A brief history of post-truth

The compound word post-truth exemplifies an expansion in the meaning of the prefix post— that has become increasingly prominent in recent years. Rather than simply referring to the time after a specified situation or event – as in post-war or post-match – the prefix in post-truth has a meaning more like ‘belonging to a time in which the specified concept has become unimportant or irrelevant’. This nuance seems to have originated in the mid-20th century, in formations such as post-national (1945) and post-racial (1971).

Post-truth seems to have been first used in this meaning in a 1992 essay by the late Serbian-American playwright Steve Tesich in The Nation magazine. Reflecting on the Iran-Contra scandal and the Persian Gulf War, Tesich lamented that ‘we, as a free people, have freely decided that we want to live in some post-truth world’. There is evidence of the phrase ‘post-truth’ being used before Tesich’s article, but apparently with the transparent meaning ‘after the truth was known’, and not with the new implication that truth itself has become irrelevant.

A book, The Post-truth Era, by Ralph Keyes appeared in 2004, and in 2005 American comedian Stephen Colbert popularized an informal word relating to the same concept: truthiness, defined by Oxford Dictionaries as ‘the quality of seeming or being felt to be true, even if not necessarily true’. Post-truth extends that notion from an isolated quality of particular assertions to a general characteristic of our age.

The Word of the Year for 2016 is surreal, with lookups of the word spiking for different reasons over the course of the year. Beginning with the Brussels terror attacks in March, major spikes included the days following the coup attempt in Turkey and the terrorist attack in Nice, with the largest spike in lookups for surreal following the U.S. election in November.

Surreal is looked up spontaneously in moments of both tragedy and surprise, whether or not it is used in speeches or articles. This year, other spikes corresponded to a variety of events, from Prince’s death to the Pulse shooting in Orlando; from the Brexit vote to commentary about the presidential debates.

Surreal was also used in its original sense, referring to incongruous or unrealistic artistic expression, in reviews for the movie «The Lobster.»

The definition of surreal is: “marked by the intense irrational reality of a dream.” It’s a relatively new word in English, only dating back to the 1930s, derived from descriptions of the artistic movement of the early 1900s known as surrealism.

It’s a word that is used to express a reaction to something shocking or surprising, a meaning which is built into its parts: the “real” of surreal is preceded by the French preposition sur, which means “over” or “above.” When we don’t believe or don’t want to believe what is real, we need a word for what seems “above” or “beyond” reality. Surreal is such a word.

For more information on how we chose this year’s Word of the Year, go behind the scenes with editor-at-large Peter Sokolowski. And don’t miss our in-depth look at surreal.

Photo: 2015 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation

Spikes for revenant began in late 2015, with the release of “The Revenant,” starring Leonardo DiCaprio. Nominations and wins at the Golden Globes and Academy Awards kept the word in the news and in our lookup data into well into 2016.

Revenant means «one that returns after death or a long absence,» and comes from the French word that means «to return.» It was first used to mean «ghost,» «specter,» or «wraith,» and then developed the meaning «one who returns to a former place after prolonged absence»; both meanings seem to fit the film’s story.

It’s an unfamiliar word for most of us, which is probably the main reason for looking it up. The idea of returning from the dead, the word’s echo of covenant, and maybe even DiCaprio’s beard all give revenant a vaguely biblical character, but in fact the word doesn’t appear in the Bible. Its first use in English, coincidentally, is almost exactly contemporary with the real-life incident depicted in the film, in the early 1800s.

Icon spiked in April, in a moment of collective sadness at the news of Prince’s death.

Icon means “a person or thing widely admired especially for having great influence or significance in a particular sphere,” and is the root word of iconic and iconoclastic, both of which also showed smaller spikes during the same period. Icon originally simply referred to an image or a pictorial representation; later it took on a religious significance in much of its use. It then came to mean, more broadly, “a successful and admired person.”

It’s interesting that Prince should be described both with the words icon and iconoclast, which originally meant “one who destroys religious images”—or, in a sense, “one who destroys icons.”

In omnia paratus, the Latin phrase that means “ready for all things,” spiked when the Netflix revival of “Gilmore girls” was released. The phrase was first used back in the original run of the series as well, and has become a rallying cry for fans.

It’s pronounced in-AWM-nee-ah-pah-RAH-tooss.

Did he really say bigly? Is bigly even a word?

Donald Trump actually said big league and not bigly during the September 26 debate, as linguists were able to demonstrate with spectrogram analysis and evidence of Trump’s frequent use of big league as an adverb, as in: “I’m going to cut taxes big league.”

Since English speakers expect many adverbs to end in -ly, it’s easy to understand the confusion. It’s also true that we only give definitions for big league as a noun and adjective in the dictionary. Bigly is indeed a real word, but it is rarely seen (or heard).

All of which means that bigly stands out as the most looked-up word that was never actually used in 2016.

Hillary Clinton’s use of the word deplorables when describing “half of Trump supporters” sent many people to the dictionary to look up the word.

One reason some people may have looked up the word may be that it seems unfamiliar: deplorable is defined as an adjective meaning either “lamentable” or “deserving censure or contempt,” a synonym of “wretched” or “abominable.” But Clinton’s use in the plural, deplorables, marks the word as a noun—and deplorable is not defined as a noun in Merriam-Webster dictionaries. (Deplorableness is given as the noun form.)

In this case, it wasn’t just the news event that drove lookups: the word itself was newsworthy.

One of the broadcasters calling the final game of the World Series used the word irregardless on the air, and was roundly criticized on social media. Inevitably, many people looked it up; many posts on social media claimed that irregardless “isn’t a word.”

We never said that it isn’t a word, but we do advise strongly against using it. It’s labeled nonstandard, but it has appeared in print so frequently over the years that it has been included in the dictionary. The final words of our entry are: “Use regardless instead.”

Congressman Joe Kennedy introduced his former professor, Senator Elizabeth Warren, at the Democratic National Convention with an anecdote about his embarrassing first day of law school:

First day of law school. First class. The goal: escape unscathed. Three seconds in, I get the first question:

“Mr. Kennedy, what is the definition of assumpsit?”

“Uhhh…”

“Mr. Kennedy, you realize assumpsit was the first word in your reading?”

“Yes. I circled it because I didn’t know what it meant.”

“Mr. Kennedy, do you own a dictionary? That’s what people use when they don’t know a word.”

I never showed up unprepared for Professor Elizabeth Warren again.

—Joseph P. Kennedy III, as quoted in The Boston Globe, 26 July 2016

Since Kennedy never actually explained what assumpsit means, lookups for assumpsit skyrocketed in the minutes after he told his story; the following morning, lookups were still high at an astonishing 92,000% increase over the previous month’s average.

Assumpsit is a legal term defined as an express or implied promise or contract, the breach of which may be grounds for a lawsuit.

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg used the French expression faute de mieux in a written opinion for a decision announced in June. Lookups for the phrase spiked high.

The concurring opinion was written when the Supreme Court struck down a Texas law that would have closed all but nine abortion clinics in the state:

When a state severely limits access to safe and legal procedures, women in desperate circumstances may resort to unlicensed rogue practitioners, faute de mieux, at great risk to their health and safety.

Faute de mieux is pronounced foht-duh-MYUH and means “for lack of something better.” Foreign phrases that are frequently used in English are included in the dictionary.

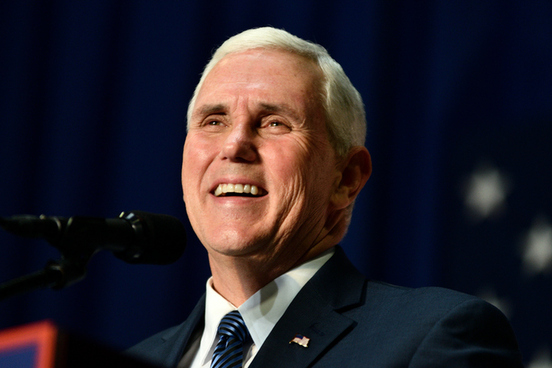

Lookups for feckless, meaning “weak” or “ineffective,” spiked dramatically after Mike Pence used it in the vice-presidential debate in October.

After Mr. Kaine mentioned Mr. Trump’s frequent praise of Vladimir Putin and the Trump campaign’s “shadowy connections with pro-Putin forces,” Mr. Pence blamed the Obama administration’s “weak and feckless foreign policy” for Russian aggression.

—Nicholas Confessore and Matt Flegenheimer, The New York Times, 4 Oct. 2016

Feckless has become a favorite of U.S. politicians in recent years. Both Senator John McCain and Governor Chris Christie, among others, have used the word in highly publicized speeches or debates.

It comes from the Scottish word feck, which can mean “value” or “worth,” and so a thing that is feckless may also be said to be “worthless.»

In case you’re wondering, the word feckful, meaning “efficient,” “sturdy,” or ‘”powerful,” does exist, though it is very rarely used.

Oxford Dictionaries kicked off “word of the year” season by anointing their pick on Tuesday: post-truth.

The word, selected by Oxford’s editors, does not need to be coined in the past year but it does have to capture the English-speaking public’s mood and preoccupations. And that makes this one an apt choice for countries like America and Britain, where people lived through divisive, populist upheavals that often seemed to prize passion above all else—including facts.

post-truth: relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.

The word dates back to at least 1992, but Oxford saw its usage explode by 2,000% this year, based on their ongoing monitoring of how people are using English. Oxford notes that the phrase post-truth politics has enjoyed particular popularity of late. “It’s not surprising that our choice reflects a year dominated by highly-charged political and social discourse,” said Casper Grathwohl, president of Oxford Dictionaries. “Fueled by the rise of social media as a news source and a growing distrust of facts offered up by the establishment, post-truth as a concept has been finding its linguistic footing for some time.” And, he suggests, it may become a defining word of our time.

The selection is a rather somber follow-up to last year’s choice — 😂 — an emoji shedding tears of joy that reflected people’s playfulness in embracing changing language more than their pains in weathering changing politics. Although the short list contains some light-hearted concepts, it too reflects a big truth about 2016: it has been a hard year full of soul-searching and separation, marked by transition and lines between self and other.

The Short List

adulting noun, informal: The practice of behaving in a way characteristic of a responsible adult, especially the accomplishment of mundane but necessary tasks. (See: more on why millennials have embraced the term.)

alt-right noun: An ideological grouping associated with extreme conservative or reactionary viewpoints, characterized by a rejection of mainstream politics and by the use of online media to disseminate deliberately controversial content. (See: TIME’s cover on Internet trolling.)

Brexiteer noun, informal: A person who is in favor of the United Kingdom withdrawing from the European Union. (See: how news outlets around the world covered that story.)

chatbot noun: A computer program designed to simulate conversation with human users, especially over the Internet. (See: an explanation on why these are taking over all the things.)

coulrophobia noun: Extreme or irrational fear of clowns (See: what an odd October diversion the “clown craze” was.)

glass cliff noun: Used with reference to a situation in which a woman or member of a minority group ascends to a leadership position in challenging circumstances where the risk of failure is high. (See: the plights of women who rise in politics.)

hygge noun: A quality of cosiness and comfortable conviviality that engenders a feeling of contentment or well-being, regarded as a defining characteristic of Danish culture. (See: how popular the idea has become in British culture.)

Latinx noun: A person of Latin American origin or descent, used as a gender-neutral or non-binary alternative to Latino or Latina. (See: the rise of non-binary identities.)

woke adjective, US informal: [originally in African-American usage] Alert to injustice in society, especially racism. (See: a must-read on what you should consider before using the term.)

Contact us at letters@time.com.

After much discussion, debate, and research, the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2016 is post-truth – an adjective defined as ‘relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief’.

Why was this chosen?

The concept of post-truth has been in existence for the past decade, but Oxford Dictionaries has seen a spike in frequency this year in the context of the EU referendum in the United Kingdom and the presidential election in the United States. It has also become associated with a particular noun, in the phrase post-truth politics.

Post-truth in 2016

Post-truth has gone from being a peripheral term to being a mainstay in political commentary, now often being used by major publications without the need for clarification or definition in their headlines.

Obama founded ISIS. George Bush was behind 9/11. Welcome to post-truth politics https://t.co/QYrx76krF0

— The Economist (@TheEconomist) November 1, 2016

‘We’ve entered a post-truth world and there’s no going back’ https://t.co/FyCdlybOQ6

— The Independent (@Independent) November 8, 2016

The term has moved from being relatively new to being widely understood in the course of a year — demonstrating its impact on the national and international consciousness. The concept of post-truth has been simmering for the past decade, but Oxford shows the word spiking in frequency this year in the context of the Brexit referendum in the UK and the presidential election in the US, and becoming associated overwhelmingly with a particular noun, in the phrase post-truth politics.

A brief history of post-truth

The compound word post-truth exemplifies an expansion in the meaning of the prefix post- that has become increasingly prominent in recent years. Rather than simply referring to the time after a specified situation or event – as in post-war or post-match – the prefix in post-truth has a meaning more like ‘belonging to a time in which the specified concept has become unimportant or irrelevant’. This nuance seems to have originated in the mid-20th century, in formations such as post-national (1945) and post-racial (1971).

Post-truth seems to have been first used in this meaning in a 1992 essay by the late Serbian-American playwright Steve Tesich in The Nation magazine. Reflecting on the Iran-Contra scandal and the Persian Gulf War, Tesich lamented that ‘we, as a free people, have freely decided that we want to live in some post-truth world’. There is evidence of the phrase ‘post-truth’ being used before Tesich’s article, but apparently with the transparent meaning ‘after the truth was known’, and not with the new implication that truth itself has become irrelevant.

A book, The Post-truth Era, by Ralph Keyes appeared in 2004, and in 2005 American comedian Stephen Colbert popularized an informal word relating to the same concept: truthiness, defined by Oxford Dictionaries as ‘the quality of seeming or being felt to be true, even if not necessarily true’. Post-truth extends that notion from an isolated quality of particular assertions to a general characteristic of our age.

The shortlist

Here are the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year shortlist choices, and definitions:

adulting, n. [mass noun] informal the practice of behaving in a way characteristic of a responsible adult, especially the accomplishment of mundane but necessary tasks.

alt-right, n. (in the US) an ideological grouping associated with extreme conservative or reactionary viewpoints, characterized by a rejection of mainstream politics and by the use of online media to disseminate deliberately controversial content. Find out more about the word’s rise.

Brexiteer, n. British informal a person who is in favour of the United Kingdom withdrawing from the European Union.

chatbot, n. a computer program designed to simulate conversation with human users, especially over the Internet.

coulrophobia, n. [mass noun] rare extreme or irrational fear of clowns.

glass cliff, n. used with reference to a situation in which a woman or member of a minority group ascends to a leadership position in challenging circumstances where the risk of failure is high. Explore the word’s history from one of the inventors of the term, Alex Haslam.

hygge, n. [mass noun] a quality of cosiness and comfortable conviviality that engenders a feeling of contentment or well-being (regarded as a defining characteristic of Danish culture):

Latinx, n. (plural Latinxs or same) and adj. a person of Latin American origin or descent (used as a gender-neutral or non-binary alternative to Latino or Latina); relating to people of Latin American origin or descent (used as a gender-neutral or non-binary alternative to Latino or Latina).

woke, adj. (woker, wokest) US informal alert to injustice in society, especially racism. Read more about the evolution of woke throughout 2016.

See more from Word of the Year

Each year, several major lexicographers release their word of the year—the term that, among the most frequently looked-up words during the previous twelve months, has most prominently captured the zeitgeist. This post discusses the 2016 selections.

Merriam-Webster selected surreal, a word apropos for a year in which various seemingly irrational, inexplicable events occurred. The dictionary company announced that a significant spike in the number of people who looked up the word occurred three times during the year, including after Election Day in the United States.

Surreal was coined about a hundred years ago by a group of artists responding to Sigmund Freud’s recent explication of the concept of the unconscious mind; they called their movement surrealism, and the art the surrealists produced was marked by fantastic and incongruous imagery or elements. The prefix sur-, meaning “above” or “over,” is seen in other words such as surname (“beyond name”) and surrender (“give over”).

Among the other words Merriam-Webster noted as being frequently looked up during the year include revenant, meaning “one who returns”; the attention was prompted by its use in the title of a movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio as a man left for dead who seeks vengeance on those who abandoned him.

Another is feckless, meaning “ineffective” or “irresponsible.” Derived from the Scots word feck, an alteration of effect, the word gained attention when Mike Pence, the US vice president–elect, uttered it in a debate against his Democratic Party rival, Tim Kaine. (Feck and feckful are now obsolete, and feckless is rare.)

Icon, ultimately from the Greek verb eikenai, meaning “resemble,” was yet another; the death of the musician who (usually) called himself Prince (born Prince Rogers Nelson) prompted lookups for this word meaning “idol” or “symbol.” (Interestingly, for a time he employed a glyph, or symbol, in place of his name.) Words with icon as a root include iconography, meaning “depiction of icons,” and iconoclast, meaning “destroyer of icons.”

The Oxford English Dictionary chose as its Word of the Year post-truth, signifying the growing trend toward subordination of objective truth to appeals to emotion and personal belief when weighing decisions. (In American English, the prefix post is usually not hyphenated, but British English tends to retain the hyphen in such usage, and usage of this word in the United States tends to follow that style.)

Meanwhile, the word selected by Dictionary.com to represent the preceding year is xenophobia, meaning “fear or hatred of strangers or the unknown.” (In Greek, xenos means “stranger”—but also “guest”—and phobia is derived from the Greek word phobos, meaning “fear.”)