«Say, you, the lady over there.» «Eh?» «Could you give me a bit of advice?»

«Probably just a stupid urban legend» «But they do say ‘there’s no smoke without fire’, don’t they?»

«I don’t think she’s an opponent you can ignore like that …» «That’s right, they say a cornered rat bites back, don’t they?»

«I’ve heard about it, Koichi» «You don’t need to say anything more, I know. It’s the summer festival incident at the shrine, right?»

«Say, shall we try a questionnaire with the boarding students?» «Ah! One of those things they call ‘marketing research’.»

«It is when you overcome that, that a boy becomes something-something» «If you’re trying to say something important sounding keep talking right to the end!»

«I have to pee.» «Jonny, that’s not the right thing to say. Say, ‘Excuse me. I need to go to the toilet.'»

«Now I must say good-bye,» he said suddenly.

«Don’t say such rubbish!» said the farmer.

saysay1 S1 W1 J1 /seɪ/ [動] (says /sez/, said /sed/)

1 THOUGHT/OPINION考え・意見など a) 《他》 …を[と]言う• “I don’t care, ” he said. 「どうでもいいよ」と彼は言った.• He doesn’t say very much. 彼はあまり口数が多くない.• What are you trying to say? 何を言おうとしているのですか. say (that) …ということを言う• She said that you were looking for me. あなたが私を探していると彼女が言ってたけど. say something / anything 何か言う• He said something in Japanese. 彼は日本語で何か言った.• Did she say anything else about the trip? 彼女は旅行についてほかに何か言っていましたか. say nothing 何も言わない• She looked at him but said nothing. 彼を見ても彼女は何も言わなかった. say something to somebody <人>に<…>と言う• What did you say to them? 彼らに何と言ったのですか. say how / why / who etc. どのくらい…か[なぜ…か,だれが…か]を言う• Don’t be afraid of saying what you think. 自分の考えを恐れずに言いなさい. something / nothing to say 何らかの言うべきこと[何一つ言うことがないこと]• I couldn’t think of anything to say to her. 彼女に言うべきことは何一つ思いつかなかった. a terrible / stupid / nice etc. thing to say 言うにはひどい[ばかげた,すてきな]こと, ひどい[ばかげた,すてきな]発言• It’s a terrible thing to say, but I wish he were dead. こんなことを言ってはいけないが,あいつが死んだらいいのに. say no (to something)refuse someone’s request or offer (<要求・申し出など>に対して)だめだと言う, (<要求・申し出など>を)断る• I’ll ask Mom if I can come, but I think she’ll say no. 行っていいかママに聞いてみるけど,だめだって言うだろうな. say yes (to something)agree to someone’s request or offer (<要求・申し出など>に対して)いいと言う, (<要求・申し出など>に)同意する, (<要求・申し出など>を)承諾する• Can I go, Dad? Please say yes! パパ,行ってもいい? お願いだからいいって言って. say hello / goodbye / thank yousay something to greet someone, thank them etc. こんにちは[さよなら,ありがとう]を言う, あいさつをする[別れの言葉を言う,礼を言う]• She left without saying goodbye. 彼女はさよならも言わずに出て行った.• He went upstairs to say good night to the children. 彼は子供たちにおやすみを言いに2階へ上がった. say (you’re) sorryapologize 謝る• I already said I’m sorry. もう謝ったよ. be right in saying (that) …と言うのは正しい, 言っても間違いでない• I think I’m right in saying that the painting cost around $50,000. その絵は5万ドルくらいしたと言っても間違いでないと思う. not say a wordbe completely silent 一言も言わない• He didn’t say a word after saying “hello.” 彼は「こんにちは」と言ったきり,一言もしゃべらなかった. say a few wordsmake a short speech 簡単なあいさつをする• I’d just like to say a few words to thank everyone for their help. みなさんのご支援に対して簡単にお礼を申し上げたく思います. b) 《自》 言う• “Is John coming?” “I don’t know, he didn’t say.” 「ジョンは来るの?」「知らない,何も言ってなかったから」 I’d rather not say 言いたくない• “So what are your plans now?” “I’d rather not say at the moment.” 「じゃ,これからどうするの?」「今は言いたくないんだ」 say soused to refer to a fact that you have already mentioned or are about to mention そう言う, <前後に言及することを> 口に出す• Although he didn’t say so, it was obvious he was in a lot of pain. 彼は口には出さなかったが,痛みがひどいのは明らかだった. ►1When talking about giving somebody facts or information about something, don’t use ‘say’, use tell.(1) 相手に「(事実・情報を)伝える・知らせる」の意味で say は不可. tell を用いる• Today I want to tell (×say) you about my family. 今日は私の家族についてお話したいと思います.To describe the subject of a discussion in a newspaper or on television or radio, don’t say that it ‘says about something’, say that it talks about or discusses something.(2) 新聞・テレビ・ラジオなどの話題を取り上げる場合, say about は不可. talk about または discuss を用いる• The article talked (×said) about the problem of pollution. その記事は汚染問題を論じていた.

2 GIVE INFORMATION情報をもたらす 《他受け身形不可》 <看板・手紙・記事などに> …と書いてある, 出ている, 載っている• What does the letter say? 手紙に何て書いてあるの?• The sign said “Back in 10 minutes.” 張り紙には「10分で戻ります」と書いてあった.• What do the instructions say? 説明書には何と書いてあるの. say (that) …ということが書いてある• The report says that safety standards need to be improved. 安全基準を改善する必要があると報告書は述べている. say to do something <…>するようにと書いてある• The label says to take one pill before meals. ラベルには食前に1錠飲むようにと書いてある. say who / what / how etc.usually in questions and negatives だれが…か[何が…か,どのように…か]が書いてある• The card doesn’t say who sent the flowers. カードには花束の贈り主が書いてない. it says here (that)used to tell someone some information that you are reading (読みながら) …とここに出ています• It says here the restaurant has live music. そのレストランでは音楽の生演奏があるとここに書いてあります. 3 CLOCK/WATCH時計 《他受け身形不可》 <時計が> <ある時刻> を指す• The kitchen clock said 9 o’clock. 台所の時計は9時を指していた.• The clock in the hall said it was almost midnight. 廊下の時計ではそろそろ12時だった.

4 WHAT somebody MEANS人が意味するところ 《他通例進行形で》 be saying (that) …と言いたい, 主張する• What I’m saying is that it might be better to wait a while. しばらく待ったほうがいいんじゃないかって言いたいんだよ. all I’m saying is (that)said in order to calm someone down who has become annoyed or worried by what you have said previously 言いたいのは…ということだけだ• All I’m saying is that we shouldn’t rush into anything. 言いたいのは何事も慌てて行動してはならないということだけだ. 5 COMMON OPINION一般的な意見 《他》 <人によれば> …ということである• Experts say that the painting is by a German artist. 専門家によればその絵はドイツの画家の作ということだ. they / people say (that)often spoken …ということだそうだ• They say it’s a good place for surfing. そこはサーフィンをするには格好の場所なんだって.• People say you don’t get any sleep once you have a baby. 赤ん坊が生まれたら全然眠れなくなるそうだ. it is said (that)often written or in formal language …ということである, …といわれている• It is said that she lived to be 120. 彼女は120歳まで生きたということだ. be said to be something / do something <…>である[<…>する]といわれている• She’s said to be the richest woman in the world. 彼女は世界一の金持ちだそうだ. you know what they sayused before saying a well-known phrase or saying, or something that a lot of people think is true (世間で)よく言うでしょ, ことわざにもあるじゃない as they sayused when saying a word or phrase that many people use (世間で)よく言われるように, ことわざにあるように• One day, I will settle down, as they say, and raise a family. よく言われているように,私もいつかは身を固めて家族を持つつもりだ.

6 SHOW CHARACTER/QUALITIES特徴・性質を示す 《他》 <特徴・性質など> を明らかにする, 示す• an experience that says something about human nature 人間性について何かを明らかにする経験 something says a lot about somebody / somethingshows something very clearly <…>が<…>をよく示す, <…>によって<…>がよくわかる• What you wear says a lot about what type of person you are. 服装を見ればどんな人物かがよくわかる.• Her actions in a time of stress say a lot about what kind of mother she is. ストレスがかかっている時の行動で彼女がどんな母親かがよくわかる. it says a lot for somebody (that)it shows that someone has very good qualities …とは<人>はりっぱであることを示す something doesn’t say much for something / somebodysomething shows that something or someone is not very good <…>は<…>があまりよくないことを示す• The test scores don’t say much for the quality of teaching. テストの点は教え方があまりよくないことを示している. 7 SHOW somebody’S FEELINGS人の感情を示す 《他》 <表情などが> …と語る• The look on her face said “I love you.” 彼女の表情が「愛してる」と語っていた. somebody’s face / look / expression says it all (says everything とも)The expression on someone’s face shows you everything that a person is feeling without the need for words <人>の表情が(心の内の)すべてを語っている, 表情から<人>の心がすべてわかる• She didn’t have to say anything; her smile said it all. 笑顔がすべてを語っていたので,彼女は何も言う必要はなかった. 8 SUPPOSE something仮定する 《他通例命令形で》 仮に…としたら, 仮に…としよう• Say you lost your job, what would you do then? 失業したとしたら,そのときはどうする? let’s (just) say (that) 仮に…としよう, 仮に…としたら• Let’s say you won $3 million. How would you spend it? 仮に300万ドル当たったとしましょう.どう使いますか. suppose

9 GIVE AN EXAMPLE実例を示す 《他通例命令形で》 (例を挙げて) 例えば…, …くらい• If we put out, say, 20 chairs, do you think that would be enough? いすは20脚くらい出せば十分だと思いますか. let’s say 例えば…, …くらい 10 TELL somebody TO DO something指示する 《他》 〘話〙 say to do something <…>するように言う• She said to give her a call when we get to the hotel. 彼女からホテルに着いたら電話するように言われた. 11 PRONOUNCE発音 《他》 <語・名前など> を発音する, 読む how do you say …?used to ask someone to pronounce something for you …はどう発音しますか[何と言いますか] 12 SPEAK THE WORDS OF something書かれた言葉を話す 《他》 <せりふ・詩など> を言う, 暗唱する say a prayer 祈りをささげる say your line(s)if an actor says his/her lines, they say the words of their character in the script for a play, movie, live show etc. せりふを言う 13 HAVE MEANING意味をもつ 《他》 say something to somebody (音楽・絵画などが) <人>に<…>を訴える• Most modern art doesn’t say much to me. 現代美術のほとんどは私に訴えるものがない.

類語say は「…を(と)言う」の意味で,人の言ったこと, that 節, something, anything, nothing, so, hello, goodbye などを伴うことが多い.「<人>に<…>と言う」は say something to somebody を用いる• Has he said something to you? 彼はあなたに何か言ったの?tell は「<人>に話す,言う」「<情報・事実など>を教える」などを意味する.「<人>に<情報など>を与える」は tell somebody something を用いる• Can anyone tell me what time it is? だれか時間を教えてくれる?talk と speak はともに「話す」を意味し,ほとんどの場合で入れ替え可能だが, talk は会話やインフォーマルな場面で用いられることが多い• All afternoon, they sat and talked about their trip. 午後中彼らは座って旅行の話をしていた.speak は知識・言語または身体的に「話す」能力などについても用いられる• Do you speak English? 英語を話せますか?成句 → anything / whatever you say → as I say / said → can’t say fairer than that → have a lot to say for yourself → have something to say (about something) → having said that → I can’t say (that) → I couldn’t say → if I do say so myself → if I may say so → I have to say → I’ll say → I’ll say this / that (much) for somebody → I say → It’s not for somebody to say → I wouldn’t say no (to something) → I would say → let’s just say → not have much to say for yourself → not to say → say no more → (just) say the word → something says it all → says who? → say something to somebody’s face → say something to yourself → say what? → say what you like → say when → say your piece → shall we say → something / a lot / not much to be said for something → that is not to say → that is to say → that said → that’s not saying much → there’s no saying when / who / what etc. → though I say it myself → to say nothing of something → to say the least → what do you have to say for yourself? → what do you say? → what / whatever somebody says, goes → who can say? → who says? → wouldn’t you say? → you can say that again → you could say that → you don’t say! → you said it! → wouldn’t say boo to a goose → easier said than doneeasy25 → enough said → say a mouthful4 → needless to say → no sooner said than donesoon → well said → when all’s said and done

saysay2 S2 W3 [名] 《U, a/the ~》

1 発言権, 決定権 have a say / have some say 発言権がある, 決定権を持っている• Local people want to have a say in decisions that affect them. 地元住民は自分たちにかかわる決定には発言したいと思っている. have no say 決定にかかわれない, 発言権がない• countries where women have no say over their choice of husband 自らの夫選びに女性が発言権を持たない国々 have the final sayhas the right to make the final decision about something 最終決定権を持っている 2 have / get your say 意見を言う(機会がある), 発言の機会を持つ• You’ve had your say – now it’s my turn. あなたはもう意見を言ったんだから,今度は私の番だ.

saysay3 S2 [間] 米 〘インフォーマル〙

1 (相手の気をひいて) ねえ, ちょっと• Say, Mike, how about a beer after work? ねえ,マイク,仕事のあとにビールでも飲まない? 2 〘やや古〙 (びっくりしたことを相手に言う前に) あれ, まあ

By

Last updated:

March 16, 2023

With these 250 essential Japanese words and phrases, you’ll be prepared for any situation.

The Japanese language might take years to master, but what if you need to get through a conversation right now? Start by learning these everyday conversational words and crucial survival phrases. The rest will follow.

And you can just click on a word or phrase to hear its pronunciation.

Contents

- Greetings and Starters

- Basic Conversation

- Saying Yes and No

- Saying “I Don’t Understand”

- Please, Thank You and Apologies

- Saying Goodbye

- Travel Vocabulary

- Basic Question Words

- Japanese Pronouns

- Phrases for Dining

- Phrases for Social Gatherings

- Phrases for Home

- Shopping in Japanese

- Phrases for Casual Conversations

- Japanese Slang

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Greetings and Starters

ohayou gozaimasu: おはようございます — Good morning

The casual version is ohayou (おはよう ). In a workplace, someone greeting a colleague for the first time that day might use this phrase even if the clock reads 7 p.m.

konnichiwa: こんにちは — Hello / good afternoon

Konnichiwa can be used any time of day as a general greeting, but it’s most commonly used between 11 a.m. and 5 p.m.

hisashiburi: 久しぶり — It’s been a while

Basic Conversation

o namae wa nan desu ka?: お名前は何ですか? — What’s your name?

This is a polite way to ask someone for their name. The more informal version is O namae wa? (おなまえは? ) — Your name is…?

… desu: …です — I am … / It is …

It’s easiest to think of desu like the English word “to be.” Unlike “to be,” desu stays the same regardless of the subject.

For example:

- Tomu desu (トムです ) — I’m Tom

- Atsui desu (暑い です ) — It’s hot/I’m hot

- Osoi desu (おそいです ) — You’re late!

watashi wa … desu: 私は…です — I am …

This is a longer version of the previous phrase. You also use this to say your name:

Watashi wa Pouru desu.

私はポールです。

I am Paul.

But this sentence pattern can also be used for any adjectives. For example:

- samui (寒い ) — Cold

- ureshii (嬉しい ) — Happy

- nemui (眠い ) — Sleepy

watashi wa … karakimashita: 私は… から来ました — I’m from …

Simply use this to describe what country you’re from. Here’s a list of some countries in Japanese:

- Igirisu (イギリス ) — United Kingdom

- Amerika (アメリカ ) — United States of America

- Ousutoraria (オーストラリア ) — Australia

- Doitsu (ドイツ ) — Germany

- Chuugoku (中国 ) — China

- Kangoku (韓国 ) — Korea

Many others are almost identical in Japanese, such as:

- Kanada (カナダ ) — Canada

- Furansu (フランス ) — France

- Supein (スペイン ) — Spain

If you don’t know how to say your country’s name, say it in English—chances are, people will understand where you mean.

suki desu: 好きです — I like it

You can say what you like by adding … ga suki desu (が好きです ). For example:

Okashi ga suki desu.

お菓子が好きです。

I like sweets.

ii desu yo: いいですよ — It’s good

You’ll often also hear ii yo (いいよ ), especially from women/girls.

suki dewa arimasen: 好きではありません — I don’t like it

dame desu: ダメです — It’s no good

In more casual conversation, you can also say just dame (だめ ) or dame da (だめだ).

takusan: たくさん — A lot

Takusan is similar to ooi (多い ). The main difference is that takusan can function as a noun, adjective or adverb, while ooi is only an adjective. For example:

Kooen ni hana ga takusan arimasu.

公園に花がたくさんあります。

There are lots of flowers in the park.

sukoshi: 少し — A little

Here’s an example of it in use:

Koohii ni sato wo sukoshi onegaishimasu.

コーヒーにさとをすこしお願いします。

A little sugar in my coffee, please.

ima nanji desu ka?: 今何時ですか? — What time is it?

In casual situations, saying Ima nanji? (今何時 ) will work just fine.

… ji desu: …時です — It’s … o’clock

This plus a number is all you need to tell the time! For example:

Ichiji desu.

一時です。

It’s 1 o’clock.

nihongo de hanashimashou: 日本語で話しましょう — Let’s talk in Japanese

Saying Yes and No

hai: はい — Yes

Another way to say “yes” is with non-verbal cues like nodding your head up and down or giving a thumbs up.

soudesuka: そうですか — That is right

Saying this while nodding is a polite way to show that you’re paying attention when someone tells you something new. You can also use soka そっか, soudane そうだね or soune そうね for variety. These are less formal, but generally acceptable and certainly not rude.

sou desu: そうです — That’s right

You can also say hai, sou desu (はい ,そうです ) — Yes, that’s right. However, the hai is implied and you can leave it off.

sou: そう — That’s right (informal)

un: うん / aa: ああ / ee: ええ

The Japanese use aizuchi (相槌 ), which are simple words or gestures that all mean “yes,” to indicate you’re listening. They don’t have a strict “definition,” but are similar to saying “uh-huh” or “mm-hm” in English.

mochiron: もちろん — Of course

ii desu yo: いいですよ — Okay

This literally means “That’s good!” and as such can be used to show your approval of something.

iie: いいえ — no

This is the no-nonsense way to say “no.” However, Japanese culture prefers less direct approaches.

There are also several non-verbal ways to express “no.” Rubbing the back of the neck, making an “X” with both arms or even taking in a deep breath all mean “no.”

uun: ううん

This is a sound that indicated you don’t quite agree, similar to saying “Umm…” in English.

iya: いやー

Whether this interjection is being used to mean “no” depends on the context. If you suggest dinner and someone responds with iya…, then their response is a non-committal “Well, you see…”

dame: だめ — It’s no good / You can’t do that

This is a fairly assertive way to say no. It’s saying that something is pointless or shouldn’t be done. This is one to use when someone is doing something you don’t want them to do, or if you’re trying to accomplish something that seems like it won’t work.

chotto…: ちょっと… — A little…

If you use chotto, remember to trail off at the end, as you’re basically saying, “It’s a little…” For instance, if someone asks what you’re doing tomorrow afternoon with the aim to meet up, you can respond “Chotto…” to mean that tomorrow afternoon’s not an ideal time for you.

In business settings, two simple phrases to convey “no” without saying “no” are:

muzukashii desu: 難しいです — It’s difficult

kangaete okimasu: 考えておきます — I’ll think about it

While not outright saying “no,” they express a refusal to the listener without sounding impolite.

Saying “I Don’t Understand”

wakarimasen: 分かりません — I don’t understand

If you’re around friends, you can use the casual variant, wakaranai (わからない ).

mou ichido itte kudasai: もう一度言ってください — Please say that again

yukkuri onegai shimasu: ゆっくりお願いします — Slowly, please

kikoemasen deshita: 聞こえませんでした — I didn’t hear that

mou ichido itte kudasai: もう一度言ってください — Please say it again

Please, Thank You and Apologies

arigatou gozaimasu: ありがとうございます — Thank you

The friendlier, more casual way to say thanks is arigatou (ありがとう ). You’ll also see its abbreviation, ari (あり ), pretty often on Japanese message boards. A friend might just thank you with doumo (どうも ).

iroiro arigatou gozaimashita: 色々ありがとうございました — Thank you for everything

douitashimashite: どういたしまして — You’re welcome

Although this is technically the correct response to “Thank you,” it’s rarely used these days in casual Japanese conversation. The following phrase is much more common.

mondai nai desu: 問題ないです — No problem

kudasai: ください — Please (requesting)

The word kudasai is used when making requests, as in these examples:

Isoide kudasai.

急いでください。

Please hurry.

Koohii o kudasai?

コーヒーをください?

Can I please have a coffee?

douzo: どうぞ — Please (offering)

Using douzo is like saying, “Please go ahead.” You can use it when ushering someone through the door before you, or offering a coworker some delicious snacks, for example.

otsukaresama desu: お疲れ様です — Thank you for your efforts

This expression is often said as a parting sentiment when you, or someone else, finishes their work. You can think of it as saying, “That’s a wrap for the day.”

shitsurei shimasu: 失礼します — Excuse me (for my rudeness)

Another expression commonly heard in the office, shitsurei shimasu is used when you’re leaving a room. It’s similar to saying, “Sorry to have bothered you.” You can also end a formal or polite phone call with this phrase.

sumimasen: すみません — Excuse me, I’m sorry

Sumimasen is often used to say “Excuse me” (like if you need help getting directions ) and “Sorry” (like when you accidentally nudge someone). It can also be said as a “thank you” when you’ve troubled someone (Think: “Thanks for letting me put you out”).

gomen nasai: ごめんなさい — I’m sorry

In casual situations and among family members and friends, gomen nasai replaces sumimasen when saying sorry.

gomen: ごめん — I’m sorry

You can use this less formal expression among those who are close to you.

Saying Goodbye

jaa, mata!: じゃあ、また! / mata ne: またね — See you!

You can use dewa mata (ではまた ) for a slightly more formal expression. There’s also jaa ne (じゃあね ), and then jaa mata ashita ne (じゃまた明日ね ) — see you tomorrow.

o genki de: お元気で — Take care

If “see you” is a little too casual for you, then you can say o genki de instead. This literally means “be healthy” and can be used to say, “Good luck!”

meado o oshiete moraemasu ka?: メアドを教えてもらえますか? — Could I have your e-mail address?

If that’s a little too long to memorize, you can ask:

Meruado o oshiete?

メルアドを教えて?

Can I get your e-mail address? (Literally, “Teach me your email?”)

tegami kaku yo: 手紙書くよ — I’ll write you letters

tsuitara, denwa shimasu/meeru shimasu: 着いたら、電話します / メールします — I’ll call/email you when I arrive

mata sugu ni kimasu yo: またすぐに来ますよ — I’ll be back soon

asobi ni kite kudasai ne: 遊びに来てくださいね — Come visit me

watashi no ie dewa, itsumo anata o kangei shimasu yo!: わたしの家でわ, いつもあなたを感じますよ! — You’re always welcome in my home!

Travel Vocabulary

These handy phrases will give you what you need to get around Japan and, in case of an emergency, ask for help.

sumimasen, chikatetsu / eki wa doko desu ka: すみません、地下鉄 / 駅はどこですか? — Excuse me, where’s the subway/station?

kono densha wa … eki ni tomarimasu ka?: この電車は… 駅に止まりますか? — Does this train stop at … station?

kono basu wa … ni ikimasu ka?: このバスは…にいきますか? — Does this bus go to … ?

takushi nori ba wa dokodesu ka?: タクシーのりばはどこですか? — Where is the taxi platform?

… made tsureteitte kudasai: …まで連れて行ってください — Please take me to …

Use this phrase to tell the taxi driver where you want to go.

yoyaku wo shitainodesuga: 予約をしたいのですが — I’d like to make a reservation.

yoyaku shiteimasu: 予約しています — I have a reservation.

chekkuauto wa nanji desu ka?: チェックアウトは何時ですか? — What time is checkout?

michi ni mayotte shimaimashita: 道に迷ってしまいました — I’m lost.

tasukete!: たすけて! — Help! (for emergencies)

tetsudatte kuremasen ka?: てつだってくれませんか? — Can you help me? (for everyday situations)

keisatsu / kyuukyuusha wo yondekudasai: 警察 / 救急車を呼んでください — Please call the police / an ambulance.

Here’s a useful note: the emergency numbers in Japan are 119 for an ambulance and 110 for the police.

Basic Question Words

Knowing some of the essential Japanese question words will go a long way toward getting your questions across to Japanese speakers.

nani: 何 — What

Nani can be used alone or in a sentence. When placed before desu, the word nani drops its -i and becomes nan. For example:

Kore wa nan desu ka?

これは何ですか?

What is this?

doko: どこ — Where

Doko is used when asking for a location, like this:

Toire wa doko desu ka?

トイレはどこですか ?

Where is the toilet?

If you don’t know the word for the place you’re looking for, another helpful option is pointing to it on a map and asking:

Doko desu ka?

どこですか ?

Where is it?

dare: 誰 — Who

If you’re referring to a specific person, add it before dare:

Kanojo wa dare desu ka?

彼女は誰ですか?

Who is she?

itsu: いつ — When

doushite: どうして — Why

If you need to ask politely, say it as Doushite desu ka? (どうしてですか?). If you’re with friends or family, you can use the casual form nande (何で ) instead.

naze: なぜ — Why

This is pretty similar to doushite, but a bit more formal. Naze is also used to ask the reason behind something, while doushite has a nuance of “how” to it.

ikura: いくら — How much

ikutsu: いくつ — How many

This is a general word to ask “how much” or “how many” of a numerical amount. For example:

Okashi wa ikutsu hoshii desu ka?

おかしはいくつ星いですか?

How many snacks do you want?

It can also be used to ask someone’s age:

Oikutsu desu ka?

おいくつですか?

How old are you?

nan …: 何… — How many

Nan is a more specific way of asking how much of something there is. It works by combining nan with a counter, such as:

- nanbon (何本 ) — How many long cylindrical objects?

- nannin (何人 ) — How many people?

- nanmai (何枚 ) — How many sheets?

To learn more about how to talk about quantities, check out our post about Japanese counting and numbers.

dochira: どちら — Which one (out of two)?

dore: どれ — Which one (out of many)?

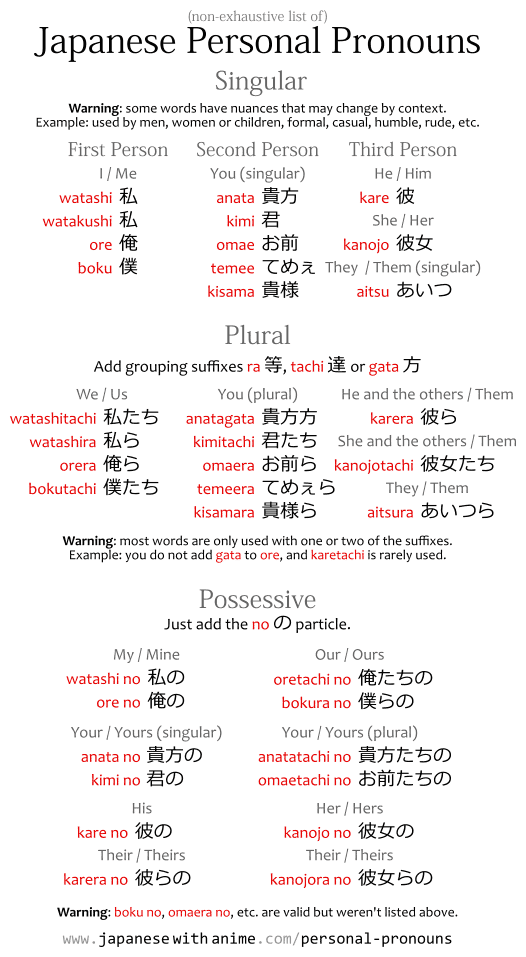

Japanese Pronouns

Japanese has a wide variety of pronouns you can use, helping you make your sentences more direct when you’re referring to yourself, your friend or your friend’s boyfriend.

watashi: 私 — I (all genders)

Watashi is the go-to in polite situations. It’s sometimes pronounced watakushi (私) for extra formality, and some female speakers may shorten it to atashi (私) in casual settings.

boku: 僕 — I (usually male)

Boku is mostly used by men and boys when they’re among friends. Nowadays, some girls use boku, as well, which gives off an air of tomboyish-ness.

ore: 俺 — I (male)

While boku is sometimes used by girls, ore is an exclusively male pronoun. It gives off a bit of a rough image, so it’s only used among close friends in casual situations.

jibun: 自分 — Myself / yourself / themselves

Jibun is used to refer to a sense of self. It can also take a variety of forms, like jibun no (自分の ) — one’s own (something), and jibun de (自分で ) — by yourself. It’s also a more polite way of referring to someone else.

anata: あなた — You

Anata translates to “you,” but it’s not used in the way it’s used in English. Most of the time, Japanese omits “you” altogether, favoring a person’s name instead. This form can be used as a term of endearment between couples.

kimi: 君 — You

Kimi is largely used to talk to someone of lower status than yourself, such as a boss talking to their employees. It’s also used to add some pizzazz to writing, such as in the hit movie “Kimi no na wa” (君のなわ ) — Your Name.

kare: 彼 — He / him

While the Japanese language does favor using a person’s name over second or third person pronouns, using kare is perfectly okay. Plus, kare can be used to refer to someone’s boyfriend.

kanojo: 彼女 — She / her

Same as kare, but for women. In the same way as kare, kanojo can also be used to refer to a girlfriend!

tachi: …たち — “… and company” (pluralizes pronouns)

To turn a pronoun into a plural, just add -tachi. For example:

- watashi tachi (私たち ) — We

- kimi tachi (君たち ) — You (plural)

- kanojo tachi (彼女たち ) — A group of women

- Sasuke tachi (サスケたち ) — Sasuke and his friends

kore: これ — This

Used to refer to something close to the speaker.

sore: それ — That

Used to refer to something close to the listener.

are: あれ — That (over there)

Used to refer to something far from both the speaker and the listener.

Phrases for Dining

Okay, now that we’ve gotten the formalities out of the way, it’s time to talk about what’s really important: food!

onaka ga suite imasu: お腹が空いてます — I’m hungry

This literally means your stomach has become empty. Some variations are:

- onaka ga suita (お腹が空いた ), informal

- onaka ga hetta (お腹が減った ), informal, often interchanged with onaka ga suita

- hara hetta (はらへった ), masculine

- onaka ga pekopeko (お腹がぺこぺこ ), onomatopoeia that means your stomach is growling

mada tabete imasen: まだ食べていません — I haven’t eaten yet

For a more casual version, go ahead and say mada tabeteinai (まだ食べていない ).

menyuu, onegai shimasu: メニュー、お願いします — Please bring me a menu

You can also opt for the more formal version:

Menyuu, onegai dekimasu ka?

メニュー、お願いできますか?

May I have the menu?

sore wa nan desu ka?: それは何ですか? — What’s that?

kore o tabete mitai desu: これを食べてみたいです — I’d like to try this

… o kudasai: …をください — I’d like …

State whatever you’d like to order, and follow it with … o kudasai. For example:

Koohii o kudasai.

コーヒーをください?

I’d like a coffee, please.

… ga arimasu ka?: …がありますか? — Do you have … ?

As a reply, you’ll simply hear arimasu ( あります).

… tsuki desu ka: …付きですか? — Does it come with … ?

If you want to know if certain foods are included with your order, use this to ask. For example:

Furaido poteto tsuki desu ka?

フライドポテト付きですか?

Does it come with fries?

… ga taberaremasen: …が食べられません — I can’t eat …

This is a good phrase to learn for vegetarians, vegans and other people with dietary restrictions. For example, niku (肉 ) is “meat” and sakana (魚 ) is “fish.” So if you’re on a strict veg diet, you can say:

Niku to sakana ga taberaremasen.

肉と魚が食べられません。

I can’t eat meat and fish.

… arerugii ga arimasu: …アレルギーがあります — I’m allergic to …

State whatever you’re allergic to and add this phrase to the end. Just to be safe rather than sorry, you can ask: … ga haitte imasu ka? (が入っています か?) which means, “Are / Is there any … in it?” For example:

Tamago ga haitte imasu ka?

卵が入っていますか?

Are there any eggs in it?

oishii desu!: おいしいです! — It’s delicious!

If you’re eyeballing a slice of cake, then oishisou (美味しそう ), meaning “It looks delicious,” could be useful. A casual and “manly” way to say something is delicious is umai (上手い ).

mazui desu: まずいです — It’s terrible

onaka ga ippai desu: お腹が一杯です — I’m full

okawari: おかわり — Another serving, please

hai, onegaishimasu: はい、お願いします — Yes, please (when offered food)

iie, kekkoudesu: いいえ、結構です — I’m fine, thank you (when offered food)

itadakimasu: いただきます — Let’s dig in

This is used before digging into your meal, similar to “Bon appétit.”

okanjou / okaikei, onegai shimasu: お勘定 / お会計、お願いします — Check, please

warikan ni shite kudasai: 割り勘にしてください — Split the check, please

betsubetsu de onegaishimasu: 別別でお願いします — We’ll pay separately, please

gochisousama deshita: ごちそうさまでした — Thanks for the meal

Like itadakimasu, this phrase is a fixture at every meal. You say this when the meal is finished.

Phrases for Social Gatherings

Show your friends and colleagues you know how to have fun with these phrases during social gatherings.

tabemashou: 食べましょう — Let’s eat

When planning a fun day out with friends, there are a few casual phrases to use when discussing plans. If you decide to have lunch, state tabemashou!

nomimashou: 飲みましょう — Let’s drink

You can also suggest grabbing a drink by using this phrase.

ikimashou: 行きましょう — Let’s go

Once your plans are decided, it’s time to head out by saying this phrase.

yatta!: やったー! — Yay!

kanpai!: 乾杯! — Cheers!

Once the party has begun, it’s essential to clink your glasses together and say kanpai! You say this phrase before drinking, not after.

ureshii desu: 嬉しいです — I’m happy

okawari o kudasai: お代わりをください — Refill, please

daijoubu desu: 大丈夫です — I’m fine – This is a polite way to respectfully say “no,” such as when you’re done drinking for the night.

Phrases for Home

tadaima: ただいま — I’m back

Everyone says this when they arrive home. If you go out, say this when you get back to let everyone know you’ve arrived home safely. If you want to, you can also say it when coming back from the bathroom; it tends to go down well.

okaeri nasai: おかえりなさい — Welcome back

This is said in response to tadaima. You can use this when someone else gets home, like when a parent returns from work or when a sibling gets back from cram school.

ofuro ni haitte mo ii desu ka?: お風呂に入ってもいいですか? — May I take a bath?

In Japan, most families take a bath every night, and if you’re staying somewhere like with a host family, you’ll be welcome to have one too if you ask.

If you’d prefer to take a shower (I did), you can just replace the word ofuru (お風呂 ) — bath with shawaa (シャワー ) — shower. Just make sure you don’t throw the bath water out when you’re done, as the family shares the hot water.

oyasumi nasai: おやすみなさい — Good night

You can also leave off the -nasai to make it less formal.

Shopping in Japanese

With the streets brimming with food stalls and vendors, the high-end boutiques lining Ginza and the ultra-cool and unique souvenir shops, there’s no way to avoid shopping while traveling through Japan.

irasshaimase: いらっしゃいませ — Welcome

You will hear a chorus of irasshaimase! when you enter a shop.

kore wa nan desu ka?: これは何ですか? — What is this?

kore wa nan to iu mono desu ka?: これは何というものですか? — What’s this called?

kore wa ikura desu ka?: これはいくらですか? — How much is this?

chotto takai desu: ちょっと高いです — It’s a bit expensive

If you haven’t started your adventure of learning Japanese adjectives, then here’s some essential shopping vocabulary:

- yasui (安い ) — Cheap, easy

- takai (高い ) — Expensive, high

- takakunai (高くない ) — Inexpensive

hoka no iro ga arimasu ka?: 他の色がありますか? — Do you have another color?

sore o itadakimasu: それを頂きます — I’ll take it

kurejitto kaado wa tsukaemasu ka?: クレジットカードは使えますか? — Can I use my credit card?

If you’d like to use a traveler’s check, then replace kurejitto kaado with: toraberaazu chekku (トラベラーズチェック ) — traveler’s check.

Your Suica and Pasmo cards, which are rechargeable cards you can use on Japanese trains, can also be used to pay for taxis or your groceries at select stores. You can ask:

Suika wa tsukaemasu ka?

スイカわつかえますか?

Can I use my Suica?

tsutsunde itadakemasu ka?: 包んでいただけますか? — Can I have it gift-wrapped?

Phrases for Casual Conversations

Want to sound like a native when you know minimal Japanese? There are a few common phrases you can use with friends in casual conversations.

yoroshiku onegaishimasu: よろしくお願いします — Nice to meet you (formal)

yoroshiku ne: よろしくね — Nice to meet you (casual)

doushita no?: どうしたの? — What’s wrong?

yabai: やばい — Awful or cool

While talking, your friend may mention they have an important test or date. Use yabai and depending on the context, it can mean “Awful” or “Cool.”

yokatta: 良かった (よかった) — Good, excellent, nice

This is an expression of relief, a bit like, “Oh, thank goodness!”

ganbatte: 頑張って — Do your best

This simple word means either “Good luck” or “Do your best.” In more formal situations, you’d say Ganbatte kudasai (頑張ってください ).

omedetou!: おめでとう! — Congrats!

The formal variant is Omedetou gozaimasu (おめでとうございます ) — Congratulations.

zenzen: 全然 (ぜんぜん) — Not at all (with neg. verb)

In a nutshell, zenzen is the Japanese phrase of denial. It can be used either sincerely or not, such as when answering your mother when she asks, “Am I bothering you?”

maji de?: マジで? — Really?

You can express your surprise with this casual phrase.

hontou?: 本当? (ほんとう?) — Really? / Seriously?

This word translates literally to “truth, reality, actuality, fact.” In question form, it comes across more like a surprised, “Are you serious?”

uso!: うそー! — No way!

This is another way to express surprise, which literally means “Lie!”

yappari: やっぱり — As expected

If you’re not surprised, you can use this word to say, “I knew it!”

Japanese Slang

When you’re making friends, you’ll hear tons of these terms going back and forth. Many slang terms are written in katakana, which marks them as being casual words.

ukeru: ウケる — Funny, hilarious

Say your friend made a great joke—by saying ukeru, you’ll let him know he struck your funny bone.

chou: 超 — Super

This word is used to add emphasis, like the words “really” or “very.” You could say, for example, that something is chou ukeru (超ウケる ), or very funny.

dasai: ださい — Uncool

kimoi: キモい — Gross

Kimoi is a contraction of the words kimochi (気持ち ) — feeling, and warui (悪い ) — bad.

gachi: ガチ — Totally, really, seriously

Gachi implies that something actually took place, or was really as intense as the speaker claims.

hanpa nai: 半端ない — Crazy, insane

Hanpa nai means that something is awesome or insane, but in a good way, like an epic roller coaster ride.

As you can see, context matters a lot in Japanese. To get comfortable with conversational phrases faster, try watching Japanese movies, TV shows or vlogs and look out for the expressions above—they’re very common!

FluentU is a Japanese learning app that uses real Japanese media clips, helping you learn useful phrases in context. These videos also have interactive subtitles and vocabulary lists to show you how native speakers naturally use the phrases above in conversation.

And there you have it! With these phrases and some core vocabulary, you’ll be able to make small talk with new friends, or show others that you’re sincerely interested in learning Japanese.

Just by incorporating a few of these phrases into daily life or conversation, you’ll soon be sure to hear nihongo ga jouzu desu ne! (日本語が上手ですね ) — You’re good at speaking Japanese!

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

In this vocabulary lesson, you will learn how to say “sun” in Japanese. Since the Japanese language has quite a few words for “sun“, I want to go over the most common ones and tell you their meaning, translation, and kanji so that you will be able to use and write them right away.

The two commonly used words to say sun in Japanese are “taiyou” (太陽) and “hi” (日). When referring to the sun as a body of our solar system the word “taiyou” (太陽) is more appropriate. “Hi” (日), on the other hand, is used when the sun affects daily life and in words like “sunrise” and “sunset”.

There are a few other common words that can be used to say sun in Japanese: “ohisama“, “otentousama“, and “san“. So let’s go over the definition and meaning of all the 5 Japanese words for the sun. Further down you will also find more advanced words like “rising sun“, “setting sun“, and the Japanese term for “sun breathing“, which is a technique from the anime “Kimetsu no Yaiba”.

- taiyou – 太陽

- hi – 日 or 陽

- san – サン

- ohisama – お日様

- otentousama – お天道様

1. Taiyou – More Scientific Word for “Sun” in Japanese

The word taiyou (太陽) translates as “sun” and is one of the two most commonly used words to say sun in Japanese. It comes from the Chinese language and should be used when you want to refer to the sun as a body of our solar system or in a more scientific way.

taiyou

太陽

sun

Most of the time when you use the word “solar” in English it is translated as taiyou (太陽) in Japanese. “Solar system“, for example, is taiyou kei (太陽系), and the word for “solar cell” is taiyou denchi (太陽電池) in Japanese. The list goes on and on and on.

taiyou kei

太陽系

solar systemtaiyou denchi

太陽電池

solar celltaiyou enerugii

太陽エネルギー

solar energy

solar power

However, the Japanese word taiyou (太陽) can also be used when talking about the sun in normal daily life expressions and sentences like “the shining sun“, “the sun is shining“, “the sun is bright“, etc.

kagayaku taiyou

輝く太陽

the shining sunTaiyou ga kagayaiteiru.

太陽が輝いている。

The sun is shiningTaiyou ga mabushii

太陽が眩しい。

The sun is bright

In this video, you can see how to write the kanji of the word “taiyou” in Japanese:

2. Hi – Japanese Word Meaning “Sun”, “Sunshine”, or “Day”

Hi (日) is the original Japanese word for sun but has a couple of translations: sun, sunshine, sunlight, day, days, daytime, etc. It is also one of the most common kanji and used in many other words like nihon (日本, Japan) and nichiyoubi (日曜日, Sunday).

hi

日

sun

sunshine

sunlight

day, days

daytime

Whenever you want to talk about the sun in relation to daily life and especially in situations when the sun impacts human lives and activities, this is the word you should use. Since it is a little difficult to explain I recommend you try memorizing the following words and expressions.

hinode

日の出

sunrisehinoiri

日の入り

sunsetHi ga nobotta.

日が昇った。

The sun is up.Hi ga shizundeita.

日が沈んでいた。

The sun has set.Koori wa hi ni ataru to tokeru.

氷は日にあたると溶ける。

Ice melts in the sun.

There is another Japanese kanji that you can use for the sun which is 陽 (hi). In contrast to the more commonly used kanji 日 (hi), it is less often used, though, and only translates as “sun“, “sunshine“, and “sunlight“.

hi

陽

sun

sunshine

sunlight

3. San – English Loanword Mening “Sun”

Similar to the English loanword “sukai” that you can use to say sky in Japanese, there is also one that you can use for the sun. The word san (サン) is pronounced exactly the same as the English word “sun” and therefore very easy to remember.

san

サン

sun

However, the loanword san (サン) is usually only found in names for characters or names for places like Nakano Sanplaza (中野サンプラザ), which is a rather big and famous concert hall in Tokyo. Also, since it is an English loanword it is written in katakana only and there is no kanji.

4. Ohisama – Honorific Way to Say “the Sun” in Japanese

Ohisama means “the Sun” or “Honorable Mr. Sun” and can be written in kanji as お日様, 御日様, or お日さま. This term is commonly used by children to refer to the sun in an honorific and respectful way.

ohisama

お日様

the sun

Honorable Mr. Sun

5. Otentousama – Even More Honorific Word for “the Sun”

Otentousama, which can also be written as Otentosama or O’tento sama, is another even more honorific word for “the Sun”. In kanji, it is either written as お天道様, 御天道様, or お天道さま. To be honest, I have never heard the word before, so I assume it might only be used in a religious context.

otentousama

お天道様

the sun

Honorable Mr. Sun

Advanced Words That Mean “Sun” in Japanese

- asahi – 朝日

- kyokujitsu -旭日

- yuuhi – 夕日

- byakuya – 白夜

- nishibi – 西日

6. Asahi – “Rising Sun” or “Morning Sun”

Asahi (朝日) actually translates as “morning sun“, but is the most common term to say “rising sun” in Japanese. The first kanji 朝 means “morning” and the second kanji 日 means “sun” but also “day”. You can also use the Japanese word hinode (日の出) which translates as “sunrise“.

asahi

朝日

rising sun

morning sun

Another word for “rising sun” is kyokujitsu (旭日). It is used in a few expressions like for example “Rising Sun Flag” which is called kyokujitsuki (旭日旗) or kyokki (旭旗) in Japanese.

kyokujitsu

旭日

rising sun

7. Yuuhi – “Setting Sun” or “Evening Sun”

Yuuhi (夕日) is the Japanese word for “evening sun” or “setting sun“. 夕 (yuu) is the kanji for “evening” in Japanese and 日 (hi) is the kanji for “sun“.

yuuhi

夕日

setting sun

evening sun

8. Byakuya – “Midnight Sun”

Byakuya (白夜), which can also be read as “hakuya“, is the Japanese term used when the sun doesn’t set and translates as “midnight sun“, “night under the midnight sun“, “white night“. The word consists of the kanji 白 which means “white” and the kanji 夜 which means “night“.

byakuya

白夜

white night

midnight sun

night under the midnight sun

9. Nishibi – “Westerning Sun” or “Afternoon Sun”

“Westering Sun” or “afternoon soon” is nishibi (西日) in Japanese, but the word can also be translated as “setting sun“. The first kanji 西 means “west” and the second one is the Japanese kanji for the “sun“.

nishibi

西日

westering sun

afternoon sun

How to Say “Sun and Moon” in Japanese

Taiyou to tsuki (太陽と月) is the common phrase Japanese people use to say “sun and moon“. The first word “taiyou” (太陽) means “sun” and the last word “tsuki” (月) means “moon“. In the middle, we have the particle to (と) which is used to connect nouns and translates as “and“.

taiyou to tsuki

太陽と月

sun and moon

The video games “Pokémon Sun” and “Pokémon Moon“, however, are called “Poketto Monsutaa San” (ポケットモンスター サン) and “Pokemonsutaa Muun” (ポケットモンスター ムーン). Also the anime “Pokémon the Series: Sun & Moon” is called “Poketto Monsutaa San & Muun” (ポケットモンスター サン&ムーン) in Japanese.

Poketto Monsutaa San

ポケットモンスター サン

Pokémon SunPoketto Monsutaa Muun

ポケットモンスター ムーン

Pokémon MoonPoketto Monsutaa San & Muun

ポケットモンスター サン&ムーン

Pokémon the Series: Sun & Moon

How to Say “Sun Breathing” in Japanese (Kimetsu no Yaiba)

In the anime Kimetsu no Yaiba “Hi no kokyu” (日の呼吸) or “hi no kokyuu” (ひのこきゅう) is the Japanese name of the breathing style which is known as “Sun Breathing” in English. The first word “hi” (日) means “sun” and “kokyuu” (呼吸) can be translated as “breathing“, “respiration“, “secret“, or “trick“.

hi no kokyu

日の呼吸

sun breathing

(Kimetsu no Yaiba term)

How to Say “Sun God” and “Sun Goddess” in Japanese

“Taiyoushin” (太陽神) is the Japanese word for “sun god“. It consists of the word taiyou (太陽) which means “sun” and the word shin (神), also read as kami, which means “god“.

taiyoushin

太陽神

sun god

The word for “sun goddess” is Amaterasu (天照). It consists of 天, which is one of the Japanese words and kanji for “sky”, and the kanji 照 for “shine” or “illuminate“.

Amaterasu

天照

sun goddess

The generic word for friend in Japanese is 友人 (yuujin). Japanese people have many different ways to say the word friend. These words depend on how close the relationship is and with whom they are speaking. This article will discuss the words you can use to talk about your friend in Japanese.

Be aware that, unlike in other languages such as English, it isn’t common to refer directly to your friend with these words. They will typically be used to introduce them to other people.

Common Words for Friend in Japanese

Here are some general words for friend in Japanese. Be careful to note the level of politeness or intimacy in each!

1. 友達 (Tomodachi) – Friend

The word 友達 (tomodachi) means friend or friends. The suffix -達 (dachi) is technically the Japanese plural form, but you can use tomodachi to refer to either one friend or many. However, these days, tomodachi has become more of a word meaning “one friend” instead of many. It is still not wrong to refer to many friends as your tomodachi though. It is even possible to add another “たち” to the end to make it clear that you are talking about many friends, like this: 友達たち (tomodachi-tachi).

Also, it recommended by 教育出版 (Kyoiku Shuppan) – a famous company in Japan that publishes educational materials) to write the 達 (tachi) in hiragana like this: 友たち (tomotachi) if you want to make it clear you are talking about more than one friend.

- 友達 (tomodachi) = friend; friends

- 友たち (tomotachi) = friends

The word tomodachi is more casual than the previously mentioned yuujin. Tomodachi is not a slang word, but it also isn’t polite or honorific Japanese. However, you can use tomodachi in everyday conversations with people you don’t know (store workers, people you just meet, etc.).

You can combine tomodachi with other words to express the type of friends you have:

- 男友達 (otoko-tomodachi): male friend(s)

- 女友達 (onna-tomodachi): female friend(s)

- 飲み友達 (nomi-tomodachi): drinking friend(s)

- 遊び友達 (asobi-tomodachi): playmate(s)

You can also use 友達 to refer to anything that is your friend, even if they are not human (examples #3 and 4 below).

Examples:

1. My friend Tom is coming over tonight.

今夜、友達のトムさんが遊びに来る。

(Konya, tomodachi no Tom-san ga asobi ni kuru.)

2. I went to the mall with my friends yesterday.

昨日、友達と一緒にモールに行った。

(Kinou, tomodachi to issho ni mooru ni itta.)

3. I became friends with a neighbor’s dog “Koro”.

僕は近所の犬のコロと友達になりました。

(Boku wa kinjo no inu no Koro to tomodachi ni narimashita.)

4. Books are my friends.

本が私の友達です。

(Hon ga watashi no tomodachi desu.)

2. 友人 (Yuujin) – Friend (Polite)

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, 友人 (yuujin) is the basic and polite way to say friend in Japanese. Translated, it means familiar/friendly person.

Yuujin is a “safe” way to say friend in Japanese because it’s polite—but not too polite. This means that you can use it with people in your inner circle and not come across as cold or aloof. However, it is more formal than tomodachi, which is why you would use 友人 (yuujin) when talking to your superiors (your boss, customers, etc.)

Unlike tomodachi, yuujin can only be used to refer to human friends.

Example:

I received this hat from a friend.

この帽子は友人からもらいました。

(Kono boushi wa yuujin kara moraimashita.)

3. 親友 (Shinyuu) – Best Friend

In Japanese, the word 親友 (shinyuu) is reserved for close friends or friends who you’ve known for a long time. It derives from the same kanji as the adjective 親しい (shitashii), or intimate. You can also refer to a close friend as 親しい友達 (shitashii tomodachi) or 親しい友人 (shitashii yuujin) for the same effect.

Shinyuu has the same nuance as the English phrase best friend. You can make this word even stronger by saying 大親友 (daishinyuu), or very best friend.

Examples:

1. Taro has been my best friend since childhood.

太郎は子供の頃からの親友です。

(Tarou wa kodomo no koro kara no shinyuu desu.)

2. I sent a card to my dear friend in the hospital.

入院 した親しい友達にカードを送りました。

(Nyuuin shita shitashii tomodachi ni kaado o okurimashita.)

4. 仲間 ( Nakama ) – Companion, Comrade

A danger of learning Japanese only through manga or anime is that you might find misleading translations for words like 仲間 (nakama). Many media platforms translate nakama into “friend” or even “buddy.” In reality, the word has far less familiarity with its meaning.

In Japanese, nakama implies comradery, but not necessarily friendship. Your nakama could be a fellow player on your basketball team. They are your nakama whether you are close friends or not.

Of course, nakama does have a positive nuance. It would not be correct to refer to a teammate you dislike as nakama. However, it is a common mistake to refer to your bosom buddy or childhood friend as nakama. Use this word for friend with care.

Example:

Please let me join your team!

仲間に入れてください!

(Nakama ni irete kudasai!)

5. 味方 (Mikata) – Ally, Partner, Comrade

The word 味方 (mikata) is also used often in Japanese media. It also suffers from some translation issues, probably because there is another word with the same pronunciation. 見方 (mikata) is also a common words, but notice that the kanji is different. This 見方 (mikata) means “viewpoint” or “the way you look at something.”

味方 (mikata) on the other hand means ally or partner in English. It is used to describe someone who shares the same group or circumstances that you do.

Like with nakama, you should avoid using the word mikata for people you don’t really like. It is still a far less endearing term than tomodachi or yuujin.

味方 (mikata) can also be used to talk about non-human things that are your friends or allies. (example #3 below)

Example:

1. Yoko took sides with me when the teacher got mad at me.

先生に怒られたとき、洋子さんは私の味方になってくれた。

(Sensei ni okorareta toki, Youko-san wa watashi no mikata ni natte kureta.)

2. I thought you were my ally, but you betrayed me.

味方だと思ってたのに、裏切られた。

(Mikata dato omotteta noni, uragirareta.)

3. I could hit a home run because the wind was on my side.

風が味方してくれたので、ホームランが打てた。

(Kaze ga mikata shite kureta node hoomuran ga uteta.)

Situational Words for Friend

Some words for friend in Japanese can only be used in certain situations or professional relationships. Here are some situation-specific ways to say friend.

6. 相棒 ( Aibou ) – Partner

相棒 (aibou) is a not really a common word for friend in Japanese, but it is used by some people—so long as you and that friend share the same goal or purpose and works towards it together. In certain situations, aibou can even be used to speak about a friend who is also your business partner. Detectives in Japanese dramas may also call each other aibou. This word is a bit friendlier than nakama but is in the same subgenre of meaning.

If you can read the kanji, you may be a little confused. The kanji is comprised of 相 (ai, meaning mutual or each other) and 棒 (bou, meaning stick or rod). What does a stick have to do with being friends?

The origin of the word aibou comes from 2 people who carried a basket (called “kago”) that was used to transport a person back in the olden days of Japan (possibly from before the Edo era, but it is not certain). The pair of basket carriers (called “kago no mono”) called each other aibou. You can read more about it here in Japanese: The meaning of aibou (website in Japanese only).

Example:

My partner here is a well-known writer.

うちの相棒はかなり有名な作家です。

(Uchi no aibou wa kanari yuumei na sakka desu.)

7. 同僚 (Douryou) – Colleague, Associate

If you are friends with a colleague or a close associate, 同僚 (douryou) would be a suitable word to use. 同 (dou) means “same” in Japanese and is used in many other terms. Because douryou implies a similarity between you and your friend, you wouldn’t be able to use the word for a friend in a different workplace or career than yourself.

Example:

Today, my coworker and I went to a ramen shop for our lunch break.

今日の昼休みに、同僚と一緒にラーメン屋さんへ行った。

(Kyou no hiruyasumi ni, douryou to issho ni raamen-ya san e itta.)

8. 同級生 ( Doukyuusei ) – Classmate, Peer

The word 同級生 (doukyuusei) is a way to say friend or peer in Japanese. It’s rooted in Japanese 先輩・後輩 (senpai/kouhai), or senior/junior culture. A doukyuusei is neither a senpai (senior) nor a kouhai (junior). They are someone who is right on level with you, either in age or in rank. Doukyuusei is most often used to refer to a friend who is also a classmate in the same grade.

Example:

John and I were classmates in elementary and middle school.

ジョンさんとは小学校と中学校で同級生だった。

(Jon-san towa shougakkou to chuugakkou de doukyuusei datta.)

Like any other language, Japanese has slang words. Here are a few popular slang terms for friend. Be sure not to use them with your boss or with your elders!

9. 友 ( Tomo ) – Friend (Casual)

You may recognize the kanji in the word 友 (tomo). It’s the same as the first character in tomodachi, and the meaning is the same. Removing the suffix (-dachi) and just saying “tomo“ is a more casual way to say friend in Japanese.

However, this is only when you combine 友 (tomo) with other words. 友 (tomo) by itself is rarely used in daily conversations. It is mostly for written items like poems, songs, or song lyrics. Combining it with other words turns it into a common, conversational word. Some common ones are:

- 飲み友 (nomi-tomo): drinking buddy

- メル友 (meru-tomo): E-pal

Example:

Good morning, friend!

友よ!おはよう!

(Tomo yo! Ohayou!)

10. ダチ ( Dachi ) – Pal, Buddy, Bro

This is the same rule as with tomo but applied to the second half of tomodachi. Although it’s always written in katakana, ダチ (dachi) is the same 達 (dachi) in 友達 (tomodachi).

This is a very casual Japanese slang word. It’s an older term that might not be trendy in daily conversation but is sure to show up in TV dramas or anime. Dachi is also used between friends as a joke or an endearing tease. It is also masculine, so it is usually only used by men.

Example:

We’re pals, right?

俺たちはダチでしょう?

(Oretachi wa dachi deshou?)

11. ツレ ( Tsure ) – Companion

ツレ (tsure) is a Japanese slang word for friend used during social events. It derives from the word 連れ (tsure), or to bring. The implication is that this friend is your “plus one”—it can be romantic or platonic and can be used between husbands and wives.

Example:

I came with my wife, Misaki.

ツレは妻の美咲です。

(Tsure wa tsuma no Misaki desu.)

12. バディー ( Badii ) – Buddy, Compatriot, Partner

As it is a loan word, バディー (badii) is a very casual way to say partner or friend in Japanese. It isn’t a mainstream slang word anymore, but you can still hear it in a classic detective movie or read it in a manga.

Example:

I swear, I’ll save my partner!

俺のバディーを絶対に助けに行く!

(Ore no badii o zettai ni tasuke ni iku!)

Conclusion

There are various ways to say friend in Japanese, depending on your relationship with the friend or the company you find yourself in. If you’re in a pinch, the words yuujin and tomodachi are the most frequently used and are okay to use in most situations.

What are some ways to say friend in your language? Let us know in the comments! Thank you for reading this article on how to say friend in Japanese!

There could be numerous reasons why you might want to say “I don’t know” in Japanese. Especially early on when you’re still a beginner. Being able to tell someone through speech that you don’t understand what they’re saying can save you from a lot of awkward body language.

You’d think that many simple expressions in English would translate fluidly over to Japanese. However, there are many English words and expressions that do not have an exact equivalent in Japanese.

Figuring out the most suitable Japanese translation for what you want to say can sometimes be a hassle. Like when you want to say “good luck” to someone in Japanese for example.

Luckily though, when you want to say “I don’t know” in Japanese, it isn’t that complex! There are two main ways you express your lack of knowledge in something in Japanese. These are 知らない (shiranai) and わからない (wakaranai).

In This Ultimate Guide, I break down the meaning of わからない (wakaranai), 知らない (shiranai) and discuss the differences between them. No longer will you lack a verbal response when you have no idea about something in Japanese. Instead, if you’re lucky, you might even get a 日本語上手 (nihongo jouzu) come your way!

This guide is tailored for beginners and advanced learners alike and goes beyond the bounds of just how to say “I don’t know” in Japanese. I also cover related expressions such as “I have no clue” or “I don’t get it” in Japanese. No matter the situation, formal or casual, you’ll be equipped with the knowledge of the most suitable way on how to say “I don’t know” in Japanese!

Let’s begin!

- I Don’t Know.

知らない。

shiranai.

In most contexts, when you have no clue about something, the best expression (and safest) you can use 知らない (shiranai).

知らない (shiranai) is the negative form of the verb 知る (shiru), which means “to know” in Japanese. Interestingly, the kanji, 知, which is used in both verbs means “wisdom” or “knowledge” in Japanese.

Therefore when you say 知らない (shiranai) in Japanese, you’re saying that you don’t have the wisdom or knowledge about something. 知らない (shiranai) is a very general way to say “I don’t know” in Japanese, and you can even use it in regards to people.

For instance:

- その人をあまり知らない。

sono hito wo amari shiranai.

I don’t really know that person.

That person could be anyone. When you say it like this, you’re saying you have minimal knowledge of the person, their personality etc.

Interesting uses of 知らない (shiranai) can occur during arguments. Say someone you’re engaged in conversation with is doing something you’d never thought they would do. To express your extreme shock, you could say:

- あなたをもう知らない!

anata wo mou shiranai!

I’ve no idea who you are anymore!

You can also use it in regards to objects and other things. Say I were to ask you if you know what The Legend of Zelda is for example…

- それをらない。

sore wo shiranai.

I don’t know what that is.

Essentially, when you don’t have any awareness or knowledge of a topic or thing, you can use 知らない (shiranai) to express it.

A quick thing about “I” and “you” in Japanese… pronouns in Japanese are very frequently omitted when the context is clear. Hence you’ll see them absent in the Japanese translations too.

I Don’t Know in Polite Japanese

As Japanese is a polite language that uses honorifics (keigo), you may need to conjugate 知らない (shiranai) to the polite form depending on the situation.

The polite form is a style of speech that is reserved for situations when you need to speak respectfully. These include, but are not limited to, conversations with your manager, teacher or strangers.

In the polite form, 知らない (shiranai) becomes 知りません (shirimasen). You can use it the same way you would use 知らない (shiranai) when you want to express a lack of knowledge on a topic.

- 今日は給料日ですか? 知りませんでした!

kyou ha kyuuryouhi desu ka? shirimasen deshita!

Today is payday? I didn’t know!

In this example, you’re telling the person that you had no information on the fact that it’s payday.

I Don’t Understand in Japanese

- I Don’t Understand.

わからない。

wakaranai.

わからない (wakaranai) is the second of the two most common expressions to say “I don’t know” in Japanese. Rather than just “I don’t know”, when you use わからない (wakaranai), the meaning is closer to “I don’t understand.”

Consequently, わからない (wakaranai) is reserved for mostly intellectual or emotional matters. When you say わからない (wakaranai) you’re saying that you tried to understand something, but were unable to so you don’t know.

- あなたが言ってることわからない。

anata ga itteru koto wakaranai.

I don’t know what you’re saying.

Or, you can say:

- 日本語がわからない。

nihongo ga wakaranai.

I don’t know/understand Japanese.

In both of these examples, the speaker is saying they don’t know something, but in the context of not being able to understand. Because they don’t understand, despite their efforts they just don’t know.

わからない (wakaranai), and the affirmative form わかる (wakaru), meaning to “understand” in Japanese has a nuance of the trying to relate to the speaker and their words/feelings.

During situations when you’ve tried to understand and establish a deeper connection to a person’s feelings, but are unable to, you can use わからない (wakaranai). Alternatively, if you do understand you can use わかる (wakaru), of course.

- 気持ちいわかる。

kimochi wakaru.

I understand/know how you feel.

Difference Between わからない (wakaranai) & 知らない (shiranai)

Let’s summarise the differences between わからない (wakaranai) and 知らない (shiranai).

知らない (shiranai) is purely informational. When you have not heard/seen or read about a certain topic, you can use 知らない (shiranai). It’s indicative of a lack of superficial information about something. Therefore, when you say 知らない (shiranai), you’re saying that you do not possess information or knowledge on a topic.

Whereas わからない (wakaranai) shows that you tried to understand something but were unable to. Using わからない (wakaranai) invokes a deeper meaning and has a nuance that you tried to relate and connect to the other person.

There is an exception to these rules, and I think it’s worth pointing out so you don’t accidentally say the wrong thing to someone.

If someone were to ask you, “hey is the bus stop around here?” for instance… Based on the explanations I shared above, you might think to say 知らない (shiranai). This is not necessarily wrong, it’s grammatically correct actually. But I think native Japanese speakers would prefer using わからない (wakaranai), or rather, the polite わかりません (wakarimasen) if speaking with a stranger.

This is because わからない (wakaranai) conveys a much softer “no, I don’t know” rather than 知らない (shiranai). Simply saying 知らない (shiranai) can come across as somewhat cold. In this situation, although the speaker is asking for information from you, saying 知らない (shiranai) comes across as a blunt “No, I don’t know, why would I?” kind of answer.

Instead, using わからない (wakaranai) acts as a much gentler negation that conveys something along the lines of “I’m not too sure, I’m not very acquainted with this area” kind of thing.

This is similar to how the Japanese avoid saying “no” directly to things. It’s in the culture to be polite about your response to save the other person’s face.

I Don’t Know At All in Japanese

- I have no clue.

知らん。

shiran.

During situations when you have absolutely no knowledge of an informational topic, you can say 知らん (shiran).

知らん (shiran) is a shortened version of 知らない (shiranai), meaning that it’s a very casual way of saying “I don’t know” in Japanese. They both can be used in the same contexts – those of which you have no awareness or knowledge.

The expression 知らん (shiran) also falls into the Kansai dialect, meaning that it is most frequently used around Osaka, Kyoto, and Nara regions.

- 実はその有名人がだれか知らん。

jitsu ha sono yuumei jin ga dare ka shiran.

Actually, I’ve no clue who that famous person is.

Probably more so than the full-length version, with 知らん (shiran) you can really emphasise you’re completely void of information about something. To emphasise this even further you could say:

- 何も知らん。

nani mo shiran.

I know nothing.

知らん (shiran) is also considered to be Japanese slang, so you really want to avoid using it during situations where you want to show respect.

I Don’t Get it in Japanese

- I don’t get it

わからん。

wakaran.

Similar to the relationship between 知らん (shiran) and 知らない (shiranai), わからん (wakaran) is the shortened version of わからない (wakaranai). Being a shortened version, it is considered to be Japanese slang.

So why would you use わからん (wakaran) over わからない (wakaranai)? They both convey the same meaning of “I don’t understand” in casual Japanese, so what’s the difference?

Well, apart from the former being slang, when you say わからない (wakaranai), you’re essentially saying that you’ve tried to understand (the topic) but were unable to. As a result, you don’t know.

わからん (wakaran) is also indicative of the very same thing, however, it has a bit of the finality of “it’s impossible to understand” to it.

For instance, say you’ve just started taking coding classes. You look at a huge page of Javascript, and your friend does their best to explain it to you. This is your response:

- 何これ?わからん。

nani kore? wakaran.

What is this? I don’t get it.

When you say わからん (wakaran), you’re really placing emphasis on the fact you don’t get it.

I Don’t Understand Well in Japanese

- I don’t understand well.

よくわからない。

yoku wakaranai.

At times when you are unable to understand something very well, you can use わからない.

The first part is よく (yoku), meaning “well” in Japanese. Following after is わからない (wakaranai), which we’ve already looked at above, means “don’t understand”. Consequently, the literal meaning of わからない is “I don’t understand well.”

In particular, this could mean that you were unable to relate to a piece of content, whether that be because you don’t have the same experience, or because it just doesn’t resonate with you. Whichever the reason, you just don’t understand what the thing/person is trying to say.

Perhaps you still couldn’t understand something despite the person sharing their opinion and/or trying to explain something to you. When your understanding is not adequate enough on something, you can use よくわからない (yoku wakaranai). For instance, say you’ve bought a new book.

- この本はかなりずかしくて、何度読んでもよくわからない。

kono hon ha kanari muzukashikute nando yondemo yoku wakaranai.

This book is quite complex, I don’t understand it no matter how many times I read it.

By expressing that you don’t understand something well through よくわからない (yoku wakaranai), it implies that you have tried to understand, but alas to no avail.

I Don’t Really Understand in Japanese

- I don’t really understand.

あまりわからない。

amari wakarnai.

When you have a very limited understanding of something, you can say あまりわからない (amari wakaranai).

The main nuance with あまりわからない (amari wakaranai) is that it implies that there is an absence of a considerable understanding.

What this means is that when you say あまりわからない (amari wakaranai) to someone, you’re telling them that you only understand a little or very minimal.

It does not mean that you are completely clueless, but rather that your knowledge of something is not enough for you to be able to say you understand. For instance when you say:

- 日本語を1年しか勉強しなかったので、あまりわからない。

nihongo wo ichi nen shika benkyou shinakattta node, amari wakaranai

I’ve only studied Japanese for a year, so I’m not really able to understand it.

This sentence could also mean the same as: “I’ve only studied Japanese for a year, so I only understand a little”.

Saying あまりわからない (amari wakaranai) is the same as saying you only possess minimal knowledge on something.

However, because あまり (amari) is used here, there is an emphasis placed on “not really” being able to understand something. This is because あまり (amari) in Japanese is used to express when something is not much. As an example:

- あまり甘いものを食べない。

amari amaimono wo tabenai.

I don’t really eat many sweets.

A perfect response to this might be to express your shock in the form of a “no way!“

I Have Absolutely No Idea in Japanese

- I Have Absolutely No Idea.

全然わからない。

zenzen wakaranai.

As an alternative to the slangy わからん (wakaran), you can also use 全然わからない when you’re completely at a loss.

全然わからない (zenzen wakaranai), is probably the most powerful way to convey an “I have absolutely no idea” or “I absolutely don’t understand” in Japanese. Hence, when you say 全然わからない, you’re saying that you have tried to understand something, but are utterly clueless on it.

For instance, if you completely don’t understand this guide, you could tell me:

- あなたが言ってることを全然わからない。

anata ga itteru koto wo zenzen wakaranai.

I have absolutely no idea what you’re talking about.

I hope that’s not the case, but all feedback is greatly welcomed and appreciated!

The increased emphasis of “absolutely” on this expression comes from 全然 (zenzen).

全然 (zenzen) is used in conjunction with a negative verb to convey the nuance of “not at all,” or “not in the slightest”. So when used together with わからない (wakaranai), it essentially means “I don’t understand at all” in Japanese.

You could even attach 全然 (zenzen) to the beginning of all of the expressions we’ve looked at so far to emphasise them.

Who Knows in Casual Japanese

- Who Knows.

さあ。

saa.

We often use filler words in English to fill those pauses in our speech, and Japanese is the same. Actually, さあ (saa) has a number of different meanings, and can also be used as a filler word. However, in this case, we’re going to look at how it can be used to say “who knows” in Japanese.

When you’ve been asked a question on something that you don’t know the answer to, you can reply with さあ (saa). By replying with さあ (saa), you convey the nuance of “who knows” in Japanese.

Just like how when we say “who knows” in English, we’re kind of shrugging off our opinion or knowledge on the matter, the same concept applies here in Japanese. This means that さあ (saa) is a very casual way to say “I don’t know” in Japanese with a nuance of “I’m not really bothered” kind of thing. Let’s look at a quick example of a conversation. Imagine a detective asking a suspect where the money is.

- 金はどこだ?

kane ha doko da?

Where is the money?

To which they reply:

- さあ…

saa…

Who Knows…

When さあ (saa) in a “who knows” context, it is said somewhat hesitantly with a dragged-out “aah” sound. Ever seen the Harry Potter YouTube video meme with everyone shouting out Wingardium Leviosaaa… Yeah, that “sa” is the exact same. Albeit maybe not that exaggerated, but it’s certainly very similar!

I Don’t Get You in Japanese

- I don’t get you.

理解できない。

rikai dekinai.

When you want to express to someone that you strongly can’t understand something in Japanese, you can say 理解できない (rikai dekinai). The word “strongly” here refers to how much you can’t comprehend/relate to that something.

It is a very powerful expression that expresses your incapability to understand or feel the same thing as the other person. Because of this, you can use 理解できない (rikai dekinai) to say things like “I don’t get you” or “I can’t understand you.”

- 彼を理解できない。

kare wo rikai dekinai.

I don’t get him/ I can’t understand him.

理解できない (rikai dekinai) also uses the verb できない (dekinai) which means “can’t” in Japanese. Therefore, rather than simply meaning “I don’t understand you”, 理解できない (rikai dekinai) heavily emphasises an inability to understand the person.

Saying 理解できない (rikai dekinai) to someone can come across much more personal than simply saying わからない (wakaranai).

I Don’t Know What I Should Do in Japanese

- I don’t know what I should do.

どうすればいい。

dou sureba ii.

Sometimes, when we say “I don’t know”, we want to express our concern about what to do about it a little more. We all reach times in our life when we’re not too sure what the best course of action is.

During these times, it might be best to consult a friend or family member to find an answer. When you say どうすればいい (dousureba ii) to someone, you’re conveying two things.

- You’re saying: I don’t know what I should do.

- You’re asking: What do you think I should do?

どうすればいい (dousureba ii) can be both a statement about the fact you don’t know what to do, as well as an enquiry for advice. This is because of the entities in the expression. The すれば (sureba) part of the expression is one of the four ways of saying “if” in Japanese. In this case, it is the hypothetical “if”.

Secondly the いい (ii) part means “good” in Japanese. Combining this with どう (dou) which can mean “how” or “what” we have a phrase that translates to something like “What would be good if I did it?”

Let’s take a look at an example. Perhaps you’ve landed yourself a job you’ve wanted. Congrats! But you also have the opportunity to go and study abroad for a year. You’re puzzled about what to do, so you might ask/say:

- どうすればいいのかわからない。

dou sureba ii no ka wakaranai.

I’m at a loss about what to do.

The のかわからない (no ka wakaranai) part is optional, but by saying it, you emphasise that you’re really stuck.

To really tell someone you’re completely clueless about what to do you could also say:

- 一体どうすればいい?

ittai dou sureba ii?

I’m at a loss about what to do.

I Don’t Know What I Should Do in Formal Japanese

To say “I don’t know what to do” in Japanese formally, simply attach ですか (desuka) to the end of the expression.

- どうすればいいですか。

dou sureba ii desuka.

What should I do? (I don’t know).

By attaching ですか (desuka), the question element of the expression is more direct. This is because ですか (desuka) is used to make questions in Japanese.

You can also achieve the same thing when using this phrase casually by phrasing it like a question when you say it.

I’m Not Sure in Japanese

- I’m not sure.

どうかな。

dou kana.

When we’re not confident about something, in English we often say things like “I’m not too sure”, or “I wonder”. In Japanese, we can say どうかな (dou kana) to express that same uncertainty.

Perhaps your friends are asking if you can make it to the party, or maybe you’re wondering if it’ll rain tomorrow.

When you’re questioning the legitimacy, truth or possibility of something happening, you can say どうかな (dou kana). You can also use どうかな (dou kana) to say no in indirectly in Japanese to turn down an invitation for instance.

There are two ways you can use this expression. The first is when you want to say “I’m not sure” as a general response. The second is when you want to say you’re not sure about something specifically.

An example of using どうかな (dou kana) as a general response could be when someone asks you if you’re coming to the party later. You’re not so keen so you simply reply with どうかな (dou kana), meaning “I’m not sure.”

You may have also heard どうかしら (dou kashira). The main difference between the two is that どうかしら (dou kashira) is considered to be a feminine style of speech, whereas どうかな (dou kana) is more general. Other than that, they mean the same thing!

- どうかしら.

dou kashira.

I wonder (feminine).

I Wonder If… in Japanese

When you want to express that you’re not sure about something specific, firstly we want to drop the どう (dou) part and keep かな (kana).

This is because かな (kana) is a sentence ending particle that transforms any sentence it’s attached to into an “I’m not sure if…” expression.

Let’s take a look at an example! Say if someone asks you if you think it’s going to rain tomorrow. You can say:

- 明日雨が降るかな.

ashita ame ga furu kana.

I wonder if it’ll rain tomorrow.

かな (kana) is a very flexible particle that can be attached to the end of most sentences to convey an “I wonder”.

- 彼女は本当に大丈夫かな.

kanojo ha hontouni daijobu kana.

I wonder if she is really okay.

As かな (kana) is actually a particle, it is rarely used on its own. The only time you might use it on its own is after a pause in your speech.

- 試験に合格した…かな。

shiken ni goukaku shita… kana

I wonder if… I passed the exam.

When you say it with a pause like this, your uncertainty in regard to the topic may be emphasised.

I Know in Japanese

- I know.

知ってる。

shitteru.

With all of these different ways to express that you don’t know or don’t understand something, what about when you’re on the other side of the spectrum.

That being said, when you want to say “I know” in Japanese, the most general expression is 知ってる (shitteru). You may recall from the first entry of this guide that the affirmative way to say “I know” in Japanese is the verb 知る (shiru). However, to say it naturally, we first have to conjugate 知る (shiru) into te-form. When we do, it becomes 知ってる (shitteru).