On October 5, 1957, the Soviet newspaper Pravda announced that the Soviet Union had launched a 184 pound object into Earth orbit. That first artificial satellite has since come to be known in the English-speaking world as Sputnik. In the West it is now widely assumed that the Soviets chose the word sputnik as the name for their satellite because it means “fellow traveler.” This is not what actually happened.

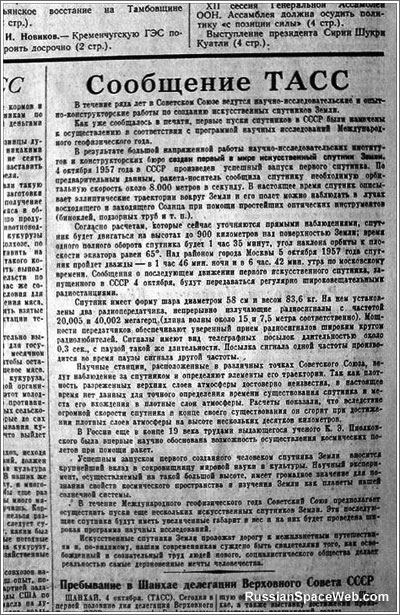

The world first heard about the launch from a brief report in Pravda. Though it was on the front page, it was not at all prominent, a few column inches in the middle right under the bland headline “Tass Report”. A few dry paragraphs spoke of a long-standing dream in the scientific community about the possibility of creating “an artificial Earth satellite.” Only in paragraph three did they come to the point, stating that the Soviet Union has brought this dream to fruition. The article went on to give a few facts and figures about the new satellite. No name for the satellite was mentioned.

Despite the fact that Pravda buried the lede, the announcement created an international sensation. Foreign papers repeated the announcement the same day in blaring full-width front page headlines. The next day, as Soviet leaders realized what a propaganda coupe this was, Pravda also dedicated the entire front page to coverage under the full-width headline “The World’s First Artificial Satellite of Earth Was Made in the Soviet Union!”. Articles above the fold included A Triumph of Soviet Science and Technology and The Most Impudent Dreams of Mankind Become Reality.

Today when we hear the word “satellite” we assume that a man-made object is meant, but in 1957 this needed to be made explicit. Up to then the word “satellite” primarily meant a natural satellites such the moons of Earth or Jupiter. The situation was similar in Russian. That is why Pravda had to spell out what was meant writing that this was an “artificial satellite of Earth”.

Because the concept of an “artificial satellite” had been purely theoretical and relatively obscure, there apparently was not yet a well-established term for such a device. For several days the Western press struggled with what to call it. In the first few days Pravda’s wordy “an artificial satellite of Earth” was used, but it was also called “the device” and even “the Red moon”. In Washington, a journalist named [can’t find the reference] was asked for suggestions for a less awkward description. He took the phrase искусcтвеyный спутник Земли (artificial satellite of Earth) from Pravda, kept only the key word, and left it untranslated: sputnik. The suggestion was soon widely adopted and Sputnik became the Western name of the Soviet satellite.

For several decades those writing about it in English continued to show awareness that Sputnik was an informal term for the spacecraft. For example, after the Soviet Union launched a second artificial satellite, an article in Scientific American discussed tracking them and included a graph with lines labeled Sputnik I and Sputnik II, but in the body of the article they were referred using translations of the Russian designations: The First Satellite and The Second Satellite.

“Sputnik” never attained the status of a proper name in Russian and probably never will since calling a sputnik “Sputnik” would be redundant and therefor silly. The Russian-language press continues to refer to Sputnik I simply as “the first artificial sputnik of Earth” (note the lower case) and to report on the launch of American sputniki.

So why do English speakers now believe that the Soviets named their satellite “Sputnik”? This misunderstanding seems to arise from the oft-repeated statement that sputnik means “fellow traveler”. This is taken to mean that the word sputnik was chosen as a fanciful name for the space craft. In reality what is being explained is the origin of the Russian word for astronomical satellites. The fanciful comparison was coined hundreds of years earlier to talk about moons. This confusion can be traced to an article in the New York Times of October 6, 1957 entitled Soviet ‘Sputnik’ Means A Traveler’s Traveler.

The English word “satellite” has a similar origin. It once meant an attendant of a person of importance. Imagine the confusion which could have occurred if the US had launched the first artificial satellite and neglected to name it. It is only a slight stretch to imagine the Soviet press writing, “the Americans named their sputnik Satellite which means ‘an entourage member’.”

In conclusion, the belief that the Soviets named their satellite Sputnik after the Russian word for “fellow traveler” is false even though that is the literal meaning of the word sputnik. They called it “sputnik” because that is the normal Russian word for satellite. Naming it “Sputnik” would have been silly. When they failed to name it at all the Western press stepped in and adopted the Russian word for satellite as its proper name in English.

Sources

- Сообщение ТАСС, Pravda, October 5, 1957 (scan)

- Сообщение ТАСС, Pravda, October 5, 1957 (as text)

-

Front page,

Pravda, October 6, 1957 -

TASS Report, Pravda, October 5, 1957

(English translation provided by NASA. Note the blurb at the top which repeats the myth that the Soviets named their satellite.) -

Soviet Fires Earth Satellite Into Space,

The New York Times, October 5, 1957

(Note that no name for the satellite is given and the word sputnik does not appear.) - Soviet ‘Sputnik’ Means A Traveler’s Traveler, New York Times, October 6, 1957, p 46

-

The aftermath of the Sputnik launch

(Source of the photographs of Pravda listed above) -

Sputnik and US Intelligence: The Warning Record,

Studies in Intelligence

(Includes a photograph of the front page of the October 5, 1957 New York Times.) - Sputnik 1, Wikipedia

-

Chronology of 1957: The Beginning of the Space Age

(Includes references to news coverage.) -

Memorandum of Conference with the President, October 9, 1957

(Now know as the Sputnik Memo this document describes a meeting of president Eisenhower and some of his advisers to discuss the satellite launch. In the memo the satellite is nameless, referred to as “the earth satellite”, “the Russian satellite”, and “the missile”. -

Описание в начале 1744 года явившейся кометы купно с некоторыми учиненными об ней рассуждениями, Gottfried Heinsius, translated by Mikhail Lomonosov

(Early use use of sputnik to refer to an orbiting body. Notes that a precise calculation of the extent of the atmosphere of the Great Comet of 1744 requires facts which we could learn only from observing the motions of a sputnik revolving around it. Sadly, the author notes, this is impossible because the comet has no sputnik.)

Shuba and glasnost: historical borrowings

One of the earliest borrowings from Russian was the word “sable” (from the Russian: sobol — a

carnivorous mammal of the Mustelidae family native to northern Europe and Asia). In the 12th-13th

centuries, this animal’s fur was a form of currency, and in 14th century English dictionaries the word

«sable’’ can be found. In addition to the meaning of the noun, it became an adjective for “black.”

A large number of Russian borrowings came to the English language in the 16th century, which was a

time of growing Russian-English trade and political relations. Many such words concerned traded goods:

Beluga — a type of whale or sturgeon

Starlet — a small sturgeon of the Danube basin and Caspian Sea; farmed and commercially fished for its flesh and caviar

Kvass — a fermented mildly alcoholic beverage made from rye flour or bread with malt; sometimes translated into English as “bread drink”

Shuba — a fur coat

Czar (or tsar) – Russia’s ruler until the 1917 Revolution

Ztarosta (starosta) — a title that designates an official or unofficial leader; the head of a community

(church starosta, or school starosta)

Moujik (muzhik) — a male peasant

In the 18th and 19th centuries, other Russian words originally specific to Russian history entered into

English. Nowadays, however, they mostly can be found only in historical works or books of fiction:

Ispravnik — the chief of the district police

Obrok – an annual tax formerly paid by a Russian peasant engaged in trade

Barshina — forced labor of peasants on a landlord’s land

In the 19th century, words related to the socialist and democratic movements in Russia entered into

English:

Decembrist — a participant of the uprising against Czar Nicholas I at the time of his accession in St.

Petersburg on Dec. 14, 1825

Nihilist, nihilism — a denial of the validity of traditional values and beliefs. The term spread after

publishing of the novel, Fathers and Sons (1862), by Russian writer Ivan Turgenev, where the main

character is the nihilist Bazarov.

Narodnik (from Russian “narod” — people) – a member of the 19th century rural socialist movement who

believed that political propaganda among the Russian peasantry would lead to the awakening of the

masses to challenge the czarist regime.

Intelligentsia – society’s intellectual elite

Of course, the words “nihilist,” “decembrist,” and “intelligentsia” are not truly Russian in origin and are

borrowed from Latin. However, these words came into English from Russian.

After the 1917 Revolution many Russian words appeared in many languages. Most are used to denote

completely new things and notions specific to Russia and Russian politics.

Here is a list of some well-known Russian words from the Soviet era:

Bolshevik (from Russian for “majority”) — a member of the majority faction of the Russian Social

Democratic Party, which was renamed the Communist Party after seizing power in the October

Revolution in 1917.

Samizdat — a system in the USSR and countries within its orbit by which forbidden literature was

clandestinely printed and distributed; also such literature

Soviet — a revolutionary council of workers or peasants in Russia before the Revolution; also, an elected

local, district, or national council in the former Soviet Union.

Sputnik (originally – “a traveling companion”) — the name given to a series of Soviet-era satellites; the

first objects launched into space

Cosmonaut — a Russian astronaut

Kolkhoz (abbreviation for Russian “kollektivnoye khozyaystvo”) – a cooperative agricultural enterprise

operated on state-owned land by peasants; a collective farm

Tovarishch — a companion or fellow traveler; used as a direct form of address in the Soviet Union;

equivalent to comrade

Gulag — originally an acronym for a Soviet-era system of forced-labor camps; it now can refer to any

repressive or coercive environment or situation

Apparatchik – the name given the Communist Party machine in the former Soviet Union; also a member

of the Communist Party and an official in a large organization, typically in a political one.

American

academic and author James Billington describes one as «a man not of grand plans, but of a hundred

carefully executed details.” It’s often considered a derogatory term, with negative connotations in terms

of the quality, competence, and attitude of a person thus described.

The words “pioneer” and “brigade” had existed in English, but they got new meanings as “a member of

the children’s Communist organization” and «labour collective» after the revolution in Russia. A new political regime in the 1990s created the new words, “glasnost” and “perestroika.”

Glasnost — an official policy in the former Soviet Union (especially associated with Mikhail Gorbachev)

emphasizing openness with regard to discussion of social problems and shortcomings.

Perestroika — a reform of the political and economic system of the former Soviet Union, first proposed

by Leonid Brezhnev at the 26th Communist Party Congress in 1979, and later actively promoted

by Mikhail Gorbachev starting in 1985.

Borscht and kazachoc: cultural borrowings

Other borrowings relate to Russian cultural and gastronomic traits.

Pelmeni — an Eastern European dumpling filled with minced meat, especially beef and pork, wrapped in

thin dough, and then boiled

Borscht (Borshch) — a beet soup served hot or cold, usually with sour cream

Kissel — a viscous fruit dish, popular as a dessert and as a drink

Vodka (barely needs to be introduced) — a distilled beverage composed primarily of water and ethanol,

sometimes with traces of impurities and flavorings, 40 percent alcohol by volume ABV (80 US proof).

Medovukha — a Russian honey-based alcoholic beverage similar to mead

Molotov cocktail — a makeshift bomb made of a breakable container filled with flammable liquid and

with a rag wick that is lighted just before being hurled. “Cocktail” named after Vyacheslav Molotov:

while dropping bombs on Helsinki, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov claimed the Soviets were

only dropping food and drink to their comrades.

Russian roulette — a very dangerous game of chance where each player points at their own head with

a gun that has one bullet in it and five empty chambers

Kazachoc (literally translated it means «Little Cossack») — A Slavic dance, chiefly Russian and Ukrainian,

with a fast tempo featuring a step in which a squatting dancer kicks out each leg alternately to the front.

Sambo — a Soviet martial art originally developed in the former Soviet Union. The word «SAMBO» is

an acronym for SAMozashchita Bez Oruzhiya, which literally translates as «self-defense without

weapons.»

You definitely have heard the Russian word “babushka.” When it entered into the English language, in

addition to its original meaning “grandmother,” it got another one: a type of scarf commonly worn by

babushkas.

After 1991, there were some new words such as “gopnik” or “silovik” still coming to other languages.

Gopnik — a pejorative term to describe a particular subculture in Russia and other Slavic countries that

refers to aggressive young men or women of the lower-class from families of poor education and

income, somewhat similar to American “white trash.”

Silovik — a word for state officials from the security or military services, often officers of the former KGB,

GRU, FSB, SVR, the Federal Drug Control or other security services who wield enormous political and

state power.

Some linguists even claim that one of the most popular verbs in modern English, “to talk,” has

Scandinavian roots — “tolk,” which is originally from the Russian “tolk,” “tolkovat”. And the word «milk»

was borrowed from Slavic tribes as «meolk,» and then as «milk.» There’s a similar story for other words

such as «honey» (Old English — meodu, Russian — mjod).

Try to guess the meaning of these words of Russian origin:

Shapka

Pirozhki (also piroshki)

Spetsnaz (or Specnaz)

Zek

Which Russian words have you met in other languages? Share your comments!

If using any of Russia Beyond’s content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Get the week’s best stories straight to your inbox

Here is a scan of the October 5, 1957 announcement from Pravda:

The first sentence reads:

В течение ряда лет в Советском Союзе ведутся научно-исседовательские и опытно-конструкторские работы по созданию искусственных спутников Земли.

This can be translated:

For many years now scientific research and the construction of prototypes has been going on in the Soviet Union with the goal of creating artificial Earth satellites.

Notice that the word спутник (satellite) is not capitalized and is qualified by the adjective искусственный (artificial). We could just as well have translated the last part thus:

…with the goal of creating artificial moons of the Earth.

The New York Times in its story the same day Soviet Fires Earth Satellite Into Space called it a moon three times starting in the third paragraph:

The official Soviet news agency Tass said the artificial moon, with a diameter of twenty-two inches and a weight of 184 pounds, was circling the earth once every hour and thirty-five minutes. This means more than fifteen times a day.

So on October 5, 1957 the word «спутник» was already well-understood to the Russian reader in the metaphorical sense of a moon, an object in orbit around a larger body.

Interestingly the article in the NYT does not use the word «sputnik» once. But the next day they ran a follow-up story about the Russian word entitled Soviet ‘Sputnik’ Means A Traveler’s Traveler. Within weeks the English-language press had adopted the Russian word as a proper noun and was referring to the first artificial satellite as «Sputnik I».

This process in which a Russian word was adopted into English with only its newest meaning preserved is not uncommon. It can happen to English words too when Russians borrow them.

For example a decade or two after Sputnik I the English word «sex» entered Russian, but only with a meaning which many Americans still considered slang. Today one can use секс to refer to the sex act, but would not be understood if we were to use it to say things like «the female sex» or «the battle of the sexes».

Another example is the word сепаратор (separator) which refers to a device used in a dairy.

This answer is based in two articles which I wrote earlier:

- Where Did Sputnik Get its Name

- False Friends

§ 2. Semantic Characteristics and Col-

responsible for the act of borrowing, and also because the borrowed words bear, as a rule, the imprint of the sound and graphic form, the morphological and semantic structure characteristic of the language they were borrowed from.

WORDS OF NATIVE ORIGIN

Words of native origin consist for the most part of very ancient ele- ments—Indo-European, Germanic and West Germanic cognates. The bulk of the Old English word-stock has been preserved, although some words have passed out of existence. When speaking about the role of the native element in the English language linguists usually confine themselves to the small Anglo-Saxon stock of words, which is estimated to make 25—30% of the English vocabulary.

To assign the native element its true place it is not so important to count the number of Anglo-Saxon words that have survived up to our days, as to study their semantic and stylistic character, their word-building ability, frequency value, collocability.

Almost all words of Anglo-Saxon origin belong to very important semantic groups. They include most of the auxiliary and modal

verbs (shall, will, must, can, may, etc.), pronouns (I, you, he, my, his, who, etc.), prepositions (in, out, on, under, etc.), numerals (one, two, three, four, etc.) and conjunctions (and, but, till, as, etc.). Notional words of Anglo-Saxon origin include such groups as words denoting parts of the body (head, hand, arm, back, etc.), members of the family and closest relatives (farther, mother, brother, son, wife), natural phenomena and planets (snow, rain, wind, sun, moon, star, etc.), animals (horse, cow, sheep, cat), qualities and properties (old, young, cold, hot, light, dark, long), common actions (do, make, go, come, see, hear, eat, etc.), etc.

Most of the native words have undergone great changes in their semantic structure, and as a result are nowadays polysemantic, e.g. the word finger does not only denote a part of a hand as in Old English, but also 1) the part of a glove covering one of the fingers, 2) a finger-like part in various machines, 3) a hand of a clock, 4) an index, 5) a unit of measurement. Highly polysemantic are the words man, head, hand, go, etc.

Most native words possess a wide range of lexical and grammatical valency. Many of them enter a number of phraseological units, e.g. the word heel enters the following units: heel over head or head over heels— ‘upside down’; cool one’s heel—’be kept waiting’; show a clean pair of heels, take to one’s heels—’run away’, turn on one’s heels— ‘turn sharply round’, etc.

§ 3. Derivational Potential The great stability and semantic peculiarities of Anglo-Saxon words account for their great

derivational potential. Most words of native origin make up large clusters of derived and compound words in the present-day language, e.g. the word wood is the basis for the formation of the following words: wooden, woody, wooded, woodcraft, woodcutter, woodwork and many

162

others. The formation of new words is greatly facilitated by the fact that most Anglo-Saxon words are root-words,

New words have been coined from Anglo-Saxon simple word-stems mainly by means of affixation, word-composition and conversion.

Some linguists contend that due to the large additions to its vocabulary from different languages, English lost much of its old faculty to form new words. The great number of compound and derived words in modern English, the diversity of their patterns, the stability and productivity of the patterns and the appearance of new ones testify to the contrary. Such affixes of native origin as -ness, -ish, -ed, un-, mis- make part of the patterns widely used to build numerous new words throughout the whole history of English, though some of them have changed their collocability or have become polysemantic, e.g. the agent-forming suffix -er, which was in Old English mostly added to noun-stems, is now most often combined with verb-stems, besides it has come to form also names of instruments, persons in a certain state or doing something at the moment.

Some native words were used as components of compounds so often that they have acquired the status of derivational affixes (e. g. -dom, — hood, -ly, over-, out-, under-), others are now semi-affixational morphemes.1.

It is noteworthy that to the native element in English we must also refer some new simple words based on words of Anglo-Saxon origin. Words with a new non-derived stem branch off from primary simple words as a result of simplification of some derivatives in a cluster of words and their semantic isolation, as in king, kind n, kind a and kin n, from which all of them were derived (ср. OE. cуninз, cynd, cynde, суn), or bless and bleed derived from blood (ср. OE. bledsian, blēdan, blōd). Sometimes a word split into two or more words with different forms and meanings (i.e. etymological doublets) due to the difference in function and stress, as is the case with off and of (from OE. of which was stressed as an adverb and unstressed as a preposition). Dialectal forms of a word may develop into independent words, as in one and an (< OE. an), whole and hale (< OE. hāl). New root-words based on Anglo-Saxon words also came into being with the rise of homonyms owing to the split of polysemy.2

The semantic characteristics, stability and wide collocability of native words account for their frequency in speech. However there are some words among them which are now archaic or poetic (e.g. lore, methinks, quoth, whilom, ere, welkin, etc.), or used only as historical terms (e.g. thane, yeoman denoting ranks, stocks — ‘an instrument of torture’, etc.).

What has been said above shows that the native element, has been playing a significant role in the English language. To fully estimate the importance of the native element in English, it is essential to study the role of English derivational means and semantic development in the life of borrowings, which will be dwelt upon in the sections below.

1 See ‘Word-Formation’, §§ 13, 14, pp. 123-125. 2 See ‘Semasiology’, § 40, p. 47.

§ 5. Causes and Ways of Borrowing

§ 4. Summary and Conclusions

1. The native element comprises not only the ancient Anglo-Saxon core but also words which appeared later as a result of word-

formation, split of polysemy and other processes operative in English.

2. Though not numerous in Modern English, words of Anglo-Saxon origin must be considered very important due to their marked stability, specific semantic characteristics, wide collocability, great derivational potential, wide spheres of application and high frequency value.

BORROWINGS

In its 15 century long history recorded in written manuscripts the English language happened to come in long and close contact

with several other languages, mainly Latin, French and Old Norse (or Scandinavian). The great influx of borrowings from these sources can be accounted for by a number of historical causes. Due to the great influence of the Roman civilisation Latin was for a long Уте used in England as the language of learning and religion. Old Norse was the language of the conquerors who were on the same level of social and cultural development and who merged rather easily with the local population in the 9th, 10th and the first half of the 11th century. French (to be more exact its Norman dialect) was the language of the other conquerors who brought with them a lot of new notions of a higher social system — developed feudalism, it was the language of upper classes, of official documents and school instruction from the middle of the 11th century to the end of the 14th century.

In the study of the borrowed element in English the main emphasis is as a rule placed on the Middle English period. Borrowings of later periods became the object of investigation only in recent years. These investigations have shown that the flow of borrowings has been steady and uninterrupted. The greatest number has come from French. They refer to various fields of social-political, scientific and cultural life. A large portion of borrowings (41%) is scientific and technical terms.

The number and character of borrowed words tell us of the relations between the peoples, the level of their culture, etc. It is for this reason that borrowings have often been called the milestones of history. Thus if we go through the lists of borrowings in English and arrange them in groups according to their meaning, we shall be able to obtain much valuable information with regard to England’s contacts with many nations. Some borrowings, however, cannot be explained by the direct influence of certain historical conditions, they do not come along with any new objects or ideas. Such were for instance the words air, place, brave, gay borrowed from French.

It must be pointed out that while the general historical causes of borrowing from different languages have been studied with a considerable degree of thoroughness the purely linguistic reasons for borrowing are still open to investigation.

164

The number and character of borrowings do not only depend on the historical conditions, on the nature and length of the contacts, but also on the degree of the genetic and structural proximity of languages concerned. The closer the languages, the deeper and more versatile is the influence. This largely accounts for the well-marked contrast between the French and the Scandinavian influence on the English language. Thus under the influence of the Scandinavian languages, which were closely related to Old English, some classes of words were borrowed that could not have been adopted from non-related or distantly related languages (the pronouns they, their, them, for instance); a number of Scandinavian borrowings were felt as derived from native words (they were of the same root and the connection between them was easily seen), e.g. drop (AS.) — drip (Scand.), true (AS.)-tryst (Scand.); the Scandinavian influence even accelerated to a certain degree the development of the grammatical structure of English.

Borrowings enter the language in two ways: through oral speech (by immediate contact between the peoples) and through written speech (by indirect contact through books, etc.).

Oral borrowing took place chiefly in the early periods of history, whereas in recent times written borrowing gained importance. Words borrowed orally (e.g. L. inch, mill, street) are usually short and they undergo considerable changes in the act of adoption. Written borrowings (e.g. Fr. communiqué, belles-lettres, naïveté) preserve their spelling and some peculiarities of their sound-form, their assimilation is a long and laborious process.

§ 6. Criteria of Borrowings Though borrowed words undergo changes in the adopting language they preserve some of

their former peculiarities for a comparatively long period. This makes it possible to work out some criteria for determining whether the word belongs to the borrowed element.

In some cases the pronunciation of the word (strange sounds, sound combinations, position of stress, etc.), its spelling and the correlation between sounds and letters are an indication of the foreign origin of the word. This is the case with waltz (G.),. psychology (Gr.), soufflé (Fr.), etc. The initial position of the sounds [v], [dз], [з] or of the letters x, j, z is a sure sign that the word has been borrowed, e.g. volcano (It.), vase (Fr.), vaccine

(L.), jungle (Hindi), gesture (L.), giant (OFr.), zeal (L.), zero (Fr.), zinc

(G.), etc.

The morphological structure of the word and its grammatical forms may also bear witness to the word being adopted from another language. Thus the suffixes in the words neurosis (Gr.) and violoncello (It.) betray the foreign origin of the words. The same is true of the irregular plural forms papyra (from papyrus, Gr.), pastorali (from pastorale, It.), beaux (from beau, Fr.), bacteria, (from bacterium, L.) and the like.

Last but not least is the lexical meaning of the word. Thus the concept denoted by the words ricksha(w), pagoda (Chin.) make us suppose that we deal with borrowings.

These criteria are not always helpful. Some early borrowings have become so thoroughly assimilated that they are unrecognisable without

165

a historical analysis, e.g. chalk, mile (L.), ill, ugly (Scand.), enemy, car (Fr.), etc. It must also be taken into consideration that the closer the relation between the languages, the more difficult it is to distinguish borrowings.

Sometimes the form of the word and its meaning in Modern English enable us to tell the immediate source of borrowing. Thus if the digraph ch is sounded as [∫], the word is a late French borrowing (as in echelon, chauffeur, chef); if it stands for [k], it came through Greek (archaic, architect, chronology); if it is pronounced as [t∫], it is either an early-borrowing (chase, OFr.; cherry, L., OFr.; chime, L.), or a word of Anglo-Saxon origin (choose, child, chin).

|

§ 7. Assimila- |

It is now essential to analyse the changes that |

|

|

borrowings have undergone in the English |

||

|

tion of Bor- |

||

|

selves to its peculiarities. |

language and how they have adapted them- |

|

All the changes that borrowed elements undergo may be divided into two large groups.

On the one hand there are changes specific of borrowed words only. These changes aim at adapting words of foreign origin to the norms of the borrowing language, e.g. the consonant combinations [pn], [ps], [pt] in the words pneumatics, psychology, Ptolemy of Greek origin were simplified into [n], [s], [t], since the consonant combinations [ps], [pt], [pn], very frequent at the end of English words (as in sleeps, stopped, etc.), were never used in the initial position. For the same reason the initial [ks] was changed into [z] (as in Gr. xylophone).

The suffixes -ar, -or, -ator in early Latin borrowings were replaced by the highly productive Old English suffix -ere, as in L. Caesar>OE. Casere, L. sutor>OE. sūtere.

By analogy with the great majority of nouns that form their plural in -s, borrowings, even very recent ones, have assumed this inflection instead of their original plural endings. The forms Soviets, bolsheviks, kolkhozes, sputniks illustrate the process.

On the other hand we observe changes that are characteristic of both borrowed and native words. These changes are due to the development of the word according to the laws of the given language. When the highly inflected Old English system of declension changed into the simpler system of Middle English, early borrowings conformed with the general rule. Under the influence of the so-called inflexional levelling borrowings like lазu, (MnE. law), fēōlaza (MnE. fellow), stræt (MnE. street), disc (MnE. dish) that had a number of grammatical forms in Old English acquired only three forms in Middle English: common case and possessive case singular and plural (fellow, fellowes, fellowes).

It is very important to discriminate between the two processes — the adaptation of borrowed material to the norms of the language and the development of these words according to the laws of the language.

This differentiation is not always easily discernible. In most cases we must resort to historical analysis before we can draw any definite conclusions. There is nothing in the form of the words procession and,

166

progression to show that the former was already used in England in the 11th century, the latter not till the 15th century. The history of these words reveals that the word procession has undergone a number of changes alongside with other English words (change in declension, accentuation, structure, sounds), whereas the word progression underwent some changes by analogy with the word procession and other similar words already at the time of its appearance in the language.

§ 8. Phonetic, Grammatical Since the process of assimilation of borrow- and Lexical Assimilation ings includes changes in sound-form, mor-

of Borrowings phological structure, grammar characteristics, meaning and usage Soviet linguists distinguish phonetic, grammatical and lexical assimilation of borrowings.

Phonetic assimilation comprising changes in sound-form and stress is perhaps the most conspicuous.

Sounds that were alien to the English language were fitted into its scheme of sounds. For instance, the long [e] and [ε] in recent French borrowings, alien to English speech, are rendered with the help of [ei] (as in the words communiqué, chaussée, café).

Familiar sounds or sound combinations the position of which was strange to the English language, were replaced by other sounds or sound combinations to make the words conform to the norms of the language, e.g. German spitz [∫pits] was turned into English [spits]. Substitution of native sounds for foreign ones usually takes place in the very act of borrowing. But some words retain their foreign pronunciation for a long time before the unfamiliar sounds are replaced by similar native sounds.

Even when a borrowed word seems at first sight to be identical in form with its immediate etymon as OE. skill < Scand. skil; OE. scinn < < Scand. skinn; OE. ran < Scand. ran the phonetic structure of the word undergoes some changes, since every language as well as every period in the history of a language is characterised by its own peculiarities in the articulation of sounds.

In words that were added to English from foreign sources, especially from French or Latin, the accent was gradually transferred to the first syllable. Thus words like honour, reason were accented on the same principle as the native father, mother.

Grammatical Assimilation. Usually as soon as words from other languages were introduced into English they lost their former grammatical categories and paradigms and acquired hew grammatical categories and paradigms by analogy with other English words, as in

|

им. спутник |

Com. sing. Sputnik |

|

род. спутника |

Poss. sing. Sputnik’s |

|

дат. спутнику |

Com. pl. Sputniks |

|

вин. спутник |

Poss. pl. Sputniks’ |

|

вин. спутником |

|

|

предл. о спутнике |

However, there are some words in Modern English that have for centuries retained their foreign inflexions. Thus a considerable group of

167

borrowed nouns, all of them terms or literary words adopted in the 16th century or later, have preserved their original plural inflexion to this day, e.g. phenomenon (L.) — phenomena; addendum (L.) — addenda; parenthesis (Gr.) — parentheses. Other borrowings of the same period have two plural forms — the native and the foreign, e.g. vacuum (L.) — vacua, vacuums, virtuoso (It.) — virtuosi, virtuosos.

All borrowings that were composite in structure in their native language appeared in English as indivisible simple words, unless there were already words with the same morphemes in it, e.g. in the word saunter the French infinitive inflexion -er is retained (cf. OFr. s’aunter), but it has changed its quality, it is preserved in all the other grammatical forms of the word (cf. saunters, sauntered, sauntering), which means that it has become part of the stem in English. The French reflexive pronoun s- has become fixed as an inseparable element of the word. The former Italian diminishing suffixes -etto, -otta, -ello(a), -cello in the words ballot, stiletto, umbrella cannot be distinguished without special historical analysis, unless one knows the Italian language. The composite nature of the word portfolio is not seen either (cf. It. portafogli < porta — imperative of ‘carry’ + fogli — ’sheets of paper’). This loss of morphological seams in borrowings may be termed simplification by analogy with a similar process in native words.1

It must be borne in mind that when there appears in a language a group of borrowed words built on the same pattern or containing the same morphemes, the morphological structure of the words becomes apparent and in the course of time their word-building elements can be employed to form new words.2 Thus the word bolshevik was at first indivisible in English, which is seen from the forms bolshevikism, bolshevikise, bolshevikian entered by some dictionaries. Later on the word came to be divided into the morphological elements bolshev-ik. The new morphological division can be accounted for by the existence of a number of words containing these elements (bolshevism, bolshevist, bolshevise; sputnik, udarnik, menshevik).

Sometimes in borrowed words foreign affixes are replaced by those available in the English language, e.g. the inflexion -us in Latin adjectives was replaced in English with the suffixes -ous or -al: L. barbarus > > E. barbarous; L. botanicus > E. botanical; L. balneus > E. balneal.

Lexical Assimilation. When a word is taken over into another language, its semantic structure as a rule undergoes great changes.

Polysemantic words are usually adopted only in one or two of their meanings. Thus the word timbre that had a number of meanings in French was borrowed into English as a musical term only. The words cargo and cask, highly polysemantic in Spanish, were adopted only in one of their meanings — ‘the goods carried in a ship’, ‘a barrel for holding liquids’ respectively.

• In some cases we can observe specialisation of meaning, as in the word hangar, denoting a building in which aeroplanes are kept (in French

1 See ‘Word-Structure’, § 13, p. 105; ‘Word-Formation’, § 34, p. 151. 2 See ‘Word-Formation’, § 14, p. 125.

168

it meant simply ’shed’) and revue, which had the meaning of ‘review’ in French and came to denote a kind of theatrical entertainment in English.

In the process of its historical development a borrowing sometimes acquired new meanings that were not to be found in its former semantic structure. For instance, the verb move in Modern English has developed the meanings of ‘propose’, ‘change one’s flat’, ‘mix with people’ and others that the French mouvoir does not possess. The word scope, which originally had the meaning of ‘aim, purpose’, now means ‘ability to understand’, ‘the field within which an activity takes place, sphere’, ‘opportunity, freedom of action’. As a rule the development of new meanings takes place 50 — 100 years after the word is borrowed.

The semantic structure of borrowings changes in other ways as well. Some meanings become more general, others more specialised, etc. For instance, the word terrorist, that was taken over from French in the meaning of ‘Jacobin’, widened its meaning to ‘one who governs, or opposes a government by violent means’. The word umbrella, borrowed in the meaning of a ’sunshade’ or ‘parasol’ (from It. ombrella <ombra — ’shade1) came to denote similar protection from the rain as well.

Usually the primary meaning of a borrowed word is retained throughout its history, but sometimes it becomes a secondary meaning. Thus the Scandinavian borrowings wing, root, take and many others have retained their primary meanings to the present day, whereas in the OE. fēolaze (MnE. fellow) which was borrowed from the same source in the meaning of ‘comrade, companion’, the primary meaning has receded to the background and was replaced by the meaning that appeared in New English ‘a man or a boy’.

Sometimes change of meaning is the result of associating borrowed words with familiar words which somewhat resemble them in sound but which are not at all related. This process, which is termed f o l k e t y — m o l o g y , often changes the form of the word in whole or in part, so as to bring it nearer to the word or words with which it is thought to be connected, e.g. the French verb sur(o)under had the meaning of ‘overflow’. In English -r(o)under was associated by mistake with round — круглый and the verb was interpreted as meaning ‘enclose on all sides, encircle’

(MnE. surround). Old French estandard (L. estendere — ‘to spread’) had the meaning of ‘a flag, banner’. In English the first part was wrongly associated with the verb stand and the word standard also acquired the meaning of ’something stable, officially accepted’.

Folk-etymologisation is a slow process; people first attempt to give the foreign borrowing its foreign pronunciation, but gradually popular use evolves a new pronunciation and spelling.

Another phenomenon which must also receive special attention is the f o r m a t i o n of d e r i v a t i v e s from borrowed word-stems. New derivatives are usually formed with the help of productive affixes, often of Anglo-Saxon origin. For instance: faintness, closeness, easily, nobly, etc. As a rule derivatives begin to appear rather soon after the borrowing of the word. Thus almost immediately after the borrowing of the word sputnik the words pre-sputnik, sputnikist, sputnikked, to outsputnik were coined in English.

169

§ 9. Degree of Assimilation and Factors Determining It

Many derivatives were formed by means of conversion, as in to manifesto (1748) < manifesto (It., 1644); to encore (1748) < encore (Fr.,

1712); to coach (1612) < coach (Fr., 1556).

Similarly hybrid compounds were formed, e. g. faint-hearted, illtempered, painstaking.

Even a superficial examination of borrowed words in the English word-stock shows that there are words among them that are easily

recognised as foreign (such as decolleté, façade, Zeitgeist, voile) and there are others that have become so firmly rooted in the language, so thoroughly assimilated that it is sometimes” extremely difficult to distinguish them from words of Anglo-Saxon origin (these are words like pupil, master, city, river, etc.).

Unassimilated words differ from assimilated ones in their pronunciation, spelling, semantic structure, frequency and sphere of application. However, there is no distinct border-line between the two groups. There are also words assimilated in some respects and unassimilated in others, they may be called partially assimilated. Such are communiqué, détente not yet assimilated phonetically, phenomenon (pl. phenomena), graffito (pl. graffiti) unassimilated grammatically, etc. So far no linguist has been able to suggest more or less comprehensive criteria for determining the degree of assimilation of borrowings.

The degree of assimilation depends in the first place upon the time of borrowing. The general principle is: the older the borrowing, the more thoroughly it tends to follow normal English habits of accentuation, pronunciation, etc. It is natural that the bulk of early borrowings have acquired full English citizenship and that most English speaking people are astonished on first hearing, that such everyday words as window, chair, dish, box have not always belonged to their language. Late borrowings often retain their foreign peculiarities.

However mere age is not the sole factor. Not only borrowings long in use, but also those of recent date may be completely made over to conform to English patterns if they are widely and popularly employed. Words that are rarely used in everyday speech, that are known to a small group of people retain their foreign -peculiarities. Thus many 19th century French borrowings have been completely assimilated (e.g. turbine, clinic, exploitation, diplomat), whereas the words adopted much earlier noblesse [no’bles] (ME.), ennui [ã:’nwi:] (1667), eclat [ei’kla:] (1674) have not been assimilated even in point of pronunciation.

Another factor determining the process of assimilation is the way in which the borrowing was taken over into the language. Words borrowed orally are assimilated more readily, they undergo greater changes, whereas with words adopted through writing the process of assimilation is longer and more laborious.

1.Due to “the specific historical development

§10. Summary and Conclusions of English, it has adopted many words from

other languages, especially from Latin, French and Old Scandinavian, though the number and importance of these borrowings are usually overestimated.

170

§ 1 1 . The Role of Native and Borrowed Elements

2.The number and character of borrowings in Modern English from various languages depend on the historical conditions and also on the degree of the genetic and structural proximity of the languages in question.

3.Borrowings enter the language through oral speech (mainly in early periods of history) and through written speech (mostly in recent times).

4.In the English language borrowings may be discovered through some peculiarities in pronunciation, spelling, morphological and semantic structures. Sometimes these peculiarities enable us even to discover the immediate source of borrowing.

5.All borrowed words undergo the process of assimilation, i.e. they adjust themselves to the phonetic and lexico-grammatical norms of the language. Phonetic assimilation comprises substitution of native sounds and sound combinations for strange ones and for familiar sounds used in a position strange to the English language, as well as shift of stress. Grammatical assimilation finds expression in the change of grammatical categories and paradigms of borrowed words, change of their morphological structure. Lexical assimilation includes changes in semantic structure and the formation of derivatives,

6.Substitution of sounds, formation of new grammatical categories and paradigms, morphological simplification and narrowing of meaning take place in the very act of borrowing. Some words however retain foreign sounds and inflexions for a long time. Shift of stress is a long and gradual process; the same is true of the development of new meanings in a borrowed word, while the formation of derivatives may occur soon after the adoption of the word.

7.The degree of assimilation depends on the time of borrowing, the extent to which the word is used in the language and the way of borrowing.

INTERRELATION BETWEEN NATIVE

AND BORROWED ELEMENTS

The number of borrowings in Old English was meagre. In the Middle English period there was an influx of loans. It is often con-

tended that since the Norman conquest borrowing has been the chief factor in the enrichment of the English vocabulary and as a result there was a sharp decline in the productivity of word-formation.1 Historical evidence, however, testifies to the fact that throughout its entire history, even in the periods of the mightiest influxes of borrowings, other processes, no less intense, were in operation — word-formation and semantic development, which involved both native and borrowed elements.

If the estimation of the role of borrowings is based on the study of words recorded in the dictionary, it is easy to overestimate the effect of the loan words, as the number of native words is extremely small

1 See ‘Etymological Survey …’, § 3, p. 162.

171

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #