What Is a Market?

A market is a place where parties can gather to facilitate the exchange of goods and services. The parties involved are usually buyers and sellers. The market may be physical like a retail outlet, where people meet face-to-face, or virtual like an online market, where there is no direct physical contact between buyers and sellers. There are some key characteristics that help define a market, including the availability of an arena, buyers and sellers, and a commodity that can be purchased and sold.

Key Takeaways

- A market is a place where buyers and sellers can meet to facilitate the exchange or transaction of goods and services.

- Markets can be physical like a retail outlet, or virtual like an e-retailer.

- Other examples include illegal markets, auction markets, and financial markets.

- Markets establish the prices of goods and services that are determined by supply and demand.

- Features of a market include the availability of an arena, buyers and sellers, and a commodity.

Market

Understanding Markets

A market is any place where two or more parties can meet to engage in an economic transaction—even those that don’t involve legal tender. A market transaction may involve goods, services, information, currency, or any combination of these that pass from one party to another. In short, markets are arenas in which buyers and sellers can gather and interact.

Two parties are generally needed to make a trade. But, at minimum, a third party is required to introduce competition and bring balance to the market. As such, a market in a state of perfect competition, among other things, is characterized by a high number of active buyers and sellers.

Beyond this broad definition, the term market encompasses a variety of things, depending on the context. For instance, it may refer to the stock market, which is the place where securities are traded. It may also be used to describe a collection of people who wish to buy a specific product or service in a specific place, such as the Brooklyn housing market. Or it could refer to an industry or business sector, such as the global diamond market.

Certain decisions that help shape the market are determined by an economic system known as the market economy. In this system, factors like investments and the production, distribution, and pricing of goods and services are led by supply and demand from businesses and individuals. As such, a market economy is unplanned and is not part of a planned or command economy where the government dictates all of these factors. Examples of market economies include the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Japan.

In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulates the stock, bond, and currency markets. It puts provisions in place to prevent fraud while ensuring traders and investors have the right information to make the most informed decisions possible.

Supply and Demand

Whatever the context, a market establishes the prices for goods and other services. These rates are determined by supply and demand. The idea of supply and demand is one of the very basics of economics. Supply is created by the sellers, while demand is generated by buyers.

Markets try to find some balance in price when supply and demand are themselves in balance. But that balance can in itself be disrupted by factors other than price including incomes, expectations, technology, the cost of production, and the number of buyers and sellers participating.

To put it simply, the number of goods and services available is determined by what people want and how eager they are to buy. Sellers increase production when buyers demand more goods and services. Producers then increase their prices in order to realize a profit. When buyer demand decreases, companies have to drop their prices and, therefore, the number of goods and services they bring to market.

Physical and Virtual Markets

Markets may be represented by physical locations where transactions are made. These include retail stores and other similar businesses that sell individual items to wholesale markets selling goods to distributors. Or they may be virtual. Internet-based stores and auction sites such as Amazon and eBay are examples of markets where transactions can take place entirely online and the parties involved never connect physically.

Markets may emerge organically or as a means of enabling ownership rights over goods, services, and information. When on a national or other more specific regional level, markets may often be categorized as developed or developing markets. This distinction depends on many factors, including income levels and the nation or region’s openness to foreign trade.

The size of a market is determined by the number of buyers and sellers, as well as the amount of money that changes hands each year.

Types of Markets

Markets vary widely for a number of reasons, including the kinds of products sold, location, duration, size, and constituency of the customer base, size, legality, and many other factors. Aside from the two most common markets—physical and virtual—there are other kinds of markets where parties can gather to execute their transactions.

Underground Market

An underground or black market refers to an illegal market where transactions occur without the knowledge of the government or other regulatory agencies. Many illegal markets exist in order to circumvent existing tax laws. This is why many involve cash-only transactions or non-traceable forms of currency, making them harder to track.

Many illegal markets exist in countries that are economically developing and with planned or command economies where the government controls the production and distribution of goods and services. When there is a shortage of certain goods and services in the economy, members of the illegal market step in and fill the void.

Illegal markets can also exist in developed economies. These shadow markets, as they’re also known, become prevalent when prices control the sale of certain products or services, especially when demand is high. Ticket scalping is one example of an illegal or shadow market. When demand for concert or theater tickets is high, scalpers will step in, buy up a bunch, and sell them at inflated prices on the underground market.

Auction Market

An auction market brings many people together for the sale and purchase of specific lots of goods. The buyers or bidders try to top each other for the purchase price. The items up for sale end up going to the highest bidder.

The most common auction markets involve livestock, foreclosed homes, and art and antiques. Many operate online now. For example, the U.S. Treasury sells its bonds, notes, and bills via regular auctions.

Financial Market

The blanket term financial market refers to any place where securities, currencies, bonds, and other securities are traded between two parties. These markets are the basis of capitalist societies, and they provide capital formation and liquidity for businesses. They can be physical or virtual.

The financial market includes the stock exchanges such as the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), Nasdaq, the London Stock Exchange (LSE), and the TMX Group. Other kinds of financial markets include the bond market and the foreign exchange market, where people trade currencies.

Features of a Market

There are certain features that help define a market. These are necessary in order for the market to function. The following are the most basic characteristics that shape a market:

- Arena: This is the platform where transactions are conducted between buyers and sellers. Keep in mind that this doesn’t necessarily mean a physical location. It can also mean the area in which all parties involved are spread out.

- Buyers and Sellers: In order for the market to function, there must be buyers and there must be sellers. The market can’t exist if someone isn’t buying something that someone else is selling. These entities can be businesses, individuals, or even governments, and they can execute their transactions physically or virtually, thanks to the internet.

- One Commodity: A single market is dependent on a single commodity, so in order for a market to operate, a related commodity must be present. For instance, wheat is the commodity bought and sold in the wheat market. Electronics make up the electronics market en masse but can be broken down into subcategories.

There are other features, including competition, pricing, and the freedom to buy and sell goods and services.

Regulating Markets

Other than underground markets, most markets are subject to rules and regulations set by a regional or governing body that determines the market’s nature. This may be the case when the regulation is as wide-reaching and as widely recognized as an international trade agreement, or as local and temporary as a pop-up street market where vendors maintain order and rules among themselves.

How Do Markets Work?

Markets are arenas in which buyers and sellers can gather and interact. A market in a state of perfect competition is necessarily characterized by a high number of active buyers and sellers. The market establishes the prices for goods and other services. These rates are determined by supply and demand. Supply is created by the sellers, while demand is generated by buyers. Markets try to find some balance in price when supply and demand are themselves in balance.

What Is a Black Market?

A black market refers to an illegal exchange or marketplace where transactions occur without the knowledge or oversight of officials or regulatory agencies. They tend to spring up when there is a shortage of certain goods and services in the economy, or supply and prices are state-controlled. Transactions tend to be undocumented and cash-only, all the better to be untraceable.

How Are Markets Regulated?

Most markets are subject to rules and regulations set by a regional or governing body that determines the market’s nature. They can be international, national, or local authorities.

The Bottom Line

Markets are an important part of the economy. They allow a space where governments, businesses, and individuals can buy and sell their goods and services. But that’s not all. They help determine the pricing of goods and services and inject much-needed liquidity into the economy. By offering a place to conduct transactions, markets allow entities access to the capital they need to further their interests, whether that’s to fund infrastructure, fulfill growth plans, make purchases, or invest their money. This helps fuel innovation in order to secure a competitive edge in the marketplace.

Market

The term ‘market’ refers to the aggregate of all demand for a particular product or service, arising from the aggregate of all consumers, both existing and potential for the product. It means that the whole group of consumers of a particular product constitutes the ‘market’ for that product.

Philip Kotler states, “A market consists of all the potential customers sharing a particular need or wants who might be willing and able to engage in exchange to satisfy that need or want.”

Learn about:-

1. Definitions of Market 2. Meaning of Market 3. Concept 4. Characteristics 5. Importance 6. Evolution 7. Market Research 8. Market Structure 9. Types of Consumer Market 10. Methods for Estimating Area Market Demand 11. Entities 12. Benefits 13. Market Survey.

Market: Definitions, Meaning, Concept, Characteristics, Importance, Evolution, Types, Methods, Advantages and Benefits

Market – Definitions

A definition of the market is based on building on up-to-date picture of the parameters of the market. Its size, composition, consumption patterns and internal structure. This needs to be done regularly, as changes can occur rapidly with little apparent warning. The ability to define the market as tightly and accurately as possible is the measure of marketing staff who are on top of their jobs.

Many companies have the practice of maintaining a “Marketing Fact Book” for each product and brand area in which they have an interest. In Industrial markets problems can be caused by the difficulties faced when attempting to define the markets in categories such as components or processed products.

The greater the firm’s awareness of a market, the more management will become conscious of the different groups which make it up. This process of breaking up large heterogeneous groups into more homogeneous target audiences is central to the marketing process. A market is thus by definition comprises interest, purchasing power and willingness to service that satisfies a need.

Market segmentation is a method of dividing a large market into smaller groupings of consumers or organisations in which each segment has a common characteristic such as needs or behaviour.

Essentially a market could be considered to be a meeting place for making exchanges, where it is accepted that the relative value of different products is established. In practice, to be effective a market needs to have rules and procedures for their enforcement. This is the basis for the definition used by economists.

The word market is also often used to mean the individuals or organisations who are or could be purchasers of a particular product. Very often this can cause confusion. For instance, the UK car market could mean the 12 million existing car users, or more usually the 1.5 million or so new cars which are purchased in any one year. It is important always to use the word carefully so that its meaning is clear, and to ensure that you understand how it is being used when you come across it in your reading.

Market is a place where buyers and sellers meet. In other words we can say ‘Market’ means a group of sellers.

However, Traditionally the term ‘market’ has been used to describe a place where buyers and sellers gather to exchange goods and services, e.g., a fruit and vegetable market or a stock market.

In marketing, the term market refers to the group of consumers or organisations that is interested in the product, has the resource to purchase the product, and is permitted by law and other regulations to acquire the product.

Cournot, defines the ‘Market’ as “Economists understand by the term market, not any particular market place in which things are bought and sold, but the whole of any region in which buyers and sellers are in such free intercourse with one another that the prices of the same goods tend to be at equality easily and quickly.”

Philip Kotler states, “A market consists of all the potential customers sharing a particular need or wants who might be willing and able to engage in exchange to satisfy that need or want.”

So the size of the market depends upon the number of persons who have the unsatisfied needs and are potentially capable of performing the exchange.

A market (in contrast to marketing) may be defined as:

“The actual or potential buyers of a product”.

This means that a market is wider than individuals and it includes private and public sector organisations, supplier groups and purchasing groups. It is also wider than present or past buyers. It includes anyone or any organisation that is reasonably likely to buy a product in the future.

Kotler (1986) defined a product broadly as:

“… anything that can be offered to a market for attention, acquisition, use or consumption that might satisfy a want or need. It includes physical objects, services, persons, places, organisations and ideas”.

An organisation that hopes to sell its product in a market needs to study the market very carefully and may commission extensive market research.

It will need to examine the characteristics of the market such as:

(a) The people and organisations that make up the market

(b) The product that it is bought

(c) The purpose for which it will be bought and the needs it will satisfy

(d) The times and occasions (e.g. birthdays, setting up a new home or everyday purchases) when the product is bought

(e) The method used to buy the product (e.g. visit to retail outlet, regular order, telephone order or Internet shopping)

It should be remembered that people and organisations do not buy products for their own sake. Products are bought because they solve a problem or confer benefits upon their owners. For example, organisations do not purchase a car for a sales representative because it is a good thing in itself.

The car will be purchased because the organisation believes it will benefit from the sales representative’s ability to visit more customers each day and because it can be sure that its image will not be damaged by the representative arriving at customers premises driving a clapped-out banger.

Markets can differ in many ways. The main differences are size, competition, barriers and dynamism.

Market – Meaning

Traditionally, market refers to a physical location where buyers and sellers gather to exchange their goods. In the market, ownership and possession of products is transferred from the seller to the buyer and money acts as a medium of exchange and measure of value. Economists describe a market as a collection of buyers and sellers who transact over a particular product or service.

Marketers view sellers as the industry and buyers as the market. Business people use the term market to refer to various grouping of customers, i.e., Product market (Example- Television market), Geographic market (Example- African market) or Non- customer group such as labour market. Market also refers to the aggregate demand of the potential buyers for a product or service.

In this sense market means people with needs to satisfy, the money to spend and the will to spend money to satisfy their needs. Therefore the term “Market” has a wider meaning and it is not confined to a particular physical place. It is an area in which forces of demand and supply operate directly or by means of any kind of communication to bring about transfer in the title of the goods.

Marketing is an activity involving movement of goods and its basis as is market. Hence it will be helpful for the study of marketing, to understand origin of the word ‘Market’.

The word “Market” is derived from the Latin word ‘Marcatus’ meaning gathering for the purpose of commerce, fair.

Some scholars state that the word ‘Market’ is derived from the Latin word ‘Marcari’ or ‘Merx’ meaning trade, buy or merchandise goods. Latin notion basically dealt with buying or selling of goods.

Thus marketing refers to trading of goods through the process of buying and selling. And market is a place of business where marketing activities are organized. And therefore market contains present and prospective customers for a particular product or service.

Market – Concept

The term market has several meanings. It can be used in the sense of the network of institutions like wholesalers, dealers etc. dealing in the product. It can also be used to refer to the nature of demand for the product, as when we speak of the market for toothpaste. However, it must be remembered that the above two meanings of market are related yet distinct, so a change in one does not necessitate a change in the other.

Usually, market is used to identify competition and to break down the market into segments. If viewed this way, the ‘market for’ mill be referred to in relation to the function (s) served by the product. Products having the same utility and performing the same function will be competing with each other and hence in the same market. A firm’s business is defined in terms of technology, customer group and function(s) served. So it would be more appropriate to refer to (or define) market in terms of its function (or purpose) served, which in turn will coincide with the customer group it is to serve.

Going by the above description on the term ‘market’, it can be inferred that buyers in the same market seek products for broadly the same function. But buyers hold different beliefs on what their interpretation is about that product which performs the functions efficiently. As a result, they are aware of the various brand options and will be attracted to different offerings based on how the brand will cater more closely to their wants.

Market – 4 Main Characteristics

1. It shall be wide enough so that there is existence of a steady and continuous demand for the commodity under sale. If there is no steady demand there cannot be steady and continuous sale. If there is no steady demand there cannot be steady and continuous supply of the commodity. The suppliers can hold the stock when there is excess supply to adjust it with the demand.

2. There shall be facilities for movement of the goods so that the supply of a commodity may reach the market easily, regularly and timely.

3. The commodity must be capable of being identified and preferably be represented by sample or by description.

4. The title to or ownership of goods must pass easily from the seller to the buyer with minimum formalities.

5. There shall be freedom of entering into contracts by the buyers and the sellers among themselves for executing transactions of sale.

Market – Importance

1. Reciprocal Benefits – The buyers can get their goods for the satisfaction of their wants and the sellers also get their market for their merchandising operations.

2. Incentive to Producers – The goods are produced for marketing, i.e., selling to the consumers. In the absence of any market, the goods cannot be sold. The existence of a market provides incentive to the manufacturers to produce the goods.

3. Generation of Employment – The activities of repeated buying and selling of goods and services in a market call for the services to be rendered by different people. This way, a market creates opportunities of employment to people in various capacities like dealers and agents, etc.

4. Index of Economic Situation – The economic condition of a country can be gauged by the presence of a market. A country possessing an international or global market for its products and/or services is considered as an economically advanced one in the world of business.

5. Supply vs. Demand Adjustment – The existence of a market creates demand for goods and services. Certain raw materials like cotton, jute, etc. have seasonal supplies but their demands are regular and continuous. An organized market for them ensures adjustments between the demand and supplies and stabilization of prices over a long period.

Market – Evolution

Market as described by Latin word marcatus involved gathering of people with various commodities and goods or even services for sale. In the early stages trade was made with only Barter System involving exchange of goods in return of other goods on the basis of some common equality of value.

After the invention of money in business, the use of Barter System was discontinued from the market and more stabilized form of value exchange was introduced which helped trade and commerce to run smoothly. In today’s dynamic and rapidly developing environment market is a whole country or may be the whole world and it consists of people who are rapidly connected with each other for trading and business activities.

Financial transactions are also possible via internet, throughout the world. One can easily access whole market for purchasing single commodity and can very easily buy that particular product through e-commerce, online market. Payment options have also become very virtual.

Thus market is developed from busy streets and people with goods, who are waiting for buyer for purchase to a totally different scenario of virtual setup and across the globe with buyer and seller who are totally unknown to each other making business of buying and selling. Hence study is to be made covering this special aspect of technological advancement its effect on market conditions and even on traditional definition of market.

Market Research

Marketing decisions require a lot of information. The process of collecting and collating this information in a systematic and objective away is called market research.

It is defined by the American Marketing Association as:

“… The function that links the consumer, customer and public to the marketer through information – information used to identify and define marketing opportunities and problems; generate, refine and evaluate marketing actions; monitor marketing performance; and improve understanding of marketing as a process”.

The terms “market research”, “markets research” and “marketing research” sound very similar and are often used interchangeably. Technically, however, market research refers to any information about markets. Markets research is a part of market research and looks at the characteristics of markets. Marketing research deals with information relevant to marketing a specific product or service. To avoid confusion it is therefore helpful to divide market research into two main categories: markets research and marketing research.

Markets Research:

Research on markets is sometimes called “market intelligence”. It obtains information, usually quantitative, on many of the market characteristics such as the size of a market, growth, use of technology, dynamism and level of competition. Often markets research is based on existing (secondary) data compiled by government and industry sources such as census figures, the retail price index and the value of certain imported goods. It may also use journal and newspaper articles to build up a picture of competitors.

Marketing Research:

Marketing research focuses upon the information that will be useful to organisations who wish to sell specific products. It is the research which, say, the brand manager for Coca-Cola would use to devise a campaign to increase Coca-Cola’s market share. While marketing research has some overlap with research on markets, its focus is narrower and it is closer to the actual point of sale. Marketing research can, perhaps, the best considered under two headings- its uses and its methods.

Uses of Marketing Research:

Marketing research can play a vital role in bringing to market a product that is valued by customers and which is presented to them in an enjoyable way.

Marketing research’s main uses include:

(a) Product generation – marketing research can be used to identify new products. These ideas can be obtained by listening to consumers or by holding brainstorming sessions with designers and marketing executives.

(b) Product improvement and embellishment – existing products can be improved or made more attractive. Again, the source of suggestions can be obtained from consumers or brainstorming sessions. Ideas may also be generated by examining competitors’ products or even products and services in other markets.

(c) Product testing and refinement – prototypes of products and services can be tested on small groups of consumers. Their reactions and comments are usually incorporated in a modified product.

(d) Consumer targeting – marketing research can help pinpoint the people who are most likely to buy the product or use a service.

(e) Sales forecasting.

(f) Packaging and advertising design – various suggestions for packaging can be tested out on samples of consumers and the most effective packages or adverts chosen.

(g) Point-of-sale displays and procedures – marketing research can be used to develop and then refine point of sale displays, brochures and other factors that might influence the experience of a buyer.

Market – Structure (With Classification and Types)

A market refers to a suitable arrangement in which the buyers and sellers could closely interact (physically or otherwise) to arrive at exchange decisions. The demand and supply forces meet in the market to allocate resources. On one hand, firms compete for the scarce resources in order to produce and on the other, consumers compete in the market for their demands.

Market structure refers to the relationship between buyers and sellers, the forms of competition among the firms in the same industry, and the special features of a market in affecting the demand and supply forces. Markets are classified, broadly, depending upon the importance of an individual firm in relation to the entire market and whether products placed in the market are homogenous or not.

Using these two broad criteria, markets are classified into four broad categories—pure competition, pure monopoly, oligopoly, and monopolistic competition. In reality, markets may not fit into any one of these categories; they may be a mixture of two or more types of markets or it may have characteristics close to one of these categories.

However, an understanding of the broad classifications of markets provides a framework for analysing the demand curve faced by a firm or a business entity.

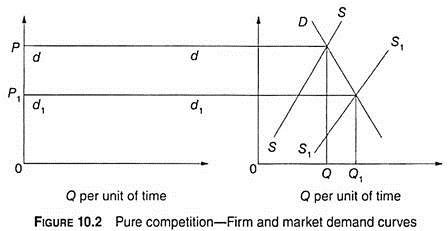

Classification # 1. Pure Competition:

In this market model there are a large number of firms having a homogenous or standardized product. Firms can enter or exit easily and have perfect knowledge about the markets.

In brief, the important characteristics of such a market are:

i. Very large numbers of buyers and sellers;

ii. Standardized product similar in all respects being produced by each firm;

iii. ‘Price takers’—firms accept the price as given;

iv. Free entry and exit for sellers; and

v. Perfect knowledge about the market.

Thus, if one or few firms quit the market, supply does not decrease enough to cause a change in the market price as no seller is big enough to influence it. The market price is determined by the forces of demand and supply operating in the market. Buyers and sellers have to accept the market price as given and are called price-takers.

They have complete information about the price, quality, and quantity sold in the market. As a result, there is no role for advertisement in such a market condition. Agricultural markets for wheat, sugar, rice; grocery stores of similar size; restaurants, etc. are examples of markets operating in pure competition.

Demand Curve:

The demand curve faced by sellers is horizontal at the prevailing equilibrium price. It is said to be perfectly elastic, that is, at the given price, sellers can sell all that they have to offer. However, at any price above the market equilibrium price, firms would not be in a position to sell any quantity. They can sell all they want to sell at the going market price.

In case of a firm operating under pure competition, it has to adjust itself to the market prices as given. If market supply increases resulting in a decrease in the price to P1, the demand curve faced by the firm would shift downward to d1d1 (Fig. 10.2). The firm has to just adjust itself to the given reduced price and adjust its output accordingly.

Normal Profit:

A perfectly competitive industry would be in equilibrium when each and every individual firm in the industry is in equilibrium, that is, each firm maximizes its profit by equating marginal revenue with marginal cost and the industry, as a whole, is in equilibrium. It means that no firm enters or leaves the market.

This happens when every entrepreneur in the industry earns normal profit—gains that are sufficient to sustain the seller in the industry. Thus, if in the industry, profits of all entrepreneurs rise above ‘normal’, then new firms will be encouraged to enter the industry leading to an extra supply and reduction in the prices.

This will lead to a new equilibrium price at which, again, every entrepreneur will just earn normal profits. Similarly, in case profits for everyone fall below ‘normal’, some firms will quit the market, decreasing supply, leading to an increase in prices. This will set a new equilibrium price at which all entrepreneurs will just earn normal profits.

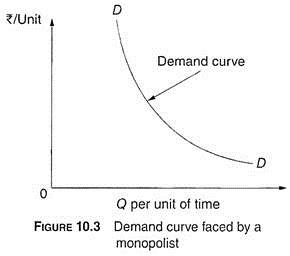

Classification # 2. Pure Monopoly:

Pure monopoly operates in a market when a single firm is the sole producer of a product for which there are no close substitutes. There are no similar products in the market whose prices or sales can influence, the monopolist’s price or sales substantially and vice versa.

Thus, cross elasticity of demand for the monopolist’s product is either zero or negligible. Neither does he expect a reaction from other firms nor do the actions of other firms in the market affect them. A monopolist is the only industry for the product that he produces. He may or may not engage in non-price competition.

Depending on the nature of its product, a monopolist may advertise to increase demand. However, he may not indulge in aggressive marketing, as he faces no competitors in the market. There are a number of products where the producers have a substantial amount of monopoly power and are called ‘near’ monopolies.

Examples of pure monopolies are public utilities such as gas, electricity, water, and railways. Western Union’s money transfer facility and the De Beers’s diamond syndicate are examples of ‘near’ monopolies. Monopolies can also be geographic in nature; for example, a small town may have only one bank branch or a single bus service.

Barriers to Entry:

Economies of scale have one major barrier—in case a production requires a massive investment and a large firm with a large market share already exists, new firms cannot afford to start industries with economies of scale. Public utilities have natural monopolies as they have economies of scale; where one firm is the most efficient in satisfying existing demand.

The government usually gives one firm the right to operate a public utility industry in exchange for government regulation of its power. Further, there can be legal barriers for entry in the form of patents and licenses.

Demand Curve:

The market demand curve would be a demand curve for the monopolist (Fig. 10.3). Since he is the only seller of the product in the market, he can sell exactly the quantity that buyers would buy at a given price.

Being alone in the market, a monopolist is able to exert some amount of influence on the price, output, and demand for the product. A monopolist can increase sales by lowering the price and restrict them by increasing the price, according to market demand. It can change its demand curve by using promotional tactics such as selective price-cutting and advertising.

A monopolist can effectively operate on price discrimination strategies that is charging different prices from different buyers for the same product, provided it can segregate the market by dividing the buyers into separate categories according to their ability or willingness to pay for the product (usually based on differing elasticities of demand).

The basic condition for effectively operating on price discrimination strategy is that buyers must be unable to resell the original product or service to derive price advantage.

Examples of effective price discrimination are airline companies charging high fares from executive travellers (inelastic demand) than vacation travellers (elastic demand); power companies that frequently segment their markets according to their end uses, such as lighting and heating, commercial users, and agriculture purposes (lack of substitutes for lighting makes this demand inelastic).

Classification # 3. Oligopoly:

In an oligopoly market situation, there are few sellers and the decision of one affects the other because of the sellers’ small size. Thus, changes in the output and price of one firm affect the price and the quantities that another firm would be able to sell in the market. Individual sellers in an oligopoly market are interdependent and not independent.

Each of the players in the market has to be very receptive to its competitor’s actions. Their goods may be homogeneous or heterogeneous. There are some barriers for entry into this industry arising on account of patents, high set-up cost, or specialized technology.

As a result, knowledge and information about each other’s operations is imperfect. Sellers in an oligopoly market usually turn to advertising to improve their sales. Some examples of oligopolies are banks, automotive manufacturers, gas companies, insurance companies, telecommunications companies, etc.

Oligopoly markets are normally classified into two broad categories—pure oligopoly and differentiated oligopoly. In a pure oligopoly market, firms produce homogeneous products while in a differentiated oligopoly market, firms produce and sell differentiated products.

Although these products are close substitutes to each other and have a high cross elasticity of demand, each firm’s product has its own unique characteristics to distinguish it from the other in terms of quality, design, packaging, size, etc. A market structure characterized by two producers is a specialized form of oligopoly, referred to as duopoly.

Demand Curve:

The interdependence of sellers in an oligopoly market makes it difficult to estimate the demand for each firm. The demand for a firm’s products cannot be determined if the firm is unable to predict the reactions of its competitors to changes in its price and output decisions.

However, if the firm can predict the reaction of its competitors with some accuracy, the demand curve for the firm can be estimated and would be correspondingly more determinate.

An oligopolistic firm is in a position to influence its demand curve to some extent and, consequentially, its price and output. An oligopolist can shift its demand curve upwards with the help of advertising and other promotional efforts to induce consumers to disassociate from its rivals and switch to its brand.

However, the firm’s rivals would also be ready with their moves to counter it. Ultimately, firms that succeed in their strategies of advertising campaign or other promotional measures would succeed in increasing the demand for their brands. Whether the firm faces a determinate or an indeterminate demand curve, it knows when it faces a downward sloping demand curve.

It can increase its sales by reduction in the price of the product, unless the objective is achieved through upward shift in the demand curve. Generally, the elasticity of demand faced by an oligopolist would be elastic because of the availability of good substitutes. However, elasticity of demand depends on the rival’s reactions to the price and output changes of the single seller.

Classification # 4. Monopolistic Competition:

Monopolistic competition is a market situation wherein there are many sellers of a particular product that are differentiated in some way or the other. Like those in a pure competitive market, each seller is too small to influence the decision of the other. The relationship between different sellers is impersonal.

The products get differentiated by brand name, quality, trademarks, post-sale service, packaging, etc. The cross elasticities of demand are high as though differentiated, and the products are good substitutes of each other. Enterprises that fall under monopolistic competition include beauty clinics, hosiery items, service trades, textile products, etc.

For example, there are many beauty clinics in the country and a majority of them are small. The entry is free and people know enough about their hairdressing options, that is, ‘sufficient knowledge’ is available to the buyers. However, the products of different beauty clinics are differentiated in some way or other and, therefore, are not perfect substitutes.

The difference between monopolistic competition and perfect competition is that in monopolistic competition, production does not take place at the lowest possible cost. Due to this, firms are left with excess production capacity. Chamberlin (1946) and Robinson (1933) developed this market concept.

Demand Curve:

The demand curve faced by the firm has typical basis because of differentiation of products. The demand faced by a firm in a pure competition, wherein products are homogenous, is perfectly elastic. The differentiation makes the consumers attached to the brand and, therefore, the demand curve becomes somewhat elastic from perfectly elastic.

It implies that consumers would continue to purchase a product from a particular firm even if there is some degree of variation in the price, but beyond a point they would switchover to another product which is a close substitute. Thus, a firm operating in the monopolistic competition attempts to have a relatively less elastic demand by differentiating its products and creating a niche for its products in the market.

In monopolistic competition, firms may enjoy economic gains, that is, profits over and above normal profits. However, because of free entry (as in pure competition), economic profits will be zero in the long run. As long as there are positive economic profits, there will be new entrants into the industry leading to a squeeze in the economic profits.

Therefore, positive economic profits will not be stable in a monopolistically competitive industry. However, some economists believe that a monopolistically competitive industry may have high prices because non-price competition raises costs.

The individual firms in monopolistic competitive markets may be in a position to influence the demand and price of its product to some degree through advertising. However, their influence is limited because of availability of good substitutes in the market.

Although a firm in a monopolistic competitive market faces a situation similar to that of a firm in a perfectly competitive market, it operates to some extent like a monopoly, as it has some control over its prices and output. However, if a firm raises the prices of its products beyond a certain tolerable limit, it loses all its customers.

At the same time, it does not have to bring its prices too low to secure all the customers it can handle. So, outside a given price range, the firm operates under the forces of pure competition.

Types of Market Structure

A market consists of groups of buyers and sellers. The most common feature among all buyers and all sellers is that they are very different. Though they share some common characteristics they can be divided into some distinct groups, which are different among themselves in terms of nature and size of market, nature and size of purchase, purpose of purchase, etc. We can study four different types of Markets.

They are:

1. Consumer market,

2. Business market,

3. Government market,

4. Institutional market.

Type # 1. Consumer Markets:

It is a very wide market. It consists of the all the people who have some unsatisfied demand. The number of buyers is large in number. But since the purchases done by them are for the personal consumption and not to utilize it for selling or further production, individuals buy in small quantities. Because of the large number of consumers there is no close relationship between them and the manufacturer. Along with the large numbers the buyers as widely distributed also.

The entire world is consumer market. As there is large number of buyers and as these buyers are geographically widespread, there are a large number of middlemen the distribution channel. The purchase is small in quantity and the consumers have many alternatives to choose from. So they are very sensitive to price change. The demand in the consumer market is price elastic.

Type # 2. Business Markets:

The business market consists of all the organizations that acquire goods and services used in the production of other products or services that are sold, rented, or supplied to others. Thus, the business market do not purchase for personal consumption.

These can be of two types:

(i) Industrial Markets:

Here, the major criterion is keeping production satisfied in order to that materials and components are available for incorporation in production process. The ultimate objective is to satisfy the needs of the company’s customers, be they intermediate manufacturers further down the production chain or end customers.

(ii) Resale Markets:

This is the case where the principal criterion is the mark-up percentage that can be added to goods that are purchased from manufacturers and wholesalers in bulk and then resold to individual customers.

Type # 3. Government Markets:

In most countries, government organizations are a major buyer of goods and services. Especially in the developing country like India, where the major infrastructural projects and production are government undertakings, government markets become a very important part. The government unit will make allowance for suppliers’ superior quality or reputation for completing contracts on time.

They tend to favor domestic suppliers over foreign suppliers. Government organizations require considerable paper work from suppliers. Hence there is a delay in decision-making due to excessive paper work and bureaucracy. There are too many regulations to be followed. There is red- tapism in government market. They, purchase in large quantities. Cost or price plays a very major role. Product differentiation advertising and personal selling have less consequence in winning bids.

Type # 4. Institutional Markets:

Institutional market consists of schools, hospitals, nursing homes, prisons and other institutions that must provide goods and services to people in their care. Many of these organizations are characterized by low budgets and captive clienteles.

For example, hospitals have to decide what quality of food to buy the patients. The buying objective here is not profit, because the food is provided to the patients as part of the total service package; nor is cost minimization the sale objective because poor food will cause patients to complain and hurt the hospital s reputation.

The hospital’s purchasing agent has to search for institutional food vendors whose quality meets or exceeds a certain minimum standard and whose prices are low. In fact, many food vendors set up separate division to sell to institutional buyers.

Similarly in case of a bank the stationeries for the forms and dockets are purchased not with a profit motive but as a part of the service package offered.

Market – 4 Main Types of Consumer Market

Consumer markets are the markets for products and services like Car, LED TV, Refrigerators, Toothpaste, Ice Cream, Apparels, Air travel etc., bought by individuals for their own or family use. In the consumer market, companies try to identify and meet the needs of the consumer through their product and service offering.

Additionally, they try to position the products into the consumers mind for better awareness and purchases.

Consumer markets can be classified in the following way:

1. Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG):

Fast Moving Consumer Goods widely known as FMCG, generally include a wide variety of frequently purchased products such as toothpaste, shampoo, soap, cosmetics, hair oil and detergents, as well as other non- durables such as plastic goods, CFL bulbs, paper & stationery and glassware. FMCG may also include chocolates, pharmaceuticals, packaged food products and soft drinks.

These goods are of low unit value with high volume potential and require frequent repurchase. In 2013, the market size was Rs. 2.2 lakh-crore in India. The top 10 companies in the FMCG sector are Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL), ITC, Nestle India, Amul, Dabur, Asian Paints, Cadbury India, Britannia Industries, Procter & Gamble and Marico Industries. Other leading companies in this segment are Reckitt Benckiser, GlaxoSmithKline, Pepsi, Coke, Himalaya, Bajaj, Godrej etc.

Now there is a new subset of FMCG called Fast Moving Consumer Electronics (FMCE), which include innovative electronic products like MP3 players, mobile phones and digital cameras. These are replaced more frequently than other electronic products.

2. Consumer Durables:

On the contrary, Consumer durables are low volume products with high per unit value. It is also known as White Goods or Brown Goods. White goods include Refrigerators, Freezers, Washing Machines, Dishwashers, and Microwaves etc; while Brown goods include TVs, DVD players, Home Theatres, Camcorders, Game consoles like Microsoft ZBox 360, Sony Playstation, Nintendo WI, personal computers etc.

When the goods are not classified as White goods or brown goods, then it is called white goods on the whole, which also includes household electronics items, earlier categorised under brown goods.

3. Soft Goods:

Soft goods are relatively priced higher than the FMCGs and lesser than the consumer durables. These goods are also low volume in nature, as it requires a shorter replacement cycle. For examples – Clothing Material, Apparels, Shoes etc.

4. Yellow Goods:

Besides white and brown goods, there is another not so popular classification of Yellow Goods. Yellow Goods include material for construction and earth moving equipment, fork lift trucks and quarrying equipment. The term is also used for agricultural equipment like tractors.

Services:

Beside the goods, consumer markets also require a lot of services. Goods are physical, tangible articles, while Services are nonphysical and intangible in nature. Services can also satisfy a need like goods. Financial services, Banking, Telecom, DTH, Courier, Hotel, Airline, Multiplex, Train, Doctors, Lawyers, Healthcare and Management Consultancy are all examples of services.

Services require an additional set of marketing mix tools than the goods market like people, process and physical evidence, besides the 4Ps – product, price, place and promotion.

Market – 2 Important Methods for Estimating Area Market Demand

1. Market Build-Up Method:

The market build-up method requires identifying all the potential buyers in each market and estimating their potential purchases. Suppose a manufacturer of mining instruments invented an instrument for assessing the gold content in gold-bearing ores. The instrument can be used in the field to test gold ore. With the help of it miners would not waste their time digging deposits of ore containing too little gold to be commercially profitable.

Each mine would buy one or more such instrument depending on the mine’s size. The company wants to determine the market potential for this instrument in each mining area and whether to hire a sales person to cover that area. The company would place a salesperson in each area that has a market potential of Rs.5,00,000.

2. Market Factor-Index Method:

Consumer goods companies have to estimate area market potentials starting with Calcutta market. Think of a manufacturer of T-shirts who wishes to evaluate its sales performance relative to market potential in several major market areas. It has estimated total national potential for T-shirts at Rs. 1 crore per year.

The company’s current nationwide sales are about 10% of the total potential market. The company wants to know whether its share of Calcutta market is higher or lower than 10% of market share. To find out this the company has to calculate the market potential in the Calcutta market.

A common method for calculating area market potential is to identify market factors that correlate with market potential and combine them into a weighted index. An example of this method is called the buying power index. The buying power index is based on three factors —the areas of the nation’s disposable personal income, retail sales and population.

Estimating Actual Sales and Market Shares:

Besides estimating total and area demand a company has to know the actual industry sales in its market. Thus it must identify its competitors and estimate their sales. The industry’s trade association often collect and publish total industry sales but it does not list individual company sales separately. In this way, each company can evaluate its performance against the industry as a whole. Suppose the company’s sales are increasing at 12%. This company actually is losing its relative position in the industry.

Market – 10 Main Entities which can be Marketed

A marketer does not only market goods and services, but he or she also markets eight other entities like Events, Experiences, Persons, Places, Properties, Organisations, Information and Ideas.

The ten entities, which can be marketed are as follows:

1. Goods:

Goods are physical, tangible articles, which can satisfy a need. All across the world, most of the country is engaged in manufacturing and producing goods like Toothpaste, Washing Powder, Cosmetics, Cars, Petrol etc.

Now, goods are not only marketed by companies, but also by individuals. In the era of Internet Marketing, individuals can also sell goods through the Internet. In India, you have got websites like www(dot)ebay(dot)in, www(dot)olx(dot)in to sell your products online. Besides these websites, goods can also be sold and bought through shopping sites like www(dot)flipkart(dot)come, www(dot)snapdeal(dot)com, www(dot)amazon(dot)in, www(dot)infibeam(dot)com, www(dot)homeshop18(dot)com, etc.

2. Services:

Services are non-physical and intangible in nature and can satisfy a need. Banking, Courier, Hotel, Airline, Multiplex, Train, Doctors, Lawyers, Management Consultants are all examples of services. With the advancement in the economy, a country moves from a good producing country to a service oriented country. For example, USA, which is one of the most developed countries in the world, is having a 70% – 30% mix of goods and services.

But some services are inclusive of product, like the restaurant, where a customer gets a tangible good in the form of say a masala dosa and gets it served at his table. In the other case, a service like mobile is backed by huge investments in equipments.

In the study of marketing all the ten entities, which can be marketed, are generally clubbed together as goods and services.

3. Experiences:

Experiences can be also marketed with the usage of goods, services and with a dose of technology. India’s first amusement park in Delhi – Appu Ghar, Essel World in Mumbai, and Disney Land in USA and Sentosa Island in Singapore are examples of experiences, which needs to be marketed.

4. Events:

Events like ICC Cricket World Cup 2015, FIFA World Cup Brazil 2014, Shahrukh Khan’s Temptation World Tour in 2009, Commonwealth Games in Delhi in 2010, Olympics, Asian Games, T20 World Cup, Wimbledon, Shakira’s Concerts etc. needs marketing to get the audience and spectators.

5. Persons:

Peter Montoya’s book ‘The Brand called You’ and Tom Peters’ advise to each person to become a brand, says a lot about the marketing of a person. For example, Mahendra Singh Dhoni, the captain of Indian Cricket Team, earned $10 million (Rs 48 Crore) in 2008 and became the world’s richest cricketer; followed by Sachin Tendulkar with $8 million (Rs 38.5 Crore). In 2007, the highest earning celebrity in the world was Oprah Winfrey with an earnings of $260 million. Other celebrities are also not far behind with Filmmaker Steven Spielberg earning $110 million, Sportsman Tiger Woods earning $100 million and Actor Johnny Depp earning $92 million.

All these celebrities are marketed by an agent or a personal manager or by a talent management company like Percept Talent Management; which manages Celebrities like Amitabh Bachchan, Shah Rukh Khan, Katrina Kaif, Aamir Khan, Priyanka Chopra, Yuvraj Singh, A. R. Rahman, Shekhar Suman besides others.

6. Places:

Incredible India, Kerala- The God’s Own Country, and Malaysia- Truly Asia, are different advertising campaigns to attract tourist to these places. Places are marketed to bring more tourists, residents, factories and offices. Tourism boards, real estate companies, advertising and promotional agencies and public relations organizations generally market the places.

7. Properties:

Properties including real estate properties and financial properties, both need to be marketed. Every Saturday, The Times of India comes out with a supplement called Times Property for the real estate properties to be marketed; while Hindustan Times comes out with HT Estates on the same day.

Companies like DLF, HDIL, Omaxe, Rahejas, Unitech etc. are real estate companies, who regularly market their real estate properties. Financial properties like shares, bonds, debentures, mutual funds etc. also need to be marketed to the individual as well as institutional investors.

8. Organisations:

Life is Good (LG), let us make things better (Philips), Experience Change (Videocon), Count on us (Maruti Suzuki) etc. are examples of fortifying the image of the company in the mind of its target publics. Even social organisations like CRY (Child Relief and You) also market themselves to gain visibility and attract funds.

9. Information:

Encyclopedia Britannica, Manorama Year Book, Penguin CNBC TV18 Business Year Book, Magazines like Overdrive, Smart Photography, Digit, Business World, Screen, Filmfare, Femina; and DVDs / CDs like Budget Demystified, Being Business Leaders are examples of how information is marketed. Schools, Colleges, Institutes and Universities also produce and market information to the students and their guardians.

10. Ideas:

‘An idea can change your life’ – the famous baseline of Idea Cellular fits correctly as far as marketing of ideas is concerned. Ideas like Condom ‘Bindaas Bol’ campaign, Oral Contraceptives ‘Goli Ke Jamjoli’ campaign, ‘Pulse Polio’ campaign, NACO campaign to spread awareness against AIDS etc. effectively market the social concerns by their respective bodies like USAID, Child and Reproductive health, Health ministry, Govt. of India and National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO).

Market – Benefits of External Market Access

The starting up of international activities is not only problems for the small and medium-sized enterprise. World market penetration has a series of actual benefits of different kinds (related to tax burden, customs, credits, etc.), which, in some cases, local entrepreneurs ignore.

1. Customs Benefits:

As regards customs advantages, most exports are benefited by a series of state stimula. The best known national incentives are tax refunds and drawbacks. They provide the reimbursement of internal taxes paid at each productive stage (in the case of tax refunds) and taxation corresponding to products imported by the company (in the case of drawbacks) that may affect exported product price.

Besides, each country has customs regulations that benefit international operations like- import and export temporary system, delivery in consignment, export on behalf of third parties, and use of free trade areas, among others.

2. Credit Benefits:

As regards the credit issue, there are special lines for exporters, granted by the main official and private banks. These credits are called pre-financing or financing export credits, and have more beneficial terms and rates than those assigned for domestic activity credits.

3. Tax Benefits:

From the taxation point of view, unlike sales made in the internal market, exports do not have to pay most of the main taxes like- Value Added Tax (VAT), Stamp Taxes,

Internal taxation, etc. Besides, as regards VAT, generally, exporting companies may—as regards tax paid in purchases and expenses—credit it, compensate with sales in the internal market, ask for a refund or transference.

The purpose of most States is to exempt international operations from domestic market operations taxes. Thus, the producer may form more competitive exportation prices without “exporting taxes”. There is a generally accepted principle in international marketing- “taxation in the country of destination”. The aim is to exempt exports from most taxes in the country of origin, so that the countries of destination could be the ones to tax the goods, through import operations.

4. Image Benefits:

The startup and consolidation of the small and medium enterprise international operations allow to generate a better company image. This affects the firm positioning in the external market. The internationalized enterprise assumes commitments in the different world markets and may supply the different requirements they make. This attitude gives the entrepreneur a higher status among the organizations in that sector and gives the company a position of prestige.

Besides, continuous contact with international operators, improves company’s image and symbol communication to the consumers, the competitors, and society in general. The internationalized company’s activities are positively perceived, especially world markets obstacle overcoming and responsibility and reliability in its management to assume commitments of great international importance and comply with them.

5. Market Diversification Benefits:

Another important incentive achieved by the exporting company comes from operation risk diversification between national and external markets. This issue may be more important when, due to national market crisis or economic recession, international scenarios are penetrated.

A national market with recession or economic depression makes entrepreneurs who have not gained access to world markets constantly affected by a decrease in sales and generates a productive capacity surplus.

A similar situation appears in those national markets in which there is a strong competitive environment which prevents the company from getting more participation in the domestic market. The same happens in saturated markets, in which the product is in its maturity or declination stage.

Every aspect described reinforces the importance that exportation has for small and medium- sized enterprises. The entrepreneur will be able to evaluate the possibility of penetrating other markets more interesting from the purchasing power point of view, with a greater number of consumers, or less saturated.

The organization will have to look for those environments with a lesser number of competitors than the domestic markets, or those country markets with different lifecycles for their product.

When external operations are developed, all the efforts and resources are not concentrated on the national market, and, in this way, the effects of internal market instability that may affect the business are diminished.

6. Benefits of Increase in Commercialized Volumes:

Certain price and quality competitiveness advantages can be obtained when products are internationally marketed. Besides, by getting an increase in earnings, exporting companies get other benefits. One of them is a better distribution of some fixed costs as a consequence of an increase in total sales that generates a greater production volume.

In this way more reduced fixed unitary costs and more competitive prices are accomplished (through economies of scale, economies of marketing and economies of R + D).

Besides, internationalization may solve problems of company idle capacity. The implementation of an international strategy allows to reach a greater production quality, because of the constant contact with other stricter cultures and with world environment competitors. Processes and product design are improved as international exposure is increased.

7. Benefits of Differentiation:

It is possible to discover that a particular product, in certain external markets, appears as a totally differentiated product from the rest. This situation may turn it into “unique”, be it for its technological advantages, design or provisions included. It may happen that a product is not very well-known in some markets or little used and consumed, as a result of being in the first stages of its lifecycle (for example, product introduction stage).

This issue may incentive penetration in that country-market with the company products. It should be verified that differential issues perceived upon certain attributes (quality, design, technology, costs, etc.) of a particular market product are about real differences and not erroneous perceptions.

8. Benefits of Exclusive Information:

An important factor that boosts exportation is the access to exclusive information about business opportunities in the world markets. These data may come from trade shows attendance, market informal studies, business trips or other means. They may be about specific orders from a particular country, about a specific product, or data concerning potential buyers. These elements represent an important advantage for the entrepreneur who possesses them, until they reach competitors’ hands.

9. Benefits of Associativity:

When an export company strategy is used through different joint structures (like consortia, cooperatives, etc.), the enterprise may hire technical personnel specially qualified in different international activities (market studies, international quality certifications, trade shows attendance, etc.). Without taking part in those associations it would be very difficult to pay for those expenses individually.

Besides, synergy (consistent union of forces) among the different exporting partners of the project is produced, which allows to get better negotiating conditions with the international marketing different operators and auxiliaries (clients, suppliers, carriers, customs agents, etc.). Each member is contained by a company structure of cooperation in the international access stages.

In some cases, some enterprises opt to export by imitating their competitors’ attitude because they have already internationalized. Thus, they try not to be left aside from the relative advantages of the international marketing enjoyed by International Marketing the competition. However, in some countries, especially in the developing countries, the presence of small-sized companies in the international environment continues being absolutely limited.

It is important to reflect on the relevance of international markets and the advantages of positioning, in order to adopt a positive attitude to internationalization. The assumption of external commitment has to be gradual and decisions must be adopted beyond the present state of affairs that may affect companies.

Entrepreneurial attitude must not be based on the marketing of balances not sold in the internal market (exportable balance). There has to be a strategy to allow the exportation of stable and continuous volumes (exportable offer), to generate lasting commercial relationships with customers abroad.

Market Survey

Meaning of Market Survey:

Small firms are over and over again reluctant to invest in market research exercise as it seems to be an expensive proportion. Moreover, it is a time-taking process, and an entrepreneurial business enterprise is usually in urgency.

Many entrepreneurial ventures take a middle path and decide to undertake market research when there is a big decision to be taken. This is not necessarily the right approach. The question of when to resort to market research can be answered by a cost-benefit analysis.

The costs of doing market research are the direct expenses of doing research as well as the likely loss in sales due to delaying decision. A delay in the decision caused by waiting for the results of the market research can give an opportunity to competitors to capture market share at your cost.

Market research is not to be confused with field survey. Afield survey is just one of the techniques used in market research. Any dependable information that improves the marketing decision is market research.

What is a Market Survey?

The firm market survey is used by some as synonymous with market research or market analysis. This is incorrect. Market survey is only a technique or method of market research or market analysis. Its purpose is to collect specific data concerning the market that cannot be had from the company’s internal records or from external published sources of data.

When a market survey is used for generating relevant market information and such information forms the basis of the sales forecasts, the forecasting method is referred to as the market survey method of sales forecasting.

Why Need Market Survey?

Normally, when an enterprise wants to introduce a new product or an improved product, it resorts to a market survey to assess the likely demand for the product. Marketing a new product is not an easy job and a novice can very easily be thrown out by other competitors.

To chalk out a programme for marketing a new product is therefore, necessary. A new article is one which has not been previously marketed by any other business concern, e.g., new drink, new toilet soap, new hair oil, new type of cloth and a new machine, etc.

Whereas a new brand is simply a competitor among other products of that type already available on the market. For a new brand it is necessary to find out merely whether the market is being adequately served or whether there is room for another brand. For a new product it is necessary to find out whether a market does exist and if it does not, whether it is possible to create a market for the product. Likewise, any new enterprise entering the market for the first time, resort to the market survey method for forecasting its demand/sales.

This is quite natural. The enterprise does not have any data of past sales demand patterns to fall back upon. It has to gather the information from the market and take decisions. Usually, the enterprise conducts a survey among a sample of consumers and gauges their attitude, likely purchase, purchase habits, etc. The merit of the market survey method lies in the fact that the method facilitates gathering of original or primary data, i.e., specific to the problem on hand. The main demerit is that it is time- consuming and expensive.

Techniques of Market Survey:

Usually the following techniques are used to collect factual data, less so when used to gain insight into respondent’s interpretations.

The market survey techniques may be of the following types:

1. Product-Oriented:

A product needs proper planning by the entrepreneur before its introduction in the market. The purpose is to offer better service and satisfaction to customers. Today’s marketing firms are selling product’s benefits and image rather than the product itself.

Product-oriented survey techniques help in gathering essential facts about the product.

It entails finding answers to the following:

(i) What fundamental human instincts does the use or consumption of the product satisfy?

(ii) What interests and desires does it appeal to?

(iii) How well does it meet the requirement of the user or consumer?

(iv) Can any improvements or modifications be made which would strengthen its appeal?

(v) Are there any use for it not hither to thought of?

(vi) What are its selling points?

(vii) What should be the unit or unit of sale?

Even while selecting the methods of marketing and the channels of distribution the following question certainly will do an impressive job:

(i) Will it be better to employ salesmen alone?

(ii) Should it use advertising alone?

(iii) To use a combination?

(iv) What subsidiary forms of selling should be used?

(v) What will be the relative costs of marketing by these methods?

(vi) Should the product be sold to the consumer or user through the manufacturer’s organisation?

(vii) Through retailers?

(viii) Would the employment of wholesalers be advantageous?

(ix) What would be the benefits of using special selling agents?

(x) What are the relative costs and net profits likely to be as a result of using each of these methods?

2. Market-Oriented:

Now, the customers were not ready to buy whatever was offered to them by the entrepreneurs. They started to buy the goods or service that was more beneficial to them in terms of quality, price, satisfaction, durability, look and soon. Therefore, the entrepreneurs were compelled to produce what the customers want.

An entrepreneur should seek answer to the following raised questions in order to have strong standing in the market:

(i) Who are its logical consumers?

(ii) Who are its marginal consumers?

(iii) Where are they to be found?

(iv) Who are its logical distributors?

Expected Investigation:

(i) What type of investigation will suit the product?

(ii) By whom will it be conducted?

(iii) Exactly what information should be sought for?

(iv) What size of sample should be considered as sufficiently indicative?

(v) Are there any existing product which might give some indication of size of the market and volume of sales to be expected?

(vi) How should the product be packed?

(vii) What prices should it be sold?

(viii) What terms would be most satisfactory to dealers and manufacturers?

(ix) What class of dealers should handle the product?

3. Desk Research:

The terms ‘Desk Research’ denotes all marketing researches done by a marketing expert/entrepreneur with the help of published and other written sources of information. It is a table work involving the analysis of data available in directories, journals and magazines and in the internal records of the firms such as final statements, sales reports and so on.

Advantages:

(i) Information is available without much effort.

(ii) The method is least expensive.

(iii) The data are free from investigator’s bias.

(iv) It keeps the marketing manager free from botheration of field investigation.

(v) The data available from government, stock exchange, chamber of commerce and industry and other organized bodies is also reliable to a great extent.

Disadvantages:

(i) This is based on secondary data, therefore limitations of secondary data is involved in them.

(ii) Published information will have to be modified to meet the requirement of the entrepreneur/ researcher before using it.

(iii) It is less reliable and results are doubtful unless tested by field investigation.

4. Field Investigation:

Field investigation is a very reliable technique as it is based on primary data collected directly by the researcher/entrepreneur from the field. Sometimes, the primary data is supplemented with secondary or published data too.

There are three field research techniques:

(a) Mail Order Surveys:

A mail order survey is a complete antithesis of the personal interviews. Under this method, a questionnaire which is sent to him by mail is completed by informant completely unaided and unguided. Under this method, the questionnaire should be carefully compiled, structured and pre-tested, as it will have to be filled in by the informant himself.

The names and addresses of people to whom questionnaire are sent by post are obtained by various means. There are agencies which specialize in providing list of different kinds of people such as lawyers, doctors, engineers, government officers, professors and so forth. The simplest list is of course the telephone directory. But it cannot be an exhaustive list.

(b) Telephone Surveys:

Telephone interviewing is the second type of field research. This technique has been used in particular for the estimation of the number of persons who have just finished watching a television programme or listening to a radio broadcast. This is also used to estimate quickly to ascertain the ownership of different types of product. Though this method is very convenient for industrial surveys, it is not widely used in this country.

(c) Personal Interviews:

The third technique of field investigation is personal interviewing. Under this technique, the interviewer follows a rigid procedure in asking question in prescribed form and order. A structured questionnaire is prepared and the interviewer fills it on the basis of answers supplied by the informant. The interviewer may, however, be allowed varying degrees of freedom in conducting the interview.

The greater the freedom allowed, the higher is the skill required in the interviewer and the more complex are the problems of analysis of the results. These interviews may be of various type-structured, semi-structured, unstructured, the free interview, the focus interview, depth interview and so on. Every type of interview has its own merits and demerits. Interviewing method is quite popular in conducting marketing researches in India and abroad.

5. The Delphi Technique:

The Delphi Technique was originally conceived as a way to obtain the opinion of experts without necessarily bringing them together face to face. In recent times, however, it has taken on an all new meaning and purpose. The Delphi Technique is the method being used to squeeze citizens out of the process, affecting a left-wing takeover of the schools.

The change agent or facilitator goes through the motions of acting as an organizer, getting each person in the target group to elicit expression of their concerns about a program, project, or policy in question. The facilitator listens attentively, forms “task forces,” “urges everyone to make lists,” and so on. While she/he is doing this, the facilitator learns something about each member of the target group. She/he identifies the “leaders,” the loud mouths,” as well as those who frequently turn sides during the argument – the “weak or noncommittal”.

This technique is a very unethical method of achieving consensus on a controversial topic in group settings. It requires well-trained professionals who deliberately escalate tension among group members, pitting one faction against the other, so as to make one viewpoint appear ridiculous so the other becomes “sensible” whether such is warranted or not.

The Delphi technique is one more way of obtaining group input for ideas and problem-solving. Unlike the nominal group process, the Delphi does not require face to face participation. It uses a series of carefully designed questionnaires interspersed with information summaries and feedback from preceding responses.

In a planning situation, the Delphi can be used to:

i. Develop a number of alternatives;

ii. Assess the social and economic impacts of rapid community growth;

iii. Explore underlying assumptions or background information leading to different judgments;

iv. Seek out information on which agreement may later be generated;