1. [seı]

1. высказывание, мнение, слово

to have one’s say — высказываться; высказывать своё мнение

he has had his say — он уже высказал своё мнение, он уже имел возможность высказаться

it is now my say — теперь я скажу /моя очередь говорить/

to say one’s say — высказывать всё, что думаешь

2. авторитет, влияние

to have a say in the matter — иметь, влияние в каком-л. деле; участвовать в решении какого-л. вопроса

who has the say in the matter? — за кем решающее слово в этом вопросе?

2. [seı]

(said)

1. 1) говорить, сказать

❝All right❞, he says — «Хорошо», — говорит он

❝Come here❞, said he — «Подойди(те) сюда», — сказал он

❝I will do it❞, she said (resolutely) — «Я сделаю это», — (про)молвила она (решительно)

he said it sharply [in a harsh voice] — он сказал это резко [резким /сердитым/ голосом]

what does he say? — что он говорит?

he said (that) he was busy — он сказал, что он занят

she said (that) she wanted to see me [to read this book] — она сказала, что хочет видеть меня [прочесть эту книгу]

he said (that) she should come — он сказал /велел/, чтобы она пришла

I say (that) you must do it — я говорю, что ты должен это сделать [ тж. 4]

to say smth. to smb. — сказать что-л. кому-л.

I have smth. to say to you — мне нужно тебе кое-что сказать [ тж. 4 5]

to say nothing — ничего не сказать /не говорить/, (про)молчать

I have nothing to say — мне нечего сказать, мне не о чем говорить [ тж. 5]

I have nothing to say to him — а) мне нечего ему сказать; б) мне с ним не о чем говорить, я и говорить с ним не желаю

say no more! — ни слова больше!, хватит!

he didn’t say a word — он не вымолвил /не произнёс, не сказал/ ни (одного) слова

to say to oneself — сказать себе, (по)думать про себя

to say smth. again — повторять что-л.

say that again! — повторите!

to say over a role — повторять /учить/ роль

to say smth. over and over again — повторять что-л. без конца

they say such things out of /through/ envy — они говорят такие вещи из зависти

easier said than done — легче сказать, чем сделать

the less said the better — чем меньше слов, тем лучше

that is to say — другими /иными/ словами, иначе говоря, то есть

in three weeks’ time, that is to say on January 20 — через три недели, другими словами /то есть/ 20-го января

to say what one knows [wants] — говорить (то), что знаешь [хочешь]

do it because I say so — сделай это, потому что я так говорю /велю/

you have no right to say so! — вы не имеете права так говорить!

I’m glad to say — с радостью могу сказать /отметить /

I’m sorry to say… — к сожалению…

the news surprised me, I must say — признаюсь /признаться сказать/, эти новости удивили меня

I mean to say (that…) — (этим) я хочу сказать (что…)

you don’t mean to say that… — неужели вы хотите сказать, что…

to say yes — а) сказать /говорить/ «да», давать согласие, соглашаться; to say yes to an invitation [to a proposal] — принимать приглашение [предложение]; б) подтверждать ()

to say no — а) сказать /говорить/ «нет», не давать согласия, отказывать; to say no to an invitation [to a proposal] — не принять /отказаться от/ приглашения [предложения]; she again said no to me — она опять отказала мне; б) отрицать, опровергать ()

to say smb. nay — отклонить /отвергнуть/ чью-л. просьбу

to say thank you — сказать «спасибо», (по)благодарить

to say good morning (to smb.) — (по)желать (кому-л.) доброго утра, (по)здороваться (с кем-л.) утром

to say good night (to smb.) — (по)желать (кому-л.) спокойной ночи, (по)прощаться (с кем-л.)

to say goodbye — сказать «до свидания», (по)прощаться

he knows no mathematics to say nothing of cybernetics — он не имеет представления о математике, не говоря уже о кибернетике

not to say… — чтобы не сказать…

he was rude, not to say insolent — он держал себя грубо, чтобы не сказать нагло

2) выражать

I don’t know how to say it — я не знаю, как это сказать /выразить/

he is, if I may say so, a fool — он, с позволения сказать, дурак

America, or, better said, the United States of America — Америка, или, правильнее сказать, Соединённые Штаты Америки

2.

безл. говорить, утверждать (что, якобы), сообщать

people /they/ say (that) the experiment was successful — говорят /ходят слухи/, что опыт удался

it is said in the papers that the treaty was signed yesterday — в газетах сообщают, что договор был подписан вчера

he is said to be /they say he is/ a great singer — говорят, (что) он выдающийся певец

he is said to swim well — говорят, (что) он хорошо плавает

it is generally said that… — обычно утверждают /считают/, что…

3. гласить; говориться

the law says… — закон гласит…, по закону…

the text of the treaty says — текст договора гласит, в тексте договора записано

the telegram says, it says /is said/ in the telegram — телеграмма гласит, в телеграмме сказано

the letter says, it says /is said/ in the letter — в письме говорится

the notice says that the show is cancelled — в объявлении сказано, что спектакль отменяется

the tower clock says ten o’clock — на башенных часах десять (часов), башенные часы показывают десять (часов)

the publisher says in the preface that… — издатель говорит в своём предисловии, что…

4. иметь высказывать мнение, считать, полагать

it was said by Plato that… — Платон утверждал, что…; у Платона сказано /говорится/, что…

what I say is — по-моему, по моему мнению, я считаю, мне кажется

I say you must do it — я считаю, что ты должен это сделать [ тж. 1, 1)]

and so say all of us — и мы тоже так думаем, и мы такого же мнения

to say out / away/ — высказаться откровенно, облегчить душу

I cannot /couldn’t/ say (whether he will come) — я не знаю (придёт ли он)

I wish I could say when it will happen — хотел бы я знать, когда это произойдёт

it is hard to say why [who it was] — трудно (с уверенностью) сказать почему [кто это был]

there is no saying how all this will end — кто знает, как /чем/ всё это кончится

I should say that he is right — я бы сказал /я полагаю/, что он прав

is it expensive? — I should say not — это дорого? — Я бы не сказал /Не думаю/ [ тж. ]

you wouldn’t say by his look that… — по его виду не скажешь, что…

to have smth. to say (to /about/ smth.) — иметь мнение (относительно чего-л.) [ тж. 1, 1) 5]

what have you to say (to all this)? — какое у вас (обо всём этом) мнение?; что вы (обо всём этом /на всё это/) скажете?

what did he say to that? — каково его мнение на этот счёт?, что он об этом думает?, что он на это сказал?

what do you say to my proposal? — как вы смотрите на моё предложение?

what do you say /what say you/ to a meal [to a trip to London]? — как насчёт того, чтобы поесть [съездить в Лондон]?

what do you say to a game of tennis? — сыграем /не хотите ли сыграть/ в теннис?

5. приводить доводы, аргументы; свидетельствовать

to say smth. for [against] smth., smb. — высказываться за [против] чего-л., кого-л.; свидетельствовать в пользу [против] чего-л., кого-л.

I cannot say much for this method — мне нечего сказать в пользу этого метода

I can’t say much for his mathematics — я не могу сказать, чтобы он был очень силён в математике

that doesn’t say much for his intelligence — это не свидетельствует о его большом уме

I cannot say much for his style — я невысокого мнения об его стиле; об его стиле говорить не приходится

there is much to say /to be said/ for [against] this plan — многое говорит в пользу [не в пользу] этого плана

to say a good word for smb. — замолвить за кого-л. словечко

to have smth. to say — возражать [ тж. 1, 1) 4]

he always has smth. to say to my friends [to their coming] — он всегда возражает против моих друзей [их приезда]

I am afraid he will have smth. to say about it — боюсь, что он будет недоволен этим /возражать против этого/

to have smth. to say for oneself — а) сказать что-л. в свою защиту /в своё оправдание/; what have you to say for yourself? — что вы можете сказать в своё оправдание [ тж. б)]; б) рассказывать кое-что себе; what have you to say for yourself? — что вы можете о себе рассказать?, что у вас нового? [ тж. а)]; в) быть разговорчивым, бойким на язык

to have nothing to say — не иметь доводов, не находить аргументов [ тж. 1, 1)]

to have nothing to say for oneself — а) не знать, что сказать в свою защиту /в своё оправдание/; б) быть неразговорчивым

6. 1) читать наизусть, декламировать

to say a poem — читать /декламировать/ стихотворение

2) повторять наизусть, произносить вслух

to say one’s prayers — молиться, читать молитвы

to say mass — служить мессу /обедню/

7. допускать; предполагать

let us say — скажем, например, к примеру сказать, примерно

come to see me one of these days, let us say Sunday — приходи ко мне на этих днях, скажем, в воскресенье

if fifty is too much, shall we say thirty? — если пятьдесят слишком много, то тогда, может быть, тридцать?

well, say it were true, what then? — ну, допустим, (что) это верно, что ж из того?

I say!, say! — а) послушайте!, эй! (); I say, what’s the point of all this? — послушай, в чём смысл всего этого?; I say, do come and look at this! — подойди же и посмотри на это!; б) да ну!, ну и ну!, вот так так!, вот тебе и на! ()

say, how is that? — ну как же так?

oh, I say! It was you who spoke to me! — да что вы! Это ведь вы заговорили первая!

so you say! — рассказывайте!, так я вам и поверил!

says you!, sez you! — брехня!, как бы не так!, ещё чего скажешь!

I should say so! — ещё бы!, конечно!

I should say not! — ни за что!, конечно, нет! [ тж. 4]

you don’t say (so)! — что вы говорите?, не может быть!, неужели!, скажи(те) на милость /пожалуйста/!

it is just as you say, you said it — вот именно

you may well say so! — совершенно верно /точно/!

say when — скажи, когда довольно ()

to say the word — приказать; распорядиться

you have only to say the word — вам стоит только слово сказать, только прикажите

to say it with flowers — а) галантно ухаживать; б) передавать чьё-л. поручение, привет в утончённо-любезной форме

before you could say Jack Robinson /knife/ — ≅ не успеешь оглянуться, в один момент

3. [seı]

1. приблизительно, примерно

the property is worth, say, four million dollars — это владение стоит приблизительно четыре миллиона долларов

2. например

if we compress any gas say oxygen — если мы сожмём любой газ, например /скажем, хотя бы/ кислород

«Chronometer» redirects here. For the maritime clock, see Marine chronometer.

24-hour clock face in Florence

A clock or a timepiece[1] is a device used to measure and indicate time. The clock is one of the oldest human inventions, meeting the need to measure intervals of time shorter than the natural units such as the day, the lunar month and the year. Devices operating on several physical processes have been used over the millennia.

Some predecessors to the modern clock may be considered as «clocks» that are based on movement in nature: A sundial shows the time by displaying the position of a shadow on a flat surface. There is a range of duration timers, a well-known example being the hourglass. Water clocks, along with the sundials, are possibly the oldest time-measuring instruments. A major advance occurred with the invention of the verge escapement, which made possible the first mechanical clocks around 1300 in Europe, which kept time with oscillating timekeepers like balance wheels.[2][3][4][5]

Traditionally, in horology (the study of timekeeping), the term clock was used for a striking clock, while a clock that did not strike the hours audibly was called a timepiece. This distinction is no longer made. Watches and other timepieces that can be carried on one’s person are usually not referred to as clocks.[6] Spring-driven clocks appeared during the 15th century. During the 15th and 16th centuries, clockmaking flourished. The next development in accuracy occurred after 1656 with the invention of the pendulum clock by Christiaan Huygens. A major stimulus to improving the accuracy and reliability of clocks was the importance of precise time-keeping for navigation. The mechanism of a timepiece with a series of gears driven by a spring or weights is referred to as clockwork; the term is used by extension for a similar mechanism not used in a timepiece. The electric clock was patented in 1840, and electronic clocks were introduced in the 20th century, becoming widespread with the development of small battery-powered semiconductor devices.

The timekeeping element in every modern clock is a harmonic oscillator, a physical object (resonator) that vibrates or oscillates at a particular frequency.[3]

This object can be a pendulum, a tuning fork, a quartz crystal, or the vibration of electrons in atoms as they emit microwaves, the last method of which is so precise that it serves as the definition of the second.

Clocks have different ways of displaying the time. Analog clocks indicate time with a traditional clock face, with moving hands. Digital clocks display a numeric representation of time. Two numbering systems are in use: 12-hour time notation and 24-hour notation. Most digital clocks use electronic mechanisms and LCD, LED, or VFD displays. For the blind and for use over telephones, speaking clocks state the time audibly in words. There are also clocks for the blind that have displays that can be read by touch.

Etymology[edit]

The word clock derives from the medieval Latin word for ‘bell’—clocca—and has cognates in many European languages. Clocks spread to England from the Low Countries,[7] so the English word came from the Middle Low German and Middle Dutch Klocke.[8]

The word derives from the Middle English clokke, Old North French cloque, or Middle Dutch clocke, all of which mean ‘bell’, and stem from an Old Irish root.[9]

History of time-measuring devices[edit]

Sundials[edit]

Simple horizontal sundial

The apparent position of the Sun in the sky moves over the course of each day, reflecting the rotation of the Earth. Shadows cast by stationary objects move correspondingly, so their positions can be used to indicate the time of day. A sundial shows the time by displaying the position of a shadow on a (usually) flat surface, which has markings that correspond to the hours.[10] Sundials can be horizontal, vertical, or in other orientations. Sundials were widely used in ancient times.[11] With the knowledge of latitude, a well-constructed sundial can measure local solar time with reasonable accuracy, within a minute or two. Sundials continued to be used to monitor the performance of clocks until the 1830s, when the use of the telegraph and trains standardized time and time zones between cities.[12]

Devices that measure duration, elapsed time and intervals[edit]

The flow of sand in an hourglass can be used to keep track of elapsed time.

Many devices can be used to mark the passage of time without respect to reference time (time of day, hours, minutes, etc.) and can be useful for measuring duration or intervals. Examples of such duration timers are candle clocks, incense clocks and the hourglass. Both the candle clock and the incense clock work on the same principle wherein the consumption of resources is more or less constant allowing reasonably precise and repeatable estimates of time passages. In the hourglass, fine sand pouring through a tiny hole at a constant rate indicates an arbitrary, predetermined passage of time. The resource is not consumed but re-used.

Water clocks[edit]

Water clocks, along with the sundials, are possibly the oldest time-measuring instruments, with the only exceptions being the day counting tally stick.[13] Given their great antiquity, where and when they first existed is not known and is perhaps unknowable. The bowl-shaped outflow is the simplest form of a water clock and is known to have existed in Babylon and in Egypt around the 16th century BC. Other regions of the world, including India and China, also have early evidence of water clocks, but the earliest dates are less certain. Some authors, however, write about water clocks appearing as early as 4000 BC in these regions of the world.[14]

Greek astronomer Andronicus of Cyrrhus supervised the construction of the Tower of the Winds in Athens in the 1st century B.C.[15] The Greek and Roman civilizations advanced water clock design with improved accuracy. These advances were passed on through Byzantine and Islamic times, eventually making their way back to Europe. Independently, the Chinese developed their own advanced water clocks(水鐘)in 725 AD, passing their ideas on to Korea and Japan.

Some water clock designs were developed independently and some knowledge was transferred through the spread of trade. Pre-modern societies do not have the same precise timekeeping requirements that exist in modern industrial societies, where every hour of work or rest is monitored, and work may start or finish at any time regardless of external conditions. Instead, water clocks in ancient societies were used mainly for astrological reasons. These early water clocks were calibrated with a sundial. While never reaching the level of accuracy of a modern timepiece, the water clock was the most accurate and commonly used timekeeping device for millennia, until it was replaced by the more accurate pendulum clock in 17th-century Europe.

Islamic civilization is credited with further advancing the accuracy of clocks with elaborate engineering. In 797 (or possibly 801), the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad, Harun al-Rashid, presented Charlemagne with an Asian elephant named Abul-Abbas together with a «particularly elaborate example» of a water[16] clock. Pope Sylvester II introduced clocks to northern and western Europe around 1000 AD.[17]

Mechanical water clocks[edit]

The first known geared clock was invented by the great mathematician, physicist, and engineer Archimedes during the 3rd century BC. Archimedes created his astronomical clock[18] that was also a cuckoo clock with birds singing and moving every hour. It is the first carillon clock as it plays music and simultaneously with a person blinking his eyes surprised by the singing birds. Archimedes clock works with a system of four weights, counter weights, and strings regulated by a system of floats in a water container with siphons that regulate the automatic continuation of the clock. The principles of this type of clocks are described by the mathematician and physicist Hero,[19] who says that some of them work with a chain that turns a gear of the mechanism.[20] Another Greek clock probably constructed at the time of Alexander was in Gaza, described by Procopius.[21] The Gaza clock was probably a Meteoroskopeion, i.e. a building showing the celestial phenomena and the time. It had pointer for the time and some automations similar to the Archimedes clock. There were 12 doors opening one every hour with Hercules performing his labors, the Lion at one o’clock, etc., and at night a lamp becomes visible every hour, with 12 windows opening to show the time.

A water-powered cogwheel clock was created in China by Yi Xing and Liang Lingzan. This is not considered an escapement mechanism clock as it was unidirectional, the Song dynasty polymath and genius Su Song (1020–1101) incorporated it into his monumental innovation of the astronomical clock-tower of Kaifeng in 1088.[22][23][page needed] His astronomical clock and rotating armillary sphere still relied on the use of either flowing water during the spring, summer, autumn seasons and liquid mercury during the freezing temperature of winter (i.e. hydraulics).

In Su Song’s waterwheel linkwork device, the action of the escapement’s arrest and release was achieved by gravity exerted periodically as the continuous flow of liquid filled containers of a limited size. In a single line of evolution, Su Song’s clock therefore united the concept of the clepsydra and the mechanical clock into one device run by mechanics and hydraulics. In his memorial, Su Song wrote about this concept:

According to your servant’s opinion there have been many systems and designs for astronomical instruments during past dynasties all differing from one another in minor respects. But the principle of the use of water-power for the driving mechanism has always been the same. The heavens move without ceasing but so also does water flow (and fall). Thus if the water is made to pour with perfect evenness, then the comparison of the rotary movements (of the heavens and the machine) will show no discrepancy or contradiction; for the unresting follows the unceasing.

Song was also strongly influenced by the earlier armillary sphere created by Zhang Sixun (976 AD), who also employed the escapement mechanism and used liquid mercury instead of water in the waterwheel of his astronomical clock tower. The mechanical clockworks for Su Song’s astronomical tower featured a great driving-wheel that was 11 feet in diameter, carrying 36 scoops, into each of which water poured at a uniform rate from the «constant-level tank». The main driving shaft of iron, with its cylindrical necks supported on iron crescent-shaped bearings, ended in a pinion, which engaged a gear wheel at the lower end of the main vertical transmission shaft. This great astronomical hydromechanical clock tower was about ten metres high (about 30 feet) and featured a clock escapement and was indirectly powered by a rotating wheel either with falling water and liquid mercury. A full-sized working replica of Su Song’s clock exists in the Republic of China (Taiwan)’s National Museum of Natural Science, Taichung city. This full-scale, fully functional replica, approximately 12 meters (39 feet) in height, was constructed from Su Song’s original descriptions and mechanical drawings.[24]

In the 12th century, Al-Jazari, an engineer from Mesopotamia (lived 1136–1206) who worked for Artuqid king of Diyar-Bakr, Nasir al-Din, made numerous clocks of all shapes and sizes. The most reputed clocks included the elephant, scribe, and castle clocks, some of which have been successfully reconstructed. As well as telling the time, these grand clocks were symbols of status, grandeur and wealth of the Urtuq State.[26]

Fully mechanical[edit]

The word horologia (from the Greek ὥρα—’hour’, and λέγειν—’to tell’) was used to describe early mechanical clocks,[27] but the use of this word (still used in several Romance languages)[28] for all timekeepers conceals the true nature of the mechanisms. For example, there is a record that in 1176 Sens Cathedral in France installed an ‘horologe’[29] but the mechanism used is unknown. According to Jocelyn de Brakelond, in 1198 during a fire at the abbey of St Edmundsbury (now Bury St Edmunds), the monks «ran to the clock» to fetch water, indicating that their water clock had a reservoir large enough to help extinguish the occasional fire.[30] The word clock (via Medieval Latin clocca from Old Irish clocc, both meaning ‘bell’), which gradually supersedes «horologe», suggests that it was the sound of bells which also characterized the prototype mechanical clocks that appeared during the 13th century in Europe.

In Europe, between 1280 and 1320, there was an increase in the number of references to clocks and horologes in church records, and this probably indicates that a new type of clock mechanism had been devised. Existing clock mechanisms that used water power were being adapted to take their driving power from falling weights. This power was controlled by some form of oscillating mechanism, probably derived from existing bell-ringing or alarm devices. This controlled release of power – the escapement – marks the beginning of the true mechanical clock, which differed from the previously mentioned cogwheel clocks. Verge escapement mechanism derived in the surge of true mechanical clocks, which didn’t need any kind of fluid power, like water or mercury, to work.

These mechanical clocks were intended for two main purposes: for signalling and notification (e.g., the timing of services and public events), and for modeling the solar system. The former purpose is administrative, the latter arises naturally given the scholarly interests in astronomy, science, astrology, and how these subjects integrated with the religious philosophy of the time. The astrolabe was used both by astronomers and astrologers, and it was natural to apply a clockwork drive to the rotating plate to produce a working model of the solar system.

Simple clocks intended mainly for notification were installed in towers, and did not always require faces or hands. They would have announced the canonical hours or intervals between set times of prayer. Canonical hours varied in length as the times of sunrise and sunset shifted. The more sophisticated astronomical clocks would have had moving dials or hands, and would have shown the time in various time systems, including Italian hours, canonical hours, and time as measured by astronomers at the time. Both styles of clock started acquiring extravagant features such as automata.

In 1283, a large clock was installed at Dunstable Priory in Bedfordshire in southern England; its location above the rood screen suggests that it was not a water clock.[31] In 1292, Canterbury Cathedral installed a ‘great horloge’. Over the next 30 years there are mentions of clocks at a number of ecclesiastical institutions in England, Italy, and France. In 1322, a new clock was installed in Norwich, an expensive replacement for an earlier clock installed in 1273. This had a large (2 metre) astronomical dial with automata and bells. The costs of the installation included the full-time employment of two clockkeepers for two years.[31]

Astronomical[edit]

An elaborate water clock, the ‘Cosmic Engine’, was invented by Su Song, a Chinese polymath, designed and constructed in China in 1092. This great astronomical hydromechanical clock tower was about ten metres high (about 30 feet) and was indirectly powered by a rotating wheel with falling water and liquid mercury, which turned an armillary sphere capable of calculating complex astronomical problems.

In Europe, there were the clocks constructed by Richard of Wallingford in Albans by 1336, and by Giovanni de Dondi in Padua from 1348 to 1364. They no longer exist, but detailed descriptions of their design and construction survive,[32][33] and modern reproductions have been made.[33] They illustrate how quickly the theory of the mechanical clock had been translated into practical constructions, and also that one of the many impulses to their development had been the desire of astronomers to investigate celestial phenomena.

The Astrarium of Giovanni Dondi dell’Orologio was a complex astronomical clock built between 1348 and 1364 in Padua, Italy, by the doctor and clock-maker Giovanni Dondi dell’Orologio. The Astrarium had seven faces and 107 moving gears; it showed the positions of the sun, the moon and the five planets then known, as well as religious feast days. The astrarium stood about 1 metre high, and consisted of a seven-sided brass or iron framework resting on 7 decorative paw-shaped feet. The lower section provided a 24-hour dial and a large calendar drum, showing the fixed feasts of the church, the movable feasts, and the position in the zodiac of the moon’s ascending node. The upper section contained 7 dials, each about 30 cm in diameter, showing the positional data for the Primum Mobile, Venus, Mercury, the moon, Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars. Directly above the 24-hour dial is the dial of the Primum Mobile, so called because it reproduces the diurnal motion of the stars and the annual motion of the sun against the background of stars. Each of the ‘planetary’ dials used complex clockwork to produce reasonably accurate models of the planets’ motion. These agreed reasonably well both with Ptolemaic theory and with observations.[34][35]

Wallingford’s clock had a large astrolabe-type dial, showing the sun, the moon’s age, phase, and node, a star map, and possibly the planets. In addition, it had a wheel of fortune and an indicator of the state of the tide at London Bridge. Bells rang every hour, the number of strokes indicating the time.[32] Dondi’s clock was a seven-sided construction, 1 metre high, with dials showing the time of day, including minutes, the motions of all the known planets, an automatic calendar of fixed and movable feasts, and an eclipse prediction hand rotating once every 18 years.[33] It is not known how accurate or reliable these clocks would have been. They were probably adjusted manually every day to compensate for errors caused by wear and imprecise manufacture. Water clocks are sometimes still used today, and can be examined in places such as ancient castles and museums. The Salisbury Cathedral clock, built in 1386, is considered to be the world’s oldest surviving mechanical clock that strikes the hours.[36]

Spring-driven[edit]

- Examples of spring-driven clocks

-

Matthew Norman carriage clock with winding key

-

Decorated William Gilbert mantel clock

Clockmakers developed their art in various ways. Building smaller clocks was a technical challenge, as was improving accuracy and reliability. Clocks could be impressive showpieces to demonstrate skilled craftsmanship, or less expensive, mass-produced items for domestic use. The escapement in particular was an important factor affecting the clock’s accuracy, so many different mechanisms were tried.

Spring-driven clocks appeared during the 15th century,[37][38][39] although they are often erroneously credited to Nuremberg watchmaker Peter Henlein (or Henle, or Hele) around 1511.[40][41][42] The earliest existing spring driven clock is the chamber clock given to Phillip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, around 1430, now in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum.[5] Spring power presented clockmakers with a new problem: how to keep the clock movement running at a constant rate as the spring ran down. This resulted in the invention of the stackfreed and the fusee in the 15th century, and many other innovations, down to the invention of the modern going barrel in 1760.

Early clock dials did not indicate minutes and seconds. A clock with a dial indicating minutes was illustrated in a 1475 manuscript by Paulus Almanus,[43] and some 15th-century clocks in Germany indicated minutes and seconds.[44]

An early record of a seconds hand on a clock dates back to about 1560 on a clock now in the Fremersdorf collection.[45]: 417–418 [46]

During the 15th and 16th centuries, clockmaking flourished, particularly in the metalworking towns of Nuremberg and Augsburg, and in Blois, France. Some of the more basic table clocks have only one time-keeping hand, with the dial between the hour markers being divided into four equal parts making the clocks readable to the nearest 15 minutes. Other clocks were exhibitions of craftsmanship and skill, incorporating astronomical indicators and musical movements. The cross-beat escapement was invented in 1584 by Jost Bürgi, who also developed the remontoire. Bürgi’s clocks were a great improvement in accuracy as they were correct to within a minute a day.[47][48] These clocks helped the 16th-century astronomer Tycho Brahe to observe astronomical events with much greater precision than before.[citation needed][how?]

Lantern clock, German, c. 1570

Pendulum[edit]

The first pendulum clock, designed by Christiaan Huygens in 1656

The next development in accuracy occurred after 1656 with the invention of the pendulum clock. Galileo had the idea to use a swinging bob to regulate the motion of a time-telling device earlier in the 17th century. Christiaan Huygens, however, is usually credited as the inventor. He determined the mathematical formula that related pendulum length to time (about 99.4 cm or 39.1 inches for the one second movement) and had the first pendulum-driven clock made. The first model clock was built in 1657 in the Hague, but it was in England that the idea was taken up.[49] The longcase clock (also known as the grandfather clock) was created to house the pendulum and works by the English clockmaker William Clement in 1670 or 1671. It was also at this time that clock cases began to be made of wood and clock faces to use enamel as well as hand-painted ceramics.

In 1670, William Clement created the anchor escapement,[50] an improvement over Huygens’ crown escapement. Clement also introduced the pendulum suspension spring in 1671. The concentric minute hand was added to the clock by Daniel Quare, a London clockmaker and others, and the second hand was first introduced.

Hairspring[edit]

In 1675, Huygens and Robert Hooke invented the spiral balance spring, or the hairspring, designed to control the oscillating speed of the balance wheel. This crucial advance finally made accurate pocket watches possible. The great English clockmaker Thomas Tompion, was one of the first to use this mechanism successfully in his pocket watches, and he adopted the minute hand which, after a variety of designs were trialled, eventually stabilised into the modern-day configuration.[51] The rack and snail striking mechanism for striking clocks, was introduced during the 17th century and had distinct advantages over the ‘countwheel’ (or ‘locking plate’) mechanism. During the 20th century there was a common misconception that Edward Barlow invented rack and snail striking. In fact, his invention was connected with a repeating mechanism employing the rack and snail.[52] The repeating clock, that chimes the number of hours (or even minutes) on demand was invented by either Quare or Barlow in 1676. George Graham invented the deadbeat escapement for clocks in 1720.

Marine chronometer[edit]

A major stimulus to improving the accuracy and reliability of clocks was the importance of precise time-keeping for navigation. The position of a ship at sea could be determined with reasonable accuracy if a navigator could refer to a clock that lost or gained less than about 10 seconds per day. This clock could not contain a pendulum, which would be virtually useless on a rocking ship. In 1714, the British government offered large financial rewards to the value of 20,000 pounds[53] for anyone who could determine longitude accurately. John Harrison, who dedicated his life to improving the accuracy of his clocks, later received considerable sums under the Longitude Act.

In 1735, Harrison built his first chronometer, which he steadily improved on over the next thirty years before submitting it for examination. The clock had many innovations, including the use of bearings to reduce friction, weighted balances to compensate for the ship’s pitch and roll in the sea and the use of two different metals to reduce the problem of expansion from heat. The chronometer was tested in 1761 by Harrison’s son and by the end of 10 weeks the clock was in error by less than 5 seconds.[54]

Mass production[edit]

The British had dominated watch manufacture for much of the 17th and 18th centuries, but maintained a system of production that was geared towards high quality products for the elite.[55] Although there was an attempt to modernise clock manufacture with mass-production techniques and the application of duplicating tools and machinery by the British Watch Company in 1843, it was in the United States that this system took off. In 1816, Eli Terry and some other Connecticut clockmakers developed a way of mass-producing clocks by using interchangeable parts.[56] Aaron Lufkin Dennison started a factory in 1851 in Massachusetts that also used interchangeable parts, and by 1861 was running a successful enterprise incorporated as the Waltham Watch Company.[57][58]

Early electric[edit]

Early French electromagnetic clock

In 1815, Francis Ronalds published the first electric clock powered by dry pile batteries.[59] Alexander Bain, Scottish clockmaker, patented the electric clock in 1840. The electric clock’s mainspring is wound either with an electric motor or with an electromagnet and armature. In 1841, he first patented the electromagnetic pendulum. By the end of the nineteenth century, the advent of the dry cell battery made it feasible to use electric power in clocks. Spring or weight driven clocks that use electricity, either alternating current (AC) or direct current (DC), to rewind the spring or raise the weight of a mechanical clock would be classified as an electromechanical clock. This classification would also apply to clocks that employ an electrical impulse to propel the pendulum. In electromechanical clocks the electricity serves no time keeping function. These types of clocks were made as individual timepieces but more commonly used in synchronized time installations in schools, businesses, factories, railroads and government facilities as a master clock and slave clocks.

Where an AC electrical supply of stable frequency is available, timekeeping can be maintained very reliably by using a synchronous motor, essentially counting the cycles. The supply current alternates with an accurate frequency of 50 hertz in many countries, and 60 hertz in others. While the frequency may vary slightly during the day as the load changes, generators are designed to maintain an accurate number of cycles over a day, so the clock may be a fraction of a second slow or fast at any time, but will be perfectly accurate over a long time. The rotor of the motor rotates at a speed that is related to the alternation frequency. Appropriate gearing converts this rotation speed to the correct ones for the hands of the analog clock. Time in these cases is measured in several ways, such as by counting the cycles of the AC supply, vibration of a tuning fork, the behaviour of quartz crystals, or the quantum vibrations of atoms. Electronic circuits divide these high-frequency oscillations to slower ones that drive the time display.

Quartz[edit]

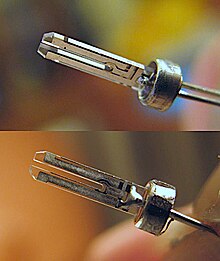

Picture of a quartz crystal resonator, used as the timekeeping component in quartz watches and clocks, with the case removed. It is formed in the shape of a tuning fork. Most such quartz clock crystals vibrate at a frequency of 32768 Hz.

The piezoelectric properties of crystalline quartz were discovered by Jacques and Pierre Curie in 1880.[60][61] The first crystal oscillator was invented in 1917 by Alexander M. Nicholson, after which the first quartz crystal oscillator was built by Walter G. Cady in 1921.[3] In 1927 the first quartz clock was built by Warren Marrison and J.W. Horton at Bell Telephone Laboratories in Canada.[62][3] The following decades saw the development of quartz clocks as precision time measurement devices in laboratory settings—the bulky and delicate counting electronics, built with vacuum tubes at the time, limited their practical use elsewhere. The National Bureau of Standards (now NIST) based the time standard of the United States on quartz clocks from late 1929 until the 1960s, when it changed to atomic clocks.[63] In 1969, Seiko produced the world’s first quartz wristwatch, the Astron.[64] Their inherent accuracy and low cost of production resulted in the subsequent proliferation of quartz clocks and watches.[60]

Atomic[edit]

Currently, atomic clocks are the most accurate clocks in existence. They are considerably more accurate than quartz clocks as they can be accurate to within a few seconds over trillions of years.[65][66] Atomic clocks were first theorized by Lord Kelvin in 1879.[67] In the 1930s the development of magnetic resonance created practical method for doing this.[68] A prototype ammonia maser device was built in 1949 at the U.S. National Bureau of Standards (NBS, now NIST). Although it was less accurate than existing quartz clocks, it served to demonstrate the concept.[69][70][71] The first accurate atomic clock, a caesium standard based on a certain transition of the caesium-133 atom, was built by Louis Essen in 1955 at the National Physical Laboratory in the UK.[72] Calibration of the caesium standard atomic clock was carried out by the use of the astronomical time scale ephemeris time (ET).[73] As of 2013, the most stable atomic clocks are ytterbium clocks, which are stable to within less than two parts in 1 quintillion (2×10−18).[74]

Operation[edit]

The invention of the mechanical clock in the 13th century initiated a change in timekeeping methods from continuous processes, such as the motion of the gnomon’s shadow on a sundial or the flow of liquid in a water clock, to periodic oscillatory processes, such as the swing of a pendulum or the vibration of a quartz crystal,[4][75] which had the potential for more accuracy. All modern clocks use oscillation.

Although the mechanisms they use vary, all oscillating clocks, mechanical, electric, and atomic, work similarly and can be divided into analogous parts.[76][77][78] They consist of an object that repeats the same motion over and over again, an oscillator, with a precisely constant time interval between each repetition, or ‘beat’. Attached to the oscillator is a controller device, which sustains the oscillator’s motion by replacing the energy it loses to friction, and converts its oscillations into a series of pulses. The pulses are then counted by some type of counter, and the number of counts is converted into convenient units, usually seconds, minutes, hours, etc. Finally some kind of indicator displays the result in human readable form.

Power source[edit]

- In mechanical clocks, the power source is typically either a weight suspended from a cord or chain wrapped around a pulley, sprocket or drum; or a spiral spring called a mainspring. Mechanical clocks must be wound periodically, usually by turning a knob or key or by pulling on the free end of the chain, to store energy in the weight or spring to keep the clock running.

- In electric clocks, the power source is either a battery or the AC power line. In clocks that use AC power, a small backup battery is often included to keep the clock running if it is unplugged temporarily from the wall or during a power outage. Battery-powered analog wall clocks are available that operate over 15 years between battery changes.

Oscillator[edit]

The timekeeping element in every modern clock is a harmonic oscillator, a physical object (resonator) that vibrates or oscillates repetitively at a precisely constant frequency.[3][79][80][81]

- In mechanical clocks, this is either a pendulum or a balance wheel.

- In some early electronic clocks and watches such as the Accutron, it is a tuning fork.

- In quartz clocks and watches, it is a quartz crystal.

- In atomic clocks, it is the vibration of electrons in atoms as they emit microwaves.

- In early mechanical clocks before 1657, it was a crude balance wheel or foliot which was not a harmonic oscillator because it lacked a balance spring. As a result, they were very inaccurate, with errors of perhaps an hour a day.[82]

The advantage of a harmonic oscillator over other forms of oscillator is that it employs resonance to vibrate at a precise natural resonant frequency or «beat» dependent only on its physical characteristics, and resists vibrating at other rates. The possible precision achievable by a harmonic oscillator is measured by a parameter called its Q,[83][84] or quality factor, which increases (other things being equal) with its resonant frequency.[85] This is why there has been a long-term trend toward higher frequency oscillators in clocks. Balance wheels and pendulums always include a means of adjusting the rate of the timepiece. Quartz timepieces sometimes include a rate screw that adjusts a capacitor for that purpose. Atomic clocks are primary standards, and their rate cannot be adjusted.

Synchronized or slave clocks[edit]

Some clocks rely for their accuracy on an external oscillator; that is, they are automatically synchronized to a more accurate clock:

- Slave clocks, used in large institutions and schools from the 1860s to the 1970s, kept time with a pendulum, but were wired to a master clock in the building, and periodically received a signal to synchronize them with the master, often on the hour.[86] Later versions without pendulums were triggered by a pulse from the master clock and certain sequences used to force rapid synchronization following a power failure.

Synchronous electric clock, around 1940. By 1940 the synchronous clock became the most common type of clock in the U.S.

- Synchronous electric clocks do not have an internal oscillator, but count cycles of the 50 or 60 Hz oscillation of the AC power line, which is synchronized by the utility to a precision oscillator. The counting may be done electronically, usually in clocks with digital displays, or, in analog clocks, the AC may drive a synchronous motor which rotates an exact fraction of a revolution for every cycle of the line voltage, and drives the gear train. Although changes in the grid line frequency due to load variations may cause the clock to temporarily gain or lose several seconds during the course of a day, the total number of cycles per 24 hours is maintained extremely accurately by the utility company, so that the clock keeps time accurately over long periods.

- Computer real-time clocks keep time with a quartz crystal, but can be periodically (usually weekly) synchronized over the Internet to atomic clocks (UTC), using the Network Time Protocol (NTP).

- Radio clocks keep time with a quartz crystal, but are periodically synchronized to time signals transmitted from dedicated standard time radio stations or satellite navigation signals, which are set by atomic clocks.

Controller[edit]

This has the dual function of keeping the oscillator running by giving it ‘pushes’ to replace the energy lost to friction, and converting its vibrations into a series of pulses that serve to measure the time.

- In mechanical clocks, this is the escapement, which gives precise pushes to the swinging pendulum or balance wheel, and releases one gear tooth of the escape wheel at each swing, allowing all the clock’s wheels to move forward a fixed amount with each swing.

- In electronic clocks this is an electronic oscillator circuit that gives the vibrating quartz crystal or tuning fork tiny ‘pushes’, and generates a series of electrical pulses, one for each vibration of the crystal, which is called the clock signal.

- In atomic clocks the controller is an evacuated microwave cavity attached to a microwave oscillator controlled by a microprocessor. A thin gas of caesium atoms is released into the cavity where they are exposed to microwaves. A laser measures how many atoms have absorbed the microwaves, and an electronic feedback control system called a phase-locked loop tunes the microwave oscillator until it is at the frequency that causes the atoms to vibrate and absorb the microwaves. Then the microwave signal is divided by digital counters to become the clock signal.[87]

In mechanical clocks, the low Q of the balance wheel or pendulum oscillator made them very sensitive to the disturbing effect of the impulses of the escapement, so the escapement had a great effect on the accuracy of the clock, and many escapement designs were tried. The higher Q of resonators in electronic clocks makes them relatively insensitive to the disturbing effects of the drive power, so the driving oscillator circuit is a much less critical component.[3]

Counter chain[edit]

This counts the pulses and adds them up to get traditional time units of seconds, minutes, hours, etc. It usually has a provision for setting the clock by manually entering the correct time into the counter.

- In mechanical clocks this is done mechanically by a gear train, known as the wheel train. The gear train also has a second function; to transmit mechanical power from the power source to run the oscillator. There is a friction coupling called the ‘cannon pinion’ between the gears driving the hands and the rest of the clock, allowing the hands to be turned to set the time.[88]

- In digital clocks a series of integrated circuit counters or dividers add the pulses up digitally, using binary logic. Often pushbuttons on the case allow the hour and minute counters to be incremented and decremented to set the time.

Indicator[edit]

A cuckoo clock with mechanical automaton and sound producer striking on the eighth hour on the analog dial

This displays the count of seconds, minutes, hours, etc. in a human readable form.

- The earliest mechanical clocks in the 13th century did not have a visual indicator and signalled the time audibly by striking bells. Many clocks to this day are striking clocks which strike the hour.

- Analog clocks display time with an analog clock face, which consists of a dial with the numbers 1 through 12 or 24, the hours in the day, around the outside. The hours are indicated with an hour hand, which makes one or two revolutions in a day, while the minutes are indicated by a minute hand, which makes one revolution per hour. In mechanical clocks a gear train drives the hands; in electronic clocks the circuit produces pulses every second which drive a stepper motor and gear train, which move the hands.

- Digital clocks display the time in periodically changing digits on a digital display. A common misconception is that a digital clock is more accurate than an analog wall clock, but the indicator type is separate and apart from the accuracy of the timing source.

- Talking clocks and the speaking clock services provided by telephone companies speak the time audibly, using either recorded or digitally synthesized voices.

Types[edit]

Clocks can be classified by the type of time display, as well as by the method of timekeeping.

Time display methods[edit]

Analog[edit]

A modern quartz clock with a 24-hour face

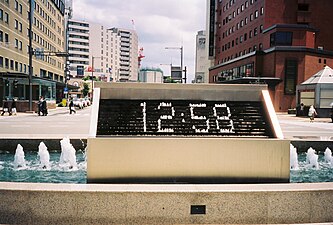

A linear clock at London’s Piccadilly Circus tube station. The 24 hour band moves across the static map, keeping pace with the apparent movement of the sun above ground, and a pointer fixed on London points to the current time.

Analog clocks usually use a clock face which indicates time using rotating pointers called «hands» on a fixed numbered dial or dials. The standard clock face, known universally throughout the world, has a short «hour hand» which indicates the hour on a circular dial of 12 hours, making two revolutions per day, and a longer «minute hand» which indicates the minutes in the current hour on the same dial, which is also divided into 60 minutes. It may also have a «second hand» which indicates the seconds in the current minute. The only other widely used clock face today is the 24 hour analog dial, because of the use of 24 hour time in military organizations and timetables. Before the modern clock face was standardized during the Industrial Revolution, many other face designs were used throughout the years, including dials divided into 6, 8, 10, and 24 hours. During the French Revolution the French government tried to introduce a 10-hour clock, as part of their decimal-based metric system of measurement, but it did not achieve widespread use. An Italian 6 hour clock was developed in the 18th century, presumably to save power (a clock or watch striking 24 times uses more power).

Another type of analog clock is the sundial, which tracks the sun continuously, registering the time by the shadow position of its gnomon. Because the sun does not adjust to daylight saving time, users must add an hour during that time. Corrections must also be made for the equation of time, and for the difference between the longitudes of the sundial and of the central meridian of the time zone that is being used (i.e. 15 degrees east of the prime meridian for each hour that the time zone is ahead of GMT). Sundials use some or part of the 24 hour analog dial. There also exist clocks which use a digital display despite having an analog mechanism—these are commonly referred to as flip clocks. Alternative systems have been proposed. For example, the «Twelv» clock indicates the current hour using one of twelve colors, and indicates the minute by showing a proportion of a circular disk, similar to a moon phase.[89]

Digital[edit]

- Examples of digital clocks

-

Digital clock displaying time by controlling valves on the fountain

-

Simplistic digital clock radio

-

Diagram of a mechanical digital display of a flip clock

Digital clocks display a numeric representation of time. Two numeric display formats are commonly used on digital clocks:

- the 24-hour notation with hours ranging 00–23;

- the 12-hour notation with AM/PM indicator, with hours indicated as 12AM, followed by 1AM–11AM, followed by 12PM, followed by 1PM–11PM (a notation mostly used in domestic environments).

Most digital clocks use electronic mechanisms and LCD, LED, or VFD displays; many other display technologies are used as well (cathode-ray tubes, nixie tubes, etc.). After a reset, battery change or power failure, these clocks without a backup battery or capacitor either start counting from 12:00, or stay at 12:00, often with blinking digits indicating that the time needs to be set. Some newer clocks will reset themselves based on radio or Internet time servers that are tuned to national atomic clocks. Since the introduction of digital clocks in the 1960s, there has been a notable decline in the use of analog clocks.[90]

Some clocks, called ‘flip clocks’, have digital displays that work mechanically. The digits are painted on sheets of material which are mounted like the pages of a book. Once a minute, a page is turned over to reveal the next digit. These displays are usually easier to read in brightly lit conditions than LCDs or LEDs. Also, they do not go back to 12:00 after a power interruption. Flip clocks generally do not have electronic mechanisms. Usually, they are driven by AC-synchronous motors.

Hybrid (analog-digital)[edit]

Clocks with analog quadrants, with a digital component, usually minutes and hours displayed analogously and seconds displayed in digital mode.

Auditory[edit]

For convenience, distance, telephony or blindness, auditory clocks present the time as sounds. The sound is either spoken natural language, (e.g. «The time is twelve thirty-five»), or as auditory codes (e.g. number of sequential bell rings on the hour represents the number of the hour like the bell, Big Ben). Most telecommunication companies also provide a speaking clock service as well.

Word[edit]

Word clocks are clocks that display the time visually using sentences. E.g.: «It’s about three o’clock.» These clocks can be implemented in hardware or software.

Projection[edit]

Some clocks, usually digital ones, include an optical projector that shines a magnified image of the time display onto a screen or onto a surface such as an indoor ceiling or wall. The digits are large enough to be easily read, without using glasses, by persons with moderately imperfect vision, so the clocks are convenient for use in their bedrooms. Usually, the timekeeping circuitry has a battery as a backup source for an uninterrupted power supply to keep the clock on time, while the projection light only works when the unit is connected to an A.C. supply. Completely battery-powered portable versions resembling flashlights are also available.

Tactile[edit]

Auditory and projection clocks can be used by people who are blind or have limited vision. There are also clocks for the blind that have displays that can be read by using the sense of touch. Some of these are similar to normal analog displays, but are constructed so the hands can be felt without damaging them. Another type is essentially digital, and uses devices that use a code such as Braille to show the digits so that they can be felt with the fingertips.

Multi-display[edit]

Some clocks have several displays driven by a single mechanism, and some others have several completely separate mechanisms in a single case. Clocks in public places often have several faces visible from different directions, so that the clock can be read from anywhere in the vicinity; all the faces show the same time. Other clocks show the current time in several time-zones. Watches that are intended to be carried by travellers often have two displays, one for the local time and the other for the time at home, which is useful for making pre-arranged phone calls. Some equation clocks have two displays, one showing mean time and the other solar time, as would be shown by a sundial. Some clocks have both analog and digital displays. Clocks with Braille displays usually also have conventional digits so they can be read by sighted people.

Purposes[edit]

Many cities and towns traditionally have public clocks in a prominent location, such as a town square or city center. This one is on display at the center of the town of Robbins, North Carolina

Clocks are in homes, offices and many other places; smaller ones (watches) are carried on the wrist or in a pocket; larger ones are in public places, e.g. a railway station or church. A small clock is often shown in a corner of computer displays, mobile phones and many MP3 players.

The primary purpose of a clock is to display the time. Clocks may also have the facility to make a loud alert signal at a specified time, typically to waken a sleeper at a preset time; they are referred to as alarm clocks. The alarm may start at a low volume and become louder, or have the facility to be switched off for a few minutes then resume. Alarm clocks with visible indicators are sometimes used to indicate to children too young to read the time that the time for sleep has finished; they are sometimes called training clocks.

A clock mechanism may be used to control a device according to time, e.g. a central heating system, a VCR, or a time bomb (see: digital counter). Such mechanisms are usually called timers. Clock mechanisms are also used to drive devices such as solar trackers and astronomical telescopes, which have to turn at accurately controlled speeds to counteract the rotation of the Earth.

Most digital computers depend on an internal signal at constant frequency to synchronize processing; this is referred to as a clock signal. (A few research projects are developing CPUs based on asynchronous circuits.) Some equipment, including computers, also maintains time and date for use as required; this is referred to as time-of-day clock, and is distinct from the system clock signal, although possibly based on counting its cycles.

In Chinese culture, giving a clock (traditional Chinese: 送鐘; simplified Chinese: 送钟; pinyin: sòng zhōng) is often taboo, especially to the elderly as the term for this act is a homophone with the term for the act of attending another’s funeral (traditional Chinese: 送終; simplified Chinese: 送终; pinyin: sòngzhōng).[91][92][93]

This homonymic pair works in both Mandarin and Cantonese, although in most parts of China only clocks and large bells, and not watches, are called «zhong«, and watches are commonly given as gifts in China.

However, should such a gift be given, the «unluckiness» of the gift can be countered by exacting a small monetary payment so the recipient is buying the clock and thereby counteracting the ‘送’ («give») expression of the phrase.

Time standards[edit]

For some scientific work timing of the utmost accuracy is essential. It is also necessary to have a standard of the maximum accuracy against which working clocks can be calibrated. An ideal clock would give the time to unlimited accuracy, but this is not realisable. Many physical processes, in particular including some transitions between atomic energy levels, occur at exceedingly stable frequency; counting cycles of such a process can give a very accurate and consistent time—clocks which work this way are usually called atomic clocks. Such clocks are typically large, very expensive, require a controlled environment, and are far more accurate than required for most purposes; they are typically used in a standards laboratory.

Navigation[edit]

Until advances in the late twentieth century, navigation depended on the ability to measure latitude and longitude. Latitude can be determined through celestial navigation; the measurement of longitude requires accurate knowledge of time. This need was a major motivation for the development of accurate mechanical clocks. John Harrison created the first highly accurate marine chronometer in the mid-18th century. The Noon gun in Cape Town still fires an accurate signal to allow ships to check their chronometers. Many buildings near major ports used to have (some still do) a large ball mounted on a tower or mast arranged to drop at a pre-determined time, for the same purpose. While satellite navigation systems such as GPS require unprecedentedly accurate knowledge of time, this is supplied by equipment on the satellites; vehicles no longer need timekeeping equipment.

Specific types[edit]

A monumental conical pendulum clock by Eugène Farcot, 1867. Drexel University, Philadelphia, USA

| By mechanism | By function | By style |

|

|

|

See also[edit]

- 24-hour analog dial

- Allan variance

- Allen-Bradley Clock Tower at Rockwell Automation Headquarters Building (Wisconsin)

- American Watchmakers-Clockmakers Institute

- BaselWorld

- Biological clock

- Castle clock

- Clockarium

- Clock as herald of the Industrial Revolution (Lewis Mumford)

- Clock face

- Clock drift

- Clock ident

- Clock network

- Clock of the Long Now

- Clock signal (digital circuits)

- Clockkeeper

- Clockmaker

- Colgate Clock (Indiana)

- Colgate Clock (New Jersey), largest clock in USA

- Corpus Clock

- Cosmo Clock 21, world’s largest clock

- Cox’s timepiece

- Cuckooland Museum

- Date and time representation by country

- Debt clock

- Le Défenseur du Temps (automata)

- Department of Defense master clock (U.S.)

- Doomsday Clock

- Earth clock

- Equation clock

- Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry FH

- Guard tour patrol system (watchclocks)

- Iron Ring Clock

- Jens Olsen’s World Clock

- Jewel bearing

- List of biggest clock faces

- List of clocks

- List of international common standards

- List of largest cuckoo clocks

- Metrology

- Mora clock

- National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors

- Projection clock

- Replica watch

- Rubik’s Clock

- Star clock

- Singing bird box

- System time

- Time to digital converter

- Timeline of time measurement technology

- Timer

- Watch

- Watchmaker

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ see: Baillie et al., p. 307; Palmer, p. 19; Zea & Cheney, p. 172.

- ^ Dohrn-van Rossum, Gerhard (1996). History of the Hour: Clocks and Modern Temporal Orders. Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-15511-1., pp. 103–104.

- ^ a b c d e f Marrison, Warren (1948). «The Evolution of the Quartz Crystal Clock» (PDF). Bell System Technical Journal. 27 (3): 510–588. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01343.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 10, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ^ a b Cipolla, Carlo M. (2004). Clocks and Culture, 1300 to 1700. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-32443-3., p. 31.

- ^ a b White, Lynn, Jr. (1962). Medieval Technology and Social Change. UK: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 119.

- ^ «Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary». Retrieved January 29, 2018.

a device for measuring and showing time, which is usually found in or on a building and is not worn by a person

- ^ Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1859). A Dictionary of English Etymology: A – D, Vol. 1. London: Trübner and Co. p. 354.

- ^ Stevenson, Angus; Waite, Maurice (2011). Concise Oxford English Dictionary: Luxury Edition. Oxford University. pp. 269–270. ISBN 9780199601110.

- ^ «Clock». Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ «How Sundials Work». The British Sundial Society. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ^ «Ancient Sundials». North American Sundial Society. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ^ Sara Schecner Genuth, «Sundials», in John Lankford and Marc Rothenberg, eds., History of Astronomy: An Encyclopedia (London: Taylor & Francis, 1997), 502–3.

ISBN 9780815303220 https://books.google.com/books?id=Xev7zOrwLHgC&pg=PA502 - ^ Turner 1984, p. 1

- ^ Cowan 1958, p. 58

- ^ «Tower of the Winds – Athens».

- ^ James, Peter (1995). Ancient Inventions. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-345-40102-1.

- ^ William Godwin (1876). Lives of the Necromancers. London, F.J. Mason. p. 232.

- ^ Moussas, Xenophon (2018). The Antikythera Mechanism, the first mechanical cosmos (in Greek). Athens: Canto Mediterraneo. ISBN 978-618-83695-0-4.

- ^ Dasypodius, K. (1580). Heron mechanicus.

- ^ Hero, of Alexandria. see Hero’s books: Pneumatica (Πνευματικά), Automata, Mechanica, Metrica, Dioptra. Alexandria.

- ^ Procopius of Caesarea, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς (c. 500s). Περὶ Κτισμάτων, Perì Ktismáton; Latin: De Aedificiis, On Buildings.

- ^ «No. 120: Su-Sung’s Clock». www.uh.edu. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ History of Song 宋史, Vol. 340

- ^ «Past Masters: The Astronomical Water Clock Of Su Song». revolutionwatch.com. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

- ^ Ibn al-Razzaz Al-Jazari (ed. 1974), The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices. Translated and annotated by Donald Routledge Hill, Dordrecht/D. Reidel.

- ^ «Remaking History: Ismail al-Jazari and the Elephant Water Clock — Make». Make: DIY Projects and Ideas for Makers. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ Leonhard Schmitz; Smith, William (1875). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. London: John Murray. pp. 615‑617.

- ^ Modern French horloge is very close; Spanish reloj and Portuguese relógio drop the first part of the word.

- ^ Bulletin de la société archéologique de Sens, year 1867, vol. IX, p. 390, available at www.archive.org. See also fr:Discussion:Horloge

- ^ The Chronicle of Jocelin of Brakelond, Monk of St. Edmundsbury: A Picture of Monastic and Social Life on the XIIth Century. London: Chatto and Windus. Translated and edited by L.C. Jane. 1910.

- ^ a b «Clocks – Crystalinks». www.crystalinks.com. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ a b North, John. God’s Clockmaker: Richard of Wallingford and the Invention of Time. London: Hambledon and London (2005).

- ^ a b c King, Henry «Geared to the Stars: the evolution of planetariums, orreries, and astronomical clocks», University of Toronto Press, 1978

- ^ «Giovanni Dondi’s Astrarium, 1364 | cabinet». www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ Abrams, Melanie (February 16, 2018). «‘The Beauty of Time’«. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ Singer, Charles, et al. Oxford History of Technology: volume II, from the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution (OUP 1957) pp. 650–651

- ^ White, Lynn Jr. (1966). Medieval Technology and Social Change. New York: Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-0-19-500266-9.

- ^ Usher, Abbot Payson (1988). A History of Mechanical Inventions. Courier Dover. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-486-25593-4.

- ^ Dohrn-van Rossum, Gerhar (1997). History of the Hour: Clocks and Modern Temporal Orders. Univ. of Chicago Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-226-15510-4.

- ^ Milham, Willis I. (1945). Time and Timekeepers. New York: MacMillan. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-7808-0008-3.

- ^ «Clock». The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4. Univ. of Chicago. 1974. p. 747. ISBN 978-0-85229-290-7.

- ^ Anzovin, Steve; Podell, Janet (2000). Famous First Facts: A record of first happenings, discoveries, and inventions in world history. H.W. Wilson. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-8242-0958-2.

- ^ p. 529, «Time and timekeeping instruments», History of astronomy: an encyclopedia, John Lankford, Taylor & Francis, 1997, ISBN 0-8153-0322-X.

- ^ Usher, Abbott Payson (1988). A history of mechanical inventions. Courier Dover Publications. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-486-25593-4.

- ^ Landes, David S. (1983). Revolution in Time. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-76802-4.

- ^ Willsberger, Johann (1975). Clocks & watches. New York: Dial Press. ISBN 978-0-8037-4475-2. full page color photo: 4th caption page, 3rd photo thereafter (neither pages nor photos are numbered).

- ^ Lance Day; Ian McNeil, eds. (1996). Biographical dictionary of the history of technology. Routledge (Routledge Reference). p. 116. ISBN 978-0-415-06042-4.

- ^ Table clock c. 1650 attributed to Hans Buschmann that uses technical inventions by Jost Bürgi, The British Museum, retrieved April 11, 2010

- ^ «History of Clocks».

- ^ «The History of Mechanical Pendulum Clocks and Quartz Clocks». about.com. 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ «History Of Clocks».

- ^ Horological Journal, September 2011, pp. 408–412.

- ^ John S. Rigden (2003). Hydrogen: The Essential Element. Harvard University Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-674-01252-3.

- ^ Gould, Rupert T. (1923). The Marine Chronometer. Its History and Development. London: J.D. Potter. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-907462-05-7.

- ^ Glasmeier, Amy (2000). Manufacturing Time: Global Competition in the Watch Industry, 1795–2000. Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-57230-589-2. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ^ «Eli Terry Mass-Produced Box Clock.» Smithsonian The National Museum of American History. Web. 21 Sep. 2015.

- ^ Roe, Joseph Wickham (1916), English and American Tool Builders, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, LCCN 16011753. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (LCCN 27-24075); and by Lindsay Publications, Inc., Bradley, Illinois, (ISBN 978-0-917914-73-7).

- ^ Thomson, Ross (2009). Structures of Change in the Mechanical Age: Technological Invention in the United States 1790–1865. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8018-9141-0.

- ^ Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- ^ a b «A Revolution in Timekeeping». NIST. Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

- ^ «Pierre Curie». American Institute of Physics. Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- ^ Marrison, W.A.; Horton, J.W. (February 1928). «Precision determination of frequency». I.R.E. Proc. 16 (2): 137–154. doi:10.1109/JRPROC.1928.221372. S2CID 51664900.

- ^ Sullivan, D.B. (2001). «Time and frequency measurement at NIST: The first 100 years» (PDF). Time and Frequency Division, National Institute of Standards and Technology. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2011.

- ^ «Electronic Quartz Wristwatch, 1969». IEEE History Center. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ^ Dick, Stephen (2002). Sky and Ocean Joined: The U.S. Naval Observatory, 1830–2000. Cambridge University Press. p. 484. ISBN 978-0-521-81599-4.

- ^ Ost, Laura (August 22, 2013). «NIST Ytterbium Atomic Clocks Set Record for Stability». NIST. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ Sir William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) and Peter Guthrie Tait, Treatise on Natural Philosophy, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1879), vol. 1, part 1, p. 227.

- ^ M.A. Lombardi; T.P. Heavner; S.R. Jefferts (2007). «NIST Primary Frequency Standards and the Realization of the SI Second» (PDF). Journal of Measurement Science. 2 (4): 74. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 24, 2008.

- ^ Sullivan, D.B. (2001). Time and frequency measurement at NIST: The first 100 years (PDF). 2001 IEEE International Frequency Control Symposium. NIST. pp. 4–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2011.

- ^ «Time and Frequency Division». National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on April 15, 2008. Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- ^ «The «Atomic Age» of Time Standards». National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on April 12, 2008. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- ^

Essen, L.; Parry, J.V.L. (1955). «An Atomic Standard of Frequency and Time Interval: A Cæsium Resonator». Nature. 176 (4476): 280. Bibcode:1955Natur.176..280E. doi:10.1038/176280a0. S2CID 4191481. - ^

W. Markowitz; R.G. Hall; L. Essen; J.V.L. Parry (1958). «Frequency of cesium in terms of ephemeris time». Physical Review Letters. 1 (3): 105–107. Bibcode:1958PhRvL…1..105M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.1.105. - ^ Ost, Laura (August 22, 2013). «NIST Ytterbium Atomic Clocks Set Record for Stability». NIST. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ Marrison, Warren A. (July 1948). «The Evolution of the Quartz Crystal Clock». Bell System Tech. J. 27 (3): 511–515. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01343.x. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ Jespersen, James; Fitz-Randolph, Jane; Robb, John (1999). From Sundials to Atomic Clocks: Understanding Time and Frequency. New York: Courier Dover. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-486-40913-9.

- ^ «How clocks work». InDepthInfo. W. J. Rayment. 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ Milham, Willis I. (1945). Time and Timekeepers. New York: MacMillan. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-7808-0008-3.

- ^ Mondschein, Kenneth (2020). On Time: A History of Western Timekeeping. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 88. ISBN 9781421438276.

- ^ «Mechanics: Simple harmonic oscillations». Encyclopedia Britannica online. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 2020. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ Bloomfield, Louis (2007). How Everything Works: Making Physics Out of the Ordinary. Wiley. p. 296. ISBN 9780470170663.

- ^ Milham, 1945, p. 85

- ^ «Quality factor, Q». Glossary. Time and Frequency Division, NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). 2008. Archived from the original on May 4, 2008. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ Jespersen, James; Fitz-Randolph, Jane (January 1999). Jespersen 1999, pp. 47–50. ISBN 9780486409139.

- ^ Riehle, Fritz (2004). Frequency Standards: Basics and Applications. Frequency Standards: Basics and Applications. Germany: Wiley VCH Verlag & Co. p. 9. Bibcode:2004fsba.book…..R. ISBN 978-3-527-40230-4.

- ^ Milham, 1945, pp. 325–328

- ^ Jespersen, James; Fitz-Randolph, Jane (January 1999). Jespersen 1999, pp. 52–62. ISBN 9780486409139.

- ^ Milham, 1945, p. 113

- ^ U.S. Patent 7,079,452, U.S. Patent 7,221,624

- ^ Sadraey, Mohammad H. (2020). Design of Unmanned Aerial Systems. John Wiley & Sons. p. 332. ISBN 978-1119508700.

- ^ Brown, Ju (2006). China, Japan, Korea Culture and Customs. p. 57.

- ^ Seligman, Scott D. (1999). Chinese business etiquette:: a guide to protocol, manners, and culture in the People’s Republic of China. Hachette Digital, Inc.

- ^ http://www.sohu.com/a/160882715_578225 Archived January 5, 2018, at the Wayback Machine 别人过节喜庆的时候,不送钟表。送终和送钟谐音。

Bibliography[edit]

- Baillie, G.H., O. Clutton, & C.A. Ilbert. Britten’s Old Clocks and Watches and Their Makers (7th ed.). Bonanza Books (1956).

- Bolter, David J. Turing’s Man: Western Culture in the Computer Age. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC (1984). ISBN 0-8078-4108-0 pbk. Summary of the role of «the clock» in its setting the direction of philosophic movement for the «Western World». Cf. picture on p. 25 showing the verge and foliot. Bolton derived the picture from Macey, p. 20.

- Bruton, Eric (1982). The History of Clocks and Watches. New York: Crescent Books Distributed by Crown. ISBN 978-0-517-37744-4.

- Cowan, Harrison J. (1958). Time and Its Measurement: From the stone age to the nuclear age. Ohio: The World Publishing Company. Bibcode:1958tmfs.book…..C.

- Dohrn-van Rossum, Gerhard (1996). History of the Hour: Clocks and Modern Temporal Orders. Trans. Thomas Dunlap. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-15510-4.

- Edey, Winthrop. French Clocks. New York: Walker & Co. (1967).

- Kak, Subhash, Babylonian and Indian Astronomy: Early Connections. 2003.

- Kumar, Narendra «Science in Ancient India» (2004). ISBN 81-261-2056-8.

- Landes, David S. Revolution in Time: Clocks and the Making of the Modern World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (1983).

- Landes, David S. Clocks & the Wealth of Nations, Daedalus Journal, Spring 2003.

- Lloyd, Alan H. «Mechanical Timekeepers», A History of Technology, Vol. III. Edited by Charles Joseph Singer et al. Oxford: Clarendon Press (1957), pp. 648–675.

- Macey, Samuel L., Clocks and the Cosmos: Time in Western Life and Thought, Archon Books, Hamden, Conn. (1980).

- Needham, Joseph (2000) [1965]. Science & Civilisation in China, Vol. 4, Part 2: Mechanical Engineering. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-05803-2.

- North, John. God’s Clockmaker: Richard of Wallingford and the Invention of Time. London: Hambledon and London (2005).

- Palmer, Brooks. The Book of American Clocks, The Macmillan Co. (1979).

- Robinson, Tom. The Longcase Clock. Suffolk, England: Antique Collector’s Club (1981).

- Smith, Alan. The International Dictionary of Clocks. London: Chancellor Press (1996).

- Tardy. French Clocks the World Over. Part I and II. Translated with the assistance of Alexander Ballantyne. Paris: Tardy (1981).

- Turner, Anthony J. (1984). The Time Museum. Vol. I: Time Measuring Instruments. Rockford, IL: The Museum. ISBN 0-912947-01-2. OCLC 159866762.

- Yoder, Joella Gerstmeyer. Unrolling Time: Christiaan Huygens and the Mathematization of Nature. New York: Cambridge University Press (1988).

- Zea, Philip, & Robert Cheney. Clock Making in New England: 1725–1825. Old Sturbridge Village (1992).

External links[edit]

This audio file was created from a revision of this article dated 16 July 2019, and does not reflect subsequent edits.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clocks.

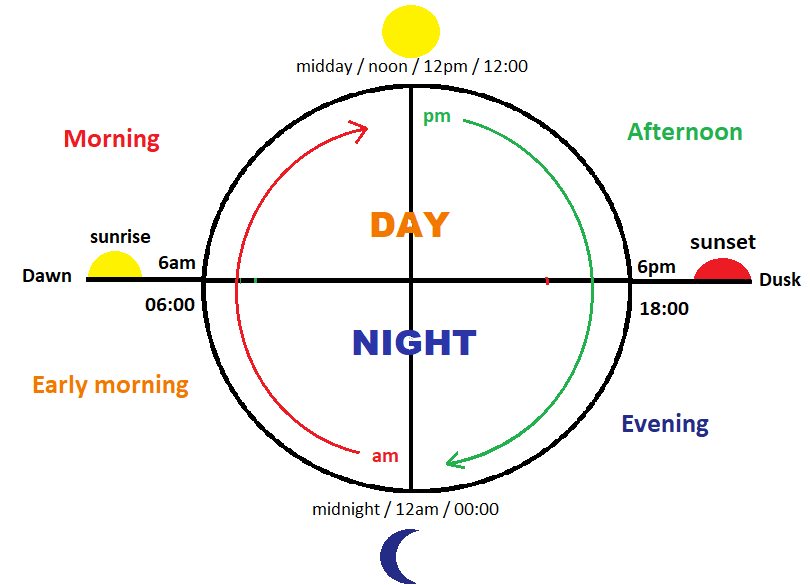

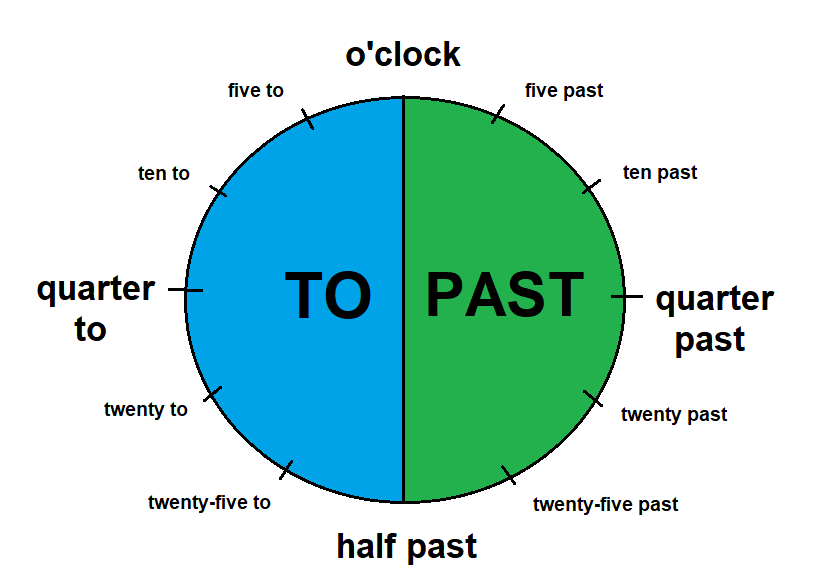

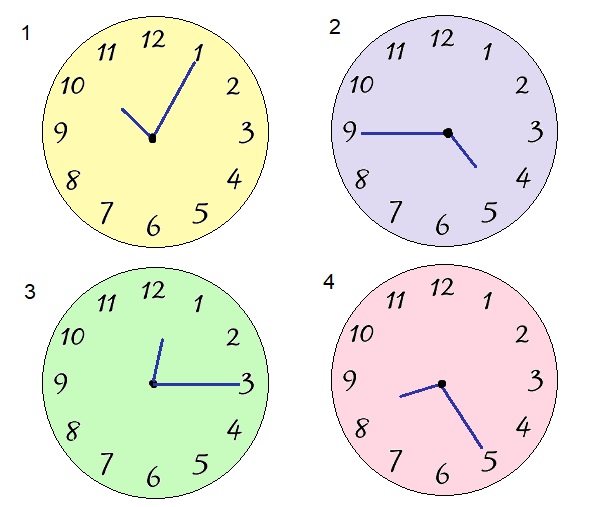

Время на английском

Главная>Прочие материалы>Время на английском языке

Время на английском языке. Часы на английском. Как ответить сколько время или который час?

Здесь вы можете найти время на английском языке. Часы на английском. Как ответить сколько время или который час?