A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence.[1][2] Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized, but not defined, by formalism, traditionalism, invariance, rule-governance, sacral symbolism, and performance.[3]

Rituals are a feature of all known human societies.[4] They include not only the worship rites and sacraments of organized religions and cults, but also rites of passage, atonement and purification rites, oaths of allegiance, dedication ceremonies, coronations and presidential inaugurations, marriages, funerals and more. Even common actions like hand-shaking and saying «hello» may be termed as rituals.

The field of ritual studies has seen a number of conflicting definitions of the term. One given by Kyriakidis is that a ritual is an outsider’s or «etic» category for a set activity (or set of actions) that, to the outsider, seems irrational, non-contiguous, or illogical. The term can be used also by the insider or «emic» performer as an acknowledgement that this activity can be seen as such by the uninitiated onlooker.[5]

In psychology, the term ritual is sometimes used in a technical sense for a repetitive behavior systematically used by a person to neutralize or prevent anxiety; it can be a symptom of obsessive–compulsive disorder but obsessive-compulsive ritualistic behaviors are generally isolated activities.

Etymology[edit]

The English word ritual derives from the Latin ritualis, «that which pertains to rite (ritus)». In Roman juridical and religious usage, ritus was the proven way (mos) of doing something,[6] or «correct performance, custom».[7] The original concept of ritus may be related to the Sanskrit ṛtá («visible order)» in Vedic religion, «the lawful and regular order of the normal, and therefore proper, natural and true structure of cosmic, worldly, human and ritual events».[8] The word «ritual» is first recorded in English in 1570, and came into use in the 1600s to mean «the prescribed order of performing religious services» or more particularly a book of these prescriptions.[9]

Characteristics[edit]

There are hardly any limits to the kind of actions that may be incorporated into a ritual. The rites of past and present societies have typically involved special gestures and words, recitation of fixed texts, performance of special music, songs or dances, processions, manipulation of certain objects, use of special dresses, consumption of special food, drink, or drugs, and much more.[10][11][12]

Catherine Bell argues that rituals can be characterized by formalism, traditionalism, invariance, rule-governance, sacral symbolism and performance.[13]

Formalism[edit]

Ritual uses a limited and rigidly organized set of expressions which anthropologists call a «restricted code» (in opposition to a more open «elaborated code»). Maurice Bloch argues that ritual obliges participants to use this formal oratorical style, which is limited in intonation, syntax, vocabulary, loudness, and fixity of order. In adopting this style, ritual leaders’ speech becomes more style than content. Because this formal speech limits what can be said, it induces «acceptance, compliance, or at least forbearance with regard to any overt challenge». Bloch argues that this form of ritual communication makes rebellion impossible and revolution the only feasible alternative. Ritual tends to support traditional forms of social hierarchy and authority, and maintains the assumptions on which the authority is based from challenge.[14]

Traditionalism[edit]

The First Thanksgiving 1621, oil on canvas by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (1863–1930). The painting shows common misconceptions about the event that persist to modern times: Pilgrims did not wear such outfits, and the Wampanoag are dressed in the style of Plains Indians.[15]

Rituals appeal to tradition and are generally continued to repeat historical precedent, religious rite, mores, or ceremony accurately. Traditionalism varies from formalism in that the ritual may not be formal yet still makes an appeal to the historical trend. An example is the American Thanksgiving dinner, which may not be formal, yet is ostensibly based on an event from the early Puritan settlement of America. Historians Eric Hobsbawm and Terrence Ranger have argued that many of these are invented traditions, such as the rituals of the British monarchy, which invoke «thousand year-old tradition» but whose actual form originate in the late nineteenth century, to some extent reviving earlier forms, in this case medieval, that had been discontinued in the meantime. Thus, the appeal to history is important rather than accurate historical transmission.[16]

Invariance[edit]

Catherine Bell states that ritual is also invariant, implying careful choreography. This is less an appeal to traditionalism than a striving for timeless repetition. The key to invariance is bodily discipline, as in monastic prayer and meditation meant to mold dispositions and moods. This bodily discipline is frequently performed in unison, by groups.[17]

Rule-governance[edit]

Rituals tend to be governed by rules, a feature somewhat like formalism. Rules impose norms on the chaos of behavior, either defining the outer limits of what is acceptable or choreographing each move. Individuals are held to communally approved customs that evoke a legitimate communal authority that can constrain the possible outcomes. Historically, war in most societies has been bound by highly ritualized constraints that limit the legitimate means by which war was waged.[18]

Sacral symbolism[edit]

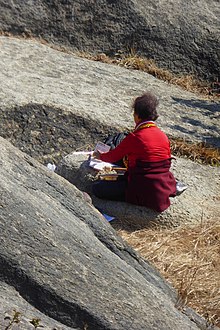

Ritual practitioner on Inwangsan Mountain, Seoul South Korea

Activities appealing to supernatural beings are easily considered rituals, although the appeal may be quite indirect, expressing only a generalized belief in the existence of the sacred demanding a human response. National flags, for example, may be considered more than signs representing a country. The flag stands for larger symbols such as freedom, democracy, free enterprise or national superiority.[19] Anthropologist Sherry Ortner writes that the flag

does not encourage reflection on the logical relations among these ideas, nor on the logical consequences of them as they are played out in social actuality, over time and history. On the contrary, the flag encourages a sort of all-or-nothing allegiance to the whole package, best summed [by] ‘Our flag, love it or leave.’[20]

Particular objects become sacral symbols through a process of consecration which effectively creates the sacred by setting it apart from the profane. Boy Scouts and the armed forces in any country teach the official ways of folding, saluting and raising the flag, thus emphasizing that the flag should never be treated as just a piece of cloth.[21]

Performance[edit]

The performance of ritual creates a theatrical-like frame around the activities, symbols and events that shape participant’s experience and cognitive ordering of the world, simplifying the chaos of life and imposing a more or less coherent system of categories of meaning onto it.[22] As Barbara Myerhoff put it, «not only is seeing believing, doing is believing.»[23]

Genres[edit]

For simplicity’s sake, the range of diverse rituals can be divided into categories with common characteristics, generally falling into one three major categories:

- rites of passage, generally changing an individual’s social status;

- communal rites, whether of worship, where a community comes together to worship, such as Jewish synagogue or Mass, or of another character, such as fertility rites and certain non-religious festivals;

- rites of personal devotion, where an individual worships, including prayer and pilgrimages, pledges of allegiance, or promises to wed someone.

However, rituals can fall in more than one category or genre, and may be grouped in a variety of other ways. For example, the anthropologist Victor Turner writes:

Rituals may be seasonal, … or they may be contingent, held in response to an individual or collective crisis. … Other classes of rituals include divinatory rituals; ceremonies performed by political authorities to ensure the health and fertility of human beings, animals, and crops in their territories; initiation into priesthoods devoted to certain deities, into religious associations, or into secret societies; and those accompanying the daily offering of food and libations to deities or ancestral spirits or both.

Rites of passage[edit]

A rite of passage is a ritual event that marks a person’s transition from one status to another, including adoption, baptism, coming of age, graduation, inauguration, engagement, and marriage. Rites of passage may also include initiation into groups not tied to a formal stage of life such as a fraternity. Arnold van Gennep stated that rites of passage are marked by three stages:[24]

- 1. Separation

- Wherein the initiates are separated from their old identities through physical and symbolic means.

- 2. Transition

- Wherein the initiated are «betwixt and between». Victor Turner argued that this stage is marked by liminality, a condition of ambiguity or disorientation in which initiates have been stripped of their old identities, but have not yet acquired their new one. Turner states that «the attributes of liminality or of liminal personae («threshold people») are necessarily ambiguous».[25] In this stage of liminality or «anti-structure» (see below), the initiates’ role ambiguity creates a sense of communitas or emotional bond of community between them. This stage may be marked by ritual ordeals or ritual training.

- 3. Incorporation

- Wherein the initiates are symbolically confirmed in their new identity and community.[26]

Rites of affliction[edit]

Anthropologist Victor Turner defines rites of affliction actions that seek to mitigate spirits or supernatural forces that inflict humans with bad luck, illness, gynecological troubles, physical injuries, and other such misfortunes.[27] These rites may include forms of spirit divination (consulting oracles) to establish causes—and rituals that heal, purify, exorcise, and protect. The misfortune experienced may include individual health, but also broader climate-related issues such as drought or plagues of insects. Healing rites performed by shamans frequently identify social disorder as the cause, and make the restoration of social relationships the cure.[28]

Turner uses the example of the Isoma ritual among the Ndembu of northwestern Zambia to illustrate. The Isoma rite of affliction is used to cure a childless woman of infertility. Infertility is the result of a «structural tension between matrilineal descent and virilocal marriage» (i.e., the tension a woman feels between her mother’s family, to whom she owes allegiance, and her husband’s family among whom she must live). «It is because the woman has come too closely in touch with the ‘man’s side’ in her marriage that her dead matrikin have impaired her fertility.» To correct the balance of matrilinial descent and marriage, the Isoma ritual dramatically placates the deceased spirits by requiring the woman to reside with her mother’s kin.[29]

Shamanic and other ritual may effect a psychotherapeutic cure, leading anthropologists such as Jane Atkinson to theorize how. Atkinson argues that the effectiveness of a shamanic ritual for an individual may depend upon a wider audiences acknowledging the shaman’s power, which may lead to the shaman placing greater emphasis on engaging the audience than in the healing of the patient.[30]

Death, mourning, and funerary rites[edit]

|

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2022) |

Many cultures have rites associated with death and mourning, such as the last rites and wake in Christianity, shemira in Judaism, the antyesti in Hinduism, and the antam sanskar in Sikhism.

Calendrical and commemorative rites[edit]

Calendrical and commemorative rites are ritual events marking particular times of year, or a fixed period since an important event. Calendrical rituals give social meaning to the passage of time, creating repetitive weekly, monthly or yearly cycles. Some rites are oriented towards a culturally defined moment of change in the climatic cycle, such as solar terms or the changing of seasons, or they may mark the inauguration of an activity such as planting, harvesting, or moving from winter to summer pasture during the agricultural cycle.[27] They may be fixed by the solar or lunar calendar; those fixed by the solar calendar fall on the same day (of the Gregorian, Solar calendar) each year (such as New Year’s Day on the first of January) while those calculated by the lunar calendar fall on different dates (of the Gregorian, Solar calendar) each year (such as Chinese lunar New Year). Calendrical rites impose a cultural order on nature.[31] Mircea Eliade states that the calendrical rituals of many religious traditions recall and commemorate the basic beliefs of a community, and their yearly celebration establishes a link between past and present, as if the original events are happening over again: «Thus the gods did; thus men do.»[32]

Rites of sacrifice, exchange, and communion[edit]

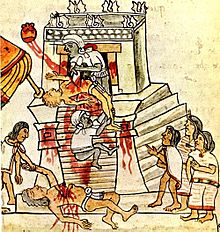

This genre of ritual encompasses forms of sacrifice and offering meant to praise, please or placate divine powers. According to early anthropologist Edward Tylor, such sacrifices are gifts given in hope of a return. Catherine Bell, however, points out that sacrifice covers a range of practices from those that are manipulative and «magical» to those of pure devotion. Hindu puja, for example, appear to have no other purpose than to please the deity.[33]

According to Marcel Mauss, sacrifice is distinguished from other forms of offering by being consecrated, and hence sanctified. As a consequence, the offering is usually destroyed in the ritual to transfer it to the deities.

Rites of feasting, fasting, and festivals[edit]

Rites of feasting and fasting are those through which a community publicly expresses an adherence to basic, shared religious values, rather than to the overt presence of deities as is found in rites of affliction where feasting or fasting may also take place. It encompasses a range of performances such as communal fasting during Ramadan by Muslims; the slaughter of pigs in New Guinea; Carnival festivities; or penitential processions in Catholicism.[34] Victor Turner described this «cultural performance» of basic values a «social drama». Such dramas allow the social stresses that are inherent in a particular culture to be expressed and worked out symbolically in a ritual catharsis; as the social tensions continue to persist outside the ritual, pressure mounts for the ritual’s cyclical performance.[35] In Carnival, for example, the practice of masking allows people to be what they are not, and acts as a general social leveller, erasing otherwise tense social hierarchies in a festival that emphasizes play outside the bounds of normal social limits. Yet outside carnival, social tensions of race, class and gender persist, hence requiring the repeated periodic release found in the festival.[36]

Water rites[edit]

A water rite is a rite or ceremonial custom that uses water as its central feature. Typically, a person is immersed or bathed as a symbol of religious indoctrination or ritual purification. Examples include the Mikveh in Judaism, a custom of purification; misogi in Shinto, a custom of spiritual and bodily purification involving bathing in a sacred waterfall, river, or lake; baptism in Christianity, a custom and sacrament that represents both purification and initiation into the religious community (the Christian Church); and Amrit Sanskar in Sikhism, a rite of passage (sanskar) that similarly represents purification and initiation into the religious community (the khalsa). Rites that use water, but not as their central feature, for example, that include drinking water, are not considered water rites.

Fertility rites[edit]

Fertility rites or fertility cult are religious rituals that are intended to stimulate reproduction in humans or in the natural world.[37] Such rites may involve the sacrifice of «a primal animal, which must be sacrificed in the cause of fertility or even creation».[38]

Sexual rituals[edit]

Political rituals[edit]

Parade through Macao, Latin City (2019). The Parade is held annually on December 20th to mark the anniversary of Macao’s Handover to China.

According to anthropologist Clifford Geertz, political rituals actually construct power; that is, in his analysis of the Balinese state, he argued that rituals are not an ornament of political power, but that the power of political actors depends upon their ability to create rituals and the cosmic framework within which the social hierarchy headed by the king is perceived as natural and sacred.[40] As a «dramaturgy of power» comprehensive ritual systems may create a cosmological order that sets a ruler apart as a divine being, as in «the divine right» of European kings, or the divine Japanese Emperor.[41] Political rituals also emerge in the form of uncodified or codified conventions practiced by political officials that cement respect for the arrangements of an institution or role against the individual temporarily assuming it, as can be seen in the many rituals still observed within the procedure of parliamentary bodies.

Ritual can be used as a form of resistance, as for example, in the various Cargo Cults that developed against colonial powers in the South Pacific. In such religio-political movements, Islanders would use ritual imitations of western practices (such as the building of landing strips) as a means of summoning cargo (manufactured goods) from the ancestors. Leaders of these groups characterized the present state (often imposed by colonial capitalist regimes) as a dismantling of the old social order, which they sought to restore.[42]

Anthropological theories[edit]

Functionalism[edit]

Nineteenth century «armchair anthropologists» were concerned with the basic question of how religion originated in human history. In the twentieth century their conjectural histories were replaced with new concerns around the question of what these beliefs and practices did for societies, regardless of their origin. In this view, religion was a universal, and while its content might vary enormously, it served certain basic functions such as the provision of prescribed solutions to basic human psychological and social problems, as well as expressing the central values of a society. Bronislaw Malinowski used the concept of function to address questions of individual psychological needs; A.R. Radcliffe-Brown, in contrast, looked for the function (purpose) of the institution or custom in preserving or maintaining society as a whole. They thus disagreed about the relationship of anxiety to ritual.[43]

Kowtowing in a court, China, before 1889

Malinowski argued that ritual was a non-technical means of addressing anxiety about activities where dangerous elements were beyond technical control: «magic is to be expected and generally to be found whenever man comes to an unbridgeable gap, a hiatus in his knowledge or in his powers of practical control, and yet has to continue in his pursuit.».[44] Radcliffe-Brown in contrast, saw ritual as an expression of common interest symbolically representing a community, and that anxiety was felt only if the ritual was not performed.[43] George C. Homans sought to resolve these opposing theories by differentiating between «primary anxieties» felt by people who lack the techniques to secure results, and «secondary (or displaced) anxiety» felt by those who have not performed the rites meant to allay primary anxiety correctly. Homans argued that purification rituals may then be conducted to dispel secondary anxiety.[45]

A.R. Radcliffe-Brown argued that ritual should be distinguished from technical action, viewing it as a structured event: «ritual acts differ from technical acts in having in all instances some expressive or symbolic element in them.»[46] Edmund Leach, in contrast, saw ritual and technical action less as separate structural types of activity and more as a spectrum: «Actions fall into place on a continuous scale. At one extreme we have actions which are entirely profane, entirely functional, technique pure and simple; at the other we have actions which are entirely sacred, strictly aesthetic, technically non-functional. Between these two extremes we have the great majority of social actions which partake partly of the one sphere and partly of the other. From this point of view technique and ritual, profane and sacred, do not denote types of action but aspects of almost any kind of action.»[47]

[edit]

Balinese rice terraces regulated through ritual

The functionalist model viewed ritual as a homeostatic mechanism to regulate and stabilize social institutions by adjusting social interactions, maintaining a group ethos, and restoring harmony after disputes.

Although the functionalist model was soon superseded, later «neofunctional» theorists adopted its approach by examining the ways that ritual regulated larger ecological systems. Roy Rappaport, for example, examined the way gift exchanges of pigs between tribal groups in Papua New Guinea maintained environmental balance between humans, available food (with pigs sharing the same foodstuffs as humans) and resource base. Rappaport concluded that ritual, «…helps to maintain an undegraded environment, limits fighting to frequencies which do not endanger the existence of regional population, adjusts man-land ratios, facilitates trade, distributes local surpluses of pig throughout the regional population in the form of pork, and assures people of high quality protein when they are most in need of it».[48] Similarly, J. Stephen Lansing traced how the intricate calendar of Hindu Balinese rituals served to regulate the vast irrigation systems of Bali, ensuring the optimum distribution of water over the system while limiting disputes.[49]

Rebellion[edit]

While most Functionalists sought to link ritual to the maintenance of social order, South African functionalist anthropologist Max Gluckman coined the phrase «rituals of rebellion» to describe a type of ritual in which the accepted social order was symbolically turned on its head. Gluckman argued that the ritual was an expression of underlying social tensions (an idea taken up by Victor Turner), and that it functioned as an institutional pressure valve, relieving those tensions through these cyclical performances. The rites ultimately functioned to reinforce social order, insofar as they allowed those tensions to be expressed without leading to actual rebellion. Carnival is viewed in the same light. He observed, for example, how the first-fruits festival (incwala) of the South African Bantu kingdom of Swaziland symbolically inverted the normal social order, so that the king was publicly insulted, women asserted their domination over men, and the established authority of elders over the young was turned upside down.[50]

Structuralism[edit]

Claude Lévi-Strauss, the French anthropologist, regarded all social and cultural organization as symbolic systems of communication shaped by the inherent structure of the human brain. He therefore argued that the symbol systems are not reflections of social structure as the Functionalists believed, but are imposed on social relations to organize them. Lévi-Strauss thus viewed myth and ritual as complementary symbol systems, one verbal, one non-verbal. Lévi-Strauss was not concerned to develop a theory of ritual (although he did produce a four-volume analysis of myth) but was influential to later scholars of ritual such as Mary Douglas and Edmund Leach.[51]

Structure and anti-structure[edit]

Victor Turner combined Arnold van Gennep’s model of the structure of initiation rites, and Gluckman’s functionalist emphasis on the ritualization of social conflict to maintain social equilibrium, with a more structural model of symbols in ritual. Running counter to this emphasis on structured symbolic oppositions within a ritual was his exploration of the liminal phase of rites of passage, a phase in which «anti-structure» appears. In this phase, opposed states such as birth and death may be encompassed by a single act, object or phrase. The dynamic nature of symbols experienced in ritual provides a compelling personal experience; ritual is a «mechanism that periodically converts the obligatory into the desirable».[52]

Mary Douglas, a British Functionalist, extended Turner’s theory of ritual structure and anti-structure with her own contrasting set of terms «grid» and «group» in the book Natural Symbols. Drawing on Levi-Strauss’ Structuralist approach, she saw ritual as symbolic communication that constrained social behaviour. Grid is a scale referring to the degree to which a symbolic system is a shared frame of reference. Group refers to the degree people are tied into a tightly knit community. When graphed on two intersecting axes, four quadrants are possible: strong group/strong grid, strong group/weak grid, weak group/weak grid, weak group/strong grid. Douglas argued that societies with strong group or strong grid were marked by more ritual activity than those weak in either group or grid.[53] (see also, section below)

Anti-structure and communitas[edit]

In his analysis of rites of passage, Victor Turner argued that the liminal phase — that period ‘betwixt and between’ — was marked by «two models of human interrelatedness, juxtaposed and alternating»: structure and anti-structure (or communitas).[54] While the ritual clearly articulated the cultural ideals of a society through ritual symbolism, the unrestrained festivities of the liminal period served to break down social barriers and to join the group into an undifferentiated unity with «no status, property, insignia, secular clothing, rank, kinship position, nothing to demarcate themselves from their fellows».[55] These periods of symbolic inversion have been studied in a diverse range of rituals such as pilgrimages and Yom Kippur.[56]

[edit]

Beginning with Max Gluckman’s concept of «rituals of rebellion», Victor Turner argued that many types of ritual also served as «social dramas» through which structural social tensions could be expressed, and temporarily resolved. Drawing on Van Gennep’s model of initiation rites, Turner viewed these social dramas as a dynamic process through which the community renewed itself through the ritual creation of communitas during the «liminal phase». Turner analyzed the ritual events in 4 stages: breach in relations, crisis, redressive actions, and acts of reintegration. Like Gluckman, he argued these rituals maintain social order while facilitating disordered inversions, thereby moving people to a new status, just as in an initiation rite.[57]

Symbolic approaches to ritual[edit]

Arguments, melodies, formulas, maps and pictures are not idealities to be stared at but texts to be read; so are rituals, palaces, technologies, and social formations.

Clifford Geertz also expanded on the symbolic approach to ritual that began with Victor Turner. Geertz argued that religious symbol systems provided both a «model of» reality (showing how to interpret the world as is) as well as a «model for» reality (clarifying its ideal state). The role of ritual, according to Geertz, is to bring these two aspects – the «model of» and the «model for» – together: «it is in ritual – that is consecrated behaviour – that this conviction that religious conceptions are veridical and that religious directives are sound is somehow generated.»[58]

Symbolic anthropologists like Geertz analyzed rituals as language-like codes to be interpreted independently as cultural systems. Geertz rejected Functionalist arguments that ritual describes social order, arguing instead that ritual actively shapes that social order and imposes meaning on disordered experience. He also differed from Gluckman and Turner’s emphasis on ritual action as a means of resolving social passion, arguing instead that it simply displayed them.[59]

As a form of communication[edit]

Whereas Victor Turner saw in ritual the potential to release people from the binding structures of their lives into a liberating anti-structure or communitas, Maurice Bloch argued that ritual produced conformity.[60]

Maurice Bloch argued that ritual communication is unusual in that it uses a special, restricted vocabulary, a small number of permissible illustrations, and a restrictive grammar. As a result, ritual utterances become very predictable, and the speaker is made anonymous in that they have little choice in what to say. The restrictive syntax reduces the ability of the speaker to make propositional arguments, and they are left, instead, with utterances that cannot be contradicted such as «I do thee wed» in a wedding. These kinds of utterances, known as performatives, prevent speakers from making political arguments through logical argument, and are typical of what Weber called traditional authority instead.[61]

Bloch’s model of ritual language denies the possibility of creativity. Thomas Csordas, in contrast, analyzes how ritual language can be used to innovate. Csordas looks at groups of rituals that share performative elements («genres» of ritual with a shared «poetics»). These rituals may fall along the spectrum of formality, with some less, others more formal and restrictive. Csordas argues that innovations may be introduced in less formalized rituals. As these innovations become more accepted and standardized, they are slowly adopted in more formal rituals. In this way, even the most formal of rituals are potential avenues for creative expression.[62]

As a disciplinary program[edit]

Scriptorium-monk-at-work. «Monks described this labor of transcribing manuscripts as being ‘like prayer and fasting, a means of correcting one’s unruly passions.'»[63]

In his historical analysis of articles on ritual and rite in the Encyclopædia Britannica, Talal Asad notes that from 1771 to 1852, the brief articles on ritual define it as a «book directing the order and manner to be observed in performing divine service» (i.e., as a script). There are no articles on the subject thereafter until 1910, when a new, lengthy article appeared that redefines ritual as «…a type of routine behaviour that symbolizes or expresses something».[64] As a symbolic activity, it is no longer confined to religion, but is distinguished from technical action. The shift in definitions from script to behavior, which is likened to a text, is matched by a semantic distinction between ritual as an outward sign (i.e., public symbol) and inward meaning.[65]

The emphasis has changed to establishing the meaning of public symbols and abandoning concerns with inner emotional states since, as Evans-Pritchard wrote «such emotional states, if present at all, must vary not only from individual to individual, but also in the same individual on different occasions and even at different points in the same rite.»[66] Asad, in contrast, emphasizes behavior and inner emotional states; rituals are to be performed, and mastering these performances is a skill requiring disciplined action.

In other words, apt performance involves not symbols to be interpreted but abilities to be acquired according to rules that are sanctioned by those in authority: it presupposes no obscure meanings, but rather the formation of physical and linguistic skills.

— Asad (1993), p. 62

Drawing on the example of Medieval monastic life in Europe, he points out that ritual in this case refers to its original meaning of the «…book directing the order and manner to be observed in performing divine service». This book «prescribed practices, whether they had to do with the proper ways of eating, sleeping, working, and praying or with proper moral dispositions and spiritual aptitudes, aimed at developing virtues that are put ‘to the service of God.'»[67] Monks, in other words, were disciplined in the Foucauldian sense. The point of monastic discipline was to learn skills and appropriate emotions. Asad contrasts his approach by concluding:

Symbols call for interpretation, and even as interpretive criteria are extended so interpretations can be multiplied. Disciplinary practices, on the other hand, cannot be varied so easily, because learning to develop moral capabilities is not the same thing as learning to invent representations.

— Asad (1993), p. 79

[edit]

Ethnographic observation shows ritual can create social solidarity. Douglas Foley Went to North Town, Texas, between 1973 and 1974 to study public high school culture. He used interviews, participant observation, and unstructured chatting to study racial tension and capitalist culture in his ethnography Learning Capitalist Culture. Foley refers to football games and Friday Night Lights as a community ritual. This ritual united the school and created a sense of solidarity and community on a weekly basis involving pep rallies and the game itself. Foley observed judgement and segregation based on class, social status, wealth, and gender. He described Friday Night Lights as a ritual that overcomes those differences: «The other, gentler, more social side of football was, of course, the emphasis on camaraderie, loyalty, friendship between players, and pulling together».[68]

Ritualization[edit]

Asad’s work critiqued the notion that there were universal characteristics of ritual to be found in all cases. Catherine Bell has extended this idea by shifting attention from ritual as a category, to the processes of «ritualization» by which ritual is created as a cultural form in a society. Ritualization is «a way of acting that is designed and orchestrated to distinguish and privilege what is being done in comparison to other, usually more quotidian, activities».[69]

Sociobiology and behavioral neuroscience[edit]

Anthropologists have also analyzed ritual via insights from other behavioral sciences. The idea that cultural rituals share behavioral similarities with personal rituals of individuals was discussed early on by Freud.[70] Dulaney and Fiske compared ethnographic descriptions of both rituals and non-ritual doings, such as work to behavioral descriptions from clinical descriptions of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD).[71] They note that OCD behavior often consists of such behavior as constantly cleaning objects, concern or disgust with bodily waste or secretions, repetitive actions to prevent harm, heavy emphasis on number or order of actions etc. They then show that ethnographic descriptions of cultural rituals contain around 5 times more of such content than ethnographic descriptions of other activities such as «work». Fiske later repeated similar analysis with more descriptions from a larger collection of different cultures, also contrasting descriptions of cultural rituals to descriptions of other behavioral disorders (in addition to OCD), in order to show that only OCD-like behavior (not other illnesses) shares properties with rituals.[72] The authors offer tentative explanations for these findings, for example that these behavioral traits are widely needed for survival, to control risk, and cultural rituals are often performed in the context of perceived collective risk.

Other anthropologists have taken these insights further, and constructed more elaborate theories based on the brain functions and physiology. Liénard and Boyer suggest that commonalities between obsessive behavior in individuals and similar behavior in collective contexts possibly share similarities due to underlying mental processes they call hazard precaution. They suggest that individuals of societies seem to pay more attention to information relevant to avoiding hazards, which in turn can explain why collective rituals displaying actions of hazard precaution are so popular and prevail for long periods in cultural transmission.[73]

Ritual as a methodological measure of religiosity[edit]

According to the sociologist Mervin Verbit, ritual may be understood as one of the key components of religiosity. And ritual itself may be broken down into four dimensions; content, frequency, intensity

and centrality. The content of a ritual may vary from ritual to ritual, as does the frequency of its practice, the intensity of the ritual (how much of an impact it has on the practitioner), and the centrality of the ritual (in that religious tradition).[74][75][76]

In this sense, ritual is similar to Charles Glock’s «practice» dimension of religiosity.[77]

Religious perspectives[edit]

In religion, a ritual can comprise the prescribed outward forms of performing the cultus, or cult, of a particular observation within a religion or religious denomination. Although ritual is often used in context with worship performed in a church, the actual relationship between any religion’s doctrine and its ritual(s) can vary considerably from organized religion to non-institutionalized spirituality, such as ayahuasca shamanism as practiced by the Urarina of the upper Amazon.[78] Rituals often have a close connection with reverence, thus a ritual in many cases expresses reverence for a deity or idealized state of humanity.

Christianity[edit]

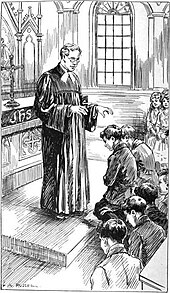

This Lutheran pastor administers the rite of confirmation on youth confirmands after instructing them in Luther’s Small Catechism.

In Christianity, a rite is used to refer to a sacred ceremony (such as anointing of the sick), which may or may not carry the status of a sacrament depending on the Christian denomination (in Roman Catholicism, anointing of the sick is a sacrament while in Lutheranism it is not). The word «rite» is also used to denote a liturgical tradition usually emanating from a specific center; examples include the Roman Rite, the Byzantine Rite, and the Sarum Rite. Such rites may include various sub-rites. For example, the Byzantine Rite (which is used by the Eastern Orthodox, Eastern Lutheran, and Eastern Catholic churches) has Greek, Russian, and other ethnically-based variants.

Islam[edit]

For daily prayers, practicing Muslims must perform a ritual recitation from the Quran in Arabic while bowing and prostrating. Quranic chapter 2 prescribes rituals such as the direction to face for prayers (qiblah); pilgrimage (Hajj), and fasting in Ramadan.[79] Iḥrām is a state of ritual purity in preparation for pilgrimage in Islam.[80]

Hajj rituals include circumambulation around the Kaʿbah.[81]… and show us our rites[82] — these rites (manāsik) are presumed the rituals of ḥajj.[81] Truly Ṣafā and Marwah are among the rituals of God[83] Saʿy is the ritual travel, partway between walking and running, seven times between the two hills.[84]

Freemasonry[edit]

In Freemasonry, rituals are scripted words and actions which employ Masonic symbolism to illustrate the principles espoused by Freemasons. These rituals are progressively taught to entrusted members during initiation into a particular Masonic rite composed of a series of degrees conferred by a Masonic body.[85] The degrees of Freemasonry derive from the three grades of medieval craft guilds; those of «Entered Apprentice», «Journeyman» (or «Fellowcraft»), and «Master Mason». In North America, Freemasons who have been raised to the degree of «Master Mason” have the option of joining appendant bodies that offer additional degrees to those, such as those of the Scottish Rite or the York Rite.

See also[edit]

- Behavioral script

- Builders’ rites

- Chinese ritual mastery traditions

- Confucianism § Rite and centring

- Gut (ritual)

- Kagura

- Nabichum

- Nuo rituals

- Process art

- Processional walkway

- Religious symbolism

- Ritualism in the Church of England

- Symbolic boundaries

- Taiping Qingjiao

- The Rite of Spring

References[edit]

- ^ «Definition of RITUAL». www.merriam-webster.com.

- ^ Turner, Victor Witter (1973). «Symbols in African Ritual (16 March 1973)». Science. 179 (4078): 1100–1105. Bibcode:1973Sci…179.1100T. doi:10.1126/science.179.4078.1100. PMID 17788268.

A ritual is a stereotyped sequence of activities involving gestures, words, and objects, performed in a sequestered place, and designed to influence preternatural entities or forces on behalf of the actors’ goals and interests.

- ^ Bell (1997), pp. 138–169.

- ^ Brown, Donald (1991). Human Universals. United States: McGraw Hill. p. 139.

- ^ Kyriakidis, E., ed. (2007). The archaeology of ritual. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology UCLA publications.

- ^ Festus, entry on ritus, p. 364 (edition of Lindsay).

- ^ Barbara Boudewijnse, «British Roots of the Concept of Ritual,» in Religion in the Making: The Emergence of the Sciences of Religion (Brill, 1998), p. 278.

- ^ Boudewijnse, «British Roots of the Concept of Ritual,» p. 278.

- ^ Boudewijnse, «British Roots of the Concept of Ritual,» p. 278, citing the Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ Tolbert (1990a).

- ^ Tolbert (1990b).

- ^ Wilce (2006).

- ^ Bell (1997), pp. 138-169.

- ^ Bell (1997), pp. 139–140.

- ^ «LET’S TALK TURKEY: 5 myths about the Thanksgiving holiday». The Patriot Ledger. November 26, 2009. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ Bell (1997), pp. 145–150.

- ^ Bell (1997), pp. 152–153.

- ^ Bell (1997), p. 155.

- ^ Bell (1997), p. 156.

- ^ Ortner, Sherry (1973). «On Key Symbols». American Anthropologist. 75 (5): 1340. doi:10.1525/aa.1973.75.5.02a00100.

- ^ Bell (1997), pp. 156–57.

- ^ Bell (1997), pp. 156–157.

- ^ Myerhoff, Barbara (1997). Secular Ritual. Amsterdam: Van Gorcum. p. 223.

- ^ Bell (1997), p. 94.

- ^ Turner (1969), p. 95.

- ^ Turner (1969), p. 97.

- ^ a b Turner (1973).

- ^ Turner (1967), p. 9ff.

- ^ Turner (1969), pp. 20–21.

- ^ Atkinson, Jane (1987). «The Effectiveness of Shamans in an Indonesian Ritual». American Anthropologist. 89 (2): 342. doi:10.1525/aa.1987.89.2.02a00040.

- ^ Bell (1997), pp. 102–103.

- ^ Eliade, Mircea (1954). The Myth of Eternal Return or, Cosmos and History. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 21.

- ^ Bell (1997), p. 109.

- ^ Bell (1997), p. 121.

- ^ Turner, Victor (1974). Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 23–35.

- ^ Kinser, Samuel (1990). Carnival, American Style; Mardi Gras at New Orleans and Mobile. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 282.

- ^ Ananti, Emmanuel (January 1986). AnthonyBonanno (ed.). Archaeology and Fertility Cult in the Ancient Mediterranean: First International Conference on Archaeology of the Ancient Mediterranean. B R Gruner Publishing. ISBN 9789027272539.

- ^ Aniela Jaffé, in C. G. Jung, Man and his Symbols (1978) p. 264

- ^ Desmond Morris, The Naked Ape Trilogy (London 1994) p. 246 and p. 34

- ^ Geertz (1980), pp. 13–17, 21.

- ^ Bell (1997), p. 130.

- ^ Worsley, Peter (1957). The Trumpet Shall Sound: A Study of ‘Cargo Cults’ in Melanesia. New York: Schocken books.

- ^ a b Lessa & Vogt (1979), pp. 36–38.

- ^ Lessa & Vogt (1979), p. 38.

- ^ Homans, George C. (1941). «Anxiety and Ritual: The Theories of Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown». American Anthropologist. 43 (2): 164–72. doi:10.1525/aa.1941.43.2.02a00020.

- ^ Radcliffe-Brown, A.R. (1939). Structure and Function in Primitive Society. London: Cohen and West. p. 143.

- ^ Leach, Edmund (1954). Political Systems of Highland Burma. London: Bell. pp. 12–13.

- ^ Rappaport, Roy (1979). Ecology, Meaning and Religion. Richmond, CA: North Atlantic Books. p. 41.

- ^ Lansing, Stephen (1991). Priests and Programmers: technologies of power in the engineered landscape of Bali. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Gluckman, Max (1963). Order and Rebellion in South East Africa: Collected Essays. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- ^ Bell, Catherine (1992). Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 42–43.

- ^ Turner (1967), p. 30.

- ^ Douglas, Mary (1973). Natural Symbols: Explorations in Cosmology. New York: Vintage Books.

- ^ Turner (1969), p. 96.

- ^ Turner (1967), pp. 96–97.

- ^ Bell, Catherine (1992). Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 128.

- ^ Kuper, Adam (1983). Anthropology and Anthropologists: The Modern British School. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 156–57. ISBN 9780710094094.

- ^ Geertz, Clifford (1973). The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books. p. 112. ISBN 9780465097197.

- ^ Bell, Catherine (1992). Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 66–67.

- ^ Hughes-Freeland, Felicia (ed.). Ritual, Performance, Media. London: Routledge. p. 2.

- ^ Bloch, Maurice (1974). «Symbols, Song, Dance and Features of Articulation: Is Religion an Extreme Form of Traditional Authority?». Archives Européennes de Sociologie. 15 (1): 55–84. doi:10.1017/s0003975600002824. S2CID 145170270.

- ^ Csordas, Thomas J. (2001) [1997]. Language, Charisma, & Creativity: Ritual Life in the Catholic Charismatic Renewal. Basingstoke: Palgrave. pp. 255–65.

- ^ Asad (1993), p. 64.

- ^ Asad (1993), pp. 56–57.

- ^ Asad (1993), pp. 58–60.

- ^ Asad (1993), p. 73.

- ^ Asad (1993), p. 63.

- ^ Foley, Douglas (2010). Learning Capitalist Culture: Deep in the Heart of Tejas. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 53.

- ^ Bell, Catherine (1992). Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 74.

- ^ Freud, S. (1928) Die Zukunft einer Illusion. Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag.

- ^ Dulaney, S.; Fiske, A. P. Cultural Rituals and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Is There a Common Psychological Mechanism? Ethos 1994, 22 (3), 243–283. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.1994.22.3.02a00010.

- ^ Fiske, A. P.; Haslam, N. Is Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder a Pathology of the Human Disposition to Perform Socially Meaningful Rituals? Evidence of Similar Content. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1997, 185 (4), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199704000-00001 Archived 2022-11-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Liénard, P.; Boyer, P. Whence Collective Rituals? A Cultural Selection Model of Ritualized Behavior. American Anthropologist 2006, 108 (4), 814–827. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2006.108.4.814.

- ^ Verbit, M.F. (1970). The components and dimensions of religious behavior: Toward a reconceptualization of religiosity. American mosaic, 24, 39.

- ^ Küçükcan, T. (2010). Multidimensional Approach to Religion: a way of looking at religious phenomena. Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies, 4(10), 60–70.

- ^ Küçükcan, Talip*. «Can Religiosity be Measured? Dimensions of Religious Commitment: Theories Revisited» (PDF). www.eskieserler.com.

- ^ Glock, Charles Y. (1972). «On the Study of Religious Commitment». In Faulkner, J.E. (ed.). Religion’s Influence in Contemporary Society, Readings in the Sociology of Religion. Ohio: Charles E. Merril. pp. 38–56.

- ^ Dean, Bartholomew (2009). Urarina Society, Cosmology, and History in Peruvian Amazonia Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine, Gainesville: University Press of Florida ISBN 978-0-8130-3378-5

- ^ Lumbard, Joseph (April 2015). Introduction, The Study Quran. San Francisco: HarperOne.

- ^ Dagli, Caner (April 2015). Q2:189 Study notes, The Study Quran. San Francisco: HarperOne.

- ^ a b Dagli, Caner (April 2015). 2, The Cow, al-Baqarah, The Study Quran. San Francisco: HarperOne.

- ^ Quran 2:128 (Q2:128 Archived 2021-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, 50+ translations, islamawakened.com)

- ^ Quran 2:158 (Q2:158 Archived 2021-09-22 at the Wayback Machine, 50+ translations, islamawakened.com)

- ^ Dagli, Caner (April 2015). Q2:158 Study notes, The Study Quran. San Francisco: HarperOne.

- ^ Snoek, Jan A.M. (2014). «Masonic Rituals of Initiation». In Bodgan, Henrik; Snoek, Jan A.M. (eds.). Handbook of Freemasonry. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Vol. 8. Leiden: BRILL. pp. 319–327. doi:10.1163/9789004273122_018. ISBN 978-90-04-21833-8. ISSN 1874-6691.

Cited literature[edit]

- Asad, Talal (1993). «Toward a genealogy of the concept of ritual». Genealogies of Religion. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Bell, Catherine (1997). Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Geertz, Clifford (1980). Negara: the Theatre State in Nineteenth-Century Bali. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Lessa, William A.; Vogt, Evon Z., eds. (1979). Reader in Comparative Religion: An Anthropological Approach. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 9780060439910.

- Tolbert, Elizabeth (1990a). «Women Cry with Words: Symbolization of Affect in the Karelian Lament». Yearbook for Traditional Music. 22: 80–105. doi:10.2307/767933. JSTOR 767933. S2CID 192949893.

- Tolbert, Elizabeth (1990b). «Magico-Religious Power and Gender in the Karelian Lament». In Herndon, M.; Zigler, S. (eds.). Music, Gender, and Culture, vol. 1. Intercultural Music Studies. Wilhelmshaven, DE.: International Council for Traditional Music, Florian Noetzel Verlag. pp. 41–56.

- Turner, Victor W. (1967). The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Turner, Victor W. (1969). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Wilce, James M. (2006). «Magical Laments and Anthropological Reflections: The Production and Circulation of Anthropological Text as Ritual Activity». Current Anthropology. 47 (6): 891–914. doi:10.1086/507195. S2CID 11691889.

Further reading[edit]

- Aractingi, Jean-Marc and G. Le Pape. (2011) «Rituals and catechisms in Ecumenical Rite» in East and West at the Crossroads Masonic, Editions l’Harmattan- Paris ISBN 978-2-296-54445-1.

- Bax, Marcel. (2010). ‘Rituals’. In: Jucker, Andeas H. & Taavitsainen, Irma, eds. Handbook of Pragmatics, Vol. 8: Historical Pragmatics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 483–519.

- Bloch, Maurice. (1992) Prey into Hunter: The Politics of Religious Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Buc, Philippe. (2001) The Dangers of Ritual. Between Early Medieval Texts and Social Scientific Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Buc, Philippe. (2007). ‘The monster and the critics. A ritual reply’. Early Medieval Europe 15: 441–52.

- Carrico, K., ed. (2011). ‘Ritual.’ Cultural Anthropology (Journal of the Society for Cultural Anthropology). Virtual Issue: http://www.culanth.org/?q=node/462.

- D’Aquili, Eugene G., Charles D. Laughlin and John McManus. (1979) The Spectrum of Ritual: A Biogenetic Structural Analysis. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Douglas, Mary. (1966) Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge.

- Durkheim, E. (1965 [1915]). The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. New York: The Free Press.

- Etzioni, Amitai. (2000). «Toward a theory of public ritual.» Sociological Theory 18(1): 44-59.

- Erikson, Erik. (1977) Toys and Reasons: Stages in the Ritualization of Experience. New York: Norton.

- Fogelin, L. (2007). The Archaeology of Religious Ritual. Annual Review of Anthropology 36: 55–71.

- Gennep, Arnold van. (1960) The Rites of Passage. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Grimes, Ronald L. (2014) The Craft of Ritual Studies. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Grimes, Ronald L. (1982, 2013) Beginnings in Ritual Studies. Third edition. Waterloo, Canada: Ritual Studies International.

- Kyriakidis, E., ed. (2007) The archaeology of ritual. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology UCLA publications

- Lawson, E.T. & McCauley, R.N. (1990) Rethinking Religion: Connecting Cognition and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Malinowski, Bronisław. (1948) Magic, Science and Religion. Boston: Beacon Press.

- McCorkle Jr., William W. (2010) Ritualizing the Disposal of Dead Bodies: From Corpse to Concept. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

- Perniola Mario. (2000). Ritual Thinking. Sexuality, Death, World, foreword by Hugh J. Silverman, with author’s introduction, Amherst (USA), Humanity Books.

- Post, Paul (2015) ‘Ritual Studies’, in: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion 1-23. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.21

- Rappaport, Roy A. (1999) Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Seijo, F. (2005). «The Politics of Fire: Spanish Forest Policy and Ritual Resistance in Galicia, Spain». Environmental Politics 14 (3): 380–402

- Silverstein, M. (2003). Talking Politics :The Substance of Style from Abe to «W». Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press (distributed by University of Chicago).

- Silverstein, M. (2004). «»Cultural» Concepts and the Language-Culture Nexus». Current Anthropology 45: 621–52.

- Smith, Jonathan Z. (1987) To Take Place: Toward Theory in Ritual. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Staal, Frits (1990) Ritual and Mantras: Rules Without Meaning. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

- Stollberg-Rilinger, Barbara (2013). Rituale. Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 2013

- Utz, Richard. “Negotiating Heritage: Observations on Semantic Concepts, Temporality, and the Centre for the Study of the Cultural Heritage of Medieval Rituals.” Philologie im Netz (2011): 70-87.

- Yatromanolakis, Dimitrios and Panagiotis Roilos, (2003). Towards a Ritual Poetics, Athens, Foundation of the Hellenic World.

- Yatromanolakis, Dimitrios and Panagiotis Roilos (eds.), (2005) Greek Ritual Poetics, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press.

Noun

The priest will perform the ritual.

He was buried simply, without ceremony or ritual.

the daily ritual of preparing breakfast

His day-to-day life is based on ritual.

Recent Examples on the Web

In this context, my door-locking was less practical than ritual, one that brought me some inchoate sense of safety and wellbeing, like a psychic sugar pill.

—

The power of a sports ritual bridges right and left.

—

The power of a sports ritual bridges right and left.

—

The Tequesta village on the south bank of the Miami River and nearby Miami Circle may have been the settings for similar ritual acts focused on freshwater.

—

Their post meal-ritual?

—

Those fears are powering fresh accusations of ritual abuse online, which are amplified on social media and by partisan media, and can mobilize mobs to seek vigilante justice.

—

Medieval Christian worship books from the 10th and 11th centuries show that a ritual procession outside churches became a standard feature of Palm Sunday celebrations in Western Christianity.

—

Musk’s daily doughnut ritual runs parallel to his previous statement on health and nutrition.

—

What closure Chung does receive is afforded through the ritual of the funeral, a small mercy.

—

But most entertaining may have been the ritual of showering the newlyweds with money all night.

—

Sipping a warm cup of prune juice just might become your pre-bedtime, constipation-preventing ritual.

—

All of it would bring a sense of unpredictability and surprise to complement the more predictable rituals of the week-by-week subscription season.

—

Spring is nearly here, and with it, the reliable rituals of the season: longer days, colorful blossoms, the delightful return of songbirds and, of course, people completely freezing off their behinds at baseball practice.

—

Behind it, a gathering of assembly robots stands in a circle like sci-fi Satanists preparing a ritual of UV lights and high-tech epoxy.

—

But the annual ritual of the president delivering a budget request to Congress was a useful opportunity for Biden to stake out ground in the bitter standoff over next year’s spending levels and the raising of the debt ceiling.

—

Glen Luchford/Courtesy of Gucci Ahead, Julia Garner shares her beauty and wellness rituals, which women and countries inspire her, and even some past fashion fails for Glamour’s Big Beauty Questions.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘ritual.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Asked by: Johnathon Armstrong

Score: 5/5

(56 votes)

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community.

What is an example of ritual?

Ritual is defined as something that is characteristic of a rite, practice or observation, particularly of a religion. An example of ritual is the recitation of traditional vows in a Catholic wedding ceremony. … The definition of a ritual is a rite, practice or observance, particularly in a religion.

What is ritual in simple words?

1 : the established form for a ceremony specifically : the order of words prescribed for a religious ceremony. 2a : ritual observance specifically : a system of rites. b : a ceremonial act or action. c : an act or series of acts regularly repeated in a set precise manner.

What is another word for ritual?

Synonyms of ritual

- custom,

- fashion,

- habit,

- habitude,

- pattern,

- practice.

- (also practise),

- second nature,

What does ritual mean in the dictionary?

noun. an established or prescribed procedure for a religious or other rite. a system or collection of religious or other rites. observance of set forms in public worship. a book of rites or ceremonies.

19 related questions found

What is the difference between ceremony and ritual?

A ritual refers to group of actions performed for their symbolic value. On the other hand, a ceremony is performed on a special occasion. This is the major difference between the two words. … The purpose of rituals differs according to the society and the religious beliefs.

What is a non religious ritual?

Ritual practices that enact, celebrate, or bring about otherness from a religious institution or tradition, typically the locally dominant tradition. …

What is the opposite of a ritual?

Opposite of an act performed for religious or ceremonial reasons. carelessness. heedlessness. neglect. thoughtlessness.

What do you call a religious ritual?

1. religious ritual — a ceremony having religious meaning. religious ceremony. ceremony — the proper or conventional behavior on some solemn occasion; «an inaugural ceremony»

What is the meaning of ritual ceremony?

A ritual is a ceremony or action performed in a customary way. … As an adjective, ritual means «conforming to religious rites,» which are the sacred, customary ways of celebrating a religion or culture. Different communities have different ritual practices, like meditation in Buddhism, or baptism in Christianity.

What are common rituals?

Rituals are a feature of all known human societies. They include not only the worship rites and sacraments of organized religions and cults, but also rites of passage, atonement and purification rites, oaths of allegiance, dedication ceremonies, coronations and presidential inaugurations, marriages, funerals and more.

Does a ritual have to be religious?

When rituals make people «feel good», they reinforce the belief that their religion is the «correct» one. Not all rituals are religious. Brushing your teeth every morning in the same place and in the same way is a non-religious ritual. … However, it rarely involves a belief in supernatural beings or forces.

What is cultural ritual?

A ritual is a patterned, repetitive, and symbolic enactment of a cultural belief or value. … Rituals are most commonly thought of as religious, but they can enact secular beliefs and values as effectively as religious ones.

What family rituals do you practice?

Family rituals: what are they?

- special morning kisses or crazy handshakes.

- code words for things or special names you use for each other.

- a special wink for your child at school drop-off.

- your own rules for sports or board games.

What is an example of a cultural ritual?

Examples of Cultural Rituals

Many cultures ritualize the moment when a child becomes an adult. Often, such rituals connect to a culture’s religious beliefs. For example, a bar or bat mitzvah is the coming of age ritual in the Jewish faith.

What are rituals and routines?

The difference between a routine and a ritual is the attitude behind the action. While routines can be actions that just need to be done—such as making your bed or taking a shower—rituals are viewed as more meaningful practices which have a real sense of purpose. Rituals do not have to be spiritual or religious.

What is the religious ritual?

Definition. A religious ritual is any repetitive and patterned behavior that is prescribed by or tied to a religious institution, belief, or custom, often with the intention of communicating with a deity or supernatural power.

What is the difference between religion and ritual?

Religion can be used to justify things and to motivate others. Rituals and ceremonies are practiced to show dedication and faith to a religion.

What is the antonym of loneliness?

Alone is a neutral description of a state that can be experienced any number of ways. Loneliness is, by definition, painful. The opposite of loneliness is contentment or joy. It is living your most meaningful life, the life you want to live rather than the life you think you should be living.

What is the synonyms of sacred?

In this page you can discover 67 synonyms, antonyms, idiomatic expressions, and related words for sacred, like: divine, holy, pure, sacrosanctity, saintly, ordained, guarded, sanctioned, pious, consecrated and unconsecrated.

What is an antonym for tradition?

▲ Opposite of the transmission of customs or beliefs from generation to generation. innovation. invention. creation.

Do atheist do rituals?

Atheist and Humanist organisations offer their own rituals for these events that give them meaning and significance without any religious content. These ceremonies differ from mainstream secular ceremonies like civil weddings, in that they are highly personalised for the individuals concerned.

What are the 3 rites of passage?

At their most basic, all rites of passage are characterized by three distinct phases: separation (leaving the familiar), transition (a time of testing, learning and growth), and return (incorporation and reintegration).

Is Agnostic a religion?

Atheism is the doctrine or belief that there is no god. However, an agnostic neither believes nor disbelieves in a god or religious doctrine. … Agnosticism was coined by biologist T.H. Huxley and comes from the Greek ágnōstos, which means “unknown or unknowable.”

What is ritual behavior?

Ritual behaviors are symbolic expressions through which individuals articulate their social and metaphysical affiliations. Ritual phenomena are distinguished from other motes of experience by the extent to which they are scripted behavior episodes.

Other forms: rituals

A ritual is a ceremony or action performed in a customary way. Your family might have a Saturday night ritual of eating a big spaghetti dinner and then taking a long walk to the ice cream shop.

As an adjective, ritual means «conforming to religious rites,» which are the sacred, customary ways of celebrating a religion or culture. Different communities have different ritual practices, like meditation in Buddhism, or baptism in Christianity. We also call the ceremony itself a ritual. Although it comes from religious ceremonies, ritual can also be used for any time-honored tradition, like the Superbowl, or Mardi Gras, or Sunday morning pancake breakfast.

Definitions of ritual

-

noun

the prescribed procedure for conducting religious ceremonies

-

noun

any customary observance or practice

-

noun

stereotyped behavior

see moresee less-

type of:

-

habit, use

(psychology) an automatic pattern of behavior in reaction to a specific situation; may be inherited or acquired through frequent repetition

-

habit, use

-

adjective

of or relating to or characteristic of religious rituals

-

adjective

of or relating to or employed in social rites or rituals

“a

ritual dance of Haiti”“»sedate little colonial tribe with its

ritual tea parties»- Nadine Gordimer”

DISCLAIMER: These example sentences appear in various news sources and books to reflect the usage of the word ‘ritual’.

Views expressed in the examples do not represent the opinion of Vocabulary.com or its editors.

Send us feedback

EDITOR’S CHOICE

Look up ritual for the last time

Close your vocabulary gaps with personalized learning that focuses on teaching the

words you need to know.

Sign up now (it’s free!)

Whether you’re a teacher or a learner, Vocabulary.com can put you or your class on the path to systematic vocabulary improvement.

Get started

rit·u·al

(rĭch′o͞o-əl)

n.

1.

a. A ceremony in which the actions and wording follow a prescribed form and order.

b. The body of ceremonies or rites used in a place of worship or by an organization: according to Catholic ritual.

2. A book of rites or ceremonial forms.

3. A set of actions that are conducted routinely in the same manner: My household chores have become a morning ritual.

4. Zoology A set of actions that an animal performs in a fixed sequence, often as a means of communication: the greeting ritual in baboons.

adj.

1. Associated with or performed according to a rite or ritual: a priest’s ritual garments; a ritual sacrifice.

2. Being part of an established routine: a ritual glass of milk before bed.

[From Latin rītuālis, of rites, from rītus, rite; see rite.]

rit′u·al·ly adv.

American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. Copyright © 2016 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

ritual

(ˈrɪtjʊəl)

n

1. (Ecclesiastical Terms) the prescribed or established form of a religious or other ceremony

2. (Other Non-Christian Religions) the prescribed or established form of a religious or other ceremony

3. (Ecclesiastical Terms) such prescribed forms in general or collectively

4. (Other Non-Christian Religions) such prescribed forms in general or collectively

5. stereotyped activity or behaviour

6. (Psychology) psychol any repetitive behaviour, such as hand-washing, performed by a person with a compulsive personality disorder

7. any formal act, institution, or procedure that is followed consistently: the ritual of the law.

adj

8. (Ecclesiastical Terms) of, relating to, or characteristic of religious, social, or other rituals

9. (Other Non-Christian Religions) of, relating to, or characteristic of religious, social, or other rituals

[C16: from Latin rītuālis, from rītus rite]

ˈritually adv

Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged, 12th Edition 2014 © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1994, 1998, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2014

rit•u•al

(ˈrɪtʃ u əl)

n.

1.

a. an established procedure for a religious or other rite.

b. a system of such rites.

2. observance of set forms in public worship.

3. a book of rites or ceremonies.

4. prescribed, established, or ceremonial acts or features collectively.

5. any practice or pattern of behavior regularly performed in a set manner.

6. Psychiatry. a specific act, as hand-washing, performed repetitively to a pathological degree.

adj.

7. being or practiced as a rite or ritual: a ritual dance.

8. of or pertaining to rites or ritual: ritual laws.

[1560–70; < Latin rītuālis=rītu-, s. of rītus rite + -ālis -al1]

rit′u•al•ly, adv.

Random House Kernerman Webster’s College Dictionary, © 2010 K Dictionaries Ltd. Copyright 2005, 1997, 1991 by Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.

ThesaurusAntonymsRelated WordsSynonymsLegend:

| Noun | 1. |  ritual — any customary observance or practice ritual — any customary observance or practice

rite custom, usage, usance — accepted or habitual practice ceremonial dance, ritual dance, ritual dancing — a dance that is part of a religious ritual betrothal, espousal — the act of becoming betrothed or engaged marriage ceremony, wedding, marriage — the act of marrying; the nuptial ceremony; «their marriage was conducted in the chapel» rite of passage — a ritual performed in some cultures at times when an individual changes status (as from adolescence to adulthood) |

| 2. | ritual — the prescribed procedure for conducting religious ceremonies

ablution — the ritual washing of a priest’s hands or of sacred vessels practice, pattern — a customary way of operation or behavior; «it is their practice to give annual raises»; «they changed their dietary pattern» solemnisation, solemnization, celebration — the public performance of a sacrament or solemn ceremony with all appropriate ritual; «the celebration of marriage» Communion, Holy Communion, manduction, sacramental manduction — the act of participating in the celebration of the Eucharist; «the governor took Communion with the rest of the congregation» |

|

| 3. | ritual — stereotyped behavior

habit, use — (psychology) an automatic pattern of behavior in reaction to a specific situation; may be inherited or acquired through frequent repetition; «owls have nocturnal habits»; «she had a habit twirling the ends of her hair»; «long use had hardened him to it» |

|

| Adj. | 1. | ritual — of or relating to or characteristic of religious rituals; «ritual killing» |

| 2. | ritual — of or relating to or employed in social rites or rituals; «a ritual dance of Haiti»; «sedate little colonial tribe with its ritual tea parties»- Nadine Gordimer |

Based on WordNet 3.0, Farlex clipart collection. © 2003-2012 Princeton University, Farlex Inc.

ritual

noun

2. custom, tradition, routine, convention, form, practice, procedure, habit, usage, protocol, formality, ordinance Italian culture revolves around the ritual of eating.

adjective

1. ceremonial, formal, conventional, routine, prescribed, stereotyped, customary, procedural, habitual, ceremonious Here, the conventions required me to make the ritual noises.

Collins Thesaurus of the English Language – Complete and Unabridged 2nd Edition. 2002 © HarperCollins Publishers 1995, 2002

ritual

noun

1. A formal act or set of acts prescribed by ritual:

2. A conventional social gesture or act without intrinsic purpose:

adjective

Of or characterized by ceremony:

The American Heritage® Roget’s Thesaurus. Copyright © 2013, 2014 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Translations

rituálrituální

ritualrituelceremoniel

rituaalirituaalinen

ritualritualan

rituálisszertartásszertartásokszertartásosünnepélyes

helgisiîa-helgisiîir, ritúal

儀式儀式の

의례적인의식

rituálrituálny

obred

ritualrituell

เกี่ยวกับพิธีกรรมพิธีกรรมทางศาสนา

lễ nghitheo lễ nghi

ritual

[ˈrɪtjʊəl]

A. ADJ

1. [dancing, murder] → ritual

Collins Spanish Dictionary — Complete and Unabridged 8th Edition 2005 © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1971, 1988 © HarperCollins Publishers 1992, 1993, 1996, 1997, 2000, 2003, 2005

ritual

[ˈrɪtʃuəl]

adj

[dancing, chanting, sacrifice, murder] → rituel(le)

[conventional] → rituel(le)

Collins English/French Electronic Resource. © HarperCollins Publishers 2005

ritual

Collins German Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged 7th Edition 2005. © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1980 © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1997, 1999, 2004, 2005, 2007

ritual

[ˈrɪtjʊəl] adj & n → rituale (m)

Collins Italian Dictionary 1st Edition © HarperCollins Publishers 1995

rite

(rait) noun

a solemn ceremony, especially a religious one. marriage rites.

ritual (ˈritʃuəl) noun

(a particular set of) traditional or fixed actions etc used in a religious etc ceremony. Christian rituals; the ritual of the Roman Catholic church.

adjective

forming (part of) a ritual or ceremony. a ritual dance/sacrifice.

Kernerman English Multilingual Dictionary © 2006-2013 K Dictionaries Ltd.

ritual

→ شَعَائِريّ, شَعِيرَة rituál, rituální ritual, rituel Ritual, rituell τελετή, τελετουργικός ritual rituaali, rituaalinen rite, rituel ritual, ritualan rituale 儀式, 儀式の 의례적인, 의식 ritueel rituale, rituell rytuał, rytualny ritual ритуал, ритуальный ritual, rituell เกี่ยวกับพิธีกรรม, พิธีกรรมทางศาสนา ayin, ayinsel lễ nghi, theo lễ nghi 典礼, 典礼的

Multilingual Translator © HarperCollins Publishers 2009

English-Spanish/Spanish-English Medical Dictionary Copyright © 2006 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.