Subject: не могу понять смысл и нормально сформулировать gen.

не могу понять смысл и нормально сформулировать предложение.

я знаю, что я не достаточно опытный в переводах. Но я только учусь на дополнительных курсах!

Помогите в формулировке последнего предложения, пожалуйста.

Potlatch.

The word «potlatch» comes from the Chinook jargon and originally meant «to give». In its common use among the white people and the natives of the Northwest Coast it has taken on a very general meaning and applied to any Indian festival at which there is feasting, or, in connection with which property is given away. Because of this loose and general meaning there necessarily exists a good deal of confusion as to what is meant by the term. From the Indian’s viewpoint many different things are meant when he uses the Chinook word in speaking to white people, for it is the only word intelligible to them by means of which he can refer to a considerable number of ceremonies or festivals each having its own Indian name.

Потлач

Слово «потлач» пришло от Чинукского жаргона и первоначально означало «давать». В его общем употреблении, среди белых людей и коренного населения Северо-западного прибрежья, оно было принято общепринятым, и применялось в любых Индийских фестивалях, в которых есть пирующие или в определенной коммуникации. В связи с этой утраты и общепринятого значения неизбежно встречается определенная путаница, что же значится под этим термином. С точки зрения Индийцев множество различных значений обозначают, когда он использует слово Чинук в общении с белыми людьми, только понятное слово им значениями, которыми он может быть отнесен к значительному количеству церемонии или фестивалям, каждый из которых имеет свое Индийское название.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A potlatch is a gift-giving feast practiced by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada and the United States,[1] among whom it is traditionally the primary governmental institution, legislative body, and economic system.[2] This includes the Heiltsuk, Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit, Makah, Tsimshian,[3] Nuu-chah-nulth,[4] Kwakwaka’wakw,[2] and Coast Salish cultures.[5] Potlatches are also a common feature of the peoples of the Interior and of the Subarctic adjoining the Northwest Coast, although mostly without the elaborate ritual and gift-giving economy of the coastal peoples (see Athabaskan potlatch).

A potlatch involves giving away or destroying wealth or valuable items in order to demonstrate a leader’s wealth and power. Potlatches are also focused on the reaffirmation of family, clan, and international connections, and the human connection with the supernatural world. Potlatch also serves as a strict resource management regime, where coastal peoples discuss, negotiate, and affirm rights to and uses of specific territories and resources.[6][7][8] Potlatches often involve music, dancing, singing, storytelling, making speeches, and often joking and games. The honouring of the supernatural and the recitation of oral histories are a central part of many potlatches.

From 1885 to 1951, the Government of Canada criminalized potlatches. However, the practice persisted underground despite the risk of government reprisals including mandatory jail sentences of at least two months; the practice has also been studied by many anthropologists. Since the practice was decriminalized in 1951, the potlatch has re-emerged in some communities. In many it is still the bedrock of Indigenous governance, as in the Haida Nation, which has rooted its democracy in potlatch law.[9][10]

The word comes from the Chinook Jargon, meaning «to give away» or «a gift»; originally from the Nuu-chah-nulth word paɬaˑč, to make a ceremonial gift in a potlatch.[1]

Overview[edit]

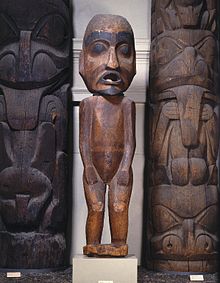

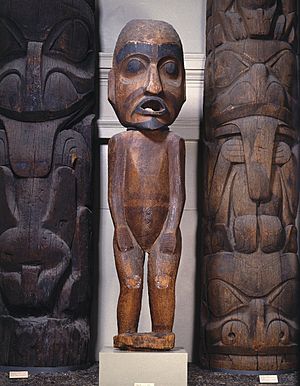

Speaker Figure, 19th century, Brooklyn Museum, the figure represents a speaker at a potlatch. An orator standing behind the figure would have spoken through its mouth, announcing the names of arriving guests.

- N.B. This overview concerns the Kwakwaka’wakw potlatch. Potlatch traditions and formalities and kinship systems in other cultures of the region differ, often substantially.

A potlatch was held on the occasion of births, deaths, adoptions, weddings, and other major events. Typically the potlatch was practiced more in the winter seasons as historically the warmer months were for procuring wealth for the family, clan, or village, then coming home and sharing that with neighbors and friends. The event was hosted by a numaym, or ‘House’, in Kwakwaka’wakw culture. A numaym was a complex cognatic kin group usually headed by aristocrats, but including commoners and occasional slaves. It had about one hundred members and several would be grouped together into a nation. The House drew its identity from its ancestral founder, usually a mythical animal who descended to earth and removed his animal mask, thus becoming human. The mask became a family heirloom passed from father to son along with the name of the ancestor himself. This made him the leader of the numaym, considered the living incarnation of the founder.[11]: 192

Only rich people could host a potlatch. Tribal slaves were not allowed to attend a potlatch as a host or a guest. In some instances, it was possible to have multiple hosts at one potlatch ceremony (although when this occurred the hosts generally tended to be from the same family). If a member of a nation had suffered an injury or indignity, hosting a potlatch could help to heal their tarnished reputation (or «cover his shame», as anthropologist H. G. Barnett worded it).[12] The potlatch was the occasion on which titles associated with masks and other objects were «fastened on» to a new office holder. Two kinds of titles were transferred on these occasions. Firstly, each numaym had a number of named positions of ranked «seats» (which gave them a seat at potlatches) transferred within itself. These ranked titles granted rights to hunting, fishing and berrying territories.[11]: 198 Secondly, there were a number of titles that would be passed between numayma, usually to in-laws, which included feast names that gave one a role in the Winter Ceremonial.[11]: 194 Aristocrats felt safe giving these titles to their out-marrying daughter’s children because this daughter and her children would later be rejoined with her natal numaym and the titles returned with them.[11]: 201 Any one individual might have several «seats» which allowed them to sit, in rank order, according to their title, as the host displayed and distributed wealth and made speeches. Besides the transfer of titles at a potlatch, the event was given «weight» by the distribution of other less important objects such as Chilkat blankets, animal skins (later Hudson Bay blankets) and ornamental «coppers». It is the distribution of large numbers of Hudson Bay blankets, and the destruction of valued coppers that first drew government attention (and censure) to the potlatch.[11]: 205 On occasion, preserved food was also given as a gift during a potlatch ceremony. Gifts known as sta-bigs consisted of preserved food that was wrapped in a mat or contained in a storage basket.[13]

Dorothy Johansen describes the dynamic: «In the potlatch, the host in effect challenged a guest chieftain to exceed him in his ‘power’ to give away or to destroy goods. If the guest did not return 100 percent on the gifts received and destroy even more wealth in a bigger and better bonfire, he and his people lost face and so his ‘power’ was diminished.»[14] Hierarchical relations within and between clans, villages, and nations, were observed and reinforced through the distribution or sometimes destruction of wealth, dance performances, and other ceremonies. The status of any given family is raised not by who has the most resources, but by who distributes the most resources. The hosts demonstrate their wealth and prominence through giving away goods.

Potlatch ceremonies were also used as coming-of-age rituals. When children were born, they would be given their first name at the time of their birth (which was usually associated with the location of their birthplace). About a year later, the child’s family would hold a potlatch and give gifts to the guests in attendance on behalf of the child. During this potlatch, the family would give the child their second name. Once the child reached about 12 years of age, they were expected to hold a potlatch of their own by giving out small gifts that they had collected to their family and people, at which point they would be able to receive their third name.[15]

For some cultures, such as Kwakwaka’wakw, elaborate and theatrical dances are performed reflecting the hosts’ genealogy and cultural wealth. Many of these dances are also sacred ceremonies of secret societies like the hamatsa, or display of family origin from supernatural creatures such as the dzunukwa.

Chief O’wax̱a̱laga̱lis of the Kwagu’ł describes the potlatch in his famous speech to anthropologist Franz Boas,

We will dance when our laws command us to dance, we will feast when our hearts desire to feast. Do we ask the white man, ‘Do as the Indian does’? No, we do not. Why, then, will you ask us, ‘Do as the white man does’? It is a strict law that bids us to dance. It is a strict law that bids us to distribute our property among our friends and neighbors. It is a good law. Let the white man observe his law; we shall observe ours. And now, if you are come to forbid us to dance, begone; if not, you will be welcome to us.[16]

Among the various First Nations groups which inhabited the region along the coast, a variety of differences existed in regards to practises relating to the potlatch ceremony. Each nation, community, and sometimes clan maintained its own way of practicing the potlatch with diverse presentation and meaning. The Tlingit and Kwakiutl nations of the Pacific Northwest, for example, held potlatch ceremonies for different occasions. The Tlingit potlatches occurred for succession (the granting of tribal titles or land) and funerals. The Kwakiutl potlatches, on the other hand, occurred for marriages and incorporating new people into the nation (i.e., the birth of a new member of the nation.)[17] The potlatch, as an overarching term, is quite general, since some cultures have many words in their language for various specific types of gatherings. It is important to keep this variation in mind as most of our detailed knowledge of the potlatch was acquired from the Kwakwaka’wakw around Fort Rupert on Vancouver Island in the period 1849 to 1925, a period of great social transition in which many aspects of the potlatch became exacerbated in reaction to efforts by the Canadian government to culturally assimilate First Nations communities into the dominant white culture.[11]: 188–208

History[edit]

Prior to European colonization, gifts included storable food (oolichan, or candlefish, oil or dried food), canoes, slaves, and ornamental «coppers» among aristocrats, but not resource-generating assets such as hunting, fishing and berrying territories. Coppers were sheets of beaten copper, shield-like in appearance; they were about two feet long, wider on top, cruciform frame and schematic face on the top half. None of the copper used was ever of Indigenous metal. A copper was considered the equivalent of a slave. They were only ever owned by individual aristocrats, and never by numaym, hence could circulate between groups. Coppers began to be produced in large numbers after the colonization of Vancouver Island in 1849 when war and slavery were ended.[11]: 206

Example of an ornamental copper used at a potlatch

The arrival of Europeans resulted in the introduction of numerous diseases against which Indigenous peoples had no immunity, resulting in a massive population decline. Competition for the fixed number of potlatch titles grew as commoners began to seek titles from which they had previously been excluded by making their own remote or dubious claims validated by a potlatch. Aristocrats increased the size of their gifts in order to retain their titles and maintain social hierarchy.[18] This resulted in massive inflation in gifting made possible by the introduction of mass-produced trade goods in the late 18th and earlier 19th centuries. Archaeological evidence for the potlatching ceremony is suggested from the ~1,000 year-old Pickupsticks site in interior Alaska.[19]

Potlatch ban[edit]

Potlatching was made illegal in Canada in 1884 in an amendment to the Indian Act,[20] largely at the urging of missionaries and government agents who considered it «a worse than useless custom» that was seen as wasteful, unproductive, and contrary to ‘civilized values’ of accumulation.[21] The potlatch was seen as a key target in assimilation policies and agendas. Missionary William Duncan wrote in 1875 that the potlatch was «by far the most formidable of all obstacles in the way of Indians becoming Christians, or even civilized».[22] Thus in 1884, the Indian Act was revised to include clauses banning the Potlatch and making it illegal to practice. Section 3 of the Act read,

Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the «Potlatch» or the Indian dance known as the «Tamanawas» is guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be liable to imprisonment for a term not more than six nor less than two months in any gaol or other place of confinement; and, any Indian or other person who encourages, either directly or indirectly, an Indian or Indians to get up such a festival or dance, or to celebrate the same, or who shall assist in the celebration of same is guilty of a like offence, and shall be liable to the same punishment.[23]

In 1888, the anthropologist Franz Boas described the potlatch ban as a failure:

The second reason for the discontent among the Indians is a law that was passed, some time ago, forbidding the celebrations of festivals. The so-called potlatch of all these tribes hinders the single families from accumulating wealth. It is the great desire of every chief and even of every man to collect a large amount of property, and then to give a great potlatch, a feast in which all is distributed among his friends, and, if possible, among the neighboring tribes. These feasts are so closely connected with the religious ideas of the natives, and regulate their mode of life to such an extent, that the Christian tribes near Victoria have not given them up. Every present received at a potlatch has to be returned at another potlatch, and a man who would not give his feast in due time would be considered as not paying his debts. Therefore the law is not a good one, and can not be enforced without causing general discontent. Besides, the Government is unable to enforce it. The settlements are so numerous, and the Indian agencies so large, that there is nobody to prevent the Indians doing whatsoever they like.[24]

Eventually[when?] the potlatch law, as it became known, was amended to be more inclusive and address technicalities that had led to dismissals of prosecutions by the court. Legislation included guests who participated in the ceremony. The Indigenous people were too large to police and the law too difficult to enforce. Duncan Campbell Scott convinced Parliament to change the offence from criminal to summary, which meant «the agents, as justice of the peace, could try a case, convict, and sentence».[25] Even so, except in a few small areas, the law was generally perceived as harsh and untenable. Even the Indian agents employed to enforce the legislation considered it unnecessary to prosecute, convinced instead that the potlatch would diminish as younger, educated, and more «advanced» Indians took over from the older Indians, who clung tenaciously to the custom.[26]

Persistence[edit]

The potlatch ban was repealed in 1951.[27] Sustaining the customs and culture of their ancestors, Indigenous people now openly hold potlatches to commit to the restoring of their ancestors’ ways. Potlatches now occur frequently and increasingly more over the years as families reclaim their birthright. Anthropologist Sergei Kan was invited by the Tlingit nation to attend several potlatch ceremonies between 1980 and 1987 and observed several similarities and differences between traditional and contemporary potlatch ceremonies. Kan notes that there was a language gap during the ceremonies between the older members of the nation and the younger members of the nation (age fifty and younger) due to the fact that most of the younger members of the nation do not speak the Tlingit language. Kan also notes that unlike traditional potlatches, contemporary Tlingit potlatches are no longer obligatory, resulting in only about 30% of the adult tribal members opting to participate in the ceremonies that Kan attended between 1980 and 1987. Despite these differences, Kan stated that he believed that many of the essential elements and spirit of the traditional potlatch were still present in the contemporary Tlingit ceremonies.[28]

Anthropological theory[edit]

In his book The Gift, the French ethnologist Marcel Mauss used the term potlatch to refer to a whole set of exchange practices in tribal societies characterized by «total prestations», i.e., a system of gift giving with political, religious, kinship and economic implications.[29] These societies’ economies are marked by the competitive exchange of gifts, in which gift-givers seek to out-give their competitors so as to capture important political, kinship and religious roles. Other examples of this «potlatch type» of gift economy include the Kula ring found in the Trobriand Islands.[11]: 188–208

See also[edit]

- Competitive altruism

- Conspicuous consumption

- Guy Debord, French Situationist writer on the subject of potlatch and commodity reification.

- Izikhothane

- Koha, a similar concept among the Māori

- Kula ring

- List of bibliographical materials on the potlatch

- Moka exchange, a similar concept in Papua New Guinea

- Potluck («potluck» is the older term in English, but folk etymology has derived the term «potluck» from the Native American custom of potlatch)

- Pow wow, a gathering whose name is derived from the Narragansett word for «spiritual leader»

References[edit]

- ^ a b Harkin, Michael E., 2001, Potlatch in Anthropology, International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes, eds., vol 17, pp. 11885-11889. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- ^ a b Aldona Jonaitis. Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch. University of Washington Press 1991. ISBN 978-0-295-97114-8.

- ^ Seguin, Margaret (1986) «Understanding Tsimshian ‘Potlatch.‘» In: Native Peoples: The Canadian Experience, ed. by R. Bruce Morrison and C. Roderick Wilson, pp. 473–500. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

- ^ Atleo, Richard. Tsawalk: A Nuu-chah-nulth Worldview, UBC Press; New Ed edition (February 28, 2005). ISBN 978-0-7748-1085-2

- ^ Matthews, Major J. S. (1955). Conversations with Khahtsahlano 1932–1954. pp. 190, 266, 267. ASIN B0007K39O2. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ Clutesi, George (May 1969). Potlatch (2 ed.). Victoria, BC: The Morriss Printing Company.

- ^ Davidson, Sara Florence (2018). Potlatch as Pedagogy (1 ed.). Winnipeg, Manitoba: Portage and Main. ISBN 978-1-55379-773-9.

- ^ Swanton, John R (1905). Contributions to the Ethnologies of the Haida (2 ed.). New York: EJ Brtill, Leiden, and GE Stechert. ISBN 0-404-58105-6.

- ^ «Constitution of the Haida Nation» (PDF). Council of the Haida Nation. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ «Haida Accord» (PDF). Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Graeber, David (2001). Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of our own Dreams. New York: Palgrave.

- ^ Barnett, H. G. (1938). «The Nature of the Potlatch». American Anthropologist. 40 (3): 349–358. doi:10.1525/aa.1938.40.3.02a00010.

- ^ Snyder, Sally (April 1975). «Quest for the Sacred in Northern Puget Sound: An Interpretation of Potlatch». Ethnology. 14 (2): 149–161. doi:10.2307/3773086. JSTOR 3773086.

- ^ Dorothy O. Johansen, Empire of the Columbia: A History of the Pacific Northwest, 2nd ed., (New York: Harper & Row, 1967), pp. 7–8.

- ^ McFeat, Tom (1978). Indians of the North Pacific Coast. McGill-Queen’s University Press. pp. 72–80.

- ^ Franz Boas, «The Indians of British Columbia,» The Popular Science Monthly, March 1888 (vol. 32), p. 631.

- ^ Rosman, Abraham (1972). «The Potlatch: A Structural Analysis 1». American Anthropologist. 74 (3): 658–671. doi:10.1525/aa.1972.74.3.02a00280.

- ^ (1) Boyd (2) Cole & Chaikin

- ^ Smith, Gerad (2020). Ethnoarchaeology of the Middle Tanana Valley, Alaska.

- ^ An Act further to amend «The Indian Act, 1880,» S.C. 1884 (47 Vict.), c. 27, s. 3.

- ^ G. M. Sproat, quoted in Douglas Cole and Ira Chaikin, An Iron Hand upon the People: The Law against the Potlatch on the Northwest Coast (Vancouver and Toronto 1990), 15

- ^ Robin Fisher, Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774–1890, Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press, 1977, 207.

- ^ An Act further to amend «The Indian Act, 1880,» S.C. 1884 (47 Vict.), c. 27, s. 3. Reproduced in n.41, Bell, Catherine (2008). «Recovering from Colonization: Perspectives of Community Members on Protection and Repatriation of Kwakwaka’wakw Cultural Heritage». In Bell, Catherine; Val Napoleon (eds.). First Nations Cultural Heritage and Law: Case Studies, Voices, and Perspectives. Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-7748-1462-1. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ Franz Boas, «The Indians of British Columbia,» The Popular Science Monthly, March 1888 (vol. 32), p. 636.

- ^ Aldona Jonaitis, Chiefly Feasts: the Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch, Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1991, 159.

- ^ Douglas Cole and Ira Chaikin, An Iron Hand upon the People: The Law against the Potlatch on the Northwest Coast (Vancouver and Toronto 1990), Conclusion

- ^ Gadacz, René R. «Potlatch». The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ Kan, Sergei (1989). «Cohorts, Generations, and their Culture: The Tlingit Potlatch in the 1980s». Anthropos: International Review of Anthropology and Linguistics. 84: 405–422.

- ^ Godelier, Maurice (1996). The Enigma of the Gift. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. pp. 147–61.

External links[edit]

- U’mista Museum of potlatch artifacts.

- Potlatch An exhibition from the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Oliver S. Van Olinda Photographs A collection of photographs depicting life on Vashon Island, Whidbey Island, Seattle and other communities around Puget Sound, Washington, Photographs of Native American activities such as documentation of a potlatch on Whidbey Island.

- Текст

- Веб-страница

Potlatch

The word «potlatch» comes from the Chinook jargon and originally

meant «to give». In its common use among the white people and the

natives of the Northwest Coast it has taken on a very general meaning

and applied to any Indian festival at which there is feasting, or, in

connection with which property is given away. Because of this loose

and general meaning there necessarily exists a good deal of confusion

as to what is meant by the term. From the Indian’s viewpoint many

different things are meant when he uses the Chinook word in speaking

to white people, for it is the only word intelligible to them by means of

which he can refer to a considerable number of ceremonies or festivals

each having its own Indian name.

0/5000

Результаты (русский) 1: [копия]

Скопировано!

PotlatchThe word «potlatch» comes from the Chinook jargon and originallymeant «to give». In its common use among the white people and thenatives of the Northwest Coast it has taken on a very general meaningand applied to any Indian festival at which there is feasting, or, inconnection with which property is given away. Because of this looseand general meaning there necessarily exists a good deal of confusionas to what is meant by the term. From the Indian’s viewpoint manydifferent things are meant when he uses the Chinook word in speakingto white people, for it is the only word intelligible to them by means ofwhich he can refer to a considerable number of ceremonies or festivalseach having its own Indian name.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 2:[копия]

Скопировано!

Потлач

Слово «потлач» происходит от Chinook жаргона и первоначально

означало «дать». В своем общего пользования среди белых людей и

выходцев из северо-западного побережья оно приняло на очень общем смысле

и применительно к любой индийской фестиваля, на котором есть пирующего, или,

связи с которым имущество отдали. Из-за этой свободной

и общего смысла обязательно существует много

путаницы, как на то, что имеется в виду под этим термином. С точки зрения индийца многие

разные вещи в виду, когда он использует Chinook слово в разговоре

с белыми людьми, ибо это единственное слово, понятными для них, с помощью

которых он может относиться к значительному числу обрядов или фестивалей

каждый из которых имеет свой собственный Indian имя.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 3:[копия]

Скопировано!

потлач

слово «потлач» происходит от чинукский жаргон и первоначально

означает «дать».в ходе общего пользования среди белых и

уроженцы северо — западном побережье она приобрела весьма общий смысл

и применяется к какому — либо индийский фестиваль, на котором есть все, или, в связи с которым имущество

отдавать.из — за этого потерять.и общий смысл всегда существует немало путаницы

, что означает термин.с точки зрения индии многие

разные вещи имеют в виду, когда он использует слова, говоря: «чинук» для белых людей, это только слова, понятные им средства

, которыми он может сослаться на значительное число церемонии или фестивали

каждый имеет свою собственную индейское название.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Другие языки

- English

- Français

- Deutsch

- 中文(简体)

- 中文(繁体)

- 日本語

- 한국어

- Español

- Português

- Русский

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Ελληνικά

- العربية

- Polski

- Català

- ภาษาไทย

- Svenska

- Dansk

- Suomi

- Indonesia

- Tiếng Việt

- Melayu

- Norsk

- Čeština

- فارسی

Поддержка инструмент перевода: Клингонский (pIqaD), Определить язык, азербайджанский, албанский, амхарский, английский, арабский, армянский, африкаанс, баскский, белорусский, бенгальский, бирманский, болгарский, боснийский, валлийский, венгерский, вьетнамский, гавайский, галисийский, греческий, грузинский, гуджарати, датский, зулу, иврит, игбо, идиш, индонезийский, ирландский, исландский, испанский, итальянский, йоруба, казахский, каннада, каталанский, киргизский, китайский, китайский традиционный, корейский, корсиканский, креольский (Гаити), курманджи, кхмерский, кхоса, лаосский, латинский, латышский, литовский, люксембургский, македонский, малагасийский, малайский, малаялам, мальтийский, маори, маратхи, монгольский, немецкий, непальский, нидерландский, норвежский, ория, панджаби, персидский, польский, португальский, пушту, руанда, румынский, русский, самоанский, себуанский, сербский, сесото, сингальский, синдхи, словацкий, словенский, сомалийский, суахили, суданский, таджикский, тайский, тамильский, татарский, телугу, турецкий, туркменский, узбекский, уйгурский, украинский, урду, филиппинский, финский, французский, фризский, хауса, хинди, хмонг, хорватский, чева, чешский, шведский, шона, шотландский (гэльский), эсперанто, эстонский, яванский, японский, Язык перевода.

- это что шутка?????

- Dear Friend,Thank you for shopping with

- Юля молодец, выглядит отлично для начала

- Я не собираюсь переводить эту статью м

- well whats up?

- “So,” John says, trying to rearrange his

- Departure from WarehouseArrival at Wareh

- “So,” John says, trying to rearrange his

- Будешь хорошо учиться

- Я знал, что про меня забыли.

- I can see Ann.And his is your dog?

- K, yea i had to do the cc part too =( th

- verfügen

- ok wait

- Estaba enferma mucho tiempo.

- 1. In what state was Samuel Clemens born

- Где она живёт ? Она из Италии

- У них есть торт ? Да, у них есть большой

- она коричневого цветапорода пикинестима

- А Мери уже сообщили?

- Проверяйте. Я жду свой заказ

- Severe floods often happen in spring and

- это что шутка?????

- Dear Friend,Thank you for shopping with

в поддержку ответа Марка

Explanation:

Фестиваль «живых звезд».

Недалеко от нас, вблизи городка Ранкокас, расположена резервация индейцев племени поухатан, которые называют себя «живыми звездами». Два раза в год там устраивают большой праздник — фестиваль, на который съезжаются индейцы из всех америк — южной, центральной, северной. Зрелище — красочное, забавное и познавательное. Можно послушать рассказы об особенностях жизни в индейских деревнях (которых здесь уже не осталось), пострелять из лука, раскраситься «по-индейски», прикупить перьев или других индейских украшений, поглазеть на живых овнов и бизонов, а также посмотреть танцы (и даже поучаствовать в них), трюки с дрессированными птицами или не дресированными крокодилами, послушать песни, поесть индейской еды…

Potlatch

1. потлач, ритуальное празднество с приношением даров (у американских индейцев).

2. (амер. канад. разг.) празднование, сборище гостей, праздник с раздачей подарков

http://deja-vu4.narod.ru/Potlach.htm

http://www.kinderino.ru/znania/mirchel/prazdn_zim.html

The Kwakiutl (kwakwaka’wakw) continue the practice of potlatch. Illustrated here is Wawadit’la in Thunderbird Park, Victoria, British Columbia, (aka Mungo Martin House) a Kwakwaka‘wakw «big house» built by Chief Mungo Martin in 1953. Very wealthy, prominent hosts would have a longhouse specifically for potlatching and for housing guests.

The ceremonial feast called a potlatch, practiced among a diverse group of Northwest Coast Indians as an integral part of indigenous culture, had numerous social implications. The Kwakiutl, of the Canadian Pacific Northwest, are the main group that still practices the potlatch custom. Although there were variants in the external form of the ceremony as conducted by each tribe, the general form was that of a feast in which gifts were distributed. The size of the gathering reflected the social status of the host, and the nature of the gifts given depended on the status of the recipients. Potlatches were generally held to commemorate significant events in the life of the host, such as marriage, birth of a child, death, or the assumption of a new social position. Potlatches could also be conducted for apparently trivial reasons, because the true reason was to validate the host’s social status. Such ceremonies, while reduced to external materialistic form in Western society, are important in maintaining stable social relationships as well as celebrating significant life events. Fortunately, through studies by anthropologists, the understanding and practice of such customs has not been lost.

Definition

The name Potlatch is derived from Chinook Jargon, a homonym having nothing to do with «pot» or «latch.» The homonym comes from Coast Salish Lushootseed potlatching, spelled xwsalikw, from xwɐš, meaning to «throw, broadcast, distribute goods,» related to pús(u), «throw through the air, throw at,» relating to the giving of gifts and food at such ceremonies.[1] Even though there are variant names between each of the practicing tribes, the ceremony itself is actually quite uniformly practiced. The English term «potluck» is erroneously said to derive from «potlatch» due to its use in the American term «potluck dinner;» it is actually a portmanteau of «pot» and «luck.»

The Traditional Ceremony

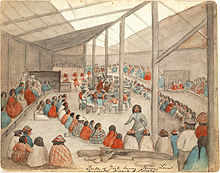

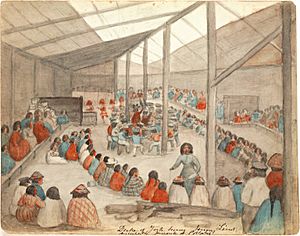

Indian visitors attending Potlatch at Kok-wol-too village, Chilkat River, Alaska

Originally, the potlatch was held by native tribes on the Pacific Northwest coast of the United States and the Canadian province of British Columbia, such as the Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit, Tsimshian, Coast Salish, and Kwakiutl (Kwakwaka‘wakw). The potlatch took the form of a ceremonial feast traditionally featuring seal meat or salmon to commemorate an important event, such as the death of a high-status person, but was expanded over time to celebrate events in the life cycle of the host family, such as the birth of a child, the start of a daughter’s menstrual cycle, and even the marriage of children.

Through the potlatch, hierarchical relations within and between groups were observed and reinforced through the exchange of gifts, dance performances, and other ceremonies. The host family demonstrated their wealth and prominence through giving away their possessions and thus prompting prominent participants to reciprocate when they held their own potlatches. Before the arrival of the Europeans, gifts included storable food such as dried oolichan (candlefish) or oolichan oil, canoes, and slaves among the very wealthy, but otherwise not income-generating assets such as resource rights. Some potlatch celebrations were locally centered, usually thrown by those lower in social status, while those high in the hierarchical social scheme would use the feasts in both a celebratory and diplomatic function, including neighboring tribal leaders. Some groups, such as the Kwakiutl, used the potlatch as an arena in which highly competitive contests of status took place. In some rare cases, goods were actually destroyed after being received.[2]

Potlatch and The Europeans

The conquest of America by the Europeans drastically changed the nature of the potlatch. The influx of manufactured trade goods, such as blankets and sheet copper, from explorers and settlers into the Pacific Northwest caused inflation in the potlatch in the late eighteenth and earlier nineteenth centuries, leading to an imbalance in the gifts given and received. Some people engaged in the ceremony purely to acquire the most material wealth, leading not only to a disintegration in the cultural value of the custom, but a basic breakdown in social relations and structure, causing violent and criminal acts among native groups.[3] Even though the settlers had, at first contact, found the potlatch interesting, their misunderstanding of the ritual and the negative effects their contact had on it caused such negative consequences that potlatching was made illegal in Canada in 1884 and in the United States in the late nineteenth century, largely at the urging of missionaries and government agents who considered it wasteful, unproductive and injurious to the practitioners.[4]

Despite the ban, potlatching continued in secret for decades. Numerous tribes petitioned the government to remove the law against a custom that they saw as no worse than Christmas, when friends were feasted and gifts were exchanged. As the potlatch became less of an issue in the twentieth century, the ban was dropped, in the United States in 1934 and in Canada in 1951.

Contemporary Potlatch

Small totem outside Saik’uz First Nation Potlatch House

A tribe well known to still practice the potlatch today is the Kwakiutl (kwakwaka’wakw). The Kwakiutl have long been studied by ethnologists and anthropologists, particularly Franz Boas. When the ceremony died out in the beginning of the twentieth century, most of the cultural artifacts were preserved by scholars. These objects helped produce not only more in-depth scholarly work on these rituals, but also encouraged some scholars to actively seek to re-establish the ritual in the surviving tribe members. Consequently, the Kwakiutl once again began the practice.

Today, the potlatch is different from its original form, incorporating numerous other cultural rituals in a mosaic of preserved and modified culture specific to the Kwakiutl.

The Saik’uz (Stoney Creek) First Nation built a Potlatch House in the years 1995-1996 on the shore of Nulki Lake. The potlatch house is a big log building which can hold 200-250 people, big enough for holding weddings, dances, meetings, and education courses. The Potlatch house is more than building, as it serves important ceremonial purposes including governance, economy, social status, and other spiritual practices.

Notes

- ↑ Bates, Dawn; Hess, Thom; and Hilbert, VI, Lushootseed Dictionary. Seattle and London: University of Washington. 1994. ISBN 0295973234

- ↑ Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Gifting and Feasting in the Northwest Coastal Potlatch. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Potlatch. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ↑ An Act further to amend «The Indian Act, 1880,» S.C. 1884 (47 Vict.), c. 27, s. 3.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adams, John W. The Gitksan Potlatch: Population Flux, Resource Ownership and Reciprocity. Toronto: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston of Canada. 1973.

- Barnett, Homer G. «The Nature of the Potlatch.» American Anthropologist. vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 349-358. 1938.

- Beck, Mary Giraudo. Potlatch: Native Ceremony and Myth on the Northwest Coast. Alaska Northwest Books. 1993. ISBN 0882404407

- Beynon, William. Potlatch at Gitsegukla: William Beynon’s 1945 Field Notebooks. Vancouver: UBC. 2000.

- Boas, Franz. Kwakiutl Ethnography. University of Chicago. 1975. ISBN 0226062376

- Bracken, Christopher The Potlatch Papers: A Colonial Case History. Chicago: University of Chicago. 1997.

- Cole, Douglas, and Chaikin, Ira. An Iron Hand upon the People: The Law against the Potlatch on the Northwest Coast. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. 1990. ISBN 0295970502

- Dauenhauer, Nora Marks, and Dauenhauer, Richard, eds. “Haa Tuwanáagu Yís, for Healing Our Spirit: Tlingit Oratory.” Classics of Tlingit Oral Literature. vol. 2. Seattle: University of Washington. 1990.

- Emmons, George T., and Thornton, George. The Tlingit Indians. Seattle: University of Washington. 1991.

- Kan, Sergei. Symbolic Immortality: The Tlingit Potlatch of the Nineteenth Century. Washington: Smithsonian Books. 1989. ISBN 1-56098-309-4

- Masco, Joseph. «‘It Is a Strict Law That Bids Us Dance’: Cosmologies, Colonialism, Death and Ritual Authority in the Kwakwaka’wakw Potlatch, 1849-1922.» Comparative Studies in Society and History. vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 41-75. 1995.

- Ogden, Peter Skene. «A Fur Trader.» Traits of American Indian Life and Character. San Francisco: Grabhorn. 1933.

External links

All links retrieved November 30, 2022.

- University of Washington Libraries. Oliver S. Van Olinda Photographs.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Potlatch history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Potlatch»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Last Update: Jan 03, 2023

This is a question our experts keep getting from time to time. Now, we have got the complete detailed explanation and answer for everyone, who is interested!

Asked by: Eleanore Kautzer Sr.

Score: 4.1/5

(73 votes)

Potlatch, ceremonial distribution of property and gifts to affirm or reaffirm social status, as uniquely institutionalized by the American Indians of the Northwest Pacific coast. … A potlatch was given by an heir or successor to assert and validate his newly assumed social position.

What is a potlatch and why was it banned?

As part of a policy of assimilation, the federal government banned the potlatch from 1884 to 1951 in an amendment to the Indian Act. The government and its supporters saw the ceremony as anti-Christian, reckless and wasteful of personal property.

Does potlatch mean giving?

A potlatch involves giving away or destroying wealth or valuable items in order to demonstrate a leader’s wealth and power. … The word comes from the Chinook Jargon, meaning «to give away» or «a gift»; originally from the Nuu-chah-nulth word paɬaˑč, to make a ceremonial gift in a potlatch.

What is the main event of a potlatch?

The main event of the potlatch, however, was the gift giving. The host presented gifts to each guest based on social rank. This means that more important people generally received larger gifts. People held potlatches for many different reasons.

What is potlatch and example?

In a more general sense, to potlatch can signify giving or holding a feast, wild party, or both! Example: During the potlatch, the chieftain gave a speech to thank all of his guests. Example: We held a crazy potlatch for my sister’s 16th birthday.

32 related questions found

What is the best definition of potlatch?

Potlatch, ceremonial distribution of property and gifts to affirm or reaffirm social status, as uniquely institutionalized by the American Indians of the Northwest Pacific coast. The potlatch reached its most elaborate development among the southern Kwakiutl from 1849 to 1925.

What is the difference between potluck and potlatch?

is that potluck is (dated) a meal, especially one offered to a guest, consisting of whatever is available while potlatch is a ceremony amongst certain native american peoples of the pacific northwest in which gifts are bestowed upon guests and personal property is destroyed in a show of wealth and generosity.

Do the Kwakiutl still exist?

The Kwakiutl people are indigenous (native) North Americans who live mostly along the coasts of British Columbia, which is located in the northwest corner of Canada. Today, there are about 5,500 Kwakiutls living here on the tribe’s own reserve, which is land specially designated for Native American tribes.

Where did potlatch come from?

The word «potlatch» means «to give» and comes from a trade jargon, Chinook, formerly used along the Pacific coast of Canada. Guests witnessing the event are given gifts. The more gifts given, the higher the status achieved by the potlatch host.

Does potluck come from potlatch?

No. The words are similar but not actually related. Potluck is literally pot+luck. It comes from the European tradition of keeping leftover food warm in case you get unexpected guests.

What is the difference between a teepee a pueblo and a longhouse?

Teepees were easy to dismantle and take to another location. Furs and hides were used to make the walls of a teepee weather-proof. Longhouses were built by the natives in the northeast part of the continent. The walls and roof of a longhouse was made of pieces of overlapping bark.

What was the purpose of a potlatch quizlet?

A potlatch is a gift-giving feast practiced by the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada and the United States. It is their main economic system. This is a form of competitive reciprocity in which hosts demonstrate their wealth and prominence by giving away goods; they become a social weapon.

What was the White Paper supposed to do?

The policy was intended to abolish previous legal documents relating to Indigenous peoples in Canada (specifically, the Indian Act.) It also aimed to eliminate treaties and assimilate all “Indians” fully into the Canadian state.

What was the impact of the potlatch ban?

Exclusion from leadership. The potlatch ban’s lingering effects can also be seen in the exclusion of many First Nations women from leadership positions in communities, says one Indigenous author and activist. «Prior to treaty, women were the ones that held the ceremonies. They were the doctors and the healers.

What did the Pacific Northwest believe in?

Pacific Northwest religion is animistic, meaning that the people traditionally believe in the existence of spirits and souls in all living, and in some non-living, objects. While these beliefs are acted out in ceremony and ritual, they also find constant expression in everyday life.

How many Kwakiutl are there?

The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw (IPA: [ˈkʷakʷəkʲəʔwakʷ]), also known as the Kwakiutl (/ˈkwɑːkjʊtəl/; «Kwakʼwala-speaking peoples») are Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Their current population, according to a 2016 census, is 3,665.

What does Kwakiutl house look like?

What were Kwakiutl homes like in the past? The Kwakiutls lived in coastal villages of rectangular cedar-plank houses with bark roofs. Usually these houses were large (up to 100 feet long) and each one housed several familes from the same clan (as many as 50 people.)

What food did the Kwakiutl eat?

The Kwakiutl hunted in both the rivers and the forests. They ate beaver, deer, rabbit, and fish. Caribou was a major source of food. They also used the skins, antlers, and bones.

Why do they call it potluck?

The word pot-luck appears in the 16th century English work of Thomas Nashe, and used to mean «food provided for an unexpected or uninvited guest, the luck of the pot.» The modern execution of a «communal meal, where guests bring their own food,» most likely originated in the 1930s during the Depression.

Who invented potlucks?

Potlucks, as Americans know them today, are believed to have originated in the 1860s, when Lutheran and Scandinavian settlers in the Minnesota prairies would gather to exchange different seeds and crops.

What part of speech is Potlatch?

British Dictionary definitions for potlatch

potlatch. / (ˈpɒtˌlætʃ) / noun. anthropol a competitive ceremonial activity among certain North American Indians, esp the Kwakiutl, involving a lavish distribution of gifts and the destruction of property to emphasize the wealth and status of the chief or clan.

What does the word Kivas mean?

/ (ˈkiːvə) / noun. a large underground or partly underground room in a Pueblo Indian village, used chiefly for religious ceremonies.

What stratagem means?

1a : an artifice or trick in war for deceiving and outwitting the enemy. b : a cleverly contrived trick or scheme for gaining an end. 2 : skill in ruses or trickery.

What does Wampum mean?

1 : beads of polished shells strung in strands, belts, or sashes and used by North American Indians as money, ceremonial pledges, and ornaments. 2 dated, informal : money.

For other uses, see Potlatch (disambiguation).

The Kwakwaka’wakw continue the practice of potlatch. Illustrated here is Wawadit’la in Thunderbird Park, Victoria, BC, a big house built by Chief Mungo Martin in 1953. Wealthy, prominent hosts would have a longhouse specifically for potlatching and for housing guests.

A potlatch is a gift-giving feast practiced by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada and the United States, among whom it is traditionally the primary governmental institution, legislative body, and economic system. This includes the Heiltsuk, Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit, Makah, Tsimshian, Nuu-chah-nulth, Kwakwaka’wakw, and Coast Salish cultures. Potlatches are also a common feature of the peoples of the Interior and of the Subarctic adjoining the Northwest Coast, although mostly without the elaborate ritual and gift-giving economy of the coastal peoples (see Athabaskan potlatch).

A potlatch involves giving away or destroying wealth or valuable items in order to demonstrate a leader’s wealth and power. Potlatches are also focused on the reaffirmation of family, clan, and international connections, and the human connection with the supernatural world. Legal proceedings may include namings, business negotiations and transactions, marriages, divorces, deaths, end of mourning, transfers of physical and especially intellectual property, adoptions, initiations, treaty proceedings, monument commemorations, and honouring of the ancestors. Potlatch also serves as a strict resource management regime, where coastal peoples discuss, negotiate, and affirm rights to and uses of specific territories and resources. Potlatches often involve music, dancing, singing, storytelling, making speeches, and often joking and games. The honouring of the supernatural and the recitation of oral histories are a central part of many potlatches.

Potlatches were historically criminalized by the Government of Canada, with Indigenous nations continuing the tradition underground despite the risk of government reprisals including mandatory jail sentences of at least two months; the practice has been studied by many anthropologists. Since the practice was decriminalized in 1951, the potlatch has re-emerged in some communities. In many it is still the bedrock of Indigenous governance, as in the Haida Nation, which has rooted its democracy in potlatch law.

The word comes from the Chinook Jargon, meaning «to give away» or «a gift»; originally from the Nuu-chah-nulth word paɬaˑč, to make a ceremonial gift in a potlatch.

Contents

- Overview

- History

- Potlatch ban

- Persistence

- Anthropological theory

Overview

Speaker Figure, 19th century, Brooklyn Museum, the figure represents a speaker at a potlatch. An orator standing behind the figure would have spoken through its mouth, announcing the names of arriving guests.

- N.B. This overview concerns the Kwakwaka’wakw potlatch. Potlatch traditions and formalities and kinship systems in other cultures of the region differ, often substantially.

A potlatch was held on the occasion of births, deaths, adoptions, weddings, and other major events. Typically the potlatch was practiced more in the winter seasons as historically the warmer months were for procuring wealth for the family, clan, or village, then coming home and sharing that with neighbors and friends. The event was hosted by a numaym, or ‘House’, in Kwakwaka’wakw culture. A numaym was a complex cognatic kin group usually headed by aristocrats, but including commoners and occasional slaves. It had about one hundred members and several would be grouped together into a nation. The House drew its identity from its ancestral founder, usually a mythical animal who descended to earth and removed his animal mask, thus becoming human. The mask became a family heirloom passed from father to son along with the name of the ancestor himself. This made him the leader of the numaym, considered the living incarnation of the founder.

Only rich people could host a potlatch. Tribal slaves were not allowed to attend a potlatch as a host or a guest. In some instances, it was possible to have multiple hosts at one potlatch ceremony (although when this occurred the hosts generally tended to be from the same family). If a member of a nation had suffered an injury or indignity, hosting a potlatch could help to heal their tarnished reputation (or «cover his shame», as anthropologist H. G. Barnett worded it). The potlatch was the occasion on which titles associated with masks and other objects were «fastened on» to a new office holder. Two kinds of titles were transferred on these occasions. Firstly, each numaym had a number of named positions of ranked «seats» (which gave them a seat at potlatches) transferred within itself. These ranked titles granted rights to hunting, fishing and berrying territories. Secondly, there were a number of titles that would be passed between numayma, usually to in-laws, which included feast names that gave one a role in the Winter Ceremonial. Aristocrats felt safe giving these titles to their out-marrying daughter’s children because this daughter and her children would later be rejoined with her natal numaym and the titles returned with them. Any one individual might have several «seats» which allowed them to sit, in rank order, according to their title, as the host displayed and distributed wealth and made speeches. Besides the transfer of titles at a potlatch, the event was given «weight» by the distribution of other less important objects such as Chilkat blankets, animal skins (later Hudson Bay blankets) and ornamental «coppers». It is the distribution of large numbers of Hudson Bay blankets, and the destruction of valued coppers that first drew government attention (and censure) to the potlatch. On occasion, preserved food was also given as a gift during a potlatch ceremony. Gifts known as sta-bigs consisted of preserved food that was wrapped in a mat or contained in a storage basket.

Dorothy Johansen describes the dynamic: «In the potlatch, the host in effect challenged a guest chieftain to exceed him in his ‘power’ to give away or to destroy goods. If the guest did not return 100 percent on the gifts received and destroy even more wealth in a bigger and better bonfire, he and his people lost face and so his ‘power’ was diminished.» Hierarchical relations within and between clans, villages, and nations, were observed and reinforced through the distribution or sometimes destruction of wealth, dance performances, and other ceremonies. The status of any given family is raised not by who has the most resources, but by who distributes the most resources. The hosts demonstrate their wealth and prominence through giving away goods.

Potlatch ceremonies were also used as coming-of-age rituals. When children were born, they would be given their first name at the time of their birth (which was usually associated with the location of their birthplace). About a year later, the child’s family would hold a potlatch and give gifts to the guests in attendance on behalf of the child. During this potlatch, the family would give the child their second name. Once the child reached about 12 years of age, they were expected to hold a potlatch of their own by giving out small gifts that they had collected to their family and people, at which point they would be able to receive their third name.

For some cultures, such as Kwakwaka’wakw, elaborate and theatrical dances are performed reflecting the hosts’ genealogy and cultural wealth. Many of these dances are also sacred ceremonies of secret societies like the hamatsa, or display of family origin from supernatural creatures such as the dzunukwa.

Edward Curtis photo of a Kwakwaka’wakw potlatch with dancers and singers

Chief O’wax̱a̱laga̱lis of the Kwagu’ł describes the potlatch in his famous speech to anthropologist Franz Boas,

We will dance when our laws command us to dance, we will feast when our hearts desire to feast. Do we ask the white man, ‘Do as the Indian does’? No, we do not. Why, then, will you ask us, ‘Do as the white man does’? It is a strict law that bids us to dance. It is a strict law that bids us to distribute our property among our friends and neighbors. It is a good law. Let the white man observe his law; we shall observe ours. And now, if you are come to forbid us to dance, begone; if not, you will be welcome to us.

It is important to note the differences and uniqueness among the different cultural groups and nations along the coast. Each nation, community, and sometimes clan has its own way of practicing the potlatch with diverse presentation and meaning. The Tlingit and Kwakiutl nations of the Pacific Northwest, for example, held potlatch ceremonies for different occasions. The Tlingit potlatches occurred for succession (the granting of tribal titles or land) and funerals. The Kwakiutl potlatches, on the other hand, occurred for marriages and incorporating new people into the nation (i.e., the birth of a new member of the nation.) The potlatch, as an overarching term, is quite general, since some cultures have many words in their language for various specific types of gatherings. It is important to keep this variation in mind as most of our detailed knowledge of the potlatch was acquired from the Kwakwaka’wakw around Fort Rupert on Vancouver Island in the period 1849 to 1925, a period of great social transition in which many features became exacerbated in reaction to British colonialism.

History

Before the arrival of the Europeans, gifts included storable food (oolichan, or candlefish, oil or dried food), canoes, slaves, and ornamental «coppers» among aristocrats, but not resource-generating assets such as hunting, fishing and berrying territories. Coppers were sheets of beaten copper, shield-like in appearance; they were about two feet long, wider on top, cruciform frame and schematic face on the top half. None of the copper used was ever of Indigenous metal. A copper was considered the equivalent of a slave. They were only ever owned by individual aristocrats, and never by numaym, hence could circulate between groups. Coppers began to be produced in large numbers after the colonization of Vancouver Island in 1849 when war and slavery were ended.

Example of an ornamental copper used at a potlatch

The arrival of Europeans resulted in the introduction of numerous diseases against which Indigenous peoples had no immunity, resulting in a massive population decline. Competition for the fixed number of potlatch titles grew as commoners began to seek titles from which they had previously been excluded by making their own remote or dubious claims validated by a potlatch. Aristocrats increased the size of their gifts in order to retain their titles and maintain social hierarchy. This resulted in massive inflation in gifting made possible by the introduction of mass-produced trade goods in the late 18th and earlier 19th centuries. Archaeological evidence for the potlatching ceremony is suggested from the ~1,000 year-old Pickupsticks site in interior Alaska.

Potlatch ban

Main page: Potlatch Ban

Potlatching was made illegal in Canada in 1884 in an amendment to the Indian Act, largely at the urging of missionaries and government agents who considered it «a worse than useless custom» that was seen as wasteful, unproductive, and contrary to ‘civilized values’ of accumulation. The potlatch was seen as a key target in assimilation policies and agendas. Missionary William Duncan wrote in 1875 that the potlatch was «by far the most formidable of all obstacles in the way of Indians becoming Christians, or even civilized». Thus in 1884, the Indian Act was revised to include clauses banning the Potlatch and making it illegal to practice. Section 3 of the Act read,

Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the «Potlatch» or the Indian dance known as the «Tamanawas» is guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be liable to imprisonment for a term not more than six nor less than two months in any gaol or other place of confinement; and, any Indian or other person who encourages, either directly or indirectly, an Indian or Indians to get up such a festival or dance, or to celebrate the same, or who shall assist in the celebration of same is guilty of a like offence, and shall be liable to the same punishment.

In 1888, the anthropologist Franz Boas described the potlatch ban as a failure:

The second reason for the discontent among the Indians is a law that was passed, some time ago, forbidding the celebrations of festivals. The so-called potlatch of all these tribes hinders the single families from accumulating wealth. It is the great desire of every chief and even of every man to collect a large amount of property, and then to give a great potlatch, a feast in which all is distributed among his friends, and, if possible, among the neighboring tribes. These feasts are so closely connected with the religious ideas of the natives, and regulate their mode of life to such an extent, that the Christian tribes near Victoria have not given them up. Every present received at a potlatch has to be returned at another potlatch, and a man who would not give his feast in due time would be considered as not paying his debts. Therefore the law is not a good one, and can not be enforced without causing general discontent. Besides, the Government is unable to enforce it. The settlements are so numerous, and the Indian agencies so large, that there is nobody to prevent the Indians doing whatsoever they like.

Eventually the potlatch law, as it became known, was amended to be more inclusive and address technicalities that had led to dismissals of prosecutions by the court. Legislation included guests who participated in the ceremony. The Indigenous people were too large to police and the law too difficult to enforce. Duncan Campbell Scott convinced Parliament to change the offence from criminal to summary, which meant «the agents, as justice of the peace, could try a case, convict, and sentence». Even so, except in a few small areas, the law was generally perceived as harsh and untenable. Even the Indian agents employed to enforce the legislation considered it unnecessary to prosecute, convinced instead that the potlatch would diminish as younger, educated, and more «advanced» Indians took over from the older Indians, who clung tenaciously to the custom.

Persistence

The potlatch ban was repealed in 1951. Sustaining the customs and culture of their ancestors, Indigenous people now openly hold potlatches to commit to the restoring of their ancestors’ ways. Potlatches now occur frequently and increasingly more over the years as families reclaim their birthright. Anthropologist Sergei Kan was invited by the Tlingit nation to attend several potlatch ceremonies between 1980 and 1987 and observed several similarities and differences between traditional and contemporary potlatch ceremonies. Kan notes that there was a language gap during the ceremonies between the older members of the nation and the younger members of the nation (age fifty and younger) due to the fact that most of the younger members of the nation do not speak the Tlingit language. Kan also notes that unlike traditional potlatches, contemporary Tlingit potlatches are no longer obligatory, resulting in only about 30% of the adult tribal members opting to participate in the ceremonies that Kan attended between 1980 and 1987. Despite these differences, Kan stated that he believed that many of the essential elements and spirit of the traditional potlatch were still present in the contemporary Tlingit ceremonies.

Anthropological theory

In his book The Gift, the French ethnologist, Marcel Mauss used the term potlatch to refer to a whole set of exchange practices in tribal societies characterized by «total prestations», i.e., a system of gift giving with political, religious, kinship and economic implications. These societies’ economies are marked by the competitive exchange of gifts, in which gift-givers seek to out-give their competitors so as to capture important political, kinship and religious roles. Other examples of this «potlatch type» of gift economy include the Kula ring found in the Trobriand Islands.

All content from Kiddle encyclopedia articles (including the article images and facts) can be freely used under Attribution-ShareAlike license, unless stated otherwise. Cite this article:

Potlatch Facts for Kids. Kiddle Encyclopedia.

A potlatch [Potlatch. Oxford English Dictionary. [http://dictionary.oed.com/cgi/entry/50185464 Retrieved on April 26, 2007] .] [Potlatch. Dictionary.com. [http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/potlatch Retrieved on April 26, 2007] .] [Aldona Jonaitis. «Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch». U. Washington Press 1991. ISBN 978-0295971148.] is a festival ceremony practiced by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast in North America, along Pacific Northwest coast of the United States and the Canadian province of British Columbia. This includes Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit, Tsimshian [Seguin, Margaret (1986) «Understanding Tsimshian ‘Potlatch.'» In: Native Peoples: The Canadian Experience, ed. by R. Bruce Morrison and C. Roderick Wilson, pp. 473-500. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.] , Nuu-chah-nulth, [Atleo, Richard. «Tsawalk: A Nuu-chah-nulth Worldview», UBC Press; New Ed edition (February 28, 2005). ISBN 978-0774810852] Kwakwaka’wakw [Aldona Jonaitis. «Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch». U. Washington Press 1991. ISBN 978-0295971148.] and Coast Salish [Mathews, Major J.S. Conversations with Khahtsahlano 1932-1954, Out of Print, 1955. ASIN: B0007K39O2. p190, 266, 267.] cultures. The word comes from the Chinook Jargon, meaning «to give away» or «a gift». It is a vital part of indigenous cultures of the Pacific Northwest. It went through a history of rigorous ban by the Canadian government, and has been the study of many anthropologists.

About

of wealth.

During the event, different events take place, like either singing and dances, sometimes with masks or regalia, the barter of wealth through gifts, such as dried foods, sugar, flour, or other material things, and sometimes money. For many potlatches, spiritual ceremonies take place for different occasions. This is either through material wealth like foods and goods or immaterial things like songs, dances and such. For some cultures, like Kwakwaka’wakw, elaborate and theatrical dances are performed reflecting the hosts genealogy and cultural wealth they possess. Many of these dances are also sacred ceremonies of secret societies like the hamatsa, or display of family origin from supernatural creatures like the dzunukwa. Typically the potlatching is practiced more in the winter seasons as historically the warmer months were for procuring wealth for the family, clan, or village, then coming home and sharing that with neighbors and friends.

Within it, hierarchical relations within and between clans, villages, and nations, are observed and reinforced through the distribution or sometimes destruction of wealth, dance performances, and other ceremonies. The status of any given family is raised not by who has the most resources, but by who distributes the most resources. The hosts demonstrate their wealth and prominence through giving away goods. Chief O’wax̱a̱laga̱lis of the Kwagu’ł describes the potlatch in his famous speech to anthropologist Franz Boas, «We will dance when our laws command us to dance, and we will feast when our hearts desire to feast. Do we ask the white man, ‘Do as the Indian does?’ It is a strict law that bids us dance. It is a strict law that bids us distribute our property among our friends and neighbors. It is a good law. Let the white man observe his law; we shall observe ours. And now, if you come to forbid us dance, be gone. If not, you will be welcome to us.»

Celebration of births, rites of passages, weddings, funerals, namings, and honoring of the deceased are some of the many forms the potlatch occurs under. Although protocol differs among the Indigenous nations, the potlatch will usually involve a feast, with music, dance, theatricality and spiritual ceremonies. The most sacred ceremonies are usually observed in the winter.

It is important to note the differences and uniqueness among the different cultural groups and nations along the coast. Each nation, tribe, and sometimes clan has its own way of practicing the potlatch so as to present a very diverse presentation and meaning. The potlatch, as an overarching term, is quite general, since some cultures have many words in their language for all different specific types of gatherings. Nonetheless, the main purpose has and still is the redistribution of wealth procured by families.

History

Before the arrival of the Europeans, gifts included storable food (oolichan [candle fish] oil or dried food), canoes, and slaves among the very wealthy, but otherwise not income-generating assets such as resource rights. The influx of manufactured trade goods such as blankets and sheet copper into the Pacific Northwest caused inflation in the potlatch in the late eighteenth and earlier nineteenth centuries. Some groups, such as the Kwakwaka’wakw, used the potlatch as an arena in which highly competitive contests of status took place. In rare cases, goods were actually destroyed after being received. The catastrophic mortalities due to introduced diseases laid many inherited ranks vacant or open to remote or dubious claim—providing they could be validated—with a suitable potlatch. [(1) Boyd (2) Cole & Chaikin]

The potlatch was a cultural practice much studied by ethnographers. «Potlatch is a festive event within a regional exchange system among tribes of the North pacific Coast of North America, including the Salish and Kwakiutl of Washington and British Columbia.»Fact|date=February 2007 Sponsors of a potlatch give away many useful items such as food, blankets, worked ornamental mediums of exchange called «coppers», and many other various items. In return, they earned prestige. To give a potlatch enhanced one’s reputation and validated social rank, the rank and requisite potlatch being proportional, both for the host and for the recipients by the gifts exchanged. Prestige increased with the lavishness of the potlatch, the value of the goods given away in it.

Potlatch ban

Potlatching was made illegal in Canada in 1885 [ An Act further to amend «The Indian Act, 1880,» S.C. 1884 (47 Vict.), c. 27, s. 3.] and the United States in the late nineteenth century, largely at the urging of missionaries and government agents who considered it «a worse than useless custom» that was seen as wasteful, unproductive which was not part of «civilized» values. [G.M. Sproat, quoted in Douglas Cole and Ira Chaikin, An Iron Hand upon the People: The Law against the Potlatch on the Northwest Coast (Vancouver and Toronto 1990), 15]

The potlatch was seen as a key target in assimilation policies and agendas. Missionary William Duncan wrote in 1875 that the potlatch was “by far the most formidable of all obstacles in the way of Indians becoming Christians, or even civilized.” [Robin Fisher, Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890, Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press, 1977, 207.] Thus in 1885, the Indian Act was revised to include clauses banning the potlatch and making it illegal to practice. The official legislation read, “Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the «Potlatch» or the Indian dance known as the «Tamanawas» is guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be liable to imprisonment for a term not more than six nor less than two months in a jail or other place of confinement; and, any Indian or other person who encourages, either directly or indirectly an Indian or Indians to get up such a festival or dance, or to celebrate the same, or who shall assist in the celebration of same is guilty of a like offence, and shall be liable to the same punishment.”

Eventually it became amended to be more inclusive as earlier discharged on technicalities. Legislation was then expanded to include guest who participated in the ceremony. The indigenous people were too large to police, and enforce. Duncan Campbell Scott convinced Parliament to change the offense from criminal to summary, which meant ‘the agents, as justice of the peace, could try a case, convict, and sentence.” [Aldona Jonaitis, Chiefly Feasts: the Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch, Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1991, 159.]

Continuation

Sustaining the customs and culture of their ancestors, indigenous people now openly hold potlatch to commit to the restoring of their ancestors’ ways. Potlatch now occur frequently and increasingly more over the years as families reclaim their birthright.

See also

*Koha, a related concept among the Māori

*Kula ring, a similar concept in the Trobriand Islands (Oceania)

*Moka, another similar concept in Papua New Guinea

*Sepik Coast exchange, yet another similar concept in Papua New Guinea

*Guy Debord, French Situationist writer on the subject of potlatch and commodity reification.

*Gift economy

References

Bibliography

External links

* [http://www.umista.ca/collections/collection.php U’mista] Museum of potlatch artifacts.

* [http://wickedsunshine.com/Projects/PotlatchLonghouse/PotlatchLonghouse-HistoricalReference.html «The Potlatch Longhouse»] (Haida potlatches and longhouses)

* [http://www.peabody.harvard.edu/potlatch/page2.html Potlatch] An exhibition from the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

* [http://www.psychohistory.com/htm/money.html Money] An analysis of Potlatch and modern versions of the same from a psychohistorical perspective. Not , but does provide references.

* [http://content.lib.washington.edu/vanolindaweb/index.html University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Oliver S. Van Olinda Photographs] A collection of 420 photographs depicting life on Vashon Island, Whidbey Island, Seattle and other communities around Puget Sound, Washington, from the 1880s through the 1930s. This collection provides a glimpse of early pioneer activities, industries and occupations, recreation, street scenes, ferries and boat traffic at the turn of the century. Also included are a few photographs of Native American activities such as documentation of a potlatch on Whidbey Island.

* [http://www.anashinteractive.com Anash Interactive] — An online destination where users create comics, write stories, watch webisodes, download podcasts, play games, read stories and comics by other members, and find out about the Tlingit people of Canada. Potlatches were practiced through out the year

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.