On this page you will learn how to say language in Russian

язык [yi-ZYK]

русский язык [ROOS-kiy yi-ZYK]

английский язык [an-GLIY-skiy yi-ZYK]

[baslider name=”language in Russian translation”]

язык [yi-ZYK] = language – noun, Masculine, Singular, Nominative Case

русский язык [ROOS-kiy yi-ZYK] = the Russian language

русский [ROOS-kiy] = Russian – adjective, Masculine, Singular, Nominative Case

английский язык [an-GLIY-skiy yi-ZYK] = the English language

английский [an-GLIY-skiy] = English – adjective, Masculine, Singular, Nominative Case

- Video

-

- Pronunciation

- In English letters

-

язык [yi-ZYK]

русский язык [ROOS-kiy yi-ZYK]

английский язык [an-GLIY-skiy yi-ZYK] - Image

-

[baslider name=”language in Russian translation”]

- About the word

-

язык [yi-ZYK] = language – noun, Masculine, Singular, Nominative Case

русский язык [ROOS-kiy yi-ZYK] = the Russian language

русский [ROOS-kiy] = Russian – adjective, Masculine, Singular, Nominative Caseанглийский язык [an-GLIY-skiy yi-ZYK] = the English language

английский [an-GLIY-skiy] = English – adjective, Masculine, Singular, Nominative Case

Perhaps, you would also like to learn how we say how are you today in Russian. See also how to say you too and happy new year in Russian.

Learning Russian has gotten popular today in the world. It may be that you have previously started picking up Russian when you heard Russian words said in a movie, in a song, or written in a book (in a marginal note). Perhaps, you needed to learn some cool popular Russian phrases. You surfed YouTube and Google seeking for a Russian pronunciation guide to pick up elementary Russian pronunciation and spelling. Or perhaps you felt like learning how to speak and write Russian and you asked yourself how to write Cyrillic in English letters.

On this Internet resource you can find general phrases in English translated to Russian. Plus, you can listen to Russian language audio in MP3 files and learn most everyday Russian phrases. However, language acquisition is not limited to learning the pronunciation of words in Russian. You need to get a live picture of the word into your mind, and you can do it on this website by learning popular Russian words with images. And much more! You can not only listen to online recordings of Russian phrases and popular words, but look at how these words are articulated by watching a video and learning the translation of the word! At last, to make the pictures of the words sink into your mind, this Internet resource has a pronunciation handbook in English letters. Thus, as you can see, we use a broad complex of learning instruments to help you win in studying Russian through English.

Now you can come across various free resources for learning Russian: podcasts, Internet pages, YouTube channels and Internet pages like this one that will help you study orthography, pronunciation, grammar, Russian Cyrillic letters, helpful Russian phrases, speaking. However, all these Internet resources give you unstructured language details, and this can make things complicated for you. To get rid of confusion and get organized knowledge as well as to save your time, you need a Russian tutor because it’s their concern to organize the material and give you what you need the most. A teacher knows your strengths and weaknesses, your unique pronunciation and knows how to reach your language aims. The only thing you need to do is to count on your teacher and enjoy your high-level Russian language in a 6-month time.

Now you know Russian word for language.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Languages of Russia | |

|---|---|

Memorial in Vyborg in Russian, German, Swedish and Finnish. |

|

| Official | Russian[1] |

| Semi-official | Thirty-five languages |

| Minority | Dozens of languages of the Indo-European, Northeast Caucasian, Northwest Caucasian, Uralic, Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic and Paleosiberian language families |

| Foreign | 13–15% have foreign language knowledge[2][3]

|

| Signed | Russian Sign Language |

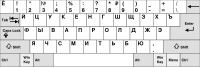

| Keyboard layout |

Russian keyboard |

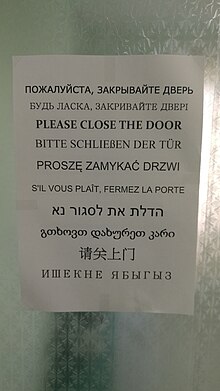

Of all the languages of Russia, Russian, the most widely spoken language, is the only official language at the national level. There are 35 languages which are considered official languages in various regions of Russia, along with Russian. There are over 100 minority languages spoken in Russia today.[5]

From 2020, amendments to the Russian Constitution stipulate that Russian is the language of the «state forming people». With president Vladimir Putin’s signing of an executive order on 3 July 2020 to insert the amendments into the constitution, they took effect on 4 July 2020.[6]

History[edit]

Russian lost its status in many of the new republics that arose following the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union. In Russia, however, the dominating status of the Russian language continued. Today, 97% of the public school students of Russia receive their education only or mostly in Russian, even though Russia is made up of approximately 80% ethnic Russians.[citation needed]

Russification[edit]

On 19 June 2018, the Russian State Duma adopted a bill that made education in all languages but Russian optional, overruling previous laws by ethnic autonomies, and reducing instruction in minority languages to only two hours a week.[7][8][9] This bill has been likened by some commentators, such as in Foreign Affairs, to a policy of Russification.[7]

When the bill was still being considered, advocates for the minorities warned that the bill could endanger their languages and traditional cultures.[9][10] The law came after a lawsuit in the summer of 2017, where a Russian mother claimed that her son had been «materially harmed» by learning the Tatar language, while in a speech Vladimir Putin argued that it was wrong to force someone to learn a language that is not their own.[9] The later «language crackdown» in which autonomous units were forced to stop mandatory hours of native languages was also seen as a move by Putin to «build identity in Russian society».[9]

Protests and petitions against the bill by either civic society, groups of public intellectuals or regional governments came from Tatarstan (with attempts for demonstrations suppressed),[11] Chuvashia,[9] Mari El,[9] North Ossetia,[11][12] Kabardino-Balkaria,[11][13] the Karachays,[11] the Kumyks,[11][14] the Avars,[11][15] Chechnya,[7][16] and Ingushetia.[17][7] Although the «hand-picked» Duma representatives from the Caucasus did not oppose the bill,[7] it prompted a large outcry in the North Caucasus[11] with representatives from the region being accused of cowardice.[7] The law was also seen as possibly destabilizing, threatening ethnic relations and revitalizing the various North Caucasian nationalist movements.[7][9][11] The International Circassian Organization called for the law to be rescinded before it came into effect.[18] Twelve of Russia’s ethnic autonomies, including five in the Caucasus called for the legislation to be blocked.[7][19]

On 10 September 2019, Udmurt activist Albert Razin self-immolated in front of the regional government building in Izhevsk as it was considering passing the controversial bill to reduce the status of the Udmurt language.[20] Between 2002 and 2010 the number of Udmurt speakers dwindled from 463,000 to 324,000.[21] Other languages in the Volga region recorded similar declines in the number of speakers; between the 2002 and 2010 censuses the number of Mari speakers declined from 254,000 to 204,000[10] while Chuvash recorded only 1,042,989 speakers in 2010, a 21.6% drop from 2002.[22] This is attributed to a gradual phasing out of indigenous language teaching both in the cities and rural areas while regional media and governments shift exclusively to Russian.

In the North Caucasus, the law came after a decade in which educational opportunities in the indigenous languages was reduced by more than 50%, due to budget reductions and federal efforts to decrease the role of languages other than Russian.[7][11] During this period, numerous indigenous languages in the North Caucasus showed significant decreases in their numbers of speakers even though the numbers of the corresponding nationalities increased, leading to fears of language replacement.[11][23] The numbers of Ossetian, Kumyk and Avar speakers dropped by 43,000, 63,000 and 80,000 respectively.[11] As of 2018, it has been reported that the North Caucasus is nearly devoid of schools that teach in mainly their native languages, with the exception of one school in North Ossetia, and a few in rural regions of Dagestan; this is true even in largely monoethnic Chechnya and Ingushetia.[11] Chechen and Ingush are still used as languages of everyday communication to a greater degree than their North Caucasian neighbours, but sociolinguistics argue that the current situation will lead to their degradation relative to Russian as well.[11]

In 2020, a set of amendments to the Russian constitution was approved by the State Duma[24] and later the Federation Council.[25] One of the amendments is to enshrine Russian as the “language of the state-forming nationality” and the Russian people as the ethnic group that created the nation.[26] The amendment has been met with criticism from Russia’s minorities[27][28] who argue that it goes against the principle that Russia is a multinational state and will only marginalize them further.[29]

Official languages[edit]

Although Russian is the only federally official language of Russia, there are several other officially recognized languages within Russia’s various constituencies – article 68 of the Constitution of Russia only allows the various republics of Russia to establish official (state) languages other than Russian. This is a list of the languages that are recognized as official (state) in constitutions of the republics of Russia, as well as the number of native speakers according mostly to the 2010 Census or more recent ones:[30]

| Language | Language family | Federal subject(s) | Speakers in Russia[30] | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abaza | Northwest Caucasian | 37,831 (2010 Census-2014)[31][32] | [33] | |

| Adyghe | Northwest Caucasian | 128,000 (2015)[34] | [35] | |

| Avar | Northeast Caucasian | 800,000 (2010 Census)[36] | [37] | |

| Altai | Turkic | 55,720 (2010 Census) | [38][39] | |

| Bashkir | Turkic | 1,152,404 (2010 Census) [40] | [41] see also regional law | |

| Buryat | Mongolic | 265,000 (2010 Census) [42] | [43] | |

| Chechen | Northeast Caucasian | 1,354,705 (2010 Census) | [44] | |

| Chuvash | Turkic | 1,042,989 (2010 Census) | [45] | |

| Crimean Tatar | Turkic | 308 (2010 Census)

228,000 (2019) [a] [46] |

[47] | |

| Erzya | Uralic | 36,726 (2010 Census) | [48] | |

| Ingush | Northeast Caucasian | 305,868 (2010 Census) | [49] | |

| Kabardian | Northwest Caucasian | 590,000 (2010 Census) | [33][50] | |

| Kalmyk | Mongolic | 80,546 (2010 Census) | [51] | |

| Karachay-Balkar | Turkic | 305,364 (2010 Census) | [33][50] | |

| Khakas | Turkic | 43,000 (2010 Census) | [52] | |

| Komi-Zyrian | Uralic | 160,000 (2010 Census) | [53] | |

| Hill Mari, Meadow Mari | Uralic | 470,000 (2012)[54] | [55] | |

| Moksha | Uralic | 130,000 (2010 Census) | [48] | |

| Nogai | Turkic | 87,119 (2010 Census) | [33] | |

| Ossetian | Indo-European (Iranian) | 451,431 (2010 Census) | [56] | |

| Tatar | Turkic | 4,280,718 (2010 Census) | [57] | |

| Tuvan | Turkic | 280,000 (2010) | [58] | |

| Udmurt | Uralic | 324,338 (2010 Census) | [59] | |

| Ukrainian | Indo-European (Slavic) | 1,129,838 (2010 Census) | [47] | |

| Yakut | Turkic | 450,140 (2010 Census) | [60] |

- ^ a b c Annexed by Russia in 2014; recognized as a part of Ukraine by most of the UN Member States.

The Constitution of Dagestan defines «Russian and the languages of the peoples of Dagestan» as the state languages,[61] though no comprehensive list of the languages was given.[citation needed][dubious – discuss] 14 of these languages (including Russian) are literary written languages; therefore they are commonly considered to be the official languages of Dagestan. These are, besides Russian, the following: Aghul, Avar, Azerbaijani, Chechen, Dargwa, Kumyk, Lak, Lezgian, Nogai, Rutul, Tabasaran, Tat and Tsakhur. All of these, except Russian, Chechen and Nogai, are official only in Dagestan and in no other Russian republic.

In the project of the «Law on the languages of the Republic of Dagestan» 32 languages are listed; however, this law project never came to life.[62]

Karelia is the only republic of Russia with Russian as the only official language.[63] However, there exists the special law about state support and protection of the Karelian, Vepsian and Finnish languages in the republic, see next section. [64]

Other recognized languages[edit]

The Government of the Republic of Bashkortostan adopted the Law on the Languages of Nations, which is one of the regional laws aimed at protecting and preserving minority languages.[65][66][67] The main provisions of the law include General Provisions, Language names of geographic regions. objects and inscriptions, road and other signs, liability for violations of Bashkortostan in the languages of Bashkortostan. In the Republic of Bashkortostan, equality of languages is recognized. Equality of languages is a combination of the rights of peoples and people to preserve and fully develop their native language, freedom of choice and use of the language of communication. The writing of names of geographical objects and the inscription, road and other signs along with the state language of the Republic of Bashkortostan can be done in the languages of Bashkortostan in the territories where they are concentrated. Similar laws were adopted in Mari El, Tatarstan, Udmurtia, Khakassia and the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug.

The federal law «On the languages of the peoples of the Russian Federation» [68] allows the federal subjects to establish additionally official languages in the areas where minority groups live. The following 15 languages benefit from various degrees of recognition in various regions under this law:

- Buryat in the Agin-Buryat Okrug

- Chukchi in Yakutia

- Dolgan in Yakutia

- Even in Yakutia

- Evenki in Yakutia

- Finnish in Karelia

- Karelian in Karelia

- Kazakh in Altai

- Khanty in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug and the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug

- Komi-Permyak in the Komi-Permyak Okrug

- Mansi in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug

- Nenets in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug, the Nenets Autonomous Okrug and the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug

- Selkup in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug

- Veps in Karelia

- The Yukaghir languages in Yakutia

Migrant languages[edit]

As a result of mass migration to Russia from the former USSR republics (especially from the Caucasus and Central Asia) many non-indigenous languages are spoken by migrant workers. For example, in 2014 2.4 million Uzbek citizens and 1.2 million Tajik citizens entered Russia.[69]

For comparison, Russian citizens with ethnicities matching these of home countries of migrant workers of are much lower (from 2010 Russian Census, in thousands):

| Armenian | 830 |

| Azerbaijani | 515 |

| Kazakh | 472 |

| Uzbek | 245 |

| Kyrgyz | 247 |

| Tajik | 177 |

| Georgian | 102 |

| Romanian | 90 |

Endangered languages in Russia[edit]

There are many endangered languages in Russia. Some are considered to be near extinction and put on the list of endangered languages in Russia, and some may have gone extinct since data was last reported. On the other hand, some languages may survive even with few speakers.

Some languages have doubtful data, like Serbian whose information in the Ethnologue is based on the 1959 census.

Languages near extinction[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (September 2020) |

Most numbers are according to Michael Krauss, 1995. Given the time that has passed, languages with extremely few speakers might be extinct today. Since 1994, Kerek, Aleut, Medny Aleut, Akkala Sami and Yugh languages have become extinct.

- Enets (70)

- Ingrian

- Negidal

- Orok (30–82)

- Sami, Ter (2)

- Tofalar (25–30)

- Udege (100)

- Votic (8, 60-non native)

- Ket (20 speakers) (2019)

- Yukaghir, Northern (30–150)

- Yukaghir, Southern (10–50)

- Yupik

Foreign languages[edit]

According to the various studies made in 2005-2008 by Levada-Center[2] 15% of Russians know a foreign language. From those who claim knowledge of at least one language:

| English | 80% |

| German | 16% |

| French | 4% |

| Turkish | 2% |

| Others | 9% |

| From 1775 respondents aged 15-29, November 2006 |

| English | 44% |

| German | 15% |

| Ukrainian, Belarusian and other Slavic languages | 19% |

| Other European languages | 10% |

| All others | 29% |

| From 2100 respondents of every age, January 2005 |

Knowledge of at least one foreign language is predominant among younger and middle-aged population. Among aged 18–24 38% can read and «translate with a dictionary», 11% can freely read and speak. Among aged 25–39 these numbers are 26% and 4% respectively.

Knowledge of a foreign language varies among social groups. It is most appreciable (15-18%) in big cities with 100,000 and more inhabitants, while in Moscow it rises up to 35%. People with higher education and high economical and social status are most expected to know a foreign language.

The new study by Levada-Center in April 2014[3] reveals such numbers:

| English | 11% |

| German | 2% |

| Spanish | 2% |

| Ukrainian | 1% |

| French | <1% |

| Chinese | <1% |

| Others | 2% |

| Can speak a foreign language but with difficulty | 13% |

|---|---|

| Do not speak a foreign Language at all | 70% |

| From 1602 respondents from 16 and older, April 2014 |

The age and social profiling are the same: knowledge of a foreign language is predominant among the young or middle-aged population with higher education and high social status and who live in big cities.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, French was a common language among upper class Russians. The impetus came from Peter the Great’s orientation of Russia towards Europe and accelerated after the French Revolution. After the Russians fought France in the Napoleonic Wars, Russia became less inclined towards French.[70]

In 2015, a survey taken in all federal subjects of Russia showed that 70% of Russians could not speak a foreign language. Almost 30% could speak English, 6% could speak German, 1% could speak French, 1% could speak Spanish, 1% could speak Arabic and 0.5% could speak another language.[71]

| Language | % of speakers in Russia (2003) | % of speakers in Russia (2015) | Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | 16 | 30 | |

| German | 7 | 6 | |

| French | 1 | 1 |

English[edit]

[71]

| Knowledge | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Can speak English to a degree | 30% |

| Can read and translate using a dictionary | 20% |

| Can understand colloquial language | 7% |

| Can speak very fluently | 3% |

Languages of education[edit]

Every year the Russian Ministry of Education and Science publishes statistics on the languages used in schools. In 2014/2015 the absolute majority[72] (13.1 million or 96%) of 13.7 million Russian students used Russian as a medium of education. Around 1.6 million or 12% students studied their (non-Russian) native language as a subject. The most studied languages are Tatar, Chechen and Chuvash with 347,000, 253,000 and 107,000 students respectively.

The most studied foreign languages in 2013/2014 were (students in thousands):

| English | 11,194.2 |

| German | 1,070.5 |

| French | 297.8 |

| Spanish | 20.1 |

| Chinese | 14.9 |

| Arabic | 3.4 |

| Italian | 2.9 |

| Others | 21.7 |

See also[edit]

- Demography of Russia

- List of languages of Russia

- Languages of the Caucasus

- Russian Academy of Sciences, the language regulator in Russia

References[edit]

- ^ «The Constitution of the Russian Federation — Chapter 3. The Federal Structure, Article 68». constitution.ru. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ a b Знание иностранных языков в России [Knowledge of foreign languages in Russia] (in Russian). Levada Center. 16 September 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ a b Владение иностранными языками [Command of foreign languages] (in Russian). Levada Center. 28 May 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ «Percentage of Russians who speak English doubles to 30%». Russia Beyond. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ «Russia — Language, Culture, Customs and Etiquette». Kwintessential.co.uk. Archived from the original on 31 May 2013.

- ^ Language of “state forming people”.Putin signing amendments into law

- ^ a b c d e f g h i «Putin’s Plan to Russify the Caucasus». Foreign Affairs. 1 August 2018.

- ^ «Gosduma prinyala chtenii zakonoproekt ob izuchen’i rodnyix yez’ikov». RIA Novosti. 19 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Russian minorities fear for languages amid new restrictions». Deutsche Welle. 5 December 2017.

- ^ a b Coalson, Robert; Lyubimov, Dmitry; Alpaut, Ramazan (20 June 2018). «A Common Language: Russia’s ‘Ethnic’ Republics See Language Bill As Existential Threat». Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Kaplan, Mikail (31 May 2018). «How Russian state pressure on regional languages is sparking civic activism in the North Caucasus». Open Democracy. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018.

- ^ «Тамерлан Камболов попросит Путина защитить осетинский язык». Gradus. 3 August 2018.

- ^ «Кабардино-Балкария против законопроекта о добровольном обучении родным языкам». 23 April 2018.

- ^ «Кумыки потребовали снять с повестки дня Госдумы законопроект о добровольном изучении языков». Idel Real. 10 May 2018.

- ^ «В Хасавюрте прошёл митинг в поддержку преподавания родного языка». Idel Real. 15 May 2018.

- ^ «Чеченские педагоги назвали факультативное изучение родного языка неприемлемым». Kavkaz Uzel. 30 July 2018.

- ^ «Общественники Ингушетии: законопроект о языках – «циничная дискриминация народов»«. Kavkaz Realii. 12 June 2018.

- ^ «Международная черкесская ассоциация призвала заблокировать закон о родных языках». Kavkaz Uzel. 5 July 2018.

- ^ «Представители нацреспублик России назвали закон о родных языках антиконституционным». Kavkaz Uzel. 1 July 2018.

- ^ «Russian Scholar Dies From Self-Immolation While Protesting to Save Native Language». The Moscow Times. 10 September 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ «Man Dies After Self-Immolation Protest Over Language Policies in Russia’s Udmurtia». Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 10 September 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ Blinov, Alexander (10 June 2022). «Alexander Blinov: «In state structures, the Chuvash language most often performs a symbolic function»«. Realnoe Vremya (in Russian). Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ «Живой на бумаге». RFE/RL. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ Seddon, Max; Foy, Henry (10 March 2020). «Kremlin denies Russia constitution rewrite is Putin power grab». Financial Times. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ «Russian Lawmakers Adopt Putin’s Sweeping Constitutional Amendments». The Moscow Times. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ Budryk, Zack (3 March 2020). «Putin proposes gay marriage constitutional ban in Russia». The Hill. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ Jalilov, Rustam (11 March 2020). «Amendment to state-forming people faces criticism in the North Caucasus». Caucasian Knot (in Russian). Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ Alpout, Ramadan (10 March 2020). ««We are again foreigners, but now officially.» Amendment to the constituent people». Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (in Russian). Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ Rakhmatullin, Timur (5 March 2020). «Who to benefit from ‘Russian article’ in the Constitution?». Realnoe Vremya. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ a b «2010 All-Russian Population Census» (PDF). Federal State Statistics Service: 142–143.

- ^ «The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire». www.eki.ee. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ «Abaza». Ethnologue. 19 November 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d «Конституция Карачаево-Черкесской Республики от 5 марта 1996 г. / Глава 1. Основы конституционного строя (ст.ст. 1-13)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Adyghe». Ethnologue. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ «Конституция Республики Адыгея (принята на XIV сессии Законодательного Собрания (Хасэ) — Парламента Республики Адыгея 10 марта 1995 года) / Глава 1. Права и свободы человека и гражданина (ст.ст. 18 — 46)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Avar». Ethnologue. 19 November 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ «Конституция Республики Дагестан (принята Конституционным Собранием 10 июля 2003 г.)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Конституция Республики Алтай (Основной Закон) (принята 7 июня 1997 г.) / Глава I. Общие положения (ст.ст. 22-26)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ Закон Республики Алтай — Глава I. Общие положения — Статья 4. Правовое положение языков [Law of the Republic of Altai — Chapter I. General provisions — Article 4. Legal status of languages] (in Russian). Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- ^ «Bashkir». Ethnologue. 19 November 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ «Конституция Республики Башкортостан от 24 декабря 1993 г. N ВС-22/15 / Глава 1. Основы конституционного строя Республики Башкортостан (ст.ст. 1-16)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Buryat». Ethnologue. 19 November 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ «Конституция Республики Бурятия (принята Верховным Советом Республики Бурятия 22 февраля 1994 г.) / Глава 3. Государственно-правовой статус Республики Бурятия (ст.ст. 60-68)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Конституция Чеченской Республики (принята 23 марта 2003 г.) / Глава 1. Основы конституционного строя (ст.ст. 1 — 13)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Конституция Чувашской Республики (принята Государственным Советом Чувашской Республики 30 ноября 2000 г.) / Глава 1. Основы конституционного строя Чувашской Республики (ст.ст. 1 — 13)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ Tyers, Francis M.; Washington, Jonathan N.; Kavitskaya, Darya; Gökırmak, Memduh (2019). «A Biscriptual Morphological Transducer for Crimean Tatar». Proceedings of the Workshop on Computational Methods for Endangered Languages. doi:10.33011/computel.v1i.423. S2CID 201624024.

- ^ a b «Constitution of the Republic of Crimea». Article 10 (in Russian). State Council, Republic of Crimea. 11 April 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ a b «Конституция Республики Мордовия (принята 21 сентября 1995 г.) / Глава 1. Основы конституционного строя Республики Мордовия (п.п. 1 — 13)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Конституция Республики Ингушетия (принята 27 февраля 1994 г.)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ a b «Конституция Кабардино-Балкарской Республики от 1 сентября 1997 г. N 28-РЗ (принята Парламентом Кабардино-Балкарской Республики 1 сентября 1997 г.) (в редакции, принятой Конституционным Собранием 12 июля 2006 г., республиканских законов от 28 июля 2001 г. / Глава III Государственное устройство (ст.ст. 67-77)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Степное Уложение (Конституция) Республики Калмыкия от 5 апреля 1994 г.» constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Конституция Республики Хакасия (принята на XVII сессии Верховного Совета Республики Хакасия (первого созыва) 25 мая 1995 года) / Глава III. Статус и административно-территориальное устройство Республики Хакасия (ст.ст. 58 — 71)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Конституция Республики Коми от 17 февраля 1994 г. / Глава III. Государственный статус Республики Коми и административно-территориальное устройство (ст.ст. 61 — 70)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Mari». Ethnologue. 19 November 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ «Конституция Республики Марий Эл (принята Конституционным Собранием Республики Марий Эл 24 июня 1995 г.) / Глава I. Основы конституционного строя (ст.ст. 1 — 16)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Конституция Республики Северная Осетия-Алания (принята Верховным Советом Республики Северная Осетия 12 ноября 1994 г.) / Глава 1. Основы конституционного строя (ст.ст. 1-17)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Конституция Республики Татарстан от 6 ноября 1992 г. / Глава 1. Государственный Совет Республики Татарстан (ст.ст. 67 — 88)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Конституция Республики Тыва (принята Референдумом Республики Тыва 6 мая 2001 г.) / Глава I. Основы конституционного строя (ст.ст.1-17)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Конституция Удмуртской Республики от 7 декабря 1994 г. / Глава 1. Основы Конституционного строя (ст.ст. 1 — 15)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Конституция (Основной Закон) Республики Саха (Якутия) / Глава 3. Национально-государственный статус, административно-территориальное устройство (ст. 36 — 53)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Конституция Республики Дагестан (принята Конституционным Собранием 10 июля 2003 г.) / Глава 1. Основы конституционного строя (ст.ст. 1 — 17)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «В Дагестане сделают государственными 32 языка». Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ «Конституция Республики Карелия / Глава 1. Основные положения (ст.ст. 1 — 15)». constitution.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ Закон Республики Карелия «О государственной поддержке карельского, вепсского и финского языков в Республике Карелия»

- ^ Law of the Republic of Bashkortostan «On the languages of the peoples of the Republic of Bashkortostan» № 216-W on February 15, 1999 (as amended up until 2010)) and amendments of 2014(in Russian)

- ^ Gabdrafikov I. The law «On the Languages of the peoples of the Republic of Bashkortostan» is adopted // Бюллетень Сети этнологического мониторинга и раннего предупреждения конфликтов, No. 23, 1999

- ^ Десять лет назад принят Закон «О языках народов Республики Башкортостан» ru:Башинформ 2009(in Russian)

- ^ «Закон РФ от 25.10.1991 N 1807-I «О языках народов Российской Федерации» (с изменениями и дополнениями) | ГАРАНТ». base.garant.ru. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ Страны, лидирующие по количеству прибытий на территорию Российской Федерации — Топ 50 по въезду в РФ за 2014 год (всего) [Countries leading by the number of arrivals to the territory of the Russian Federation — Top 50 by entry into the RF for 2014 (total)] (in Russian). RussiaTourism.ru. Archived from the original (XLS) on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ Yegorov, Oleg (25 May 2017). «Why was French spoken in Russia?». Russia Beyond the Headlines.

- ^ a b Percentage of Russian who speak English double to 30

- ^ «Статистическая информация 2014. Общее образование». Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

Further reading[edit]

- Offord, Derek, Lara Ryazanova-Clarke, Vladislav Rjéoutski, and Gesine Argent. French and Russian in Imperial Russia: Language Use among the Russian Elite. Edinburgh University Press, 2015. Available at JSTOR.

External links[edit]

- Languages of European Russia (Ethnologue)

- Languages of Asian Russia (Ethnologue)

- Minority languages of Russia on the Net project, which aims at presenting the languages of Russia to the Web and at facilitating their usage on the Web (most information is in Russian; it provides scientific references on each individual language as well as links to online language descriptions, educational and scientific institutions related to the language, resources on computer-processing of the language and some sites written in this language)

- Population by mother tongue and districts in 50 Governorates of the European Russia in 1897

- «The History of the French Language in Russia.» University of Bristol

Russia is home to diverse cultures, which are manifested in the high number of different languages used all over the country. The Russian language is the most popular in the country, with about 260 million speakers and is legally recognized as the country’s official language at the national. There are other 35 languages which are used as official languages in different regions of Russia. The country is also home to about 100 other minority languages. Russian is the language enshrined in the Constitution of Russia as the nation’s national language. Russian is also one of the most widespread languages in the world, with speakers in Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine, Latvia, Moldova, Estonia, Georgia Tajikistan, Lithuania, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, and Belarus. The Russian language is also used as an official language in the United Nations, and also a primary language used by internet users around the world. The Russian language in its written form uses its distinct alphabet with additional consonants and vowels, which are based on the Cyrillic script. The global population of Russian native speakers is estimated to be 260 million people, with the majority residing in the former Russian Federation. The Russian language is classified as an Indo-European language and is one of the four East Slavic languages. The Russian language spoken all over the country has not changed much, and is quite similar as it has been used for hundreds of years in the country. However, despite its rather homogenous nature, the language does have several dialects which are geographically defined. The most fundamental dichotomy of the language is in two distinct dialects, Northern and Southern, with the nation’s capital Moscow being the linguistic divide between the two. The Northern dialect is predominantly used along the Volga River. The Northern dialect is further subdivided into five other smaller sub-dialects which include the Vladimir dialect, Vlatka dialect, Novgorod dialect, Olonets dialect, and the Arkhangelsk dialect. A common characteristic found in the Northern dialects is that the unstressed syllables do not have typical vowel reduction. The Southern dialect is predominantly used in the Northern Caucasus, the lower regions of the Volga and Don, southern Siberia, and the south of Ural. The Southern dialect is comprised of four smaller sub-dialects which include the Smolensk dialect, Ryazan dialect, Tula dialect, as well as the Orel dialect. There are other lesser dialects which exist outside the two principal dialects, and these are the Sloboda dialect and the Steppe dialect. While the language exists in various dialects, the commonly used dialect is the standardized dialect used in the capital, Moscow. Some linguists categorize the Moscow dialect as the Central Russian dialect, as the region where it is predominantly used is located between the regions of the Northern dialect and the Southern dialect, and therefore is seen as a transition between the two major dialects. The Moscow dialect was originally used by affluent members of society and the urban population in Moscow until the 20th century, when the government encouraged the nationwide use of the dialect. The standardized dialect of the language is incorporated into the Russian national education curriculum and is the dialect taught to foreigners as a second language. The official use of the standardized dialect of the Russian language is regulated by the Russian Language Institute, which is based in the Russian Academy of Sciences, a government institution. Locally known as “Braille Script,” Russian Braille is a version of the standardized Russian language used nationwide in the country. Russian Braille uses the language’s alphabets which are based on Cyrillic characters. Russian Braille also includes numbers and other arithmetic symbols. Besides Russian, there are other numerous languages which have been adopted as the official languages in Russia. These languages include; Ossetic, Ukrainian, Buryat, Kalmyk, Chechen, Ingush, Abaza, Adyghe, Cherkess, Kabardian, Altai, Bashkir, Chuvash, Crimean Tatar, Karachay-Balkar, Khakas, Nogai, Tatar, Tuvan, Yakut, Erzya, Komi, Hill Mari, Meadow Mari, Moksha, and Udmurt. These languages have thousands of native speakers who make up a significant percentage of the total Russian population. The Adyghe language, also known as West Circassian, is an example as it has more than 128,000 native speakers in Russia and is the official language in the Republic of Adygea, although there are also other speakers of the language in other countries. The Abaza language is another example, and has over 35,000 native speakers in Russia and is officially recognized as the official language in the Karachay-Cherkessia Constituency. In the Republic of Bashkortostan, the Bashkir language is used as the official language, and this language has 1.2 million speakers nationally. The Buryat language is the Buryat Republic’s official language and has over 265,000 native speakers all over the country. Chuvash language is the official language in the Chuvashia Republic, where it has about 1.1 million native speakers. Chechen language is one of the biggest languages besides Russian in the country, as it has over 1.4 million native speakers in Russia. The language is used as the official language of the Republic of Chechnya. Like many Russian languages, the Chechen language features Cyrillic and Latin alphabets in its written format. The Ossetian language is an Eastern Iranian language adopted as the North Ossetia- Alania region and its number of native speakers is estimated to be about 570,000 people around the country. The Kalmyk language is legally recognized as the official language of Kalmykia and has about 80,000 native speakers in the republic. However, Kalmyk is in danger of extinction, and UNESCO labels the language as “definitely endangered.” Other languages that are in danger of extinction include Northern and Southern Yukaghir, Ter Sami, Udege, Enets, Orok, Seto, Ket, Ingrian, Chulym, Ludian, Chukchi, Veps, and Tofalar. Some languages have already been declared extinct in Russia, but might have small populations of native speakers in other countries in the world. Such languages include Ainu, Yugh, and Kerek. Russia is home to thousands of expatriates who might have verbal and written knowledge of the nation’s national language, but also use their native languages while communicating. The most dominant foreign languages in Russia include English, German, French, Turkish, and Ukrainian. The use of these foreign languages is usually restricted to the major cities of Russia. Russian Language: National Language of Russia

Russian Language: Dialects

Russian Language: Standardized Language

Russian Language: Braille

Other Official Languages Of Russia

Endangered Languages Of Russia

Foreign Languages Spoken in Russia

Sometimes we need to change something in our life. Our readers

remember that we had the rubric “Around Russia”, where I tried to give as much useful

information about the capital as possible. Today, when the format of our newspaper is

altered, the rubric will also be a bit changed. From now on we will speak not only about

Moscow, but also about the whole of Russia.

The first question I asked myself when I started thinking about

possible subjects to write about was the following: “What should I start with?”

Finally, I came to the decision that I’ll tell you about the different languages that

exist in Russia. My choice can be explained, first of all, by the fact that our newspaper

is all about language, and, secondly, just at the beginning of the new year, we will

mention the peoples who inhabit the territory of the Russian Federation. So, let us start!

As we all know, Russia is a multinational country, which means it is a

multilingual one. Linguists count about 150 different languages here, among which

scientists paid attention to all languages, starting with Russian, spoken by 97 per cent

of the population, and finishing with the language of a small community of 662 people

living near the Amur River.

Some languages are very similar: representatives of different peoples

can speak their own language and perfectly well understand each other. For example, a

Russian can talk to a Byelorussian, a Tatar to a Bashkir, a Kalmyk to a Buryat. Some

languages, despite the fact they have a lot in common, can not be so easily understood.

This is the case of a Mari and a Mordvinian, a Lezghin and an Avar. And, finally, there

are the so-called isolated languages, i.e. those which are completely different from all

others.

The majority of languages in Russia derive from one of four big

language families: Indo-European, Altaic, Uralic and Caucasian ones. Each language

family has its common ancestor language. Many centuries ago tribes, speaking the same

languages, were constantly moving to other territories, mixing with other ones, hence the

division of a language into several branches.

Russian, for example, belongs to the Indo-European group of

languages. There belong also such languages as English, German, Spanish and many

others. A part of this group unites Slavic languages – Bulgarian, Czech, Polish.

About 87 per cent of the population of Russia speaks languages of the

Indo-European group; only 2 per cent of them are not Slavic. Among them let us mention

German and Yiddish; Armenian (it makes a separate group alone); Iranian languages:

Ossetic, Kurdish, Tajik; Romanic languages: Moldavian; and even Newindian spoken by

Gipsies.

The Altaic group of languages is represented by three groups,

such as Turkic, Mongolian and Tungus-Manchurian. One of the Uralic group of languages

consists of the Finno-Ugric group. “Finno” has nothing to do with the state language

of Finland: languages forming this group simply have similar grammar and sounding. Among

peoples speaking the Finnish languages we could name Karelians, Komis, Maris, Udmurts,

Mordvinians, and Lapps.

As for the northern Caucasian language group, only specialists

are able to point out their origins and common roots. These languages have a very

complicated grammar and phonetics. There are sounds which do not exist in other languages.

One of the branches of the northern Caucasian group is the Daghestan

group, which includes, for example, the language of Avars, Lezghins and many other

peoples. Daghestan is often referred to as “a mountain of languages” and “a paradise

for linguists” as the field of work for them in this country is enormous.

There are some languages which do not belong to any of four above

mentioned groups. These are languages of peoples in Siberia and the Far East. All of them

are represented only by small tribal communities of speakers (Chukchis, Koryaks, Eskimos,

Aleutians).

No doubt, there are many different languages; but people still need a

common one. In Russia it is the Russian language, because Russians represent the majority

of the population in the country.

Of course, all languages are valuable, and we must do everything to

preserve them; but there is no possibility to publish all books in every language: still,

this can be done in the language spoken by millions.

Some peoples in Russia are, unfortunately, losing their mother tongue,

and the list of such nations is quite long. In our towns and cities Russian is becoming

more and more popular and very often the only one used. Nevertheless, there are national

cultural centres trying to do their best in order to save their identities.

Most peoples in Russia did not have any written languages at all till

the 1920s. Georgians, Armenians and Jews were an exception. Germans, Polish, Lithuanians,

Letts, Estonians, and Finns used the Latin alphabet. Some languages do not have any

written form even today.

The first attempt to create written languages for peoples in Russia

were undertaken before the Revolution. Starting from 1936 everyone in the country was

taught to write using the Slavonic alphabet, as it was believed that the common system

could assist in learning the Russian language quickly.

Questions to the Next Part:

1. How would you characterise the typical physical appearance of

Russians?

2. Where does the name ‘Russian’ come from?

3. Why is it difficult to give the precise number of Russians living in the country in the

18th century?

4. What was the policy of the Soviet government concerning their attitude towards

different nations?

5. What country did the word “sarafan” come from?

6. Why did married women have to wear headgears?

7. What were the most popular women’s headgear? When?

Compiled by Alevtina Kozina

We take a look at the Russian language, from its origins in medieval Eastern Europe to its fascinating grammatical structure.

The Russian language, as beautiful as Russia itself, is the medium in which some of history’s greatest writers and orators have crafted their works. Today, it is one of six languages with official status at the United Nations and is spoken by 258 million people.

Learning Russian will of course help you integrate. But it will also enable you to gain a deeper understanding of Russia’s unique history and culture. Our guide to the Russian language aims to furnish you with some key information on its origins and modern-day usage, including:

- What languages do people speak in Russia?

- Where the Russian language is spoken worldwide

- Belarus

- Ukraine

- Kazakhstan

- Germany

- United States

- Israel

- Origins and history of the Russian language

- The roots of the language

- Reform of the language

- A revolution in Russian

- Russian pronunciation and phonology

- Russian grammar

- Dialects of the Russian language

- Interesting facts about the Russian language

- Learning the Russian language in Russia

- Useful resources

Babbel

Babbel is a language learning app. They have a number of professionally-made courses covering language basics including vocabulary, pronunciation and more. With courses in 14 languages and counting, Babbel helps you improve your language skills when it suits your lifestyle.

What languages do people speak in Russia?

Russia is a vast and diverse country and is home to over a hundred languages. However, Russian is the only official language nationwide. It is spoken by over 142 million out of 144 million Russian citizens. Of these, 119 million say it is their first language.

A further 35 minority languages are recognized as official in their regions of origin. The largest of these include Tatar (5,3 million speakers), Bashkir (1,38 million), and Chechen (1,33 million).

Russia is also home to significant foreign-born communities, largely originating from the former USSR. As a result, languages such as Ukrainian, Uzbek, Kazakh, Armenian, and Georgian are frequently heard in major cities.

Finally, a significant number of Russians speak foreign languages. The second most widely spoken language in Russia is English, with almost 7 million speakers. German is the fifth most widely spoken language, with 2,9 million speakers. A tenth of these are native speakers.

Where the Russian language is spoken worldwide

Russian is an official language in four countries: Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Over 258 million people speak Russian worldwide, making it the eighth most-spoken language in the world. While over half of those speakers reside in Russia, large Russian-speaking communities can be found elsewhere too.

Belarus

Russian is one of the two official languages of Belarus, along with Belarusian. In the 2019 census, 38.1% of Belarusians named Russian as their native language.

Ukraine

Although it is not an official language in Ukraine, the Ukrainian constitution explicitly recognizes Russian as a minority language. It is the native tongue of 22% of Ukrainians, while 29% say they predominantly speak Russian at home.

Kazakhstan

Like Belarus, Kazakhstan grants Russian the status of official language, and around 3.8 million Russian speakers live in the former Soviet republic.

Germany

There are no official statistics as to the exact size of the Russian-speaking community in Germany. However, Russian is the second most spoken language in the country, with the number of speakers estimated between 2.2 million and 3.5 million.

United States

There is a sizeable Russian-speaking community in the United States – in 2016, over 900,000 Americans reported speaking predominantly Russian at home.

Israel

An estimated 1.3 million Israeli citizens speak Russian, making it the third most-spoken language in the country after Hebrew and Arabic.

In addition, there are also Russian speakers in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the Baltic states.

Origins and history of the Russian language

Russian is a member of the East Slavic subgroup of the Slavic language family, along with Belarusian and Ukrainian. Like almost all European languages, it has its roots in the wider Indo-European family.

The roots of the language

Around 880, the territory of modern Ukraine, Belarus, and west Russia was unified into Kyivan Rus’, and the East Slavs, who had previously spoken in a variety of closely related dialects, established Old East Slavic as a common language for the region.

Russian began to differentiate itself as a language following the breakup of Kyivan Rus’ in approximately 1100. It became a distinct language in the 13th century. The development of Russian was strongly influenced by Church Slavonic, which remained the official literary language in Moscow until the late 17th century.

Reform of the language

Reforms introduced by Tsar Peter the Great (1682–1725) aimed to secularize the language and reverse the influence of Church Slavonic. As part of Peter’s reforms, he also introduced blocks of specialized vocabulary adopted from languages of Western Europe. However, up until the Napoleonic Wars in the early 19th century, the Russian aristocracy preferred to speak French, with Russian being predominantly the language of the common people. To this day the Russian language contains a large number of French loanwords, such as кошмар (koshmar, from cauchemar, “nightmare”) and тротуар (trotuar, from trottoir, “sidewalk”).

The great poet Alexander Pushkin revolutionized the written Russian language in the early 19th century. Pushkin rejected the archaic written grammar and vocabulary in favor of that used in the common vernacular of the time.

This made his work more accessible to his contemporaries. Russians revere Pushkin as the father of modern Russian, similar to how English speakers view Shakespeare, and his writing remains popular today.

A revolution in Russian

The most recent stage in the evolution of the Russian language came shortly after the Bolshevik Revolution, with the spelling reforms of 1918. Reforms introduced by the new Soviet government aimed to simplify Russian writing. Most notably, they dropped four letters from the alphabet. In addition, they abandoned the use of the Cyrillic hard sign (ъ) following consonants at the end of words. The latter change had the added effect of reducing the costs of typesetting and writing by about one-thirtieth.

Russian pronunciation and phonology

The Russian language alphabet is a variation of Cyrillic script. It has 33 letters, including 20 consonants, 10 vowels, one semivowel («й», which is similar to the letter “y” in English), and two unvoiced modifiers, or “signs”. The latter alters the pronunciation of a preceding consonant and/or following vowel within a word.

Five letters of the Russian alphabet – three consonants («к», «м», and «т») and two vowels («а» and «о») – look similar or identical to their English equivalents. Others resemble letters in Latin script but are pronounced differently. These include «х» (pronounced “kh”) and «у» (“u”).

Word stress is very important in Russian and is one of the things that most distinguishes it from other languages. Every word has only one stressed vowel, pronounced distinctly, whereas Russian speakers shorten other vowels within the word. Normally, the second-to-last vowel within a word is stressed. However, this is not a universal rule.

Fortunately, once you get the hang of the alphabet and word stress, Russian is almost entirely phonetic, with just a handful of exceptions. For example, the letter «г», which is usually pronounced “g”, becomes an “h” sound when immediately followed by the letter «к».

Russian grammar

In Russian, every noun is either masculine, feminine, or neuter. Verbs and adjectives have different endings based on gender, case, and singular/plural.

Unlike English and German, the Russian language has no formal word order. The subject, object(s), and so on are recognizable through case endings, rather than through their position within a sentence. Russian has six cases:

- Nominative – shows the subject of an action.

- Accusative – shows the direct object of an action.

- Prepositional – shows the location where an action takes place.

- Genitive – denotes possession, and is also often used in a negation.

- Dative – shows the indirect object of an action.

- Instrumental – shows how an action takes place.

Although Russian has a verb “to be”, rarely used in the present tense. In addition, Russian has no articles. Thus, an English sentence like “I am a student” becomes “I student” in Russian.

Dialects of the Russian language

There is surprisingly little variation in how Russian is spoken, despite the size of the country. Regardless of their location, Russians tend to speak standard Russian, with only very minor regional variations. For example, in the northern territories of European Russia, people often stress multiple syllables within a word. This differs from standard Russian pronunciation.

There is more variation among other Russian-speaking peoples. Ukrainians, for example, tend to pronounce the Russian letter “g” as an “h” sound, which is also how the letter sounds in the Ukrainian language.

Chechens often pronounce the letter “v” as a “w”, as many native German speakers do when speaking English.

Many Russian-speaking Israelis speak a dialect called “Rusit”, which contains a large number of Hebrew loanwords and unique expressions not found in standard Russian.

Interesting facts about the Russian language

You are probably familiar with some Russian loanwords in English, such as vodka and tsar, but there are many others. For example, mammoth, balaclava, and tundra all derive from Russian.

Along with English, Russian is one of the official languages of space. Astronauts have to learn Russian as part of their training, and computers on the International Space Station use both English and Russian. Around 7.4% of all online content is in Russian.

The name Red Square (Красная Площадь, Krasnaya Ploshchad) has no connection with communism or the USSR. The word for “red” actually derives from an archaic Russian word meaning “beautiful”. There is also no single word for the color blue in the Russian language. Instead, it has numerous words for different shades of blue, the most common being голубой (goluboy, light blue) and синий (siniy, dark blue).

And, lastly, the word царь (tsar) derives from the Latin “Caesar”, which means hairy.

Learning the Russian language in Russia

If you are planning to move to Russia, learning Russian should be near the top of your to-do list. According to a 2019 poll, only 5% of Russians speak fluent English, so learning Russian will make it much easier to communicate.

Most jobs in Russia will require you to speak at least basic Russian. If you intend to seek Russian citizenship by naturalization, you will need to provide proof you can speak the language.

Fortunately, you have plenty of options.

If you thrive in a classroom environment, you could enroll in one of the many language schools dotted around the country.

Alternatively, there are numerous smartphone apps and computer programs available to help you learn Russian, including:

- Babbel

- italki

Finally, you may want to seek out a language exchange partner – a Russian native speaker who will help you practice your Russian in exchange for helping them practice speaking your native language.

Useful resources

- Multitran – an in-depth online Russian dictionary containing both general and specialized vocabulary and idiomatic phrases.

- Translit – a virtual Cyrillic keyboard with the ability to search for phrases on Google, YouTube, Wikipedia, and other popular websites.

- Gramota – a Russian government-funded online resource for learning Russian grammar and vocabulary.

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions. - Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!