This article is about the unit of speech and writing. For the computer software, see Microsoft Word. For other uses, see Word (disambiguation).

Codex Claromontanus in Latin. The practice of separating words with spaces was not universal when this manuscript was written.

A word is a basic element of language that carries an objective or practical meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible.[1] Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial.[2] Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context; these do not converge on a single definition.[3]: 13:618 Some specific definitions of the term «word» are employed to convey its different meanings at different levels of description, for example based on phonological, grammatical or orthographic basis. Others suggest that the concept is simply a convention used in everyday situations.[4]: 6

The concept of «word» is distinguished from that of a morpheme, which is the smallest unit of language that has a meaning, even if it cannot stand on its own.[1] Words are made out of at least one morpheme. Morphemes can also be joined to create other words in a process of morphological derivation.[2]: 768 In English and many other languages, the morphemes that make up a word generally include at least one root (such as «rock», «god», «type», «writ», «can», «not») and possibly some affixes («-s», «un-«, «-ly», «-ness»). Words with more than one root («[type][writ]er», «[cow][boy]s», «[tele][graph]ically») are called compound words. In turn, words are combined to form other elements of language, such as phrases («a red rock», «put up with»), clauses («I threw a rock»), and sentences («I threw a rock, but missed»).

In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a «word» may be learned as part of learning the writing system.[5] This is the case for the English language, and for most languages that are written with alphabets derived from the ancient Latin or Greek alphabets. In English orthography, the letter sequences «rock», «god», «write», «with», «the», and «not» are considered to be single-morpheme words, whereas «rocks», «ungodliness», «typewriter», and «cannot» are words composed of two or more morphemes («rock»+»s», «un»+»god»+»li»+»ness», «type»+»writ»+»er», and «can»+»not»).

Definitions and meanings

Since the beginning of the study of linguistics, numerous attempts at defining what a word is have been made, with many different criteria.[5] However, no satisfying definition has yet been found to apply to all languages and at all levels of linguistic analysis. It is, however, possible to find consistent definitions of «word» at different levels of description.[4]: 6 These include definitions on the phonetic and phonological level, that it is the smallest segment of sound that can be theoretically isolated by word accent and boundary markers; on the orthographic level as a segment indicated by blank spaces in writing or print; on the basis of morphology as the basic element of grammatical paradigms like inflection, different from word-forms; within semantics as the smallest and relatively independent carrier of meaning in a lexicon; and syntactically, as the smallest permutable and substitutable unit of a sentence.[2]: 1285

In some languages, these different types of words coincide and one can analyze, for example, a «phonological word» as essentially the same as «grammatical word». However, in other languages they may correspond to elements of different size.[4]: 1 Much of the difficulty stems from the eurocentric bias, as languages from outside of Europe may not follow the intuitions of European scholars. Some of the criteria for «word» developed can only be applicable to languages of broadly European synthetic structure.[4]: 1-3 Because of this unclear status, some linguists propose avoiding the term «word» altogether, instead focusing on better defined terms such as morphemes.[6]

Dictionaries categorize a language’s lexicon into individually listed forms called lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the writers of that language. This written form of a word constitutes a lexeme.[2]: 670-671 The most appropriate means of measuring the length of a word is by counting its syllables or morphemes.[7] When a word has multiple definitions or multiple senses, it may result in confusion in a debate or discussion.[8]

Phonology

One distinguishable meaning of the term «word» can be defined on phonological grounds. It is a unit larger or equal to a syllable, which can be distinguished based on segmental or prosodic features, or through its interactions with phonological rules. In Walmatjari, an Australian language, roots or suffixes may have only one syllable but a phonologic word must have at least two syllables. A disyllabic verb root may take a zero suffix, e.g. luwa-ø ‘hit!’, but a monosyllabic root must take a suffix, e.g. ya-nta ‘go!’, thus conforming to a segmental pattern of Walmatjari words. In the Pitjantjatjara dialect of the Wati language, another language form Australia, a word-medial syllable can end with a consonant but a word-final syllable must end with a vowel.[4]: 14

In most languages, stress may serve a criterion for a phonological word. In languages with a fixed stress, it is possible to ascertain word boundaries from its location. Although it is impossible to predict word boundaries from stress alone in languages with phonemic stress, there will be just one syllable with primary stress per word, which allows for determining the total number of words in an utterance.[4]: 16

Many phonological rules operate only within a phonological word or specifically across word boundaries. In Hungarian, dental consonants /d/, /t/, /l/ or /n/ assimilate to a following semi-vowel /j/, yielding the corresponding palatal sound, but only within one word. Conversely, external sandhi rules act across word boundaries. The prototypical example of this rule comes from Sanskrit; however, initial consonant mutation in contemporary Celtic languages or the linking r phenomenon in some non-rhotic English dialects can also be used to illustrate word boundaries.[4]: 17

It is often the case that a phonological word does not correspond to our intuitive conception of a word. The Finnish compound word pääkaupunki ‘capital’ is phonologically two words (pää ‘head’ and kaupunki ‘city’) because it does not conform to Finnish patterns of vowel harmony within words. Conversely, a single phonological word may be made up of more than one syntactical elements, such as in the English phrase I’ll come, where I’ll forms one phonological word.[3]: 13:618

Lexemes

A word can be thought of as an item in a speaker’s internal lexicon; this is called a lexeme. Nevertheless, it is considered different from a word used in everyday speech, since it is assumed to also include inflected forms. Therefore, the lexeme teapot refers to the singular teapot as well as the plural, teapots. There is also the question to what extent should inflected or compounded words be included in a lexeme, especially in agglutinative languages. For example, there is little doubt that in Turkish the lexeme for house should include nominative singular ev or plural evler. However, it is not clear if it should also encompass the word evlerinizden ‘from your houses’, formed through regular suffixation. There are also lexemes such as «black and white» or «do-it-yourself», which, although consist of multiple words, still form a single collocation with a set meaning.[3]: 13:618

Grammar

Grammatical words are proposed to consist of a number of grammatical elements which occur together (not in separate places within a clause) in a fixed order and have a set meaning. However, there are exceptions to all of these criteria.[4]: 19

Single grammatical words have a fixed internal structure; when the structure is changed, the meaning of the word also changes. In Dyirbal, which can use many derivational affixes with its nouns, there are the dual suffix -jarran and the suffix -gabun meaning «another». With the noun yibi they can be arranged into yibi-jarran-gabun («another two women») or yibi-gabun-jarran («two other women») but changing the suffix order also changes their meaning. Speakers of a language also usually associate a specific meaning with a word and not a single morpheme. For example, when asked to talk about untruthfulness they rarely focus on the meaning of morphemes such as -th or -ness.[4]: 19-20

Semantics

Leonard Bloomfield introduced the concept of «Minimal Free Forms» in 1928. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves.[9]: 11 This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms as they make no sense by themselves (for example, the and of).[10]: 77 Some semanticists have put forward a theory of so-called semantic primitives or semantic primes, indefinable words representing fundamental concepts that are intuitively meaningful. According to this theory, semantic primes serve as the basis for describing the meaning, without circularity, of other words and their associated conceptual denotations.[11][12]

Features

In the Minimalist school of theoretical syntax, words (also called lexical items in the literature) are construed as «bundles» of linguistic features that are united into a structure with form and meaning.[13]: 36–37 For example, the word «koalas» has semantic features (it denotes real-world objects, koalas), category features (it is a noun), number features (it is plural and must agree with verbs, pronouns, and demonstratives in its domain), phonological features (it is pronounced a certain way), etc.

Orthography

Words made out of letters, divided by spaces

In languages with a literary tradition, the question of what is considered a single word is influenced by orthography. Word separators, typically spaces and punctuation marks are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts, but these are a relatively modern development in the history of writing. In character encoding, word segmentation depends on which characters are defined as word dividers. In English orthography, compound expressions may contain spaces. For example, ice cream, air raid shelter and get up each are generally considered to consist of more than one word (as each of the components are free forms, with the possible exception of get), and so is no one, but the similarly compounded someone and nobody are considered single words.

Sometimes, languages which are close grammatically will consider the same order of words in different ways. For example, reflexive verbs in the French infinitive are separate from their respective particle, e.g. se laver («to wash oneself»), whereas in Portuguese they are hyphenated, e.g. lavar-se, and in Spanish they are joined, e.g. lavarse.[a]

Not all languages delimit words expressly. Mandarin Chinese is a highly analytic language with few inflectional affixes, making it unnecessary to delimit words orthographically. However, there are many multiple-morpheme compounds in Mandarin, as well as a variety of bound morphemes that make it difficult to clearly determine what constitutes a word.[14]: 56 Japanese uses orthographic cues to delimit words, such as switching between kanji (characters borrowed from Chinese writing) and the two kana syllabaries. This is a fairly soft rule, because content words can also be written in hiragana for effect, though if done extensively spaces are typically added to maintain legibility. Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes rather than words.

Word boundaries

The task of defining what constitutes a «word» involves determining where one word ends and another word begins, that is identifying word boundaries. There are several ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:[5]

- Potential pause: A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words, or fail to separate two or more closely linked words (e.g. «to a» in «He went to a house»).

- Indivisibility: A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, I have lived in this village for ten years might become My family and I have lived in this little village for about ten or so years. These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes: in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an«, the verb ankommen is separated.

- Phonetic boundaries: Some languages have particular rules of pronunciation that make it easy to spot where a word boundary should be. For example, in a language that regularly stresses the last syllable of a word, a word boundary is likely to fall after each stressed syllable. Another example can be seen in a language that has vowel harmony (like Turkish):[15]: 9 the vowels within a given word share the same quality, so a word boundary is likely to occur whenever the vowel quality changes. Nevertheless, not all languages have such convenient phonetic rules, and even those that do present the occasional exceptions.

- Orthographic boundaries: Word separators, such as spaces and punctuation marks can be used to distinguish single words. However, this depends on a specific language. East-asian writing systems often do not separate their characters. This is the case with Chinese, Japanese writing, which use logographic characters, as well as Thai and Lao, which are abugidas.

Morphology

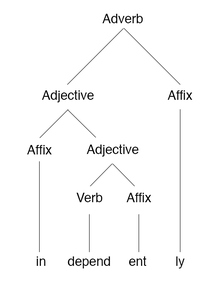

A morphology tree of the English word «independently»

Morphology is the study of word formation and structure. Words may undergo different morphological processes which are traditionally classified into two broad groups: derivation and inflection. Derivation is a process in which a new word is created from existing ones, often with a change of meaning. For example, in English the verb to convert may be modified into the noun a convert through stress shift and into the adjective convertible through affixation. Inflection adds grammatical information to a word, such as indicating case, tense, or gender.[14]: 73

In synthetic languages, a single word stem (for example, love) may inflect to have a number of different forms (for example, loves, loving, and loved). However, for some purposes these are not usually considered to be different words, but rather different forms of the same word. In these languages, words may be considered to be constructed from a number of morphemes.

In Indo-European languages in particular, the morphemes distinguished are:

- The root.

- Optional suffixes.

- A inflectional suffix.

Thus, the Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dhom would be analyzed as consisting of

- *wr̥-, the zero grade of the root *wer-.

- A root-extension *-dh- (diachronically a suffix), resulting in a complex root *wr̥dh-.

- The thematic suffix *-o-.

- The neuter gender nominative or accusative singular suffix *-m.

Philosophy

Philosophers have found words to be objects of fascination since at least the 5th century BC, with the foundation of the philosophy of language. Plato analyzed words in terms of their origins and the sounds making them up, concluding that there was some connection between sound and meaning, though words change a great deal over time. John Locke wrote that the use of words «is to be sensible marks of ideas», though they are chosen «not by any natural connexion that there is between particular articulate sounds and certain ideas, for then there would be but one language amongst all men; but by a voluntary imposition, whereby such a word is made arbitrarily the mark of such an idea».[16] Wittgenstein’s thought transitioned from a word as representation of meaning to «the meaning of a word is its use in the language.»[17]

Classes

Each word belongs to a category, based on shared grammatical properties. Typically, a language’s lexicon may be classified into several such groups of words. The total number of categories as well as their types are not universal and vary among languages. For example, English has a group of words called articles, such as the (the definite article) or a (the indefinite article), which mark definiteness or identifiability. This class is not present in Japanese, which depends on context to indicate this difference. On the other hand, Japanese has a class of words called particles which are used to mark noun phrases according to their grammatical function or thematic relation, which English marks using word order or prosody.[18]: 21–24

It is not clear if any categories other than interjection are universal parts of human language. The basic bipartite division that is ubiquitous in natural languages is that of nouns vs verbs. However, in some Wakashan and Salish languages, all content words may be understood as verbal in nature. In Lushootseed, a Salish language, all words with ‘noun-like’ meanings can be used predicatively, where they function like verb. For example, the word sbiaw can be understood as ‘(is a) coyote’ rather than simply ‘coyote’.[19][3]: 13:631 On the other hand, in Eskimo–Aleut languages all content words can be analyzed as nominal, with agentive nouns serving the role closest to verbs. Finally, in some Austronesian languages it is not clear whether the distinction is applicable and all words can be best described as interjections which can perform the roles of other categories.[3]: 13:631

The current classification of words into classes is based on the work of Dionysius Thrax, who, in the 1st century BC, distinguished eight categories of Ancient Greek words: noun, verb, participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, and conjunction. Later Latin authors, Apollonius Dyscolus and Priscian, applied his framework to their own language; since Latin has no articles, they replaced this class with interjection. Adjectives (‘happy’), quantifiers (‘few’), and numerals (‘eleven’) were not made separate in those classifications due to their morphological similarity to nouns in Latin and Ancient Greek. They were recognized as distinct categories only when scholars started studying later European languages.[3]: 13:629

In Indian grammatical tradition, Pāṇini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of suffixes taken by the word. Some words can be controversial, such as slang in formal contexts; misnomers, due to them not meaning what they would imply; or polysemous words, due to the potential confusion between their various senses.[20]

History

In ancient Greek and Roman grammatical tradition, the word was the basic unit of analysis. Different grammatical forms of a given lexeme were studied; however, there was no attempt to decompose them into morphemes. [21]: 70 This may have been the result of the synthetic nature of these languages, where the internal structure of words may be harder to decode than in analytic languages. There was also no concept of different kinds of words, such as grammatical or phonological – the word was considered a unitary construct.[4]: 269 The word (dictiō) was defined as the minimal unit of an utterance (ōrātiō), the expression of a complete thought.[21]: 70

See also

- Longest words

- Utterance

- Word (computer architecture)

- Word count, the number of words in a document or passage of text

- Wording

- Etymology

Notes

- ^ The convention also depends on the tense or mood—the examples given here are in the infinitive, whereas French imperatives, for example, are hyphenated, e.g. lavez-vous, whereas the Spanish present tense is completely separate, e.g. me lavo.

References

- ^ a b Brown, E. K. (2013). The Cambridge dictionary of linguistics. J. E. Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-521-76675-3. OCLC 801681536.

- ^ a b c d Bussmann, Hadumod (1998). Routledge dictionary of language and linguistics. Gregory Trauth, Kerstin Kazzazi. London: Routledge. p. 1285. ISBN 0-415-02225-8. OCLC 41252822.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Keith (2005). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics: V1-14. Keith Brown (2nd ed.). ISBN 1-322-06910-7. OCLC 1097103078.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Word: a cross-linguistic typology. Robert M. W. Dixon, A. Y. Aikhenvald. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-511-06149-8. OCLC 57123416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Haspelmath, Martin (2011). «The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax». Folia Linguistica. 45 (1). doi:10.1515/flin.2011.002. ISSN 0165-4004. S2CID 62789916.

- ^ Harris, Zellig S. (1946). «From morpheme to utterance». Language. 22 (3): 161–183. doi:10.2307/410205. JSTOR 410205.

- ^ The Oxford handbook of the word. John R. Taylor (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-175669-6. OCLC 945582776.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Chodorow, Martin S.; Byrd, Roy J.; Heidorn, George E. (1985). «Extracting semantic hierarchies from a large on-line dictionary». Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics. Chicago, Illinois: Association for Computational Linguistics: 299–304. doi:10.3115/981210.981247. S2CID 657749.

- ^ Katamba, Francis (2005). English words: structure, history, usage (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29892-X. OCLC 54001244.

- ^ Fleming, Michael; Hardman, Frank; Stevens, David; Williamson, John (2003-09-02). Meeting the Standards in Secondary English (1st ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203165553. ISBN 978-1-134-56851-2.

- ^ Wierzbicka, Anna (1996). Semantics : primes and universals. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870002-4. OCLC 33012927.

- ^ «The search for the shared semantic core of all languages.». Meaning and universal grammar. Volume II: theory and empirical findings. Cliff Goddard, Anna Wierzbicka. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co. 2002. ISBN 1-58811-264-0. OCLC 752499720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: a minimalist approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924370-0. OCLC 50768042.

- ^ a b An introduction to language and linguistics. Ralph W. Fasold, Jeff Connor-Linton. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-84768-1. OCLC 62532880.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Bauer, Laurie (1983). English word-formation. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]. ISBN 0-521-24167-7. OCLC 8728300.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). «Chapter II: Of the Signification of Words». An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Vol. III (1st ed.). London: Thomas Basset.

- ^ Biletzki, Anar; Matar, Anat (2021). Ludwig Wittgenstein. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Linguistics: an introduction to language and communication. Adrian Akmajian (6th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-262-01375-8. OCLC 424454992.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Beck, David (2013-08-29), Rijkhoff, Jan; van Lier, Eva (eds.), «Unidirectional flexibility and the noun–verb distinction in Lushootseed», Flexible Word Classes, Oxford University Press, pp. 185–220, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668441.003.0007, ISBN 978-0-19-966844-1, retrieved 2022-08-25

- ^ De Soto, Clinton B.; Hamilton, Margaret M.; Taylor, Ralph B. (December 1985). «Words, People, and Implicit Personality Theory». Social Cognition. 3 (4): 369–382. doi:10.1521/soco.1985.3.4.369. ISSN 0278-016X.

- ^ a b Robins, R. H. (1997). A short history of linguistics (4th ed.). London. ISBN 0-582-24994-5. OCLC 35178602.

Bibliography

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Words.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Word.

Look up word in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Barton, David (1994). Literacy: an introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. p. 96. ISBN 0-631-19089-9. OCLC 28722223.

- The encyclopedia of language & linguistics. E. K. Brown, Anne Anderson (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 978-0-08-044854-1. OCLC 771916896.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Crystal, David (1995). The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40179-8. OCLC 31518847.

- Plag, Ingo (2003). Word-formation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-07843-9. OCLC 57545191.

- The Oxford English Dictionary. J. A. Simpson, E. S. C. Weiner, Oxford University Press (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1989. ISBN 0-19-861186-2. OCLC 17648714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

Word: The Definition & Criteria

In traditional grammar, word is the basic unit of language. Words can be classified according to their action and meaning, but it is challenging to define.

A word refers to a speech sound, or a mixture of two or more speech sounds in both written and verbal form of language. A word works as a symbol to represent/refer to something/someone in language to communicate a specific meaning.

Example : ‘love’, ‘cricket’, ‘sky’ etc.

«[A word is the] smallest unit of grammar that can stand alone as a complete utterance, separated by spaces in written language and potentially by pauses in speech.» (David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press, 2003)

Morphology, a branch of linguistics, studies the formation of words. The branch of linguistics that studies the meaning of words is called lexical semantics.

See More:

Online English Grammar Course

Free Online Exercise of English Grammar

There are several criteria for a speech sound, or a combination of some speech sounds to be called a word.

- There must be a potential pause in speech and a space in written form between two words.

For instance, suppose ‘ball’ and ‘bat’ are two different words. So, if we use them in a sentence, we must have a potential pause after pronouncing each of them. It cannot be like “Idonotplaywithbatball.” If we take pause, these sounds can be regarded as seven distinct words which are ‘I,’ ‘do,’ ‘not,’ ‘play,’ ‘with,’ ‘bat,’ and ‘ball.’ - Every word must contain at least one root. If you break this root, it cannot be a word anymore.

For example, the word ‘unfaithful’ has a root ‘faith.’ If we break ‘faith’ into ‘fa’ and ‘ith,’ these sounds will not be regarded as words. - Every word must have a meaning.

For example, the sound ‘lakkanah’ has no meaning in the English language. So, it cannot be an English word.

The

outline of the problem discussed

1.

The main types of words in English and their morphological structure.

2.

Affixation (or derivation).

3.

Compounding.

4.

Conversion.

5.

Abbreviation (shortening).

Word-formation

is the process of creating new words from the material

available

in the language.

Before

turning to various processes of word-building in English, it would be

useful

to analyze the main types of English words and their morphological

structure.

If

viewed structurally, words appear to be divisible into smaller units

which are

called

morphemes.

Morphemes

do not occur as free forms but only as constituents of

words.

Yet they possess meanings of their own.

All

morphemes are subdivided into two large classes: roots

(or

radicals)

and

affixes.

The

latter, in their turn, fall into prefixes

which

precede the root in the

structure

of the word (as in re-real,

mis-pronounce, un-well) and

suffixes

which

follow

the root (as in teach-er,

cur-able, dict-ate).

Words

which consist of a root and an affix (or several affixes) are called

derived

words or

derivatives

and

are produced by the process of word-building

known

as affixation

(or

derivation).

Derived

words are extremely numerous in the English vocabulary.

Successfully

competing with this structural type is the so-called root

word which

has

only

a root morpheme in its structure. This type is widely represented by

a great

number

of words belonging to the original English stock or to earlier

borrowings

(house,

room, book, work, port, street, table, etc.), and,

in Modern English, has been

greatly

enlarged by the type of word-building called conversion

(e.g.

to

hand, v.

formed

from the noun hand;

to can, v.

from can,

n.;

to

pale,

v. from pale,

adj.;

a

find,

n.

from to

find, v.;

etc.).

Another

wide-spread word-structure is a compound

word consisting

of two or

more

stems (e.g. dining-room,

bluebell, mother-in-law, good-for-nothing).

Words of

this

structural type are produced by the word-building process called

composition.

The

somewhat odd-looking words like flu,

lab, M.P., V-day, H-bomb are

called

curtailed

words and

are produced by the way of word-building called shortening

(abbreviation).

The

four types (root words, derived words, compounds, shortenings)

represent

the

main structural types of Modern English words, and affixation

(derivation),

conversion,

composition and shortening (abbreviation) — the most productive ways

of

word-building.

83

The

process of affixation

consists

in coining a new word by adding an affix or

several

affixes to some root morpheme. The role of the affix in this

procedure is very

important

and therefore it is necessary to consider certain facts about the

main types

of

affixes.

From

the etymological point of view affixes are classified into the same

two

large

groups as words: native and borrowed.

Some

Native Suffixes

-er

worker,

miner,

teacher,

painter,

etc.

-ness

coldness,

loneliness,

loveliness,

etc.

-ing

feeling,

meaning,

singing,

reading,

etc.

-dom

freedom,

wisdom,

kingdom,

etc.

-hood

childhood,

manhood,

motherhood,

etc.

-ship

friendship,

companionship,

mastership,

etc.

Noun-forming

-th

length,

breadth,

health,

truth,

etc.

-ful

careful,

joyful,

wonderful,

sinful,

skilful,

etc.

-less

careless,

sleepless,

cloudless,

senseless,

etc.

-y

cozy,

tidy,

merry,

snowy,

showy,

etc.

-ish

English,

Spanish,

reddish,

childish,

etc.

-ly

lonely,

lovely,

ugly,

likely,

lordly,

etc.

-en

wooden,

woollen,

silken,

golden,

etc.

Adjective-forming

-some

handsome, quarrelsome, tiresome, etc.

Verb-

forming

-en

widen,

redden,

darken,

sadden,

etc.

Adverb-

forming

-ly

warmly,

hardly,

simply,

carefully,

coldly,

etc.

Borrowed

affixes, especially of Romance origin are numerous in the English

vocabulary.

We can recognize words of Latin and French origin by certain suffixes

or

prefixes;

e. g. Latin

affixes:

-ion,

-tion, -ate,

-ute

,

-ct,

-d(e), dis-, -able, -ate,

-ant,

—

ent,

-or, -al, -ar in

such words as opinion,

union, relation, revolution, appreciate,

congratulate,

attribute, contribute, , act, collect, applaud, divide, disable,

disagree,

detestable,

curable, accurate, desperate, arrogant, constant, absent, convenient,

major,

minor, cordial, familiar;

French

affixes –ance,

—ewe,

-ment, -age, -ess, -ous,

en-

in

such words as arrogance,

intelligence, appointment, development, courage,

marriage,

tigress, actress, curious, dangerous, enable, enslaver.

Affixation

includes a) prefixation

–

derivation of words by adding a prefix to

full

words and b) suffixation

–

derivation of words by adding suffixes to bound

stems.

Prefixes

and suffixes have their own valency, that is they may be added not to

any

stem at random, but only to a particular type of stems:

84

Prefix

un-

is

prefixed to adjectives (as: unequal,

unhealthy), or

to adjectives

derived

from verb stems and the suffix -able

(as:

unachievable,

unadvisable), or

to

participial

adjectives (as: unbecoming,

unending, unstressed, unbound); the

suffix —

er

is

added to verbal stems (as: worker,

singer, or

cutter,

lighter), and

to substantive

stems

(as: glover,

needler); the

suffix -able

is

usually tacked on to verb stems (as:

eatable,

acceptable); the

suffix -ity

in

its turn is usually added to adjective stems

with

a passive meaning (as: saleability,

workability), but

the suffix —ness

is

tacked on

to

other adjectives, having the suffix -able

(as:

agreeableness.

profitableness).

Prefixes

and suffixes are semantically distinctive, they have their own

meaning,

while the root morpheme forms the semantic centre of a word. Affixes

play

a

dependent role in the meaning of the word. Suffixes have a

grammatical meaning,

they

indicate or derive a certain part of speech, hence we distinguish:

noun-forming

suffixes,

adjective-forming suffixes, verb-forming suffixes and adverb-forming

suffixes.

Prefixes change or concretize the meaning of the word, as: to

overdo (to

do

too

much),

to underdo (to

do less than one can or is proper),

to outdo (to

do more or

better

than),

to undo (to

unfasten, loosen, destroy the result, ruin),

to misdo (to

do

wrongly

or unproperly).

A

suffix indicates to what semantic group the word belongs. The suffix

-er

shows

that the word is a noun bearing the meaning of a doer of an action,

and the

action

is denoted by the root morpheme or morphemes, as: writer,

sleeper, dancer,

wood-pecker,

bomb-thrower, the

suffix -ion/-tion,

indicates

that it is a noun

signifying

an action or the result of an action, as: translation

‘a

rendering from one

language

into another’ (an

act, process) and

translation

‘the

product of such

rendering’;

nouns with the suffix -ism

signify

a system, doctrine, theory, adherence to

a

system, as: communism,

realism; coinages

from the stem of proper names are

common,.

as Darwinism.

Affixes

can also be classified into productive

and

non-productive

types.

By

productive

affixes we

mean the ones, which take part in deriving new words in a

particular

period of language development. The best way to identify productive

affixes

is to look for them among neologisms

and

so-called nonce-words,

i.e.

words

coined

and used only for this particular occasion. The latter are usually

formed on the

level

of living speech and reflect the most productive and progressive

patterns in

word-building.

When a literary critic writes about a certain book that it is an

unputdownable

thriller, we

will seek in vain this strange and impressive adjective in

dictionaries,

for it is a nonce-word coined on the current pattern of Modern

English

and

is evidence of the high productivity of the adjective-forming

borrowed suffix –

able

and

the native prefix un-,

e.g.: Professor Pringle was a thinnish, baldish,

dyspeptic-lookingish

cove with an eye like a haddock.(From

Right-Ho, Jeeves by P.G.

Wodehouse)

The

adjectives thinnish

and

baldish

bring

to mind dozens of other adjectives

made

with the same suffix: oldish,

youngish, mannish, girlish, fattish, longish,

yellowish,

etc. But

dyspeptic-lookingish

is

the author’s creation aimed at a humorous

effect,

and, at the same time, providing beyond doubt that the suffix –ish

is

a live and

active

one.

85

The

same is well illustrated by the following popular statement: “I

don’t like

Sunday

evenings: I feel so Mondayish”. (Mondayish is

certainly a nonce-word.)

One

should not confuse the productivity of affixes with their frequency

of

occurrence

(use). There are quite a number of high-frequency affixes which,

nevertheless,

are no longer used in word-derivation (e.g. the adjective-forming

native

suffixes

–ful,

-ly; the

adjective-forming suffixes of Latin origin –ant,

-ent, -al which

are

quite frequent).

Some

Productive Affixes

Some

Non-Productive Affixes

Noun-forming

suffixes

-th,

-hood

Adjective-forming

suffixes

—ly,

-some, -en, -ous

Verb-forming

suffix -en

Compound

words are

words derived from two or more stems. It is a very old

word-formation

type and goes back to Old English. In Modern English compounds

are

coined by joining one stem to another by mere juxtaposition, as

raincoat,

keyhole,

pickpocket,

red-hot, writing-table. Each

component of a compound coincides

with

the word. Compounds are the commonest among nouns and adjectives.

Compound

verbs are few in number, as they are mostly the result of conversion

(as,

to

weekend) and

of back-formation (as, to

stagemanage).

From

the point of view of word-structure compounds consist of free stems

and

may

be of different structure: noun stems + noun stem (raincoat);

adjective

stem +

noun

stem (bluebell);

adjective

stem + adjective stem (dark-blue);

gerundial

stem +

noun

stem (writing-table);

verb

stem + post-positive stem (make-up);

adverb

stem +

adjective

stem (out-right);

two

noun stems connected by a preposition (man-of-war)

and

others. There are compounds that have a connecting vowel (as,

speedometer,

handicraft),

but

it is not characteristic of English compounds.

Compounds

may be idiomatic

and

non-idiomatic.

In idiomatic compounds the

meaning

of each component is either lost or weakened, as buttercup

(лютик),

chatter-box

(болтун).

These

are entirely

demotivated compounds. There

are also motivated

compounds,

as lifeboat

(спасательная

лодка). In non-idiomatic compounds the

Noun-forming

suffixes

—er,

-ing,

—ness,

-ism (materialism),

-ist

(impressionist),

-ance

Adjective-forming

suffixes

—y,

-ish, -ed (learned),

—able,

—less

Adverb-forming

suffix

—ly

Verb-forming

suffixes

—ize/-ise

(realize),

—ate

Prefixes

un-

(unhappy),re-

(reconstruct),

dis-

(disappoint)

86

meaning

of each component is retained, as apple-tree,

bedroom, sunlight. There

are

also

many border-line cases.

The

components of compounds may have different semantic relations; from

this

point of view we can roughly classify compounds into endocentric

and

exocentric

compounds.

In endocentric compounds the semantic centre is found

within

the compound and the first element determines the other, as

film-star,

bedroom,

writing-table.

In

exocentric compounds there is no semantic centre, as

scarecrow.

In

Modern English, however, linguists find it difficult to give criteria

for

compound

nouns; it is still a question of hot dispute. The following criteria

may be

offered.

A compound noun is characterized by a) one word or hyphenated

spelling, b)

one

stress, and by c) semantic integrity. These are the so-called

“classical

compounds”.

It

is possible that a compound has only two of these criteria, for

instance, the

compound

words headache,

railway have

one stress and hyphenated or one-word

spelling,

but do not present a semantic unity, whereas the compounds

motor-bike,

clasp-knife

have

hyphenated spelling and idiomatic meaning, but two even stresses

(‘motor-‘bike,

‘clasp-‘knife).

The word apple-tree

is

also a compound; it is spelt either

as

one word or is hyphenated, has one stress (‘apple-tree),

but it is not idiomatic. The

difficulty

of defining a compound lies in spelling which might be misleading, as

there

are

no hard and fast rules of spelling the compounds: three ways of

spelling are

possible:

(‘dockyard,

‘dock yard and

dock-yard).

The

same holds true for the stress

that

may differ from one reference-book to another.

Since

compounds may have two stresses and the stems may be written

separately,

it is difficult to draw the line between compounds proper and nominal

word-combinations

or syntactical combinations. In a combination of words each

element

is stressed and written separately. Compare the attributive

combination

‘black

‘board, a

board which is black (each element has its own meaning; the first

element

modifies the second) and the compound ‘blackboard’,

a

board or a sheet of

slate

used in schools for teaching purposes (the word has one stress and

presents a

semantic

unit). But it is not always easy as that to draw a distinction, as

there are

word-combinations

that may present a semantic unity, take for instance: green

room

(a

room in a theatre for actors and actresses).

Compound

derivatives are

words, usually nouns and adjectives, consisting of

a

compound stem and a suffix, the commonest type being such nouns as:

firstnighter,

type-writer,

bed-sitter, week-ender, house-keeping, well-wisher, threewheeler,

old-timer,

and

the adjectives: blue-eyed,

blond-haired, four-storied, mildhearted,

high-heeled.

The

structure of these nouns is the following: a compound stem

+

the suffix -er,

or

the suffix -ing.

Adjectives

have the structure: a compound stem, containing an adjective (noun,

numeral)

stem and a noun stem + the suffix -ed.

In

Modern English it is an extremely

productive

type of adjectives, e.g.: big-eyed,

long-legged, golden-haired.

In

Modern English it is common practice to distinguish also

semi-suffixes, that

is

word-formative elements that correspond to full words as to their

lexical meaning

and

spelling, as -man,

-proof, -like: seaman, railroadman, waterproof, kiss-proof,

ladylike,

businesslike. The

pronunciation may be the same (cp. proof

[pru:f]

and

87

waterproof

[‘wL:tq

pru:f],

or differ, as is the case with the morpheme -man

(cp.

man

[mxn]

and seaman

[‘si:mqn].

The

commonest is the semi-suffix -man

which

has a more general meaning —

‘a

person of trade or profession or carrying on some work’, as: airman,

radioman,

torpedoman,

postman, cameramen, chairman and

others. Many of them have

synonyms

of a different word structure, as seaman

— sailor, airman — flyer,

workman

— worker; if

not a man but a woman

of

the trade or profession, or a person

carrying

on some work is denoted by the word, the second element is woman,

as

chairwoman,

air-craftwoman, congresswoman, workwoman, airwoman.

Conversion

is

a very productive way of forming new words in English, chiefly

verbs

and not so often — nouns. This type of word formation presents one

of the

characteristic

features of Modern English. By conversion we mean derivation of a

new

word from the stem of a different part of speech without the addition

of any

formatives.

As a result the two words are homonymous, having the same

morphological

structure and belonging to different parts of speech.

Verbs

may be derived from the stem of almost any part of speech, but the

commonest

is the derivation from noun stems as: (a)

tube — (to) tube; (a) doctor —

(to)

doctor, (a) face—(to) face; (a) waltz—(to) waltz; (a) star—(to)

star; from

compound

noun stems as: (a)

buttonhole — (to) buttonhole; week-end — (to) weekend.

Derivations

from the stems of other parts of speech are less common: wrong—

(to)

wrong; up — (to) up; down — (to) down; encore — (to) encore.

Nouns

are

usually

derived from verb stems and may be instanced by such nouns as: (to)

make—

a

make; (to) cut—(a) cut; to bite — (a) bite, (to) drive — (a)

drive; to smoke — (a)

smoke;

(to) walk — (a) walk. Such

formations frequently make part of verb — noun

combinations

as: to

take a walk, to have a smoke, to have a drink, to take a drive, to

take

a bite, to give a smile and

others.

Nouns

may be also derived from verb-postpositive phrases. Such formations

are

very common in Modern English, as for instance: (to)

make up — (a) make-up;

(to)

call up — (a) call-up; (to) pull over — (a) pullover.

New

formations by conversion from simple or root stems are quite usual;

derivatives

from suffixed stems are rare. No verbal derivation from prefixed

stems is

found.

The

derived word and the deriving word are connected semantically. The

semantic

relations between the derived and the deriving word are varied and

sometimes

complicated. To mention only some of them: a) the verb signifies the

act

accomplished

by or by means of the thing denoted by the noun, as: to

finger means

‘to

touch with the finger, turn about in fingers’; to

hand means

‘to give or help with

the

hand, to deliver, transfer by hand’; b) the verb may have the meaning

‘to act as the

person

denoted by the noun does’, as: to

dog means

‘to follow closely’, to

cook — ‘to

prepare

food for the table, to do the work of a cook’; c) the derived verbs

may have

the

meaning ‘to go by’ or ‘to travel by the thing denoted by the noun’,

as, to

train

means

‘to go by train’, to

bus — ‘to

go by bus’, to

tube — ‘to

travel by tube’; d) ‘to

spend,

pass the time denoted by the noun’, as, to

winter ‘to pass

the winter’, to

weekend

— ‘to

spend the week-end’.

88

Derived

nouns denote: a) the act, as a

knock, a hiss, a smoke; or

b) the result of

an

action, as a

cut, a find, a call, a sip, a run.

A

characteristic feature of Modern English is the growing frequency of

new

formations

by conversion, especially among verbs.

Note.

A grammatical homonymy of two words of different parts of speech —

a

verb

and a noun, however, does not necessarily indicate conversion. It may

be the

result

of the loss of endings as well. For instance, if we take the

homonymic pair love

— to

love and

trace it back, we see that the noun love

comes

from Old English lufu,

whereas

the verb to

love—from

Old English lufian,

and

the noun answer

is

traced

back

to the Old English andswaru,

but

the verb to

answer to

Old English

andswarian;

so

that it is the loss of endings that gave rise to homonymy. In the

pair

bus

— (to) bus, weekend — (to) weekend homonymy

is the result of derivation by

conversion.

Shortenings

(abbreviations)

are words produced either by means of clipping

full

word or by shortening word combinations, but having the meaning of

the full

word

or combination. A distinction is to be observed between graphical

and

lexical

shortenings;

graphical abbreviations are signs or symbols that stand for the full

words

or combination of words only in written speech. The commonest form is

an

initial

letter or letters that stand for a word or combination of words. But

to prevent

ambiguity

one or two other letters may be added. For instance: p.

(page),

s.

(see),

b.

b.

(ball-bearing).

Mr

(mister),

Mrs

(missis),

MS

(manuscript),

fig.

(figure). In oral

speech

graphical abbreviations have the pronunciation of full words. To

indicate a

plural

or a superlative letters are often doubled, as: pp.

(pages). It is common practice

in

English to use graphical abbreviations of Latin words, and word

combinations, as:

e.

g. (exampli

gratia), etc.

(et cetera), i.

e. (id

est). In oral speech they are replaced by

their

English equivalents, ‘for

example’,

‘and

so on’,

‘namely‘,

‘that

is’,

‘respectively’.

Graphical

abbreviations are not words but signs or symbols that stand for the

corresponding

words. As for lexical

shortenings,

two main types of lexical

shortenings

may be distinguished: 1) abbreviations

or

clipped

words (clippings)

and

2) initial

words (initialisms).

Abbreviation

or

clipping

is

the result of reduction of a word to one of its

parts:

the meaning of the abbreviated word is that of the full word. There

are different

types

of clipping: 1) back-clipping—the

final part of the word is clipped, as: doc

—

from

doctor,

lab — from

laboratory,

mag — from

magazine,

math — from

mathematics,

prefab —

from prefabricated;

2) fore-clipping

—

the first part of the

word

is clipped as: plane

— from

aeroplane,

phone — from

telephone,

drome —

from

aerodrome.

Fore-clippings

are less numerous in Modern English; 3) the

fore

and

the back parts of the word are clipped and the middle of the word is

retained,

as: tec

— from

detective,

flu — from

influenza.

Words

of this type are few

in

Modern English. Back-clippings are most numerous in Modern English

and are

characterized

by the growing frequency. The original may be a simple word (as,

grad—from

graduate),

a

derivative (as, prep—from

preparation),

a

compound, (as,

foots

— from

footlights,

tails — from

tailcoat),

a

combination of words (as pub —

from

public

house, medico — from

medical

student). As

a result of clipping usually

nouns

are produced, as pram

— from

perambulator,

varsity — for

university.

In

some

89

rare

cases adjectives are abbreviated (as, imposs

—from

impossible,

pi — from

pious),

but

these are infrequent. Abbreviations or clippings are words of one

syllable

or

of two syllables, the final sound being a consonant or a vowel

(represented by the

letter

o), as, trig

(for

trigonometry),

Jap (for

Japanese),

demob (for

demobilized),

lino

(for

linoleum),

mo (for

moment).

Abbreviations

are made regardless of whether the

remaining

syllable bore the stress in the full word or not (cp. doc

from

doctor,

ad

from

advertisement).

The

pronunciation of abbreviations usually coincides with the

corresponding

syllable in the full word, if the syllable is stressed: as, doc

[‘dOk]

from

doctor

[‘dOktq];

if it is an unstressed syllable in the full word the pronunciation

differs,

as the abbreviation has a full pronunciation: as, ad

[xd],

but advertisement

[qd’vq:tismqnt].

There may be some differences in spelling connected with the

pronunciation

or with the rules of English orthoepy, as mike

— from

microphone,

bike

— from

bicycle,

phiz —

from physiognomy,

lube — from

lubrication.

The

plural

form

of the full word or combinations of words is retained in the

abbreviated word,

as,

pants

— from

pantaloons,

digs — from

diggings.

Abbreviations

do not differ from full words in functioning; they take the plural

ending

and that of the possessive case and make any part of a sentence.

New

words may be derived from the stems of abbreviated words by

conversion

(as

to

demob, to taxi, to perm) or

by affixation, chiefly by adding the suffix —y,

-ie,

deriving

diminutives and petnames (as, hanky

— from

handkerchief,

nighty (nightie)

— from

nightgown,

unkie — from

uncle,

baccy — from

tobacco,

aussie — from

Australians,

granny (ie)

— from grandmother).

In

this way adjectives also may be

derived

(as: comfy

— from

comfortable,

mizzy — from

miserable).

Adjectives

may be

derived

also by adding the suffix -ee,

as:

Portugee

— for

Portuguese,

Chinee — for

Chinese.

Abbreviations

do not always coincide in meaning with the original word, for

instance:

doc

and

doctor

have

the meaning ‘one who practises medicine’, but doctor

is

also

‘the highest degree given by a university to a scholar or scientist

and ‘a person

who

has received such a degree’ whereas doc

is

not used in these meanings. Among

abbreviations

there are homonyms, so that one and the same sound and graphical

complex

may represent different words, as vac

(vacation), vac (vacuum cleaner);

prep

(preparation), prep (preparatory school). Abbreviations

usually have synonyms

in

literary English, the latter being the corresponding full words. But

they are not

interchangeable,

as they are words of different styles of speech. Abbreviations are

highly

colloquial; in most cases they belong to slang. The moment the longer

word

disappears

from the language, the abbreviation loses its colloquial or slangy

character

and

becomes a literary word, for instance, the word taxi

is

the abbreviation of the

taxicab

which,

in its turn, goes back to taximeter

cab; both

words went out of use,

and

the word taxi

lost

its stylistic colouring.

Initial

abbreviations (initialisms)

are words — nouns — produced by

shortening

nominal combinations; each component of the nominal combination is

shortened

up to the initial letter and the initial letters of all the words of

the

combination

make a word, as: YCL — Young

Communist League, MP

—

Member

of Parliament. Initial

words are distinguished by their spelling in capital

letters

(often separated by full stops) and by their pronunciation — each

letter gets

90

its

full alphabetic pronunciation and a full stress, thus making a new

word as R.

A.

F. [‘a:r’ei’ef] — Royal

Air Force; TUC.

[‘ti:’ju:’si:] — Trades

Union Congress.

Some

of initial words may be pronounced in accordance with the’ rules of

orthoepy,

as N. A. T. O. [‘neitou], U. N. O. [‘ju:nou], with the stress on the

first

syllable.

The

meaning of the initial word is that of the nominal combination. In

speech

initial words function like nouns; they take the plural suffix, as

MPs, and

the

suffix of the possessive case, as MP’s, POW’s.

In

Modern English the commonest practice is to use a full combination

either

in

the heading or in the text and then quote this combination by giving

the first initial

of

each word. For instance, «Jack Bruce is giving UCS concert»

(the heading). «Jack

Bruce,

one of Britain’s leading rock-jazz musicians, will give a benefit

concert in

London

next week to raise money for the Upper Clyde shop stewards’ campaign»

(Morning

Star).

New

words may be derived from initial words by means of adding affixes,

as

YCL-er,

ex-PM, ex-POW; MP’ess, or adding the semi-suffix —man,

as

GI-man.

As

soon

as the corresponding combination goes out of use the initial word

takes its place

and

becomes fully established in the language and its spelling is in

small letters, as

radar

[‘reidq]

— radio detecting and ranging, laser

[‘leizq]

— light amplification by

stimulated

emission of radiation; maser

[‘meizq]

— microwave amplification by

stimulated

emission of radiation. There are also semi-shortenings, as, A-bomb

(atom

bomb),

H-bomber

(hydrogen

bomber), U-boat

(Untersee

boat) — German submarine.

The

first component of the nominal combination is shortened up to the

initial letter,

the

other component (or components) being full words.

4.7.

ENGLISH PHRASEOLOGY: STRUCTURAL AND SEMANTIC

PECULIARITIES

OF PHRASEOLOGICAL UNITS, THEIR CLASSIFICATION

The

outline of the problem discussed

1.

Main approaches to the definition of a phraseological unit in

linguistics.

2.

Different classifications of phraseological units.

3.

Grammatical and lexical modifications of phraseological units in

speech.

In

linguistics there are two main theoretical schools treating the

problems of

English

phraseology — that of N.N.Amosova and that of A. V. Kunin. We shall

not

dwell

upon these theories in detail, but we shall try to give the guiding

principles of

each

of the authors. According to the theory of N.N. Amosova. A

phraseological unit

is

a unit of constant context. It is a stable combination of words in

which either one of

the

components has a phraseologically bound meaning — a phraseme: white

lie –

невинная

ложь, husband

tea —

жидкий чай), or the meaning of each component is

weakened,

or entirely lost – (an idiom: red

tape —

бюрократия, mare’s

nest —

абсурд).

A. V. Kunin’s theory is based on the concept of specific stability at

the

phraseological

level; phraseological units are crtaracterized by a certain minimum

of

phraseological

stability. A.V. Kunin distinguishes stability of usage, structural

and

semantic

stability, stability of meaning and lexical constituents,

morphological

stability

and syntactical stability. The degree of stability may vary so that

there are

91

several

‘limits’ of stability. But whatever the degree of stability might

be, it is the

idiomatic

meaning that makes the characteristic feature of a phraseological

unit.

There

is one trend more worth mentioning in the theory of English

phraseology

that

of A. I. Smirnitsky. A.I. Smirnitsky takes as his guiding principle

the equivalence

of

a phraseological unit to a word. There are two characteristic

features that make a

phraseological

unit equivalent to a word, namely, the integrity of meaning and the

fact

that both the word and the phraseological unit are ready-made units

which are

reproduced

in speech and are not organized at the speaker’s will.

Whatever

the theory the term phraseology is applied to stable combinations of

words

characterized by the integrity of meaning which is completely or

partially

transferred,

e. g.: to

lead the dance проявлять

инициативу; to

take the cake

одержать

победу. Phraseological units are not to be mixed up with stable

combinations

of words that have their literal meaning, and are of non

phraseological

character,

e.g. the

back of the head, to come to an end.

Among

the phraseological units N.N.Amosova distinguishes idioms,

i.e.

phraseological

units characterized by the integral meaning of the whole, with the

meaning

of each component weakened or entirely lost. Hence, there are

motivated

and

demotivated

idioms.

In a motivated idiom the meaning of each component is

dependent

upon the transferred meaning of the whole idiom, e. g. to

look through

one’s

fingers (смотреть

сквозь пальцы); to

show one’s cards (раскрыть

свои

карты).

Phraseological units like these are homonymous to free syntactical

combinations.

Demotivated idioms are characterized by the integrity of meaning as a

whole,

with the meaning of each of the components entirely lost, e. g. white

elephant

(обременительное

или разорительное имущество), or to

show the white feather

(cтpycить).

But there are no hard and fast boundaries between them and there may

be

many

borderline cases. The second type of phraseological units in N.N.

Amosova’s

classification

is a phraseme.

It is a combination of words one element of which has a

phraseologically

bound meaning, e. g. small

years (детские

годы); small

beer

(слабое

пиво).

According

to A.I. Smirnitsky phraseological units may be classified in respect

to

their structure into one-summit

and

many-summit

phraseological units.

Onesummit

phraseological

units are composed of a notional and a form word, as, in

the

soup

—

быть в затруднительном положении, at

hand —

рядом, under

a cloud –

в

плохом

настроении, by

heart —

наизусть,

in the pink –

в расцвете. Many-summit

phraseological

units are composed of two or more notional words and form words as,

to

take the bull by the horns —

взять быка зарога,

to wear one’s heart on one’s

sleeve

—

выставлять свои чувства на показ, to

kill the goose that laid the golden

eggs

—

уничтожить источник благосостояния;

to

know on which side one’s bread

is

buttered —

быть себе на уме.

Academician

V.V.Vinogradov’s classification is based on the degree of

idiomaticity

and distinguishes three groups of phraseological units:

phraseological

fusions,

phraseological unities, phraseological collocations.

Phraseological

fusions are

completely non-motivated word-groups, e.g.: red

tape

– ‘bureaucratic

methods’; kick

the bucket – die,

etc. Phraseological

unities are

92

partially

non-motivated as their meaning can usually be understood through the

metaphoric

meaning of the whole phraseological unit, e.g.: to

show one’s teeth –

‘take

a threatening tone’; to

wash one’s dirty linen in public – ‘discuss

or make public

one’s

quarrels’.

Phraseological

collocations are

motivated but they are made up of

words

possessing specific lexical combinability which accounts for a

strictly limited

combinability

of member-words, e.g.: to

take a liking (fancy) but

not to

take hatred

(disgust).

There

are synonyms among phraseological units, as, through

thick and thin, by

hook

or by crook, for love or money —

во что бы то ни стало; to

pull one’s leg, to

make

a fool of somebody —

дурачить;

to hit the right nail on the head, to get the

right

sow by the ear —

попасть в точку.

Some

idioms have a variable component, though this variability is.

strictly

limited

as to the number and as to words themselves. The interchangeable

components

may be either synonymous, as

to fling (or throw) one’s (or the) cap over

the

mill (or windmill), to put (or set) one’s (or the) best foot first

(foremost, foreward)

or

different words, not connected semantically,

as to be (or sound, or read) like a

fairy

tale.

Some

of the idioms are polysemantic, as, at

large —

1) на свободе, 2) в

открытом

море, на большом пространстве, 3) без

определенной цели, 4) не

попавший

в цель, 5) свободный, без определенных

занятий, 6) имеющий

широкие

полномочия, 7) подробно, во всем объеме,

конкретно.

It

is the context or speech situation that individualizes the meaning of

the

idiom

in each case.

When

functioning in speech, phraseological units form part of a sentence

and

consequently

may undergo grammatical and lexical changes. Grammatical changes

are

connected with the grammatical system of the language as a whole,

e.g.: He

didn’t

work,

and he spent a great deal of money, and he

painted the town red.

(W. S.

Maugham)

(to

paint the town red —

предаваться веселью). Here

the infinitive is

changed

into the Past Indefinite. Components of an idiom can be used in

different

clauses,

e.g.: …I

had to put up with, the

bricks they

dropped,

and their embarassment

when

they realized what they’d done.

(W. S. Maugham) (to

drop a brick —

допустить

бестактность).

Possessive

pronouns or nouns in the possessive case may be also added, as:

…the

apple of his uncle’s eye…(A.

Christie) (the

apple of one’s eye —

зеница ока).

But

there are phraseological units that do not undergo any changes, e.

g.: She

was

the friend in adversity; other people’s business was meat

and drink to her. (W.

S.

Maugham) (be)

meat and drink (to somebody)

— необходимо как воздух.

Thus,

we distinguish changeable and unchangeable phraseological units.

Lexical

changes are much more complicated and much more various. Lexical

modifications

of idioms achieve a stylistic and expressive effect. It is an

expressive

device

at the disposal of the writer or of the speaker. It is the integrity

of meaning that

makes

any modifications in idioms possible. Whatever modifications or

changes an

idiom

might’ undergo, the integrity of meaning is never broken. Idioms may

undergo

93

various

modifications. To take only some of them: a word or more may be

inserted to

intensify

and concretize the meaning, making it applicable to this particular

situation:

I

hate the idea of Larry making such

a mess of

his life.

(W. S. Maugham) Here the

word

such

intensifies

the meaning of the idiom. I

wasn’t keen on washing

this kind of

dirty

linen in

public. (C.

P. Snow) In this case the inserted this

kind makes

the

situation

concrete.

To

make the utterance more expressive one of the components of the idiom

may

be replaced by some other. Compare: You’re

a

dog in the manger,

aren’t you,

dear?

and: It was true enough: indeed she was a

bitch in the manger.

(A.

Christie)

The

word bitch

has

its own lexical meaning, which, however, makes part of the

meaning

of the whole idiom.

One

or more components of the idiom may be left out, but the integrity of

meaning

of the whole idiom is retained, e.g.: «I’ve

never spoken to you or anyone else

about

the last election. I suppose I’ve got to now. It’s better to

let it lie,»

said Brown.

(C.

P. Snow) In the idiom let

sleeping dogs lie two

of the elements are missing and it

refers

to the preceding text.

In

the following text the idiom to

have a card up one’s sleeve is

modified:

Bundle

wondered vaguely what it was that Bill had

or thought he had-up in his

sleeve.

(A, Christie) The component card

is

dropped and the word have

realizes

its

lexical

meaning. As a result an, allusive metaphor is achieved.

The

following text presents an interesting instance of modification: She

does

not

seem to think you are a

snake in the grass,

though she sees a good deal of grass

for

a snake to be in. (E.

Bowen) In the first part of the sentence the idiom a

snake in

the

grass is

used, and in the second part the words snake

and

grass

have

their own

lexical

meanings, which are, however, connected with the integral meaning of

the

idiom.

Lexical

modifications are made for stylistic purposes so as to create an

expressive

allusive metaphor.

LITERATURE

1.

Arnold I.V. The English Word. – М., 1986.

2.

Antrushina G.B. English Lexicology. – М., 1999.

3.

Ginzburg R.Z., Khidekel S.S. A Course in Modern English

Lexicology. – М.,

1975.

4.

Kashcheyeva M.A. Potapova I.A. Practical English lexicology. – L.,

1974.

5.

Raevskaya N.N. English Lexicology. – К., 1971.

Definition of a Word

A word is a speech sound or a combination of sound having a particular meaning for an idea, object or thought and has a spoken or written form. In English language word is composed by an individual letter (e.g., ‘I’), I am a boy, or by combination of letters (e.g., Jam, name of a person) Jam is a boy. Morphology, a branch of linguistics, deals with the structure of words where we learn under which rules new words are formed, how we assigned a meaning to a word? how a word functions in a proper context? how to spell a word? etc.

Examples of word: All sentences are formed by a series of words. A sentence starts with a word, consists on words and ends with a word. Therefore, there is nothing else in a sentence than a word.

Some different examples are: Boy, kite, fox, mobile phone, nature, etc.

Different Types of Word

There are many types of word; abbreviation, acronym, antonym, back formation, Clipped words (clipping), collocation, compound words, Content words, contractions, derivation, diminutive, function word, homograph, homonym, homophone, legalism, linker, conjunct, borrowed, metonym, monosyllable, polysyllable, rhyme, synonym, etc. Read below for short introduction to each type of word.

Abbreviation

An abbreviation is a word that is a short form of a long word.

Example: Dr for doctor, gym for gymnasium

Acronym

Acronym is one of the commonly used types of word formed from the first letter or letters of a compound word/ term and used as a single word.

Example: PIA for Pakistan International Airline

Antonym

An antonym is a word that has opposite meaning of an another word

Example: Forward is an antonym of word backward or open is an antonym of word close.

Back formation

Back formation word is a new word that is produced by removing a part of another word.

Example: In English, ‘tweeze’ (pluck) is a back formation from ‘tweezers’.

Clipped words

Clipped word is a word that has been clipped from an already existing long word for ease of use.

Example: ad for advertisement

Collocation

Collocation is a use of certain words that are frequently used together in form of a phrase or a short sentence.

Example: Make the bed,

Compound words

Compound words are created by placing two or more words together. When compound word is formed the individual words lose their meaning and form a new meaning collectively. Both words are joined by a hyphen, a space or sometime can be written together.

Example: Ink-pot, ice cream,

Content word

A content word is a word that carries some information or has meaning in speech and writing.

Example: Energy, goal, idea.

Contraction

A Contraction is a word that is formed by shortening two or more words and joining them by an apostrophe.

Example: ‘Don’t’ is a contraction of the word ‘do not’.

Derivation

Derivation is a word that is derived from within a language or from another language.

Example: Strategize (to make a plan) from strategy (a plan).

Diminutive

Diminutive is a word that is formed by adding a diminutive suffix with a word.

Example: Duckling by adding suffix link with word duck.

Function word

Function word is a word that is mainly used for expressing some grammatical relationships between other words in a sentence.

Example: (Such as preposition, or auxiliary verb) but, with, into etc.

Homograph

Homograph is a word that is same in written form (spelled alike) as another word but with a different meaning, origin, and occasionally pronounced with a different pronunciation

Example: Bow for ship and same word bow for shooting arrows.

Homonym

Homonyms are the words that are spelled alike and have same pronunciation as another word but have a different meaning.

Example: Lead (noun) a material and lead (verb) to guide or direct.

Homophone

Homophones are the words that have same pronunciation as another word but differ in spelling, meaning, and origin.

Example: To, two, and too are homophones.

Hyponym

Hyponym is a word that has more specific meaning than another more general word of which it is an example.

Example: ‘Parrot’ is a hyponym of ‘birds’.

Legalism

Legalism is a type of word that is used in law terminology.

Example: Summon, confess, judiciary

Linker/ conjuncts