Praise Yahweh! Sing to Yahweh a new song, his praise in the assembly of the saints.

Alleluia cantate Domino canticum novum laus eius in ecclesia sanctorum.

But new wine must be put into fresh wineskins,

and both are preserved.

Sed vinum novum in utres novos mittendum est et utraque conservantur.

But new wine must be put into new bottles; and both are preserved.

Sed vinum novum in utres novos mittendum est et utraque conservantur.

For in Christ Jesus neither is circumcision anything, nor uncircumcision, but a new creation.

In Christo enim Iesu neque circumcisio aliquid valet neque praeputium sed nova creatura.

I want to start a new life.

Lorem ipsum dolor vitam novam agendam.

For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision availeth anything, nor uncircumcision, but a new creature.

In Christo enim Iesu neque circumcisio aliquid valet neque praeputium sed nova creatura.

They are new every morning; great is your faithfulness.

HETH novae diluculo multa est fides tua.

Now there arose a new king over Egypt, who didn’t know Joseph.

Surrexit interea rex novus super Aegyptum qui ignorabat Ioseph.

Now there arose up a new king over Egypt, which knew not Joseph.

Surrexit interea rex novus super Aegyptum qui ignorabat Ioseph.

They are new every morning: great is thy faithfulness.

HETH novae diluculo multa est fides tua.

It’s just I had to run away from all this and start a new life.

Suus ‘ iustus volo ut run ex his et initium novae vitae.

And ye shall eat old store,

and bring forth the old because of the new.

Comedetis vetustissima veterum et vetera novis supervenientibus proicietis.

You shall eat old store long kept,

and you shall move out the old because of the new.

Comedetis vetustissima veterum et vetera novis supervenientibus proicietis.

Ahijah laid hold of the new garment that was on him, and tore it in twelve pieces.

Adprehendensque Ahia pallium suum novum quo opertus erat scidit in duodecim partes.

And have put on the new man, who is being renewed in knowledge after the image of his Creator.

Et induentes novum eum qui renovatur in agnitionem secundum imaginem eius qui creavit eum.

Behold, the former things have happened, and I declare new things. I tell you about them before they come up.

Quae prima fuerant ecce venerunt nova quoque ego adnuntio antequam oriantur audita vobis faciam.

Again, I write a new commandment to you,

which is true in him and in you; because the darkness is passing away, and the true light already shines.

Iterum mandatum novum scribo vobis quod est verum

et in ipso et in vobis quoniam tenebrae transeunt et lumen verum iam lucet.

And Ahijah caught the new garment that was on him, and rent it in twelve pieces.

Adprehendensque Ahia pallium suum novum quo opertus erat scidit in duodecim partes.

For this is my blood of the new covenant, which is poured out for many for the remission of sins.

Hic est enim sanguis meus novi testamenti qui pro multis effunditur in remissionem peccatorum.

Behold, I will do a new thing. It springs forth now. Don’t you know it?

I will even make a way in the wilderness, and rivers in the desert.

Ecce ego facio nova et nunc orientur utique cognoscetis ea ponam in deserto viam

et in invio flumina.

Behold, I will make thee a new sharp threshing instrument having teeth:

thou shalt thresh the mountains, and beat them small, and shalt make the hills as chaff.

Ego posui te quasi plaustrum triturans novum habens rostra serrantia triturabis montes

et comminues et colles quasi pulverem pones.

Who also made us sufficient as servants of a new covenant; not of the letter,

but of the Spirit. For the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life.

Qui et idoneos nos fecit ministros novi testamenti non litterae

sed Spiritus littera enim occidit Spiritus autem vivificat.

For as the new heavens and the new earth, which I will make, shall remain before me,» says Yahweh,»so your seed and your name shall remain.

Quia sicut caeli novi et terra nova quae ego facio stare coram me dicit Dominus sic stabit semen vestrum et nomen vestrum.

For, behold, I create new heavens and a new earth; and the former things shall not be remembered, nor come into mind.

Ecce enim ego creo caelos novos et terram novam et non erunt in memoria priora et non ascendent super cor.

To Jesus, the mediator of a new covenant, and to the blood of sprinkling that speaks better than that of Abel.

Et testamenti novi mediatorem Iesum et sanguinis sparsionem melius loquentem quam Abel.

Purge out the old yeast, that you may be a new lump, even as you are unleavened.

For indeed Christ, our Passover, has been sacrificed in our place.

Expurgate vetus fermentum ut sitis nova consparsio sicut estis azymi

etenim pascha nostrum immolatus est Christus.

By the way which he dedicated for us, a new and living way, through the veil, that is to say, his flesh;

Quam initiavit nobis viam novam et viventem per velamen id est carnem suam.

Continue Learning about Other Arts

What is the Latin translation for the word brass?

The Latin translation for Brass is Orichalcum.

What is the Latin translation for the word tourist in Latin?

The Latin word for Tourist is Viatór.

What is the latin translation of the word stealth?

Furtim is the Latin word for «by stealth»

What is the latin translation of the word blue?

The Latin word for blue is «venetus.»

What is the Latin translation for the word thorn in Latin?

aculeus

For the language of original Latin works created since the beginning of the 20th century, see Contemporary Latin. For the modern languages descended from ancient Latin, see Romance languages.

| New Latin | |

|---|---|

| Latina nova | |

Linnaeus, 1st edition of Systema Naturae is a famous New Latin text. |

|

| Region | Western World |

| Era | Evolved from Renaissance Latin in the 16th century; developed into contemporary Latin between 19th and 20th centuries |

|

Language family |

Indo-European

|

|

Early form |

Renaissance Latin |

|

Writing system |

Latin alphabet |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | la |

| ISO 639-2 | lat |

| ISO 639-3 | lat |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. |

New Latin[1] (more commonly called Neo-Latin by academics[2][3] or Modern Latin)[4] is the style of Literary Latin used, in original, scholarly, and scientific works, first in Italy in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries’ Italian Renaissance, and then across northern Europe after about 1500, as a key feature of the humanist movement.[5] Neo-Latin’s adoption throughout Europe was coincident with the rise of the printing press and of early modern schooling. Latin was learnt as a spoken language as well as written, as the vehicle of schooling and University education, while vernacular languages were still infrequently used in such settings. As such, Latin dominated early publishing, and made a significant portion of printed works until the nineteenth century.

Post-Classical Latin, including medieval, Renaissance and Neo-Latin, makes up the vast majority of extant Latin output, estimated as well over 99.99% of the totality.[6] More academic attention has been given to Neo-Latin studies in recent decades, and the role and influence of Latin output in this period has begun to be reassessed. Rather than being an adjunct to Classical Latin forms, or an isolated, derivative and now largely irrelevant cultural output, Neo-Latin literature is seen as vital context for understanding the vernacular cultures in the periods where Latin was in widespread productive use. Additionally, Classical reception studies have begun to assess the differing ways that Classical culture was understood in different nations and times. Latin language materials form an important part of this dialogue.

In Neo-Latin’s most productive phase, it dominated science, philosophy, law, theology, and was important for history, literature, plays and poetry. It was a pan-European language for the dissemination of knowledge, and communication between people with different vernaculars, in the Res Publica Litterarum.[7] Even as Latin receded in importance after 1650, it remained vital for international communication of works, many of which were popularised in Latin translation, rather than as vernacular originals. This in large part explains the continued use of Latin in Scandinavian countries, and Russia, to disseminate knowledge, until the late eighteenth century.

From the mid to late seventeenth century, Latin became largely learnt as a written and read language, with little emphasis on oral fluency. Through the eighteenth century, while it still dominated education, its position alongside Greek was increasingly attacked and began to erode. In the nineteenth century, education in Latin (and Greek) focused increasingly on reading and grammar, and mutated into the ‘classics’ as a topic, although it often still dominated the school curriulum, especially for students aiming at University entry. Learning moved gradually away from poetry composition and other written skills; as a language, its usage was increasingly passive outside of classical commentaries and other specialised texts.

Latin remained in active use in eastern Europe and Scandinavia for a longer period. In Poland, it was used as a vehicle of local government. This extended to those parts of Poland absorbed by Germany. Latin was used as a common tongue between parts of Austrian Empire, particularly by Hungary and Croatia until the 1840s. Croatia maintained a Latin poetry tradition through the nineteenth century. Latin also remained the language of the Catholic Church and of oral debate at a high level in international conferences until the mid twentieth century.

Over time, and especially in its later phases after its practical value had severely declined, education that included strong emphasis on Latin and Greek became associated with elitism and as a deliberate class barrier to entry of educational institutions.

Some authors including C. S. Lewis have criticised the Neo-Latin and classicising nature of humanistic Latin teaching for creating a dynamic for purification and ossification of Latin, and thus its decline from a more productive medieval background. Modern Neo-Latin scholars tend to reject this, as for instance word formation and even medieval uses continued; but some see a kernel of truth, in that the standards of Latin were set very high, making it hard to achieve the necessary confidence to use Latin.[8] In any case, other factors are certainly at play, particularly the widening of education and its needs to address many more practical areas of knowledge, many of which were being written about for national audiences in the vernacular.

Modern scholarly and technical nomenclature, such as in zoological and botanical taxonomy and international scientific vocabulary, draws extensively from Neo-Latin vocabulary, often in the form of classical or neoclassical compounds. Neo-Latin includes extensive new word formation. As a language for full expression in prose or poetry, however, it is sometimes distinguished from Contemporary Latin.[citation needed]

Large parts of Latin vocabulary have seeped into English, French and several Germanic languages, particularly through Neo-Latin. In the case of English, about 60% of the lexicon can trace its origin to Latin, thus many English speakers can recognize Neo-Latin terms with relative ease as cognates are quite common.

Extent[edit]

Classicists use the term «Neo-Latin» to describe the Latin that developed in Renaissance Italy as a result of renewed interest in classical civilization in the 14th and 15th centuries.[9][10]

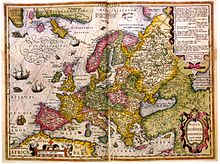

Jodocus Hondius’ map Nova Europae Descriptio of 1619, printed during the peak of Neo-Latin’s productive heights

Neo-Latin also describes the use of the Latin language for any purpose, scientific or literary, during and after the Renaissance. The beginning of the period cannot be precisely identified. The spread of secular education, the acceptance of humanistic literary norms, and the wide availability of Latin texts following the invention of printing, mark the transition to a new era of scholarship at the end of the 15th century, but there was no simple, decisive break with medieval traditions. Rather, there was a process of change in education, choice of literary and stylistic models, and a move away from medieval techniques of language formation and argumentation. While Latin remained an actively used language, the process of emulating Classical models did not become complete.[11] For instance, Catholic traditions preserved some features of medieval Latin, given the continued influence of some aspects of medieval theology.[12] In secular texts, such as scientific, legal and philosophical works, neologisms continued to be needed, so while Neo Latin authors might choose new formulations, they might also continue to use customary medieval forms, but in either case, could not aim for a purified Classical Latin vocabulary.[13]

The exact size of the Neo-Latin corpus is currently incalculable, but dwarfs that of Latin in all other periods combined.[14] Given the extent of potential records, from printed works, through to bureaucratic records and personal notes, there is extensive basic work to be done in cataloguing what is available, as well as in digitisation and translation of important works.[15]

The end of the Neo-Latin period is likewise indeterminate, but Latin as a regular vehicle of communicating ideas became rare following the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire as well as the Congress of Vienna where French replaced Latin as the language of diplomacy. By 1900, Latin survived primarily in international scientific vocabulary and taxonomy, or more actively, in the upper echelons of the Catholic church. The term «Neo-Latin» came into widespread use towards the end of the 1890s among linguists and scientists.

Neo-Latin was, at least in its early days, an international language used throughout Catholic and Protestant Europe, as well as in the colonies of the major European powers. This area consisted of most of Europe, including Central Europe and Scandinavia; its southern border was the Mediterranean Sea, with the division more or less corresponding to the modern eastern borders of Finland,[16] the Baltic states, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and Croatia.[17]

Latin was taught extensively in the USA, during the colonial period on the European model of Latin medium education, but was among the first to allow this monopoly to recede. Both Latin and the Classics were very influential nevertheless, and supported an active Latin literature, especially in poetry.[18]

Latin played a strong role in education and writing in early colonial Mexico, Brazil and in other parts of Catholic Americas.[19] Catholicism also brought Latin to India, China and Japan.[20]

Russia’s acquisition of Kyiv in the later 17th century introduced the study of Latin to Russia. Russia relied on Latin for some time as a vehicle to exchange scientific knowledge. Nevertheless, the use of Latin in Orthodox eastern Europe did not reach pervasive levels due to their strong cultural links to the cultural heritage of Ancient Greece and Byzantium, as well as Greek and Old Church Slavonic languages.

History[edit]

Beginnings[edit]

Erasmus stood at the forefront of the movement to reform Latin and learning

Neo-Latin began in Italy with the rise of Renaissance Latin and humanist reform of Latin education, then brought to prominence in northern Europe by writers such as Erasmus, More, and Colet.

Medieval Latin had been the practical working language of the Roman Catholic Church, taught throughout Europe to aspiring clerics and refined in the medieval universities. It was a flexible language, full of neologisms and often composed without reference to the grammar or style of classical (usually pre-Christian) authors.

The Renaissance reinforced the position of Latin as a spoken and written language by the scholarship by the Renaissance Humanists. Although scholarship initially focused on Ancient Greek texts, Petrarch and others began to change their understanding of good style and their own usage of Latin as they explored the texts of the Classical Latin world. Skills of textual criticism evolved to create much more accurate versions of extant texts through the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and some important texts were redisovered. Comprehensive versions of author’s works were published by Isaac Casaubon, Joseph Scaliger and others.[21] Nevertheless, despite the careful work of Petrarch, Politian and others, first the demand for manuscripts, and then the rush to bring works into print, led to the circulation of inaccurate copies for several centuries following.[22]

As the humanist reformers sought both to purify Latin grammar and style, and to make Latin applicable to concerns beyond the ecclesiastical, they began to create a body of Latin literature outside the bounds of the Church. Nevertheless, studies and criticism of Biblical translations were a particular and important focus of early Humanism, in Italy and beyond.[23]

Prominent Neo-Latin writers who were admired for their style in this early period included Petrarch, Salutati, Bruni, Ficino, Pico della Mirandola in Italy; the Spaniard Juan Luis Vives, and in northern Europe, the German Celtis.[24]

In the late 1400s, some schools in the Low Countries were using the new Italian standards of Latin. Erasmus and other pupils promoted the new learning and Latin standards. The Low Countries established itself as a leading centre of humanism and Neo-Latin; Rotterdam and Leuven were especially well known for these intellectual currents.[25]

Neo-Latin developed in advance and in parallel with vernacular languages, and not necessarily in direct competition with them.[26] Frequently the same people were codifying and promoting both Latin and vernacular languages, in a wider post medieval process of linguistic standardisation.[27] However, Latin was the first language that was available, fully formed, widely taught and used internationally across a wide variety of subjects. As such, it can be seen as the first «modern European language».[28]

It should also be noted that for Italian reformers of written Latin, there was no clear divide between Italian and Latin; the latter was seen by Petrarch for example as an artificial and literary version of the spoken language. While Italian in this period also begins to be used as a separate written language, it was not always seen as wholly separate from Latin.[29]

Height[edit]

The Protestant Reformation (1520–1580), though it removed Latin from the liturgies of the churches of Northern Europe, promoted the reform of the new secular Latin teaching.[30] The period during and after the Reformation, coinciding with the growth of printed literature, saw the growth of an immense body of Neo-Latin literature, on all kinds of secular as well as religious subjects.

The heyday of Neo-Latin was 1500–1700, when in the continuation of the Medieval Latin tradition, it served as the lingua franca of science, medicine, legal discourse, theology, education, and to some degree diplomacy in Europe. Classic works such as Thomas More’s Utopia were published. Other prominent writers of this period include Dutchmen Grotius and Secundus and Scotsman George Buchanan.[31] Women too, while rarely published, also wrote and composed poetry in Latin, Elizabeth Jane Weston being the most well known example.[32]

Later well-known Latin works include Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687).

Latin in school education 1500-1700[edit]

Throughout this period, Latin was a universal school subject, and indeed, the pre-eminent subject for elementary education in most of Europe and other places of the world that shared its culture. Schools were variously known as grammar school in Britain, Latin school in France, Germany, the Netherlands and colonial North America, and also Gymnasium in Germany and many other countries.

Latin was frequently the normal medium of education, both for teaching the Latin language, and for other subjects. Fluency in spoken Latin was an objective as well as the ability to read and write; evidence of this includes the emphasis on use of diacritics to maintain understanding of vowel quantity, which is important orally, and also on the use of Colloquia for children’s learning, which would help to equip the learner with spoken vocabulary for common topics, such as play and games, home work and describing travel. In short, Latin was taught as a «completely normal language»,[33] to be used as any other. Colloquia would also contain moral education. At a higher level, Erasmus’ Colloquia helped equip Latin speakers with urbane and polite phraseology, and means of discussing more philosophical topics.[34]

Changes to Latin teaching varied by region. In Italy, with more urbanised schools and Universities, and wider curricula aimed at professions rather than just theology, Latin teaching evolved more gradually, and earlier, in order to speed up the learning of Latin.[35] For instance, initial learning of grammar in a basic Latin word order followed the practice of medieval schools. In both medieval and Renaissance schools, practice in Latin written skills would then extend to prose style composition, as part of ‘rhetoric’. In Italy, for prose for instance, a pupil would typically be asked to convert a passage in ordo naturalis to ordo artificialis, that is from a natural to stylised word order.[36] Unlike medieval schools, however, Italian Renaissance methods focused on Classical models of Latin prose style, reviving texts from that period, such as Cicero’s De Inventione or Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria.[37]

Teaching of specific, gradually harder Latin authors and texts followed rhetorical practice and learning. In Italy, during the medieval period, at different periods, Classical and Christian authors competed for attention, but the Renaissance and Neo-Latin period saw a decisive move back to authors from the Classical period, and away from non-Classical ‘minor’ authors such as Boethius, whose language was simpler.[38]

John Calvin was among the promoters of reform of Latin education, working with Corderius

The changes to schooling in Northern Europe were more profound, as methods had not evolved as quickly. Adopting Italian innovations, changes to the teaching of grammar and rhetoric were promoted by reformers including Calvin, Melanchthon and Luther.[39] Protestants needed Latin to promote and disseminate their ideas, so were heavily involved with the reform of Latin teaching. Among the most influential of these reformers was Calvin’s Latin teacher and educational collaborator Corderius, whose bilingual colloquies were aimed at helping French speaking children learn to speak Latin.[40]

Among Latin schools, the rapid growth of Jesuit schools made them known for their dedication to high attainment in written and spoken Latin to educate future priests. This took place after the Catholic church affirmed their commitment to Latin in the liturgy and as a working language within the hierarchy at the Council of Trent in 1545–63. Jesuit schools were particularly well known for their production of Latin plays, exclusive use of spoken Latin and emphasis on classical written style.[41]

However, the standards ultimately achieved by the whole school system were uneven. Not all students would acquire Latin at a high standard. Even in this period, an excessive focus on grammar and poor teaching methods were seen by reformers as a barrier to acquisition of Latin. Comenius for instance was credited with significant attempts to make Latin more accessible through use of parallel Latin and native language texts, and more interesting through acquisition of vocabularly and the use of modern and more relevant information in texts. Others worried whether it was appropriate to give so much emphasis on abstract language skills, such as Latin poetry composition. As time went on, the difficulties with Latin teaching began to lead to calls to move away from an emphasis on spoken Latin and the introduction of more native language medium teaching.

Latin in University education[edit]

Christophorus Stimmelius, the German author of the first and highly successful comedy about student life

At the beginning of the Renaissance, Universities in northern Europe were still dominated by theology and related topics, while Italian universities were teaching a broader range of courses relating to urban professions such as law and medicine. All universities required Latin proficiency, obtained in local grammar schools, to obtain admittance as a student. Throughout the period, Latin was the dominant language of university education, where rules enforced against the use of vernacular languages. Lectures and debates took place in Latin, and writing was in Latin, across the curriciculum.

Many universities hosted newly or recently-written Latin plays, which formed an significant body of literature before 1650. Plays included satires on student life, such as the play Studentes (Students), which went through many reprints.

Enforcement of Latin-only rules tended to decline especially after 1650.

Latin in academia, law, science and medicine[edit]

A fifteenth century lecture

Latin dominated topics of international academic and scientific interest, especially at the level of abstract thought addressed to other specialists. To begin with, knowledge was already transmitted through Latin and it maintained specialised vocabularies not found in vernacular languages. This did not preclude scientific writings also existing in vernaculars; for example Galileo wrote some of whose scientific writings were in Latin, while others were in Italian, the latter less academic and intended to reach a wider audience using the same ideas with more practical applications.

Over time, the use of Latin continued where international communication with specialist audiences was paramount. Later, where some of the discourse moved to French, English or German, translations into Latin would allow texts to cross language boundaries, while authors in countries with much smaller language populations or less known languages would tend to continue to compose in Latin.

Latin was of course the major language of theology. Both Catholic and Protestant writers published in Latin. While Protestant writers would also write in vernaculars, Latin was important for international dissemination of ideas.

Legal discourse, medicine, philosophy and sciences started from a strong Latin tradition, and continued as such. This began to change in the late seventeenth century, as philosophers and others began to write in their native language first, and translate into Latin for international audiences. Translations would tend to prioritise accuracy over style.

Latin and religious usage[edit]

The Catholic church made exclusive use of Latin in the liturgy, resisting attempts even in the New World and China to diverge from it. As noted above, Jesuit schools fuelled a high standard of Latinity, and this was also supported by the growth of seminaries, as part of the Counter Reformation’s attempts to revitalise Catholic institutions.

While in Protestant areas, Latin was pushed out of the Church, this did not make Protestants hostile to Latin in education or universities. Latin in fact remained a kind of bridge of communication across religious as well as linguistic divides in the Res Publica Litterarum.

One exception to the general rule of vernacular services in Protestant countries can be observed in the Anglican Church, with the publication of the Book of Common Prayer of 1559, a Latin edition was published in 1560 for use in universities such as Oxford and the leading grammar and «public schools» (in the period, English schools established with charitable structures open to the general public; now a kind of private academy), where the liturgy was still permitted to be conducted in Latin.[42][43]

Latin as a literary vehicle[edit]

In this period, it was common for poets and authors to write in Latin, either in place or in addition to their native language. Latin was a language for ‘high art’ in an «eternal language», that authors supposed might outlast contemporary vernacular writings. It allowed for an international readership that shared the same Classical and recent Latin cultural reference points.

The literature did not, though, stand apart from vernaculars, as naturally allusions and the same reference points could flow across language boundaries.[44] However, these dynamics have become less well understood, as academics and other readers are not as familiar with the Latin works of the period, sometimes resulting in simpistic notions of competition and replacement of Latin over time. The actual processes were more complicated and are now a focus of Neo-Latin studies. For instance, stylistic borrowings flowed from Latin to the Dutch vernacular, where models were lacking in the latter.[45]

The Scottish poet John Barclay is among the internationally influential Latin writers of the seventeenth century

Outputs included novels, poems, plays and occasional pieces, stretching across genres analogous to those found in vernacular writings of the period, such as tragedy, comedy, satire, history and political advice.[46] Epistulary (letter) writing containing poems and prose, designed for publication rather than purely receipt, had Classical antecedents and often contained strong elements of self-promotion.[47]

Some of these genres are harder for modern readers to evaluate; for instance many poems were written for specific occasions, such as appointments or institutional events. To modern audiences, such poetry appears contrived at its inception, so it is easy for the reader to assume a lack of pathos or skill.[48]

At the time that many of these works were written, writers viewed their Latin output as perhaps we do high art; a particularly refined and lofty activity, for the most educated audiences. Moreover, there was a hope of greater, international recognition, and that the works written in the ‘Eternal language’ of Latin would outlast writings in the vernacular.

Some very influential works were written in Latin which are not always commonly remembered, despite their ground-breaking nature. For example, Argenis, by John Barclay was perhaps the first modern historical novel, and was popular across Europe.[49]

Opinions vary about the achievements of this literary movement, and also the extent to which it reached its goal of being ‘classical’ in style. Modern critics sometimes claim that the output of Neo-Latinists was largely derivative and imitative of Classical authors. Latin authors themselves could recognise the dangers of imitation caused by the long training they were given in ingesting compositional techniques of Classical writers, and could struggle against it.[50] From another perspective, the «learned artifice» of Neo-Latin writing styles requires that we understand that «one of the most fundamental aspects of this artifice is imitation».[51] Different approaches to imitation can be discerned, from attempting to adopt the style and manner of a specific author, especially of Cicero, through to syntheses of Latin from good authors, as suggested by Angelo Poliziano, taking elements from a range, to provide what Tunberg calls an «eclectic» style that was «new from the perspective of the whole creation».[52] The use of Latin exclusively as used by Cicero was heavily satirised by Erasmus who proposed a more flexible approach to Latin as a medium.[53][54]

Other critics have claimed that the expressive abilities of writers could not truly reach the same heights as in their native language; such concerns were sometimes expressed by contemporaries especially as time went on and vernaculars became more established. On the other hand, this criticism at the very least ignores the early age at and intensity with which Latin was acquired.

Standards of written Latin[edit]

Not all Latin aspired to be high literature, and whether it did or not, standards varied. In England, among scholarly works such as dissertations through the sixteenth century, written Latin improved in morphological accuracy, but sentence construction and idiom often reflected the vernacular. Standards were most classical and writing more fluid in France and Italy. Similar patterns have been found in Sweden, where academic Latin tended to be very accurate in terms of morphology, but less Classical in its sentence patterns. In vocabulary and spelling, usage tend to be quite eclectic, using medieval forms and reusing Classical terms with modern meanings. In any case, it was accepted that technical terms would require neologisms.[55]

There are occassional differences between Classical and Neo-Latin, which can sometimes be assumed to be mistakes of the authors. However, careful analysis of available grammars often shows these differences to be based on the understanding of the grammar rules at the time. For instance, many grammarians believed that all names of rivers were masculine, even those ending in -a.[56]

Additionally, Neo-Latin authors tended to form new unattested words, such as abductor[57] or fulminatrix[58], by using Classical rules. Helander says:

«Apparently the authors did not care whether these words existed in the preserved Latin literature, as long as they were regularly formed. As a rule, their judgement was very sound, and in most cases we will not as readers realize that we are dealing with neologisms … A large number of them were probably on the lips of the ancient Romans, although they have not survived in the texts preserved to us. One might wonder whether we are right in calling such words ‘neologisms’.»[59]

The words used derived from a wider set of authors than just the ‘classical’ period, especially among authors aiming at a higher level of style.[60] Similarly, some Classical words which were uncommonly used were in much greater currency, such as adorea (glory).[61]

The Latin used in scientific publications can be perceived as tending towards a simpler modern idiom, perhaps following the language patters of the writers’ native language. Often it served a clear, less literary purpose, however, of providing an accurate international Latin text or translation.

Latin as a spoken language[edit]

As a learnt language, levels of fluency would have varied. Discussions in specialised topics between specialists, or between educated people from different native language backgrounds would be preferred. Even among highly proficient Latin writers, sometimes spoken skills could be much lower, reflecting reticence for making mistakes in public, or simple lack of oral practice.

As noted below, an important feature of Latin in this period was that pronunciation tended to national or even local practice. This could make especially initial spoken communication difficult between Latinists from different backgrounds; English and French pronunciation being notably odd.[62] In terms of status, the Italian pronunciation tended to have higher status and acceptability.

From some time in the seventeenth century, Latin oral skills began to decline. Complaints about standards of oral Latin can be increasingly found from this time onwards.[63]

Latin as an official and diplomatic language[edit]

Official and diplomatic settings are specific cases where use of oral and conversational Latin would have taken place, in legal settings, Parliaments or between negotiators. Use of Latin would extend of course also to set speeches and texts such as treaties, but would also be the medium in which details would be discussed and problems resolved.

Latin was an official language of Poland, recognised and widely used.[64][65][66][67] between the 9th and 18th centuries, commonly used in foreign relations and popular as a second language among some of the nobility.[68]

Through most of the 17th century, Latin was also supreme as an international language of diplomatic correspondence, used in negotiations between nations and the writing of treaties, e.g. the peace treaties of Osnabrück and Münster (1648). As an auxiliary language to the local vernaculars, Neo-Latin appeared in a wide variety of documents, ecclesiastical, legal, diplomatic, academic, and scientific. While a text written in English, French, or Spanish at this time might be understood by a significant cross section of the learned, only a Latin text could be certain of finding someone to interpret it anywhere between Lisbon and Helsinki.

The use of Latin in diplomatic contexts was especially important for smaller nations which maintained Latin for a variety of international purposes, who therefore pressed for it even as French established itself as a more common medium for diplomacy.

Eighteenth century decline[edit]

A diminishing audience combined with diminishing production of Latin texts pushed Latin into a declining spiral from which it has not recovered. As it was gradually abandoned by various fields, and as less written material appeared in it, there was less of a practical reason for anyone to bother to learn Latin; as fewer people knew Latin, there was less reason for material to be written in the language. Latin came to be viewed as esoteric, irrelevant, and too difficult. As languages like French, Italian, German, and English became more widely known, use of a ‘difficult’ auxiliary language seemed unnecessary—while the argument that Latin could expand readership beyond a single nation was fatally weakened if, in fact, Latin readers did not compose a majority of the intended audience.

Latin in school education in the 1700s[edit]

The use of Latin in education began to come under serious attack during the eighteenth century, as the need for education widened, and the relevance of Latin diminished. However, these changes met resistance.

In the American colonies, calls for more practical education began to grow in the 1750s. In Poland, attempts to roll back the place of Latin were made in 1774, to make it a subject and to cease with spoken Latin, but hit resistance and were withdrawn in 1778, when Latin was restored as a spoken medium. Attempts to introduce Italian and reduce Latin teaching in Piedmont in the 1790s also hit problems, not least due to the divergence between the local dialect and standard Italian; the changes were withdrawn, and children continued to learn and read and write in Latin before other languages.[69]

In France, under the Ancien Regime, teaching remained largely focused on Latin until the Revolution. Although some moves were made to teach Latin grammar in French, and to learn to read and write in French first, these tended to be limited to urban centres and state-founded colleges such as those in Paris. Children learnt to read and write in Latin before French in most of the coutryside until the 1790s. Use of spoken Latin in schools, however, reduced through the century, particularly from the 1750s. Gradually Latin in schools moved from a language taught for usage and production to written comprehension.[70]

Latin in university education in the 1700s[edit]

At Universities, however, Latin retained its grip. In French universities, Latin remained the dominant language of tuition, with nearly all courses being delivered and examined in Latin.[71] At Oxford, Latin-only rules remained in force, but there is clear evidence of a decline in spoken Latin standards, and it was no longer expected outside of classes. Elsewhere, courses in technical subjects tended to move towards the vernacular, while some were delivered in both Latin and vernaculars. Courses using Italian become more common from the 1750s, in subjects such as commerce and mathematics. In any case, even when courses were delivered in vernaculars, formal occassions such as inagural lectures and ceremonies often remained in Latin.[72]

Sciences and Academia[edit]

In the early part of the 1700s, Latin was still making a significant contribution to academic publishing, but was no longer dominant. For example, over 50% were in Latin of the works published in Oxford between 1690 and 1710 were in Latin, and 31% of the total publications mentioned in the French Biliothèque raisonnée des ouvrages des savants de l’Europe between 1728–1740.[73]

Regional and subject differences counted for a lot in the choice of language and audience. An example of the transition towards the vernacular in England can be seen in Newton’s writing career, which began in Neo-Latin and ended in English (e.g. Opticks, 1704). By contrast, while German philosopher Christian Wolff (1679–1754) popularized German as a language of scholarly instruction and research, and wrote some works in German, he continued to write primarily in Latin, so that his works could more easily reach an international audience (e.g., Philosophia moralis, 1750–53).

Around 20% of academic periodicals were in Latin. Latin was particularly well-used in the German-speaking world, where the vernacular was not as well established. Erudition, theology, science and medicine were topics that were often addressed in Latin, such as by the long running medical journal Miscellania curiosa medico-physica printed from 1670 until 1791. Some periodicals were general in nature, such as the Acta litteraria Bohemiae et Moraviae, from Prague, launched in 1744.[74]

Literature and poetry[edit]

As the 18th century progressed, the extensive literature in Latin being produced at the beginning slowly contracted. Latin literature tended to be produced in countries where the vernaculars were by themselves still likely to attract small readerships. Some well known, influential and popular Latin books were produced, for instance Iter Subterraneum, a fantastical allegory in 1741.

Spoken Latin in the 1700s[edit]

As late as the 1720s, Latin was still used conversationally, and was serviceable as an international auxiliary language between people of different countries who had no other language in common. For instance, the Hanoverian king George I of Great Britain (reigned 1714–1727), who had no command of spoken English, communicated in Latin with his Prime Minister Robert Walpole,[75] who knew neither German nor French.

There are also no shortage of recorded complaints about poor standards of spoken Latin in Universities and similar settings. While there is also praise, it is clear that oral skills were in decline. In academia, lectures began to include a vernacular summary at the end. In some contexts, such as Poland, it was simply accepted that oral Latin did not need to be perfected as a working administrative language. In other contexts, it led to pressure for the oral use of Latin to be abandoned.[76]

Latin shifted towards increasingly being a written rather than spoken language. Evidence for this includes changes in the use of diacritics in texts, which ceased to be used.

Diplomacy and official status[edit]

In the early 18th century, French replaced Latin as the dominant diplomatic language, due to the commanding presence in Europe of the France of Louis XIV. However, Latin continued to be preferred by some smaller nations such as Denmark and Sweden for some time.

Some of the last major international treaties to be written in Latin include the Treaty of Vienna in 1738 and the Treaty of Belgrade in 1739; after the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48) international diplomacy was conducted predominantly in French. Some more minor trade treaties were written in Latin in 1737 and 1756 between Denmark and the Sublime Porte.[77]

Latin retained a significant role in diplomatic correspondence beyond these dates. The Papacy, Holy Roman Empire, Sweden continued to prefer Latin for communications through the century. In any case, due to the need to consult prior historic agreements, Latin remained an important skill for diplomats and was provided for in their training.[78]

Prussia found Latin indispensible as late as 1798, for practical reasons in administrating partitioned Poland from the 1770s onwards, where Latin remained the main administrative language.[79] In central Europe, Latin retained an official status in Hungary and Croatia, as a neutral language.

Nineteenth century[edit]

By 1800 Latin publications were far outnumbered, and often outclassed, by writings in the modern languages. Latin literature lasted longest in very specific fields (e.g. botany and zoology) where it had acquired a technical character, and where a literature available only to a small number of learned individuals could remain viable. By the end of the 19th century, Latin in some instances functioned less as a language than as a code capable of concise and exact expression, as for instance in physicians’ prescriptions, or in a botanist’s description of a specimen. In other fields (e.g. anatomy or law) where Latin had been widely used, it survived in technical phrases and terminology. The perpetuation of Ecclesiastical Latin in the Roman Catholic Church through the 20th century can be considered a special case of the technicalizing of Latin, and the narrowing of its use to an elite class of readers.

Latin and Classical education[edit]

Despite the trends in the 1700s towards lessening emphasis on Latin, study of the language alongside Greek was given a significant boost after 1800 through a revival of humanist education, especially for elite education in France, Germany, England and elsewhere.[80]

In this model, Latin suffered in status against Ancient Greek, which was seen as the better aesthetic example, but both languages were deemed necessary for a «Classical education». Latin was still generally a requirement for University education. Composition skills were still needed for submission of theses, for instance, in the early part of the century.

In England, study of the Classics became more intense at institutions like Eton, or Charterhouse. In grammar schools, however, study of Latin had declined, stopped or become tokenistic in the majority of cases at the point of the Taunton Commission’s enquiry in 1864, a situation which it helped to reverse in the coming decades.[81]

The renewed emphasis on the study of Classical Latin as the spoken language of the Romans of the 1st centuries BC and AD, was similar to that of the Humanists but based on broader linguistic, historical, and critical studies of Latin literature. It led to the exclusion of Neo-Latin literature from academic studies in schools and universities (except for advanced historical language studies); to the abandonment of Neo-Latin neologisms; and to an increasing interest in the reconstructed Classical pronunciation, which displaced the several regional pronunciations in Europe in the early 20th century.

Coincident with these changes in Latin instruction, and to some degree motivating them, came a concern about lack of Latin proficiency among students. Latin had already lost its privileged role as the core subject of elementary instruction; and as education spread to the middle and lower classes, it tended to be dropped altogether.

Latin and the Classics were under pressure from the need for much broader, general education for the wider population. It was clearly not useful or appropriate for everyone to attain high levels of Latin or Greek. Nevertheless, as a requirement for University entry, it formed a barrier to access against people from less privileged backgrounds; this was even seen as good thing. In this way, education in Latin became increasingly associated with a kind of elitism, associated with the education of English «gentlemen» or the French bourgeoisie, and forming a common bond of references within these social classes.[82]

Latin and linguistics[edit]

As academic study of languages in Germany and elsewhere intensified, so did knowledge of Latin. This manifested itself in the proposal for restoring Classical pronunciation, but also in further refining knowledge of vowel quantity, use of grammatical constructions and the meaning of particular words. Study of non-standard Latin began. Overall, this intensified the purification, standardisation and academisation of Latin. In education, this led to an increasingly grammar based approach to learning in many countries, reinforcing its reputation for being difficult and abstruse.

Uses of Latin in the late 1800s[edit]

By 1900, creative Latin composition in many countries, for purely artistic purposes, had become rare. Authors such as Arthur Rimbaud and Max Beerbohm wrote Latin verse, but these texts were either school exercises or occasional pieces. However, the tradition was still strong enough in Holland, Croatia, Italy and elsewhere to sustain an annual Latin poetry competition, the Certamen Hoeufftianum, until 1978.[83]

Classicists themselves were the last redoubt for use of Latin in an academic context. Textual commentaries to Latin texts could be made in Latin, for instance. Academic papers in Classics journals could sometimes be published in Latin.

Some of the last survivals of Neo-Latin to convey information appear in the use of Latin to cloak passages and expressions deemed too indecent (in the 19th century) to be read by children, the lower classes, or (most) women. Such passages appear in translations of foreign texts and in works on folklore, anthropology, and psychology.[84] An example of this can be found in Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis (1886).

Official uses of Latin[edit]

A special case was the use of Latin in Hungary and Croatia, where it remained a language of government in the first half of the century. Papers were published in Latin in Hungary, and it was used as the language of Parliamentary debate. This was in large part a compromise between Hungarians and Croats, to both avoid the imposition of German, or their own languages, on each other. The legacy of the political situation meant that a strong Latin tradition continued in Croatia for some time afterwards, where Latin poetry continued to be produced for the remainder of the century.

The abolition of the Holy Roman Empire ended its use of Latin as an official language. Sweden continued to use Latin for diplomatic correspondence in the nineteenth century, as did the Vatican.

Latin from 1900 onwards[edit]

Latin as a language held a place of educational pre-eminence until the second half of the 19th century in the English speaking world. At that point its value was increasingly questioned; in the 20th century, educational philosophies such as that of John Dewey dismissed its relevance.[citation needed] At the same time, the philological study of Latin appeared to show that the traditional methods and materials for teaching Latin were dangerously out of date and ineffective.

Relics[edit]

This pocket watch made for the medical community has Latin instructions for measuring a patient’s pulse rate on its dial: enumeras ad XX pulsus, «count to 20 beats».

Ecclesiastical Latin, the form of Neo-Latin used in the Roman Catholic Church, remained in use throughout the period and after. Until the Second Vatican Council of 1962–65 all priests were expected to have competency in it, and it was studied in Catholic schools. It is today still the official language of the Church, and all Catholic priests of the Latin liturgical rites are required by canon law to have competency in the language.[85]

Neo-Latin is also the source of the biological system of binomial nomenclature and classification of living organisms devised by Carl Linnaeus, although the rules of the ICZN allow the construction of names that deviate considerably from historical norms. (See also classical compounds.) Another continuation is the use of Latin names for the surface features of planets and planetary satellites (planetary nomenclature), originated in the mid-17th century for selenographic toponyms. Neo-Latin has also contributed a vocabulary for specialized fields such as anatomy and law; some of these words have become part of the normal, non-technical vocabulary of various European languages.

Pronunciation[edit]

Neo-Latin had no single pronunciation, but a host of local variants or dialects, all distinct both from each other and from the historical pronunciation of Latin at the time of the Roman Republic and Roman Empire. As a rule, the local pronunciation of Latin used sounds identical to those of the dominant local language; the result of a concurrently evolving pronunciation in the living languages and the corresponding spoken dialects of Latin. Despite this variation, there are some common characteristics to nearly all of the dialects of Neo-Latin, for instance:

- The use of a sibilant fricative or affricate in place of a stop for the letters c and sometimes g, when preceding a front vowel.

- The use of a sibilant fricative or affricate for the letter t when not at the beginning of the first syllable and preceding an unstressed i followed by a vowel.

- The use of a labiodental fricative for most instances of the letter v (or consonantal u), instead of the classical labiovelar approximant /w/.

- A tendency for medial s to be voiced to [z], especially between vowels.

- The merger of æ and œ with e, and of y with i.

- The loss of the distinction between short and long vowels, with such vowel distinctions as remain being dependent upon word-stress.

The regional dialects of Neo-Latin can be grouped into families, according to the extent to which they share common traits of pronunciation. The major division is between Western and Eastern family of Neo-Latin. The Western family includes most Romance-speaking regions (France, Spain, Portugal, Italy) and the British Isles; the Eastern family includes Central Europe (Germany and Poland), Eastern Europe (Russia and Ukraine) and Scandinavia (Denmark, Sweden).

The Western family is characterized, inter alia, by having a front variant of the letter g before the vowels æ, e, i, œ, y and also pronouncing j in the same way (except in Italy). In the Eastern Latin family, j is always pronounced [ j ], and g had the same sound (usually [ɡ]) in front of both front and back vowels; exceptions developed later in some Scandinavian countries.

The following table illustrates some of the variation of Neo-Latin consonants found in various countries of Europe, compared to the Classical Latin pronunciation of the 1st centuries BC to AD.[86] In Eastern Europe, the pronunciation of Latin was generally similar to that shown in the table below for German, but usually with [z] for z instead of [ts].

| Roman letter | Pronunciation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | Western | Central | Eastern | |||||||

| France | England | Portugal | Spain | Italy | Romania | Germany | Netherlands | Scandinavia | ||

| c before «æ», «e», «i», «œ», «y» |

/ k / | / s / | / s / | / s / | / θ / | / tʃ / | / tʃ / | / ts / | / s / | / s / |

| cc before «æ», «e», «i», «œ», «y» |

/ kː / | / ks / | / ks / | / ss / | / kθ / | / ttʃ / | / ktʃ / | / kts / | / ss / | / ss / |

| ch | / kʰ / | / ʃ / | / tʃ / | / tʃ / | / tʃ / | / k / | / k / | / k /, / x / | / x / | / k / |

| g before «æ», «e», i», «œ», «y» |

/ ɡ / | / ʒ / | / dʒ / | / ʒ / | / x / | / dʒ / | / dʒ / | / ɡ / | / ɣ / or / x / | / j / |

| j | / j / | / j / | / ʒ / | / j / | / j / | |||||

| qu before «a», «o», «u» |

/ kʷ / | / kw / | / kw / | / kw / | / kw / | / kw / | / kv / | / kv / | /kw / | / kv / |

| qu before «æ», «e», «i» |

/ k / | / k / | / k / | |||||||

| s between vowels unless ss |

/ s / | / z / | / z / | / z / | / s / | / z / | / z / | / z / | / z / | / s / |

| sc before «æ», «e», «i», «œ», «y» |

/ sk / | / s / | / s / | / s / | / sθ / | / ʃ / | / stʃ /, / sk / (earlier / ʃt /) |

/ sts / | / s / | / s / |

| t before unstressed i+vowel except initially or after «s», «t», «x» |

/ t / | / ʃ / | / θ / | / ts / | / ts / | / ts / | / ts / | / ts / | ||

| v | / w / | / v / | / v / | / v / | / b / ([β]) | / v / | / v / | / f / or / v / | / v / | / v / |

| z | / dz / | / z / | / z / | / z / | / θ / | / dz / | / z / | / ts / | / z / | / s / |

Orthography[edit]

Latin grave inscription in Ireland, 1877; it uses distinctive letters U and J in words like APUD and EJUSDEM, and the digraph Œ in MŒRENTES

Neo-Latin texts are primarily found in early printed editions, which present certain features of spelling and the use of diacritics distinct from the Latin of antiquity, medieval Latin manuscript conventions, and representations of Latin in modern printed editions.

Characters[edit]

In spelling, Neo-Latin, in all but the earliest texts, distinguishes the letter u from v and i from j. In older texts printed down to c. 1630, v was used in initial position (even when it represented a vowel, e.g. in vt, later printed ut) and u was used elsewhere, e.g. in nouus, later printed novus. By the mid-17th century, the letter v was commonly used for the consonantal sound of Roman V, which in most pronunciations of Latin in the Neo-Latin period was [v] (and not [w]), as in vulnus «wound», corvus «crow». Where the pronunciation remained [w], as after g, q and s, the spelling u continued to be used for the consonant, e.g. in lingua, qualis, and suadeo.

The letter j generally represented a consonantal sound (pronounced in various ways in different European countries, e.g. [j], [dʒ], [ʒ], [x]). It appeared, for instance, in jam «already» or jubet «he/she orders» (earlier spelled iam and iubet).

It was also found between vowels in the words ejus, hujus, cujus (earlier spelled eius, huius, cuius), and pronounced as a consonant; likewise in such forms as major and pejor. J was also used when the last in a sequence of two or more i’s, e.g. radij (now spelled radii) «rays», alijs «to others», iij, the Roman numeral 3; however, ij was for the most part replaced by ii by 1700.

In common with texts in other languages using the Roman alphabet, Latin texts down to c. 1800 used the letter-form ſ (the long s) for s in positions other than at the end of a word; e.g. ipſiſſimus.

The digraphs ae and oe were typically written using the ligatures æ and œ (e.g. Cæsar, pœna) except when part of a word in all capitals, such as in titles, chapter headings, or captions. More rarely (and usually in 16th- to early 17th-century texts) the e caudata was used as a substitute for the digraphs.[citation needed]

Diacritics[edit]

Three kinds of diacritic were in common use: the acute accent ´, the grave accent `, and the circumflex accent ˆ. These were normally only marked on vowels (e.g. í, è, â); but see below regarding que.

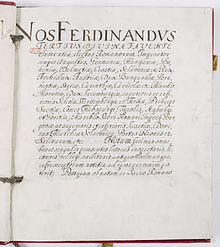

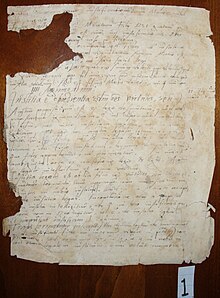

Handwriting in Latin from 1595

The acute accent marked a stressed syllable, but was usually confined to those where the stress was not in its normal position, as determined by vowel length and syllabic weight. In practice, it was typically found on the vowel in the syllable immediately preceding a final clitic, particularly que «and», ve «or» and ne, a question marker; e.g. idémque «and the same (thing)». Some printers, however, put this acute accent over the q in the enclitic que, e.g. eorumq́ue «and their». The acute accent fell out of favor by the 19th century.

The grave accent had various uses, none related to pronunciation or stress. It was always found on the preposition à (variant of ab «by» or «from») and likewise on the preposition è (variant of ex «from» or «out of»). It might also be found on the interjection ò «O». Most frequently, it was found on the last (or only) syllable of various adverbs and conjunctions, particularly those that might be confused with prepositions or with inflected forms of nouns, verbs, or adjectives. Examples include certè «certainly», verò «but», primùm «at first», pòst «afterwards», cùm «when», adeò «so far, so much», unà «together», quàm «than». In some texts the grave was found over the clitics such as que, in which case the acute accent did not appear before them.

The circumflex accent represented metrical length (generally not distinctively pronounced in the Neo-Latin period) and was chiefly found over an a representing an ablative singular case, e.g. eâdem formâ «with the same shape». It might also be used to distinguish two words otherwise spelled identically, but distinct in vowel length; e.g. hîc «here» differentiated from hic «this», fugêre «they have fled» (=fūgērunt) distinguished from fugere «to flee», or senatûs «of the senate» distinct from senatus «the senate». It might also be used for vowels arising from contraction, e.g. nôsti for novisti «you know», imperâsse for imperavisse «to have commanded», or dî for dei or dii.

Notable works (1500–1900)[edit]

Literature and biography[edit]

- 1511. Stultitiæ Laus, essay by Erasmus.

- 1516. Utopia[1] [2] by Thomas More

- 1525 and 1538. Hispaniola and Emerita, two comedies by Juan Maldonado.

- 1546. Sintra, a poem by Luisa Sigea de Velasco.

- 1602. Cenodoxus, a play by Jacob Bidermann.

- 1608. Parthenica, two books of poetry by Elizabeth Jane Weston.

- 1621. Argenis, a novel by John Barclay.

- 1626–1652. Poems by John Milton.

- 1634. Somnium, a scientific fantasy by Johannes Kepler.

- 1741. Nicolai Klimii Iter Subterraneum[3] [4], a satire by Ludvig Holberg.

- 1761. Slawkenbergii Fabella, short parodic piece in Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy.

- 1767. Apollo et Hyacinthus, intermezzo by Rufinus Widl (with music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart).

- 1835. Georgii Washingtonii, Americæ Septentrionalis Civitatum Fœderatarum Præsidis Primi, Vita, biography of George Washington by Francis Glass.

Scientific works[edit]

- 1543. De Revolutionibus Orbium Cœlestium by Nicolaus Copernicus

- 1545. Ars Magna by Hieronymus Cardanus

- 1551–58 and 1587. Historia animalium by Conrad Gessner.

- 1600. De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus et de Magno Magnete Tellure by William Gilbert.

- 1609. Astronomia nova by Johannes Kepler.

- 1610. Sidereus Nuncius by Galileo Galilei.

- 1620. Novum Organum by Francis Bacon.[5]

- 1628. Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus by William Harvey. [6]

- 1659. Systema Saturnium by Christiaan Huygens.

- 1673. Horologium Oscillatorium by Christiaan Huygens. Also at Gallica.

- 1687. Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica by Isaac Newton. [7]

- 1703. Hortus Malabaricus by Hendrik van Rheede.[8] [9]

- 1735. Systema Naturae by Carl Linnaeus. [10] [11]

- 1737. Mechanica sive motus scientia analytice exposita by Leonhard Euler.

- 1738. Hydrodynamica, sive de viribus et motibus fluidorum commentarii by Daniel Bernoulli.

- 1747. Antilucretius by Cardinal de Polignac

- 1748. Introductio in analysin infinitorum by Leonhard Euler.

- 1753. Species Plantarum by Carl Linnaeus.

- 1758. Systema Naturae (10th ed.) by Carolus Linnaeus.

- 1791. De viribus electricitatis in motu musculari by Aloysius Galvani.

- 1801. Disquisitiones Arithmeticae by Carl Gauss.

- 1810. Prodromus Florae Novae Hollandiae et Insulae Van Diemen by Robert Brown.[12]

- 1830. Fundamenta nova theoriae functionum ellipticarum by Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi.

- 1840. Flora Brasiliensis by Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius.[13]

- 1864. Philosophia zoologica by Jan van der Hoeven.

- 1889. Arithmetices principia, nova methodo exposita by Giuseppe Peano

Other technical subjects[edit]

- 1511–1516. De Orbe Novo Decades by Peter Martyr d’Anghiera.

- 1514. De Asse et Partibus by Guillaume Budé.

- 1524. De motu Hispaniæ by Juan Maldonado.

- 1525. De subventione pauperum sive de humanis necessitatibus libri duo by Juan Luis Vives.

- 1530. Syphilis, sive, De Morbo Gallico by Girolamo Fracastoro(transcription[permanent dead link])

- 1531. De disciplinis libri XX by Juan Luis Vives.

- 1552. Colloquium de aulica et privata vivendi ratione by Luisa Sigea de Velasco.

- 1553. Christianismi Restitutio by Michael Servetus. A mainly theological treatise, where the function of pulmonary circulation was first described by a European, more than half a century before Harvey. For the non-trinitarian message of this book Servetus was denounced by Calvin and his followers, condemned by the French Inquisition, and burnt alive just outside Geneva. Only three copies survived.

- 1554. De naturæ philosophia seu de Platonis et Aristotelis consensione libri quinque by Sebastián Fox Morcillo.

- 1582. Rerum Scoticarum Historia by George Buchanan (transcription)

- 1587. Minerva sive de causis linguæ Latinæ by Francisco Sánchez de las Brozas.

- 1589. De natura Novi Orbis libri duo et de promulgatione euangelii apud barbaros sive de procuranda Indorum salute by José de Acosta.

- 1597. Disputationes metaphysicæ by Francisco Suárez.

- 1599. De rege et regis institutione by Juan de Mariana.

- 1604–1608. Historia sui temporis by Jacobus Augustus Thuanus. [14] Archived 2013-05-12 at the Wayback Machine

- 1612. De legibus by Francisco Suárez.

- 1615. De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas by Matteo Ricci and Nicolas Trigault.

- 1625. De jure belli ac pacis by Hugo Grotius. (Posner Collection facsimile; Gallica facsimile)

- 1641. Meditationes de prima philosophia by René Descartes. (The Latin, French and English by John Veitch.)

- 1642–1658. Elementa Philosophica by Thomas Hobbes.

- 1652–1654. Œdipus Ægyptiacus by Athanasius Kircher.

- 1655. Novus Atlas Sinensis by Martino Martini.

- 1656. Flora Sinensis by Michael Boym.

- 1657. Orbis Sensualium Pictus by John Amos Comenius. (Hoole parallel Latin/English translation, 1777; Online version in Latin)

- 1670. Tractatus Theologico-Politicus by Baruch Spinoza.

- 1677. Ethica, ordine geometrico demonstrata by Baruch Spinoza.

- 1725. Gradus ad Parnassum by Johann Joseph Fux. An influential treatise on musical counterpoint.

- 1780. De rebus gestis Caroli V Imperatoris et Regis Hispaniæ and De rebus Hispanorum gestis ad Novum Orbem Mexicumque by Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda.

- 1891. De primis socialismi germanici lineamentis apud Lutherum, Kant, Fichte et Hegel by Jean Jaurès

See also[edit]

- Binomial nomenclature

- Botanical Latin

- Classical compound

- Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Neo-Latin Studies

- Romance languages, sometimes called Neo-Latin languages

Notes[edit]

- ^ «New Latin». Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ Gaudio, Andrew (14 November 2019). «Neo-Latin Texts Written Outside of Europe: A Resource Guide». Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020.

- ^ Sidwell, Keith Classical Latin-Medieval Latin-Neo Latin in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 13–26; others, throughout.

- ^ «modern Latin». Lexico. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021.

- ^ «When we talk about «Neo-Latin», we refer to the Latin … from the time of the early Italian humanist Petrarch (1304-1374) up to the present day» Knight & Tilg 2015, p. 1

- ^ Leonhardt 2009, p. 2

- ^ Waquet, Francoise The Republic of Letters, in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 66–79

- ^ Leonhardt 2009, p. 229

- ^ «What is Neo-Latin?». Archived from the original on 2016-10-09. Retrieved 2016-10-09.

- ^ Sidwell, Keith Classical Latin-Medieval Latin-Neo Latin in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 13–26; others, throughout.

- ^ See Sidwell, Keith Classical Latin — Medieval Latin — Neo Latin; and Black, Robert School in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 13–26 and pp. 217-231

- ^ Harris, Jason Catholicism in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 313–328

- ^ Sidwell, Keith Classical Latin-Medieval Latin-Neo Latin in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 13–26

- ^ Demo 2022, p. 3

- ^ Hofmann 2017, p. 521

- ^ Ström, Annika and Zeeberg, Peter Scandinavia, in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 493–508

- ^ Neagu, Cristina East-Central Europe, in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 509–524

- ^ Cottier, Jean-Francois, Westra, Haijo and Gallucci, John North America, in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 541–556

- ^ Laird, Andrew, Colonial Spanish America and Brazil in Klight & Tilg 2015, pp. 525–540

- ^ Golvers, Noël, Asia in Klight & Tilg 2015, pp. 557–573

- ^ Latin Studies in Bergin, Law & Speake 2004, p. 272

- ^ Criticism, textual in Bergin, Law & Speake 2004, p. 272

- ^ Taylor, Andrew, Biblical Humanism, and Sacré, Dirk The Low Countries, esp pp. 477-479, in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 295–312 and 477–489

- ^ Neo-Latin literature, in Bergin, Law & Speake 2004, pp. 338–9

- ^ Sacré, Dirk The Low Countries, esp pp477-479, in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 477–489

- ^ Deneire 2014, pp. 1–7

- ^ Leonhardt 2009, p. 224-5

- ^ Leonhardt 2009, p. 226

- ^ See Introduction, Deneire 2014, pp. 10–11

- ^ Black, Robert School, pp. 228-9 in Knight & Tilg 2015

- ^ Neo-Latin literature, in Bergin, Law & Speake 2004, pp. 338–9

- ^ Neo-Latin literature, in Bergin, Law & Speake 2004, pp. 338–9

- ^ Leonhardt 2009, pp. 223

- ^ Leonhardt 2009, pp. 222–224

- ^ Knight & Tilg 2015, p. 227

- ^ Black, Robert School in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 222–3

- ^ Black, Robert School in Knight & Tilg 2015, p. 224

- ^ Black, Robert School in Knight & Tilg 2015, p. 225

- ^ Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 228–9

- ^ Backus, Irena in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 336–7

- ^ Black, Robert School in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 228–9

- ^ Adams 1878, p. 77.

- ^ «Liber Precum Publicarum, The Book of Common Prayer in Latin (1560). Society of Archbishop Justus, resources, Book of Common Prayer, Latin, 1560. Retrieved 22 May 2012». Justus.anglican.org. Archived from the original on 12 June 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ Deniere, Tom, Neo-Latin literature and the Vernacular in Moul 2017, pp. 35–51

- ^ Thomas, Deneire Neo-Latin and Vernacular Poetics of Self-Fashioning in Dutch Occasional Poetry (1635–1640) in Deneire 2014, pp. 33–58

- ^ Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 27–216 See section one covering these and other genres

- ^ Papy, Jan, Leters in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 167–182

- ^ Moul 2017, pp. 7–8

- ^ Riley, Mark, Fiction in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 183–198

- ^ See Haskell, Yasmin, Conjuring with the Classics: Neo Latin Poets and their familiars, pp17-19 for an overview of these points and some arguments for and against originality in Moul 2017, pp. 17–34

- ^ Tunberg, Terence, in Moul 2017, pp. 237

- ^ Tunberg, Terence, Aproaching Neo-Latin Prose as Literature in Moul 2017, pp. 237–254

- ^ Baker, Patrick, Historiography in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 161

- ^ Sidwell, Keith Classical Latin-Medieval Latin-Neo Latin in Knight & Tilg 2015, pp. 20–21

- ^ Waquet 2001, pp. 124–127

- ^ Helander 2001, pp. 29–32

- ^ Helander 2001, p. 33 See Abductor: Wiktionary)

- ^ Helander 2001, p. 33 See Fulminatrix: Wiktionary)

- ^ Helander 2001, p. 33

- ^ Helander 2001, p. 33

- ^ Helander 2001, p. 32

- ^ Waquet 2001, pp. 160–163

- ^ Waquet 2001, pp. 160–163

- ^ Who only knows Latin can go across the whole Poland from one side to the other one just like he was at his own home, just like he was born there. So great happiness! I wish a traveler in England could travel without knowing any other language than Latin!, Daniel Defoe, 1728

- ^ Anatol Lieven, The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and the Path to Independence, Yale University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-300-06078-5, Google Print, p.48

- ^ Kevin O’Connor, Culture And Customs of the Baltic States, Greenwood Press, 2006, ISBN 0-313-33125-1, Google Print, p.115

- ^ Karin Friedrich et al., The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569–1772, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-58335-7, Google Print, p.88

- ^ Karin Friedrich et al., The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569–1772, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-58335-7, Google Print, p. 88

- ^ Waquet 2001, pp. 24–5

- ^ Waquet 2001, pp. 9–11

- ^ Waquet 2001, pp. 11–12

- ^ Waquet 2001, pp. 25–26

- ^ Waquet 2001, pp. 83–84

- ^ Waquet 2001, pp. 83–84

- ^ «Before I conclude the reign of George the First, one remarkable fact must not be omitted: As the king could not readily speak English, nor Sir Robert Walpole French, the minister was obliged to deliver his sentiments in Latin; and as neither could converse in that language with readiness and propriety, Walpole was frequently heard to say, that during the reign of the first George, he governed the kingdom by means of bad Latin.» Coxe, William (1800). Memoirs of the Life and Administration of Sir Robert Walpole, Earl of Orford. London: Cadell and Davies. p. 465. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

«It was perhaps still more remarkable, and an instance unparalleled, that Sir Robert governed George the First in Latin, the King not speaking English, and his minister no German, nor even French. It was much talked of that Sir Robert, detecting one of the Hanoverian ministers in some trick or falsehood before the King’s face, had the firmness to say to the German «Mentiris impudissime!»Walpole, Horace (1842). The Letters of Horace Walpole, Earl of Orford. Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard. p. 70. Retrieved June 2, 2010. - ^ Waquet 2001, pp. 160–163

- ^ Waquet 2001, p. p97-98

- ^ Waquet 2001, p. p98-99

- ^ Waquet 2001, p. 96

- ^ Waquet 2001, pp. 26–29

- ^ Waquet 2001, pp. 27–28

- ^ Waquet 2001, pp. 207–229

- ^ Sacré, Dirk p485, in Knight & Tilg 2015

- ^ Waquet 2001, pp. 243–254

- ^ This requirement is found under canon 249 of the 1983 Code of Canon Law. See «1983 Code of Canon Law». Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 1983. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Fisher, Michael Montgomery (1879). The Three Pronunciations of Latin. Boston: New England Publishing Company. pp. 10–11.

Further reading[edit]

History of Latin[edit]

- Ostler, Nicholas (2009). Ad Infinitum: A Biography of Latin. HarperPress. ISBN 978-0007343065.

- Churchill, Laurie J., Phyllis R. Brown, and Jane E. Jeffrey, eds. 2002. Women Writing in Latin: From Roman Antiquity to Early Modern Europe. Vol. 3, Early Modern Women Writing Latin. New York: Routledge.

- Tore, Janson (2007). A Natural History of Latin. Translated by Merethe Damsgaard Sorensen; Nigel Vincent. Oxford University Press.

- Leonhardt, Jürgen (2009). Latin: story of a World Language. Translated by Kenneth Kronenberg. Harvard. ISBN 9780674659964. OL 35499574M.

Neo-Latin overviews[edit]

- Butterfield, David. 2011. «Neo-Latin». In A Blackwell Companion to the Latin Language. Edited by James Clackson, 303–18. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- IJsewijn, Jozef with Dirk Sacré. Companion to Neo-Latin Studies. Two vols. Leuven University Press, 1990–1998.

- Knight, Sarah; Tilg, Stefan, eds. (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Neo-Latin. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190886998. OL 28648475M.

- Ford, Philip, Jan Bloemendal, and Charles Fantazzi, eds. 2014. Brill’s Encyclopaedia of the Neo-Latin World. Two vols. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Moul, Victoria, ed. (2017). A Guide to Neo-Latin Literature. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108820066. OL 29875053M.

- Waquet, Françoise (2001). Latin, or the Empire of a Sign: From the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Centuries. Translated by John Howe. Verso. ISBN 1-85984-402-2.

Neo-Latin studies[edit]

- Demo, Šime (2022). «A paradox of the linguistic research of Neo–Latin. Symptoms and causes». Suvremena lingvistika. 48 (93). doi:10.22210/suvlin.2022.093.01.

- De Smet, Ingrid A. R. 1999. «Not for Classicists? The State of Neo-Latin Studies». Journal of Roman Studies 89: 205–9.

- Ford, Philip. 2000. «Twenty-Five Years of Neo-Latin Studies». Neulateinisches Jahrbuch 2: 293–301.

- Helander, Hans (2001). «Neo-Latin Studies: Significance and Prospects». Symbolae Osloenses. 76 (1): 5–102. doi:10.1080/003976701753387950.

- Hofmann, Heinz (2017). «Some considerations on the theoretical status of Neo-Latin studies». Humanistica Lovaniensia. 66: 513-526.

- van Hal, Toon. 2007. «Towards Meta-neo-Latin Studies? Impetus to Debate on the Field of Neo-Latin Studies and its Methodology». Humanistica Lovaniensia 56:349–365.

Neo Latin specifics[edit]

- Bloemendal, Jan, and Howard B. Norland, eds. 2013. Neo-Latin Drama and Theatre in Early Modern Europe. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Burnett, Charles, and Nicholas Mann, eds. 2005. Britannia Latina: Latin in the Culture of Great Britain from the Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century. Warburg Institute Colloquia 8. London: Warburg Institute.

- Coroleu, Alejandro. 2010. «Printing and Reading Italian Neo-Latin Bucolic Poetry in Early Modern Europe». Grazer Beitrage 27: 53–69.

- de Beer, Susanna, K. A. E. Enenkel, and David Rijser. 2009. The Neo-Latin Epigram: A Learned and Witty Genre. Supplementa Lovaniensia 25. Leuven, Belgium: Leuven Univ. Press.

- Deneire, Thomas, ed. (2014). Dynamics of Neo-Latin and the Vernacular: Language and Poetics, Translation and Transfer. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 9789004269071.

- Godman, Peter, and Oswyn Murray, eds. 1990. Latin Poetry and the Classical Tradition: Essays in Medieval and Renaissance Literature. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Haskell, Yasmin, and Juanita Feros Ruys, eds. 2010. Latin and Alterity in the Early Modern Period. Arizona Studies in the Middle Ages and Renaissance 30. Tempe: Arizona Univ. Press

- Miller, John F. 2003. «Ovid’s Fasti and the Neo-Latin Christian Calendar Poem». International Journal of Classical Tradition 10.2:173–186.

- Tournoy, Gilbert, and Terence O. Tunberg. 1996. «On the Margins of Latinity? Neo-Latin and the Vernacular Languages». Humanistica Lovaniensia 45:134–175.

Other general sources[edit]