|

England |

|

|---|---|

|

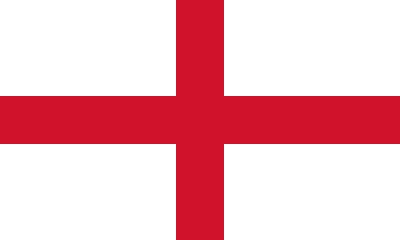

Flag Royal Arms |

|

| Anthem: Various Predominantly «God Save the King» (National anthem of the United Kingdom) |

|

Location of England (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) |

|

| Status | Country |

| Capital

and largest city |

London 51°30′N 0°7′W / 51.500°N 0.117°W |

| National language | English |

| Regional languages | Cornish |

| Ethnic groups

(2021) |

|

| Religion

(2021) |

|

| Demonym(s) | English |

|

|

| Government | Part of a constitutional monarchy, direct government exercised by the government of the United Kingdom |

|

• Monarch |

Charles III |

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | |

| • House of Commons | 533 MPs (of 650) |

| Establishment | |

|

• Unification of Angles, Saxons and Danes |

12 July 927 |

|

• Union with Scotland |

1 May 1707 |

| Area | |

|

• Land |

130,279 km2 (50,301 sq mi)[1] |

| Population | |

|

• 2021 census |

|

|

• Density |

434/km2 (1,124.1/sq mi) |

| GVA | 2020 estimate |

| • Total | £1.683 trillion[3] |

| • Per capita | £29,757 |

| Currency | Pound sterling (GBP) |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (Greenwich Mean Time) |

|

• Summer (DST) |

UTC+1 (British Summer Time) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (AD) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +44 |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-ENG |

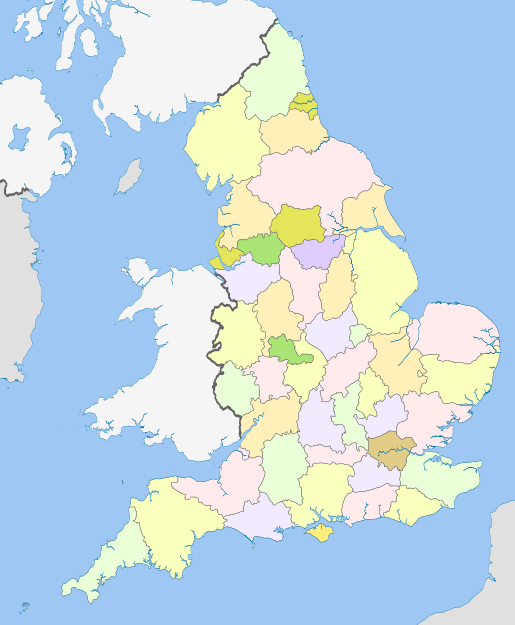

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom.[4] It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea area of the Atlantic Ocean to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe by the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south. The country covers five-eighths of the island of Great Britain, which lies in the North Atlantic, and includes over 100 smaller islands, such as the Isles of Scilly and the Isle of Wight.

The area now called England was first inhabited by modern humans during the Upper Paleolithic period, but takes its name from the Angles, a Germanic tribe deriving its name from the Anglia peninsula, who settled during the 5th and 6th centuries. England became a unified state in the 10th century and has had a significant cultural and legal impact on the wider world since the Age of Discovery, which began during the 15th century.[5]

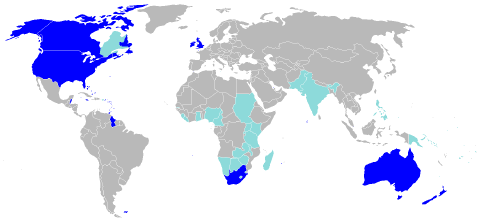

The English language, the Anglican Church, and English law, which collectively served as the basis for the common law legal systems of many other countries around the world, developed in England, and the country’s parliamentary system of government has been widely adopted by other nations.[6] The Industrial Revolution began in 18th-century England, transforming its society into the world’s first industrialised nation.[7] England is also home to the two oldest institutions of higher learning in the English-speaking world, the University of Cambridge, founded in 1209, and the University of Oxford, founded in 1096, both of which are routinely ranked among the most prestigious universities globally.[8]

England’s terrain is chiefly low hills and plains, especially in the centre and south. Upland and mountainous terrain is mostly restricted to the north and west, including the Lake District, Pennines, Dartmoor and Shropshire Hills. The capital is London, whose greater metropolitan population of 14.2 million as of 2021 represents the United Kingdom’s largest metropolitan area. England’s population of 56.3 million comprises 84% of the population of the United Kingdom,[9] largely concentrated around London, the South East, and conurbations in the Midlands, the North West, the North East, and Yorkshire, which each developed as major industrial regions during the 19th century.[10]

The Kingdom of England, which after 1535 included Wales, ceased being a separate sovereign state on 1 May 1707, when the Acts of Union put into effect the terms agreed in the Treaty of Union the previous year, resulting in a political union with the Kingdom of Scotland to create the Kingdom of Great Britain.[11] In 1801, Great Britain was united with the Kingdom of Ireland through another Act of Union to become the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. In 1922, the Irish Free State seceded from the United Kingdom, leading to the latter being renamed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.[12]

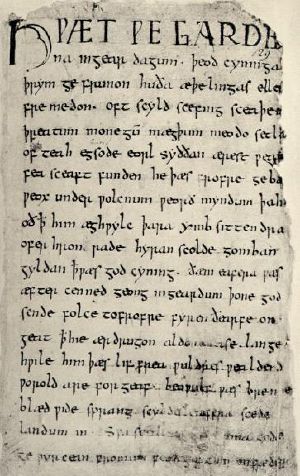

Toponymy

The name «England» is derived from the Old English name Englaland, which means «land of the Angles».[13] The Angles were one of the Germanic tribes that settled in Great Britain during the Early Middle Ages. The Angles came from the Anglia peninsula in the Bay of Kiel area (present-day German state of Schleswig-Holstein) of the Baltic Sea.[14] The earliest recorded use of the term, as «Engla londe«, is in the late-ninth-century translation into Old English of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. The term was then used in a different sense to the modern one, meaning «the land inhabited by the English», and it included English people in what is now south-east Scotland but was then part of the English kingdom of Northumbria. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded that the Domesday Book of 1086 covered the whole of England, meaning the English kingdom, but a few years later the Chronicle stated that King Malcolm III went «out of Scotlande into Lothian in Englaland», thus using it in the more ancient sense.[15]

The earliest attested reference to the Angles occurs in the 1st-century work by Tacitus, Germania, in which the Latin word Anglii is used.[16] The etymology of the tribal name itself is disputed by scholars; it has been suggested that it derives from the shape of the Angeln peninsula, an angular shape.[17] How and why a term derived from the name of a tribe that was less significant than others, such as the Saxons, came to be used for the entire country and its people is not known, but it seems this is related to the custom of calling the Germanic people in Britain Angli Saxones or English Saxons to distinguish them from continental Saxons (Eald-Seaxe) of Old Saxony between the Weser and Eider rivers in Northern Germany.[18] In Scottish Gaelic, another language which developed on the island of Great Britain, the Saxon tribe gave their name to the word for England (Sasunn);[19] similarly, the Welsh name for the English language is «Saesneg«. A romantic name for England is Loegria, related to the Welsh word for England, Lloegr, and made popular by its use in Arthurian legend. Albion is also applied to England in a more poetic capacity,[20] though its original meaning is the island of Britain as a whole.

History

Prehistory and antiquity

The earliest known evidence of human presence in the area now known as England was that of Homo antecessor, dating to approximately 780,000 years ago. The oldest proto-human bones discovered in England date from 500,000 years ago.[21] Modern humans are known to have inhabited the area during the Upper Paleolithic period, though permanent settlements were only established within the last 6,000 years.[22]

After the last ice age only large mammals such as mammoths, bison and woolly rhinoceros remained. Roughly 11,000 years ago, when the ice sheets began to recede, humans repopulated the area; genetic research suggests they came from the northern part of the Iberian Peninsula.[23] The sea level was lower than the present day and Britain was connected by land bridge to Ireland and Eurasia.[24]

As the seas rose, it was separated from Ireland 10,000 years ago and from Eurasia two millennia later.

The Beaker culture arrived around 2,500 BC, introducing drinking and food vessels constructed from clay, as well as vessels used as reduction pots to smelt copper ores.[25] It was during this time that major Neolithic monuments such as Stonehenge and Avebury were constructed. By heating together tin and copper, which were in abundance in the area, the Beaker culture people made bronze, and later iron from iron ores. The development of iron smelting allowed the construction of better ploughs, advancing agriculture (for instance, with Celtic fields), as well as the production of more effective weapons.[26]

During the Iron Age, Celtic culture, deriving from the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures, arrived from Central Europe. Brythonic was the spoken language during this time. Society was tribal; according to Ptolemy’s Geographia there were around 20 tribes in the area. Earlier divisions are unknown because the Britons were not literate. Like other regions on the edge of the Empire, Britain had long enjoyed trading links with the Romans. Julius Caesar of the Roman Republic attempted to invade twice in 55 BC; although largely unsuccessful, he managed to set up a client king from the Trinovantes.

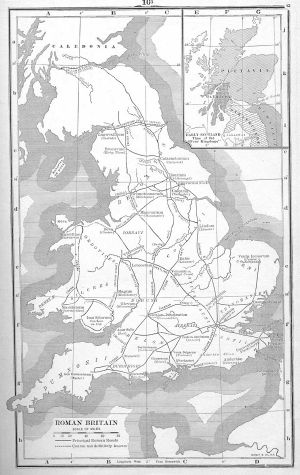

The Romans invaded Britain in 43 AD during the reign of Emperor Claudius, subsequently conquering much of Britain, and the area was incorporated into the Roman Empire as Britannia province.[27] The best-known of the native tribes who attempted to resist were the Catuvellauni led by Caratacus. Later, an uprising led by Boudica, Queen of the Iceni, ended with Boudica’s suicide following her defeat at the Battle of Watling Street.[28] The author of one study of Roman Britain suggested that from 43 AD to 84 AD, the Roman invaders killed somewhere between 100,000 and 250,000 people from a population of perhaps 2,000,000.[29] This era saw a Greco-Roman culture prevail with the introduction of Roman law, Roman architecture, aqueducts, sewers, many agricultural items and silk.[30] In the 3rd century, Emperor Septimius Severus died at Eboracum (now York), where Constantine was subsequently proclaimed emperor a century later.[31]

There is debate about when Christianity was first introduced; it was no later than the 4th century, probably much earlier. According to Bede, missionaries were sent from Rome by Eleutherius at the request of the chieftain Lucius of Britain in 180 AD, to settle differences as to Eastern and Western ceremonials, which were disturbing the church. There are traditions linked to Glastonbury claiming an introduction through Joseph of Arimathea, while others claim through Lucius of Britain.[32] By 410, during the decline of the Roman Empire, Britain was left exposed by the end of Roman rule in Britain and the withdrawal of Roman army units, to defend the frontiers in continental Europe and partake in civil wars.[33] Celtic Christian monastic and missionary movements flourished: Patrick (5th-century Ireland) and in the 6th century Brendan (Clonfert), Comgall (Bangor), David (Wales), Aiden (Lindisfarne) and Columba (Iona). This period of Christianity was influenced by ancient Celtic culture in its sensibilities, polity, practices and theology. Local «congregations» were centred in the monastic community and monastic leaders were more like chieftains, as peers, rather than in the more hierarchical system of the Roman-dominated church.[34]

Middle Ages

Roman military withdrawals left Britain open to invasion by pagan, seafaring warriors from north-western continental Europe, chiefly the Saxons, Angles, Jutes and Frisians who had long raided the coasts of the Roman province. These groups then began to settle in increasing numbers over the course of the fifth and sixth centuries, initially in the eastern part of the country.[33] Their advance was contained for some decades after the Britons’ victory at the Battle of Mount Badon, but subsequently resumed, overrunning the fertile lowlands of Britain and reducing the area under Brittonic control to a series of separate enclaves in the more rugged country to the west by the end of the 6th century. Contemporary texts describing this period are extremely scarce, giving rise to its description as a Dark Age. The nature and progression of the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain is consequently subject to considerable disagreement; the emerging consensus is that it occurred on a large scale in the south and east but was less substantial to the north and west, where Celtic languages continued to be spoken even in areas under Anglo-Saxon control.[35][36] Roman-dominated Christianity had, in general, been replaced in the conquered territories by Anglo-Saxon paganism, but was reintroduced by missionaries from Rome led by Augustine from 597 onwards.[37] Disputes between the Roman- and Celtic-dominated forms of Christianity ended in victory for the Roman tradition at the Council of Whitby (664), which was ostensibly about tonsures (clerical haircuts) and the date of Easter, but more significantly, about the differences in Roman and Celtic forms of authority, theology, and practice.[34]

During the settlement period the lands ruled by the incomers seem to have been fragmented into numerous tribal territories, but by the 7th century, when substantial evidence of the situation again becomes available, these had coalesced into roughly a dozen kingdoms including Northumbria, Mercia, Wessex, East Anglia, Essex, Kent and Sussex. Over the following centuries, this process of political consolidation continued.[38] The 7th century saw a struggle for hegemony between Northumbria and Mercia, which in the 8th century gave way to Mercian preeminence.[39] In the early 9th century Mercia was displaced as the foremost kingdom by Wessex. Later in that century escalating attacks by the Danes culminated in the conquest of the north and east of England, overthrowing the kingdoms of Northumbria, Mercia and East Anglia. Wessex under Alfred the Great was left as the only surviving English kingdom, and under his successors, it steadily expanded at the expense of the kingdoms of the Danelaw. This brought about the political unification of England, first accomplished under Æthelstan in 927 and definitively established after further conflicts by Eadred in 953. A fresh wave of Scandinavian attacks from the late 10th century ended with the conquest of this united kingdom by Sweyn Forkbeard in 1013 and again by his son Cnut in 1016, turning it into the centre of a short-lived North Sea Empire that also included Denmark and Norway. However, the native royal dynasty was restored with the accession of Edward the Confessor in 1042.

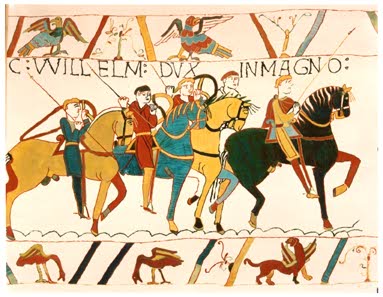

A dispute over the succession to Edward led to the Norman Conquest in 1066, accomplished by an army led by Duke William of Normandy.[40] The Normans themselves originated from Scandinavia and had settled in Normandy in the late 9th and early 10th centuries.[41] This conquest led to the almost total dispossession of the English elite and its replacement by a new French-speaking aristocracy, whose speech had a profound and permanent effect on the English language.[42]

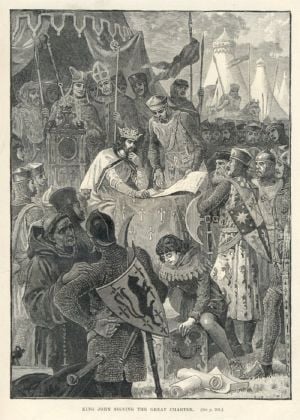

Subsequently, the House of Plantagenet from Anjou inherited the English throne under Henry II, adding England to the budding Angevin Empire of fiefs the family had inherited in France including Aquitaine.[43] They reigned for three centuries, some noted monarchs being Richard I, Edward I, Edward III and Henry V.[43] The period saw changes in trade and legislation, including the signing of the Magna Carta, an English legal charter used to limit the sovereign’s powers by law and protect the privileges of freemen. Catholic monasticism flourished, providing philosophers, and the universities of Oxford and Cambridge were founded with royal patronage. The Principality of Wales became a Plantagenet fief during the 13th century[44] and the Lordship of Ireland was given to the English monarchy by the Pope.

During the 14th century, the Plantagenets and the House of Valois both claimed to be legitimate claimants to the House of Capet and with it France; the two powers clashed in the Hundred Years’ War.[45] The Black Death epidemic hit England; starting in 1348, it eventually killed up to half of England’s inhabitants.[46] From 1453 to 1487 civil war occurred between two branches of the royal family – the Yorkists and Lancastrians – known as the Wars of the Roses.[47] Eventually it led to the Yorkists losing the throne entirely to a Welsh noble family the Tudors, a branch of the Lancastrians headed by Henry Tudor who invaded with Welsh and Breton mercenaries, gaining victory at the Battle of Bosworth Field where the Yorkist king Richard III was killed.[48]

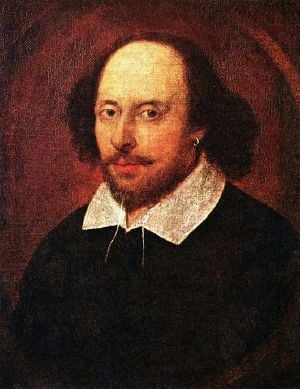

Early modern

During the Tudor period, the Renaissance reached England through Italian courtiers, who reintroduced artistic, educational and scholarly debate from classical antiquity.[49] England began to develop naval skills, and exploration to the West intensified.[50] Henry VIII broke from communion with the Catholic Church, over issues relating to his divorce, under the Acts of Supremacy in 1534 which proclaimed the monarch head of the Church of England. In contrast with much of European Protestantism, the roots of the split were more political than theological.[a] He also legally incorporated his ancestral land Wales into the Kingdom of England with the 1535–1542 acts. There were internal religious conflicts during the reigns of Henry’s daughters, Mary I and Elizabeth I. The former took the country back to Catholicism while the latter broke from it again, forcefully asserting the supremacy of Anglicanism. The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor age of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I («the Virgin Queen»). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. Elizabethan England represented the apogee of the English Renaissance and saw the flowering of art, poetry, music and literature.[52] The era is most famous for its drama, theatre and playwrights. England during this period had a centralised, well-organised, and effective government as a result of vast Tudor reforms.[53]

Competing with Spain, the first English colony in the Americas was founded in 1585 by explorer Walter Raleigh in Virginia and named Roanoke. The Roanoke colony failed and is known as the lost colony after it was found abandoned on the return of the late-arriving supply ship.[54] With the East India Company, England also competed with the Dutch and French in the East. During the Elizabethan period, England was at war with Spain. An armada sailed from Spain in 1588 as part of a wider plan to invade England and re-establish a Catholic monarchy. The plan was thwarted by bad coordination, stormy weather and successful harrying attacks by an English fleet under Lord Howard of Effingham. This failure did not end the threat: Spain launched two further armadas, in 1596 and 1597, but both were driven back by storms. The political structure of the island changed in 1603, when the King of Scots, James VI, a kingdom which had been a long-time rival to English interests, inherited the throne of England as James I, thereby creating a personal union.[55] He styled himself King of Great Britain, although this had no basis in English law.[56] Under the auspices of James VI and I the Authorised King James Version of the Holy Bible was published in 1611. It was the standard version of the Bible read by most Protestant Christians for four hundred years until modern revisions were produced in the 20th century.

Based on conflicting political, religious and social positions, the English Civil War was fought between the supporters of Parliament and those of King Charles I, known colloquially as Roundheads and Cavaliers respectively. This was an interwoven part of the wider multifaceted Wars of the Three Kingdoms, involving Scotland and Ireland. The Parliamentarians were victorious, Charles I was executed and the kingdom replaced by the Commonwealth. Leader of the Parliament forces, Oliver Cromwell declared himself Lord Protector in 1653; a period of personal rule followed.[57] After Cromwell’s death and the resignation of his son Richard as Lord Protector, Charles II was invited to return as monarch in 1660, in a move called the Restoration. With the reopening of theatres, fine arts, literature and performing arts flourished throughout the Restoration of »the Merry Monarch» Charles II.[58] After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, it was constitutionally established that King and Parliament should rule together, though Parliament would have the real power. This was established with the Bill of Rights in 1689. Among the statutes set down were that the law could only be made by Parliament and could not be suspended by the King, also that the King could not impose taxes or raise an army without the prior approval of Parliament.[59] Also since that time, no British monarch has entered the House of Commons when it is sitting, which is annually commemorated at the State Opening of Parliament by the British monarch when the doors of the House of Commons are slammed in the face of the monarch’s messenger, symbolising the rights of Parliament and its independence from the monarch.[60] With the founding of the Royal Society in 1660, science was greatly encouraged.

In 1666, the Great Fire of London gutted the City of London but it was rebuilt shortly afterwards[61] with many significant buildings designed by Christopher Wren. In Parliament two factions had emerged – the Tories and Whigs. Though the Tories initially supported Catholic king James II, some of them, along with the Whigs, during the Revolution of 1688 invited Dutch Prince William of Orange to defeat James and ultimately to become William III of England. Some English people, especially in the north, were Jacobites and continued to support James and his sons. Under the Stuart dynasty England expanded in trade, finance and prosperity. Britain developed Europe’s largest merchant fleet.[62] After the parliaments of England and Scotland agreed,[63] the two countries joined in political union, to create the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707.[55] To accommodate the union, institutions such as the law and national churches of each remained separate.[64]

Late modern and contemporary

Under the newly formed Kingdom of Great Britain, output from the Royal Society and other English initiatives combined with the Scottish Enlightenment to create innovations in science and engineering, while the enormous growth in British overseas trade protected by the Royal Navy paved the way for the establishment of the British Empire. Domestically it drove the Industrial Revolution, a period of profound change in the socioeconomic and cultural conditions of England, resulting in industrialised agriculture, manufacture, engineering and mining, as well as new and pioneering road, rail and water networks to facilitate their expansion and development.[65] The opening of Northwest England’s Bridgewater Canal in 1761 ushered in the canal age in Britain.[66] In 1825 the world’s first permanent steam locomotive-hauled passenger railway – the Stockton and Darlington Railway – opened to the public.[66]

During the Industrial Revolution, many workers moved from England’s countryside to new and expanding urban industrial areas to work in factories, for instance at Birmingham and Manchester, dubbed «Workshop of the World» and «Warehouse City» respectively.[68] Manchester was the world’s first industrial city.[69] England maintained relative stability throughout the French Revolution; William Pitt the Younger was British prime minister for the reign of George III. The Regency of George IV is noted for its elegance and achievements in the fine arts and architecture.[70] During the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon planned to invade from the south-east. However, this failed to manifest and the Napoleonic forces were defeated by the British: at sea by Horatio Nelson, and on land by Arthur Wellesley. The major victory at the Battle of Trafalgar confirmed the naval supremacy Britain had established during the course of the eighteenth century.[71] The Napoleonic Wars fostered a concept of Britishness and a united national British people, shared with the English, Scots and Welsh.[72]

London became the largest and most populous metropolitan area in the world during the Victorian era, and trade within the British Empire – as well as the standing of the British military and navy – was prestigious.[73] Technologically, this era saw many innovations that proved key to the United Kingdom’s power and prosperity.[74] Political agitation at home from radicals such as the Chartists and the suffragettes enabled legislative reform and universal suffrage.[75] Samuel Hynes described the Edwardian era as a «leisurely time when women wore picture hats and did not vote, when the rich were not ashamed to live conspicuously, and the sun really never set on the British flag.»[76]

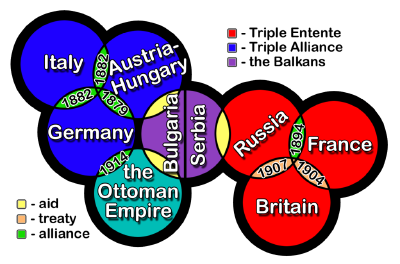

Power shifts in east-central Europe led to World War I; hundreds of thousands of English soldiers died fighting for the United Kingdom as part of the Allies.[b] Two decades later, in World War II, the United Kingdom was again one of the Allies. At the end of the Phoney War, Winston Churchill became the wartime prime minister. Developments in warfare technology saw many cities damaged by air-raids during the Blitz. Following the war, the British Empire experienced rapid decolonisation, and there was a speeding-up of technological innovations; automobiles became the primary means of transport and Frank Whittle’s development of the jet engine led to wider air travel.[78] Residential patterns were altered in England by private motoring, and by the creation of the National Health Service (NHS) in 1948. The UK’s NHS provided publicly funded health care to all UK permanent residents free at the point of need, being paid for from general taxation. Combined, these prompted the reform of local government in England in the mid-20th century.[79]

Since the 20th century, there has been significant population movement to England, mostly from other parts of the British Isles, but also from the Commonwealth, particularly the Indian subcontinent.[80] Since the 1970s there has been a large move away from manufacturing and an increasing emphasis on the service industry.[81] As part of the United Kingdom, the area joined a common market initiative called the European Economic Community which became the European Union. Since the late 20th century the administration of the United Kingdom has moved towards devolved governance in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.[82] England and Wales continues to exist as a jurisdiction within the United Kingdom.[83] Devolution has stimulated a greater emphasis on a more English-specific identity and patriotism.[84] There is no devolved English government, but an attempt to create a similar system on a sub-regional basis was rejected by referendum.[85]

Governance

Politics

England is part of the United Kingdom, a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system.[86] There has not been a government of England since 1707, when the Acts of Union 1707, putting into effect the terms of the Treaty of Union, joined England and Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.[63] Before the union England was ruled by its monarch and the Parliament of England. Today England is governed directly by the Parliament of the United Kingdom, although other countries of the United Kingdom have devolved governments.[87] In the House of Commons which is the lower house of the British Parliament based at the Palace of Westminster, there are 532 Members of Parliament (MPs) for constituencies in England, out of the 650 total.[88] As of the 2019 United Kingdom general election, England is represented by 345 MPs from the Conservative Party, 179 from the Labour Party, seven from the Liberal Democrats, one from the Green Party, and the Speaker of the House, Lindsay Hoyle.

Since devolution, in which other countries of the United Kingdom – Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland – each have their own devolved parliament or assemblies for local issues, there has been debate about how to counterbalance this in England. Originally it was planned that various regions of England would be devolved, but following the proposal’s rejection by the North East in a 2004 referendum, this has not been carried out.[85]

One major issue is the West Lothian question, in which MPs from Scotland and Wales are able to vote on legislation affecting only England, while English MPs have no equivalent right to legislate on devolved matters.[89] This when placed in the context of England being the only country of the United Kingdom not to have free prescriptions and free top-up university fees,[90] has led to a steady rise in English nationalism.[91] Some have suggested the creation of a devolved English parliament,[92] while others have proposed simply limiting voting on legislation which only affects England to English MPs.[93]

Law

The English law legal system, developed over the centuries, is the basis of common law[94] legal systems used in most Commonwealth countries[95] and the United States (except Louisiana). Despite now being part of the United Kingdom, the legal system of the Courts of England and Wales continued, under the Treaty of Union, as a separate legal system from the one used in Scotland. The general essence of English law is that it is made by judges sitting in courts, applying their common sense and knowledge of legal precedent – stare decisis – to the facts before them.[96]

The court system is headed by the Senior Courts of England and Wales, consisting of the Court of Appeal, the High Court of Justice for civil cases, and the Crown Court for criminal cases.[97] The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom is the highest court for criminal and civil cases in England and Wales. It was created in 2009 after constitutional changes, taking over the judicial functions of the House of Lords.[98] A decision of the Supreme Court is binding on every other court in the hierarchy, which must follow its directions.[99]

The Secretary of State for Justice is the minister responsible to Parliament for the judiciary, the court system and prisons and probation in England.[100] Crime increased between 1981 and 1995 but fell by 42% in the period 1995–2006.[101] The prison population doubled over the same period, giving it one of the highest incarceration rates in Western Europe at 147 per 100,000.[102] His Majesty’s Prison Service, reporting to the Ministry of Justice, manages most prisons, housing 81,309 prisoners in England and Wales as of September 2022.[103]

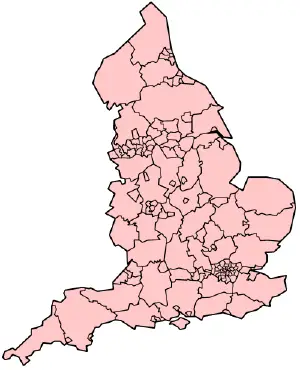

Regions, counties, and districts

The subdivisions of England consist of up to four levels of subnational division controlled through a variety of types of administrative entities created for the purposes of local government. The highest tier of local government were the nine regions of England: North East, North West, Yorkshire and the Humber, East Midlands, West Midlands, East, South East, South West, and London. These were created in 1994 as Government Offices, used by the UK government to deliver a wide range of policies and programmes regionally, but there are no elected bodies at this level, except in London, and in 2011 the regional government offices were abolished.[104]

After devolution began to take place in other parts of the United Kingdom it was planned that referendums for the regions of England would take place for their own elected regional assemblies as a counterweight. London accepted in 1998: the London Assembly was created two years later. However, when the proposal was rejected by the 2004 North East England devolution referendum in the North East, further referendums were cancelled.[85] The regional assemblies outside London were abolished in 2010, and their functions transferred to respective regional development agencies and a new system of local authority leaders’ boards.[105]

Below the regional level, all of England is divided into 48 ceremonial counties.[106] These are used primarily as a geographical frame of reference and have developed gradually since the Middle Ages, with some established as recently as 1974.[107] Each has a lord lieutenant and high sheriff; these posts are used to represent the British monarch locally.[106] Outside Greater London and the Isles of Scilly, England is also divided into 83 metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties; these correspond to areas used for the purposes of local government[108] and may consist of a single district or be divided into several.

There are six metropolitan counties based on the most heavily urbanised areas, which do not have county councils.[108] In these areas the principal authorities are the councils of the subdivisions, the metropolitan boroughs. Elsewhere, 27 non-metropolitan «shire» counties have a county council and are divided into districts, each with a district council. They are typically, though not always, found in more rural areas. The remaining non-metropolitan counties are of a single district and usually correspond to large towns or sparsely populated counties; they are known as unitary authorities. Greater London has a different system for local government, with 32 London boroughs, plus the City of London covering a small area at the core governed by the City of London Corporation.[109] At the most localised level, much of England is divided into civil parishes with councils; in Greater London only one, Queen’s Park, exists as of 2014 after they were abolished in 1965 until legislation allowed their recreation in 2007.

Geography

Landscape and rivers

Geographically, England includes the central and southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain, plus such offshore islands as the Isle of Wight and the Isles of Scilly. It is bordered by two other countries of the United Kingdom: to the north by Scotland and to the west by Wales. England is closer than any other part of mainland Britain to the European continent. It is separated from France (Hauts-de-France) by a 21-mile (34 km)[110] sea gap, though the two countries are connected by the Channel Tunnel near Folkestone.[111] England also has shores on the Irish Sea, North Sea and Atlantic Ocean.

The ports of London, Liverpool, and Newcastle lie on the tidal rivers Thames, Mersey and Tyne respectively. At 220 miles (350 km), the Severn is the longest river flowing through England.[112] It empties into the Bristol Channel and is notable for its Severn Bore (a tidal bore), which can reach 2 metres (6.6 ft) in height.[113] However, the longest river entirely in England is the Thames, which is 215 miles (346 km) in length.[114]

There are many lakes in England; the largest is Windermere, within the aptly named Lake District.[115] Most of England’s landscape consists of low hills and plains, with upland and mountainous terrain in the north and west of the country. The northern uplands include the Pennines, a chain of uplands dividing east and west, the Lake District mountains in Cumbria, and the Cheviot Hills, straddling the border between England and Scotland. The highest point in England, at 978 metres (3,209 ft), is Scafell Pike in the Lake District.[115] The Shropshire Hills are near Wales while Dartmoor and Exmoor are two upland areas in the south-west of the country. The approximate dividing line between terrain types is often indicated by the Tees–Exe line.[116]

In geological terms, the Pennines, known as the «backbone of England», are the oldest range of mountains in the country, originating from the end of the Paleozoic Era around 300 million years ago.[117] Their geological composition includes, among others, sandstone and limestone, and also coal. There are karst landscapes in calcite areas such as parts of Yorkshire and Derbyshire. The Pennine landscape is high moorland in upland areas, indented by fertile valleys of the region’s rivers. They contain two national parks, the Yorkshire Dales and the Peak District. In the West Country, Dartmoor and Exmoor of the Southwest Peninsula include upland moorland supported by granite, and enjoy a mild climate; both are national parks.[118]

The English Lowlands are in the central and southern regions of the country, consisting of green rolling hills, including the Cotswold Hills, Chiltern Hills, North and South Downs; where they meet the sea they form white rock exposures such as the cliffs of Dover. This also includes relatively flat plains such as the Salisbury Plain, Somerset Levels, South Coast Plain and The Fens.

Climate

England has a temperate maritime climate: it is mild with temperatures not much lower than 0 °C (32 °F) in winter and not much higher than 32 °C (90 °F) in summer.[119] The weather is damp relatively frequently and is changeable. The coldest months are January and February, the latter particularly on the English coast, while July is normally the warmest month. Months with mild to warm weather are May, June, September and October.[119] Rainfall is spread fairly evenly throughout the year.

Important influences on the climate of England are its proximity to the Atlantic Ocean, its northern latitude and the warming of the sea by the Gulf Stream.[119] Rainfall is higher in the west, and parts of the Lake District receive more rain than anywhere else in the country.[119] Since weather records began, the highest temperature recorded was 40.3 °C (104.5 °F) on 19 July 2022 at Coningsby, Lincolnshire,[120] while the lowest was −26.1 °C (−15.0 °F) on 10 January 1982 in Edgmond, Shropshire.[121]

Nature and wildlife

The fauna of England is similar to that of other areas in the British Isles with a wide range of vertebrate and invertebrate life in a diverse range of habitats.[124]

National nature reserves in England are designated by Natural England as key places for wildlife and natural features in England. They were established to protect the most significant areas of habitat and of geological formations. NNRs are managed on behalf of the nation, many by Natural England themselves, but also by non-governmental organisations, including the members of The Wildlife Trusts partnership, the National Trust, and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. There are 229 NNRs in England covering 939 square kilometres (363 square miles). Often they contain rare species or nationally important populations of plants and animals.[125]

The Environment Agency is a non-departmental public body, established in 1995 and sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs with responsibilities relating to the protection and enhancement of the environment in England.[126] The Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs is the minister responsible for environmental protection, agriculture, fisheries and rural communities in England.[127]

England has a temperate oceanic climate in most areas, lacking extremes of cold or heat, but does have a few small areas of subarctic and warmer areas in the South West. Towards the North of England the climate becomes colder and most of England’s mountains and high hills are located here and have a major impact on the climate and thus the local fauna of the areas. Deciduous woodlands are common across all of England and provide a great habitat for much of England’s wildlife, but these give way in northern and upland areas of England to coniferous forests (mainly plantations) which also benefit certain forms of wildlife. Some species have adapted to the expanded urban environment, particularly the red fox, which is the most successful urban mammal after the brown rat, and other animals such as common wood pigeon, both of which thrive in urban and suburban areas.[128]

Grey squirrels introduced from eastern America have forced the decline of the native red squirrel due to competition. Red squirrels are now confined to upland and coniferous-forested areas of England, mainly in the north, south west and Isle of Wight. England’s climate is very suitable for lagomorphs and the country has rabbits and brown hares which were introduced in Roman times.[129] Mountain hares which are indigenous have now been re-introduced in Derbyshire. The fauna of England has to cope with varying temperatures and conditions, although not extreme they do pose potential challenges and adaptational measures. English fauna has however had to cope with industrialisation, human population densities amongst the highest in Europe and intensive farming, but as England is a developed nation, wildlife and the countryside have entered the English mindset more and the country is very conscientious about preserving its wildlife, environment and countryside.[130]

Major conurbations

The Greater London Built-up Area is by far the largest urban area in England[131] and one of the busiest cities in the world. It is considered a global city and has a population larger than any other country in the United Kingdom besides England itself.[131] Other urban areas of considerable size and influence tend to be in northern England or the English Midlands.[131] There are 50 settlements which have designated city status in England, while the wider United Kingdom has 66.

While many cities in England are quite large, such as Birmingham, Sheffield, Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Newcastle, Bradford, Nottingham, population size is not a prerequisite for city status.[132] Traditionally the status was given to towns with diocesan cathedrals, so there are smaller cities like Wells, Ely, Ripon, Truro and Chichester.

Economy

The City of London is the financial capital of the United Kingdom and one of the largest financial centres in the world.[133]

England’s economy is one of the largest and most dynamic in the world, with an average GDP per capita of £28,100. HM Treasury, led by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, is responsible for developing and executing the government’s public finance policy and economic policy.[134] Usually regarded as a mixed market economy, it has adopted many free market principles, yet maintains an advanced social welfare infrastructure.[135] The official currency in England is the pound sterling, whose ISO 4217 code is GBP. Taxation in England is quite competitive when compared to much of the rest of Europe – as of 2014 the basic rate of personal tax is 20% on taxable income up to £31,865 above the personal tax-free allowance (normally £10,000), and 40% on any additional earnings above that amount.[136]

The economy of England is the largest part of the UK’s economy,[137] which has the 18th highest GDP PPP per capita in the world. England is a leader in the chemical[138] and pharmaceutical sectors and in key technical industries, particularly aerospace, the arms industry, and the manufacturing side of the software industry. London, home to the London Stock Exchange, the United Kingdom’s main stock exchange and the largest in Europe, is England’s financial centre, with 100 of Europe’s 500 largest corporations being based there.[139] London is the largest financial centre in Europe, and as of 2014 is the second largest in the world.[140]

The Bank of England, founded in 1694, is the United Kingdom’s central bank. Originally established as private banker to the government of England, since 1946 it has been a state-owned institution.[141] The bank has a monopoly on the issue of banknotes in England and Wales, although not in other parts of the United Kingdom. The government has devolved responsibility to the bank’s Monetary Policy Committee for managing the monetary policy of the country and setting interest rates.[142]

England is highly industrialised, but since the 1970s there has been a decline in traditional heavy and manufacturing industries, and an increasing emphasis on a more service industry oriented economy.[81] Tourism has become a significant industry, attracting millions of visitors to England each year. The export part of the economy is dominated by pharmaceuticals, cars (although many English marques are now foreign-owned, such as Land Rover, Lotus, Jaguar and Bentley), crude oil and petroleum from the English parts of North Sea oil along with Wytch Farm, aircraft engines and alcoholic beverages.[143] The creative industries accounted for 7 per cent GVA in 2005 and grew at an average of 6 per cent per annum between 1997 and 2005.[144]

Most of the UK’s £30 billion[145] aerospace industry is primarily based in England. The global market opportunity for UK aerospace manufacturers over the next two decades is estimated at £3.5 trillion.[146] GKN Aerospace, an expert in metallic and composite aerostructures involved in almost every civil and military fixed and rotary wing aircraft in production, is based in Redditch.[147]

BAE Systems makes large sections of the Typhoon Eurofighter at its sub-assembly plant in Samlesbury and assembles the aircraft for the RAF at its Warton plant, near Preston. It is also a principal subcontractor on the F35 Joint Strike Fighter – the world’s largest single defence project – for which it designs and manufactures a range of components including the aft fuselage, vertical and horizontal tail and wing tips and fuel system. It also manufactures the Hawk, the world’s most successful jet training aircraft.[147]

Rolls-Royce PLC is the world’s second-largest aero-engine manufacturer. Its engines power more than 30 types of commercial aircraft, and it has more 30,000 engines currently in service across both the civil and defence sectors. With a workforce of over 12,000 people, Derby has the largest concentration of Rolls-Royce employees in the UK. Rolls-Royce also produces low-emission power systems for ships; makes critical equipment and safety systems for the nuclear industry and powers offshore platforms and major pipelines for the oil and gas industry.[147][148] The pharmaceutical industry plays an important role in the economy, and the UK has the third-highest share of global pharmaceutical R&D expenditures.[149]

Much of the UK’s space industry is centred on EADS Astrium, based in Stevenage and Portsmouth. The company builds the buses – the underlying structure onto which the payload and propulsion systems are built – for most of the European Space Agency’s spacecraft, as well as commercial satellites. The world leader in compact satellite systems, Surrey Satellite Technology, is also part of Astrium.[147] Reaction Engines Limited, the company planning to build Skylon, a single-stage-to-orbit spaceplane using their SABRE rocket engine, a combined-cycle, air-breathing rocket propulsion system is based in Culham. The UK space industry was worth £9.1bn in 2011 and employed 29,000 people. It is growing at a rate of 7.5 per cent annually, according to its umbrella organisation, the UK Space Agency. In 2013, the British Government pledged £60 million to the Skylon project: this investment will provide support at a «crucial stage» to allow a full-scale prototype of the SABRE engine to be built.

Agriculture is intensive, highly mechanised and efficient by European standards, producing 60% of food needs with only 2% of the labour force.[150] Two-thirds of production is devoted to livestock, the other to arable crops.[151] The main crops that are grown are wheat, barley, oats, potatoes, sugar beets. England retains a significant, though much reduced fishing industry. Its fleets bring home fish of every kind, ranging from sole to herring. It is also rich in natural resources including coal, petroleum, natural gas, tin, limestone, iron ore, salt, clay, chalk, gypsum, lead, and silica.[152]

Science and technology

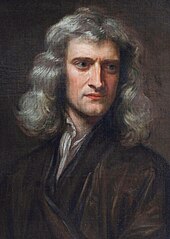

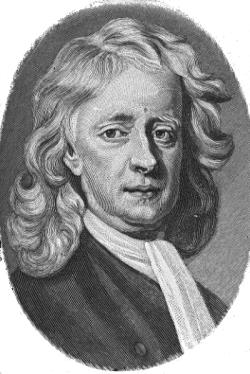

Prominent English figures from the field of science and mathematics include Sir Isaac Newton, Michael Faraday, Charles Darwin, Robert Hooke, James Prescott Joule, John Dalton, Lord Rayleigh, J. J. Thomson, James Chadwick, Charles Babbage, George Boole, Alan Turing, Tim Berners-Lee, Paul Dirac, Stephen Hawking, Peter Higgs, Roger Penrose, John Horton Conway, Thomas Bayes, Arthur Cayley, G. H. Hardy, Oliver Heaviside, Andrew Wiles, Edward Jenner, Francis Crick, Joseph Lister, Joseph Priestley, Thomas Young, Christopher Wren and Richard Dawkins. Some experts claim that the earliest concept of a metric system was invented by John Wilkins, the first secretary of the Royal Society, in 1668.[153]

England was a leading centre of the Scientific Revolution from the 17th century.[154] As the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, England was home to many significant inventors during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Famous English engineers include Isambard Kingdom Brunel, best known for the creation of the Great Western Railway, a series of famous steamships, and numerous important bridges, hence revolutionising public transport and modern-day engineering.[155] Thomas Newcomen’s steam engine helped spawn the Industrial Revolution.[156]

The Father of Railways, George Stephenson, built the first public inter-city railway line in the world, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, which opened in 1830. With his role in the marketing and manufacturing of the steam engine, and invention of modern coinage, Matthew Boulton (business partner of James Watt) is regarded as one of the most influential entrepreneurs in history.[157] The physician Edward Jenner’s smallpox vaccine is said to have «saved more lives … than were lost in all the wars of mankind since the beginning of recorded history.»[158]

Inventions and discoveries of the English include: the jet engine, the first industrial spinning machine, the first computer and the first modern computer, the World Wide Web along with HTML, the first successful human blood transfusion, the motorised vacuum cleaner,[160] the lawn mower, the seat belt, the hovercraft, the electric motor, steam engines, and theories such as the Darwinian theory of evolution and atomic theory. Newton developed the ideas of universal gravitation, Newtonian mechanics, and calculus, and Robert Hooke his eponymously named law of elasticity. Other inventions include the iron plate railway, the thermosiphon, tarmac, the rubber band, the mousetrap, «cat’s eye» road marker, joint development of the light bulb, steam locomotives, the modern seed drill and many modern techniques and technologies used in precision engineering.[161]

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge,[162] is a learned society and the United Kingdom’s national academy of sciences. Founded on 28 November 1660, it was granted a royal charter by King Charles II as «The Royal Society».[162] It is the oldest national scientific institution in the world.[163] The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, recognising excellence in science, supporting outstanding science, providing scientific advice for policy, fostering international and global co-operation, education and public engagement.[164]

The Royal Society started from groups of physicians and natural philosophers, meeting at a variety of locations, including Gresham College in London. They were influenced by the «new science», as promoted by Francis Bacon in his New Atlantis, from approximately 1645 onwards.[165] A group known as «The Philosophical Society of Oxford» was run under a set of rules still retained by the Bodleian Library.[166] After the English Restoration, there were regular meetings at Gresham College.[167] It is widely held that these groups were the inspiration for the foundation of the Royal Society.[166]

Scientific research and development remains important in the universities of England, with many establishing science parks to facilitate production and co-operation with industry.[168] Between 2004 and 2008 the United Kingdom produced 7 per cent of the world’s scientific research papers and had an 8 per cent share of scientific citations, the third and second-highest in the world (after the United States and China, respectively).[169] Scientific journals produced in England include Nature, the British Medical Journal and The Lancet. The Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, Secretary of State for Science, Innovation and Technology, and Minister of State for Science, Research and Innovation has responsibility for science in England.[170]

Transport

London St Pancras International is the UK’s 13th busiest railway terminus. The station is one of London’s main domestic and international transport hubs providing both commuter rail and high-speed rail services across the UK and to Paris, Lille and Brussels.

The Department for Transport is the government body responsible for overseeing transport in England. The department is run by the Secretary of State for Transport.

England has a dense and modern transportation infrastructure. There are many motorways in England, and many other trunk roads, such as the A1 Great North Road, which runs through eastern England from London to Newcastle[171] (much of this section is motorway) and onward to the Scottish border. The longest motorway in England is the M6, from Rugby through the North West up to the Anglo-Scottish border, a distance of 232 miles (373 km).[171] Other major routes include: the M1 from London to Leeds, the M25 which encircles London, the M60 which encircles Manchester, the M4 from London to South Wales, the M62 from Liverpool via Manchester to East Yorkshire, and the M5 from Birmingham to Bristol and the South West.[171]

Bus transport across the country is widespread; major companies include Arriva, FirstGroup, Go-Ahead Group, National Express, Rotala and Stagecoach Group. The red double-decker buses in London have become a symbol of England.

National Cycle Route offers cycling routes nationally. There is a rapid transit network in two English cities: the London Underground; and the Tyne and Wear Metro in Newcastle upon Tyne, Gateshead and Sunderland.[172] There are several tram networks, such as the Blackpool tramway, Manchester Metrolink, Sheffield Supertram and West Midlands Metro, and the Tramlink system centred on Croydon in South London.[172]

Great British Railways is a planned state-owned public body that will oversee rail transport in Great Britain from 2023. The Office of Rail and Road is responsible for the economic and safety regulation of England’s railways.[173]

Rail transport in England is the oldest in the world: passenger railways originated in England in 1825.[174] Much of Britain’s 10,000 miles (16,000 km) of rail network lies in England, covering the country fairly extensively, although a high proportion of railway lines were closed in the second half of the 20th century. There are plans to reopen lines such as the Varsity Line between Oxford and Cambridge. These lines are mostly standard gauge (single, double or quadruple track) though there are also a few narrow gauge lines. There is rail transport access to France and Belgium through an undersea rail link, the Channel Tunnel, which was completed in 1994.

Crossrail was Europe’s largest construction project with a £15 billion projected cost, opened in 2022.[175] High Speed 2, a new high-speed north–south railway line, projected in 2015 to cost £56 billion is to start being built in 2020.[176]

England has extensive domestic and international aviation links. The largest airport is Heathrow, which is the world’s busiest airport measured by number of international passengers.[177] Other large airports include Gatwick, Manchester, Stansted, Luton and Birmingham.[178]

By sea there is ferry transport, both local and international, including from Liverpool to Ireland and the Isle of Man, and Hull to the Netherlands and Belgium.[179] There are around 4,400 miles (7,100 km) of navigable waterways in England, half of which is owned by the Canal & River Trust,[179] however, water transport is very limited. The River Thames is the major waterway in England, with imports and exports focused at the Port of Tilbury in the Thames Estuary, one of the United Kingdom’s three major ports.[179]

Energy

Energy use in the United Kingdom stood at 2,249 TWh (193.4 million tonnes of oil equivalent) in 2014.[182] This equates to energy consumption per capita of 34.82 MWh (3.00 tonnes of oil equivalent) compared to a 2010 world average of 21.54 MWh (1.85 tonnes of oil equivalent).[183] Demand for electricity in 2014 was 34.42 GW on average[184] (301.7 TWh over the year) coming from a total electricity generation of 335.0 TWh.[185]

Successive UK governments have outlined numerous commitments to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Notably, the UK is one of the best sites in Europe for wind energy, and wind power production is its fastest growing supply.[181] Wind power contributed 15% of UK electricity generation in 2017.[186][187] England is home to Hornsea 2, the largest offshore wind farm in the world, situated in waters roughly 89 kilometres off the coast of Yorkshire.[188]

The Climate Change Act 2008 was passed in Parliament with an overwhelming majority across political parties. It sets out emission reduction targets that the UK must comply with legally. It represents the first global legally binding climate change mitigation target set by a country.[189] UK government energy policy aims to play a key role in limiting greenhouse gas emissions, whilst meeting energy demand. Shifting availabilities of resources and development of technologies also change the country’s energy mix through changes in costs.[190]

The current energy policy is the responsibility of the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero and Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero.[191] The Minister of State for Business, Energy and Clean Growth is responsible for green finance, climate science and innovation, and low carbon generation.[192] United Kingdom is ranked 4 out of 180 countries in the Environmental Performance Index.[193] A law has been passed that UK greenhouse gas emissions will be net zero by 2050.[194]

Tourism

English Heritage is a governmental body with a broad remit of managing the historic sites, artefacts and environments of England. It is currently sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport.[195]

The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty is a charity which also maintains multiple sites. Of the 25 United Kingdom UNESCO World Heritage Sites, 17 are in England.[196]

Some of the best known of these include Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites, Tower of London, Jurassic Coast, Palace of Westminster, Roman Baths, City of Bath, Saltaire, Ironbridge Gorge, Studley Royal Park and more recently the English Lake District. The northernmost point of the Roman Empire, Hadrian’s Wall, is the largest Roman artefact anywhere: it runs for a total of 73 miles (117 kilometres) in northern England.[197]

The Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport has overall responsibility for tourism, arts and culture, cultural property, heritage and historic environments, libraries, and museums and galleries.[198] The Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Arts, Heritage and Tourism is the minister with responsibility over tourism in England.[199]

A blue plaque, the oldest historical marker scheme in the world, is a permanent sign installed in a public place in England to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person or event. The scheme was the brainchild of politician William Ewart in 1863 and was initiated in 1866. It was formally established by the Royal Society of Arts in 1867, and since 1986 has been run by English Heritage. In 2011 there were around 1,600 museums in England.[200] Entry to most state-supported museums and galleries is free unlike in other countries.[201]

London is one of the world’s most visited cities, regularly taking the top five most visited cities in Europe.[202] It is largely considered a global centre of finance, arts and culture.[203]

Healthcare

The National Health Service (NHS), is the publicly funded healthcare system responsible for providing the majority of healthcare in the country. The NHS began on 5 July 1948, putting into effect the provisions of the National Health Service Act 1946. It was based on the findings of the Beveridge Report, prepared by economist and social reformer William Beveridge.[204] The NHS is largely funded from general taxation including National Insurance payments,[205] and it provides most of its services free at the point of use, although there are charges for some people for eye tests, dental care, prescriptions and aspects of personal care.[206]

The government department responsible for the NHS is the Department of Health, headed by the Secretary of State for Health, who sits in the British Cabinet. Most of the expenditure of the Department of Health is spent on the NHS—£98.6 billion was spent in 2008–2009.[207] In recent years the private sector has been increasingly used to provide more NHS services despite opposition by doctors and trade unions.[208]

When purchasing drugs, the NHS has significant market power that, based on its own assessment of the fair value of the drugs, influences the global price, typically keeping prices lower.[209] Several other countries either copy the UK’s model or directly rely on its assessments for their own decisions on state-financed drug reimbursements.[210] Regulatory bodies such as the General Medical Council and the Nursing and Midwifery Council are organised on a UK-wide basis, as are non-governmental bodies such as the Royal Colleges.

The average life expectancy of people in England is 77.5 years for males and 81.7 years for females, the highest of the four countries of the United Kingdom.[211] The South of England has a higher life expectancy than the North; however, regional differences do seem to be slowly narrowing: between 1991–1993 and 2012–2014, life expectancy in the North East increased by 6.0 years and in the North West by 5.8 years, the fastest increase in any region outside London, and the gap between life expectancy in the North East and South East is now 2.5 years, down from 2.9 in 1993.[211]

Demography

Population

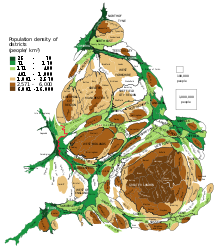

Population of England and Wales by administrative areas. Their size shows their population, with some approximation. Each group of squares in the map key is 20 % of total number of districts.

With over 56 million inhabitants, England is by far the most populous country of the United Kingdom, accounting for 84% of the combined total.[10]: 12 [212] England taken as a unit and measured against international states would be the 25th largest country by population in the world.[213]

The English people are British people.[214] Some genetic evidence suggests that 75–95% descend in the paternal line from prehistoric settlers who originally came from the Iberian Peninsula, as well as a 5% contribution from Angles and Saxons, and a significant Scandinavian (Viking) element.[215][216] However, other geneticists place the Germanic estimate up to half.[217] Over time, various cultures have been influential: Prehistoric, Brythonic,[218] Roman, Anglo-Saxon,[219] Viking (North Germanic),[220] Gaelic cultures, as well as a large influence from Normans. There is an English diaspora in former parts of the British Empire; especially the United States, Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand.[c] Since the late 1990s, many English people have migrated to Spain.[225]

In 1086, when the Domesday Book was compiled, England had a population of two million. About 10% lived in urban areas.[226] By 1801, the population was 8.3 million, and by 1901 30.5 million.[227] Due in particular to the economic prosperity of South East England, it has received many economic migrants from the other parts of the United Kingdom.[214] There has been significant Irish migration.[228] The proportion of ethnically European residents totals at 87.50%, including Germans[229] and Poles.[214]

Other people from much further afield in the former British colonies have arrived since the 1950s: in particular, 6% of people living in England have family origins in the Indian subcontinent, mostly India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.[214][229] About 0.7% of people are Chinese.[214][229] 2.90% of the population are black, from Africa and the Caribbean, especially former British colonies.[214][229] In 2007, 22% of primary school children in England were from ethnic minority families,[230] and in 2011 that figure was 26.5%.[231] About half of the population increase between 1991 and 2001 was due to immigration.[232] Debate over immigration is politically prominent;[233] 80% of respondents in a 2009 Home Office poll wanted to cap it.[234] The ONS has projected that the population will grow by nine million between 2014 and 2039.[235]

England contains one indigenous national minority, the Cornish people, recognised by the UK government under the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities in 2014.[236]

Language

| Language | Native speakers

(thousands) [237] |

|---|---|

| English | 46,937 |

| Polish | 529 |

| Punjabi | 272 |

| Urdu | 266 |

| Bengali | 216 |

| Gujarati | 212 |

| Arabic | 152 |

| French | 145 |

| Portuguese | 131 |

| Welsh | 8 |

| Cornish | 0.6 |

| Other | 2,267 |

| Population | 51,006 |

English, today spoken by hundreds of millions of people around the world, originated in what is now England, where it remains the principal tongue. According to a 2011 census, it is spoken well or very well by 98% of the population.[238] It is an Indo-European language in the Anglo-Frisian branch of the Germanic family.[239] After the Norman conquest, the Old English language, brought to Britain by the Anglo-Saxon settlers, was confined to the lower social classes as Norman French and Latin were used by the aristocracy.

By the 15th century, English was back in fashion among all classes, though much changed; the Middle English form showed many signs of French influence, both in vocabulary and spelling. During the English Renaissance, many words were coined from Latin and Greek origins.[240] Modern English has extended this custom of flexibility when it comes to incorporating words from different languages. Thanks in large part to the British Empire, the English language is the world’s unofficial lingua franca.[241]

English language learning and teaching is an important economic activity, and includes language schooling, tourism spending, and publishing. There is no legislation mandating an official language for England,[242] but English is the only language used for official business. Despite the country’s relatively small size, there are many distinct regional accents, and individuals with particularly strong accents may not be easily understood everywhere in the country.

As well as English, England has two other indigenous languages, Cornish and Welsh. Cornish died out as a community language in the 18th century but is being revived,[243] and is now protected under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[244] It is spoken by 0.1% of people in Cornwall,[245] and is taught to some degree in several primary and secondary schools.[246]

When the modern border between Wales and England was established by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542, many Welsh-speaking communities found themselves on the English side of the border. Welsh was spoken in Archenfield in Herefordshire into the nineteenth century,[247] and by natives of parts of western Shropshire until the middle of the twentieth century if not later.[248]

State schools teach students a second language or third language from the ages of seven, most commonly French, Spanish or German.[249] It was reported in 2007 that around 800,000 school students spoke a foreign language at home as a result of immigration among their family,[230] the most common languages being Punjabi and Urdu. However, following the 2011 census data released by the Office for National Statistics, figures now show that Polish is the main language spoken in England after English.[250]

Religion

In the 2011 census, 59.4% of the population of England specified their religion as Christian, 24.7% answered that they had no religion, 5% specified that they were Muslim, while 3.7% of the population belongs to other religions and 7.2% did not give an answer.[251] Christianity is the most widely practised religion in England, as it has been since the Early Middle Ages, although it was first introduced much earlier in Gaelic and Roman times. This Celtic Church was gradually joined to the Catholic hierarchy following the 6th-century Gregorian mission to Kent led by St Augustine. The established church of England is the Church of England,[252] which left communion with Rome in the 1530s when Henry VIII was unable to annul his marriage to the aunt of the king of Spain. The church regards itself as both Catholic and Protestant.[253]

There are High Church and Low Church traditions and some Anglicans regard themselves as Anglo-Catholics, following the Tractarian movement. The monarch of the United Kingdom is the supreme governor of the Church of England, which has around 26 million baptised members (of whom the vast majority are not regular churchgoers). It forms part of the Anglican Communion with the Archbishop of Canterbury acting as its symbolic worldwide head.[254] Many cathedrals and parish churches are historic buildings of significant architectural importance, such as Westminster Abbey, York Minster, Durham Cathedral, and Salisbury Cathedral.

The 2nd-largest Christian practice is the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church. Since its reintroduction after the Catholic Emancipation, the Church has organised ecclesiastically on an England and Wales basis where there are 4.5 million members (most of whom are English).[255] There has been one Pope from England to date, Adrian IV; while saints Bede and Anselm are regarded as Doctors of the Church.

A form of Protestantism known as Methodism is the third largest Christian practice and grew out of Anglicanism through John Wesley.[256] It gained popularity in the mill towns of Lancashire and Yorkshire, and amongst tin miners in Cornwall.[257] There are other non-conformist minorities, such as Baptists, Quakers, Congregationalists, Unitarians and The Salvation Army.[258]

The patron saint of England is Saint George; his symbolic cross is included in the flag of England, as well as in the Union Flag as part of a combination.[259] There are many other English and associated saints; some of the best-known are: Cuthbert, Edmund, Alban, Wilfrid, Aidan, Edward the Confessor, John Fisher, Thomas More, Petroc, Piran, Margaret Clitherow and Thomas Becket. There are non-Christian religions practised. Jews have a history of a small minority on the island since 1070.[260] They were expelled from England in 1290 following the Edict of Expulsion, only to be allowed back in 1656.[260]

Especially since the 1950s, religions from the former British colonies have grown in numbers, due to immigration. Islam is the most common of these, now accounting for around 5% of the population in England.[261] Hinduism, Sikhism and Buddhism are next in number, adding up to 2.8% combined,[261] introduced from India and South East Asia.[261]

A small minority of the population practise ancient Pagan religions. Neopaganism in the United Kingdom is primarily represented by Wicca and Witchcraft religions, Druidry, and Heathenry. According to the 2011 UK Census, there are roughly 53,172 people who identify as Pagan in England,[d] and 3,448 in Wales,[d] including 11,026 Wiccans in England and 740 in Wales.[e]

24.7% of people in England declared no religion in 2011, compared with 14.6% in 2001. These figures are slightly lower than the combined figures for England and Wales as Wales has a higher level of irreligion than England.[262] Norwich had the highest such proportion at 42.5%, followed closely by Brighton and Hove at 42.4%.

Education

Primary education

The Department for Education is the government department responsible for issues affecting people in England up to the age of 19, including education.[263] State-run and state-funded schools are attended by approximately 93% of English schoolchildren.[264] Education is the responsibility of the Secretary of State for Education.[265]

Children who are between the ages of 3 and 5 attend nursery or an Early Years Foundation Stage reception unit within a primary school. Children between the ages of 5 and 11 attend primary school, and secondary school is attended by those aged between 11 and 16. State-funded schools are obliged by law to teach the National Curriculum; basic areas of learning include English literature, English language, mathematics, science, art & design, citizenship, history, geography, religious education, design & technology, computing, ancient & modern languages, music, and physical education.[266]

More than 90% of English schools require students to wear uniforms.[267] School uniforms are defined by individual schools, within the constraint that uniform regulations must not discriminate on the grounds of sex, race, disability, sexual orientation, gender reassignment, religion or belief. Schools may choose to permit trousers for girls or religious dress.[268]

The Programme for International Student Assessment coordinated by the OECD currently ranks the overall knowledge and skills of British 15-year-olds as 13th in the world in reading literacy, mathematics, and science with the average British student scoring 503.7, compared with the OECD average of 493, ahead of the United States and most of Europe.[269]

Although most English secondary schools are comprehensive, there are selective intake grammar schools to which entrance is subject to passing the eleven-plus exam. Around 7.2 per cent of English schoolchildren attend private schools, which are funded by private sources.[270] Standards in state schools are monitored by the Office for Standards in Education, and in private schools by the Independent Schools Inspectorate.[271]

After finishing compulsory education, students take GCSE examinations. Students may then opt to continue into further education for two years. Further education colleges (particularly sixth form colleges) often form part of a secondary school site. A-level examinations are sat by a large number of further education students, and often form the basis of an application to university. Further education (FE) covers a wide curriculum of study and apprenticeships, including T-levels, BTEC, NVQ and others. Tertiary colleges provide both academic and vocational courses.[272]

Higher education

Higher education students normally attend university from age 18 onwards, where they study for an academic degree. There are over 90 universities in England, all but one of which are public institutions. The Department for Business, Innovation and Skills is the government department responsible for higher education in England.[273] Students are generally entitled to student loans to cover the cost of tuition fees and living costs.[f] The first degree offered to undergraduates is the bachelor’s degree, which usually takes three years to complete. Students are then able to work towards a postgraduate degree, which usually takes one year, or towards a doctorate, which takes three or more years.[274]

England’s universities include some of the highest-ranked universities in the world. As of 2023, four England-based universities, the University of Cambridge, University of Oxford, Imperial College London, and University College London, are each ranked among the top ten universities in the world in the 2023 QS World University Rankings. The University of Cambridge, founded in 1209, and the University of Oxford, founded in 1096, are the two oldest universities in the English-speaking world.[275]

The London School of Economics has been described as the world’s leading social science institution for both teaching and research.[276] The London Business School is considered one of the world’s leading business schools and in 2010 its MBA programme was ranked best in the world by the Financial Times.[277] Academic degrees in England are usually split into classes: first class (1st), upper second class (2:1), lower second class (2:2), third (3rd), and unclassified.[274]

The King’s School, Canterbury and King’s School, Rochester are the oldest schools in the English-speaking world.[278] Many of England’s most well-known schools, such as Winchester College, Eton, St Paul’s School, Harrow School and Rugby School are fee-paying institutions.[279]

Culture

Architecture

Many ancient standing stone monuments were erected during the prehistoric period; amongst the best known are Stonehenge, Devil’s Arrows, Rudston Monolith and Castlerigg.[280] With the introduction of Ancient Roman architecture there was a development of basilicas, baths, amphitheaters, triumphal arches, villas, Roman temples, Roman roads, Roman forts, stockades and aqueducts.[281] It was the Romans who founded the first cities and towns such as London, Bath, York, Chester and St Albans. Perhaps the best-known example is Hadrian’s Wall stretching right across northern England.[281] Another well-preserved example is the Roman Baths at Bath, Somerset.[281]

Early Medieval architecture’s secular buildings were simple constructions mainly using timber with thatch for roofing. Ecclesiastical architecture ranged from a synthesis of Hiberno–Saxon monasticism,[282][283] to Early Christian basilica and architecture characterised by pilaster-strips, blank arcading, baluster shafts and triangular headed openings. After the Norman conquest in 1066 various castles in England were created so law lords could uphold their authority and in the north to protect from invasion. Some of the best-known medieval castles are the Tower of London, Warwick Castle, Durham Castle and Windsor Castle.[284]

Throughout the Plantagenet era, an English Gothic architecture flourished, with prime examples including the medieval cathedrals such as Canterbury Cathedral, Westminster Abbey and York Minster.[284] Expanding on the Norman base there was also castles, palaces, great houses, universities and parish churches. Medieval architecture was completed with the 16th-century Tudor style; the four-centred arch, now known as the Tudor arch, was a defining feature as were wattle and daub houses domestically. In the aftermath of the Renaissance a form of architecture echoing classical antiquity synthesised with Christianity appeared, the English Baroque style of architect Christopher Wren being particularly championed.[285]

Georgian architecture followed in a more refined style, evoking a simple Palladian form; the Royal Crescent at Bath is one of the best examples of this. With the emergence of romanticism during Victorian period, a Gothic Revival was launched. In addition to this, around the same time the Industrial Revolution paved the way for buildings such as The Crystal Palace. Since the 1930s various modernist forms have appeared whose reception is often controversial, though traditionalist resistance movements continue with support in influential places.[g]

Gardens