In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is de Goya and the second or maternal family name is Lucientes.

|

Francisco de Goya |

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Goya by Vicente López Portaña, c. 1826. Museo del Prado, Madrid |

|

| Born |

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes 30 March 1746 Fuendetodos, Aragon, Spain |

| Died | 16 April 1828 (aged 82)

Bordeaux, France |

| Known for | Painting, drawing |

| Notable work | List of paintings and engravings |

| Movement | Romanticism |

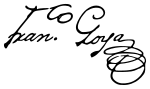

| Signature | |

|

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (; Spanish: [fɾanˈθisko xoˈse ðe ˈɣoʝa i luˈθjentes]; 30 March 1746 – 16 April 1828) was a Spanish romantic painter and printmaker. He is considered the most important Spanish artist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[1] His paintings, drawings, and engravings reflected contemporary historical upheavals and influenced important 19th- and 20th-century painters.[2] Goya is often referred to as the last of the Old Masters and the first of the moderns.[3]

Goya was born to a middle-class family in 1746, in Fuendetodos in Aragon. He studied painting from age 14 under José Luzán y Martinez and moved to Madrid to study with Anton Raphael Mengs. He married Josefa Bayeu in 1773. Their life was characterised by a series of pregnancies and miscarriages, and only one child, a son, survived into adulthood. Goya became a court painter to the Spanish Crown in 1786 and this early portion of his career is marked by portraits of the Spanish aristocracy and royalty, and Rococo-style tapestry cartoons designed for the royal palace.

He was guarded, and although letters and writings survive, little is known about his thoughts. He had a severe and undiagnosed illness in 1793 which left him deaf, after which his work became progressively darker and pessimistic. His later easel and mural paintings, prints and drawings appear to reflect a bleak outlook on personal, social and political levels, and contrast with his social climbing. He was appointed Director of the Royal Academy in 1795, the year Manuel Godoy made an unfavorable treaty with France. In 1799, Goya became Primer Pintor de Cámara (Prime Court Painter), the highest rank for a Spanish court painter. In the late 1790s, commissioned by Godoy, he completed his La maja desnuda, a remarkably daring nude for the time and clearly indebted to Diego Velázquez. In 1800–01 he painted Charles IV of Spain and His Family, also influenced by Velázquez.

In 1807, Napoleon led the French army into the Peninsular War against Spain. Goya remained in Madrid during the war, which seems to have affected him deeply. Although he did not speak his thoughts in public, they can be inferred from his Disasters of War series of prints (although published 35 years after his death) and his 1814 paintings The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808. Other works from his mid-period include the Caprichos and Los Disparates etching series, and a wide variety of paintings concerned with insanity, mental asylums, witches, fantastical creatures and religious and political corruption, all of which suggest that he feared for both his country’s fate and his own mental and physical health.

His late period culminates with the Black Paintings of 1819–1823, applied on oil on the plaster walls of his house the Quinta del Sordo (House of the Deaf Man) where, disillusioned by political and social developments in Spain, he lived in near isolation. Goya eventually abandoned Spain in 1824 to retire to the French city of Bordeaux, accompanied by his much younger maid and companion, Leocadia Weiss, who may or may not have been his lover. There he completed his La Tauromaquia series and a number of other, major, canvases.

Following a stroke which left him paralyzed on his right side, and with failing eyesight and poor access to painting materials, he died and was buried on 16 April 1828 aged 82. His body was later re-interred in the Real Ermita de San Antonio de la Florida in Madrid. Famously, the skull was missing, a detail the Spanish consul immediately communicated to his superiors in Madrid, who wired back, «Send Goya, with or without head.»[4]

Early years (1746–1771)[edit]

Birth house of Francisco Goya, Fuendetodos, Zaragoza

Francisco de Goya was born in Fuendetodos, Aragón, Spain, on 30 March 1746 to José Benito de Goya y Franque and Gracia de Lucientes y Salvador. The family had moved that year from the city of Zaragoza, but there is no record why; likely José was commissioned to work there.[5] They were lower middle-class. José was the son of a notary and of Basque origin, his ancestors being from Zerain,[6] earning his living as a gilder, specialising in religious and decorative craftwork.[7] He oversaw the gilding and most of the ornamentation during the rebuilding of the Basilica of Our Lady of the Pillar (Santa Maria del Pilar), the principal cathedral of Zaragoza. Francisco was their fourth child, following his sister Rita (b. 1737), brother Tomás (b. 1739) (who was to follow in his father’s trade) and second sister Jacinta (b. 1743). There were two younger sons, Mariano (b. 1750) and Camilo (b. 1753).[8]

His mother’s family had pretensions of nobility and the house, a modest brick cottage, was owned by her family and, perhaps fancifully, bore their crest.[7] About 1749 José and Gracia bought a home in Zaragoza and were able to return to live in the city. Although there are no surviving records, it is thought that Goya may have attended the Escuelas Pías de San Antón, which offered free schooling. His education seems to have been adequate but not enlightening; he had reading, writing and numeracy, and some knowledge of the classics. According to Robert Hughes the artist «seems to have taken no more interest than a carpenter in philosophical or theological matters, and his views on painting … were very down to earth: Goya was no theoretician.»[9] At school he formed a close and lifelong friendship with fellow pupil Martín Zapater; the 131 letters Goya wrote to him from 1775 until Zapater’s death in 1803 give valuable insight into Goya’s early years at the court in Madrid.[5][10]

Visit to Italy[edit]

At age 14 Goya studied under the painter José Luzán, where he copied stamps[which?] for 4 years until he decided to work on his own, as he wrote later on «paint from my invention».[11] He moved to Madrid to study with Anton Raphael Mengs, a popular painter with Spanish royalty. He clashed with his master, and his examinations were unsatisfactory. Goya submitted entries for the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in 1763 and 1766 but was denied entrance into the academia.[12]

Sacrifice to Pan, 1771. Colección José Gudiol, Barcelona

Rome was then the cultural capital of Europe and held all the prototypes of classical antiquity, while Spain lacked a coherent artistic direction, with all of its significant visual achievements in the past. Having failed to earn a scholarship, Goya relocated at his own expense to Rome in the old tradition of European artists stretching back at least to Albrecht Dürer.[13] He was an unknown at the time and so the records are scant and uncertain. Early biographers have him travelling to Rome with a gang of bullfighters, where he worked as a street acrobat, or for a Russian diplomat, or fell in love with a beautiful young nun whom he plotted to abduct from her convent.[14] It is possible that Goya completed two surviving mythological paintings during the visit, a Sacrifice to Vesta and a Sacrifice to Pan, both dated 1771.[15]

Portrait of Josefa Bayeu (1747–1812)

In 1771 he won second prize in a painting competition organized by the City of Parma. That year he returned to Zaragoza and painted elements of the cupolas of the Basilica of the Pillar (including Adoration of the Name of God), a cycle of frescoes for the monastic church of the Charterhouse of Aula Dei, and the frescoes of the Sobradiel Palace. He studied with the Aragonese artist Francisco Bayeu y Subías and his painting began to show signs of the delicate tonalities for which he became famous. He befriended Francisco Bayeu and married his sister Josefa (he nicknamed her «Pepa»)[16] on 25 July 1773. Their first child, Antonio Juan Ramon Carlos, was born on 29 August 1774.[17]

Madrid (1775–1789)[edit]

Francisco Bayeu (Josefa Bayeu’s brother), 1765 membership of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, and directorship of the tapestry works from 1777 helped Goya earn a commission for a series of tapestry cartoons for the Royal Tapestry Factory. Over five years he designed some 42 patterns, many of which were used to decorate and insulate the stone walls of El Escorial and the Palacio Real del Pardo, the residences of the Spanish monarchs. While designing tapestries was neither prestigious nor well paid, his cartoons are mostly popularist in a rococo style, and Goya used them to bring himself to wider attention.[18]

The cartoons were not his only royal commissions, and were accompanied by a series of engravings, mostly copies after old masters such as Marcantonio Raimondi and Velázquez. Goya had a complicated relationship to the latter artist; while many of his contemporaries saw folly in Goya’s attempts to copy and emulate him, he had access to a wide range of the long-dead painter’s works that had been contained in the royal collection.[19] Nonetheless, etching was a medium that the young artist was to master, a medium that was to reveal both the true depths of his imagination and his political beliefs.[20] His c. 1779 etching of The Garrotted Man («El agarrotado»[21]) was the largest work he had produced to date, and an obvious foreboding of his later «Disasters of War» series.[22]

Goya was beset by illness, and his condition was used against him by his rivals, who looked jealously upon any artist seen to be rising in stature. Some of the larger cartoons, such as The Wedding, were more than 8 by 10 feet, and had proved a drain on his physical strength. Ever resourceful, Goya turned this misfortune around, claiming that his illness had allowed him the insight to produce works that were more personal and informal.[23] However, he found the format limiting, as it did not allow him to capture complex color shifts or texture, and was unsuited to the impasto and glazing techniques he was by then applying to his painted works. The tapestries seem as comments on human types, fashion and fads.[24]

Other works from the period include a canvas for the altar of the Church of San Francisco El Grande in Madrid, which led to his appointment as a member of the Royal Academy of Fine Art.

Court painter[edit]

In 1783, the Count of Floridablanca, favorite of King Charles III, commissioned Goya to paint his portrait. He became friends with the King’s half-brother Luis, and spent two summers working on portraits of both the Infante and his family.[26] During the 1780s, his circle of patrons grew to include the Duke and Duchess of Osuna, the King and other notable people of the kingdom whom he painted. In 1786, Goya was given a salaried position as painter to Charles III.

Goya was appointed court painter to Charles IV in 1789. The following year he became First Court Painter, with a salary of 50,000 reales and an allowance of 500 ducats for a coach. He painted portraits of the king and the queen, and the Spanish Prime Minister Manuel de Godoy and many other nobles. These portraits are notable for their disinclination to flatter; his Charles IV of Spain and His Family is an especially brutal assessment of a royal family.[B] Modern interpreters view the portrait as satirical; it is thought to reveal the corruption behind the rule of Charles IV. Under his reign his wife Louisa was thought to have had the real power, and thus Goya placed her at the center of the group portrait. From the back left of the painting one can see the artist himself looking out at the viewer, and the painting behind the family depicts Lot and his daughters, thus once again echoing the underlying message of corruption and decay.

Goya earned commissions from the highest ranks of the Spanish nobility, including Pedro Téllez-Girón, 9th Duke of Osuna and his wife María Josefa Pimentel, 12th Countess-Duchess of Benavente, José Álvarez de Toledo, Duke of Alba and his wife María del Pilar de Silva, and María Ana de Pontejos y Sandoval, Marchioness of Pontejos. In 1801 he painted Godoy in a commission to commemorate the victory in the brief War of the Oranges against Portugal. The two were friends, even if Goya’s 1801 portrait is usually seen as satire. Yet even after Godoy’s fall from grace the politician referred to the artist in warm terms. Godoy saw himself as instrumental in the publication of the Caprichos and is widely believed to have commissioned La maja desnuda.[27]

Middle period (1793–1799)[edit]

La Maja Desnuda (La maja desnuda) has been described as «the first totally profane life-size female nude in Western art» without pretense to allegorical or mythological meaning.[28] The identity of the Majas is uncertain. The most popularly cited models are the Duchess of Alba, with whom Goya was sometimes thought to have had an affair, and Pepita Tudó, mistress of Manuel de Godoy. Neither theory has been verified, and it remains as likely that the paintings represent an idealized composite.[29] The paintings were never publicly exhibited during Goya’s lifetime and were owned by Godoy.[30] In 1808 all Godoy’s property was seized by Ferdinand VII after his fall from power and exile, and in 1813 the Inquisition confiscated both works as ‘obscene’, returning them in 1836 to the Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando.[31]

In 1798 he painted luminous and airy scenes for the pendentives and cupola of the Real Ermita (Chapel) of San Antonio de la Florida in Madrid. Many of these depict miracles of Saint Anthony of Padua set in the midst of contemporary Madrid.

At some time between late 1792 and early 1793 an undiagnosed illness left Goya deaf. He became withdrawn and introspective while the direction and tone of his work changed. He began the series of aquatinted etchings, published in 1799 as the Caprichos—completed in parallel with the more official commissions of portraits and religious paintings. In 1799 Goya published 80 Caprichos prints depicting what he described as «the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society, and from the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance, or self-interest have made usual».[32] The visions in these prints are partly explained by the caption «The sleep of reason produces monsters». Yet these are not solely bleak; they demonstrate the artist’s sharp satirical wit, particularly evident in etchings such as Hunting for Teeth.

While convalescing between 1793 and 1794, Goya completed a set of eleven small pictures painted on tin that mark a significant change in the tone and subject matter of his art, and draw from the dark and dramatic realms of fantasy nightmare. Yard with Lunatics is a vision of loneliness, fear and social alienation. The condemnation of brutality towards prisoners (whether criminal or insane) is a subject that Goya assayed in later works[33] that focused on the degradation of the human figure.[34] It was one of the first of Goya’s mid-1790s cabinet paintings, in which his earlier search for ideal beauty gave way to an examination of the relationship between naturalism and fantasy that would preoccupy him for the rest of his career.[35] He was undergoing a nervous breakdown and entering prolonged physical illness,[36] and admitted that the series was created to reflect his own self-doubt, anxiety and fear that he was losing his mind.[37] Goya wrote that the works served «to occupy my imagination, tormented as it is by contemplation of my sufferings.» The series, he said, consisted of pictures which «normally find no place in commissioned works.»

Goya’s physical and mental breakdown seems to have happened a few weeks after the French declaration of war on Spain. A contemporary reported, «The noises in his head and deafness aren’t improving, yet his vision is much better and he is back in control of his balance.»[38] These symptoms may indicate a prolonged viral encephalitis, or possibly a series of miniature strokes resulting from high blood pressure and which affected the hearing and balance centers of the brain. Symptoms of tinnitus, episodes of imbalance and progressive deafness are typical of Ménière’s disease.[39] It is possible that Goya had cumulative lead poisoning, as he used massive amounts of lead white—which he ground himself[40]—in his paintings, both as a canvas primer and as a primary color.[41][42]

Other postmortem diagnostic assessments point toward paranoid dementia, possibly due to brain trauma, as evidenced by marked changes in his work after his recovery, culminating in the «black» paintings.[43] Art historians have noted Goya’s singular ability to express his personal demons as horrific and fantastic imagery that speaks universally, and allows his audience to find its own catharsis in the images.[44]

Peninsular War (1808–1814)[edit]

The French army invaded Spain in 1808, leading to the Peninsular War of 1808–1814. The extent of Goya’s involvement with the court of the «intruder king», Joseph I, the brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, is not known; he painted works for French patrons and sympathisers, but kept neutral during the fighting. After the restoration of the Spanish King Ferdinand VII in 1814, Goya denied any involvement with the French. By the time of his wife Josefa’s death in 1812, he was painting The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808, and preparing the series of etchings later known as The Disasters of War (Los desastres de la guerra). Ferdinand VII returned to Spain in 1814 but relations with Goya were not cordial. The artist completed portraits of the king for a variety of ministries, but not for the king himself.

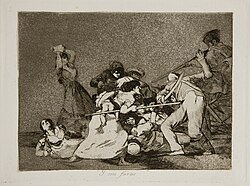

Although Goya did not make his intention known when creating The Disasters of War, art historians view them as a visual protest against the violence of the 1808 Dos de Mayo Uprising, the subsequent Peninsular War and the move against liberalism in the aftermath of the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in 1814. The scenes are singularly disturbing, sometimes macabre in their depiction of battlefield horror, and represent an outraged conscience in the face of death and destruction.[45] They were not published until 1863, 35 years after his death. It is likely that only then was it considered politically safe to distribute a sequence of artworks criticising both the French and restored Bourbons.[46]

The first 47 plates in the series focus on incidents from the war and show the consequences of the conflict on individual soldiers and civilians. The middle series (plates 48 to 64) record the effects of the famine that hit Madrid in 1811–12, before the city was liberated from the French. The final 17 reflect the bitter disappointment of liberals when the restored Bourbon monarchy, encouraged by the Catholic hierarchy, rejected the Spanish Constitution of 1812 and opposed both state and religious reform. Since their first publication, Goya’s scenes of atrocities, starvation, degradation and humiliation have been described as the «prodigious flowering of rage».[47]

-

-

Plate 4: Las mujeres dan valor (The women are courageous). This plate depicts a struggle between a group of civilians fighting soldiers.

-

Plate 5: Y son fieras (And they are fierce or And they fight like wild beasts). Civilian women fight against soldiers with spears and rocks.

-

Plate 46: Esto es malo (This is bad). A monk is killed by French soldiers looting church treasures. A rare sympathetic image of clergy generally shown on the side of oppression and injustice.[48]

-

Plate 47: Así sucedió (This is how it happened). The last print in the first group. Murdered monks lie by French soldiers looting church treasures.

His works from 1814 to 1819 are mostly commissioned portraits, but also include the altarpiece of Santa Justa and Santa Rufina for the Cathedral of Seville, the print series of La Tauromaquia depicting scenes from bullfighting, and probably the etchings of Los Disparates.

Quinta del Sordo and Black Paintings (1819–1822)[edit]

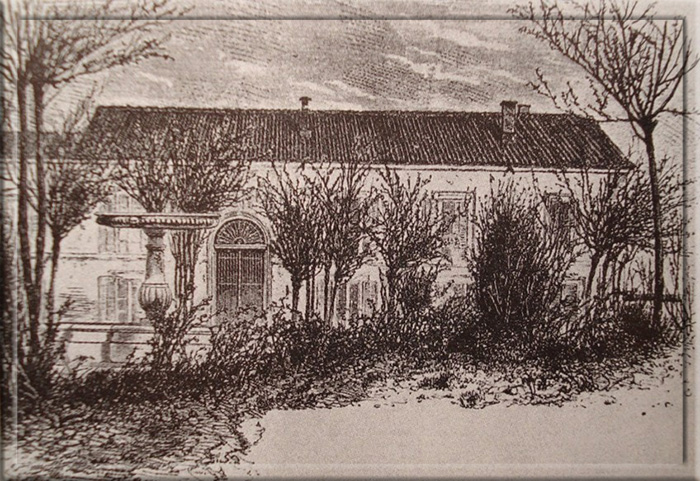

Records of Goya’s later life are relatively scant, and ever politically aware, he suppressed a number of his works from this period, working instead in private.[49] He was tormented by a dread of old age and fear of madness.[50] Goya had been a successful and royally placed artist, but withdrew from public life during his final years. From the late 1810s he lived in near-solitude outside Madrid in a farmhouse converted into a studio. The house had become known as «La Quinta del Sordo» (The House of the Deaf Man), after the nearest farmhouse that had coincidentally also belonged to a deaf man.[51]

Art historians assume Goya felt alienated from the social and political trends that followed the 1814 restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, and that he viewed these developments as reactionary means of social control. In his unpublished art he seems to have railed against what he saw as a tactical retreat into Medievalism.[52] It is thought that he had hoped for political and religious reform, but like many liberals became disillusioned when the restored Bourbon monarchy and Catholic hierarchy rejected the Spanish Constitution of 1812.[53]

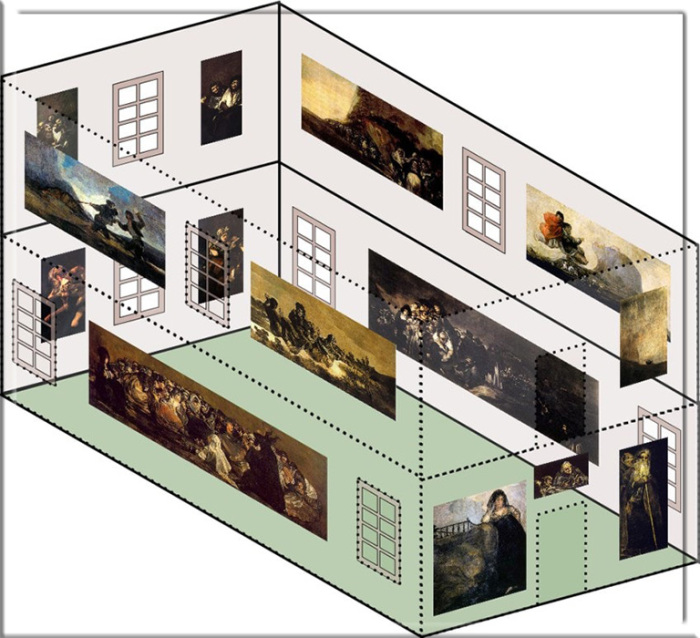

At the age of 75, alone and in mental and physical despair, he completed the work of his 14 Black Paintings,[C] all of which were executed in oil directly onto the plaster walls of his house. Goya did not intend for the paintings to be exhibited, did not write of them,[D] and likely never spoke of them.[54] Around 1874, 50 years after his death, they were taken down and transferred to a canvas support by owner Baron Frédéric Émile d’Erlanger. Many of the works were significantly altered during the restoration, and in the words of Arthur Lubow what remain are «at best a crude facsimile of what Goya painted.»[55] The effects of time on the murals, coupled with the inevitable damage caused by the delicate operation of mounting the crumbling plaster on canvas, meant that most of the murals suffered extensive damage and loss of paint. Today, they are on permanent display at the Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Bordeaux (October 1824 – 1828)[edit]

Leocadia Weiss (née Zorrilla, 1790–1856),[57][58] the artist’s maid, younger by 35 years, and a distant relative,[59] lived with and cared for Goya after Bayeu’s death. She stayed with him in his Quinta del Sordo villa until 1824 with her daughter Rosario.[60] Leocadia was probably similar in features to Goya’s first wife Josefa Bayeu, to the point that one of his well-known portraits bears the cautious title of Josefa Bayeu (or Leocadia Weiss).[61]

Not much is known about her beyond her fiery temperament. She was likely related to the Goicoechea family, a wealthy dynasty into which the artist’s son, Javier, had married. It is known that Leocadia had an unhappy marriage with a jeweler, Isidore Weiss, but was separated from him since 1811, after he had accused her of «illicit conduct». She had two children before that time, and bore a third, Rosario, in 1814 when she was 26. Isidore was not the father, and it has often been speculated—although with little firm evidence—that the child belonged to Goya.[62] There has been much speculation that Goya and Weiss were romantically linked; however, it is more likely the affection between them was sentimental.[63]

Goya died on 16 April 1828.[64] Leocadia was left nothing in Goya’s will; mistresses were often omitted in such circumstances, but it is also likely that he did not want to dwell on his mortality by thinking about or revising his will. She wrote to a number of Goya’s friends to complain of her exclusion but many of her friends were Goya’s also and by then were old men or had died, and did not reply. Largely destitute, she moved into rented accommodation, later passing on her copy of the Caprichos for free.[65]

Films and television[edit]

- Goya: Crazy Like a Genius (2002), a documentary by Ian MacMillan, presented by Robert Hughes

- Goya’s Ghosts (2006), directed by Miloš Forman

- Volavérunt (1999), directed by Bigas Luna and based on the novel by Antonio Larreta

- Goya in Bordeaux (1999), Spanish historical drama film written and directed by Carlos Saura about the life of Francisco de Goya

- Goya or the Hard Way to Enlightenment (1971) (German: Goya – oder der arge Weg der Erkenntnis) is a 1971 East German drama film directed by Konrad Wolf. It was entered into the 7th Moscow International Film Festival where it won a Special Prize. It is based on a novel with the same title by Lion Feuchtwanger.

- The Naked Maja (1958), directed by Henry Koster. A film about the painter Francisco Goya and the Duchess of Alba; Anthony Franciosa played Goya and Ava Gardner played The Duchess.

- Tiempo de ilustrados (Time of the Enlightened) in the series The Ministry of Time. Goya (played by Pedro Casablanc) must repaint La maja desnuda after a cult called the Exterminating Angels destroy it.

Goya’s influence on modern and contemporary artists and writers[edit]

- In the early 20th century, Spanish masters Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí drew influence from Los caprichos and the Black Paintings of Goya.[66]

- In the 21st century, American postmodern painters such as Michael Zansky and Bradley Rubenstein draw inspiration from «The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters» (1796–98) and Goya’s Black Paintings. Zanksy’s «Giants and Dwarf Series» (1990–2002) of large-scale paintings and wood carvings use imagery from Goya.[67][68]

- Spanish author Fernando Arrabal’s novel The Burial of the Sardine was inspired by Goya’s painting.[69]

- Russian poet Andrei Voznesensky’s I Am Goya was inspired by Goya’s anti-war paintings.[70]

- The video game Impasto was based on the works of Goya.[71]

References[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Théophile Gautier described the figures as looking like «the corner baker and his wife after they won the lottery».[25]

- ^ «Even if one takes into consideration the fact that Spanish portraiture is often realistic to the point of eccentricity, Goya’s portrait still remains unique in its drastic description of human bankruptcy». Licht (1979), 68

- ^ A contemporary inventory compiled by Goya’s friend, the painter Antonio de Brugada, records 15. See Lubow, 2003

- ^ As he had with the «Caprichos» and «The Disasters of War» series. Licht (1979), 159

Citations[edit]

- ^ Voorhies, James (October 2003). «Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) and the Spanish Enlightenment». www.metmuseum.org. HEILBRUNN TIMELINE OF ART HISTORY ESSAYS. Department of European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Harris-Frankfort, Enriqueta (12 April 2021). «Francisco Goya – The Napoleonic invasion and period after the restoration». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ «The Frick Collection: Exhibitions». www.frick.org. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Carlos, Fuentes (1992). The Buried Mirror: Reflections on Spain and the New World. London. Andre Deutsch Ltd. p. 230. ISBN 978-02339-79953.

- ^ a b Hughes (2004), 32

- ^ «ZERAINGO OSPETSUAK : Francisco de Goya». Zerain.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ a b Connell (2004), 6–7

- ^ Hughes (2004), 27

- ^ Hughes (2004), 33

- ^ «Cartas de Goya a Martín Zapater. Museo del Prado. Retrieved 13 December 2015

- ^ Connell (2004), 14

- ^ Hagen & Hagen, 317

- ^ Hughes (2004), 34

- ^ Hughes (2004), 37

- ^ Eitner (1997), 58

- ^ Baticle (1994), 74

- ^ Symmons (2004), 66

- ^ Hagen & Hagen, 7

- ^ Hughes (2004), 95

- ^ Hagen; Hagen (1999), 7

- ^ «print study | British Museum». The British Museum. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Hughes (2004), 96

- ^ Hughes (2004), 130

- ^ Hughes (2004), 83

- ^ Chocano, Carina. «Goya’s Ghosts». Los Angeles Times, 20 July 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ^ Tomlinson (2003), 147

- ^ Tomlinson (1991), 59

- ^ Licht (1979), 83

- ^ «The Nude Maja, the Prado». Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ The unflinching eye.. The Guardian, October 2003.

- ^ Museo del Prado, Catálogo de las pinturas. Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Madrid, 1996. 138. ISBN 84-87317-53-7

- ^ The Sleep of Reason Archived 22 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine Linda Simon (www.worldandi.com). Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ^ Crow, Thomas (2007). «3: Tensions of the Enlightenment, Goya». In Stephen Eisenman (ed.). Nineteenth Century Art.: A Critical History (PDF) (3rd ed.). New York: Thames and Hudson. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Licht (1979), 156

- ^ Schulz, Andrew. «The Expressive Body in Goya’s Saint Francis Borgia at the Deathbed of an Impenitent». The Art Bulletin, 80.4 1998.

- ^ It is not known why Goya became sick, the many theories range from polio or syphilis, to lead poisoning. Yet he survived until eighty-two years.

- ^ Hughes, Robert. «The unflinching eye». The Guardian, 4 October 2003. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- ^ Hustvedt, Siri (10 August 2006). Mysteries of the Rectangle: Essays on Painting. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-56898-618-0.

- ^ Mary Mathews Gedo (1985). Psychoanalytic Perspectives on Art: PPA. Analytic Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-88163-030-5.

- ^ Historical Clinicopathological Conference (2017) Archived 11 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine University of Maryland School of Medicine, Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ James G. Hollandsworth (31 January 1990). The Physiology of Psychological Disorders: Schizophrenia, Depression, Anxiety and Substance Abuse. Springer. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-306-43353-5.

- ^ Connell (2004), 78–79

- ^ Petra ten-Doesschate Chu; Laurinda S. Dixon (2008). Twenty-first-century Perspectives on Nineteenth-century Art: Essays in Honor of Gabriel P. Weisberg. Associated University Presse. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-87413-011-9.

- ^ Williams, Paul (3 February 2011). The Psychoanalytic Therapy of Severe Disturbance. Karnac Books. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-78049-298-8.

- ^ Wilson-Bareau, 45

- ^ Jones, Jonathan. «Look what we did». The Guardian, 31 March 2003. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ Connell (2004), 175

- ^ Fremont-Barnes, Gregory. «The Napoleonic wars: the Peninsular War 1807–1814». Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002. 73. ISBN 1-84176-370-5

- ^ Connell, 175

- ^ The cause of Goya’s illness is unknown; theories range from polio to syphilis to lead poisoning. See Connell, 78–79

- ^ Connell, 204; Hughes, 372

- ^ Larson, Kay. «Dark Knight». New York Magazine, Volume 22, No. 20, 15 May 1989. 111.

- ^ Stoichita; Coderch, 25–30

- ^ Licht (1979), 159

- ^ Lubow, Arthur. «The Secret of the Black Paintings». The New York Times, 27 July 2003. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ Hughes (2004), 402

- ^ Junquera, 13

- ^ Stevenson, Ian (2003). European Cases of the Reincarnation Type (2015 ed.). McFarland & Co. pp. 243–244. ISBN 9781476601151.

- ^ Gassier, 103

- ^ Buchholz, 79

- ^ Connell (2004), 28

- ^ Hughes (2004), 372

- ^ Junquera, 68

- ^ Chilvers, Ian (January 2004). «Goya, Francisco de». The Oxford Dictionary of Art (2014 online ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860476-1. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Connell (2004), 235

- ^ «Francisco Goya Paintings, Bio, Ideas». The Art Story. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Kuspit, Donald (2014). Michael Zansky: Bosch for Today. Milano: Charta. pp. 7–19. ISBN 978-1-938922503.

- ^ Kuspit, Donald. «Donald Kuspit on Michael Zansky’s Van Gogh Portraits». White Hot Magazine of Contemporary Art.

- ^ Guicharnaud, Jacques (1962). «Forbidden Games: Arrabal». Yale French Studies (29): 116–119. doi:10.2307/2929043. JSTOR 2929043. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Raymond H (1 June 2010). «Andrei Voznesensky, Russian Poet, Dies at 77». The New York Times. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ «Impasto on Steam».

Further reading[edit]

- Baticle, Jeannine. Goya: Painter of Terrible Splendor, «Abrams Discoveries» series. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994

- Buchholz, Elke Linda. Francisco de Goya. Cologne: Könemann, 1999. ISBN 3-8290-2930-6

- Ciofalo, John J. The Self-Portraits of Francisco Goya. Cambridge University Press, 2002

- Connell, Evan S. Francisco Goya: A Life. New York: Counterpoint, 2004. ISBN 978-1-58243-307-3

- Eitner, Lorenz. An Outline of 19th Century European Painting. New York: Harper & Row, 1997. ISBN 978-0-0643-2977-4

- Gassier, Pierre. Goya: A Biographical and Critical Study. New York: Skira, 1955

- Gassier, Piere and Juliet Wilson. The Life and Complete Work of Francisco Goya. New York 1971.

- Glendinning, Nigel. Goya and his Critics. New Haven 1977.

- Glendinning, Nigel. «The Strange Translation of Goya’s Black Paintings». The Burlington Magazine, Volume 117, No. 868, 1975

- Hagen, Rose-Marie & Hagen, Rainer. Francisco Goya, 1746–1828. London: Taschen, 1999. ISBN 978-3-8228-1823-7

- Havard, Robert. «Goya’s House Revisited: Why a Deaf Man Painted his Walls Black». Bulletin of Spanish Studies, Volume 82, Issue 5 July 2005

- Hennigfeld, Ursula (ed.). Goya im Dialog der Medien, Kulturen und Disziplinen. Freiburg: Rombach, 2013. ISBN 978-3-7930-9737-2

- Hilt, Douglas. «Goya: Turmoils of a Patriot» History Today (Aug 1973), Vol. 23 Issue 8, pp 536–545, online

- Hughes, Robert. Goya. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004. ISBN 978-0-394-58028-9

- Junquera, Juan José. The Black Paintings of Goya. London: Scala Publishers, 2008. ISBN 1-85759-273-5

- Kravchenko, Anastasiia. Mythological subjects in Francisco Goya’s work. 2019

- Licht, Fred S. Goya in Perspective. New York 1973.

- Licht, Fred. Goya: The Origins of the Modern Temper in Art. Universe Books, 1979. ISBN 0-87663-294-0

- Litroy, Jo. Jusqu’à la mort. Paris: Editions du Masque, 2013. ISBN 978-2702440193

- Symmons, Sarah. Goya: A Life in Letters. Pimlico, 2004. ISBN 978-0-7126-0679-0

- Tomlinson, Janis. Francisco Goya y Lucientes 1746–1828. London: Phaidon, 1994. ISBN 978-0-7148-3844-1

- Tomlinson, Janis. «Burn It, Hide It, Flaunt It: Goya’s Majas and the Censorial Mind». The Art Journal, Volume 50, No. 4, 1991

External links[edit]

- Francisco Goya’s Cats

- www.FranciscoGoya.com

- Goya in Aragon Foundation: Online catalogue

- Goya, the Secret of the Shadows, a documentary film by David Mauas, Spain, 2011, 77′

- Goya: The Most Spanish of Artists, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Caprichos (PDF). (10.0 MB) (PDF in the Arno Schmidt Reference Library)

- Desastres de la guerra (PDF). (10.6 MB) (PDF in the Arno Schmidt Reference Library)

- Etching series by Goya

- «His Majesty’s Giant Anteater – A New Goya is Discovered!»

- Bibliothèque numérique de l’INHA – Estampes de Francisco de Goya

- Goya in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF)

- Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains a significant amount of material on the prints of Goya

- Francisco Goya Prints in the Claremont Colleges Digital Library

- Francisco Goya Work[permanent dead link] at the Muscarelle Museum of Art

- Goya hidden micro-signatures, a revolutionary discovery

Educalingo cookies are used to personalize ads and get web traffic statistics. We also share information about the use of the site with our social media, advertising and analytics partners.

Download the app

educalingo

I remember when you used to have your profession on your passport and I always thought that being a painter was the best one to be, because my heroes were Goya and Francis Bacon.

Damien Hirst

PRONUNCIATION OF GOYA

GRAMMATICAL CATEGORY OF GOYA

Goya is a noun.

A noun is a type of word the meaning of which determines reality. Nouns provide the names for all things: people, objects, sensations, feelings, etc.

WHAT DOES GOYA MEAN IN ENGLISH?

Francisco Goya

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes was a Spanish romantic painter and printmaker regarded both as the last of the Old Masters and the first of the moderns. Goya was court painter to the Spanish Crown; throughout the Peninsular War he remained in Madrid, where he painted the portrait of Joseph Bonaparte, pretender to the Spanish throne, and documented the war in the masterpiece of studied ambiguity known as the Desastres de la Guerra. Through his works he was both a commentator on and chronicler of his era. The subversive imaginative element in his art, as well as his bold handling of paint, provided a model for the work of artists of later generations, notably Manet, Picasso and Francis Bacon.

Definition of Goya in the English dictionary

The definition of Goya in the dictionary is Francisco de, full name Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes. 1746–1828, Spanish painter and etcher; well known for his portraits, he became court painter to Charles IV of Spain. He recorded the French invasion of Spain in a series of etchings The Disasters of War and two paintings 2 May 1808 and 3 May 1808.

WORDS THAT RHYME WITH GOYA

Synonyms and antonyms of Goya in the English dictionary of synonyms

Translation of «Goya» into 25 languages

TRANSLATION OF GOYA

Find out the translation of Goya to 25 languages with our English multilingual translator.

The translations of Goya from English to other languages presented in this section have been obtained through automatic statistical translation; where the essential translation unit is the word «Goya» in English.

Translator English — Chinese

戈雅

1,325 millions of speakers

Translator English — Spanish

Goya

570 millions of speakers

English

Goya

510 millions of speakers

Translator English — Hindi

गोया

380 millions of speakers

Translator English — Arabic

غويا

280 millions of speakers

Translator English — Russian

Гойя

278 millions of speakers

Translator English — Portuguese

Goya

270 millions of speakers

Translator English — Bengali

Goya এক

260 millions of speakers

Translator English — French

Goya

220 millions of speakers

Translator English — Malay

Goya

190 millions of speakers

Translator English — German

Goya

180 millions of speakers

Translator English — Japanese

ゴヤ

130 millions of speakers

Translator English — Korean

고야

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Javanese

Goya

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Vietnamese

Goya

80 millions of speakers

Translator English — Tamil

கோயா

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Marathi

गोया

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Turkish

Goya

70 millions of speakers

Translator English — Italian

Goya

65 millions of speakers

Translator English — Polish

Goya

50 millions of speakers

Translator English — Ukrainian

Гойя

40 millions of speakers

Translator English — Romanian

Goya

30 millions of speakers

Translator English — Greek

Goya

15 millions of speakers

Translator English — Afrikaans

Goya

14 millions of speakers

Translator English — Swedish

Goya

10 millions of speakers

Translator English — Norwegian

Goya

5 millions of speakers

Trends of use of Goya

TENDENCIES OF USE OF THE TERM «GOYA»

The term «Goya» is very widely used and occupies the 19.286 position in our list of most widely used terms in the English dictionary.

FREQUENCY

Very widely used

The map shown above gives the frequency of use of the term «Goya» in the different countries.

Principal search tendencies and common uses of Goya

List of principal searches undertaken by users to access our English online dictionary and most widely used expressions with the word «Goya».

FREQUENCY OF USE OF THE TERM «GOYA» OVER TIME

The graph expresses the annual evolution of the frequency of use of the word «Goya» during the past 500 years. Its implementation is based on analysing how often the term «Goya» appears in digitalised printed sources in English between the year 1500 and the present day.

Examples of use in the English literature, quotes and news about Goya

3 QUOTES WITH «GOYA»

Famous quotes and sentences with the word Goya.

I remember when you used to have your profession on your passport and I always thought that being a painter was the best one to be, because my heroes were Goya and Francis Bacon.

It was my 16th birthday — my mom and dad gave me my Goya classical guitar that day. I sat down, wrote this song, and I just knew that that was the only thing I could ever really do — write songs and sing them to people.

When I was in high school, I was lucky enough to be an exchange student to a small town in Argentina called Goya.

10 ENGLISH BOOKS RELATING TO «GOYA»

Discover the use of Goya in the following bibliographical selection. Books relating to Goya and brief extracts from same to provide context of its use in English literature.

This is one genius writing at full capacity about another—and the result is truly spectacular. From the Hardcover edition.

2

Goya: The Last Carnival

This intriguing book on Goya concentrates on the closing years of the eighteenth century as a neglected milestone in his life.

Victor I. Stoichita, Anna Maria Coderch, 2000

Richly illustrated and filled with new information, this updated version of the great Spanish artist uses nearly 300 full color illustrations to retrace GoyaÆs life and career, organizing his life into the various genres and mediums in …

4

Francisco Goya, 1746-1828

This Spanish-language book samples every major style by this master.

Rose-Marie Hagen, Francisco de Goya, Rainer Hagen, 2003

5

Los Caprichos … With a new introduction by Philip Hofer

Reproductions of eighty aquatint plates depicting absurd monsters reflect the artist’s views of social vices existing in Spain around the year 1800

This paperback edition of the award-winning study of the life and work of Goya is filled with the same fine reproductions as the original 1994 hardcover.

7

The black paintings of Goya

Goya was the last of the old masters and the first of the moderns. The Black Paintings presage surrealism and other aspects of the 20th century artistic vision. The series forms a star part of the Prado’s collections.

Like Velázquez, he concentrated on faces, but he drew his heads cunningly, and constructed them out of tones of transparent greys. Monstrous forms inhabit his black-and-white world: these are his most profoundly deliberated productions.

Probes the mind of the Spanish painter, reconstructing the violent, repressive Spain he called home and charting his powerful influence on Western art.

Splendid reproductions of works by one of the world’s greatest portraitists, among them The Parasol, The Duchess of Alba, The Third of May, and The Maja Clothed, 12 more.

10 NEWS ITEMS WHICH INCLUDE THE TERM «GOYA»

Find out what the national and international press are talking about and how the term Goya is used in the context of the following news items.

CLIFFORD ROSS with Phong Bui

In 1979 I saw Goya’s great painting The Colossus at the Prado and it just pulled me out of Clem’s ghetto. It was like being hit with a lightning … «Brooklyn Rail, Jul 15»

Duo plan courier service in downtown Salinas

Follow MacGregor «Goya» Eddy on Twitter at @Goya1949. Contact her by email at wecouldcarless@gmail.com or mail to: We Could Car Less, … «The Salinas Californian, Jul 15»

How Alebrijes Were Invented As Mexican Folk Craft

… creatures with horns, antlers, wings (at times, more than one pair); the ones that look like they could belong to both Disney and Goya? «BLOUIN ARTINFO, Jul 15»

Cruise port spotlight: Dublin, Ireland

… extensive collection of Irish and European art with such masters as Monet, Goya, Velazquez and Caravaggio among the many represented. «Orlando Sentinel, Jul 15»

Producer Of Fake Olive Oil Nabbed In Anambra

“The suspect specialised in the adulteration of GOYA Olive Oil, which was discovered after investigation to be the edible vegetable oil … «The Tide, Jul 15»

Eduard Fernandez, Jose Coronado Set For Alberto Rodriguez’s ‘Mil …

A jury prize and best actor (Gutierrez) at last September’s San Sebastian, “Marshland” swept this year’s Goya Awards, was a Spanish box office … «Variety, Jul 15»

Goya painted Florentino Pérez eating Iker Casillas. Let us explain.

Editor’s note: Spanish painter Francisco Goya (totally dead) has exhibited a new work (not really) depicting the tragic end to Iker Casillas and … «Fusion, Jul 15»

Centene Sponsors 2015 National Council Of La Raza Conference …

A «Path to Health and Wellness»: Presentations, massage stations, educational materials, healthy cooking demonstrations with Goya Foods, … «Virtual Press Office, Jul 15»

Lost in the hubbub: London galleries patronise us with this PR-led …

… the erotica of Egon Schiele, and Goya’s drawings – hardly dry subjects, but looked at with real intelligence and above all excellent loans. «The Guardian, Jul 15»

‘American Enterprise’

Goya Guanabana | Goya Foods started in the U.S. in 1936 to supply local bodegas. It was among the companies that began seriously … «Wall Street Journal, Jul 15»

REFERENCE

« EDUCALINGO. Goya [online]. Available <https://educalingo.com/en/dic-en/goya>. Apr 2023 ».

Download the educalingo app

Discover all that is hidden in the words on

Свои легендарные «Чёрные картины» испанский художник Франсиско Гойя рисовал как фрески на своей вилле «Кинта дель Сордо» в течение четырёх лет. Это весьма необычные настенные росписи, они тёмные и временами несколько пугающие, что мурашки начинают бегать по телу. Гойя является художником преимущественно романтического стиля. Почему же он создал такие мрачные картины и какой тайный смысл в них вложил — далее в обзоре.

Кем был Франсиско Гойя?

Франсиско Хосе де Гойя-и-Лусьентес жил на рубеже 18 и 19 веков. Он появился на свет в Испании, там же получил образование и жил. Женился живописец на сестре одного из своих учителей. Мастер был художником для королевского двора и представителей испанской знати. Когда между Францией и Испанией началась война — это оказало огромное влияние на Гойю. Он написал тогда свои знаменитые полотна «Второе мая 1808 года» (1814 г.) и «Третье мая 1808 г.» (1814 г.) и другие менее известные. После Гойя стал стремительно терять слух и из-за этого стал более замкнутым.

Автопортрет Франсиско де Гойи, около 1800 года.

Художественный стиль Гойи специалисты описывают как романтический. Он исследовал темы, уходящие корнями в социально-политические проблемы общества. Некоторые из его работ также считались довольно мрачными по своей природе, но, тем не менее, Гойя был родоначальником современного искусства из-за его более выразительного художественного стиля. В мире искусства его неоднократно называют «последним из старых мастеров и первым из современных».

Вверху: «Второе мая 1808 года или Атака мамелюков» (1814 г.). Внизу: «Третье мая 1808 года» (1814 г.), Франсиско де Гойя.

ЧИТАТЬ ТАКЖЕ: Как художник Франсиско Гойя перевернул мир искусства: «Первый из современных»

«Чёрные картины»

Чёрные картины, которые Франсиско Гойя написал в период с 1819 по 1823 год стали самыми мрачными творениями этого художника. Началось всё с того, что он приобрёл новый особняк, загородную виллу под названием Quinta del Sordo, что примерно переводится с испанского как «Дом глухого человека». В то время Гойе было около 73 лет, и он страдал глухотой из-за болезни. Дом был назван не в его честь, а в честь предыдущего владельца, который также был глухим. Именно здесь живописец и создал свой знаменитый тёмный цикл.

Гравюра виллы Кинта дель Сордо, где Гойя создавал свои «Чёрные картины», Чарльз Ириарте, 1867 год.

На стенах дома Гойя нарисовал 14 композиций. Некоторые из них находились на первом этаже, а другие — на втором. Однако есть учёные, которые отмечают, что могла быть 15-я картина под названием «Головы в пейзаже» (ок. 1820–1823). Сегодня это полотно является частью коллекции Стэнли Мосса. Специалисты предполагают, что Гойя никогда не намеревался показывать эти картины остальному миру. Их никто ему не заказывал. Он нарисовал их сам и только для себя.

Загадочная история чёрных картин Гойи

Однако существует ещё одна теория о «Чёрных картинах» Гойи, которая вызвала некоторые спекуляции в мире искусства. Некоторые учёные считают, что Гойя не был автором этих полотен. Они выдвигали различные версии, по одной из которых автором может быть сын художника. Основанием для этой теории послужило то, что картины были на двух этажах виллы. Тут следует отметить, что когда на вилле жил Гойя — там был всего один этаж. Второй появился после его смерти.

Другие специалисты говорят, что во всём виноваты неточности в документах. Вилла была уже двухэтажной. К единому мнению в этом вопросе историки так и не пришли.

Предполагаемое расположение Чёрных картин в Кинта-дель-Сордо.

Фотография Кинта дель Сордо, около 1900 года.

Значение чёрных картин Гойи

Чёрные картины Франсиско Гойи были названы таким образом не только потому что они визуально очень тёмные. Они действительно преимущественно окрашены в чёрный, коричневый и серый цвета с небольшими вкраплениями дополнительных оттенков, таких как белый, красный и синий. В целом же они выглядят мрачно, но своё название получили из-за своих тёмных психологических аспектов. Гойя затронул в своих полотнах невероятно широкий спектр тем. От личностных человеческих эмоций, мифологических историй и колдовства, религии, до таких глобальных тем, как смерть, зло, старение. От этих картин так и веет тоской, одиночеством, бесконечным унынием. Даже улыбки персонажей не вызывают у зрителя ничего кроме жутких мурашек.

Есть множество вопросов о том, почему Гойя создал эти мрачные картины. Особенно если сравнивать их с его предыдущими работами, которые, очевидно, представляют собой два разных художественных стиля. Некоторые учёные предполагают, что это произошло из-за ухудшения его собственных умственных способностей, травмы, связанной с его болезнями, и мучительного опыта войн между Францией, а также внутренних конфликтов в Испании.

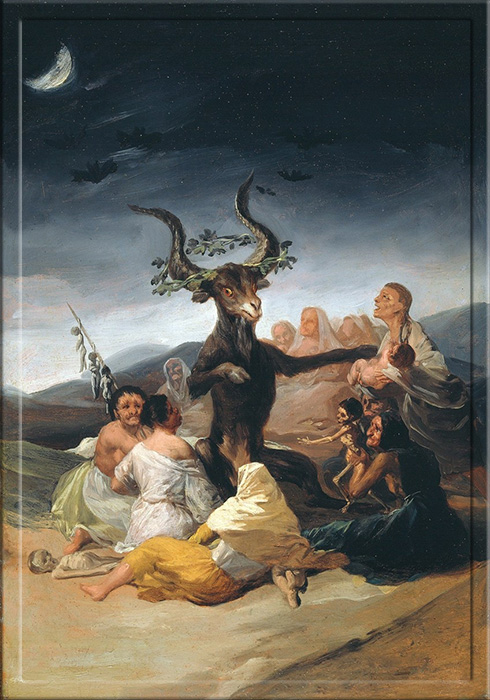

Шабаш ведьм (1797-1798) Франсиско де Гойи.

ЧИТАТЬ ТАКЖЕ: Мистическая история любви капризной герцогини Альбы и гениального художника Франсиско Гойя

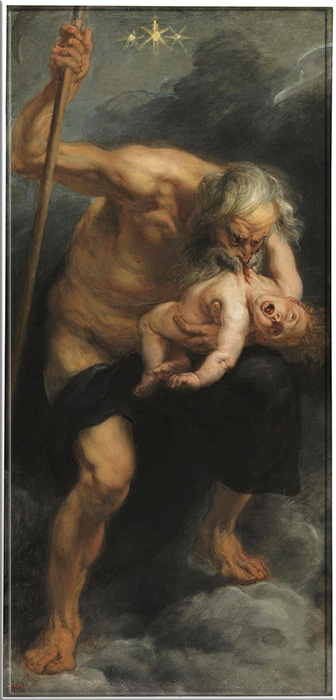

«Сатурн, пожирающий своего сына»

«Сатурн, пожирающий своего сына» — это изображение римского бога, известного как Сатурн, который в прямом смысле этого слова пожирает своего ребёнка. Тут следует напомнить предысторию этого божества. Сначала это был греческий титан, носящий имя Кронос. Согласно пророчеству, его должен был свергнуть один из его детей, и в результате он решил съесть их всех, чтобы избежать своей участи.

«Сатурн, пожирающий своего сына».

Гойя изобразил Сатурна большой, ужасно костлявой фигурой. Кажется, он сидит на одном колене, а его левое колено упирается в землю. Обеими руками он сжимает мёртвое тело одного из своих детей. Очевидно, что он крепко держит его, так как между его пальцами кровь, а костяшки пальцев выпирают. Тело безжизненно в хватке Сатурна, более того, оно безголовое и без правой руки, что позволяет предположить, что он уже поглотил эти части тела. Его левая рука вытянута и почти во рту Сатурна, кажется, что она уже откушена. Видно, что это довольно большой ребёнок, не младенец.

Рот бога жадно разинут, он готовится отгрызть следующую часть тела, а его глаза выпучены и дико смотрят на него. Точно так же его седые волосы, струящиеся чуть ниже плеч, также придают ему дикий вид. Неясно, где сидит или сгорбился Сатурн, поскольку окружающая среда кажется тёмной. Он мог быть на земле, несомненно, где-то спрятанным и грязным. Кроме того, многие источники также описывают «восставшийй» фаллос между ног бога, когда он пожирает своего ребёнка, что усиливает эмоциональную напряжённость и грубость изображения.

Сатурн, пожирающий сына (1636-1638) Питера Пауля Рубенса. Некоторые учёные считают, что эта картина повлияла на Гойю и вдохновила его на создание собственного полотна на эту тему.

Этот образ очень тёмный и поразительно мрачный в своём изображении. Он затрагивает первобытные и звероподобные аспекты и, если идти дальше, возможно, саму человеческую природу. Было ли это у художника метафорой пожирающей природы жизни во всех её проявлениях и смерти во всей её крови? Возможно, в психике его к этому времени произошли некие необратимые изменения. Некоторые эксперты предполагают, что посылом этого полотна было послание о том, что сам Гойя погрузился во тьму. Возможно, на это повлияло то, что незадолго до этого у его жены был выкидыш с травматическими последствиями. Кроме этого, из восьми детей пары до взрослого возраста дожил лишь один.

Кроме того, Гойя мог также изобразить его как символ войны, в качестве некого сардонического комментария к недавней войне Испании с Францией. Такая игра на идеях времени и смертности. Тёмные тона, неизвестный источник света на картине, придают ей ещё большее ощущение общей гнетучести. Гойя, казалось, рисовал выразительно, рыхлыми мазками, часто нанесёнными толстым слоем, называемым импасто. Если внимательно посмотреть, то можно заметить физическую текстуру краски, сделанную из мазков. Они также видны как очертания контуров тел. Особенно это заметно на широко распахнутых и дико выпученных глазах Сатурна.

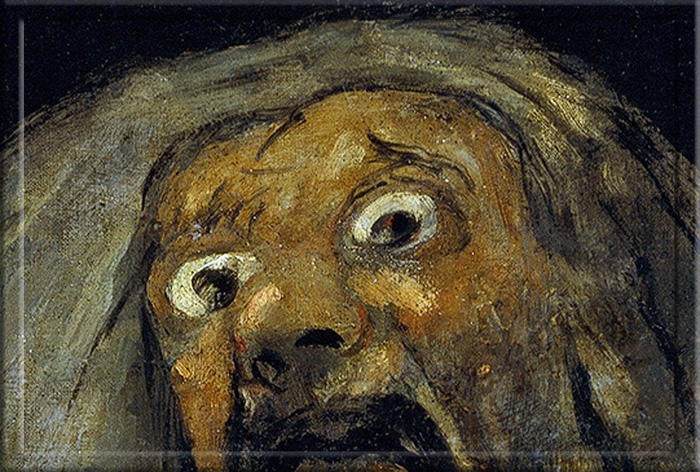

Фрагмент картины Франсиско де Гойи «Сатурн, пожирающий своего сына».

Сатурн изображён почти как гротескно-анималистический человек, а его форма несколько органична и образна. Другими словами, зритель понимает, что видит, когда рассматривает его, поскольку он не полностью абстрагирован до неузнаваемости. Гигантский рост Сатурна заполняет пространство с правой стороны композиции. Однако его фигура частично обрезана, и полностью её не видно. Возможно, это призвано создать драматический эффект, поскольку зритель поглощён этой фигурой, входящей в пространство и не полностью его заполняющей.

Сатурн, пожирающий своих сыновей, Франсиско де Гойя красным мелом на верже, около 1797 года.

Другие «Чёрные картины»

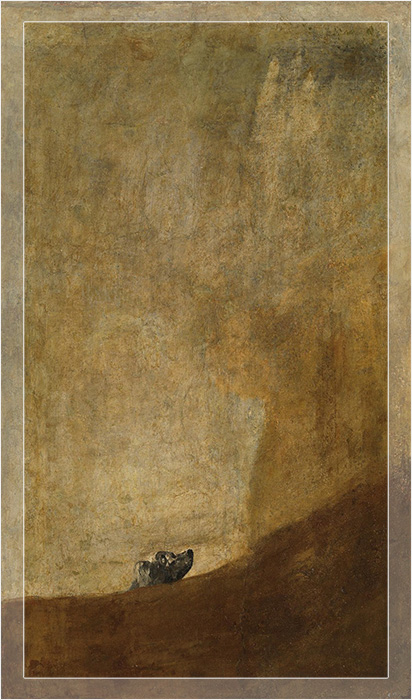

Интересно отметить, что во многих других работах из серии «Чёрных картин» предмет также позиционируется с разных точек зрения. Например, в «Собаке» большая пустая область в верхних двух третях картины являет собой отрицательное пространство, а собака, представляющая собой положительное пространство, находится в нижней трети и смотрит вверх на неизвестный источник. Точно так же в «Борьбе с дубинками» мы видим две дерущиеся фигуры. Они расположены немного левее композиции, оставляя с правой стороны открытое пространство, изображающее холм в отдалённом пейзаже.

«Собака» Франсиско де Гойи, 1820-1823 год.

«Борьба с дубинками» Франсиско де Гойи, 1820-1823 год.

Такое же расположение фигур в «Шествии Святой Канцелярии», где изображено шествие людей, выходящих на передний план композиции от заднего плана до правого нижнего угла. В «Фантастическом видении» и «Атропосе» Гойя снова поместил фокусы, представляющие собой группы фигур, парящих в воздухе, по обе стороны от композиции.

Вверху: «Фантастическое видение». Внизу: «Атропос». Франсиско де Гойя, 1819–1823 год.

Гойя оставляет зрителя в ужасе

Почти во всех 14 «чёрных картинах» Франсиско Гойи изображения людей, которые либо глубоко устрашающие, либо в созерцательном, либо в весёлом настроении. Гойя дал нам спектр эмоций, и независимо от того, изображал ли он миф или любой другой рассказ, он рисовал аспекты человеческой природы и, в конечном счете, то, что могло возникнуть из глубин человеческой психики. Тёмные картины Гойи — это кладезь смысла, и хорошо известно, что некоторые искусствоведы и учёные смогли расшифровать некоторые из этих картин, в то время как относительно других остались в неведении.

Картины, которые сохранились, хранятся в Музее Прадо. Они взяты с их первоначальных мест на стенах виллы Гойи, которую он покинул в 1824 году, чтобы переехать в Бордо во Франции. Спустя годы, после того как картины были сняты со стен Кинта-дель-Сордо в 1875 году, Испания приняла участие в ретроспективной художественной выставке 1878 года в Париже на Всемирной выставке, расположенной во дворце Трокадеро. В испанской секции можно было увидеть несколько «чёрных картин» Гойи.

Фотография Всемирной выставки 1878 года в Париже, показывающая испанский раздел, в том числе « Шабаш ведьм» Гойи.

Несмотря на то, что серия «Чёрные картины» была повреждена в результате её перемещения, люди смогли осмотреть интерьер дома Гойи. Что бы не хотел на самом деле сказать своими картинами художник, он, тем не менее, оказал неизгладимое впечатление на мир искусства, особенно повлияв на художественные движения, такие как экспрессионизм и сюрреализм.

Разные художники в разные времена создавали настолько удручающе мрачные картины, что наводили на зрителя страх. Прочтите в другой нашей статье о произведениях искусства с плохой репутацией: шедевры, которые не дадут уснуть.

Понравилась статья? Тогда поддержи нас, жми:

Definitions of Goya

-

noun

Spanish painter well known for his portraits and for his satires (1746-1828)

DISCLAIMER: These example sentences appear in various news sources and books to reflect the usage of the word ‘Goya’.

Views expressed in the examples do not represent the opinion of Vocabulary.com or its editors.

Send us feedback

EDITOR’S CHOICE

Look up Goya for the last time

Close your vocabulary gaps with personalized learning that focuses on teaching the

words you need to know.

Sign up now (it’s free!)

Whether you’re a teacher or a learner, Vocabulary.com can put you or your class on the path to systematic vocabulary improvement.

Get started

В этой статье представлена подборка самых известных картин Франсиско Гойи (1746 — 1828) — величайшего испанского художника эпохи романтизма. Собственно, не только «испанского», и не только

«романтизма»: Франсиско Гойя — один из самых влятельных художников мира всех времен, подаривший человечеству свои яркие, самобытные, пугающие и захватывающие одновременно шедевры, интерес публики

к которым со временем лишь возрастает. Итак, самые известные картины Франсиско Гойи!

Продавец посуды (1778 — 1779) — Франсиско Гойя. Это полотно входит в серию из 20 «картонов» для гобеленов, заказанных у Гойи Антоном

Рафаэлем Менгсом в октябре 1777 года. Они изображают сцены из современной жизни и предназначены для спальни (и ее прихожей) принца и принцессы Астурийских во дворце Эль Пардо.

Картина «Продавец посуды» поступила в музей Прадо в 1870 году из хранилища в Королевском дворце в Мадриде.

Гойя описал её в своем счете от 6 января 1779 года для Королевской гобеленовой мануфактуры следующим образом: «Валенсийский мужчина, продающий посуду; две сидящие дамы выбирают, что

купить; сидящая старуха делает то же самое; с одной стороны два джентльмена, сидящие на груде круглых циновок, наблюдают, как проезжает карета, в которой видна дама, с двумя лакеями и

кучером, управляющим лошадьми; дальше вдали видны различные люди и здания.»…читать полностью

Картина «Восстание 2 мая 1808 года в Мадриде» была написана Франсиско Гойей в 1814 году совместно с другим очень известным полотном «Третье мая 1808 года в Мадриде». В наши дни оба монументальных

произведения Гойи («2 мая» имеет размеры 268 х 347 см) экспонируются в музее Прадо в Мадриде, где собрана самая обширная коллекция рбаот испанского художника в мире.

В 1814 году Гойя обратился к кардиналу Луису де Бурбону, управлявшему Верховным советом Регенства, с предложением создать работы, посвященные событиям Войны за независимость (1808-1812), «чтобы

увековечить кистью наиболее заметные и героические действия или сцены нашего славного восстания против тирана Европы».

Под тираном Гойя имел в виду Наполенона Бонапарта, войска которого вторглись в Испанию в 1808 году и покинули Королевство лишь в 1814-ом…читать полностью

Франсиско Гойя получил заказ на «Маху обнажённую» от премьер-министра Испании Мануэля Годоя — и впоследствии пожалел о том, что взялся за его выполнение. Не стоит забывать: речь идет об Испании,

где Инквизиция, доживавшая последние годы, не желала, тем не менее, сдавать свои варварские позиции.

Картина была конфискована, а премьер-министр предстал перед судом, где вынужден был раскрыть имя художника. Гойе, таким образом, были предъявлены обвинения в безнравственности и создании «крайне

неприличных и представляющих серьезную угрозу общественным интересам произведений искусства».

Впрочем, совсем уж трагических последствий для Франсиско Гойи этот инцидент не имел: времена все-таки изменились, и художник, можно сказать, «отделался легким испугом». До сих пор не утихают

споры о том, кто именно позировал художнику для «Махи обнажённой». В 19-ом столетии наибольшей популярность пользовалсь версия о том, что на картине изображена Мария Каэтана де Сильва, 13-ая

герцогиня Альба, у которой, поговаривали, была любовная связь с харизматичным художником из Сарагоссы.

Никаких документальных свидетельств этой связи, впрочем, не имелось, а семья Альба всегда относилась к этой версии крайне негативно, вероятно, не считая Франсиско Гойю достойным роли любовника их

симпатичной прабабушки. Сегодня большинство искусствоведов считает, что на картине изображена не герцогиня Альба, а Пепита Тудо — одна из любовниц премьер-министра Годоя.

«Маха одетая», как несложно догадаться, была написана в пару к «Махе обнажённой» — о чем свидтельтствует как идентичность модели, так и абсолютно одинаковые размеры картин: 97 х 1805 см. Более

того, обе «Махи» были заказаны премьер-министром Испании Годоем для совместной демонстрации картин.

Годой подводил ничего не подозревающего гостя к «Махе одетой», давал ему полюбоваться шедевром Гойи, после «легким нажатием рука» приводил хитроумный механизм в действие — и перед изумленным

посетителем представала «Маха обнаженная»!

Чтобы понять, почему семейство Альба так рьяно отрицает тот факт, что позировала для картины Каэтана де Сильва, 13-ая герцогиня Альба, следует уточнить, кто такая «маха». «Маха» — это

представительница низших классов городского общества, известная своим дешевым щегольством, бурным нравом и особой приверженность к мелкому испанскому криминалитету.

Махи, по большому счету, являлись подругами испанских бандитов, любили дешевый шик (на дорогой попросту не было денег), обожали бурные страсти совершенно в испанском стиле и после очередной

разборки со своим уголовным другом прилюдно и на всю улицу угрожали перерезать ему горло — или покончить с собой, нередко воплощая в жизнь одно или другое.

Как мы понимаем, столь цыганский образ никоим образом не подходит семейству Альба, и потому, дабы развеять нелепые слухи о том, что для «Мах» Гойе позировала их далекая бабушка, в 1945 году семья

даже вскрыла гробницу Каэтаны де Сильва, дабы измерить кости проблемнной старушки и положить конец всяким нелепым домыслам.

Авантюра эта не увенчалась, однако, успехом. Наполеоновские солдаты, захватив Испанию в перод Полуостровных войн, уже, оказывается, вскрывали гробницу и нанесли немалый ущерб костям именитой

герцогини, так что измерить их не предствавлялось возможным.

В наши дни считается, что на картине «Маха одетая» (равно как и «Маха обнаженная») изображена самая «любимая любовница испанского премьер-министра — Пепита Тудо, которая, кстати, впоследствии

стала его женой. В настоящее время обе «Махи» демонстрируются рядом в музее Прадо в Мадриде.

«Сатурн, пожирающий своего сына» — один из самых жутких и запоминающихся образов в истории мирового искусства вообще. Следует признать, что в умении извлекать из глубин подсознания самые страшные

кошмары и с пугающей силой переносить их на холст с Гойей не мог сравниться никто.

Впрочем, в случае с «Сатурном» о холсте речь изначально не шла. Изначально эта была одна из четырнадцати фресок, написанных на стенах «Дома Глухого», который Гойя в 1819 году приобрел недалеко от

Мадрида. Интересно, что название дом получил из-за прежнего владельца, но после тяжкой болезни, перенесенной Франсиско Гойей в 1792 году, художник тоже оглох, так что название вполне сохранило

свою актуальность.

Все фрески, получившие название «Черных картин», отражают крайне мрачное состояние духа художника, удрученного как личными, так и политическими невзгодами. Гойя писал свои «Черные картины» для

себя, не предполагая, что их будут показывать публике. Тем не менее, к 1878 году их перевели на холст, чтобы показать на Всемирной выставке 1878 года.

Публика, увидевшие эти пронзительные, болезненные и крайне тяжелые для восприятия вещи, была скорее шокирована, чем довольна. Покупателей на «Черные картины» в то время не нашлось, и в 1881 году

они поступили в коллекцию Прадо.

Сам Гойя никаких названий «Черным картинам» не давал, и потому имена им присвоили уже после смерти художника. Считается, что на картине изображен Кронос, который, согласно легенде, опасался быть

свергнутым своим же ребенком и потому проглатывал всех своих детей. Хоть в древнегреческом мифе сказано, что он глотал детей в пеленках, Гоя решил изобразить Кроноса терзающим плоть напрямую,

дабы усилить воздействие на зрителя — и ему это, надо признать, удалось.

Людям с неустойчивой псхихикой, оказвшимся в Прадо (одном из величайших музеев мира) смотреть эту картину в оригинале не рекомендуется — настолько мощным и тяжелым воздействием на зрителя

(ощутимым буквально физически) она обладает.

«Третье мая 1808 года в Мадриде» — монументальное историческое полотно (375 х 266 см, холст, масло), написанное в 1814 году и в наши дни украшающее коллекцию Музея Прадо.

Картина запечатлела начало борьбы испанцев против французской оккупации. В конце марта 1808 Мадрид был оккупирован войсками Наполеона Бонапарта. Король Карл Четвертый был вынужден отречься от

престола в пользу своего сына Фердинанда Седьмого — однако Наполеона такой поворот событий устраивал не окончательно.

«Маленький корсиканец» наврал Карлу и Фердинанду с три короба, заманил их в Байону и взял под арест. Затем Наполеон решил выыезти из Испании также дочь и младшего сына отрекшегося короля — и как

раз это 2 мая 1808 года вызвало восстание в Мадриде, подавленное после нескольких часов уличных боев.

Интересно, что в восстании участвовали лишь горожане — регулярные испанские войска, согласно приказу, оставались в казармах и наблюдали, как французы уничтожают городское население. Единственным

исключением стали артиллеристы из казарм Монтелеона, которые сегодня считаются в Испании героями. Восстание закончилось поражением, сотни мадридцев были расстреляны — как раз этот трагический

момент и запечатлен на картине Гойи.

«Махи на балконе» (Las majas en el balcón — исп.) — картина маслом Франсиско Гойи, выполненная между 1808 и 1814 годами, когда Испания находилась в

состоянии конфликта с Францией в результате вторжения «непорядочной семейки» Наполеона с войсками.

Гойя, переживавший французскую оккупацию как личную трагедию, с 1810 года работал над серией гравюр «Бедствия войны», отнимавшей все душевные и физические силы художника, а в промежутках между

«серьезной» работой, желая чем-нибудь отвлечься, создавал более легкие вещи, многие из которых смело можно записать в истинные шедевры. Картина «Махи на балконе», известная в двух версиях — как

раз из их числа.

Оригиналом считается картина из коллекции Эдмона де Ротшильда в Швейцарии, в то время как версия, находящаяся ныне в Метрополитен-музее в Нью-Йорке является авторской копией. Слово «маха»

сделалось привычным русскоязычному уху именно благодаря замечательным картинам Гойи — хотя далеко не все смогут внятно объяснить, что же такое «маха»…читать полностью

Полет ведьм (холст, масло, 43,5 x 30,5 см) — картина Франсиско Гойи, написанная в 1798 году и входившая в серию из шести полотен, проданных герцогам

Осуны для украшения их загородного дома «Ла Аламеда» на окраине Мадрида. К сожалению, до наших дней сохранилась лишь одна из картин — «Полет ведьм», увидеть которую можно в музее Прадо в

Мадриде.

Сам Гойя называл эти работы «композициями по мотивам процессов над ведьмами». Несмотря на то, что пик «охоты на ведьм» пришелся на 17 век, во времена Гойи испанская инквизиция все еще имела

большую силу и власть, и смертные приговоры, выносимые высшим церковным трибуналом, по-прежнему приводились в исполнение, хотя уже и не с той пышностью и размахом, что веком ранее.

Три девицы с обнаженными торсами, всю одежду которых составляют спушенные на пояс санбенио (покаянные одеяния для еретиков) и колпаки в виде удлиненных, украшенных змейками епископских митр

(также часть одежды еретика на судилище), освещены ярким светом, источник которого находится за пределами картины…читать полностью

Не следует забывать, что Франиско Гойя, как и его великий предшественник и земляк Диего Веласкес, был придворным живописцем. Поэтому версия «Менин» Веласкеса в исполнении Гойи просто должна была

появиться на свет — и она появилась! Речь о «Портрете семьи Карла IV», написанном Гойей в 1800 — 1801 г.г.

О «Менинах» мы упомянули не случайно — как и на картине Веласкеса, на групповом портрете королевской семьи Гойя запечатлел себя. Однако, в отличие от «теплой дружественной атмосферы», царящей на

картине Веласкеса, «Портрет семьи Карла IV» являет собой, скорее, сборище деградантов, из которых единственным адекватным персонажем выглядит сам Франсиско Гойя, да и то лишь по той простой

причине, что не является членом королевской семьи.

Отметим, что сам Гойя имееет на картине слегка печальный, задумчивый и отстраненный вид, как будто говоря: «Извините, друзья, но задачей художника является изображение жизненной правде — так что

принимайте эту семейку такой, какая она есть: со всем их изъянами, тараканами и скелетами в королевском шкафу!»

Многогранный и весьма продуктивный гений Франсиско Гойи (1746 — 1828) особенно ярко проявился в портретном жанре. Среди художников найдется немного мастеров, которым удавалось бы так полно

выявить внутреннюю суть персонажа через его внешний облик.

По сути, Гойя не изображал своих заказчиков, среди которых, как мы знаем, были весьма влиятельные персоны, включая «помазанников божьх» — Гойя рассказывал их биографию живописными

средствами.

На портрете изображена Мария Рита Барренечеа-и-Моранте, в возрасте 18 лет вышедшая замуж в 1775 году за графа Карпио, получившего титул маркиза де ла Солана незадолго до кончины своей супруги в

1795 году. Примечательно, что Гойя написал этот портрет всего за несколько месяцев до смерти графини. Смертельно больная маркиза заказал Гойе этот портрет, чтобы ее единственная дочь могла

навсегда сохранить память о матери…читать полностью

«Сатурн, пожирающий своего сына» — не единственная из»Черных картин» Гойи, получивших всемирную известность. Еще одно чрезвычайно известное произведение этого жуткой серии — «Шабаш ведьм», также

известное под название «Большой Козел». В этой захватывающей сцене Сатана, изображенный Гойей в виде большого, почти черного силуэта антропоморфного козла, правит шабашем ведьм, которыми всегда

славилась Испания.

Как и другие сюжеты «Черных картин», мрачная демоническая тема «Шабаша ведьм» была, безусловно, навеяна резко ухудшающимся физическим и психологическим состоянием художника. Тем не менее, еще до

начала глубокого кризиса Гойя предпочитал мрачную палитру. «В искусстве цвет не нужен», — писал он. «Я вижу только свет и тень».

К сожалению, когда фреску «Шабаш Ведьм» («Большой Козел») срезали со стены «дома Глухого», чтобы перенести ее на холст, было утрачено около полутора метров работы. Тем не менее, имея без малого

пять метров в длину, эта картина остается одной из самых больших вещей Гойи — и, конечно же, одной из самых знаменитых.

И пусть публика на Всемирнной выставке 1878 и не оценила перенесенные на холст «Черные картины» — сегодня они считаются общепризнанными шедеврами, полюбоваться которыми… Нет-нет, здесь

«полюбоваться» явно не подходит»! Скажем так: испугаться которых можно в великом Музее Прадо в Мадриде.

На этом автопортрете (известном также, как «Погрудный автопортрет») Гойя намеренно представляет себя уязвимым и хрупким, раскрывая перед зрителем самые мягкие и добрые стороны своей

противоречивой души.

Темный фон, написанный быстрыми энергичными перекрещивающимися мазками, не сливается со схожим по тону цветом красно-коричневого сюртука, но напротив, придает ему дополнительное ощущение объема.

Эти цвета намеренно вступают в контраст с белоснежной рубашкой с открытым воротом, написанной значительно более тонким мазками. Техника в венецианском стиле подчеркивает мягкую,

розовую и несколько дряблую кожу Гойи на пороге старости. Тщательно продуманные тона подчеркивают сияние его лица, которому нужно очень мало света, чтобы выделиться на фоне почти «веласкесовской»

атмосферы, окружающей его…читать полностью