From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| The Ward | |

|---|---|

Film poster |

|

| Directed by | John Carpenter |

| Written by | Michael Rasmussen Shawn Rasmussen |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Yaron Orbach |

| Edited by | Patrick McMahon |

| Music by | Mark Kilian The Newbeats |

|

Production |

|

| Distributed by |

|

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

99 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million[3] |

| Box office | $5.3 million[4] |

The Ward (titled onscreen as John Carpenter’s The Ward) is a 2010 American supernatural psychological horror film directed by John Carpenter and starring Amber Heard, Mamie Gummer, Danielle Panabaker, Laura-Leigh, Lyndsy Fonseca and Jared Harris.[5] Set in 1966, the film chronicles a young woman who is institutionalized after setting fire to a house, and who finds herself haunted by the ghost of a former inmate at the psychiatric ward.[6][7] As of 2023, this is Carpenter’s most recent film as a director.

The film was shot on location at the Eastern State Hospital in Medical Lake, Washington.[8][9]

Plot[edit]

In rural Oregon, at the Coos Bay Psychiatric Hospital in 1966, a young patient named Tammy is killed by an unseen force at night.

Kristen (Amber Heard), a troubled young woman, sets fire to an abandoned farmhouse and is arrested. The local police take her to Coos Bay, where she meets the other patients in the ward: artistic Iris (Lyndsy Fonseca), seductive Sarah (Danielle Panabaker), wild Emily (Mamie Gummer), and child-like Zoey (Laura-Leigh). Kristen is taken to a room previously occupied by their friend, Tammy, and meets therapist, Dr. Stringer (Jared Harris). She reveals that she is unable to recall anything about her past. She is attacked by a horribly deformed figure that had been staring at her earlier, but upon telling the nurse this, she is drugged and put through intense electroshock therapy.

Dr. Stringer uses hypnotherapy to unlock Iris’s hidden memories. After the session, Iris is killed by transorbital lobotomy by the deformed figure. Kristen finds Iris’ sketch of her attacker with the name ‘Alice Hudson’, a former patient at the hospital. That night, Kristen and Emily attempt to find Iris and escape. However, Kristen is thwarted by Alice, and loses consciousness while Emily is caught.

Sarah is killed by Alice. Kristen discovers that all of the girls had killed Alice together because Alice constantly hurt them. Now she is after the girls for revenge. Kristen tries to talk Emily down from attempting suicide but Alice kills her by slitting her throat with a scalpel. Kristen plans to escape again by holding Zoey as a pretend hostage but is drugged and placed in a straitjacket. She escapes it and she and Zoey try to get out. Zoey is killed by Alice off-screen. After a lengthy chase, Kristen seemingly manages to destroy Alice. She finds Alice’s file in Dr. Stringer’s office, which has each of the girls’ names, including Kristen herself.

Dr. Stringer, catching her in his office, reveals that Kristen is actually one of many personalities of the real Alice Hudson, who was kidnapped at age eleven, eight years earlier, and left chained for two months in the basement of the same farmhouse Kristen burned down. In order to survive the trauma, she developed Dissociative Identity Disorder, creating each one of the girls from the ward as a different personality. Over time, Alice’s own personality became so overwhelmed by the others that she became lost. Dr. Stringer attempted experimental techniques to bring Alice’s own personality back, resulting in the manifestation of Ghost Alice, who destroyed the individual personalities one by one. Her treatments were working until ‘Kristen’ appeared, as an attempt of Alice’s mind to protect the other personalities so she wouldn’t need to face her trauma.

At the end of the movie, Alice packs a suitcase with her belonging as she prepares to leave the hospital. When she opens the medicine cabinet above her sink, Kristen lunges out at her.

Cast[edit]

- Amber Heard as Kristen, the main protagonist. A girl with no memories of her life but the strong belief that she is not crazy. She feels the constant need to escape the ward no matter the cost. She is the first in noticing the other girls are disappearing and that a vengeful ghost might be the one behind it.[10]

- Mamie Gummer as Emily. She is tough and free-spirited but also the one who mostly acts in wild, insane manner, annoys the other patients, and calls everyone crazy, which often starts conflict among girls especially between her and Sarah. Initially, she tries to intimidate and scare Kristen, but eventually, Kristen’s strength makes her admire her. She hides a guilty feeling inside her though it seems unlikely she will open to it.

- Danielle Panabaker as Sarah, a vain, beautiful redhead and the flirtatious one of the group. She flirts with a male nurse but is turned down because she is a mental patient. She often puts down the other girls through her snobbish and snooty disposition.[11]

- Laura-Leigh as Zoey, a girl who has suffered emotional trauma so severe that she keeps acting and dressing like a little girl. She carries around a stuffed rabbit everywhere she goes. She seems oppressed by the others due to her instant trust in Kristen.

- Lyndsy Fonseca as Iris, artistically talented and prim and proper, she is the first of the girls in befriending Kristen. She is nice and kind to everyone. She also carries a sketchbook where she likes to draw. She seems to be the most aware of their situation in the ward since she explains to Kristen everything about their seclusion.[12]

- Mika Boorem as Alice, a girl who used to be a patient at the ward but is nowhere to be found anymore. Kristen tries to find out what happened to her during her time at the Ward.

- Jared Harris as Dr. Stringer, the girls’ psychiatrist. He seems hopeful in curing Kristen, though his real intentions seem mysterious the whole time.[13]

- Sydney Sweeney as Young Alice, a young girl who Kristen sees in flashbacks, both hands chained in a cellar. Nothing is really explained about her in the beginning.[14]

- Dan Anderson as Roy, the chief orderly at the ward. Serious and unpredictable, tries to maintain order inside the ward. He is the main target of Sarah’s flirting.

- Susanna Burney as Nurse Lundt, the chief nurse at the ward. Tends to consider Kristen a loose end, and constantly tries to act without the authority of Dr. Stringer.

- Sali Sayler as Tammy, a girl who disappears from the ward unexpectedly. Her disappearance upsets the other girls. Her empty room is later occupied by Kristen. She is the mastermind behind Alice’s «death» at the hands of the girls.

- Mark Chamberlin as Mr. Hudson, the sad man (as Emily describes him and his wife). They constantly visit the ward and are often seen watching the girls from a window.

- Jillian Kramer as Monster Alice, the ghost responsible for the disappearances. Using surgical tools as torture means on her victims. Not much is clear about her other than the fact that she is getting rid of the girls one by one.

Production[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2014) |

The film marks a return for Carpenter after a ten-year hiatus of not making any films; his last was the 2001 film Ghosts of Mars.[15][dead link] According to Carpenter, «I was burned out…I had fallen out of love with cinematic storytelling».[15] Despite this, in the meantime he had done two episodes for the anthology TV show Masters of Horror. Carpenter said that the series reminded him of why he fell in love with the craft in the first place.[15][dead link] Carpenter said that the script «came along at the right time for me»,[16] and he was particularly fascinated by how the film took place within a single location.[16]

The film was shot on location in Spokane, Washington, and at the Eastern State Hospital in Medical Lake, Washington.[9] The film was shot at a real operating mental hospital, and the crew was caged in to prevent patients from intervening.[16]

Release[edit]

The first footage revealed from the film was on French channel Canal+.[17] The film premiered on September 13 at the 2010 Toronto International Film Festival.[18] The Ward was released in the UK on January 21, 2011.[19] After its debut in a handful of film festivals in late 2010, The Ward was released in a few US theatres on July 8, 2011, where it grossed $7,760. The worldwide gross was $5.3 million.[4] It was released on DVD and Blu-ray Disc in the US on August 16, 2011,[20] and in the UK on October 17, 2011.[21]

Reception[edit]

The Ward received generally negative reviews.[22] Rotten Tomatoes, a review aggregator, reports that 33% of 72 surveyed critics gave the film a positive review; the average rating is 4.5/10. The site’s consensus states: «Lacking the hallmarks of his best work, The Ward proves to be a disappointingly mundane swan song for director John Carpenter.»[23] Metacritic rated it 38/100 based on 18 reviews.[24]

Dennis Harvey of Variety wrote, «As usual Carpenter uses the widescreen frame with aplomb, but pic suffers from too little character detailing (even if a late twist explains that), rote scares, and emphasis on a hectic pace over atmosphere.»[25] Michael Rechtshaffen of The Hollywood Reporter called it «an atmospheric supernatural thriller that has been stripped of the filmmaker’s later excesses».[26] Tim Grierson of Screen International wrote, «Tight as a drum and plenty of fun, John Carpenter’s first film in nine years is hardly a groundbreaker, but when the execution is this expert, why complain?»[27] Film Journal International wrote, «Genre veteran John Carpenter’s sleekly professional ghost story is well-acted and directed but sadly derivative. Horror fans have seen it all before.»[28] The Guardian’s Phelim O’Neill also considered the film to be unoriginal, but nevertheless «a well-made film, with some finely crafted shocks»[29]

Jeannette Catsoulis of The New York Times wrote that the film «continues the painful decline of a director who seems more nostalgic for past glories than excited about new ideas».[9] Robert Abele of the Los Angeles Times wrote that the film «feels like a foot-wetting exercise rather than a full-bodied romp in familiar waters».[30] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly rated it B− and wrote, «While he does bring his trademark craftsmanship to this snake-pit mental-asylum thriller, the picture has too many old-movie bits rattling around in it.»[31] Adam Nayman of Fangoria wrote, «The problem with The Ward is not so much its lack of style as the fact that the director doesn’t seem to have much interest in the material».[32] David Harley of Bloody Disgusting rated it 1/5 stars and wrote, «If someone other than Carpenter had been at the helm of The Ward, then no one would be talking about it.»[33] Serena Whitney of Dread Central rated it 3.5/5 stars and wrote, «John Carpenter’s The Ward is a mediocre thriller that lacks any true original scares and blatantly rips off a twist ending from a far better film.»[34]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c «John Carpenter’s The Ward». AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ a b Kit, Borys (February 12, 2011). «John Carpenter’s ‘The Ward’ Finds U.S. Distributor (Berlin)». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 13, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ^ Monagle, Matthew (August 15, 2017). «When Did James Cameron Become Hollywood’s Blockbuster Punch Line?». Film School Rejects. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ a b «The Ward (2010)». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ «Video Production Diary: John Carpenter’s The Ward«. DreadCentral. June 5, 2012.

- ^ «More Cast Members Added to John Carpenter’s The Ward«. DreadCentral. August 16, 2021.

- ^ «Pre-Production Video Diary for John Carpenter’s ‘The Ward’«. Bloody Disgusting. November 4, 2009.

- ^ «Spokane-filmed ‘The Ward,’ by popular ‘demand’«. The Spokesman. June 8, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c Catsoulis, Jeannette (July 7, 2011). «‘John Carpenter’s The Ward’«. The New York Times. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ «Amber Heard Shows Some Emotion in ‘The Ward’ Image». BloodyDisgusting. December 2009.

- ^ Miska, Brad (October 19, 2009). «Sales Art and First Images from John Carpenter’s ‘The Ward’«. Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ «New Promo Pic for John Carpenter’s The Ward». DreadCentral. June 19, 2012.

- ^ «Early Art and Images: John Carpenter’s The Ward». DreadCentral. May 24, 2012.

- ^ «Pre-Production Video Diary for John Carpenter’s ‘The Ward’«. BloodyDisgusting. November 4, 2009.

- ^ a b c Bibbiani, William. «Interview: John Carpenter on ‘The Ward’«. CraveOnline. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ a b c Eggertsen, Chris (June 3, 2011). «Interview with ‘The Ward’ Director John Carpenter». Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ Miska, Brad (September 15, 2009). «An Early Look at John Carpenter’s ‘The Ward’«. Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ «2010 Films – John Carpenter’s The Ward». Toronto International Film Festival. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ O’Hara, Helen (January 6, 2011). «First Trailer Online For The Ward». Empire. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Hurtado, J. (August 4, 2011). «John Carpenter’s THE WARD On Blu-ray/DVD August 16th». Twitch Film. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Jacques, Adam (October 16, 2011). «John Carpenter: ‘3D films are so exciting. Until you put those stupid glasses on’«. The Independent. Archived from the original on June 20, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Levin, Robert (July 8, 2011). «‘The Ward’ Marks John Carpenter’s Unspectacular Return to Directing». The Atlantic. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ «The Ward (2011)». Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ «The Ward». Metacritic. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ Harvey, Dennis (September 17, 2010). «Review: ‘John Carpenter’s The Ward’«. Variety. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Rechtshaffen, Michael (October 14, 2010). «The Ward: Film Review». The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Grierson, Tim (September 14, 2010). «John Carpenter’s The Ward». Screen Daily. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ «Film Review: John Carpenter’s The Ward». Film Journal International. July 7, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ O’Neill, Phelim (January 20, 2011). «John Carpenter’s The Ward – review». the Guardian.

- ^ Abele, Robert (July 8, 2011). «Movie review: ‘The Ward’«. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (January 17, 2015). «The Ward». Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Nayman, Adam (September 16, 2010). ««THE WARD» (TIFF Film Review)». Fangoria. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Harley, David (August 11, 2011). «[Blu-ray Review] ‘The Ward’«. Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Whitney, Serena (September 15, 2010). «Ward, The (2010)». Dread Central. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

Further reading[edit]

Interviews:

- Radish, Christina (June 8, 2011). «Exclusive: Director John Carpenter Talks THE WARD and His Thoughts on Hollywood Remaking His Films». Collider. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- Radish, Christina (September 11, 2010). «John Carpenter Exclusive Interview THE WARD». Collider. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- Eggertsen, Chris (June 3, 2011). «Interview with ‘The Ward’ Director John Carpenter». Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- Nemiroff, Perri (July 6, 2011). «Interview: The Ward’s Lyndsy Fonseca». Cinema Blend. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- Radish, Christina (June 7, 2011). «Amber Heard Talks THE WARD and NBC’s THE PLAYBOY CLUB». Collider. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- Zinoman, Jason (June 24, 2011). «A Lord of Fright Reclaims His Dark Domain». The New York Times. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- Bibbiani, William (July 5, 2011). «Interview: John Carpenter on ‘The Ward’«. CraveOnline. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

External links[edit]

Terrifying people through stories? It’s been a pastime of we humans since antiquity, with a large swathe of folklore centered around things that go bump in the night (particularly supernatural goings-on or anything related to—and exploiting—our innate fear of death.) With such a strong precedent in literature and oral history, it’s no surprise that the first horror movie was quick to get its feet under the table soon after the advent of cinema.

The First Horror Movie: What Was It?

Over the course of a century, film horror has gone through many peaks and troughs, leading us into the somewhat contentious period we find ourselves in today. The history of horror as a film genre begins with—as with many things in cinema history—the works of George Mellies.

Just a few years after the first filmmakers emerged in the mid-1890s, Mellies created “Le Manoir du Diable,” sometimes known in English as “The Haunted Castle” or “ The House of the Devil,” in 1898, and it is widely believed to be the first horror movie. The three-minute film is complete with cauldrons, animated skeletons, ghosts, transforming bats, and, ultimately, an incarnation of the Devil. While not intended to be scary—more wondrous, as was Mellies’ MO—it was the first example of a film (only just rediscovered in 1977) to include the supernatural and set a precedent for what was to come. Where the genre will go over the next hundred years is anyone’s guess, but sometimes it’s good to look back on the long road we’ve traveled to get to this point.

The Literary Years

After the first horror movie, sometime between 1900 and 1920, an influx of supernatural-themed films followed. Many filmmakers—most of whom still trying to find their feet with the new genre—turn to literature classics as source material. The first adaptation of Frankenstein was released by Edison Studios in these early days, as well as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and The Werewolf (now both lost to the fog of time.) Things were starting to roll at this point as we moved into…

The Golden Age of Horror

Widely considered to be the finest era of the genre, the two decades between the 1920s and 30s saw many classics being produced and can be neatly divided down the middle to create a separation between the silent classics and the talkies.

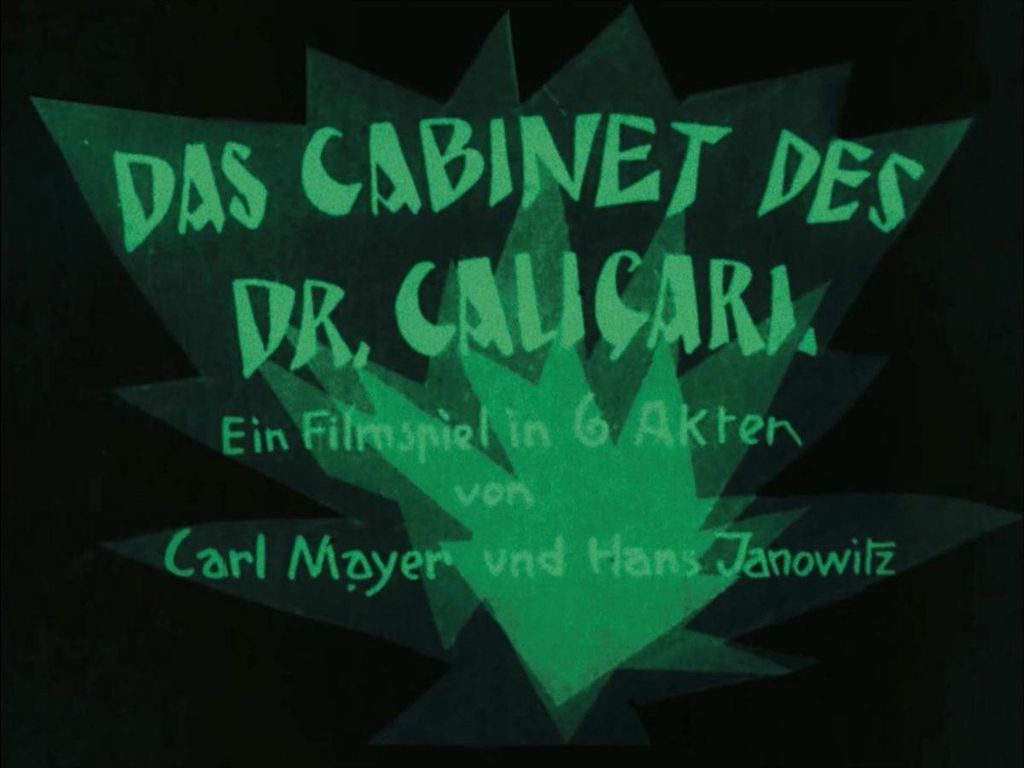

On the silent side of the line, you’ve got monumental titles such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Nosferatu (1922), the first movies to really make an attempt to unsettle their audience. The latter title is one of Rotten Tomatoes’ best horror movies of all time and cements just about every surviving vampire cliché in the book.

Once the silent era gave way to the technological process, we had a glut of incredible movies that paved the way for generations to come, particularly in the field of monster movies – think the second iteration of Frankenstein (1931), The Mummy (1932) and the first color adaptation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931).

The 30s also marked the first time that the word “horror” was used to describe the genre—previously, it was really just romance melodrama with a dark element—and it also saw the first horror “stars” being born. Bella Lugosi (of Dracula fame) was arguably the first to specialize solely in the genre.

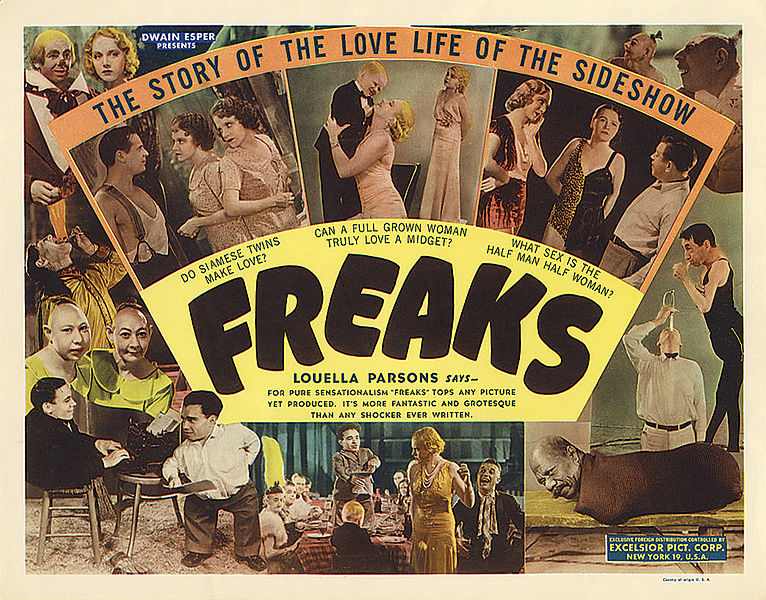

And as well as unnerving its viewers, the genre was starting to worry the general public at this point, with heavy censoring and public outcry becoming common with each release. Freaks (1932) is a good example of a movie that was so shocking at the time it got cut extensively, with the original version now nowhere to be found. Director Tod Browning—who had previously created the aforementioned and wildly successful Dracula—saw his career flounder at the hands of the controversy.

The shock value of Freaks is one of the few that has aged well up until the present day and is still a highly disturbing watch.

The Atomic Years

Freaks were banned for thirty years in the country that really came into its own during this period: Great Britain.

The Hammer horror company, while founded in 1934, only started to turn prolific during the fifties, but when it did, it was near global dominance (thanks to a lucrative distribution deal with Warner and a few other U.S. studios). Once again, it was adaptations like Frankenstein, Dracula, and The Mummy that put the company squarely on the map, followed up by a slew of psychological thrillers and TV shows.

And, of course, you can’t mention British horror without paying respects to Alfred Hitchcock, singlehandedly responsible for establishing the slasher genre, which we’ll see a lot of as we travel further forward in time.

Another hallmark of the 40s-50s era of horror came as a product of the times. With war ravaging Europe and fears of nuclear fallout running rampant, it’s of little surprise that horror began to feature antagonists that were less supernatural in nature—radioactive mutation became a common theme (The Incredible Shrinking Man, Godzilla), as did the fear of invasion with The War of the Worlds and When Worlds Collide, both big hits in 1953.

The latter marked the earliest rumblings of the “disaster” movie genre, but it would be a couple more decades before that would get into full swing.

The Gimmicky Years

3D glasses? Electric buzzers installed into theatre seats? Paid stooges in the audience screaming and pretending to faint? Everything and anything was tried during the 50s and 60s in an attempt to further scare cinema audiences. This penchant for interactivity spilled over into other genres during the period but quickly died down in part due to the massive amount of expense involved. For horror, in particular, this gave way to the opposite end of the spectrum: incredibly low-budget productions.

From the late 60s onwards, so insatiable was the American appetite for gore that slasher films produced for well under $1 million took hold and were churned out by volume. That’s not to say that there weren’t some masterpieces produced during this time, though; George A. Romero emerged triumphant and kickstarted zombie movies in this period, having produced Night of the Living Dead in 1968 with just over $100k. It went on to gross $30 million, and the living dead rose in its wake.

All Hell Breaks Loose

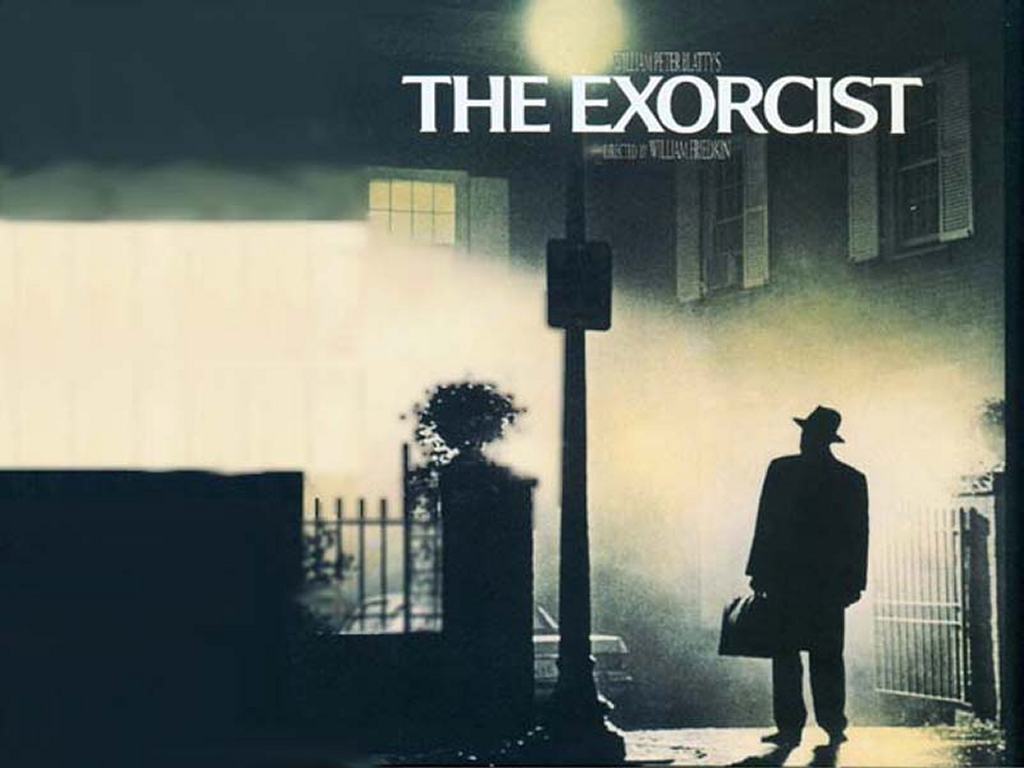

Occult was the flavor of the day between the 70s and 80s, particularly when it came to houses and kids being possessed by the Devil. The reason for this cultural obsession with religious evil during this period could fill an entire article on its own, but bringing it back into the cinema realm, we can boil the trend down to two horror milestones: The Exorcist (1973) and The Omen (1976). Supernatural horror was now very much back in vogue, and harking back to its cinematic origins, literature once again became the source material. This time, however, it wasn’t a Victorian author whose work had fallen out of copyright but a gentleman named Stephen King.

Carrie (1976) stormed the gates, and The Shining (1980) finished the siege (with 1982’s supernatural frightfest Poltergeist following soon afterward). With these hallmarks in the history of horror now firmly established, the foundations were laid for…

The First Horror Movie Slashers

If there’s one trope that typifies the 80s, it’s the slasher format – a relentless antagonist hunting down and killing a bunch of kids in ever-increasing inventive ways, one by one. Arguably kicked off by The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in 1974, the output became prolific over the next decade. For every ten generic slashers, however, there was one flick that would end up becoming a cult classic even if critical success was mixed at the time—Halloween, Friday the 13th, and A Nightmare on Elm Street are the most prominent examples, which became so successful that they spawned their own long-running franchises (the first time in the history of the genre that multiple sequels became commonplace.)

Plenty of imitators and rip-offs followed, too, particularly in the Holiday-themed department. Some were a lot better than others as the genre descended to its most kitschy. Similar to the first horror movie, these films were not intended to scare but to entertain.

The Doldrums

Suffering from exhaustion in the wake of a thousand formulaic slasher movies and their sequels, the genre lost steam as it moved into the 90s. The advent of computer-generated special effects brought with it a number of lackluster CGI monster titles that did little to revive the genre, such as Anaconda (1997) and Deep Rising (1998). But it was a comedy that ended up saving the day. Peter Jackson’s early foray into filmmaking saw him taking the splatter subgenre to ridiculous extremes with Braindead (1992), and Wes Craven’s slasher parody Scream (1996) was met globally with overwhelming success.

The genre as a whole limped on without much fanfare into the 2000s save for a few box office successes. The zombie subgenre, however, sprang back into un-life during this decade, arguably spurred on by the unprecedented success of Max Brook’s novel World War Z (later becoming a film in its own right.) The video game adaptation of Resident Evil (2002) was among the first of the new wave, followed swiftly by 28 Days Later a few months later, Dawn of the Dead (2004), Land of the Dead (2005), I Am Legend (2007) and Zombieland (2009.)

The Present Day

The state of the horror industry is hotly contested. With the genre seemingly relying on churning out remakes, reboots, and endless sequels, many argue that it’s languishing in the doldrums once again with little originality to offer a modern audience. The resurgence of ‘torture porn’ is also derided as a subgenre, having come back into the fore in the wake of the 2000s Saw and Hostel franchises with no signs of slowing down.

On the other hand, glimmers of hope shine through with examples of extreme originality and artistry. Cabin in the Woods (2012) has been heralded as this decade’s Scream, and the recent releases of The Babadook and A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (both 2014) breathed new life into the genre. Jordan Peele, writer, producer, and actor, rose as the new king of horror with original films, including Get Out (2017), Us (2019), and Nope (2022), which top Rotten Tomatoes’ best horror movie list. While scary, the films are also smart and provide sociopolitical commentary, as Peele explained in an interview with Time Magazine. NYFA Alum Tracy Oliver is a co-writer of the 2022 film The Blackening, a movie that makes fun of horror clichés but also calls out racial stereotypes. Both films, similar to the first horror film and a variety of others in the history of horror, don’t have the main goal of scaring the audience.

The Future of Horror Films

With perhaps more subgenres than any other branch of fictional filmmaking, it’s difficult to see how anyone can expand or advance on anything that has come before in cinematic horror. However, there’s no doubt somebody will, and that motivated and imaginative film school students become the Alfred Hitchcocks of tomorrow.

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions. - Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

A horror film may make your hair stand on end, but, in an unusually perfect example of etymological symmetry, the idea of hair standing on end is literally the origin of the word horror.

Once you pass all those rules, you’re granted access to the McKamey Manor which the website says it «is an audience participation event in which (YOU) will live your own Horror Movie.»

Each tour is different and is based on the attendee’s personal fears and could last up to 10 hours. The waiver process alone is three to four hours, according to the website.

— Natalie Dreier, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 23 Oct. 2019

‘Horror’ comes from a Latin verb meaning «to bristle» or «to shudder»—the idea being that a horrified person’s hair stands on end.

Origin of Horror

Horror came into English through the French spoken in Britain in the 13th and 14th centuries, and ultimately comes from Latin. Like valor, color, honor, and humor, it’s spelled the same way in English as it is in Latin (these words were re-Latinized in modern American English from a variety of French and Middle English spellings). Horror derives from the verb horrēre, which had several meanings:

to stand up, to bristle

to have a rough, unkempt appearance

to shudder, to shiver (with cold)

to tremble (with fear)

The “bristle” sense became the basis for the original meaning of the Latin noun horror: “the action or quality (in hair) of rising or standing stiffly, bristling” (according to the Oxford Latin Dictionary). Bristling from cold or fear—shuddering or shivering—led to the development of the meaning “a quality or condition inspiring horror” or “a thing which brings terror.” The symptom became the cause.

The “shuddering” or “shivering” senses of horror were in use into the 20th century. In the 1934 Webster’s Second Unabridged, a medical sense of horror was defined as:

A shaking, shivering, or shuddering, as in the cold fit which precedes a fever; in old medical writings, a chill of less severity than a rigor, and more marked than an algor.

And the 1961 edition, Webster’s Third Unabridged, added a specific sense for the plural form horrors as a synonym of delirium tremens: “a violent delirium with tremors.”

The physical appearance of hair standing on end led to the other intermediate meaning between “bristling” and “bringing terror”: “roughness of appearance.” This became an early meaning of horror in English, a meaning shared with another descendant of horrēre, horrid, which originally meant “rough” or “bristling,” meanings that are now archaic. It was used with this meaning in Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy, from 1621:

And therefore Seneca adviseth his friend Lucilius, “in his attire and gesture, outward actions, especially to avoid all such things as are more notable in themselves: as a rugged attire, hirsute head, horrid beard, contempt of money, coarse lodging, and whatsoever leads to fame that opposite way.”

Words Derived From Horror

Both horrendous and horrific, like horrid, came into English in the 16th and 17th centuries, by which time horror had come to principally mean “a very strong feeling of fear, dread, or shock” and mostly drifted away from any hairy, bristly, or shivering notions. Perhaps to fill this lexical gap, another related word was borrowed from Latin at this time: hirsūtus, meaning “hairy” and “bristly,” and became hirsute in English. The fact that horrēre meant “to bristle” and hirsūtus meant “covered with bristles” is most likely not a coincidence, since they probably come from the same Indo-European root, a verb meaning “to be stiff, to bristle,” though no written record goes back that far.

All of which is to say that, the next time you tremble with fear, there’s an etymological reason that you’re in a hairy situation.

Why are humans drawn to the horror genre? From books to film, we can’t seem to get enough of what scares us most. In this article, we will look at the definition of horror and why we enjoy the genre so much. We will also look at a brief history of American cinema and how horror has evolved over the years. While this article will provide a general definition of horror, the genre is open to interpretation. After all, what is horror to you, is Child’s Play to me.

Watch: What Makes a Great Jump Scare?

Subscribe for more filmmaking videos like this.

Define Horror

The Horror genre explained

Horror is one of the most popular genres in storytelling. What began in literature can now be found in movies, television, theatre, and video games. The horror genre has been divided into many sub-genres with their own definitions and criteria. Before we get to those, let’s define horror at a basic level:

HORROR DEFINITION

What is Horror?

Horror is a genre of storytelling intended to scare, shock, and thrill its audience. Horror can be interpreted in many different ways, but there is often a central villain, monster, or threat that is often a reflection of the fears being experienced by society at the time. This person or creature is called the “other,” a term that refers to someone that is feared because they are different or misunderstood. This is also why the horror genre has changed so much over the years. As culture and fears change, so does horror.

What are some defining elements of the horror genre?

- Themes: The horror genre is often a reflection of the culture and what it fears at the time (invasion, disease, nuclear testing, etc.).

- Character Types: Besides the killer, monster, or threat, the various sub-genres contain certain hero archetypes (e.g., the Final Girl in Slasher movies).

- Setting: Horror can have many settings, such as: a gothic castle, small town, outer space, or haunted house. It can take place in the past, present or future.

- Music: This is an important facet in the horror genre. It can be used with great effect to build atmosphere and suspense.

Horror Subgenres

Different types of horror movies

The horror genre has given birth to many sub-genres and hybrids of these various types. Each has its own unique themes, but all of them share one common goal: FEAR.

Found Footage

The point-of-view takes place from the perspective of a camera. Famous titles include The Blair Witch Project and Rec.

Lovecraftian

Focuses on cosmic horror. Monsters are beings beyond our comprehension. Often incorporates science fiction, including horror classics like Alien and The Thing.

Psychological

This sub-genre focuses on the horror of the mind. What is real? What is madness? Two great psychological horror movies are Silence of the Lambs and Jacob’s Ladder.

Science Fiction

Focuses on the horror and consequences of technology. Monsters are often aliens or machines. Two great sci-fi horror movies are The Blob and War of the Worlds.

Slasher

The monster is a psychopath with a penchant for bloody murder. Often focuses on the punishment of promiscuous teenagers. Popular movies include Halloween and A Nightmare on Elm Street.

Supernatural

Focuses on the afterlife. Primary creatures include ghosts and demons. Great titles include Poltergeist and The Exorcist.

Torture

Similar to slasher; focuses on the punishment of people. The villain takes pleasure in the physical and psychological torment of victims. Famous movies include Hostel and Saw.

A History of Horror Movies 1896-2018

Horror vs Thriller

The relationship of Horror and Thriller

While the two genres are often confused, there is a clear difference between horror and thriller movies. Horror movie rules demand violence and a monster that appears early and relatively frequently. The climax revolves around a final fight or an escape from the monster. The «monster» in horror is typically «unnatural» or even «supernatural,» whereas thrillers tend to rely on human threats.

In a thriller, there is much more mystery and discovery. Tensions rise as the protagonist gets closer to discovering the evil threat. The climax revolves around a big reveal, such as the true intentions of the villain.

The two genres con blend, of course, such as the modern horror/thriller Get Out (2017). Something like Halloween might also be considered a crossover since the killer is human but he exhibits supernatural abilities — like how he never seems to die when he’s «killed.»

Now that we’ve covered our horror film definition, let’s take a look back at a history of horror movies. Through the decades, the horror movie has evolved to reflect what we we fear the most, as explained in this video.

The Horror Genre and Cultural Fears

1930’s Horror

Horror and The Depression

The 1930s was a tough period for America. We were in the midst of the Great Depression and Americans were feeling more desperate than ever before. Despite the economic turmoil, people spent what little they had on entertainment, like movies. One of the first great American horror films that garnered much popularity was Dracula (1931), based on the novel by Bram Stoker. And it set the standard for the Best Vampire Movies thereafter.

But why was Dracula so terrifying? Americans were afraid of European influence. World War I ended only 13 years prior. The American mindset was still heavily influenced by the atrocities that took place. Combined with the influx of European immigrants, people were afraid of outsiders corrupting American culture. Someone had to be the scapegoat.

Another film that was a reflection of the fears of the time was Frankenstein (1931), based on the novel by Mary Shelly. This movie created a more sympathetic monster; one that was fleeing from the oppression of his creator.

Below is the original disclaimer that ran before the movie began. It is a warning played up for dramatic effect («…it might even horrify you!»).

Frankenstein Disclaimer

Americans felt as though they that their government had failed them. They blamed their leaders for their misfortune, much like how Dr. Frankenstein failed to protect his creation.

A recurring theme in horror is that the monster is often mankind itself. The villagers lashed out against something they didn’t understand, becoming monsters themselves.

What is Horror? Dracula (1931)

1950s Horror

Horror in the ’50s

World War II ended in 1945, but it left a huge mark on the world, both literally and figuratively. The use of nuclear weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki gave way to a new era of fear in the nuclear age. The consequences of mankind’s use of science and technology would become a common theme.

Often not thought of as horror, Godzilla (1954) is a Japanese film that came to America. It was a response to the bombs used by the U.S. In this story, an animal is transformed by nuclear radiation into a giant monster and terrorizes the country. With the advent of the nuclear age, many questions and fears were brought up with this powerful but dangerous energy source.

The monster movie has a rich tradition within the horror genre, dating back to the very first movies. Do yourself a favor and watch this documentary on the history of the monster movie.

History of the Horror Genre • Monster Movies

The 50’s also gave to the Red Scare and the fear of communism. The theme of invasion became prevalent in many monster movies. Science fiction would blend with the horror genre, giving birth to films such as War of the Worlds (1953) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956).

In the first film, aliens begin an invasion of earth in a small town, indicative of a communist attack. In the second film, humans are replaced with alien duplicates, which represents the fear of communism overtaking democracy.

What is Horror? War of the Worlds (1953)

1960s-’70s Horror

When the monster became human

The 1960s-’70s was a period of uncertainty and violence for America. We were in the midst of the Vietnam War, a conflict that caused much controversy. For the first time, the U.S. was no longer in the right for a global conflict. The violence committed by men led to the fear of what we as a species were capable of.

Night of the Living Dead (1968) came as a result of this fear and uncertainty. The monsters, which looked very human, would mercilessly attack, kill and devour people. What made the zombies most terrifying was that they could take on the appearance of our loved ones. If we cannot trust our fellow human, who can we trust?

Thanks to a copyright error, Night of the Living Dead belongs in the public domain. That means you can watch it for free right now. Any self-respecting horror genre fan has to watch this movie.

Watch Night of the Living Dead in its entirety

The 70’s were also known for the increase in news coverage on serial killer murders. Media outlets reported on these maniacs as if they were celebrities. People were afraid of the monster next door coming by and killing them in their homes.

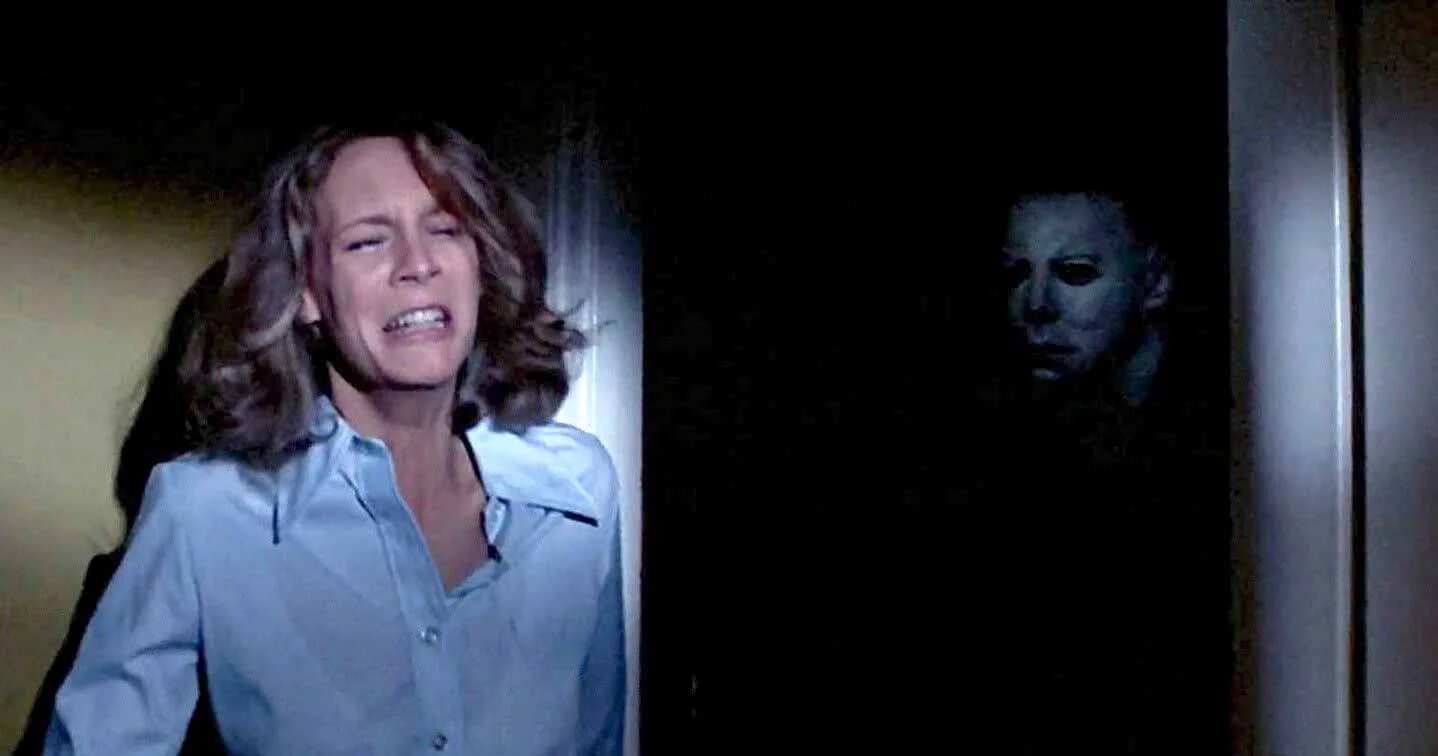

This gave rise to the first “slasher,” Halloween (1978). Despite appearing human, Michael Myers was an unstoppable killer that stalked his victims with murderous intent. Slashers grew immensely in popularity, even affecting movies that are not slashers.

The slasher sub-genre would also explore the subject of morality. The sexually promiscuous would be punished and violently murdered, while the moral “Final Girl” would survive to the bitter end.

One would think that these human monsters would drive people away from horror. But the blood-soaked films would make the genre more popular than ever.

What is Horror? Halloween (1976)

1980s-’90s Horror

What is Self-Aware Horror?

Coming out of the serial killer era in the ’70s, the ’80s would continue the trend of slashers with a massive influx of these movies. Friday the 13th, A Nightmare on Elm Street and even Halloween would spawn numerous sequels, each one more absurd than the last.

Hitting a breaking point, the horror genre became more «aware» of itself in the form of Scream (1996). Though very much still a slasher, this film acknowledged the well-worn tropes established by its predecessors, such as the Final Girl.

What is Horror? Scream (1996)

Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) would take the trope of the weak high school girl and turn her into a monster killer. While the protagonist, Buffy, was killing vampires and other monsters, she and her friends would still experience the woes of being a teenager.

The ’90s would also pave the way for a new sub-genre: found footage. The Blair Witch Project (1999) gave the audience the point-of-view of a camera, putting them in the shoes of the victims. This made the horror more personal for viewers, revitalizing the genre as a whole.

Horror Sub-genres • Found Footage

2000s Horror

When the horror film took a dark turn

After 9/11, the war on terror would spawn a generation of films that would redefine what horror is: torture. The prospect of psychos capturing and torturing their victims, both physically and psychologically proved to be a box office success.

Perhaps the most notorious of these is Saw (2004). In this film, a sociopath captures several people and forces them to play his sadistic games if they want to survive. This gruesome concept would spawn a plethora of sequels and copycats, flooding the market and coining a new term for the excess of violence: torture porn.

Global fears and international terror attacks made the end of the world seem more plausible. People became more fascinated than ever over the prospect of a catastrophe like a zombie apocalypse.

As such, the horror genre would reflect this with shows such as The Walking Dead (2010-present). How would any of us survive? How can something so overwhelming ever be stopped? As zombie movies grew in popularity, so did the number of movies. And as this video explains, what we now call «zombies» began as something quite different.

Horror Sub-genres • Zombies

The Future of Horror

What is horror today?

To say we live in a new world would be an understatement. The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we act, think and feel. Global culture as a whole has changed and it will continue to do so for some time. As such, expect the horror genre to reflect this evolution of fear. Don’t be surprised when an influx of movies revolving around isolation and global pandemics hits theaters.

There has been a sort of renaissance of horror movies in the last decade that has been quite excited to watch. Films like The Witch, It Follows and Hereditary have been dubbed «elevated horror» — a divisive term to say the least. Whatever we call them, they are all still really strong and effective horror movies. Here’s a breakdown of Midsommar and how the shape of the horror genre continues to evolve.

How Ari Aster Uses the Background • Subscribe on YouTube

UP NEXT

The Best Horror Movies of All Time

We just covered a very broad horror genre definition and there is a lot more to explore. We’ve been talking a lot about the horror genre but now it’s time to face our fears and actually watch some. Through the last century, across genre to sub-genre, from ghouls to goblins, here are the Best Horror Movies of All Time.