Practicing reading skills is one of the cornerstones of language learning. They not only improve the overall language competence but also enhance the learners’ critical thinking, analytical skills and as a source of information.

In order to have a productive reading session the teacher must conduct the lesson following these stages:

- pre-reading — to prepare the learners for the reading activity, to set a context, familiarize them with the unknown vocabulary, arouse interest.

- while-reading — this is the main task the reading session is aimed at comprehension questions (True/False statements, skimming and scanning, etc.).

- post-reading — its aim is to understand the texts further through critical analysis of what they have read or to provide personalization.

This article aims at giving some practical guidance to teachers who are eager to have productive reading sessions.

Pre-reading activities

One of the most important stages of any reading activity is the appropriate setting of the context, familiarization with the active vocabulary, getting to know how much the learners know about the topic. For this purpose, the following activities may be used,

- Crumpled papers: The teacher prints out the text which is going to be read and crumples it. He/she divides the class into groups and gives each group one crumpled version of the text. Students are not allowed to move the paper but they can move themselves trying to read some words, phrases, sentences. They take notes of whatever they are able to read and in a group discussion try to guess the main idea of the text.

- Corner Statements: The teacher prepares 4 sentences expressing opinions about the topic, then sticks them in 4 corners of the classroom. Students go and stand near the opinion they disagree with the most. The group explains why they disagree about the topic.

- Guessing from words or pictures: The teacher boards the keywords from a reading, students work in pairs or groups and try to guess the text. In the same way, the pairs or groups may be given some topic-related pictures and they need to give the main idea of the text.

- Sound effects: The teacher plays on some sound effect related to the reading and students are asked to guess the topic by giving the associations which came to them while listening to those sounds.

- Positive or Negative words: The teacher divides the class into two groups and gives two sets of different words taken out from the text. One group is given words with a positive connotation, the second group needs to deal with negative connotation words. They need to guess the story having in mind those words. As a result, the class comes up with two totally different versions of the same text.

- KWL Charts: Ask students to write everything they know about the topic (K column) and everything they want to know (W column) and what they learned after the reading (L Column). K and W aspects can be practiced as pre-reading activities.

While-reading activities

They help students to focus on aspects of the text and to understand it better. The goal of these activities is to help learners to deal with the text as if it was written in their mother tongue.

- Topic Sentences: Each paragraph stands for one main idea. Students are asked to find the topic sentence and explain how it describes the whole reading passage and the given paragraph.

- Guessings: Read the text (skimming the text for general information) to see if the guessings and predictions are met.

- Scanning: Students look for specific information from the text. Learners may be also asked to write comprehension questions for their peers.

Post-reading activities

These activities mainly aim at integrating the target material into the real-life and personalized practice in order to keep the authentic use of the language, make the learners feel that whatever they learn they turn into real-life experience in terms of language use.

- Discussions: Learners are divided into groups and are given a set of text-related questions to discuss. Questions may be about some characters, their behaviour, how the text has interested the students, what they have learned from it, etc.

- Story Continuation: Students may be given some time to think and come up with the continuation of the story. They may change some traits of the main characters and imagine how the text would proceed to take into account those changes.

- Statements: Students are given statements about the reading topic, they work in pairs and discuss them.

Considering the utmost importance of reading skill in language learning, all the above-mentioned activities can serve as nice tools to hone the learners’ reading skills.

You can look at some more interesting ideas and useful resources here.

It is hard enough planning for whole group reading block and small group centers/stations. We now also incorporate guided reading groups to differentiate and meet the needs of students in our class at their level. It is hard to plan for these groups and get them in daily while monitoring students at their centers. Your school/district may have certain requirements that you must follow when conducting reading groups, but here are five simple steps to hopefully make your groups run smoothly.

1. Warm-Up (2 minutes)

I like to start with a quick warm-up, usually phonemic awareness in nature. Whether it be segmenting words into syllables or sounds, identifying beginning, middle, or ending sounds, or producing rhyming words. A good set of picture cards is super useful for these activities.

For older students, your warm-up may be a “quick read” of a passage or short text. Just a short something to get their minds geared into reading.

2. Word Work (3 minutes)

After the warm-up, I move onto word work or the phonics skill that particular group is working on. It could be short vowels, r-controlled vowels, blends, or dipthongs, etc. I create lines of practice on sentence strips (pictured below) to help my students work on decoding words with that phonics skill. If the group has 4 students in it, I will make 5 lines. I always make one more line than students in the group. We “pass the lines” in a clockwise manner, until each student has read every line.

If your guided reading group leveled readers are written with a particular phonics skill in the text, make sure to include those words on your lines of practice, along with other words. This way your students will have an easier time decoding those story words when you get to the fluency part of the lesson.

3. Vocabulary (3 minutes)

Vocabulary can mean a couple of things. For most of our younger learners, these will be sight words. For our older learners, it may be actual higher level vocabulary from their leveled reader.

I try to make the vocabulary portion of the reading group a game of some kind…

- We play KABOOM, where the words are written on popsicle sticks and we take turns pulling and reading a stick. If the student pulls out KABOOM, they have to put all of their sticks back.

- Another game is Flip It. Their words are written on note cards and laid face down on the table. Students choose a card and flip it over, trying to read the word as quickly as they can. You can change this one up and deal the cards to kids around the table. They flip through them and read quickly. The goal is to read all of their words with no mistakes.

- For higher level vocabulary, each student gets a word and has to give a definition in their own words while their group mates try to guess the word.

- Have each student in the group create a “All About ___” poster. This includes the vocabulary word, its definition, syllables, synonyms or antonyms if applicable, an illustration, and using the word properly in the sentence. (I use this as a check for understanding at the end of the week.)

4. Fluency (7 minutes)

Most of us are using a district adopted reading curriculum that includes leveled readers to be used in guided reading groups. Your students reading level will determine the book they are reading. There are a variety of ways you can have students read their leveled reader…

- Read Around the Table – each student has a part to read and you read aloud in a clockwise direction (to alleviate anxiety, I assign students their parts first, allow them to practice for a minute, and then we read around the table)

- Echo/Whisper Reading – one student reads aloud while the others whisper/echo their words

- I Do/You Do – one student reads aloud, then all students reread aloud what was just read

- Leaning/Listening In – all students are quietly reading at their own pace as you “lean/listen in” around the table to each one for a few seconds at a time (my personal favorite)

My goal is to have their book completed by the end of the second time we meet, so they read the book at least twice in group with me. Then this book will be a part of their small group centers the following week, to practice and strengthen their fluency.

5. Comprehension (3 minutes)

Comprehension should be a quick check for understanding on what they have currently read in their leveled reader. Try to come up with higher level questions and not just basic “yes/no” responses. At the end of the week, I hand each student a note card with one question on it. You can either hold a discussion on the questions, or have students write their response on the note card. I use this as my “ticket out” from reading group for the week.

In addition, you can include comprehension questions with your leveled readers the following week in small group centers.

Try our leveled Reading Comprehension Passages and Question Packs!

Phonics-Based Fluency Passages

Sight Word Fluency Passages

Practically 1st Grade Passages

1st Grade Reading Comprehension Passages

2nd Grade Reading Comprehension Passages

3rd Grade Reading Comprehension Passages

Keep in Mind…

(On a 5 day week/2 hour ELA Block)

- Low (5 days a week)

- Low/Average (5 days a week)

- Average (4 days a week)

- Average/High (3 days a week)

- High (3 days a week)

Two important pieces to note…

- Do not pull your lower students at the same time each day. We want them to have access to all of the small group centers and not missing the same ones every day while in group with you.

- Guided reading groups should be flexible in nature. As you are progress monitoring and giving formal/informal assessments, students should be able to move up or down depending on their instructional needs.

Written by: Janessa Fletcher

At Education to the Core, we exist to help our teachers build a stronger classroom as they connect with our community to find trusted, state-of-the-art resources designed by teachers for teachers. We aspire to be the world’s leading & most trusted community for educational resources for teachers. We improve the lives of every teacher and learner with the most comprehensive, reliable, and inclusive educational resources.

If you enjoyed what we have to offer at ETTC, be sure to join our email list, so you won’t miss a beat. We are here to help with all your resource needs. Become a Premium Member of Education to the Core and receive immediate access to thousands of printable activities. For one small monthly or annual fee, everything ETTC can be at your fingertips all of the time.

Comments

comments

Guided reading is an instructional practice or approach where teachers support a small group of students to read a text independently.

Key elements of guided reading

- before reading discussion

- independent reading

- after reading discussion

The main goal of guided reading is to help students use reading strategies whilst reading for meaning independently.

Why use guided reading

Guided reading is informed by Vygotsky’s (1978) Zone of Proximal Development and Bruner’s (1986) notion of scaffolding, informed by Vygotsky’s research. The practice of guided reading is based on the belief that the optimal learning for a reader occurs when they are assisted by an educator, or expert ‘other’, to read and understand a text with clear but limited guidance. Guided reading allows students to practise and consolidate effective reading strategies.

Vygotsky was particularly interested in the ways children were challenged and extended in their learning by adults. He argued that the most successful learning occurs when children are guided by adults towards learning things that they could not attempt on their own.

Vygotsky coined the phrase ‘Zone of Proximal Development’ to refer to the zone where teachers and students work as children move towards independence. This zone changes as teachers and students move past their present level of development towards new learning. (Source: Literacy Professional Learning Resource, Department of Education and Training, Victoria)

Guided reading helps students develop greater control over the reading process through the development of reading strategies which assist decoding and construct meaning. The teacher guides or ‘scaffolds’ their students as they read, talk and think their way through a text (Department of Education, 1997).

This guidance or ‘scaffolding’ has been described by Christie (2005) as a metaphor taken from the building industry. It refers to the way scaffolds sustain and support people who are constructing a building.

The scaffolds are withdrawn once the building has taken shape and is able to support itself independently (pp. 42-43). Similarly, the teacher places temporary supports around a text such as:

- frontloading new or technical vocabulary

- highlighting the language structures or features of a text

- focusing on a decoding strategy that will be useful when reading

- teaching fluency and/or

- promoting the different levels of comprehension – literal, inferential, evaluative.

Once the strategies have been practised and are internalised, the teacher withdraws the support (or scaffold) and the reader can experience reading success independently (Bruner, 1986, p.76).

When readers have the opportunity to talk, think and read their way through a text, they build up a self-extending system.

This system can then fuel itself; every time reading occurs, more learning about reading ensues. (Department of Education, Victoria, 1997; Fountas and Pinnell, 1996). Guided reading is a practice which promotes opportunities for the development of a self-extending system (Fountas and Pinnell, 1996).

Teacher’s role in guided reading

Teachers select texts to match the needs of the group so that the students, with specific guidance, are supported to read sections or whole texts independently.

Students are organised into groups based on similar reading ability and/or similar learning needs determined through analysis of assessment tools such as running records, reading conference notes and anecdotal records.

Every student has a copy of the same text at an instructional level (one that can usually be read with 90–94% accuracy, see

Running Records). All students work individually, reading quietly or silently.

Selecting texts for EAL/D learners

Understanding EAL/D students’ strengths and learning needs in the Reading and viewing mode will help with appropriate text selection. Teachers consider a range of factors in selecting texts for EAL/D students including:

- content which connects to prior knowledge and experiences, including culturally familiar contexts, characters or settings

- content which introduces engaging and useful new knowledge, such as contemporary Australian settings and themes

- content which prepares students for future learning, e.g. reading a narrative about a penguin prior to a science topic about animal adaptations

- language at an accessible but challenging level (‘just right’ texts)

- availability of support resources such as audio versions or translations of the text

- texts with a distinctive beat, rhyming words or a combination of direct and indirect speech to assist with pronunciation and prosody

- the difficulty of the sentence structures or grammatical features in the selected text. Ideally, students read texts at an instructional level (texts where students achieve 90 per cent accuracy if they read independently) in order to comprehend it readily. This is not always feasible, particularly at the higher levels of primary school. If the text is difficult, the teacher could modify the text or focus the reading on a section before exposing them to the whole text.

For more information on texts at an instructional level, see:

Running records

Students also need repeated exposure to new text structures and grammatical features to extend their language learning, such as texts with:

- different layouts and organisational features

- different sentence lengths

- simple, compound or complex sentences

- a wide range of verb tenses used

- a range of complex word groups (noun groups, verb groups, adjectival groups)

- direct and indirect speech

- passive voice, e.g. Wheat is harvested in early autumn, before being transported to silos.

- nominalisation, e.g. The presentation of awards will take place at 8pm.

EAL/D students learn about the grammatical features as they arise in authentic texts. For example, learning about the form and function of passive sentences when reading an exposition text, and subsequently writing their own passive sentences.

All students in the class including EAL/D students will typically identify a learning goal for reading. Like all students, the learning needs of each EAL/D student will be different. Some goals may be related to the student’s prior experience with literacy practices, such as:

- ways to incorporate reading into daily life at home

- developing stamina to read for longer periods of time

- developing fluency to enable students to read longer texts with less effort.

Some goals may be related to the nature of students’ home language(s):

- learning to perceive, read and pronounce particular sounds that are not part of the home language, for example, in Korean there is no /f/ sound

- learning the direction of reading or the form of letters

- learning to recognise different word forms such as verb tense or plural if they are not part of the home language.

For more information on appropriate texts for EAL/D students, see:

Languages and Multicultural Education Resource Centre

Major focuses for a teacher to consider in a guided reading lesson:

Before reading the teacher can

- activate prior knowledge of the topic

- encourage student predictions

- set the scene by briefly summarising the plot

- demonstrate the kind of questions readers ask about a text

- identify the pivotal pages in the text that contain the meaning and ‘walk’ through the students through them

- introduce any new vocabulary or literary language relevant to the text

- locate something missing in the text and match to letters and sounds

- clarify meaning

- bring to attention relevant text layout, punctuation, chapter headings, illustrations, index or glossary

- clearly articulate the learning intention (i.e. what reading strategy students will focus on to help them read the text)

- discuss the success criteria (e.g. you will know you have learnt to ….. by ………).

During reading the teacher can

- ‘listen in’ to individual students

- observe the reader’s behaviours for evidence of strategy use

- assist a student to monitor meaning using phonic, semantic, contectual and grammatical knowledge

- confirm a student’s problem-solving attempts and successes

- give timely and specific feedback to help students achieve the lesson focus

- make notes about the strategies individual students are using to inform future planning and student goal setting. See

Teacher’s role during reading).

After reading the teacher can

- talk about the text with the students

- invite personal responses such as asking students to make connections to themselves, other texts or world knowledge

- return to the text to clarify or identify a decoding teaching opportunity such as the revision of phoneme-grapheme correspondence blending or segmenting

- check a student understands what they have read by asking them to sequence, retell or summarise the text

- develop an understanding of an author’s intent and awareness of conflicting interpretations of text

- ask questions about the text or encourage students to ask questions of each other

- develop insights into characters, settings and themes

- focus on aspects of text organisation such as characteristics of a non-fiction text

- revisit the learning focus and encourage students to reflect on whether they achieved the success criteria.

Source: Department of Education, 1997

The teacher selects a text for a guided reading group by matching it to the learning needs of the small group. The learning focus is identified through the analysis of running records (text accuracy, cueing systems and identified reading behaviours), individual conference notes or anecdotal records, see

Running Records).

Additional focuses for a teacher to consider for EAL/D students in a guided reading lesson

Before reading a fictional text, the teacher can

- orientate students to the text. Discuss the title, illustrations, and blurb, or look at the titles of the chapters if reading a chaptered book

- activate students’ prior knowledge about language related to the text. This could involve asking students to label images or translate vocabulary. Students could do this independently, with same-language peers, family members or Multicultural Education Aides, if available

- use relevant artefacts or pictures to elicit language and knowledge from the students and encourage prediction and connections with similar texts.

Before reading a factual text, the teacher can

- support students to brainstorm and categorise words and phrases related to the topic

- provide a structured overview of the features of a selected text, for example, the main heading, sub headings, captions or diagrams

- support students to skim and scan to get an overview of the text or a specific piece of information

- support students to identify the text type, its purpose and language structures and features.

During reading the teacher can

- talk to EAL/D students about strategies they use when reading in their home language and encourage them to use them in reading English texts. Teachers can note these down and encourage other students to try them.

After reading the teacher can

- encourage EAL/D students to use their home language with a peer (if available) to discuss a response to a teacher prompt and then ask the students to share their ideas in English

- record student contributions as pictures (e.g. a story map) or in English so that all students can understand

- create practise tasks focusing on particular sentence structures from the text

- set review tasks in both English and home language. Home language tasks based on personal reflection can help students develop depth to their responses. English language tasks may emphasise learning how to use language from the text or the language of response

- ask students to practise reading the text aloud to a peer to practise fluency

- ask students to create a bilingual version of the text to share with their family or younger students in the school

- ask students to innovate on the text by changing the setting to a place in their home country and altering some or all of the necessary elements.

Inferring meaning

In this video, the teacher uses the practice of guided reading to support a small group of students to read independently. Part 1 consists of the before reading discussion which prepares the small group for the reading, and secondly, students individually read the text with teacher support.

In this video (Part 2), the teacher leads an after reading discussion with a small group of students to check their comprehension of the text. The students re-read the text together. Prior to this session the children have had the opportunity to read the text independently and work with the teacher individually at their point of need.

Point of view

In this video, the teacher leads a guided reading lesson on point of view, with a group of Level 3 students.

Text selection

The teacher selects a text for a guided reading group by matching it to the learning needs of the small group. The learning focus is identified through:

- analysis of running records (text accuracy, cueing systems and identified reading behaviours)

- individual conference notes

- or anecdotal records.

Text selection

The text chosen for the small group instruction will depend on the teaching purpose. For example, if the purpose is to:

- demonstrate directionality — the teacher will ensure that the text has a return sweep

- predict using the title and illustrations — the text chosen must support this

- make inferences — a text where students can use their background knowledge of a topic in conjunction with identifiable text clues to support inference making.

Text selection should include a range of:

- genres

- texts of varying length and

- texts that span different topics.

It is important that the teacher reads the text before the guided reading session to identify the gist of the text, key vocabulary and text organisation. A learning focus for the guided reading session must be determined before the session. It is recommended that teachers prepare and document their thinking in their weekly planning so that the teaching can be made explicit for their students as illustrated in the examples in the information below.

Example 1

Students

Jessie, Rose, Van, Mohamed, Rachel, Candan

Text/Level

Tadpoles and Frogs, Author Jenny Feely, Program AlphaKids published by Eleanor

Curtain Publishing Pty Ltd. ©EC Licensing Pty Ltd. (Level 5)

Learning Intention

We are learning to read with phrasing and fluency.

Success criteria

I can use the grouped words on each line of text to help me read with phrasing.

Why phrase

Phrasing helps the reader to understand the text through the grouping of words into meaningful chunks.

An example of guided reading planning and thinking recorded in a teacher’s weekly program (See

Guided Reading Lesson: Reading with phrasing and fluency).

Example 2

Students

Mustafa, Dylan, Rosita, Lillian, Cedra

Text/Level

The Merry Go Round – PM Red, Beverley Randell, Illustrations Elspeth Lacey ©1993. Reproduced with the permission of Cengage Learning Australia. (Level 3)

Learning intention

We are learning to answer inferential questions.

Success criteria

I can use text clues and background information to help me answer an inferential question.

Questions as prompts

Why has the author used bold writing? (Text clue) Can you look at Nick’s body language on page11? Page 16? What do you notice? (Text clues) Why does Nick choose to ride up on the horse rather than the car or plane? (Background information on siblings, family dynamics and stereotypes about gender choices).

An example of the scaffolding required to assist early readers to answer an inferential question. This planning is recorded in the teacher’s weekly program (See Guided Reading Lesson: Literal and Inferential Comprehension).

More examples

- an example of guided reading planning and thinking recorded in a teacher’s weekly program, see Guided Reading Lesson: Reading with phrasing and fluency)

- questions to check for meaning or critical thinking should also be prepared in advance to ensure the teaching is targeted and appropriate

- an example of the scaffolding required to assist early readers to answer an inferential question. This planning is recorded in the teacher’s weekly program.

It’s important to choose a range of text types so that students’ reading experiences are not restricted.

Quality literature

Quality literature is highly motivating to both students and teachers. Students prefer to learn with these texts and given the opportunity will choose these texts over traditional ‘readers’ (McCarthey, Hoffman & Galda, 1999, p.51).

Research

Research suggests the quality and range of books to which students are exposed to such as:

- electronic texts

- levelled books

- student/teacher published work.

Students should be exposed to the full range of genres we want them to comprehend. (Duke, Pearson, Strachan & Billman, 2011, p. 59).

Considerations

When selecting texts for teaching purposes include: levels of text difficulty and text characteristics such as:

- the length

- the degree of detail and complexity and familiarity of the concepts

- the support provided by the illustrations

- the complexity of the sentence structure and vocabulary

- the size and placement of the text

- students’ reading behaviours

- students’ interests and experiences including home literacies and sociocultural practices

- texts that promote engagement and enjoyment.

For ideas about selecting literature for EAL/D learners, see:

Literature

Teacher’s role during reading

During the reading stage, it is helpful for the teacher to keep anecdotal records on what strategies their students are using independently or with some assistance. Comments are usually linked to the learning focus but can also include an insightful moment or learning gap.

Learning example

Students

Jessie

- finger tracking text

- uses some expression

- not pausing at punctuation

- some phrasing but still some word by word.

Rose

- finger tracking text

- reading sounds smooth.

Van

- reads with expression

- re-reads for fluency.

Mohamed

- uses pictures to help decoding

- word by word reading

- better after some modelling of phrasing.

Rachel

- tracks text with her eyes

- groups words based on text layout

- pauses at full stops.

Candan

- recognises commas and pauses briefly when reading clauses

- reads with expression.

Explicit teaching and responses

There are a number of points during the guided reading session where the teacher has an opportunity to provide feedback to students, individually or as a small group. To execute this successfully, teachers must be aware of the prompts and feedback they give.

Specific and focused feedback will ensure that students are receiving targeted strategies about what they need for future reading successes, see

Guided Reading: Text Selection;

Guided Reading: Teacher’s Role.

Examples of specific feedback

- I really liked the way you grouped those words together to make your reading sound phrased. Did it help you understand what you read? (Meaning and visual cues)

- Can you go back and reread this sentence? I want you to look carefully at the whole word here (the beginning, middle and end). What do you notice? (Visual cues)

- As this is a long word, can you break it up into syllables to try and work it out? Show me where you would make the breaks. (Visual cues)

- It is important to pause at punctuation to help you understand the text. Can you go back and reread this page? This time I want you to concentrate on pausing at the full stops and commas. (Visual and meaning cues)

- Look at the word closely. I can see it starts with a digraph you know. What sound does it make? Does that help you work out the word? (Visual cues)

- This page is written in past tense. What morpheme would you expect to see on the end of verbs? Can you check? (Visual and structural cues)

- When you read something that does not make sense, you should go back and reread. What word could go there that makes sense? Can you check to see if it matches the word on the page? (Meaning and visual cues)

Providing feedback to EAL/D learners

Specific feedback for EAL/D students may involve and build on transferable skills and knowledge they gained from reading in another language.

- I can see you were thinking carefully about the meaning of that word. What information from the book did you use to help you guess the meaning?

- Do you know this word in your home language? Let’s look it up in the bilingual dictionary to see what it is.

Reading independently

Independent reading promotes active problem solving and higher-order cognitive processes (Krashen, 2004). It is these processes which equip each student to read increasingly more complex texts over time; “resulting in better reading comprehension, writing style, vocabulary, spelling and grammatical development” (Krashen, 2004, p. 17).

It is important to note that guided reading is not round robin reading. When students are reading during the independent reading stage, all children must have a copy of the text and individually read the whole text or a meaningful segment of a text (e.g. a chapter).

Students also have an important role in guided reading as the teacher supports them to practise and further explore important reading strategies.

Before reading the student can

- engage in a conversation about the new text

- make predictions based on title, front cover, illustrations, text layout

- activate their prior knowledge (what do they already know about the topic? what vocabulary would they expect to see?)

- ask questions

- locate new vocabulary/literary language in text

- articulate new vocabulary and match to letters/sounds

- articulate learning intention and discuss success criteria.

During reading the student can

- read the whole text or section of text to themselves

- use concepts of print to assist their reading

- use pictures and/or diagrams to assist with developing meaning

- problem solve using the sources of information — the use of meaning, (does it make sense?) structure (can we say it that way?) and visual information (sounds, letters, words) on extended text (Department of Education, 1997)

- recognise high frequency words

- recognise and use new vocabulary introduced in the before reading discussion segment

- use text user skills to help read different types of text

- read aloud with fluency when the teacher ‘listens in’

- read the text more than once to establish meaning or fluency

- read the text a second or third time with a partner.

After reading the student can

- be prepared to talk about the text

- discuss the problem solving strategies they used to monitor their reading

- revisit the text to further problem solve as guided by the teacher

- compare text outcomes to earlier predictions

- ask and answer questions about the text from the teacher and group members

- summarise or synthesise information

- discuss the author’s purpose

- think critically about a text

- make connections between the text and self, text to text and text to world.

Additional focuses for EAL/D students when reading independently

Before reading the student can:

- activate their home language knowledge. What home language words related to this topic do they know?

During reading the student can:

- refer to vocabulary charts or glossaries in the classroom to help them recognise and recall the meaning of words learnt before reading the text

- use home language resources to help them understand words in the text. For example, translated word charts, bilingual dictionaries, same-language peers or family members.

After reading the student can:

- summarise the text using a range of meaning-making systems including English, home language and images.

Peer observation of guided reading practice (for teachers)

Providing opportunities for teachers to learn about teaching practices, sharing of evidence-based methods and finding out what is working and for whom, all contribute to developing a culture that will make a difference to student outcomes (Hattie, 2009, pp. 241-242).

When there has been dedicated and strategic work by a Principal and the leadership team to set learning goals and targeted focuses, teachers have clear direction about what to expect and how to go about successfully implementing core teaching and learning practices.

One way to monitor the growth of teacher capacity and whether new learning has become embedded is by setting up peer observations with colleagues. It is a valuable tool to contribute to informed, whole-school approaches to teaching and learning.

The focus of the peer observation must be determined before the practice takes place. This ensures all participants in the process are clear about the intention. Peer observations will only be successful if they are viewed as a collegiate activity based on trust.

According to Bryk and Schneider, high levels of “trust reduce the sense of vulnerability that teachers experience as they take on new and uncertain tasks associated with reform” and help ensure the feedback after an observation is valued (as cited in Hattie, 2009, p. 241).

To improve the practice of guided reading, peer observations can be arranged across Year levels or within a Year level depending on the focus. A framework for the observations is useful so that both parties know what it is that will be observed. It is important that the observer note down what they see and hear the teacher and the students say and do. Evidence must be tangible and not related to opinion, bias or interpretation (Danielson, 2012).

Examples of evidence relating to the guided reading practice might be:

- the words the teacher says (Today’s learning intention is to focus on making sure our reading makes sense. If it doesn’t, we need to reread and problem solve the tricky word)

- the words the students say (My reading goal is to break up a word into smaller parts when I don’t know it to help me decode)

- the actions of the teacher (Taking anecdotal notes as they listen to individual students read)

- what they can see the students doing (The group members all have their own copy of the text and read individually).

Noting specific examples of engagement and practice and using a reflective tool allows reviewers to provide feedback that is targeted to the evidence rather than the personality. Finding time for face-to-face feedback is a vital stage in peer observation. Danielson argues that “the conversations following an observation are the best opportunity to engage teachers in thinking through how they can strengthen their practice” (2012, p.36).

It’s through collaborative reflection and evaluation that teaching and learning goals and the embedding of new practice takes place (Principles of Learning and Teaching [PoLT]: Action Research Model).

In practice examples

For in practice examples, see:

Guided reading lessons

References

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Christie, F. (2005). Language Education in the Primary Years. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press/University of Washington Press.

Danielson, C. (2012). Observing Classroom Practice, Educational Leadership, 70(3), 32-37.

Department of Education, Victoria (1997). Teaching Readers in the Early Years. South Melbourne: Addison Wesley Longman Australia.

Department of Education, Employment and Training, Victoria (1999). Professional Development for Teachers in Years 3 and 4: Reading. South Melbourne: Addison Wesley Longman Australia.

Dewitz, P. & Dewitz, P. (February 2003), They can read the words, but they can’t understand: Refining comprehension assessment. In The Reading Teacher, 56 (5), 422-435.

Duke, N.K., Pearson, P.D., Strachan, S.L., & Billman, A.K. (2011). Essential Elements of Fostering and Teaching Reading Comprehension. In S. J. Samuels & A. E. Farstrup (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (4th ed.) (pp. 51-59). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Fisher, D., Frey, N. and Hattie, J. (2016). Visible learning for Literacy: Implementing Practices That Work Best to Accelerate Student Learning. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Hall, K. (2013). Effective Literacy Teaching in the Early Years of School: A Review of Evidence. In K. Hall, U. Goswami, C. Harrison, S. Ellis, and J. Soler (Eds), Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Learning to Read: Culture, Cognition and Pedagogy (pp. 523-540). London: Routledge.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Publishers

Hill, P. & Crevola, C. (Unpublished)

Krashen, S.D. (2004). The Power of Reading: Insights from the Research (2nd Ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

McCarthey,S.J., Hoffman, J.V., & Galda, L. (1999) ‘Readers in elementary classrooms: learning goals and instructional principles that can inform practice’ (Chapter 3) . In Guthrie, J.T. and Alvermann, D.E. (Eds.), Engaged reading: processes, practices and policy implications (pp.46-80). New York: Teachers College Press.

Principles of Learning and Teaching (PoLT): Action Research Model Accessed

Scaffolding: Lev Vygotsky (June, 2017)

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Fun Pre-Reading and Post-Reading Activities for All Language Classrooms

Fun Pre-Reading and Post-Reading Activities for All Language Classrooms

I love language lessons which involve an element of reading. This is because there are so many opportunities for learning and improving language acquisition with topic-related texts. Reading activities are the perfect starting point to learn rich topic-related vocabulary (adjectives, nouns, verbs etc), pick up new grammar structures, steal ‘star phrases’ and ultimately improve comprehension and improve language acquisition skills.

According to Moeller & Meyer (1995), reading, even at a slow pace exposes students to more sentences, grammar, and new vocabulary per minute than the average short class, TV show, or song. So, if you are in a rut with how you present and teach your reading activities, get an innovative injection of pre-reading activities and post-reading activities below.

Who Should Use These Awesome Reading Activities?

All of these reading ideas for the language classroom are low-prep and no-prep reading activities. Use them in any post-beginner language classroom, including French, German, English and Spanish lessons.

The aim of these 21 must-use reading activities is to get your language students focused and in the mood for learning. However, as the teacher, you will need to be in charge of providing a great text, to bring the reading ideas below to life. This could range from one paragraph for beginners, to a few chunky paragraphs for intermediate learners, to an extended text for advanced students.

- “Find The Word” Reading Aloud Activity (Pair Work)

Put students in pairs and provide them with one copy of a text. Have a secret list of words at the ready and call them out, at random, one at a time. Allow time for students to scan the text for the word they hear. The first person in the pair to point correctly at the word in the text gets a point. Make sure you set sound level rules, as well as clear guidance on how the class should be silent ready for the next round. - “Reading Aloud” Task (Pair Work / Small Group Work)

Provide students with a ‘chunky’ text split into paragraphs. Advise that each student in the pair/group must read one paragraph aloud. If the person has an issue pronouncing a word, he/she must circle it and if they come across a word they don’t understand, they must underline it. Allow students to discuss their problem areas in pairs and then in fours. Go around making a note of the common issues and write on the board with whole group choral work and discussion at the end. - “Team Reading Aloud” – Pronunciation Reading (Whole Group)

Split the classroom in two and assign all students in each team a number and repeat (using the same numbers) with the other team. Provide students with a ‘chunky’ text for reading and set each team off with 20 points. The aim of the activity is to be the team to finish with the most points after the text has been read. Flip a coin to see which team begins. Randomly choose a number and that student must begin reading. If the other team spots a pronunciation error, as the student is reading, a member of the team must put their hand up. If all others in the team agree, everyone’s hand must go up – this should keep everyone focused. If they spot a genuine pronunciation error, they can help the reader make the correction receive a point (provide support if their ‘help’ isn’t quite accurate). However, if the whole team has made a mistake and picked a word that was correctly pronounced, they will lose a point and the other team will gain a point. Each time an error in pronunciation is correctly spotted, swap the reading team. Deduct points for talking or misbehaviour. - “The Last Word” Reading Activity (Pair / Small Group Work)

As a group, the team chooses how many words each student should read. For example, 3 words. In addition, allow students to choose the order of reading. Once the students begin reading, the winner is the student who follows the rules and manages to be the person to read the last word. - “Avoid The Line” – Reading Aloud Activity (Pair / Small Groups) When you prepare a text, underline words at random. Students start with 5 points. Each student must read 5 words at a time, but must avoid actually saying any words that have been underlined. Should they read the underlined word by accident, they lose a point. Students with with the most points at the end of the reading activity win.

- “Bratwurst” Name” – Reading Out Aloud Activity (Small Groups) One student begins and after a pre-determined number of words or sentences, they shout “Bratwurst / Pain au chocolat / Churros” (etc, depending on the language you teach) plus the name of someone in the group i.e. Bratwurst Laura. This person must then continue where the other reader left off. Award points at the beginning and if someone loses focus and doesn’t know where the previous reader was, they lose a point.

- Teacher Names – Reading Activity Out Aloud (Whole Group)

Split the class in two and assign 5 points to each team. Then, model pronunciation of the text by reading it out aloud. At random intervals, instead of reading the next word, call out a student’s name and that student must read the word that their name was replaced by. If the chosen student doesn’t respond without being prompted within 5 seconds of stopping, the team loses a point. Perfect for getting students to focus on reading activities, as well as getting them to pronounce the words you think they might find tricky or could do with knowing. In addition, you could get students to create a list of vocabulary replaced by students names and translate/make sentences with, as a post-reading activity. - “Wie bitte?” – Reading Aloud Activity (Small Groups)

Put students into threes, taking it in turns to read a sentence. As they read, a student must make a mistake, on purpose. This could include: wrong words, incorrect genders, wrong pronunciation, incorrect verb ending etc. When a listener hears a mistake, they must say ‘Wie bitte?’ ‘oh la la’ or ‘Oye’, depending on the language you teach. If they can correct the mistake, they win a point and if they can’t correct the error, the reader gets a point. This can also be done as a whole group with students standing up when you make a mistake. The last one to stand up is ‘out’. However, make sure you give students who are out a little task to do until the end of the game. - Spontaneous Reading Activity (Whole Group)

One student starts reading at random and can read a maximum of one sentence. As soon as they end their sentence, another student must begin reading. If no-one starts within a second, or more than one person starts reading, the whole group must go back to the beginning. Starting with another student reading the first sentence. You can vary this by getting learners to translate the text as they read the sentence or change the person (thus the verbs and possessive adjectives etc). Keep going back to the beginning until the reading out aloud activity has been completed as per the rules. - Find …. – Skim Reading Activity (Alone)

As soon as you give students a reading text, provide them with a list of words in L1 (native language) to find in L2 (language being learnt) in the text. This could be all masculine nouns, all verbs, all adjectives, all words beginning with ‘a’. They could either highlight the words in the text or underline the words. - Find the Synonym – Skim Reading Activity (Individual)

As with reading activity 10, give students a reading text and provide them with a list of words in L2. They must find and note down the synonyms they find in the text. - Be A Presenter – Reading Aloud (Pairs)

Have iPads or laptops available, enough for one between two. Have students paste a copy of your text into cue prompter with one student sitting with their back to the laptop and the other person reading aloud. The presenter must read clearly with accurate pronunciation and the listener must fill in the gaps on their sheet as they are listening with the words they hear. They may not ask the presenter to spell any word. Instead, if they have gaps at the end, the presenter must re-read (the whole lot or just the sentence, depending on how you’re feeling on the day). - Guess The Rule Reading Aloud (Whole Group Game)

The teacher begins by reading every other word from the text in order. Students must put their hands up to guess the rule. Allow individual students in the group to do the same by reading aloud. The rest of the group must try to guess the rule. Students can only start to put their hands up after the reader has read at least 1/3 or 1/2 of the text. Let the students be creative with their rules. The teacher could also re-read and do the same with adjectives, nouns, verbs etc to make the reading activity more grammar based. It’s perfect to get reluctant and shy students reading. - Running Dictation Speaking Reading Activity (Small Groups)

This works better with shorter texts or splitting a whole text into paragraphs, which each team is responsible for. Put enough copies of the texts up outside the classroom with a number on each. Assign each team a number. Advise the aim is for students to be the first team to communicate the text from their corresponding paragraph outside the classroom, without cheating. Students must take it in turns to read a sentence in sequence from their paragraph, and be the first team to finish communicating and writing the paragraph down on a sheet of paper.

RULES: a) only one student can be out of their seat at a time, b) students must not run or shout, c) students must also take it in turns to write the sentences on the paper, d) learners are not allowed to spell any words, but they are allowed to go back as many times as they need to to re-read the sentence, e) the rest of the group must work as a team to ensure the words are spelled accurately and the grammar is also correct. - Gap-Fill Transcript Dictation Reading Activity (Individual)

Provide students with a copy of the text, with gaps. I suggest three forms, one with verbs missing, the second with nouns missing and the third with adjectives missing. Distribute the sheets so they have people around them who had the same sheet. The students must individually fill in the words as they listen. You could read again if necessary. Once finished, get learners to check they have spelled the words correctly by discussing (not showing!) with their neighbours. - Wrong Words Reading Activity (Individual)

The teacher provides students with a copy of the text with a selection of incorrect words. As they listen to the text being read, they must highlight the word they hear that is incorrect. Go through a second time, and this time, the students must write in the correct words. This will give the students an idea of the text before they do any comprehension activities. - Key Word Bingo – Vocabulary Based Reading Activity (Individual)

From the text, read 5-20 words (dependent on text length) at random in L2. Students must cross them off as they hear them.

Post-Reading Activities

- True or False? – Post-Reading Activity (Alone)

Once students have read the text through properly, allow them 5 minutes to create a list of true or false statements. These can be given to a peer to answer if time allows. - Summarise The Text – Post Reading Activity (Individual)

Once students have read the text, advise that they must underline the key messages, depending on the size of the text. I recommend advising a maximum number. Students must then combine and re-word these ideas to summarise the whole text in a set number of words. - Re-write The Text – Reading Activity (Alone)

After reading (and depending on the length of the whole text), students must re-write the text in the first, second or third person singular. If the text is long, then advise that they should pick out a certain number of paragraphs. - Walking Text – Reading Comprehension Activity (Individual)

Instead of getting students to read the texts in their seats, print out a few copies. Ensure the text is enlarged and in paragraphs with line numbers. Then, chop them up with numbers, indicating the paragraph number on each and stick them around the room. I recommend doing a few copies to ensure that no more than 2 students are at one paragraph of text at a time. Give them some pre-printed comprehension questions to answer as they go around. You can support learners who need it with an indication of the paragraph number, correlating to the question, written on their sheet.

Want these ideas in a handy downloadable format? Download my 21 must-use reading activities for all language classrooms PDF here:

Did you enjoy this reading activities for the language classroom post? If so, be sure to check out these posts to improve language acquisition here too:

Fun Games for the MFL Classroom

Spontaneous Speaking with Video Clips in the Language Classroom

Want to keep up-to-date with the latest content? Sign Up to the Ideal Teacher’s Exclusive Mailing List.

JOIN ME ON MY SOCIALS FOR MORE FAB TEACHING CONTENT >>

Дети часто воспринимают чтение как скучное и неинтересное занятие. Однако его можно сделать интересным, если правильно организовать его, максимально задействовать в чтении учеников. Как организовать чтение на уроке английского языка, чтобы оно стало любимым уроком и временем отдыха. Что же такое чтение?

What is reading?

Reading is… Richard Day’s definition:

Reading is a number of interactive processes involving the reader and the text. The readers use their knowledge of the world, the topic, the language, to interact with the text to create, construct or build meaning.

How do we learn to read?

- We learn to read by reading. There is no other way.

- The more we read, the better readers we become.

- The more the teacher talks, the less the students read.

Reading strategies

Skimming is when we glance over a text to get the main idea, or “gist”.

Scanning is when we quickly look through a text to pick out key points .

Intensive reading is when we closely examine text for literary or linguistic purposes.

Extensive reading is reading “normally” for pleasure when we arе immersed in a book!

Виды чтения

- просмотровое (skimming)

- поисковое (scanning)

- изучающее (intensive)

- ознакомительное (extensive)

Extensive reading is what the students do at home when you’ve whetted their appetites with activities in the classroom and they can’t wait to see what happens next.! It’s also something they start doing when they realise that reading in a foreign language can be as pleasurable as in their own language-if you don’t try and understand every word.

Extensive reading is what the students do at home when you’ve whetted their appetites with activities in the classroom and they can’t wait to see what happens next.! It’s also something they start doing when they realise that reading in a foreign language can be as pleasurable as in their own language-if you don’t try and understand every word.

In extensive reading…

- most time is spent reading

- not answering questions

- not writing reports

- not translating

Sometimes, unfortunately, students may do these – but not as the primary focus

Comparing IR and ER

Intensive Reading

- 100% understanding

- Limited reading

- Difficult texts

- Word-for-word reading

- Use dictionaries

Extensive Reading

- Overall understanding

- Reading a lot

- Easy texts

- Fluent reading

- Ignore unknown words

Вернемся от теории к практике. На уроках учащиеся сталкиваются со множеством трудностей при чтении и обсуждении прочитанного. А именно:

- «психологический дискомфорт» — боязнь говорить на иностранном языке, сделать ошибку;

- не понимают речевую задачу;

- не хватает языковых и речевых средств;

- не вовлекаются в коллективное обсуждение;

- не выдерживают в необходимом количестве продолжительность общения;

Учитель может столкнуться с проблемой нехватки времени на уроке для полноценной работы с текстом. В своей практике, ввиду всех выделенных трудностей, эффективной оказалась организация внеклассной работы «Reading Circles», где учащиеся открывают для себя тот факт, что можно провести отлично время не только за чтением, но и за оживленным обсуждением текста, произведения в кругу друзей за чашечкой английского чая.

What are Reading Circles?

- Small groups of students who meet in the classroom to talk about stories

- Each student plays a role in the discussion

What are Reading Circles?

- Usually six Roles: Discussion Leader, Summarizer, Connector, Word Master, Passage Person, Cultur.

In a Reading Circle, each student plays a different role in the discussion

- Discussion Leader — leads the discussion.

- Summarizer— summarizes the characters and the plot.

- Connector — finds connections between the story and the real world.

- Word Master — looks for important words and phrases.

- Passage Person — looks for important passages in the story.

- Culture Collector— looks for cultural points for discussion.

The Discussion Leader’s job is to…

- Read the story twice, and prepare at least five general questions about it.

- Ask one or two questions to start the Reading Circle discussion.

- Make sure that everyone has a chance to speak and joins in the discussion.

- Call on each member to present their prepared role information

- Guide the discussion and keep it going

The Summarizer’s job is to…

- Read the story and make notes about the characters, events, and ideas.

- Find the key points that everyone must know to understand and remember the story.

- Retell the story in a short summary (one or two minutes) in your own words.

- Talk about your summary to the group, using your writing to help you.

The Connector’s job is to…

- Read the story twice, and look for connections between the story and the world outside

- Make notes about at least two possible connections to your own experiences, or to experiences of friends and family, or to real-life events.

- Tell the group about the connections and ask for their comments or questions

The Word Master’s job is to…

- Read the story, and look for words or short phrases that are new or difficult to understand, or that are important in the story

- Choose five words that you think are important for this story

- Explain the meanings of these words in simple English

- Tell the group why these words are important for understanding this story

The Passage Person’s job is to…

- Read the story, and find important, interesting, or difficult passages.

- Make notes about at least three passages that are important for the plot, or that have very interesting or powerful language.

- Read each passage to the group, or ask another group member to read it.

- Ask the group one or two questions about each passage

The Culture Collector’s job is to…

- Read the story, and look for both differences and similarities between your own culture and the culture found in the story.

- Make notes about two or three passages that show these cultural points

- Read each passage to the group

- Ask the group some questions about these, and any other cultural points in the story

The Reading Circle

Discussion Leader → Summarizer → Connector → Word Master → Passage Person → Culture Collector

Таким образом, у каждого учащего четко выделенная своя роль на уроке. Определенная символика на бэйджах показывает кто есть кто в дискуссии. В кабинете всегда висит график дискуссионного занятия и учащиеся, распределенные по ролям. Это позволяет заранее охватить тот оббьем материала, который был запланирован.

What one brings to the text is often more important

han what a text brings to us

Работа очень интересна не только старшеклассникам, но детям младшего школьного возраста. На занятии раздаются специальные таблицы, куда заносятся сведения из общего хода дискуссии — это отличная тренировка навыков разговорной речи.

Об авторе: Некрасова Елизавета Юрьевна, преподаватель английского языка МБОУ СОШ№ 37 г. Шахты, Ростовская область, Россия.

Спасибо за Вашу оценку. Если хотите, чтобы Ваше имя

стало известно автору, войдите на сайт как пользователь

и нажмите Спасибо еще раз. Ваше имя появится на этой стрнице.

Порядок вывода комментариев:

Отзывы

Егорова Елена

Отзыв о товаре ША PRO Анализ техники чтения по классам

и четвертям

Хочу выразить большую благодарность от лица педагогов начальных классов гимназии

«Пущино» программистам, создавшим эту замечательную программу! То, что раньше мы

делали «врукопашную», теперь можно оформить в таблицу и получить анализ по каждому

ученику и отчёт по классу. Великолепно, восторг! Преимущества мы оценили сразу. С

начала нового учебного года будем активно пользоваться. Поэтому никаких пожеланий у

нас пока нет, одни благодарности. Очень простая и понятная инструкция, что

немаловажно! Благодарю Вас и Ваших коллег за этот важный труд. Очень приятно, когда

коллеги понимают, как можно «упростить» работу учителя.

Наговицина Ольга Витальевна

учитель химии и биологии, СОШ с. Чапаевка, Новоорский район, Оренбургская область

Отзыв о товаре ША Шаблон Excel Анализатор результатов ОГЭ

по ХИМИИ

Спасибо, аналитическая справка замечательная получается, ОГЭ химия и биология.

Очень облегчило аналитическую работу, выявляются узкие места в подготовке к

экзамену. Нагрузка у меня, как и у всех учителей большая. Ваш шаблон экономит

время, своим коллегам я Ваш шаблон показала, они так же его приобрели. Спасибо.

Чазова Александра

Отзыв о товаре ША Шаблон Excel Анализатор результатов ОГЭ по

МАТЕМАТИКЕ

Очень хороший шаблон, удобен в использовании, анализ пробного тестирования

занял считанные минуты. Возникли проблемы с распечаткой отчёта, но надо ещё раз

разобраться. Большое спасибо за качественный анализатор.

Лосеева Татьяна Борисовна

учитель начальных классов, МБОУ СОШ №1, г. Красновишерск, Пермский край

Отзыв о товаре Изготовление сертификата или свидетельства конкурса

Большое спасибо за оперативное изготовление сертификатов! Все очень красиво.

Мой ученик доволен, свой сертификат он вложил в портфолио.

Обязательно продолжим с Вами сотрудничество!

Язенина Ольга Анатольевна

учитель начальных классов, ОГБОУ «Центр образования для детей с особыми образовательными потребностями г. Смоленска»

Отзыв о товаре Вебинар Как создать интересный урок:

инструменты и приемы

Я посмотрела вебинар! Осталась очень довольна полученной

информацией. Всё очень чётко, без «воды». Всё, что сказано, показано, очень

пригодится в практике любого педагога. И я тоже обязательно воспользуюсь

полезными материалами вебинара. Спасибо большое лектору за то, что она

поделилась своим опытом!

Арапханова Ашат

ША Табель посещаемости + Сводная для ДОУ ОКУД

Хотела бы поблагодарить Вас за такую помощь. Разобралась сразу же, всё очень

аккуратно и оперативно. Нет ни одного недостатка. Я не пожалела, что доверилась и

приобрела у вас этот табель. Благодаря Вам сэкономила время, сейчас же

составляю табель для работников. Удачи и успехов Вам в дальнейшем!

Дамбаа Айсуу

Отзыв о товаре ША Шаблон Excel Анализатор результатов ЕГЭ по

РУССКОМУ ЯЗЫКУ

Спасибо огромное, очень много экономит времени, т.к. анализ уже готовый, и

особенно радует, что есть варианты с сочинением, без сочинения, только анализ

сочинения! Превосходно!

The word-group theory in Modern English

word-group

theory in Modern English

Content

Introduction

.

Definition and general characteristics of the

word-group

.

Classification of word-groups

.

Semantic features of word-groups

.

Motivated and non-motivated word-groups

.

Phraseological word-groups

Introduction

is a branch of linguistics — the

science of language. Lexicology as a branch of linguistics has its own aims and

methods of scientific research. Its basic task — being a study and systematic

description of vocabulary in respect to its origin, development and its current

use. Lexicology is concerned with words, variable word-groups, phraseological

units and morphemes which make up words.the object of the linguistic research

within the frameworks of the lexicological analysis, word-groups draw much

attention of different scientists at different stages of the research

history.linguists as Shveitser, Arnold, Nikitin, Akhmanova, Marchenko, and many

others devoted their research papers to the matter of the word-groups, their

classification, semantic features, and other specific characteristics. They

have contributed linguistic research with a number of works, connected with

this lexical units. The matter of the word-group thorough study is topical with

a glance at their specific features, some phraseological peculiarities and

semantic-grammatical structure.above-mentioned aspects have predetermined our

choice of the topic of the present report «The word-group theory in Modern

English».object of the investigation are word-groups of Modern

English.subject of the present report includes specific features and

characteristics of word-groups.purpose of the report writing is to investigate

word-groups functioning in the Modern English language.purporse of the report

has predetermined the following tasks of the investigation:

to define the notion of the

word-group and outline its general characteristics;

to suggest the classification of the

word-group;

to consider semantic features of

word-groups;

to characterize motivated and

non-motivated word-groups;

to specify peculiar features of

phraseological word-groups.practical value of the present report is performed

by the possibility of using its materials for the further thorough study of

this matter.

1. Definition and general

characteristics of the word-group

word group is the simplest

nonpredicative (as contrasted to the sentence) unit of speech. The word group

is formed on a syntactic pattern and based on a subordinating grammatical

relationship between two or more content words. This relationship may be one of

agreement, government, or subordination. The grammatically predominant word is

the main element of the word group, and the grammatically subordinated word the

dependent element.word group denotes a fragment of extralinguistic reality. The

word group combines formally syntactic and semantically syntactic features.

Such features reveal the compatibility of grammatical and lexical meanings with

the structure of the object-logical relations that these meanings

reflect.groups may be free or phraseological. Free word groups are formed in

accordance with regular and productive combinative principles; their meanings

may be deduced from those of the component words.are a lot of definitions

concerning the word-group. The most adequate one seems to be the following: the

word-group is a combination of at least two notional words which do not

constitute the sentence but are syntactically connected. According to some

other scholars (the majority of Western scholars and professors B.Ilyish and

V.Burlakova — in Russia), a combination of a notional word with a function word

(on the table) may be treated as a word-group as well. The problem is

disputable as the role of function words is to show some abstract relations and

they are devoid of nominative power. On the other hand, such combinations are

syntactically bound and they should belong somewhere.characteristics of the

word-group are:

) As a naming unit it differs from a

compound word because the number of constituents in a word-group corresponds to

the number of different denotates: a black bird — чорний птах (2), a blackbird

— дрізд (1);loud speaker (2), a loudspeaker (1).

) Each component of the word-group

can undergo grammatical changes without destroying the identity of the whole

unit: to see a house — to see houses.

) A word-group is a dependent

syntactic unit, it is not a communicative unit and has no intonation of its own

[4; p. 28].

groups can be classified on the

basis of several principles:

a)

According to the type of syntagmatic

relations: coordinate (you and me), subordinate (to see a house, a nice dress),

predicative (him coming, for him to come),

b)

According to the structure: simple

(all elements are obligatory), expanded (to read and translate the text —

expanded elements are equal in rank), extended (a word takes a dependent

element and this dependent element becomes the head for another word: a beautiful

flower — a very beautiful flower).

1) Subordinate

word-groups.word-groups are based on the relations of dependence between the

constituents. This presupposes the existence of a governingwhich is called the

head and the dependent element which is called the adjunct (in noun-phrases) or

the complement (in verb-phrases).to the nature of their heads, subordinate

word-groups fall into noun-phrases (NP) — a cup of tea, verb-phrases (VP) — to

run fast, to see a house, adjective phrases (AP) — good for you, adverbial

phrases (DP) — so quickly, pronoun phrases (IP) — something strange, nothing to

do.formation of the subordinate word-group depends on the valency of its

constituents. Valency is a potential ability of words to combine. Actual

realization of valency in speech is called combinability [6; p. 162-163].

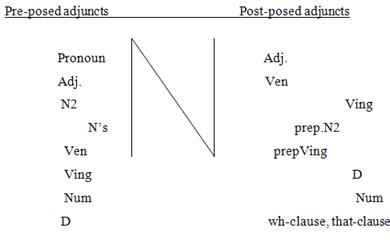

) The noun-phrase (NP).word-groups

are widely spread in English. This may be explained by a potential ability of

the noun to go into combinations with practically all parts of speech. The NP

consists of a noun-head and an adjunct or adjuncts with relations of

modification between them. Three types of modification are distinguished here:

a)

Premodification that comprises all

the units placed before the head: two smart hard-working students. Adjuncts used

in pre-head position are called pre-posed adjuncts.

b)

Postmodification that comprises all

the units all the units placed after the head: students from Boston. Adjuncts

used in post-head position are called post-posed adjuncts.

c)

Mixed modification that comprises

all the units in both pre-head and post-head position: two smart hard-working

students from Boston.

) Noun-phrases with pre-posed

adjuncts.noun-phrases with pre-posed modifiers we generally find adjectives, pronouns,

numerals, participles, gerunds, nouns, nouns in the genitive case (see the

table) [8; p. 43]. According to their position all pre-posed adjuncts may be

divided into pre-adjectivals and adjectiavals. The position of adjectivals is

usually right before the noun-head. Pre-adjectivals occupy the position before

adjectivals. They fall into two groups: a) limiters (to this group belong

mostly particles): just, only, even, etc. and b) determiners (articles,

possessive pronouns, quantifiers — the first, the last).of nouns by nouns (N+N)

is one of the most striking features about the grammatical organization of

English. It is one of devices to make our speech both laconic and expressive at

the same time. Noun-adjunct groups result from different kinds of transformational

shifts. NPs with pre-posed adjuncts can signal a striking variety of

meanings:peace — peace all over the worldbox — a box made of silverlamp — lamp

for tableslegs — the legs of the tablesand — sand from the riverchild — a child

who goes to schoolgrammatical relations observed in NPs with pre-posed adjuncts

may convey the following meanings:

1)

subject-predicate relations: weather

change;

2)

object relations: health service,

women hater;

3)

adverbial relations: a) of time:

morning star,

b) place: world peace, country

house,) comparison: button eyes,) purpose: tooth brush.is important to remember

that the noun-adjunct is usually marked by a stronger stress than the

head.special interest is a kind of ‘grammatical idiom’ where the modifier is

reinterpreted into the head: a devil of a man, an angel of a girl.

) Noun-phrases with post-posed

adjuncts.with post-posed may be classified according to the way of connection

into prepositionless and prepositional. The basic prepositionless NPs with post-posed

adjuncts are: Nadj. — tea strong, NVen — the shape unknown, NVing — the girl

smiling, ND — the man downstairs, NVinf — a book to read, NNum — room

ten.pattern of basic prepositional NPs is N1 prep. N2. The most common

preposition here is ‘of’ — a cup of tea, a man of courage. It may have quite

different meanings: qualitative — a woman of sense, predicative — the pleasure

of the company, objective — the reading of the newspaper, partitive — the roof

of the house.

) The verb-phrase.VP is a definite

kind of the subordinate phrase with the verb as the head. The verb is

considered to be the semantic and structural centre not only of the VP but of

the whole sentence as the verb plays an important role in making up primary

predication that serves the basis for the sentence. VPs are more complex than

NPs as there are a lot of ways in which verbs may be combined in actual usage.

Valent properties of different verbs and their semantics make it possible to

divide all the verbs into several groups depending on the nature of their

complements [7; p. 91].of verb-phrases.can be classified according to the

nature of their complements — verb complements may be nominal (to see a house)

and adverbial (to behave well). Consequently, we distinguish nominal, adverbial

and mixed complementation.complementation takes place when one or more nominal

complements (nouns or pronouns) are obligatory for the realization of potential

valency of the verb: to give smth. to smb., to phone smb., to hear smth.(smb.),

etc.complementation occurs when the verb takes one or more adverbial elements

obligatory for the realization of its potential valency: He behaved well, I

live …in Kyiv (here).complementation — both nominal and adverbial elements are

obligatory: He put his hat on he table (nominal-adverbial).to the structure VPs

may be basic or simple (to take a book) — all elements are obligatory; expanded

(to read and translate the text, to read books and newspapers) and extended (to

read an English book).

) Predicative word-groups.word

combinations are distinguished on the basis of secondary predication. Like

sentences, predicative word-groups are binary in their structure but actually

differ essentially in their organization. The sentence is an independent

communicative unit based on primary predication while the predicative

word-group is a dependent syntactic unit that makes up a part of the sentence.

The predicative word-group consists of a nominal element (noun, pronoun) and a

non-finite form of the verb: N + Vnon-fin. There are Gerundial, Infinitive and

Participial word-groups (complexes) in the English language: his reading, for

me to know, the boy running, etc.)

. Semantic features of word-groups

word-group is the largest two-facet

lexical unit comprising more than one word but expressing one global

concept.lexical meaning of the word groups is the combined lexical meaning of

the component words. The meaning of the word groups is motivated by the

meanings of the component members and is supported by the structural pattern.

But it’s not a mere sum total of all these meanings! Polysemantic words are

used in word groups only in 1 of their meanings. These meanings of the