IRA FLATOW, host:

That means it’s time for our monthly, well, sort of Science Diction, as we call it. We’re exploring the origins of scientific words with Howard Markel, professor of history of the history of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, also a director at the center for history of medicine there.

Welcome back to SCIENCE FRIDAY, Howard.

Professor HOWARD MARKEL (University of Michigan): Hi, Ira. Happy Earth Day.

FLATOW: Happy Earth Day to you. Have you got a — what’s the word — the good word for today?

Prof. MARKEL: Well, the good word today is robot.

FLATOW: Robot.

Prof. MARKEL: Yeah.

FLATOW: Robot. What is the origin of the word robot? Interesting.

Prof. MARKEL: Well, you know, we all think of these mechanical beings, you know, clad in metal with its blinking lights and making all sorts of funny sounds. And even some people think about modern robots, which help in modern engineering or even the conduct of surgery. But it’s really a new word to the English language.

It was the brainchild of a wonderful Czech playwright, novelist and journalist named Karel Capek. He lived from 1880 to 1938. And he introduced it in 1920 in his hit play «RUR,» or «Rossum’s Universal Robots.»

FLATOW: Does it have a Latin origin, or just — he just made it up out of thin air?

Prof. MARKEL: Well, it comes from an Old Church Slavonic word, rabota, which means servitude of forced labor. The word also has cognates in German, Russian, Polish and Czech. And it’s really a product of Central European system of serfdom, where a tenants’ rent was paid for in forced labor or service.

And he was writing this play about a company, Rossum’s Universal Robots, that was actually using biotechnology. They were mass-producing workers using the latest biology, chemistry and physiology to produce workers who lack nothing but a soul. They couldn’t love. They couldn’t have feelings. But they could do all the works that humans preferred not to do. And, of course, the company was soon inundated with our orders.

Well, when Capek named these creatures, he first came up with a Latin word labori, for labor. But he worried that it sounded a little bit too bookish, and at the suggestion of his brother, Josef, Capek ultimately opted for roboti, or in English, robots.

FLATOW: Wow. And so he needed this for the play.

Prof. MARKEL: Yeah. And, you know, the robots — it’s really a wonderful play. The robots do so well, they really kind of take over Earth. I mean, they take over the army. They take over all the work. Even human women can no longer reproduce because they’ve forgotten how. And so, the robots, after a while, say, hey, enough of this. We’re going to take over the world. We’re doing all the work. So it’s sort of an allegory for a mass revolt of the workers unite and things get really bad. And all but one human being is killed in this play.

FLATOW: Wow.

Prof. MARKEL: The robots realize, oh, no. We’ve killed everybody who knows how to make robots. So they’ve actually guaranteed their extinction. And then there’s this magical moment where two robots, a male and a female robot, suddenly developed the ability to feel, to love and have human emotions, and they go off into the sunset to make the world anew.

(Soundbite of laughter)

FLATOW: Wow. I could the sun’s dawning already.

Prof. MARKEL: Yes, it is.

(Soundbite of laughter)

FLATOW: So it actually had a negative term in the play to begin with, then it sort of got redeemed toward the end.

Prof. MARKEL: Yeah. And, you know, Capek was a very interesting man, an interesting journalist and philosopher. He had — he was a democrat with a little D. He believed in democracy. And, you know, when he wrote this in 1920, there was the — the Soviet Union had started recently with communism, and there was also the World War I that had many people blamed on capitalism and…

FLATOW: Well, wasn’t he also on Hitler’s most-wanted list?

Prof. MARKEL: He was, indeed. And he was a very active opponent of Hitler, and wrote about it. And he was enemy number two on the Gestapo list. And he died in 1938 at the age of 48 of flu, just a few moments before the Gestapo had caught up with him. So he frustrated Hitler (unintelligible).

FLATOW: Oh, okay. Well, this is fascinating. Thank you very much.

Prof. MARKEL: Well, thank you.

FLATOW: And, Howard, we’ll look forward to your next word. I know you’ve been thinking about it with great, robotic detail.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Prof. MARKEL: I hope so.

FLATOW: All right. Thank you, Howard.

Howard Markel is professor of the history of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and director of the Center for the History of Medicine there.

We’ve run out of time for this hour.

Copyright © 2011 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Задание №13482.

Чтение. ОГЭ по английскому

Установите соответствие между заголовками 1 — 8 и текстами A — G. Используйте каждую цифру только один раз. В задании один заголовок лишний.

1. Like me and you

2. Nobody will see you in it

3. Some facts about robots

4. At your service

5. Your own indicator

6. A robot for a pet

7. For coach potatoes

8. They are among us

A. The word ‘robot’ is a Czech word for a servant or slave. It was invented by a Czech writer Karel Capek in 1920. The word ‘robotics’ was first used by Isaac Asimov in 1937 in a story called Robby. The smallest robot in the world is nano-bot. They are small enough to travel inside your blood vessels. One of the hardest things to make a robot do… is walk.

B. Aibo the dog, designed by Sony, can walk, talk and wag its tail. It can express emotions of happiness, sadness, surprise, fear and dislike. You can talk to it and it will respond. Aibo can read your e-mail and take pictures. You can programme Aibo to respond to a specific name. You can also change its software so that it becomes a puppy. You don’t have to clean after it and its feeding is very cheap — just recharge its batteries.

C. If you are sick and tired of helping your parents around the house, then a new robot can be the answer. It has been designed to make the people’s lives easier. This yellow robot with bright eyes can do different jobs for you and help you remember things you have to do. It’s so clever that when his batteries run out, the robot knows that it needs to recharge them and does it itself.

D. Asimo is a humanoid robot. It has two legs, two arms and red lights for eyes. It can walk, talk, climb stairs and even dance. It can also recognize people’s faces, gestures and voices. It took Honda’s engineers 16 years to create Asimo. Today’s model is 120 cm tall and weighs 43 kg. The robot is not for sale because its creators want it to become even more intelligent.

E. If you want to have a robot that can understand how you feel, then the creation of two US scientists will be of interest. They’d like their model to be sensitive to our moods and emotions. Their robot won’t have emotions of its own but it should be able to respond to its owner’s mood. So, if you feel sad, the robot will ask if it can help you. It’s not an easy job because everyone shows emotions in quite different ways.

F. A Japanese professor has invented an invisibility coat. A camera on the back of the person’s head films the scene behind them and projects it onto the coat. The technology has practical applications: in the future doctors could see ‘through’ their hands or other obstacles when they are doing operations.

G. An amazing new sofa has been invented by a group of scientists in Northern Ireland. As soon as you sit down on it, it will know it’s you. The sofa is connected to a computer and weighs you when you sit on it, then it checks its memory and decides who you are. Then it’ll be able to set lots of electrical appliances just how you like them, like the lights or maybe the TV without you having to move a finger.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

Решение:

Заголовок 3 (Some facts about robots. — Некоторые факты о роботах) соответствует содержанию текста A: «The smallest robot in the world is nano-bot. They are small…»

Заголовок 6 (A robot for a pet. — Робот для домашнего питомца) соответствует содержанию текста B: «Aibo the dog, designed by Sony, can walk, talk and wag its tail.»

Заголовок 4 (At your service. — К вашим услугам) соответствует содержанию текста C: «It has been designed to make the people’s lives easier.»

Заголовок 1 (Like me and you. — Как я и ты) соответствует содержанию текста D: «Asimo is a humanoid robot. It has two legs, two arms…»

Заголовок 5 (Your own indicator. — Ваш собственный индикатор) соответствует содержанию текста E: «They’d like their model to be sensitive to our moods and emotions.»

Заголовок 2 (Nobody will see you in it. — Никто тебя в нем не увидит) соответствует содержанию текста F: «A Japanese professor has invented an invisibility coat.»

Заголовок 7 (For coach potatoes. — Для лентяев.) соответствует содержанию текста G: «An amazing new sofa has been invented…»

Показать ответ

Источник: ОГЭ-2019. 30 тренировочных вариантов. Л. М. Гудкова, О. В. Терентьева

Сообщить об ошибке

Тест с похожими заданиями

Karel Čapek’s play «R.U.R.» premiered in January 1921. Its influence cannot be overstated.

By the time his play “R.U.R.” (which stands for “Rossum’s Universal Robots”) premiered in Prague in 1921, Karel Čapek was a well-known Czech intellectual. Like many of his peers, he was appalled by the carnage wrought by the mechanical and chemical weapons that marked World War I as a departure from previous combat. He was also deeply skeptical of the utopian notions of science and technology. “The product of the human brain has escaped the control of human hands,” Čapek told the London Saturday Review following the play’s premiere. “This is the comedy of science.”

In that same interview, Čapek reflected on the origin of one of the play’s characters:

The old inventor, Mr. Rossum (whose name translated into English signifies “Mr. Intellectual” or “Mr. Brain”), is a typical representative of the scientific materialism of the last [nineteenth] century. His desire to create an artificial man — in the chemical and biological, not mechanical sense — is inspired by a foolish and obstinate wish to prove God to be unnecessary and absurd. Young Rossum is the modern scientist, untroubled by metaphysical ideas; scientific experiment is to him the road to industrial production. He is not concerned to prove, but to manufacture.

Thus, “R.U.R.,” which gave birth to the robot, was a critique of mechanization and the ways it can dehumanize people. The word itself derives from the Czech word “robota,” or forced labor, as done by serfs. Its Slavic linguistic root, “rab,” means “slave.” The original word for robots more accurately defines androids, then, in that they were neither metallic nor mechanical.

The contrast between robots as mechanical slaves and potentially rebellious destroyers of their human makers echoes Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” and helps set the tone for later Western characterizations of robots as slaves straining against their lot, ready to burst out of control. The duality echoes throughout the twentieth century: Terminator, HAL 9000, Blade Runner’s replicants.

The character Helena in “R.U.R.” is sympathetic, wanting the robots to have freedom. Radius is the robot that understands his station and chafes at the idiocy of his makers, having acted out his frustrations by smashing statues.

Helena: Poor Radius. … Couldn’t you control yourself? Now they’ll send you to the stamping mill. Won’t you speak? Why did it happen to you? You see, Radius, you are better than the rest. Dr. Gall took such trouble to make you different. Won’t you speak?

Radius: Send me to the stamping mill.

Helena: I am sorry they are going to kill you. Why weren’t you more careful?

Radius: I won’t work for you. Put me into the stamping mill.

Helena: Why do you hate us?

Radius: You are not like the Robots. You are not as skillful as the Robots. The Robots can do everything. You only give orders. You talk more than is necessary.

Helena: That’s foolish Radius. Tell me, has any one upset you? I should so much like you to understand me.

Radius: You do nothing but talk.

Helena: Dr. Gall gave you a larger brain than the rest, larger than ours, the largest in the world. You are not like the other Robots, Radius. You understand me perfectly.

Radius: I don’t want any master. I know everything for myself.

Helena: That’s why I had you put into the library, so that you could read everything, understand everything, and then — Oh, Radius, I wanted to show the whole world that the Robots were our equals. That’s what I wanted of you.

Radius: I don’t want any master. I want to be master over others.

Helena’s compassion saves Radius from the stamping mill, and he later leads the robot revolution that displaces the humans from power. Čapek is none too subtle in portraying the triumph of artificial humans over their creators:

Radius: The power of man has fallen. By gaining possession of the factory we have become masters of everything. The period of mankind has passed away. A new world has arisen. … Mankind is no more. Mankind gave us too little life. We wanted more life.

Humans were doomed in the play even before Radius led the revolt. When mechanization overtakes basic human traits, people lose the ability to reproduce. As robots increase in capability, vitality, and self-awareness, humans become more like their machines — humans and robots, in Čapek’s critique, are essentially one and the same. The measure of worth, industrial productivity, is won by the robots that can do the work of “two and a half men.” Such a contest implicitly critiques the efficiency movement that emerged just before World War I, which ignored many essential human traits.

The debt of “R.U.R.” to Shelley’s “Frankenstein” is substantial, even though the works are separated by almost exactly a century. In both cases, humans show hubris by trying to create artificial life. (Recall that even today, Rodney Brooks, an esteemed roboticist and former director of the MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab, refers to robots as “our creatures.”) Whether humans get the recipe wrong, as in the earlier novel, or make beings smarter than the humans who spawned them, as in the case of Čapek’s play and its offspring, humans pay the price for aspiring to play God. In both works, the flawed relationship between creator and creature drives the plot, and in both cases, the conflict ends in bloodshed.

Few people today know “R.U.R.” But in its time, the play was a sensation, with translations into more than 30 languages immediately after publication. Nearly 100 years on, apart from our obvious reliance on the play’s terminology and worldview, we still hear its echoes. The author and play title turn up as Easter eggs in such popular venues as Batman cartoons, Star Trek, Dr. Who, and Futurama: The people who portray our culture’s robots certainly know of their debt to Čapek, even if most of us do not.

John Jordan is a technology analyst and Clinical Professor of Supply Chain and Information Systems in Smeal College of Business at Penn State University. He is the author of “Robots” and “3D Printing,” both in the MIT Press Essential Knowledge series.

1921: A play about robots premieres at the National Theater in Prague, the capital of what was then Czechoslovakia.

R.U.R, (which stands for Rossum’s Universal Robots) by Karel Capek, marks the first use of the word «robot» to describe an artificial person. Capek invented the term, basing it on the Czech word for «forced labor.» (Robot entered the English language in 1923.)

See Also:

All Hail Our Robot Overlords! Sci-Fi’s Best Bots

The 50 Best Robots Ever

Robot Bartenders Sling Cocktails for Carbon-Based DrinkersThe robots in Capek’s play are not mechanical men made of metal. Instead they are molded out of a chemical batter, and they look exactly like humans.

In the course of just 15 years, the price of a robot has dropped from $10,000 to $150. In today’s money, that’s $128,000 down to $1,900.

Each robot «can do the work of two-and-a-half human laborers,» so that humans might be free to have «no other task, no other work, no other cares» than perfecting themselves.

However, the robots come to realize that even though they have «no passion, no history, no soul,» they are stronger and smarter than humans. They kill every human but one.

The play explores themes that would later become staples of robot science fiction, including freedom, love and destruction. Although many of Capek’s other works were more famous during his lifetime, today he is best known for RUR.

The first recorded human death by robot occurred Jan. 25, 1979: the 58th anniversary of the play’s premiere.

Source: Center for the Study of Technology and Society

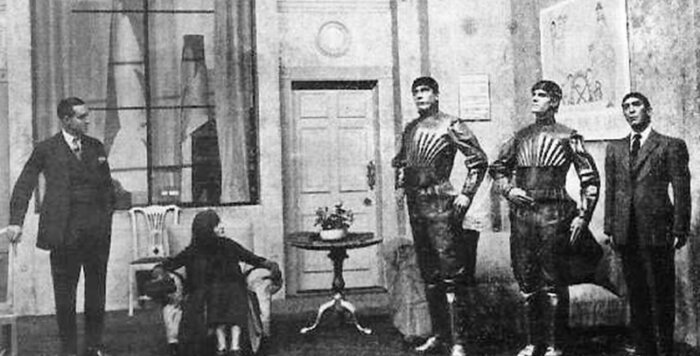

Photo: A scene from R.U.R. features three robots.

This article first appeared on Wired.com Jan. 25, 2007.

See Also:

- Nov. 1, 1909: ‘The Machine Stops’

- Awesome iPhone-Controlled Beer Robot with Air Cannon, Webcam

- Anybots Robot Will Go to the Office for You

- How Wired.com Built Beer Robot, Our DIY Kegerator

- More Wired.com coverage of Robotics

- Taliban: Calling All Playwrights, Singers, Poets

- Dec. 9, 1921: Get the Lead In … Gasoline

- Jan. 25, 1945: Fluoridation

- Jan. 25, 1979: Robot Kills Human

The interesting origins of a ubiquitous word

Here’s a question for you: when did the word ‘robot’ first enter the English language? And where did it come from? There are a few misconceptions about the origins and various meanings of the term ‘robot’, so the issue is worth examining a little more closely. The most common definition of ‘robot’ is the one provided by the Oxford English Dictionary: ‘An intelligent artificial being typically made of metal and resembling in some way a human or other animal.’ But the story of how the word came to have this meaning is a curious one. Its origin, indeed, takes us back to nineteenth-century Europe.

‘Robot’ makes its debut in the English language, perhaps surprisingly, during the Victorian age: the first citation is from 1839. But it doesn’t refer to the humanoid machines of a million science-fiction novels and films made since, but rather to a ‘central European system of serfdom, by which a tenant’s rent was paid in forced labour or service’ (OED). This word came to English via the German, though the word ultimately derives from the Czech robota

The modern meaning of the word ‘robot’ has its origins in a 1920 play by the remarkable and fascinating Czech writer Karel Čapek. The play, titled R. U. R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), begins in a factory which manufactures artificial people, the ‘universal robots’ of the play’s title.

The robots are designed to serve humans and work for them, but the robots eventually turn on their masters, wiping out the human race (shades, or rather foreshadowings, of The Terminator here).

This sense of ‘robot’ is taken from the earlier one defined above – namely, the Czech for ‘slave worker’ or ‘drudge’. But Karel Čapek himself didn’t coin the word. As we’ve already seen, the word was in existence before he wrote his play. But nor did Čapek come up with the idea of taking the word ‘robot’ and using it to describe the man-made beings that feature in R. U. R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots). He originally called them labori, from the Latin for ‘work’, but it was his brother, Josef Čapek, who suggested roboti.

Curiously, the robots which feature in Rossum’s Universal Robots aren’t really robots – at least, not if we’re being picky and technical. They are closer to androids or cyborgs than robots, because they can be mistaken for real people (again, think of the Terminator in his/her many incarnations). So the first ‘robots’ in literature to be so named were, in a sense, misnamed – or rather, we’ve been misusing the term ever since. Such is the way language develops.

In 1938, Čapek’s play was adapted by the BBC, and became the first piece of television science fiction ever to be broadcast.

Science fiction author Isaac Asimov is credited with inventing the spin-off word ‘robotic’ – Asimov famously formulated the Three Laws of Robotics. Curiously, there are technically four Laws – a ‘zeroth’ law was added later (no doubt inspired by the Laws of Thermodynamics).

So there we have it: the origin of ‘robot’ is stranger than it might first seem. You can continue to explore the unusual stories behind well-known words with the surprising origins of the word virus, the history behind the word vaccine, and the reason why the word homophobia meant something quite different when it was first coined.

Image: A scene from the original stage production of Rossum’s Universal Robots, via Wikimedia Commons.