First time? Quick how-to.

This visual quick how-to guide shows you how to search a word, for example «handspeak».

- All

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

Search Tips and Pointers

Search/Filter: Enter a keyword in the filter/search box to see a list of available words with the «All» selection. Click on the page number if needed. Click on the blue link to look up the word. For best result, enter a partial word to see variations of the word.

Alphabetical letters: It’s useful for 1) a single-letter word (such as A, B, etc.) and 2) very short words (e.g. «to», «he», etc.) to narrow down the words and pages in the list.

For best result, enter a short word in the search box, then select the alphetical letter (and page number if needed), and click on the blue link.

Don’t forget to click «All» back when you search another word with a different initial letter.

If you cannot find (perhaps overlook) a word but you can still see a list of links, then keep looking until the links disappear! Sharpening your eye or maybe refine your alphabetical index skill.

Add a Word: This dictionary is not exhaustive; ASL signs are constantly added to the dictionary. If you don’t find a word/sign, you can send your request (only if a single link doesn’t show in the result).

Videos: The first video may be NOT the answer you’re looking for. There are several signs for different meanings, contexts, and/or variations. Browsing all the way down to the next search box is highly recommended.

Video speed: Signing too fast in the videos? See HELP in the footer.

ASL has its own grammar and structure in sentences that works differently from English. For plurals, verb inflections, word order, etc., learn grammar in the «ASL Learn» section. For search in the dictionary, use the present-time verbs and base words. If you look for «said», look up the word «say». Likewise, if you look for an adjective word, try the noun or vice versa. E.g. The ASL signs for French and France are the same. If you look for a plural word, use a singular word.

Are you a Deaf artist, author, traveler, etc. etc.?

Some of the word entries in the ASL dictionary feature Deaf stories or anecdotes, arts, photographs, quotes, etc. to educate and to inspire, and to be preserved in Deaf/ASL history, and to expose and recognize Deaf works, talents, experiences, joys and pains, and successes.

If you’re a Deaf artist, book author, or creative and would like your work to be considered for a possible mention on this website/webapp, introduce yourself and your works. Are you a Deaf mother/father, traveler, politician, teacher, etc. etc. and have an inspirational story, anecdote, or bragging rights to share — tiny or big doesn’t matter, you’re welcome to email it. Codas are also welcome.

Hearing ASL student, who might have stories or anecdotes, also are welcome to share.

ASL to English reverse dictionary

Don’t know what a sign mean? Search ASL to English reverse dictionary to find what an ASL sign means.

Vocabulary building

To start with the First 100 ASL signs for beginners, and continue with the Second 100 ASL signs, and further with the Third 100 ASL signs.

Language Building

Learning ASL words does not equate with learning the language. Learn the language beyond sign language words.

Contextual meaning: Some ASL signs in the dictionary may not mean the same in different contexts and/or ASL sentences. A meaning of a word or phrase can change in sentences and contexts. You will see some examples in video sentences.

Grammar: Many ASL words, especially verbs, in the dictionary are a «base»; be aware that many of them can be grammatically inflected within ASL sentences. Some entries have sentence examples.

Sign production (pronunciation): A change or modification of one of the parameters of the sign, such as handshape, movement, palm orientation, location, and non-manual signals (e.g. facial expressions) can change a meaning or a subtle variety of meaning. Or mispronunciation.

Variation: Some ASL signs have regional (and generational) variations across North America. Some common variations are included as much as possible, but for specifically local variations, interact with your local community to learn their local variations.

Fingerspelling: When there is no word in one language, borrowing is a loanword from another language. In sign language, manual alphabet is used to represent a word of the spoken/written language.

American Sign Language (ASL) is very much alive and indefinitely constructable as any spoken language. The best way to use ASL right is to immerse in daily language interactions and conversations with Ameslan/Deaf people (or ASLians).

Sentence building

Browse phrases and sentences to learn sign language, specifically vocabulary, grammar, and how its sentence structure works.

Sign Language Dictionary

According to the archives online, did you know that this dictionary is the oldest sign language dictonary online since 1997 (DWW which was renamed to Handspeak in 2000)?

This dictionary is not exhaustive; the ASL signs are constantly added to the dictionary. If you don’t find the word/sign, you can send your request via email. Browse the alphabetical letters or search a signed word above.

Regional variation: there may be regional variations of some ASL words across the regions of North America.

Inflection: most ASL words in the dictionary are a «base», but many of them are grammatically inflectable within ASL sentences.

Contextual meaning: These ASL signs in the dictionary may not mean the same in different contexts and/or ASL sentences. You will see some examples in video sentences.

ASL is very much alive and indefinitely constructable as any spoken language. The best way to use ASL right is to immerse in daily interaction with Deaf Ameslan people (ASLers).

For non-deaf or hard of hearing people, it is often a surprise to learn that there is more than a single sign language.

Today, there are anywhere up to 300 different types of sign language used around the world. Some are only used locally. Others are used by millions of people.

Most sign languages don’t aim to directly translate spoken words into signs you make with your hands either. Each is a true language, with its own vocabulary, grammar and syntax – often unrelated to those of oral languages spoken in the same region.

And yes, the position of the hands is important. Yet so are eyebrow position, eye position, body movement and much more besides. A little like tones in oral languages, their importance and the way they are used also vary between different sign languages.

It only takes a moment’s thought to realise that, with so much variation in oral forms of expression, wouldn’t it actually be more surprising if there was only one universal sign language?

The development of sign languages

Questions as to why there isn’t a single universal sign language only really make sense if you are picturing sign languages as a kind of helper aid “gifted” by hearing people to the deaf or hard of hearing.

However, in the real world, sign languages – almost universally – develop naturally among deaf or hard of hearing people and communities.

Even Charles Michel de l’Épée, often credited as being the “inventor” of one of the key ancestors of many modern sign languages – French Sign Language – actually overheard two deaf people using it first and then learned from them.

The origins of sign languages

Many of the sign languages spoken around the world today have their origins in:

- British Sign Language: the British manual alphabet reached a format which would be familiar to many signers today as early as 1720. However, manual alphabets had been in use in daily British life even by many hearing people for centuries previously – at least as early as 1570. This then spread through the British Commonwealth and beyond in the 19th century.

- French Sign Language: developed in the 1700s, French Sign Language was the root of American Sign Language and many other European sign languages.

- Unique origins: yet many others – including Chinese, Japanese, Indo-Pakistani and Levantine Arabic sign languages – have their own unique origins completely unrelated to French or British roots.

But by 1880, different thoughts began to take shape. In that year, plans were announced at the Second International Congress of Education of the Deaf in Milan to reduce and eventually remove sign language from classrooms in favour of lip reading and other oral-based methods.

Known as oralism, these rules – which largely prioritised the convenience of hearing people – remained essentially in effect until the 1970s.

Today, however, the various sign languages naturally developed around the world are increasingly recognised as official languages. They are the preferred method of communication for many millions of deaf and hard of hearing people worldwide.

How do sign languages compare with written or spoken languages?

Just like written or spoken languages, sign languages have their own sentence structures, grammatical organisation and vocabulary. The way the hands are positioned in relation to the body can be almost important as the sign itself, for instance.

But signed languages don’t depend on the spoken or written languages of the same region. Nor do they usually mirror or represent them.

They even have some features which many spoken languages do not. For example, some signed languages have rules for indicating a question only has a yes or no answer.

Sign languages usually develop within deaf communities. Thus, they can be quite separate from the local oral language. The usual example given is that while American English and British English are largely identical, American Sign Language and British Sign Language have many differences.

However, spoken languages and signed languages do come into contact all the time. This means that oral languages do often have some influence on signed languages.

The different types of sign languages used around the world

If you are intending to do business with or advertise your products to deaf or hard of hearing people around the world, it is important to understand the type of sign language they prefer to use.

You can easily set up sign language interpreting services between a given oral language and a given signed language – as long as you know the specific language barrier you want to bridge the gap between.

Some of the most common sign languages in the world include:

British Sign Language, Auslan and New Zealand Sign Language (BANZSL)

The way in which British Sign Language (BSL), Australian Sign Language (Auslan) and New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL) relate to each other is illustrative of the dynamic differences between even closely related signed languages.

British Sign Language, codified in British schools for the deaf in the 1700s, spread around the world as the British Empire and Commonwealth did. This included reaching both Australia and New Zealand.

Thus, New Zealand Sign Language and Auslan, Australian Sign Language, share the same manual alphabet, grammar and much of the same lexicon (that is to say the same signs) as BSL. So much so that a single phrase – BANZSL – was coined to represent them as a single language with three dialects.

1) Differences between dialects

But even within BANZSL, all three dialects of which evolved from the same roots, there are differences.

For example, a key difference between New Zealand Sign Language and the other dialects is that NZSL includes signs for Māori words. It is also heavily influenced by its Auslan roots.

Auslan is itself influenced by Irish Sign Language (which in turn, derives from a French Sign Language root).

2) Differences within dialects

Plus, within each of these dialects, there are other dialects, variants and even what might be considered accents.

Within Auslan, for instance, some dialects might include features taken from Indigenous Australian sign languages which are completely unrelated to Auslan.

Other variants are regional. Certain signs used by BSL speakers in Scotland are unlikely to be understood by BSL speakers in southern England, for instance.

Another example is the city of Manchester in England, whose BSL-speaking population often use their own signed numbering system.

3) Differences within regions

Despite the implications of the names, languages such as British Sign Language or Australian Sign Language are also not the only signed languages used in Britain or Australia.

Many Indigenous Australian groups have their own sign languages. Within the UK, while around 145 000 people have BSL as their first or preferred language, others prefer different ways of communicating.

For example, Sign-Supported English (SSE) is a signed language which uses many of the same signs as BSL but which is designed to be used in support of spoken English. Thus, it tends to follow the same grammatical rules as the oral language instead of those of BSL.

French Sign Language (LSF)

French Sign Language (LSF – Langue des Signes Française) is another origin point for many of the world’s most-used sign languages. It arose amongst the deaf community in Paris and was codified by Charles Michel de l’Épée in the 1770s.

Although de l’Epee added a whole host of extra and often overly complex rules to the existing system, he did at least popularise the idea that sign languages were actual languages – to the point they were accepted by educators up until the rise of oralism.

Today, LSF is spoken by around 100 000 people in France as their first or preferred language. It has also had a significant impact on the development of ASL, Irish Sign Language and Russian Sign Language among many others.

However, again, it would be a mistake to assume that French Sign Language is simply used everywhere French is spoken. Many French-speaking regions have their own sign languages, including:

- Canada: has LSQ (la Langue des Signes Québécois), also referred to as Quebec Sign Language or French Canadian Sign Language, in its francophone regions and ASL (American Sign Language) in its anglophone parts.

- Belgium: has Flemish Belgian Sign Language and French Belgian Sign Language.

There are also numerous regional dialects even within France. These include Southern French Language, also known as Marseilles Sign Language.

American Sign Language (ASL)

American Sign Language borrows a large number of its grammatical laws from LSF, French Sign Language. But it combines them with local signs first used in America.

Today, anywhere from 250 000 to 500 000 use ASL as their preferred or first language. This is because, as well as being widely used by deaf and hard of hearing people in the United States, the language is also used in:

- English-speaking parts of Canada

- Parts of West Africa

- Parts of South-East Asia

Irish Sign Language (ISL)

Irish Sign Language also derives from LSF, French Sign Language. There are certainly influences from the BSL spoken in nearby regions, but ISL remains its own language.

Somewhere around 5000 deaf and hard of hearing people in the Republic of Ireland, as well as some in Northern Ireland, have ISL as their first or preferred language

A dialect difference almost unique to ISL is that which once existed between male and female ISL speakers. This came about through deaf or hard of hearing Irish Catholic students who leaned in schools which operated on lines of gender segregation.

These differences are almost entirely absent from modern ISL. Yet they are one more illustration of the way signed languages can develop in different ways among different groups from the same root.

Japanese Sign Language (JSL)

It has been said that Japanese Sign Language (Nihon Shuwa, 日本手話) reflects oral Japanese more closely than British Sign Language or American Sign Language reflect spoken English.

Speakers of JSL often mouth the way Japanese characters are spoken orally to make it clear which sign they are using. This is an important distinction from languages like ASL or BSL, where gestures and facial expressions are often more important.

Somewhere around 60 000 of the 300 000 deaf or hard of hearing people in Japan use JSL and there are several regional dialects. Many of the 200 000 or more others use:

- Taiou Shuwa: Sign-Supported Speech which works in something of the same manner as Sign-Supported English.

- Chuukan Shuwa: contact sign language. These languages include both oral and manual parts. The “contact” refers to the way they develop in the space where manual and oral languages come into contact.

Chinese Sign Language (CSL or ZGS)

Chinese Sign Language (CSL, written as 中国手语 in simplified Chinese and 中國手語 in traditional Chinese) is sometimes abbreviated as ZGS because of the Hanyu Pinyin romanised name of the language, Zhōngguó Shǒuyǔ.

The History of Chinese Sign Language

Although in recent years Chinese Sign Language has started to become more accepted in China, it remains unknown how many deaf or hard of hearing in the country actually use or prefer it.

This is largely because, up until very recently, many deaf Chinese children were taught in special schools using an oralist approach. This practice was strictly encouraged for the last half-century or more.

However, throughout the time when the oralist approach was the only standard in Chinese education for the deaf, CSL was still spread through smaller schools and workshops in various communities.

Today, there are around 20 million deaf or hard of hearing people in China. It’s estimated that around 1 in 20 or possibly more use CSL.

Chinese Sign Language – a unique language

Chinese Sign Language is a language isolate, meaning it is a natural language which has no other antecedents.

The language does have some parallels with oral Chinese. For example, there are two different signs for “older brother” and “younger brother”. This mirrors the fact that there are distinct words for each in oral Chinese too, instead of a generic word for “brother”.

CSL also includes pictorial representations as part of the language. This includes gesturing the use of chopsticks as the sign for eat.

Is there a universal sign language?

Strictly speaking, yes. International Sign – sometimes referred to as Gestuno, International Sign Pidgin or International Gesture – is a theoretically universal sign language used at the Deaflympics and other international deaf events.

That said, International Sign has been criticised for drawing heavily from European and North American sign languages at the possible expense of deaf and hard of hearing people from other parts of the world.

International Sign also may not, strictly speaking, meet the requirements for being counted a true language. It has recently been argued that International Sign is more like a complex pidgin – a term often used to describe a somewhat simplified form of communication developed between groups which speak different languages – rather than a complete language in and of itself.

International Sign Language Day

International Sign Language Day takes place every year on September 23rd. If nothing else this year, it’s worth thinking a little about how signed communication really works.

The differences between the sign languages spoken around the world are just as diverse and intriguing as those between spoken languages.

Do you need to set up sign language interpreting for your physical or virtual event, appointment or business meeting?

Asian Absolute works with individuals and businesses in every industry to bridge language gaps both spoken and signed.

Let’s talk. Get a free quote with zero obligation or more information today.

Let’s take a trip around the world to explore sign languages, their stories and their finger alphabets. The journey to communicating globally begins here!

Sign language is a visual means of communicating through hand signals, gestures, facial expressions, and body language.

It’s the main form of communication for the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing community, but sign language can be useful for other groups of people as well. People with disabilities including Autism, Apraxia of speech, Cerebral Palsy, and Down Syndrome may also find sign language beneficial for communicating.

And as you will see in the different languages below, it has even had other uses throughout history.

Not a Universal Language

There is no single sign language used around the world. Like spoken language, sign languages developed naturally through different groups of people interacting with each other, so there are many varieties. There are somewhere between 138 and 300 different types of sign language used around the globe today.

Interestingly, most countries that share the same spoken language do not necessarily have the same sign language as each other. English for example, has three varieties: American Sign Language (ASL), British Sign Language (BSL) and Australian Sign Language (Auslan).

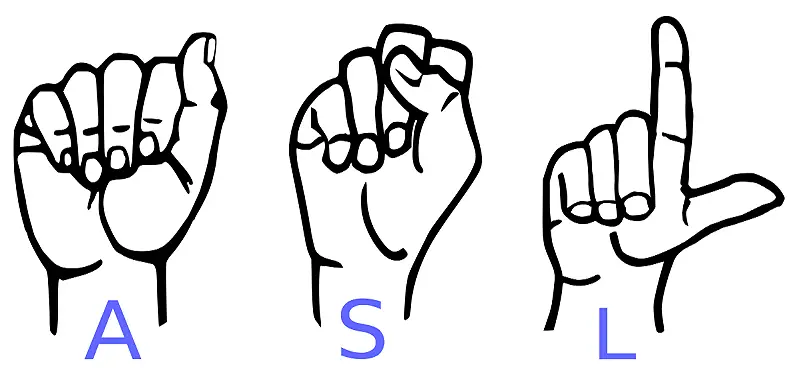

Basics of Alphabets and Fingerspelling

Most people start their sign language journey by learning the A-Z or alphabet equivalent in sign form.

The use of the hands to represent individual letters of a written alphabet is called ‘fingerspelling’. It’s an important tool that helps signers manually spell out names of people, places and things that don’t have an established sign.

For example, most sign languages have a specific sign for the word tree, but may not have a specific sign for oak, so o-a-k would be finger spelled to convey that specific meaning.

Of course, not every language uses the Latin alphabet like English, so their sign language alphabet differs as well. Some manual alphabets are one-handed, such as in ASL and French Sign Language, and others use two-hands, like BSL or Auslan. Though there are similarities between some of the different manual alphabets, each sign language has its own style and modifications, and remains unique.

Sign Language Alphabets from Around the World

American Sign Language (ASL)

Although ASL has the same alphabet as English, ASL is not a subset of the English language. American Sign Language was created independently and it has its own linguistic structure. (It is, in fact, descended from Old French Sign Language.)

Signs are also not expressed in the same order as words are in English. This is due to the unique grammar and visual nature of the sign language. ASL is used by roughly half a million people in the USA.

Learn the ASL alphabet by demonstration in this video, or with the chart below!

British, Australian and New Zealand Sign Language (BANZSL)

Sharing a sign language alphabet is British Sign Language, Australian Sign Language (Auslan) and New Zealand Sign Language. Unlike ASL, these alphabets use two hands, instead of one.

Chinese Sign Language (CSL)

Probably the most-used sign language in the world (but there is currently no data to confirm this), Chinese Sign Language uses the hands to make visual representations of written Chinese characters. The language has been developing since the 1950s.

French Sign Language (LSF)

French Sign Language is similar to ASL – since it is in fact the origin of ASL – but there are minor differences throughout. LSF also has a pretty fascinating history.

Japanese Sign Language (JSL) Syllabary

The Japanese Sign Language (JSL) Syllabary is based on the Japanese alphabet, which is made up of phonetic syllables. JSL is known as Nihon Shuwa in Japan.

Arabic Sign Language

The Arab sign-language family is a family of sign languages across the Arab Mideast. Data on these languages is somewhat scarce, but a few languages have been distinguished, including Levantine Arabic Sign Language.

Spanish Sign Language (LSE)

Spanish Sign Language is officially recognized by the Spanish Government. It is native to Spain, except Catalonia and Valencia. Many countries that speak Spanish do not use Spanish Sign Language! (See Mexican Sign Language below, for example.)

Mexican Sign Language (LSM)

Mexican Sign Language (‘lengua de señas mexicana’ or LSM) is different from Spanish, using different verbs and word order. The majority of people who use Mexican Sign Language reside in Mexico City, Guadalajara and Monterrey. Variation in this language is high between age groups and religious backgrounds.

Ukrainian Sign Language (USL)

Ukrainian Sign Language is derived from the broad family of French Sign Languages. It uses a one-handed manual alphabet of 33 signs, which make use of the 23 handshapes of USL.

Plains Sign Talk (Indigenous to North America)

In North America, Plains Sign Talk (also known as Plains Sign Language) is an Indigenous sign language that was once used between Plains Nations to support trade, tell stories, conduct ceremonies, and act as a daily communication language for Deaf people. It was used between Nations across central Canada, the central and western United States and northern Mexico.

Watch the video below to see an example of signing used in First Nations cultures in North America.

Learn How to Fingerspell like a Pro

Once you’ve learnt how to fingerspell each letter of the alphabet, it’s time to polish your form! Check out these tips to improve your fingerspelling:

- Pause between spelling individual words. This improves the comprehensibility of your signing.

- Keep your hand in one place while spelling each word. This can take practice, but it makes it much clearer for others to read back. An exception to this is when you are fingerspelling an acronym. In this instance, move each letter in a small circle to let people know not to read the letters together as a single word.

- If you are fingerspelling a word that has a double letter, bounce your hand between those two letters to indicate the repetition of that letter. You can also do this by sliding the letter slightly to the side to indication it should be doubled. It can be difficult to not bounce between every letter when first learning to fingerspell. You can use your free hand to hold your write to help steady it while practicing. Eventually, you’ll get used to keeping your hand steady by itself while fingerspelling.

- Keep your fingerspelling hand at the height of your shoulder. This is the most comfortable position for your signing and the other person’s reading.

- Keep your pace consistent. There is no need to race through when spelling a word. It’s more important that each letter is clear, and the overall rhythm is consistent.

Thanks for reading! To find out more about Ai-Media and our accessibility services, visit our website or get in touch with our friendly team.

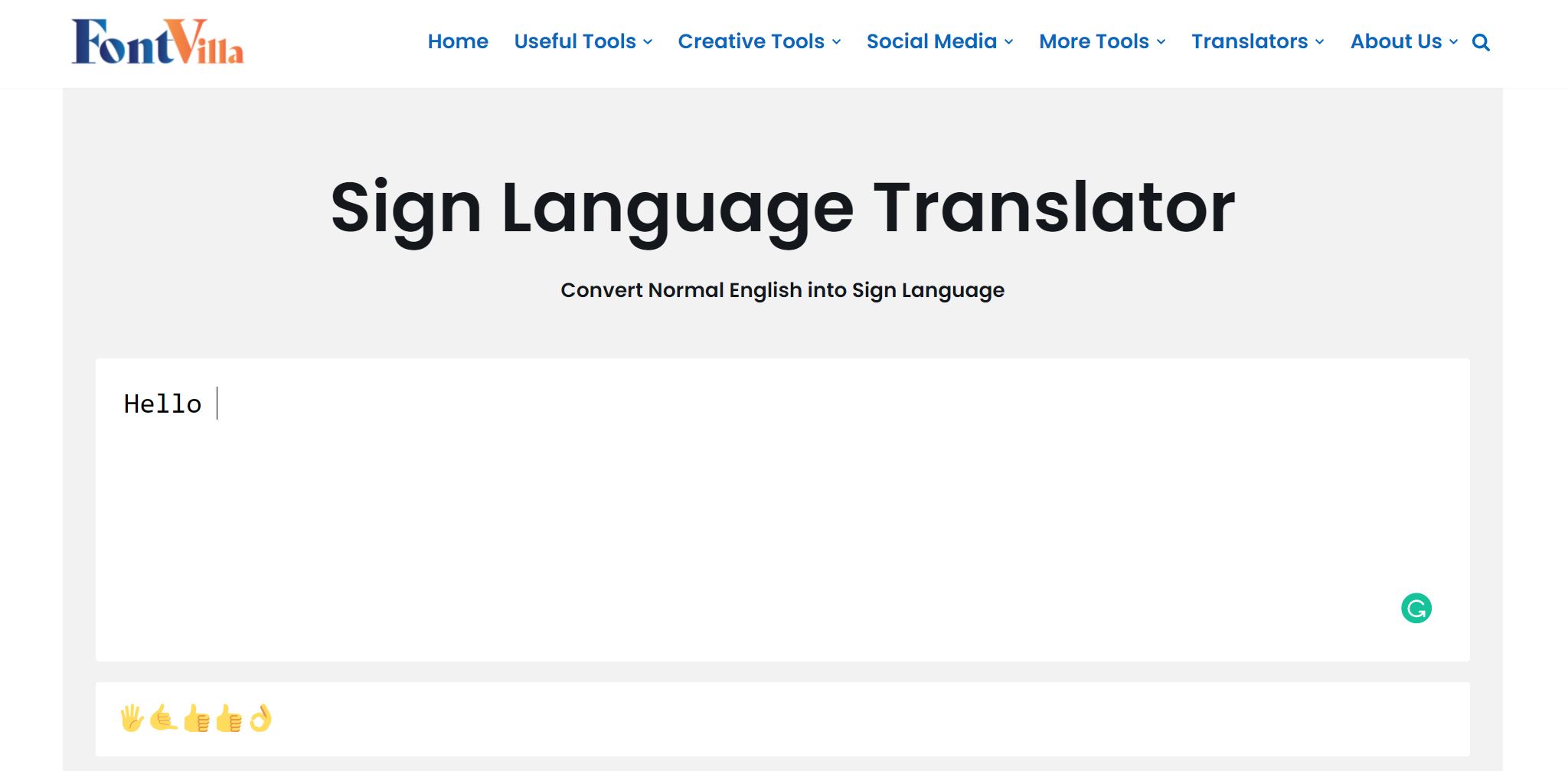

Convert Normal English into Sign Language

Your text will appear here..

What can Sign Language Translator do for you:

If you know someone that is deaf or can’t hear well, then the only way to effectively communicate with that person is by sign language. These days the American sign language is becoming more and more popular, people from around the world are starting to use this variation of sign language to effectively talk with the deaf.

It is perhaps the most effective way of communication for the deaf. Learning the American sign language translation however can be a difficult task, since it’s more of a motor skill than a cognitive one.

To learn and perfect your command over ASL to English translator you need to know when you’re wrong and when you’re right, so in other words, you require a teacher. Fontvilla, the text formatting website, realizes that not everyone can afford to take classes whether it’s a limitation of time or money.

So they have come up with an ingenious solution for anyone looking to improve or learn the American sign language. They have introduced the American sign language translators. A free online tool that anyone can use to convert normal sentences from English to sign language.

ASL translator and Fontvilla:

Fontvilla is a great website filled with hundreds of tools to modify, edit and transform your text. It works across all platforms and the converters and translators offered by Fontvilla are in a league of their own.

They’re super easy to use and are really fast. Fontvilla has tons and tons of converters ranging from converting text to bold or transforming the font of your text into anything you want. It’s the ultimate hub for customizing and personalizing your text. With Fontvilla, you can convert plain old boring text into something spectacular.

Wingdings Translator

Fontvilla has recently launched a brand new online translator known as the ASL translator, as the name suggests is an online tool that can be used to transform English sentences translation to sign language.

How it works:

Once you write the text in the dialog box and press enter all your words will be processed by Fontvilla’s translating algorithm, the results of which will be shown in the form of images of hands.

This will show you how to orient your hands and how to communicate the sentence in sign language. The images displayed are in such a format that you can easily copy them and paste them into any website, social media platform, or offline document that you wish.

To wrap it all up:

- Type the text you want in Sign Language Translator

- You will see fonts below

- Copy any font you want to use

- Paste it where you want and enjoy it

How to use it:

Using the online ASL translator is really easy. It’s just a simple copy and paste based tool. Once you open up the Fontvilla website you will have to type the text, that you want to convert, into a dialog box or you will have to copy the text and paste it into the box.

Braille Translator

Just press enter or the convert button and your text will be instantly converted into American sign language images. Now you can copy these images and paste them wherever you want or you can simply learn the hand gestures this way by mimicking the results.

Benefits:

As you can probably assume a tool like this can be used for a variety of purposes. It has far-reaching benefits. It is the ultimate tool to learn and improve your sign language skills. An essential language that everyone should know. The best part of this online ASL translator is that it can act as a teacher of sorts.

You can type the sentence you want to communicate and check to see if you’re right or wrong. Furthermore, there aren’t any time limitations associated with this online translator. Since it’s a web-based tool you can access it anywhere and at any time.

In this busy life, hardly anyone can take out the time from their day to attend extra classes and learn a new language therefore it is the best translator and teacher for learning ASL.

Another great feature of this ASL online translator is that it’s free. People don’t have to spend a dime to use this great English to an ASL translator. This means that you can learn ASL for free and at any time that you want.

Old English Translator

The online translator is really fast too, it can display your results in a matter of milliseconds. When you press the convert button the extremely efficient algorithm instantly converts the words into hand gestures that you can use to communicate with the deaf.

The ultimate tool for communication:

It’s the ultimate tool for communicating with the deaf, not only can it be used as a teacher to learn the American sign language. It can also be used in situations where you really need a translator. Say for example you need to talk to a deaf person or a person that is hard of hearing but you can’t since you don’t know how to translate English to sign language.

In situations like these, you can simply use this online translator and convert the sentence that you want to speak into ASL. it doesn’t matter if you have learned ASL or not since you can use this tool to talk to him effectively.

For this, all you need to have is an internet connection and you’re good to go. Connect to the Fontville website and choose the English translate to ASL translator from the hundreds of translating options that Fontvilla offers and you’re good to go.

Who should use the ASL translator:

Anybody and everybody who wishes to learn the language or wishes to effectively communicate with the deaf. It’s an essential tool that everybody should have in their arsenal.

Two sign language Interpreters working as a team for a school.

A sign language (also signed language) is a language which uses manual communication, body language, and lip patterns instead of sound to convey meaning—simultaneously combining hand shapes, orientation and movement of the hands, arms or body, and facial expressions to fluidly express a speaker’s thoughts. Signs often represent complete ideas, not only words. However, in addition to accepted gestures, mime, and hand signs, sign language often includes finger spelling, which involves the use of hand positions to represent the letters of the alphabet.

Although often misconceived of as an imitation or simplified version of oral language, linguists such as William Stokoe have found sign languages to be complex and thriving natural languages, complete with their own syntax and grammar. In fact, the complex spatial grammars of sign languages are markedly different than that of spoken language.

Sign languages have developed in circumstances where groups of people with mutually unintelligible spoken languages found a common base and were able to develop signed forms of communication. A well-known example of this is found among Plains Indians, whose lifestyle and environment was sufficiently similar despite no common base in their spoken languages, that they were able to find common symbols that were used to communicate even complex narratives among different tribes.

Sign languages commonly develop in deaf communities, which include people who are deaf or hard of hearing, friends and families of deaf people, as well as interpreters. In many cases, various signed «modes» of spoken languages have been developed, such as Signed English and Warlpiri Sign Language. Sign language differs from one region to another, just as do spoken languages, and are mutually unintelligible. Hundreds of sign languages are in use around the world and are at the core of local deaf cultures. The use of these languages has enabled the deaf to be recognized as intelligent, educable people who are capable of living life as fully and with as much value as anyone else. However, much controversy exists over whether teaching deaf children sign language is ultimately more beneficial than methods that allow them to understand oral communication, such as lip-reading, since this enables them to participate more directly and fully in the wider society. Nonetheless, for those people who remain unable to produce or understand oral language, sign language provides a way to communicate within their society as full human beings with a clear cultural identity.

History and development of sign language

On the whole, deaf sign languages are independent of oral languages and follow their own paths of development, even in situations where there may be a common spoken language. Because they developed on their own, British Sign Language and American Sign Language are quite different and mutually unintelligible, even though the hearing people of Britain and America share the same oral language. American Sign Language does have some similarities to French Sign Language, due to its early influences. When people using different signed languages meet, however, communication can be easier than when people of different spoken languages meet. This is not because sign languages are universal, but because deaf people may be more patient when communicating, and are comfortable including gesture and mime.[1]

Generally, each spoken language has a sign language counterpart because each linguistic population contains deaf members who generated a sign language. Geographical or cultural forces will isolate populations and lead to the generation of different and distinct spoken languages; the same forces operate on signed languages, therefore they tend to maintain their identities through time in roughly the same areas of influence as the local spoken languages. This occurs even though sign languages have little or no relation to the spoken languages of the lands in which they arise. There are notable exceptions to this pattern, however, as some geographic regions sharing a spoken language have multiple, unrelated signed languages. Variations within a «national» sign language can usually be correlated to the geographic location of (residential) schools for the deaf.

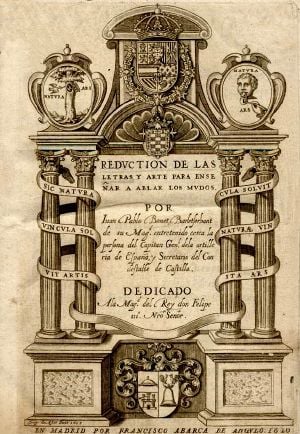

Juan Pablo Bonet, Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos (Madrid, 1620).

The written history of sign language began in the seventeenth century in Spain. In 1620, Juan Pablo Bonet published Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos (Reduction of letters and art for teaching dumb people to speak) in Madrid. It is considered the first modern treatise of phonetics and speech therapy, setting out a method of oral education for the deaf people by means of the use of manual signs in the form of a manual alphabet to improve the communication of deaf people.

From the language of signs of Bonet, Charles-Michel de l’Épée published his alphabet in the eighteenth century, which has remained basically unchanged until the present time. In 1755, Abbé de l’Épée founded the first public school for deaf children in Paris. His lessons were based upon his observations of deaf people signing with hands in the streets of Paris. Synthesized with French grammar, it evolved into the French Sign Language.

Laurent Clerc, a graduate and former teacher of the French School, went to the United States with Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet to found the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817.[2] Others followed. In 1817, Clerc and Gallaudet founded the American Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb (now the American School for the Deaf). Gallaudet’s son, Edward Miner Gallaudet, founded the first college for the deaf in 1864 in Washington, DC, which in 1986, became Gallaudet University, the only liberal arts university for the deaf in the world.

Engravings of Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos:[3]

-

A.

-

B, C, D.

-

E, F, G.

-

H, I, L.

-

M, N.

-

O, P, Q.

-

R, S, T.

-

V, X, Y, Z.

2007 Chinese Taipei Olympic Day Run in Taipei City: Deaflympics Taipei 2009 Easy Sign Language Section.

International Sign, formerly known as «Gestuno,» was created in 1973, to enhance communication among members of the deaf community throughout the world. It is an artificially constructed language and though some people are reported to use it fluently, it is more of a pidgin than a fully formed language. International Sign is used mainly at international Deaf events such as the Deaflympics and meetings of the World Federation of the Deaf.[4]

Linguistics of sign

In linguistic terms, sign languages are rich and complex, despite the common misconception that they are not «real languages.» William Stokoe started groundbreaking research into sign language in the 1960s. Together with Carl Cronenberg and Dorothy Casterline, he wrote the first sign language dictionary, A Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles.[5] It was during this time he first began to refer to sign language not just as sign language or manual communication, but as «American Sign Language,» or ASL. This ground-breaking dictionary listed signs and explained their meanings and usage, and gave a linguistic analysis of the parts of each sign. Since then, linguists have studied many sign languages and found them to have every linguistic component required to be classified as true languages.

Did you know?

Sign languages are complex and contain every linguistic component required to be classified as true languages

Sign languages are not merely pantomime, but are made of largely arbitrary signs that have no necessary visual relationship to their referent, much as most spoken language is not onomatopoeic. Nor are they a visual renditions of an oral language. They have complex grammars of their own, and can be used to discuss any topic, from the simple and concrete to the philosophical and abstract. For example, in terms of syntax, ASL shares more with spoken Japanese than it does with English.[6]

The American manual alphabet in photographs

Sign languages, like oral languages, organize elementary, meaningless units (phonemes; once called cheremes in the case of sign languages) into meaningful semantic units. The elements of a sign are Hand shape (or Handform), Orientation (or Palm Orientation), Location (or Place of Articulation), Movement, and Non-manual markers (or Facial Expression), summarized in the acronym HOLME. Signs, therefore, are not an alphabet but rather represent words or other meaningful concepts.

In addition to such signs, most sign languages also have a manual alphabet. This is used mostly for proper names and technical or specialized vocabulary. The use of fingerspelling was once taken as evidence that sign languages are simplified versions of oral languages, but it is merely one tool in complex and vibrant languages. Fingerspelling can sometimes be a source of new signs, which are called lexicalized signs.

Common linguistic features of deaf sign languages are extensive use of classifiers, a high degree of inflection, and a topic-comment syntax. Many unique linguistic features emerge from sign languages’ ability to produce meaning in different parts of the visual field simultaneously. For example, the recipient of a signed message can read meanings carried by the hands, the facial expression, and the body posture at the same time. This is in contrast to oral languages, where the sounds that comprise words are mostly sequential (tone being an exception).

Spatial grammar and simultaneity

Sign languages are able to capitalize on the unique features of the visual medium. Oral language is linear and only one sound can be made or received at a time. Sign language, instead, is visual; hence, a whole scene can be taken in at once. Information can be loaded into several channels and expressed simultaneously.

As an illustration, in English one could utter the phrase, «I drove here.» To add information about the drive, one would have to make a longer phrase or even add a second, such as, «I drove here along a winding road,» or «I drove here. It was a nice drive.» However, in American Sign Language, information about the shape of the road or the pleasing nature of the drive can be conveyed simultaneously with the verb «drive» by inflecting the motion of the hand, or by taking advantage of non-manual signals such as body posture and facial expression, at the same time that the verb «drive» is being signed. Therefore, in English the phrase «I drove here and it was very pleasant» is longer than «I drove here,» in American Sign Language the two may be the same length.

Written forms of sign languages

Sign languages are not often written, and documented written systems were not created until after the 1960s. Most deaf signers read and write the oral language of their country. However, there have been several attempts at developing scripts for sign language. These have included both «phonetic» systems, such as Hamburg Sign Language Notation System, or HamNoSys,[7] and SignWriting, which can be used for any sign language, as well as «phonemic» systems such as the one used by William Stokoe in his 1965 Dictionary of American Sign Language, which are designed for a specific language.

The phonemic systems of oral languages are primarily sequential: That is, the majority of phonemes are produced in a sequence one after another, although many languages also have non-sequential aspects such as tone. As a consequence, traditional phonemic writing systems are also sequential, with at best diacritics for non-sequential aspects such as stress and tone. Sign languages have a higher non-sequential component, with many «phonemes» produced simultaneously. For example, signs may involve fingers, hands, and face moving simultaneously, or the two hands moving in different directions. Traditional writing systems are not designed to deal with this level of complexity.

The Stokoe notation is sequential, with a conventionalized order of a symbol for the location of the sign, then one for the hand shape, and finally one (or more) for the movement. The orientation of the hand is indicated with an optional diacritic before the hand shape. When two movements occur simultaneously, they are written one atop the other; when sequential, they are written one after the other. Stokoe used letters of the Latin alphabet and Arabic numerals to indicate the handshapes used in fingerspelling, such as «A» for a closed fist, «B» for a flat hand, and «5» for a spread hand; but non-alphabetic symbols for location and movement, such as «[]» for the trunk of the body, «×» for contact, and «^» for an upward movement.

SignWriting, developed in 1974 by Valerie Sutton, is highly featural and visually iconic, both in the shapes of the characters—which are abstract pictures of the hands, face, and body—and in their spatial arrangement on the page, which does not follow a sequential order like the letters that make up written English words. Being pictographic, it is able to represent simultaneous elements in a single sign. Neither the Stokoe nor HamNoSys scripts were designed to represent facial expressions or non-manual movements, both of which SignWriting accommodates easily.

Use of signs in hearing communities

While not full languages, many elaborate systems of manual communication have developed in situations where speech is not practical or permitted, such as cloistered religious communities, scuba diving, television recording studios, loud workplaces, stock exchanges, in baseball, while hunting (by groups such as the Kalahari bushmen), or in the game Charades. In Rugby Union, the referee uses a limited but defined set of signs to communicate his/her decisions to the spectators.

On occasion, where there are enough deaf people in the area, a deaf sign language has been taken up by an entire local community. Famous examples of this include Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language in the U.S., Kata Kolok in a village in Bali, Adamorobe Sign Language in Ghana, and Yucatec Maya sign language in Mexico. In such communities, deaf people are not socially disadvantaged.

Many Australian Aboriginal sign languages arose in a context of extensive speech taboos, such as during mourning and initiation rites. They are or were especially highly developed among the Warlpiri, Warumungu, Dieri, Kaytetye, Arrernte, Warlmanpa, and are based on their respective spoken languages.

Sign language has also been used to facilitate communication among peoples of mutually intelligible languages. In the case of Chinese and Japanese, where the same body of written characters is used but with different pronunciation, communication is possible through watching the «speaker» trace the mutually understood characters on the palm of their hand.

A pidgin sign language arose among tribes of American Indians in the Great Plains region of North America. Although the languages of the Plains Indians were unrelated, their way of life and environment had many common features. They were able to find common symbols which were then used to communicate even complex narratives among different tribes. For example, the gesture of brushing long hair down the neck and shoulders signified a woman, two fingers astride the other index finger represented a person on horseback, a circle drawn against the sky meant the moon, and so forth. Unlike other sign languages developed by hearing people, it shares the spatial grammar of deaf sign languages.

Home sign

Sign systems are sometimes developed within a single family. For instance, when hearing parents with no sign language skills have a deaf child, an informal system of signs will naturally develop, unless repressed by the parents. The term for these mini-languages is home sign (sometimes homesign or kitchen sign).

Home sign arises due to the absence of any other way to communicate. Within the span of a single lifetime and without the support or feedback of a community, the child is forced to invent signals to facilitate the meeting of his or her communication needs. Although this kind of system is grossly inadequate for the intellectual development of a child and does not meet the standards linguists use to describe a complete language, it is a common occurrence.

Benefits

For deaf and hard of hearing students, there have been long standing debates regarding the teaching and use of sign language versus oral methods of communication and lip reading. Proficiency in sign language gives deaf children a sense of cultural identity, which enables them to bond with other deaf individuals. This can lead to greater self-esteem and curiosity about the world, both of which enrich the student academically and socially. Certainly, the development of sign language showed that deaf-mute children were educable, opening educational opportunities at the same level as those who hear.

Notes

- ↑ David Bar-Tzur, International Gesture:Principles and Gestures, July 13, 2002. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ↑ Loida Canlas, Laurent Clerc: Apostle to the Deaf People of the New World Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center, Gallaudet University. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ↑ Juan Pablo Bonet, Reducción de las Letras y Arte para Enseñar a Hablar a los Mudos (Editorial Cepe, 1992, ISBN 978-8478690718).

- ↑ Jolanta Lapiak, Gestuno (a.k.a International Sign Language) HandSpeak. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ↑ William C. Stokoe, Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles (Linstok Press, 1976, ISBN 978-0932130013).

- ↑ Karen Nakamura, About Japanese Sign Language Deaf Resource Library. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ↑ HamNoSys DGS Corpus. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aronoff, Mark, and Janie Rees-Miller. The Handbook of Linguistics. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2020. ISBN 978-1119302070

- Bonet, Juan Pablo. Reducción de las Letras y Arte para Enseñar a Hablar a los Mudos. Editorial Cepe, 1992. ISBN 978-8478690718

- Emmorey, Karen, Harlan L. Lane, Ursula Bellugi, and Edward S. Klima. The Signs of Language Revisited: An Anthology to Honor Ursula Bellugi and Edward Klima. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2000. ISBN 978-0585356419

- Groce, Nora Ellen. Everyone Here Spoke Sign Language: Hereditary Deafness on Martha’s Vineyard. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0674270404

- Kendon, Adam. Sign languages of Aboriginal Australia Cultural, Semiotic, and Communicative Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 0521360080

- Klima, Edward S., and Ursula Bellugi. The Signs of Language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0674807952

- Lane, Harlan L. The Deaf Experience Classics in Language and Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0674194601

- Lane, Harlan L. When the Mind Hears: A History of the Deaf. New York: Random House, 1984. ISBN 0394508785

- Lucas, Ceil. Multicultural Aspects of Sociolinguistics in Deaf Communities: Sociolinguistics in Deaf Communities, vol. 2. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-1563680465

- Padden, Carol, and Tom Humphries. Deaf in America: Voices from a Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0674194236

- Poizner, Howard. What the Hands Reveal about the Brain. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0262161053

- Sacks, Oliver W. Seeing Voices: A Journey into the Land of the Deaf. Vintage, 2000. ISBN 978-0375704079

- Stiles, Joan, Mark Kritchevsky, and Ursula Bellugi. Spatial Cognition: Brain Bases and Development. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates, 1988. ISBN 978-0805800463

- Stokoe, William C. Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles. Linstok Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0932130013

- Stokoe, William C. Sign Language Structure: An Outline of the Visual Communication Systems of the American Deaf. Linstok Press, 1978. ISBN 978-0932130037

- Tomkins, William. Indian Sign Language. Dover Publications, 1969. ISBN 978-0486220291

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ABC Slider Learn ASL fingerspelling

- ASL Browser Video dictionary of ASL signs

- 32 Uses and Benefits of American Sign Language (ASL) for Silent Communications

- Why Is It Important to Learn American Sign Language (ASL)?

- Top 26 Resources for Learning Sign Language

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Sign_language history

- History_of_the_deaf history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Sign language»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.