терапия для предотвращения атрофии мышц ног

physical therapy — физиотерапия

drug therapy — лекарственная терапия

music therapy — музыкальная терапия

to be in therapy — проходить курс лечения у психотерапевта

vaccine therapy — вакцинотерапия

convulsive shock therapy — электросудорожная/электроконвульсивная терапия; электрошок

electric convulsive therapy — лечебный электрошок

definitive therapy — радикальные методы лечения; радикальная терапия

depot therapy — лечение препаратами пролонгированного действия

therapy dose — терапевтическая доза; лечебная доза

Примеры с переводом

Talking over my problem with you has been good therapy.

Разговор о моей проблеме с тобой, был хорошей терапией.

We tried every imaginable therapy.

Мы перепробовали все мыслимые терапии /варианты лечения/.

Rob was in therapy for several years.

Роб несколько лет ходил к психоаналитику.

Hormon replacement therapy is very important and should be instituted early.

Гормонозаместительная терапия очень важна, и её следует начинать как можно раньше.

He is undergoing cancer therapy.

Он проходит курс лечения от рака.

Writing was a form of therapy for him.

Для него писательство было своего рода терапией.

Heat therapy gave the best relief.

Наибольшее облегчение принесла термотерапия /теплолечение/.

ещё 7 примеров свернуть

Примеры, ожидающие перевода

Bright-light therapy is used as a surrogate for sunshine.

…talking over my problem with you has been good therapy…

Massage therapy can be used as an adjunct along with the medication.

Для того чтобы добавить вариант перевода, кликните по иконке ☰, напротив примера.

Возможные однокоренные слова

Формы слова

noun

ед. ч.(singular): therapy

мн. ч.(plural): therapies

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Therapy | |

|---|---|

Children undergoing physical therapy (polio). |

|

| MeSH | D013812 |

|

[edit on Wikidata] |

A therapy or medical treatment (often abbreviated tx, Tx, or Tx) is the attempted remediation of a health problem, usually following a medical diagnosis.

As a rule, each therapy has indications and contraindications. There are many different types of therapy. Not all therapies are effective. Many therapies can produce unwanted adverse effects.

Medical treatment and therapy are generally considered synonyms. However, in the context of mental health, the term therapy may refer specifically to psychotherapy.

History[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2021) |

Before the creating of therapy as a formal procedure, people told stories to one another to inform and assist about the world.[1] The term «healing through words» was used over 3,500 years ago in Greek and Egyptian writing.[2] The term psychotherapy was invented in the 19th century,[3] and psychoanalysis was founded by Sigmund Freud under a decade later.

Semantic field[edit]

The words care, therapy, treatment, and intervention overlap in a semantic field, and thus they can be synonymous depending on context. Moving rightward through that order, the connotative level of holism decreases and the level of specificity (to concrete instances) increases. Thus, in health care contexts (where its senses are always noncount), the word care tends to imply a broad idea of everything done to protect or improve someone’s health (for example, as in the terms preventive care and primary care, which connote ongoing action), although it sometimes implies a narrower idea (for example, in the simplest cases of wound care or postanesthesia care, a few particular steps are sufficient, and the patient’s interaction with that provider is soon finished). In contrast, the word intervention tends to be specific and concrete, and thus the word is often countable; for example, one instance of cardiac catheterization is one intervention performed, and coronary care (noncount) can require a series of interventions (count). At the extreme, the piling on of such countable interventions amounts to interventionism, a flawed model of care lacking holistic circumspection—merely treating discrete problems (in billable increments) rather than maintaining health. Therapy and treatment, in the middle of the semantic field, can connote either the holism of care or the discreteness of intervention, with context conveying the intent in each use. Accordingly, they can be used in both noncount and count senses (for example, therapy for chronic kidney disease can involve several dialysis treatments per week).

The words aceology and iamatology are obscure and obsolete synonyms referring to the study of therapies.

The English word therapy comes via Latin therapīa from Greek: θεραπεία and literally means «curing» or «healing».[4]

Types of therapies[edit]

Therapy comes in different forms. These include, cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, mindful based cognitive therapy, physical therapy, etc.[5] Therapists are here for use and used daily by many people. Therapist are trained to provide treatment to an individual or group.[6] Therapy was invented in the 1800s and the founder was Franz Mesmer, the «Father of Western Psychotherapy».[6] Sigmund Freud then comes into play and shows us the understanding depth of all the different types included in therapy.[5] Therapy is used in many ways to shape and help reform a person. This type of treatment allows individuals to regain gain goals lost or wanting to accomplish. Many individuals come into therapy looking for ways to cope with issues and to receive an emotional release. For example, healing from trauma, in need of support, emotional issues, and many more.[7] Allowing yourself to express your thoughts and feelings go a long way in therapy recovery, this is called the therapeutic process.[8]

By chronology, priority, or intensity[edit]

Levels of care[edit]

Levels of care classify health care into categories of chronology, priority, or intensity, as follows:

- Emergency care handles medical emergencies and is a first point of contact or intake for less serious problems, which can be referred to other levels of care as appropriate.

- Intensive care, also called critical care, is care for extremely ill or injured patients. It thus requires high resource intensity, knowledge, and skill, as well as quick decision making.

- Ambulatory care is care provided on an outpatient basis. Typically patients can walk into and out of the clinic under their own power (hence «ambulatory»), usually on the same day.

- Home care is care at home, including care from providers (such as physicians, nurses, and home health aides) making house calls, care from caregivers such as family members, and patient self-care.

- Primary care is meant to be the main kind of care in general, and ideally a medical home that unifies care across referred providers.

- Secondary care is care provided by medical specialists and other health professionals who generally do not have first contact with patients, for example, cardiologists, urologists and dermatologists. A patient reaches secondary care as a next step from primary care, typically by provider referral although sometimes by patient self-initiative.

- Tertiary care is specialized consultative care, usually for inpatients and on referral from a primary or secondary health professional, in a facility that has personnel and facilities for advanced medical investigation and treatment, such as a tertiary referral hospital.

- Follow-up care is additional care during or after convalescence. Aftercare is generally synonymous with follow-up care.

- End-of-life care is care near the end of one’s life. It often includes the following:

- Palliative care is supportive care, most especially (but not necessarily) near the end of life.

- Hospice care is palliative care very near the end of life when cure is very unlikely. Its main goal is comfort, both physical and mental.

Lines of therapy[edit]

Treatment decisions often follow formal or informal algorithmic guidelines. Treatment options can often be ranked or prioritized into lines of therapy: first-line therapy, second-line therapy, third-line therapy, and so on. First-line therapy (sometimes referred to as induction therapy, primary therapy, or front-line therapy)[9] is the first therapy that will be tried. Its priority over other options is usually either: (1) formally recommended on the basis of clinical trial evidence for its best-available combination of efficacy, safety, and tolerability or (2) chosen based on the clinical experience of the physician. If a first-line therapy either fails to resolve the issue or produces intolerable side effects, additional (second-line) therapies may be substituted or added to the treatment regimen, followed by third-line therapies, and so on.

An example of a context in which the formalization of treatment algorithms and the ranking of lines of therapy is very extensive is chemotherapy regimens. Because of the great difficulty in successfully treating some forms of cancer, one line after another may be tried. In oncology the count of therapy lines may reach 10 or even 20.

Often multiple therapies may be tried simultaneously (combination therapy or polytherapy). Thus combination chemotherapy is also called polychemotherapy, whereas chemotherapy with one agent at a time is called single-agent therapy or monotherapy.

Adjuvant therapy is therapy given in addition to the primary, main, or initial treatment, but simultaneously (as opposed to second-line therapy). Neoadjuvant therapy is therapy that is begun before the main therapy. Thus one can consider surgical excision of a tumor as the first-line therapy for a certain type and stage of cancer even though radiotherapy is used before it; the radiotherapy is neoadjuvant (chronologically first but not primary in the sense of the main event). Premedication is conceptually not far from this, but the words are not interchangeable; cytotoxic drugs to put a tumor «on the ropes» before surgery delivers the «knockout punch» are called neoadjuvant chemotherapy, not premedication, whereas things like anesthetics or prophylactic antibiotics before dental surgery are called premedication.

Step therapy or stepladder therapy is a specific type of prioritization by lines of therapy. It is controversial in American health care because unlike conventional decision-making about what constitutes first-line, second-line, and third-line therapy, which in the U.S. reflects safety and efficacy first and cost only according to the patient’s wishes, step therapy attempts to mix cost containment by someone other than the patient (third-party payers) into the algorithm. Therapy freedom and the negotiation between individual and group rights are involved.

By intent[edit]

| Therapy type | Description |

|---|---|

| abortive therapy | A therapy that is intended to stop a medical condition from progressing any further. A medication taken at the earliest signs of a disease, such as an analgesic taken at the very first symptoms of a migraine headache to prevent it from getting worse, is an abortive therapy. Compare abortifacients, which abort a pregnancy. |

| bridge therapy | A therapy that figuratively provides a bridge to another step or phase, crossing over some immediate chasm (challenge), in contrast with destination therapy, which is the final therapy in cases where clinically appropriate. |

| consolidation therapy | A therapy given to consolidate the gains from induction therapy. In cancer, this means chasing after any malignant cells that may be left. |

| curative therapy | A therapy with curative intent, that is, one that seeks to cure the root cause of a disorder. (also called etiotropic therapy) |

| definitive therapy | A therapy that may be final, superior to others, curative, or all of those. |

| destination therapy | A therapy that is the final destination rather than a bridge to another therapy. Usually refers to ventricular assist devices to keep the existing heart going, not just until heart transplantation can occur, but for the rest of the patient’s life expectancy. |

| empiric therapy | A therapy given on an empiric basis; that is, one given according to a clinician’s educated guess despite uncertainty about the illness’s causative factors. For example, empiric antibiotic therapy administers a broad-spectrum antibiotic immediately on the basis of a good chance (given the history, physical examination findings, and risk factors present) that the illness is bacterial and will respond to that drug (even though the bacterial species or variant is not yet known). |

| gold standard therapy | A therapy that is definitive, just as a gold standard diagnostic test is a definitive test. |

| investigational therapy | An experimental therapy. Use of experimental therapies must be ethically justified, because by definition they raise the question of standard of care. Physicians have autonomy to provide empirical care (such as off-label care) according to their experience and clinical judgment, but the autonomy has limits that preclude quackery. Thus it may be necessary to design a clinical trial around the new therapy and to use the therapy only per a formal protocol. Sometimes shorthand phrases such as «treated on protocol» imply not just «treated according to a plan» but specifically «treated with investigational therapy». |

| maintenance therapy | A therapy taken during disease remission to prevent relapse. |

| palliative therapy | See supportive therapy for connotative distinctions. |

| preventive therapy (prophylactic therapy) |

A therapy that is intended to prevent a medical condition from occurring (also called prophylaxis). For example, many vaccines prevent infectious diseases. |

| salvage therapy (rescue therapy) | A therapy tried after others have failed; it may be a «last-line» therapy. |

| stepdown therapy | Therapy that tapers the dosage gradually rather than abruptly cutting it off. For example, a switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics as an infection is brought under control steps down the intensity of therapy. |

| supportive therapy | A therapy that does not treat or improve the underlying condition, but rather increases the patient’s comfort, also called symptomatic treatment (see there for more information).[10] For example, supportive care for flu, colds, or gastrointestinal upset can include rest, fluids, and over the counter pain relievers; those things do not treat the cause, but they treat the symptoms and thus provide relief. Supportive therapy may be palliative therapy (palliative care). The two terms are sometimes synonymous, but palliative care often specifically refers to serious illness and end-of-life care. Therapy may be categorized as having curative intent (when it is possible to eliminate the disease) or palliative intent (when eliminating the disease is impossible and the focus shifts to minimizing the distress that it causes). The two are often contradistinguished (mutually exclusive) in some contexts (such as the management of some cancers), but they are not inherently mutually exclusive; often therapy can be both curative and palliative simultaneously. Supportive psychotherapy aims to support the patient by alleviating the worst of the symptoms, with the expectation that definitive therapy can follow later if possible. |

| systemic therapy | A therapy that is systemic. In the physiological sense, this means affecting the whole body (rather than being local or locoregional), whether via systemic administration, systemic effect, or both. Systemic therapy in the psychotherapeutic sense seeks to address people not only on the individual level but also as people in relationships, dealing with the interactions of groups. |

By therapy composition[edit]

Treatments can be classified according to the method of treatment:

By matter[edit]

- by drugs: pharmacotherapy, chemotherapy (also, medical therapy often means specifically pharmacotherapy)

- by medical devices: implantation

- cardiac resynchronization therapy

- by specific molecules: molecular therapy (although most drugs are specific molecules, molecular medicine refers in particular to medicine relying on molecular biology)

- by specific biomolecular targets: targeted therapy

- molecular chaperone therapy

- by chelation: chelation therapy

- by specific biomolecular targets: targeted therapy

- by specific chemical elements:

- by metals:

- by heavy metals:

- by gold: chrysotherapy (aurotherapy)

- by platinum-containing drugs: platin therapy

- by biometals

- by lithium: lithium therapy

- by potassium: potassium supplementation

- by magnesium: magnesium supplementation

- by chromium: chromium supplementation; phonemic neurological hypochromium therapy

- by copper: copper supplementation

- by heavy metals:

- by nonmetals:

- by diatomic oxygen: oxygen therapy, hyperbaric oxygen therapy (hyperbaric medicine)

- transdermal continuous oxygen therapy

- by triatomic oxygen (ozone): ozone therapy

- by fluoride: fluoride therapy

- by other gases: medical gas therapy

- by diatomic oxygen: oxygen therapy, hyperbaric oxygen therapy (hyperbaric medicine)

- by metals:

- by water:

- hydrotherapy

- aquatic therapy

- rehydration therapy

- oral rehydration therapy

- water cure (therapy)

- by biological materials (biogenic substances, biomolecules, biotic materials, natural products), including their synthetic equivalents: biotherapy

- by whole organisms

- by viruses: virotherapy

- by bacteriophages: phage therapy

- by animal interaction: see animal interaction section

- by constituents or products of organisms

- by plant parts or extracts (but many drugs are derived from plants, even when the term phytotherapy is not used)

- scientific type: phytotherapy

- traditional (prescientific) type: herbalism

- by animal parts: quackery involving shark fins, tiger parts, and so on, often driving threat or endangerment of species

- by genes: gene therapy

- gene therapy for epilepsy

- gene therapy for osteoarthritis

- gene therapy for color blindness

- gene therapy of the human retina

- gene therapy in Parkinson’s disease

- by epigenetics: epigenetic therapy

- by proteins: protein therapy (but many drugs are proteins despite not being called protein therapy)

- by enzymes: enzyme replacement therapy

- by hormones: hormone therapy

- hormonal therapy (oncology)

- hormone replacement therapy

- estrogen replacement therapy

- androgen replacement therapy

- hormone replacement therapy (menopause)

- transgender hormone therapy

- feminizing hormone therapy

- masculinizing hormone therapy

- antihormone therapy

- androgen deprivation therapy

- by whole cells: cell therapy (cytotherapy)

- by stem cells: stem cell therapy

- by immune cells: see immune system products below

- by immune system products: immunotherapy, host modulatory therapy

- by immune cells:

- T-cell vaccination

- cell transfer therapy

- autologous immune enhancement therapy

- TK cell therapy

- by humoral immune factors: antibody therapy

- by whole serum: serotherapy, including antiserum therapy

- by immunoglobulins: immunoglobulin therapy

- by monoclonal antibodies: monoclonal antibody therapy

- by immune cells:

- by plant parts or extracts (but many drugs are derived from plants, even when the term phytotherapy is not used)

- by urine: urine therapy (some scientific forms; many prescientific or pseudoscientific forms)

- by food and dietary choices:

- medical nutrition therapy

- grape therapy (quackery)

- by whole organisms

- by salts (but many drugs are the salts of organic acids, even when drug therapy is not called by names reflecting that)

- by salts in the air

- by natural dry salt air: «taking the cure» in desert locales (especially common in prescientific medicine; for example, one 19th-century way to treat tuberculosis)

- by artificial dry salt air:

- low-humidity forms of speleotherapy

- negative air ionization therapy

- by moist salt air:

- by natural moist salt air: seaside cure (especially common in prescientific medicine)

- by artificial moist salt air: water vapor forms of speleotherapy

- by salts in the water

- by mineral water: spa cure («taking the waters») (especially common in prescientific medicine)

- by seawater: seaside cure (especially common in prescientific medicine)

- by salts in the air

- by aroma: aromatherapy

- by other materials with mechanism of action unknown

- by occlusion with duct tape: duct tape occlusion therapy

By energy[edit]

- by electric energy as electric current: electrotherapy, electroconvulsive therapy

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation

- Vagus nerve stimulation

- by magnetic energy:

- magnet therapy

- pulsed electromagnetic field therapy

- magnetic resonance therapy

- by electromagnetic radiation (EMR):

- by light: light therapy (phototherapy)

- ultraviolet light therapy

- PUVA therapy

- photodynamic therapy

- photothermal therapy

- cytoluminescent therapy

- blood irradiation therapy

- by darkness: dark therapy

- by lasers: laser therapy

- low level laser therapy

- ultraviolet light therapy

- by gamma rays: radiosurgery

- Gamma Knife radiosurgery

- stereotactic radiation therapy

- cobalt therapy

- by radiation generally: radiation therapy (radiotherapy)

- intraoperative radiation therapy

- by EMR particles:

- particle therapy

- proton therapy

- electron therapy

- intraoperative electron radiation therapy

- Auger therapy

- neutron therapy

- fast neutron therapy

- neutron capture therapy of cancer

- particle therapy

- by radioisotopes emitting EMR:

- by nuclear medicine

- by brachytherapy

- quackery type: electromagnetic therapy (alternative medicine)

- by light: light therapy (phototherapy)

- by mechanical: manual therapy as massotherapy and therapy by exercise as in physical therapy

- inversion therapy

- by sound:

- by ultrasound:

- ultrasonic lithotripsy

- extracorporeal shockwave therapy

- sonodynamic therapy

- ultrasonic lithotripsy

- by music: music therapy

- by ultrasound:

- by temperature

- by heat: heat therapy (thermotherapy)

- by moderately elevated ambient temperatures: hyperthermia therapy

- by dry warm surroundings: Waon therapy

- by dry or humid warm surroundings: sauna, including infrared sauna, for sweat therapy

- by moderately elevated ambient temperatures: hyperthermia therapy

- by cold:

- by extreme cold to specific tissue volumes: cryotherapy

- by ice and compression: cold compression therapy

- by ambient cold: hypothermia therapy for neonatal encephalopathy

- by hot and cold alternation: contrast bath therapy

- by heat: heat therapy (thermotherapy)

By procedure and human interaction[edit]

- Surgery

- by counseling, such as psychotherapy (see also: list of psychotherapies)

- systemic therapy

- by group psychotherapy[11]

- by cognitive behavioral therapy

- by cognitive therapy

- by behaviour therapy

- by dialectical behavior therapy

- by cognitive emotional behavioral therapy

- by cognitive rehabilitation therapy

- by family therapy

- by education

- by psychoeducation

- by information therapy

- by speech therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, vision therapy, massage therapy, chiropractic or acupuncture

- by lifestyle modifications, such as avoiding unhealthy food or maintaining a predictable sleep schedule

- by coaching

By animal interaction[edit]

- by pets, assistance animals, or working animals: animal-assisted therapy

- by horses: equine therapy, hippotherapy

- by dogs: pet therapy with therapy dogs, including grief therapy dogs

- by cats: pet therapy with therapy cats

- by fish: ichthyotherapy (wading with fish), aquarium therapy (watching fish)

- by maggots: maggot therapy

- by worms:

- by internal worms: helminthic therapy

- by leeches: leech therapy

- by immersion: animal bath

By meditation[edit]

- by mindfulness: mindfulness-based cognitive therapy

By reading[edit]

- by bibliotherapy

By creativity[edit]

- by expression: expressive therapy

- by writing: writing therapy

- journal therapy

- by writing: writing therapy

- by play: play therapy

- by art: art therapy

- sensory art therapy

- comic book therapy

- by gardening: horticultural therapy

- by dance: dance therapy

- by drama: drama therapy

- by recreation: recreational therapy

- by music: music therapy

By sleeping and waking[edit]

- by deep sleep: deep sleep therapy[12]

- by sleep deprivation: wake therapy[13]

See also[edit]

- Biophilia hypothesis

- Classification of Pharmaco-Therapeutic Referrals

- Cure

- Interventionism (medicine)

- Inverse benefit law

- List of therapies

- Greyhound therapy

- Mature minor doctrine

- Medicine

- Medication

- Nutraceutical

- Prevention

- Psychotherapy

- Treatment as prevention

- Therapeutic inertia

- Therapeutic nihilism, the idea that treatment is useless

References[edit]

- ^ «A Brief History of Therapy». 24 February 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ «A Brief History of Psychotherapy». 9 October 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Shamdasani S. (2005). «Psychotherapy: The Invention of a Word». History of the Human Sciences. 18: 1–22. doi:10.1177/0952695105051123. S2CID 146593953. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary, Therapy

- ^ a b «What is Therapy and Will It Work? | JED». The Jed Foundation. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ a b Weinberger, Jessica (2020-02-24). «A Brief History of Therapy». Talkspace. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ DiMarco, Franco (2018). Vulnerability to Psychosis: a Psychoanalytic Study of the Nature and Therapy of the Psychotic State. Taylor and Francis.

- ^ «Psychotherapy: What to expect and how it works». www.medicalnewstoday.com. 2020-07-20. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ National Cancer Institute > Dictionary of Cancer Terms > first-line therapy Retrieved July 2010

- ^ «CFIDS». CFIDS. Archived from the original on 2012-02-13. Retrieved 2012-01-09.

- ^ Schwartz, Jeremy. «5 Reasons to Consider Group Therapy». U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 22 July 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ Shorter, Edward (January 1996). «The beginning of psychopharmacology: Deep-sleep therapies». European Psychiatry. 11: 236s. doi:10.1016/0924-9338(96)88707-4. S2CID 144323687.

- ^ Minkel, Jared D.; Krystal, Andrew D.; Benca, Ruth M. (2017). «Unipolar Major Depression». In Kryger, Meir; Roth, Thomas; Dement, William C. (eds.). Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. pp. 1352–1362. ISBN 978-0-323-24288-2. Retrieved 12 May 2021.