Scientists believe that the ethnonym «Kazakh» comes from the name of the clans — «Sak», «Kas-Pi», «Kas», «Kaz», «Khaz», «Az», and «Ka-Sak». Academician N. Marra and Czech scholar B. Grozny assume that the term originates from the words «kasak» and «kesek». This opinion is supported by academician A. Margulan, historian M. Akhinzhanov, writer S. Mukanov and Russian scholars. A. Margulan refers to the fact that the Junior Zhuz still includes the small tribes «Kazar-Ug».

Ethnologist A. Abdrakhmanov supposes that the word «Kazakh» comes from the two words — «kaz» and «og» («ok»). «Og» means «clan, tribe» in ancient Turkic language. This word is a basis for collective name of the ethnic name «Oguz». In this case, «kaz-og» means «tribes of the Kazakhs».

Russian scholar A. Bernshtam who conducted a long study on the history of the Kazakhs made a comparison between the data of archaeological excavations and written texts and came to a conclusion that the word «Kazakh» comes from the combination of names of the Caspian and Scythian tribes.

Chinese historian Ban Gu who lived in the 2nd century B. C. wrote that there was the ethnic group «Se», or «Sai», among other Central Asian people that defeated the Greco-Bactrian state. The description of some details shows that he wrote about the Scythian tribes. Orientalist V. Grigoriev proves that «Se», or «Sai’, means «Scythians» in Chinese. And the scientist notes that the ethnic group came not from some removed parts of Mongolia but from the East where it was residing the banks of the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya.

V. Radlov, a famous scientist and expert in Turkic language, believed that the word «Kazakh» meant «free and independent man». This opinion was shared by A. Samoilovich. Sh. Kudaiberdiyev also supported this idea and added that «Kazakh» meant «free and independent people who established their free state».

Kazakh scientist Ch. Valikhanov wrote that «Kazakh» was a very respectful and sacred word meaning «powerful, strong, and inspired». Fazlullah ibn Ruzbihan, one of the greatest Iranian political thinkers, in his notes dating to the 16th century provided the following evidence: «The Kazakhs became known thanks to their courage, heroism, and great power.» Linguist T. Zhanuzakov proves that the first part of the word, «kaz» or «kas» means «free», «brave», and «man» in all Turkic languages. And the second part — «ak», implies that the term is collective.

Thus, there are two main conclusions:

— the word «Kazakh» comes from the names of tribes — «kas» («kaspi») and «sak»;

— the word «Kazakh» means «a free man».

By Miras NURLANULY

Use of materials for publication, commercial use, or distribution requires written or oral permission

from the Board of Editors or the author.

Hyperlink to Qazaqstan tarihy portal is necessary. All rights reserved by the Law RK “On author’s rights

and related rights”.

To request authorization email to

or call to 8 (7172) 57 14 08 (in

— 1164)

Not to be confused with Cossacks.

|

қазақтар |

|

|---|---|

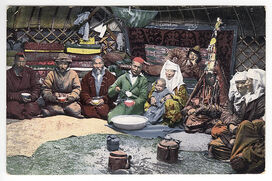

Kazakhs in traditional attire |

|

| Total population | |

| c. 16 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 13,012,645[1] | |

| 1,562,518[2] | |

| 803,400[3] | |

| 647,732[4] | |

| 102,526[5] | |

| 33,200[6] | |

| 24,636[7] | |

| 10,000[8] | |

| 9,600[9] | |

| 3,000–15,000[10][11] | |

| 5,639[12] | |

| 5,526[13] | |

| 5,432[14] | |

| 5,000[15] | |

| 1,924[16] | |

| 2,310[17] | |

| 1,685[18] | |

| 1,355[19] | |

| 1,000[20] | |

| 633[21] | |

| 200[22] | |

| 178–215[23] | |

| Languages | |

| Kazakh, Russian[citation needed] | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam[24] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Turkic peoples (especially Kyrgyz, Nogai and Karakalpaks), as well as Bashkirs. |

The Kazakhs (also spelled Qazaqs; Kazakh: sg. қазақ, qazaq, [qɑˈzɑq] (listen), pl. қазақтар, qazaqtar, [qɑzɑqˈtɑr] (

listen)) are a Turkic people native to Central Asia and Eastern Europe, mainly Kazakhstan, but also parts of northern Uzbekistan and the border regions of Russia, as well as northwestern China (specifically Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture) and western Mongolia (Bayan-Ölgii Province). The Kazakhs are descendants of the ancient Turkic Kipchak tribes and the later Kazakh Khanate.[25][26]

Kazakh identity is of medieval origin and was strongly shaped by the foundation of the Kazakh Khanate between 1456 and 1465, when following disintegration of the Golden Horde, several tribes under the rule of the sultans Janibek and Kerei departed from the Khanate of Abu’l-Khayr Khan in hopes of forming a powerful khanate of their own.

Kazakh is used to refer to ethnic Kazakhs, while the term Kazakhstani usually refers to all inhabitants or citizens of Kazakhstan, regardless of ethnicity.[27][28]

Etymology

The Kazakhs likely began using that name during the 15th century.[29] There are many theories on the origin of the word Kazakh or Qazaq. Some speculate that it comes from the Turkic verb qaz («wanderer, brigand, vagabond, warrior, free, independent») or that it derives from the Proto-Turkic word *khasaq (a wheeled cart used by the Kazakhs to transport their yurts and belongings).[30][31]

Another theory on the origin of the word Kazakh (originally Qazaq) is that it comes from the ancient Turkic word qazğaq, first mentioned on the 8th century Turkic monument of Uyuk-Turan.[32] According to Turkic linguist Vasily Radlov and Orientalist Veniamin Yudin, the noun qazğaq derives from the same root as the verb qazğan («to obtain», «to gain»). Therefore, qazğaq defines a type of person who wanders and seeks gain.[33]

History

Throughout history, Kazakhstan has been home to many nomadic societies of the Eurasian Steppe, including the Sakas (Scythian-related), the Xiongnu, the Western Turkic Khaganate, the Mongol Empire, the Golden Horde and the Kazakh Khanate, which was established in 1465.[34]

Kazakh was a common term throughout medieval Central Asia, generally with regard to individuals or groups who had taken or achieved independence from a figure of authority. Timur described his own youth without direct authority as his Qazaqliq («freedom», «Qazaq-ness»).[35]

Kazakh eagle-hunter, 19th century

In Turko-Persian sources, the term Özbek-Qazaq first appeared during the middle of the 16th century, in the Tarikh-i-Rashidi by Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat, a Chagatayid prince of Kashmir. In this manuscript, the author locates Kazakh in the eastern part of Desht-i Qipchaq. According to Tarikh-i-Rashidi, the first Kazakh union was created c. 1465/1466 AD. The state was formed by nomads who settled along the border of Moghulistan, and was called Uzbeg-Kazák.[36]

At the time of the Uzbek conquest of Central Asia, Abu’l-Khayr Khan, a descendant of Shiban, had disagreements with the Kazakh sultans Kerei and Janibek, descendants of Urus Khan. These disagreements probably resulted from the crushing defeat of Abu’l-Khayr Khan at the hands of the Kalmyks.[37] Kerei and Janibek moved with a large following of nomads to the region of Zhetysu on the border of Moghulistan and set up new pastures there with the blessing of the Chagatayid khan of Moghulistan, Esen Buqa II, who hoped for a buffer zone of protection against the expansion of the Oirats.[38]

Regarding these events, Haidar Dughlat in his Tarikh-i-Rashidi reports:[39]

At that time, Abulkhair Khan exercised full power in Dasht-i-Kipchak. He had been at war with the Sultánis of Juji; while Jáni Beg Khán and Karáy Khán fled before him into Moghulistán. Isán Bughá Khán received them with great honor, and delivered over to them Kuzi Báshi, which is near Chu, on the western limit of Moghulistán, where they dwelt in peace and content. On the death of Abulkhair Khán the Ulus of the Uzbegs fell into confusion, and constant strife arose among them. Most of them joined the party of Karáy Khán and Jáni Beg Khán. They numbered about 200,000 persons, and received the name of Uzbeg-Kazák. The Kazák Sultáns began to reign in the year 870 [1465–1466] (but God knows best), and they continued to enjoy absolute power in the greater part of Uzbegistán, till the year 940

[1533–1534 A. D.].

In the 17th century, Russian convention seeking to distinguish the Qazaqs of the steppes from the Cossacks of the Imperial Russian Army suggested spelling the final consonant with «kh» instead of «q» or «k», which was officially adopted by the USSR in 1936.[40]

- Kazakh — Казах

- Cossack — Казак

The Ukrainian term Cossack probably comes from the same Kipchak etymological root, meaning wanderer, brigand, or independent free-booter.[41][42]

Oral history

Like many people who live a nomadic lifestyle, Kazakhs keep an epic tradition of oral history which goes back centuries. It is most commonly relayed in the form of song (kyi) and poetry (zhyr), which typically tell the stories of Kazakh national heroes.[43]

The Kazakh oral tradition has long been used for propagandistic purposes. The highly influential Kazakh poet Abai Qunanbaiuly viewed it as the ideal way to transmit the pro-Westernization ideals of his colleages. The Kazakh oral tradition has also overlapped with ethnic nationalism, and has been appropriated for decolonialist educational purposes since the collapse of the Soviet Union.[43][44][45]

Three Kazakh Juz (Hordes)

Main article: Zhuz

Approximate areas occupied by the three Kazakh jüz in the early 20th century.

In modern Kazakhstan, tribalism is fading away in business and government life. However, it is still common for Kazakhs to ask each other about the tribe they belong to when they become acquainted with one another. Now, it is more of a tradition than a necessity, and there is no hostility between tribes. Kazakhs, regardless of their tribal origin, consider themselves one nation.

Those modern-day Kazakhs who yet remember their tribes know that their tribes belong to one of the three Zhuz (juz, roughly translatable as «horde» or «hundred»):

- The Senior Horde (also called Elder or Great) (Uly juz)

- The Middle (also called Central) (Orta juz)

- The Junior (also called Younger or Lesser) (Kishi juz)

History of the Hordes

There is much debate surrounding the origins of the Hordes. Their age is unknown so far in extant historical texts, with the earliest mentions in the 17th century. The Turkologist Velyaminov-Zernov believed that it was the capture of the important cities of Tashkent, Yasi, and Sayram in 1598 by Tevvekel (Tauekel/Tavakkul) Khan that separated the Qazaqs, as they possessed the cities for only part of the 17th century.[46] The theory suggests that the Qazaqs then divided among a wider territory after expanding from Zhetysu into most of the Dasht-i Qipchaq, with a focus on the trade available through the cities of the middle Syr Darya, to which Sayram and Yasi belonged. The Junior juz originated from the Nogais of the Nogai Horde.

Language

Distribution of the Kazakh language

The Kazakh language is a member of the Turkic language family, as are Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Tatar, Uyghur, Turkmen, modern Turkish, Azeri and many other living and historical languages spoken in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, Xinjiang, and Siberia.

Kazakh belongs to the Kipchak (Northwestern) group of the Turkic language family. Kazakh is characterized, in distinction to other Turkic languages, by the presence of /s/ in place of reconstructed proto-Turkic */ʃ/ and /ʃ/ in place of */tʃ/; furthermore, Kazakh has /d͡ʒ/ where other Turkic languages have /j/.

Kazakh, like most of the Turkic language family lacks phonemic vowel length, and as such there is no distinction between long and short vowels.

Kazakh was written with the Arabic script until the mid-19th century, when a number of educated Kazakh poets from Muslim madrasahs incited a revolt against Russia. Russia’s response was to set up secular schools and devise a way of writing Kazakh with the Cyrillic alphabet, which was not widely accepted. By 1917, the Arabic script for Kazakh was reintroduced, even in schools and local government.

In 1927, a Kazakh nationalist movement sprang up against the Soviet Union but was soon suppressed. As a result, the Arabic script for writing Kazakh was banned and the Latin alphabet was imposed as a new writing system. In an effort to Russianize the Kazakhs, the Latin alphabet was in turn replaced by the Cyrillic alphabet in 1940 by Soviet interventionists. Today, there are efforts to return to the Latin script.

Kazakh is a state (official) language in Kazakhstan. It is also spoken in the Ili region of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the People’s Republic of China, where the Arabic script is used, and in western parts of Mongolia (Bayan-Ölgii and Khovd province), where Cyrillic script is in use. European Kazakhs use the Latin alphabet.

Religion

In the late 14th century, the Golden Horde propagated Islam in its state. Islam in Kazakhstan peaked during the era of the Kazakh Khanate, especially under rulers such as Ablai Khan and Kasym Khan. Another wave of conversions among the Kazakhs occurred during the 15th and 16th centuries via the efforts of Sufi orders.[47] During the 18th century, Russian influence toward the region rapidly increased throughout Central Asia. Led by Catherine, the Russians initially demonstrated a willingness in allowing Islam to flourish as Muslim clerics were invited into the region to preach to the Kazakhs, whom the Russians viewed as «savages» and «ignorant» of morals and ethics.[48][49] However, Russian policy gradually changed toward weakening Islam by introducing pre-Islamic elements of collective consciousness.[50] Such attempts included methods of eulogizing pre-Islamic historical figures and imposing a sense of inferiority by sending Kazakhs to highly elite Russian military institutions.[50] In response, Kazakh religious leaders attempted to bring in pan-Turkism, though many were persecuted as a result.[51] During the Soviet era, Muslim institutions survived only in areas that Kazakhs significantly outnumbered non-Muslims, such as non-indigenous Russians, by everyday Muslim practices.[52] In an attempt to conform Kazakhs into Communist ideologies, gender relations and other aspects of Kazakh culture were key targets of social change.[49]

In more recent times, however, Kazakhs have gradually employed a determined effort in revitalizing Islamic religious institutions after the fall of the Soviet Union. Most Kazakhs continue to identify with their Islamic faith,[53] and even more devotedly in the countryside. Those who claim descent from the original Muslim soldiers and missionaries of the 8th-century command substantial respect in their communities.[54] Kazakh political figures have also stressed the need to sponsor Islamic awareness. For example, the Kazakh Foreign Affairs Minister, Marat Tazhin, recently emphasized that Kazakhstan attaches importance to the use of «positive potential Islam, learning of its history, culture and heritage.»[55]

Pre-Islamic beliefs, such as worship of the sky, the ancestors, and fire, continued to a great extent to be preserved among the common people, however. Kazakhs believed in the supernatural forces of good and evil spirits, of wood goblins and giants. To protect themselves from them and from the evil eye, Kazakhs wore protection beads and talismans. Shamanic beliefs are still widely preserved among Kazakhs, as well as the belief in the strength of the bearers of that worship, the shamans, which Kazakhs call bakhsy. Unlike the Siberian shamans, who used drums during their rituals, Kazakh shamans, who could also be men or women, played (with a bow) on a stringed instrument similar to a large violin. At present both Islamic and pre-Islamic beliefs continue to be found among Kazakhs, especially among the elderly. According to 2009 national census 39,172 ethnic Kazakhs are Christians (0.0038% of all Kazakhstani Kazakhs).[56]

Origin and ethnogenesis

Kazakhs are a Turkic-speaking ethnic group, who formed from various nomadic tribes and clans, sharing a common lifestyle. The region, once inhabited by Indo-European, specifically Iranian peoples such as the Saka, Turkic peoples largely assimilated and replaced the previous population, giving rise to various Stepper entities, such as the First Turkic Khaganate or the Kipchak Khaganate, which was later conquered by Mongolic peoples and integrated into the Mongol empire. Subsequently, the ancestors of Kazakhs belonged to the Golden Horde, a Turco-Mongol state, which would later disintegrate and give rise to the Kazakh Khanate, in which the final ethnogenesis of Kazakhs took place. There was also some secondary Han Chinese influence through the Tang dynasty in Inner Asia, with the Turkic tribes being vassals of Tang China, declaring the Chinese emperor to be the Heavenly Khaghan of Turks.[57][58][59][60][61]

The exact place of origins of the Turkic peoples has been a topic of much discussion. Their homeland may have been in Southern Siberia, specifically the Altai-Sayan region. Early and medieval Turkic groups exhibited a wide range of both East Asian and West-Eurasian physical appearances and genetic origins, in part through long-term contact with neighboring peoples such as Iranian, Mongolic, Tocharian, Yeniseian people, and others.[62][63]

The Kazakhs emerged as an ethno-linguistic group during the early 15th century from a confederation of several, mostly Turkic-speaking pastoral nomadic groups of Northern Central Asia. The Kazakhs are the most northerly of the Central Asian peoples, inhabiting a large expanse of territory in northern Central Asia and southern Siberia known as the Kazakh Steppe. The tribal groups formed a powerful confederation that grew wealthy on the trade passing through the steppe lands along the fabled Silk Road.[64]

Genetic studies

Population structure of Turkic-speaking populations in the context of their geographic neighbors across Eurasia.[65]

Genomic research confirmed that Kazakhs originated from the admixture of several tribes.[59][66][67] Kazakhs have predominantly East Asian ancestry, and harbor two East Asian-derived components, one dominant component commonly found among Northeastern Asian populations (associated with the Northeast Asian «Devil’s Gate_N» sample from the Amur region), and another minor component associated with historical Yellow River farmers, peaking among Han Chinese. According to one study, West-Eurasian related admixture among Kazakhs is estimated at 35% to 37.5% in two Kazakh populations.[68] Another study estimated a lower average Western admixture of slightly less than 30%.[69][70] These results are inline with historical demographic information on northern Central Asia.[71] Neighboring Karakalpaks, Kyrgyz, Tubalar, and the Xinjiang Ölöd tribe, have the strongest resemblance to the Kazakh genome.[72]

A study on allele frequency and genetic polymorphism by Katsuyama et al., found that Kazakhs cluster together with Japanese people, Hui people, Han Chinese, and Uyghurs in contrast to West-Eurasian reference groups.[73]

A 2020 genetic study on the Kazakh genome, by Seidualy et al., found that the Kazakh people formed from highly mixed historical Central Asian populations. Ethnic Kazakhs were modeled to derive about ~63.2% ancestry from an East Asian-related population, specifically from a Northeast Asian source sample (Devil’s Gate 1), ~30.8% ancestry from European-related populations (presumably from Scythians), and ~6% ancestry from a broadly South Asian population. Overall, Kazakhs show their closest genetic affinity with other Central Asian populations, namely, Kalmyk, Karakalpak and Kyrgyz people, but also Mongolians. MSMC analyses suggest that the main ancestral lineage of Kazakhs split from Mongolians and other Northeast Asians about 7,000 years ago, while their divergence from Koryaks was estimated to be 10,000 years ago.[74]

Maternal lineages

According to mitochondrial DNA studies[75] (where sample consisted of only 246 individuals), the main maternal lineages of Kazakhs are: D (17.9%), C (16%), G (16%), A (3.25%), F (2.44%) of East-Eurasian origin (55%), and haplogroups H (14.1), T (5.5), J (3.6%), K (2.6%), U5 (3%), and others (12.2%) of West-Eurasian origin (41%).

Gokcumen et al. (2008) tested the mtDNA of a total of 237 Kazakhs from Altai Republic and found that they belonged to the following haplogroups: D(xD5) (15.6%), C (10.5%), F1 (6.8%), B4 (5.1%), G2a (4.6%), A (4.2%), B5 (4.2%), M(xC, Z, M8a, D, G, M7, M9a, M13) (3.0%), D5 (2.1%), G2(xG2a) (2.1%), G4 (1.7%), N9a (1.7%), G(xG2, G4) (0.8%), M7 (0.8%), M13 (0.8%), Y1 (0.8%), Z (0.4%), M8a (0.4%), M9a (0.4%), and F2 (0.4%) for a total of 66.7% mtDNA of Eastern Eurasian origin or affinity and H (10.5%), U(xU1, U3, U4, U5) (3.4%), J (3.0%), N1a (3.0%), R(xB4, B5, F1, F2, T, J, U, HV) (3.0%), I (2.1%), U5 (2.1%), T (1.7%), U4 (1.3%), U1 (0.8%), K (0.8%), N1b (0.4%), W (0.4%), U3 (0.4%), and HV (0.4%) for a total of 33.3% mtDNA of West-Eurasian origin or affinity.[76] Comparing their samples of Kazakhs from Altai Republic with samples of Kazakhs from Kazakhstan and Kazakhs from Xinjiang, the authors have noted that «haplogroups A, B, C, D, F1, G2a, H, and M were present in all of them, suggesting that these lineages represent the common maternal gene pool from which these different Kazakh populations emerged.»[76]

In every sample of Kazakhs, D (predominantly northern East Asian, such as Japanese, Okinawan, Korean, Manchu, Mongol, Han Chinese, Tibetan, etc., but also having several branches among indigenous peoples of the Americas) is the most frequently observed haplogroup (with nearly all of those Kazakhs belonging to the D4 subclade), and the second-most frequent haplogroup is either H (predominantly European) or C (predominantly indigenous Siberian, though some branches are present in the Americas, East Asia, and eastern and northern Europe).[76]

Paternal lineages

In a sample of 54 Kazakhs and 119 Altaian Kazakh, the main paternal lineages of Kazakhs are: C (66.7% and 59.5%), O (9% and 26%), N (2% and 0%), J (4% and 0%), R (9% and 1%) respectively.[77]

Population

| 1897 | 1917 | 1926 | 1939 | 1959 | 1979 | 1989 | 1999 | 2009 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 81.7% | 58.0% | 58.5% | 37.8% | 29.8% | 36.2% | 37.8% | 53.5% | 63.1% | 67.5% |

Historical population of Kazakhs:

Huge drop in population of Ethnic Kazakhs between 1897 and 1959 years caused by colonial politics of Russian Empire, then genocide

which occurred during Stalin Regime. Sarah Cameron (Associate Professor of University of Maryland) described this genocide on her book, «The Hungry Steppe: Famine, Violence, and the Making of Soviet Kazakhstan».

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1897 | 3,392,700 |

| 1917 | 3,615,000 |

| 1926 | 3,627,612 |

| 1939 | 2,327,625 |

| 1959 | 2,794,966 |

| 1979 | 5,289,349 |

| 1989 | 6,227,549 |

| 1999 | 8,011,452 |

| 2009 | 10,096,763 |

| 2018 | 12,212,645 |

Kazakh minorities

Russia

Muhammad Salyk Babazhanov – Kazakh anthropologist, a member of Russian Geographical Society.

In Russia, the Kazakh population lives primarily in the regions bordering Kazakhstan. According to latest census (2002) there are 654,000 Kazakhs in Russia, most of whom are in the Astrakhan, Volgograd, Saratov, Samara, Orenburg, Chelyabinsk, Kurgan, Tyumen, Omsk, Novosibirsk, Altai Krai and Altai Republic regions. Though ethnically Kazakh, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, those people acquired Russian citizenship.

| 1939 | % | 1959 | % | 1970 | % | 1979 | % | 1989 | % | 2002 | % | 2010 | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 356 646 | 0.33 | 382 431 | 0.33 | 477 820 | 0.37 | 518 060 | 0.38 | 635 865 | 0.43 | 653 962 | 0.45 | 647 732 | 0.45 |

China

Kazakhs migrated into Dzungaria in the 18th century after the Dzungar genocide resulted in the native Buddhist Dzungar Oirat population being massacred.

Kazakhs, called «哈萨克族» in Chinese (pinyin: Hāsàkè Zú; lit. ‘»Kazakh people» or «Kazakh tribe»‘) are among 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by the People’s Republic of China. According to the census data of 2010, Kazakhs had a population of 1.462 million, ranking 17th among all ethnic groups in China. Thousands of Kazakhs fled to China during the 1932–1933 famine in Kazakhstan.

In 1936, after Sheng Shicai expelled 30,000 Kazakhs from Xinjiang to Qinghai, Hui led by General Ma Bufang massacred their fellow Muslim Kazakhs, until there were 135 of them left.[79][80][81]

From Northern Xinjiang over 7,000 Kazakhs fled to the Tibetan-Qinghai plateau region via Gansu and were wreaking massive havoc so Ma Bufang solved the problem by relegating Kazakhs to designated pastureland in Qinghai, but Hui, Tibetans, and Kazakhs in the region continued to clash against each other.[when?][82] Tibetans attacked and fought against the Kazakhs as they entered Tibet via Gansu and Qinghai.[citation needed][when?] In northern Tibet, Kazakhs clashed with Tibetan soldiers, and the Kazakhs were sent to Ladakh.[when?][83] Tibetan troops robbed and killed Kazakhs 640 kilometres (400 miles) east of Lhasa at Chamdo when the Kazakhs were entering Tibet.[when?][84][85]

In 1934, 1935, and from 1936 to 1938 Qumil Elisqan led approximately 18,000 Kerey Kazakhs to migrate to Gansu, entering Gansu and Qinghai.[86]

In China there is one Kazakh autonomous prefecture, the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and three Kazakh autonomous counties: Aksai Kazakh Autonomous County in Gansu, Barkol Kazakh Autonomous County and Mori Kazakh Autonomous County in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.[citation needed]

At least one million Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other ethnic Muslims in Xinjiang have been detained in mass detention camps, termed «reeducation camps», aimed at changing the political thinking of detainees, their identities, and their religious beliefs.[87][88][89]

Mongolia

In the 19th century, the advance of the Russian Empire troops pushed Kazakhs to neighboring countries. In around 1860, part of the Middle Jüz Kazakhs came to Mongolia and were allowed to settle down in Bayan-Ölgii, Western Mongolia and for most of the 20th century they remained an isolated, tightly knit community.

Ethnic Kazakhs (so-called Altaic Kazakhs or Altai-Kazakhs) live predominantly in Western Mongolia in Bayan-Ölgii Province (88.7% of the total population) and Khovd Province (11.5% of the total population, living primarily in Khovd city, Khovd sum and Buyant sum). In addition, a number of Kazakh communities can be found in various cities and towns spread throughout the country. Some of the major population centers with a significant Kazakh presence include Ulaanbaatar 90% in khoroo #4 of Nalaikh düüreg,[90] Töv and Selenge provinces, Erdenet, Darkhan, Bulgan, Sharyngol (17.1% of population total)[91] and Berkh cities.

| 1956 | % | 1963 | % | 1969 | % | 1979 | % | 1989 | % | 2000 | % | 2010[5] | % | 2020[93] | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36,729 | 4.34 | 47,735 | 4.69 | 62,812 | 5.29 | 84,305 | 5.48 | 120,506 | 6.06 | 102,983 | 4.35 | 101,526 | 3.69 | 121,000 | 3.81 |

Uzbekistan

As of the beginning of 2021, more than 821000 ethnic Kazakhs lived in Uzbekistan.[94]

Iran

During the Qajar period, Iran bought Kazakh slaves who were falsely masqueraded as Kalmyks by slave dealers from the Khiva and Turkmens.[95][96]

Kazakhs of the Aday tribe inhabited the border regions of the Russian Empire with Iran since the 18th century. The Kazakhs made up 20% of the population of the Trans-Caspian region according to the 1897 census. As a result of the Kazakhs’ rebellion against the Russian Empire in 1870, a significant number of Kazakhs became refugees in Iran.

Iranian Kazakhs live mainly in Golestan Province in northern Iran.[97] According to ethnologue.org, in 1982 there were 3000 Kazakhs living in the city of Gorgan.[98][99] Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the number of Kazakhs in Iran decreased because of emigration to their historical motherland.[100]

Afghanistan

Kazakhs fled to Afghanistan in the 1930s escaping Bolshevik persecution. Kazakh historian Gulnar Mendikulova cites that there were between 20,000 and 24,000 Kazakhs in Afghanistan as of 1978. Some assimilated locally and cannot speak the Kazakh language.[22]

As of 2021, there are about 200 Kazakhs remaining in Afghanistan according to Kazakhstan’s foreign ministry. Locals claim that many live in Kunduz and others in Takhar Province, Baghlan Province, Mazar-i-Sharif and Kabul.[22]

Afghan Kypchaks are Aimak (Taymani) tribe of Kazakh origin that can be found in Obe District to the east of the western Afghan province of Herat, between the rivers Farāh Rud and Hari Rud. There are approximately 440,000 Afghan Kipchaks.

Turkey

Turkey received refugees from among the Pakistan-based Kazakhs, Turkmen, Kirghiz, and Uzbeks numbering 3,800 originally from Afghanistan during the Soviet–Afghan War.[101] Kayseri, Van, Amasya, Çiçekdağ, Gaziantep, Tokat, Urfa, and Serinyol received via Adana the Pakistan-based Kazakh, Turkmen, Kirghiz, and Uzbek refugees numbering 3,800 with UNHCR assistance.[102]

In 1954 and 1969 Kazakhs migrated into Anatolia’s Salihli, Develi and Altay regions.[103] Turkey became home to refugee Kazakhs.[104]

The Kazakh Turks Foundation (Kazak Türkleri Vakfı) is an organization of Kazakhs in Turkey.[105]

Culture

Music

One of the most commonly used traditional musical instruments of the Kazakhs is the dombra, a plucked lute with two strings. It is often used to accompany solo or group singing. Another popular instrument is kobyz, a bow instrument played on the knees. Along with other instruments, both instruments play a key role in the traditional Kazakh orchestra. A notable composer is Kurmangazy, who lived in the 19th century. After studying in Moscow, Gaziza Zhubanova became the first woman classical composer in Kazakhstan, whose compositions reflect Kazakh history and folklore. A notable singer of the Soviet epoch is Roza Rymbaeva, she was a star of the trans-Soviet-Union scale. A notable Kazakh rock band is Urker, performing in the genre of ethno-rock, which synthesises rock music with the traditional Kazakh music.

Notable Kazakhs

See also

- Chala Kazakh

- Kazakh Americans

- Kazakh Canadians

- Kazakhs in Russia

- Turkic peoples

- List of Kazakhs

- Ethnic demography of Kazakhstan

References

- ^ «Агентство Республики Казахстан по статистике. Этнодемографический сборник Республики Казахстан 2014». Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ^ «Main Data of the Seventh National Population Census». Stats.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ «DEMOGRAPHIC SITUATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN». Archived from the original on 22 August 2018.

- ^ «Russia National Census 2010». Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ a b Mongolia National Census 2010 Provision Results. National Statistical Office of Mongolia Archived 15 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Mongolian.)

- ^ In 2009 National Statistical Committee of Kyrgyzstan. National Census 2009 Archived 8 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Place of birth for the foreign-born population in the United States, Universe: Foreign-born population excluding population born at sea, 2014 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates». United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ «Казахское общество Турции готово стать объединительным мостом в крепнущей дружбе двух братских народов – лидер общины Камиль Джезер». 26 October 2009. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ «2011 National Household Survey: Data tables». 8 May 2013. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ «Казахи «ядерного» Ирана». Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ ««Казахи доказали, что являются неотъемлемой частью иранского общества и могут служить одним из мостов, связующих две страны» – представитель диаспоры Тойжан Бабык». 20 March 2010. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ «Population data». czso.cz. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ^ Ukrainian population census 2001[dead link]: Distribution of population by nationality. Retrieved 23 April 2009

- ^ «Main Language in England & Wales by Proficiency in English 2011». Office for National Statistics. 2011. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ «UAE´s population – by nationality». BQ Magazine. 12 April 2015. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ «Cittadini Kazaki in Italia Dati Istat al 2022». Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ «Kazakhstan country brief». Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ «Bevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeit und Geburtsland». Statistik Austria. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ population census 2009 Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine: National composition of the population.

- ^ «Kasachische Diaspora in Deutschland. Botschaft der Republik Kasachstan in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland» (in German). botschaft-kaz.de. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016.

- ^ «Sefstat».

- ^ a b c Лаханұлы, Нұртай (10 September 2021). «Ауғанстанда қанша қазақ тұрады?». Азаттық Радиосы. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ «how many kazakhs live in philippines?». Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ «Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation». The World’s Muslims: Unity and Diversity. Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2013

- ^ Jayaraj, Deepak (2018). «KAZAKH NOMADISM AND THE RISE OF KAZAKH KHANATE IN THE 16th CENTURY». Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 79: 676–684. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 26906306. Archived from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ Lee, Joo-Yup; Kuang, Shuntu (18 October 2017). «A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and y-dna Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples». Inner Asia. 19 (2): 197–239. doi:10.1163/22105018-12340089. ISSN 2210-5018. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Kolsto, Pal (January 1998). «Anticipating Demographic Superiority: Kazakh Thinking on Integration and Nation». Europe-Asia Studies. 50 (1): 51–69. doi:10.1080/09668139808412523. hdl:10852/25215. JSTOR 153405. PMID 12348666. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Buri, Tabea (2016). «Urbanisation and Changing Kazakh Ethnic Subjectivities in Gansu, China». Inner Asia. 18 (1): 79–96 (87). doi:10.1163/22105018-12340054. JSTOR 44645086. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Barthold, V. V. (1962). Four Studies on the History of Central Asia. Vol. &thinsp, 3. Translated by V. & T. Minorsky. Leiden: Brill Publishers. p. 129.

- ^ Olcott, Martha Brill (1995). The Kazakhs. Hoover Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8179-9351-1. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ Caroe, Olaf (1953). Soviet Empire : the Turks of Central Asia and Stalinism. Macmillan. p. 38. OCLC 862273470.

- ^ Уюк-Туран [Uyuk-Turan] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 5 February 2006.

- ^ Yudin, Veniamin P. (2001). Центральная Азия в 14–18 веках глазами востоковеда [Central Asia in the eyes of 14th–18th century Orientalists]. Almaty: Dajk-Press. ISBN 978-9965-441-39-4.

- ^ Pultar, Gönül (14 April 2014). Imagined Identities: Identity Formation in the Age of Globalization. Syracuse University Press. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-8156-3342-6. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ Subtelny, Maria Eva (1988). «Centralizing Reform and Its Opponents in the Late Timurid Period». Iranian Studies. Taylor & Francis, on behalf of the International Society of Iranian Studies. 21 (1/2: Soviet and North American Studies on Central Asia): 123–151. doi:10.1080/00210868808701712. JSTOR 4310597.

- ^ Kenzheakhmet Nurlan (2013). The Qazaq Khanate as Documented in Ming Dynasty Sources. p. 133.

- ^ Bregel, Yuri (1982). «Abu’l-Kayr Khan». Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. 1. Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 331–332. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ Barthold, V. V. (1962). «History of the Semirechyé». Four Studies on the History of Central Asia. Vol. &thinsp, 1. Translated by V. & T. Minorsky. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 137–65.

- ^ Kenzheakhmet Nurlan (2013). The Qazaq Khanate as Documented in Ming Dynasty Sources. p. 140.

- ^ Постановление ЦИК и СНК КазАССР № 133 от 5 February 1936 о русском произношении и письменном обозначении слова «казак»

- ^ «Cossack». Online Etymology Dictionary. Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ «Cossack | Russian and Ukrainian people». Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 May 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ a b Dubuisson, Eva Marie (28 July 2017). Living Language in Kazakhstan: The Dialogic Emergence of an Ancestral Worldview. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-8229-8283-8. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ Breed, Ananda; Dubuisson, Eva-Marie; Iğmen, Ali (24 November 2020). Creating Culture in (Post) Socialist Central Asia. Springer Nature. p. 145. ISBN 978-3-030-58685-0. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ Kudaibergenova, Diana T. (3 February 2017). Rewriting the Nation in Modern Kazakh Literature: Elites and Narratives. Lexington Books. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-4985-2830-6. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ Russian, Mongolia, China in the 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries. Vol II. Baddeley (1919, MacMillan, London). Reprint – Burt Franklin, New York. 1963 p. 59

- ^ Bennigsen, Alexandre; Wimbush, S. Enders (1986). Muslims of the Soviet Empire: A Guide. Indiana University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-253-33958-4. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Khodarkovsky, Michael. Russia’s Steppe Frontier: The Making of a Colonial Empire, 1500–1800, pg. 39.

- ^ a b Ember, Carol R. and Melvin Ember. Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Men and Women in the World’s Cultures, pg. 572

- ^ a b Hunter, Shireen. «Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security», pg. 14

- ^ Farah, Caesar E. Islam: Beliefs and Observances, pg. 304

- ^ Farah, Caesar E. Islam: Beliefs and Observances, pg. 340

- ^ Page, Kogan. Asia and Pacific Review 2003/04, pg. 99

- ^ Atabaki, Touraj. Central Asia and the Caucasus: transnationalism and diaspora.

- ^ inform.kz | 154837 Archived 20 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Итоги национальной переписи населения 2009 года (Summary of the 2009 national census) (in Russian). Agency of Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ Kalysh, Amanzhol; Isayeva, Aliya (15 May 2014). «Ethnogenesis and Ethnic Processes in Modern Kazakhstan». Procedia — Social and Behavioral Sciences. 3rd World Conference on Educational Technology Researches 2013, WCETR 2013, 7–9 November 2013, Antalya, Turkey. 131: 271–277. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.116. ISSN 1877-0428.

- ^ Айжан; TV, Qazaq. «Kazakh scientists recreate ethnogenesis of Kazakh people — Kazakh culture and traditions,Nature,Kazakh food,Nomads,Kazakhstan,Qazaqstan | Jibek Joly». jjtv.kz. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ a b White, Anna E.; de-Dios, Toni; Carrión, Pablo; Bonora, Gian Luca; Llovera, Laia; Cilli, Elisabetta; Lizano, Esther; Khabdulina, Maral K.; Tleugabulov, Daniyar T.; Olalde, Iñigo; Marquès-Bonet, Tomàs; Balloux, François; Pettener, Davide; van Dorp, Lucy; Luiselli, Donata (December 2021). «Genomic Analysis of 18th-Century Kazakh Individuals and Their Oral Microbiome». Biology. 10 (12): 1324. doi:10.3390/biology10121324. ISSN 2079-7737. PMC 8698332. PMID 34943238.

- ^ Li Bo; Zheng Yin. 5000 Years of Chinese History. p. 767.

- ^ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian crossroads : a history of Xinjiang. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3. OCLC 63808300.

- ^ Lee, Joo-Yup; Kuang, Shuntu (18 October 2017). «A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and y-dna Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples». Inner Asia. 19 (2): 197–239. doi:10.1163/22105018-12340089. ISSN 2210-5018. S2CID 165623743. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Findley, Carter V. (2005). The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-517726-8. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ «Kazakh | People, Religion, Language, & Culture | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 27 June 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Valeev, Albert; Litvinov, Sergei; Valiev, Ruslan; Akhmetova, Vita; Balanovska, Elena; Balanovsky, Oleg; Turdikulova, Shahlo; Dalimova, Dilbar; Nymadawa, Pagbajabyn; Bahmanimehr, Ardeshir; Sahakyan, Hovhannes; Tambets, Kristiina (21 April 2015). «The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia». PLOS Genetics. 11 (4): e1005068. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 4405460. PMID 25898006.

- ^ Zhabagin, Maxat; Sabitov, Zhaxylyk; Tarlykov, Pavel; Tazhigulova, Inkar; Junissova, Zukhra; Yerezhepov, Dauren; Akilzhanov, Rakhmetolla; Zholdybayeva, Elena; Wei, Lan-Hai; Akilzhanova, Ainur; Balanovsky, Oleg; Balanovska, Elena (22 October 2020). «The medieval Mongolian roots of Y-chromosomal lineages from South Kazakhstan». BMC Genetics. 21 (1): 87. doi:10.1186/s12863-020-00897-5. ISSN 1471-2156. PMC 7583311. PMID 33092538. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Khussainova, Elmira; Kisselev, Ilya; Iksan, Olzhas; Bekmanov, Bakhytzhan; Skvortsova, Liliya; Garshin, Alexander; Kuzovleva, Elena; Zhaniyazov, Zhassulan; Zhunussova, Gulnur; Musralina, Lyazzat; Kahbatkyzy, Nurzhibek; Amirgaliyeva, Almira; Begmanova, Mamura; Seisenbayeva, Akerke; Bespalova, Kira (2022). «Genetic Relationship Among the Kazakh People Based on Y-STR Markers Reveals Evidence of Genetic Variation Among Tribes and Zhuz». Frontiers in Genetics. 12: 801295. doi:10.3389/fgene.2021.801295. ISSN 1664-8021. PMC 8777105. PMID 35069700.

- ^ Zhao, Jing; Wurigemule; Sun, Jin; Xia, Ziyang; He, Guanglin; Yang, Xiaomin; Guo, Jianxin; Cheng, Hui-Zhen; Li, Yingxiang; Lin, Song; Yang, Tie-Lin (16 November 2020). «Genetic substructure and admixture of Mongolians and Kazakhs inferred from genome-wide array genotyping». Annals of Human Biology. 47 (7–8): 620–628. doi:10.1080/03014460.2020.1837952. ISSN 0301-4460. PMID 33059477. S2CID 222839155.

- ^ Kidd et al. 2009, Am J Hum Genet. Dec 11, 2009; 85(6): 934–937. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.024

- ^ Kairov, Ulykbek; Molkenov, Askhat; Rakhimova, Saule; Kozhamkulov, Ulan; Sharip, Aigul; Karabayev, Daniyar; Daniyarov, Asset; H.Lee, Joseph; D.Terwilliger, Joseph; Akilzhanova, Ainur; Zhumadilov, Zhaxybay (4 February 2021). «Whole-genome sequencing data of Kazakh individuals». BMC Research Notes. 14 (1): 45. doi:10.1186/s13104-021-05464-4. ISSN 1756-0500. PMC 7863413. PMID 33541395. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Valeev, Albert; Litvinov, Sergei; Valiev, Ruslan; Akhmetova, Vita; Balanovska, Elena; Balanovsky, Oleg; Turdikulova, Shahlo; Dalimova, Dilbar (21 April 2015). «The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia». PLOS Genetics. 11 (4): e1005068. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 4405460. PMID 25898006.

- ^ Seidualy, Madina; Blazyte, Asta; Jeon, Sungwon; Bhak, Youngjune; Jeon, Yeonsu; Kim, Jungeun; Eriksson, Anders; Bolser, Dan; Yoon, Changhan; Manica, Andrea; Lee, Semin (1 May 2020). «Decoding a highly mixed Kazakh genome». Human Genetics. 139 (5): 557–568. doi:10.1007/s00439-020-02132-8. ISSN 1432-1203. PMC 7170836. PMID 32076829. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ Katsuyama, Y.; Inoko, H.; Imanishi, T.; Mizuki, N.; Gojobori, T.; Ota, M. (May 1998). «Genetic relationships among Japanese, northern Han, Hui, Uygur, Kazakh, Greek, Saudi Arabian, and Italian populations based on allelic frequencies at four VNTR (D1S80, D4S43, COL2A1, D17S5) and one STR (ACTBP2) loci». Human Heredity. 48 (3): 126–137. doi:10.1159/000022793. ISSN 0001-5652. PMID 9618060. S2CID 46853437. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ Seidualy, Madina; Blazyte, Asta; Jeon, Sungwon; Bhak, Youngjune; Jeon, Yeonsu; Kim, Jungeun; Eriksson, Anders; Bolser, Dan; Yoon, Changhan; Manica, Andrea; Lee, Semin (1 May 2020). «Decoding a highly mixed Kazakh genome». Human Genetics. 139 (5): 557–568. doi:10.1007/s00439-020-02132-8. ISSN 1432-1203. PMC 7170836. PMID 32076829. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ «Полиморфизм митохондриальной ДНК в казахской популяции». Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^ a b c Omer Gokcumen, Matthew C. Dulik, Athma A. Pai, Sergey I. Zhadanov, Samara Rubinstein, Ludmila P. Osipova, Oleg V. Andreenkov, Ludmila E. Tabikhanova, Marina A. Gubina, Damian Labuda, and Theodore G. Schurr, «Genetic Variation in the Enigmatic Altaian Kazakhs of South-Central Russia: Insights into Turkic Population History.» American Journal of Physical Anthropology 136:278–293 (2008). DOI 10.1002/ajpa.20802

- ^ Zerjal T, Wells RS, Yuldasheva N, Ruzibakiev R, Tyler-Smith C (September 2002). «A genetic landscape reshaped by recent events: Y-chromosomal insights into central Asia». Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71 (3): 466–82. doi:10.1086/342096. PMC 419996. PMID 12145751.

- ^ «Ethnic composition of Russia (national censuses)». Demoscope.ru. 27 May 2007. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ American Academy of Political and Social Science (1951). The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volume 277. American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 152. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ American Academy of Political and Social Science (1951). Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volumes 276–278. American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 152. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ American Academy of Political and Social Science (1951). The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volume 277. American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 152. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

A group of Kazakhs, originally numbering over 20000 people when expelled from Sinkiang by Sheng Shih-ts’ai in 1936, was reduced, after repeated massacres by their Chinese coreligionists under Ma Pu-fang, to a scattered 135 people.

- ^ Hsaio-ting Lin (1 January 2011). Tibet and Nationalist China’s Frontier: Intrigues and Ethnopolitics, 1928–49. UBC Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-7748-5988-2.

- ^ Hsaio-ting Lin (1 January 2011). Tibet and Nationalist China’s Frontier: Intrigues and Ethnopolitics, 1928–49. UBC Press. pp. 231–. ISBN 978-0-7748-5988-2. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Blackwood’s Magazine. William Blackwood. 1948. p. 407. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Devlet, Nadir. STUDIES IN THE POLITICS, HISTORY AND CULTURE OF TURKIC PEOPLES. p. 192. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Linda Benson (1988). The Kazaks of China: Essays on an Ethnic Minority. Ubsaliensis S. Academiae. p. 195. ISBN 978-91-554-2255-4. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ «Central Asians Organize to Draw Attention to Xinjiang Camps». The Diplomat. 4 December 2018. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ «Majlis Podcast: The Repercussions Of Beijing’s Policies In Xinjiang». Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL). 9 December 2018. Archived from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ «Families Of The Disappeared: A Search For Loved Ones Held In China’s Xinjiang Region». NPR. 12 November 2018. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ Education of Kazakh children: A situation analysis. Save the Children UK, 2006 [1] Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sharyngol city review[dead link]

- ^ «Монгол улсын ястангуудын тоо, байршилд гарч буй өөрчлөлтуудийн асуудалд» М.Баянтөр, Г.Нямдаваа, З.Баярмаа pp.57–70 Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «2020 POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS OF MONGOLIA /summary/». Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ «Численность казахов в Узбекистане за последние 32 года практически не изменилась». Радио Азаттык (in Russian). 21 August 2021. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ electricpulp.com. «BARDA and BARDA-DĀRI iv. From the Mongols – Encyclopaedia Iranica». iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ^ Keith Edward Abbott; Abbas Amanat (1983). Cities & trade: Consul Abbott on the economy and society of Iran, 1847–1866. Published by Ithaca Press for the Board of the Faculty of Oriental Studies, Oxford University. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-86372-006-2. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ «گلستان». Anobanini.ir. Archived from the original on 28 February 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ «Ethnologue report for Iran». Ethnologue.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ «پایگاه اطلاع رسانی استانداری گلستان». www.golestanstate.ir. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009.

- ^ «قزاق». Jolay.blogfa.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ News Review on South Asia and Indian Ocean. Institute for Defence Studies & Analyses. July 1982. p. 861.

- ^ Problèmes politiques et sociaux. Documentation française. 1982. p. 15. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Espace populations sociétés. Université des sciences et techniques de Lille, U.E.R. de géographie. 2006. p. 174. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Andrew D. W. Forbes (9 October 1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. CUP Archive. pp. 156–. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1.Andrew D. W. Forbes (9 October 1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. CUP Archive. pp. 236–. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ «Kazakh Turks Foundation Official Website». Kazak Türkleri Vakfı Resmi Web Sayfası. Archived from the original on 13 September 2016.

External links

- Kazakh tribes

- ‘Contemporary Falconry in Altai-Kazakh in Western Mongolia’The International Journal of Intangible Heritage (vol.7), pp. 103–111. 2012. [2]

- ‘Ethnoarhchaeology of Horse-Riding Falconry’, The Asian Conference on the Social Sciences 2012 – Official Conference Proceedings, pp. 167–182. 2012. [3]

- ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage of Arts and Knowledge for Coexisting with Golden Eagles: Ethnographic Studies in “Horseback Eagle-Hunting” of Altai-Kazakh Falconers’, The International Congress of Humanities and Social Sciences Research, pp. 307–316. 2012. [4]

- ‘Ethnographic Study of Altaic Kazakh Falconers’, Falco: The Newsletter of the Middle East Falcon Research Group 41, pp. 10–14. 2013. [5]

- ‘Ethnoarchaeology of Ancient Falconry in East Asia’, The Asian Conference on Cultural Studies 2013 – Official Conference Proceedings, pp. 81–95. 2013. [6]

- Soma, Takuya. 2014. ‘Current Situation and Issues of Transhumant Animal Herding in Sagsai County, Bayan Ulgii Province, Western Mongolia’, E-journal GEO 9(1): pp. 102–119. [7]

- Soma, Takuya. 2015. Human and Raptor Interactions in the Context of a Nomadic Society: Anthropological and Ethno-Ornithological Studies of Altaic Kazakh Falconry and its Cultural Sustainability in Western Mongolia. University of Kassel Press, Kassel (Germany) ISBN 978-3-86219-565-7.

1

: a member of a Turkic people of Kazakhstan and other countries of central Asia

2

: the language of the Kazakhs

Kazakh

adjective

or less commonly Kazak

Example Sentences

Recent Examples on the Web

There’s about 30,000 local people who spoke Kazakh, the majority didn’t speak English.

—

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘Kazakh.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Etymology

Russian kazakh, from Kazakh kazak

First Known Use

1832, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Time Traveler

The first known use of Kazakh was

in 1832

Dictionary Entries Near Kazakh

Cite this Entry

“Kazakh.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Kazakh. Accessed 14 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on Kazakh

Last Updated:

4 Apr 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

|

|||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| approx. 19,100,000 | |||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||

|

Kazakh, Russian |

|||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||

|

Sunni Islam, Tengrism, Atheism |

|||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||

|

Nogais, Karakalpaks, Mongols, other Turkic peoples |

The Kazakhs (Kazakh: Қазақтар (Cyrillic)/قازاقتار (Perso-Arabic) Qazaqtar, Russian: Казахи) also spelled Kazaks, Qazaqs; are a Turkic people of Eastern Europe and the northern parts of Central Asia (largely Kazakhstan, but also found in parts of Uzbekistan, China, Russia and Mongolia).

Kazakh identity is of medieval origin and was strongly shaped by foundation of the Kazakh Khanate in 1456–1465. The formation of Khanate began when several tribes under the rule of sultans Janybek and Kerey departed from the Khanate of Abu’l-Khayr Khan.

Kazakhs are descendants of the Turkic tribes – Argyns, Khazars, Qarluqs; and of the Kipchaks and Cumans,[6][7] and other tribes such as the Huns, and ancient Iranian nomads like the Sarmatians, Saka and Scythians from East Europe populated the territory between Siberia and the Black Sea and remained in Central Asia and Eastern Europe when the nomadic groups started to invade and conquer the area between the 5th and 13th centuries AD.[8][9][10][11]

Etymology[]

The Kazakhs probably began using this name during either the 15th or 16th centuries.[12] There are many theories on the origin of the word Kazakh or Qazaq. Some speculate that it comes from the Turkish verb qaz (to wander), because the Kazakhs were wandering steppemen; or that it derives from the prototurkic word khasaq (a wheeled cart used by the Kazakhs to transport their yurts and belongings).[13]

In the 19th century, one etymological explanation was that the name came from the popular Kazakh legend of the white goose (qaz means «goose», aq means «white»).[13][14] In this creation myth, a white steppe goose turned into a princess, who in turn gave birth to the first Kazakh. This etymological derivation is regarded as flawed because, in Turkic languages, the adjective is put before the noun, and therefore «white goose» would be Aqqaz, not Qazaq.[citation needed]

Another theory on the origin of the word Kazakh (originally Qazaq) is that it comes from the ancient Turkic word qazğaq, first mentioned on the 8th century Turkic monument of Uyuk-Turan. According to the notable Turkic linguist Vasily Radlov and the orientalist Veniamin Yudin, the noun qazğaq derives from the same root as the verb qazğan («to obtain», «to gain»). Therefore, qazğaq defines a type of person who seeks profit and gain.[15]

Kazakh was a common term throughout medieval Central Asia, generally with regard to individuals or groups who had taken or achieved independence from a figure of authority. Timur described his own youth without directory authority as his Qazaqliq (Qazaqness).[16] At the time of the Uzbek nomads’ Conquest of Central Asia, the Uzbek khan Abul-Khayr had differences with the Chinggisid chiefs Kerei and Janibek, descendants of Urus Khan.

File:SB — Inside a Kazakh yurt.jpg Kazakh family inside a Yurt, 1911/1914

These differences probably resulted from the crushing defeat of Abul-Khayr Khan at the hands of the Qalmaqs.[17] Kirey and Janibek moved with a large following of nomads to the region of Zhetysu/Semirechye on the border of Moghulistan and set up new pastures there with the blessing of the Moghul Chingisid Esen Buqa, who hoped for a buffer zone of protection against the expansion of the Oirats.[18] It is not explicitly explained that this is why the later Kazakhs took the name permanently, but it is the only historically verifiable source of the ethnonym. The group under Kirey and Janibek are called in various sources Qazaqs and Uzbek-Qazaqs (those independent of the Uzbek khans). Later Russian language sources incorrectly termed them Kirghiz and Kirghiz-Kaisak.

The word Kazakh stems largely from a Russian convention seeking to distinguish the Qazaqs of the steppes from the Cossacks of the Russian Imperial military.

- Kazakh – Казах

- Cossack – Казак

The Russian term Cossack probably comes from the same Kypchak etymological root, i.e. wanderer, brigand, independent free-booter.

8th century to 15th century[]

The Qarluqs, a confederation of Turkic tribes, established a state in what is now eastern Kazakhstan in 766. In the 8th and 9th centuries, portions of southern Kazakhstan were conquered by Arabs, who introduced Islam. The Oghuz Turks controlled western Kazakhstan from the 9th through the 11th centuries; the Kimak and Kipchak peoples, also of Turkic origin, controlled the east at roughly the same time. In turn the Cumans controlled western Kazakhstan roughly from the 1100s until the 1220s. The large central desert of Kazakhstan is still called Dashti-Kipchak, or the Kipchak Steppe.[curtis 1] The capital (Astana) was home of a lot of Huns and Saka.

In the 9th century, the Qarluq confederation formed the Qarakhanid state, which then conquered Transoxiana, the area north and east of the Oxus River (the present-day Amu Darya). Beginning in the early 11th century, the Qarakhanids fought constantly among themselves and with the Seljuk Turks to the south. The Qarakhanids, who had converted to Islam, were conquered in the 1130s by the Kara-Khitan, a Mongolic people who moved west from Northern China. In the mid-12th century, an independent state of Khorazm along the Oxus River broke away from the weakening Karakitai, but the bulk of the Kara-Khitan lasted until the Mongol invasion of Genghis Khan in 1219–1221.[curtis 1]

After the Mongol capture of the Kara-Khitan, Kazakhstan fell under the control of a succession of rulers of the Mongol Golden Horde, the western branch of the Mongol Empire. The horde, or jüz, is the precursor of the present-day clan. By the early 15th century, the ruling structure had split into several large groups known as khanates, including the Nogai Horde and the Uzbek Khanate.[curtis 1]

Kazakh Khanate (1465–1731)[]

Stamp of Kazakhstan devoted to Abilqaiyr Khan

The Kazakh Khanate (Kazakh: Қазақ хандығы) was founded in 1465 on the banks of Jetysu (literally means seven rivers) in the south eastern part of present Republic of Kazakhstan by Janibek Khan and Kerei Khan. During the reign of Qasym Khan (1511–1523), the Kazakh Khanate expanded considerably. Qasym Khan instituted the first Kazakh code of laws in 1520, called «Qasym Khannyn Qasqa Zholy» (Bright Road of Qasym Khan).

At its height the Khanate would rule parts of Central Asia and control Cumania. The Kazakhs nomads would raid people of Russian territory for slaves until the Russians conquered Kazakhstan.

Other prominent Kazakh khans included Haqnazar Khan, Esim Khan, Tauke Khan, and Ablai Khan.

The Kazakh Khanate did not always have a unified government. The Kazakhs were traditionally divided into three parts – the Great jüz, Middle jüz, and Little jüz. All juzes had to agree in order to have a common khan. In particular, in 1731 there was no strong Kazakh leadership, and the three juzes were incorporated into the Russian Empire one by one. At that point, the Kazakh Khanate ceased to exist.

The Kazakh Khanate is described in historical texts such as the Tarikh-i-Rashidi (1541–1545) by Muhammad Haidar Dughlat, and Zhamigi-at-Tavarikh (1598–1599) by Kadyrgali Kosynuli Zhalayir.

Russian Rule 1731–1917[]

Russian traders and soldiers began to appear on the northwestern edge of Kazakh territory in the 17th

Kazakhs deliver a white horse as a gift to the Qianlong Emperor of China (1757), soon after the Qing expelled the Mongols from Xinjiang. Soon, intensive trade started in Yining and Tacheng, Kazakh horses, sheep and goats being traded for Chinese silk and cotton fabrics

century, when Cossacks established the forts that later became the cities of Yaitsk ( modern Oral) and Guryev (modern Atyrau). Russians were able to seize Kazakh territory because the khanates were preoccupied by Zunghar Oirats, who in the late 16th century had begun to move into Kazakh territory from the east. Forced westward in what they call their Great Retreat, the Kazakhs were increasingly caught between the Kalmyks and the Russians.

Two of Kazakh Hordes were depend of Oirat Huntaiji. In 1730 Abilqaiyr, one of the khans of the Lesser Horde, sought Russian assistance. Although Abilqaiyr’s intent had been to form a temporary alliance against the stronger Kalmyks, the Russians gained permanent control of the Lesser Horde as a result of his decision. The Russians conquered the Middle Horde by 1798, but the Great Horde managed to remain independent until the 1820s, when the expanding Kokand Khanate to the south forced the Great Horde khans to choose Russian protection, which seemed to them the lesser of two evils.

The colonization of Kazakhstan by Russia was slowed down by numerous uprisings and wars in 19th century. For example, uprisings of Isatay Taymanuly and Makhambet Utemisuly in 1836 – 1838 and the war led by Eset Kotibaruli in 1847 – 1858 were one of such events of anti-colonial resistance.

In 1863, Russian Empire elaborated a new imperial policy, announced in the Gorchakov Circular, asserting the right to annex «troublesome» areas on the empire’s borders. This policy led immediately to the Russian conquest of the rest of Central Asia and the creation of two administrative districts, the General-Gubernatorstvo (Governor-Generalship) of Russian Turkestan and that of the Steppe. Most of present-day Kazakhstan was in the Steppe District, and parts of present-day southern Kazakhstan, including Almaty (Verny), were in the Governor-Generalship.[curtis 2]

In the early 19th century, the construction of Russian forts began to have a destructive effect on the Kazakh traditional economy by limiting the once-vast territory over which the nomadic tribes could drive their herds and flocks. The final disruption of nomadism began in the 1890s, when many Russian settlers were introduced into the fertile lands of northern and eastern Kazakhstan.[curtis 2]

In 1906, the Trans-Aral Railway between Orenburg and Tashkent was completed, further facilitating Russian colonization of the fertile lands of Semirechie. Between 1906 and 1912, more than a half-million Russian farms were started as part of the reforms of Russian minister of the interior Petr Stolypin, putting immense pressure on the traditional Kazakh way of life by occupying grazing land and using scarce water resources. The administrator for Turkestan (current Kazakhstan) Vasile Balabanov was responsible for the Russian resettlement during this time.

Starving and displaced, many Kazakhs joined in the general Central Asian Revolt against conscription into the Russian imperial army, which the tsar ordered in July 1916 as part of the effort against Germany in World War I. In late 1916, Russian forces brutally suppressed the widespread-armed resistance to the taking of land and conscription of Central Asians. Thousands of Kazakhs were killed, and thousands of others fled to China and Mongolia.[curtis 2]

Many Kazakhs and Russians fought the communist takeover and resisted their control until 1920.

Alash Horde 1917-1920[]

In 1917 a group of secular nationalists called the Alash Orda Horde of Alash, named for a legendary founder of the Kazakh people, attempted to set up an independent national government – the Alash Autonomy. This state lasted just over two years (13 December 1917 to 26 August 1920) before surrendering to the Bolshevik authorities, who then sought to preserve Russian control under a new political system.[curtis 3]

During this period, the Russian administrator Vasile Balabanov had control much of the time with General Dootoff.

Soviet Rule 1917-1991 (Kazakh SSR)[]

The Kyrgyz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was set up in 1920 and was renamed the Kazakh Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic in 1925 when the Kazakhs were differentiated officially from the Kyrgyz. The Russian Empire recognized the ethnic difference between the two groups; it called them both Kyrgyz to avoid confusion between the terms Kazakh and Cossack (both names originating from Turkic «free man».)

In 1925, the autonomous republic’s original capital, Orenburg possibly from Horn-(meaning corner) and Burg- (meaning Castle), was reincorporated into Russian territory. Kyzylorda became capital of it till 1929. Almaty (called Alma-Ata during the Soviet period), a provincial city in the far southeast, became the new capital in 1929. In 1936 the territory was made a full Soviet republic, the Kazakh SSR, also called Kazakhstan. With an area of, the Kazakh SSR was the second largest constituent republic of the Soviet Union.

Famines (1929-1934)[]

From 1929 to 1934, during the period when Soviet leader Joseph Stalin was trying to collectivize agriculture, Kazakhstan endured repeated famines, similar to the Holodomor[19] in Ukraine, for which it may have provided a model,[20] because peasants had slaughtered their livestock in protest against Soviet agricultural policy.[21] In that period, over a million Kazakhs[22] and 80 percent of the republic’s livestock died. Thousands more Kazakhs tried to escape to China, although most starved in the attempt.

Republic of Kazakhstan 1991-present[]

On 16 December 1986, the Soviet Politburo dismissed the long serving General Secretary of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan, Dinmukhamed Konayev. His successor was Gennady Kolbin from Ulyanovsk, Russia. This caused demonstrations protesting this move. These demonstrations were violently suppressed by the authorities, «between two and twenty people lost their lives, and between 763 and 1137 received injuries. Between 2212 and 2336 demonstrators were arrested».[23] Also Kolbin prepared to unleash a purge within the Communist Youth League against any sympathisers, these moves were halted by Moscow. Later, in September 1989, Kolbin was replaced with a Kazakh, Nursultan Nazarbayev. Under Nazarebayev’s influential leadership, Kazakhstan took lots of steps in improving relations with both their Russian neighbor and its western neighbors .

Language[]

A 1920s Kazakh text in both Cyrillic and Perso-Arabic scripts

The Kazakh language is a member of the Turkic language family, as are Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Tatar, Uyghur, Turkish, Azeri, Turkmen, and many other living and historical languages spoken in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, Xinjiang, and Siberia.

Kazakh belongs to the Kipchak (Northwestern) group of the Turkic language family. Kazakh is characterized, in distinction to other Turkic languages, by the presence of in place of reconstructed proto-Turkic and in place of; furthermore, Kazakh has where other Turkic languages have.

Kazakh, like most of the Turkic language family lacks phonemic vowel length, and as such there is no distinction between long and short vowels.

Kazakh is the national language of Kazakhstan. It is also spoken in the Ili region of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in China, where a big Kazakh community lives, as well as in Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Russia.

Additionally, many Kazakhs are also fluent in the Russian language, and Russian is an official language in Kazakhstan. The overwhelming majority of Kazakhs within Kazakhstan are Russophone. Kazakhstan is one of two Central Asian former Soviet states that has kept Russian an official language, the other being Kyrgyzstan. Kazakhs also bear Russian influence in their names, they bear names of Arabic and Turkish origin and add the Slavic suffix «-ov» or «-ev».

The Kazakhs living in China and Mongolia however, do not speak Russian as a second language. They speak the respective national and/or official languages of their home countries, in this case, Chinese and Mongolian.

Writing System[]

In Kazakhstan, the Kazakh lanugage is written using the Cyrillic script. This is due to the centuries-long contact with Russia, as well as Kazakhstan’s past existance as a Soviet state. Kazakh was written with the Arabic script during the 19th century, when a number of poets, educated in Islamic schools, incited revolt against Russia. Russia’s response was to set up secular schools and devise a way of writing Kazakh with the Cyrillic alphabet, which was not widely accepted. By 1917, the Arabic script was reintroduced, even in schools and local government. The Kazakhs living in China use the Arabic script to write their language, and in western parts of Mongolia (Bayan-Ölgii and Khovd province), where Cyrillic script is in use. European Kazakhs use the Latin alphabet.

In 1927, a Kazakh nationalist movement sprang up but was soon suppressed. At the same time the Arabic script was banned and the Latin alphabet was imposed for writing Kazakh. The native Latin alphabet was in turn replaced by the Cyrillic alphabet in 1940 by Soviet interventionists. Today, there are efforts to return to the Latin script.

Religion[]

Islam[]

Most Kazakhs today are Muslim. Islam was firstly introduced to ancestors of modern Kazakhs during the 8th century when the Arabs entered Central Asia. Islam initially took hold in the southern portions of Turkestan and thereafter gradually spread northward.[24] Islam also took root due to the zealous missionary work of Samanid rulers, notably in areas surrounding Taraz[25] where a significant number of Turks accepted Islam. Additionally, in the late 14th century, the Golden Horde propagated Islam amongst the Kazakhs and other tribes.

During the 18th century, Russian influence toward the region rapidly increased throughout Central Asia. Led by Catherine, the Russians initially demonstrated a willingness in allowing Islam to flourish as Muslim clerics were invited into the region to preach to the Kazakhs whom the Russians viewed as «savages» and «ignorant» of morals and ethics.[26][27] However, Russian policy gradually changed toward weakening Islam by introducing pre-Islamic elements of collective consciousness.[28] Such attempts included methods of eulogizing pre-Islamic historical figures and imposing a sense of inferiority by sending Kazakhs to highly elite Russian military institutions.[28] In response, Kazakh religious leaders attempted to bring religious fervor by espousing pan-Turkism, though many were persecuted as a result.[29] During the Soviet era, Muslim institutions survived only in areas where Kazakhs significantly outnumbered non-Muslims due to everyday Muslim practices.[30] In an attempt to conform Kazakhs into Communist ideologies, gender relations and other aspects of the Kazakh culture were key targets of social change.[27]

In more recent times however, Kazakhs have gradually employed a determined effort in revitalizing Islamic religious institutions after the fall of the Soviet Union. Some Kazakhs continue to identify with their Islamic faith,[31] and even more devotedly in the countryside.

Historical Religions and Christianity[]

Historically, Kazakhs reflected the religious nature of Central Asia, they followed Shamanism, Buddhism and also some adopted Christianity. Pre-Islamic beliefs—the cults of the sky, of the ancestors, and of fire, for example—continued to a great extent to be preserved among the common people, however. The Kazakhs believed in the supernatural forces of good and evil spirits, of wood goblins and giants. To protect themselves from them, as well as from the evil eye, the Kazakhs wore protection beads and talismans. Shamanic beliefs still widely preserved among the Kazakhs, as well as belief in the strength of the bearers of this cult—the shamans, which the Kazakhs call bakhsy. In contradistinction to the Siberian shamans, who used drums during their rituals, the Kazakh shamans, who could also be men or women, played (with a bow) on a stringed instrument similar to a large violin. At present both Islamic and pre-Islamic beliefs continue to be found among the Kazakhs, especially among the elderly.[32] According to 2009 national census 39,172 Kazakhs are Christians.[33]

Architecture[]

A yurt

Traditional Kazakh architecture is based on the lifestyle of the nomadic Central Asians. They are known as yurts (Kazakh: Алтыаяқ), known as a ger (Mongolian: гэр) with Mongols. Yurts are tent-like structures, made with felt pads that are held together by wooden beams. Yurts are regarded for their ability to stand harsh weather, especially for people living in Siberia and can be found all over the Central Asian countries, as well East Asian countries such as Mongolia and the northern parts of China. Yurts are generally easy to build, and can be built in an hour or even less.

The traditional decoration within a yurt is primarily pattern based. These patterns are generally not according to taste, but are derived from sacred ornaments with certain symbolism. Symbols representing strength are among the most common, including the khas (swastika) and four powerful beasts (lion, tiger, garuda and dragon), as well as stylized representations of the five elements (fire, water, earth, metal, and wood), considered to be the fundamental, unchanging elements of the cosmos. Such patterns are commonly used in the home with the belief that they will bring strength and offer protection.

A Kazakh family inside the yurt

Repeating geometric patterns are also widely used. The most widespread geometric pattern is the continuous hammer or walking pattern (alkhan khee). Commonly used as a border decoration it represents unending strength and constant movement. Another common pattern is the ulzii which as a symbol of long life and happiness. The khamar ugalz (nose pattern) and ever ugalz (horn pattern) are derived from the shape of the animal’s nose and horns, and are the oldest traditional patterns. All patterns can be found among not only the yurts themselves, but also on embroidery, furniture, books, clothing, doors, and other objects.

Karaganda Mosque

The wooden crown of the yurt (Kazakh: шаңырақ, Mongolian: тооно) is itself emblematic in many Central Asian cultures. In old Kazakh communities, the yurt itself would often be repaired and rebuilt, but the crown would remain intact, passed from father to son upon the father’s death. A family’s length of heritage could be measured by the accumulation of stains on the yurt crown from decades of smoke passing through it. A stylized version of the crown is in the center of the coat of arms of Kazakhstan, and forms the main image on the flag of Kyrgyzstan.

Because most Kazakhs are Muslim, Islamic architecture is implemented into Kazakhstan’s urban cities and contain the typical elements of a mosque. They includes domes, a minaret (Arabic: مئذنة) which are towers that Muslims use to call people to prayer. Most of Kazakhstan’s mosques reflect Persian and Turkish influence. Additionally, some Soviet-era buildings are still left in tact in Kazakhstan.

Cuisine[]

Boiled sheep-head