Terrifying people through stories? It’s been a pastime of we humans since antiquity, with a large swathe of folklore centered around things that go bump in the night (particularly supernatural goings-on or anything related to—and exploiting—our innate fear of death.) With such a strong precedent in literature and oral history, it’s no surprise that the first horror movie was quick to get its feet under the table soon after the advent of cinema.

The First Horror Movie: What Was It?

Over the course of a century, film horror has gone through many peaks and troughs, leading us into the somewhat contentious period we find ourselves in today. The history of horror as a film genre begins with—as with many things in cinema history—the works of George Mellies.

Just a few years after the first filmmakers emerged in the mid-1890s, Mellies created “Le Manoir du Diable,” sometimes known in English as “The Haunted Castle” or “ The House of the Devil,” in 1898, and it is widely believed to be the first horror movie. The three-minute film is complete with cauldrons, animated skeletons, ghosts, transforming bats, and, ultimately, an incarnation of the Devil. While not intended to be scary—more wondrous, as was Mellies’ MO—it was the first example of a film (only just rediscovered in 1977) to include the supernatural and set a precedent for what was to come. Where the genre will go over the next hundred years is anyone’s guess, but sometimes it’s good to look back on the long road we’ve traveled to get to this point.

The Literary Years

After the first horror movie, sometime between 1900 and 1920, an influx of supernatural-themed films followed. Many filmmakers—most of whom still trying to find their feet with the new genre—turn to literature classics as source material. The first adaptation of Frankenstein was released by Edison Studios in these early days, as well as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and The Werewolf (now both lost to the fog of time.) Things were starting to roll at this point as we moved into…

The Golden Age of Horror

Widely considered to be the finest era of the genre, the two decades between the 1920s and 30s saw many classics being produced and can be neatly divided down the middle to create a separation between the silent classics and the talkies.

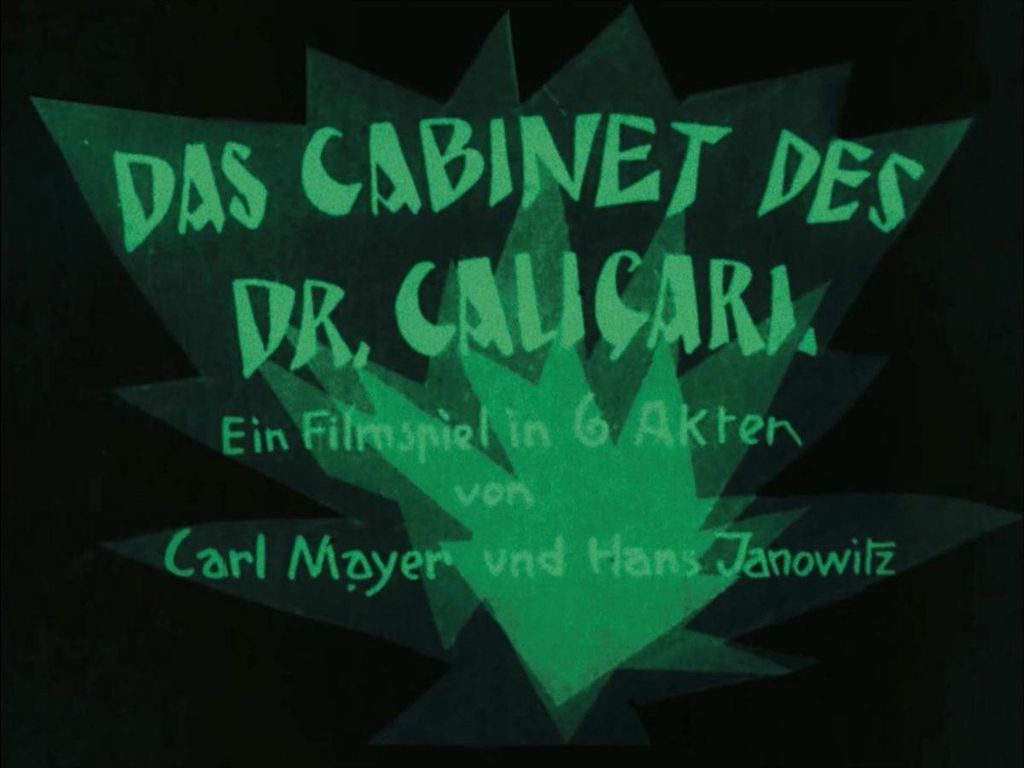

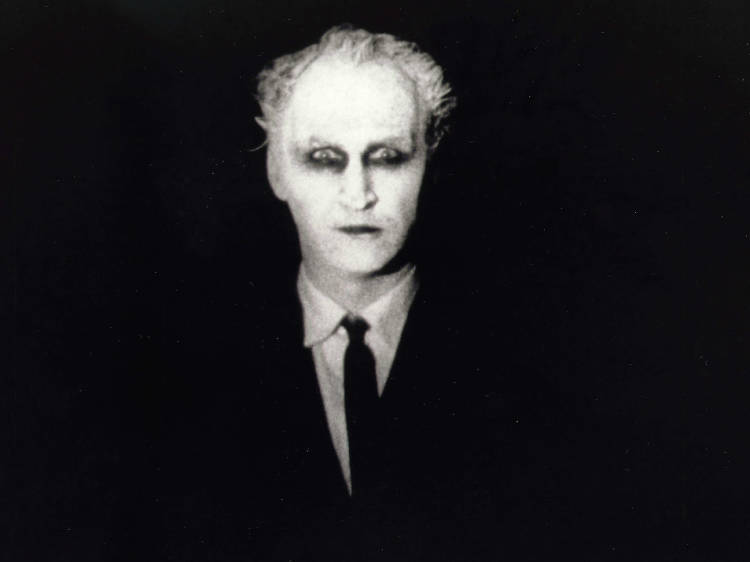

On the silent side of the line, you’ve got monumental titles such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Nosferatu (1922), the first movies to really make an attempt to unsettle their audience. The latter title is one of Rotten Tomatoes’ best horror movies of all time and cements just about every surviving vampire cliché in the book.

Once the silent era gave way to the technological process, we had a glut of incredible movies that paved the way for generations to come, particularly in the field of monster movies – think the second iteration of Frankenstein (1931), The Mummy (1932) and the first color adaptation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931).

The 30s also marked the first time that the word “horror” was used to describe the genre—previously, it was really just romance melodrama with a dark element—and it also saw the first horror “stars” being born. Bella Lugosi (of Dracula fame) was arguably the first to specialize solely in the genre.

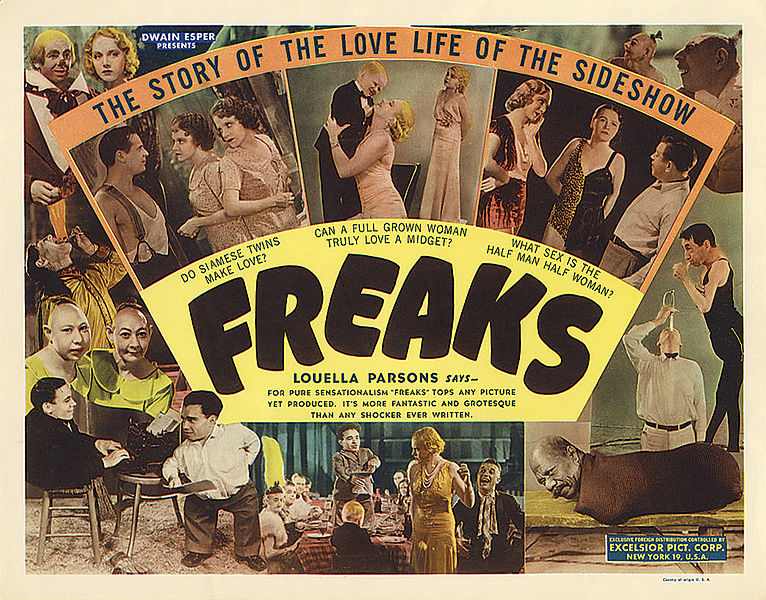

And as well as unnerving its viewers, the genre was starting to worry the general public at this point, with heavy censoring and public outcry becoming common with each release. Freaks (1932) is a good example of a movie that was so shocking at the time it got cut extensively, with the original version now nowhere to be found. Director Tod Browning—who had previously created the aforementioned and wildly successful Dracula—saw his career flounder at the hands of the controversy.

The shock value of Freaks is one of the few that has aged well up until the present day and is still a highly disturbing watch.

The Atomic Years

Freaks were banned for thirty years in the country that really came into its own during this period: Great Britain.

The Hammer horror company, while founded in 1934, only started to turn prolific during the fifties, but when it did, it was near global dominance (thanks to a lucrative distribution deal with Warner and a few other U.S. studios). Once again, it was adaptations like Frankenstein, Dracula, and The Mummy that put the company squarely on the map, followed up by a slew of psychological thrillers and TV shows.

And, of course, you can’t mention British horror without paying respects to Alfred Hitchcock, singlehandedly responsible for establishing the slasher genre, which we’ll see a lot of as we travel further forward in time.

Another hallmark of the 40s-50s era of horror came as a product of the times. With war ravaging Europe and fears of nuclear fallout running rampant, it’s of little surprise that horror began to feature antagonists that were less supernatural in nature—radioactive mutation became a common theme (The Incredible Shrinking Man, Godzilla), as did the fear of invasion with The War of the Worlds and When Worlds Collide, both big hits in 1953.

The latter marked the earliest rumblings of the “disaster” movie genre, but it would be a couple more decades before that would get into full swing.

The Gimmicky Years

3D glasses? Electric buzzers installed into theatre seats? Paid stooges in the audience screaming and pretending to faint? Everything and anything was tried during the 50s and 60s in an attempt to further scare cinema audiences. This penchant for interactivity spilled over into other genres during the period but quickly died down in part due to the massive amount of expense involved. For horror, in particular, this gave way to the opposite end of the spectrum: incredibly low-budget productions.

From the late 60s onwards, so insatiable was the American appetite for gore that slasher films produced for well under $1 million took hold and were churned out by volume. That’s not to say that there weren’t some masterpieces produced during this time, though; George A. Romero emerged triumphant and kickstarted zombie movies in this period, having produced Night of the Living Dead in 1968 with just over $100k. It went on to gross $30 million, and the living dead rose in its wake.

All Hell Breaks Loose

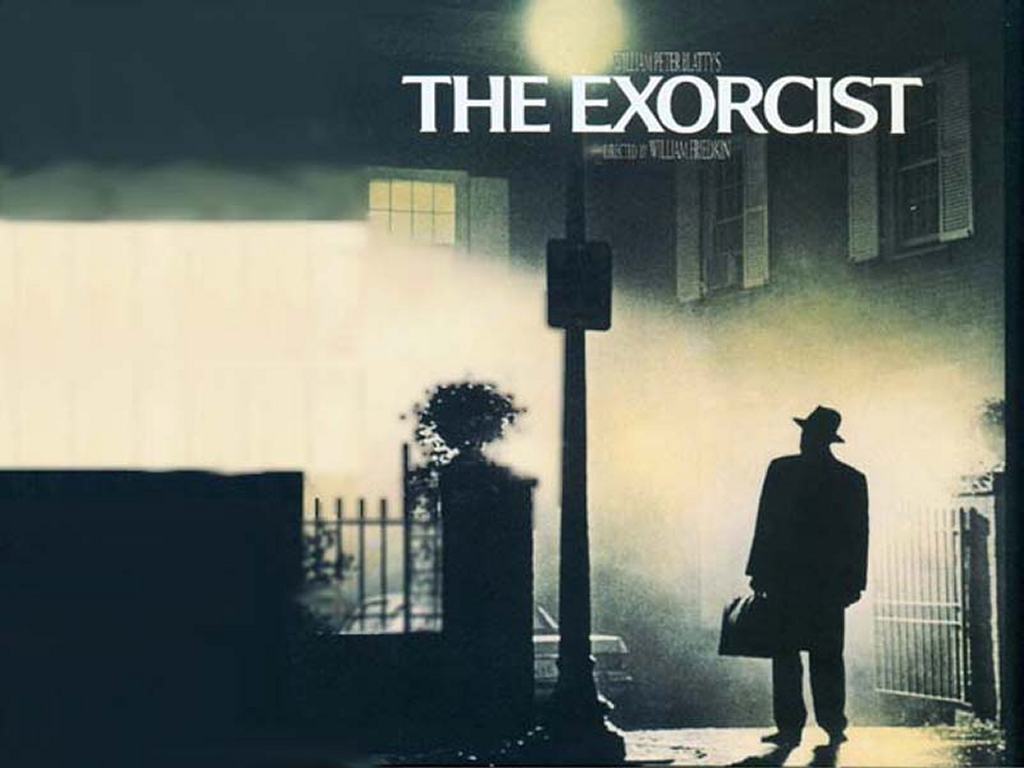

Occult was the flavor of the day between the 70s and 80s, particularly when it came to houses and kids being possessed by the Devil. The reason for this cultural obsession with religious evil during this period could fill an entire article on its own, but bringing it back into the cinema realm, we can boil the trend down to two horror milestones: The Exorcist (1973) and The Omen (1976). Supernatural horror was now very much back in vogue, and harking back to its cinematic origins, literature once again became the source material. This time, however, it wasn’t a Victorian author whose work had fallen out of copyright but a gentleman named Stephen King.

Carrie (1976) stormed the gates, and The Shining (1980) finished the siege (with 1982’s supernatural frightfest Poltergeist following soon afterward). With these hallmarks in the history of horror now firmly established, the foundations were laid for…

The First Horror Movie Slashers

If there’s one trope that typifies the 80s, it’s the slasher format – a relentless antagonist hunting down and killing a bunch of kids in ever-increasing inventive ways, one by one. Arguably kicked off by The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in 1974, the output became prolific over the next decade. For every ten generic slashers, however, there was one flick that would end up becoming a cult classic even if critical success was mixed at the time—Halloween, Friday the 13th, and A Nightmare on Elm Street are the most prominent examples, which became so successful that they spawned their own long-running franchises (the first time in the history of the genre that multiple sequels became commonplace.)

Plenty of imitators and rip-offs followed, too, particularly in the Holiday-themed department. Some were a lot better than others as the genre descended to its most kitschy. Similar to the first horror movie, these films were not intended to scare but to entertain.

The Doldrums

Suffering from exhaustion in the wake of a thousand formulaic slasher movies and their sequels, the genre lost steam as it moved into the 90s. The advent of computer-generated special effects brought with it a number of lackluster CGI monster titles that did little to revive the genre, such as Anaconda (1997) and Deep Rising (1998). But it was a comedy that ended up saving the day. Peter Jackson’s early foray into filmmaking saw him taking the splatter subgenre to ridiculous extremes with Braindead (1992), and Wes Craven’s slasher parody Scream (1996) was met globally with overwhelming success.

The genre as a whole limped on without much fanfare into the 2000s save for a few box office successes. The zombie subgenre, however, sprang back into un-life during this decade, arguably spurred on by the unprecedented success of Max Brook’s novel World War Z (later becoming a film in its own right.) The video game adaptation of Resident Evil (2002) was among the first of the new wave, followed swiftly by 28 Days Later a few months later, Dawn of the Dead (2004), Land of the Dead (2005), I Am Legend (2007) and Zombieland (2009.)

The Present Day

The state of the horror industry is hotly contested. With the genre seemingly relying on churning out remakes, reboots, and endless sequels, many argue that it’s languishing in the doldrums once again with little originality to offer a modern audience. The resurgence of ‘torture porn’ is also derided as a subgenre, having come back into the fore in the wake of the 2000s Saw and Hostel franchises with no signs of slowing down.

On the other hand, glimmers of hope shine through with examples of extreme originality and artistry. Cabin in the Woods (2012) has been heralded as this decade’s Scream, and the recent releases of The Babadook and A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (both 2014) breathed new life into the genre. Jordan Peele, writer, producer, and actor, rose as the new king of horror with original films, including Get Out (2017), Us (2019), and Nope (2022), which top Rotten Tomatoes’ best horror movie list. While scary, the films are also smart and provide sociopolitical commentary, as Peele explained in an interview with Time Magazine. NYFA Alum Tracy Oliver is a co-writer of the 2022 film The Blackening, a movie that makes fun of horror clichés but also calls out racial stereotypes. Both films, similar to the first horror film and a variety of others in the history of horror, don’t have the main goal of scaring the audience.

The Future of Horror Films

With perhaps more subgenres than any other branch of fictional filmmaking, it’s difficult to see how anyone can expand or advance on anything that has come before in cinematic horror. However, there’s no doubt somebody will, and that motivated and imaginative film school students become the Alfred Hitchcocks of tomorrow.

My favorite horror movies of all time.

18+

|

91 min

|

Horror

42

Metascore

Best friends Marie and Alexia decide to spend a quiet weekend at Alexia’s parents’ secluded farmhouse. But on the night of their arrival, the girls’ idyllic getaway turns into an endless night of horror.

Director:

Alexandre Aja

|

Stars:

Cécile de France,

Maïwenn,

Philippe Nahon,

Franck Khalfoun

Votes:

74,213

| Gross:

$3.68M

16+

|

105 min

|

Drama, Horror, Mystery

74

Metascore

A woman brings her family back to her childhood home, which used to be an orphanage for handicapped children. Before long, her son starts to communicate with an invisible new friend.

Director:

J.A. Bayona

|

Stars:

Belén Rueda,

Fernando Cayo,

Roger Príncep,

Mabel Rivera

Votes:

158,778

| Gross:

$7.16M

18+

|

100 min

|

Action, Adventure, Horror

78

Metascore

Six months after the rage virus was inflicted on the population of Great Britain, the US Army helps to secure a small area of London for the survivors to repopulate and start again. But not everything goes according to plan.

Director:

Juan Carlos Fresnadillo

|

Stars:

Jeremy Renner,

Rose Byrne,

Robert Carlyle,

Harold Perrineau

Votes:

282,270

| Gross:

$28.64M

18+

|

93 min

|

Comedy, Drama, Horror

58

Metascore

A socially awkward veterinary assistant with a lazy eye and obsession with perfection descends into depravity after developing a crush on a boy with perfect hands.

Director:

Lucky McKee

|

Stars:

Angela Bettis,

Jeremy Sisto,

Anna Faris,

James Duval

Votes:

38,464

| Gross:

$0.15M

16+

|

103 min

|

Horror, Mystery, Thriller

52

Metascore

A family looks to prevent evil spirits from trapping their comatose child in a realm called The Further.

Director:

James Wan

|

Stars:

Patrick Wilson,

Rose Byrne,

Ty Simpkins,

Lin Shaye

Votes:

316,324

| Gross:

$54.01M

16+

|

99 min

|

Horror

83

Metascore

A loan officer who evicts an old woman from her home finds herself the recipient of a supernatural curse. Desperate, she turns to a seer to try and save her soul, while evil forces work to push her to a breaking point.

Director:

Sam Raimi

|

Stars:

Alison Lohman,

Justin Long,

Ruth Livier,

Lorna Raver

Votes:

208,591

| Gross:

$42.10M

16+

|

92 min

|

Horror, Mystery, Thriller

45

Metascore

A young girl buys an antique box at a yard sale, unaware that inside the collectible lives a malicious ancient spirit. The girl’s father teams with his ex-wife to find a way to end the curse upon their child.

Director:

Ole Bornedal

|

Stars:

Natasha Calis,

Jeffrey Dean Morgan,

Kyra Sedgwick,

Madison Davenport

Votes:

61,388

| Gross:

$49.13M

16+

|

96 min

|

Horror, Thriller

89

Metascore

A ragtag group of Pennsylvanians barricade themselves in an old farmhouse to remain safe from a horde of flesh-eating ghouls that are ravaging the East Coast of the United States.

Director:

George A. Romero

|

Stars:

Duane Jones,

Judith O’Dea,

Karl Hardman,

Marilyn Eastman

Votes:

132,619

| Gross:

$0.09M

91 min

|

Comedy, Horror, Sci-Fi

66

Metascore

When two bumbling employees at a medical supply warehouse accidentally release a deadly gas into the air, the vapors cause the dead to rise again as zombies.

Director:

Dan O’Bannon

|

Stars:

Clu Gulager,

James Karen,

Don Calfa,

Thom Mathews

Votes:

63,984

| Gross:

$14.24M

18+

|

110 min

|

Horror, Mystery, Thriller

53

Metascore

A controversial true crime writer finds a box of super 8 home movies in his new home, revealing that the murder case he is currently researching could be the work of an unknown serial killer whose legacy dates back to the 1960s.

Director:

Scott Derrickson

|

Stars:

Ethan Hawke,

Juliet Rylance,

James Ransone,

Fred Thompson

Votes:

261,284

| Gross:

$48.09M

PG-13

|

90 min

|

Drama, Horror, Mystery

39

Metascore

Eight unsuspecting high school seniors at a posh boarding school, who delight themselves on playing games of lies, come face-to-face with terror and learn that nobody believes a liar — even when they’re telling the truth.

Director:

Jeff Wadlow

|

Stars:

Julian Morris,

Lindy Booth,

Jared Padalecki,

Erica Yates

Votes:

27,901

| Gross:

$10.05M

16+

|

121 min

|

Adventure, Crime, Drama

35

Metascore

After the death of his parents during World War II, young Hannibal Lecter moves in with his beautiful aunt and begins plotting revenge on the barbarians responsible for his sister’s death.

Director:

Peter Webber

|

Stars:

Gaspard Ulliel,

Rhys Ifans,

Gong Li,

Aaran Thomas

Votes:

112,437

| Gross:

$27.67M

16+

|

98 min

|

Horror, Mystery

86

Metascore

Carrie White, a shy, friendless teenage girl who is sheltered by her domineering, religious mother, unleashes her telekinetic powers after being humiliated by her classmates at her senior prom.

Director:

Brian De Palma

|

Stars:

Sissy Spacek,

Piper Laurie,

Amy Irving,

John Travolta

Votes:

193,535

| Gross:

$33.80M

18+

|

97 min

|

Horror

47

Metascore

Having recently witnessed the horrific results of a top secret project to bring the dead back to life, a distraught youth performs the operation on his girlfriend after she’s killed in a motorcycle accident.

Director:

Brian Yuzna

|

Stars:

Kent McCord,

James T. Callahan,

Sarah Douglas,

Melinda Clarke

Votes:

15,814

| Gross:

$0.05M

R

|

92 min

|

Horror, Thriller

Vic visits her sister in Paris. She parties in the catacombs under Paris with her sister and her friends on her first night in France. Remains of 6,000,000+ people is there. Something evil chases her there.

Directors:

Tomm Coker,

David Elliot

|

Stars:

Shannyn Sossamon,

Pink,

Emil Hostina,

Sandi Dragoi

Votes:

8,955

127 min

|

Horror, Thriller

71

Metascore

During an escalating zombie epidemic, two Philadelphia SWAT team members, a traffic reporter and his TV executive girlfriend seek refuge in a secluded shopping mall.

Director:

George A. Romero

|

Stars:

David Emge,

Ken Foree,

Scott H. Reiniger,

Gaylen Ross

Votes:

123,684

| Gross:

$5.10M

12+

|

116 min

|

Action, Adventure, Horror

63

Metascore

Former United Nations employee Gerry Lane traverses the world in a race against time to stop a zombie pandemic that is toppling armies and governments and threatens to destroy humanity itself.

Director:

Marc Forster

|

Stars:

Brad Pitt,

Mireille Enos,

Daniella Kertesz,

James Badge Dale

Votes:

683,566

| Gross:

$202.36M

18+

|

111 min

|

Horror, Mystery

65

Metascore

A year after the murder of her mother, a teenage girl is terrorized by a masked killer who targets her and her friends by using scary movies as part of a deadly game.

Director:

Wes Craven

|

Stars:

Neve Campbell,

Courteney Cox,

David Arquette,

Skeet Ulrich

Votes:

359,415

| Gross:

$103.05M

18+

|

91 min

|

Horror

76

Metascore

Teenager Nancy Thompson must uncover the dark truth concealed by her parents after she and her friends become targets of the spirit of a serial killer with a bladed glove in their dreams, in which if they die, it kills them in real life.

Director:

Wes Craven

|

Stars:

Heather Langenkamp,

Johnny Depp,

Robert Englund,

John Saxon

Votes:

246,685

| Gross:

$25.50M

18+

|

91 min

|

Horror, Thriller

87

Metascore

Fifteen years after murdering his sister on Halloween night 1963, Michael Myers escapes from a mental hospital and returns to the small town of Haddonfield, Illinois to kill again.

Director:

John Carpenter

|

Stars:

Donald Pleasence,

Jamie Lee Curtis,

Tony Moran,

Nancy Kyes

Votes:

287,170

| Gross:

$47.00M

16+

|

83 min

|

Horror

87

Metascore

Five friends head out to rural Texas to visit the grave of a grandfather. On the way they stumble across what appears to be a deserted house, only to discover something sinister within. Something armed with a chainsaw.

Director:

Tobe Hooper

|

Stars:

Marilyn Burns,

Edwin Neal,

Allen Danziger,

Paul A. Partain

Votes:

168,921

| Gross:

$30.86M

16+

|

109 min

|

Horror, Mystery, Thriller

97

Metascore

A Phoenix secretary embezzles $40,000 from her employer’s client, goes on the run and checks into a remote motel run by a young man under the domination of his mother.

Director:

Alfred Hitchcock

|

Stars:

Anthony Perkins,

Janet Leigh,

Vera Miles,

John Gavin

Votes:

683,209

| Gross:

$32.00M

18+

|

146 min

|

Drama, Horror

66

Metascore

A family heads to an isolated hotel for the winter where a sinister presence influences the father into violence, while his psychic son sees horrific forebodings from both past and future.

Director:

Stanley Kubrick

|

Stars:

Jack Nicholson,

Shelley Duvall,

Danny Lloyd,

Scatman Crothers

Votes:

1,041,834

| Gross:

$44.02M

16+

|

85 min

|

Action, Adventure, Horror

64

Metascore

A group of friends venture deep into the streets of New York on a rescue mission during a rampaging monster attack.

Director:

Matt Reeves

|

Stars:

Mike Vogel,

Jessica Lucas,

Lizzy Caplan,

T.J. Miller

Votes:

406,801

| Gross:

$80.05M

18+

|

101 min

|

Action, Horror

59

Metascore

A nurse, a policeman, a young married couple, a salesman and other survivors of a worldwide plague that is producing aggressive, flesh-eating zombies, take refuge in a mega Midwestern shopping mall.

Director:

Zack Snyder

|

Stars:

Sarah Polley,

Ving Rhames,

Mekhi Phifer,

Jake Weber

Votes:

260,942

| Gross:

$59.02M

16+

|

90 min

|

Mystery, Thriller

64

Metascore

Stranded at a desolate Nevada motel during a nasty rain storm, ten strangers become acquainted with each other when they realize that they’re being killed off one by one.

Director:

James Mangold

|

Stars:

John Cusack,

Ray Liotta,

Amanda Peet,

John Hawkes

Votes:

254,913

| Gross:

$52.16M

12+

|

119 min

|

Drama, Horror, Mystery

52

Metascore

A reporter is drawn to a small West Virginia town to investigate a series of strange events, including psychic visions and the appearance of bizarre entities.

Director:

Mark Pellington

|

Stars:

Richard Gere,

Laura Linney,

David Eigenberg,

Bob Tracey

Votes:

82,132

| Gross:

$35.75M

12+

|

105 min

|

Fantasy, Horror, Mystery

65

Metascore

Ichabod Crane is sent to Sleepy Hollow to investigate the decapitations of three people, with the culprit being the legendary apparition, The Headless Horseman.

Director:

Tim Burton

|

Stars:

Johnny Depp,

Christina Ricci,

Miranda Richardson,

Michael Gambon

Votes:

368,307

| Gross:

$101.07M

R

|

100 min

|

Horror, Mystery, Thriller

49

Metascore

A group of students go to the location of the infamous Dyatlov pass incident to make a documentary, but things take a turn for the worse as the secret of what happened there is revealed.

Director:

Renny Harlin

|

Stars:

Holly Goss,

Matt Stokoe,

Luke Albright,

Ryan Hawley

Votes:

26,082

R

|

112 min

|

Action, Adventure, Drama

46

Metascore

And suddenly, overnight, the world came to a halt. Two men, two survivors, one kid, and hatred that separates them. A place forgotten by everyone, including the creatures that inhabit the Earth… until now.

Director:

Miguel Ángel Vivas

|

Stars:

Matthew Fox,

Jeffrey Donovan,

Quinn McColgan,

Clara Lago

Votes:

17,416

79 min

|

Drama, Horror

75

Metascore

Upon entering his fiancée’s family mansion, a man discovers a savage family curse and fears that his future brother-in-law has entombed his bride-to-be prematurely.

Director:

Roger Corman

|

Stars:

Vincent Price,

Mark Damon,

Myrna Fahey,

Harry Ellerbe

Votes:

14,057

| Gross:

$3.16M

14+

|

116 min

|

Action, Adventure, Sci-Fi

73

Metascore

An alien invasion threatens the future of humanity. The catastrophic nightmare is depicted through the eyes of one American family fighting for survival.

Director:

Steven Spielberg

|

Stars:

Tom Cruise,

Dakota Fanning,

Tim Robbins,

Miranda Otto

Votes:

457,694

| Gross:

$234.28M

18+

|

134 min

|

Horror, Mystery, Thriller

65

Metascore

Ed and Lorraine Warren travel to North London to help a single mother raising four children alone in a house plagued by a supernatural spirit.

Director:

James Wan

|

Stars:

Vera Farmiga,

Patrick Wilson,

Madison Wolfe,

Frances O’Connor

Votes:

279,325

| Gross:

$102.47M

16+

|

106 min

|

Horror, Mystery, Thriller

40

Metascore

The Lamberts believe that they have defeated the spirits that have haunted their family, but they soon discover that evil is not beaten so easily.

Director:

James Wan

|

Stars:

Patrick Wilson,

Rose Byrne,

Barbara Hershey,

Lin Shaye

Votes:

175,530

| Gross:

$83.59M

«Horror Movie» redirects here. For the Skyhooks song, see Horror Movie (song).

Horror is a film genre that seeks to elicit fear or disgust in its audience for entertainment purposes.[2]

Horror films often explore dark subject matter and may deal with transgressive topics or themes. Broad elements include monsters, apocalyptic events, and religious or folk beliefs. Cinematic techniques used in horror films have been shown to provoke psychological reactions in an audience.

Horror films have existed for more than a century. Early inspirations from before the development of film include folklore, religious beliefs and superstitions of different cultures, and the Gothic and horror literature of authors such as Edgar Allan Poe, Bram Stoker, and Mary Shelley. From origins in silent films and German Expressionism, horror only became a codified genre after the release of Dracula (1931). Many sub-genres emerged in subsequent decades, including body horror, comedy horror, slasher films, supernatural horror and psychological horror. The genre has been produced worldwide, varying in content and style between regions. Horror is particularly prominent in the cinema of Japan, Korea, Italy and Thailand, among other countries.

Despite being the subject of social and legal controversy due to their subject matter, some horror films and franchises have seen major commercial success, influenced society and spawned several popular culture icons.

Characteristics

The Dictionary of Film Studies defines the horror film as representing «disturbing and dark subject matter, seeking to elicit responses of fear, terror, disgust, shock, suspense, and, of course, horror from their viewers.»[2] In the chapter «The American Nightmare: Horror in the 70s» from Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan (2002), film critic Robin Wood declared that commonality between horror films are that «normality is threatened by the monster.»[3] This was further expanded upon by The Philosophy of Horror, or Parodoxes of the Heart by Noël Carroll who added that «repulsion must be pleasurable, as evidenced by the genre’s popularity.»[3]

Prior to the release of Dracula (1931), historian Gary Don Rhodes explained that the idea and terminology of horror film did not exist yet as a codified genre, although critics used the term «horror» to describe films in reviews prior to Dracula‘s release.[4] «Horror» was a term used to describe a variety of meanings. In 1913, Moving Picture World defined «horrors» as showcasing «striped convicts, murderous Indians, grinning ‘black-handers’, homicidal drunkards»[5] Some titles that suggest horror such as The Hand of Horror (1914) was a melodrama about a thief who steals from his own sister.[5] During the silent era, the term horror was used to describe everything from «battle scenes» in war films to tales of drug addiction.[6] Rhodes concluded that the term «horror film» or «horror movie» was not used in early cinema.[7]

The mystery film genre was in vogue and early information on Dracula being promoted as mystery film was common, despite the novel, play and film’s story relying on the supernatural.[8] Newman discussed the genre in British Film Institute’s Companion to Horror where he noted that Horror films in the 1930s were easy to identify, but following that decade «the more blurred distinctions become, and horror becomes less like a discrete genre than an effect which can be deployed within any number of narrative settings or narratives patterns».[9]

Various writings on genre from Altman, Lawrence Alloway (Violent America: The Movies 1946-1964 (1971)) and Peter Hutchings (Approaches to Popular Film (1995)) implied it easier to view films as cycles opposed to genres, suggesting the slasher film viewed as a cycle would place it in terms of how the film industry was economically and production wise, the personnel involved in their respective eras, and how the films were marketed exhibited and distributed.[10]

Mark Jancovich in an essay declared that «there is no simple ‘collective belief’ as to what constitutes the horror genre» between both fans and critics of the genre.[11] Jancovich found that disagreements existed from audiences who wanted to distinguish themselves. This ranged from fans of different genres who may view a film like Alien (1979) as belonging to science fiction, and horror fan bases dismissing it as being inauthentic to either genre.[12] Further debates exist among fans of the genre with personal definitions of «true» horror films, such as fans who embrace cult figures like Freddy Kruger of the A Nightmare on Elm Street series, while others disassociate themselves from characters and series and focusing on genre auteur directors like Dario Argento, while others fans would deem Argento’s films as too mainstream, having preferences more underground films.[13] Andrew Tudor wrote in Monsters and Mad Scientists: A Cultural History of the Horror Movie suggested that «Genre is what we collectively believe it to be»[14]

Cinematic techniques

Depiction of the usage of mirrors in horror films.

In a study by Jacob Shelton, the many ways that audience members are manipulated through horror films was investigated in detail.[15] Negative space is one such method that can play a part in inducing a reaction, causing one’s eyes to remotely rest on anything in the frame – a wall, or the empty black void in the shadows.[15]

The jump scare is a horror film trope, where an abrupt change in image accompanied with a loud sound intends to surprise the viewer.[15] This can also be subverted to create tension, where an audience may feel more unease and discomfort by anticipating a jump scare.[15]

Mirrors are often used in horror films is to create visual depth and build tension. Shelton argues mirrors have been used so frequently in horror films that audiences have been conditioned to fear them, and subverting audience expectations of a jump scare in a mirror can further build tension.[15] Tight framing and close-ups are also commonly used; these can build tension and induce anxiety by not allowing the viewer to see beyond what is around the protagonist.[15]

Music

Music is a key component of horror films. In Music in the Horror Film (2010), Lerner writes «music in horror film frequently makes us feel threatened and uncomfortable» and intends to intensify the atmosphere created in imagery and themes. Dissonance, atonality and experiments with timbre are typical characteristics used by composers in horror film music.[16]

Themes

Charles Derry proposed the three key components of horror are that of personality, Armageddon and the demonic.

In the book Dark Dreams, author Charles Derry conceived horror films as focusing on three broad themes: the horror of personality, horror of Armageddon and the horror of the demonic.[17] The horror of personality derives from monsters being at the centre of the plot, such Frankenstein’s monster whose psychology makes them perform unspeakable horrific acts ranging from rapes, mutilations and sadistic killings.[17] Other key works of this form are Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, which feature psychotic murderers without the make-up of a monster.[17] The second ‘Armageddon’ group delves on the fear of large-scale destruction, which ranges from science fiction works but also of natural events, such as Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963).[17] The last group of the «Fear of the Demonic» features graphic accounts of satanic rites, witchcraft, exorcisms outside traditional forms of worship, as seen in films like The Exorcist (1973) or The Omen (1976).[18]

Some critics have suggested horror films can be a vessel for exploring contemporary cultural, political and social trends. Jeanne Hall, a film theorist, agrees with the use of horror films in easing the process of understanding issues by making use of their optical elements.[19] The use of horror films can help audiences understand international prior historical events occurs, for example, to depict the horrors of the Vietnam War, the Holocaust, the worldwide AIDS epidemic[20] or post-9/11 pessimism.[21] In many occurrences, the manipulation of horror presents cultural definitions that are not accurate,[according to whom?] yet set an example to which a person relates to that specific cultural from then on in their life.[clarification needed][22]

History

In his book Caligari’s Children: The Film as Tale of Terror (1980), author Siegbert Solomon Prawer stated that those wanting to read into horror films in a linear historical path, citing historians and critics like Carlos Clarens noting that as some film audiences at a time took films made by Tod Browning that starred Bela Lugosi with utmost seriousness, other productions from other countries saw the material set for parody, as children’s entertainment or nostalgic recollection.[17] John Kenneth Muir in his books covering the history of horror films through the later decades of the 20th century echoed this statement, stating that horror films mirror the anxieties of «their age and their audience» concluding that «if horror isn’t relevant to everyday life… it isn’t horrifying».[23]

Early influences and films

Beliefs in the supernatural, devils and ghosts have existed in folklore and religions of many cultures for centuries; these would go on to become integral parts of the horror genre.[24] Zombies, for example, originated from Haitian folklore.[25] Prior to the development of film in the late 1890s, Gothic fiction was developed.[26] These included Frankenstein (1818) and short stories by Edgar Allan Poe, which would later have several film adaptations.[27] By the late 1800s and early 1900s, more key horror texts would be developed than any other period preceding it.[28] While they were not all straight horror stories, the horrific elements of them lingered in popular culture, with their set pieces becoming staples in horror cinema.[29]

Critic and author Kim Newman described Georges Méliès Le Manoir du diable as the first horror film, featuring elements that would become staples in the genre: images of demons, ghosts, and haunted castles.[30]

The early 20th century cinema had production of film so hectic, several adaptions of stories were made within months of each other.[31] This included Poe adaptations made in France and the United States, to Frankenstein adaptations being made in the United States and Italy.[32] The most adapted of these stories was Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), which had three version made in 1920 alone.[31]

Early German cinema involved Poe-like stories, such as The Student of Prague (1913) which featured director and actor Paul Wegener. Wegner would go on to work in similar features such as The Golem and the Dancing Girl and its related Golem films.[32] Other actors of the era who featured in similar films included Werner Krauss and Conrad Veidt who starred in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, leading to similar roles in other German productions.[1] F. W. Murnau would also direct an adaptation of Nosferatu (1922), a film Newman described as standing «as the only screen adaptation of Dracula to be primarily interested in horror, from the character’s rat-like features and thin body, the film was, even more so than Caligari, «a template for the horror film.»[1]

1930s

Bela Lugosi in Dracula (1931), a film noted as inspiring a wave of subsequent American horror films in the 1930s.

Following the 1927 success of Broadway play of Dracula, Universal Studios officially purchased the rights to both the play and the novel.[33][34][35] After the Dracula‘s premiere on February 12, 1931, the film received what authors of the book Universal Horrors proclaimed as «uniformly positive, some even laudatory» reviews.[36] The commercial reception surprised Universal who forged ahead to make similar production of Frankenstein (1931).[37][38] Frankenstein also proved to be a hit for Universal which led to both Dracula and Frankenstein making film stars of their leads: Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff respectively.[39] Karloff starred in Universal’s follow-up The Mummy (1932), which Newman described as the studio knowing «what they were getting» patterning the film close to the plot of Dracula.[39] Lugosi and Karloff would star together in several Poe-adaptations in the 1930s.[40]

Following the release of Dracula, The Washington Post declared the film’s box office success led to a cycle of similar films while The New York Times stated in a 1936 overview that Dracula and the arrival of sound film began the «real triumph of these spectral thrillers».[41] Other studios began developing their own horror projects with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Paramount Pictures, and Warner Bros.[42] Universal would also follow-up with several horror films until the mid-1930s.[39][42]

In 1935, the President of the BBFC Edward Shortt, wrote «although a separate category has been established for these [horrific] films, I am sorry to learn they are on the increase…I hope that the producers and renters will accept this word of warning, and discourage this type of subject as far as possible.»[43] As the United Kingdom was a significant market for Hollywood, American producers listened to Shortt’s warning, and the number of Hollywood produced horror films decreased in 1936.[43] A trade paper Variety reported that Universal Studios abandonment of horror films after the release of Dracula’s Daughter (1936) was that «European countries, especially England are prejudiced against this type product [sic].»[43] At the end of the decade, a profitable re-release of Dracula and Frankenstein would encourage Universal to produce Son of Frankenstein (1939) featuring both Lugosi and Karloff, starting off a resurgence of the horror film that would continue into the mid-1940s.[44]

1940s

After the success of Son of Frankenstein (1939), Universal’s horror films received what author Rick Worland of The Horror Film called «a second wind» and horror films continued to be produced at a feverish pace into the mid-1940s.[45] Universal looked into their 1930s horror properties to develop new follow-ups such as their The Invisible Man and The Mummy series.[46] Universal saw potential in making actor Lon Chaney, Jr. a new star to replace Karloff as Chaney had not distinguished himself in either A or B pictures.[47] Chaney, Jr. would become a horror star for the decade showing in the films in The Wolf Man series, portraying several of Universal’s monster characters.[46] B-Picture studios also developed films that imitated the style of Universal’s horror output. Karloff worked with Columbia Pictures acting in various films as a «Mad doctor»-type characters starting with The Man They Could Not Hang (1939) while Lugosi worked between Universal and poverty row studios such as Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC) for The Devil Bat (1941) and Monogram for nine features films.[48]

In March 1942, producer Val Lewton ended his working relationship with independent producer David O. Selznick to work for RKO Radio Pictures’ Charles Koerner, becoming the head of a new unit created to develop B-movie horror feature films.[49][50] According to screenwriter DeWitt Bodeen and director Jacques Tourneur, Lewton’s first horror production Cat People (1942), Lewton wanted to make some different from the Universal horror with Tourneu describing it as making «something intelligent and in good taste».[51] Lewton developed a series of horror films for RKO, described by Newman as «polished, doom-haunted, poetic» while film critic Roger Ebert the films Lewton produced in the 1940s were «landmark[s] in American movie history».[52] Several horror films of the 1940s borrowed from Cat People, specifically feature a female character who fears that she has inherited the tendency to turn into a monster or attempt to replicate the shadowy visual style of the film.[53] Between 1947 and 1951, Hollywood made almost no new horror films.[54] This was due to sharply declining sales, leading to both major and poverty row studios to re-release their older horror films during this period rather than make new ones.[55][56]

1950s

The early 1950s featured only a few gothic horror films developed, prior to the release of Hammer Film Productions’s gothic films,[57] Hammer originally began developing American-styled science fiction films in the early 1950s but later branched into horror with their colour films The Curse of Frankenstein and Dracula (1958).[58][59] These films would birth two horror film stars: Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing and led to further horror film production from Hammer in the decade.[59]

Among the most influential horror films of the 1950s was The Thing From Another World (1951), with Newman stating that countless science fiction horror films of the 1950s would follow in its style.[60] For five years following the release of The Thing From Another World, nearly every film involving aliens, dinosaurs or radioactive mutants would be dealt with matter-of-fact characters as seen in the film.[60] Films featuring vampires, werewolves, and Frankenstein’s monster also took to having science fiction elements of the era such as have characters have similar plot elements from Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.[61] Horror films also expanded further into international productions in the later half of the 1950s, with films in the genre being made in Mexico, Italy, Germany and France.[62]

1960s

The horror film changed dramatically in 1960, specifically, with Alfred Hitchcock’s film Psycho (1960) based on the novel by Robert Bloch. Newman declared that the film elevated the idea of a multiple-personality serial killer that set the tone future film that was only touched upon in earlier melodramas and film noirs.[63][64] The release of Psycho led to similar pictures about the psychosis of characters and a brief reappearance of what Newman described as «stately, tasteful» horror films such as Jack Clayton’s The Innocents (1961) and Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1963).[65] Newman described Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968) the other «event» horror film of the 1960s after Psycho.[66]

Roger Corman working with AIP to make House of Usher (1960), which led several future Poe-adaptations other 1960s Poe-adaptations by Corman, and provided roles for aging horror stars such as Karloff and Chaney, Jr. These films were made to compete with the British colour horror films from Hammer in the United Kingdom featuring their horror stars Cushing and Fisher, whose Frankenstein series continued from 1958 to 1973[63] Competition for Hammer appeared in the mid-1960s in the United Kingdom with Amicus Productions who also made feature film featuring Cushing and Lee.[63] Like Psycho, Amicus drew from contemporary sources such as Bloch (The Skull (1965) and Torture Garden (1967)) led to Hammer adapting works by more authors from the era.[63]

Mario Bava’s Black Sunday (1960) marked an increase in onscreen violence in film.[67] Earlier British horror films had their gorier scenes cut on initial release or suggested through narration while Psycho suggested its violence through fast editing.[68] Black Sunday, by contrast, depicted violence without suggestion.[67] This level of violence would later be seen in other works of Bava and other Italian films such the giallo of Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci.[67] Other independent American productions of the 1960s expanded on the gore shown in the films in a genre later described as the splatter film, with films by Herschell Gordon Lewis such as Blood Feast, while Newman found that the true breakthrough of these independent films was George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) which set a new attitudes for the horror film, one that was suspicious of authority figures, broke taboos of society and was satirical between its more suspenseful set pieces.[66]

1970s

Historian John Kenneth Muir described the 1970s as a «truly eclectic time» for horror cinema, noting a mixture of fresh and more personal efforts on film while other were a resurrection of older characters that have appeared since the 1930s and 1940s.[70] Night of the Living Dead had what Newman described as a «slow burning influence» on horror films of the era and what he described as «the first of the genre auteurs» who worked outside studio settings.[71] These included American directors such as John Carpenter, Tobe Hooper, Wes Craven and Brian De Palma as well as directors working outside America such as Bob Clark, David Cronenberg and Dario Argento.[71] Prior to Night of the Living Dead, the monsters of horror films could easily be banished or defeated by the end of the film, while Romero’s film and the films of other filmmakers would often suggest other horror still lingered after the credits.[69]

Both Amicus and Hammer ceased feature film production in the 1970s.[72][73] Remakes of proved to be popular choices for horror films in the 1970s, with films like Invasion of the Bodysnatchers (1978) and tales based on Dracula which continued into the late 1970s with John Badham’s Dracula (1979) and Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979).[74][75] Although not an official remake, the last high-grossing horror film of decade, Alien (1979) took b-movie elements from films like It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958).[76] Newman has suggested high grossing films like Alien, Jaws (1975) and Halloween (1978) became hits by being «relentless suspense machines with high visual sophistication.»[76] He continued that Jaws‘ memorable music theme and its monster not being product of society like Norman Bates in Psycho had carried over into Halloween‘s Michael Myers and its films theme music.[77]

1980s

With the appearance of home video in the 1980s, horror films were subject to censorship in the United Kingdom in a phenomenon popularly known as «video nasties», leading to video collections being seized by police and some people being jailed for selling or owning some horror films.[78] Newman described the response to the video nasty issue led to horror films becoming «dumber than the previous decade» and although films were not less gory, they were «more lightweight […] becoming more disposable, less personal works.»[79][78] Newman noted that these directors who created original material in the 1970s such as Carpenter, David Cronenberg, and Tobe Hooper would all at least briefly «play it safe» with Stephen King adaptations or remakes of the 1950s horror material.[80]

Replacing Frankenstein’s monster and Dracula were new popular characters with more general names like Jason Voorhees (Friday the 13th), Michael Myers (Halloween), and Freddy Kruger (A Nightmare on Elm Street). Unlike the characters of the past who were vampires or created by mad scientists, these characters were seemingly people with common sounding names who developed the slasher film genre of the era.[81] The genre was derided by several contemporary film critics of the era such as Roger Ebert, and often were highly profitable in the box office.[82] The 1980s highlighted several films about body transformation, through special effects and make-up artists like Rob Bottin and Rick Baker who allowed for more detailed and graphic transformation scenes or the human body in various forms of horrific transformation.[83][84]

Other more traditional styles continued into the 1980s, such as supernatural themed films involving haunted houses, ghosts, and demonic possession.[85] Among the most popular films of the style included Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), Hooper’s high-grossing Poltergeist (1982).[86] After the release of films based on Stephen King’s books like The Shining and Carrie led to further film adaptations of his novels throughout the 1980s.[87][88]

1990s

Some cast and crew members of The Blair Witch Project (1999), one of the highest grossing horror films of the 1990s.

Horror films of the 1990s also failed to develop as many major new directors of the genre as it had in the 1960s or 1970s.[89] Young independent filmmakers such as Kevin Smith, Richard Linklater, Michael Moore and Quentin Tarantino broke into cinema outside the genre at non-genre festivals like the Sundance Film Festival.[90] Newman noted that the early 1990s was «not a good time for horror», noting excessive release of sequels.[91] Muir commented that in the 1990s after the end of the Cold War, the United States did not really have a «serious enemy» internationally, leading to horror films adapting to fictional enemies predominantly within America, with the American government, large businesses, organized religion and the upper class as well as supernatural and occult items such as vampires or Satanists filling in the horror villains of the 1990s.[92] The rapid growth of technology in the 1990s with the internet and the fears of the Year 2000 problem causing the end of the world were reflected in plots of films.[93]

Other genre-based trends of the 1990s, included the post-modern horror films such as Scream (1996) were made in this era.[94] Post-modern horror films continued into the 2000s, eventually just being released as humorous parody films.[95] By the end of the 1990s, three films were released that Newman described as «cultural phenomenons.»[96] These included Hideo Nakata’s Ring (1998), which was the major hit across Asia, The Sixth Sense, another ghost story which Newman described as making «an instant cliche» of twist endings, and the low-budget independent film The Blair Witch Project (1999).[96] Newman described the first trend of horror films in the 2000s followed the success of The Blair Witch Project, but predominantly parodies or similar low-budget imitations.[97]

2000s

Teen oriented series began in the era with Final Destination while the success of the 1999 remake of William Castle’s House on Haunted Hill led to a series of remakes in the decade.[98] The popularity of the remake of Dawn of the Dead (2004) led to a revival in American zombie films in the late 2000s. Beyond remakes, other long-dormant horror franchises such as The Exorcist and Friday the 13th received new feature films.[99] After the success of Ring (1998), several films came from Hong Kong, South Korea, Thailand, and Japan with similar detective plotlines investigating ghosts.[100] This trend was echoed in the West with films with similar plots and Hollywood remakes of Asian films like The Ring (2002).[101] In the United Kingdom, there was what Newman described as a «modest revival» of British horror films, first with war-related horror films and several independent films of various styles, with Newman describing the «breakouts of the new British horror» including 28 Days Later (2002) and Shaun of the Dead (2004).[101]

David Edelstein of The New York Times coined a term for a genre he described as «torture porn» in a 2006 article, as a label for films described, often retroactively, to over 40 films since 2003.[102] Edelstein lumped in films such as Saw (2004) and Wolf Creek (2005) under this banner suggesting audience a «titillating and shocking»[103] while film scholars of early 21st century horror films described them as «intense bodily acts and visible bodily representations» to produce uneasy reactions.[103] Kevin Wetmore, using the Saw film series suggested these film suggested reflected a post-9/11 attitude towards increasing pessimism, specifically one of «no redemption, no hope, no expectations that ‘we’re going to be OK'»[21]

2010s to present

After the film studio Blumhouse had success with Paranormal Activity (2007), the studio continued to produce films became hits in the 2010s with film series Insidious.[104] This led to what Newman described as the companies policy on «commercial savvy with thematic risk that has often paid off», such as Get Out (2017) and series like The Purge.[104][105] Laura Bradley in her article for Vanity Fair noted that both large and small film studios began noticing Blumhouse’s success, including A24, which became popular with films like The Witch (2015) and Midsommar (2019).[104] Bradley commented how some of these films had been classified as «elevated horror», a term used for works that were ‘elevated’ beyond traditional or pure genre films, but declared «horror aficionados and some critics pushed back against the notion that these films are doing something entirely new» noting their roots in films like Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Rosemary’s Baby (1968).[104] The increase in use of streaming services in the 2010s has also been suggested as boosting the popularity of horror; as well as Netflix and Amazon Prime Video producing and distributing numerous works in the genre, Shudder launched in 2015 as a horror-specific service.[106] In the early 2010s, a wave of horror films began exhibiting what Virginie Sélavy described as psychedelic tendency. This was inspired by experimentation and subgenres of the 1970s, specifically folk horror.[107] The trend began with Enter the Void (2009) and Beyond the Black Rainbow (2010) and continued throughout the decade with films like Climax (2018).[107]

Adapted from the Stephen King novel, It (2017) set a box office record for horror films by grossing $123.1 million on opening weekend in the United States and nearly $185 million globally.[108] The success of It led to further King novels being adapted into new feature films.[109] The beginning of 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact on the film industry, leading to several horror films being held back from release, or having their production halted.[110] During lockdowns, streaming for films featuring a fictional apocalypse increased.[111]

Sub-genres of horror films

Horror is a malleable genre and often can be altered to accommodate other genre types such as science fiction, making some films difficult to categorize.[112]

Body horror

A genre that emerged in the 1970s, body horror films focus on the process of a bodily transformation. In these films, the body is either engulfed by some larger process or heading towards fragmentation and collapse.[113][114] In these films, the focus can be on apocalyptic implication of an entire society being overtaken, but the focus is generally upon an individual and their sense of identity, primarily them watching their own body change.[113] The earliest appearance of the sub-genre was the work of director David Cronenberg, specifically with early films like Shivers (1975).[113][114] Mark Jancovich of the University of Manchester declared that the transformation scenes in the genre provoke fear and repulsion, but also pleasure and excitement such as in The Thing (1982) and The Fly (1986).[115]

Comedy horror

Comedy horror combines elements of comedy and horror film. The comedy horror genre often crosses over with the black comedy genre. It occasionally includes horror films with lower ratings that are aimed at a family audience. The short story The Legend of Sleepy Hollow by Washington Irving is cited as «the first great comedy-horror story».[116]

Folk horror

Folk horror uses elements of folklore or other religious and cultural beliefs to instil fear in audiences. Folk horror films have featured rural settings and themes of isolation, religion and nature.[117][118] Frequently cited examples are Witchfinder General (1968), The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), The Wicker Man (1973) and Midsommar (2019).[117][118] Local folklore and beliefs have been noted as being prevalent in horror films from the Southeast Asia region, including Thailand and Indonesia.[119][120]

Found footage horror

The found footage horror film «technique» gives the audience a first person view of the events on screen, and presents the footage as being discovered after. Horror films which are framed as being made up of «found-footage» merge the experiences of the audience and characters, which may induce suspense, shock, and bafflement.[121] Alexandra Heller-Nicholas noted that the popularity of sites like YouTube in 2006 sparked a taste for amateur media, leading to the production of further films in the found footage horror genre later in the 2000s including the particularly financially successful Paranormal Activity (2007).[122]

Gothic horror

In their book Gothic film, Richard J. McRoy and Richard J. Hand stated that «Gothic» can be argued as a very loose subgenre of horror, but argued that «Gothic» as a whole was a style like film noir and not bound to certain cinematic elements like the Western or science fiction film.[123] The term «gothic» is frequently used to describe a stylized approach to showcasing location, desire, and action in film. Contemporary views of the genre associate it with imagery of castles at hilltops and labyrinth like ancestral mansions that are in various states of disrepair.[124] Narratives in these films often focus on an audiences fear and attraction to social change and rebellion.[125] The genre can be applied to films as early as The Haunted Castle (1896), Frankenstein (1910) as well as to more complex iterations such as Park Chan-wook’s Stoker (2013) and Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017).[123]

The gothic style is applied to several films throughout the history of the horror film. This includes Universal Pictures’ horror films of the 1930s, the revival of gothic horror in the 1950s and 1960s with films from Hammer, Roger Corman’s Poe-cycle, and several Italian productions.[126] By the 1970s American and British productions often had vampire films set in a contemporary setting, such as Hammer Films had their Dracula stories set in a modern setting and made other horror material which pushed the erotic content of their vampire films that was initiated by Black Sunday.[127][128][67] In the 1980s, the older horror characters of Dracula and Frankenstein’s monster rarely appeared, with vampire themed films continued often in the tradition of authors like Anne Rice where vampirism becomes a lifestyle choice rather than plague or curse.[129] Following the release of Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), a small wave of high-budgeted gothic horror romance films were released in the 1990s.[130]

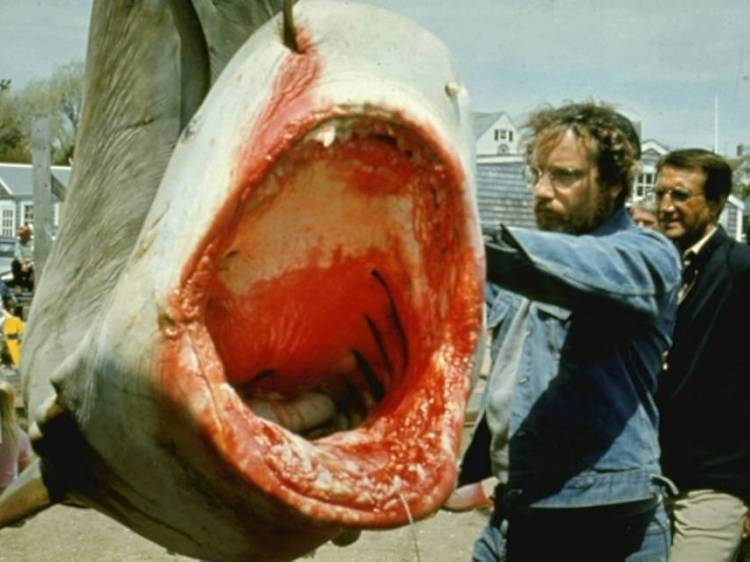

Natural horror

Also described as «eco-horror», the natural horror film is a subgenre «featuring nature running amok in the form of mutated beasts, carnivorous insects, and normally harmless animals or plants turned into cold-blooded killers.»[131][132] In 1963, Hitchcock defined a new genre nature taking revenge on humanity with The Birds (1963) that was expanded into a trend into the 1970s. Following the success of Willard (1971), a film about killer rats, 1972 had similar films with Stanley (1972) and an official sequel Ben (1972).[133] Other films followed in suit such as Night of the Lepus (1972), Frogs (1972), Bug (1975), Squirm (1976) and what Muir described as the «turning point» in the genre with Jaws (1975), which became the highest-grossing film at that point and moved the animal attacks genres «towards a less-fantastic route» with less giant animals and more real-life creatures such as Grizzly (1976) and Night Creature (1977), Orca (1977), and Jaws 2 (1978).[133][134][135] The film is linked with the environmental movements that became more mainstream in the 1970s and early 1980s such vegetarianism, animal rights movements, and organizations such as Greenpeace.[136] Following Jaws, sharks became the most popular animal of the genre, ranging from similar such as Mako: The Jaws of Death (1976) and Great White (1981) to the Sharknado film series.[136] James Marriott found that the genre had «lost momentum» since the 1970s while the films would still be made towards the turn of the millennium.[137]

Slasher film

The slasher film is a horror subgenre, which involving a killer murdering a group of people (usually teenagers), usually by use of bladed tools.[138] In his book on the genre, author Adam Rockoff that these villains represented a «rogue genre» of films with «tough, problematic, and fiercely individualistic.»[139] Following the financial success of Friday the 13th (1980), at least 20 other slasher films appeared in 1980 alone.[78] These films usually revolved around five properties: unique social settings (campgrounds, schools, holidays) and a crime from the past committed (an accidental drowning, infidelity, a scorned lover) and a ready made group of victims (camp counselors, students, wedding parties).[140] The genre was derided by several contemporary film critics of the era such as Ebert, and often were highly profitable in the box office.[82] The release of Scream (1996), led to a brief revival of the slasher films for the 1990s.[141] Other countries imitated the American slasher film revival, such as South Korea’s early 2000s cycle with Bloody Beach (2000), Nightmare (2000) and The Record (2000).[142]

Supernatural horror

Supernatural horror films integrate supernatural elements, such as the afterlife, spirit possession and religion into the horror genre.[143]

Teen horror

Teen horror is a horror subgenre that victimizes teenagers while usually promoting strong, anti-conformity teenage leads, appealing to young generations. This subgenre often depicts themes of sex, under-aged drinking, and gore.[144] Horror films aimed a young audience featuring teenage monsters grew popular in the 1950s with several productions from American International Pictures (AIP) and productions of Herman Cohen with I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957) and I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957).[59] This led to later productions like Daughter of Dr. Jekyll (1957) and Frankenstein’s Daughter (1958).[59] Teen horror cycle in the 1980s often showcased explicit gore and nudity, with John Kenneth Muir described as cautionary conservative tales where most of the films stated if you partook in such vices such as drugs or sex, your punishment of death would be handed out.[145]

Prior to Scream, there were no popular teen horror films in the early 1990s.[146] After the financial success of Scream, teen horror films became increasingly reflexive and self-aware until the end of the 1990s with films like I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997) and non-slasher The Faculty (1998).[147][146] The genre lost prominence as teen films dealt with threats with more realism in films like Donnie Darko (2001) and Crazy/Beautiful (2001).[148] In her book on the 1990s teen horror cycle, Alexandra West described the general trend of these films is often looked down upon by critics, journals, and fans as being too glossy, trendy, and sleek to be considered worthwhile horror films.[149]

Psychological horror

Psychological horror is a subgenre of horror and psychological fiction with a particular focus on mental, emotional, and psychological states to frighten, disturb, or unsettle its audience. The subgenre frequently overlaps with the related subgenre of psychological thriller, and often uses mystery elements and characters with unstable, unreliable, or disturbed psychological states to enhance the suspense, drama, action, and paranoia of the setting and plot and to provide an overall unpleasant, unsettling, or distressing atmosphere.[150]

Regional horror films

Asian horror films

Horror films in Asia have been noted as being inspired by national, cultural or religious folklore, particularly beliefs in ghosts or spirits.[119][24] In Asian Horror, Andy Richards writes that there is a «widespread and engrained acceptance of supernatural forces» in many Asian cultures, and suggests this is related to animist, pantheist and karmic religious traditions, as in Buddhism and Shintoism.[24] Although Chinese, Japanese, Thai and Korean horror has arguably received the most international attention,[24] horror also makes up a considerable proportion of Cambodian[151] and Malaysian cinema.[152]

Hong Kong

The Hong Kong film industry has long been associated with genre cinema, specifically for action films.[153] The Hong Kong horror films are generally broad and often feature demons, wraiths and reanimated corpses and have been described by authors Gary Bettinson and Daniel Martin as «generically diffuse and resistant to Western definitions.»[154] This was due to Hong Kong cinema often creating various hybrid films which mesh traditional horror films with elements of other genres such as A Chinese Ghost Story (1987), which led to Hong Kong critic Chen Yu to suggest that this form was «one more indication of the Hong Kong cinema’s inability to establish a proper horror genre.»[155]

Various interpretations of the Hong Kong horror film have included Bettinson and Martin stating that Hong Kong films frequently prioritize comedy and romance over fear.[156] Author Felicia Chan described Hong Kong cinema as being noted for its extensive use of parody and pastiche and the horror and ghost films of Hong Kong often turn to comedy and generally follow forms of ghost erotica and jiangshi (transl. stiff corpses).[157] Early horror-related cinema in Mandarin and Cantonese featured ghost stories that occasionally had rational explanations.[158] The literary source of Hong Kong horror films is Pu Songling’s Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, a series of short stories with supernatural themes written in the 17th century.[159][160] Unlike Western stories, Pu focuses on the value of the human form which is essential for reincarnation, leading to stories about ghosts such as Fox spirit trying to seal a mortal man’s life essence, usually through sex.[159] This led to a relatively large degree of Hong Kong horror films, even more than their Korean and Japanese counterparts, featuring chimeric creatures exhibiting bodily features of various animals.[161] According to author Stephen Teo, corporeal ‘trans-substantiation’, such as in the form of a human to werewolf or vampire to bat, is «unthinkable in Chinese culture since the rule of pragmatism requires that one’s physical, human shape be kept intact for reincarnation and for the wheel of life to keep revolving»[162]

Early Hong Hong horror films of the 1950s were often described by terms such as shenguai (gods/spirits and the strange/bizarre), qi guai (strange) and shen hua (godly story).[163] Most of these films involved a man meeting a neoi gwei (female ghost), followed by a flashback illustrating how the woman had died and usually concluded with a happy ending involving reincarnation and romance.[164] Examples include the ghost story Beauty Raised from the Dead (1956) and The Nightly Cry of the Ghost (1957) which suggests the supernatural but concludes with a rational explanation for the proceedings.[165][166] Other trends included humorous variations such as The Dunce Bumps into a Ghost (1957) as well as films about snake demons that were imitating films from the Philippines and made co-productions with the country with Sanda Wong (1955) and The Serpent’s Girls’ Worldy Fancies (1958).[167]

Director Kuei Chih-Hung in 1979, one of the few Hong Kong directors to specialize in horror films.[168]

Other Early works include The Enchanting Shadow (1960) based on Pu’s work, which did not create a cycle of ghost films.[158] In the 1970s films such as the Shaw Brothers and Hammer Film Productions co-production Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires would not take off worldwide and not produce cycles of similar horror films.[169][170] King Hu’s films such as Touch of Zen would touch upon Pu’s work, including plot points of fox spirits, while his other work such as Legend of the Mountain would be full on ghost stories.[171][172]

Veteran stuntman, actor and director Sammo Hung decided to blend horror with more humour, leading to Encounters of the Spooky Kind (1980). The film was popular at the box office leading to several kung-fu-oriented ghost comedies.[173] Directors ranging from Ann Hui to Tsui Hark would all dabble with the genre, with Sammo Hung producing Mr. Vampire and Tsui Hark producing A Chinese Ghost Story, which would be stories from Pu Songling’s work.[173][171]

According to Gary Bettinson and Daniel Martin, the critical attitude towards Hong Kong horror was that it reached its commercial and artistic peaks in the 1980s, partially in response to the audience’s decline in the dominance of kung fu films.[153] The rise of Asian horror films in the 2000s has been described by Laikwan Pang in Screen as setting Hong Kong horror films back, stating that «once famous for churning out hundreds of formulaic horror films have almost completely died out — precisely because of the industry’s fraught efforts to adapt to a Chinese market and its policy environment.»[174] In 2003, author Daniel O’Brien stated that the Hong Kong film industry still turned out horror films. Still, the number of them turned out much lower, with the genre rarely attracting major filmmakers and operating on the low-budget side of the industry with films like the Troublesome Night series, which had 18 entries.[173] In 2018, Bettinson and Martin found that the Hong Kong horror film had become nostalgic and contemporary, noting films like Rigor Mortis (2013) as referencing the older Mr. Vampire film while also as adapting to the shifting global market for Asian cinema.[160]

Exploitation and Category III

In the 1970s a shift in style and type of Hong Kong horror films began being produced, depicting more explicit depictions of sex.[175] Actor Kam Kwok-leung who appeared in some of these films such as the Shaw Brothers produced The Killer Snakes (1974) stated that the studio’s «attitude was rather shameless; they threw in nude scenes or sex scenes regardless of the genre […] As long as they could insert these scenes, they didn’t mind throwing logic out the window. The Killer Snakes was no exception»[168] The film was directed by Kuei Chih-Hung, it was his first horror film and led to him being one of the few Hong Kong directors to specialize in horror.[168] These films were sometimes described as exploitation, characterized by their gratuitous or excessive nudity, extreme violence, and gore are generally regarded by critics as «bad» rather than quality or serious cinema.[176] Keui would return to horror in various films after such as Ghost Eyes (1974), Hex (1980), Hex vs Witcraft (1980), Hex After Hex (1982) Curse of Evil (1982) and The Boxer’s Omen (1984).[177] These films were swept aside by the late 1980s when an even more raw form of exploitation cinema arose with the Category III film creation in 1988.[178] Category III films from the era such as Dr. Lamb (1992) and The Untold Story (1993) were linked to horror from their excessive violence and blood-letting of their serial killer central characters.[179]

Other horror films borrowing from Western trends were made such as Dennis Yu’s two films The Beasts (1980) resembling Last House on the Left and The Imp (1981), Patrick Tam’s Love Massacre (1981) resembling the American slasher film trend. [180] Later cases of the genre often exclude the ghost story style, such as The Untold Story (1993) and Dream Home (2010) which have lead characters within scientific explanation.[154]

India

The Cinema of India produces the largest amount of films in the world, ranging from Bollywood (Hindi cinema based in Mumbai) to other regions such as West Bengal and Tamil Nadu. Unlike Hollywood and most Western cinematic traditions, horror films produced in India incorporate romance, song-and-dance, and other elements in the «masala» format,[181] where as many genres as possible are bundled into a single film.[182] Odell and Le Blanc described the Indian horror film as «a popular, but minor part of the country’s film output» and that «has not found a true niche in mainstream Indian cinema.»[182][183] These films are made outside of Mumbai, and are generally seen as disreputable to their more respectable popular cinema.[182] As of 2007, the Central Board of Film Certification, India’s censorship board has stated films «pointless or unavoidable scenes of violence, cruelty and horror, scenes of violence intended to provide entertainment and such scene that may have the effect of desensitising or dehumanizing people are not shown.»[184]

The earliest Indian horror films were films about ghosts and reincarnation or rebirth such as Mahal (1949).[182] These early films tended to be spiritual pieces or tragic dramas opposed to having visceral content.[185] While prestige films from Hollywood productions had been shown in Indian theatres, the late 1960s had seen a parallel market for minor American and European co-productions to films like the James Bond film series and the films of Mario Bava.[186] In the 1970s and 1980s, the Ramsay Brothers created a career in the lower reaches of the Bombay film industry making low-budget horror films, primarily influenced by Hammer’s horror film productions, with little known about their production or distribution history.[187][186] The Ramsay Brothers were a family of seven brothers who made horror films that were featured monsters and evil spirits that mix in song and dance sections as well as comic interludes.[188] Most of their films played at smaller cinema in India, with Tulsi Ramsay, one of the brothers, later stating «Places where even the trains don’t stop, that’s where our business was.»[189] Their horror films are generally dominated by low-budget productions, such as those by the Ramsay Brothers. Their most successful film was Purana Mandir (1984), which was the second highest-grossing film in India that year.[188][190] The influence of American productions would have an effect on later Indian productions such as The Exorcist which would lead to films involving demonic possession such as Gehrayee (1980). India has also made films featuring zombies and vampires that drew from American horror films opposed to indigenous myths and stories.[185] Other directors, such as Mohan Bhakri made low budget highly exploitive films such as Cheekh (1985) and his biggest hit, the monster movie Khooni Mahal (1987).[188]

Horror films are not self-evident categories in Tamil and Telugu films and it was only until the late 1980s that straight horror cinema was regularly produced with films like Uruvam (1991), Sivi (2007), and Eeram (2009) were released.[191] The first decade of the twenty-first century saw a flurry of commercially successful Telugu horror films like A Film by Aravind (2005), Mantra (2007), and Arundhati (2009) were released.[191] Ram Gopal Varma made films that generally defied the conventions of popular Indian cinema, making horror films like Raat (1992) and Bhoot (2003), with the latter film not containing and comic scenes or musical numbers.[188] In 2018, the horror film Tumbbad premiered in the critics’ week section of the 75th Venice International Film Festival—the first ever Indian film to open the festival.[192]

Indonesia

Japan