A

vowel sound whose quality doesn’t change over the duration of the

vowel is called a monophthong.

Monophthongs are sometimes called «pure» or «stable»

vowels. A vowel sound that glides from one quality to another is

called a diphthong,

and a vowel sound that glides successively through three qualities is

a triphthong.

All languages have monophthongs and many languages have diphthongs,

but triphthongs or vowel sounds with even more target qualities are

relatively rare cross-linguistically. English has all three types:

the vowel sound in hit

is a monophthong [ɪ],

the vowel sound in boy

is in most dialects a diphthong [ɔɪ],

and the vowel sounds of, flower

(BrE

[aʊə]

AmE

[aʊɚ])

form a triphthong (disyllabic in the latter cases), although the

particular qualities vary by dialect.

In

phonology,

diphthongs and triphthongs are distinguished from sequences of

monophthongs by whether the vowel sound may be analyzed into

different phonemes

or not. For example, the vowel sounds in a two-syllable pronunciation

of the word flower

(BrE

[flaʊə]

AmE

[flaʊɚ])

phonetically form a disyllabic triphthong, but are phonologically a

sequence of a diphthong (represented by the letters <ow>) and a

monophthong (represented by the letters <er>). Some linguists

use the terms diphthong

and triphthong

only in this phonemic sense.

From the articulatory point of view an English diphthong is an

indivisible phonetic whole. It is necessary to give different

definitions by different scholars. It is important to pay attention

to the position of the tongue while pronouncing the nuclei of the

diphthong, which can be the reason for many mistakes. It is necessary

to think over the causes of mistakes and ways of eliminating them.

Vowels

are the class of sound which makes the least obstruction to the flow

of air. They are almost always found at the centre of a syllable,

and it is rare to find any sound other than a vowel which is able to

stand alone as a whole syllable. In phonetic terms, each vowel has a

number of properties that distinguish it from other vowels. These

include the shape of the lips, which may be rounded (as for an [ u

]

vowel), neutral (as for ([e])

or spread (as in a smile, or an [ i

]

vowel – photographers traditionally ask their subjects to say

«cheese» /

tʃi:z

/

so that they will seem to be smiling). Secondly, the front, the

middle or the back of the tongue

may

be raised, giving different vowel qualities: the BBC English / a

/

vowel (‘cat’) is a front vowel, while the / a:

/

of ‘cart’ is a back vowel. The tongue (and the lower jaw) may be

raised close to the roof of the mouth, or the tongue may be left low

in the mouth with the jaw comparatively open. In British phonetics we

talk about ‘close’ and ‘open’ vowels, whereas American phoneticians

more often talk about ‘high’ and ‘low’ vowels. The meaning is clear

in either case.

Vowels

also differ in other ways: they may be nasalised

by

being pronounced with the soft

palate lowered

as for [ n

]

or [ m

]

– this effect is phonemically contrastive in French, where we find

«minimal

pairs»

such as très / trÈ

/

(«very») and ‘train’ / trÈ

/

(«train»), where the /`/

diacritic

indicates nasality. Nasalised vowels are found frequently in English,

usually close to nasal consonants: a word like ‘morning’ / mɔ:niŋ

/

is likely to have at least partially nasalised vowels throughout the

whole word, since the soft palate must be lowered for each of the

consonants. Vowels may be voiced, as the great majority are, or

voiceless, as happens in some languages,

unstressed

vowels in the last syllable of a word are often voiceless and in

English the first vowel in ‘perhaps’ or ‘potato’ is often voiceless.

It is claimed that in some languages (probably including English)

there is a distinction to be made between tense

and

lax

vowels,

the former being made with greater force than the latter. In

phonetics,

a vowel

is a sound

in spoken language,

such as English ah!

[ɑː]

or oh!

[oʊ],

pronounced with an open vocal

tract

so that there is no build-up of air pressure at any point above the

glottis.

This contrasts with consonants,

such as English sh!

[ʃː],

where there is a constriction or closure at some point along the

vocal tract. A vowel is also understood to be syllabic:

an equivalent open but non-syllabic sound is called a semivowel.

In all languages, vowels form the nucleus

or peak of syllables, whereas consonants

form the onset

and (in languages which have them) coda.

However, some languages also allow other sounds to form the nucleus

of a syllable, such as the syllabic l

in the English

word table

[ˈteɪ.bl̩]

(the stroke under the l

indicates that it is syllabic; the dot separates syllables).

We

might note the conflict between the phonetic definition of ‘vowel’ (a

sound produced with no constriction in the vocal tract) and the

phonological definition (a sound that forms the peak of a syllable).

The approximants

[j] and [w] illustrate this conflict: both are produced without much

of a constriction in the vocal tract (so phonetically they seem to be

vowel-like), but they occur on the edge of syllables, such as at the

beginning of the English words ‘yes’ and ‘wet’ (which suggests that

phonologically they are consonants). The American linguist Kenneth

Pike

suggested the terms ‘vocoid’ for a phonetic vowel and ‘vowel’ for a

phonological vowel, so using this terminology, [j] and [w] are

classified as vocoids but not vowels. The word vowel

comes from the Latin

word vocalis,

meaning «speaking», because in most languages words and

thus speech are not possible without vowels. Vowel

is commonly used to mean both vowel sounds and the written symbols

that represent them.

Where

symbols appear in pairs, the one to the right represents

a

rounded

vowel. Vowel

length

is indicated by appending ː

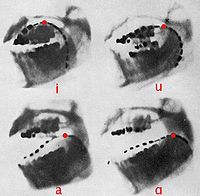

Fig.

1. X-rays of Daniel Jones’ [i,

u, a, ɑ].

The

articulatory

features

that distinguish different vowel sounds are said to determine the

vowel’s quality.

Daniel

Jones

developed the cardinal

vowel

system to describe vowels in terms of the common features height

(vertical dimension), backness

(horizontal dimension) and roundedness

(lip position). These three parameters are indicated in the schematic

IPA vowel

diagram

on the right. There are however still more possible features of vowel

quality, such as the velum position (nasality), type of vocal fold

vibration (phonation), and tongue root position.

Vowel

height is named for the vertical position of the tongue relative to

either the roof of the mouth or the aperture of the jaw.

In high

vowels,

such as [i]

and [u],

the tongue is positioned high in the mouth, whereas in low

vowels,

such as [a],

the tongue is positioned low in the mouth. The IPA prefers the terms

close

vowel

and open

vowel,

respectively, which describes the jaw as being relatively open or

closed. However, vowel height is an acoustic rather than articulatory

quality, and is defined today not in terms of tongue height, or jaw

openness, but according to the relative frequency of the first

formant

(F1). The higher the F1 value, the lower (more open) the vowel;

height is thus inversely correlated to F1.

The

International

Phonetic Alphabet

identifies seven different vowel heights:

-

close

vowel

(high vowel) -

near-close

vowel -

close-mid

vowel -

mid

vowel -

open-mid

vowel -

near-open

vowel -

open

vowel

(low vowel)

True

mid vowels do not contrast with both close-mid and open-mid in any

language, and the letters [e

ø ɤ

o]

are typically used for either close-mid or mid vowels.

Although

English contrasts all six contrasting heights in its vowels, these

are interdependent with differences in backness,

and many are parts of diphthongs.

It appears that some varieties of German

have five contrasting vowel heights independently of length or other

parameters. The Bavarian

dialect of Amstetten

has thirteen long vowels, reported to distinguish four heights

(close, close-mid, mid, and near-open) each among the front

unrounded, front rounded, and back rounded vowels, plus an open

central vowel: /i

e ɛ̝

æ̝/,

/y ø œ̝

ɶ̝/,

/u o ɔ̝

ɒ̝/,

/a/.

Otherwise, the usual limit on the number of contrasting vowel heights

is four.

The

parameter of vowel height appears to be the primary feature of vowels

cross-linguistically in that all languages use height contrastively.

No other parameter, such as front-back or rounded-unrounded (see

below), is used in all languages. Some languages have vertical

vowel systems

in which, at least at a phonemic level, only height is used to

distinguish vowels.

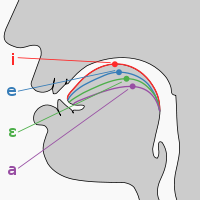

Tongue

positions of cardinal

front vowels with highest point indicated. The position of the

highest point is used to determine vowel height and backness. Vowel

backness is named for the position of the tongue during the

articulation of a vowel relative to the back of the mouth. In front

vowels, such as [i],

the tongue is positioned forward in the mouth, whereas in back

vowels, such as [u],

the tongue is positioned towards the back of the mouth. However,

vowels are defined as back or front not according to actual

articulation, but according to the relative frequency of the second

formant

(F2). The higher the F2 value, the fronter the vowel; backness is

thus inversely correlated to F2.

The

International

Phonetic Alphabet

identifies five different degrees of vowel backness:

-

front

vowel -

near-front

vowel -

central

vowel -

near-back

vowel -

back

vowel

Although

English has vowels at all five degrees of backness, there is no known

language that distinguishes all five without additional differences

in height or rounding.

Roundedness

refers to whether the lips are rounded or not. In most languages,

roundedness is a reinforcing feature of mid to high back vowels, and

is not distinctive. Usually the higher a back vowel is, the more

intense the rounding.

Different

kinds of labialization

are also possible. In mid to high rounded back vowels the lips are

generally protruded («pursed») outward, a phenomenon known

as exolabial

rounding

because the insides of the lips are visible, whereas in mid to high

rounded front vowels the lips are generally «compressed»,

with the margins of the lips pulled in and drawn towards each other,

a phenomenon known as endolabial

rounding.

In many phonetic treatments, both are considered types of rounding,

but some phoneticians do not believe that these are subsets of a

single phenomenon of rounding, and prefer instead the three

independent terms rounded

(exolabial), compressed

(endolabial), and spread

(unrounded).

Nasalization

refers to whether some of the air escapes through the nose. In nasal

vowels,

the velum

is lowered, and some air travels through the nasal cavity as well as

the mouth. An oral vowel is a vowel in which all air escapes through

the mouth.

Phonation.

Voicing

describes whether the vocal

cords are vibrating during the articulation of a vowel. Most

languages only have voiced vowels, but several Native American

languages contrast voiced and devoiced vowels. The combination of

phonetic cues (i.e. phonation, tone, stress) is known as register

or register

complex.

Rhotic

vowels or R-colored

vowels.

Rhotic

vowels

are the «R-colored vowels» of English and a few other

languages.

Tenseness/checked

vowels vs. free vowels. Tenseness.

Tenseness

is used to describe the opposition of tense

vowels

as in leap,

suit

vs. lax

vowels

as in lip,

soot.

This opposition has traditionally been thought to be a result of

greater muscular tension, though phonetic experiments have repeatedly

failed to show this. Unlike the other features of vowel quality,

tenseness is only applicable to the few languages that have this

opposition (mainly Germanic

languages, e.g. English.

In discourse about the English language, «tense and lax»

are often used interchangeably with «long and short»,

respectively, because the features are concomitant in the common

varieties of English. This cannot be applied to all English dialects

or other languages. In most Germanic

languages,

lax vowels can only occur in closed syllables.

Therefore, they are also known as checked

vowels,

whereas the tense vowels are called free

vowels since they can occur in any kind of syllable.

The

first who tried to describe and classify vowel sounds irrespective of

the mother tongue was D.

Jones.

He devised the system of 8

Cardinal Vowels.

This system is an international standard. The basis of the system is

physiological. The starting point of the tongue position is for i

(the front of the tongue raised as close as possible to the palate).

No.

1 i

is equivalent to the French sound of i

in

si,

German

sound of ie

in

Biene.

The

gradual lowering of the tongue to the back lowest position gives

another point which is easily felt (No. 5 ).

The

tongue position between these points was X-rayed and equidistant

points were found. For the front position of the tongue they are

No.

1 i

mentioned above,

No.

2 e.

French sound of e

in

thé;

Scottish

pronunciation of, ay

in

day.

No.

3 ε.

French sound of ê

in

тêте.

No.

4 a.

French sound of a

in

la.

If

we compare these four Cardinal Vowels with the Ukrainian vowel

system, we may state

that:

No.

1 cardinal i

is pronounced with the position of the tongue higher than for the

Ukrainian

accented і

in the word міліграм.

No.

2 cardinal e

is pronounced with the position of the tongue narrower than the

Ukrainian

e

in the word тесть.

No.

3 is similar to the Ukrainian

е

in

the word етап.

For

the back position of the tongue four auditory equidistant points were

also established (from the lowest to the highest position of the back

part of the tongue). They are:

No.

5 .

Nearly what is obtained by taking away the lip-rounding from English

sound of о

in hot;

French

vowel a

in

pas.

No.

6

כ.

German sound of о

in

Sonne.

No.

7 о.

French

sound of o

in rose,

Scottish

o

in rose.

No.

8 u.

German sound of и

in

gut.

There

are no sounds similar to Nos 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 in Ukrainian.

In

spite of the theoretical significance of the Cardinal

Vowel System

its practical application is limited to the field where no comparison

is needed, in purely scientific work. In language teaching this

system can be learned only by oral instruction from a teacher who

knows how to pronounce the Cardinal

Vowels.

Those who have access neither to a qualified teacher, nor to

recordings cannot expect to learn the values of these or any other

cardinal vowels with accuracy.

Acoustically

vowels are musical tones (not noises): the word «vowel» is

a derivative of «voice». Acoustically

vowels differ due to their tembral coloring, each vowel is

characterized by its own formants (that is concentrations of energy

in certain frequency regions on the spectrogram).

Phoneticians

suggest classifying vowels according to the following principles:

-

Position

of the lips -

Position

of the tongue -

Degree

of tenseness and the character of the end of a vowel -

Length

-

Stability

of articulation

According

to the position of the lips

vowels are classified into: (a) rounded,

(b)

unrounded.

The

Ukrainian rounded vowels are pronounced with more lip protrusion than

the English rounded vowels. The English rounded vowels are: /u –

u:, כ

– כ:/,

the Ukrainian rounded and protruded vowels are: /о,

у/.

According

to the position of the tongue

it is the bulk of the tongue which conditions most of all the

production of different vowels. It can move forward and backward, it

may be raised and lowered in the mouth cavity.

Nowadays

scientists divide vowels according to the (a) horizontal

and

(b) vertical

movements

of the tongue.

-

horizontal

–

When the bulk of the tongue moves backwards, it is usually the back

part of the tongue which is raised highest towards the soft palate.

Vowels produced with the tongue in this position are called back.

They

are subdivided into:

fully

back:

/כ

,

כ:,

u:/, the nuclei of the diphthong /כi/,

and the Ukrainian /o, y/

back-advanced:

/

Λ,

υ,

:/and

the nuclei of the diphthongs /∂υ,

υ∂/.

When

the bulk of the tongue moves forward, it is usually the front part of

the tongue which is raised highest towards the hard palate. Vowels

produced with this position of the tongue

are called front.

They

are subdivided into:

fully

front:

/i:,

e, æ/, the nuclei of the diphthongs /ei, ε∂,

ai/ and the Ukrainian /i, e/;

front-retracted:

/I/

and

the nucleus of the diphthong /аυ/.

The

term front

is

not quite correct, because the front vowels are produced by the

action of the mouth resonator, which is in the back part of the mouth

cavity and the raised front of the tongue.

There

is some controversy in the subdivision (and terming) of vowels into

front and front-retracted, back and back-advanced (e.g., whether /i:/

& /I/

are different phonemes (sounds different not only in quantity but

mainly in quality) or they are variants of one and the same phoneme;

the same about /u:/ & /υ/).

Terminological

controversy about vowels is only of academic interest because in

speech the «cardinal» points mentioned in the diagrams of

vowels are slightly altered. The guiding principle in teaching

English vowel sounds should be accurate articulatory description

accompanied by diagrams and drills.

In

the production of mixed,

or central, vowels the tongue is raised towards the junction between

the hard and the soft palate, e.g., the Ukrainian vowel /a/, Russian

/ы/.

They are produced neither in the front, nor in the back part of the

mouth cavity.

Some

British phoneticians consider /∂,

з:/

«central». D.

Jones

says that the central part of the tongue is raised highest and it is

culminating at the junction between «front» and «back».

He regards /∂,

∂:/

as variants of one phoneme. However, Н.

Sweet

defines /∂,

∂:/

as «mixed».

Ukrainian

& Russian phoneticians also define the vowels /∂,

∂:/

as «mixed», because the tongue position in their production

is different from that of the Ukrainian central /а/

or Russian central /ы/.

-

vertical

–

According to the vertical movements of the tongue vowels are

subdivided into:

high:

/i:,

I,

u, u:/ and /i, у,

и/;

mid,

half open /e,

∂:,

о(u),

ε(∂),

∂/

and /e, о/;

low,

open: /Λ,

כ:,

æ, a(i, u), :,

כ,

כ(i)/

and /a/.

Each

of the subclasses is subdivided into vowels of narrow

variation

and vowels of broad

variation:

|

high |

narrow |

/i:, |

|

broad |

/I, |

|

|

mid |

narrow |

/e, |

|

broad |

/ε(∂), |

|

|

Low |

narrow |

/Λ, |

|

broad |

/:, |

The

Ukrainian /e, о/

are placed on the border of the mid-open vowels of broad and narrow

variation.

According

to the degree of tenseness

traditionally long vowels are defined as tense

and

short as lax.

The

term «tense» was introduced by H.

Sweet,

who stated that the tongue is tense when vowels of narrow variety are

articulated. This statement is a confusion of two problems: acoustic

and articulatory ones, because «tenseness» is an acoustic

notion and should be treated in terms of acoustic data. However, this

phenomenon is connected with the articulation of vowels in unaccented

syllables (unstressed vocalism). The decrease of tenseness results in

the reduction of vowels, that is in an unstressed position they may

lose their qualitative characteristics.

When

the muscles of the lips, tongue, cheeks and the back walls of the

pharynx are tense, the vowels

produced can be characterized as «tense«.

When these organs are relatively relaxed, lax

vowels

are produced. There are different opinions in referring English

vowels to the first or to the second group. Some consider only the

long /i:/ and /u:/ to be tense.

Some

define all long English vowels as tense

as

well as /æ/.

This

problem can be solved accurately only with the help of precise

electronic instruments. The Ukrainian vowels are not differentiated

according to their tenseness but one and the same vowel is tense in a

stressed syllable compared with its tenseness in an unstressed one.

Some

phoneticians suggest subdividing vowels according to the character of

the end into «checked» and «free». This principle

of vowel classifications is not singled out by British and American

phoneticians.

When

the intensity of the vowel does not diminish towards its end, such

vowel is called «checked». When the intensity of the vowel

decreases, the vowel is called «free». This problem is

closely connected with articulatory transitions in syllable division

and should be treated in terms of acoustic properties of vowels on

the syllable level.

According

to the length vowels

are subdivided into: (historically) long

and

(historically) short.

Vowel

length depends on a number of linguistic factors:

-

position

of the vowel in a word, -

word

accent, -

the

number of syllables in a word, -

the

character of the syllabic structure, -

sonority.

(1)

Positional dependence of length can be illustrated by the following

example:

be

– bead – bit

we

– weed – wit

fee

– feed – feet

In

the terminal position a vowel is the longest, it shortens before a

voiced consonant, it is the shortest before a voiceless consonant.

(2)

A vowel is longer in an accented syllable, than in an unaccented one:

forecast

n

/’fo:ka:st/

– прогноз

to

forecast v

/fo:’ka:st/

– прогнозувати

(погоду)

In

the second example /כ:/

is shorter than in the first, though it may be pronounced with /כ:/

equally long.

(3)

If we compare a one-syllable word and the word consisting of more

than one syllable, we may observe that similar vowels are shorter in

a polysyllabic word. Thus in the word verse

/∂:/

is longer than in university.

(4)

In words with V, CV, CCV type of syllable (open) the vowel length is

greater than in words with VC, CVC, CCVC (closed) type of syllable.

For example, /∂:/

is longer in err

(V

type), than in earn

(CVC

type), /ju:/ is longer in dew

(CV

type), than in duly

(CVCV

type).

(5)

Vowels

of low sonority are longer, than vowels of greater sonority. It is

so, because the speaker unconsciously makes more effort to produce

greater auditory effect while pronouncing vowels of lower sonority,

thus making them longer. For example, /I/

is longer than /כ/,

/i:/ is longer than /a:/, etc.

Besides,

vowel length depends on the tempo of speech: the higher the rate of

speech the shorter the vowels.

Length

is a non-phonemic feature in English but it may serve to

differentiate the meaning of a word. This can be proved by minimal

pairs, e.g.

beat

– bit /bi:t – bit/

deed

– did /di:d – did/

The

English long vowels are /i:, u:, כ:,

а:,

∂:/.

The

English short vowels are /I,

e, æ, כ,

Λ,

∂/.

The

stability of articulation

is the principle of vowel classification which is not singled out by

British and American phoneticians. In fact, it is the principle of

the stability of the shape, volume and the size of the mouth

resonator.

We

can speak only of relative stability of the organs of speech, because

pronunciation of a sound is a process, and its stability should be

treated conventionally.

According

to this principle vowels are subdivided into:

-

monophthongs,

or simple vowels, -

diphthongoids,

-

diphthongs,

or complex vowels.

-

English

monophthongs

are

pronounced with the more or less stable lip, tongue and the mouth

walls position. They are: /I,

e, æ, :,

כ,

כ:,

υ,

Λ,

∂:,

∂/. -

A

diphthongoid

is

a vowel, which ends in a different element, yet producing neither

impression nor effect of a diphthong. There are two diphthongoids in

English: /i:, u:/. -

Diphthongs

are

defined differently by different authors. One definition is based on

the ability of a vowel to form a syllable. Since in the diphthong

only one element serves as a syllabic nucleus, a diphthong is a

single sound.

Another

definition of a diphthong as a single sound is based on the

instability of the second element. The third group of scientists

define a diphthong from the accentual point of view: since only one

element is accented and the other is unaccented, a diphthong is a

single sound.

-

“unisyllabic

gliding sound in the articulation of which the organs of speech

start from one position and then glide to the other position.” -

“phonemically

diphthongs are sounds that cannot be divided morphologically”.

E.g. the Ukrainian /ай/

in can be separated: ча—ю.

The

first element of a diphthong is the nucleus,

the

second is the glide.

A

diphthong can

be falling

–

when the nucleus is stronger than the glide, and rising

–

when the glide is stronger than the nucleus. When both elements are

equal such diphthongs are called level.

English

diphthongs are falling with the glide toward:

i

– /ei, ai, oi/,

u

– /u,

ou/,

∂ – /i∂,

ε∂,

υ∂/

Diphthongs

/ei, ou, כi,

au, ai/ are called closing,

diphthongs

/ε∂,

i∂,

ээ,

υ∂/

are called centring,

according

to the articulatory character of the second element.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

A vowel is a syllabic speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract.[1] Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness and also in quantity (length). They are usually voiced and are closely involved in prosodic variation such as tone, intonation and stress.

The word vowel comes from the Latin word vocalis, meaning «vocal» (i.e. relating to the voice).[2] In English, the word vowel is commonly used to refer both to vowel sounds and to the written symbols that represent them (a, e, i, o, u, and sometimes w and y).[3]

Definition[edit]

There are two complementary definitions of vowel, one phonetic and the other phonological.

- In the phonetic definition, a vowel is a sound, such as the English «ah» or «oh» , produced with an open vocal tract; it is median (the air escapes along the middle of the tongue), oral (at least some of the airflow must escape through the mouth), frictionless and continuant.[4] There is no significant build-up of air pressure at any point above the glottis. This contrasts with consonants, such as the English «sh» [ʃ], which have a constriction or closure at some point along the vocal tract.

- In the phonological definition, a vowel is defined as syllabic, the sound that forms the peak of a syllable.[5] A phonetically equivalent but non-syllabic sound is a semivowel. In oral languages, phonetic vowels normally form the peak (nucleus) of many or all syllables, whereas consonants form the onset and (in languages that have them) coda. Some languages allow other sounds to form the nucleus of a syllable, such as the syllabic (i.e., vocalic) l in the English word table [ˈtʰeɪ.bl̩] (when not considered to have a weak vowel sound: [ˈtʰeɪ.bəl]) or the syllabic r in the Serbo-Croatian word vrt [ʋr̩̂t] «garden».

The phonetic definition of «vowel» (i.e. a sound produced with no constriction in the vocal tract) does not always match the phonological definition (i.e. a sound that forms the peak of a syllable).[6] The approximants [j] and [w] illustrate this: both are without much of a constriction in the vocal tract (so phonetically they seem to be vowel-like), but they occur at the onset of syllables (e.g. in «yet» and «wet») which suggests that phonologically they are consonants. A similar debate arises over whether a word like bird in a rhotic dialect has an r-colored vowel /ɝ/ or a syllabic consonant /ɹ̩/. The American linguist Kenneth Pike (1943) suggested the terms «vocoid» for a phonetic vowel and «vowel» for a phonological vowel,[7] so using this terminology, [j] and [w] are classified as vocoids but not vowels. However, Maddieson and Emmory (1985) demonstrated from a range of languages that semivowels are produced with a narrower constriction of the vocal tract than vowels, and so may be considered consonants on that basis.[8] Nonetheless, the phonetic and phonemic definitions would still conflict for the syllabic /l/ in table or the syllabic nasals in button and rhythm.

Articulation[edit]

X-rays of Daniel Jones’ [i, u, a, ɑ].

The original vowel quadrilateral, from Jones’ articulation. The vowel trapezoid of the modern IPA, and at the top of this article, is a simplified rendition of this diagram. The bullets are the cardinal vowel points. (A parallel diagram covers the front and central rounded and back unrounded vowels.) The cells indicate the ranges of articulation that could reasonably be transcribed with those cardinal vowel letters, [i, e, ɛ, a, ɑ, ɔ, o, u, ɨ], and non-cardinal [ə]. If a language distinguishes fewer than these vowel qualities, [e, ɛ] could be merged to ⟨e⟩, [o, ɔ] to ⟨o⟩, [a, ɑ] to ⟨a⟩, etc. If a language distinguishes more, ⟨ɪ⟩ could be added where the ranges of [i, e, ɨ, ə] intersect, ⟨ʊ⟩ where [u, o, ɨ, ə] intersect, and ⟨ɐ⟩ where [ɛ, ɔ, a, ɑ, ə] intersect.

The traditional view of vowel production, reflected for example in the terminology and presentation of the International Phonetic Alphabet, is one of articulatory features that determine a vowel’s quality as distinguishing it from other vowels. Daniel Jones developed the cardinal vowel system to describe vowels in terms of the features of tongue height (vertical dimension), tongue backness (horizontal dimension) and roundedness (lip articulation). These three parameters are indicated in the schematic quadrilateral IPA vowel diagram on the right. There are additional features of vowel quality, such as the velum position (nasality), type of vocal fold vibration (phonation), and tongue root position.

This conception of vowel articulation has been known to be inaccurate since 1928. Peter Ladefoged has said that «early phoneticians… thought they were describing the highest point of the tongue, but they were not. They were actually describing formant frequencies.»[9] (See below.) The IPA Handbook concedes that «the vowel quadrilateral must be regarded as an abstraction and not a direct mapping of tongue position.»[10]

Nonetheless, the concept that vowel qualities are determined primarily by tongue position and lip rounding continues to be used in pedagogy, as it provides an intuitive explanation of how vowels are distinguished.

Height[edit]

Theoretically, vowel height refers to the vertical position of either the tongue or the jaw (depending on the model) relative to either the roof of the mouth or the aperture of the jaw. In practice, however, it refers to the first formant (lowest resonance of the voice), abbreviated F1, which is associated with the height of the tongue. In close vowels, also known as high vowels, such as [i] and [u], the first formant is consistent with the tongue being positioned close to the palate, high in the mouth, whereas in open vowels, also known as low vowels, such as [a], F1 is consistent with the jaw being open and the tongue being positioned low in the mouth. Height is defined by the inverse of the F1 value: the higher the frequency of the first formant, the lower (more open) the vowel.[a] In John Elsing’s usage, where fronted vowels are distinguished in height by the position of the jaw rather than the tongue, only the terms ‘open’ and ‘close’ are used, as ‘high’ and ‘low’ refer to the position of the tongue.

The International Phonetic Alphabet defines seven degrees of vowel height, but no language is known to distinguish all of them without distinguishing another attribute:

- close (high)

- near-close (near-high)

- close-mid (high-mid)

- mid (true-mid)

- open-mid (low-mid)

- near-open (near-low)

- open (low)

The letters [e, ø, ɵ, ɤ, o] are typically used for either close-mid or true-mid vowels. However, if more precision is required, true-mid vowels may be written with a lowering diacritic [e̞, ø̞, ɵ̞, ɤ̞, o̞]. The Kensiu language, spoken in Malaysia and Thailand, is highly unusual in that it contrasts true-mid with close-mid and open-mid vowels, without any difference in other parameters like backness or roundness.

It appears that some varieties of German have five vowel heights that contrast independently of length or other parameters. The Bavarian dialect of Amstetten has thirteen long vowels, which can be analyzed as distinguishing five heights (close, close-mid, mid, open-mid and open) each among the front unrounded, front rounded, and back rounded vowels as well as an open central vowel, for a total of five vowel heights: /i e ɛ̝ ɛ/, /y ø œ̝ œ/, /u o ɔ̝ ɔ/, /ä/. No other language is known to contrast more than four degrees of vowel height.

The parameter of vowel height appears to be the primary cross-linguistic feature of vowels in that all spoken languages that have been researched till now use height as a contrastive feature. No other parameter, even backness or rounding (see below), is used in all languages. Some languages have vertical vowel systems in which at least at a phonemic level, only height is used to distinguish vowels.

Backness[edit]

Idealistic tongue positions of cardinal front vowels with highest point indicated.

Vowel backness is named for the position of the tongue during the articulation of a vowel relative to the back of the mouth. As with vowel height, however, it is defined by a formant of the voice, in this case the second, F2, not by the position of the tongue. In front vowels, such as [i], the frequency of F2 is relatively high, which generally corresponds to a position of the tongue forward in the mouth, whereas in back vowels, such as [u], F2 is low, consistent with the tongue being positioned towards the back of the mouth.

The International Phonetic Alphabet defines five degrees of vowel backness:

- front

- near-front

- central

- near-back

- back

To them may be added front-central and back-central, corresponding to the vertical lines separating central from front and back vowel spaces in several IPA diagrams. However, front-central and back-central may also be used as terms synonymous with near-front and near-back. No language is known to contrast more than three degrees of backness nor is there a language that contrasts front with near-front vowels nor back with near-back ones.

Although some English dialects have vowels at five degrees of backness, there is no known language that distinguishes five degrees of backness without additional differences in height or rounding.

Roundedness[edit]

Roundedness is named after the rounding of the lips in some vowels. Because lip rounding is easily visible, vowels may be commonly identified as rounded based on the articulation of the lips. Acoustically, rounded vowels are identified chiefly by a decrease in F2, although F1 is also slightly decreased.

In most languages, roundedness is a reinforcing feature of mid to high back vowels rather than a distinctive feature. Usually, the higher a back vowel, the more intense is the rounding. However, in some languages, roundedness is independent from backness, such as French and German (with front rounded vowels), most Uralic languages (Estonian has a rounding contrast for /o/ and front vowels), Turkic languages (with a rounding distinction for front vowels and /u/), and Vietnamese with back unrounded vowels.

Nonetheless, even in those languages there is usually some phonetic correlation between rounding and backness: front rounded vowels tend to be more front-central than front, and back unrounded vowels tend to be more back-central than back. Thus, the placement of unrounded vowels to the left of rounded vowels on the IPA vowel chart is reflective of their position in formant space.

Different kinds of labialization are possible. In mid to high rounded back vowels the lips are generally protruded («pursed») outward, a phenomenon known as endolabial rounding because the insides of the lips are visible, whereas in mid to high rounded front vowels the lips are generally «compressed» with the margins of the lips pulled in and drawn towards each other, a phenomenon known as exolabial rounding. However, not all languages follow that pattern. Japanese /u/, for example, is an exolabial (compressed) back vowel, and sounds quite different from an English endolabial /u/. Swedish and Norwegian are the only two known languages in which the feature is contrastive; they have both exo- and endo-labial close front vowels and close central vowels, respectively. In many phonetic treatments, both are considered types of rounding, but some phoneticians do not believe that these are subsets of a single phenomenon and posit instead three independent features of rounded (endolabial), compressed (exolabial), and unrounded. The lip position of unrounded vowels may also be classified separately as spread and neutral (neither rounded nor spread).[12] Others distinguish compressed rounded vowels, in which the corners of the mouth are drawn together, from compressed unrounded vowels, in which the lips are compressed but the corners remain apart as in spread vowels.

Front, raised and retracted[edit]

Front, raised and retracted are the three articulatory dimensions of vowel space. Open and close refer to the jaw, not the tongue.

The conception of the tongue moving in two directions, high–low and front–back, is not supported by articulatory evidence and does not clarify how articulation affects vowel quality. Vowels may instead be characterized by the three directions of movement of the tongue from its neutral position: front (forward), raised (upward and back), and retracted (downward and back). Front vowels ([i, e, ɛ] and, to a lesser extent [ɨ, ɘ, ɜ, æ], etc.), can be secondarily qualified as close or open, as in the traditional conception, but this refers to jaw rather than tongue position. In addition, rather than there being a unitary category of back vowels, the regrouping posits raised vowels, where the body of the tongue approaches the velum ([u, o, ɨ], etc.), and retracted vowels, where the root of the tongue approaches the pharynx ([ɑ, ɔ], etc.):

- front

- raised

- retracted

Membership in these categories is scalar, with the mid-central vowels being marginal to any category.[13]

Nasalization[edit]

Nasalization occurs when air escapes through the nose. Vowels are often nasalised under the influence of neighbouring nasal consonants, as in English hand [hæ̃nd]. Nasalised vowels, however, should not be confused with nasal vowels. The latter refers to vowels that are distinct from their oral counterparts, as in French /ɑ/ vs. /ɑ̃/.[14]

In nasal vowels, the velum is lowered, and some air travels through the nasal cavity as well as the mouth. An oral vowel is a vowel in which all air escapes through the mouth. Polish and Portuguese also contrast nasal and oral vowels.

Phonation[edit]

Voicing describes whether the vocal cords are vibrating during the articulation of a vowel. Most languages have only voiced vowels, but several Native American languages, such as Cheyenne and Totonac, contrast voiced and devoiced vowels. Vowels are devoiced in whispered speech. In Japanese and in Quebec French, vowels that are between voiceless consonants are often devoiced.

Modal voice, creaky voice, and breathy voice (murmured vowels) are phonation types that are used contrastively in some languages. Often, they co-occur with tone or stress distinctions; in the Mon language, vowels pronounced in the high tone are also produced with creaky voice. In such cases, it can be unclear whether it is the tone, the voicing type, or the pairing of the two that is being used for phonemic contrast. The combination of phonetic cues (phonation, tone, stress) is known as register or register complex.

Tenseness[edit]

Tenseness is used to describe the opposition of tense vowels vs. lax vowels. This opposition has traditionally been thought to be a result of greater muscular tension, though phonetic experiments have repeatedly failed to show this.[citation needed]

Unlike the other features of vowel quality, tenseness is only applicable to the few languages that have this opposition (mainly Germanic languages, e.g. English), whereas the vowels of the other languages (e.g. Spanish) cannot be described with respect to tenseness in any meaningful way.[citation needed]

One may distinguish the English tense vs. lax vowels roughly, with its spelling. Tense vowels usually occur in words with the final silent e, as in mate. Lax vowels occur in words without the silent e, such as mat. In American English, lax vowels [ɪ, ʊ, ɛ, ʌ, æ] do not appear in stressed open syllables.[15]

In traditional grammar, long vowels vs. short vowels are more commonly used, compared to tense and lax. The two sets of terms are used interchangeably by some because the features are concomitant in some varieties of English.[clarification needed] In most Germanic languages, lax vowels can only occur in closed syllables. Therefore, they are also known as checked vowels, whereas the tense vowels are called free vowels since they can occur in any kind of syllable.[citation needed]

Tongue root position[edit]

Advanced tongue root (ATR) is a feature common across much of Africa, the Pacific Northwest, and scattered other languages such as Modern Mongolian.[16] The contrast between advanced and retracted tongue root resembles the tense-lax contrast acoustically, but they are articulated differently. Those vowels involve noticeable tension in the vocal tract.

Secondary narrowings in the vocal tract[edit]

Pharyngealized vowels occur in some languages like Sedang and the Tungusic languages. Pharyngealisation is similar in articulation to retracted tongue root but is acoustically distinct.

A stronger degree of pharyngealisation occurs in the Northeast Caucasian languages and the Khoisan languages. They might be called epiglottalized since the primary constriction is at the tip of the epiglottis.

The greatest degree of pharyngealisation is found in the strident vowels of the Khoisan languages, where the larynx is raised, and the pharynx constricted, so that either the epiglottis or the arytenoid cartilages vibrate instead of the vocal cords.

Note that the terms pharyngealized, epiglottalized, strident, and sphincteric are sometimes used interchangeably.

Rhotic vowels[edit]

Rhotic vowels are the «R-colored vowels» of American English and a few other languages.

Reduced vowels[edit]

| Near- front |

Central | Near- back |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Near-close | ᵻ | ᵿ | |

| Mid | ə | ||

| Near-open | ɐ |

Some languages, such as English and Russian, have what are called ‘reduced’, ‘weak’ or ‘obscure’ vowels in some unstressed positions. These do not correspond one-to-one with the vowel sounds that occur in stressed position (so-called ‘full’ vowels), and they tend to be mid-centralized in comparison, as well as having reduced rounding or spreading. The IPA has long provided two letters for obscure vowels, mid ⟨ə⟩ and lower ⟨ɐ⟩, neither of which are defined for rounding. Dialects of English may have up to four phonemic reduced vowels: /ɐ/, /ə/, and higher unrounded /ᵻ/ and rounded /ᵿ/. (The non-IPA letters ⟨ᵻ⟩ and ⟨ᵿ⟩ may be used for the latter to avoid confusion with the clearly defined values of IPA letters like ⟨ɨ⟩ and ⟨ɵ⟩, which are also seen, since the IPA only provides for two reduced vowels.)

Acoustics[edit]

Spectrogram of vowels [i, u, ɑ]. [ɑ] is a low vowel, so its F1 value is higher than that of [i] and [u], which are high vowels. [i] is a front vowel, so its F2 is substantially higher than that of [u] and [ɑ], which are back vowels.

An idealized schematic of vowel space, based on the formants of Daniel Jones and John Wells pronouncing the cardinal vowels of the IPA. The scale is logarithmic. The grey range is where F2 would be less than F1, which by definition is impossible. [a] is an extra-low central vowel. Phonemically it may be front or back, depending on the language. Rounded vowels that are front in tongue position are front-central in formant space, while unrounded vowels that are back in articulation are back-central in formant space. Thus [y ɯ] have perhaps similar F1 and F2 values to the high central vowels [ɨ ʉ]; similarly [ø ɤ] vs central [ɘ ɵ] and [œ ʌ] vs central [ɜ ɞ].

The same chart, with a few intermediate vowels. Low front [æ] is intermediate between [a] and [ɛ], while [ɒ] is intermediate between [ɑ] and [ɔ]. The back vowels change gradually in rounding, from unrounded [ɑ] and slightly rounded [ɒ] to tightly rounded [u]; similarly slightly rounded [œ] to tightly rounded [y]. With [a] seen as an (extra-)low central vowel, the vowels [æ ɐ ɑ] can be redefined as front, central and back (near-)low vowels.

The acoustics of vowels are fairly well understood. The different vowel qualities are realized in acoustic analyses of vowels by the relative values of the formants, acoustic resonances of the vocal tract which show up as dark bands on a spectrogram. The vocal tract acts as a resonant cavity, and the position of the jaw, lips, and tongue affect the parameters of the resonant cavity, resulting in different formant values. The acoustics of vowels can be visualized using spectrograms, which display the acoustic energy at each frequency, and how this changes with time.

The first formant, abbreviated «F1», corresponds to vowel openness (vowel height). Open vowels have high F1 frequencies, while close vowels have low F1 frequencies, as can be seen in the accompanying spectrogram: The [i] and [u] have similar low first formants, whereas [ɑ] has a higher formant.

The second formant, F2, corresponds to vowel frontness. Back vowels have low F2 frequencies, while front vowels have high F2 frequencies. This is very clear in the spectrogram, where the front vowel [i] has a much higher F2 frequency than the other two vowels. However, in open vowels, the high F1 frequency forces a rise in the F2 frequency as well, so an alternative measure of frontness is the difference between the first and second formants. For this reason, some people prefer to plot as F1 vs. F2 – F1. (This dimension is usually called ‘backness’ rather than ‘frontness’, but the term ‘backness’ can be counterintuitive when discussing formants.)

In the third edition of his textbook, Peter Ladefoged recommended using plots of F1 against F2 – F1 to represent vowel quality.[17] However, in the fourth edition, he changed to adopt a simple plot of F1 against F2,[18] and this simple plot of F1 against F2 was maintained for the fifth (and final) edition of the book.[19] Katrina Hayward compares the two types of plots and concludes that plotting of F1 against F2 – F1 «is not very satisfactory because of its effect on the placing of the central vowels»,[20] so she also recommends use of a simple plot of F1 against F2. In fact, this kind of plot of F1 against F2 has been used by analysts to show the quality of the vowels in a wide range of languages, including RP,[21][22] the Queen’s English,[23] American English,[24] Singapore English,[25] Brunei English,[26] North Frisian,[27] Turkish Kabardian,[28] and various indigenous Australian languages.[29]

R-colored vowels are characterized by lowered F3 values.

Rounding is generally realized by a decrease of F2 that tends to reinforce vowel backness. One effect of this is that back vowels are most commonly rounded while front vowels are most commonly unrounded; another is that rounded vowels tend to plot to the right of unrounded vowels in vowel charts. That is, there is a reason for plotting vowel pairs the way they are.

Prosody and intonation[edit]

In addition to variation in vowel quality as described above, vowels vary as a result of differences in prosody. The most important prosodic variables are pitch (fundamental frequency), loudness (intensity) and length (duration). However, the features of prosody are usually considered to apply not to the vowel itself, but to the syllable in which the vowel occurs. In other words, the domain of prosody is the syllable, not the segment (vowel or consonant).[30] We can list briefly the effect of prosody on the vowel component of a syllable.

- Pitch: in the case of a syllable such as ‘cat’, the only voiced portion of the syllable is the vowel, so the vowel carries the pitch information. This may relate to the syllable in which it occurs, or to a larger stretch of speech to which an intonation contour belongs. In a word such as ‘man’, all the segments in the syllable are sonorant and all will participate in any pitch variation.

- Loudness: this variable has been traditionally associated with linguistic stress, though other factors are usually involved in this. Lehiste (ibid) argues that stress, or loudness, could not be associated with a single segment in a syllable independently of the rest of the syllable (p. 147). This means that vowel loudness is a concomitant of the loudness of the syllable in which it occurs.

- Length: it is important to distinguish two aspects of vowel length. One is the phonological difference in length exhibited by some languages. Japanese, Finnish, Hungarian, Arabic and Latin have a two-way phonemic contrast between short and long vowels. The Mixe language has a three-way contrast among short, half-long, and long vowels.[31] The other type of length variation in vowels is non-distinctive, and is the result of prosodic variation in speech: vowels tend to be lengthened when in a stressed syllable, or when utterance rate is slow.

Monophthongs, diphthongs, triphthongs[edit]

A vowel sound whose quality does not change throughout the vowel is called a monophthong. Monophthongs are sometimes called «pure» or «stable» vowels. A vowel sound that glides from one quality to another is called a diphthong, and a vowel sound that glides successively through three qualities is a triphthong.

All languages have monophthongs and many languages have diphthongs, but triphthongs or vowel sounds with even more target qualities are relatively rare cross-linguistically. English has all three types: the vowel sound in hit is a monophthong /ɪ/, the vowel sound in boy is in most dialects a diphthong /ɔɪ/, and the vowel sounds of flower, /aʊər/, form a triphthong or disyllable, depending on the dialect.

In phonology, diphthongs and triphthongs are distinguished from sequences of monophthongs by whether the vowel sound may be analyzed into distinct phonemes. For example, the vowel sounds in a two-syllable pronunciation of the word flower (/ˈflaʊər/) phonetically form a disyllabic triphthong but are phonologically a sequence of a diphthong (represented by the letters ⟨ow⟩) and a monophthong (represented by the letters ⟨er⟩). Some linguists use the terms diphthong and triphthong only in this phonemic sense.

Written vowels[edit]

The name «vowel» is often used for the symbols that represent vowel sounds in a language’s writing system, particularly if the language uses an alphabet. In writing systems based on the Latin alphabet, the letters A, E, I, O, U, Y, W and sometimes others can all be used to represent vowels. However, not all of these letters represent the vowels in all languages that use this writing, or even consistently within one language. Some of them, especially W and Y, are also used to represent approximant consonants. Moreover, a vowel might be represented by a letter usually reserved for consonants, or a combination of letters, particularly where one letter represents several sounds at once, or vice versa; examples from English include igh in «thigh» and x in «x-ray». In addition, extensions of the Latin alphabet have such independent vowel letters as Ä, Ö, Ü, Å, Æ, and Ø.

The phonetic values vary considerably by language, and some languages use I and Y for the consonant [j], e.g., initial I in Italian or Romanian and initial Y in English. In the original Latin alphabet, there was no written distinction between V and U, and the letter represented the approximant [w] and the vowels [u] and [ʊ]. In Modern Welsh, the letter W represents these same sounds. Similarly, in Creek, the letter V stands for [ə]. There is not necessarily a direct one-to-one correspondence between the vowel sounds of a language and the vowel letters. Many languages that use a form of the Latin alphabet have more vowel sounds than can be represented by the standard set of five vowel letters. In English spelling, the five letters A E I O and U can represent a variety of vowel sounds, while the letter Y frequently represents vowels (as in e.g., «gym», «happy«, or the diphthongs in «cry«, «thyme»);[32] W is used in representing some diphthongs (as in «cow«) and to represent a monophthong in the borrowed words «cwm» and «crwth» (sometimes cruth).

Other languages cope with the limitation in the number of Latin vowel letters in similar ways. Many languages make extensive use of combinations of letters to represent various sounds. Other languages use vowel letters with modifications, such as ä in Swedish, or add diacritical marks, like umlauts, to vowels to represent the variety of possible vowel sounds. Some languages have also constructed additional vowel letters by modifying the standard Latin vowels in other ways, such as æ or ø that are found in some of the Scandinavian languages. The International Phonetic Alphabet has a set of 28 symbols representing the range of essential vowel qualities, and a further set of diacritics to denote variations from the basic vowel.

The writing systems used for some languages, such as the Hebrew alphabet and the Arabic alphabet, do not ordinarily mark all the vowels, since they are frequently unnecessary in identifying a word.[citation needed] Technically, these are called abjads rather than alphabets. Although it is possible to construct English sentences that can be understood without written vowels (cn y rd ths?), single words in English lacking written vowels can be indistinguishable; consider dd, which could be any of dad, dada, dado, dead, deed, did, died, diode, dodo, dud, dude, odd, add, and aided. (Note that abjads generally express some word-internal vowels and all word-initial and word-final vowels, whereby the ambiguity will be much reduced.) The Masoretes devised a vowel notation system for Hebrew Jewish scripture that is still widely used, as well as the trope symbols used for its cantillation; both are part of oral tradition and still the basis for many bible translations—Jewish and Christian.

Shifts[edit]

The differences in pronunciation of vowel letters between English and its related languages can be accounted for by the Great Vowel Shift. After printing was introduced to England, and therefore after spelling was more or less standardized, a series of dramatic changes in the pronunciation of the vowel phonemes occurred, and continued into recent centuries, but were not reflected in the spelling system. This has led to numerous inconsistencies in the spelling of English vowel sounds and the pronunciation of English vowel letters (and to the mispronunciation of foreign words and names by speakers of English).

Audio samples[edit]

Systems[edit]

The importance of vowels in distinguishing one word from another varies from language to language. Nearly all languages have at least three phonemic vowels, usually /i/, /a/, /u/ as in Classical Arabic and Inuktitut, though Adyghe and many Sepik languages have a vertical vowel system of /ɨ/, /ə/, /a/. Very few languages have fewer, though some Arrernte, Circassian, and Ndu languages have been argued to have just two, /ə/ and /a/, with [ɨ] being epenthetic.

It is not straightforward to say which language has the most vowels, since that depends on how they are counted. For example, long vowels, nasal vowels, and various phonations may or may not be counted separately; indeed, it may sometimes be unclear if phonation belongs to the vowels or the consonants of a language. If such things are ignored and only vowels with dedicated IPA letters (‘vowel qualities’) are considered, then very few languages have more than ten. The Germanic languages have some of the largest inventories: Standard Danish has 11 to 13 short vowels (/(a) ɑ (ɐ) e ə ɛ i o ɔ u ø œ y/), while the Amstetten dialect of Bavarian has been reported to have thirteen long vowels: /i y e ø ɛ œ æ ɶ a ɒ ɔ o u/.[citation needed] The situation can be quite disparate within a same family language: Spanish and French are two closely related Romance languages but Spanish has only five pure vowel qualities, /a, e, i, o, u/, while classical French has eleven: /a, ɑ, e, ɛ, i, o, ɔ, u, y, œ, ø/ and four nasal vowels /ɑ̃/, /ɛ̃/, /ɔ̃/ and /œ̃/. The Mon–Khmer languages of Southeast Asia also have some large inventories, such as the eleven vowels of Vietnamese: /i e ɛ ɐ a ə ɔ ɤ o ɯ u/. Wu dialects have the largest inventories of Chinese; the Jinhui dialect of Wu has also been reported to have eleven vowels: ten basic vowels, /i y e ø ɛ ɑ ɔ o u ɯ/, plus restricted /ɨ/; this does not count the seven nasal vowels.[33]

One of the most common vowels is [a̠]; it is nearly universal for a language to have at least one open vowel, though most dialects of English have an [æ] and a [ɑ]—and often an [ɒ], all open vowels—but no central [a]. Some Tagalog and Cebuano speakers have [ɐ] rather than [a], and Dhangu Yolngu is described as having /ɪ ɐ ʊ/, without any peripheral vowels. [i] is also extremely common, though Tehuelche has just the vowels /e a o/ with no close vowels. The third vowel of the Arabic-type three-vowel system, /u/, is considerably less common. A large fraction of the languages of North America happen to have a four-vowel system without /u/: /i, e, a, o/; Nahuatl and Navajo are examples.

In most languages, vowels serve mainly to distinguish separate lexemes, rather than different inflectional forms of the same lexeme as they commonly do in the Semitic languages. For example, while English man becomes men in the plural, moon is a completely different word.

Words without vowels[edit]

In rhotic dialects of English, as in Canada and the United States, there are many words such as bird, learn, girl, church, worst, wyrm, myrrh that some phoneticians analyze as having no vowels, only a syllabic consonant /ɹ̩/. However, others analyze these words instead as having a rhotic vowel, /ɝː/. The difference may be partially one of dialect.

There are a few such words that are disyllabic, like cursor, curtain, and turtle: [ˈkɹ̩sɹ̩], [ˈkɹ̩tn̩] and [ˈtɹ̩tl̩] (or [ˈkɝːsɚ], [ˈkɝːtən], and [ˈtɝːtəl]), and even a few that are trisyllabic, at least in some accents, such as purpler [ˈpɹ̩.pl̩.ɹ̩], hurdler [ˈhɹ̩.dl̩.ɹ̩], gurgler [ˈɡɹ̩.ɡl̩.ɹ̩], and certainer [ˈsɹ̩.tn̩.ɹ̩].

The word and frequently contracts to a simple nasal ’n, as in lock ‘n key [ˌlɒk ŋ ˈkiː]. Words such as will, have, and is regularly contract to ’ll [l], ’ve [v], and ‘s [z]. However, none of them are pronounced alone without vowels, so they are not phonological words. Onomatopoeic words that can be pronounced alone, and that have no vowels or ars, include hmm, pst!, shh!, tsk!, and zzz. As in other languages, onomatopoeiae stand outside the normal phonotactics of English.

There are other languages that form lexical words without vowel sounds. In Serbo-Croatian, for example, the consonants [r] and [rː] (the difference is not written) can act as a syllable nucleus and carry rising or falling tone; examples include the tongue-twister na vrh brda vrba mrda and geographic names such as Krk. In Czech and Slovak, either [l] or [r] can stand in for vowels: vlk [vl̩k] «wolf», krk [kr̩k] «neck». A particularly long word without vowels is čtvrthrst, meaning «quarter-handful», with two syllables (one for each R), or scvrnkls, a verb form meaning «you flipped (sth) down» (eg a marble). Whole sentences (usually tongue-twisters) can be made from such words, such as Strč prst skrz krk, meaning «stick a finger through your neck» (pronounced [str̩tʃ pr̩st skr̩s kr̩k] (listen)), and Smrž pln skvrn zvlhl z mlh. (Here zvlhl has two syllables based on L; and note that the preposition z consists of a single consonant. Only prepositions do this in Czech, and they normally link phonetically to the following word, so not really behave as vowelless words.) In Russian, there are also prepositions that consist of a single consonant letter, like k, ‘to’, v, ‘in’, and s, ‘with’. However, these forms are actually contractions of ko, vo, and so respectively, and these forms are still used in modern Russian before words with certain consonant clusters for ease of pronunciation.

In Kazakh and certain other Turkic languages, words without vowel sounds may occur due to reduction of weak vowels. A common example is the Kazakh word for one: bir, pronounced [br]. Among careful speakers, however, the original vowel may be preserved, and the vowels are always preserved in the orthography.

In Southern varieties of Chinese, such as Cantonese and Minnan, some monosyllabic words are made of exclusively nasals, such as Cantonese [m̩˨˩] «no» and [ŋ̩˩˧] «five». Minnan also has words consisting of a consonant followed by a syllabic nasal, such as pn̄g «cooked rice».

So far, all of these syllabic consonants, at least in the lexical words, have been sonorants, such as [r], [l], [m], and [n], which have a voiced quality similar to vowels. (They can carry tone, for example.) However, there are languages with lexical words that not only contain no vowels, but contain no sonorants at all, like (non-lexical) shh! in English. These include some Berber languages and some languages of the American Pacific Northwest, such as Nuxalk. An example from the latter is scs «seal fat» (pronounced [sxs], as spelled), and a longer one is clhp’xwlhtlhplhhskwts’ (pronounced [xɬpʼχʷɬtʰɬpʰɬːskʷʰt͡sʼ]) «he had had in his possession a bunchberry plant». (Follow the Nuxalk link for other examples.) Berber examples include /tkkststt/ «you took it off» and /tfktstt/ «you gave it». Some words may contain one or two consonants only: /ɡ/ «be», /ks/ «feed on».[34] (In Mandarin Chinese, words and syllables such as sī and zhī are sometimes described as being syllabic fricatives and affricates phonemically, /ś/ and /tʂ́/, but these do have a voiced segment that carries the tone.) In the Japonic language Miyako, there are words with no voiced sounds, such as ss ‘dust’, kss ‘breast/milk’, pss ‘day’, ff ‘a comb’, kff ‘to make’, fks ‘to build’, ksks ‘month’, sks ‘to cut’, psks ‘to pull’.

Some analyses of Wandala is reported to have no phonemic vowels.[35]

Words consisting of only vowels[edit]

It is not uncommon for short grammatical words to consist of only vowels, such as a and I in English. Lexical words are somewhat rarer in English and are generally restricted to a single syllable: eye, awe, owe, and in non-rhotic accents air, ore, err. Vowel-only words of more than one syllable are generally foreign loans, such as ai (two syllables: ) for the maned sloth, or proper names, such as Iowa (in some accents: ).

However, vowel sequences in hiatus are more freely allowed in some other languages, most famously perhaps in Bantu and Polynesian languages, but also in Japanese and Finnic languages. In such languages there tends to be a larger variety of vowel-only words. In Swahili (Bantu), for example, there is aua ‘to survey’ and eua ‘to purify’ (both three syllables); in Japanese, aoi 青い ‘blue/green’ and oioi 追々 ‘gradually’ (three and four morae); and in Finnish, aie ‘intention’ and auo ‘open!’ (both two syllables), although some dialects pronounce them as aije and auvo. In Urdu, āye/aaie آئیے or āyn آئیں ‘come’ is used. Hawaiian, and the Polynesian languages generally, have unusually large numbers of such words, such as aeāea (a small green fish), which is three syllables: ae.āe.a. Most long words involve reduplication, which is quite productive in Polynesian: ioio ‘grooves’, eaea ‘breath’, uaua ‘tough’ (all four syllables), auēuē ‘crying’ (five syllables, from uē (uwē) ‘to weep’), uoa or uouoa ‘false mullet’ (sp. fish, three or five syllables).[citation needed]

See also[edit]

- English phonology

- Great Vowel Shift

- Inherent vowel

- List of phonetics topics

- Mater lectionis

- Scale of vowels

- Table of vowels

- Vowel coalescence

- Words without vowels

- Zero consonant

Notes[edit]

- ^ According to Peter Ladefoged, traditional articulatory descriptions such as height and backness «are not entirely satisfactory», and when phoneticians describe a vowel as high or low, they are in fact describing an acoustic quality rather than the actual position of the tongue.[11]

References[edit]

- ^ Ladefoged & Maddieson 1996, p. 281.

- ^ «Vowel». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ^ Dictionary.com: vowel

- ^ Cruttenden, Alan (2014). Gimson’s Pronunciation of English (Eighth ed.). Routledge. p. 27. ISBN 9781444183092.

- ^ Cruttenden, Alan (2014). Gimson’s Pronunciation of English (Eighth ed.). Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 9781444183092.

- ^ Laver, John (1994) Principles of Phonetics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 269.

- ^ Crystal, David (2005) A Dictionary of Linguistics & Phonetics (Fifth Edition), Maldern, MA/Oxford: Blackwell, p. 494.

- ^ Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World’s Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 323. ISBN 978-0-631-19815-4.

- ^ Ladefoged & Disner (2012) Vowels and Consonants, 3rd ed., p. 132.

- ^ IPA (1999) Handbook of the IPA, p. 12.

- ^ Ladefoged, Peter (2006) A Course in Phonetics (Fifth Edition), Boston, MA: Thomson Wadsworth, p. 189.

- ^ IPA (1999), p. 13.

- ^ John Esling (2005) «There Are No Back Vowels: The Laryngeal Articulator Model», The Canadian Journal of Linguistics 50: 13–44

- ^ «Nasals and Nasalization». www.oxfordbibliographies.com. Oxford. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ Ladefoged, Peter & Johnson, Keith. (2011). Tense and Lax Vowels. In A Course in Phonetics (6th ed., pp. 98–100). Boston, MA: Cengage.

- ^ Bessell, Nicola J. (1993). Towards a phonetic and phonological typology of post-velar articulation (Thesis). University of British Columbia.

- ^ Ladefoged, Peter (1993) A Course in Phonetics (Third Edition), Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, p. 197.

- ^ Ladefoged, Peter (2001) A Course in Phonetics (Fourth Edition), Fort Worth: Harcourt, p. 177.

- ^ Ladefoged, Peter (2006) A Course in Phonetics (Fifth Edition), Boston: Thomson Wadsworth, p. 189.

- ^ Hayward, Katrina (2000) Experimental Phonetics, Harlow, UK: Pearson, p. 160.

- ^ Deterding, David (1997). «The formants of monophthong vowels in Standard Southern British English Pronunciation». Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 27 (1–2): 47–55. doi:10.1017/S0025100300005417. S2CID 146157247.

- ^ Hawkins, Sarah and Jonathan Midgley (2005). «Formant frequencies of RP monophthongs in four age groups of speakers». Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 35 (2): 183–199. doi:10.1017/S0025100305002124. S2CID 53532910.

- ^ Harrington, Jonathan, Sallyanne Palethorpe and Catherine Watson (2005) Deepening or lessening the divide between diphthongs: an analysis of the Queen’s annual Christmas broadcasts. In William J. Hardcastle and Janet Mackenzie Beck (eds.) A Figure of Speech: A Festschrift for John Laver, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 227-261.

- ^ Flemming, Edward and Stephanie Johnson (2007). «Rosa’s roses: reduced vowels in American English» (PDF). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 37: 83–96. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.536.1989. doi:10.1017/S0025100306002817. S2CID 145535175.

- ^ Deterding, David (2003). «An instrumental study of the monophthong vowels of Singapore English». English World-Wide. 24: 1–16. doi:10.1075/eww.24.1.02det.

- ^ Salbrina, Sharbawi (2006). «The vowels of Brunei English: an acoustic investigation». English World-Wide. 27 (3): 247–264. doi:10.1075/eww.27.3.03sha.

- ^ Bohn, Ocke-Schwen (2004). «How to organize a fairly large vowel inventory: the vowels of Fering (North Frisian)» (PDF). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 34 (2): 161–173. doi:10.1017/S002510030400180X. S2CID 59404078.

- ^ Gordon, Matthew and Ayla Applebaum (2006). «Phonetic structures of Turkish Kabardian» (PDF). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 36 (2): 159–186. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.233.1206. doi:10.1017/S0025100306002532. S2CID 6665600.

- ^ Fletcher, Janet (2006) Exploring the phonetics of spoken narratives in Australian indigenous languages. In William J. Hardcastle and Janet Mackenzie Beck (eds.) A Figure of Speech: A Festschrift for John Laver, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 201–226.

- ^ Lehiste, Ilse, Suprasegmentals, M.I.T 1970, pp. 42, 84, 147

- ^ Ladefoged, P. and Maddieson, I. The Sounds of the World’s Languages, Blackwell (1996), p 320

- ^ In wyrm and myrrh, there is neither a vowel letter nor, in rhotic dialects, a vowel sound.

- ^ Values in open oral syllables Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Audio recordings of selected words without vowels can be downloaded from «Archived copy». Archived from the original on 2009-03-20. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). - ^ Wolff, H. Ekkehard. «‘Vocalogenesis’ in (Central) Chadic languages» (PDF). Retrieved 2 December 2017.

Bibliography[edit]

- Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, 1999. Cambridge University ISBN 978-0-521-63751-0

- Johnson, Keith, Acoustic & Auditory Phonetics, second edition, 2003. Blackwell ISBN 978-1-4051-0123-3

- Korhonen, Mikko. Koltansaamen opas, 1973. Castreanum ISBN 978-951-45-0189-0

- Ladefoged, Peter, A Course in Phonetics, fifth edition, 2006. Boston, MA: Thomson Wadsworth ISBN 978-1-4130-2079-3

- Ladefoged, Peter, Elements of Acoustic Phonetics, 1995. University of Chicago ISBN 978-0-226-46764-1

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World’s Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19815-4.

- Ladefoged, Peter, Vowels and Consonants: An Introduction to the Sounds of Languages, 2000. Blackwell ISBN 978-0-631-21412-0.

- Lindau, Mona. (1978). «Vowel features». Language. 54 (3): 541–563. doi:10.2307/412786. JSTOR 412786.

- Stevens, Kenneth N. (1998). Acoustic phonetics. Current studies in linguistics (No. 30). Cambridge, MA: MIT. ISBN 978-0-262-19404-4.

- Stevens, Kenneth N. (2000). «Toward a model for lexical access based on acoustic landmarks and distinctive features». The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 111 (4): 1872–1891. doi:10.1121/1.1458026. PMID 12002871. S2CID 1811670.

- Watt, D. and Tillotson, J. (2001). A spectrographic analysis of vowel fronting in Bradford English. English World-Wide 22:2, 269–302. Available at https://web.archive.org/web/20120412023624/http://www.abdn.ac.uk/langling/resources/Watt-Tillotson2001.pdf

External links[edit]

This audio file was created from a revision of this article dated 18 July 2005, and does not reflect subsequent edits.

Look up vowel in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vowels.

- IPA chart with MP3 sound files

- IPA vowel chart with AIFF sound files

- Vowel charts for several different languages and dialects measuring F1 and F2[failed verification]

- Materials for measuring and plotting vowel formants Archived 2019-09-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Vowels and Consonants Archived 2005-07-03 at the Wayback Machine Online examples from Ladefoged’s Vowels and Consonants, referenced above.

Do you want to know how new words are made? Today we will explore one way of forming new words — derivation.

We will explain the meaning of derivation in English grammar and how derivatives are formed. We will also look at some examples and the difference between derivation, zero derivation, and inflection.

Derivation in English grammar

In English grammar, derivation refers to the creation of a new word from an existing one by adding affixes to the root. Affixes can be broken down into prefixes and suffixes.

Prefixes = placed at the beginning of a word, e.g. the ‘un’ in ‘unhappy’ is a prefix.

Suffixes = placed at the end of a word, e.g. the ‘ly’ in ‘finally’ is a suffix.

Derivation is a type of neologism which refers to creating and using new words.

In case you forgot: The root of a word is the base part (without any affixes added), e.g. the root of the word ‘untrue’ is ‘true’.

Think of the root of a word as the trunk of a tree. The added affixes are the leaves that grow from the branches.

Derivation word formation

Derivatives can be formed in two different ways:

- Adding a prefix to the root of an existing word.

- Adding a suffix to the root of an existing word.

Derivations follow different patterns depending on what is added. When a word is formed by adding a suffix, the word form changes and the word class (e.g. nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.) is usually changed — though not always. Below are some examples of different suffixes and how they can change the word class:

Suffixes

Suffixes can be added to an adjective to form different word classes:

Weak (adjective) ⇨ Weakness (noun)

Short (adjective) ⇨ Shorten (verb)

Polite (adjective) ⇨ Politely (adverb)

Sometimes, suffixes can be added to an adjective without changing the word class. For example:

Pink (adjective) ⇨ Pinkish (adjective).

Suffixes can be added to a noun to form different word classes:

Tradition (noun) ⇨ Traditional (adjective)

Motive (noun) ⇨ Motivate (verb)

Sometimes, suffixes can be added to a noun without changing the word class — for example:

Friend (noun) ⇨ Friendship (noun)

They can also be added to a verb to form different word classes:

Prefixes

When a prefix is added to a word, the word form changes. However, the word class usually remains the same. For example:

Derivation example sentence

It is important to know how to use ‘derivation’ in a sentence. For example:

The process of creating a word by adding affixes is known as derivation.