The written word is my way

To express just how I feel.

Moments lived and memories

Are shared in what I say.

Most of them are sadness,

Expressing life I’ve lived.

Moments that I can’t forget,

Are all I have to give.

My poems are my footprint.

That I can leave behind.

They will live forever

Expressing moments in mind.

The written word. It helps me see.

Lessons that I have learned.

They remind me that I’m really strong

And my respect’s been finally earned.

Yes, they are of sadness.

Yes they are of pain.

The written word it keeps me safe,

So I don’t go insane.

The written word. It helps my soul,

And let’s the darkness pass.

Simple words that say so much,

Is all this poet has.

The Written Word

written by: Anne G

@TheInkTruth

Fertile font

of truth and lies

Bastian

of creative birth

Inception

of a conscious mind

Transcendence

of the written word

- About

- Latest Posts

Anne G

JUNE 2016 AUTHOR OF THE MONTH at Spillwords.com

Why write?

I write because I am:

Driven to distraction by the inequities of the society in which we live.

Motivated by cruelty, abuse, ignorance and indifference.

My intention: To poke, prod and provoke!

«Moderation is a fatal thing. Nothing succeeds like excess.» — Oscar Wilde

Latest posts by Anne G (see all)

- Depository of Emotions — March 28, 2022

- Boycott! — February 13, 2022

- The Fissured Heart — June 16, 2021

To learn how to write a poem step-by-step, let’s start where all poets start: the basics.

This article is an in-depth introduction to how to write a poem. We first answer the question, “What is poetry?” We then discuss the literary elements of poetry, and showcase some different approaches to the writing process—including our own seven-step process on how to write a poem step by step.

So, how do you write a poem? Let’s start with what poetry is.

What Poetry Is

It’s important to know what poetry is—and isn’t—before we discuss how to write a poem. The following quote defines poetry nicely:

“Poetry is language at its most distilled and most powerful.”

—Former US Poet Laureate Rita Dove

Poetry Conveys Feeling

People sometimes imagine poetry as stuffy, abstract, and difficult to understand. Some poetry may be this way, but in reality poetry isn’t about being obscure or confusing. Poetry is a lyrical, emotive method of self-expression, using the elements of poetry to highlight feelings and ideas.

A poem should make the reader feel something.

In other words, a poem should make the reader feel something—not by telling them what to feel, but by evoking feeling directly.

Here’s a contemporary poem that, despite its simplicity (or perhaps because of its simplicity), conveys heartfelt emotion.

Poem

by Langston HughesI loved my friend.

He went away from me.

There’s nothing more to say.

The poem ends,

Soft as it began—

I loved my friend.

Poetry is Language at its Richest and Most Condensed

Unlike longer prose writing (such as a short story, memoir, or novel), poetry needs to impact the reader in the richest and most condensed way possible. Here’s a famous quote that enforces that distinction:

“Prose: words in their best order; poetry: the best words in the best order.”

—Samuel Taylor Coleridge

So poetry isn’t the place to be filling in long backstories or doing leisurely scene-setting. In poetry, every single word carries maximum impact.

Check Out Our Poetry Writing Courses!

(Live Workshop) Poetry as Sacred Attention

with Nadia Colburn

June 6th, 2023

Poetry asks us to slow down, listen, and pay attention. In this meditative workshop, we’ll open ourselves to the beauty and mystery of poetry.

Poetry Uses Unique Elements

Poetry is not like other kinds of writing: it has its own unique forms, tools, and principles. Together, these elements of poetry help it to powerfully impact the reader in only a few words.

The elements of poetry help it to powerfully impact the reader in only a few words.

Most poetry is written in verse, rather than prose. This means that it uses line breaks, alongside rhythm or meter, to convey something to the reader. Rather than letting the text break at the end of the page (as prose does), verse emphasizes language through line breaks.

Poetry further accentuates its use of language through rhyme and meter. Poetry has a heightened emphasis on the musicality of language itself: its sounds and rhythms, and the feelings they carry.

These devices—rhyme, meter, and line breaks—are just a few of the essential elements of poetry, which we’ll explore in more depth now.

Understanding the Elements of Poetry

As we explore how to write a poem step by step, these three major literary elements of poetry should sit in the back of your mind:

- Rhythm (Sound, Rhyme, and Meter)

- Form

- Literary Devices

1. Elements of Poetry: Rhythm

“Rhythm” refers to the lyrical, sonic qualities of the poem. How does the poem move and breathe; how does it feel on the tongue?

Traditionally, poets relied on rhyme and meter to accomplish a rhythmically sound poem. Free verse poems—which are poems that don’t require a specific length, rhyme scheme, or meter—only became popular in the West in the 20th century, so while rhyme and meter aren’t requirements of modern poetry, they are required of certain poetry forms.

Sound

Poetry is capable of evoking certain emotions based solely on the sounds it uses. Words can sound sinister, percussive, fluid, cheerful, dour, or any other noise/emotion in the complex tapestry of human feeling.

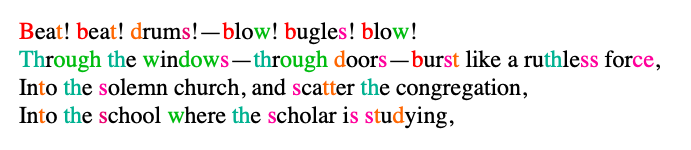

Take, for example, this excerpt from the poem “Beat! Beat! Drums!” by Walt Whitman:

Red — “b” sounds

Blue — “th” sounds

Green — “w” and “ew” sounds

Purple — “s” sounds

Orange — “d” and “t” sounds

This poem has a lot of percussive, disruptive sounds that reinforce the beating of the drums. The “b,” “d,” “w,” and “t” sounds resemble these drum beats, while the “th” and “s” sounds are sneakier, penetrating a deeper part of the ear. The cacophony of this excerpt might not sound “lyrical,” but it does manage to command your attention, much like drums beating through a city might sound.

To learn more about consonance and assonance, euphony and cacophony, and the other uses of sound, take a look at our article “12 Literary Devices in Poetry.”

Rhyme

It would be a crime if you weren’t primed on the ins and outs of rhymes. “Rhyme” refers to words that have similar pronunciations, like this set of words: sound, hound, browned, pound, found, around.

Many poets assume that their poetry has to rhyme, and it’s true that some poems require a complex rhyme scheme. However, rhyme isn’t nearly as important to poetry as it used to be. Most traditional poetry forms—sonnets, villanelles, rimes royal, etc.—rely on rhyme, but contemporary poetry has largely strayed from the strict rhyme schemes of yesterday.

There are three types of rhymes:

- Homophony: Homophones are words that are spelled differently but sound the same, like “tail” and “tale.” Homophones often lead to commonly misspelled words.

- Perfect Rhyme: Perfect rhymes are word pairs that are identical in sound except for one minor difference. Examples include “slant and pant,” “great and fate,” and “shower and power.”

- Slant Rhyme: Slant rhymes are word pairs that use the same sounds, but their final vowels have different pronunciations. For example, “abut” and “about” are nearly-identical in sound, but are pronounced differently enough that they don’t completely rhyme. This is also known as an oblique rhyme or imperfect rhyme.

Meter

Meter refers to the stress patterns of words. Certain poetry forms require that the words in the poem follow a certain stress pattern, meaning some syllables are stressed and others are unstressed.

What is “stressed” and “unstressed”? A stressed syllable is the sound that you emphasize in a word. The bolded syllables in the following words are stressed, and the unbolded syllables are unstressed:

- Un•stressed

- Plat•i•tud•i•nous

- De•act•i•vate

- Con•sti•tu•tion•al

The pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables is important to traditional poetry forms. This chart, copied from our article on form in poetry, summarizes the different stress patterns of poetry.

| Meter | Pattern | Example |

| Iamb | Unstressed–stressed | Exist |

| Trochee | Stressed–unstressed | Sample |

| Pyrrh | Equally unstressed | Pyrrhic |

| Spondee | Equally stressed | Cupcake |

| Dactyl | Stressed–unstressed–unstressed | Freshener |

| Anapest | Unstressed–unstressed–stressed | Comprehend |

| Amphibrach (rare) | Unstressed–stressed–unstressed | Flamingo |

2. Elements of Poetry: Form

“Form” refers to the structure of the poem. Is the poem a sonnet, a villanelle, a free verse piece, a slam poem, a contrapuntal, a ghazal, a blackout poem, or something new and experimental?

Form also refers to the line breaks and stanza breaks in a poem. Unlike prose, where the end of the page decides the line breaks, poets have control over when one line ends and a new one begins. The words that begin and end each line will emphasize the sounds, images, and ideas that are important to the poet.

To learn more about rhyme, meter, and poetry forms, read our full article on the topic:

3. Elements of Poetry: Literary Devices

“Poetry: the best words in the best order.” — Samuel Taylor Coleridge

How does poetry express complex ideas in concise, lyrical language? Literary devices—like metaphor, symbolism, juxtaposition, irony, and hyperbole—help make poetry possible. Learn how to write and master these devices here:

112 Common Literary Devices: Definitions, Examples, and Exercises

How to Write a Poem, in 7 Steps

To condense the elements of poetry into an actual poem, we’re going to follow a seven-step approach. However, it’s important to know that every poet’s process is different. While the steps presented here are a logical path to get from idea to finished poem, they’re not the only tried-and-true method of poetry writing. Poets can—and should!—modify these steps and generate their own writing process.

Nonetheless, if you’re new to writing poetry or want to explore a different writing process, try your hand at our approach. Here’s how to write a poem step by step!

1. Devise a Topic

The easiest way to start writing a poem is to begin with a topic.

However, devising a topic is often the hardest part. What should your poem be about? And where can you find ideas?

Here are a few places to search for inspiration:

- Other Works of Literature: Poetry doesn’t exist in a vacuum—it’s part of a larger literary tapestry, and can absolutely be influenced by other works. For example, read “The Golden Shovel” by Terrance Hayes, a poem that was inspired by Gwendolyn Brooks’ “We Real Cool.”

- Real-World Events: Poetry, especially contemporary poetry, has the power to convey new and transformative ideas about the world. Take the poem “A Cigarette” by Ilya Kaminsky, which finds community in a warzone like the eye of a hurricane.

- Your Life: What would poetry be if not a form of memoir? Many contemporary poets have documented their lives in verse. Take Sylvia Plath’s poem “Full Fathom Five”—a daring poem for its time, as few writers so boldly criticized their family as Plath did.

- The Everyday and Mundane: Poetry isn’t just about big, earth-shattering events: much can be said about mundane events, too. Take “Ode to Shea Butter” by Angel Nafis, a poem that celebrates the beautiful “everydayness” of moisturizing.

- Nature: The Earth has always been a source of inspiration for poets, both today and in antiquity. Take “Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver, which finds meaning in nature’s quiet rituals.

- Writing Exercises: Prompts and exercises can help spark your creativity, even if the poem you write has nothing to do with the prompt! Here’s 24 writing exercises to get you started.

2. Journal

At this point, you’ve got a topic for your poem. Maybe it’s a topic you’re passionate about, and the words pour from your pen and align themselves into a perfect sonnet! It’s not impossible—most poets have a couple of poems that seemed to write themselves.

However, it’s far more likely you’re searching for the words to talk about this topic. This is where journaling comes in.

Sit in front of a blank piece of paper, with nothing but the topic written on the top. Set a timer for 15-30 minutes and put down all of your thoughts related to the topic. Don’t stop and think for too long, and try not to obsess over finding the right words: what matters here is emotion, the way your subconscious grapples with the topic.

At the end of this journaling session, go back through everything you wrote, and highlight whatever seems important to you: well-written phrases, poignant moments of emotion, even specific words that you want to use in your poem.

Journaling is a low-risk way of exploring your topic without feeling pressured to make it sound poetic. “Sounding poetic” will only leave you with empty language: your journal allows you to speak from the heart. Everything you need for your poem is already inside of you, the journaling process just helps bring it out!

3. Think About Form

As one of the elements of poetry, form plays a crucial role in how the poem is both written and read. Have you ever wanted to write a sestina? How about a contrapuntal, or a double cinquain, or a series of tanka? Your poem can take a multitude of forms, including the beautifully unstructured free verse form; while form can be decided in the editing process, it doesn’t hurt to think about it now.

4. Write the First Line

After a productive journaling session, you’ll be much more acquainted with the state of your heart. You might have a line in your journal that you really want to begin with, or you might want to start fresh and refer back to your journal when you need to! Either way, it’s time to begin.

What should the first line of your poem be? There’s no strict rule here—you don’t have to start your poem with a certain image or literary device. However, here’s a few ways that poets often begin their work:

- Set the Scene: Poetry can tell stories just like prose does. Anne Carson does just this in her poem “Lines,” situating the scene in a conversation with the speaker’s mother.

- Start at the Conflict: Right away, tell the reader where it hurts most. Margaret Atwood does this in “Ghost Cat,” a poem about aging.

- Start With a Contradiction: Juxtaposition and contrast are two powerful tools in the poet’s toolkit. Joan Larkin’s poem “Want” begins and ends with these devices. Carlos Gimenez Smith also begins his poem “Entanglement” with a juxtaposition.

- Start With Your Title: Some poets will use the title as their first line, like Ron Padgett’s poem “Ladies and Gentlemen in Outer Space.”

There are many other ways to begin poems, so play around with different literary devices, and when you’re stuck, turn to other poetry for inspiration.

5. Develop Ideas and Devices

You might not know where your poem is going until you finish writing it. In the meantime, stick to your literary devices. Avoid using too many abstract nouns, develop striking images, use metaphors and similes to strike interesting comparisons, and above all, speak from the heart.

6. Write the Closing Line

Some poems end “full circle,” meaning that the images the poet used in the beginning are reintroduced at the end. Gwendolyn Brooks does this in her poem “my dreams, my work, must wait till after hell.”

Yet, many poets don’t realize what their poems are about until they write the ending line. Poetry is a search for truth, especially the hard truths that aren’t easily explained in casual speech. Your poem, too, might not be finished until it comes across a necessary truth, so write until you strike the heart of what you feel, and the poem will come to its own conclusion.

7. Edit, Edit, Edit!

Do you have a working first draft of your poem? Congratulations! Getting your feelings onto the page is a feat in itself.

Yet, no guide on how to write a poem is complete without a note on editing. If you plan on sharing or publishing your work, or if you simply want to edit your poem to near-perfection, keep these tips in mind.

- Adjectives and Adverbs: Use these parts of speech sparingly. Most imagery shouldn’t rely on adjectives and adverbs, because the image should be striking and vivid on its own, without too much help from excess language.

- Concrete Line Breaks: Line breaks help emphasize important words, making certain images and ideas clearer to the reader. As a general rule, most of your lines should start and end with concrete words—nouns and verbs especially.

- Stanza Breaks: Stanzas are like paragraphs to poetry. A stanza can develop a new idea, contrast an existing idea, or signal a transition in the poem’s tone. Make sure each stanza clearly stands for something as a unit of the poem.

- Mixed Metaphors: A mixed metaphor is when two metaphors occupy the same idea, making the poem unnecessarily difficult to understand. Here’s an example of a mixed metaphor: “a watched clock never boils.” The meaning can be discerned, but the image remains unclear. Be wary of mixed metaphors—though some poets (like Shakespeare) make them work, they’re tricky and often disruptive.

- Abstractions: Above all, avoid using excessively abstract language. It’s fine to use the word “love” 2 or 3 times in a poem, but don’t use it twice in every stanza. Let the imagery in your poem express your feelings and ideas, and only use abstractions as brief connective tissue in otherwise-concrete writing.

Lastly, don’t feel pressured to “do something” with your poem. Not all poems need to be shared and edited. Poetry doesn’t have to be “good,” either—it can simply be a statement of emotions by the poet, for the poet. Publishing is an admirable goal, but also, give yourself permission to write bad poems, unedited poems, abstract poems, and poems with an audience of one. Write for yourself—editing is for the other readers.

How to Write a Poem: Different Approaches and Philosophies

Poetry is the oldest literary form, pre-dating prose, theater, and the written word itself. As such, there are many different schools of thought when it comes to writing poetry. You might be wondering how to write a poem through different methods and approaches: here’s four philosophies to get you started.

How to Write a Poem: Poetry as Emotion

If you asked a Romantic Poet “what is poetry?”, they would tell you that poetry is the spontaneous emotion of the soul.

The Romantic Era viewed poetry as an extension of human emotion—a way of perceiving the world through unbridled creativity, centered around the human soul. While many Romantic poets used traditional forms in their poetry, the Romantics weren’t afraid to break from tradition, either.

To write like a Romantic, feel—and feel intensely. The words will follow the emotions, as long as a blank page sits in front of you.

How to Write a Poem: Poetry as Stream of Consciousness

If you asked a Modernist poet, “What is poetry?” they would tell you that poetry is the search for complex truths.

Modernist Poets were keen on the use of poetry as a window into the mind. A common technique of the time was “Stream of Consciousness,” which is unfiltered writing that flows directly from the poet’s inner dialogue. By tapping into one’s subconscious, the poet might uncover deeper truths and emotions they were initially unaware of.

Depending on who you are as a writer, Stream of Consciousness can be tricky to master, but this guide covers the basics of how to write using this technique.

How to Write a Poem: Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a practice of documenting the mind, rather than trying to control or edit what it produces. This practice was popularized by the Beat Poets, who in turn were inspired by Eastern philosophies and Buddhist teachings. If you asked a Beat Poet “what is poetry?”, they would tell you that poetry is the human consciousness, unadulterated.

To learn more about the art of leaving your mind alone, take a look at our guide on Mindfulness, from instructor Marc Olmsted.

How to Write a Poem: Poem as Camera Lens

Many contemporary poets use poetry as a camera lens, documenting global events and commenting on both politics and injustice. If you find yourself itching to write poetry about the modern day, press your thumb against the pulse of the world and write what you feel.

Additionally, check out these two essays by Electric Literature on the politics of poetry:

- What Can Poetry Do That Politics Can’t?

- Why All Poems Are Political (TL;DR: Poetry is an urgent expression of freedom).

Okay, I Know How to Write a Good Poem. What Next?

Poetry, like all art forms, takes practice and dedication. You might write a poem you enjoy now, and think it’s awfully written 3 years from now; you might also write some of your best work after reading this guide. Poetry is fickle, but the pen lasts forever, so write poems as long as you can!

Once you understand how to write a poem, and after you’ve drafted some pieces that you’re proud of and ready to share, here are some next steps you can take.

Publish in Literary Journals

Want to see your name in print? These literary journals house some of the best poetry being published today.

Assemble and Publish a Manuscript

A poem can tell a story. So can a collection of poems. If you’re interested in publishing a poetry book, learn how to compose and format one here:

Join a Writing Community

writers.com is an online community of writers, and we’d love it if you shared your poetry with us! Join us on Facebook and check out our upcoming poetry courses.

Poetry doesn’t exist in a vacuum, it exists to educate and uplift society. The world is waiting for your voice, so find a group and share your work!

Learning how to write a poem is debatably one of the hardest forms of creative writing to master—there are so many “rules”, but at the same time, no rules at all. It is the ultimate form of individual expression, yet there are creative writing prompts that fit into genres.

Confusing, right?

Despite the challenge, writing poetry is a very fulfilling creative venue, and we have exactly what you’re looking for to learn how to nail this art form.

Because poetry is so specific to the artist, knowing how to write a poem in your own way can be tricky.

Here’s how to write a poem using our fundamentals of poetry:

- Understand the benefits of writing poetry

- Decide which type of poetry to write

- Have proper poem structure

- Include sharp imagery

- Focus on sound in poetry

- Define the poem’s meaning

- Have a goal

- Avoid clichés in your poems

- Opt for minimalistic poems

- Refine your poem to perfection

If you’re ready to learn what it takes to write (and then potentially publish a book of) good poetry, we’ve got the help you need.

Benefits of Learning How to Write a Poem

Even if you aren’t looking to become a full-time poet, or even attempt to publish a single poem, writing poetry can be beneficial in several ways.

- It strengthens your skills in writing solid imagery. Poetry is a very image-based form of writing, so practicing poetry will improve your imagery in other forms as well.

- Poetry is concise and impactful—it uses strong language, and no more words than are necessary. If you have an understanding of how to write a poem, your prose when writing a novel will become crisper and stronger.

- Poetry helps you to connect with emotions in a tangible way. Other forms of writing have the plot to hide behind—with poetry, all you’ve got are emotions. (Unless it’s a narrative poem, of course.)

- You can become a professional poet and earn a living writing. Even if you just want to enjoy poetry for the above reasons, you can also make a full-time income this way. A great way to get started is to apply for a poetry scholarship in addition to the rest of the tips here.

Types of Poetry

Not all types of poetry are the same, and that means learning how to write a poem involves being familiar with the different types.

Here are the different types of poetry:

- Narrative – this kind of poem relies on a story. It tells an event and there are often a few extra elements, such as characters, a plot, and a strong narration.

- Lyrical – a lyric poem is similar to a song, and it tends to describe a specific feeling, scene, or state of mind.

You may be familiar with these different types of poetry. For example, a lyrical poem is actually a song. Listening to your favorite radio station is just like hearing a collection of your favorite poems being read to you with some background music.

A narrative poem is, as mentioned above, more like a story told in poetic prose.

Here’s a small example of a part of Edgar Allen Poe’s famous poem, The Raven:

8 Fundamentals for How to Write a Poem

Poetry can often be subjective. Not every poem will speak to every person.

That being said, there are different attributes that you should learn if you want to know how to write poetry well regardless.

#1 – Structure of writing a poem

The structure of a poem can refer to many different things, but we’re going to discuss some different forms of poetry, how to use punctuation, and last words.

Form of a Poem

The form of your poem is the physical structure. It can have requirements for rhyme, line length, number of lines/stanzas, etc.

Here are different types of poetry forms:

- Sonnet – A short, rhyming poem of 14 lines

- Haiku – A poem of 3 lines where the first is 5 syllables, the middle is 7 syllables, and the last is 5.

- Acrostic – A poem where the first letter of each line spells a word that fits with the theme of the poem or exposes a deeper meaning.

- Limerick – This is a 5-live witty poem with the first, second, and fifth lines rhyme as do the other two with each other.

- Epic – This type of poetry is a lengthy narrative poem celebrating adventures or accomplishments of heroes.

- Couplet – This can be a part of a poem or stand alone as a poem of two lines that rhyme.

- Free verse – This type of poem doesn’t follow any rules and is free written poetry by the author.

The majority of poets, specifically less experienced ones, write what’s called free verse, which is a poem without a form, or with a form the poet has made up for that specific piece.

A poet may decide to have a certain rhyme scheme or might make their poems syllabic.

With a free verse poem, you can set up any theme or pattern you wish, or have none at all.

The great thing about poetry is that you can even start with a specific poem form, and then choose to alter it in order to make it unique and your own.

Poetry Punctuation

Writing a poem is difficult because you never know what the appropriate punctuation is, because it can be different from punctuation when writing a book.

There are essentially three ways to punctuate your poetry:

- Grammatically – this means you use punctuation properly for every grammar rule; if you removed the lines and stanzas, it would work as a grammatically correct paragraph, and this even includes writing dialogue in your poem.

- Stylistically – this means you use punctuation to serve the way you would like the poem to be read. A comma indicates a short pause, a period indicates a longer pause, a dash indicates a pause with a connection of thoughts. Using no punctuation at all would lend to a rushed feeling, which you may want. Your punctuation choices will depend on your goals when writing a poem.

- A combination. Maybe you want to mostly follow punctuation rules, but you have a certain line you want read a certain way. It’s totally fine to deviate from standard rules if it serves a purpose—you just need to do whatever you’re doing intentionally. Know the rules before you can break them.

“In poetry, punctuation serves as the conductor. It sets the beat of a line or a stanza, telling you where to pause for breath. Conversely, enjambment—running lines of poetry together by not ending them with punctuation—can be extremely powerful, when used correctly. It keeps the line flowing without a pause or a full stop.” – Krystal Blaze Dean

Last words of a poem

The last word of a line, the last word of your poem, and the last line of your poem are very important—these are the bits that echo in your reader’s head and have the most emphasis.

Ending with punctuation (dash, period, comma) versus ending without punctuation will give you a dramatically different read, so consider the effect you’d like to have.

Tip for last words: read the poem out loud a few times to see where you’d like the inflection and emphasis to fall.

#2 – Imagery

Imagery is a literary device that’s a tangible description that appeals to one of the five senses.

The more imagery in a poem, the more the reader can connect with it.

Tip for imagery: focus on details. Instead of going for the obvious description, really put yourself in that moment or feeling—what details are the most impactful and real?

Here are some examples of imagery:

- Pungent fumes lifted from the floor beneath her.

- Burning light painted the insides of his eyelids red.

- Hair from her ponytail bit at her face, swept into a frenzy by the furious winds.

- Crackling popped in rhythm to the dancing flames.

#3 – Sound

While imagery is for the mind, sound is for the ear. How do your words and lines sound when read out loud?

The most basic sound style is a rhyme, however, you should never force a rhyme!

If you try for exact rhymes on every line, it becomes “sing songy,” and this is a big, red mark of an amateur. Sticking to a strict rhyme scheme can severely limit your word choice and creativity.

Instead of going for exact end rhymes, here are some options to achieve that appealing auditory effect of rhyming when writing poems:

- Assonance – the repetition of a vowel sound in non-rhyming, stressed syllables. Assonance gives you the fun sound effect of a rhyme without sounding campy. An example of assonance is: “Hear the mellow wedding bells” by Edgar Allen Poe.

- Alliteration – the repetition of a consonant at the beginning of words. Specifically hard consonant sounds like T, ST, and CH have a hard, staccato effect that a lot of poets like to use for alliteration.

- Internal rhymes – words inside of lines rhyme, rather than the end words. Like assonance, you get the effect of a rhyme without sound like a Dr. Seuss ripoff.

Tip for sound in poetry: Focus on beautiful, crisp imagery to carry your poem, rather than strictly relying on the sound and structure of it.

#4 – Meaning

Structure, imagery, and sound work together to make up the technical excellence of a poem. But if your words are empty of a deeper meaning, what’s the point in writing a poem at all?

“Poetry is a form of storytelling. The key to writing is making the audience feel. Give them something to remember and hold onto.” – Brookes Washington

Many new writers latch onto clichés and tired topics (peep that alliteration) for their poems, because they think that’s what they’re supposed to do.

But emulating something someone else has done, or some idea of what you should think a poem should be about, isn’t going to give you a genuine, emotional piece that other people can connect to.

So write the poem that only you can write.

Tips for how to write a poem with meaning:

- Brainstorm poetry topics by looking at your own experiences. What do you know? When is a time you felt very deeply about something? Can you put that feeling into words? Can you make that feeling an image other people can see through your words? That is the poem you write.

- You don’t need some grand, dramatic emotion to write about—think about the ordinary things that make us all human.

“Nothing ever ends poetically. It ends and we turn it into poetry. All that blood was never once beautiful. It was just red.” – Kait Rokowski

#5 – Have a goal

Have a goal with writing a poem—what do you want your audience to feel?

Are you just writing for fun or for yourself? Poetry is often a very personal form of writing, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t think about your audience at the same time.

If you want to publish your poetry eventually, there are a few things to think about in terms of your goals.

What emotion or moral do you want to convey? What are you trying to express?

These are important questions to answer in order to write an impactful and memorable poem.

#6 – Avoid cliche phrases when writing poetry

There are many clichés you want to avoid when writing poetry.

Nothing really marks an amateur poet like clichés (and forced rhymes, like we mentioned before).

Despite the temptation, avoid cliché phrases. Go line by line and make your language as crisp and original as you can.

If there are pieces in your poem that seem like you’ve read or heard them before, try to reword it in order to make it more original.

#7 – Opt for minimalism

Err on the side of minimalism. Once you have a draft, cut it back to the bare, raw necessaries.

Every word should be heavy with emotion and meaning, and every word should be absolutely essential.

If your poem seems long-winded to you, imagine what that would be like for your reader. Be ready to edit your poem to get it down to its best form.

“Poetry is just word math. Every piece has mean something, and there can’t be any extraneous bits otherwise it gets confusing. It just becomes a puzzle made out of all the words that make you feel something.” – Abigail Giroir

#8 – Refine your poem

The real magic of poetry happens in the revising and refining.

Revise the ever-living heck out of it. To paraphrase an old professor of mine: Don’t be afraid to sit with it. For weeks, months, years—as long as the poem needs.

It’s great to have writing goals and timelines, but don’t rush a poem before you know it’s ready.

Avoid abstractions. An abstraction is a word that can only refer to a concept or feeling—it’s not a concrete, tangible thing. Some examples of this are liberty, love, bondage, aggression.

Abstractions make every person picture something different, so they are weak words, and they will weaken your poem.

Instead of using an abstraction, think of what imagery you can use to convey that emotion or concept. Liberty can become chains breaking or birds flying. Love can be bringing your spouse coffee in bed, petting a dog, cleaning a gravestone.

Think of the best images to convey your idea of that abstraction, so every reader can be on the same page with you.

Don’t pigeonhole yourself into a form that will stifle your creativity, utilize imagery and sound, have a meaning and a purpose for every poem, and revise until your fingers bleed.

Ready to Publish YOUR Book of Poems?

Grab your copy of Published. today and publish your first (or eighth) collection of poems!

October 12, 2020October 11, 2020 Jason A. Muckley

I don’t write for other people. I write for me.

My words are my own.

I own them. I share them. I keep them.

My words are my gift.

I am a writer. I am a poet.

The one who reads my words does not define what I write.

My words are.

I am my words.

© 2020 Jason A. Muckley

Advertisement

7 comments

-

Really, straight forward and blunt. Love it

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reply

-

Haha! Thanks

LikeLike

Reply

-

-

Reblogged this on The Reluctant Poet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reply

-

Amazing…. Beautifully put. ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reply

-

Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reply

-

-

Very cool affirmations here. Brief and to the point!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reply

-

Thanks Lia!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reply

-

Leave a Reply

Enter your comment here…

Fill in your details below or click an icon to log in:

Email (required) (Address never made public)

Name (required)

Website

You are commenting using your WordPress.com account.

( Log Out /

Change )

You are commenting using your Twitter account.

( Log Out /

Change )

You are commenting using your Facebook account.

( Log Out /

Change )

Cancel

Connecting to %s

Notify me of new comments via email.

Notify me of new posts via email.