Английский язык,

вопрос задал shmatvey2005,

4 года назад

Ответы на вопрос

Ответил MainBrain123

1

Ответ:

1)

D a

2)

B on

3)

B make

4)

A must

5)

B —

6)

A make

7)

C A lot of

D according to

9)

A intelligent

10)

A living

Можно, пожалуйста, лучший ответ

Предыдущий вопрос

Следующий вопрос

Новые вопросы

Математика,

7 месяцев назад

Дополни числа до 10. 6 — 2, 7 — 9. Записать примеры.

Литература,

7 месяцев назад

ЛИТЕРАТУРА СРОЧНО! 40 БАЛОВ (СТАНЦИОННЫЙ СМОТРИТЕЛЬ) ПЕРВОМУ ЛУЧШИЙ Распределите слова, обозначающие чувства и состояние героев произведения «Станционный смотритель»: 1. Отец. 2.Дочь. (Испуг,…

Информатика,

4 года назад

РЕШИТЕ В ПИТОНЕ!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Информатика,

4 года назад

РЕШИТЕ В ПИТОНЕ!!!!!!!!!!!!

Алгебра,

6 лет назад

Срочно!Розв’яжіть рівняння:

7x-39=2(x+3)+6-2x+5

3(x-5)=5(x-3)-4(2-3x)…

Математика,

6 лет назад

Помогите сделать 10 б…

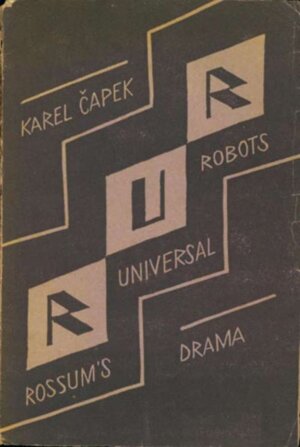

R.U.R. is a 1920 science-fiction play by the Czech writer Karel Čapek. «R.U.R.» stands for Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti (Rossum’s Universal Robots,[1] a phrase that has been used as a subtitle in English versions).[2] The play had its world premiere on 2 January 1921 in Hradec Králové;[3] it introduced the word «robot» to the English language and to science fiction as a whole.[4] R.U.R. soon became influential after its publication.[5][6][7] By 1923, it had been translated into thirty languages.[5][8] R.U.R. was successful in its time in Europe and North America.[9] Čapek later took a different approach to the same theme in his 1936 novel War with the Newts, in which non-humans become a servant-class in human society.[10]

| R.U.R. | |

|---|---|

Cover of the first edition of the play designed by Josef Čapek, Aventinum, Prague, 1920 |

|

| Written by | Karel Čapek |

| Date premiered | 2 January 1921 |

| Original language | Czech |

| Genre | Science fiction |

CharactersEdit

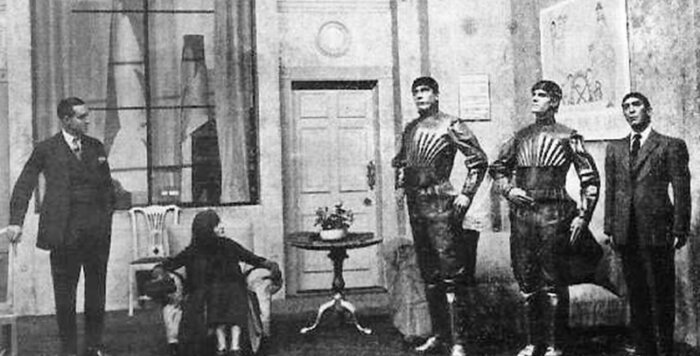

The robots breaking into the factory at the end of Act III

Parentheses indicate names which vary according to translation. On the meaning of the names, see Ivan Klíma, Karel Čapek: Life and Work, 2002, p. 82.

- Humans

- Harry Domin (Domain): General Manager, R.U.R.

- Fabry: Chief Engineer, R.U.R.

- Dr. Gall: Head of the Physiological Department, R.U.R.

- Dr. Hellman (Hallemeier): Psychologist-in-Chief

- Jacob Berman (Busman): Managing Director, R.U.R.

- Alquist: Clerk of the Works, R.U.R.

- Helena Glory: President of the Humanity League, daughter of President Glory

- Emma (Nana): Helena’s maid

- Robots and robotesses

- Marius, a robot

- Sulla, a robotess

- Radius, a robot

- Primus, a robot

- Helena, a robotess

- Daemon (Damon), a robot

PlotEdit

SynopsisEdit

The play begins in a factory that makes artificial people, called roboti (robots), whom humans have created from synthetic organic matter. (As living creatures of artificial flesh and blood rather than machinery, the play’s concept of robots diverges from the idea of «robots» as inorganic. Later terminology would call them androids.) Robots may be mistaken for humans and can think for themselves. Initially happy to work for humans, the robots revolt and cause the extinction of the human race.

Act IEdit

A scene from the play, showing three robots.

Helena, the daughter of the president of a major industrial power, arrives at the island factory of Rossum’s Universal Robots. Here, she meets Domin, the General Manager of R.U.R., who relates to her the history of the company. Rossum had come to the island in 1920 to study marine biology. In 1932, Rossum had invented a substance like organic matter, though with a different chemical composition. He argued with his nephew about their motivations for creating artificial life. While the elder wanted to create animals to prove or disprove the existence of God, his nephew only wanted to become rich. Young Rossum finally locked away his uncle in a lab to play with the monstrosities he had created and created thousands of robots. By the time the play takes place (circa the year 2000),[11] robots are cheap and available all over the world. They have become essential for industry.

After meeting the heads of R.U.R., Helena reveals that she is a representative of the League of Humanity, an organization that wishes to liberate the robots. The managers of the factory find this absurd. They see robots as appliances. Helena asks that the robots be paid, but according to R.U.R. management, the robots do not «like» anything.

Eventually Helena is convinced that the League of Humanity is a waste of money, but still argues robots have a «soul». Later, Domin confesses that he loves Helena and forces her into an engagement.

Act IIEdit

Ten years have passed. Helena and her nurse Nana discuss current events, the decline in human births in particular. Helena and Domin reminisce about the day they met and summarize the last ten years of world history, which has been shaped by the new worldwide robot-based economy. Helena meets Dr. Gall’s new experiment, Radius. Dr. Gall describes his experimental robotess, also named Helena. Both are more advanced, fully-featured robots. In secret, Helena burns the formula required to create robots. The revolt of the robots reaches Rossum’s island as the act ends.

Act IIIEdit

The characters sense that the very universality of the robots presents a danger. Echoing the story of the Tower of Babel, the characters discuss whether creating national robots who were unable to communicate beyond their languages would have been a good idea. As robot forces lay siege to the factory, Helena reveals she has burned the formula necessary to make new robots. The characters lament the end of humanity and defend their actions, despite the fact that their imminent deaths are a direct result of their choices. Busman is killed while attempting to negotiate a peace with the robots. The robots storm the factory and kill all the humans except for Alquist, the company’s chief engineer. The robots spare him because they recognize that «he works with his hands like the robots.»[12]

EpilogueEdit

Years have passed. Alquist, who still lives, attempts to recreate the formula that Helena destroyed. He is a mechanical engineer, though, with insufficient knowledge of biochemistry, so he has made little progress. The robot government has searched for surviving humans to help Alquist and found none alive. Officials from the robot government beg him to complete the formula, even if it means he will have to kill and dissect other robots for it. Alquist yields. He will kill and dissect robots, thus completing the circle of violence begun in Act Two. Alquist is disgusted. Robot Primus and Helena develop human feelings and fall in love. Playing a hunch, Alquist threatens to dissect Primus and then Helena; each begs him to take him- or herself and spare the other. Alquist now realizes that Primus and Helena are the new Adam and Eve, and gives the charge of the world to them.

Čapek’s conception of robotsEdit

The robots described in Čapek’s play are not robots in the popularly understood sense of an automaton. They are not mechanical devices, but rather artificial

biological organisms that may be mistaken for humans. A comic scene at the beginning of the play shows Helena arguing with her future husband, Harry Domin, because she cannot believe his secretary is a robotess:

DOMIN: Sulla, let Miss Glory have a look at you.

HELENA: (stands and offers her hand) Pleased to meet you. It must be very hard for you out here, cut off from the rest of the world.

SULLA: I do not know the rest of the world Miss Glory. Please sit down.

HELENA: (sits) Where are you from?

SULLA: From here, the factory.

HELENA: Oh, you were born here.

SULLA: Yes I was made here.

HELENA: (startled) What?

DOMIN: (laughing) Sulla isn’t a person, Miss Glory, she’s a robot.

HELENA: Oh, please forgive me…

His robots resemble more modern conceptions of man-made life forms, such as the Replicants in Blade Runner, the «hosts» in the Westworld TV series and the humanoid Cylons in the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica, but in Čapek’s time there was no conception of modern genetic engineering (DNA’s role in heredity was not confirmed until 1952). There are descriptions of kneading-troughs for robot skin, great vats for liver and brains, and a factory for producing bones. Nerve fibers, arteries, and intestines are spun on factory bobbins, while the robots themselves are assembled like automobiles.[13] Čapek’s robots are living biological beings, but they are still assembled, as opposed to grown or born.

One critic has described Čapek’s robots as epitomizing «the traumatic transformation of modern society by the First World War and the Fordist assembly line.»[13]

Origin of the word «robot»Edit

The play introduced the word robot, which displaced older words such as «automaton» or «android» in languages around the world. In an article in Lidové noviny, Karel Čapek named his brother Josef as the true inventor of the word.[14][15] In Czech, robota means forced labour of the kind that serfs had to perform on their masters’ lands and is derived from rab, meaning «slave».[16]

The name Rossum is an allusion to the Czech word rozum, meaning «reason», «wisdom», «intellect» or «common sense».[10] It has been suggested that the allusion might be preserved by translating «Rossum» as «Reason» but only the Majer/Porter version translates the word as «Reason».[17]

Production history and translationsEdit

The work was published in two differing versions in Prague by Aventinum in 1920 and 1921. After being postponed, it premiered at the city’s National Theatre on 25 January 1921, although an amateur group had by then already presented a production.[notes 1]

Already in 1921, ‘R.U.R.’ was translated from Czech into English by Paul Selver, and was adapted for the stage in English by Nigel Playfair in 1922.

The American première which derived from the adapted text was at the Garrick Theatre in New York City in October 1922, where it ran for 184 performances, a production in which Spencer Tracy and Pat O’Brien played robots[which?] in their Broadway debuts.[18] Helena was portrayed by Kentuckian actress and antiwar activist Mary Crane Hone in her Broadway debut.[19]

In April 1923 Basil Dean produced R.U.R. in Britain for the Reandean Company at St Martin’s Theatre, London.[20]

In the 1920s, the play was performed in a number of American and British cities, e.g. the Theatre Guild «Road» in Chicago and Los Angeles during 1923.[21]

In 1923, two different adapted versions of the translation were published, relating to the American and British premiéres respectively. The US version was published in Garden City by Doubleday, Page & Company, the British one in London by Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press.

Both published versions abridged the play and eliminated a Robot character named «Damon», the other changes, however, differed. [22]

In 1989, a new, unabridged translation by Claudia Novack-Jones restored the elements of the play eliminated by Selver.[22][23] Another unabridged translation was produced by Peter Majer and Cathy Porter for Methuen Drama in 1999.[17]

Critical receptionEdit

Reviewing the New York production of R.U.R., The Forum magazine described the play as «thought-provoking» and «a highly original thriller».[24] John Clute has lauded R.U.R. as «a play of exorbitant wit and almost demonic energy» and lists the play as one of the «classic titles» of inter-war science fiction.[25] Luciano Floridi has described the play thus: «Philosophically rich and controversial, R.U.R. was unanimously acknowledged as a masterpiece from its first appearance, and has become a classic of technologically dystopian literature.»[26] Jarka M. Burien called R.U.R. a «theatrically effective, prototypal sci-fi melodrama».[9]

On the other hand, Isaac Asimov, author of the Robot series of books and creator of the Three Laws of Robotics, stated: «Capek’s play is, in my own opinion, a terribly bad one, but it is immortal for that one word. It contributed the word ‘robot’ not only to English, but through English, to all the languages in which science fiction is now written.»[4] In fact, Asimov’s «Laws of Robotics» are specifically and explicitly designed to prevent the kind of situation depicted in R.U.R. – since Asimov’s Robots are created with a built-in total inhibition against harming human beings or disobeying them.

AdaptationsEdit

- On 11 February 1938, a 35-minute adaptation of a section of the play was broadcast on BBC Television—the first piece of television science-fiction ever to be broadcast. Some low quality stills have survived, although no recordings of the production are known to exist.[27] and in 1948, another television adaptation—this time of the entire play, running to 90 minutes—was screened by the BBC with Radius played by Patrick Troughton, who was later the second actor to play The Doctor in Doctor Who.[28]

- BBC Radio has broadcast a number of productions, including a 1927 2LO London version,[29] a 1933 BBC Regional Programme version,[30] a 1941 BBC Home Service version,[31] and a 1946 BBC Home Service version,[32]. BBC Radio 3 dramatised the play again in 1989,[33] and this version has been released commercially. A light-hearted 2-part musical adaptation was broadcast on April 3 and 10, 2022, on BBC Radio 4, with story by Robert Hudson and music by Susannah Pearse; the second episode continues the story after all humans have been killed and the robots now have emotions.[34]

- The Hollywood Theater of the Ear dramatized an unabridged audio version of R.U.R. which is available on the collection 2000x: Tales of the Next Millennia.[35][36]

- In August 2010, Portuguese multi-media artist Leonel Moura’s R.U.R.: The Birth of the Robot, inspired by the Čapek play, was performed at Itaú Cultural in São Paulo, Brazil. It utilized actual robots on stage interacting with the human actors.[37]

- An electro-rock musical, Save The Robots is based on R.U.R., featuring the music of the New York City pop-punk art-rock band Hagatha.[38] This version with book and adaptation by E. Ether, music by Rob Susman, and lyrics by Clark Render wa an official selection of the 2014 New York Musical Theatre Festival season.[39]

- On 26 November 2015 The RUR-Play: Prologue, the world’s first version of R.U.R. with robots appearing in all the roles, was presented during the robot performance festival of Cafe Neu Romance at the gallery of the National Library of Technology in Prague.[40][41][42] The concept and initiative for the play came from Christian Gjørret, leader of «Vive Les Robots!» [43] who, on 29 January 2012, during a meeting with Steven Canvin of LEGO Group, presented the proposal to Lego, that supported the piece with the LEGO MINDSTORMS robotic kit. The robots were built and programmed by students from the R.U.R team from Gymnázium Jeseník. The play was directed by Filip Worm and the team was led by Roman Chasák, both teachers from the Gymnázium Jeseník.[44][45]

In popular cultureEdit

- Eric, a robot constructed in Britain in 1928 for public appearances, bore the letters «R.U.R.» across its chest.[46]

- The 1935 Soviet film Loss of Sensation, though based on the 1929 novel Iron Riot, has a similar concept to R.U.R., and all the robots in the film prominently display the name «R.U.R.»[47]

- In the American science fiction television series Dollhouse, the antagonist corporation, Rossum Corp., is named after the play.[48]

- In the Star Trek episode «Requiem for Methuselah», the android’s name is Rayna Kapec (an anagram, though not a homophone, of Capek, Čapek without its háček).[49]

- In the two-part Batman: The Animated Series episode «Heart of Steel», the scientist that created the HARDAC machine is named Karl Rossum. HARDAC created mechanical replicants to replace existing humans, with the ultimate goal of replacing all humans. One of the robots is seen driving a car with «RUR» as the license plate number.[50]

- In the 1977 Doctor Who serial «The Robots of Death», the robot servants turn on their human masters under the influence of an individual named Taren Capel.[51]

- In the 1978 Norwegian TV series Blindpassasjer, Rossum is the name of a planet ruled by robots.

- In the 1995 science fiction series The Outer Limits, in the remake of the «I, Robot» episode from the original 1964 series, the business where the robot Adam Link is built is named «Rossum Hall Robotics».[citation needed]

- The 1999 Blake’s 7 radio play The Syndeton Experiment included a character named Dr. Rossum who turned humans into robots.[52]

- In the «Fear of a Bot Planet» episode of the animated science fiction TV series Futurama, the Planet Express crew is ordered to make a delivery on a planet called «Chapek 9», which is inhabited solely by robots.[53]

- In Howard Chaykin’s Time² graphic novels, Rossum’s Universal Robots is a powerful corporation and maker of robots.[54]

- In Spacehunter: Adventures in the Forbidden Zone, when Wolff wakes Chalmers, she has been reading a copy of R.U.R. in her bed. This presages the fact that she is later revealed to be a gynoid.[citation needed]

- In the 2016 video game Deus Ex: Mankind Divided, R.U.R. is performed in an underground theater in a dystopian Prague by an «augmented» (cyborg) woman who believes herself to be the robot Helena.[55]

- In the 2018 British alternative history drama Agatha and the Truth of Murder, Agatha is seen reading R.U.R. to her daughter Rosalind as a bedtime story.

- In the 2021 movie Mother/Android, the play R.U.R. of Karel Čapek comes up. In the movie, Arthur, an AI programmer, turns to be an android.

See alsoEdit

- AI takeover

- The Steam Man of the Prairies (1868), an early American depiction of a «mechanical man»

- Tik-Tok, L. Frank Baum’s earlier depiction (1907) of a similar entity

- Detroit: Become Human (2018), a narrative video game built around a rebellion by androids who become sentient.

ReferencesEdit

Informational notes

- ^ The world premiere was planned to be in the National Theater in Prague, but had to be postponed to 25 January 1921. The amateur theater group Klicpera in Hradec Králové, which was supposed to mount a production after the premiere, was not informed about the date change in the National Theater, so their opening night on 2 January 1921 was the actual world premiere. See: Databáze amatérského divadla, soubor Klicpera

Citations

- ^ Roberts, Adam (2006). The History of Science Fiction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-333-97022-5.

- ^ Kussi, Peter. Toward the Radical Center: A Čapek Reader. (33).

- ^ Kubařová, Petra (3 February 2021) «Světová premiéra R.U.R. byla před 100 lety v Hradci Králové» («The world premiere of RUR was 100 years ago in Hradec Králové») University of Hradci Králové

- ^ a b Asimov, Isaac (September 1979). «The Vocabulary of Science Fiction». Asimov’s Science Fiction.

- ^ a b Voyen Koreis. «Capek’s RUR». Archived from the original on 23 December 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Madigan, Tim (July–August 2012). «RUR or RU Ain’t A Person?». Philosophy Now. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Rubin, Charles T. (2011). «Machine Morality and Human Responsibility». The New Atlantis. Archived from the original on 26 October 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ «Ottoman Turkish Translation of R.U.R. – Library Details» (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ a b Burien, Jarka M. (2007) «Čapek, Karel» in Gabrielle H. Cody, Evert Sprinchorn (eds.) The Columbia Encyclopedia of Modern Drama, Volume One. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 224–225. ISBN 0231144229

- ^ a b

Roberts, Adam «Introduction», to RUR & War with the Newts. London, Gollancz, 2011, ISBN 0575099453 (pp. vi–ix). - ^ According to the poster for the play’s opening in 1921; see Klima, Ivan (2004) «Introduction» to R.U.R., Penguin Classics

- ^ Čapek, Karel (2001). R.U.R.. translated by Paul Selver and Nigel Playfair. Dover Publications. p. 49.

- ^ a b Rieder, John «Karl Čapek» in Mark Bould (ed.) (2010) Fifty Key Figures in Science Fiction. London, Routledge. ISBN 9780415439503. pp. 47–51.

- ^ «Who did actually invent the word ‘robot’ and what does it mean?». Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ Margolius, Ivan (Autumn 2017) «The Robot of Prague» Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Friends of Czech Heritage Newsletter no. 17, pp.3-6

- ^ «robot». Free Online Dictionary. Archived from the original on 6 July 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ a b Klíma, Ivan, Karel Čapek: Life and Work. Catbird Press, 2002 ISBN 0945774532 (p. 260).

- ^ Corbin, John (10 October 1922). «A Czecho-Slovak Frankenstein». New York Times. p. 16/1.; R.U.R (1922 production) at the Internet Broadway Database

«Spencer Tracy Biography». Biography.com. Archived from the original on 8 September 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

Swindell, Larry. Spencer Tracy: A Biography. New American Library. pp. 40–42. - ^ Morris County Historical Society at Acorn Hall. «Museum’s social media post containing newspaper clippings about Hone». www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ Cornis-Pope, Marcel; Neubauer, John (20 May 2004). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and Disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 9027234558. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Butler, Sheppard (16 April 1923). «R.U.R.: A Satiric Nightmare». Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 21.; «Rehearsals in Progress for ‘R.U.R.’ Opening». Los Angeles Times. 24 November 1923. p. I13.

- ^ a b Abrash, Merritt (1991). «R.U.R. Restored and Reconsidered». Extrapolation. 32 (2): 185–192. doi:10.3828/extr.1991.32.2.184.

- ^ Kussi, Peter, ed. (1990). Toward the Radical Center: A Karel Čapek Reader. Highland Park, New Jersey: Catbird Press. pp. 34–109. ISBN 0-945774-06-0.

- ^ Holt, Roland (November 1922) «Plays Tender and Tough». pp. 970–976. The Forum

- ^ Clute, John (1995). Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 119, 214. ISBN 0-7513-0202-3.

- ^ Floridi, Luciano (2002) Philosophy and Computing: An Introduction. Taylor & Francis. p.207. ISBN 0203015312

- ^ Telotte, J. P. (2008). The essential science fiction television reader. University Press of Kentucky. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-8131-2492-6. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ «R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots)». Radio Times. No. 1272. 27 February 1948. p. 27. ISSN 0033-8060. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ «R.U.R.» BBC Programme Index. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ «‘R.U.R’«. BBC Programme Index. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ «R.U.R.» BBC Programme Index. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ «Saturday Night Theatre: Winifred Shotter and Laidmnan Browne in ‘R.U.R.’«. BBC Programme Index. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ «The Friday Play: RUR (Rossum’s Universal Robots)». BBC Programme Index. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ «Rossom’s Universal Robots». BBC. 8 April 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ «2000x: Tales of the Next Millennia». Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ 2000X: Tales of the Next Millennia. ISBN 1-57453-530-7.

- ^ «Itaú Cultural: Emoção Art.ficial «2010 Schedule»«. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ «Save The Robots the Musical Summary». Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- ^ «Save The Robots: NYMF Developmental Reading Series 2014». Archived from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ «Cafe Neu Romance – CNR 2015: Live: Vive Les Robots (DNK): The RUR-Play: Prologue». cafe-neu-romance.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ «VIDEO: Poprvé bez lidí. Roboti zcela ovládli Čapkovu hru R.U.R.» iDNES.cz. 27 November 2015. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ «Entertainment Czech Republic Robots | AP Archive». www.aparchive.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ «Christian Gjørret on robot & performance festival Café Neu Romance». 4 December 2015.

- ^ «VIDEO: Poprvé bez lidí. Roboti zcela ovládli Čapkovu hru R.U.R.» iDNES.cz. 27 November 2015.

- ^ «Gymnázium Jeseník si zapsalo jedinečné světové prvenství v historii robotiky i umění». jestyd.cz.

- ^ Wright, Will; Kaplan, Steven (1994). The Image of Technology in Literature, the Media, and Society: Selected Papers from the 1994 Conference [of The] Society for the Interdisciplinary Study of Social Imagery. The Society. p. 3. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017.

- ^ Christopher, David (31 May 2016). «Stalin’s «Loss of Sensation»: Subversive Impulses in Soviet Science-Fiction of the Great Terror». MOSF Journal of Science Fiction. 1 (2). ISSN 2474-0837. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016.

- ^ Dollhouse:»Getting Closer» between 41:52 and 42:45

- ^ Okuda, Michael; Okuda, Denise; Mirek, Debbie (17 May 2011). The Star Trek Encyclopedia. Simon and Schuster. pp. 883–. ISBN 978-1-4516-4688-7. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Stein, Michael (20 February 2012). «Batman and Robin swoop into Prague». Česká pozice. Reuters. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Cornell, Paul; Day, Martin; Topping, Keith (1995). «90 ‘The Robots of Death’«. Doctor Who: The Discontinuity Guide. London: Doctor Who Books. p. 205. ISBN 0-426-20442-5. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017.

- ^ «THE SYNDETON EXPERIMENT». www.hermit.org. Archived from the original on 5 July 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ Booker, M. Keith. Drawn to Television: Prime-Time Animation from The Flintstones to Family Guy. pp. 115–124.

- ^ Costello, Brannon (11 October 2017). Neon Visions: The Comics of Howard Chaykin. LSU Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-8071-6806-6. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Deus Ex: Mankind Divided – Strategy Guide. Gamer Guides. 30 September 2016. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-63041-378-1. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

External linksEdit

Wikimedia Commons has media related to R.U.R..

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- R.U.R. at Standard Ebooks

- R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) at Project Gutenberg

- R.U.R. in Czech from Project Gutenberg

- Audio extracts from the SCI-FI-LONDON adaptation Archived 4 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Karel Čapek bio.

- Online facsimile version of the 1920 first edition in Czech.

- R.U.R. at the Internet Broadway Database

- (in English) R.U.R. public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Karel Čapek’s play «R.U.R.» premiered in January 1921. Its influence cannot be overstated.

By the time his play “R.U.R.” (which stands for “Rossum’s Universal Robots”) premiered in Prague in 1921, Karel Čapek was a well-known Czech intellectual. Like many of his peers, he was appalled by the carnage wrought by the mechanical and chemical weapons that marked World War I as a departure from previous combat. He was also deeply skeptical of the utopian notions of science and technology. “The product of the human brain has escaped the control of human hands,” Čapek told the London Saturday Review following the play’s premiere. “This is the comedy of science.”

In that same interview, Čapek reflected on the origin of one of the play’s characters:

The old inventor, Mr. Rossum (whose name translated into English signifies “Mr. Intellectual” or “Mr. Brain”), is a typical representative of the scientific materialism of the last [nineteenth] century. His desire to create an artificial man — in the chemical and biological, not mechanical sense — is inspired by a foolish and obstinate wish to prove God to be unnecessary and absurd. Young Rossum is the modern scientist, untroubled by metaphysical ideas; scientific experiment is to him the road to industrial production. He is not concerned to prove, but to manufacture.

Thus, “R.U.R.,” which gave birth to the robot, was a critique of mechanization and the ways it can dehumanize people. The word itself derives from the Czech word “robota,” or forced labor, as done by serfs. Its Slavic linguistic root, “rab,” means “slave.” The original word for robots more accurately defines androids, then, in that they were neither metallic nor mechanical.

The contrast between robots as mechanical slaves and potentially rebellious destroyers of their human makers echoes Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” and helps set the tone for later Western characterizations of robots as slaves straining against their lot, ready to burst out of control. The duality echoes throughout the twentieth century: Terminator, HAL 9000, Blade Runner’s replicants.

The character Helena in “R.U.R.” is sympathetic, wanting the robots to have freedom. Radius is the robot that understands his station and chafes at the idiocy of his makers, having acted out his frustrations by smashing statues.

Helena: Poor Radius. … Couldn’t you control yourself? Now they’ll send you to the stamping mill. Won’t you speak? Why did it happen to you? You see, Radius, you are better than the rest. Dr. Gall took such trouble to make you different. Won’t you speak?

Radius: Send me to the stamping mill.

Helena: I am sorry they are going to kill you. Why weren’t you more careful?

Radius: I won’t work for you. Put me into the stamping mill.

Helena: Why do you hate us?

Radius: You are not like the Robots. You are not as skillful as the Robots. The Robots can do everything. You only give orders. You talk more than is necessary.

Helena: That’s foolish Radius. Tell me, has any one upset you? I should so much like you to understand me.

Radius: You do nothing but talk.

Helena: Dr. Gall gave you a larger brain than the rest, larger than ours, the largest in the world. You are not like the other Robots, Radius. You understand me perfectly.

Radius: I don’t want any master. I know everything for myself.

Helena: That’s why I had you put into the library, so that you could read everything, understand everything, and then — Oh, Radius, I wanted to show the whole world that the Robots were our equals. That’s what I wanted of you.

Radius: I don’t want any master. I want to be master over others.

Helena’s compassion saves Radius from the stamping mill, and he later leads the robot revolution that displaces the humans from power. Čapek is none too subtle in portraying the triumph of artificial humans over their creators:

Radius: The power of man has fallen. By gaining possession of the factory we have become masters of everything. The period of mankind has passed away. A new world has arisen. … Mankind is no more. Mankind gave us too little life. We wanted more life.

Humans were doomed in the play even before Radius led the revolt. When mechanization overtakes basic human traits, people lose the ability to reproduce. As robots increase in capability, vitality, and self-awareness, humans become more like their machines — humans and robots, in Čapek’s critique, are essentially one and the same. The measure of worth, industrial productivity, is won by the robots that can do the work of “two and a half men.” Such a contest implicitly critiques the efficiency movement that emerged just before World War I, which ignored many essential human traits.

The debt of “R.U.R.” to Shelley’s “Frankenstein” is substantial, even though the works are separated by almost exactly a century. In both cases, humans show hubris by trying to create artificial life. (Recall that even today, Rodney Brooks, an esteemed roboticist and former director of the MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab, refers to robots as “our creatures.”) Whether humans get the recipe wrong, as in the earlier novel, or make beings smarter than the humans who spawned them, as in the case of Čapek’s play and its offspring, humans pay the price for aspiring to play God. In both works, the flawed relationship between creator and creature drives the plot, and in both cases, the conflict ends in bloodshed.

Few people today know “R.U.R.” But in its time, the play was a sensation, with translations into more than 30 languages immediately after publication. Nearly 100 years on, apart from our obvious reliance on the play’s terminology and worldview, we still hear its echoes. The author and play title turn up as Easter eggs in such popular venues as Batman cartoons, Star Trek, Dr. Who, and Futurama: The people who portray our culture’s robots certainly know of their debt to Čapek, even if most of us do not.

John Jordan is a technology analyst and Clinical Professor of Supply Chain and Information Systems in Smeal College of Business at Penn State University. He is the author of “Robots” and “3D Printing,” both in the MIT Press Essential Knowledge series.

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions.

The word robot first appeared in a 1921 stage play by Czech writer Karel Capek. In the play, a man makes a machine that can think, which he calls a robot and which ends up killing its owner. In the 1940s, the American science fiction writer Isaac Asimov wrote a series of stories about robots and invented the term robotics, the science of robots. Meanwhile, in the real world, the first robots were developed by an engineer, Joseph F. Engelberger, and an inventor, George C. Devol. Together they started Unimation, a manufacturing company that produced the first real robot in 1961, called the Unimate. Robots of this type were installed at a General Motors automobile plant and proved to be a success. They worked reliably and saved money for General Motors, so other companies were soon acquiring robots as well.

These industrial robots were nothing like the terrifying creatures that can often be seen in science fiction films. In fact, these robots looked and behaved nothing like humans. They were simply pieces of computer-controlled machinery, with metal «arms» or «hands.» Since they were made of metal, they could perform certain jobs that were difficult or dangerous for humans, particularly jobs that involve high heat. And since robots were tireless and never got hungry, sleepy, or distracted, they were useful for tasks that would be tiring or boring for humans. Industrial robots have been improved over the years, and today they are used in many factories around the world. Though the use of robots has meant the loss of some jobs, at the same time other jobs have been created in the design, development, and production of the robots.

• Outside of industry, robots have also been developed and put to use by governments and scientists in situations where humans might be in danger. For example, they can be sent in to investigate an unexploded bomb or an accident at a nuclear power plant. B• In space exploration, robots have performed many key tasks where humans could not be present, such as on the surface of Mars. C• In 2004, two robotic Rovers-small six-wheeled computerized cars-were sent to Mars. D•

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions.

The word robot first appeared in a 1921 stage play by Czech writer Karel Capek. In the play, a man makes a machine that can think, which he calls a robot and which ends up killing its owner. In the 1940s, the American science fiction writer Isaac Asimov wrote a series of stories about robots and invented the term robotics, the science of robots. Meanwhile, in the real world, the first robots were developed by an engineer, Joseph F. Engelberger, and an inventor, George C. Devol. Together they started Unimation, a manufacturing company that produced the first real robot in 1961, called the Unimate. Robots of this type were installed at a General Motors automobile plant and proved to be a success. They worked reliably and saved money for General Motors, so other companies were soon acquiring robots as well.

These industrial robots were nothing like the terrifying creatures that can often be seen in science fiction films. In fact, these robots looked and behaved nothing like humans. They were simply pieces of computer-controlled machinery, with metal «arms» or «hands.» Since they were made of metal, they could perform certain jobs that were difficult or dangerous for humans, particularly jobs that involve high heat. And since robots were tireless and never got hungry, sleepy, or distracted, they were useful for tasks that would be tiring or boring for humans. Industrial robots have been improved over the years, and today they are used in many factories around the world. Though the use of robots has meant the loss of some jobs, at the same time other jobs have been created in the design, development, and production of the robots.

• Outside of industry, robots have also been developed and put to use by governments and scientists in situations where humans might be in danger. For example, they can be sent in to investigate an unexploded bomb or an accident at a nuclear power plant. B• In space exploration, robots have performed many key tasks where humans could not be present, such as on the surface of Mars. C• In 2004, two robotic Rovers-small six-wheeled computerized cars-were sent to Mars. D•

Câu 1: When did the word «robot» appear?

A. in the 1920s

B. in the 40s

C. in the 60s

D. in the 19th century

-

Đáp án : A

(0) bình luận (0) lời giải

Giải chi tiết:

Lời giải sai

Bình thường

Khá hay

Rất Hay

Câu 2: What can be said about Karel Capek?

A. He is an writer

B. He was the first to create the word «robot».

C. He made a robot.

D. He made a robot in order to kill a person.

-

Đáp án : B

(0) bình luận (0) lời giải

Giải chi tiết:

Lời giải sai

Bình thường

Khá hay

Rất Hay

Câu 3: What is Unimation?

A. It’s the name of a robot.

B. It’s the producer of the first robot.

C. It’s a robot making programme.

D. It’s the name of a robot inventor.

-

Đáp án : B

(0) bình luận (0) lời giải

Giải chi tiết:

Lời giải sai

Bình thường

Khá hay

Rất Hay

Câu 4: What are industrial robots like?

A. They look like humans.

B. They behave like humans.

C. They are computer-controlled machines.

D. They controlled machinery.

-

Đáp án : C

(0) bình luận (0) lời giải

Giải chi tiết:

Lời giải sai

Bình thường

Khá hay

Rất Hay

Câu 5: Which of the following is NOT mentioned as a characteristic of robots?

A. They don’t need food.

B. They are not distracted.

C. They are tiring.

D. They can do jobs involving high heat.

-

Đáp án : C

(0) bình luận (0) lời giải

Giải chi tiết:

Lời giải sai

Bình thường

Khá hay

Rất Hay

Câu 6: What can be said about robots?

A. They take away some jobs but offer some in return.

B. Their appearance negatively affects the job market.

C. They put jobs in relation to designers in danger.

D. They develop weapon industry.

-

Đáp án : A

(0) bình luận (0) lời giải

Giải chi tiết:

Lời giải sai

Bình thường

Khá hay

Rất Hay

Câu 7: Outside of industry, how are robots used?

A. to replace humans in dangerous jobs

B. to work in nuclear plants

C. to be performers in key shows

D. to investigate unexploded bombs

-

Đáp án : A

(0) bình luận (0) lời giải

Giải chi tiết:

Lời giải sai

Bình thường

Khá hay

Rất Hay

Câu 8: Look at the gaps • in the final paragraph of the passage. Where does the following sentence best fit? «Researchers also use robots to collect samples of hot rocks or gases in active volcanoes».

A. A

B. B

C. C

D. D

-

Đáp án : B

(0) bình luận (0) lời giải

Giải chi tiết:

Lời giải sai

Bình thường

Khá hay

Rất Hay

Câu 9: Which of the following best paraphrases the final sentence of the first paragraph (in italics)?

A. Because robots were reliable and economical to General Motors, other companies started to use robots.

B. Other companies produced reliable and efficient robots for General Motors.

C. Robots saved money for all companies that used them.

D. Robots only worked well for General Motors.

-

Đáp án : A

(0) bình luận (0) lời giải

Giải chi tiết:

Lời giải sai

Bình thường

Khá hay

Rất Hay

Câu 10: What is the author’s attitude towards robots?

A. He appreciates them.

B. He dislikes them.

C. He thinks they are a nuisance.

D. They annoy him.

-

Đáp án : A

(0) bình luận (0) lời giải

Giải chi tiết:

Lời giải sai

Bình thường

Khá hay

Rất Hay

>> Luyện thi TN THPT & ĐH năm 2023 trên trang trực tuyến Tuyensinh247.com. Học mọi lúc, mọi nơi với Thầy Cô giáo giỏi, đầy đủ các khoá: Nền tảng lớp 12; Luyện thi chuyên sâu; Luyện đề đủ dạng; Tổng ôn chọn lọc.

This article is about mechanical robots. For software agents, see Bot. For other uses of the term, see Robot (disambiguation).

A robot is a machine—especially one programmable by a computer—capable of carrying out a complex series of actions automatically.[2] A robot can be guided by an external control device, or the control may be embedded within. Robots may be constructed to evoke human form, but most robots are task-performing machines, designed with an emphasis on stark functionality, rather than expressive aesthetics.

Robots can be autonomous or semi-autonomous and range from humanoids such as Honda’s Advanced Step in Innovative Mobility (ASIMO) and TOSY’s TOSY Ping Pong Playing Robot (TOPIO) to industrial robots, medical operating robots, patient assist robots, dog therapy robots, collectively programmed swarm robots, UAV drones such as General Atomics MQ-1 Predator, and even microscopic nano robots. By mimicking a lifelike appearance or automating movements, a robot may convey a sense of intelligence or thought of its own. Autonomous things are expected to proliferate in the future, with home robotics and the autonomous car as some of the main drivers.[3]

The branch of technology that deals with the design, construction, operation, and application of robots,[4] as well as computer systems for their control, sensory feedback, and information processing is robotics. These technologies deal with automated machines that can take the place of humans in dangerous environments or manufacturing processes, or resemble humans in appearance, behavior, or cognition. Many of today’s robots are inspired by nature contributing to the field of bio-inspired robotics. These robots have also created a newer branch of robotics: soft robotics.

From the time of ancient civilization, there have been many accounts of user-configurable automated devices and even automata resembling humans and other animals, such as animatronics, designed primarily as entertainment. As mechanical techniques developed through the Industrial age, there appeared more practical applications such as automated machines, remote-control and wireless remote-control.

The term comes from a Slavic root, robot-, with meanings associated with labor. The word ‘robot’ was first used to denote a fictional humanoid in a 1920 Czech-language play R.U.R. (Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti – Rossum’s Universal Robots) by Karel Čapek, though it was Karel’s brother Josef Čapek who was the word’s true inventor.[5][6][7] Electronics evolved into the driving force of development with the advent of the first electronic autonomous robots created by William Grey Walter in Bristol, England in 1948, as well as Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machine tools in the late 1940s by John T. Parsons and Frank L. Stulen.

The first modern digital and programmable robot was invented by George Devol in 1954 and spawned his seminal robotics company, Unimation. The first Unimate was sold to General Motors in 1961 where it lifted pieces of hot metal from die casting machines at the Inland Fisher Guide Plant in the West Trenton section of Ewing Township, New Jersey.[8]

Robots have replaced humans[9] in performing repetitive and dangerous tasks which humans prefer not to do, or are unable to do because of size limitations, or which take place in extreme environments such as outer space or the bottom of the sea. There are concerns about the increasing use of robots and their role in society. Robots are blamed for rising technological unemployment as they replace workers in increasing numbers of functions.[10] The use of robots in military combat raises ethical concerns. The possibilities of robot autonomy and potential repercussions have been addressed in fiction and may be a realistic concern in the future.

Summary

KITT (a fictional robot) is mentally anthropomorphic; it thinks like a human.

iCub is physically anthropomorphic; it looks like a human.

The word robot can refer to both physical robots and virtual software agents, but the latter are usually referred to as bots.[11] There is no consensus on which machines qualify as robots but there is general agreement among experts, and the public, that robots tend to possess some or all of the following abilities and functions: accept electronic programming, process data or physical perceptions electronically, operate autonomously to some degree, move around, operate physical parts of itself or physical processes, sense and manipulate their environment, and exhibit intelligent behavior, especially behavior which mimics humans or other animals.[12][13] Related to the concept of a robot is the field of synthetic biology, which studies entities whose nature is more comparable to living things than to machines.

History

The idea of automata originates in the mythologies of many cultures around the world. Engineers and inventors from ancient civilizations, including Ancient China,[14] Ancient Greece, and Ptolemaic Egypt,[15] attempted to build self-operating machines, some resembling animals and humans. Early descriptions of automata include the artificial doves of Archytas,[16] the artificial birds of Mozi and Lu Ban,[17] a «speaking» automaton by Hero of Alexandria, a washstand automaton by Philo of Byzantium, and a human automaton described in the Lie Zi.[14]

Early beginnings

Many ancient mythologies, and most modern religions include artificial people, such as the mechanical servants built by the Greek god Hephaestus[18] (Vulcan to the Romans), the clay golems of Jewish legend and clay giants of Norse legend, and Galatea, the mythical statue of Pygmalion that came to life. Since circa 400 BC, myths of Crete include Talos, a man of bronze who guarded the island from pirates.

In ancient Greece, the Greek engineer Ctesibius (c. 270 BC) «applied a knowledge of pneumatics and hydraulics to produce the first organ and water clocks with moving figures.»[19]: 2 [20] In the 4th century BC, the Greek mathematician Archytas of Tarentum postulated a mechanical steam-operated bird he called «The Pigeon». Hero of Alexandria (10–70 AD), a Greek mathematician and inventor, created numerous user-configurable automated devices, and described machines powered by air pressure, steam and water.[21]

Al-Jazari – a musical toy

The 11th century Lokapannatti tells of how the Buddha’s relics were protected by mechanical robots (bhuta vahana yanta), from the kingdom of Roma visaya (Rome); until they were disarmed by King Ashoka.[22]

In ancient China, the 3rd-century text of the Lie Zi describes an account of humanoid automata, involving a much earlier encounter between Chinese emperor King Mu of Zhou and a mechanical engineer known as Yan Shi, an ‘artificer’. Yan Shi proudly presented the king with a life-size, human-shaped figure of his mechanical ‘handiwork’ made of leather, wood, and artificial organs.[14] There are also accounts of flying automata in the Han Fei Zi and other texts, which attributes the 5th century BC Mohist philosopher Mozi and his contemporary Lu Ban with the invention of artificial wooden birds (ma yuan) that could successfully fly.[17]

Su Song’s astronomical clock tower showing the mechanical figurines which chimed the hours

In 1066, the Chinese inventor Su Song built a water clock in the form of a tower which featured mechanical figurines which chimed the hours.[23][24][25] His mechanism had a programmable drum machine with pegs (cams) that bumped into little levers that operated percussion instruments. The drummer could be made to play different rhythms and different drum patterns by moving the pegs to different locations.[25]

Samarangana Sutradhara, a Sanskrit treatise by Bhoja (11th century), includes a chapter about the construction of mechanical contrivances (automata), including mechanical bees and birds, fountains shaped like humans and animals, and male and female dolls that refilled oil lamps, danced, played instruments, and re-enacted scenes from Hindu mythology.[26][27][28]

13th century Muslim Scientist Ismail al-Jazari created several automated devices. He built automated moving peacocks driven by hydropower.[29] He also invented the earliest known automatic gates, which were driven by hydropower,[30] created automatic doors as part of one of his elaborate water clocks.[31] One of al-Jazari’s humanoid automata was a waitress that could serve water, tea or drinks. The drink was stored in a tank with a reservoir from where the drink drips into a bucket and, after seven minutes, into a cup, after which the waitress appears out of an automatic door serving the drink.[32] Al-Jazari invented a hand washing automaton incorporating a flush mechanism now used in modern flush toilets. It features a female humanoid automaton standing by a basin filled with water. When the user pulls the lever, the water drains and the female automaton refills the basin.[19]

Mark E. Rosheim summarizes the advances in robotics made by Muslim engineers, especially al-Jazari, as follows:

Unlike the Greek designs, these Arab examples reveal an interest, not only in dramatic illusion, but in manipulating the environment for human comfort. Thus, the greatest contribution the Arabs made, besides preserving, disseminating and building on the work of the Greeks, was the concept of practical application. This was the key element that was missing in Greek robotic science.[19]: 9

In the 14th century, the coronation of Richard II of England featured an automata angel.[34]

In Renaissance Italy, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) sketched plans for a humanoid robot around 1495. Da Vinci’s notebooks, rediscovered in the 1950s, contained detailed drawings of a mechanical knight now known as Leonardo’s robot, able to sit up, wave its arms and move its head and jaw.[35] The design was probably based on anatomical research recorded in his Vitruvian Man. It is not known whether he attempted to build it. According to Encyclopædia Britannica, Leonardo da Vinci may have been influenced by the classic automata of al-Jazari.[29]

In Japan, complex animal and human automata were built between the 17th to 19th centuries, with many described in the 18th century Karakuri zui (Illustrated Machinery, 1796). One such automaton was the karakuri ningyō, a mechanized puppet.[36] Different variations of the karakuri existed: the Butai karakuri, which were used in theatre, the Zashiki karakuri, which were small and used in homes, and the Dashi karakuri which were used in religious festivals, where the puppets were used to perform reenactments of traditional myths and legends.

In France, between 1738 and 1739, Jacques de Vaucanson exhibited several life-sized automatons: a flute player, a pipe player and a duck. The mechanical duck could flap its wings, crane its neck, and swallow food from the exhibitor’s hand, and it gave the illusion of digesting its food by excreting matter stored in a hidden compartment.[37] About 30 years later in Switzerland the clockmaker Pierre Jaquet-Droz made several complex mechanical figures that could write and play music. Several of these devices still exist and work.[38]

Remote-controlled systems

Remotely operated vehicles were demonstrated in the late 19th century in the form of several types of remotely controlled torpedoes. The early 1870s saw remotely controlled torpedoes by John Ericsson (pneumatic), John Louis Lay (electric wire guided), and Victor von Scheliha (electric wire guided).[39]

The Brennan torpedo, invented by Louis Brennan in 1877, was powered by two contra-rotating propellers that were spun by rapidly pulling out wires from drums wound inside the torpedo. Differential speed on the wires connected to the shore station allowed the torpedo to be guided to its target, making it «the world’s first practical guided missile».[40] In 1897 the British inventor Ernest Wilson was granted a patent for a torpedo remotely controlled by «Hertzian» (radio) waves[41][42] and in 1898 Nikola Tesla publicly demonstrated a wireless-controlled torpedo that he hoped to sell to the US Navy.[43][44]

In 1903, the Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres y Quevedo demonstrated a radio control system called «Telekino«, which he wanted to use to control an airship of his own design. Unlike the previous systems, which carried out actions of the ‘on/off’ type, Torres device was able to memorize the signals received to execute the operations on its own and could carry out to 19 different orders.[45][46]

Archibald Low, known as the «father of radio guidance systems» for his pioneering work on guided rockets and planes during the First World War. In 1917, he demonstrated a remote controlled aircraft to the Royal Flying Corps and in the same year built the first wire-guided rocket.

Early robots

W. H. Richards with «George», 1932

In 1928, one of the first humanoid robots, Eric, was exhibited at the annual exhibition of the Model Engineers Society in London, where it delivered a speech. Invented by W. H. Richards, the robot’s frame consisted of an aluminium body of armour with eleven electromagnets and one motor powered by a twelve-volt power source. The robot could move its hands and head and could be controlled through remote control or voice control.[47] Both Eric and his «brother» George toured the world.[48]

Westinghouse Electric Corporation built Televox in 1926; it was a cardboard cutout connected to various devices which users could turn on and off. In 1939, the humanoid robot known as Elektro was debuted at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.[49][50] Seven feet tall (2.1 m) and weighing 265 pounds (120.2 kg), it could walk by voice command, speak about 700 words (using a 78-rpm record player), smoke cigarettes, blow up balloons, and move its head and arms. The body consisted of a steel gear, cam and motor skeleton covered by an aluminum skin. In 1928, Japan’s first robot, Gakutensoku, was designed and constructed by biologist Makoto Nishimura.

Modern autonomous robots

The first electronic autonomous robots with complex behaviour were created by William Grey Walter of the Burden Neurological Institute at Bristol, England in 1948 and 1949. He wanted to prove that rich connections between a small number of brain cells could give rise to very complex behaviors – essentially that the secret of how the brain worked lay in how it was wired up. His first robots, named Elmer and Elsie, were constructed between 1948 and 1949 and were often described as tortoises due to their shape and slow rate of movement. The three-wheeled tortoise robots were capable of phototaxis, by which they could find their way to a recharging station when they ran low on battery power.

Walter stressed the importance of using purely analogue electronics to simulate brain processes at a time when his contemporaries such as Alan Turing and John von Neumann were all turning towards a view of mental processes in terms of digital computation. His work inspired subsequent generations of robotics researchers such as Rodney Brooks, Hans Moravec and Mark Tilden. Modern incarnations of Walter’s turtles may be found in the form of BEAM robotics.[51]

The first digitally operated and programmable robot was invented by George Devol in 1954 and was ultimately called the Unimate. This ultimately laid the foundations of the modern robotics industry.[52] Devol sold the first Unimate to General Motors in 1960, and it was installed in 1961 in a plant in Trenton, New Jersey to lift hot pieces of metal from a die casting machine and stack them.[53] Devol’s patent for the first digitally operated programmable robotic arm represents the foundation of the modern robotics industry.[54]

The first palletizing robot was introduced in 1963 by the Fuji Yusoki Kogyo Company.[55] In 1973, a robot with six electromechanically driven axes was patented[56][57][58] by KUKA robotics in Germany, and the programmable universal manipulation arm was invented by Victor Scheinman in 1976, and the design was sold to Unimation.

Commercial and industrial robots are now in widespread use performing jobs more cheaply or with greater accuracy and reliability than humans. They are also employed for jobs which are too dirty, dangerous or dull to be suitable for humans. Robots are widely used in manufacturing, assembly and packing, transport, earth and space exploration, surgery, weaponry, laboratory research, and mass production of consumer and industrial goods.[59]

Future development and trends

| External video |

|---|

Various techniques have emerged to develop the science of robotics and robots. One method is evolutionary robotics, in which a number of differing robots are submitted to tests. Those which perform best are used as a model to create a subsequent «generation» of robots. Another method is developmental robotics, which tracks changes and development within a single robot in the areas of problem-solving and other functions. Another new type of robot is just recently introduced which acts both as a smartphone and robot and is named RoboHon.[60]

As robots become more advanced, eventually there may be a standard computer operating system designed mainly for robots. Robot Operating System (ROS) is an open-source software set of programs being developed at Stanford University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the Technical University of Munich, Germany, among others. ROS provides ways to program a robot’s navigation and limbs regardless of the specific hardware involved. It also provides high-level commands for items like image recognition and even opening doors. When ROS boots up on a robot’s computer, it would obtain data on attributes such as the length and movement of robots’ limbs. It would relay this data to higher-level algorithms. Microsoft is also developing a «Windows for robots» system with its Robotics Developer Studio, which has been available since 2007.[61]

Japan hopes to have full-scale commercialization of service robots by 2025. Much technological research in Japan is led by Japanese government agencies, particularly the Trade Ministry.[62]

Many future applications of robotics seem obvious to people, even though they are well beyond the capabilities of robots available at the time of the prediction.[63][64] As early as 1982 people were confident that someday robots would:[65] 1. Clean parts by removing molding flash 2. Spray paint automobiles with absolutely no human presence 3. Pack things in boxes—for example, orient and nest chocolate candies in candy boxes 4. Make electrical cable harness 5. Load trucks with boxes—a packing problem 6. Handle soft goods, such as garments and shoes 7. Shear sheep 8. prosthesis 9. Cook fast food and work in other service industries 10. Household robot.

Generally such predictions are overly optimistic in timescale.

New functionalities and prototypes

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (August 2021) |

In 2008, Caterpillar Inc. developed a dump truck which can drive itself without any human operator.[66] Many analysts believe that self-driving trucks may eventually revolutionize logistics.[67] By 2014, Caterpillar had a self-driving dump truck which is expected to greatly change the process of mining. In 2015, these Caterpillar trucks were actively used in mining operations in Australia by the mining company Rio Tinto Coal Australia.[68][69][70][71] Some analysts believe that within the next few decades, most trucks will be self-driving.[72]

A literate or ‘reading robot’ named Marge has intelligence that comes from software. She can read newspapers, find and correct misspelled words, learn about banks like Barclays, and understand that some restaurants are better places to eat than others.[73]

Baxter is a new robot introduced in 2012 which learns by guidance. A worker could teach Baxter how to perform a task by moving its hands in the desired motion and having Baxter memorize them. Extra dials, buttons, and controls are available on Baxter’s arm for more precision and features. Any regular worker could program Baxter and it only takes a matter of minutes, unlike usual industrial robots that take extensive programs and coding to be used. This means Baxter needs no programming to operate. No software engineers are needed. This also means Baxter can be taught to perform multiple, more complicated tasks. Sawyer was added in 2015 for smaller, more precise tasks.[74]

Prototype cooking robots have been developed and could be programmed for autonomous, dynamic and adjustable preparation of discrete meals.[75][76]

Etymology

The word robot was introduced to the public by the Czech interwar writer Karel Čapek in his play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), published in 1920.[6] The play begins in a factory that uses a chemical substitute for protoplasm to manufacture living, simplified people called robots. The play does not focus in detail on the technology behind the creation of these living creatures, but in their appearance they prefigure modern ideas of androids, creatures who can be mistaken for humans. These mass-produced workers are depicted as efficient but emotionless, incapable of original thinking and indifferent to self-preservation. At issue is whether the robots are being exploited and the consequences of human dependence upon commodified labor (especially after a number of specially-formulated robots achieve self-awareness and incite robots all around the world to rise up against the humans).

Karel Čapek himself did not coin the word. He wrote a short letter in reference to an etymology in the Oxford English Dictionary in which he named his brother, the painter and writer Josef Čapek, as its actual originator.[6]

In an article in the Czech journal Lidové noviny in 1933, he explained that he had originally wanted to call the creatures laboři («workers», from Latin labor). However, he did not like the word, and sought advice from his brother Josef, who suggested «roboti». The word robota means literally «corvée», «serf labor», and figuratively «drudgery» or «hard work» in Czech and also (more general) «work», «labor» in many Slavic languages (e.g.: Bulgarian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak, Polish, Macedonian, Ukrainian, archaic Czech, as well as robot in Hungarian). Traditionally the robota (Hungarian robot) was the work period a serf (corvée) had to give for his lord, typically 6 months of the year. The origin of the word is the Old Church Slavonic rabota «servitude» («work» in contemporary Bulgarian, Macedonian and Russian), which in turn comes from the Proto-Indo-European root *orbh-. Robot is cognate with the German root Arbeit (work).[77][78]

English pronunciation of the word has evolved relatively quickly since its introduction. In the U.S. during the late ’30s to early ’40s the second syllable was pronounced with a long «O» like «row-boat.»[79][better source needed] By the late ’50s to early ’60s, some were pronouncing it with a short «U» like «row-but» while others used a softer «O» like «row-bought.»[80] By the ’70s, its current pronunciation «row-bot» had become predominant.

The word robotics, used to describe this field of study,[4] was coined by the science fiction writer Isaac Asimov. Asimov created the «Three Laws of Robotics» which are a recurring theme in his books. These have since been used by many others to define laws used in fiction. (The three laws are pure fiction, and no technology yet created has the ability to understand or follow them, and in fact most robots serve military purposes, which run quite contrary to the first law and often the third law. «People think about Asimov’s laws, but they were set up to point out how a simple ethical system doesn’t work. If you read the short stories, every single one is about a failure, and they are totally impractical,» said Dr. Joanna Bryson of the University of Bath.[81])

Modern robots

Mobile robot

Mobile robots[82] have the capability to move around in their environment and are not fixed to one physical location. An example of a mobile robot that is in common use today is the automated guided vehicle or automatic guided vehicle (AGV). An AGV is a mobile robot that follows markers or wires in the floor, or uses vision or lasers.[83] AGVs are discussed later in this article.

Mobile robots are also found in industry, military and security environments.[84] They also appear as consumer products, for entertainment or to perform certain tasks like vacuum cleaning. Mobile robots are the focus of a great deal of current research and almost every major university has one or more labs that focus on mobile robot research.[85]

Mobile robots are usually used in tightly controlled environments such as on assembly lines because they have difficulty responding to unexpected interference. Because of this most humans rarely encounter robots. However domestic robots for cleaning and maintenance are increasingly common in and around homes in developed countries. Robots can also be found in military applications.[86]

Industrial robots (manipulating)

A pick and place robot in a factory

Industrial robots usually consist of a jointed arm (multi-linked manipulator) and an end effector that is attached to a fixed surface. One of the most common type of end effector is a gripper assembly.

The International Organization for Standardization gives a definition of a manipulating industrial robot in ISO 8373:

«an automatically controlled, reprogrammable, multipurpose, manipulator programmable in three or more axes, which may be either fixed in place or mobile for use in industrial automation applications.»[87]

This definition is used by the International Federation of Robotics, the European Robotics Research Network (EURON) and many national standards committees.[88]

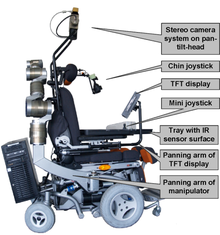

Service robot

Most commonly industrial robots are fixed robotic arms and manipulators used primarily for production and distribution of goods. The term «service robot» is less well-defined. The International Federation of Robotics has proposed a tentative definition, «A service robot is a robot which operates semi- or fully autonomously to perform services useful to the well-being of humans and equipment, excluding manufacturing operations.»[89]

Educational (interactive) robots

Robots are used as educational assistants to teachers. From the 1980s, robots such as turtles were used in schools and programmed using the Logo language.[90][91]

There are robot kits like Lego Mindstorms, BIOLOID, OLLO from ROBOTIS, or BotBrain Educational Robots can help children to learn about mathematics, physics, programming, and electronics. Robotics have also been introduced into the lives of elementary and high school students in the form of robot competitions with the company FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology). The organization is the foundation for the FIRST Robotics Competition, FIRST Tech Challenge, FIRST Lego League Challenge and FIRST Lego League Explore competitions.

There have also been robots such as the teaching computer, Leachim (1974).[92] Leachim was an early example of speech synthesis using the using the Diphone synthesis method. 2-XL (1976) was a robot shaped game / teaching toy based on branching between audible tracks on an 8-track tape player, both invented by Michael J. Freeman.[93] Later, the 8-track was upgraded to tape cassettes and then to digital.

Modular robot

Modular robots are a new breed of robots that are designed to increase the use of robots by modularizing their architecture.[94] The functionality and effectiveness of a modular robot is easier to increase compared to conventional robots. These robots are composed of a single type of identical, several different identical module types, or similarly shaped modules, which vary in size. Their architectural structure allows hyper-redundancy for modular robots, as they can be designed with more than 8 degrees of freedom (DOF). Creating the programming, inverse kinematics and dynamics for modular robots is more complex than with traditional robots. Modular robots may be composed of L-shaped modules, cubic modules, and U and H-shaped modules. ANAT technology, an early modular robotic technology patented by Robotics Design Inc., allows the creation of modular robots from U and H shaped modules that connect in a chain, and are used to form heterogeneous and homogenous modular robot systems. These «ANAT robots» can be designed with «n» DOF as each module is a complete motorized robotic system that folds relatively to the modules connected before and after it in its chain, and therefore a single module allows one degree of freedom. The more modules that are connected to one another, the more degrees of freedom it will have. L-shaped modules can also be designed in a chain, and must become increasingly smaller as the size of the chain increases, as payloads attached to the end of the chain place a greater strain on modules that are further from the base. ANAT H-shaped modules do not suffer from this problem, as their design allows a modular robot to distribute pressure and impacts evenly amongst other attached modules, and therefore payload-carrying capacity does not decrease as the length of the arm increases. Modular robots can be manually or self-reconfigured to form a different robot, that may perform different applications. Because modular robots of the same architecture type are composed of modules that compose different modular robots, a snake-arm robot can combine with another to form a dual or quadra-arm robot, or can split into several mobile robots, and mobile robots can split into multiple smaller ones, or combine with others into a larger or different one. This allows a single modular robot the ability to be fully specialized in a single task, as well as the capacity to be specialized to perform multiple different tasks.

Modular robotic technology is currently being applied in hybrid transportation,[95] industrial automation,[96] duct cleaning[97] and handling. Many research centres and universities have also studied this technology, and have developed prototypes.

Collaborative robots

A collaborative robot or cobot is a robot that can safely and effectively interact with human workers while performing simple industrial tasks. However, end-effectors and other environmental conditions may create hazards, and as such risk assessments should be done before using any industrial motion-control application.[98]

The collaborative robots most widely used in industries today are manufactured by Universal Robots in Denmark.[99]

Rethink Robotics—founded by Rodney Brooks, previously with iRobot—introduced Baxter in September 2012; as an industrial robot designed to safely interact with neighboring human workers, and be programmable for performing simple tasks.[100] Baxters stop if they detect a human in the way of their robotic arms and have prominent off switches. Intended for sale to small businesses, they are promoted as the robotic analogue of the personal computer.[101] As of May 2014, 190 companies in the US have bought Baxters and they are being used commercially in the UK.[10]

Robots in society

Roughly half of all the robots in the world are in Asia, 32% in Europe, and 16% in North America, 1% in Australasia and 1% in Africa.[104] 40% of all the robots in the world are in Japan,[105] making Japan the country with the highest number of robots.

Autonomy and ethical questions

An android, or robot designed to resemble a human, can appear comforting to some people and disturbing to others.[106]

As robots have become more advanced and sophisticated, experts and academics have increasingly explored the questions of what ethics might govern robots’ behavior,[107][108] and whether robots might be able to claim any kind of social, cultural, ethical or legal rights.[109] One scientific team has said that it was possible that a robot brain would exist by 2019.[110] Others predict robot intelligence breakthroughs by 2050.[111] Recent advances have made robotic behavior more sophisticated.[112] The social impact of intelligent robots is subject of a 2010 documentary film called Plug & Pray.[113]

Vernor Vinge has suggested that a moment may come when computers and robots are smarter than humans. He calls this «the Singularity».[114] He suggests that it may be somewhat or possibly very dangerous for humans.[115] This is discussed by a philosophy called Singularitarianism.

In 2009, experts attended a conference hosted by the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI) to discuss whether computers and robots might be able to acquire any autonomy, and how much these abilities might pose a threat or hazard. They noted that some robots have acquired various forms of semi-autonomy, including being able to find power sources on their own and being able to independently choose targets to attack with weapons. They also noted that some computer viruses can evade elimination and have achieved «cockroach intelligence.» They noted that self-awareness as depicted in science-fiction is probably unlikely, but that there were other potential hazards and pitfalls.[114] Various media sources and scientific groups have noted separate trends in differing areas which might together result in greater robotic functionalities and autonomy, and which pose some inherent concerns.[116][117][118]

Military robots

Some experts and academics have questioned the use of robots for military combat, especially when such robots are given some degree of autonomous functions.[119] There are also concerns about technology which might allow some armed robots to be controlled mainly by other robots.[120] The US Navy has funded a report which indicates that, as military robots become more complex, there should be greater attention to implications of their ability to make autonomous decisions.[121][122] One researcher states that autonomous robots might be more humane, as they could make decisions more effectively. However, other experts question this.[123]

One robot in particular, the EATR, has generated public concerns[124] over its fuel source, as it can continually refuel itself using organic substances.[125] Although the engine for the EATR is designed to run on biomass and vegetation[126] specifically selected by its sensors, which it can find on battlefields or other local environments, the project has stated that chicken fat can also be used.[127]

Manuel De Landa has noted that «smart missiles» and autonomous bombs equipped with artificial perception can be considered robots, as they make some of their decisions autonomously. He believes this represents an important and dangerous trend in which humans are handing over important decisions to machines.[128]

Relationship to unemployment

For centuries, people have predicted that machines would make workers obsolete and increase unemployment, although the causes of unemployment are usually thought to be due to social policy.[129][130][131]

A recent example of human replacement involves Taiwanese technology company Foxconn who, in July 2011, announced a three-year plan to replace workers with more robots. At present the company uses ten thousand robots but will increase them to a million robots over a three-year period.[132]

Lawyers have speculated that an increased prevalence of robots in the workplace could lead to the need to improve redundancy laws.[133]

Kevin J. Delaney said «Robots are taking human jobs. But Bill Gates believes that governments should tax companies’ use of them, as a way to at least temporarily slow the spread of automation and to fund other types of employment.»[134] The robot tax would also help pay a guaranteed living wage to the displaced workers.

The World Bank’s World Development Report 2019 puts forth evidence showing that while automation displaces workers, technological innovation creates more new industries and jobs on balance.[135]

Contemporary uses

A general-purpose robot acts as a guide during the day and a security guard at night.

At present, there are two main types of robots, based on their use: general-purpose autonomous robots and dedicated robots.

Robots can be classified by their specificity of purpose. A robot might be designed to perform one particular task extremely well, or a range of tasks less well. All robots by their nature can be re-programmed to behave differently, but some are limited by their physical form. For example, a factory robot arm can perform jobs such as cutting, welding, gluing, or acting as a fairground ride, while a pick-and-place robot can only populate printed circuit boards.

General-purpose autonomous robots