First time? Quick how-to.

This visual quick how-to guide shows you how to search a word, for example «handspeak».

- All

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

Search Tips and Pointers

Search/Filter: Enter a keyword in the filter/search box to see a list of available words with the «All» selection. Click on the page number if needed. Click on the blue link to look up the word. For best result, enter a partial word to see variations of the word.

Alphabetical letters: It’s useful for 1) a single-letter word (such as A, B, etc.) and 2) very short words (e.g. «to», «he», etc.) to narrow down the words and pages in the list.

For best result, enter a short word in the search box, then select the alphetical letter (and page number if needed), and click on the blue link.

Don’t forget to click «All» back when you search another word with a different initial letter.

If you cannot find (perhaps overlook) a word but you can still see a list of links, then keep looking until the links disappear! Sharpening your eye or maybe refine your alphabetical index skill.

Add a Word: This dictionary is not exhaustive; ASL signs are constantly added to the dictionary. If you don’t find a word/sign, you can send your request (only if a single link doesn’t show in the result).

Videos: The first video may be NOT the answer you’re looking for. There are several signs for different meanings, contexts, and/or variations. Browsing all the way down to the next search box is highly recommended.

Video speed: Signing too fast in the videos? See HELP in the footer.

ASL has its own grammar and structure in sentences that works differently from English. For plurals, verb inflections, word order, etc., learn grammar in the «ASL Learn» section. For search in the dictionary, use the present-time verbs and base words. If you look for «said», look up the word «say». Likewise, if you look for an adjective word, try the noun or vice versa. E.g. The ASL signs for French and France are the same. If you look for a plural word, use a singular word.

Are you a Deaf artist, author, traveler, etc. etc.?

Some of the word entries in the ASL dictionary feature Deaf stories or anecdotes, arts, photographs, quotes, etc. to educate and to inspire, and to be preserved in Deaf/ASL history, and to expose and recognize Deaf works, talents, experiences, joys and pains, and successes.

If you’re a Deaf artist, book author, or creative and would like your work to be considered for a possible mention on this website/webapp, introduce yourself and your works. Are you a Deaf mother/father, traveler, politician, teacher, etc. etc. and have an inspirational story, anecdote, or bragging rights to share — tiny or big doesn’t matter, you’re welcome to email it. Codas are also welcome.

Hearing ASL student, who might have stories or anecdotes, also are welcome to share.

ASL to English reverse dictionary

Don’t know what a sign mean? Search ASL to English reverse dictionary to find what an ASL sign means.

Vocabulary building

To start with the First 100 ASL signs for beginners, and continue with the Second 100 ASL signs, and further with the Third 100 ASL signs.

Language Building

Learning ASL words does not equate with learning the language. Learn the language beyond sign language words.

Contextual meaning: Some ASL signs in the dictionary may not mean the same in different contexts and/or ASL sentences. A meaning of a word or phrase can change in sentences and contexts. You will see some examples in video sentences.

Grammar: Many ASL words, especially verbs, in the dictionary are a «base»; be aware that many of them can be grammatically inflected within ASL sentences. Some entries have sentence examples.

Sign production (pronunciation): A change or modification of one of the parameters of the sign, such as handshape, movement, palm orientation, location, and non-manual signals (e.g. facial expressions) can change a meaning or a subtle variety of meaning. Or mispronunciation.

Variation: Some ASL signs have regional (and generational) variations across North America. Some common variations are included as much as possible, but for specifically local variations, interact with your local community to learn their local variations.

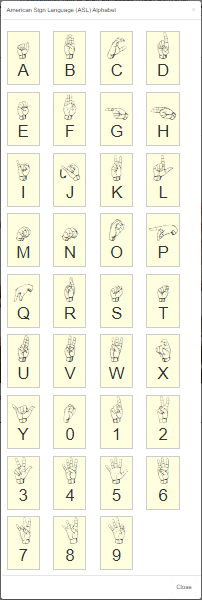

Fingerspelling: When there is no word in one language, borrowing is a loanword from another language. In sign language, manual alphabet is used to represent a word of the spoken/written language.

American Sign Language (ASL) is very much alive and indefinitely constructable as any spoken language. The best way to use ASL right is to immerse in daily language interactions and conversations with Ameslan/Deaf people (or ASLians).

Sentence building

Browse phrases and sentences to learn sign language, specifically vocabulary, grammar, and how its sentence structure works.

Sign Language Dictionary

According to the archives online, did you know that this dictionary is the oldest sign language dictonary online since 1997 (DWW which was renamed to Handspeak in 2000)?

This dictionary is not exhaustive; the ASL signs are constantly added to the dictionary. If you don’t find the word/sign, you can send your request via email. Browse the alphabetical letters or search a signed word above.

Regional variation: there may be regional variations of some ASL words across the regions of North America.

Inflection: most ASL words in the dictionary are a «base», but many of them are grammatically inflectable within ASL sentences.

Contextual meaning: These ASL signs in the dictionary may not mean the same in different contexts and/or ASL sentences. You will see some examples in video sentences.

ASL is very much alive and indefinitely constructable as any spoken language. The best way to use ASL right is to immerse in daily interaction with Deaf Ameslan people (ASLers).

For non-deaf or hard of hearing people, it is often a surprise to learn that there is more than a single sign language.

Today, there are anywhere up to 300 different types of sign language used around the world. Some are only used locally. Others are used by millions of people.

Most sign languages don’t aim to directly translate spoken words into signs you make with your hands either. Each is a true language, with its own vocabulary, grammar and syntax – often unrelated to those of oral languages spoken in the same region.

And yes, the position of the hands is important. Yet so are eyebrow position, eye position, body movement and much more besides. A little like tones in oral languages, their importance and the way they are used also vary between different sign languages.

It only takes a moment’s thought to realise that, with so much variation in oral forms of expression, wouldn’t it actually be more surprising if there was only one universal sign language?

The development of sign languages

Questions as to why there isn’t a single universal sign language only really make sense if you are picturing sign languages as a kind of helper aid “gifted” by hearing people to the deaf or hard of hearing.

However, in the real world, sign languages – almost universally – develop naturally among deaf or hard of hearing people and communities.

Even Charles Michel de l’Épée, often credited as being the “inventor” of one of the key ancestors of many modern sign languages – French Sign Language – actually overheard two deaf people using it first and then learned from them.

The origins of sign languages

Many of the sign languages spoken around the world today have their origins in:

- British Sign Language: the British manual alphabet reached a format which would be familiar to many signers today as early as 1720. However, manual alphabets had been in use in daily British life even by many hearing people for centuries previously – at least as early as 1570. This then spread through the British Commonwealth and beyond in the 19th century.

- French Sign Language: developed in the 1700s, French Sign Language was the root of American Sign Language and many other European sign languages.

- Unique origins: yet many others – including Chinese, Japanese, Indo-Pakistani and Levantine Arabic sign languages – have their own unique origins completely unrelated to French or British roots.

But by 1880, different thoughts began to take shape. In that year, plans were announced at the Second International Congress of Education of the Deaf in Milan to reduce and eventually remove sign language from classrooms in favour of lip reading and other oral-based methods.

Known as oralism, these rules – which largely prioritised the convenience of hearing people – remained essentially in effect until the 1970s.

Today, however, the various sign languages naturally developed around the world are increasingly recognised as official languages. They are the preferred method of communication for many millions of deaf and hard of hearing people worldwide.

How do sign languages compare with written or spoken languages?

Just like written or spoken languages, sign languages have their own sentence structures, grammatical organisation and vocabulary. The way the hands are positioned in relation to the body can be almost important as the sign itself, for instance.

But signed languages don’t depend on the spoken or written languages of the same region. Nor do they usually mirror or represent them.

They even have some features which many spoken languages do not. For example, some signed languages have rules for indicating a question only has a yes or no answer.

Sign languages usually develop within deaf communities. Thus, they can be quite separate from the local oral language. The usual example given is that while American English and British English are largely identical, American Sign Language and British Sign Language have many differences.

However, spoken languages and signed languages do come into contact all the time. This means that oral languages do often have some influence on signed languages.

The different types of sign languages used around the world

If you are intending to do business with or advertise your products to deaf or hard of hearing people around the world, it is important to understand the type of sign language they prefer to use.

You can easily set up sign language interpreting services between a given oral language and a given signed language – as long as you know the specific language barrier you want to bridge the gap between.

Some of the most common sign languages in the world include:

British Sign Language, Auslan and New Zealand Sign Language (BANZSL)

The way in which British Sign Language (BSL), Australian Sign Language (Auslan) and New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL) relate to each other is illustrative of the dynamic differences between even closely related signed languages.

British Sign Language, codified in British schools for the deaf in the 1700s, spread around the world as the British Empire and Commonwealth did. This included reaching both Australia and New Zealand.

Thus, New Zealand Sign Language and Auslan, Australian Sign Language, share the same manual alphabet, grammar and much of the same lexicon (that is to say the same signs) as BSL. So much so that a single phrase – BANZSL – was coined to represent them as a single language with three dialects.

1) Differences between dialects

But even within BANZSL, all three dialects of which evolved from the same roots, there are differences.

For example, a key difference between New Zealand Sign Language and the other dialects is that NZSL includes signs for Māori words. It is also heavily influenced by its Auslan roots.

Auslan is itself influenced by Irish Sign Language (which in turn, derives from a French Sign Language root).

2) Differences within dialects

Plus, within each of these dialects, there are other dialects, variants and even what might be considered accents.

Within Auslan, for instance, some dialects might include features taken from Indigenous Australian sign languages which are completely unrelated to Auslan.

Other variants are regional. Certain signs used by BSL speakers in Scotland are unlikely to be understood by BSL speakers in southern England, for instance.

Another example is the city of Manchester in England, whose BSL-speaking population often use their own signed numbering system.

3) Differences within regions

Despite the implications of the names, languages such as British Sign Language or Australian Sign Language are also not the only signed languages used in Britain or Australia.

Many Indigenous Australian groups have their own sign languages. Within the UK, while around 145 000 people have BSL as their first or preferred language, others prefer different ways of communicating.

For example, Sign-Supported English (SSE) is a signed language which uses many of the same signs as BSL but which is designed to be used in support of spoken English. Thus, it tends to follow the same grammatical rules as the oral language instead of those of BSL.

French Sign Language (LSF)

French Sign Language (LSF – Langue des Signes Française) is another origin point for many of the world’s most-used sign languages. It arose amongst the deaf community in Paris and was codified by Charles Michel de l’Épée in the 1770s.

Although de l’Epee added a whole host of extra and often overly complex rules to the existing system, he did at least popularise the idea that sign languages were actual languages – to the point they were accepted by educators up until the rise of oralism.

Today, LSF is spoken by around 100 000 people in France as their first or preferred language. It has also had a significant impact on the development of ASL, Irish Sign Language and Russian Sign Language among many others.

However, again, it would be a mistake to assume that French Sign Language is simply used everywhere French is spoken. Many French-speaking regions have their own sign languages, including:

- Canada: has LSQ (la Langue des Signes Québécois), also referred to as Quebec Sign Language or French Canadian Sign Language, in its francophone regions and ASL (American Sign Language) in its anglophone parts.

- Belgium: has Flemish Belgian Sign Language and French Belgian Sign Language.

There are also numerous regional dialects even within France. These include Southern French Language, also known as Marseilles Sign Language.

American Sign Language (ASL)

American Sign Language borrows a large number of its grammatical laws from LSF, French Sign Language. But it combines them with local signs first used in America.

Today, anywhere from 250 000 to 500 000 use ASL as their preferred or first language. This is because, as well as being widely used by deaf and hard of hearing people in the United States, the language is also used in:

- English-speaking parts of Canada

- Parts of West Africa

- Parts of South-East Asia

Irish Sign Language (ISL)

Irish Sign Language also derives from LSF, French Sign Language. There are certainly influences from the BSL spoken in nearby regions, but ISL remains its own language.

Somewhere around 5000 deaf and hard of hearing people in the Republic of Ireland, as well as some in Northern Ireland, have ISL as their first or preferred language

A dialect difference almost unique to ISL is that which once existed between male and female ISL speakers. This came about through deaf or hard of hearing Irish Catholic students who leaned in schools which operated on lines of gender segregation.

These differences are almost entirely absent from modern ISL. Yet they are one more illustration of the way signed languages can develop in different ways among different groups from the same root.

Japanese Sign Language (JSL)

It has been said that Japanese Sign Language (Nihon Shuwa, 日本手話) reflects oral Japanese more closely than British Sign Language or American Sign Language reflect spoken English.

Speakers of JSL often mouth the way Japanese characters are spoken orally to make it clear which sign they are using. This is an important distinction from languages like ASL or BSL, where gestures and facial expressions are often more important.

Somewhere around 60 000 of the 300 000 deaf or hard of hearing people in Japan use JSL and there are several regional dialects. Many of the 200 000 or more others use:

- Taiou Shuwa: Sign-Supported Speech which works in something of the same manner as Sign-Supported English.

- Chuukan Shuwa: contact sign language. These languages include both oral and manual parts. The “contact” refers to the way they develop in the space where manual and oral languages come into contact.

Chinese Sign Language (CSL or ZGS)

Chinese Sign Language (CSL, written as 中国手语 in simplified Chinese and 中國手語 in traditional Chinese) is sometimes abbreviated as ZGS because of the Hanyu Pinyin romanised name of the language, Zhōngguó Shǒuyǔ.

The History of Chinese Sign Language

Although in recent years Chinese Sign Language has started to become more accepted in China, it remains unknown how many deaf or hard of hearing in the country actually use or prefer it.

This is largely because, up until very recently, many deaf Chinese children were taught in special schools using an oralist approach. This practice was strictly encouraged for the last half-century or more.

However, throughout the time when the oralist approach was the only standard in Chinese education for the deaf, CSL was still spread through smaller schools and workshops in various communities.

Today, there are around 20 million deaf or hard of hearing people in China. It’s estimated that around 1 in 20 or possibly more use CSL.

Chinese Sign Language – a unique language

Chinese Sign Language is a language isolate, meaning it is a natural language which has no other antecedents.

The language does have some parallels with oral Chinese. For example, there are two different signs for “older brother” and “younger brother”. This mirrors the fact that there are distinct words for each in oral Chinese too, instead of a generic word for “brother”.

CSL also includes pictorial representations as part of the language. This includes gesturing the use of chopsticks as the sign for eat.

Is there a universal sign language?

Strictly speaking, yes. International Sign – sometimes referred to as Gestuno, International Sign Pidgin or International Gesture – is a theoretically universal sign language used at the Deaflympics and other international deaf events.

That said, International Sign has been criticised for drawing heavily from European and North American sign languages at the possible expense of deaf and hard of hearing people from other parts of the world.

International Sign also may not, strictly speaking, meet the requirements for being counted a true language. It has recently been argued that International Sign is more like a complex pidgin – a term often used to describe a somewhat simplified form of communication developed between groups which speak different languages – rather than a complete language in and of itself.

International Sign Language Day

International Sign Language Day takes place every year on September 23rd. If nothing else this year, it’s worth thinking a little about how signed communication really works.

The differences between the sign languages spoken around the world are just as diverse and intriguing as those between spoken languages.

Do you need to set up sign language interpreting for your physical or virtual event, appointment or business meeting?

Asian Absolute works with individuals and businesses in every industry to bridge language gaps both spoken and signed.

Let’s talk. Get a free quote with zero obligation or more information today.

Two sign language Interpreters working as a team for a school.

A sign language (also signed language) is a language which uses manual communication, body language, and lip patterns instead of sound to convey meaning—simultaneously combining hand shapes, orientation and movement of the hands, arms or body, and facial expressions to fluidly express a speaker’s thoughts. Signs often represent complete ideas, not only words. However, in addition to accepted gestures, mime, and hand signs, sign language often includes finger spelling, which involves the use of hand positions to represent the letters of the alphabet.

Although often misconceived of as an imitation or simplified version of oral language, linguists such as William Stokoe have found sign languages to be complex and thriving natural languages, complete with their own syntax and grammar. In fact, the complex spatial grammars of sign languages are markedly different than that of spoken language.

Sign languages have developed in circumstances where groups of people with mutually unintelligible spoken languages found a common base and were able to develop signed forms of communication. A well-known example of this is found among Plains Indians, whose lifestyle and environment was sufficiently similar despite no common base in their spoken languages, that they were able to find common symbols that were used to communicate even complex narratives among different tribes.

Sign languages commonly develop in deaf communities, which include people who are deaf or hard of hearing, friends and families of deaf people, as well as interpreters. In many cases, various signed «modes» of spoken languages have been developed, such as Signed English and Warlpiri Sign Language. Sign language differs from one region to another, just as do spoken languages, and are mutually unintelligible. Hundreds of sign languages are in use around the world and are at the core of local deaf cultures. The use of these languages has enabled the deaf to be recognized as intelligent, educable people who are capable of living life as fully and with as much value as anyone else. However, much controversy exists over whether teaching deaf children sign language is ultimately more beneficial than methods that allow them to understand oral communication, such as lip-reading, since this enables them to participate more directly and fully in the wider society. Nonetheless, for those people who remain unable to produce or understand oral language, sign language provides a way to communicate within their society as full human beings with a clear cultural identity.

History and development of sign language

On the whole, deaf sign languages are independent of oral languages and follow their own paths of development, even in situations where there may be a common spoken language. Because they developed on their own, British Sign Language and American Sign Language are quite different and mutually unintelligible, even though the hearing people of Britain and America share the same oral language. American Sign Language does have some similarities to French Sign Language, due to its early influences. When people using different signed languages meet, however, communication can be easier than when people of different spoken languages meet. This is not because sign languages are universal, but because deaf people may be more patient when communicating, and are comfortable including gesture and mime.[1]

Generally, each spoken language has a sign language counterpart because each linguistic population contains deaf members who generated a sign language. Geographical or cultural forces will isolate populations and lead to the generation of different and distinct spoken languages; the same forces operate on signed languages, therefore they tend to maintain their identities through time in roughly the same areas of influence as the local spoken languages. This occurs even though sign languages have little or no relation to the spoken languages of the lands in which they arise. There are notable exceptions to this pattern, however, as some geographic regions sharing a spoken language have multiple, unrelated signed languages. Variations within a «national» sign language can usually be correlated to the geographic location of (residential) schools for the deaf.

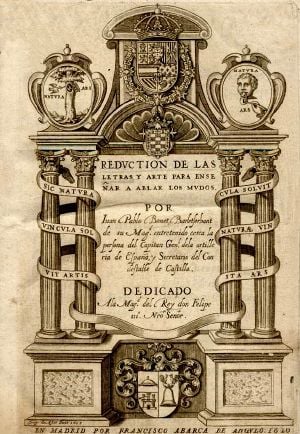

Juan Pablo Bonet, Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos (Madrid, 1620).

The written history of sign language began in the seventeenth century in Spain. In 1620, Juan Pablo Bonet published Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos (Reduction of letters and art for teaching dumb people to speak) in Madrid. It is considered the first modern treatise of phonetics and speech therapy, setting out a method of oral education for the deaf people by means of the use of manual signs in the form of a manual alphabet to improve the communication of deaf people.

From the language of signs of Bonet, Charles-Michel de l’Épée published his alphabet in the eighteenth century, which has remained basically unchanged until the present time. In 1755, Abbé de l’Épée founded the first public school for deaf children in Paris. His lessons were based upon his observations of deaf people signing with hands in the streets of Paris. Synthesized with French grammar, it evolved into the French Sign Language.

Laurent Clerc, a graduate and former teacher of the French School, went to the United States with Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet to found the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817.[2] Others followed. In 1817, Clerc and Gallaudet founded the American Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb (now the American School for the Deaf). Gallaudet’s son, Edward Miner Gallaudet, founded the first college for the deaf in 1864 in Washington, DC, which in 1986, became Gallaudet University, the only liberal arts university for the deaf in the world.

Engravings of Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos:[3]

-

A.

-

B, C, D.

-

E, F, G.

-

H, I, L.

-

M, N.

-

O, P, Q.

-

R, S, T.

-

V, X, Y, Z.

2007 Chinese Taipei Olympic Day Run in Taipei City: Deaflympics Taipei 2009 Easy Sign Language Section.

International Sign, formerly known as «Gestuno,» was created in 1973, to enhance communication among members of the deaf community throughout the world. It is an artificially constructed language and though some people are reported to use it fluently, it is more of a pidgin than a fully formed language. International Sign is used mainly at international Deaf events such as the Deaflympics and meetings of the World Federation of the Deaf.[4]

Linguistics of sign

In linguistic terms, sign languages are rich and complex, despite the common misconception that they are not «real languages.» William Stokoe started groundbreaking research into sign language in the 1960s. Together with Carl Cronenberg and Dorothy Casterline, he wrote the first sign language dictionary, A Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles.[5] It was during this time he first began to refer to sign language not just as sign language or manual communication, but as «American Sign Language,» or ASL. This ground-breaking dictionary listed signs and explained their meanings and usage, and gave a linguistic analysis of the parts of each sign. Since then, linguists have studied many sign languages and found them to have every linguistic component required to be classified as true languages.

Did you know?

Sign languages are complex and contain every linguistic component required to be classified as true languages

Sign languages are not merely pantomime, but are made of largely arbitrary signs that have no necessary visual relationship to their referent, much as most spoken language is not onomatopoeic. Nor are they a visual renditions of an oral language. They have complex grammars of their own, and can be used to discuss any topic, from the simple and concrete to the philosophical and abstract. For example, in terms of syntax, ASL shares more with spoken Japanese than it does with English.[6]

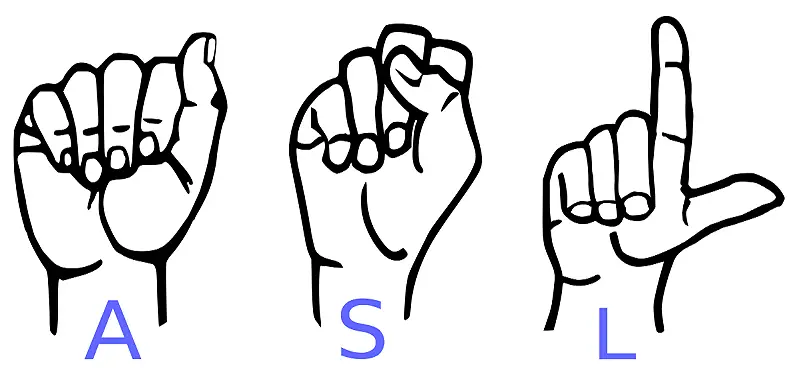

The American manual alphabet in photographs

Sign languages, like oral languages, organize elementary, meaningless units (phonemes; once called cheremes in the case of sign languages) into meaningful semantic units. The elements of a sign are Hand shape (or Handform), Orientation (or Palm Orientation), Location (or Place of Articulation), Movement, and Non-manual markers (or Facial Expression), summarized in the acronym HOLME. Signs, therefore, are not an alphabet but rather represent words or other meaningful concepts.

In addition to such signs, most sign languages also have a manual alphabet. This is used mostly for proper names and technical or specialized vocabulary. The use of fingerspelling was once taken as evidence that sign languages are simplified versions of oral languages, but it is merely one tool in complex and vibrant languages. Fingerspelling can sometimes be a source of new signs, which are called lexicalized signs.

Common linguistic features of deaf sign languages are extensive use of classifiers, a high degree of inflection, and a topic-comment syntax. Many unique linguistic features emerge from sign languages’ ability to produce meaning in different parts of the visual field simultaneously. For example, the recipient of a signed message can read meanings carried by the hands, the facial expression, and the body posture at the same time. This is in contrast to oral languages, where the sounds that comprise words are mostly sequential (tone being an exception).

Spatial grammar and simultaneity

Sign languages are able to capitalize on the unique features of the visual medium. Oral language is linear and only one sound can be made or received at a time. Sign language, instead, is visual; hence, a whole scene can be taken in at once. Information can be loaded into several channels and expressed simultaneously.

As an illustration, in English one could utter the phrase, «I drove here.» To add information about the drive, one would have to make a longer phrase or even add a second, such as, «I drove here along a winding road,» or «I drove here. It was a nice drive.» However, in American Sign Language, information about the shape of the road or the pleasing nature of the drive can be conveyed simultaneously with the verb «drive» by inflecting the motion of the hand, or by taking advantage of non-manual signals such as body posture and facial expression, at the same time that the verb «drive» is being signed. Therefore, in English the phrase «I drove here and it was very pleasant» is longer than «I drove here,» in American Sign Language the two may be the same length.

Written forms of sign languages

Sign languages are not often written, and documented written systems were not created until after the 1960s. Most deaf signers read and write the oral language of their country. However, there have been several attempts at developing scripts for sign language. These have included both «phonetic» systems, such as Hamburg Sign Language Notation System, or HamNoSys,[7] and SignWriting, which can be used for any sign language, as well as «phonemic» systems such as the one used by William Stokoe in his 1965 Dictionary of American Sign Language, which are designed for a specific language.

The phonemic systems of oral languages are primarily sequential: That is, the majority of phonemes are produced in a sequence one after another, although many languages also have non-sequential aspects such as tone. As a consequence, traditional phonemic writing systems are also sequential, with at best diacritics for non-sequential aspects such as stress and tone. Sign languages have a higher non-sequential component, with many «phonemes» produced simultaneously. For example, signs may involve fingers, hands, and face moving simultaneously, or the two hands moving in different directions. Traditional writing systems are not designed to deal with this level of complexity.

The Stokoe notation is sequential, with a conventionalized order of a symbol for the location of the sign, then one for the hand shape, and finally one (or more) for the movement. The orientation of the hand is indicated with an optional diacritic before the hand shape. When two movements occur simultaneously, they are written one atop the other; when sequential, they are written one after the other. Stokoe used letters of the Latin alphabet and Arabic numerals to indicate the handshapes used in fingerspelling, such as «A» for a closed fist, «B» for a flat hand, and «5» for a spread hand; but non-alphabetic symbols for location and movement, such as «[]» for the trunk of the body, «×» for contact, and «^» for an upward movement.

SignWriting, developed in 1974 by Valerie Sutton, is highly featural and visually iconic, both in the shapes of the characters—which are abstract pictures of the hands, face, and body—and in their spatial arrangement on the page, which does not follow a sequential order like the letters that make up written English words. Being pictographic, it is able to represent simultaneous elements in a single sign. Neither the Stokoe nor HamNoSys scripts were designed to represent facial expressions or non-manual movements, both of which SignWriting accommodates easily.

Use of signs in hearing communities

While not full languages, many elaborate systems of manual communication have developed in situations where speech is not practical or permitted, such as cloistered religious communities, scuba diving, television recording studios, loud workplaces, stock exchanges, in baseball, while hunting (by groups such as the Kalahari bushmen), or in the game Charades. In Rugby Union, the referee uses a limited but defined set of signs to communicate his/her decisions to the spectators.

On occasion, where there are enough deaf people in the area, a deaf sign language has been taken up by an entire local community. Famous examples of this include Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language in the U.S., Kata Kolok in a village in Bali, Adamorobe Sign Language in Ghana, and Yucatec Maya sign language in Mexico. In such communities, deaf people are not socially disadvantaged.

Many Australian Aboriginal sign languages arose in a context of extensive speech taboos, such as during mourning and initiation rites. They are or were especially highly developed among the Warlpiri, Warumungu, Dieri, Kaytetye, Arrernte, Warlmanpa, and are based on their respective spoken languages.

Sign language has also been used to facilitate communication among peoples of mutually intelligible languages. In the case of Chinese and Japanese, where the same body of written characters is used but with different pronunciation, communication is possible through watching the «speaker» trace the mutually understood characters on the palm of their hand.

A pidgin sign language arose among tribes of American Indians in the Great Plains region of North America. Although the languages of the Plains Indians were unrelated, their way of life and environment had many common features. They were able to find common symbols which were then used to communicate even complex narratives among different tribes. For example, the gesture of brushing long hair down the neck and shoulders signified a woman, two fingers astride the other index finger represented a person on horseback, a circle drawn against the sky meant the moon, and so forth. Unlike other sign languages developed by hearing people, it shares the spatial grammar of deaf sign languages.

Home sign

Sign systems are sometimes developed within a single family. For instance, when hearing parents with no sign language skills have a deaf child, an informal system of signs will naturally develop, unless repressed by the parents. The term for these mini-languages is home sign (sometimes homesign or kitchen sign).

Home sign arises due to the absence of any other way to communicate. Within the span of a single lifetime and without the support or feedback of a community, the child is forced to invent signals to facilitate the meeting of his or her communication needs. Although this kind of system is grossly inadequate for the intellectual development of a child and does not meet the standards linguists use to describe a complete language, it is a common occurrence.

Benefits

For deaf and hard of hearing students, there have been long standing debates regarding the teaching and use of sign language versus oral methods of communication and lip reading. Proficiency in sign language gives deaf children a sense of cultural identity, which enables them to bond with other deaf individuals. This can lead to greater self-esteem and curiosity about the world, both of which enrich the student academically and socially. Certainly, the development of sign language showed that deaf-mute children were educable, opening educational opportunities at the same level as those who hear.

Notes

- ↑ David Bar-Tzur, International Gesture:Principles and Gestures, July 13, 2002. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ↑ Loida Canlas, Laurent Clerc: Apostle to the Deaf People of the New World Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center, Gallaudet University. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ↑ Juan Pablo Bonet, Reducción de las Letras y Arte para Enseñar a Hablar a los Mudos (Editorial Cepe, 1992, ISBN 978-8478690718).

- ↑ Jolanta Lapiak, Gestuno (a.k.a International Sign Language) HandSpeak. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ↑ William C. Stokoe, Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles (Linstok Press, 1976, ISBN 978-0932130013).

- ↑ Karen Nakamura, About Japanese Sign Language Deaf Resource Library. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ↑ HamNoSys DGS Corpus. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aronoff, Mark, and Janie Rees-Miller. The Handbook of Linguistics. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2020. ISBN 978-1119302070

- Bonet, Juan Pablo. Reducción de las Letras y Arte para Enseñar a Hablar a los Mudos. Editorial Cepe, 1992. ISBN 978-8478690718

- Emmorey, Karen, Harlan L. Lane, Ursula Bellugi, and Edward S. Klima. The Signs of Language Revisited: An Anthology to Honor Ursula Bellugi and Edward Klima. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2000. ISBN 978-0585356419

- Groce, Nora Ellen. Everyone Here Spoke Sign Language: Hereditary Deafness on Martha’s Vineyard. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0674270404

- Kendon, Adam. Sign languages of Aboriginal Australia Cultural, Semiotic, and Communicative Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 0521360080

- Klima, Edward S., and Ursula Bellugi. The Signs of Language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0674807952

- Lane, Harlan L. The Deaf Experience Classics in Language and Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0674194601

- Lane, Harlan L. When the Mind Hears: A History of the Deaf. New York: Random House, 1984. ISBN 0394508785

- Lucas, Ceil. Multicultural Aspects of Sociolinguistics in Deaf Communities: Sociolinguistics in Deaf Communities, vol. 2. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-1563680465

- Padden, Carol, and Tom Humphries. Deaf in America: Voices from a Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0674194236

- Poizner, Howard. What the Hands Reveal about the Brain. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0262161053

- Sacks, Oliver W. Seeing Voices: A Journey into the Land of the Deaf. Vintage, 2000. ISBN 978-0375704079

- Stiles, Joan, Mark Kritchevsky, and Ursula Bellugi. Spatial Cognition: Brain Bases and Development. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates, 1988. ISBN 978-0805800463

- Stokoe, William C. Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles. Linstok Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0932130013

- Stokoe, William C. Sign Language Structure: An Outline of the Visual Communication Systems of the American Deaf. Linstok Press, 1978. ISBN 978-0932130037

- Tomkins, William. Indian Sign Language. Dover Publications, 1969. ISBN 978-0486220291

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ABC Slider Learn ASL fingerspelling

- ASL Browser Video dictionary of ASL signs

- 32 Uses and Benefits of American Sign Language (ASL) for Silent Communications

- Why Is It Important to Learn American Sign Language (ASL)?

- Top 26 Resources for Learning Sign Language

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Sign_language history

- History_of_the_deaf history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Sign language»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

All of us have a unique way to communicate in order to navigate the world around us and interpret life.

Even though speaking is considered the most common language mode among people, not everyone is able to exercise it. There are over 10 million individuals across Pakistan who live with some level of hearing loss. For someone who maintains the condition of deafness and can’t hear sound, the use of auditory language to exchange information is a no-way. A large number of the population is disconnected from the mainstream hearing-dominated society and lie at the risk of being marginalised, because people who are limited to using only speech can’t communicate with them. A lack of accessibility to support the conversation between both communities also adds to the problem.

Because of this, a huge challenge in the form of a communication gap between D/deaf, hard of hearing, and hearing people arises. To bridge this gap, a non-verbal language known as sign language exists.

So, you must now be wondering, what exactly is this sign language?

1. Sign language is a natural and visual form of language that uses movements and expression to convey meaning between people.

Sign language is a non-verbal language that Deaf persons exclusively count on to connect with their social environment. It is based on visual cues through the hands, eyes, face, mouth, and body. The gestures or symbols in sign language are organised in a linguistic way. It is a rich combination of finger-spelling, hand gestures, body language, facial expressions, timing, touch, and anything else that communicates thoughts or ideas without the use of speech.

Deaf people are the main users of sign language. Some hard of hearing people use it as a handy means of communication too. It is also used by those hearing individuals who can’t use speech, be it due to a disability or condition, or by those who have Deaf family members, and used even sometimes by monks who have taken a vow of silence.

2. No person or committee invented sign language.

No one knows for sure when the first Deaf person tried out visual gestures to express themselves. Many sources agree that using hand gestures and body language is one of the oldest and most basic forms of human communication, and it has been around just as long as spoken language.

The first written document of sign language is said to have come from Plato from Ancient Greece. In his Cratylus, he recorded Socrates saying:

If we had neither voice nor tongue, and yet wished to manifest things to one another, should we not, like those which are at present mute, endeavour to signify our meaning by our hands, head, and other parts of the body?

Native Americans also used sign language to communicate with other ethnic groups who spoke different languages. Even long after the European conquest, this system was in use. Another example is the case of a rare ethnic group that carried genes for deafness. Their island was isolated, so the trait spread among the locals at speed and a great population of Deaf people was formed. A local deaf culture developed and sign language arose so that the deaf could communicate with each other.

In South Asian literature history, there are hardly any mention of sign languages and Deaf people. If there are some, they all date back to ancient times. In religious subjects, symbolic hand gestures have been used for many centuries, but their customs often excluded Deaf participation. Classical Indian dance and theatre also sometimes uses hand and arm gestures that have specific meanings.

In the Hidayah, a 12th century Islamic legal commentary, there was a reference to visual signals used by Deaf people for communication. Deaf people were acknowledged to have legal standing in areas like bequests, marriage, divorce, and financial transactions if they could communicate with understandable signs.

Some say today that sign language came into form more than 200 years ago through the mixture of different cultures and local sign languages. As time went on, the mixed form changed into a vibrant, complex, and mature language in every region.

3. Different countries have different sign languages.

There are several thousand spoken languages across the world and all are different from each other in one sense or the other. In the same way, sign language has hand gestures and visual representations of many different types.

There is Pakistani Sign Language (PSL), American Sign Language (ASL), British Sign Language (BSL), French Sign Language (LSF), Indian Sign Language (ISL), and so on. American Sign Language (ASL) and British Sign Language (BSL) are both based on English language. Pakistani Sign Language (PSL) and Indian Sign Language (ISL) are also well-known sign languages in the South Asian region.

There are many varieties of sign language in the region, including several subsets of home and local sign languages. There is difference in the flow of signing, pronunciation, slang, and some gestures. These local signs also have distinct accents and dialects, similar to how certain English or Urdu words are spoken differently in separate parts of the country.

4. Sign language is different from spoken language.

Every language, whether verbal or non-verbal, has their own elements and functions and differ from each other in how they are used.

Even though sign language is another means of communication and also has every basic feature of language, it is still different from spoken language in many ways.

You can express your thoughts and ideas in sign language in different forms, just as you can with other languages like Urdu or English. Unlike in spoken languages where speakers may convey meaning by using their voice, sign language users may use hand gestures and facial expression to send a visual signal, use signs to wave hello or goodbye to someone, or point to something they want and use body language to emphasise any idea.

5. Sign languages have their own grammar.

It is said that sign languages are the manual representation of spoken languages, but that’s not true. In reality, both language modes have their own grammar structure, vocabulary, and syntax. The grammars of these visual and gesture-based sign languages are unlike the grammars of sound-based or written languages.

Unlike in spoken languages where grammar is expressed through sound-based signifiers for tense, aspect, mood and syntax (the way we organise individual words), sign languages use hand movements, sign order, as well as body and facial cues to create grammar. In ASL, certain mouth and eye movements act as adjectival or adverbial modifiers.

That is because gesture-based languages are concerned with appearance and concepts, whereas spoken and written languages are more about grammar rules.

6. Children learn sign languages the same way they learn spoken languages.

Parents are usually the power source of a child’s early language learning. Children learn how to do signs from a young age and as natural as they do with any spoken languages. There are also important sign language stages and baby babble. When babies are learning the visual language, they babble with their hands and over time, learn how to better express their signs.

If a hearing child is born to parents who are deaf and use sign language, the child will catch the mechanism the same way they would if the parents used a spoken language, and become fluent sign language users.

On the other hand, if a Deaf child has hearing parents, the learning of sign language may be different. In fact, studies suggest that 9 out of 10 children who are deaf are born to hearing parents. Some hearing parents are reluctant to introduce sign language to their Deaf child. Some of them who do choose to, they learn it along with their Deaf child so that they could communicate with them. Sometimes, the child may only learn sign language through their deaf peers, other Deaf family members, or community people.

7. Sign language is a visual language.

We all already know this fact, but it’s important to emphasise. Sign language may be like any other language in many ways and should be valued as such, but it’s also different.

Sign language is expressive and artistic in comparison to a spoken language’s auditory nature. The gestures of hands and body, facial expressions, and finger-spelling breathe life into its visual spirit. Sign language may be an animated way to convey meaning, but it can be quite easy and formal, as best shown in our video here:

Communication in sign language is like a dramatic arts performance − the rhythm of words, expressive facial cues, the little pauses in between, the breath intake, the emphasis and melody, body language, and head and hands gestures.

It is beautiful not only because it shows us what sign language has the power to do, but because it shows us what language does.

Want to learn sign language? You can easily learn the basics online from here.

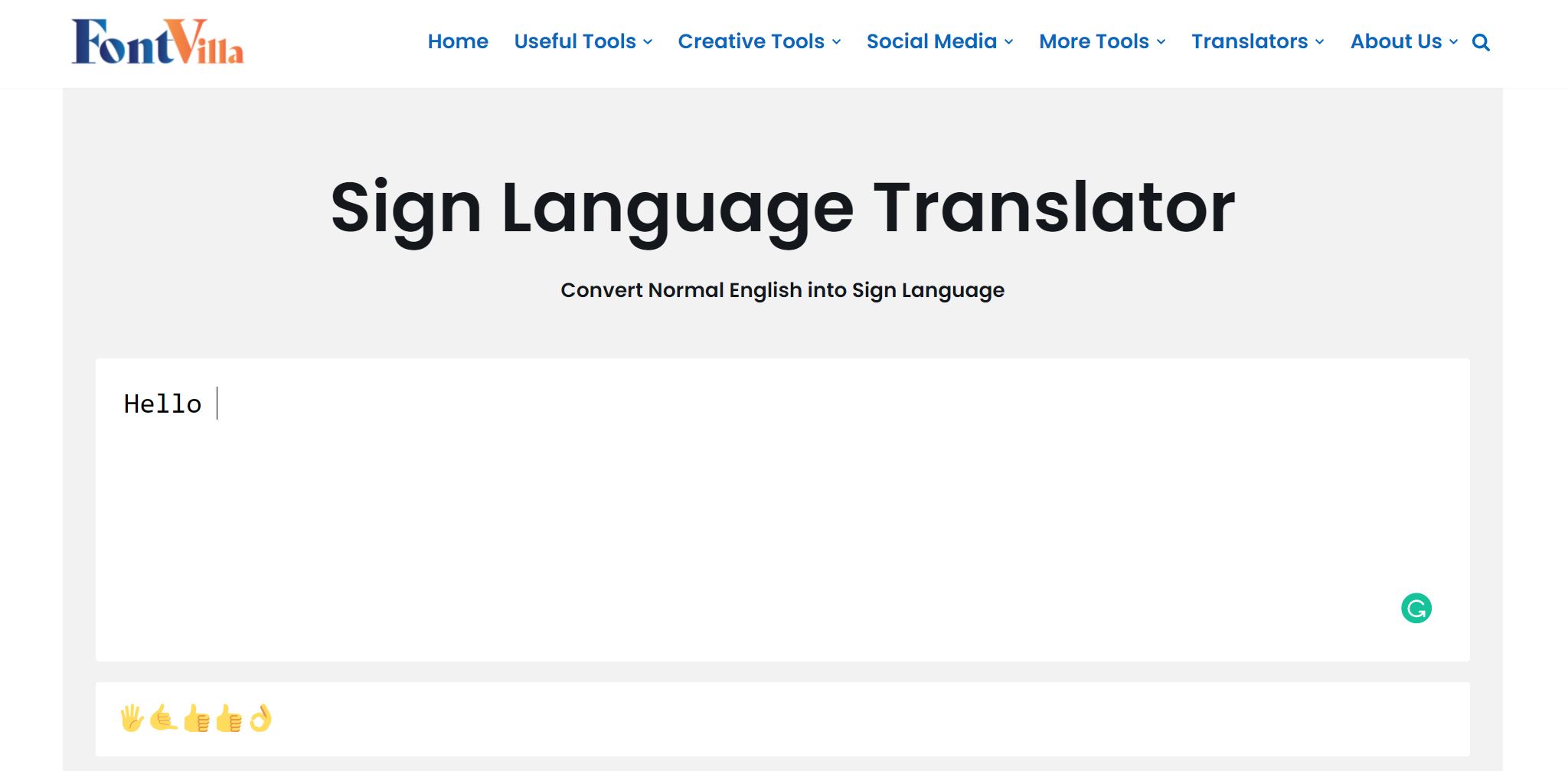

Convert Normal English into Sign Language

Your text will appear here..

What can Sign Language Translator do for you:

If you know someone that is deaf or can’t hear well, then the only way to effectively communicate with that person is by sign language. These days the American sign language is becoming more and more popular, people from around the world are starting to use this variation of sign language to effectively talk with the deaf.

It is perhaps the most effective way of communication for the deaf. Learning the American sign language translation however can be a difficult task, since it’s more of a motor skill than a cognitive one.

To learn and perfect your command over ASL to English translator you need to know when you’re wrong and when you’re right, so in other words, you require a teacher. Fontvilla, the text formatting website, realizes that not everyone can afford to take classes whether it’s a limitation of time or money.

So they have come up with an ingenious solution for anyone looking to improve or learn the American sign language. They have introduced the American sign language translators. A free online tool that anyone can use to convert normal sentences from English to sign language.

ASL translator and Fontvilla:

Fontvilla is a great website filled with hundreds of tools to modify, edit and transform your text. It works across all platforms and the converters and translators offered by Fontvilla are in a league of their own.

They’re super easy to use and are really fast. Fontvilla has tons and tons of converters ranging from converting text to bold or transforming the font of your text into anything you want. It’s the ultimate hub for customizing and personalizing your text. With Fontvilla, you can convert plain old boring text into something spectacular.

Wingdings Translator

Fontvilla has recently launched a brand new online translator known as the ASL translator, as the name suggests is an online tool that can be used to transform English sentences translation to sign language.

How it works:

Once you write the text in the dialog box and press enter all your words will be processed by Fontvilla’s translating algorithm, the results of which will be shown in the form of images of hands.

This will show you how to orient your hands and how to communicate the sentence in sign language. The images displayed are in such a format that you can easily copy them and paste them into any website, social media platform, or offline document that you wish.

To wrap it all up:

- Type the text you want in Sign Language Translator

- You will see fonts below

- Copy any font you want to use

- Paste it where you want and enjoy it

How to use it:

Using the online ASL translator is really easy. It’s just a simple copy and paste based tool. Once you open up the Fontvilla website you will have to type the text, that you want to convert, into a dialog box or you will have to copy the text and paste it into the box.

Braille Translator

Just press enter or the convert button and your text will be instantly converted into American sign language images. Now you can copy these images and paste them wherever you want or you can simply learn the hand gestures this way by mimicking the results.

Benefits:

As you can probably assume a tool like this can be used for a variety of purposes. It has far-reaching benefits. It is the ultimate tool to learn and improve your sign language skills. An essential language that everyone should know. The best part of this online ASL translator is that it can act as a teacher of sorts.

You can type the sentence you want to communicate and check to see if you’re right or wrong. Furthermore, there aren’t any time limitations associated with this online translator. Since it’s a web-based tool you can access it anywhere and at any time.

In this busy life, hardly anyone can take out the time from their day to attend extra classes and learn a new language therefore it is the best translator and teacher for learning ASL.

Another great feature of this ASL online translator is that it’s free. People don’t have to spend a dime to use this great English to an ASL translator. This means that you can learn ASL for free and at any time that you want.

Old English Translator

The online translator is really fast too, it can display your results in a matter of milliseconds. When you press the convert button the extremely efficient algorithm instantly converts the words into hand gestures that you can use to communicate with the deaf.

The ultimate tool for communication:

It’s the ultimate tool for communicating with the deaf, not only can it be used as a teacher to learn the American sign language. It can also be used in situations where you really need a translator. Say for example you need to talk to a deaf person or a person that is hard of hearing but you can’t since you don’t know how to translate English to sign language.

In situations like these, you can simply use this online translator and convert the sentence that you want to speak into ASL. it doesn’t matter if you have learned ASL or not since you can use this tool to talk to him effectively.

For this, all you need to have is an internet connection and you’re good to go. Connect to the Fontville website and choose the English translate to ASL translator from the hundreds of translating options that Fontvilla offers and you’re good to go.

Who should use the ASL translator:

Anybody and everybody who wishes to learn the language or wishes to effectively communicate with the deaf. It’s an essential tool that everybody should have in their arsenal.

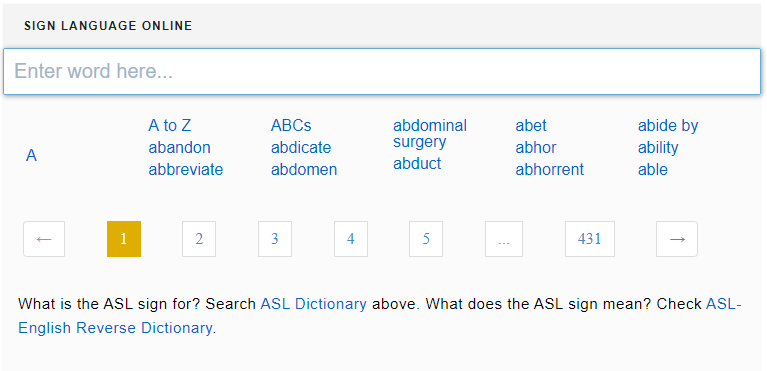

In this article, you will read about various online tools that can help you convert simple or complex texts or words into sign language.

Learning a different language is not easy at all, and to learn the sign language seems a different deal altogether. Although there are different types of online training courses available that can help you learn sign language for better understanding among people with hearing disability, sometimes we need a quick translation for the exact words if we are not so good at learning sign language.

To ease this situation, here we have some online web application for you that can help you search the signs to be conveyed at that exact moment without any hassle. You can pretty much translate most of then text online. So, let us see how these tools work during the time of establishing a communication with people having hearing disability.

Here we have listed five web application that can help you convert the simple or complex words and sentences into sign language instantly. Most of these websites use American Sign Language as Natural language for the people with hearing disability. It is primarily used to communicate with people having a hearing disability in USA and Canada. Hence, it is important to remember to use the application consciously.

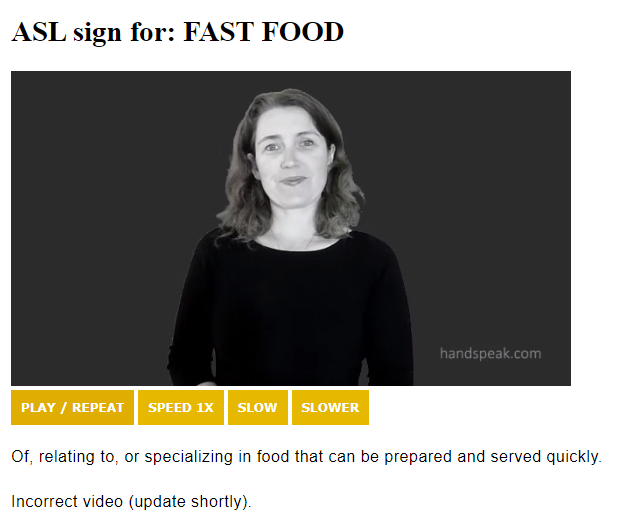

HandSpeak

Handspeak.com is a content web application that helps you communicate with culturally deaf people using sign language followed by the codes of American Sign Language or other sign languages. This website consists of the online grammar, dictionary, fingerspelling, literature, ASL writing, etc based on ASL codes that also helps the ASL community to further their knowledge and learn sign language easily.

This website provides result of the searched word in the form of a GIF or video that help you better understand and replicate the movements of hand for ease of communication.

Try this web application here.

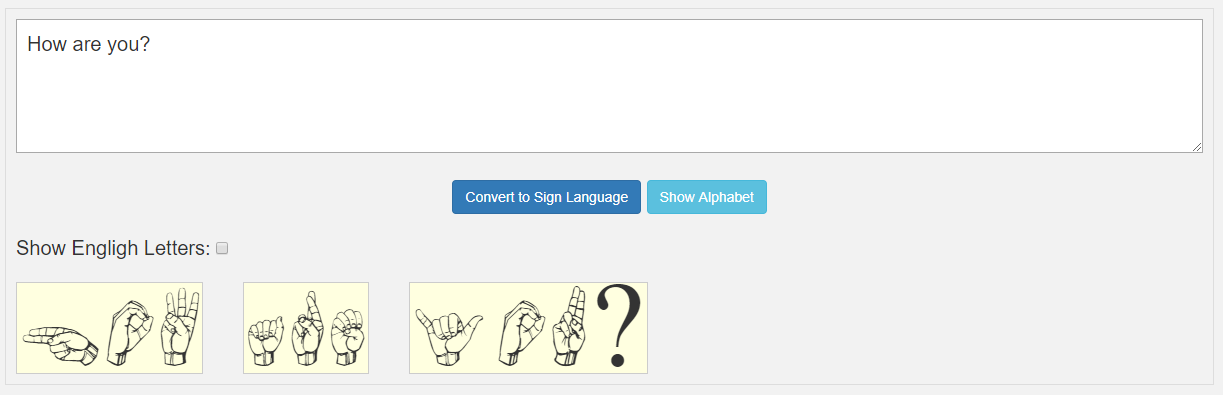

WeCapable

This is another easy web application that converts simple texts into the sign language in seconds. When you visit the website, you can easily see the translator on the homepage itself where you can type in your simple English text and the result will be shown in the sign language. Also, you can also see the full chart of the sign language w.r.t. English alphabets by clicking on “Show Alphabets”.

Try this web application here.

LingoJam

LingoJam is a simple to use web application where you can translate your English text into a sign language on the homepage itself. This website also uses American Sign Language as a base to convert your simple text into the sign language. Specifically, this website converts the English characters used in the sentences into a sign language for a simple understanding of words and sentences as a whole.

Try this web application here.

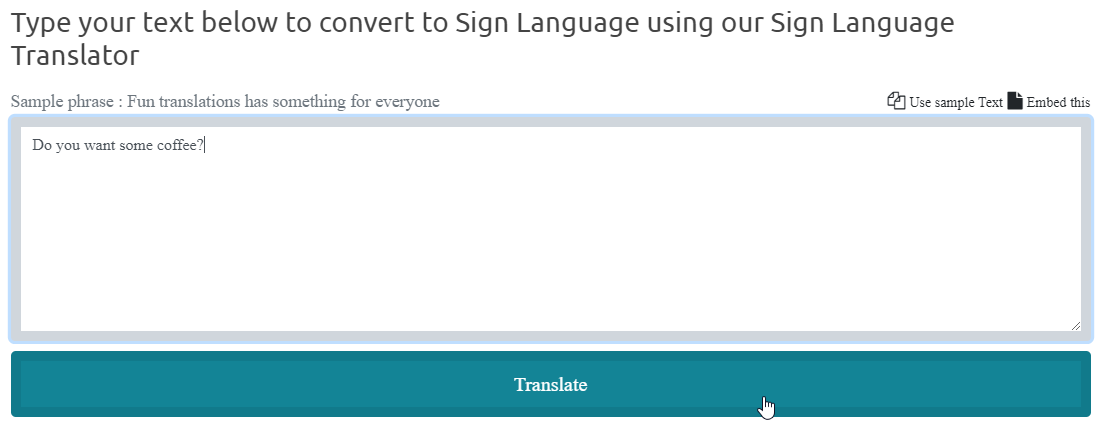

Fun Translations

As the name suggests, this website is more than just a sign language translator. Only one part of it consists of the sign language or finger-spelling (using fingers to explains the English letter). There are other types of translator available on the website, some can prove to be really good and some translations can be just for fun (for example the Dothraki Translator).

Even with so many options of translations, you can rely on the sign language translator on the website as this website uses a simple finger-spelling to convert your English sentence into the sign language sentence.

Try this web application for sign language here.

For other fun translations, click here.

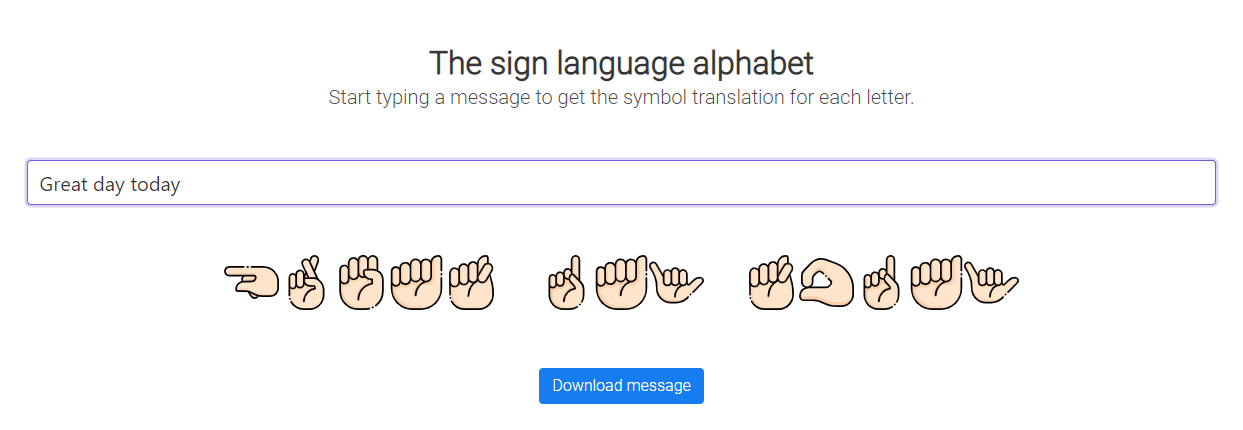

Deaf Alphabet

Deal Alphabet also used the same American Sign Language protocol to translate the written English text into a sign language. This web application can be accessed on the homepage itself. You can simple past your English sentence on the space given on the left side of the website, and within seconds the website will show you the results.

Try this web application here.

In brief

All these web applications work on the same feature of using the American Sign Language as their protocol to convert the English sentence into a sign language. It can be seen that this protocol used finger-spelling as its base to convert the complex English sentences into the sign language. This language evolved into a natural language in the Deaf community and hence used in the USA and Canada predominantly to communicate with people having hearing disabilities.

These tools can be used when you are in immediate need to communicate in the sign language. However, if you are looking for training in the sign language, we shall recommend you to take up a training course provided by various online training centers for better understanding and communication vocabulary.

by Joanne Cripps and Anita Small, M.Sc., Ed.D.

The Canadian Cultural Society of the Deaf (CCSD) has been asked this question often.Should we use the terminology signed language or should it be, sign language? What is our position on this?

Signed language is linguistically correct but it could be misinterpreted so that it does not support the values of the Deaf community. There are many perceptions when we see those two words: signed language. Some people would use this term to argue for their own benefit to negate the value of true languages in sign. They may use the term signed language to advocate for Signed English – Seeing Essential English (SEE1), Signing Exact English (SEE2), or other signed systems that try to represent English on the hands. These signed systems are often presented and labeled as signed languages because they are visually expressed but they are not languages.

The word signed (with “ed”) is an adjective describing the modality of language in signed language. The words sign and language are both nouns in sign language. The emphasis is on both and we are referring to the wholeness of a language. Sign language is an entity interconnected socially, culturally and educationally such as American Sign Language (ASL) and langue des signes québécoise (LSQ).

When signed is changed to sign, it becomes a noun and thus shifts the emphasis, linking it to Deaf identity with a complete visual language. Language and culture are inextricable tied. Deaf Culture needs to have a complete visual language that is highlighted and celebrated by the Deaf community.

The only context in which the term signed language would be used is if you were describing signed languages versus spoken languages in which case the explicit purpose of the discussion was to refer to the modality of languages rather than referring to the languages themselves.

So to answer this question, for the reasons outlined above, CCSD’s position is to use Sign Language to refer to our language ASL or LSQ in Canada.

CCSD

June 23, 2014

One of the most common misconceptions about sign language is that it’s the same wherever you go. That’s not the case. In fact, there are somewhere between 138 and 300 different types of sign language used throughout the world today. New sign languages frequently evolve amongst groups of deaf children and adults.

With that in mind, let’s take a look at 9 examples of sign languages from around the world:

British Sign Language (BSL), Auslan and New Zealand Sign Language

Around 150,000 people in the UK use British Sign Language. BSL evolved at Thomas Braidwood’s schools for the deaf in the late 1700s and early 1800s. From there, it spread to Australia and New Zealand. Auslan (Australian Sign Language) and New Zealand Sign Language are therefore quite similar. They use the same grammar, the same manual alphabet, and much of the same vocabulary.

In fact, some sign language experts consider BSL, Auslan, and New Zealand Sign Language to be dialects of the same sign language, called British, Australian and New Zealand Sign Language, or BANZSL for short. That said, despite the high degree of overlap, there are also differences between the different branches of the BANZSL family. For example, New Zealand Sign Language includes signs for Māori words. It also includes signs from Australasian Sign Language, a type of signed English used by New Zealand schools for the deaf in the 1980s.

Auslan includes some signs derived from Irish Sign Language, as well. Deaf Indigenous Australians may use Auslan or one of the native Australian sign languages that are unrelated to Auslan. The Far North Queensland dialect of Auslan incorporates features of these indigenous sign languages, too.

Want to learn more about BSL? See 10 Facts About British Sign Language and BSL Interpreters

French Sign Language

French Sign Language (LSF) is the native language of approximately 100,000 native signers in France. It’s also one of the earliest European sign languages to gain acceptance by educators, and it influenced other sign languages like ASL, ISL, Russian Sign Language (RSL) and more.

Charles Michel de l’Épée is sometimes credited with inventing LSF. In reality, all he did was take the rich sign language already used by the Parisian deaf community, add a bunch of rules to make it impossibly complicated, and then establish a free school for the deaf to teach his version of the language.

But even though he couldn’t resist tinkering, he was willing to accept sign language as a complete language on its own merits. And because he founded a school where deaf students could gather and were encouraged to use sign language to communicate, French Sign Language flourished until “oralism” became all the rage in the late 19th century.

Students were discouraged from signing in schools from the late 1800s until the late 1970s. However, the deaf community continued to use French Sign Language to communicate with each other, and in 1991 it was once again incorporated into education.

American Sign Language (ASL)

Americans and Brits are often said to be “divided by a common language.” But the deaf communities in the two countries don’t even have a common language. BSL and American Sign Language are not even in the same language family.

250,000-500,000 people in the United States claim ASL as their native language. It’s also used in Canada, West Africa and Southeast Asia. ASL is based on French Sign Language, but was also influenced by Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language and other local sign languages. Like French Sign Language, ASL uses a one-handed fingerspelling alphabet.

Sign Language Around the World: Irish Sign Language (ISL)

Today, most people in Ireland speak English. But deaf people in Ireland speak Irish Sign Language (ISL), which is derived from French Sign Language. Although ISL has been somewhat influenced by BSL, it remains quite distinct. As of 2014, around 5,000 deaf people, primarily in the Republic of Ireland but also in Northern Ireland, use Irish Sign Language to communicate.

One interesting footnote about ISL: Many Irish deaf students were educated in Catholic schools that separated students by gender. So, for a time, men and women each had their own dialects of ISL. However, these differences have diminished over time.

Chinese Sign Language (CSL or ZGS)

Anywhere from 1M to 20M deaf people in China use Chinese Sign Language to communicate. However, it’s difficult to determine how many people actually use it because the Chinese education system has discouraged and stigmatised its use for most of the past five decades. Most deaf Chinese children are treated at “hearing rehabilitation centres,” which favour a strict oralist approach. That said, more Chinese schools for the deaf have opened in recent years, and Chinese Sign Language is slowly gaining acceptance.

The first Chinese school for the deaf was founded by American missionaries. However, Chinese Sign Language is not related to ASL. Many signs incorporate aspects of Chinese language and culture. For example:

“There is no generic word for brother in CSL, only two distinct signs, one for “older brother” and one for “younger brother”. This parallels Chinese, which also specifies “older brother” or “younger brother” rather than simply “brother”. Similarly, the sign for “eat” incorporates a pictorial representation for chopsticks instead of using the hand as in ASL.”

Brazilian Sign Language (Libras)

Around 3 million signers in Brazil use Brazilian Sign Language, which was given official status by the Brazilian government in 2002. Brazilian Sign Language may be related to French Sign Language or Portuguese Sign Language. However, it is so distinct that linguists classify it as a language isolate.

Indo-Pakistani Sign Language

Indo-Pakistani Sign Language is the native sign language in South Asia. However, it lacks official recognition and support. While it’s not taught in public schools, some NGOs do use it to teach both academic and vocational courses. Unfortunately, the interpreter shortage for Indo-Pakistani Sign Language is dire. In India, there are only about 250 certified sign language interpreters, and between 1.8 million and seven people who are deaf or hard of hearing.

Need a sign language interpreter? We can help! We provide certified BSL interpreters for events and meetings, as well as recorded sign language videos to make your content available to a wider audience. And if you need an interpreter for a sign language other than BSL, just let us know.

Sign Language is Not Universal:

The Ethnologue Languages of the World, lists that there are 142 sign languages in use, however this number is hard to accurately pin down due to new sign languages frequently being created at schools in village communities with high levels of congenital deafness. Sign language is a complex form of communication comprised of hand gestures, body language and facial expressions and it’s used to allow deaf individuals the ability to effectively communicate their thoughts and feelings. Many people are under the misconception that sign language is universal, however the manual languages differ significantly from one geographic region to the next. Sign languages, like spoken languages, develop naturally out of groups of people interacting with one another; region and culture play a large role in the development as well. Most sign languages are not mutually intelligible, therefore people who do not sign the same language can not understand one another. In some countries like Sri Lanka for example, every school has their own sign language, only known by the students who attend that school. Other countries share sign languages although they are called different names, Croatian and Serbian sign languages are the same and Indian and Pakistani sign language are also the same.

Three Major Forms of Sign Language Used in the United States:

- American Sign Language (ASL)

Speech, reading or listening skills are not needed to learn ASL, it’s a manual language and ideas can be understood easily. The language is free-flowing and natural and can be translated into spoken languages. ASL has its own idioms, syntax and grammar. ASL is signed in countries around the world.

- Pidgin Signed English (PSE) or Signed English

PSE is the most commonly used sign language in the United States among deaf individuals. The vocabulary is drawn from ASL, however it follows English word order. Filler and connecting words (to, the) as well as word endings (ed,ing) are often times dropped. Many teachers use PSE and it’s considered simpler to learn than ASL or SEE.

- Signing Exact English (SEE)

SEE is basically signing the English language word for word, the signs are drawn from ASL, however they’re expanded with prefixes and tenses that allow more options for the signer to pull from. The use of SEE allows the signer the option to develop a broader vocabulary. English speaking parents with deaf children seem to do better with SEE because it’s truly a visual representation of the English language.

Popular Forms of Sign Language Used Around the World:

Auslan (Australian Sign Language):

Auslan has two main dialects, Northern and Southern, they have different signs for things like animals, colors and days of the week, however grammatical structure is the same across dialects. Auslan is closely related to British Sign Language (BSL) and New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL), all of which hail from the BANZSL language family. Despite the fact that America and Australia both speak English, ASL and Auslan are very different. Auslan uses a two handed alphabet while ASL uses a one-handed alphabet.

British Sign Language (BSL):

BSL has many different dialects that can vary from region to region and they use a two handed alphabet. In 2011, 15,000 people, living in England and Wales, reported themselves using BSL as their main form of communication.

Chinese Sign Language (CSL):

CSL’s signs are visual representations of written Chinese characters, they use a one handed alphabet. There are many CSL dialects but the Shanghai dialect is the most common. The language has been developing since the late 1950’s and The Chinese National Association of the Deaf, is working hard to raise awareness and promote use of the language throughout the country.

Irish Sign Language (ISL):

ISL is mainly used in Northern Ireland and the language is closely related to American Sign Language as well as French Sign Language, however it’s not related to spoken English or Irish languages. The alphabet is signed using one hand. ISL has existed for hundreds of years and was formulated in Deaf communities throughout regions in Ireland. ISL was brought to Australia, South Africa, Scotland, and England by Catholic missionaries. You can still see remnants of ISL in some variations of BSL and used by some elderly Auslan Catholics today.

Japanese Sign Language (JSL):

JSL is very different than other sign languages, it uses mouthing to distinguish between signs and letters within the alphabet. JSL also utilizes more fingerspelling as well as the actual drawing of Japanese characters in the air. JSL is it’s own language aside from the fact that it borrows heavily from spoken Japanese.

Spanish Sign Language (SSL):

SSL is mainly used in Spain and there is an estimated 100,000 signers of SSL. SSL is completely different from ASL, in the same way that English is different from Spanish. SSL is used across all of Spain, except in Catalonia which uses Catalan Sign Language and Valencia which uses Valencian Sign Language.

Niki’s Int’l Ltd. is a WBENC-Certified Women Business Enterprise with 21 years of language service experience. A global network of highly skilled interpreters and translators are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for on-site, telephonic and video remote interpretation services. Our linguists are available in over 350 languages and dialects, and our network includes certified interpreters and translators. Our work is guaranteed with a $1 Million Errors & Omissions policy, so that you can be confident that your project will be completed with the highest level of quality and professionalism within the field. For more information contact us at 1-877-567-8449 or visit our website at www.nilservices.com.