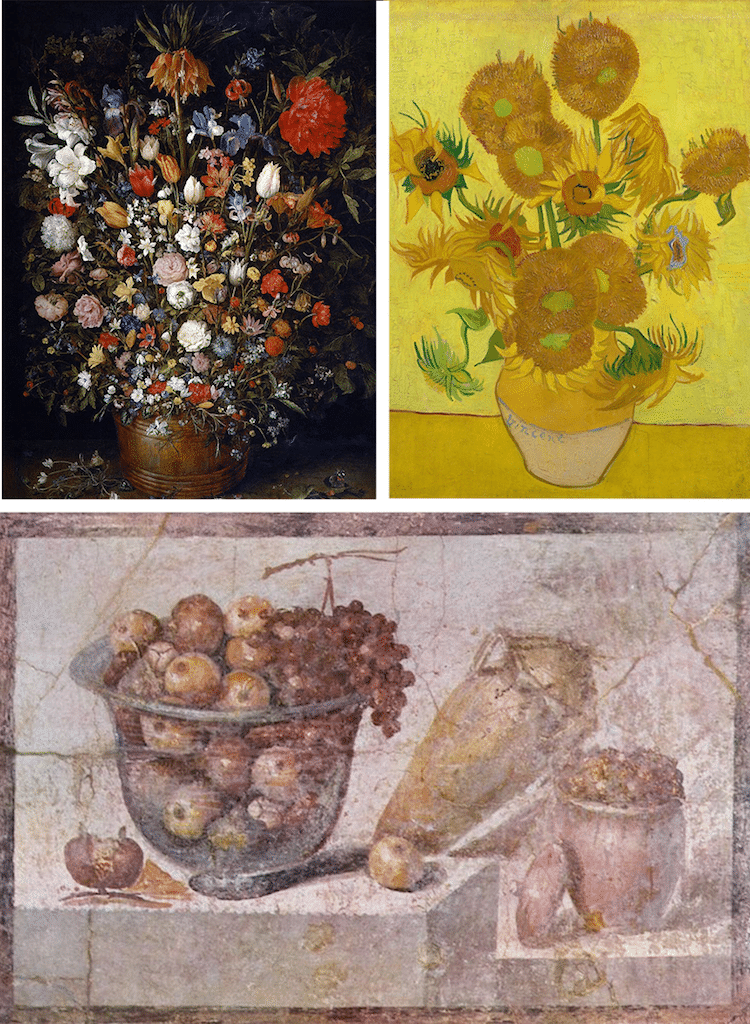

Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625), Bouquet (1599). Some of the earliest examples of still life were paintings of flowers by Netherlandish Renaissance painters. Still-life painting (including vanitas), as a particular genre, achieved its greatest importance in the Golden Age of Netherlandish art (ca. 1500s–1600s).

A still life (plural: still lifes) is a work of art depicting mostly inanimate subject matter, typically commonplace objects which are either natural (food, flowers, dead animals, plants, rocks, shells, etc.) or man-made (drinking glasses, books, vases, jewelry, coins, pipes, etc.).[1]

With origins in the Middle Ages and Ancient Greco-Roman art, still-life painting emerged as a distinct genre and professional specialization in Western painting by the late 16th century, and has remained significant since then. One advantage of the still-life artform is that it allows an artist much freedom to experiment with the arrangement of elements within a composition of a painting. Still life, as a particular genre, began with Netherlandish painting of the 16th and 17th centuries, and the English term still life derives from the Dutch word stilleven. Early still-life paintings, particularly before 1700, often contained religious and allegorical symbolism relating to the objects depicted. Later still-life works are produced with a variety of media and technology, such as found objects, photography, computer graphics, as well as video and sound.

The term includes the painting of dead animals, especially game. Live ones are considered animal art, although in practice they were often painted from dead models. Because of the use of plants and animals as a subject, the still-life category also shares commonalities with zoological and especially botanical illustration. However, with visual or fine art, the work is not intended merely to illustrate the subject correctly.

Still life occupied the lowest rung of the hierarchy of genres, but has been extremely popular with buyers. As well as the independent still-life subject, still-life painting encompasses other types of painting with prominent still-life elements, usually symbolic, and «images that rely on a multitude of still-life elements ostensibly to reproduce a ‘slice of life‘«.[2] The trompe-l’œil painting, which intends to deceive the viewer into thinking the scene is real, is a specialized type of still life, usually showing inanimate and relatively flat objects.[3]

Antecedents and development[edit]

Still life on a 2nd-century mosaic, with fish, poultry, dates and vegetables from the Vatican museum

Still-life paintings often adorn the interior of ancient Egyptian tombs. It was believed that food objects and other items depicted there would, in the afterlife, become real and available for use by the deceased. Ancient Greek vase paintings also demonstrate great skill in depicting everyday objects and animals. Peiraikos is mentioned by Pliny the Elder as a panel painter of «low» subjects, such as survive in mosaic versions and provincial wall-paintings at Pompeii: «barbers’ shops, cobblers’ stalls, asses, eatables and similar subjects».[4]

Similar still life, more simply decorative in intent, but with realistic perspective, have also been found in the Roman wall paintings and floor mosaics unearthed at Pompeii, Herculaneum and the Villa Boscoreale, including the later familiar motif of a glass bowl of fruit. Decorative mosaics termed «emblema», found in the homes of rich Romans, demonstrated the range of food enjoyed by the upper classes, and also functioned as signs of hospitality and as celebrations of the seasons and of life.[5]

By the 16th century, food and flowers would again appear as symbols of the seasons and of the five senses. Also starting in Roman times is the tradition of the use of the skull in paintings as a symbol of mortality and earthly remains, often with the accompanying phrase Omnia mors aequat (Death makes all equal).[6] These vanitas images have been re-interpreted through the last 400 years of art history, starting with Dutch painters around 1600.[7]

The popular appreciation of the realism of still-life painting is related in the ancient Greek legend of Zeuxis and Parrhasius, who are said to have once competed to create the most lifelike objects, history’s earliest descriptions of trompe-l’œil painting.[8] As Pliny the Elder recorded in ancient Roman times, Greek artists centuries earlier were already advanced in the arts of portrait painting, genre painting and still life. He singled out Peiraikos, «whose artistry is surpassed by only a very few…He painted barbershops and shoemakers’ stalls, donkeys, vegetables, and such, and for that reason came to be called the ‘painter of vulgar subjects’; yet these works are altogether delightful, and they were sold at higher prices than the greatest [paintings] of many other artists.»[9]

Middle Ages and Early Renaissance[edit]

Hans Memling (1430–1494), Vase of Flowers (1480), Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. According to some scholars the Vase of Flowers is filled with religious symbolism.[10]

By 1300, starting with Giotto and his pupils, still-life painting was revived in the form of fictional niches on religious wall paintings which depicted everyday objects.[11] Through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, still life in Western art remained primarily an adjunct to Christian religious subjects, and convened religious and allegorical meaning. This was particularly true in the work of Northern European artists, whose fascination with highly detailed optical realism and symbolism led them to lavish great attention on their paintings’ overall message.[12] Painters like Jan van Eyck often used still-life elements as part of an iconographic program.[citation needed]

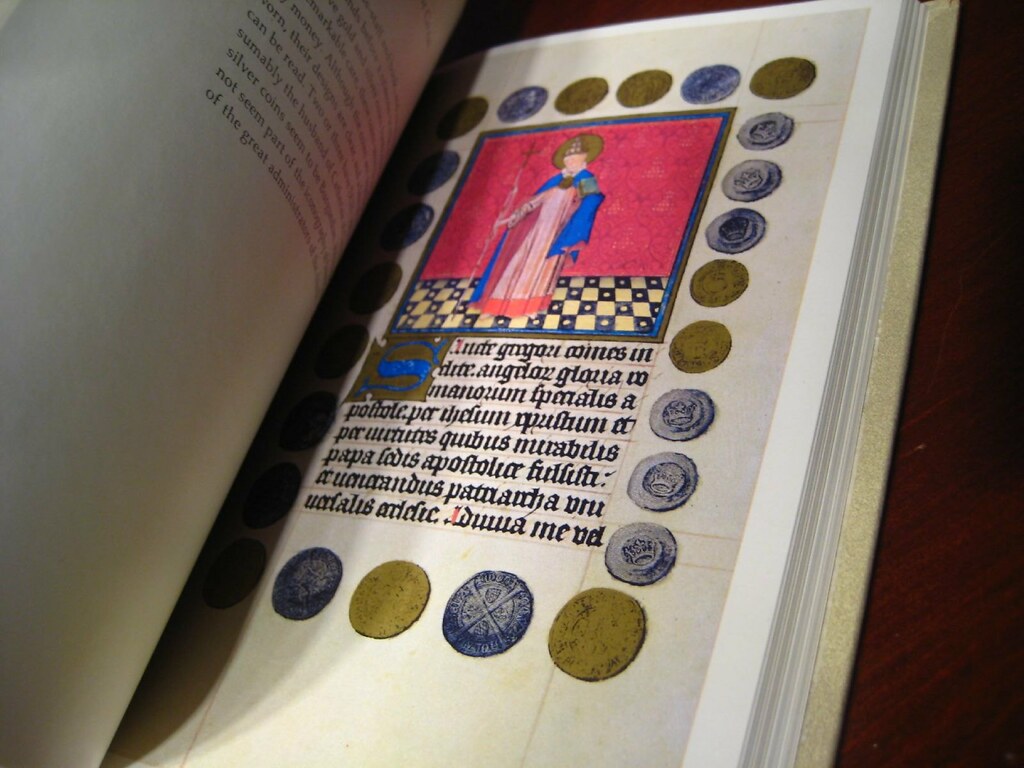

In the late Middle Ages, still-life elements, mostly flowers but also animals and sometimes inanimate objects, were painted with increasing realism in the borders of illuminated manuscripts, developing models and technical advances that were used by painters of larger images. There was considerable overlap between the artists making miniatures for manuscripts and those painting panels, especially in Early Netherlandish painting. The Hours of Catherine of Cleves, probably made in Utrecht around 1440, is one of the outstanding examples of this trend, with borders featuring an extraordinary range of objects, including coins and fishing-nets, chosen to complement the text or main image at that particular point. Flemish workshops later in the century took the naturalism of border elements even further. Gothic millefleur tapestries are another example of the general increasing interest in accurate depictions of plants and animals. The set of The Lady and the Unicorn is the best-known example, designed in Paris around 1500 and then woven in Flanders.[citation needed]

The development of oil painting technique by Jan van Eyck and other Northern European artists made it possible to paint everyday objects in this hyper-realistic fashion, owing to the slow drying, mixing, and layering qualities of oil colours.[13] Among the first to break free of religious meaning were Leonardo da Vinci, who created watercolour studies of fruit (around 1495) as part of his restless examination of nature, and Albrecht Dürer who also made precise coloured drawings of flora and fauna.[14]

Petrus Christus’ portrait of a bride and groom visiting a goldsmith is a typical example of a transitional still life depicting both religious and secular content. Though mostly allegorical in message, the figures of the couple are realistic and the objects shown (coins, vessels, etc.) are accurately painted but the goldsmith is actually a depiction of St. Eligius and the objects heavily symbolic. Another similar type of painting is the family portrait combining figures with a well-set table of food, which symbolizes both the piety of the human subjects and their thanks for God’s abundance.[15] Around this time, simple still-life depictions divorced of figures (but not allegorical meaning) were beginning to be painted on the outside of shutters of private devotional paintings.[9] Another step toward the autonomous still life was the painting of symbolic flowers in vases on the back of secular portraits around 1475.[16] Jacopo de’ Barbari went a step further with his Still Life with Partridge and Gauntlets (1504), among the earliest signed and dated trompe-l’œil still-life paintings, which contains minimal religious content.[17]

Later Renaissance[edit]

Sixteenth century[edit]

Though most still lifes after 1600 were relatively small paintings, a crucial stage in the development of the genre was the tradition, mostly centred on Antwerp, of the «monumental still life», which were large paintings that included great spreads of still-life material with figures and often animals. This was a development by Pieter Aertsen, whose A Meat Stall with the Holy Family Giving Alms (1551, now Uppsala) introduced the type with a painting that still startles. Another example is «The Butcher Shop» by Aertsen’s nephew Joachim Beuckelaer (1568), with its realistic depiction of raw meats dominating the foreground, while a background scene conveys the dangers of drunkenness and lechery. The type of very large kitchen or market scene developed by Pieter Aertsen and his nephew Joachim Beuckelaer typically depicts an abundance of food with a kitchenware still life and burly Flemish kitchen-maids. A small religious scene can often be made out in the distance, or a theme such as the Four Seasons is added to elevate the subject. This sort of large-scale still life continued to develop in Flemish painting after the separation of the North and South, but is rare in Dutch painting, although other works in this tradition anticipate the «merry company» type of genre painting.[18]

Gradually, religious content diminished in size and placement in this type of painting, though moral lessons continued as sub-contexts.[19] One of the relatively few Italian works in the style, Annibale Carracci’s treatment of the same subject in 1583, Butcher’s Shop, begins to remove the moral messages, as did other «kitchen and market» still-life paintings of this period.[20] Vincenzo Campi probably introduced the Antwerp style to Italy in the 1570s. The tradition continued into the next century, with several works by Rubens, who mostly sub-contracted the still-life and animal elements to specialist masters such as Frans Snyders and his pupil Jan Fyt. By the second half of the 16th century, the autonomous still life evolved.[21]

The 16th century witnessed an explosion of interest in the natural world and the creation of lavish botanical encyclopædias recording the discoveries of the New World and Asia. It also prompted the beginning of scientific illustration and the classification of specimens. Natural objects began to be appreciated as individual objects of study apart from any religious or mythological associations. The early science of herbal remedies began at this time as well, which was a practical extension of this new knowledge. In addition, wealthy patrons began to underwrite the collection of animal and mineral specimens, creating extensive cabinets of curiosities. These specimens served as models for painters who sought realism and novelty. Shells, insects, exotic fruits and flowers began to be collected and traded, and new plants such as the tulip (imported to Europe from Turkey), were celebrated in still-life paintings.[22]

The horticultural explosion was of widespread interest in Europe and artist capitalized on that to produce thousands of still-life paintings. Some regions and courts had particular interests. The depiction of citrus, for example, was a particular passion of the Medici court in Florence, Italy.[23] This great diffusion of natural specimens and the burgeoning interest in natural illustration throughout Europe, resulted in the nearly simultaneous creation of modern still-life paintings around 1600.[24][25]

At the turn of the century the Spanish painter Juan Sánchez Cotán pioneered the Spanish still life with austerely tranquil paintings of vegetables, before entering a monastery in his forties in 1603, after which he painted religious subjects.[citation needed]

Sixteenth-century paintings[edit]

-

Pieter Aertsen, A Meat Stall with the Holy Family Giving Alms (1551), 123.3 × 150 cm (48.5 × 59″)

-

-

Juan Sánchez Cotán (1560–1627), Still life with Quince, Cabbage, Melon and Cucumber, oil on canvas, 69 × 84.5 cm

-

Giovanni Ambrogio Figino, Metal Plate with Peaches and Vine Leaves (1591–94), panel, 21 × 30 cm, his only known still life

Seventeenth century[edit]

Prominent Academicians of the early 17th century, such as Andrea Sacchi, felt that genre and still-life painting did not carry the «gravitas» merited for painting to be considered great. An influential formulation of 1667 by André Félibien, a historiographer, architect and theoretician of French classicism became the classic statement of the theory of the hierarchy of genres for the 18th century:

Celui qui fait parfaitement des païsages est au-dessus d’un autre qui ne fait que des fruits, des fleurs ou des coquilles. Celui qui peint des animaux vivants est plus estimable que ceux qui ne représentent que des choses mortes & sans mouvement ; & comme la figure de l’homme est le plus parfait ouvrage de Dieu sur la Terre, il est certain aussi que celui qui se rend l’imitateur de Dieu en peignant des figures humaines, est beaucoup plus excellent que tous les autres …[26]

He who produces perfect landscapes is above another who only produces fruit, flowers or seafood. He who paints living animals is more estimable than those who only represent dead things without movement, and as man is the most perfect work of God on the earth, it is also certain that he who becomes an imitator of God in representing human figures, is much more excellent than all the others …».

Dutch and Flemish painting[edit]

Pieter Claesz (1597–1660), Still life with Musical Instruments (1623)

Still life developed as a separate category in the Low Countries in the last quarter of the 16th century.[27] The English term still life derives from the Dutch word stilleven while Romance languages (as well as Greek, Polish, Russian and Turkish) tend to use terms meaning dead nature. 15th-century Early Netherlandish painting had developed highly illusionistic techniques in both panel painting and illuminated manuscripts, where the borders often featured elaborate displays of flowers, insects and, in a work like the Hours of Catherine of Cleves, a great variety of objects. When the illuminated manuscript was displaced by the printed book, the same skills were later deployed in scientific botanical illustration; the Low Countries led Europe in both botany and its depiction in art. The Flemish artist Joris Hoefnagel (1542–1601) made watercolour and gouache paintings of flowers and other still-life subjects for the Emperor Rudolf II, and there were many engraved illustrations for books (often then hand-coloured), such as Hans Collaert’s Florilegium, published by Plantin in 1600.[28]

Around 1600 flower paintings in oils became something of a craze; Karel van Mander painted some works himself, and records that other Northern Mannerist artists such as Cornelis van Haarlem also did so. No surviving flower-pieces by them are known, but many survive by the leading specialists, Jan Brueghel the Elder and Ambrosius Bosschaert, both active in the Southern Netherlands.[29]

While artists in the North found limited opportunity to produce the religious iconography which had long been their staple—images of religious subjects were forbidden in the Dutch Reformed Protestant Church—the continuing Northern tradition of detailed realism and hidden symbols appealed to the growing Dutch middle classes, who were replacing Church and State as the principal patrons of art in the Netherlands. Added to this was the Dutch mania for horticulture, particularly the tulip. These two views of flowers—as aesthetic objects and as religious symbols— merged to create a very strong market for this type of still life.[30] Still life, like most Dutch art work, was generally sold in open markets or by dealers, or by artists at their studios, and rarely commissioned; therefore, artists usually chose the subject matter and arrangement.[31] So popular was this type of still-life painting, that much of the technique of Dutch flower painting was codified in the 1740 treatise Groot Schilderboeck by Gerard de Lairesse, which gave wide-ranging advice on colour, arranging, brushwork, preparation of specimens, harmony, composition, perspective, etc.[32]

The symbolism of flowers had evolved since early Christian days. The most common flowers and their symbolic meanings include: rose (Virgin Mary, transience, Venus, love); lily (Virgin Mary, virginity, female breast, purity of mind or justice); tulip (showiness, nobility); sunflower (faithfulness, divine love, devotion); violet (modesty, reserve, humility); columbine (melancholy); poppy (power, sleep, death). As for insects, the butterfly represents transformation and resurrection while the dragonfly symbolizes transience and the ant hard work and attention to the harvest.[33]

Flemish and Dutch artists also branched out and revived the ancient Greek still life tradition of trompe-l’œil, particularly the imitation of nature or mimesis, which they termed bedriegertje («little deception»).[8] In addition to these types of still life, Dutch artists identified and separately developed «kitchen and market» paintings, breakfast and food table still life, vanitas paintings, and allegorical collection paintings.[34]

In the Catholic Southern Netherlands the genre of garland paintings was developed. Around 1607–1608, Antwerp artists Jan Brueghel the Elder and Hendrick van Balen started creating these pictures which consist of an image (usually devotional) which is encircled by a lush still life wreath. The paintings were collaborations between two specialists: a still life and a figure painter. Daniel Seghers developed the genre further. Originally serving a devotional function, garland paintings became extremely popular and were widely used as decoration of homes.[35]

A special genre of still life was the so-called pronkstilleven (Dutch for ‘ostentatious still life’). This style of ornate still-life painting was developed in the 1640s in Antwerp by Flemish artists such as Frans Snyders and Adriaen van Utrecht. They painted still lifes that emphasized abundance by depicting a diversity of objects, fruits, flowers and dead game, often together with living people and animals. The style was soon adopted by artists from the Dutch Republic.[36]

Especially popular in this period were vanitas paintings, in which sumptuous arrangements of fruit and flowers, books, statuettes, vases, coins, jewelry, paintings, musical and scientific instruments, military insignia, fine silver and crystal, were accompanied by symbolic reminders of life’s impermanence. Additionally, a skull, an hourglass or pocket watch, a candle burning down or a book with pages turning, would serve as a moralizing message on the ephemerality of sensory pleasures. Often some of the fruits and flowers themselves would be shown starting to spoil or fade to emphasize the same point.[citation needed]

-

-

-

Jan Jansz. Treck (1606–1652), Still Life Pewter Jug and Two Porcelain Plates (1645)

Another type of still life, known as ontbijtjes or «breakfast paintings», represent both a literal presentation of delicacies that the upper class might enjoy and a religious reminder to avoid gluttony.[37] Around 1650 Samuel van Hoogstraten painted one of the first wall-rack pictures, trompe-l’œil still-life paintings which feature objects tied, tacked or attached in some other fashion to a wall board, a type of still life very popular in the United States in the 19th century.[38] Another variation was the trompe-l’œil still life depicted objects associated with a given profession, as with the Cornelis Norbertus Gysbrecht’s painting «Painter’s Easel with Fruit Piece», which displays all the tools of a painter’s craft.[39] Also popular in the first half of the 17th century was the painting of a large assortment of specimens in allegorical form, such as the «five senses», «four continents», or «the four seasons», showing a goddess or allegorical figure surrounded by appropriate natural and man-made objects.[40] The popularity of vanitas paintings, and these other forms of still life, soon spread from Holland to Flanders and Germany, and also to Spain[41] and France.

The Netherlandish production of still lifes was enormous, and they were very widely exported, especially to northern Europe; Britain hardly produced any itself. German still life followed closely the Dutch models; Georg Flegel was a pioneer in pure still life without figures and created the compositional innovation of placing detailed objects in cabinets, cupboards, and display cases, and producing simultaneous multiple views.[42]

Dutch, Flemish, German and French paintings[edit]

-

Peter Paul Rubens, Diana Returning from the Hunt, still life elements by a specialist (c. 1615)

-

Rembrandt, Still-Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl (c. 1639)

-

Pieter Boel (1626–1674), Still Life with a Globe and a Parrot (c. 1658)

-

-

Osias Beert the Elder, Dishes with Oysters, Fruit, and Wine

-

George Flegel (1566–1638), Still-Life with Bread and Confectionery, 1630

Southern Europe[edit]

In Spanish art, a bodegón is a still-life painting depicting pantry items, such as victuals, game, and drink, often arranged on a simple stone slab, and also a painting with one or more figures, but significant still-life elements, typically set in a kitchen or tavern. Starting in the Baroque period, such paintings became popular in Spain in the second quarter of the 17th century. The tradition of still-life painting appears to have started and was far more popular in the contemporary Low Countries, today Belgium and Netherlands (then Flemish and Dutch artists), than it ever was in southern Europe. Northern still lifes had many subgenres; the breakfast piece was augmented by the trompe-l’œil, the flower bouquet, and the vanitas.[citation needed]

In Spain there were much fewer patrons for this sort of thing, but a type of breakfast piece did become popular, featuring a few objects of food and tableware laid on a table. Still-life painting in Spain, also called bodegones, was austere. It differed from Dutch still life, which often contained rich banquets surrounded by ornate and luxurious items of fabric or glass. The game in Spanish paintings is often plain dead animals still waiting to be skinned. The fruits and vegetables are uncooked. The backgrounds are bleak or plain wood geometric blocks, often creating a surrealist air. Even while both Dutch and Spanish still life often had an embedded moral purpose, the austerity, which some find akin to the bleakness of some of the Spanish plateaus, appears to reject the sensual pleasures, plenitude, and luxury of Dutch still-life paintings.[44]

Even though Italian still-life painting (in Italian referred to as natura morta, «dead nature») was gaining in popularity, it remained historically less respected than the «grand manner» painting of historical, religious, and mythic subjects. On the other hand, successful Italian still-life artists found ample patronage in their day.[45] Furthermore, women painters, few as they were, commonly chose or were restricted to painting still life; Giovanna Garzoni, Laura Bernasconi, Maria Theresa van Thielen, and Fede Galizia are notable examples.[citation needed]

Many leading Italian artists in other genre, also produced some still-life paintings. In particular, Caravaggio applied his influential form of naturalism to still life. His Basket of Fruit (c. 1595–1600) is one of the first examples of pure still life, precisely rendered and set at eye level.[46] Though not overtly symbolic, this painting was owned by Cardinal Federico Borromeo and may have been appreciated for both religious and aesthetic reasons. Jan Bruegel painted his Large Milan Bouquet (1606) for the cardinal, as well, claiming that he painted it ‘fatta tutti del natturel’ (made all from nature) and he charged extra for the extra effort.[47] These were among many still-life paintings in the cardinal’s collection, in addition to his large collection of curios. Among other Italian still life, Bernardo Strozzi’s The Cook is a «kitchen scene» in the Dutch manner, which is both a detailed portrait of a cook and the game birds she is preparing.[48] In a similar manner, one of Rembrandt’s rare still-life paintings, Little Girl with Dead Peacocks combines a similar sympathetic female portrait with images of game birds.[49]

In Catholic Italy and Spain, the pure vanitas painting was rare, and there were far fewer still-life specialists. In Southern Europe there is more employment of the soft naturalism of Caravaggio and less emphasis on hyper-realism in comparison with Northern European styles.[50] In France, painters of still lifes (nature morte) were influenced by both the Northern and Southern schools, borrowing from the vanitas paintings of the Netherlands and the spare arrangements of Spain.[51]

Italian gallery[edit]

Eighteenth century[edit]

Luis Meléndez (1716–1780), Still Life with Apples, Grapes, Melons, Bread, Jug and Bottle

The 18th century to a large extent continued to refine 17th-century formulae, and levels of production decreased. In the Rococo style floral decoration became far more common on porcelain, wallpaper, fabrics and carved wood furnishings, so that buyers preferred their paintings to have figures for a contrast. One change was a new enthusiasm among French painters, who now form a large proportion of the most notable artists, while the English remained content to import. Jean-Baptiste Chardin painted small and simple assemblies of food and objects in a most subtle style that both built on the Dutch Golden Age masters, and was to be very influential on 19th-century compositions. Dead game subjects continued to be popular, especially for hunting lodges; most specialists also painted live animal subjects. Jean-Baptiste Oudry combined superb renderings of the textures of fur and feather with simple backgrounds, often the plain white of a lime-washed larder wall, that showed them off to advantage.[citation needed]

By the 18th century, in many cases, the religious and allegorical connotations of still-life paintings were dropped and kitchen table paintings evolved into calculated depictions of varied colour and form, displaying everyday foods. The French aristocracy employed artists to execute paintings of bounteous and extravagant still-life subjects that graced their dining table, also without the moralistic vanitas message of their Dutch predecessors. The Rococo love of artifice led to a rise in appreciation in France for trompe-l’œil (French: «trick the eye») painting. Jean-Baptiste Chardin’s still-life paintings employ a variety of techniques from Dutch-style realism to softer harmonies.[52]

The bulk of Anne Vallayer-Coster’s work was devoted to the language of still life as it had been developed in the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[53] During these centuries, the genre of still life was placed lowest on the hierarchical ladder. Vallayer-Coster had a way about her paintings that resulted in their attractiveness. It was the «bold, decorative lines of her compositions, the richness of her colours and simulated textures, and the feats of illusionism she achieved in depicting wide variety of objects, both natural and artificial»[53] which drew in the attention of the Royal Académie and the numerous collectors who purchased her paintings. This interaction between art and nature was quite common in Dutch, Flemish and French still lifes.[53] Her work reveals the clear influence of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, as well as 17th-century Dutch masters, whose work has been far more highly valued, but what made Vallayer-Coster’s style stand out against the other still-life painters was her unique way of coalescing representational illusionism with decorative compositional structures.[53][54]

The end of the eighteenth century and the fall of the French monarchy closed the doors on Vallayer-Coster’s still-life ‘era’ and opened them to her new style of florals.[55] It has been argued that this was the highlight of her career and what she is best known for. However, it has also been argued that the flower paintings were futile to her career. Nevertheless, this collection contained floral studies in oil, watercolour and gouache.[55]

-

Carl Hofverberg (1695–1765), Trompe-l’œil (1737), Foundation of the Royal Armoury, Sweden

-

Rachel Ruysch, Roses, Convolvulus, Poppies, and Other Flowers in an Urn on a Stone Ledge (1680s)

Nineteenth century[edit]

With the rise of the European Academies, most notably the Académie française which held a central role in Academic art, still life began to fall from favor. The Academies taught the doctrine of the «Hierarchy of genres» (or «Hierarchy of Subject Matter»), which held that a painting’s artistic merit was based primarily on its subject. In the Academic system, the highest form of painting consisted of images of historical, Biblical or mythological significance, with still-life subjects relegated to the very lowest order of artistic recognition. Instead of using still life to glorify nature, some artists, such as John Constable and Camille Corot, chose landscapes to serve that end.[citation needed]

When Neoclassicism started to go into decline by the 1830s, genre and portrait painting became the focus for the Realist and Romantic artistic revolutions. Many of the great artists of that period included still life in their body of work. The still-life paintings of Francisco Goya, Gustave Courbet, and Eugène Delacroix convey a strong emotional current, and are less concerned with exactitude and more interested in mood.[56] Though patterned on the earlier still-life subjects of Chardin, Édouard Manet’s still-life paintings are strongly tonal and clearly headed toward Impressionism. Henri Fantin-Latour, using a more traditional technique, was famous for his exquisite flower paintings and made his living almost exclusively painting still life for collectors.[57]

However, it was not until the final decline of the Academic hierarchy in Europe, and the rise of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters, that technique and colour harmony triumphed over subject matter, and that still life was once again avidly practiced by artists. In his early still life, Claude Monet shows the influence of Fantin-Latour, but is one of the first to break the tradition of the dark background, which Pierre-Auguste Renoir also discards in Still Life with Bouquet and Fan (1871), with its bright orange background. With Impressionist still life, allegorical and mythological content is completely absent, as is meticulously detailed brush work. Impressionists instead focused on experimentation in broad, dabbing brush strokes, tonal values, and colour placement. The Impressionists and Post-Impressionists were inspired by nature’s colour schemes but reinterpreted nature with their own colour harmonies, which sometimes proved startlingly unnaturalistic. As Gauguin stated, «Colours have their own meanings.»[58] Variations in perspective are also tried, such as using tight cropping and high angles, as with Fruit Displayed on a Stand by Gustave Caillebotte, a painting which was mocked at the time as a «display of fruit in a bird’s-eye view.»[59]

Vincent van Gogh’s «Sunflowers» paintings are some of the best-known 19th-century still-life paintings. Van Gogh uses mostly tones of yellow and rather flat rendering to make a memorable contribution to still-life history. His Still Life with Drawing Board (1889) is a self-portrait in still-life form, with Van Gogh depicting many items of his personal life, including his pipe, simple food (onions), an inspirational book, and a letter from his brother, all laid out on his table, without his own image present. He also painted his own version of a vanitas painting Still Life with Open Bible, Candle, and Book (1885).[58]

In the United States during Revolutionary times, American artists trained abroad applied European styles to American portrait painting and still life. Charles Willson Peale founded a family of prominent American painters, and as major leader in the American art community, also founded a society for the training of artists as well as a famous museum of natural curiosities. His son Raphaelle Peale was one of a group of early American still-life artists, which also included John F. Francis, Charles Bird King, and John Johnston.[60] By the second half of the 19th century, Martin Johnson Heade introduced the American version of the habitat or biotope picture, which placed flowers and birds in simulated outdoor environments.[61] The American trompe-l’œil paintings also flourished during this period, created by John Haberle, William Michael Harnett, and John Frederick Peto. Peto specialized in the nostalgic wall-rack painting while Harnett achieved the highest level of hyper-realism in his pictorial celebrations of American life through familiar objects.[62]

Nineteenth-century paintings[edit]

-

Henri Fantin-Latour, (1836–1904), White Roses, Chrysanthemums in a Vase, Peaches and Grapes on a Table with a White Tablecloth (1867)

-

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), The Black Marble Clock (1869–1871), private collection

-

Twentieth century[edit]

The first four decades of the 20th century formed an exceptional period of artistic ferment and revolution. Avant-garde movements rapidly evolved and overlapped in a march towards nonfigurative, total abstraction. The still life, as well as other representational art, continued to evolve and adjust until mid-century when total abstraction, as exemplified by Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, eliminated all recognizable content.[citation needed]

The century began with several trends taking hold in art. In 1901, Paul Gauguin painted Still Life with Sunflowers, his homage to his friend Van Gogh who had died eleven years earlier. The group known as Les Nabis, including Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, took up Gauguin’s harmonic theories and added elements inspired by Japanese woodcuts to their still-life paintings. French artist Odilon Redon also painted notable still life during this period, especially flowers.[63]

Henri Matisse reduced the rendering of still-life objects even further to little more than bold, flat outlines filled with bright colours. He also simplified perspective and introducing multi-colour backgrounds.[64] In some of his still-life paintings, such as Still Life with Eggplants, his table of objects is nearly lost amidst the other colourful patterns filling the rest of the room.[65] Other exponents of Fauvism, such as Maurice de Vlaminck and André Derain, further explored pure colour and abstraction in their still life.[citation needed]

Paul Cézanne found in still life the perfect vehicle for his revolutionary explorations in geometric spatial organization. For Cézanne, still life was a primary means of taking painting away from an illustrative or mimetic function to one demonstrating independently the elements of colour, form, and line, a major step towards Abstract art. Additionally, Cézanne’s experiments can be seen as leading directly to the development of Cubist still life in the early 20th century.[66]

Adapting Cézanne’s shifting of planes and axes, the Cubists subdued the colour palette of the Fauves and focused instead on deconstructing objects into pure geometrical forms and planes. Between 1910 and 1920, Cubist artists like Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Juan Gris painted many still-life compositions, often including musical instruments, bringing still life to the forefront of artistic innovation, almost for the first time. Still life was also the subject matter in the first Synthetic Cubist collage works, such as Picasso’s oval «Still Life with Chair Caning» (1912). In these works, still-life objects overlap and intermingle barely maintaining identifiable two-dimensional forms, losing individual surface texture, and merging into the background—achieving goals nearly opposite to those of traditional still life.[67] Fernand Léger’s still life introduced the use of abundant white space and coloured, sharply defined, overlapping geometrical shapes to produce a more mechanical effect.[68]

Rejecting the flattening of space by Cubists, Marcel Duchamp and other members of the Dada movement, went in a radically different direction, creating 3-D «ready-made» still-life sculptures. As part of restoring some symbolic meaning to still life, the Futurists and the Surrealists placed recognizable still-life objects in their dreamscapes. In Joan Miró’s still-life paintings, objects appear weightless and float in lightly suggested two-dimensional space, and even mountains are drawn as simple lines.[66] In Italy during this time, Giorgio Morandi was the foremost still-life painter, exploring a wide variety of approaches to depicting everyday bottles and kitchen implements.[69] Dutch artist M. C. Escher, best known for his detailed yet ambiguous graphics, created Still life and Street (1937), his updated version of the traditional Dutch table still life.[70] In England Eliot Hodgkin was using tempera for his highly detailed still-life paintings.[citation needed]

When 20th-century American artists became aware of European Modernism, they began to interpret still-life subjects with a combination of American realism and Cubist-derived abstraction. Typical of the American still-life works of this period are the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe, Stuart Davis, and Marsden Hartley, and the photographs of Edward Weston. O’Keeffe’s ultra-closeup flower paintings reveal both the physical structure and the emotional subtext of petals and leaves in an unprecedented manner.[citation needed]

In Mexico, starting in the 1930s, Frida Kahlo and other artists created their own brand of Surrealism, featuring native foods and cultural motifs in their still-life paintings.[71]

Starting in the 1930s, abstract expressionism severely reduced still life to raw depictions of form and colour, until by the 1950s, total abstraction dominated the art world. However, pop art in the 1960s and 1970s reversed the trend and created a new form of still life. Much pop art (such as Andy Warhol’s «Campbell’s Soup Cans») is based on still life, but its true subject is most often the commodified image of the commercial product represented rather than the physical still-life object itself. Roy Lichtenstein’s Still Life with Goldfish Bowl (1972) combines the pure colours of Matisse with the pop iconography of Warhol. Wayne Thiebaud’s Lunch Table (1964) portrays not a single family’s lunch but an assembly line of standardized American foods.[72]

The Neo-dada movement, including Jasper Johns, returned to Duchamp’s three-dimensional representation of everyday household objects to create their own brand of still-life work, as in Johns’ Painted Bronze (1960) and Fool’s House (1962).[73] Avigdor Arikha, who began as an abstractionist, integrated the lessons of Piet Mondrian into his still lifes as into his other work; while reconnecting to old master traditions, he achieved a modernist formalism, working in one session and in natural light, through which the subject-matter often emerged in a surprising perspective.[citation needed]

A significant contribution to the development of still-life painting in the 20th century was made by Russian artists, among them Sergei Ocipov, Victor Teterin, Evgenia Antipova, Gevork Kotiantz, Sergei Zakharov, Taisia Afonina, Maya Kopitseva, and others.[74]

By contrast, the rise of Photorealism in the 1970s reasserted illusionistic representation, while retaining some of Pop’s message of the fusion of object, image, and commercial product. Typical in this regard are the paintings of Don Eddy and Ralph Goings.[citation needed]

Twentieth-century paintings[edit]

21st century[edit]

During the 20th and 21st centuries, the notion of the still life has been extended beyond the traditional two dimensional art forms of painting into video art and three dimensional art forms such as sculpture, performance and installation. Some mixed media still-life works employ found objects, photography, video, and sound, and even spill out from ceiling to floor and fill an entire room in a gallery. Through video, still-life artists have incorporated the viewer into their work. Following from the computer age with computer art and digital art, the notion of the still life has also included digital technology. Computer-generated graphics have potentially increased the techniques available to still-life artists. 3D computer graphics and 2D computer graphics with 3D photorealistic effects are used to generate synthetic still life images. For example, graphic art software includes filters that can be applied to 2D vector graphics or 2D raster graphics on transparent layers. Visual artists have copied or visualised 3D effects to manually render photorealistic effects without the use of filters.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

- Dutch Golden Age painting

- List of Dutch painters

- Vanitas

- Memento Mori

- Still life photography

Notes[edit]

- ^ Langmuir, 6

- ^ Langmuir, 13–14

- ^ Langmuir, 13–14 and preceding pages

- ^ Book XXXV.112 of Natural History

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 19

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p.22

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p.137

- ^ a b Ebert-Schifferer, p. 16

- ^ a b Ebert-Schifferer, p. 15

- ^ Memlings Portraits exhibition review, Frick Collection, NYC. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p.25

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 27

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 26

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 39, 53

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 41

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 31

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 34

- ^ Slive, 275; Vlieghe, 211–216

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 45

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 47

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p.38

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, pp. 54–56

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 64

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 75

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art Timeline, Still-life painting 1600–1800. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ^ Books.google.co.uk, translation

- ^ Slive 277–279

- ^ Vlieghe, 207

- ^ Slive, 279, Vlieghe, 206-7

- ^ Paul Taylor, Dutch Flower Painting 1600–1720, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1995, p. 77, ISBN 0-300-05390-8

- ^ Taylor, p. 129

- ^ Taylor, p. 197

- ^ Taylor, pp. 56–76

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 93

- ^ Susan Merriam, Seventeenth-century Flemish Garland Paintings: Still Life, Vision, and the Devotional Image, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2012

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms: Pronkstilleven

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 90

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 164

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 170

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, pp. 180–181

- ^ See Juan van der Hamen.

- ^ Zuffi, p. 260

- ^ Lucie-Smith, Edward (1984). The Thames and Hudson Dictionary of Art Terms. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 32. ISBN 9780500233894. LCCN 83-51331

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 71

- ^ La natura morta in Italia edited by Francesco Porzio and directed by Federico Zeri; Review author: John T. Spike. The Burlington Magazine (1991) Volume 133 (1055) page 124–125.

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 82

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 84

- ^ Stefano Zuffi, Ed., Baroque Painting, Barron’s Educational Series, Hauppauge, New York, 1999, p. 96, ISBN 0-7641-5214-9

- ^ Zuffi, p. 175

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 173

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 229

- ^ Zuffi, p. 288, 298

- ^ a b c d Michel 1960, p. i

- ^ Berman 2003

- ^ a b Michel 1960, p. ii

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 287

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 299

- ^ a b Ebert-Schifferer, p. 318

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 310

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 260

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 267

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 272

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 321

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, pp. 323–4

- ^ Stefano Zuffi, Ed., Modern Painting, Barron’s Educational Series, Hauppauge, New York, 1998, p. 273, ISBN 0-7641-5119-3

- ^ a b Ebert-Schifferer, p. 311

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 338

- ^ David Piper, The Illustrated Library of Art, Portland House, New York, 1986, p. 643, ISBN 0-517-62336-6

- ^ David Piper, p. 635

- ^ Piper, p. 639

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 387

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, pp. 382–3

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. 384-6

- ^ Sergei V. Ivanov, Unknown Socialist Realism. The Leningrad School. – Saint Petersburg: NP-Print Edition, 2007. – 448 p. ISBN 5-901724-21-6, ISBN 978-5-901724-21-7.

References[edit]

- Berman, Greta. “Focus on Art”. The Juilliard Journal Online 18:6 (March 2003)

- Ebert-Schifferer, Sybille. Still Life: A History, Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1998, ISBN 0-8109-4190-2

- Langmuir, Erica, Still Life, 2001, National Gallery (London), ISBN 1857099613

- Michel, Marianne Roland. «Tapestries on Designs by Anne Vallayer-Coster.» The Burlington Magazine 102: 692 (November 1960): i–ii

- Slive, Seymour, Dutch Painting, 1600–1800, Yale University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-300-07451-4

- Vlieghe, Hans (1998). Flemish Art and Architecture, 1585–1700. Yale University Press Pelican history of art. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07038-1

External links[edit]

Media related to Still-life paintings at Wikimedia Commons

- Cover

- Gallery

- ArtClub

- Shop

- Art News

- Forum

Still life 1 907 words Automatic translate

Automatic translate

The word «still life» is of French origin and literally means «dead nature.» In painting, this word denotes the image of various inanimate objects.

References

Seven and a half thousand still lifes in the Art Club

Tone Still Life

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, a still life was only part of the composition on canvas. For example, garlands of flowers around the figures of Christ and the Mother of God, painting the reverse sides of altar images, or simply skulls in the hands of people depicted in portraits.

In the seventeenth century, still life became an independent genre of painting, which was greatly facilitated by the work of masters of the Flemish and Dutch schools. The objects depicted in paintings of that time often hide in themselves a kind of philosophical allegory — the inevitability of death and the transience of everything earthly, or broader meanings of religious subjects. But the flower still life is gaining great popularity — this is directly related to the traditions of Holland: its own gardens, country villas, just houseplants, a love of floriculture is inherent in this country. An example of a Dutch flower still life is luxurious compositions, authored by the painter Jan Davids de Hem.

When writing a still life, you need to choose a worthy object for the image.

Fresh vegetables

fit perfectly. Their bright colors will cheer you up when you admire the picture.

Still life is almost always a group of things connected by a common meaning. This group may include objects from wildlife, but isolated from their natural environment, turned into a thing: a fish on a table, a vase with flowers or fruits, and so on. Sometimes the composition of a still life includes an image of living elements: birds, animals, insects, people, but they only complement the main idea of the picture. A still life selects objects from the general context of everyday life, draws increased attention to the smallest details and structure of surfaces, makes you wonder at the beauty of ordinary things and natural forms, which most often a person does not bother to consider, glancing over them with a superficial gaze.

Decorative still life — the main laws of graphic solutions

Under the decorative still life is often understood a very arbitrary treatment of nature, leading to its unjustified distortion, because ignorance of the laws of work on this genre entails a lot of mistakes.

Decorative painting, like academic painting, is based on strict laws and principles. And the ability to translate the depicted nature from the visible three-dimensional into two-dimensional space and at the same time successfully solve creative, compositional and pictorial problems is necessary for all high-level artists, because their work is designed to decorate many interiors.

We all know that the «decorative» from the word «decor» — to decorate, decoration. The word has two meanings:

- a method aimed at creating an expressive silhouette that has increased artistry compared to objects in the surrounding world;

- specificity of planar works of art.

If we look at the history of fine art, we notice that all types of visual activity that can be attributed to painting, from ancient times to the Renaissance, are decorative. From cave cave paintings, ancient Egyptian, ancient Greek, all the art of the peoples of the East and Asia to Giotto’s frescoes, the artist did not “destroy” the graphic surface, creating the illusion of space, but organically connected the surface of the image, regardless of whether it was flat or voluminous, with image.

In the last century, the famous researcher of folk and decorative arts, who lived and worked in Gzhel at one time, A. B. Saltykov said that flat, surface and silhouette painting, of course, is most able to emphasize and express form.

Starting from the Renaissance, painters began to set themselves some other tasks relating to the transfer of depth, space and air in the works they create.

A return to decorativeness in painting occurred in the Art Nouveau era, shortly before the final formation of style in the 19th century. To a large extent, this was due to the discovery of Japanese art, which retained, due to the isolation of its development, a decorative basis. Sensitive and careful observation of nature, accurate and reliable vision, lightness and understatement, at the same time, expressiveness and thoughtfulness of the silhouette solution in engravings by Japanese artists gave rise to unique and unforgettable images. Woodcutters Kutagawa Utamaro and Katsushiko Hokusai are widely known. More than one generation of artists has been brought up on impeccable plastic and proportionate composition of Japanese engraving.

Late 19th — early 20th centuries — A time of interesting creative searches and finds. When working on still life, you should focus on this particular period in the history of painting. The art of the best masters of that time combines amazing silhouette expressiveness, sophistication, compositional laconicism and completeness, combined with the rich experience of artists of the last centuries in creating harmonious, diverse and complex coloristic constructions. Therefore, when working on a decorative still life, it is recommended to pay attention to the work of famous Russian artists of that time — Alexander Golovin, Valentin Serov, Alexander Benois, Lev Bakst, Mikhail Vrubel, Alexander Lansere, Konstantin Somov, Alexander Kuprin, Ilya Mashkov, Pyotr Konchalovsky, Kuzma Petrov- Vodkin, Konstantin Yuon, Igor Grabar, as well as European painters — Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Cezanne, Camille Pissarro, Gustav Klimt and others.

The process of working on still life begins with the choice of a point of view on nature. And if in a realistic image complex angles and lateral light will be the most successful choice, as the most transmitting depth of space and volumetric form, then in a decorative, on the contrary, direct light and the point of view “in front” will be the best options, making it easier to solve the task.

There are several well-known techniques that enhance the impression of decorativeness:

- the introduction of a color or achromatic contour, combining differently removed objects on the same plane;

- saturation with an ornament;

- overlapping of one subject by another overlepping;

- the rear view is visible through the front.

The lines can be either straight or curved, they can create their own simple pattern or reinforce the diagonal or introduce rhythmic horizontal or vertical repetitions, perhaps this will be something completely unusual and new, but the main thing is that any introduction to the work of the grid, module, crushing The image enhances the decorative effect, because it combines plans and turns the entire work into a rhythmically organized pattern, and rhythmic repetitions, in turn, enhance the decorativeness of the painting.

Quality, which is the main condition of the picturesque image, is the expressiveness of the composition, which directly depends on the correctly found contrast, giving it decorative power. But there are structural contrasts that lie deeper and determine the nature of the artistic image. In this regard, we must try to level out the unnecessary associations that arise, which interfere with the whole perception of the plane.

Consider the basic laws by which the work on a decorative still life is built. There is an opinion that decorative painting is very different from academic painting, that these are two things of a different order. We will carefully look at what the difference is and what is common between academic and decorative painting. Both laws are based on the same laws — color harmony, consonant color, compositional expressiveness, rhythmic organization of the elements of a work, imaginative solution. It is also necessary to note the difference — in decorative painting, two-dimensional space, in contrast to the three-dimensional academic, therefore, it is necessary to exclude the linear and air perspective as much as possible, there is also no illusory transmission of volumetric form, but the rhythmic organization plays the most important role, since rhythm helps strengthen decorative the basis of the painting. There is a more arbitrary attitude to natural material and its greater creative interpretation in order to enhance the expressiveness of the composition and presentation of the image.

The graphic side of the work is very important, without a refined, verified, expressive symbolic composition with a simple and clear foundation and complex and diverse development, there cannot be a worthy work.

But the most important characteristic of painting is color. That is why the creation of a delightful color mosaic with its contrasts and nuances of color and tone, with loud color chords and subtle hues is the student’s first task. Without this, the painting is dry and boring. To convey the mood, state, create a memorable image by all means of painting — color, composition, drawing — this is the main task facing students. Nature represents the richest and most diverse material for creativity, you only need the ability to see artistically and shift to a pictorial language that is suitable for each individual case. The upbringing of an indifferent, not superficial, but an attentive, sensitive and subtle look at nature, the development of skills for translating a natural image into a decor language is the goal of this task.

Much can be said about the emotional impact of color, about enhancing its decorativeness, about the varying degrees of conditionality of a decorative still life — from those closest to nature in terms of developing color and allowing a small volume, like a low relief in a sculptural image, to a poster and a sign as an extreme degree of decorativeness. But we must summarize and say that in general, work on a decorative still life is not a change of nature according to an arbitrary principle, it is based, like the work on an academic work of painting, on certain laws, the knowledge of which, of course, is necessary when performing it.

Still life

Fulfillment of still lifes with the image of bouquets of flowers and herbs, the application of modern art technologies and techniques in their implementation and their inclusion in the interior as a color accent and dominant, harmoniously combined with the imaginative solution and the image of the artistic interior solution is an important task in the search for new creative solutions in the interior design of contemporary artists.

The history of the appearance and distribution of images of bouquets of flowers and herbs in the art of painting and the artistic solution of the interior is interesting and multifaceted. A picturesque bouquet has always served as an active color spot in the interior. When you include it in the interior, it is very important to maintain the stylistic unity of the entire interior, to withstand its characteristic features, and not to violate the figurative structure and artistic decision of the entire interior. Therefore, it is no coincidence that many artists of different times constantly returned to the image of flowers in their works.

Bouquets of flowers, in various designs, in various types of art, along with other common motifs, are one of the main motives in interior design. The symbolic meaning of flowers in art has rich traditions. Field herbs symbolize hopelessness, a flower garland resembles a symbol of eternity. Many flowers and plants are symbols of the seasons: lemons are winter, flowers are spring, fruits are summer, grapes are autumn.

The main role in the implementation of still lifes is played by the study of the sequence and technology for the implementation of still lifes in colors, the study of masterpieces of world art in this area, familiarity with new art technologies and materials that can be applied in the work on a still life with a bouquet.

Fulfillment of still lifes with bouquets of flowers and herbs usually causes great difficulties, since working on the image of the shape of an individual flower and a bouquet as a whole, as well as identifying the relationship between a bouquet and a still life, is a difficult task and requires a special approach to the methodology and technology for performing still life.

When creating a still life, it is important to observe the methodological sequence. At the first stage, it is necessary to determine the general color and tone content of the production, the main color relationships, it is necessary to correctly find the composition of the work, the correct proportional ratio of objects, determine the place for all objects and determine the size of the bouquet. The center of the composition can be distinguished using a contrast solution of flowers and shapes.

In almost all still lifes with flowers, the bouquet is the center of the composition, serves as a color and compositional accent, and performing it in color is the most difficult task in working on such a still life. After the sketch is completed, it is necessary to correctly and most accurately transfer it to a large format and how to accurately determine the place of the bouquet in the still life composition. Then you can proceed to the second stage of work — the implementation of a still life with a bouquet in color. You can’t start work with a detailed study of the bouquet, you don’t need to write out each flower and leaf separately, you need to understand what place the bouquet occupies in a still life, how it combines with the background and the objects surrounding it, it is necessary to identify the nature of the bouquet and the main features of its flowers and leaves.

When performing a still life with bouquets of flowers and herbs, you can enrich and complicate the image, achieving additional effects through the use of new paints (volumetric, fluorescent, textured), various effects from other types of art (for example, from hand-painted fabric — salt), it is possible, the use of some professional techniques of the artist-designer in the image and transfer of various textures, the application of the techniques and capabilities of the collage, etc.

Creating a still life with a plaster head

Of great importance in the development of skills in academic painting is the constant work on productions with plaster casts, ranging from simple, consisting of only a small number of still life objects, to complex thematic productions, including a figure and an interior, as well as multi-level complex compositional still lifes. The importance of performing productions with a gypsum head is due to the fact that the drawing and image in the color of gypsum casts facilitate the further study of the laws of still life. The gypsum form is colorless, unlike the living model, therefore it makes it possible to more clearly understand the form and convey the color of white through the influence of the environment and the nature of the lighting on it. Work on a still life with a plaster head helps to focus on the form, makes it possible to more fully study this form, the nature and proportions of the plaster model, since there is no movement in it and only the most characteristic details are revealed.

In different historical eras and in all national schools of painting, there was an interest in depicting antique plaster casts and fragments of sculpture from Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. The main subject of the image in such still lifes was a plaster head, a plaster cast, which subjugated all the objects surrounding it and draperies.

Still life with gypsum is a very special topic in the art of still life, in which the natural sciences, religious and moral views of man are encrypted. In the history of fine art, there are many examples of still-life with a plaster head, which are an example of high skill. Outstanding Russian artists Levitsky, K. Bryullov, A. Ivanov, who were not inferior in terms of drawing and painting techniques to the greatest masters of the West, paid great attention to work on a still life with gypsum. The most famous work of Western masters is «Still Life with the Attributes of Art» by J.-B. Chardin, written in the 1760s.

The main condition for the successful implementation of a still life with a plaster head is a consistent and systematic course of work. When staging a still life, it is necessary to determine the coloristic and thematic content of the work. Performing a still life with a plaster head in various colors helps to solve the problem of forming the skills of the most accurate reproduction of color relationships.

An essential role in the performance of a still life will be played by the compositional concept. It is necessary to think over the layout of all the objects that make up the still life, find their silhouette, determine the amount of light and dark, color accents, especially the transfer of white gypsum color.

Before doing work, you need to make several color sketches or studies. The purpose of this work is to study the laws of painting, search for color and compositional solutions to the work. The study is carried out by students in order to identify and convey the most characteristic linear-plastic features of nature, the basic color and tone relationships of the still life.

When working on plaster in color, artists should pay great attention to subtle tonal transitions. The meaning of tone in painting is of great importance. The wrong tone of a color in a work on a painting negatively affects the quality of the work. When working on a still life with a plaster head, as well as when working on any painting, you must remember that nearby objects have a different tone, and correctly determine this tone difference.

Text: Smirnov Vyacheslav Fedorovich

- «Portrait of Winter» — eine Ausstellung, die in Kostroma eröffnet wurde. kombinierte die Arbeit des Malers und Bildhauers

- An exhibition-competition «Autumn Salon» has been opened in Sergiv Posad Museum-Reserve

- Zigeunerklänge. 6+

- «Guerreros de luz, amabilidad y libertad»

Словосочетания

Автоматический перевод

натюрморт

Перевод по словам

still — еще, все еще, все-таки, неподвижный, тишина, кадр, успокаиваться

life — жизнь, срок службы, образ жизни, пожизненный, длящийся всю жизнь

Примеры

Democracy still lives!

Демократия всё ещё жива!

My brother still lives with our parents.

Мой брат до сих пор живёт с родителями.

He still lives not far from where he was born.

Он по-прежнему живёт недалеко от места рождения.

The ghost of Stalinism still affects life in Russia today.

В наши дни призрак сталинизма всё ещё влияет на жизнь в России.

A third of the region’s population still lives off the land.

Треть населения данного региона по прежнему живёт за счёт земли.

Édouard Manet once called still life “the touchstone of painting.” Characterized by an interest in the insentient, this genre of art has been popular across movements, cultures, and periods, with major figures like Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso sharing the Impressionist artist‘s view.

Here, we explore the age-old genre, tracing its history and looking at well-known works to answer the questions: what is still life painting, and how has it evolved over time?

What is a Still Life?

A still life (also known by its French title, nature morte) painting is a piece that features an arrangement of inanimate objects as its subject. Usually, these items are set on a table and often include organic objects like fruit and flowers and household items like glassware and textiles.

The term “still life” is derived from the Dutch word stilleven, which gained prominence during the 16th century. While it was during this time that the still life gained recognition as a genre, its roots date back to ancient times.

Types of Still Lifes

Most still lifes can be placed into one of four categories: flowers, banquet or breakfast, animal(s), and symbolic. While most of these types are self-explanatory—flower pieces tend to focus on bouquets or vases of full blooms and a banquet work features an array of food items—symbolic still lifes can vary greatly.

In most cases, symbolic paintings use different objects to convey deeper meanings or narratives. This is best exemplified perhaps in vanitas painting: a genre of still life that focuses on the fleetingness of life.

History of Still Life Painting

Ancient Art

The earliest known still life paintings were created by the Egyptians in the 15th century BCE. Funerary paintings of food—including crops, fish, and meat—have been discovered in ancient burial sites. The most famous ancient Egyptian still-life was discovered in the Tomb of Menna, a site whose walls were adorned with exceptionally detailed scenes of everyday life.

Ancient Greeks and Romans also created similar depictions of inanimate objects. While they mostly reserved still-life subject matter for mosaics, they also employed it for frescoes, like Still Life with Glass Bowl of Fruit and Vases, a 1st-century wall painting from Pompeii.

Middle Ages

“Hours of Catherine of Cleves,” 1440

During the Middle Ages, artists adapted the still life for religious purposes. In addition to incorporating symbolic arrangements into depictions of Biblical scenes, they also used them to decorate illuminated manuscripts. Objects like coins, seashells, and bushels of fruit can be found in the borders of these books, including the elaborately decorated Hours of Catherine of Cleves from the 15th century.

Renaissance

Northern Renaissance artists popularized still life iconography with their flower paintings. These pieces typically showcase colorful flora “from different countries and even different continents in one vase and at one moment of blooming” (Metropolitan Museum of Art) and often do not feature other subject matter. These paintings rose to prominence in the early 17th century, when Northern Renaissance artists grew increasingly interested in creating realistic studies of everyday items.

Dutch Golden Age artists took this interest in detailed floral art a step further with their vanitas paintings. Vanitas paintings are inspired by memento mori, a genre of painting whose Latin name translates to “remember that you have to die.” Like memento mori depictions, these pieces often pair cut flowers with objects like human skulls, waning candles, and overturned hourglasses to comment on the fleeting nature of life.

Unlike memento mori art, however, vanitas paintings “also include other symbols such as musical instruments, wine, and books to remind us explicitly of the vanity of worldly pleasures and goods” (Tate).

Modern Art

The still life remained a popular feature in many modern art movements. While Impressionist artists like Pierre-Auguste Renoir dabbled in the genre, it made its major modern debut during the Post-Impressionist period, when Vincent van Gogh adopted flower vases as his subject and Cézanne painted a famous series of still lifes featuring apples, wine bottles, and water jugs resting on topsy-turvy tabletops.

Paul Cézanne, The Basket of Apples’ (ca. 1895) (Photo via Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Some of Cézanne’s depictions even pay homage to the vanitas genre by incorporating skulls.

In addition to the Post-Impressionists, Cubist masters Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque and Pop Art pioneer Roy Lichtenstein also favored everyday objects, from bowls of fruit to technological inventions.

Contemporary Art

Tjalf Sparnaay, “Healthy Sandwich,” 2013

Today, many artists put a contemporary twist on the timeless tradition by painting still lifes of modern-day food and objects in a hyperrealistic style. Much like the pieces that inspire them, these high-definition paintings prove that even the most mundane objects can be made into masterpieces.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

Celebrity Fad Diets Recreated as Classical Still Lifes

Sophisticated Flower and Food Arrangements Resemble the Fine Art Beauty of Still-Life Paintings

Colorful Still-Life Embroideries of Quaint Houseplants and Modern Interior Design

Artist Gives Old Paintbrushes New Life and Personality as Baroque Characters

Asked by: Myrtle Corkery

Score: 4.1/5

(51 votes)

A still life is a work of art depicting mostly inanimate subject matter, typically commonplace objects which are either natural or man-made.

What is considered still life?

The classical definition of a still life—a work of art depicting inanimate, typically commonplace objects that are either natural (food, flowers or game) or man-made (glasses, books, vases and other collectibles)—conveys little about the rich associations inherent to this genre.

What is a still life easy definition?

1 : a picture consisting predominantly of inanimate objects. 2 : the category of graphic arts concerned with inanimate subject matter.

Why is it called still life?

Inanimate objects such as fruit, flowers, food and everyday items are painted as the main focus of interest in still lifes. The term derives from the Dutch ‘stilleven’, which became current from about 1650 as a collective name for this type of subject matter.

What is the meaning of still life painting?

Still-life painting, depiction of inanimate objects for the sake of their qualities of form, colour, texture, and composition.

28 related questions found

What is still life used for?

The goal of a still life composition is to direct the viewer’s eye through a painting and lead them toward what the artist thinks is important.

What are the 3 important parts to drawing a still life?

Let’s have a look at some basic drawing techniques for drawing still life.

- Measure your subject.

- Start Drawing the shapes.

- Delineate Shadow Edges.

- Model the Form.

- Add Details and Finish.

Does a still life have to be realistic?

A still life can be realistic or abstract, depending on the particular time and culture in which it was created, and on the particular style of the artist. The still life is a popular genre because the artist has total control over the subject of the painting, the lighting, and the context.

Is there life in art?

Art is life, no matter how fragile the times. Art is a testimony of the human condition. It encompasses all of our hardships, emotions, questions, decisions, perceptions.

What makes a great still life?

One way to make your still life is visually appealing and balanced is to follow the rule of thirds. The rule of thirds is quite common in photography and helps to add balance and tension to a piece of art. … Avoiding unintentional repetition will also help to create a strong still life.

What is another name for still life?

In this page you can discover 9 synonyms, antonyms, idiomatic expressions, and related words for still-life, like: nature-morte, study in still life, inanimate object picture, painting, semi-abstract, portraiture, , self-portrait and figurative.

What is still life short answer?

A still life (plural: still lifes) is a work of art depicting mostly inanimate subject matter, typically commonplace objects which are either natural (food, flowers, dead animals, plants, rocks, shells, etc.) or man-made (drinking glasses, books, vases, jewelry, coins, pipes, etc.).

How many types of still life are there?

In simple terms, still lifes may be classified into four principal groups, including: (1) flower pieces; (2) breakfast or banquet pieces; (3) animal pieces. Many of these works are executed purely to demonstrate the technical virtuosity and drawing ability of the artist.

What is the difference between landscape and still life?

For example, a portrait might also include details of a still life. A landscape is an outdoor scene. … A still life shows objects, such as flowers, food, or musical instruments.

How does art give meaning to life?

Art gives meaning to our lives and helps us understand our world. It is an essential part of our culture because it allows us to have a deeper understanding of our emotions; it increases our self-awareness, and also allows us to be open to new ideas and experiences.

Who said life imitates art?

Life imitates art far more than art imitates life—Oscar Wilde, “The Decay of Lying”

How can I live an art life?

20 Ways to Make Your Life a Work of Art

- Find an empathetic companion in your self.

- Let go of what’s unnecessary.

- Stand still under a dark night sky.

- Find what you enjoy and DO it.

- Be true to what is essential in yourself.

- Be generous and tolerant.

- Believe in your path.

- Allow vulnerability.

Why do we practice to draw and paint a still life?

Explanation: The goal of a still life composition is to direct the viewer’s eye through a painting and lead them toward what the artist thinks is important. … Many beginning painters tend to devote their energy to drawing and painting objects accurately, and find it difficult to create a strong composition.

Why still life drawing is important?

Why make still life drawings? Still lifes will make you overall better at drawing. They are a great way to practice creating shapes and building three-dimensional forms through shading techniques of realistic lighting. You have to use many different skills when you’re working on this sort of drawing.

Who is the most famous still life artist?

Paul Cezanne is considered the greatest master of still life painting and this work is his most celebrated painting in the genre.

What are the 2 types of still life photography?

There are two types of still life photography: found still life and created still life.

Are all sculptures three dimensional?

All sculpture is made of a material substance that has mass and exists in three-dimensional space. The mass of sculpture is thus the solid, material, space-occupying bulk that is contained within its surfaces.

-

1

still life

Персональный Сократ > still life

-

2

still life

жив.

He painted nothing but still life… (W. S. Maugham, ‘Complete Short Stories’, ‘Honolulu’) — Винтер не писал ничего, кроме натюрмортов…

Large English-Russian phrasebook > still life

-

3

still life

жив. нaтюpмopт [

этим. гoлл.

]

He painted nothing but still life (W. S. Maugham). Still lifes are traditionally composed from such domestic objects as flowers, crockery, books, candlesticks and food (The Economist)

Concise English-Russian phrasebook > still life

-

4

still life

Большой англо-русский и русско-английский словарь > still life

-

5

still-life

Большой англо-русский и русско-английский словарь > still-life

-

6

still life

НБАРС > still life

-

7

Still-Life

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > Still-Life

-

8

still life

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > still life

-

9

still-life

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > still-life

-

10

still life

[`stɪllaɪf]

натюрморт; создание, написание натюрморта

Англо-русский большой универсальный переводческий словарь > still life

-

11

still life

Новый англо-русский словарь > still life

-

12

still life

English-Russian dictionary of Arts > still life

-

13

still life

English-Russian dictionary of technical terms > still life

-

14

still life

[‘stɪlˌlaɪf]

натюрморт; создание, написание натюрморта

Англо-русский современный словарь > still life

-

15

still-life

Англо-русский словарь по рекламе > still-life

-

16

still life

English-Russian base dictionary > still life

-

17

still-life

English-Russian base dictionary > still-life

-

18

still life paint.

Англо-русский словарь Мюллера > still life paint.

-

19

still life painter

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > still life painter

-

20

still-life advertising

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > still-life advertising

Страницы

- Следующая →

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

См. также в других словарях:

-

Still Life — (англ. натюрморт): Содержание 1 В музыке 1.1 Альбомы 1.2 Композиции … Википедия

-