This material provides general information about English pronouns. As pronouns usually present some difficulty for learners of English, a look at the whole group of pronouns may help to see the general picture more clearly when you are studying separate pronouns or small groups of pronouns.

Brief description of English pronouns and nouns, with examples of use, is provided in Brief Overview of Grammar in the section Grammar.

Classes of pronouns

English pronouns are a miscellaneous (but not very large) group. By type, pronouns are usually divided into the following groups:

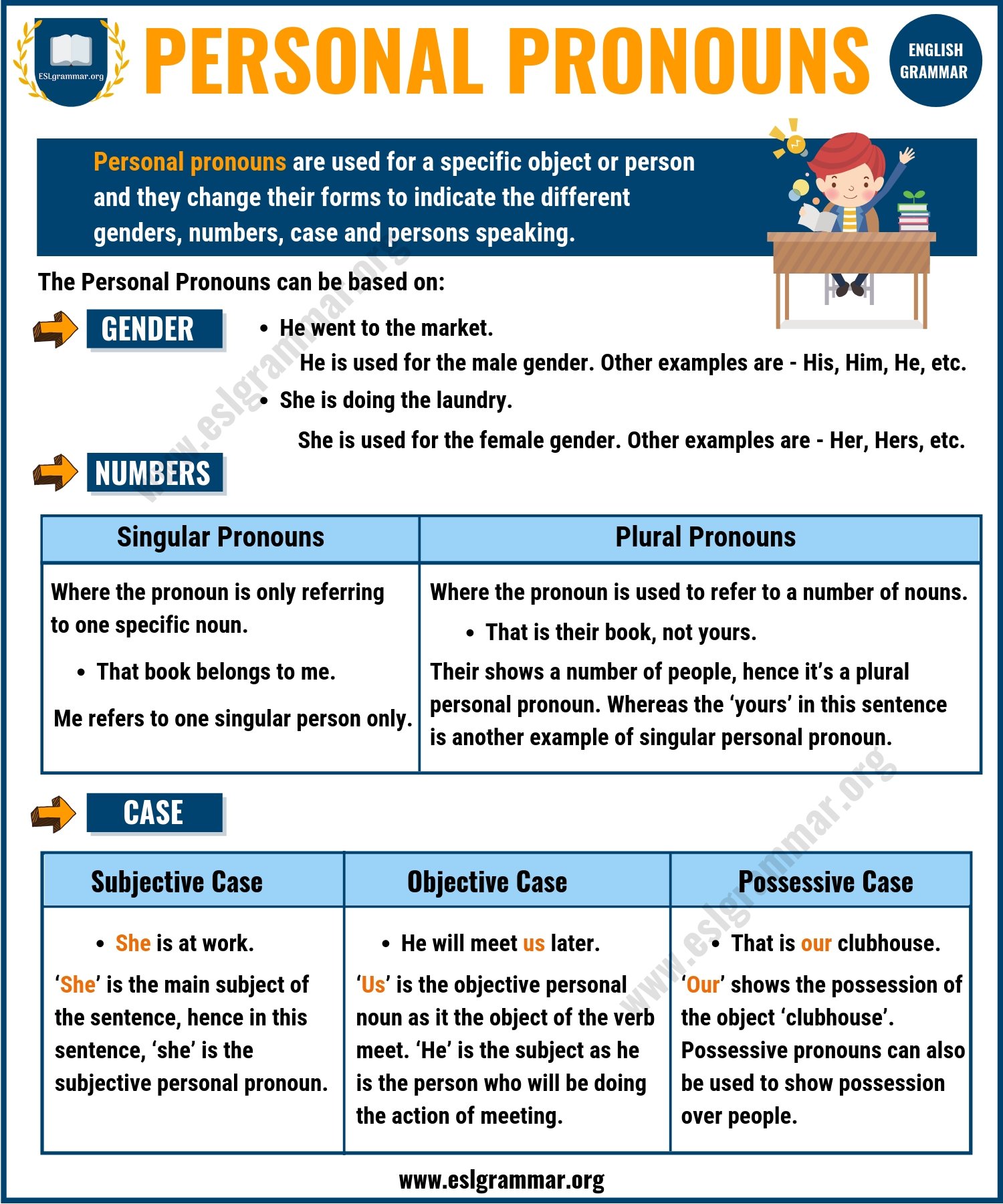

Personal pronouns: I, he, she, it, we, you, they. The forms of personal pronouns in the objective case: me, him, her, it, us, you, them.

Possessive pronouns: my, his, her, its, our, your, their. Absolute forms of possessive pronouns: mine, his, hers, its, ours, yours, theirs.

Reflexive pronouns: myself, yourself, himself, herself, itself, ourselves, yourselves, themselves; oneself.

Intensive pronouns / Emphatic pronouns: myself, yourself, himself, herself, itself, ourselves, yourselves, themselves.

Demonstrative pronouns: this, that, these, those.

Interrogative pronouns: who (whom, whose), what, which. The forms of «who»: in the objective case, «whom»; in the possessive case, «whose».

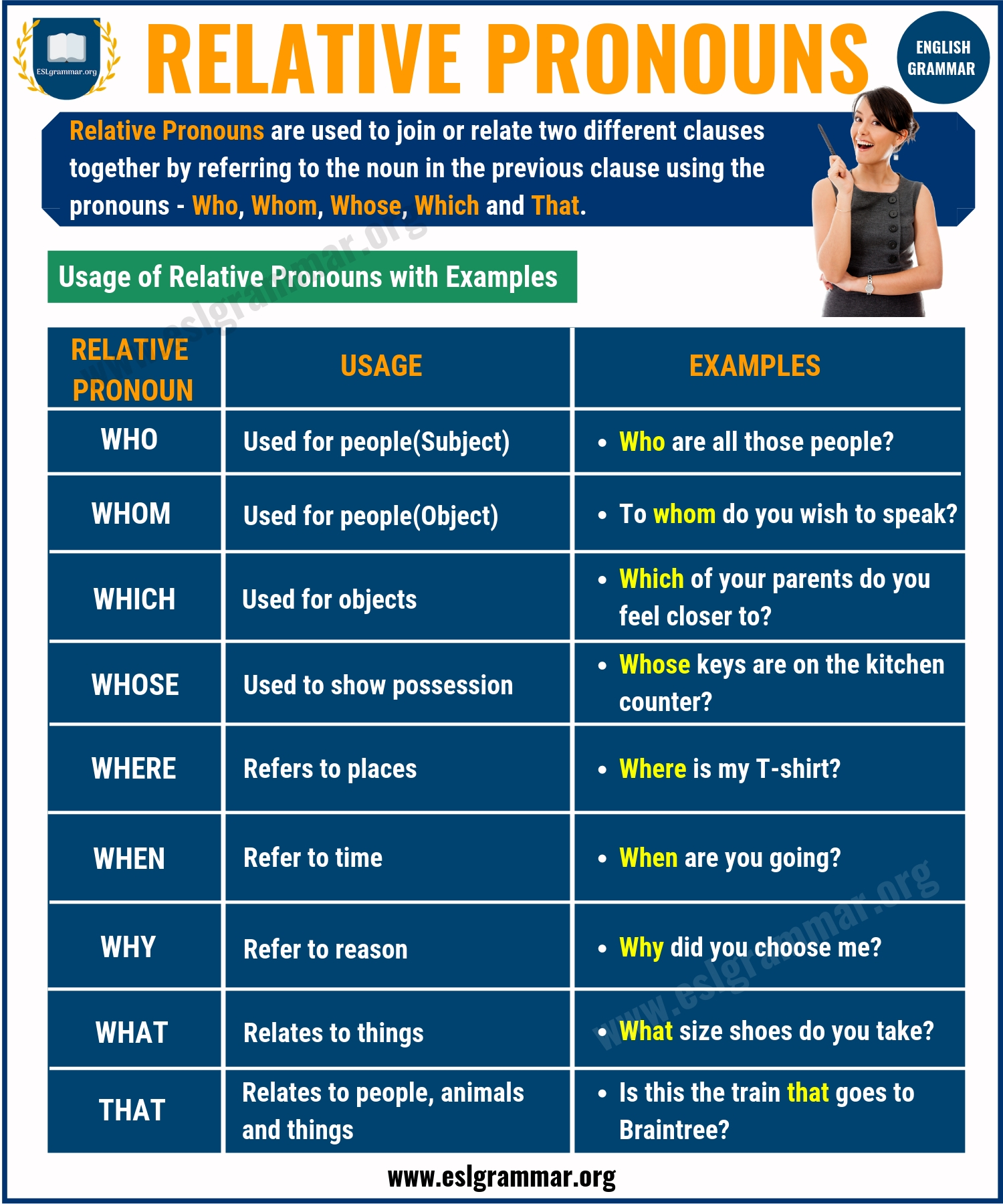

Relative pronouns: who (whom, whose), what, which, that. Compound relative pronouns: whoever (whomever), whatever, whichever.

Reciprocal pronouns: each other, one another.

Indefinite pronouns: some, any, no; somebody, someone, anybody, anyone, nobody, no one; something, anything, nothing; one, none; each, every, other, another, both, either, neither; all, many, much, most, little, few, several; everybody, everyone, everything; same, such.

Note:

Possessive and reflexive pronouns are often regarded as subgroups of personal pronouns in English linguistic materials.

Intensive pronouns (I’ll do it myself) have the same form as reflexive pronouns (Don’t hurt yourself) and are often listed as a subgroup of reflexive pronouns.

Accordingly, pronouns are usually divided into six classes in English sources: personal, demonstrative, interrogative, relative, reciprocal, and indefinite.

Some linguists subdivide the group of indefinite pronouns; for example, the pronouns «each, every, either, neither» are included in the group of distributive pronouns; the pronouns «many, much, few, several» are included in the group of quantitative pronouns.

The pronoun «it» is regarded by some linguists not only as a personal pronoun but also as a demonstrative pronoun.

The pronoun «such» is regarded as an indefinite pronoun or as a demonstrative pronoun in different sources.

Some linguists view «little» and «much» as adjectives, nouns and adverbs, but not as pronouns.

Noun pronouns and adjective pronouns

Some pronouns can function as nouns or adjectives. For example, in «This is my house», the pronoun «this» is the subject (i.e., «this» is used as a noun), and in «This house is mine», the pronoun «this» is an attribute (i.e., «this» is used as an adjective).

Noun pronouns have some (limited, not full) properties of nouns; they are used instead of nouns and function as subjects or objects. For example:

They are new. Don’t lose them.

Everyone is here. He invited everyone.

Adjective pronouns have some properties of adjectives; they modify nouns and function as attributes. For example:

Both sisters are doctors.

Give me another book.

I don’t have much time.

We have very little money left.

Like nouns and adjectives, some pronouns can be used in the predicative after the verb «be». For example:

This is she. That’s all. This pen is yours.

Unlike nouns, noun pronouns are generally not used with a preceding adjective, except the pronoun «one».

I need a computer table. This is a good one.

Where are the little ones?

Unlike nouns, noun pronouns are rarely used with an article, except the pronouns «same, other, few, one».

The same can be said about you.

There were good pens there. I bought a few.

The one I saw was reddish brown.

Where are the others?

Unlike adjectives, adjective pronouns do not have degrees of comparison. Only the pronouns «many, much, few, little» have degrees of comparison.

You have more time than I do.

He should eat less meat and more vegetables.

There were fewer people in the park than I expected.

Note: English and Russian terms

Since a pronoun in English is usually defined as «a word that functions as a noun substitute; a word used as a substitute for a noun; a word used instead of a noun to avoid repetition», pronouns in the function of nouns are called «pronouns» in English linguistic sources.

The term «noun pronoun» is not used in English linguistic sources. But «noun pronoun» is often used in Russian materials on English grammar in order to show the differences between the functions of pronouns as nouns and as adjectives.

Pronouns in the function of adjectives are called «pronominal adjectives; adjective pronouns; determiners» and sometimes simply «adjectives» in English linguistic sources.

The noun (or its equivalent) to which a pronoun refers is called «antecedent». For example, in the sentence «I know the people who live there», the noun «people» is the antecedent of the pronoun «who».

In the sentence «Maria received a letter, and she is reading it now», the noun «Maria» is the antecedent of the pronoun «she», and the noun «letter» is the antecedent of the pronoun «it».

A short list of noun pronouns and adjective pronouns

The possessive pronouns «my, his, her, its, our, your, their» are always used in the function of adjectives (my book; his bag).

Absolute forms «mine, his, hers, its, ours, yours, theirs» can be used as predicative adjectives (this book is not mine) or as nouns (mine was new).

The interrogative and relative pronouns «who, whom» are used as nouns: Who can do it? Find those who saw it. To whom am I speaking?

The pronoun «whose» is used as an adjective: Whose book is this? Whose books did you take? I know the boy whose books you took.

The interrogative and relative pronouns «what, which» can be used as nouns or adjectives: What is it? What color is your bag? The letters which have been written earlier are on the table. He didn’t answer, which was strange. Which bag is yours?

The indefinite pronouns «some, any, each, other, another, one, both, either, neither, all, many, much, most, little, few, several» can be used as nouns (few of us; some of them; he bought some) and as adjectives (few people; some books; he bought some meat).

The pronouns «no one, none» are used in the function of nouns (no one saw him; none of them). The pronouns «no, every» are used in the function of adjectives (no books; every word).

Combinations and set expressions

Some pronouns can combine, forming pronoun combinations used as nouns or as adjectives. For example:

I like this one. Some others left early. They know each other.

Give me some other books. They looked into each other’s eyes.

Pronouns are used in a large number of set expressions. For example:

a good many; all for nothing; all or nothing; each and all; each and every; every other; little by little; little or nothing; no less than; no more than; it leaves much to be desired;

one and all; one by one; something or other; some way or other; that’s all; that’s it; that’s something; and that’s that; this and that; this is it; what is what; who is who.

The pronoun and its noun

The noun (or its equivalent, e.g., a noun phrase or another pronoun) to which a pronoun refers helps to understand the meaning of the pronoun.

In the case of personal or relative pronouns, it is usually necessary to use the noun earlier than the replacing pronoun. For example:

The woman who had lost her purse in the park found it today under the bench on which she had been sitting.

In this example, the pronouns «who, her, she» refer to the noun «woman»; the pronoun «it» replaces the noun «purse»; the pronoun «which» is used instead of the noun «bench». Without the preceding nouns, the pronouns in this sentence would not be fully clear.

But in some cases the preceding noun is not needed. For example, the personal pronoun «I» (i.e., the speaker) is usually clear from the situation. The relative noun pronoun «what» does not need any preceding noun either: I will do what I promised.

Indefinite noun pronouns like «some, any, most» usually need a preceding noun in order to make their meaning clear.

These plums are very good. Do you want some?

This cake is delicious. Do you want some?

If the noun to which a noun pronoun like «some, any, most» refers is specific (e.g., a certain group of people or things or a specific amount of something), the phrase «of» + noun is placed after the pronoun.

Most of his friends live nearby.

Tanya spends most of her free time reading detective stories.

Most of his money was stolen. Most of it was stolen.

Some other indefinite pronouns (e.g., somebody, anybody, something) do not need any noun because their meaning is general.

Nobody knows about it. Has anyone called?

Let’s eat something. Everything is ready.

Forms and properties of personal pronouns

A personal pronoun agrees with its noun in gender, person, and number. If a personal pronoun is the subject of a sentence, the verb (the predicate) agrees with the pronoun in person and number.

Let’s look at the forms of the personal pronouns in these examples:

Anton is in his room. He is reading an interesting book. He likes it very much.

His younger sister is playing with her new dolls. She likes them very much.

In these examples, the personal pronouns «he» and «she» refer to the subjects expressed by the singular nouns «Anton» and «sister». Like their nouns, the third-person singular pronouns «he» (masculine) and «she» (feminine) are in the nominative case.

The forms «his» and «her» are in the possessive case; they agree with «Anton, he» and «sister, she» in gender (masculine, feminine), person (third person), and number (singular).

The pronouns «it» (third person singular, neuter gender) and «them» (third person plural) refer to the objects expressed by the inanimate nouns «book» (singular) and «dolls» (plural); as objects, the pronouns «it» and «them» are in the objective case.

The subjects «he» and «she» are in the third person singular; accordingly, their verbs are also used in the third person singular (is, likes).

Only personal pronouns have enough forms to express, more or less fully, gender, person, number, and case in their forms.

Forms and properties of other pronouns

The other pronouns do not have enough forms to express gender, person, number, or case. That is, some of them have some grammatical forms.

The demonstrative pronouns «this, that» have the plural forms «these, those».

This is my book. These are my books.

These books are interesting. Those books are not very interesting.

The relative pronoun «who» has the form «whom» in the objective case and the form «whose» in the possessive case.

The co-workers with whom she discussed her plan agreed to help her.

The student whose bicycle was stolen went home by bus.

The indefinite pronouns «anybody, anyone, everybody, everyone, somebody, someone, nobody, no one, one» can be used in the possessive case.

There is somebody’s bag on my table.

It was no one’s fault.

But most of the indefinite pronouns do not have any forms to express gender, person, number, or case; they always remain in the same form. Nevertheless, they can express grammatical meaning through their lexical meaning and through their function in the sentence.

For example, the pronouns «anybody, no one, who» refer to people, not to things (No one came to his party); «all, some, any, many, few, no, none» refer to people or things (neither of the boys; neither of the books); the pronouns «each other» and «one another» are not used as subjects (Mike and Maria love each other).

Agreement in number

Indefinite pronouns express number in their lexical meaning, which determines whether a singular or plural verb should be used when an indefinite pronoun is the subject.

The pronouns «anybody, anyone, anything, everybody, everyone, everything, somebody, someone, something, nobody, no one, nothing, one, each, either, neither, much» are used with a singular verb.

Everyone is waiting.

There is nothing left.

Each of the boxes was empty.

The pronouns «both, few, many, others, several» are used with a plural verb.

Both of them are here.

Few of them know it.

Many (of them) were broken.

The pronouns «all, any, most, none, some» take a singular or plural verb depending on what the pronoun refers to: to an amount / portion of something or to several persons or things.

All of this food has been prepared by our friends. All of it is delicious.

All his friends are here. All of them are here.

The interrogative pronouns «who, what» in the function of the subject are used with a singular verb if the predicate is expressed by a main verb.

Who knows his address? What has happened?

In the case of the compound nominal predicate with the linking verb «be», the verb «be» agrees in number with the noun (or pronoun) to which «who» or «what» refers.

Who is that man? Who are they?

What is your name? What are your plans?

In sentences with a relative pronoun «who», the verb agrees in number with the noun to which «who» refers.

I know the boy who is standing by the window.

I know the boys who are standing by the window.

Difficulties

As you have probably understood from the material above, the variety of pronouns and the differences between them may present serious problems for learners of English.

Similar pronouns, such as «some» and «any», «each» and «every», «which» and «that», «it» and «this», present considerable difficulty; they differ in use, and each of them has its own peculiarities. (Some of the differences have been described in answers to your questions in the subsection Messages about Grammar (Pronouns) in the section Messages.)

Agreement of pronouns with their nouns and agreement of the predicate with the subject expressed by an indefinite pronoun usually present the most difficulty. In some cases, the only way to avoid problems with agreement is to restructure the sentence.

Problems of gender

The majority of English animate nouns do not express gender either in form or in meaning. As a result, it is not always clear whether to use «he» or «she» (and their forms «his, him, her») with such nouns in the singular. For example:

I want to speak to the designer. Where can I find him? (him? her?)

Similar (and more difficult) problems occur when the indefinite pronouns «somebody, nobody, anyone, everyone, each», which may refer to male and female persons, are used as subjects. In formal English, «he, his, him» are used (if necessary) with these indefinite pronouns; «they, their, them» (and «our») are often used with these pronouns in informal English.

Compare the use of English pronouns in formal and informal style and the use of equivalent pronouns in Russian sentences.

Formal style: Nobody offered his help. Everyone brought his own lunch. Each of us has his own reasons.

Informal style: Nobody offered their help. Everyone brought their own lunch. Each of us has our own reasons.

Problems of number

Problems with agreement in number usually occur if you forget which indefinite pronouns require a singular verb, and which of them require a plural verb. (See the part «Agreement in number» above.)

Agreement of the verb with two pronouns in the subject may also cause some difficulty. For example, the subject expressed by two personal pronouns connected by the conjunction «and» takes the verb in the plural form. If the pronouns are connected by «or; either…or; neither…nor», the verb agrees in number with the nearest pronoun. Compare:

You and he have to be there by ten.

Either you or he has to be there by ten.

General recommendations

Study the rules of the use of pronouns together with various examples of their use. Choose simple, typical examples and use them in your speech and writing. Avoid using complicated or disputable cases.

Helpful related materials

Personal, possessive and reflexive pronouns, with many examples of use, are described in Personal Pronouns and Personal Pronouns in Examples in the section Miscellany.

Agreement of nouns and verbs in number, agreement of indefinite pronouns and verbs in number, and agreement of possessive pronouns with nouns and with indefinite pronouns are described in Agreement in the section Grammar.

The use of relative pronouns in relative clauses is described briefly in Word Order in Complex Sentences in the section Grammar.

Examples illustrating the use of interrogative pronouns (and of other question words) can be found in Word Order in Questions in the section Grammar.

Типы местоимений

Данный материал даёт общую информацию об английских местоимениях. Поскольку местоимения обычно представляют трудность для изучающих английский язык, взгляд на местоимения как на группу целиком может помочь увидеть общую картину более ясно, когда вы изучаете отдельные местоимения или небольшие группы местоимений.

Краткое описание английских местоимений и существительных, с примерами употребления, дано в статье Brief Overview of Grammar в разделе Grammar.

Классы местоимений

Английские местоимения – это разнородная (но не очень большая) группа. По типу, местоимения обычно делятся на следующие группы:

Личные местоимения: I, he, she, it, we, you, they. Формы личных местоимений в косвенном падеже: me, him, her, it, us, you, them.

Притяжательные местоимения: my, his, her, its, our, your, their. Абсолютные формы притяжательных местоимений: mine, his, hers, its, ours, yours, theirs.

Возвратные местоимения: myself, yourself, himself, herself, itself, ourselves, yourselves, themselves; oneself.

Усилительные местоимения: myself, yourself, himself, herself, itself, ourselves, yourselves, themselves.

Указательные местоимения: this, that, these, those.

Вопросительные местоимения: who (whom, whose), what, which. Формы «who»: в косвенном падеже, «whom»; в притяжательном падеже, «whose».

Относительные местоимения: who (whom, whose), what, which, that. Сложные формы относительных местоимений: whoever (whomever), whatever, whichever.

Взаимные местоимения: each other, one another.

Неопределённые местоимения: some, any, no; somebody, someone, anybody, anyone, nobody, no one; something, anything, nothing; one, none; each, every, other, another, both, either, neither; all, many, much, most, little, few, several; everybody, everyone, everything; same, such.

Примечание:

Притяжательные и возвратные местоимения часто рассматриваются как подгруппы личных местоимений в английских лингвистических материалах.

Усилительные местоимения (I’ll do it myself) имеют такую же форму как возвратные местоимения (Don’t hurt yourself) и часто даются как подгруппа возвратных местоимений.

Соответственно, местоимения обычно делятся на шесть классов в английских источниках: личные, указательные, вопросительные, относительные, взаимные и неопределённые.

Некоторые лингвисты подразделяют группу неопределённых местоимений; например, местоимения «each, every, either, neither» включаются в группу дистрибутивных местоимений; местоимения «many, much, few, several» включаются в группу количественных местоимений.

Местоимение «it» рассматривается некоторыми лингвистами не только как личное местоимение, но и как указательное местоимение.

Местоимение «such» рассматривается как неопределённое местоимение или как указательное местоимение в разных источниках.

Некоторые лингвисты рассматривают «little» и «much» как прилагательные, существительные и наречия, но не как местоимения.

Местоимения-существительные и местоимения-прилагательные

Некоторые местоимения могут функционировать как существительные или прилагательные. Например, в «This is my house» местоимение «this» – подлежащее (т.е. «this» употреблено как существительное), а в «This house is mine» местоимение «this» – определение (т.е. «this» употреблено как прилагательное).

Местоимения-существительные имеют некоторые (ограниченные, неполные) свойства существительных; они употребляются вместо существительных и функционируют как подлежащие или дополнения. Например:

Они новые. Не потеряй их.

Все здесь. Он пригласил всех.

Местоимения-прилагательные имеют некоторые свойства прилагательных; они определяют существительное и функционируют как определения. Например:

Обе сестры – врачи.

Дайте мне другую книгу.

У меня мало времени.

У нас осталось очень мало денег.

Так же, как существительные и прилагательные, некоторые местоимения могут употребляться в именной части сказуемого после глагола «be». Например:

Это она. Это всё. Эта ручка ваша.

В отличие от существительных, местоимения-существительные обычно не употребляются с предшествующим прилагательным, за исключением местоимения «one».

Мне нужен компьютерный стол. Этот хороший.

Где малыши? (т.е. детки)

В отличие от существительных, местоимения-существительные редко употребляются с артиклем, за исключением местоимений «same, other, few, one».

То же самое можно сказать о вас.

Там были хорошие ручки. Я купил несколько.

Тот, который я видел, был красновато-коричневый.

Где другие? (Где остальные?)

В отличие от прилагательных, местоимения-прилагательные не имеют степеней сравнения. Только местоимения «many, much, few, little» имеют степени сравнения.

У тебя больше времени, чем у меня.

Ему следует есть меньше мяса и больше овощей.

В парке было меньше людей, чем я ожидал.

Примечание: Английские и русские термины

Поскольку местоимение в английском языке обычно определяется как «слово, которое функционирует как заменитель существительного; слово, используемое как заменитель для существительного; слово, используемое вместо существительного во избежание повторения», местоимения в функции существительных называются «pronouns» в английских лингвистических источниках.

Термин «noun pronoun» не употребляется в английских лингвистических источниках. Но «noun pronoun» (местоимение-существительное) часто употребляется в русских материалах по английской грамматике, чтобы показать различия между функциями местоимений как существительных и как прилагательных.

Местоимения в функции прилагательных называются «pronominal adjectives; adjective pronouns; determiners» (местоименные прилагательные; определяющие слова), а иногда просто «adjectives» в английских лингвистических источниках.

Существительное (или его эквивалент), к которому относится местоимение, называется «antecedent» (предшествующее существительное). Например, в предложении «I know the people who live there», существительное «people» – антецедент местоимения «who».

В предложении «Maria received a letter, and she is reading it now», существительное «Maria» – антецедент местоимения «she», а существительное «letter» – антецедент местоимения «it».

Краткий список местоимений-существительных и местоимений-прилагательных

Притяжательные местоимения «my, his, her, its, our, your, their» всегда употребляются в функции прилагательных (my book; his bag).

Абсолютные формы «mine, his, hers, its, ours, yours, theirs» могут употребляться как предикативные прилагательные (эта книга не моя) или как существительные (моя была новая).

Вопросительные и относительные местоимения «who, whom» употребляются как существительные: Кто может сделать это? Найдите тех, кто видел это. С кем я говорю?

Местоимение «whose» употребляется как прилагательное: Чья это книга? Чьи книги вы взяли? Я знаю мальчика, книги которого вы взяли.

Вопросительные и относительные местоимения «what, which» могут употребляться как существительные или прилагательные: Что это? Какого цвета ваша сумка? Письма, которые были написаны раньше, находятся на столе. Он не ответил, что было странно. Которая сумка ваша?

Неопределённые местоимения «some, any, each, other, another, one, both, either, neither, all, many, much, most, little, few, several» могут употребляться как существительные (немногие из нас; некоторые из них; он купил немного) и как прилагательные (немногие люди; некоторые книги; он купил немного мяса).

Местоимения «no one, none» употребляются в функции существительных (никто не видел его; никто из них). Местоимения «no, every» употребляются в функции прилагательных (никакие книги; каждое слово).

Сочетания и устойчивые выражения

Некоторые местоимения могут соединяться, образуя сочетания местоимений, используемые как существительные или как прилагательных. Например:

Мне нравится этот. Некоторые другие ушли рано. Они знают друг друга.

Дайте мне какие-нибудь другие книги. Они посмотрели друг другу в глаза.

Местоимения употребляются в большом количестве устойчивых выражений. Например:

многие; всё зря / всё напрасно; всё или ничего; все без исключения; все до единого; каждый второй; постепенно; почти ничего; не менее чем; не более чем; это оставляет желать много лучшего;

все до единого; один за другим; то или другое; тем или иным способом; это всё; это всё / это как раз то; это уже кое-что; и на этом точка; то да сё / то или другое; это как раз то / это всё; что есть что; кто есть кто.

Местоимение и его существительное

Существительное (или его эквивалент, например, словосочетание или другое местоимение), к которому относится местоимение, помогает понять значение местоимения.

В случае личных и относительных местоимений, обычно необходимо употребить существительное раньше, чем заменяющее местоимение. Например:

Женщина, которая потеряла свой кошелёк в парке, нашла его сегодня под скамейкой, на которой она сидела.

В этом примере, местоимения «who, her, she» относятся к существительному «woman»; местоимение «it» заменяет существительное «purse»; местоимение «which» употреблено вместо существительного «bench». Без предшествующих существительных, местоимения в этом предложении не были бы полностью ясными.

Но в некоторых случаях предшествующее существительное не требуется. Например, личное местоимение «I» (т.е. говорящий) обычно ясно из ситуации. Относительное местоимение-существительное «what» также не нуждается в предшествующем существительном: Я сделаю (то), что я обещал.

Неопределённые местоимения-существительные типа «some, any, most» обычно нуждаются в предшествующем существительном, чтобы сделать их значение ясным.

Эти сливы очень хорошие. Хотите несколько?

Этот торт очень вкусный. Хотите немного?

Если существительное, к которому относится местоимение-существительное типа «some, any, most» является определённым (например, определённая группа людей или определённое количество чего-то), фраза «of» + существительное ставится после местоимения.

Многие из его друзей живут поблизости.

Таня проводит большую часть своего свободного времени, читая детективные рассказы.

Большая часть его денег была украдена. Большая часть (денег) была украдена.

Некоторые другие неопределённые местоимения (например, somebody, anybody, something) не нуждаются в существительном, т.к. их значение обобщённое.

Никто не знает об этом. Кто-нибудь звонил?

Давайте поедим чего-нибудь. Всё готово.

Формы и свойства личных местоимений

Личное местоимение согласуется со своим существительным в роде, лице и числе. Если личное местоимение является подлежащим, глагол (сказуемое) согласуется с местоимением в лице и числе.

Давайте посмотрим на формы личных местоимений в этих примерах:

Антон в своей комнате. Он читает интересную книгу. Она ему очень нравится.

Его младшая сестра играет со своими новыми куклами. Они ей очень нравятся.

В этих примерах, личные местоимения «he» и «she» относятся к подлежащим, выраженным существительными в ед. числе «Anton» и «sister». Как и их существительные, местоимения 3-го лица ед. числа «he» (муж. род) и «she» (жен. род) стоят в именительном падеже.

Формы «his» и «her» – в притяжательном падеже; они согласуются с «Anton, he» и «sister, she» в роде (муж. род, жен. род), лице (3-е лицо) и числе (ед. число).

Местоимения «it» (3-е лицо ед. числа, средн. род) и «them» (3-е лицо мн. числа) относятся к дополнениям, выраженным неодушевлёнными существительными «book» (ед. число) и «dolls» (мн. число); как дополнения, местоимения «it» и «them» стоят в косвенном падеже.

Подлежащие «he» и «she» стоят в 3-ем лице ед. числа; соответственно, их глаголы тоже употреблены в 3-ем лице ед. числа (is, likes).

Только личные местоимения имеют достаточно форм, чтобы выразить, более или менее полно, род, лицо, число и падеж в своих формах.

Формы и свойства других местоимений

Другие местоимения не имеют достаточно форм, чтобы выразить род, лицо, число или падеж. То есть, некоторые из них имеют некоторые грамматические формы.

Указательные местоимения «this, that» имеют формы мн. числа «these, those».

Это моя книга. Это (т.е. Эти) мои книги.

Эти книги интересные. Те книги не очень интересные.

Относительное местоимение «who» имеет форму «whom» в косвенном падеже и форму «whose» в притяжательном падеже.

Сотрудники, с которыми она обсуждала свой план, согласились помочь ей.

Студент, велосипед которого был украден, поехал домой на автобусе. (Студент, чей велосипед…)

Неопределённые местоимения «anybody, anyone, everybody, everyone, somebody, someone, nobody, no one, one» могут употребляться в притяжательном падеже.

На моём столе чья-то сумка.

Это была ничья вина.

Но большинство неопределённых местоимений не имеют никаких форм, чтобы выразить род, лицо, число или падеж; они всегда остаются в одной и той же форме. Тем не менее, они могут выразить грамматическое значение через лексическое значение и через функцию в предложении.

Например, местоимения «anybody, no one, who» имеют в виду людей, а не вещи (No one came to his party); «all, some, any, many, few, no, none» могут относиться к людям или вещам (neither of the boys; neither of the books); местоимения «each other» и «one another» не употребляются как подлежащие (Mike and Maria love each other).

Согласование в числе

Неопределённые местоимения выражают число в своём лексическом значении, что определяет, в единственном или множественном числе нужно употребить глагол, если неопределённое местоимение является подлежащим.

Местоимения «anybody, anyone, anything, everybody, everyone, everything, somebody, someone, something, nobody, no one, nothing, one, each, either, neither, much» употребляются с глаголом ед. числа.

Все ждут. (т.е. Каждый ждёт.)

Ничего не осталось.

Каждая из коробок была пуста.

Местоимения «both, few, many, others, several» употребляются с глаголом мн. числа.

Они оба здесь.

Немногие из них знают это.

Многие (из них) были сломаны.

Местоимения «all, any, most, none, some» принимают глагол в ед. или мн. числе в зависимости от того, к чему относится местоимение: к количеству / порции чего-то или к нескольким людям или вещам.

Вся эта еда была приготовлена нашими друзьями. Вся она очень вкусная.

Все его друзья здесь. Все они здесь.

Вопросительные местоимения «who, what» в функции подлежащего употребляются с глаголом в ед. числе, если сказуемое выражено основным глаголом.

Кто знает его адрес? Что случилось?

В случае составного именного сказуемого с глаголом-связкой «be», глагол «be» согласуется в числе с существительным (или местоимением), к которому относятся «who» или «what».

Кто этот человек? Кто они?

Как вас зовут? (т.е. Ваше имя?) Какие у вас планы?

В предложениях с относительным местоимением «who», глагол согласуется в числе с существительным, к которому относится «who».

Я знаю мальчика, который стоит у окна.

Я знаю мальчиков, которые стоят у окна.

Трудности

Как вы наверное поняли из материала выше, разнообразие местоимений и различия между ними могут представлять серьёзные трудности для изучающих английский язык.

Похожие местоимения, такие как «some» и «any», «each» и «every», «which» и «that», «it» и «this», представляют большую трудность; у них разное употребление, и каждое из них имеет свои особенности. (Некоторые различия описаны в ответах на ваши вопросы в подразделе Messages about Grammar (Pronouns) в разлеле Messages.)

Согласование местоимений с их существительными и согласование сказуемого с подлежащим, выраженным неопределённым местоимением, обычно представляют наибольшую трудность. В некоторых случаях, единственный способ избежать проблем с согласованием – перестроить предложение.

Проблемы рода

Большинство английских одушевлённых существительных не выражают род ни в форме, ни в значении. Как результат, не всегда ясно, «he» или «she» (и их формы «his, him, her») нужно употребить с такими существительными в ед. числе. Например:

Я хочу поговорить с дизайнером. Где я могу найти его? (его? её?)

Похожие (и более трудные) проблемы возникают, когда неопределённые местоимения «somebody, nobody, anyone, everyone, each», которые могут относиться к лицам мужского и женского пола, употреблены как подлежащие. В официальном английском языке, «he, his, him» употребляются (если нужно) с этими неопределёнными местоимениями; «they, their, them» (и «our») часто употребляются с этими местоимениями в разговорном английском языке.

Сравните употребление английских местоимений в официальном и разговорном стиле и употребление эквивалентных местоимений в русских предложениях.

Официальный стиль: Никто не предложил свою помощь. Все принесли свой собственный завтрак. У каждого из нас есть свои причины.

Разговорный стиль: Никто не предложил свою помощь. Все принесли свой собственный завтрак. У каждого из нас есть свои причины.

Проблемы числа

Проблемы с согласованием в числе обычно возникают, если вы забываете, какие неопределённые местоимения требуют глагола в ед. числе, а какие требуют глагола во мн. числе. (См. часть «Agreement in number» выше.)

Согласование глагола с двумя местоимениями в подлежащем также может вызывать затруднения. Например, подлежащее, выраженное двумя личными местоимениями, соединёнными союзом «and», принимает глагол в форме мн. числа. Если местоимения соединены союзами «or; either…or; neither…nor», глагол согласуется в числе с ближайшим местоимением. Сравните:

Вы и он должны быть там к десяти.

Или вы, или он должны быть там к десяти.

Общие рекомендации

Изучите правила употребления местоимений вместе с различными примерами употребления. Выберите простые, типичные примеры и употребляйте их в своей устной и письменной речи. Избегайте употребления сложных и спорных случаев.

Полезные материалы по теме

Личные, притяжательные и возвратные местоимения, с многими примерами употребления, описаны в материалах Personal Pronouns и Personal Pronouns in Examples в разделе Miscellany.

Согласование существительных и глаголов в числе, согласование неопределённых местоимений и глаголов в числе и согласование притяжательных местоимений с существительными и с неопределёнными местоимениями описаны в материале Agreement в разделе Grammar.

Употребление относительных местоимений в придаточных предложениях кратко описано в материале Word Order in Complex Sentences в разделе Grammar.

Примеры, иллюстрирующие употребление вопросительных местоимений (и других вопросительных слов) можно найти в материале Word Order in Questions в разделе Grammar.

The English pronouns form a relatively small category of words in Modern English whose primary semantic function is that of a pro-form for a noun phrase. Traditional grammars consider them to be a distinct part of speech, while most modern grammars see them as a subcategory of noun, contrasting with common and proper nouns.[1]: 22 Still others see them as a subcategory of determiner (see the DP hypothesis). In this article, they are treated as a subtype of the noun category.

They clearly include personal pronouns, relative pronouns, interrogative pronouns, and reciprocal pronouns. Other types that are included by some grammars but excluded by others are demonstrative pronouns and indefinite pronouns. Other members are disputed (see below).

Overview[edit]

Forms[edit]

Standard[edit]

Pronouns in formal modern English .

| Nominative | Accusative | Reflexive | Independent genitive |

Dependent genitive |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-person | Singular | I | me | myself | mine | my | |

| Plural | we | us | ourselves | ours | our | ||

| Second-person | Singular | Standard | you | you | yourself | yours | your |

| Poetic/dialectal | thou | thee | thyself | thine | thy | ||

| Plural | you | you | yourselves | yours | your | ||

| Third-person | Singular | Masculine | he | him | himself | his | his |

| Feminine | she | her | herself | hers | her | ||

| Neuter | it | it | itself | its | |||

| Epicene | they | them | themselves | theirs | their | ||

| Plural | they | them | themselves | theirs | their | ||

| Generic | one | one | oneself | one’s | |||

| Wh- | Relative & interrogative |

Personal | who | whom | whose | whose | |

| Non-personal | what | what | |||||

| which | which | ||||||

| Reciprocal | each other one another |

each other’s one another’s |

each other’s one another’s |

||||

| Dummy | there it |

Full list[edit]

Those types that are indisputably pronouns are the personal pronouns, relative pronouns, interrogative pronouns, and reciprocal pronouns. The full set is presented in the following table along with dummy there. Nonstandard, informal and archaic forms are in italics.

| Nominative | Accusative | Reflexive | Independent genitive |

Dependent genitive |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (subject) | (object) | (object = subject) | (possessive) | ||||

| First person |

Singular | I | me | myself | mine | my me (esp. BrE) mine (before vowel) |

|

| Plural | we | us | ourselves ourself |

ours | our | ||

| Second person |

Singular | Standard & Archaic formal |

you | you | yourself | yours | your |

| Archaic informal | thou | thee | thyself | thine | thy thine (before vowel) |

||

| Plural | Standard | you | you | yourselves | yours | your | |

| Archaic | ye | you | yourselves | yours | your | ||

| Nonstandard | ye y’all youse |

ye y’all youse |

yeerselves y’all’s selves |

yeers y’all’s |

yeer y’all’s |

||

| Third person |

Singular | Masculine | he | him | himself | his | his |

| Feminine | she | her | herself | hers | her | ||

| Neuter/ Impersonal |

it | it | itself | its | its | ||

| Epicene | they | them | themselves themself |

theirs | their | ||

| Plural | they | them | themselves | theirs | their | ||

| Generic/ Indefinite |

Formal | one | one | oneself | one’s | ||

| Informal | you | you | yourself | your | your | ||

| Interrogative | Personal | who | whom who |

whose | whose | ||

| Impersonal | what which |

what which |

of what of which |

of what of which |

|||

| Relative | Restrictive or nonrestrictive |

Personal | who | whom who* |

whose | whose | |

| Impersonal | which | which | whose | whose | |||

| Restrictive | Personal or impersonal |

that† | that†* Ø* |

whose | whose | ||

| Reciprocal | each other one another |

each other’s one another’s |

each other’s one another’s |

||||

| Dummy | there it |

*Whom and which can be the object of a fronted preposition, but not who, that or an omitted (Ø) pronoun: The chair on which she sat or The chair (that) she sat on, but not *The chair on that she sat.

†Except in free or fused relative constructions, in which case what, whatever or whichever is used for a thing and whoever or whomever is used for a person: What he did was clearly impossible, Whoever you married is welcome here (see below).

Distinguishing characteristics[edit]

Pro-forms[edit]

Pronoun is a category of words. A pro-form is not. It is a meaning relation in which a phrase «stands in» for (expresses the same content as) another where the meaning is recoverable from the context.[2] In English, pronouns mostly function as pro-forms, but there are pronouns that are not pro-forms and pro-forms that are not pronouns.[3]: 239

| Example | Pronoun | Pro-form | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | It‘s a good idea. | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2 | I know the people who work there. | ✓ | ✓ |

| 3 | Who works there? | ✓ | |

| 4 | It‘s raining. | ✓ | |

| 5 | I asked her to help, and she did so right away. | ✓ | |

| 6 | JJ and Petra helped, but the others didn’t. | ✓ |

Examples [1 & 2] are pronouns and pro-forms. In [1], the pronoun it «stands in» for whatever was mentioned and is a good idea. In [2], the relative pronoun who stands in for «the people».

Examples [3 & 4] are pronouns but not pro-forms. In [3], the interrogative pronoun who doesn’t stand in for anything. Similarly, in [4], it is a dummy pronoun, one that doesn’t stand in for anything. No other word can function there with the same meaning; we don’t say «the sky is raining» or «the weather is raining».

Finally, in [5 & 6], there are pro-forms that are not pronouns. In [5], did so is a verb phrase, but it stands in for «help». Similarly, in [6], others is a common noun, not a pronoun, but the others stands in for this list of names of the other people involved (e.g., Sho, Alana, and Ali).

Pronouns can be pro-forms for non-noun phrases. For example, in I fixed the bike, which was quite a challenge, the relative pronoun which doesn’t stand in for «the bike». Instead, it stands in for the entire proposition «I fixed the bike», a clause, or arguably «fixing the bike», a verb phrase.

Deixis[edit]

Most pronouns are deictic:[1]: 68 they have no inherent denotation, and their meaning is always contextual. For example, the meaning of me depends entirely on who says it, just as the meaning of you depends on who is being addressed. Pronouns are not the only deictic words though. For example now is deictic, but it’s not a pronoun.[4] Also, dummy pronouns and interrogative pronouns are not deictic. In contrast, most noun phrases headed by common or proper nouns are not deictic. For example, a book typically has the same denotation regardless of the situation in which it is said.

Syntactic functions[edit]

English pronouns have all of the functions of other noun phrases:[1]: ch. 5

| Function | Non-pronoun | Pronoun |

|---|---|---|

| Subject | Jess is here. | She is here. |

| Object | I have two pens. | I have them. |

| Object of a preposition | It went to your address. | It went to you. |

| Predicative complement | This is my brother. | This is him. |

| Determinative | the box’s top | its top |

| Adjunct | Try again Monday. | I did it myself. |

| Modifier | a Shetland pony | a she goat |

On top of this, pronouns can appear in interrogative tags (e.g., that’s the one, isn’t it?).[1]: 238 These tags are formed with an auxiliary verb and a pronoun. Other nouns cannot appear in this construction. This provides justification for categorizing dummy there as a pronoun.[1]: 256

Subjects[edit]

Subject pronouns are typically in nominative form (e.g., She works here.), though independent genitives are also possible (e.g., Hers is better.). In non-finite clauses, however, there is more variety. In present participial clauses, the nominative, accusative, and dependent genitive are all possible:[1]: 460, 467

- Nominative: Some people, I being one of them, are just not good at it.

- Accusative: Him getting bullied doesn’t make him weak.

- Dependent genitive: It worked without our having to do anything at all.

In infinitival clauses, accusative case pronouns function as the subject:

- Accusative: It’s not easy for me to change.

Object[edit]

Object pronouns are typically in nominative form (e.g., I saw him.) but may also be reflexive (e.g., She saw herself) or independent genitive (e.g., We got ours.).

Object of a preposition[edit]

The pronoun object of a preposition is typically in the accusative form but may also be reflexive (e.g., She sent it to herself) or independent genitive (e.g., I hadn’t heard of theirs.). With but, than, and as in a very formal register, nominative is also possible (e.g., You’re taller than me/I.)[1]: 461

Predicative complement[edit]

A pronoun in predicative complement position is typically in the accusative form (e.g., It’s me) but may also be reflexive (e.g., She isn’t herself today) or independent genitive (e.g., It’s theirs.).

Determinative[edit]

Only genitive pronouns may function as determinatives.

Adjunct[edit]

The most common form for adjuncts is the reflexive (e.g., I did it myself). Independent genitives and accusative are also possible (e.g., Only one matters, mine/me.).

Dependents[edit]

Like proper nouns, but unlike common nouns, pronouns usually resist dependents.[1]: 425 They are not always ungrammatical, but they are quite limited in their use:

| Common noun | Pronoun | |

|---|---|---|

| Determinative | the book | the you you want to be

*the you |

| Relative clause | books you have | the you you want to be

*you you want to be |

| Preposition phrase modifier | books from home | *it from home |

| Adjective phrase modifier | new books | a new you

*new them |

| Nominal modifier | school books | school me is different from home me |

| Complement | answer to the quiz | *it to the quiz |

Examples marked with an asterisk are ungrammatical.

Undisputed subtypes[edit]

Personal[edit]

Personal pronouns are those that participate in the grammatical and semantic systems of person (1st, 2nd, & 3rd person).[1]: 1463 It’s not that they refer to people. They typically form definite NPs.

The personal pronouns of modern standard English are presented in the table above. They are I, you, she, he, it, we, and they, and their inflected forms.

The second-person you forms are used with both singular and plural reference. In the Southern United States, y’all (from you all) is used as a plural form, and various other phrases such as you guys are used in other places. An archaic set of second-person pronouns used for singular reference is thou, thee, thyself, thy, thine, which are still used in religious services and can be seen in older works, such as Shakespeare’s—in such texts, ye and the you set of pronouns are used for plural reference, or with singular reference as a formal V-form. You can also be used as an indefinite pronoun, referring to a person in general (see generic you), compared to the more formal alternative, one (reflexive oneself, possessive one’s).

The third-person singular forms are differentiated according to the gender of the referent. For example, she is used to refer to a female person, sometimes a female animal, and sometimes an object to which female characteristics are attributed, such as a ship or a country. A male person, and sometimes a male animal, is referred to using he. In other cases it can be used. (See Gender in English.)

The third-person form they is used with both plural and singular referents. Historically, singular they was restricted to quantificational constructions such as Each employee should clean their desk and referential cases where the referent’s gender was unknown.[5] However, it is increasingly used when the referent’s gender is irrelevant or when the referent is neither male nor female.[6]

The dependent genitive pronouns, such as my, are used as determinatives together with nouns, as in my old man, some of his friends. The independent genitive forms like mine are used as full noun phrases (e.g., mine is bigger than yours; this one is mine). Note also the construction a friend of mine (meaning «someone who is my friend»). See English possessive for more details.

Interrogative[edit]

The interrogative pronouns are who, whom, whose, which and what (also with the suffix -ever). They are chiefly used in interrogative clauses for the speech act of asking questions.[1]: 61 What has impersonal gender, while who, whom and whose have personal gender;[1]: 904 they are used to refer to persons. Whom is the accusative form of who (though in most contexts this is replaced by who), while whose is the genitive form.[1]: 464 For more information see who.

All the interrogative pronouns can also be used as relative pronouns, though what is quite limited in its use;[7] see below for more details.

Relative[edit]

The main relative pronouns in English are who (with its derived forms whom and whose), and which.[8]

The relative pronoun which refers to things rather than persons, as in the shirt, which used to be red, is faded. For persons, who is used (the man who saw me was tall). The oblique case form of who is whom, as in the man whom I saw was tall, although in informal registers who is commonly used in place of whom.

The possessive form of who is whose (for example, the man whose car is missing); however the use of whose is not restricted to persons (one can say an idea whose time has come).

The word that is disputed. Traditionally, it is considered a pronoun, but modern approaches disagree. See below.

The word what can be used to form a free relative clause – one that has no antecedent and that serves as a complete noun phrase in itself, as in I like what he likes. The words whatever and whichever can be used similarly, in the role of either pronouns (whatever he likes) or determiners (whatever book he likes). When referring to persons, who(ever) (and whom(ever)) can be used in a similar way (but not as determiners).

Generic[edit]

A generic pronoun is one with the interpretation of «a person in general». These pronouns cannot have a definite or specific referent, and they «cannot be used as an anaphor to another NP.»[1]: 427 The generic pronouns are one (e.g., one can see oneself in the mirror) and you (e.g., In Tokugawa Japan, you couldn’t leave the country), with one being more formal than you.[1]: 427

Reciprocal[edit]

The English reciprocal pronouns are each other and one another. Although they are written with a space, they’re best thought of as single words. No consistent distinction in meaning or use can be found between them. Like the reflexive pronouns, their use is limited to contexts where an antecedent precedes it. In the case of the reciprocals, they need to appear in the same clause as the antecedent.[7]

Disputed pronouns[edit]

Determiners[edit]

Today, the English determiners are generally seen as a separate category of words, but they were traditionally viewed as adjectives when they came before a noun (e.g., some people, no books, each book) and as pronouns when they were pro-forms (e.g., I’ll have some; I had none, each of the books).[1]: 22

What and which[edit]

As pronouns, what and which have non-personal gender.[1]: 398 This means they cannot be used to refer to persons; what is that cannot mean «who is that». But there are also determiners with the same forms. The determiners are not gendered, so they can refer to persons or non-persons (e.g., what genius said that).

Relative which is usually a pronoun, but it can be a determiner in cases like It may rain, in which case we won’t go. What is almost never a relative word, but when it is, it is a pronoun (e.g., I didn’t see what you took.)

Demonstratives[edit]

The demonstrative pronouns this (plural these), and that (plural those), are a sub-type of determiner in English.[1]: 373 Traditionally, they are viewed as pronouns in cases such as these are good; I like that.

Indefinites[edit]

The determiners starting with some-, any, no, and every— and ending with -one, -body, —thing, -place (e.g., someone, nothing) are often called indefinite pronouns, though others consider them to be compound determiners.[1]: 423

The generic pronouns one and the generic use of you are sometimes called indefinite. These are uncontroversial pronouns.[9] Note, however, that English has three words that share the spelling and pronunciation of one.[1]: 426–427

- determiner: I have one book; I’ll have one too.

- noun: one plus two is three

- pronoun: if one considers oneself correct

Dummy there[edit]

The word there is a dummy pronoun in some clauses, chiefly existential (There is no god) and presentational constructions (There appeared a cat on the window sill). The dummy subject takes the number (singular or plural) of the logical subject (complement), hence it takes a plural verb if the complement is plural. In informal English, however, the contraction there’s is often used for both singular and plural.[10]

There can undergo inversion, Is there a test today? and Never has there been a man such as this. It can also appear without a corresponding logical subject, in short sentences and question tags: There wasn’t a discussion, was there?

The word there in such sentences has sometimes been analyzed as an adverb, or as a dummy predicate, rather than as a pronoun.[11] However, its identification as a pronoun is most consistent with its behavior in inverted sentences and question tags as described above.

Because the word there can also be a deictic adverb (meaning «at that place»), a sentence like There is a river could have either of two meanings: «a river exists» (with there as a pronoun), and «a river is in that place» (with there as an adverb). In speech, the adverbial there would be given stress, while the pronoun would not – in fact, the pronoun is often pronounced as a weak form, /ðə(r)/.

Yesterday, today, and tomorrow[edit]

These words are sometimes classified as nouns (e.g., Tomorrow should be a nice day), and sometimes as adverbs (I’ll see you tomorrow).[12] But they are alternatively classified as pronouns in both of these examples.[1]: 429 In fact, these words have most of the characteristics of pronouns (see above). In particular, they are pro-forms, and they resist most dependents (e.g., *a good today).

Relative that[edit]

Traditional grammars classify that as a relative pronoun.[13] Most modern grammars disagree, calling it a subordinator or a complementizer.[1]: 63

Relative that is normally found only in restrictive relative clauses (unlike which and who, which can be used in both restrictive and unrestrictive clauses). It can refer to either persons or things, and cannot follow a preposition. For example, one can say the song that [or which] I listened to yesterday, but the song to which [not to that] I listened yesterday. Relative that is usually pronounced with a reduced vowel (schwa), and hence differently from the demonstrative that (see Weak and strong forms in English). If that is not the subject of the relative clause (in the traditional view), it can be omitted (the song I listened to yesterday).

Other pro-forms[edit]

There is some confusion about the difference between a pronoun and a pro-form. For example, some sources make claims such as the following:

We can use other as a pronoun. As a pronoun, other has a plural form, others:

- We have to solve this problem, more than any other, today

- I’ll attach two photos to this email and I’ll send others tomorrow.[14]

But other is just a common noun here. Unlike pronouns, it readily takes a determiner (many others) or a relative clause modifier (others that we know).

Old English[edit]

Interrogative pronouns[edit]

Hwā («who») and hwæt («what») follow natural gender, not grammatical gender: as in Modern English, hwā is used with people, hwæt with things. However, that distinction only matters in the nominative and accusative cases, as they are identical in other cases:

| «who» | «what» | |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | hwā | hwæt |

| Accusative | hwone | |

| Genitive | hwæs | |

| Dative | hwām | |

| Instrumental | hwon, hwȳ |

Hwelċ («which» or «what kind of») is inflected like an adjective. Same with hwæðer, which also means «which» but is only used between two alternatives:

| Old English | Hwæðer wēnst þū is māre, þē þīn sweord þē mīn? |

| Translation | Which one do you think is bigger, your sword or mine? |

Personal pronouns[edit]

The first- and second-person pronouns are the same for all genders. They also have special dual forms, which are only used for groups of two things, as in «we both» and «you two.» The dual forms are common, but the ordinary plural forms can always be used instead when the meaning is clear.

| Case | 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Plural | |||

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | ||||||||

| Nominative | iċ | wit | wē | þū | ġit | ġē | hē | hit | hēo | hīe |

| Accusative | mē | unc | ūs | þē | inc | ēow | hine | hit | hīe | |

| Dative | him | hire | him | |||||||

| Genitive | mīn | uncer | ūre | þīn | incer | ēower | his | heora |

Many of the forms above bear a strong resemblance to the Modern English words they eventually became. For instance, in the genitive case, ēower became «your,» ūre became «our,» and mīn became «my.» However, the plural third-person personal pronouns were all replaced with Old Norse forms during the Middle English period, yielding «they,» «them,» and «their.»

Middle English[edit]

Middle English personal pronouns were mostly developed from those of Old English, with the exception of the third-person plural, a borrowing from Old Norse (the original Old English form clashed with the third person singular and was eventually dropped). Also, the nominative form of the feminine third-person singular was replaced by a form of the demonstrative that developed into sche (modern she), but the alternative heyr remained in some areas for a long time.

As with nouns, there was some inflectional simplification (the distinct Old English dual forms were lost), but pronouns, unlike nouns, retained distinct nominative and accusative forms. Third-person pronouns also retained a distinction between accusative and dative forms, but that was gradually lost: the masculine hine was replaced by him south of the Thames by the early 14th century, and the neuter dative him was ousted by it in most dialects by the 15th.[15]

The following table shows some of the various Middle English pronouns. Many other variations are noted in Middle English sources because of differences in spellings and pronunciations at different times and in different dialects.[16]

| Personal pronouns | 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |||

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | ||||||

| Nominative | ic, ich, I | we | þeou, þ(o)u, tu | ye | he | hit | s(c)he(o) | he(o)/ þei |

| Accusative | mi | (o)us | þe | eow, eou, yow, gu, you | hine | heo, his, hi(r)e | his/ þem | |

| Dative | him | him | heo(m), þo/ þem | |||||

| Possessive | min(en) | (o)ure, ures, ure(n) | þi, ti | eower, yower, gur, eour | his, hes | his | heo(re), hio, hire | he(o)re/ þeir |

| Genitive | min, mire, minre | oures | þin, þyn | youres | his | |||

| Reflexive | min one, mi selven | us self, ous-silve | þeself, þi selven | you-self/ you-selve | him-selven | hit-sulve | heo-seolf | þam-selve/ þem-selve |

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Huddleston, Rodney; Pullum, Geoffrey K. (2002). The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Crystal, David (1985). A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics (2nd ed.). Basil Blackwell.

- ^ Huddleston, Rodney; Pullum, Geoffrey K. (2002). Cambridge grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ «now | meaning of now in Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English | LDOCE». www.ldoceonline.com. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Lagunoff, Rachel (1997). Singular They (Doctoral dissertation). UCLA.

- ^ Abadi, Mark. «‘They’ was just named 2015’s Word of the Year». Business Insider. Retrieved 2021-03-22.

- ^ a b Payne, John; Huddleston, Rodney (2002). «Nouns and noun phrases». In Huddleston, Rodney; Pullum, Geoffrey (eds.). The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 479–481. ISBN 0-521-43146-8.

We conclude that both head and phrasal genitives involve case inflection. With head genitives it is always a noun that inflects, while the phrasal genitive can apply to words of most classes.

- ^ Some linguists consider that in such sentences to be a complementizer rather than a relative pronoun. See English relative clauses: Status of that.

- ^ «One Definition». dictionary.com. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Fowler 2015, p. 813

- ^ For a treatment of there as a dummy predicate, based on the analysis of the copula, see Moro, A., The Raising of Predicates. Predicative Noun Phrases and the Theory of Clause Structure, Cambridge Studies in Linguistics, 80, Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- ^ «tomorrow | meaning of tomorrow in Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English | LDOCE». www.ldoceonline.com. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ «Definition of THAT». www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ «Other, others, the other or another ?». dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Fulk, R.D., An Introduction to Middle English, Broadview Press, 2012, p. 65.

- ^ See Stratmann, Francis Henry (1891). A Middle-English dictionary. London: Oxford University Press. OL 7114246M. and Mayhew, AL; Skeat, Walter W (1888). A Concise Dictionary of Middle English from A.D. 1150 to 1580. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Works cited[edit]

- Fowler, H.W. (2015). Butterfield, Jeremy (ed.). Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage. Oxford University Press. p. 813. ISBN 978-0-19-966135-0.

The Pronoun

Прежде, чем мы начнём разбирать виды местоимений, давайте дадим определение местоимению.

Определение. Местоимение- часть речи, которая употребляется вместо имени существительного, имени прилагательного, редко наречия.

Jack likes dogs. He wants to buy a puppy. – Джек любит собак. Он хочет купить щенка.

( во втором предложении he- местоимение, употреблено вместо имени Jack, чтобы избежать повторения.)

Местоимения в английском языке бывают:

— Личные местоимения (Personal pronouns)

— Притяжательные местоимения (Possessive pronouns)

— Указательные местоимения (Demonstrative pronouns)

— Возвратные местоимения (Reflexive pronouns)

— Вопросительные местоимения (Interrogative pronouns)

— Относительные местоимения (Relative pronouns)

— Взаимные местоимения (Reciprocal pronouns)

— Неопределённые и отрицательные местоимения (Indefinite and Negative pronouns)

— Определяющие местоимения (Defining pronouns)

Рассмотрим их подробно:

1) Личные местоимения (Personal pronouns)

Личные местоимения в английском имеют форму падежей:

— именительный падеж (the nominative case)

— объективный падеж ( the objective case)

Рассмотрим таблицу.

|

Nominative (именительный) |

Objective (объективный) |

|

I(я) |

Me(мне) |

|

He(он) |

Him(ему) |

|

She(она) |

Her(ей) |

|

It(оно) |

It(ей/ему) |

|

You(ты/вы) |

You(тебе/вам) |

|

We(мы) |

Us(нам) |

|

They(они) |

Them(им) |

В предложение личные местоимения в именительном падеже являются подлежащим, а в объективном падеже — дополнением.

Пример: I gave him my book. — Я дал ему мою книгу

2) Притяжательные местоимения (Possessive pronouns)

Притяжательные местоимения в английском выражают принадлежность и имеют две формы:

— основная форма

— абсолютная форма

Рассмотрим таблицу.

|

Основная форма |

Абсолютная форма |

|

My(мой) |

Mine |

|

His(его) |

His |

|

Her(её) |

Hers |

|

Its |

— |

|

Your(твой/ваш) |

Yours |

|

Our(наш) |

Ours |

|

Their(их) |

Theirs |

Основная форма употребляется, когда притяжательное местоимение стоит перед именем существительным.

Пример:This is my car- Эта моя машина.

Абсолютная форма употребляется для того, чтобы определяемое существительное не повторялось.

Пример: This is my car and this is yours— Это моя машина, а это твоя.

3) Указательные местоимения (Demonstrative pronouns)

Указательные местоимения в английском языке:

This- это, этот, эта (употребляется с единственным числом)

Пример: I like this book- Мне нравится эта книга.

These- эти (употребляется со множественным числом)

Пример: I like these books- мне нравятся эти книги.

That- тот, та, то (употребляется с единственным числом)

Пример: I like that book- Мне нравится та книга.

Those- те (употребляется со множественным числом)

Пример: I like those books- Мне нравятся те книги.

4) Возвратные местоимения (Reflexive pronouns)

Возвратные местоимения образуются путём прибавления –self в единственном числе, —selves во множественном числе.

Пример: I`ll do it myself- я сделаю это сам.

1). Часто возвратные местоимения употребляются с глаголами:

— blame- обвинять

Пример: Don`t blame yourself- Не вини себя

— amuse- развлекаться, приятно проводить время

Пример: They amused themselves walking together- Они хорошо провели время, гуляю вместе.

— enjoy- наслаждаться, получать удовольствие

Пример: They enjoyed themselves on the beach — Они хорошо провели время на пляже

-cut- резать

Пример: The girl has cut herself very well- Девушка очень хорошо себя подстригла

— hurt- причинять боль

Пример: Don`t hurt yourself- Не причиняй себе боль

— dry- сушить

Пример: You`re wet. Please dry yourself- Ты мокрый. Пожалуйста, вытри себя

— introduce- представляться

Пример: Let me introduce myself- Позволь мне представиться

2). Возвратные местоимения употребляются после предлогов

Пример: They cooked the pie themselves- Они приготовили пирог сами

3). Возвратные местоимения не используются после глаголов:

— feel- чувствовать

Пример: I feel great- Я чувствую себя великолепно.

—relax- расслабляться

Пример: Please, relax!- Пожалуйста, расслабься!

— behave- вести себя, поступать, держаться

Пример: You behave like a child- Ты ведёшь себя как ребёнок

— concentrate- сосредоточиться

Пример: If you can concentrate you will write an excellent essay- Если ты сможешь сосредоточиться, ты напишешь отличное эссе

wash – мыть; dress- одеваться; shave- бриться

Пример: I get up at 7 a.m., wash, shave, then after breakfast I dress and go out- Я встаю в 7 утра, умываюсь, бреюсь, затем после завтрака я одеваюсь и выхожу.

Но!!!

Wash yourself! — Помойся!

Dress yourself! — Оденься!

Shave yourself! – Побрейся!

Behave yourself! — Веди себя хорошо!

Рассмотрим таблицу возвратных местоимений

|

Nominative (именительный) |

Objective (объективный) |

|

I(я) |

Me(мне) |

|

He(он) |

Him(ему) |

|

She(она) |

Her(ей) |

|

It(оно) |

It(ей/ему) |

|

You(ты/вы) |

You(тебе/вам) |

|

We(мы) |

Us(нам) |

|

They(они) |

Them(им) |

5) Вопросительные местоимения (Interrogative pronouns)

Данные местоимения используют для образования специальных вопросов.

К вопросительным местоимениям относятся:

Who- кто?

Whom- кого? кому?

What- что?

Which- который?

Whose- чей?

1). Отличие между who и whom:

Местоимение Who имеет 2 падежа:

— именительный падеж who

— объективный падеж whom

Именительный падеж употребляется в качестве подлежащего:

Пример: Who wants to be the first? — Кто хочет быть первым?

Объективный падеж употребляется в качестве дополнения:

Пример: Whom are you waiting for?- Кого ты ждёшь?

2). Отличие между what и which:

Местоимение what может использоваться со значение какой.

Пример: What country do you live in? — В какой стране ты живёшь?

Местоимение which употребляется, когда речь идёт о выборе из ограниченного числа лиц и предметов.

Пример: Which puppy do you like?- Какой щенок тебе нравится?

6) Относительные местоимения (Relative pronouns)

Относительные местоимения употребляются для связи главного предложения с придаточным.

К относительным местоимениям относятся:

Who- кто

Whom- кому

Whose- чей

Which-который

That- который

1) Who (whom). Как мы уже знаем, данное местоимение имеет 2 падежа: именительный и объективный. Who используется в качестве подлежащего, а whom- в качестве дополнения.

Пример: The girl who danced in the club is my friend- Девушка, которая танцевала в клубе, моя подруга.

The girl whom we saw in the club is my friend- Девушка, которую мы видели в клубе, моя подруга.

2) Отличие which от who.

Местоимение which употребляется с неодушевлёнными предметами и животными.

Пример: I like my dress which I`ve bought- Мне нравится моё платье, которое я купила.

Местоимение who употребляется с одушевлёнными именами существительными.

Пример: This is that man who was there- Это тот мужчина, который был там.

3) Местоимение whose. Употребляется с одушевлёнными и неодушевлёнными именами существительными.

Пример: I met Andy whose parents won a prize – Я встретила Энди, у которого родители выиграли приз.

I saw the house whose roof is cover with grass- я видел дом, крыша которого усеяна травой.

4) Местоимение that. Употребляется с одушевлёнными и неодушевлёнными именами существительными, это местоимение можется использоваться вместо местоимения which и whom.

Пример: The girl that we saw in the club is my friend- Девушка, которую мы видели в клубе, моя подруга.

7) Взаимные местоимения (Reciprocal pronouns)

К взаимным местоимениям относятся:

Each other- друг друга

One another- один другого

Each other относится к двум лицам или предметам.

Пример: They hate each other- Они не ненавидят друг друга.

One another относится к большему количеству лиц или предметов.

Пример: My friend help one another- Мои друзья помогают друг другу.

(Indefinite and Negative pronouns)

К ним относятся:

— Местоимения some и any. Употребляются в значении некоторого количества немного, сколько-нибудь. Используются с неисчисляемыми именами существительными.

Some употребляется в утвердительных предложениях.

Пример: I have some cards- У меня есть несколько карточек..

Any употребляется в вопросительных и отрицательных предложениях.

Пример: Do you have any cards?- У тебя есть карточки?

I don`t have any cards?- У меня нет карточек.

-Местоимения no и none

Местоимение no заменяет конструкцию not… a (перед исчисляемыми именами существительными в единственном числе) , not… any (перед неисчисляемыми существительными и перед исчисляемыми существительными во множественном числе).

Пример: I have no car- У меня нет машины.

В данном примере мы можем сказать I don`t have a car или I have no car. Местоимение no заменяет конструкцию not…a перед исчисляемым существительным в единственном числе.

Пример: We have no sugar- У нас нет сахара.

В данном предложении можно сказать We don`t have any sugar или We have no sugar. Местоимение no заменяет конструкцию not…any (перед неисчисляемым существительным).

Местоимение none заменяет исчисляемые существительные в единственном и во множественном числе и неисчисляемые существительные.

Пример: Are there any pens on the table? — No, there are none.

— Производные местоимения от some/any/no.

К данным местоимениям можно прибавлять слова thing (для неодушевлённых существительных), body (для одушевлённых существительных).

Something — что-нибудь, что-то (используется в утвердительных предложениях).

Пример: I have something for you- у меня есть что-то для тебя.

Anything- что-то, что-нибудь (используется в отрицательных и вопросительных предложениях).

Пример: Do you have anything for me? — У тебя есть что-то для меня?

Nothing- ничего (используется в отрицательных предложениях)

Пример: No, I have nothing for you- Нет, у меня ничего нет для тебя.

Somebody- кто-то, кто-нибудь (используется в утвердительных предложениях).

Пример: There is somebody in the room- В комнате кто-то есть

Anybody- кто-то, кто-нибудь (используется в отрицательных и вопросительных предложениях).

Пример: Is there anybody in the room?- Ecть кто-нибудь в комнате?

Nobody- никто (используется в отрицательных предложениях)

Пример: There is nobody in the room- В комнате никого нет.

Somewhere- где-нибудь, куда-нибудь, где-то (используется в утвердительных предложениях)

Пример: We saw him somewhere- Мы видели его где-то.

Anywhere- где-нибудь, куда-нибудь, где-то (используется в вопросительных и отрицательных предложениях)

Пример: Have you seen him anywhere?- Ты его видел где-то?

Nowhere- нигде (используется в отрицательных предложениях)

Пример: I have seen him nowhere- Я его нигде не видел.

-Местоимения much (many), little (few), a little (a few).

Для того, чтобы понять в чём различие рассмотрим таблицу:

|

Исчисляемые существительные |

Неисчисляемые существительные |

|

many (много) |

much (много) |

|

few (мало) |

little(мало) |

|

a few(немного) |

a little(немного) |

Much/ Many употребляются:

1) в отрицательных предложениях:

Пример: We don`t have much time for it – У нас нет для этого много времени.

2) в вопросах:

Пример: Are there many books on the table? — На столе много книг?

3) в конструкциях со значением времени:

Пример: I have seen for many times- Мы не виделись много лет.

4) в конструкциях as…as

Пример: I`ll give as much as you wish- Я дам тебе так много, сколько тебе хочется.

5) в конструкции not much/not many в начале предложения:

Пример: Not many want it- Не многие хотят этого.

В утвердительных предложениях мы употребляем a lot of/ plenty of- много.

Пример: I have a lot of cards- У меня много карточек.

Отличие little/few от a little/ a few:

Little/few- мало, недостаточно для чего-то, несут отрицательный смысл.

A little/ a few- немного, но достаточно, несут положительный смысл.

Сравним:

Пример: She has a few toys – У неё несколько игрушек (мало, но достаточно)

She has few toys- У неё мало игрушек (мало, не достаточно)

— Местоимение one.

Используется, чтобы избежать повторения определяемого существительного.

Пример: I like these dresses. I think I`ll buy the red one- Мне нравится эти платья, я думаю, я куплю красное.

Для того, чтобы не говорить слово платье 2 раза, мы можем заменить его на слово one.

9) Определяющие местоимения (Defining pronouns)

— Местоимение all:

All (всё, все) употребляется с неисчисляемыми существительными и исчисляемыми существительными во множественном числе.

Пример: All the pupils go to the museum- Все школьники идут в музей.

Запомни! Артикль the и указательные местоимения ставятся после all.

Местоимение all также употребляется в качестве существительного в значении всё

Пример: My parents know all- Мои родители знают всё.

All часто заменяется местоимением everybody.

Запомни! All в данном случае используется во множественном числе, а everybody— в единственном.

Пример: All are here- Все здесь

Everybody is here- Все здесь

All часто заменяется местоимением everything.

Запомни! All и everything в данном случае используются в единственном числе.

Пример: All is ok- Всё хорошо

Everything is ok- Всё хорошо

—Местоимение both

Переводится как оба, является определением перед существительным.

Запомни! Артикль the и указательные местоимения ставятся после both.

Пример: Both the girls like this dress- Обеим девочкам нравится это платье.

Both может заменять существительное.

Пример: I like these books. I`ll take both- Мне нравятся эти книги. Я возьму обе.

В отрицательных предложениях вместо both используется neither.

Пример: Both the cars were red- Обе машины были красные.

Neither the cars were red- Обе машины не были красными.

— Местоимение either/neither

Данные местоимения относятся к двум лицам или предметам.

Either –любой, тот или другой, каждый (один из двух)

Пример: There are two pens. Take either- Лежит две ручки. Возьми любую.

On either side of the street you can see flowers- На каждой стороне улицы ты можешь увидеть цветы.

Neither — ни тот, ни другой.

Пример: Neither of the boys are right- Никто из мальчиков не прав.

Существуют конструкции:

Either…or – или…или

Пример: He is either a doctor or either a vet- Он либо доктор, либо ветеринар.

Neither…nor- ни…ни

Пример: Neither my friend nor I like this car- Ни моему другу, ни мне не понравилась эта машина.

-Местоимения other/another

Other – другой (иной). Используется в единственном и во множественном числе.

Пример: Give me please other books- Дайте мне пожалуйста другие книги.

The other- другой (один из двух)

Пример: The car is on the other side of the street- Машина на другой стороне улицы.