The Oxford Word of the Year is a word or expression shown through usage evidence to reflect the ethos, mood, or preoccupations of the passing year, and have lasting potential as a term of cultural significance.

The Oxford Word of the Year 2019 is climate emergency.

Climate emergency is defined as ‘a situation in which urgent action is required to reduce or halt climate change and avoid potentially irreversible environmental damage resulting from it.’

This year, heightened public awareness of climate science and the myriad implications for communities around the world has generated enormous discussion of what the UN Secretary-General has called ‘the defining issue of our time’.

But it is not just this upsurge in conversation that has caught our attention. Our research reveals a demonstrable escalation in the language people are using to articulate information and ideas concerning the climate. This is most clearly encapsulated by the rise of climate emergency in 2019.

The data

Analysis of language data collected in the Oxford Corpus shows the rapid rise of climate emergency from relative obscurity to becoming one of the most prominent – and prominently debated – terms of 2019.

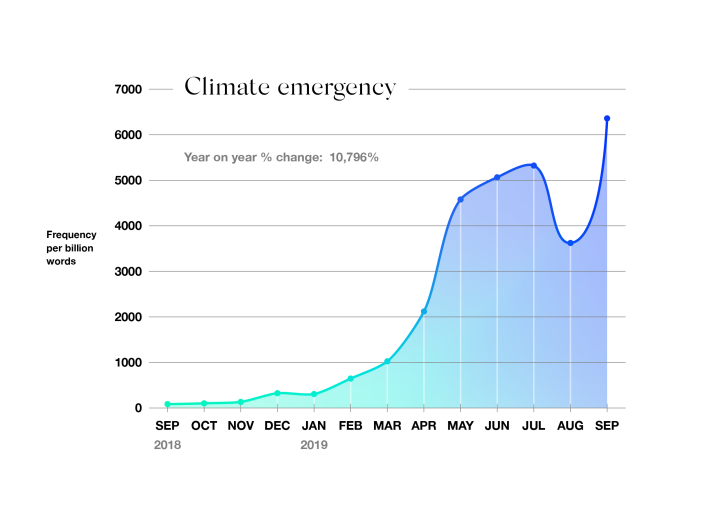

Usage of the phrase climate emergency increased steeply over the course of 2019, and by September it was more than 100 times as common as it had been the previous year.

The word climate has been central to 2019 overall, and features in a number of prominent phrases, but climate emergency stands out for a number of reasons. Statistically speaking, this represents a new trend in the use of the word emergency.

In 2018, climate did not feature in the top words typically used to modify emergency, instead the top types of emergencies people wrote about were health, hospital, and family emergencies. These suggest acute situations of danger at a very personal level, often relating to the health of an individual. Emergency also frequently occurs, as in the phrase state of emergency to indicate a legal declaration of an acute situation at a jurisdictional level. But with climate emergency, we see something new, an extension of emergency to the global level, transcending these more typical uses.

In 2019, climate emergency surpassed all of those other types of emergency to become the most written about emergency by a huge margin, with over three times the usage frequency of health, the second-ranking word.

Looking at the equivalent data for climate collocations, climate crisis and climate action – both of which are included in our Word of the Year 2019 shortlist – feature alongside climate emergency as the words most typically used to modify climate in 2019, as recorded in our corpus. All of these words have exceeded more moderate or speculative pairings like climate variability and climate prediction, and expected connections like climate scientist, which have dominated the usage data for more than 10 years.

This data is significant because it indicates a growing shift in people’s language choice in 2019, a conscious intensification that challenges accepted language use to reframe discussion of ‘the defining issue of our time’ with a new gravity and greater immediacy.

Use in context

One high profile example of this language development is the changes made by The Guardian in its reporting of environmental news in May. The newspaper stated that instead of climate change, its preferred terms are ‘climate emergency, crisis, or breakdown’ to describe the broader impact of climate change. The move prompted other media outlets to review and update their own policies and approaches to reporting on the climate.

The Guardian’s editor-in-chief Katharine Viner, who outlined the terminology changes, said: ‘We want to ensure that we are being scientifically precise, while also communicating clearly with readers on this very important issue. The phrase “climate change”, for example, sounds rather passive and gentle when what scientists are talking about is a catastrophe for humanity.’

Language choice in scientific reporting on climate science has been influential in this shift during 2019. With the publication of careful scientific analyses presenting the various consequences for the world’s communities should people fail to take action – see the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s special report Global Warming of 1.5 ºC, for example – an increasing number of climate scientists have urged their peers to ‘tell it like it is’ when communicating their research.

A recent article published in the journal BioScience and signed by 11,258 scientists from 153 countries argued that ‘scientists have a moral obligation to clearly warn humanity of any catastrophic threat’, and presented their research to declare ‘clearly and unequivocally that planet Earth is facing a climate emergency.’

Similar action has been taken in political circles this year, with a growing number of local and national jurisdictions officially declaring a state of climate emergency. On 28 April 2019, Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon became the first to declare a national climate emergency on behalf of the Scottish government in a party conference address. This was swiftly followed by official declarations from the UK, Portugal, Canada, France, and Argentina among others. Such a move has been likened to putting a country on ‘war footing’, a demonstration of commitment to combat the emergency by putting climate action at the centre of governmental policy.

Counter — climate emergency

The conspicuous rise of climate emergency in 2019 has also incurred debate over its merit and validity as a descriptor of the current environmental state.

Where many jurisdictions have declared climate emergencies, some have argued against formal declaration due to concerns that this hardening of language would alienate, rather than activate, a general public whose buy-in is needed to prevent disaster. In Canada, for example, Guelph city councillors narrowly voted to ‘acknowledge a climate crisis’, having changed the wording of the motion from ‘declare’ to ‘acknowledge’ and ‘emergency’ to ‘crisis’ in a bid to find common ground.

There has also been alarm over the implications of the growing number of ‘well-meaning’ declarations of a climate emergency. The writer Arundhati Roy, for example, observed an increasingly ‘militarized’ vocabulary around climate change in her Arthur Miller Freedom to Write lecture, delivered in May 2019. She raised concerns over the formalization of the climate emergency, which she suggested would ‘exclude most of the world to place the decision making straight back into the den of the same old suspects’ – the centres of power which had neglected or profited from climate change for decades.

While some acknowledge climate emergency but harbour concerns over the language choice, some in the scientific community question the validity of climate emergency as an appropriate term at all. A group called the Climate Intelligence Foundation, for example, addressed a letter to the UN Secretary-General during the Climate Action Summit in September 2019, arguing that ‘there is no climate emergency’. The letter has been criticised for utilising arguments long-since debunked by climate science authorities around the world; such debate still, however, contributed to the rise and dissemination of climate emergency as one of the most talked about terms of 2019.

Shortlist

All around the world in 2019, people have been talking and writing about the state of our climate, the implications of current climate science, and proposed solutions for averting ecological disaster.

Analysis of language data recorded in the Oxford Corpus shows how this global preoccupation has permeated different domains, uniting key issues from farming to mental health, air travel to legal campaigns, under the umbrella of the great climate debate.

Climate emergency may lead the pack, but this year our Word of the Year shortlist reflects the prominence of climate-related language documented in our corpus.

Climate action

Actions taken by an individual, organization, or government to reduce or counteract the emission of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, in order to limit the effect of global warming on the earth’s climate

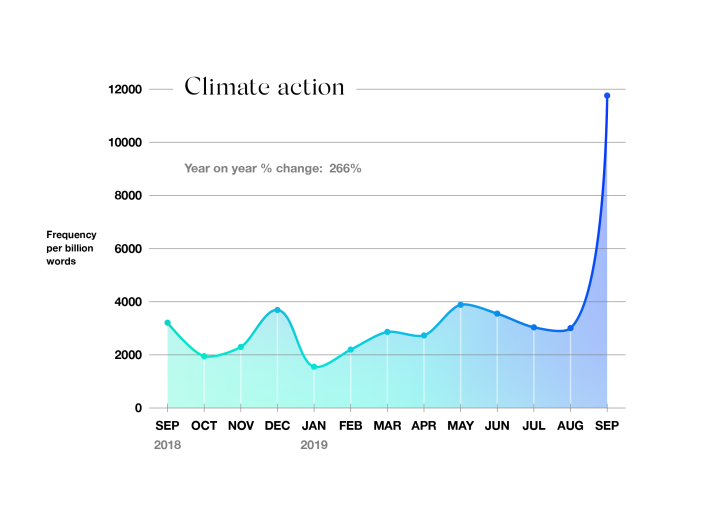

Our corpora record a 266% rise in usage over last year, with a dramatic spike in September documenting demands for climate action by protestors at climate rallies around the globe and media coverage of the gathering of world leaders for the UN’s Climate Action Summit in New York.

Climate crisis

A situation characterized by the threat of highly dangerous, irreversible changes to the global climate

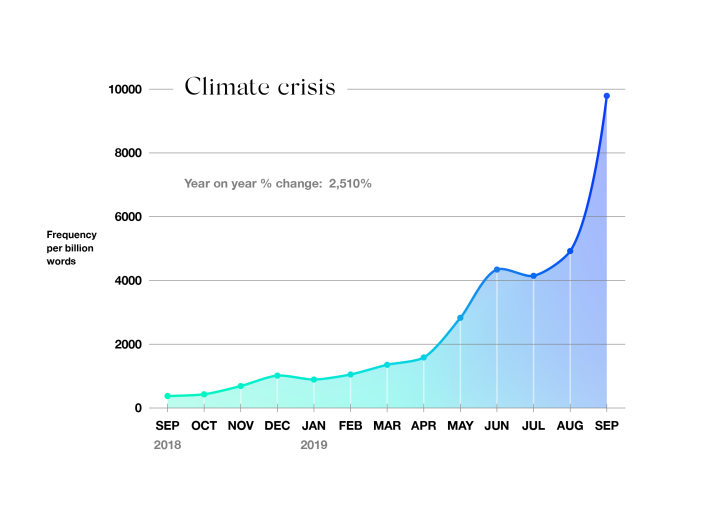

Like climate emergency, climate crisis is increasingly favoured as a more scientifically robust term for climate change across climate science and media reporting, resulting in a 26-fold increase in usage in 2019.

Climate denial

The rejection of the proposition that climate change caused by human activity is occurring or that it constitutes a significant threat to human welfare and civilisation

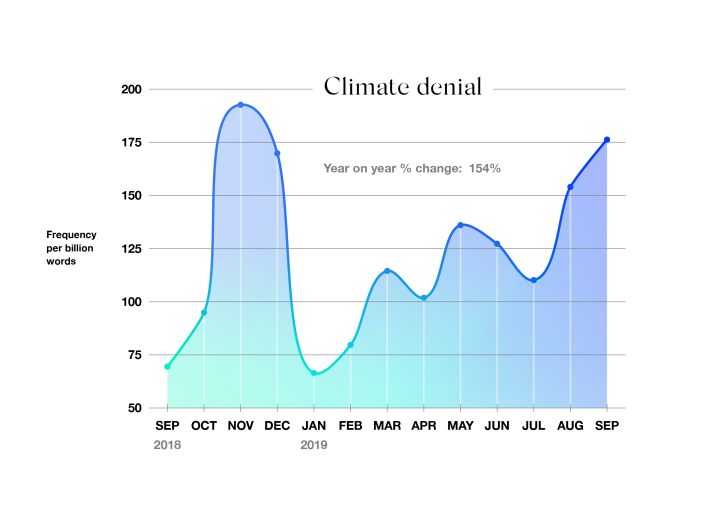

Our data reveals a 153% usage increase for climate denial in 2019, reflecting debate over climate science reporting and leading political figures’ reactions to it, and the hardening of language from scepticism to denial, with people typically described as climate science deniers or climate deniers instead of climate sceptics.

Though yet to reach the heights of November 2018 – likely coinciding with media coverage of President Trump’s denial of his own government’s climate report, among others – climate denial, and associated terms, has been ever-present this year.

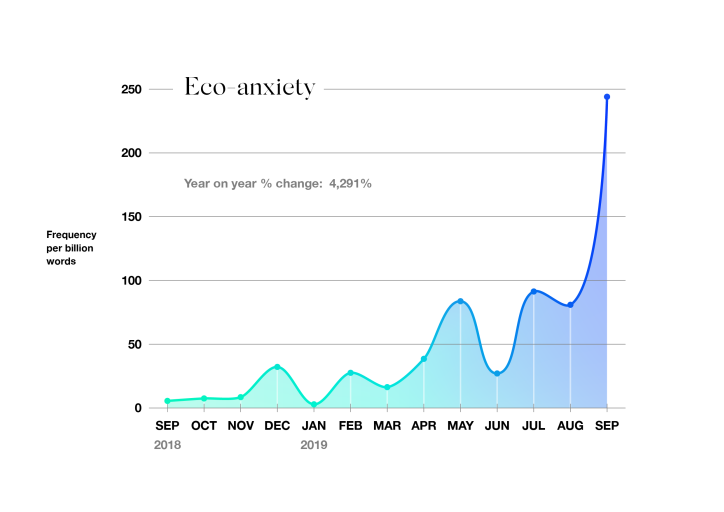

Eco-anxiety

Extreme worry about current and future harm to the environment caused by human activity and climate change

Our corpus records a 4,290% increase in use eco-anxiety in 2019, showing a growing discourse, particularly among young people, around the mental health impact of the climate emergency that has dominated headlines this year. While the symptoms are the same as clinical anxiety, eco-anxiety is not considered by mental health professionals to be a mental disorder as the cause of the worry is a rational response to current climate science reporting.

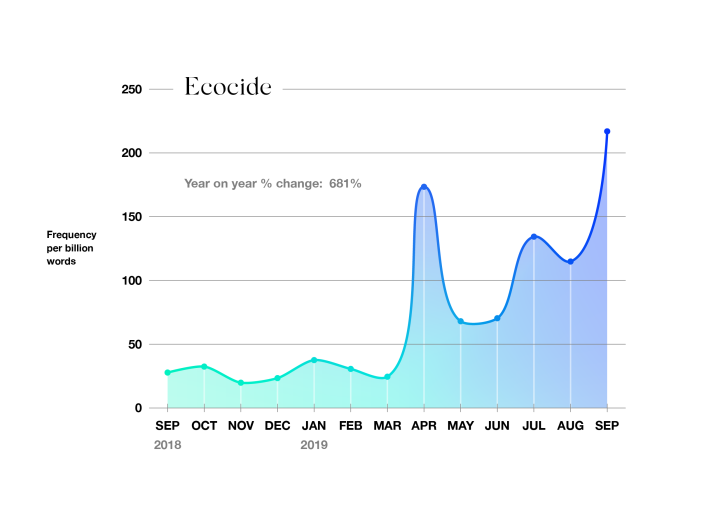

Ecocide

Destruction of the natural environment by deliberate or negligent human action

Amidst heightened public attention to the climate emergency and calls for action, the word ecocide has had a 680% increase in frequency of use over 2019. The term is at the heart of a legal campaign to make serious damage to the environment an atrocity crime at the International Criminal Court, putting it on an equal footing with genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Such a move would make government officials and business leaders individually criminally responsible for actions that knowingly or negligibly harm the planet.

The spike in April perhaps reflects increased coverage after the death of Polly Higgins, a British barrister and leading figure of the decade-long campaign for ecocide to be recognised as a criminal, rather than civil, offense.

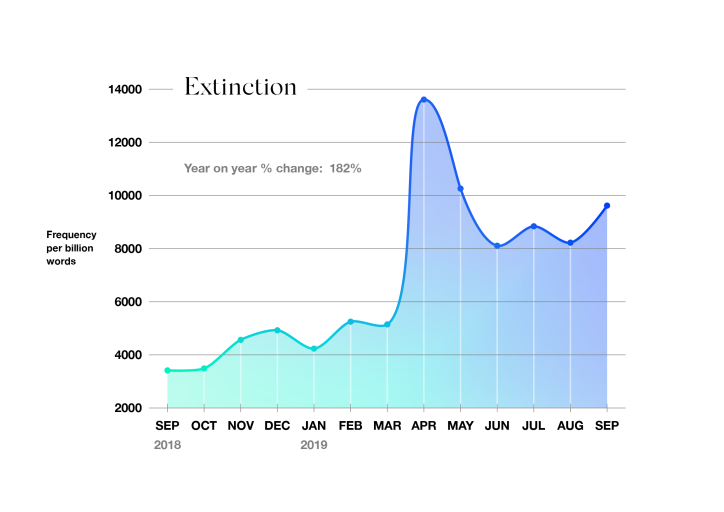

Extinction

The fact or process of a species, family, or other group of animals or plants becoming extinct

Extinction has seen a 681% increase in usage in 2019 as scientific analyses report on the breakdown of our planet’s biodiversity attributed to human activity. The UN’s Global Assessment Report, for example, stated that ‘human actions threaten more species with global extinction now than ever before’.Our language data records a huge spike in usage in April that corresponds with launch of Extinction Rebellion, the international movement using civil disobedience tactics to generate public awareness and secure political change to combat environmental breakdown.

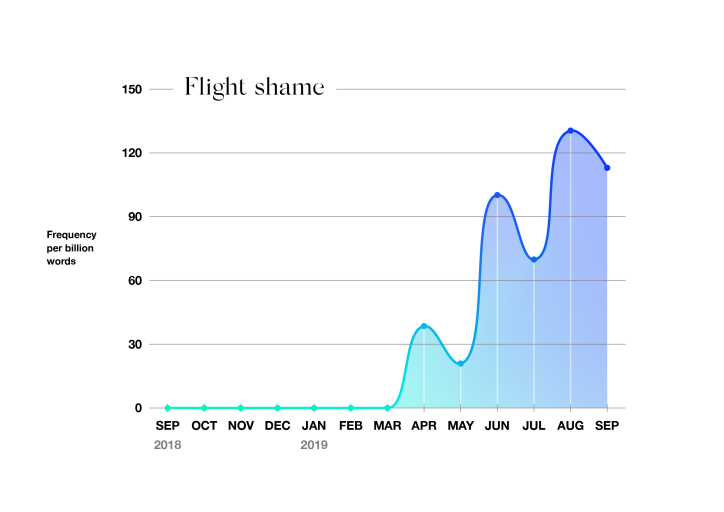

Flight shame

A reluctance to travel by air, or discomfort at doing so, because of the damaging emission of greenhouse gases and other pollutants by aircraft

Flight shame is a translation of the Swedish flygskam, a phenomenon that took off across Europe early this year before going global, resulting in a 182% rise in usage. Growing attention to individuals’ carbon footprints has seen people ditching carbon-intensive air travel for other, greener forms of transport, and the introduction of recommendations for a ‘frequent flyer levy’ to curb the ever-growing demand for air travel.

Climate activist Greta Thunberg, another Swedish export alongside flygskam, led by example in September when she made the two-week transatlantic journey from Plymouth in the UK to reach New York in the US for the UN’s Climate Action Summit.

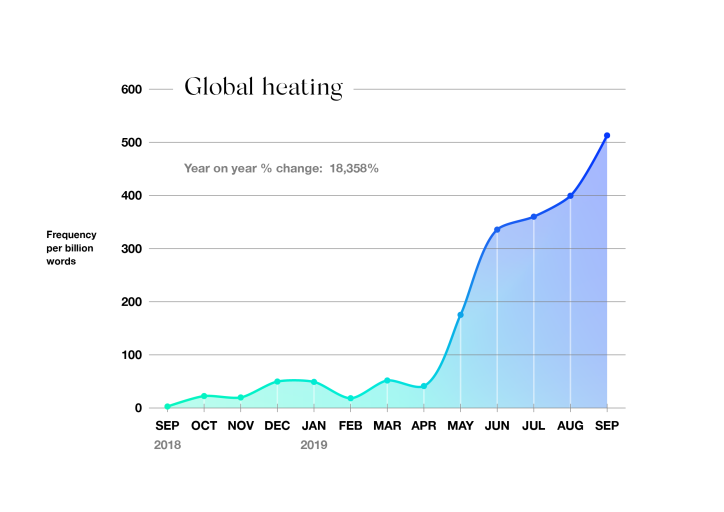

Global heating

A term adopted in place of ‘global warming’ to convey the seriousness of changes in the climate caused by human activity and the urgent need to address it

In December 2018, Prof Richard Betts, the UK Met Office’s climate research lead, advised: ‘global heating is technically more correct because we are talking about changes in the energy balance of the planet’. This year, our data shows the uptake of this revised terminology, presenting an 18,358% usage rise in 2019 over the same period last year as record-breaking temperatures and concern over the future of the Paris Agreement hit headlines around the world.

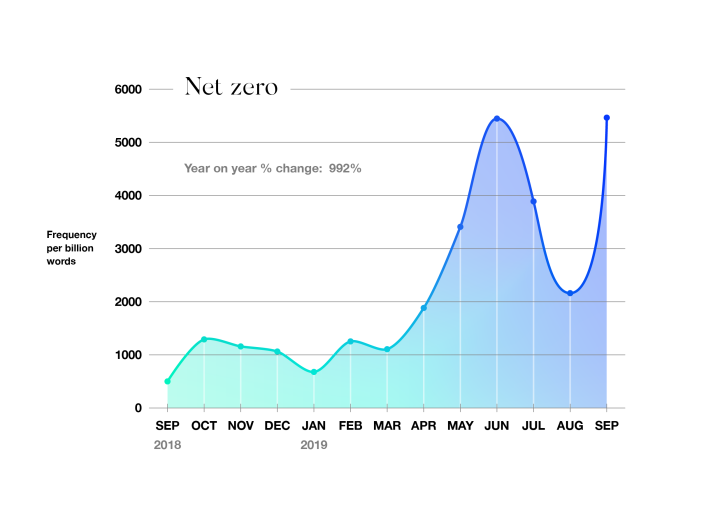

Net-zero

A target of completely negating the amount of greenhouse gases produced by human activity, to be achieved by reducing emissions and implementing methods of absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere

In June 2019, the UK became the first major economy to pass a net-zero law, and more than 60 countries have since pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. However, as initial analysis indicates urgent action is required to meet this target, debate as what action should be taken has contributed to a 992% usage rise for the term in 2019.

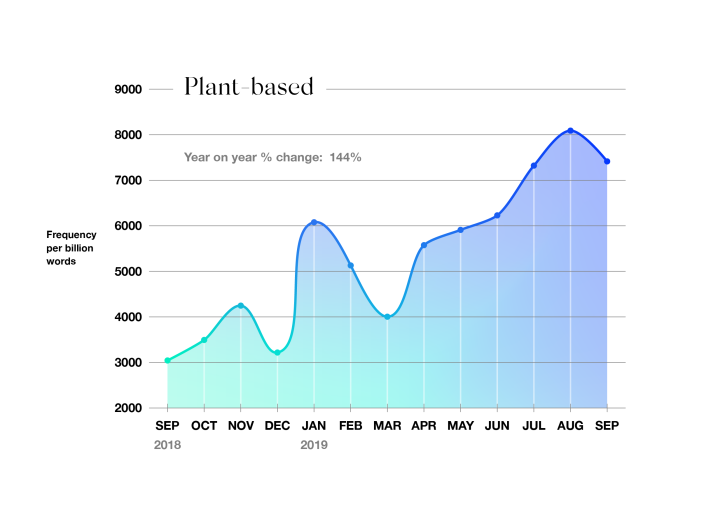

Plant-based

(Of food or a diet) consisting largely of vegetables, grains, pulses, or other foods derived from plants, rather than animal products

From lab-grown chicken to meatless burgers, 2019 has seen increased frequency of discussion of all things plant-based with the trend for clean meat, meat alternatives, vegetarianism, and veganism contributing to the 144% usage increase. Coverage of the Amazon rainforest wildfires in August, for example, brought renewed attention to damaging farming practices driven by high global demand for beef and a surge of people talking about sustainable alternatives.

This word was chosen based on the Word of the Day that resonated most strongly with fans on the Cambridge Dictionary Instagram account, @CambridgeWords. The word upcycling – defined as the activity of making new furniture, objects, etc. out of old or used things or waste material – received more likes than any other Word of the Day (it was shared on 4 July 2019).

We think that our fans resonated with upcycling not as a word in itself but with the positive idea behind it. Stopping the progression of climate change, let alone reversing it, can seem impossible at times. Upcycling is a concrete action a single human being can take to make a difference.

The number of times upcycling has been looked up on the Cambridge Dictionary website has risen by 181 per cent since December of 2011, when it was first added to the online dictionary, and searches have doubled in the last year alone. So it seems evident that lookups of upcycling reflect the momentum around individual actions to combat climate change – the youth activism sparked by Greta Thunberg, the growing trends of vegan, flexitarian and plant-based diets, reading and following the handbook There is No Planet B, or fashion designers upcycling clothes to create their latest collections.

Other words on the shortlist for Word of the Year 2019 all reflect the same concern with the effects of climate change:

carbon sink noun

an area of forest that is large enough to absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide from the earth’s atmosphere and therefore to reduce the effect of global warming

compostable adjective

something that is compostable can be used as compost when it decays

preservation noun

the act of keeping something the same or of preventing it from being damaged

The Cambridge Dictionary editors use data from the website, blogs, and social media to identify and prioritise new additions to the Dictionary. We identified upcycling as a word to include back in 2011 after noticing a spike in searches for the word.

A recent addition is the noun plastic footprint, defined as a measurement of the amount of plastic that someone uses and then discards, considered in terms of the resulting damage caused to the environment. This term, first identified by traditional citation gathering, received 1,048 votes in the New Words blog poll, with 61 per cent of readers saying it should be added to the Cambridge Dictionary.

-

Photo: miflippo | iStock / Getty Images Plus

Our Word of the Year for 2019 is they. It reflects a surprising fact: even a basic term—a personal pronoun—can rise to the top of our data. Although our lookups are often driven by events in the news, the dictionary is also a primary resource for information about language itself, and the shifting use of they has been the subject of increasing study and commentary in recent years. Lookups for they increased by 313% in 2019 over the previous year.

English famously lacks a gender-neutral singular pronoun to correspond neatly with singular pronouns like everyone or someone, and as a consequence they has been used for this purpose for over 600 years.

More recently, though, they has also been used to refer to one person whose gender identity is nonbinary, a sense that is increasingly common in published, edited text, as well as social media and in daily personal interactions between English speakers. There’s no doubt that its use is established in the English language, which is why it was added to the Merriam-Webster.com dictionary this past September.

Nonbinary they was also prominent in the news in 2019. Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal (WA) revealed in April during a House Judiciary Committee hearing on the Equality Act that her child is gender-nonconforming and uses they. Singer Sam Smith announced in September that they now prefer they and them as their third person personal pronouns. And the American Psychological Association’s blog officially recommended that singular they be preferred in professional writing over “he or she” when the reference is to a person whose gender is unknown or to a person who prefers they. It is increasingly common to see they and them as a person’s pronouns in Twitter bios, email signatures, and conference nametags.

-

The investigation into President Trump’s phone conversation with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky became something of a vocabulary lesson for many Americans, and the term quid pro quo was heard countless times from newscasters, pundits, politicians, and the president himself. Major spikes of lookups occurred on September 25th, October 17th and 18th, and November 20th, for a year-over-year increase of 644%.

We define quid pro quo as “something given or received for something else,” and «a deal arranging a quid pro quo.” The literal translation from New Latin is “something for something.”

The current use dates to the late 16th century. In its initial use, a now-obsolete sense from the beginning of that century, quid pro quo referred to something obtained from an apothecary when one medicine was substituted for another. Such substitutions could be either accidental or fraudulent. Soon after its apothecary sense the word took on a more general meaning of substitution. Today, the term is most often encountered in legal contexts.

-

It’s no surprise that impeach is among the top words of 2019, with the largest single spike following House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s announcement of an impeachment inquiry on September 24th. Overall, the word had a 129% increase in lookups over last year.

Impeach is defined in several ways, including “to charge with a crime or misdemeanor” and “to cast doubt on.” The former of these carries the additional specific meaning of “to charge (a public official) before a competent tribunal with misconduct in office”; the latter is often narrowed as well, with the meaning “to challenge the credibility or validity of.”

Although frequently thought of as meaning «to remove from office,» impeach has a precise legal use in cases such as this, in which the action describes a step in removing an official from office, but does not refer to the removal itself.

Impeach came to English from the French word empecher («to impede»), itself from the Latin word impedicare («to fetter»)—which is also the root of the English word impede.

-

In March it was news from the literary world that moved the humble crawdad from relative lookup obscurity to lexicographical prominence. Delia Owens, the first-time novelist whose Where the Crawdads Sing made it to the top of the New York Times bestseller list, was interviewed on CBS Sunday Morning, sending crawdad to the top of our searches with a spike of 1,200%.

Crawdad is used mostly west of the Appalachians to refer to the aquatic animal that looks like a small lobster and lives in rivers and streams—that is, to what’s also known as a crawfish or crayfish. Crawdad is an alteration of crawfish that dates to the early 20th century.

Incidentally, the fish of crawfish and crayfish was imposed late in the words’ development: both come from the medieval French word creveis, the second syllable of which sounded enough like fish that the name evolved to have the English word replace its original ending.

-

In October, egregious became a top lookup, increasing 450%, when reports surfaced that a Boeing pilot had used the word in describing an issue with 737 MAX planes. Fatal crashes that killed 346 people in October 2018 and March 2019 were blamed on the plane’s automated handling control system.

Egregious means «conspicuously bad» in modern English, but that meaning strays a bit from its original one. Like its Latin forebear egregius, egregious originally meant «distinguished» or «eminent.» Latin egregius comes from roots that can translate literally as «apart from the herd.»

-

Photo: DNY59 | iStock / Getty Images Plus

Lookups for clemency spiked 9,900% in January, after the governor of Tennessee granted clemency to Cyntoia Brown, a woman serving a life sentence, having been convicted of murdering a man when she was a 16-year-old victim of sex trafficking.

In legal use, clemency means both «willingness or ability to moderate the severity of a punishment (such as a sentence)» and «an act or instance of mercy, compassion, or forgiveness.» In this case, the governor’s clemency came in the form of commutation, with Brown’s life sentence reduced to 15 years. The word clemency comes from Latin clemens, meaning «mild» or «calm.»

-

Very common words are looked up frequently in the dictionary (love is among the top five lookups in the history of our site), which is sometimes surprising to people, but it’s truly rare to see one of the most basic function words in the English language spike in our data: the.

The Ohio State University filed a trademark application in August for the word the with the U.S. Patent Office, in order to protect new branding logos that emphasize the «The» that is part of the official (some say pretentious) name of the institution—and the spiked 500%.

The is one of the oldest words in English, and is pronounced thuh before words that begin with consonants («the governor») and thee before words that begin with a vowel («the only one»). But the pronunciation of the can also indicate emphasis or suggest uniqueness (a also works this way), with a stressed version of thee, the difference between «The Ohio State University» and «THE Ohio State University» (notice how you would read the name in two different ways).

Only a few institutions of higher learning include an official The in their names, including The Catholic University of America, The College of William and Mary, and The George Washington University.

-

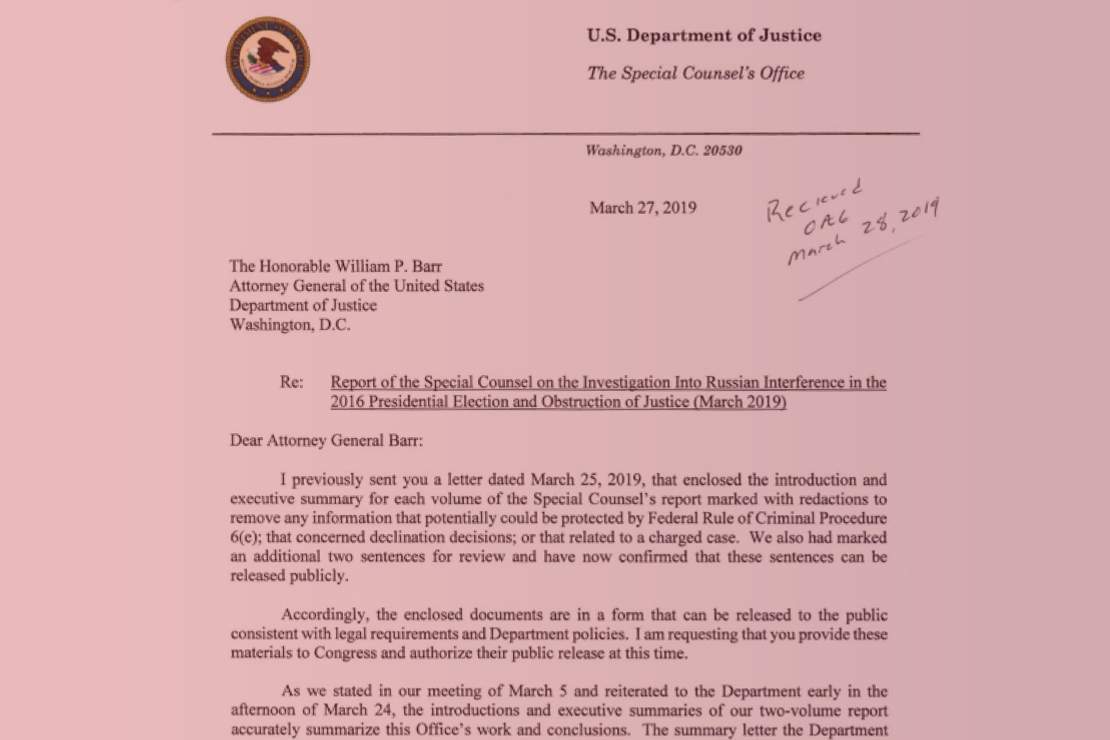

Snitty flew to the top of the dictionary lookups in May, increasing by 150,000%, when Attorney General William Barr used the word to describe a letter sent to him by Special Counsel Robert Mueller. The so-described letter was critical of something Barr had written: a summary of the Special Counsel’s report commonly known as The Mueller Report and formally known as the Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election.

Snitty is defined by Merriam-Webster as «disagreeably ill-tempered.» The word’s origin is unclear, though there may be a connection to snit, meaning «a state of agitation.» While snit (also of unknown origin) has been in use since the 1930s, snitty is a child of the 1970s.

-

Photo: Rawf8 | iStock / Getty Images Plus | The Washington Post

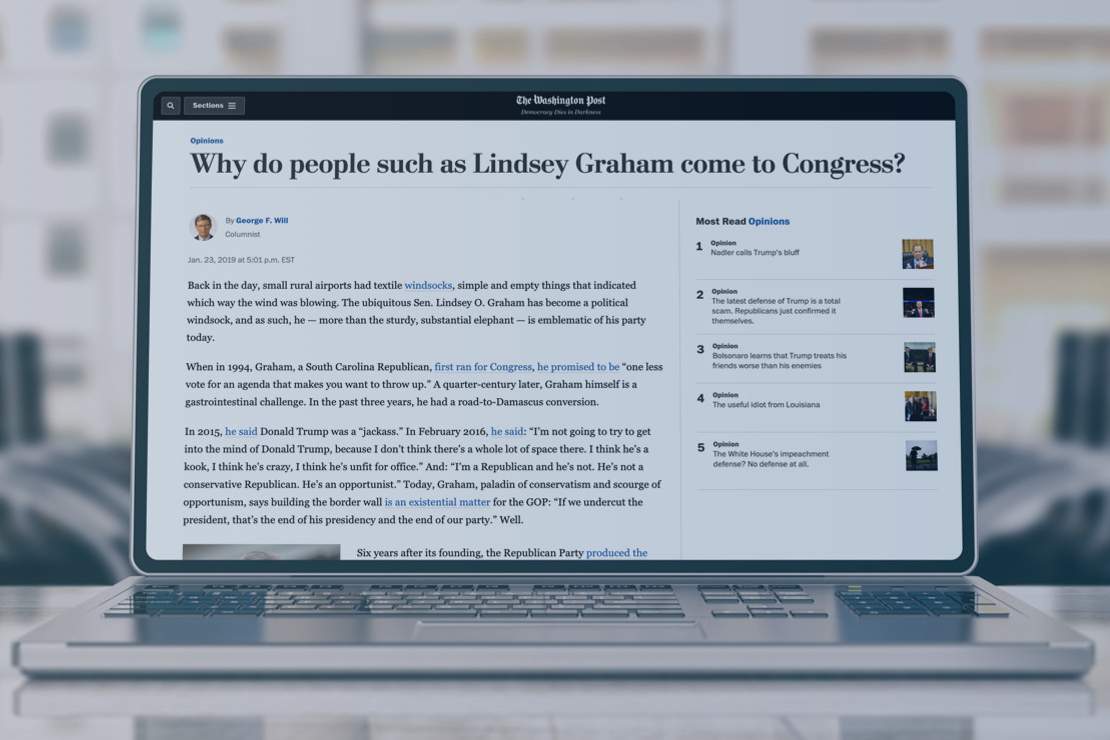

Tergiversation was our top lookup on January 24th—up 39,000%—after the word’s use in an article by Washington Post columnist George Will the previous day. Here’s how he used it:

During the government shutdown, Graham’s tergiversations—sorry, this is the precise word—have amazed.

Tergiversation can mean “evasion of straightforward action or clear-cut statement,” or “desertion of a cause, position, party, or faith,” and though it’s not perfectly clear which meaning was intended by Will, people certainly took notice of the word.

Tergiversation can be traced to the Latin words tergum (meaning “back”) and versare (meaning “to turn”). The word has been in use since the first half of the 16th century. The «g» in tergiversation is pronounced as /j/.

This isn’t the first time George Will has sent readers to the dictionary after using a bookish word in one of his columns: we saw spikes for bloviate in 2012 and Gadarene in 2010 after he used them.

-

In May, camp was the belle of the dictionary ball for a time, with lookups shooting up 5,800%. Access to the dictionary entry for the term was easier to come by than access to what inspired the lookups: a gala event celebrating «Camp: Notes on Fashion,» the newly-opened fashion exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The exhibit takes its name from Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay «Notes on Camp,» which unfolds in list form because «jottings … seemed more appropriate for getting down something of this particular fugitive sensibility.» Merriam-Webster defines the Sontagian sense of camp referenced by the Met as either «a style or mode of personal or creative expression that is absurdly exaggerated and often fuses elements of high and popular culture» or «something so outrageously artificial, affected, inappropriate, or out-of-date as to be considered amusing.» In earlier uses, the term (which is unrelated to the camp of tents and sleeping bags) has more sexualized overtones, being used to mean «exaggerated effeminate mannerisms (as of speech or gesture).»

-

When Robert Mueller used the word exculpate in his July testimony before members of the House of Representatives—»The president was not exculpated for the acts that he allegedly committed»—the word saw a dramatic increase in lookups, spiking 23,000%.

The word exculpate is defined as «to clear from alleged fault or guilt.» It traces back to Latin culpa, meaning «blame,» also the source of culpable, which means «meriting condemnation or blame especially as wrong or harmful.»

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

Составители Оксфордского словаря выбрали слово 2019 года — это climate emergency («чрезвычайная климатическая ситуация»), сообщается на сайте издания.

Словарь описывает climate emergency как «ситуацию, в которой требуются неотложные действия для сдерживания изменений климата и предотвращения необратимого ущерба окружающей среде».

Аналитики отмечают, что в этом году выражение, которое раньше практически никто не использовал, стало одним из самых заметных и широко обсуждаемых. К примеру, в сентябре это слово использовали более чем в сто раз чаще, чем в прошлом году.

Составители отмечают, что были и другие словосочетания-претенденты, связанные с климатом. Среди них — climate action («борьба с изменением климата»), climate crisis («климатический кризис»), climate denial («отрицание изменений климата») и другие.

В начале ноября выражение года назвал словарь английского языка Collins. Им стала «климатическая забастовка» (climate strike). Во многом на это повлияла шведская экоактивистка Грета Тунберг, которая стала широко известна после своего обращения к мировым лидерам на саммите ООН по климату.

Составители Оксфордского словаря выбрали слово 2019 года, сообщается на сайте издания

Им стало выражение climate emergency («чрезвычайная климатическая ситуация»). Согласно определению, которое приводит словарь, это ситуация, требующая срочных мер для сокращения или сдерживания изменений климата, а также предотвращения необратимого ущерба окружающей среде.

The Oxford Word of the Year is … CLIMATE EMERGENCY.

‘Climate emergency’ is defined as ‘a situation in which urgent action is required to reduce or halt climate change and avoid potentially irreversible environmental damage resulting from it.’https://t.co/JLepdcgt0U pic.twitter.com/UKJqpa2KAJ

— Oxford Dictionaries (@OxfordWords) November 20, 2019

Что еще известно:

Словарь замечает, что в 2019 году в шорт-лист попали и другие словосочетания, связанные с климатом. Среди них — climate action («борьба с изменением климата»), climate crisis («климатический кризис»), climate denial («отрицание изменений климата») и другие.

Ранее слово 2019 года представили издатели британского толкового словаря Collins English Dictionary. Им стало выражение climate strike («климатическая забастовка»). Свой вклад в популяризацию этого словосочетания внесла шведская школьница Грета Тунберг.