First time? Quick how-to.

This visual quick how-to guide shows you how to search a word, for example «handspeak».

- All

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

Search Tips and Pointers

Search/Filter: Enter a keyword in the filter/search box to see a list of available words with the «All» selection. Click on the page number if needed. Click on the blue link to look up the word. For best result, enter a partial word to see variations of the word.

Alphabetical letters: It’s useful for 1) a single-letter word (such as A, B, etc.) and 2) very short words (e.g. «to», «he», etc.) to narrow down the words and pages in the list.

For best result, enter a short word in the search box, then select the alphetical letter (and page number if needed), and click on the blue link.

Don’t forget to click «All» back when you search another word with a different initial letter.

If you cannot find (perhaps overlook) a word but you can still see a list of links, then keep looking until the links disappear! Sharpening your eye or maybe refine your alphabetical index skill.

Add a Word: This dictionary is not exhaustive; ASL signs are constantly added to the dictionary. If you don’t find a word/sign, you can send your request (only if a single link doesn’t show in the result).

Videos: The first video may be NOT the answer you’re looking for. There are several signs for different meanings, contexts, and/or variations. Browsing all the way down to the next search box is highly recommended.

Video speed: Signing too fast in the videos? See HELP in the footer.

ASL has its own grammar and structure in sentences that works differently from English. For plurals, verb inflections, word order, etc., learn grammar in the «ASL Learn» section. For search in the dictionary, use the present-time verbs and base words. If you look for «said», look up the word «say». Likewise, if you look for an adjective word, try the noun or vice versa. E.g. The ASL signs for French and France are the same. If you look for a plural word, use a singular word.

Are you a Deaf artist, author, traveler, etc. etc.?

Some of the word entries in the ASL dictionary feature Deaf stories or anecdotes, arts, photographs, quotes, etc. to educate and to inspire, and to be preserved in Deaf/ASL history, and to expose and recognize Deaf works, talents, experiences, joys and pains, and successes.

If you’re a Deaf artist, book author, or creative and would like your work to be considered for a possible mention on this website/webapp, introduce yourself and your works. Are you a Deaf mother/father, traveler, politician, teacher, etc. etc. and have an inspirational story, anecdote, or bragging rights to share — tiny or big doesn’t matter, you’re welcome to email it. Codas are also welcome.

Hearing ASL student, who might have stories or anecdotes, also are welcome to share.

ASL to English reverse dictionary

Don’t know what a sign mean? Search ASL to English reverse dictionary to find what an ASL sign means.

Vocabulary building

To start with the First 100 ASL signs for beginners, and continue with the Second 100 ASL signs, and further with the Third 100 ASL signs.

Language Building

Learning ASL words does not equate with learning the language. Learn the language beyond sign language words.

Contextual meaning: Some ASL signs in the dictionary may not mean the same in different contexts and/or ASL sentences. A meaning of a word or phrase can change in sentences and contexts. You will see some examples in video sentences.

Grammar: Many ASL words, especially verbs, in the dictionary are a «base»; be aware that many of them can be grammatically inflected within ASL sentences. Some entries have sentence examples.

Sign production (pronunciation): A change or modification of one of the parameters of the sign, such as handshape, movement, palm orientation, location, and non-manual signals (e.g. facial expressions) can change a meaning or a subtle variety of meaning. Or mispronunciation.

Variation: Some ASL signs have regional (and generational) variations across North America. Some common variations are included as much as possible, but for specifically local variations, interact with your local community to learn their local variations.

Fingerspelling: When there is no word in one language, borrowing is a loanword from another language. In sign language, manual alphabet is used to represent a word of the spoken/written language.

American Sign Language (ASL) is very much alive and indefinitely constructable as any spoken language. The best way to use ASL right is to immerse in daily language interactions and conversations with Ameslan/Deaf people (or ASLians).

Sentence building

Browse phrases and sentences to learn sign language, specifically vocabulary, grammar, and how its sentence structure works.

Sign Language Dictionary

According to the archives online, did you know that this dictionary is the oldest sign language dictonary online since 1997 (DWW which was renamed to Handspeak in 2000)?

This dictionary is not exhaustive; the ASL signs are constantly added to the dictionary. If you don’t find the word/sign, you can send your request via email. Browse the alphabetical letters or search a signed word above.

Regional variation: there may be regional variations of some ASL words across the regions of North America.

Inflection: most ASL words in the dictionary are a «base», but many of them are grammatically inflectable within ASL sentences.

Contextual meaning: These ASL signs in the dictionary may not mean the same in different contexts and/or ASL sentences. You will see some examples in video sentences.

ASL is very much alive and indefinitely constructable as any spoken language. The best way to use ASL right is to immerse in daily interaction with Deaf Ameslan people (ASLers).

How to sign: inside an enclosed space

Your browser does not support HTML5 video.

Your browser does not support HTML5 video.

Your browser does not support HTML5 video.

in — SignLanguageStudent

Embed this video

Your browser does not support HTML5 video.

In — ASL Study

Embed this video

Your browser does not support HTML5 video.

in — SMARTSign Dictionary

Embed this video

Your browser does not support HTML5 video.

In — Linguistics Girl

Embed this video

IN

How to sign: a state in midwestern United States

Your browser does not support HTML5 video.

Indiana — ASL Study

Embed this video

Your browser does not support HTML5 video.

Your browser does not support HTML5 video.

Indiana — Marie Katzenbach School for the Deaf More details

Embed this video

Your browser does not support HTML5 video.

indiana — SMARTSign Dictionary

Embed this video

Similiar / Same: Indiana, Hoosier State

Categories: American state

Today I’m delighted to feature a guest post from Kristine about American Sign Language (ASL).

You’ll learn about:

- What ASL is and how it developed

- 5 common misconceptions people have about ASL

- Some similarities between ASL and English

- How learning ASL is different from learning English

Here’s Kristine…

What Is American Sign Language (ASL)?

ASL, short for American Sign Language, is the sign language most commonly used in, you guessed it, the United States and Canada.

Approximately 250,000 – 500,000 people of all ages throughout the US and Canada use this language to communicate as their native language. ASL is the third most commonly used language in the United States, after English and Spanish.

Contrary to popular belief, ASL is not representative of English nor is it some sort of imitation of spoken English that you and I use on a day-to-day basis. For many, it will come as a great surprise that ASL has more similarities to spoken Japanese and Navajo than to English.

When we discuss ASL or any other type of sign language, we are referring to what is called a visual-gestural language. The visual component refers to the use of body movements versus sound.

Because “listeners” must use their eyes to “receive” the information, this language was specifically created to be easily recognized by the eyes. The “gestural” component refers to the body movements or “signs” that are performed to convey a message.

A Brief History Of ASL

ASL is a relatively new language, which first appeared in the 1800s with the founding of the first successful American School for the Deaf by Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet.

With strong roots in French Sign Language, ASL evolved to incorporate the signs students would use in less formal occasions such as in their home or within the deaf community.

As students graduated from the American School for the Deaf, some went on to open up their own schools, passing along this evolving American Sign Language as the contact language for the deaf in the United States.

Is There A Universal Sign Language?

There is no universal language for the deaf – all over the world, different sign languages have developed that vary from one another.

A spoken English speaker from the USA, for example, can generally understand someone from another English speaking nation such as England or Australia.

But with sign language, someone who signs using American Sign language would not be able to understand someone who signs using British Sign Language (BSL) or even Australian Auslan.

5 Common Misconceptions About ASL

Like any foreign language, ASL falls victim to many misconceptions among those who have not explored the language.

Because of the word ‘American’ in its name, many assume it shares the same qualities as English and is simply a representation of English using hands and gestures.

However, this is not the case. Let’s take a look at 5 of the most common misconceptions about ASL:

Misconception #1: ASL Is “English On The Hands”

As you’ve probably realised by now, ASL actually has little in common with spoken English, nor is it some sort of signed representation of English words.

ASL was formed independently of English and has its own unique sentence structure and symbols for various words and ideas.

The key features of ASL are:

- hand shape

- palm orientation

- hand movement

- hand location

- gestural features like facial expression and posture

When English is used through fingerspelling, hand motions represent the English alphabet to spell words in English, but this is not actually a part of ASL. Rather, it’s a separate element of signed communication.

Misconception #2: ASL Is Shorthand

Another common misconception about ASL is that it is some form of shorthand, or rapid communication by means of abbreviations and symbols.

This misconception arises due to the fact that ASL does not have a written component.

To call ASL shorthand is sorely incorrect, as ASL is a complex language system with its own set of linguistic components.

Misconception #3: ASL Is Most Like British Sign Language

Although the United States and the United Kingdom share spoken English as their predominant language, American Sign Language and British Sign Language vary greatly.

In fact, American Sign Language has its roots in French Sign Language, while British Sign Language has had a greater influence on the development of Australian Auslan and New Zealand Sign Language.

Misconception #4: ASL Is Finger Spelling

In ASL, fingerspelling is reserved for borrowing words from the English language for proper nouns and technical terms with no ASL equivalent.

For example, fingerspelling can be used for people’s names, places, titles, and brands.

When fingerspelling is used in ASL, it’s done using the American Fingerspelled Alphabet. This alphabet has 22 handshapes, that, when held in certain positions or movements represent the 26 letters of the English alphabet.

Misconception #5: Lip Reading Is An Effective Alternative To Learning Sign Language

It’s estimated that only 30% of English can be read on the lips by the deaf.

Lip reading is also not an effective because it’s a one-way method of communication.

It’s very unlikely that the speaker will be nearly as skilled at lip reading as those who are fluent in ASL, as learning to lip read well can take years upon years of practice.

This means that lip reading is not an effective method for two-way communication.

How Is Learning ASL Similar To Learning English?

Now that we’ve cleared up some of the misconceptions about ASL, let’s look at some of the similarities that ASL and English do share:

Both English And ASL Are Natural Languages

Both ASL and English are defined as “natural languages” meaning they were created and spread through people using them, without conscious planning or premeditation.

Artificial languages, on the other hand, are communication systems which have been consciously created or invented and do not develop and change naturally.

Some artificial systems that were invented for deaf children include:

- lip reading

- cued speech

- signed English

- manually coded English.

With any natural language, immersion is the surest way to ensure fluency and American Sign Language is no different.

This means surrounding yourself with the ASL/Deaf community to help expose yourself to the context, culture, behaviours, and grammatical rules of the language.

Both ASL And English Activate The Same Area Of The Brain

When an ASL signer sees and processes an ASL sentence, the same part of the brain – the left hemisphere – is activated as when an English speaker listens to or reads an English sentence.

This is because even though language exists in different forms, all of them are based on symbolic representation. These symbols can visual or aural but they are still processed in the same part of the brain.

Both Require Building Words To Form Sentences

Signed languages have similar grammatical characteristics as spoken languages.

Just as sounds are linked to form syllables and words in a spoken language, signs can be built through various gestures and hand shapes, positions, and movements.

ASL has the same basic set of word types as spoken English does, including nouns, verbs, adjectives, pronouns, and adverbs.

How Is Learning ASL Different To Learning English?

In this article, I’ve compared many of the similarities between ASL and English, but how do the two differ for those trying to learn them?

Visual Language vs. Auditory Language

The first and most obvious difference between learning ASL and English is the medium you use for your learning – your eyes or your ears.

This may help to make ASL easier for people who are visual learners.

Similarly, if you are more of an auditory learner, you will probably find learning English or other spoken languages easier to pick up than sign language.

ASL Requires Gestural Movements Never Used In Spoken Language

Learning how to communicate through ASL and other sign languages requires a movement of body parts that most spoken-language speakers may not be used to.

These gestures include hand, arm, eye, and even facial expressions.

Just like the sounds of a new spoken language can take some getting used to for beginners, these gestures can be challenging for new learners of sign language to pick up.

ASL Is More Conceptual Than Spoken Languages

When making a connection between a sign and its intended meaning in ASL, it can be easier to comprehend the words meaning than in a spoken language.

For example, in ASL, the word book is signed with both hands gesturing the opening of a book.

The word “book” in English, however, does not conjure such an image. You either know what it means or you don’t and it’s hard to guess if you’re not sure.

Not all signs look like what they”re representing, but these conceptual connections are definitely more common than in spoken language.

ASL, because it’s visual, is a deeply conceptual language.

Because of this, the object of the sentence is signed first. For example, the English statement “The boy skipped home” would be reordered in ASL, starting with ‘home’ and then introducing the boy skipping.

ASL Has A Different Word Order Than English

As an English-speaker learning ASL, you may find the word order a bit tricky to get used to.

In ASL, how you assemble sentences following a different pattern, based on content.

When using indirect objects in ASL, you place the object right after the subject and then show the action. Lets look at an example:

- English: The boy throws a frisbee

- ASL: Boy — frisbee — throw

Tenses Are Represented Differently In ASL

In English, verbs are changed to show their tense, using the suffixes -ed, -ing and -s.

In ASL, tenses are shown differently.

Rather than conjugating the verbs, tense is established with a separate sign.

To represent the present tense, no change is made to the signs.

However, to sign past tense, you sign “finish” at chest level either before or after you finish your sentence.

Signing the future tense is quite similar to signing past tense. It’s indicated with a sign either before or at the end of the sentence as well as by adding “will” at the end of the sentence.

One interesting difference in the future tense, however, is that how far away from your body you sign the word “will” indicates how far in the future the sentence is.

As you can see, learning ASL is quite similar to learning any natural language.

Are You Thinking Of Learning ASL?

Every language has its own set of rules and grammar and ASL is no different.

While these rules and grammar are different are quite different from what we’re used to in English, they’re not particularly difficult to learn.

Like any language, getting the hang of ASL simply requires lots of practice and determination. You just need to get started.

If you’re currently thinking about learning a new language, you should consider giving ASL a try. I think you’ll find that it’s not only a fun and interesting language to learn but an incredibly enjoyable one too.

Are you interested in learning ASL or another form of sign language? Why do you want to learn sign language and what signs or topics do you most want to learn about? Let us know in the comments below!

This is a guest post by Kristine Thorndyke. Kristine is an English teacher who believes in improving lives through education. When shes not teaching, you can find her creating helpful resources for standardized testing at Test Prep Nerds.

ASL 1 – Unit 1

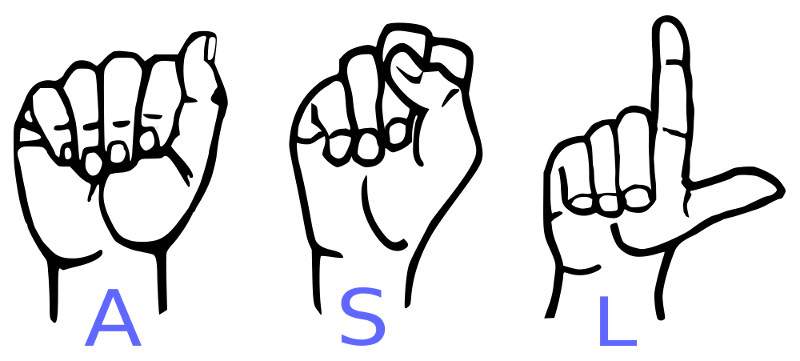

In this unit of the free sign language class, you will be learning how to fingerspell.

Vocabulary

First Signs

Visit the Online Course Vocabulary Category for this unit to view videos of these phrases and vocabulary words.

Phrases

- Good afternoon

- Good morning

- Goodbye

- Goodnight

- Hello

- How are you?

- My name is Deborah (name sign).

- Nice to meet you.

- Thank you.

- What is your name?

- You’re welcome.

Vocabulary

- AGAIN

- ASL Alphabet (A-Z)

- BOY

- DEAF

- GIRL

- HEARING

- HELP

- HOW

- I/ME

- KNOW

- MAN

- ME

- MY

- MY/MINE

- NEED

- NO

- NONE

- NOT

- PLEASE

- RIGHT

- SIGN

- SORRY

- THAT

- WANT

- WHAT

- WHEN

- WHERE

- WHO

- WHY

- WOMAN

- YES

- YOU

- YOUR

Conversation

Read this outline, and then watch the conversation in action on the video clip. Try to recognize what is being said. Watch the video again until you can follow the conversation without the outline.

A: HELLO MY NAME fs-CRIS. YOUR NAME WHAT?

“Hi, my name is Cris. What is your name?”

B: MY NAME fs-CHRISTINE. NICE MEET YOU.

“My name is Christine. Nice to meet you.”

A: NICE MEET-you SAME

“Nice to meet you too.”

Conversation Explained

HELLO MY NAME fs-CRIS.

“Hi, my name is Cris.”

In the first sentence, you will notice that names are fingerspelled, as you probably already knew. The word “is” is not signed because state-of-being verbs are not necessary in ASL. You will learn more about these verbs in Unit 9.

YOUR NAME WHAT?

“What is your name?”

This, as you will learn in Unit 6 of this free sign language class, is a wh-word question. These are questions that require more than a yes or no answer and normally use the words who, what, when, where, why, or how. Wh-word questions are signed with a specific facial expression that includes lowering your eyebrows. There are many possible word orders in ASL, but wh-word questions are always signed with the wh-word at the end of the sentence.

NICE MEET-you SAME.

“Nice to meet you too.”

This is a common phrase used in ASL when meeting someone for the first time. MEET is a directional verb, so signing the word YOU is not always necessary as it is included in the verb. You will learn more about directional verbs in Unit 8. The sign SAME can translate to “too” in English. This sign can also be a directional verb. Signing SAME between people means it is those people who are similar.

Fingerspelling

Fingerspelling means spelling out words by using signs that correspond to the letters of the word. The signs that are used in ASL are from the American Manual Alphabet. This alphabet uses 22 handshapes in different positions or with certain movements to represent the 26 letters of the American alphabet.

Fingerspelling is only used about 10% of the time and is primarily used for:

- People’s names

- Brand names

- Book and movie titles

- City and state names

Try not to use fingerspelling as your first choice when you don’t know the sign. Instead, attempt to get your point across by combining other signs or using some other method.

However, there are many words that do not have corresponding signs in ASL. Go ahead and fingerspell if there is no other convenient way to explain what you are talking about.

Here are some tips for accurate fingerspelling:

- Keep your hand relaxed, to the right of your face (to the left if you are left handed), and below your chin.

- Make sure your palm is facing the person you are talking to.

- Keep your elbow down and close to your body.

- Do not say or mouth the letters.

- Aim for articulation, not speed. Right now, you just want to make sure you form the letters correctly so people will understand you.

- Try not to bounce your hand as you spell, or you will make someone very dizzy! Also allow a slight pause between words.

- For words with double letters, open your hand slightly between the letters. For open letters such as B and L, move your hand slightly to the right with a very slight bounce for the second letter.

- When reading fingerspelling, make sure you look at the whole word, and not just the individual letters (just like in printed English). Look at the handshapes and movement. This will get you used to seeing words signed faster and faster. Some deaf people don’t even fingerspell all the letters of a word.

Being able to sign and understand fingerspelling is very important when you are new to sign language and haven’t learned a lot of signs. You will find that the more fluent you become in ASL, the less you will be relying on fingerspelling.

Fingerspelling Assignment

Turn to page 3 in your workbook and learn the manual alphabet. Try your best to memorize it.

In the video below, I will demonstrate the letters of the manual alphabet:

Sign with me during the video, and then try to sign the whole alphabet without the video. If you get stuck, look at only that letter on your printed manual alphabet, and keep going from memory. Try to learn the whole alphabet before moving on to the next unit of this free sign language class.

Reading Assignment

In DJSC! A Student’s Guide to ASL and the Deaf Community, read the Introduction, How to Use this Book, and all of Step 1: Start Learning American Sign Language. These readings will get you started with the book as well as discuss more about ASL as well as the best ways to learn ASL. This information is very important as you start learning ASL so you can make sure you’re getting the best ASL education possible.

In DJSC! A Student’s Guide to Mastering ASL Grammar, read the Introduction, How to Use This Book, Chapter 1 (Introduction to American Sign Language), and Chapter 2, Section 2.1 (Fingerspelling). These readings will get you started with the book as well as go more in-depth about fingerspelling.

End of Unit 1

Good job! No, really, give yourself a pat on the back. You just completed your first lessons in the free sign language class. That’s a huge step because some people talk about it, but never even start. You’re well on your way to being able to have a full-blown conversation in American Sign Language!

ASL Grammar:

A

«grammar» is a set of rules for using a language. These rules guide users

in the correct speaking or signing of a language.

The

grammar of a language is decided by the group of people who use the

language. New grammar rules come into existence when enough members of the

group have spoken (signed) their language a particular way often enough and

long enough that it would seem odd to speak the language in some other way.

American Sign Language is tied to the Deaf Community. We use our language

in a certain way. That «certain way» is what constitutes ASL grammar.

American Sign Language has its own grammar system that is different in many

ways from that of English. What this means is ASL grammar has its own rules for how

signs are built (phonology),

what signs mean (morphology), the order in which signs should be signed (syntax),

and the way context influences signing (pragmatics).

ASL

Word Order:

Instead of the phrase «word order» let’s instead use the phrase «sign

order.» How signs (or words) are arranged in a well-formed sentence is

sometimes referred to as syntax. So when we are discussing the proper

order of ASL signs we are discussing «ASL syntax.»

ASL

uses multiple different «sign orders» (not just one) depending

on what is needed.

Which sign order is appropriate depends on the context. For example

your your audience’s

familiarity with the topic, what you have already stated about the topic,

and any environmental clues or resources that can be used to help establish

meaning. Proper syntax also depends on what you are trying to do: explain, remind,

confirm, negate, cause to consider, ask a question, etc.

Contrary to what many ASL teachers claim, typical

signed sentences tend to be expressed in subject-verb-object order (or just

subject-verb order if there is no object).

Remember ASL has more than one right word (sign) order (like all human

languages).

Sometimes ASL sentences are expressed in object-subject-verb order (but not

as often as the basic SVO order). (See:

The Myth of «Store I Go.»)

ASL generally does not use «state of being» verbs

(am, is, are, was, were — sometimes referred to as «be verbs»).

ASL also does not tend to use separate specific signs for articles (a, an, the).

ASL tends to establish tense early on during sentences that are not present

tense. In other words, when discussing past and future events we tend to establish

a time-frame before the rest of the sentence. It is common to put a

time sign (if there is one in the sentence being used to indicate tense) at

the beginning of the sentence. For example: WEEK-PAST I WASH MY CAR sentence format.

Someone, for example, «Bob» — may try to tell you that «Actually it should

be WEEK-PAST, MY CAR, I WASH.» While Bob means well, and is not

entirely wrong — he is likely parroting the myths he was fed by his ASL 1

instructor without having observed or studied how actual Deaf people

converse with each other on a daily basis in real life.

Again I’m

cluing you in: The most common sign order in ASL is subject-verb-object.

(If you want to be anal retentive about it and not take my word and want me

to back that up, see

American

Sign Language: «subject-verb-object»).

Yes, yes, quite often ASL signers do use the object-subject-verb (OSV)

format. For example, MY CAR? WEEK-PAST I WASH!

However I am going to again emphasize to you that ASL has more than one sign order.

I keep emphasizing it because I’ve seen too many ASL as a second language

learners trying to sign every sentence using object-subject-verb (OSV)

order (which isn’t even the most common sign order in everyday ASL signing). If you

are signing everything in OSV format you’ll look like an unfortunate recent graduate of an ASL

program in which the teachers don’t know the difference between

«topic-comment» structure and «topicalization.» (They are not the same

thing.)

Let’s

briefly discuss «topic-comment» sentence structure and topicalization.

What

is Your Topic?

A topic

is what you are talking about. You can use either a subject or object as the

«topic» in a sentence.

A. If you use

the subject as your topic, then you are using an active voice.

BOY THROW BALL. The boy threw the ball.

B. If you

use the object as your topic, then you are using a passive voice.

BALL, BOY THROW. The ball was thrown by the boy.

Note

that the active voice is in Subject-Verb-Object word order: BOY THROW

BALL. The passive voice is in Object, Subject-Verb word order: BALL BOY

THROW.

What

is Topic-Comment Format?

Both of

the aforementioned sentences are in Topic-Comment format. As we’ve already

established, the topic is what you are talking about and the comment makes

observations about that topic. Topic is for the first item mentioned in a

sentence (whether it is the subject or object) and the comment is the

latter, and it makes a comment about the topic. So let’s take a look

at those sentences again:

A. Active

Voice, using the subject as your topic.

BOY THROW BALL.

Topic: BOY

Comment:

THROW BALL

What is the topic? Boy

What

is the comment saying about the boy? He threw the ball.

B. Passive

Voice, using the object as your topic.

BALL, BOY THROW.

Topic: BALL

Comment:

BOY THROW

What is the topic? Ball

What is the comment saying about the

ball? It was thrown by the boy.

So, as

you can see, the topic can be either a subject or an object. Now

that we’ve established the topic can be a «BOY» or it can be the «BALL» he

is throwing, and it can either be the subject or object of the sentence.

A. The BOY

can be:

�

The subject of the sentence:

BOY THROW BALL.

�

The object of the sentence: BALL,

HIT BOY.

B. The BALL

can be:

�

The subject of the sentence:

BALL, HIT BOY.

�

The object of the sentence: BOY

THROW BALL.

In each of these examples, the comment

is either THROW BALL» or HIT BOY.

A

Topic-Comment sentence structure can use either a Subject-Verb-Object or an

Object-Subject-Verb word order.

SVO is perfectly acceptable in ASL (regardless of what your ASL 1 teacher

may tell you).

Sign Order:

Imagine

two people are sitting somewhat near each other at a bar. For this

story we will suppose one is a man and one is a woman. The man decides that

the woman is really cool and he’d like to ask her on a date. But first he

leans over and asks, «You married?»

To his

relief she replies, «No, I’m not.»

She

then leans toward him and asks, «Are you married?»

To her

relief he replies, «No.»

They

start dating, get married, and have a wonderful life. End of story.

Did you

see what happened there? Let’s take a look at those English sentences

again. He didn’t use the word «are» in his sentence, but she did:

He leans over and asks, «You

married?»

(The tone of his voice rising toward the end of the sentence to indicate

it is a question.)

�..

She then leans toward him and asks,

«Are you married?»

(She stresses the word «you» in her sentence and raises her tone at the

end of the sentence.)He

didn’t use the words «I’m not» in his sentence but she did:

To his relief she replies, «No, I’m

not.»

��

To her relief he replies, «No.»

She

probably used «are» in «Are you married?» so that she could emphasize the word «you.»

Why did she do that? It is likely she wanted to make it clear that she

expected equal exchange of information and no «funny business.»

All

human languages possess a variety of right ways to say things. The

same is true of ASL. There are a variety of «right ways» to

structure your sentences in ASL. You

can use more or fewer signs and rearrange them depending on the context of

your sentence and what you want to emphasize. To ask the equivalent of «Are

you married?» you can sign in any of the formats:

YOU MARRIED?

MARRIED YOU?

YOU MARRIED YOU?

Topicalization

Now

let’s talk more about the

Object, Subject, Verb (OSV) order. As a general rule, when we use that particular

signing order, we tend to use topicalization.

Topicalization is a different

concept from «TOPIC / COMMENT.»

Topicalization is a sub-category of topic/comment. Topicalization

provides a way to use an object as your topic. (In English that is

referred to as using passive structure.)

Topicalization is the process of using a particular signing order (syntax) and

specific facial expressions (plus head positioning) to introduce the object of your sentence and turn it into your

topic. For example, if instead of signing «BOY THROW BALL» suppose I signed BALL, BOY THROW. I’d raise my eyebrows when I signed

the word BALL, and then I’d relax my eyebrows and sign the comment «BOY

THROW» (with a slight nod of the head).

So, really this is what is happening:

Normal

sentence: The boy threw the ball.

Topicalized: Do you recall that ball we discussed recently? The

boy threw it! (This is assuming that the boy has been identified

earlier in the conversation).

Normal sentence: BOY THROW BALL

Topicalized: BALL? BOY THROW!

At this

point in the discussion you might be wondering: «When should I use passive

voice instead of active voice?» (BALL, BOY THROW instead of BOY THROW BALL).

Another

way to ask that same question is, «When should you use topicalization?»

Specifically, «When should you sign the object at

the beginning of your sentence while raising your eyebrows?»

There

are several situations when you should topicalize. A few examples applying

to ASL are:

A. When the subject is unknown: MY WALLET? GONE!

I don’t

know why it is missing, if it was stolen, or who stole it.

To sign

this with active voice I would sign something to the effect of, «SOMEONE

STOLE MY WALLET» — which requires more signing.

B. Irrelevancy: MY CAR? SOLD!

It

doesn’t really matter who sold it. Just that the process is over. So why

should I waste time explaining who sold it?

C. Efficiency and/or Expediency: MY CELL PHONE? FOUND!

If I

explained to you last week that was at the county fair and lost my text

messaging device I don’t want to have to explain it to you again if you

still remember what had happened. So I sign «CELLPHONE» with my eyebrows up

and if you nod in recognition, I go ahead and tell you that it was found.

D. Clarification: MY SISTER SON? HE GRADUATE.

Perhaps you know that I have more than one nephew. If I signed «MY NEPHEW

GRADUATE» you still don’t know for sure «who» graduated. It is more

effective to clarify that it was my sister’s son that graduated and not my

brother’s son.

Some

instructors overemphasize topicalization or give the impression that the

majority of ASL communication is topicalized. The fact is many ASL sentences

are simply «Subject, Verb-(transitive), Object» example: «INDEX BOY THROW

BALL» («The boy threw the ball.») or are Subject-Verb (intransitive), for

example: «HE LEFT.»

So,

let’s review that again. Topicalization means that you are using the object

of the sentence as the topic and introducing it using a «yes/no question

expression» (raised eye brows and head slightly tilted forward) followed by a

comment.

A

sentence using Topic-Comment sentence structure can either topicalized or non-topicalized:

A.

Topicalized

1. YOUR MOM?

I MET YESTERDAY!

Your mom is the topic and the sentence is in Object-Verb-Subject word

order

2. MY CAT?

DIED!

My cat is the topic and the sentence is in Object-Verb word order. The

word, MY, is an attributive adjective.

B. Non-topicalized

1. I MET

YOUR MOM YESTERDAY!

I am the topic and the sentence is in Subject-Verb-Object word order.

2. MY CAT

DIED! [Note there is no comma or question mark after «CAT.»]

My cat is the topic and the sentence is in Subject-Verb word order. The

word, MY, is an attributive adjective.

If the following question were to appear on an exam, which answer should you

select?

Which of the following sentences uses topicalization?

A.

Subject-Verb-Object: BOY THROW BALL.

B.

Subject-Verb: BOY RUN.

C.

Subject-Noun: HE HOME.

D.

Subject-Adjective: HE TALL .

E. Object,

Subject-Verb: MONEY? she-GIVE-me.

The right answer is: MONEY?

she-GIVE-me.

Please

keep in mind that you don’t have to use topicalization.

Topicalization is not the norm

in extended Deaf conversations and is reserved for specific purposes such

as emphasis, expediency, clarification, or efficiency.

Additional notes:

The term «grammar» is typically used to refer to «the

proper use of language.» More specifically «a grammar» is a set

of rules for using a language. These rules guide users in

the correct speaking or signing of a language.

Who decides what is correct and incorrect grammar?

The

grammar (set of rules for proper use) of a language is developed by the group of people who use the

language. New grammar rules come into existence when enough members of the

group have spoken (signed) their language a particular way often

enough and long enough that it would seem odd to speak the language in some

other way.

If you don’t want to seem odd to others in your group, you’ve got to speak (sign)

a language according to the rules which have been developed by the community

which uses the language.

American Sign Language is tied to the Deaf

Community. We use our language in a certain way. That

«certain way» is what constitutes ASL grammar.

American Sign Language has its own grammar system,

separate from that of English.

What this means is ASL grammar has its own rules for phonology, morphology,

syntax, and pragmatics.

In general, ASL sentences follow a «TOPIC» «COMMENT» arrangement.

Another name for a «comment» is the term «predicate.» A

predicate is simply a word or phrase that says something about a topic. In

general, the subject of a sentence is your topic. The predicate is your

comment.

When discussing past and future events we tend to establish a time-frame before the rest of the sentence.

That gives us a «TIME» «TOPIC» «COMMENT» structure.

For example:

or «WEEK-PAST Pro1 WASH MY CAR »

[The «Pro1» term means to use a first-person pronoun. A first-person

pronoun means «I or me.» So «Pro1» is just a fancy way of saying «I» or

«me.» In the above example you would simply point at yourself to

mean «Pro1.»]

Quite often ASL signers will use the object of their sentence as

the topic. For example:

«MY CAR, WEEK-PAST I WASH»

[Note: The eyebrows are raised and the head is tilted slightly forward

during the «MY CAR» portion of that sentence.]

Using the object of your sentence as the topic of the sentence is called

«topicalization.» In this example, «my car» becomes the subject

instead of «me.» The fact that «I washed it last week» becomes the comment.

There is more than one sign for

«WASH.» Washing

a car or a window is different from the generic sign for «WASH»

to wash-in-a-machine, or to

wash

a dish. The real issue here isn’t so much the order of the words as it

is choosing appropriate ASL sign to accurately represent the concept.

There are a number of «correct» variations of

word order in American Sign Language (Humphries & Padden, 1992).

For example you could say: «I STUDENT I» or, «I STUDENT» or even,

«STUDENT I.»

Note: The concept of «I» in these sentences is done by pointing an index

finger at your chest and/or touching the tip of the index finger to your

chest.

You could sign:

«I FROM U-T-A-H I.»

«I FROM U-T-A-H.»

«FROM U-T-A-H I.»

All of the above

statements are «ASL.»

I notice that some «ASL» teachers tend to become fanatical about encouraging

their students to get as far away from English word order as possible and

thus focus on the version «FROM U-T-A-H I.»

It has been my experience during my various travels across

the U.S. that the versions «I STUDENT» and «I FROM U-T-A-H» work great and

are less confusing to the majority of people.

The version «FROM UTAH I» tends to be used

only after the

subject of the conversation has been introduced. For example, suppose

two people are talking about a man named Bob. If one of them says he

«thought Bob was from California» and I happen to know he is really from

Utah, I would sign «FROM UTAH HE» while nodding.

Think for a moment about how English uses the phrases:

«Do you…____?»

«Did you…_____?»

«Are you…_____?»

For example, «Are you going?»

A «hearing» English speaker might also say to

his/her friend in regard to a party which has recently been brought up as a

conversation topic: «You going?»

Woah! Think about that for a moment. Have you ever asked an English teacher

what is wrong with English since English sometimes uses the

word «are» and doesn’t the word «are» at other times?

In ASL «You going?» — tends to be expressed as «YOU GO?»

In ASL «Are you going?» — tends to be expressed as, «YOU GO YOU?»

Think of the second «YOU» as being «are you?» For example: «YOU GO

(are)-YOU?»

So, the second «YOU» actually means «are.» Heh.

ASL doesn’t use «state of being» verbs.

The English sentence «I am a

teacher» could be signed: «TEACHER ME » [while nodding your

head] or even «ME TEACHER»

[while nodding your head]. Both are correct, my suggestion is to choose the second version.

You might even see: PRO-1 TEACHER PRO-1 (which can also be written as I/ME

TEACHER I/ME since PRO-1 means first person pronoun). Or think of it

as meaning «I TEACHER AM» with the concept of «am» just happening to be

expressed via nodding while pointing at yourself.

If you are striving to pass an «ASL

test» like the American Sign Language Teachers Association certification test

(ASLTA), or the Sign Communication Proficiency Interview (SCPI), sure, go

ahead and use a version such as «TEACHER ME» —not because it is any more ASL but because it

«looks» less like English. Test evaluators are only human.

[And remember to use appropriate facial expressions!]

Dr. Vicars: Let’s discuss indexing, personal

pronouns, and directionality.

First off, indexing: It is when you point your index at a person who is or

isn’t in the signing area. Sometimes we call that present referent or absent referent.

If the person is there, you can just point at him to mean «HE»

If the person is not there, if you have identified him by spelling his name

or some other method of identification, (like a «name sign»), then you can «index»

him to a point in space. Once you have set up a referent, you can refer back to that same point each time you want to

talk about that person.

Need clarification on that ?

Students: [a lot of «no» answers]

[Topic: «Personal Pronouns»]

Dr. Vicars: Now lets talk about personal pronouns.

The simplest way is to just point. If I am talking to you and want to say

«YOU» then I point. To pluralize a personal pronoun, you sweep it. For example the concept of «THEY.» I

would point slightly off to the right and sweep it more to the right. For «YOU ALL» I would

point slightly to the left and sweep to slightly to the right, (crossing my sight line).

Of course if the people are present then you can simply point to them. The

more people there are the bigger the sweep. Any questions about personal pronouns?

Art: Does the sweep dip?

Dr. Vicars: It stays on a horizontal plane most of the time. If I am talking about a

group that is

organized vertically then I will sign (sweep) from top to bottom in an vertical motion.

But that is

rare.

Dr. Vicars: Okay now let’s see how this all ties into the principle of

«directionality.»

Suppose I index BOB on my right and FRED on my left. Then I sign «GIVE-TO»

from near my body to the place where I indexed Bob. That means «I give

(gave) (something) to Bob.»

If I sign GIVE TO starting the movement from the place off to the right and move it to

the left it means Bob gave to Fred. If I sign starting from off to the left and bring the sign GIVE TO toward my body what

would it mean?

Sandy: «Fred give to me?»

Dr. Vicars: Right.

Sandy: How do you establish tense at that point?

Dr. Vicars: Tense would be established before signing the rest of the sentence. I would

say, «YESTERDAY ME-GIVE-TO B-0-B» The fingerspelling of BOB would be immediately

after the ME-GIVE-TO and I would spell B-O-B slightly more to the right than normal. That way I

wouldn’t need to point to Bob. However there are three or four other acceptable ways to

sign the above sentence. You could establish Bob then indicate that yesterday you gave it to

him, etc.

Lii: Can tense be done at end of sentence, or is that confusing?

Dr. Vicars: That is confusing—I don’t recommend it. I can however give you an example of

«appropriately» using a time sign at the end of a sentence. Suppose I’m talking

with a friend about a problem that occurred yesterday and I sign: TRY FIND-OUT WHAT-HAPPEN

YESTERDAY

Dr. Vicars: That sentence talks about a situation that happened before now, but the

current conversation is happening now. Some people might try to put the sign «YESTERDAY»

at the beginning of that sentence, but I wouldn’t—it feels awkward.

Dr. Vicars: You can directionalize many different verbs. Hand-to is

probably the best example, but

«MEET» is also common. [To sign MEET, you hold both index fingers out in front

of you about a foot apart, pointed up, palms facing each other. Then you bring them together—it looks

like two people meeting. Note: The index fingers do not touch, just the lower parts of the hands.]

For example ME-MEET-YOU can be done in one motion. I don’t need to sign «I»

«MEET» «YOU» as three separate words. But rather I hold my right Index finger near me,

palm facing you, and my left index finger near you, palm facing me. Then I bring my right to my left.

One motion is all it took.

Monica: How do we know which verbs to use?

Dr. Vicars: That is the challenging part. Some just aren’t directional in nature. For example:

«WANT.» You have to sign it normal and indicate who wants what.

Dr. Vicars: But if you are in doubt about whether or not to use indexing or

directionality, go ahead and index it works every time even though it takes more effort.

(If you are taking an «in-person» class and prepping for an ASL

test, it is in your best interest to become familiar with which of your

vocabulary words can be directionalized or else you might lose points for

not demonstrating proper ASL grammar.)

Monica:

Art: Could you give examples for sweep, chop, and inward sweep diagrams used in [the

«Basic Sign Communication» book] please.

[Note, I used to use BSC as a of the text in one of my classes. I’ve used many

other texts as well. They all have their good points.]

Dr. Vicars: Sure. The sweep would be to pluralize a sign like THEY.

Dr. Vicars: The chop I’m not sure what you’re referring to is it …

[Clarification was made. The diagram in question is in the Basic Sign Communication

text, ISBN 0-913072-56-7, Level1, module 4, page 17]

Art: Yes, the center at the bottom

Dr. Vicars: Hold…okay…got it. You are talking about the three diagrams below the

slightly larger one is that right?

Art: Yes

Dr. Vicars: Good…we’re making progress… If I were handing a paper to a number of

individuals, I would use several short ME-GIVE-TO-YOU motions strung

together in a left to right sweeping motion.

If I were talking about passing a piece of paper to the class in general I would use

a sweeping motion from left to right. If I were giving the paper to just two

people, I’d use two ME-GIVE-TO-YOU motions one slightly to the left, then

one slightly to the right.

Art: Thanks

[…various discussion…]

Lii: How does one go about using «ing, s, and ed endings?» Does it need to be done?

Dr. Vicars: Good question Lii. Can I answer that next week during the grammar discussion?

Lii: You bet.

Dr. Vicars: Thanks Lii

Sandy: Similar question — how do we use punctuation? Just pause — other than emphasis

with face?

Dr. Vicars: Again a good question. Okay then, let me go ahead and answer both questions

now, then we’ll hear comments from those of you who have them.

Dr. Vicars: When you ask about «s,» you are asking about pluralization.

In ASL you can pluralize any particular

concept in a number of ways. So far in our lessons we have been using a sweeping motion, (for

example we turn the sign

«HE» into the word «THEY» by adding a sweeping movement).

The suffix «ed» is established by using a «tense

marker» like the sign PAST or is understood by context. For example if I know you are talking about a trip you went on last week, You

don’t need to keep signing «PAST,» I would understand it was past tense. You could

sign «TRUE GOOD» and I would know you meant «The trip went really well.»

If I sign, «YESTERDAY ME WALK SCHOOL,» the word «walk»

would be understood as «walked.»

About punctuation, you are right, you punctuate a sentence via your pauses and

facial expressions. One common type of punctuation is that of adding a

question mark at the end of a question by drawing a question mark in the air

or by holding the index finger in front of you in an «x» shape

then straightening and bending it a few times. This is called a

«Question Mark Wiggle.» Most of the time people don’t use Question

Mark Wiggle at the end of a question. Instead they rely on facial

expression to indicate that a question has been asked.

Suffixes such as «ing,» «ed,» and others are not used in ASL in the

sense that they are not separate signs that are added to a word. If I want to change

«learn» into

«learning» I simply sign it twice to show it is a process. Many times the

«ing» is implied. For example, «YESTERDAY I RUN» could be interpreted as «Yesterday I went for a

run,» or you could interpret it as, «Yesterday I was running.» How you interpret it would

depend on the rest of the message (context). …more >

Grammar 2 |

3

Inflection

Notes:

What equals «correct grammar» is

determined by a type of group consensus. Consensus occurs when an

opinion or decision is reached by a group as a whole. Political or

governmental bodies try to «come to a consensus» on issues. For

example, I was a student senator for a while. Occasionally as a

group we would «come to a consensus» on some topic. Coming

to a consensus didn’t mean that everyone agreed with every aspect of the

decision, but we were willing to go along with the group and support the

decision.

That is how it is in ASL. The older folks don’t always

agree with signs used by the younger folks. Those who teach ASL classes

often don’t agree with the general use of certain signs that they consider

to be «signed English.» But it isn’t «one person’s or one instructor’s

opinion» that determines what constitutes ASL — it is the group.

Note: In this discussion the phrase «speaking a

language» is not limited to «voicing» but rather it also

includes signing or producing a language.

References:

Humphries, T., & Padden, C. (1992). Learning American sign

language. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall.