Home

About

Blog

Contact Us

Log In

Sign Up

Follow Us

Our Apps

Home>Words that start with L>like

How to Say Like in Different LanguagesAdvertisement

Categories:

General

Please find below many ways to say like in different languages. This is the translation of the word «like» to over 100 other languages.

Saying like in European Languages

Saying like in Asian Languages

Saying like in Middle-Eastern Languages

Saying like in African Languages

Saying like in Austronesian Languages

Saying like in Other Foreign Languages

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

Saying Like in European Languages

| Language | Ways to say like | |

|---|---|---|

| Albanian | si | Edit |

| Basque | bezalako | Edit |

| Belarusian | як | Edit |

| Bosnian | poput | Edit |

| Bulgarian | като | Edit |

| Catalan | M’agrada | Edit |

| Corsican | cum’è | Edit |

| Croatian | kao | Edit |

| Czech | jako | Edit |

| Danish | synes godt om | Edit |

| Dutch | graag willen | Edit |

| Estonian | nagu | Edit |

| Finnish | Kuten | Edit |

| French | comme | Edit |

| Frisian | lykas | Edit |

| Galician | como | Edit |

| German | mögen | Edit |

| Greek | αρέσει [arései] |

Edit |

| Hungarian | mint | Edit |

| Icelandic | Eins og | Edit |

| Irish | cosúil le | Edit |

| Italian | piace | Edit |

| Latvian | tāpat | Edit |

| Lithuanian | Kaip | Edit |

| Luxembourgish | gär | Edit |

| Macedonian | допаѓа | Edit |

| Maltese | bħal | Edit |

| Norwegian | som | Edit |

| Polish | lubić | Edit |

| Portuguese | gostar | Edit |

| Romanian | ca | Edit |

| Russian | как [kak] |

Edit |

| Scots Gaelic | mar | Edit |

| Serbian | као [kao] |

Edit |

| Slovak | Ako | Edit |

| Slovenian | kot | Edit |

| Spanish | me gusta | Edit |

| Swedish | tycka om | Edit |

| Tatar | кебек | Edit |

| Ukrainian | люблю [lyublyu] |

Edit |

| Welsh | fel | Edit |

| Yiddish | ווי | Edit |

Saying Like in Asian Languages

| Language | Ways to say like | |

|---|---|---|

| Armenian | նման | Edit |

| Azerbaijani | kimi | Edit |

| Bengali | মত | Edit |

| Chinese Simplified | 喜欢 [xǐhuān] |

Edit |

| Chinese Traditional | 喜歡 [xǐhuān] |

Edit |

| Georgian | მოსწონს | Edit |

| Gujarati | જેમ | Edit |

| Hindi | पसंद | Edit |

| Hmong | zoo li | Edit |

| Japanese | 好きな | Edit |

| Kannada | ಹಾಗೆ | Edit |

| Kazakh | сияқты | Edit |

| Khmer | ដូច | Edit |

| Korean | 처럼 [cheoleom] |

Edit |

| Kyrgyz | сыяктуу | Edit |

| Lao | ຄື | Edit |

| Malayalam | പോലെ | Edit |

| Marathi | सारखे | Edit |

| Mongolian | шиг | Edit |

| Myanmar (Burmese) | ကဲ့သို့ | Edit |

| Nepali | जस्तै | Edit |

| Odia | ପରି | Edit |

| Pashto | خوښول | Edit |

| Punjabi | ਪਸੰਦ ਹੈ | Edit |

| Sindhi | پسند ڪريو | Edit |

| Sinhala | මෙන් | Edit |

| Tajik | мисли | Edit |

| Tamil | போன்ற | Edit |

| Telugu | వంటి | Edit |

| Thai | ชอบ | Edit |

| Turkish | sevmek | Edit |

| Turkmen | ýaly | Edit |

| Urdu | کی طرح | Edit |

| Uyghur | like | Edit |

| Uzbek | kabi | Edit |

| Vietnamese | như | Edit |

Too many ads and languages?

Sign up to remove ads and customize your list of languages

Sign Up

Saying Like in Middle-Eastern Languages

| Language | Ways to say like | |

|---|---|---|

| Arabic | مثل [mathal] |

Edit |

| Hebrew | כמו | Edit |

| Kurdish (Kurmanji) | çawa | Edit |

| Persian | پسندیدن | Edit |

Saying Like in African Languages

| Language | Ways to say like | |

|---|---|---|

| Afrikaans | soos | Edit |

| Amharic | እንደ | Edit |

| Chichewa | ngati | Edit |

| Hausa | kamar | Edit |

| Igbo | dị ka | Edit |

| Kinyarwanda | nka | Edit |

| Sesotho | joaloka | Edit |

| Shona | senge | Edit |

| Somali | sida | Edit |

| Swahili | kama | Edit |

| Xhosa | njenge | Edit |

| Yoruba | bi | Edit |

| Zulu | efana | Edit |

Saying Like in Austronesian Languages

| Language | Ways to say like | |

|---|---|---|

| Cebuano | sama sa | Edit |

| Filipino | gaya ng | Edit |

| Hawaiian | makemake | Edit |

| Indonesian | seperti | Edit |

| Javanese | seneng | Edit |

| Malagasy | toy ny | Edit |

| Malay | seperti | Edit |

| Maori | rite | Edit |

| Samoan | pei | Edit |

| Sundanese | siga | Edit |

Saying Like in Other Foreign Languages

| Language | Ways to say like | |

|---|---|---|

| Esperanto | Ŝati | Edit |

| Haitian Creole | tankou | Edit |

| Latin | tamquam | Edit |

Dictionary Entries near like

- lights out

- lightweight

- likable

- like

- like-minded

- likeable

- likelihood

Cite this Entry

«Like in Different Languages.» In Different Languages, https://www.indifferentlanguages.com/words/like. Accessed 13 Apr 2023.

Copy

Copied

Browse Words Alphabetically

How the ubiquitous, often-reviled word associated with young people and slackers represents the ever-changing English language

In our mouths or in print, in villages or in cities, in buildings or in caves, a language doesn’t sit still. It can’t. Language change has preceded apace even in places known for preserving a language in amber. You may have heard that Icelanders can still read the ancient sagas written almost a thousand years ago in Old Norse. It is true that written Icelandic is quite similar to Old Norse, but the spoken language is quite different—Old Norse speakers would sound a tad extraterrestrial to modern Icelanders. There have been assorted changes in the grammar, but language has moved on, on that distant isle as everywhere else.

It’s under this view of language—as something becoming rather than being, a film rather than a photo, in motion rather than at rest—that we should consider the way young people use (drum roll, please) like. So deeply reviled, so hard on the ears of so many, so new, and with such an air of the unfinished, of insecurity and even dimness, the new like is hard to, well, love. But it takes on a different aspect when you consider it within this context of language being ever-evolving.

Recommended Reading

First, let’s take like in just its traditional, accepted forms. Even in its dictionary definition, like is the product of stark changes in meaning that no one would ever guess. To an Old English speaker, the word that later became like was the word for, of all things, “body.” The word was lic, and lic was part of a word, gelic, that meant “with the body,” as in “with the body of,” which was a way of saying “similar to”—as in like. Gelic over time shortened to just lic, which became like. Of course, there were no days when these changes happened abruptly and became official. It was just that, step by step, the syllable lic, which to an Old English speaker meant “body,” came to mean, when uttered by people centuries later, “similar to”—and life went on.

Like has become a piece of grammar: It is the source of the suffix —ly. To the extent that slowly means “in a slow fashion,” as in “with the quality of slowness,” it is easy (and correct) to imagine that slowly began as “slow-like,” with like gradually wearing away into a —ly suffix. That historical process is especially clear in that there are still people who, colloquially, say slow-like, angry-like. Technically, like yielded two suffixes, because —ly is also used with adjectives, as in portly and saintly. Again, the pathway from saint-like to saint- ly is not hard to perceive.

Like has become a part of compounds. Likewise began as like plus a word, wise, which was different from the one meaning “smart when either a child or getting old.” This other wise meant “manner”: Likewise meant “similar in manner.” This wise disappeared as a word on its own, and so now we think of it as a suffix, as in clockwise and stepwise. But we still have likeminded, where we can easily perceive minded as having independent meaning. Dictionaries tell us it’s pronounced “like-MINE-did,” but I, for one, say “LIKE- minded” and have heard many others do so.

Therefore, like is ever so much more than some isolated thing clinically described in a dictionary with a definition like “(preposition) ‘having the same characteristics or qualities as; similar to.’” Think of a cold, limp, slimy squid splayed wet on a cutting board, its lifeless tentacles dribbling in coils, about to be sliced into calamari rings—in comparison to the brutally fleet, remorseless, dynamic creatures squid are when alive underwater—like as “(preposition) …” is wet on a cutting board.

There is a lot more to it: It swims, as it were. What we are seeing in like’s transformations today are just the latest chapters in a story that began with an ancient word that was supposed to mean “body.”

Because we think of like as meaning “akin to” or “similar to,” kids decorating every sentence or two with it seems like overuse. After all, how often should a coherently minded person need to note that something is similar to something rather than just being that something? The new like, then, is associated with hesitation. It is common to label the newer generations as harboring a fear of venturing a definite statement.

That analysis seems especially appropriate in that this usage of like first reached the national consciousness with its usage by Beatniks in the 1950s, as in, “Like, wow!” We associate the Beatniks, as a prelude to the counterculture with their free-ranging aesthetic and recreational sensibilities, with relativism. Part of the essence of the Beatnik was a reluctance to be judgmental of anyone but those who would dare to (1) be judgmental themselves or (2) openly abuse others. However, the Beatniks were also associated with a certain griminess—why would others imitate them?— upon which it bears mentioning that the genealogy of the modern like traces farther back. Ordinary people, too, have long been using like as an appendage to indicate similarity with a trace of hesitation. The “slow-like” kind of usage is a continuation of this, and Saul Bellow has thoroughly un- Beatnik characters in his novels of the 1950s use like in a way we would expect a decade or two later. “That’s the right clue and may do me some good. Something very big. Truth, like,” says Tommy Wilhelm in 1956’s Seize the Day, a character raised in the 1910s and ’20s, long before anyone had ever heard of a Beatnik. Bellow also has Henderson in Henderson the Rain King use like this way. Both Wilhelm and Henderson are tortured, galumphing char- acters riddled with uncertainty, but hippies they are not.

So today’s like did not spring mysteriously from a crowd on the margins of unusual mind-set and then somehow jump the rails from them into the general population. The seeds of the modern like lay among ordinary people; the Beatniks may not even have played a significant role in what happened later. The point is that like transformed from something occasional into something more regular. Fade out, fade in: recently I heard a lad of roughly sixteen chatting with a friend about something that had happened the weekend before, and his utterance was—this is as close to verbatim as I can get: So we got there and we thought we were going to have the room to ourselves and it turned out that like a family had booked it already. So we’re standing there and there were like grandparents and like grandkids and aunts and uncles all over the place. Anyone who has listened to American English over the past several decades will agree that this is thoroughly typical like usage.

The problem with the hesitation analysis is that this was a thoroughly confident speaker. He told this story with zest, vividness, and joy. What, after all, would occasion hesitation in spelling out that a family was holding an event in a room? It’s real-life usage of this kind—to linguists it is data, just like climate patterns are to meteorologists—that suggests that the idea of like as the linguistic equivalent to slumped shoulders is off.

Understandably so, of course—the meaning of like suggests that people are claiming that everything is “like” itself rather than itself. But as we have seen, words’ meanings change, and not just because someone invents a portable listening device and gives it a name composed of words that used to be applied to something else (Walkman), but because even the language of people stranded in a cave where life never changed would be under constant transformation. Like is a word, and so we’d expect it to develop new meanings: the only question, as always, is which one? So is it that young people are strangely overusing the like from the dictionary, or might it be that like has birthed a child with a different function altogether? When one alternative involves saddling entire generations of people, of an awesome array of circumstances across a vast nation, with a mysteriously potent inferiority complex, the other possibility beckons as worthy of engagement.

In that light, what has happened to like is that it has morphed into a modal marker—actually, one that functions as a protean indicator of the human mind at work in conversation. There are actually two modal marker likes—that is, to be fluent in modern American English is to have subconsciously internalized not one but two instances of grammar involving like.

Let’s start with So we’re standing there and there were like grandparents and like grandkids and aunts and uncles all over the place. That sentence, upon examination, is more than just what the words mean in isolation plus a bizarre squirt of slouchy little likes. Like grandparents and like grandkids means, when we break down what this teenager was actually trying to communicate, that given the circumstances, you might think it strange that an entire family popped up in this space we expected to be empty for our use, but in fact, it really was a whole family. In that, we have, for one, factuality—“no, really, I mean a family.” The original meaning of like applies in that one is saying “You may think I mean something like a couple and their son, but I mean something like a whole brood.”

And in that, note that there is also at the same time an acknowledgment of counterexpectation. The new like acknowledges unspoken objection while underlining one’s own point (the factuality). Like grandparents translates here as “There were, despite what you might think, actually grandparents.” Another example: I opened the door and it was, like, her! certainly doesn’t mean “Duhhhh, I suppose it’s okay for me to identify the person as her . . .” Vagueness is hardly the issue here. That sentence is uttered to mean “As we all know, I would have expected her father, the next-door neighbor, or some other person, or maybe a phone call or e-mail from her, but instead it was, actually, her.” Factuality and counterexpectation in one package, again. It may seem that I am freighting the little word with a bit much, but consider: It was, like, her! That sentence has a very precise meaning, despite the fact that because of its sociological associations with the young, to many it carries a whiff of Bubble Yum, peanut butter, or marijuana.

We could call that version of like “reinforcing like.” Then there is a second new like, which is closer to what people tend to think of all its new uses: it is indeed a hedge. However, that alone doesn’t do it justice: we miss that the hedge is just plain nice, something that has further implications for how we place this like in a linguistic sense. This is, like, the only way to make it work does not mean “Duhhhh, I guess this seems like the way to make it work.” A person says this in a context in which the news is unwelcome to the hearer, and this was either mentioned before or, just as likely, is unstatedly obvious. The like acknowledges—imagine even a little curtsey—the discomfort. It softens the blow—that is, eases—by swathing the statement in the garb of hypotheticality that the basic meaning of like lends. Something “like” x is less threatening than x itself; to phrase things as if x were only “like,” x is thus like offering a glass of water, a compress, or a warm little blanket. An equivalent is “Let’s take our pill now,” said by someone who is not, themselves, about to take the pill along with the poor sick person. The sick one knows it, too, but the phrasing with “we” is a soothing action, acknowledging that taking pills can be a bit of a drag.

Note that while this new like cushions a blow, the blow does get delivered. Rather than being a weak gesture, the new like can be seen as gentle but firm. The main point is that it is part of the linguistic system, not something merely littering it up. It isn’t surprising that a word meaning “similar to” morphs into a word that quietly allows us to avoid being bumptious, via courteously addressing its likeness rather than the thing itself, via considering it rather than addressing it. Just as uptalk sounds like a question but isn’t, like sounds like a mere shirk of certainty but isn’t.

Like LOL, like, entrenched in all kinds of sentences, used subconsciously, and difficult to parse the real meaning of without careful consideration, has all the hallmarks of a piece of grammar—specifically, in the pragmatic department, modal wing. One thing making it especially clear that the new like is not just a tic of heedless, underconfident youth is that many of the people who started using it in the new way in the 1970s are now middle-aged. People’s sense of how they talk tends to differ from the reality, and the person of a certain age who claims never to use like “that way” as often as not, like, does—and often. As I write, a sentence such as There were like grandparents and like grandkids in there is as likely to be spoken by a forty-something as by a teenager or a college student. Just listen around the next time you’re standing in a line, watching a talk show, or possibly even listening to yourself.

Then, the two likes I have mentioned must be distinguished from yet a third usage, the quotative like—as in “And she was like, ‘I didn’t even invite him.’ ” This is yet another way that like has become grammar. The meaning “similar to” is as natural a source here as it was for —ly: mimicking people’s utterances is talking similarly to, as in “like,” them. Few of the like-haters distinguish this like from the other new usages, since all are associated with young people and verbal slackerdom. But the third new like doesn’t do the jobs the others do: there is nothing hesitational or even polite about quotative like, much less especially forceful à la the reinforcing like. It is a thoroughly straightforward way of quoting a person, often followed by a verbatim mimicry complete with gestures. That’s worlds away from This is, like, the only way to make it work or There were like grandkids in there. Thus the modern American English speaker has mastered not just two, but actually three different new usages of like.

This article has been adapted from John McWhorter’s latest book , Words on the Move: Why English Won’t—and Can’t—Sit Still (Like, Literally).

“Like” is one of the most commonly used words in English – and when you’re new to learning the language, it can be a bit of a confusing one, as it has so many different meanings!

In fact – did you know that there are actually five different ways to use the word “like”? Phew! Sounds like hard work.

You might hear it a lot in everyday spoken English – especially as it has become very popular to use colloquially. But if you’re not sure on how to use this word correctly, then read on to find out.

Like – to enjoy

One of the most common ways that you’ll hear the word “like” is as a verb – “to like”.

This is a verb used to express the fact that you enjoy something, and it can be used just like many other verbs in English.

For example: “I like walking to work, but she liked to drive instead.”

Nice and simple!

Would like – to request something

“Like” can also be used as an alternative to the verb, “to want”, in a form that is considered less aggressive and demanding, and more polite. You would use the word with the modal verb, “would”, and you always need to use the full phrase “would like”.

For example: “She would like to place her order now.”

Be like – to describe the characteristics of something

This is when the uses of “like” start to get a bit more complex. In this use, the word is used to describe the personality, character or particular traits of something.

In this case it is used with the verb “to be”. If you are using it in the past tense, only the main part of the verb “to be” is changed, and the word “like” stays the same.

For example: “What was he really like?”

Like – as a simile

Developing from the previous use of the word, “like” is often used as a simile – or a comparison with something else, in order to describe something.

Sounds confusing? Let’s take a look at an example!

“The bedroom was like a disaster zone.”

In a simile, you still need to use the verb “to be” with the word “like”, but instead of describing the actual characteristics, you can use something else – which might be drastically different.

For example: “She was nervous and shaky, like a mouse.”

This is a great way of adding a bit more personality into your spoken English, but you would not use similes very often in written English, unless you are writing creatively.

Look like – describing appearances

The last common use of the word “like” is to describe experiences. This is done through the verb “to look like”. You can use this just as in the previous examples when you used the form “to be like”. In this case, the part of the phrase that changes according to tense and subject is “look”, while the word “like” stays the same.

For example: “I look like a really messy person, while she looks like a celebrity!”

Your turn

Understanding how the word “like” is used in different contexts and forms is a really helpful way to build on your English skills – make sure you practice each of the five uses as much as you can!

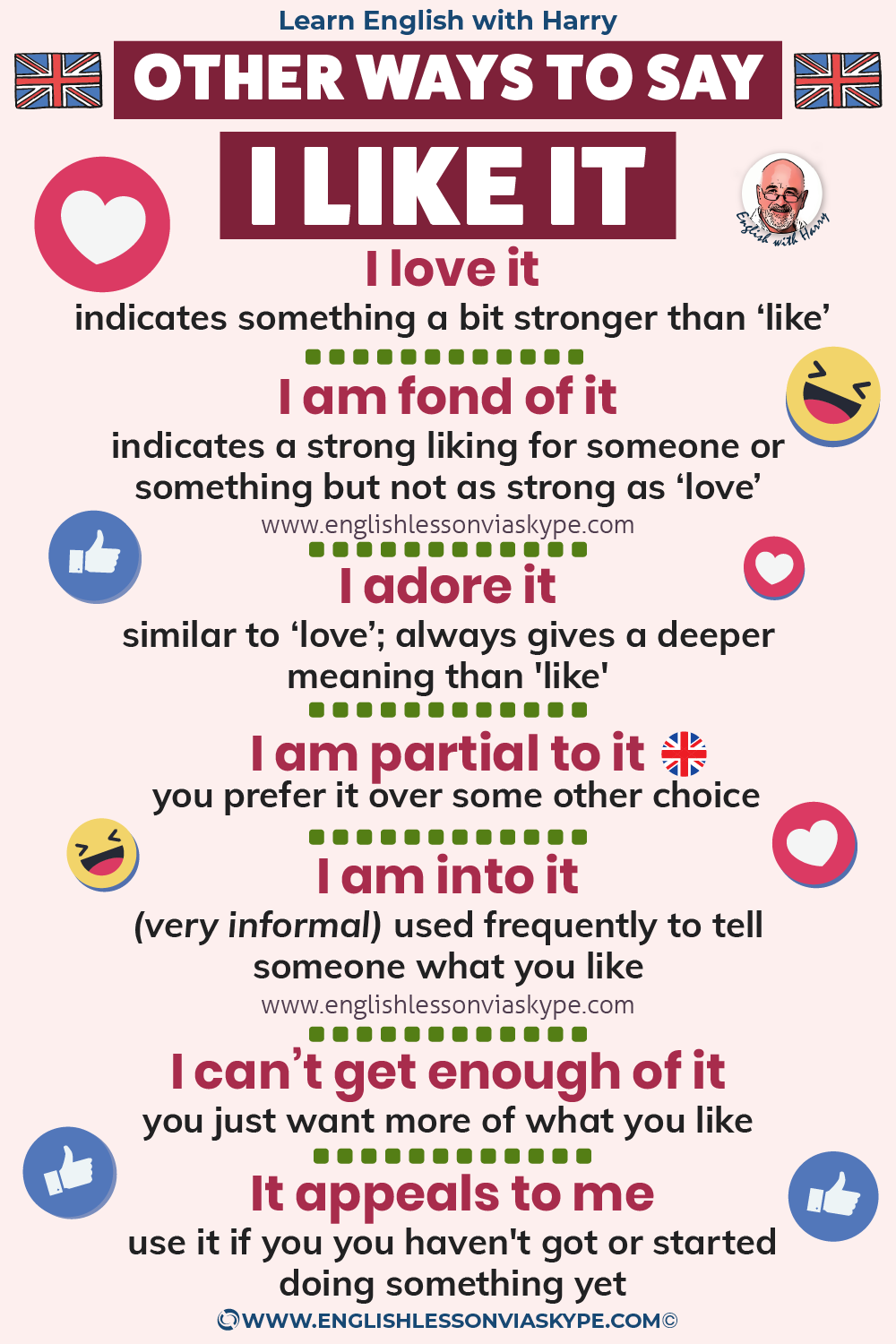

Other words for LIKE and why you need to use them.

Avoid using the same words over and over again. Boost your English vocabulary and improve your speaking and writing skills.

Table of Contents

Harry

Harry is a native English teacher with over 10 years of experience both online and in face-to-face lessons. With his extensive experience in business, he specialises in Business English lessons but happily teaches ESL students with any English learning needs.

other words for like in english

The word LIKE is a very popular word in the English language.

We use LIKE as an adjective, a verb and even a noun.

The only bad thing about the verb LIKE is that we use it way too often.

Some students may wonder whether we have any other words for LIKE in English?

In fact, there are many, many ways to say instead of LIKE. So here are some English words and phrases that you can use as alternatives to I LIKE.

Intermediate to Advanced English Marathon

INSANITY: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

- What you’ll learn:

- better understanding of more complex grammar structures

- advanced English vocabulary words

- British & American slang

- perfect your listening skills through practing different accents

- This marathon is for you if you’re:

- stuck at an intermediate English level

- tired of confusing explanations

- a mature student

- shy & introverted

We use I LIKE to express our feeling about somebody or something. For example:

I like ice cream.

I like Mathew.

Of course, we could add various English adverbs to give more meaning to it. For example:

I really like ice cream.

I really like Mathew.

I genuinely like Mathew.

I totally like her.

But it can be a little boring to always use the same words or expressions so here are some suitable alternative words you can use instead of LIKE.

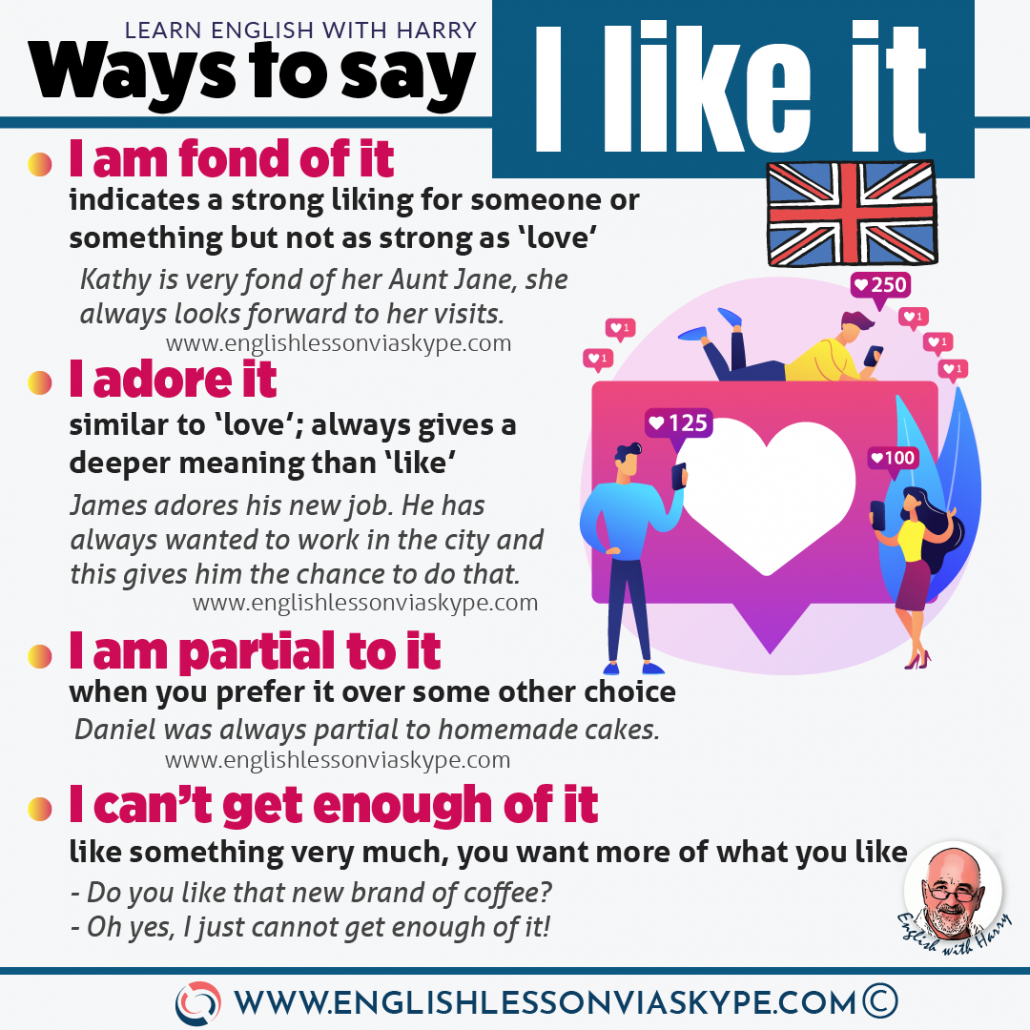

Other Ways to Say I like it in English

I love

Love indicates something a bit stronger than “like”.

Example:

👱♂️ Would you like a cup of tea?

👩 I would love a cup of tea.

I am fond of

Fond of indicates a strong liking for someone or something but not as strong as “love”.

Example:

Kathy is very fond of her Aunt Jane, she always looks forward to her visits.

I adore

Like ‘love’, ‘adore’ always gives a deeper meaning than ‘like’.

Example:

James adores his new job. He has always wanted to work in the city and this gives him the chance to do that.

I am partial to

A very British English expression. To be partial to something means you prefer it over some other choice.

Example:

Daniel was always partial to homemade cakes. He enjoyed the cakes in the local bakery but a homemade cake was his favourite every time.

Some more informal ways of saying LIKE include the following:

to dig something

This is a very 1960’s or 1970’s expression. People used to ‘dig’ the new music by The Beatles. So this is really something related to the hippy years.

Example:

I dig your outfit.

I am into

Very informal and almost slang expression. This is used frequently to tell someone what you like.

Example:

The teacher asked Kevin what music he liked, ‘I am really into U2, they get it right every time.

I cannot get enough

Again more informal meaning you just want more of what you like.

Example:

👨🦳 Do you like that new brand of coffee?

👱♀️ Oh yes, certainly, I just cannot get enough of it!

Or as Depeche Mode sing I just can’t get enough

Other Words for Like in English

So here are the words we can use instead of LIKE, let’s go through them one more time:

- I love

- I am fond of

- I adore

- I am partial to

- I dig

- I am into

- I cannot get enough

More Information

You will love these English lessons

English Vocabulary

How to Learn English

English Idioms

Heard of hygge? How about fika or abbiocco? It appears we are familiar with some words in different languages but not others.

Why do some words in different languages just happen to end up in our everyday use and stay there? Who knows, but that’s not to say we can’t learn others that are equally expressive.

I love the English language. So I have to say that it pains me to admit that sometimes, English lacks descriptive adjectives, nouns, or verbs. Here’s one example; you know that lovely sleepy feeling you get after you’ve eaten a full meal? The Italians call that ‘abbiocco’, the desire to nap when you’ve finished a big dinner.

So, in the interests of knowledge, I’m putting my personal pain aside to find those perfect words in different languages that sum up emotions and situations. Let’s hope that some of the following become as popular as hygge!

20 Untranslatable Words in Different Languages

1. Anake (Greek)

This word describes a “binding force or necessity which the classical Greeks knew could not be resisted”. Or, in other words, a powerful force that leads us to our soulmate.

2. Craic (Irish)

This is a term for a great laugh or a good time with other people. You can use it as a noun to describe the fun you had, or to ask ‘Where’s the craic tonight?’

3. Fika (Swedish)

Fika today at 10 am anyone? Don’t worry, it’s nothing painful. Fika is a Swedish word for a scheduled coffee break. It happens twice a day and allows you to ‘pause and reconnect’.

4. Utepils (Norwegian)

Who fancies utepils after work today? The English would have to use far more words than necessary to convey this word. It means going for a nice drink outside after a hard day at work. Those clever Norwegians only have to mention ‘utepils’ and the coats are already on.

5. Treppenwitz (German)

Have you ever been caught with a severe bout of ‘Treppenwitz’? Translated from German it means staircase joke. It represents the situations where you think of a witty response but far too late to use it. Hence, you are on the staircase on your way out when you come up with your funny retort.

6. Schnapsidee (German)

This is another German word that literally translated into English means ‘Schnapps Idea’. Or, in other words, any kind of silly plan one comes up with when drunk.

7. Saudade (Portuguese)

Saudade is a beautiful word of Portuguese origins that is quite difficult to fully explain. It’s the love we feel when a person has gone. The precious memories we have that evoke happiness and joy, but also the emptiness of knowing that person is gone forever.

It can also be used to describe a feeling of loss for something we never had, like unrequited love.

8. Desenrascanco (Portuguese)

This is another Portuguese word and loosely originates from the words ‘des’ which means “un” and ‘enrascar’ meaning “to entangle.” The literal translation is to cleverly disentangle oneself from a bad situation, but, with the ability to use one’s imagination in ingenious ways.

9. Sitzfleisch (German)

The literal translation of this German word is ‘sit flesh’. Germans also translate this word as ‘sit meat’ and ‘butt flesh’. However, the meaning of the word is the ability to endure a boring task whilst sitting.

10. Sitzpinkler (German)

Another German word beginning with ‘sitz’, or sit. But this one is a derogatory term for a man who sits down when he has a pee.

11. Gigil (Philippines)

Tagalog is a language spoken in the Phillippines. In Tagalog, gigil means an extreme urge to hug and squeeze someone. It works as a positive emotion, for example, “That baby is so adorable, I just want to squeeze her!” or a negative one, “You’re so irritating I could squeeze some sense into you!”

12. Tampo (Philippines)

No, it’s not what you think. Tampo is a pretend tantrum, thrown in order to elicit an apology from someone. To throw a good tampo try stamping your feet, pouting your lips and crossing your arms.

13. Cafune (Portuguese)

There’s something very relaxing about a spot of cafune. This is a Portuguese word and it means caressing or tenderly running your fingers through your loved one’s hair. You can also use this word for cats and dogs.

14. Viitsima (Estonian)

Have you ever felt like you just can’t be bothered to do anything? That feeling of laziness and lethargy where you have no interest and don’t want to make an effort? Viitsima is Estonian for this emotion.

15. Gezelligheid (Dutch)

Gezelligheid is a Dutch word and has a similar meaning to hygge. It is the warm, cozy, pleasant feeling of being at home, surrounded by good friends and family.

16. Dar un toque (Spanish)

Ever called a mobile and then quickly cut off the call so that the other person will call you back, thus saving you money? Dar un toque, or ‘give a touch’ is Spanish and used for all kinds of fast communications, such as a quick ‘thinking of you’, ‘I’m home safely’, or ‘I’m on my way’.

17. Мерзлячка (Russian)

Some words in different languages are definitely harder to pronounce than others. But if you know someone that hates the cold, you might want to learn this word. In Russian, a ‘Merzlyachka’ is usually a female who is extremely sensitive to cold environments and does not tolerate freezing temperatures.

18. Aktivansteher (German)

How good are you at spotting the right queue to join? If you’re anything like me, you’ll get stuck behind the person that ends up with a problem and takes ages to sort it out.

However, the aktivansteher is a person with an uncanny skill of spotting the fastest queue. They move with zen-like efficiency and are gone before we have even started taking our shopping out of our trollies.

19. Hüftgold (German)

I realize that in this list of words in different languages, there are many German words that made the cut. But there were just so many amazing ones I couldn’t resist.

For example, people that love their food in Germany are celebrated. As a result, the extra weight people carry on their hips is known as Hüftgold, or ‘hip gold’.

20. Wortschatz (German)

My final example and my favorite in this list of words in different languages is Wortschatz. It is German, the literal meaning is ‘word treasure’ and it is the German word for vocabulary.

References:

- https://thoughtcatalog.com

- https://www.scientificamerican.com

- Author

- Recent Posts

Sub-editor & staff writer at Learning Mind

Janey Davies has been published online for over 10 years. She has suffered from a panic disorder for over 30 years, which prompted her to study and receive an Honours degree in Psychology with the Open University. Janey uses the experiences of her own anxiety to offer help and advice to others dealing with mental health issues.

Copyright © 2012-2023 Learning Mind. All rights reserved. For permission to reprint, contact us.

Like what you are reading? Subscribe to our newsletter to make sure you don’t miss new thought-provoking articles!