In other contexts, the term world can also refer to the Earth, as seen in this 1972 photograph by the Apollo 17 crew.

In its most general sense, the term «world» refers to the totality of entities, to the whole of reality or to everything that is.[1] The nature of the world has been conceptualized differently in different fields. Some conceptions see the world as unique while others talk of a «plurality of worlds». Some treat the world as one simple object while others analyze the world as a complex made up of many parts. In scientific cosmology the world or universe is commonly defined as «[t]he totality of all space and time; all that is, has been, and will be». Theories of modality, on the other hand, talk of possible worlds as complete and consistent ways how things could have been. Phenomenology, starting from the horizon of co-given objects present in the periphery of every experience, defines the world as the biggest horizon or the «horizon of all horizons». In philosophy of mind, the world is commonly contrasted with the mind as that which is represented by the mind. Theology conceptualizes the world in relation to God, for example, as God’s creation, as identical to God or as the two being interdependent. In religions, there is often a tendency to downgrade the material or sensory world in favor of a spiritual world to be sought through religious practice. A comprehensive representation of the world and our place in it, as is commonly found in religions, is known as a worldview. Cosmogony is the field that studies the origin or creation of the world while eschatology refers to the science or doctrine of the last things or of the end of the world.

In various contexts, the term «world» takes a more restricted meaning associated, for example, with the Earth and all life on it, with humanity as a whole or with an international or intercontinental scope. In this sense, world history refers to the history of humanity as a whole or world politics is the discipline of political science studying issues that transcend nations and continents. Other examples include terms such as «world religion», «world language», «world government», «world war», «world population», «world economy» or «world championship».

Etymology

The English word world comes from the Old English weorold. The Old English is a reflex of the Common Germanic *weraldiz, a compound of weraz ‘man’ and aldiz ‘age’, thus literally meaning roughly ‘age of man’;[2] this word also led to Old Frisian warld, Old Saxon werold, Old Dutch werolt, Old High German weralt, and Old Norse verǫld.[3]

The corresponding word in Latin is mundus, literally ‘clean, elegant’, itself a loan translation of Greek cosmos ‘orderly arrangement’. While the Germanic word thus reflects a mythological notion of a «domain of Man» (compare Midgard), presumably as opposed to the divine sphere on the one hand and the chthonic sphere of the underworld on the other, the Greco-Latin term expresses a notion of creation as an act of establishing order out of chaos.[4]

Conceptions

Different fields often work with quite different conceptions of the essential features associated with the term «world».[5][6] Some conceptions see the world as unique: there can be no more than one world. Others talk of a «plurality of worlds».[4] Some see worlds as complex things composed of many substances as their parts while others hold that worlds are simple in the sense that there is only one substance: the world as a whole.[7] Some characterize worlds in terms of objective spacetime while others define them relative to the horizon present in each experience. These different characterizations are not always exclusive: it may be possible to combine some without leading to a contradiction. Most of them agree that worlds are unified totalities.[5][6]

Monism and pluralism

Monism is a thesis about oneness: that only one thing exists in a certain sense. The denial of monism is pluralism, the thesis that, in a certain sense, more than one thing exists.[7] There are many forms of monism and pluralism, but in relation to the world as a whole, two are of special interest: existence monism/pluralism and priority monism/pluralism. Existence monism states that the world is the only concrete object there is.[7][8][9] This means that all the concrete «objects» we encounter in our daily lives, including apples, cars and ourselves, are not truly objects in a strict sense. Instead, they are just dependent aspects of the world-object.[7] Such a world-object is simple in the sense that it does not have any genuine parts. For this reason, it has also been referred to as «blobject» since it lacks an internal structure just like a blob.[10] Priority monism allows that there are other concrete objects besides the world.[7] But it holds that these objects do not have the most fundamental form of existence, that they somehow depend on the existence of the world.[9][11] The corresponding forms of pluralism, on the other hand, state that the world is complex in the sense that it is made up of concrete, independent objects.[7]

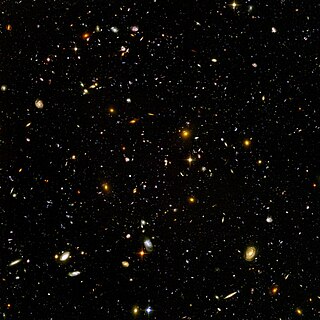

Scientific cosmology

Scientific cosmology can be defined as the science of the universe as a whole. In it, the terms «universe» and «cosmos» are usually used as synonyms for the term «world».[12] One common definition of the world/universe found in this field is as «[t]he totality of all space and time; all that is, has been, and will be».[13][5][6] Some definitions emphasize that there are two other aspects to the universe besides spacetime: forms of energy or matter, like stars and particles, and laws of nature.[14] Different world-conceptions in this field differ both concerning their notion of spacetime and of the contents of spacetime. The theory of relativity plays a central role in modern cosmology and its conception of space and time. An important difference from its predecessors is that it conceives space and time not as distinct dimensions but as a single four-dimensional manifold called spacetime.[15] This can be seen in special relativity in relation to the Minkowski metric, which includes both spatial and temporal components in its definition of distance.[16] General relativity goes one step further by integrating the concept of mass into the concept of spacetime as its curvature.[16] Quantum cosmology, on the other hand, uses a classical notion of spacetime and conceives the whole world as one big wave function expressing the probability of finding particles in a given location.[17]

Theories of modality

The world-concept plays an important role in many modern theories of modality, usually in the form of possible worlds.[18] A possible world is a complete and consistent way how things could have been.[19] The actual world is a possible world since the way things are is a way things could have been. But there are many other ways things could have been besides how they actually are. For example, Hillary Clinton did not win the 2016 US election, but she could have won them. So there is a possible world in which she did. There is a vast number of possible worlds, one corresponding to each such difference, no matter how small or big, as long as no outright contradictions are introduced this way.[19]

Possible worlds are often conceived as abstract objects, for example, in terms of non-obtaining states of affairs or as maximally consistent sets of propositions.[20][21] On such a view, they can even be seen as belonging to the actual world.[22] Another way to conceive possible worlds, made famous by David Lewis, is as concrete entities.[4] On this conception, there is no important difference between the actual world and possible worlds: both are conceived as concrete, inclusive and spatiotemporally connected.[19] The only difference is that the actual world is the world we live in, while other possible worlds are not inhabited by us but by our counterparts.[23] Everything within a world is spatiotemporally connected to everything else but the different worlds do not share a common spacetime: They are spatiotemporally isolated from each other.[19] This is what makes them separate worlds.[23]

It has been suggested that, besides possible worlds, there are also impossible worlds. Possible worlds are ways things could have been, so impossible worlds are ways things could not have been.[24][25] Such worlds involve a contradiction, like a world in which Hillary Clinton both won and lost the 2016 US election. Both possible and impossible worlds have in common the idea that they are totalities of their constituents.[24][26]

Phenomenology

Within phenomenology, worlds are defined in terms of horizons of experiences.[5][6] When we perceive an object, like a house, we do not just experience this object at the center of our attention but also various other objects surrounding it, given in the periphery.[27] The term «horizon» refers to these co-given objects, which are usually experienced only in a vague, indeterminate manner.[28][29] The perception of a house involves various horizons, corresponding to the neighborhood, the city, the country, the Earth, etc. In this context, the world is the biggest horizon or the «horizon of all horizons».[27][5][6] It is common among phenomenologists to understand the world not just as a spatiotemporal collection of objects but as additionally incorporating various other relations between these objects. These relations include, for example, indication-relations that help us anticipate one object given the appearances of another object and means-end-relations or functional involvements relevant for practical concerns.[27]

Philosophy of mind

In philosophy of mind, the term «world» is commonly used in contrast to the term «mind» as that which is represented by the mind. This is sometimes expressed by stating that there is a gap between mind and world and that this gap needs to be overcome for representation to be successful.[30][31][32] One of the central problems in philosophy of mind is to explain how the mind is able to bridge this gap and to enter into genuine mind-world-relations, for example, in the form of perception, knowledge or action.[33][34] This is necessary for the world to be able to rationally constrain the activity of the mind.[30][35] According to a realist position, the world is something distinct and independent from the mind.[36] Idealists, on the other hand, conceive of the world as partially or fully determined by the mind.[36][37] Immanuel Kant’s transcendental idealism, for example, posits that the spatiotemporal structure of the world is imposed by the mind on reality but lacks independent existence otherwise.[38] A more radical idealist conception of the world can be found in Berkeley’s subjective idealism, which holds that the world as a whole, including all everyday objects like tables, cats, trees and ourselves, «consists of nothing but minds and ideas».[39]

Theology

Different theological positions hold different conceptions of the world based on its relation to God. Classical theism states that God is wholly distinct from the world. But the world depends for its existence on God, both because God created the world and because He maintains or conserves it.[40][41][42] This is sometimes understood in analogy to how humans create and conserve ideas in their imagination, with the difference being that the divine mind is vastly more powerful.[40] On such a view, God has absolute, ultimate reality in contrast to the lower ontological status ascribed to the world.[42] God’s involvement in the world is often understood along the lines of a personal, benevolent God who looks after and guides His creation.[41] Deists agree with theists that God created the world but deny any subsequent, personal involvement in it.[43] Pantheists, on the other hand, reject the separation between God and world. Instead, they claim that the two are identical. This means that there is nothing to the world that does not belong to God and that there is nothing to God beyond what is found in the world.[42][44] Panentheism constitutes a middle ground between theism and pantheism. Against theism, It holds that God and the world are interrelated and depend on each other. Against pantheism, it holds that there is no outright identity between the two.[42][45] Atheists, on the other hand, deny the existence of God and thereby of conceptions of the world based on its relation to God.

History of philosophy

In philosophy, the term world has several possible meanings. In some contexts, it refers to everything that makes up reality or the physical universe. In others, it can mean have a specific ontological sense (see world disclosure). While clarifying the concept of world has arguably always been among the basic tasks of Western philosophy, this theme appears to have been raised explicitly only at the start of the twentieth century[46] and has been the subject of continuous debate. The question of what the world is has by no means been settled.

Parmenides

The traditional interpretation of Parmenides’ work is that he argued that the everyday perception of reality of the physical world (as described in doxa) is mistaken, and that the reality of the world is ‘One Being’ (as described in aletheia): an unchanging, ungenerated, indestructible whole.

Plato

Plato is well known for his theory of forms, which posits the existence of two different worlds: the sensible world and the intelligible world. The sensible world is the world we live in, filled with changing physical things we can see, touch and interact with. The intelligible world, on the other hand, is the world of invisible, eternal, changeless forms like goodness, beauty, unity and sameness.[47][48][49] Plato ascribes a lower ontological status to the sensible world, which only imitates the world of forms. This is due to the fact that physical things exist only to the extent that they participate in the forms that characterize them, while the forms themselves have an independent manner of existence.[47][48][49] In this sense, the sensible world is a mere replication of the perfect exemplars found in the world of forms: it never lives up to the original. In the allegory of the cave, Plato compares the physical things we are familiar with to mere shadows of the real things. But not knowing the difference, the prisoners in the cave mistake the shadows for the real things.[50]

Hegel

In Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s philosophy of history, the expression Weltgeschichte ist Weltgericht (World History is a tribunal that judges the World) is used to assert the view that History is what judges men, their actions and their opinions. Science is born from the desire to transform the World in relation to Man; its final end is technical application.

Schopenhauer

The World as Will and Representation is the central work of Arthur Schopenhauer. Schopenhauer saw the human will as our one window to the world behind the representation; the Kantian thing-in-itself. He believed, therefore, that we could gain knowledge about the thing-in-itself, something Kant said was impossible, since the rest of the relationship between representation and thing-in-itself could be understood by analogy to the relationship between human will and human body.

Wittgenstein

Two definitions that were both put forward in the 1920s, however, suggest the range of available opinion. «The world is everything that is the case,» wrote Ludwig Wittgenstein in his influential Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, first published in 1921.[51] This definition would serve as the basis of logical positivism, with its assumption that there is exactly one world, consisting of the totality of facts, regardless of the interpretations that individual people may make of them.

Heidegger

Martin Heidegger, meanwhile, argued that «the surrounding world is different for each of us, and notwithstanding that we move about in a common world».[52] The world, for Heidegger, was that into which we are always already «thrown» and with which we, as beings-in-the-world, must come to terms. His conception of «world disclosure» was most notably elaborated in his 1927 work Being and Time.

Eugen Fink

«World» is one of the key terms in Eugen Fink’s philosophy.[53] He thinks that there is a misguided tendency in western philosophy to understand the world as one enormously big thing containing all the small everyday things we are familiar with.[54] He sees this view as a form of forgetfulness of the world and tries to oppose it by what he calls the «cosmological difference»: the difference between the world and the inner-worldly things it contains.[54] On his view, the world is the totality of the inner-worldly things that transcends them.[55] It is itself groundless but it provides a ground for things. It therefore cannot be identified with a mere container. Instead, the world gives appearance to inner-worldly things, it provides them with a place, a beginning and an end.[54] One difficulty in investigating the world is that we never encounter it since it is not just one more thing that appears to us. This is why Fink uses the notion of play or playing to elucidate the nature of the world.[54][55] He sees play as a symbol of the world that is both part of it and that represents it.[56] Play usually comes with a form of imaginary play-world involving various things relevant to the play. But just like the play is more than the imaginary realities appearing in it so the world is more than the actual things appearing in it.[54][56]

Goodman

The concept of worlds plays a central role in Nelson Goodman’s late philosophy.[57] He argues that we need to posit different worlds in order to account for the fact that there are different incompatible truths found in reality.[58] Two truths are incompatible if they ascribe incompatible properties to the same thing.[57] This happens, for example, when we assert both that the earth moves and that the earth is at rest. These incompatible truths correspond to two different ways of describing the world: heliocentrism and geocentrism.[58] Goodman terms such descriptions «world versions». He holds a correspondence theory of truth: a world version is true if it corresponds to a world. Incompatible true world versions correspond to different worlds.[58] It is common for theories of modality to posit the existence of a plurality of possible worlds. But Goodman’s theory is different since it posits a plurality not of possible but of actual worlds.[57][5] Such a position is in danger of involving a contradiction: there cannot be a plurality of actual worlds if worlds are defined as maximally inclusive wholes.[57][5] This danger may be avoided by interpreting Goodman’s world-concept not as maximally inclusive wholes in the absolute sense but in relation to its corresponding world-version: a world contains all and only the entities that its world-version describes.[57][5]

Religion

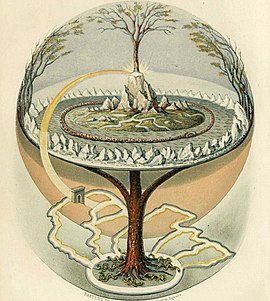

Mythological cosmologies often depict the world as centered on an axis mundi and delimited by a boundary such as a world ocean, a world serpent or similar. In some religions, worldliness (also called carnality)[59][60] is that which relates to this world as opposed to other worlds or realms.

Buddhism

In Buddhism, the world means society, as distinct from the monastery. It refers to the material world, and to worldly gain such as wealth, reputation, jobs, and war. The spiritual world would be the path to enlightenment, and changes would be sought in what we could call the psychological realm.

Christianity

In Christianity, the term often connotes the concept of the fallen and corrupt world order of human society, in contrast to the World to Come. The world is frequently cited alongside the flesh and the Devil as a source of temptation that Christians should flee. Monks speak of striving to be «in this world, but not of this world» — as Jesus said — and the term «worldhood» has been distinguished from «monkhood», the former being the status of merchants, princes, and others who deal with «worldly» things.

This view is clearly expressed by king Alfred the Great of England (d. 899) in his famous Preface to the Cura Pastoralis:

«Therefore I command you to do as I believe you are willing to do, that you free yourself from worldly affairs (Old English: woruldðinga) as often as you can, so that wherever you can establish that wisdom that God gave you, you establish it. Consider what punishments befell us in this world when we neither loved wisdom at all ourselves, nor transmitted it to other men; we had the name alone that we were Christians, and very few had the practices».

Although Hebrew and Greek words meaning «world» are used in Scripture with the normal variety of senses, many examples of its use in this particular sense can be found in the teachings of Jesus according to the Gospel of John, e.g. 7:7, 8:23, 12:25, 14:17, 15:18-19, 17:6-25, 18:36. In contrast, a relatively newer concept is Catholic imagination.

Contemptus mundi is the name given to the belief that the world, in all its vanity, is nothing more than a futile attempt to hide from God by stifling our desire for the good and the holy.[61] This view has been criticised as a «pastoral of fear» by modern historian Jean Delumeau.[62]

During the Second Vatican Council, there was a novel attempt to develop a positive theological view of the World, which is illustrated by the pastoral optimism of the constitutions Gaudium et spes, Lumen gentium, Unitatis redintegratio and Dignitatis humanae.

Eastern Christianity

In Eastern Christian monasticism or asceticism, the world of mankind is driven by passions. Therefore, the passions of the World are simply called «the world». Each of these passions are a link to the world of mankind or order of human society. Each of these passions must be overcome in order for a person to receive salvation (Theosis). The process of Theosis is a personal relationship with God. This understanding is taught within the works of ascetics like Evagrius Ponticus, and the most seminal ascetic works read most widely by Eastern Christians, the Philokalia and The Ladder of Divine Ascent (the works of Evagrius and John Climacus are also contained within the Philokalia). At the highest level of world transcendence is hesychasm which culminates into the Vision of God.

Orbis Catholicus

Orbis Catholicus is a Latin phrase meaning Catholic world, per the expression Urbi et Orbi, and refers to that area of Christendom under papal supremacy.[63] It is somewhat similar to the phrases secular world, Jewish world and Islamic world.

Islam

In Islam, the term «dunya» is used for the world. Its meaning is derived from the root word «dana», a term for «near».[64] It is mainly associated with the temporal, sensory world and earthly concerns, i.e. with this world in contrast to the spiritual world.[65] Some religious teachings warn of our tendency to seek happiness in this world and advise a more ascetic lifestyle concerned with the afterlife.[66] But other strands in Islam recommend a balanced approach.[65]

Mandaeism

In Mandaean cosmology, the world or earthly realm is known as Tibil. It is separated from the World of Light (alma d-nhūra) above and the World of Darkness (alma d-hšuka) below by ayar (aether).[67][68]

Hinduism

Hinduism constitutes a wide family of religious-philosophical views.[69] These views present different perspectives on the nature and role of the world. Samkhya philosophy, for example, is a metaphysical dualism that understands reality as comprising two parts: purusha and prakriti.[70] The term «purusha» stands for the individual conscious self that each of us possesses. Prakriti, on the other hand, is the one world inhabited by all these selves.[71] Samkhya understands this world as a world of matter governed by the law of cause and effect.[70] The term «matter» is understood in a very wide sense in this tradition including both physical and mental aspects.[72] This is reflected in the doctrine of tattvas, according to which prakriti is made up of 23 different principles or elements of reality.[72] These principles include both physical elements, like water or earth, and mental aspects, like intelligence or sense-impressions.[71] The relation between purusha and prakriti is usually conceived as one of mere observation: purusha is the conscious self aware of the world of prakriti but does not causally interact with it.[70]

A very different conception of the world is present in Advaita Vedanta, the monist school among the Vedanta schools.[69] Unlike the realist position defended in Samkhya philosophy, Advaita Vedanta sees the world of multiplicity as an illusion, referred to as Maya.[69] This illusion also includes our impression of existing as separate experiencing selfs called Jivas.[73] Instead, Advaita Vedanta teaches that on the most fundamental level of reality, referred to as Brahman, there exists no plurality or difference.[73] All there is is one all-encompassing self: Atman.[69] Ignorance is seen as the source of this illusion, which results in bondage to the world of mere appearances. But liberation is possible in the course of overcoming this illusion by acquiring the knowledge of Brahman, according to Advaita Vedanta.[73]

Related terms and problems

Worldviews

A worldview is a comprehensive representation of the world and our place in it.[74] As a representation, it is a subjective perspective of the world and thereby different from the world it represents.[75] All higher animals need to represent their environment in some way in order to navigate it. But it has been argued that only humans possess a representation encompassing enough to merit the term «worldview».[75] Philosophers of worldviews commonly hold that the understanding of any object depends on a worldview constituting the background on which this understanding can take place. This may affect not just our intellectual understanding of the object in question but the experience of it in general.[74] It is therefore impossible to assess one’s worldview from a neutral perspective since this assessment already presupposes the worldview as its background. Some hold that each worldview is based on a single hypothesis that promises to solve all the problems of our existence we may encounter.[76] On this interpretation, the term is closely associated to the worldviews given by different religions.[76] Worldviews offer orientation not just in theoretical matters but also in practical matters. For this reason, they usually include answers to the question of the meaning of life and other evaluative components about what matters and how we should act.[77][78] A worldview can be unique to one individual but worldviews are usually shared by many people within a certain culture or religion.

Paradox of many worlds

The idea that there exist many different worlds is found in various fields. For example, Theories of modality talk about a plurality of possible worlds and the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics carries this reference even in its name. Talk of different worlds is also common in everyday language, for example, with reference to the world of music, the world of business, the world of football, the world of experience or the Asian world. But at the same time, worlds are usually defined as all-inclusive totalities.[5][6][15][14] This seems to contradict the very idea of a plurality of worlds since if a world is total and all-inclusive then it cannot have anything outside itself. Understood this way, a world can neither have other worlds besides itself or be part of something bigger.[5][57] One way to resolve this paradox while holding onto the notion of a plurality of worlds is to restrict the sense in which worlds are totalities. On this view, worlds are not totalities in an absolute sense.[5] This might be even understood in the sense that, strictly speaking, there are no worlds at all.[57] Another approach understands worlds in a schematic sense: as context-dependent expressions that stand for the current domain of discourse. So in the expression «Around the World in Eighty Days», the term «world» refers to the earth while in the colonial[79] expression «the New World» it refers to the landmass of North and South America.[15]

Cosmogony

Cosmogony is the field that studies the origin or creation of the world. This includes both scientific cosmogony and creation myths found in various religions.[80][81] The dominant theory in scientific cosmogony is the Big Bang theory, according to which both space, time and matter have their origin in one initial singularity occurring about 13.8 billion years ago. This singularity was followed by an expansion that allowed the universe to sufficiently cool down for the formation of subatomic particles and later atoms. These initial elements formed giant clouds, which would then coalesce into stars and galaxies.[16] Non-scientific creation myths are found in many cultures and are often enacted in rituals expressing their symbolic meaning.[80] They can be categorized concerning their contents. Types often found include creation from nothing, from chaos or from a cosmic egg.[80]

Eschatology

Eschatology refers to the science or doctrine of the last things or of the end of the world. It is traditionally associated with religion, specifically with the Abrahamic religions.[82][83]

In this form, it may include teachings both of the end of each individual human life and of the end of the world as a whole. But it has been applied to other fields as well, for example, in the form of physical Eschatology, which includes scientifically based speculations about the far future of the universe.[84] According to some models, there will be a Big Crunch in which the whole universe collapses back into a singularity, possibly resulting in a second Big Bang afterward. But current astronomical evidence seems to suggest that our universe will continue to expand indefinitely.[84]

World history

World history studies the world from a historical perspective. Unlike other approaches to history, it employs a global viewpoint. It deals less with individual nations and civilizations, which it usually approaches at a high level of abstraction.[85] Instead, it concentrates on wider regions and zones of interaction, often interested in how people, goods and ideas move from one region to another.[86] It includes comparisons of different societies and civilizations as well as considering wide-ranging developments with a long-term global impact like the process of industrialization.[85] Contemporary world history is dominated by three main research paradigms determining the periodization into different epochs.[87] One is based on productive relations between humans and nature. The two most important changes in history in this respect were the introduction of agriculture and husbandry concerning the production of food, which started around 10,000 to 8,000 BCE and is sometimes termed the Neolithic revolution, and the industrial revolution, which started around 1760 CE and involved the transition from manual to industrial manufacturing.[88][89][87] Another paradigm, focusing on culture and religion instead, is based on Karl Jaspers’ theories about the axial age, a time in which various new forms of religious and philosophical thoughts appeared in several separate parts of the world around the time between 800 and 200 BCE.[87] A third periodization is based on the relations between civilizations and societies. According to this paradigm, history can be divided into three periods in relation to the dominant region in the world: Middle Eastern dominance before 500 BCE, Eurasian cultural balance until 1500 CE and Western dominance since 1500 CE.[87] Big history employs an even wider framework than world history by putting human history into the context of the history of the universe as a whole. It starts with the Big Bang and traces the formation of galaxies, the solar system, the earth, its geological eras, the evolution of life and humans until the present day.[87]

World politics

World politics, also referred to as global politics or international relations, is the discipline of political science studying issues of interest to the world that transcend nations and continents.[90][91] It aims to explain complex patterns found in the social world that are often related to the pursuit of power, order and justice, usually in the context of globalization. It focuses not just on the relations between nation-states but also considers other transnational actors, like multinational corporations, terrorist groups, or non-governmental organizations.[92] For example, it tries to explain events like 9/11, the 2003 war in Iraq or the financial crisis of 2007–2008.

Various theories have been proposed in order to deal with the complexity involved in formulating such explanations.[92] These theories are sometimes divided into realism, liberalism and constructivism.[93] Realists see nation-states as the main actors in world politics. They constitute an anarchical international system without any overarching power to control their behavior. They are seen as sovereign agents that, determined by human nature, act according to their national self-interest. Military force may play an important role in the ensuing struggle for power between states, but diplomacy and cooperation are also key mechanisms for nations to achieve their goals.[92][94][95] Liberalists acknowledge the importance of states but they also emphasize the role of transnational actors, like the United Nations or the World Trade Organization. They see humans as perfectible and stress the role of democracy in this process. The emergent order in world politics, on this perspective, is more complex than a mere balance of power since more different agents and interests are involved in its production.[92][96] Constructivism ascribes more importance to the agency of individual humans than realism and liberalism. It understands the social world as a construction of the people living in it. This leads to an emphasis on the possibility of change. If the international system is an anarchy of nation-states, as the realists hold, then this is only so because we made it this way and may well change since this is not prefigured by human nature, according to the constructivists.[92][97]

See also

- Earth

- Globe

- Holon

- List of sovereign states

- Universe

- World map

References

- ^ «World». wordnetweb.princeton.edu. Princeton University. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ «Homework Help and Textbook Solutions | bartleby». www.bartleby.com. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008.

- ^ Orel, Vladimir (2003) A Handbook of Germanic Etymology Leiden: Brill. p. 462 ISBN 90-04-12875-1

- ^ a b c Lewis, David (1986). On the Plurality of Worlds. Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sandkühler, Hans Jörg (2010). «Welt». Enzyklopädie Philosophie. Meiner.

- ^ a b c d e f Mittelstraß, Jürgen (2005). «Welt». Enzyklopädie Philosophie und Wissenschaftstheorie. Metzler. ISBN 9783476021083.

- ^ a b c d e f Schaffer, Jonathan (2018). «Monism». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Schaffer, Jonathan (2007). «From Nihilism to Monism». Australasian Journal of Philosophy. 85 (2): 175–191. doi:10.1080/00048400701343150. S2CID 7788506.

- ^ a b Sider, Theodore (2007). «Against Monism». Analysis. 67 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8284.2007.00641.x.

- ^ Horgan, Terry; Potr, Matja (2000). «Blobjectivism and Indirect Correspondence». Facta Philosophica. 2 (2): 249–270. doi:10.5840/factaphil20002214. S2CID 15340589.

- ^ Steinberg, Alex (2015). «Priority Monism and Part/Whole Dependence». Philosophical Studies. 172 (8): 2025–2031. doi:10.1007/s11098-014-0395-8. S2CID 170436138.

- ^ Bolonkin, Alexander (26 December 2011). Universe, Human Immortality and Future Human Evaluation. Elsevier. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-12-415801-6.

- ^ Zeilik, Michael; Gregory, Stephen A. (1998). «Glossary». Introductory Astronomy & Astrophysics. Saunders College Pub. ISBN 978-0-03-006228-5.

- ^ a b Schreuder, Duco A. (3 December 2014). Vision and Visual Perception. Archway Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-4808-1294-9.

- ^ a b c Fraassen, Bas C. van (1995). «‘World’ is Not a Count Noun». Noûs. 29 (2): 139–157. doi:10.2307/2215656. JSTOR 2215656.

- ^ a b c Zeilik, Michael; Gregory, Stephen A. (1998). «25. Cosmology: The Big Bang and Beyond». Introductory Astronomy & Astrophysics. Saunders College Pub. ISBN 978-0-03-006228-5.

- ^ Dongshan, He; Dongfeng, Gao; Qing-yu, Cai (2014). «Spontaneous creation of the universe from nothing». Physical Review D. 89 (8): 083510. arXiv:1404.1207. Bibcode:2014PhRvD..89h3510H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.89.083510. S2CID 118371273.

- ^ Parent, Ted. «Modal Metaphysics». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d Menzel, Christopher (2017). «Possible Worlds». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Jacquette, Dale (1 April 2006). «Propositions, Sets, and Worlds». Studia Logica. 82 (3): 337–343. doi:10.1007/s11225-006-8101-2. ISSN 1572-8730. S2CID 38345726.

- ^ Menzel, Christopher. «Possible Worlds > Problems with Abstractionism». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Menzel, Christopher. «Actualism > An Account of Abstract Possible Worlds». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ a b Bricker, Phillip (2006). «David Lewis: On the Plurality of Worlds». Central Works of Philosophy, Vol. 5: The Twentieth Century: Quine and After. Acumen Publishing: 246–267. doi:10.1017/UPO9781844653621.014. ISBN 9781844653621.

- ^ a b Berto, Francesco; Jago, Mark (2018). «Impossible Worlds». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Zalta, Edward N. (1997). «A Classically-Based Theory of Impossible Worlds». Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic. 38 (4): 640–660. doi:10.1305/ndjfl/1039540774.

- ^ Ryan, Marie-Laure (2013). «Impossible Worlds and Aesthetic Illusion». Immersion and Distance. Brill Rodopi. ISBN 978-94-012-0924-3.

- ^ a b c Embree, Lester (1997). «World». Encyclopedia of Phenomenology. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- ^ Smith, David Woodruff (2018). «Phenomenology». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Smith, Joel. «Phenomenology». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ a b Price, Huw; McDowell, John (1994). «Mind and World». Philosophical Books. 38 (3): 169–181. doi:10.1111/1468-0149.00066.

- ^ Avramides, Anita. «Philosophy of Mind: Overview». www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Witmer, D. Gene. «Philosophy Of Mind». www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ «Philosophy of mind». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Sosa, Ernest (2015). «Mind-World Relations». Episteme. 12 (2): 155–166. doi:10.1017/epi.2015.8. ISSN 1742-3600. S2CID 147785165.

- ^ Brandom, Robert B. (1996). «Perception and Rational Constraint: McDowell’s Mind and World». Philosophical Issues. 7: 241–259. doi:10.2307/1522910. JSTOR 1522910.

- ^ a b Miller, Alexander (2019). «Realism». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Guyer, Paul; Horstmann, Rolf-Peter (2021). «Idealism». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Stang, Nicholas F. (2021). «Kant’s Transcendental Idealism». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Flage, Daniel E. «Berkeley, George». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ a b Leftow, Brian. «God, concepts of: Classical theism». www.rep.routledge.com. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ a b «Theism». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d Culp, John (2020). «Panentheism». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ «Deism». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ Leftow, Brian. «God, concepts of: Pantheism». www.rep.routledge.com.

- ^ Leftow, Brian. «God, concepts of: Panentheism». www.rep.routledge.com.

- ^ Heidegger, Martin (1982). Basic Problems of Phenomenology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 165. ISBN 0-253-17686-7.

- ^ a b Kraut, Richard (2017). «Plato». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b Brickhouse, Thomas; Smith, Nicholas D. «Plato: 6b. The Theory of Forms». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b Nehamas, Alexander (1975). «Plato on the Imperfection of the Sensible World». American Philosophical Quarterly. 12 (2): 105–117. ISSN 0003-0481. JSTOR 20009565.

- ^ Partenie, Catalin (2018). «Plato’s Myths». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ Biletzki, Anat; Matar, Anat (3 March 2014). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «Ludwig Wittgenstein» (Fall 2016 ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ Heidegger (1982), p. 164

- ^ Elden, Stuart (2008). «Eugen Fink and the Question of the World». Parrhesia: A Journal of Critical Philosophy. 5: 48–59.

- ^ a b c d e Homan, Catherine (2013). «The Play of Ethics in Eugen Fink». Journal of Speculative Philosophy. 27 (3): 287–296. doi:10.5325/jspecphil.27.3.0287. S2CID 142401048.

- ^ a b Halák, Jan (2016). «Beyond Things: The Ontological Importance of Play According to Eugen Fink». Journal of the Philosophy of Sport. 43 (2): 199–214. doi:10.1080/00948705.2015.1079133. S2CID 146382154.

- ^ a b Halák, Jan (2015). «Towards the World: Eugen Fink on the Cosmological Value of Play». Sport, Ethics and Philosophy. 9 (4): 401–412. doi:10.1080/17511321.2015.1130740. S2CID 146764077.

- ^ a b c d e f g Declos, Alexandre (2019). «Goodman’s Many Worlds». Journal for the History of Analytical Philosophy. 7 (6): 1–25. doi:10.15173/jhap.v7i6.3827.

- ^ a b c Cohnitz, Daniel; Rossberg, Marcus (2020). «Nelson Goodman: 6. Irrealism and Worldmaking». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Hemer, C. J. «Worldly» Edited by Geoffrey W. Bromiley The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Revised Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1979–1988

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press. 2019 – via OED Online.

- ^ «Contemptus Mundi : Contempt of the world | Catholic Christian Healing Psychology». www.chastitysf.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011.

- ^ «Parish Missions». Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- ^ Marty, Martin (2008). The Christian World: A Global History. Random House Publishing Group. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-58836-684-9.

- ^ Attas, Islam and Secularism[page needed]

- ^ a b «dunyâ». Concise Encyclopaedia of Islam: Edited on Behalf of the Royal Netherlands Academy. Fourth Impression. Brill. 2001. ISBN 978-0-391-04116-5.

- ^ Oktar, Adnan (1999). «Man’s True Abode: Hereafter». The Truth of the Life of This World.

- ^ Aldihisi, Sabah (2008). The story of creation in the Mandaean holy book in the Ginza Rba (PhD). University College London.

- ^ Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2002). The Mandaeans: ancient texts and modern people. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515385-5. OCLC 65198443.

- ^ a b c d Ranganathan, Shyam. «Hindu Philosophy». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Ruzsa, Ferenc. «Sankhya». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ a b «Indian philosophy — The Samkhya-karikas». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ a b Parrot, Rodney J. (1986). «THE PROBLEM OF THE SĀṂKHYA TATTVAS AS BOTH COSMIC AND PSYCHOLOGICAL PHENOMENA». Journal of Indian Philosophy. 14 (1): 55–77. ISSN 0022-1791. JSTOR 23444164.

- ^ a b c Menon, Sangeetha. «Vedanta, Advaita». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ a b McIvor, David W. «Weltanschauung». International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences.

- ^ a b Bunge, Mario (2010). «1. Philosophy as Worldview». Matter and Mind: A Philosophical Inquiry. Springer Verlag.

- ^ a b De Mijolla-Mellor, Sophie. «Weltanschauung». International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis.

- ^ MARSHALL, GORDON. «Weltanschauung». A Dictionary of Sociology.

- ^ Weber, Erik (1998). «Introduction». Foundations of Science. 3 (2): 231–234. doi:10.1023/A:1009669806878.

- ^ «The Old World-New World Debate and the Columbian Exchange». Wondrium Daily. 31 January 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Long, Charles. «Cosmogony». Encyclopedia of Religion.

- ^ «Cosmogony». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ «Eschatology». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ Owen, H. «Eschatology». Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ a b Halvorson, Hans; Kragh, Helge (2019). «Cosmology and Theology: 7. Physical eschatology». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ a b Bentley, Jerry H. (31 March 2011). Bentley, Jerry H (ed.). «The Task of World History». The Oxford Handbook of World History. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199235810.001.0001. ISBN 9780199235810. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ «What Is World History?». World History Association. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Cajani, Luigi (2011). «Periodization». In Bentley, Jerry H (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of World History. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199235810.013.0004.

- ^ Graeme Barker (2009). The Agricultural Revolution in Prehistory: Why did Foragers become Farmers?. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955995-4.

- ^ «Industrial Revolution». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Baylis, John; Smith, Steve; Owens, Patricia, eds. (2020). «Glossary». The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations (Eighth Edition, New to this ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-882554-8.

- ^ Blanton, Shannon L.; Kegley, Charles W. (2021). «Glossary». World Politics: Trend and Transformation, 17th Edition — 9780357141809 — Cengage. Cengage.

- ^ a b c d e Baylis, John; Smith, Steve; Owens, Patricia, eds. (2020). «Introduction». The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations (Eighth Edition, New to this ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-882554-8.

- ^ Blanton, Shannon L.; Kegley, Charles W. (2021). «2. Interpreting World Politics through the Lens of theory». World Politics: Trend and Transformation, 17th Edition — 9780357141809 — Cengage. Cengage.

- ^ Korab-Karpowicz, W. Julian (2018). «Political Realism in International Relations». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Moseley, Alexander. «Political Realism». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Cristol, Jonathan. «Liberalism». Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Cristol, Jonathan. «Constructivism». Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

External links

Wikiquote has quotations related to World.

- World. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

Media related to World at Wikimedia Commons

By

Last updated:

January 1, 2023

German’s got some unique benefits going for it.

The German language is often parodied for its love of mushing together a bunch of words to create one super-long one.

Like Kraftfahrzeughaftpflichtversicherung (automobile liability insurance) and the previous titleholder for longest German word, Rindfleischetikettierungsueberwachungsaufgabenuebertragungsgesetz (law delegating beef label monitoring — thankfully the law it describes was repealed.)

On the flip-side, Germans are also good at something that involves a bit more brevity: summing up complex concepts and emotional states in just one word.

Contents

- Where to Learn New German Words

-

- 1. Weltschmerz

- 2. Fremdscham

- 3. Treppenwitz

- 4. Mutterseelenallein

- 5. Unwort

- 6. Gemütlichkeit

- 7. Backpfeifengesicht

- 8. Sprachgefühl

- 9. Aufschnitte

- 10. Streicheleinheit

- 11. Sehnsucht

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Where to Learn New German Words

Many websites and apps can help you learn uniquely German words that’ll help you more accurately sum up your web of emotions.

- Deutsche Welle has a regular feature called Word of the Week that features interesting German words and a brief explanation of how they’re used. They also provide an audio file. Download this and learn how to pronounce some of those more tongue-tying words.

- FluentU aims to get your brain in “German mode” so you understand how native speakers use the language in real life. Every video comes with interactive subtitles, flashcards and fun quizzes so you remember what you’ve learned. Check it out with the free trial.

- Easy Languages on YouTube has a feature called “Learning German from the Streets” where they ask passersby to explain German words. There’s even an episode on Weltschmerz. The videos are very easy to follow because they have both German and English subtitles, so it’s a great way to hear complex concepts explained by everyday Germans.

11 Oddly Specifc German Words That Make Other Languages Jealous

Words like these would definitely come in handy in English. You know, when you want to describe a very specific scenario that everyone knows. Instead, we’re limited to giving the same long-winded explanations again and again.

That’s why sometimes it’s just easier for us to stick to the original German words, like Zeitgeist (spirit of the time) or Doppelgänger (look-alike or double).

Here are a few more examples that the English language should consider adding.

1. Weltschmerz

Literally translated to “world pain,” Weltschmerz describes the feeling of having the weight of the world on your shoulders.

You know those days where you watch some moving documentary on Netflix about starving children in some far-off place and suddenly you feel hopeless about the state of our plant?

You have Weltschmerz.

When you read the news, see all the horrible things happening and feel deep resignation about your own inability to do anything about any of it? Weltschmerz. The next time your outlook is too dark and glum to bear seeing another photo exhibit on AIDS, just let your friends know you can’t. Du hast Weltschmerz.

2. Fremdscham

This feeling may arise when you see a Facebook friend post a long-winded rant about something that turns out to be a gag article from The Onion.

Or when you watch one of those clips from America’s Funniest Home Videos where someone gets hurt in a stupid way.

Some might feel Schadenfreude, a German word that is somewhat commonly used in English, which means taking joy in others’ pain.

Instead of this though, you cringe and feel embarrassed for them, almost as if you made the mistake yourself. That’s Fremdscham, literally “stranger shame.”

One might feel this at a party when someone else insults the host’s cooking, only to have the host walk up right behind them. Ouch — that stinging feeling in your stomach? Total Fremdscham.

3. Treppenwitz

English-language comedians have built dozens upon dozens of sitcoms entirely upon the premise of Treppenwitz, like in the Seinfeld episode “The Comeback.” Yet we still don’t have a good way to describe it.

Well, I’ll take a stab at it. You know those times when you get into an argument with someone and you want so badly to say a snappy comeback, but that snappy comeback doesn’t dawn on you until long after the altercation?

That’s a Treppenwitz.

The word literally means “staircase joke,” as in you don’t think of the retort until you’re on the stairs, leaving the scene. Then you kick yourself for not thinking faster. Shoot! Why didn’t I think of that?

4. Mutterseelenallein

This one might come the closest to representing the internet meme “forever alone,” but the imagery it evokes cannot be matched in English.

Mutterseelenallein literally translates to mean “mother’s souls alone,” as in no soul, not even your mother’s, is with you. You’re so alone that not even your mother can stand being with you. Cue the sad violin music.

5. Unwort

Ever the clever linguists, Germans know that sometimes there are words that aren’t really words. They decided that those words deserve their own word to describe them.

That word is Unwort, or un-word. The term is generally used to describe newly created, and often offensive, “words.” There’s even a panel of German linguists that selects an “Un-word of the Year.”

6. Gemütlichkeit

If you tell a German “oh, we have a phrase for Gemütlichkeit in English — feeling cozy,” they’ll instantly correct you.

For German speakers, it’s so much more than that.

The word describes the whole atmosphere of your surroundings. It’s not just the state of being on a soft couch that gives you Gemütlichkeit. It’s being on a soft couch. Under a warm blanket. Surrounded by family. With a cup of hot chocolate in your hands. And maybe a knit cap on your head. It’s the whole experience and feeling that you have of being physically warm, but also metaphorically feeling warm inside your heart.

7. Backpfeifengesicht

In English, one might say someone has “a face only a mother could love.” In German, such faces might also deserve getting punched. Backpfeifengesicht, a “face that should get a slap that whistles across the cheek,” is a face that makes you want to smack that person.

8. Sprachgefühl

Some people just have a knack for learning languages, collecting five, six or seven in their lifetime. It’s like they have a sixth sense for knowing when to say der, die or das. There’s a German word for this: Sprachgefühl, or “language feeling.” According to Wiktionary, it’s the “instinctive or intuitive grasp” of a language.

9. Aufschnitte

This translates to “cold cuts,” but it’s often used not only to describe the pieces of meat on the table, but the whole meal. Often Germans will have a meal of Aufschnitte where they sit down to eat a selection of breads with various fresh cheeses, smoked salmon and thinly sliced meat. It’s often a more convenient alternative to cooking for the whole family after a long day at work and driving on the Autobahn. What’s for dinner? Let’s just have Aufschnitte.

10. Streicheleinheit

Many online dictionaries translate this word to be a noun for “caress,” but when you break down the word, it sounds quite technical.

The word comes from the verb streicheln — to stroke or pet — and the noun Einheit — a unit of measurement. So it literally means “a unit of petting.”

But the way it’s used in practice is more along the lines of what in English might be shortened to TLC — tender love and care. A German might say “Wir alle sehnen uns nach Streicheleinheiten” — we’re all yearning for love and affection. And isn’t that the truth.

11. Sehnsucht

This is another word that describes a complex set of emotions. It comes from sehnen, which means “to yearn or long for,” and Sucht, an obsession, craving or addiction.

Literally, it would mean something like “an obsessive yearning” for something, but that doesn’t quite capture it. It could be used to describe an inconsolable yearning for happiness and the unattainable. It could illustrate that you’re intensely missing something or someone. It may also express a longing for a far-off place.

Either way, it’s a pretty profound emotion to be boiled down into just two syllables.

Feeling Sehnsucht to get out there and start using these unique German words? We are!

Emma Anderson is an American journalist based in Berlin. She regularly writes for Berlin-based, English language publications The Local and EXBERLINER magazine.

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

The Germans are well-known for having a soft spot for long words. Their language’s “Lego-like” grammatical structure allows the tacking together of an inordinate number of elements, so that it’s not unusual at all to be able to describe an ultra-specific concept with a single, ferociously long word in German.

It’s perfectly understandable, then, why American writer Mark Twain quipped, “These are not words; they are alphabetical processions.”

The longest German word

Germany’s most famous, Guinness-record-breaking, 63-letter word (Rindfleischetikettierungsüberwachungsaufgabenübertragunsgesetz) was made obsolete in 2013, but here are some other hilariously long German words to tide you over. No 1 is officially recognised as the longest German word. Good luck trying to say these out loud.

1. Kraftfahrzeug-Haftpflichtversicherung (36)

Officially recognised by the Duden — Germany’s pre-eminent dictionary — as the longest word in German, Kraftfahrzeug-Haftpflichtversicherung is a 36-letter, tongue-tying way of describing a rather, mundane everyday concept: motor vehicle liability insurance. Even if you can’t pronounce it, don’t be caught without it!

2. Streichholzschächtelchen (24)

You’ll be relieved to hear that even native German speakers find this one hard to pronounce. That’s why videos of Germans and foreigners alike trying to pronounce “tschechisches Streichholzschächtelchen” (small, Czech matchboxes) have become something of a sensation on the internet. Practise it and use it to impress your German friends.

3. Arbeiterunfallverischerungsgesetz (33)

Granted, this probably won’t be a word you’ll use everyday. But it’s working quietly in the background to protect you while you’re at work! As part of Germany’s social security system, all employers are obliged to take out occupational accident insurance, which is governed by the occupational accident insurance law (Arbeiterunfallversicherungsgesetz). It insures all workers against injuries or illnesses incurred through their employment.

4. Freundschaftsbeziehungen (23)

This is probably what Mark Twain was referring to when he said, “Some German words are so long they have a perspective.” Freundschaftsbeziehungen means “friendship relationship” and is just a long way of saying “friendship.»

5. Unabhängigkeitserklärungen (26)

This is another time-saving device wrapped up in a nigh-on-impossible-to-pronounce word! Why waste time saying “declarations of independence” when you could say “independencedeclarations”? Now why didn’t the American founding fathers think of that?

6. Nahrungsmittelunverträglichkeit (31)

Potentially very important for those of us with intolerances and intolerances! Formed of two words that are rather long in their own right (Nahrungsmittel and Unverträglichkeit), this 31-letter beastie simply means “food intolerance”. If you’ve got a nut allergy, you should probably learn how to pronounce it.

7. Rechtsschutzversicherungsgesellschaften (39)

Let’s end on a high. Coming in at a cool 39 letters, this word is the longest German word in everyday use, according to the Guinness Book of World Records. Although not officially listed in the Duden, Rechtsschutzversicherungsgesellschaften — meaning insurance companies that provide legal protection — has apparently made its way into everyday speech. Maybe it’s not in the dictionary because no-one could be bothered to write it down…

Enough German words for you?

Okay, okay — enough. Our eyes hurt. Perhaps it’s time to sign up for that German course…

The sci-fi of another language

In the West, we are used to sci-fi written by English-speakers who dream up English-speaking utopias and dystopias. Often in the final reel, humanity is saved by English-speaking heroes. So what should we expect from China’s newly-thriving sci-fi scene?

The sci-fi of another language

How soccer became multilingual

Professional soccer used to export its English-language terminology, giving other languages words like «penalty» and «goal.» But now, the roles are reversed. English-speakers use expressions loaned from other languages to describe skill moves: «rabona,» «panenka,» «gegenpress.»

How soccer became multilingual

How the Basque language has survived

This week on the podcast we talk about Basque. How did this language survive the military dictatorship of Francisco Franco when speaking and writing and reading were illegal? With more than six dialects, how did Basque develop a language standard? And how has this minority language thrived and even grown in the years since Francisco Franco’s dictatorship ended?

How the Basque language has survived

This is your brain on improv

Ever wondered about people who can improvise on stage? Neuroscientist Charles Limb and comedian Anthony Veneziale did. First came the bromance, then Veneziale found himself improvising inside an fMRI machine.

This is your brain on improv

The hardest question for a third culture kid: Where is home?

Karolina lives in Boston but grew up in several countries and speaks a bunch of languages. Her English is perfect but she doesn’t feel completely at home in it, or in American culture. Welcome to the world of third culture kids, a fast-growing group of people who fit in everywhere and nowhere.

The hardest question for a third culture kid: Where is home?

If you could talk to the animals

What’s the meaning of all those howls and growls? Is it language? This week on the podcast, NOVA’s Ari Daniel explores how three species communicate.

If you could talk to the animals

Why we are so drawn to the letter ‘X’

From X-rated to Gen X to Latinx, the meaning of «X» has shifted while retaining an edgy, transgressive quality.

Why we are so drawn to the letter ‘X’

The three-letter word that rocked a nation

In 2012, Sweden erupted in a national debate over the pronoun «hen.» Traditionally, Swedish has gendered pronouns when referring to people. There is no gender-neutral pronoun for people. «Hen» was a new word meant to fill a gap in the language. This week on The World in Words podcast we explore how a little-known and little-used word went mainstream in Sweden.

The three-letter word that rocked a nation

A British ‘Mx.’ tape

Mx. is a gender-neutral title that’s gaining popularity in the UK. Though the road to acceptance for this prefix has not been without a struggle. On The World in Words podcast, we delve into the fight over this two-letter word.

A British ‘Mx.’ tape

The secretive language of professional wrestling

In 1984 professional wrestler Dr. «D» David Schultz smacked the TV journalist John Stoessel to the ground backstage at Madison Square Garden. Why? One word: kayfabe. This week on The World in Words we throw on some tights and get into the ring to explore this word you were never supposed to hear.

The secretive language of professional wrestling