The Words of the 2010s

Merriam-Webster’s Word of the Year is a glimpse into the minds of Merriam-Webster’s readers: it’s determined by what words dictionary users have been searching. As the year winds down, we pull up our data and sort through the top lookups of the previous 12 months, putting aside perennial favorites like affect and effect, and zeroing in on the words that are significant for that particular year because of the frequency with which they were looked up compared to previous years. The top word of the year is one that has had multiple spikes in lookups, in addition to being more frequently looked up overall. The runners-up include others that were similarly popular throughout the year, as well as one-hit wonders—words that had sudden dramatic spikes in lookups because of some political, cultural, or natural event. What follows is a summary of the Words of the Year for the 2010s, with each year’s top word and one runner-up that our editors thought was especially significant. As a group, they tell us a lot about what was on our minds during the second decade of the 21st century.

Economic recovery from the Great Recession was the big story at the beginning of this decade. (Indeed, the Word of the Year for 2008, in the immediate shock of the crisis, was bailout, so economic concerns even surpassed a presidential race in terms of public interest in vocabulary.) For 2010, the Word of the Year was austerity, a term used both in the context of government spending during the recovery and in the context of household budgets under the strain of unemployment and underemployment. Like most technical, legal, and medical terms, austerity comes from Latin, in this case the root word means “harsh” or “severe.”

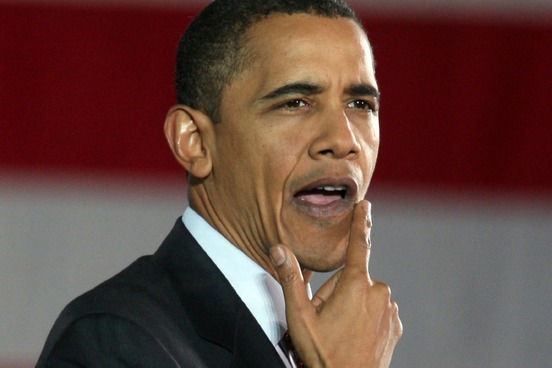

The word shellacking, from among the top words of the year, was looked up in a rare political context: after Democratic defeats in the midterm elections, President Obama used the word to describe the loss.

A sober President Obama acknowledged Wednesday that he took «a shellacking» in the midterm election and that his once highflying relationship with the American voter had hit rocky times.

«There is an inherent danger in being in the White House and being in the bubble,» said the president, whose party on Tuesday lost control of the House in a historic Republican wave. The GOP is expected to gain at least 60 seats, the biggest increase in more than seven decades. Democrats barely clung to their Senate majority.

— Liz Halloran, NPR, 3 Nov. 2010

Shellacking is a colorful word that has both an emphatic and an informal quality, and, while it’s probable that many people looked the word up for its meaning, we suspect many others were curious about whether it was in the dictionary at all, or whether its informality tested the limits of presidential dignity. It comes from the verb shellac, which originally meant “to coat with shellac” or “to varnish,” it came to mean “to defeat decisively” around 1930.

The word pragmatic seemed to catch the spirit of the times in 2011, at least in politics, where Congress passed measures to control the federal budget and President Obama oversaw explanations and rollout of the recently passed Affordable Care Act. Pragmatic has since become something of an evergreen word, one that we see high in our rankings on a consistent basis. Like many such words, it has classical roots and an abstract meaning.

Vitriol became a top lookup of the year following the shooting in Arizona that injured Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords; the motivation for the attack was described as “political vitriol,” and the word’s use in press coverage sent many people to the dictionary.

Vitriol or oil of vitriol refers to a liquid that burns, and its more recent figurative use has become much more common in the language, essentially referring to words that “burn” metaphorically.

But, in addition to the natural distancing of metaphorical language, we also find that vitriol, like so many Latin words, seems to be a more abstract and less emotional term than, say, hatred. When writing about a difficult and sensitive topic like politically motivated violence, the more neutral and technical tone of the Latin-based word is a frequent choice of journalists and headline writers. Abstract words with classical roots are among the most frequently looked-up words in the dictionary (think pragmatic or integrity or ubiquitous), and the effect of emotional distancing in this instance may have led many to find out more about the specific meaning of this word.

During a presidential election year, it’s no surprise that terms from politics dominated the list in 2012. For the first and only time, we named two Words of the Year: socialism and capitalism. The two words showed such a close parallel rise in our statistics that it seems likely that many dictionary users looked them up sequentially in order to compare them.

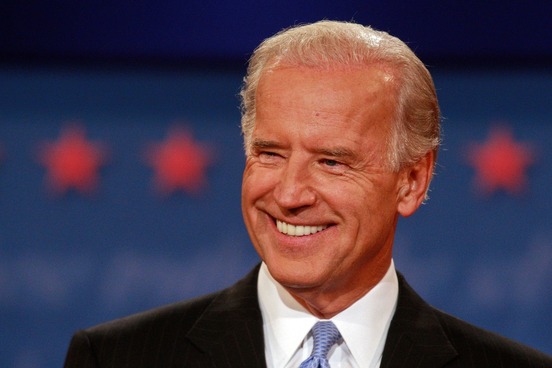

Malarkey was used by Vice President Joe Biden during the vice-presidential debate with Paul Ryan, and it spiked in our data as many people checked to learn its precise definition or to see if this informal word had a dictionary entry (it does). It turns out that this is a word that is frequently used by Joe Biden and has become closely associated with him.

We think that the informal quality of this word resonated on several levels with its use by Joe Biden. First of all, the debate itself was conducted while the candidates were seated at a table. One theory about the origin of malarkey is that it is derived from an Irish family name; although this is hard to prove, the word’s use among Irish Americans is well established, and since both Biden and Paul Ryan have Irish ancestry, its use in this context made it seem comfortable and appropriate—and a bit as though the older Biden positioned himself as the wiser older relative lecturing a young man. Finally, there’s something vaguely naughty about malarkey, which corresponds to Joe Biden’s relaxed speaking style. It’s possible that many people wanted to know whether the word is considered to be vulgar or offensive, in addition to finding its definition.

Curiosity is often piqued by events in the news, but dictionary data often reflects what’s troublesome or complex about English, including abstract words that have broad and varied applications. Culture (more on that later) is one such word, and it has become a perennial evergreen on our lookup list. So has science, our Word of the Year for 2013. It was a year without a single big story like a presidential election or economic recession, and yet this word’s rise in our data accompanied a national discussion about big issues like faith in science, climate change, and Mars exploration, as well as more focused stories like identifying the DNA of Richard III and assessing the role of Malcolm Gladwell’s successful books in popularizing scientific research.

A big story in 2013 was the ongoing investigation into the dangers of concussions in sports, especially football, and the word cognitive was looked up in large numbers, often in this context. Cognitive is often paired with impairment, performance, function, symptoms, and even injury.

This story has only grown as public awareness of these dangers in football has increased. Indeed, since 2013, a feature film and several documentaries have given more detail and exposure to this phenomenon. We think that a combination of the popularity of football from middle school teams to the NFL in addition to the medical and technical nature of the Latin-based word cognitive contributed to the rise in lookups.

Our Word of the Year for 2014 was culture, a word that had annual spikes at back-to-school time (along with diversity and plagiarism), but was looked up much more frequently throughout the year. Culture conveys a kind of academic attention to systematic behavior and allows us to identify and isolate an idea, issue, or group: we speak of a «culture of transparency» or «consumer culture.» Culture can be either very broad (as in «western culture» or “corporate culture”) or very specific (as in «postmodern culture» or «Mexican culture»).

It seemed that culture moved from the classroom syllabus to the conversation at large in 2014, appearing in headlines and analyses across a wide swath of topics.

Occasionally, a word used as the title of a movie will send people to the dictionary—one prominent example is revenant. In 2014, the horror sequel Insidious 3 triggered curiosity about insidious. The word also spiked in response to two other stories during the year: coverage of increasingly sophisticated malware attacks (described as “insidious”), and the medical use of insidious (“developing so gradually as to be well established before becoming apparent”) used to describe the disease Ebola following the death of the first person diagnosed in the U.S.

It’s rare for us to see such diverse triggers for a single word in a given year. The abstract quality and Latin origin of insidious certainly put it in a category of word that is frequently looked up, and its own etymology—it comes from the Latin word meaning “ambush”—gives it a tone that is at times technical and at others deadly serious.

For the rest of the 2014 Word of the Year shortlist, click here.

2015 Word of the Year — -Ism

In 2015, a group of 7 words all sharing the same suffix—-ism—were looked up with significant frequency, resulting in the choice of -ism itself as the Word for the Year. Socialism was the most looked up of the seven, as presidential candidate Bernie Sanders’ identification as a «democratic socialist» kept the word in the national conversation. The other six -ism words so prominent in the public’s consciousness were fascism, racism, feminism, communism, capitalism, and terrorism.

Our editor choice for the 2015 runner-up is a word that refers to an age-old institution: marriage. In June of that year the Supreme Court ruled that same-sex couples can marry nationwide, shifting the legal meaning of the word marriage itself in many jurisdictions—and keeping the word in our top lookups.

The decision, which was the culmination of decades of litigation and activism, set off jubilation and tearful embraces across the country, the first same-sex marriages in several states, and resistance — or at least stalling — in others. It came against the backdrop of fast-moving changes in public opinion, with polls indicating that most Americans now approve of the unions.

— Adam Liptak, The New York Times, 26 June 2015

For the rest of the 2015 Word of the Year shortlist, click here.

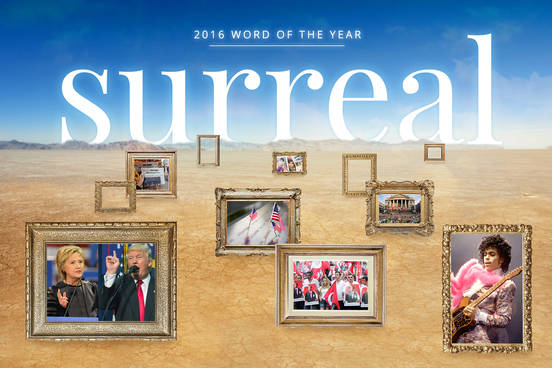

The word surreal, defined as “marked by the intense irrational reality of a dream,” was Merriam-Webster’s 2016 Word of the Year. Surreal is often looked up in moments of both tragedy and surprise, as people search for just the right word to bring order to abstract thoughts, emotions, or reactions. In 2016 lookups of the word followed the Brussels and Nice terror attacks, the Pulse shooting in Orlando, the coup attempt in Turkey, the Brexit vote, and the U.S. presidential election.

The word bigly saw a dramatic increase in lookups in 2016 when then-candidate Donald Trump was thought to have used the word during a presidential debate. As UC Berkeley linguist Susan Lin demonstrated with spectrogram analysis and evidence, Mr. Trump had in fact said not bigly but big league. The «bigly» cat, however, was out of the bag: the formerly obscure adverb bigly was not uncommon in news and commentary for the remainder of the decade. It’s our runner-up pick because as lexicographers, we find it fascinating that a word can go from obscurity to prominence despite not being in fact used in the instance (and subsequent instances) that boosted it into public consciousness.

For the rest of the 2016 Word of the Year shortlist, click here.

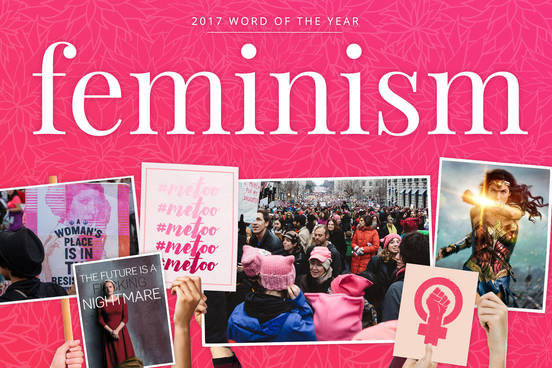

Feminism, defined in this dictionary as «the theory of the political, economic, and social equality of the sexes» and «organized activity on behalf of women’s rights and interests,» was the Word of the Year in 2017. Although feminism is frequently a top lookup, 2017 was a banner year for the word: from the Women’s Marches in January to the ongoing revelations that fueled the #MeToo movement, the word feminism was in the ether that year—and in the search bar of dictionary users.

The ten hurricanes of 2017 meant that the word hurricane was also on dictionary users’ minds that year. Four of the year’s hurricanes were so deadly and destructive—Harvey, Irma, Maria, and Nate—that their names were officially retired. With storms affecting the lives of millions of people we think it’s only fitting that hurricane should be the 2017 runner-up. The term hurricane is a technical designation; the term is defined in this dictionary as «a tropical cyclone with winds of 74 miles (119 kilometers) per hour or greater that occurs especially in the western Atlantic, that is usually accompanied by rain, thunder, and lightning, and that sometimes moves into temperate latitudes.»

For the rest of the 2017 Word of the Year shortlist, click here.

The Word of the Year in 2018 was justice, a term at the center of many of our national debates that year—debates about racial justice, social justice, criminal justice, economic justice. The question of just what exactly we mean when we use the word justice was part of the discussion. Particular technical uses of justice were also prominent, as references to the Justice Department (often referred to simply as «Justice») were a constant in the news, and confirmation hearings for a new Supreme Court justice had the nation’s attention.

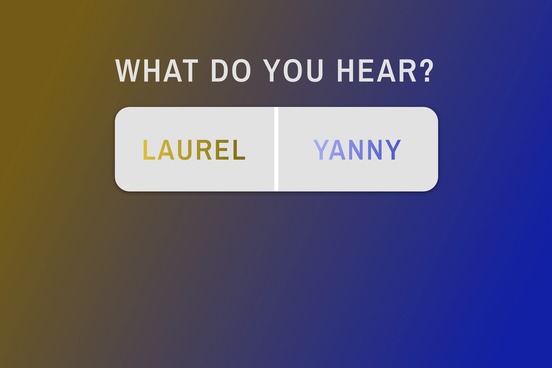

The May 2018 jump in lookups for laurel related to an experience many of us were sharing, concerning a fascinating audio clip that was dividing netizens into two distinct group: those who heard «laurel» and those who heard «yanny.» (The clip came from the audio pronunciation file at Vocabulary.com’s entry for laurel.) Linguists bounded in to explain the phenomenon—it has to do with whether lower or higher frequencies are more prominent, for an individual or because of audio quality—and the New York Times built a fun little tool that makes it possible for listeners to hear both. It’s our runner-up pick for the year because it demonstrates how we are all so invested—and interested—in our own personal experiences with language.

For the rest of the 2018 Word of the Year shortlist, click here.

2019 Word of the Year — They

The Word of the Year for 2019 was one of the most common words in the English language: they. Increasingly over the decade a subject of study and commentary, the pronoun they got an expanded definition in 2019—»used to refer to a single person whose gender identity is nonbinary»—but lookups for the word had increased dramatically over the previous year before that addition was announced. When something so basic to a language as a personal pronoun takes on new meaning, the speakers of the language are going to notice—and they’re going to look to their dictionary for guidance.

As we looked back on the quickly receding year of 2019, the runner-up that stood out among all the others was clear to our editors: impeach. The word had its biggest spike in lookups after we’d announced our words for the year, when the U.S. House of Representatives approved two articles of impeachment against President Donald Trump on December 18th. That largest spike followed what had already been a 129% increase in lookups over the previous year. Impeach is defined in several ways, including “to charge with a crime or misdemeanor” and “to cast doubt on.” The former of these carries the additional specific meaning of “to charge (a public official) before a competent tribunal with misconduct in office”; the latter is often narrowed as well, with the meaning “to challenge the credibility or validity of.” Although frequently thought of as meaning «to remove from office,» impeach has a precise legal use in cases such as this, in which the action describes a step in removing an official from office, but does not refer to the removal itself.

For the rest of the 2019 Word of the Year shortlist, click here.

Published November 22, 2010

The times are certainly changing, and you can see how much by discovering our 2020 Word of the Year.

After hours of calculation, deliberation, and lexical prestidigitation, we are pleased to reveal our selection for the 2010 Word of the Year.

In 2010, millions of people visited Dictionary.com to learn the right spelling, pronunciation, or definition of millions of words. Our Word of the Year directly reflects the hard work of our users—a word that experienced a surge of look-ups in the past 12 months. The word is change. It’s not trendy, funny, nor was it coined on Twitter, but we think it tells a real story about how our users define 2010.

Change of course has two common meanings: 1. “To make the form, nature, content, future course, etc., of (something) different from what it is or from what it would be if left alone.” 2. “Coins of low denomination.”

This isn’t 2008, and “change” is no longer a campaign slogan. Yet it still captures the popular imagination. Why? The national debate can arguably be summarized by the question: In the past two years, has there been enough change? Has there been too much? Meanwhile, many Americans continue to face change in their homes, bank accounts and jobs. Only time will tell if the latest wave of change Americans voted for in the midterm elections will result in a negative or positive outcome.

The change jangling in your pocket may explain the desire to know the meaning of “change” better than any specific event. These are tough times.

The runner-ups for Word of the Year provide a fuller picture: success, unique, character, also surged in the number of look-ups in 2010. If you can’t define success by material prosperity, what’s left? We can’t say for certain, but one hopes that increases in unique, and character reflect a search for personal growth.

You may have noticed that refudiate, a coinage by Sarah Palin, has been receiving tons of attention in the press as one of the words with the most buzz in 2010. A crucial requirement for our selection is that a word candidate exist in our dictionaries. At present, refudiate is more of a phenomenon than a dictionary entry. Not that we refuse or repudiate the malapropism; the fuss around refudiate has been one of the highlights of the Hot Word.

It may make some people gag – and others feel a flush of enthusiasm – but the term «big society» has made its mark in the current year.

Coined (or at any rate hammered almost to death) by the prime minister, David Cameron, and other coalition politicians, it has been chosen by Oxford academics as the Word of 2010.

The award for the word of the year, which has been relaxed in the last decade to include short phrases, was given last night after a sharp final tussle with vuvuzela and Boris bike.

Lexicographers at Oxford University Press rejected another 11 shortlisted terms which vied to «express in shorthand» the dominant tone and issues of the last 12 months.

«The concept of big society was a clear winner because it embraces so much of the year’s political and economic mood,» Susie Dent, of Oxford Dictionaries, said. «It has also begun to take on a life of its own, and that’s a sure sign of linguistic success.»

Usage of big society started gently in the runup to the election campaign, but took off after Cameron used it as a synonym for liberation in July.

He suggested, in a speech delivered in Liverpool, that it meant «the biggest, most dramatic redistribution of power to date from elites in Whitehall to the man and woman on the street».

The phrase has since acquired an increasing mystique as analysts try to work out exactly what this means. Dent said: «People take it in different ways, and that is another advantage for a would-be Word of the Year.»

The term takes over from a quartet which shared the title last year, when the dictionary’s staff reached a stalemate in the final judging.

Tweetup, simples, staycation and jegging flew their flags for Twitter, TV advertising, British holidays and women’s leggings, but none emerged as a clear winner.

Earlier words of the year have included bovvered, credit crunch and footprint, which was also runner-up in 2007’s Word of the Century So Far.

That title went to 9/11 in both Britain and the US. This year’s American winner is refudiate, the mash of refute and repudiate invented by Sarah Palin.

Dent said entrants did not have to be new coinings – although they often have been – and victory did not often mean that the word or phrase would be around in the long term, or eventually get a place in the Oxford English Dictionary.

«The winner and all the words on our shortlist give a telling snapshot of the year’s preoccupations,» she said.

«They also demonstrate the most successful processes behind language change – wordplay, blending, and the adoption of foreign terms are all there.»

Back to Word of the Year 2022

Word of the Year 2010

Posted on 23 December 2013

The Committee’s choice of Word of the Year 2010 is:

googleganger |

|

noun a person with the same name as oneself, whose online references are mixed with one’s own among search results for one’s name. [google + (doppel)ganger ] |

The Committee would like to give honourable mention to:

vuvuzela |

|

noun a plastic horn (def. 13), up to one metre in length, which emits a loud buzzing sound; commonly played in South Africa by fans at soccer games. [? Zulu vuvu to make a noise] |

The Macquarie Dictionary Word of the Year Committee comprises:

Dr Michael Spence, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Sydney

Professor Stephen Garton, Pro-Vice-Chancellor, University of Sydney

Evan Hannah, Group Editorial General Manager, News Ltd.

Les Murray, renowned Australian poet

Susan Butler, Publisher of the Macquarie Dictionary

The People’s Choice Award for 2010 goes to:

shockumentary |

|

noun (plural shockumentaries) 1. a documentary film or television show featuring footage of accidents or violence. 2. a documentary film or television show which gives damaging information about government bodies, industries, etc., often presented in such a way as to magnify the inherent shock value of the facts. [shock1 + (doc)umentary] |

Category winners:

Download the pdf below to view all the entries considered for Word of the Year 2010.

Download:

2010_entries.pdf

Once again the American Dialect Society has performed its not-so-solemn duty in anointing a Word of the Year (aka WOTY), and the 2010 winner is app, as in, «There’s an app for that.» I’m just back from Pittsburgh, where the ADS held its annual meeting in conjunction with the Linguistic Society of America, and I’ve got the full report.

I’ve provided on-the-spot coverage of the WOTY vote in past years (for 2008 it was bailout, and for 2009 it was tweet), but this year I played a more active role in the proceedings as the incoming chair of the ADS New Words Committee. (That title means I’ll also be keeping track of neologisms for «Among the New Words,» a quarterly feature in the ADS journal American Speech.) I assisted ADS Executive Secretary Allan Metcalf in presiding over the selection and making sure all the votes were tallied.

On Thursday night, as I reported here, we had held a meeting to nominate words in a number of various categories. Those nominees were only the starting point in the freewheeling gathering to vote for the winners on Friday. We had lively discussions for each category, culminating in the final WOTY selection, with each winner determined by a show of hands from the approximately 125 members of ADS and LSA who filled the room. (You can follow the photos in the LSA’s Flickr feed to get a sense of the action, and there’s also some video below.)

Allan welcomed the audience to «the Oscars of new words,» and then we were on our way with the first category, the Most Useful Word of the Year. Nominees included vuvuzela, the South African noisemaker from the World Cup, the verb fat-finger (to mistype, from hitting more than one key at once), nom (an onomatopoetic expression of pleasure in eating, in the manner of Cookie Monster’s «om nom nom»), and junk (as in BP’s failed junk shot to curb the Gulf oil spill, the junk status of Greece’s credit rating, and the immortal line, «Don’t touch my junk!» in protest of the new TSA pat-down procedure). Junk and nom were the top vote-getters, but since neither had a majority, a run-off was held, and nom emerged the winner. (If you’re mystified by nom, check out Know Your Meme for an explanation, and there’s some linguistic discussion on the phonetics blog of John Wells and The Economist’s Johnson blog.)

Next came the Most Creative category, with candidates including -sauce (a playfully intensive combining form, as in weak-sauce and awesome-sauce), spillion (an immense number, as in gallons of oil spilled in the Gulf of Mexico), prehab (preemptive rehab à la Charlie Sheen), and phoenix firm (a troubled firm that declares bankruptcy and then reinvents itself). In a runoff, prehab beat out -sauce.

In the Most Unnecessary category, everyone’s favorite Palinism, refudiate, won handily. Then it was on to Most Outrageous, where the winner was gate rape, one of the more hyperbolic terms for what the TSA would prefer to call an «enhanced pat-down.» Enhanced pat-down was, in fact, in the running for Most Euphemistic (the favorite category of VT contributor Mark Peters), but it lost out to kinetic event, the Pentagon euphemism for a violent attack on forces in Afghanistan.

In the prestigious Most Likely to Succeed category, the winner was trend as a verb, meaning «to exhibit a burst of online buzz» (as in, «Justin Bieber is trending on Twitter right now»). That beat out such candidates as hacktivism (activism by means of computer hacking) and -pad as a suffix for tablet computers on the model of Apple’s iPad. This was followed by Least Likely to Succeed, which had a surprise winner that wasn’t on the original list but was instead nominated from the floor: culturomics, the confusing name for Google-aided research into the history of language and culture. (I picked apart the phonetic and semantic difficulties of culturomics here.)

We set up two special categories this year: Election Terms and Fan Words. Election Terms, with such expressions as man up, mama grizzly, and Obamacare, didn’t move the assembled throng, who ended up voting to toss out the entire category and move on. That took us to Fan Words, where gleek (a fan of the TV show «Glee») handily triumphed over belieber (a fan of Justin Bieber), little monster (a fan of Lady Gaga), Twihard (a fan of the «Twilight» series), and Yat Dat (a native-born fan of the New Orleans Saints). Allan Metcalf, who admitted to being mystified by the candidates in this category, declared, «It’s gleek to me!»

Finally it was time for the biggie, the overall Word of Year category. Two of the Most Useful candidates were nominated again for WOTY: nom and junk. I had laid out a case for junk as a WOTY contender in my most recent On Language column in The New York Times Magazine, and my argument was convincing enough for some in the room. Nom was championed by several of the younger scholars in attendance, notably Maryam Bakht of Hunter College, whose stump speech included the line, «A vote for nom is a vote for a happy word!» Bill Kretzschmar of the University of Georgia threw another word into the mix: app, the abbreviated form of «(computer) application» that has become so omnipresent in the past few years thanks to apps on the latest generation of computers and mobile devices. Apple’s iPhone in particular has brought app into the public consciousness with its advertising slogan, «There’s an app for that.»

Junk lost out to nom and app in initial voting, and in the subsequent runoff, app emerged victorious. The nom supporters were none too pleased (cries of «Lame!» and «Weak sauce!» could be heard), but the people had spoken: app was the 2010 Word of the Year.

When I wasn’t busy counting votes, I managed to record a few minutes of shaky video, capturing the nom vs. app showdown at the end of the meeting. Here it is, for your entertainment.

Update: For more on the selection, check out my interview with Voice of America here.