The volumes of the 15th edition of Encyclopædia Britannica (and the volume for the year 2002) span two bookshelves in a library.

Title page of Lucubrationes, 1541 edition, one of the first books to use a variant of the word encyclopedia in the title

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline.[1][2] Encyclopedias are divided into articles or entries that are arranged alphabetically by article name[3] or by thematic categories, or else are hyperlinked and searchable.[4] Encyclopedia entries are longer and more detailed than those in most dictionaries.[3][5] Generally speaking, encyclopedia articles focus on factual information concerning the subject named in the article’s title;[5] this is unlike dictionary entries, which focus on linguistic information about words, such as their etymology, meaning, pronunciation, use, and grammatical forms.[5][6][7][8][9]

Encyclopedias have existed for around 2,000 years and have evolved considerably during that time as regards language (written in a major international or a vernacular language), size (few or many volumes), intent (presentation of a global or a limited range of knowledge), cultural perspective (authoritative, ideological, didactic, utilitarian), authorship (qualifications, style), readership (education level, background, interests, capabilities), and the technologies available for their production and distribution (hand-written manuscripts, small or large print runs, Internet). As a valued source of reliable information compiled by experts, printed versions found a prominent place in libraries, schools and other educational institutions.

The appearance of digital and open-source versions in the 21st century, such as Wikipedia, has vastly expanded the accessibility, authorship, readership, and variety of encyclopedia entries.[10]

Etymology

Indeed, the purpose of an encyclopedia is to collect knowledge disseminated around the globe; to set forth its general system to the men with whom we live, and transmit it to those who will come after us, so that the work of preceding centuries will not become useless to the centuries to come; and so that our offspring, becoming better instructed, will at the same time become more virtuous and happy, and that we should not die without having rendered a service to the human race in the future years to come.

Diderot[11]

The word encyclopedia (encyclo|pedia) comes from the Koine Greek ἐγκύκλιος παιδεία,[12] transliterated enkyklios paideia, meaning ‘general education’ from enkyklios (ἐγκύκλιος), meaning ‘circular, recurrent, required regularly, general’[5][13] and paideia (παιδεία), meaning ‘education, rearing of a child’; together, the phrase literally translates as ‘complete instruction’ or ‘complete knowledge’.[14] However, the two separate words were reduced to a single word due to a scribal error[15] by copyists of a Latin manuscript edition of Quintillian in 1470.[16] The copyists took this phrase to be a single Greek word, enkyklopaedia, with the same meaning, and this spurious Greek word became the New Latin word encyclopaedia, which in turn came into English. Because of this compounded word, fifteenth-century readers and since have often, and incorrectly, thought that the Roman authors Quintillian and Pliny described an ancient genre.[17]

Characteristics

The modern encyclopedia was developed from the dictionary in the 18th century. Historically, both encyclopedias and dictionaries have been researched and written by well-educated, well-informed content experts, but they are significantly different in structure. A dictionary is a linguistic work which primarily focuses on alphabetical listing of words and their definitions. Synonymous words and those related by the subject matter are to be found scattered around the dictionary, giving no obvious place for in-depth treatment. Thus, a dictionary typically provides limited information, analysis or background for the word defined. While it may offer a definition, it may leave the reader lacking in understanding the meaning, significance or limitations of a term, and how the term relates to a broader field of knowledge.

To address those needs, an encyclopedia article is typically not limited to simple definitions, and is not limited to defining an individual word, but provides a more extensive meaning for a subject or discipline. In addition to defining and listing synonymous terms for the topic, the article is able to treat the topic’s more extensive meaning in more depth and convey the most relevant accumulated knowledge on that subject. An encyclopedia article also often includes many maps and illustrations, as well as bibliography and statistics.[5] An encyclopedia is, theoretically, not written in order to convince, although one of its goals is indeed to convince its reader of its own veracity.

Four major elements

There are four major elements that define an encyclopedia: its subject matter, its scope, its method of organization, and its method of production:

- Encyclopedias can be general, containing articles on topics in every field (the English-language Encyclopædia Britannica and German Brockhaus are well-known examples).[2] General encyclopedias may contain guides on how to do a variety of things, as well as embedded dictionaries and gazetteers.[citation needed] There are also encyclopedias that cover a wide variety of topics from a particular cultural, ethnic, or national perspective, such as the Great Soviet Encyclopedia or Encyclopaedia Judaica.

- Works of encyclopedic scope aim to convey the important accumulated knowledge for their subject domain, such as an encyclopedia of medicine, philosophy or law. Works vary in the breadth of material and the depth of discussion, depending on the target audience.

- Some systematic method of organization is essential to making an encyclopedia usable for reference. There have historically been two main methods of organizing printed encyclopedias: the alphabetical method (consisting of a number of separate articles, organized in alphabetical order) and organization by hierarchical categories.[4] The former method is today the more common, especially for general works. The fluidity of electronic media, however, allows new possibilities for multiple methods of organization of the same content. Further, electronic media offer new capabilities for search, indexing and cross reference. The epigraph from Horace on the title page of the 18th century Encyclopédie suggests the importance of the structure of an encyclopedia: «What grace may be added to commonplace matters by the power of order and connection.»

- As modern multimedia and the information age have evolved, new methods have emerged for the collection, verification, summation, and presentation of information of all kinds. Projects such as Everything2, Encarta, h2g2, and Wikipedia are examples of new forms of the encyclopedia as information retrieval becomes simpler. The method of production for an encyclopedia historically has been supported in both for-profit and non-profit contexts, such was the case of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia mentioned above which was entirely state sponsored, while the Britannica was supported as a for-profit institution.

Encyclopedic dictionaries

Some works entitled «dictionaries» are actually similar to encyclopedias, especially those concerned with a particular field (such as the Dictionary of the Middle Ages, the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, and Black’s Law Dictionary). The Macquarie Dictionary, Australia’s national dictionary, became an encyclopedic dictionary after its first edition in recognition of the use of proper nouns in common communication, and the words derived from such proper nouns.

Differences between encyclopedias and dictionaries

There are some broad differences between encyclopedias and dictionaries. Most noticeably, encyclopedia articles are longer, fuller and more thorough than entries in most general-purpose dictionaries.[3][18] There are differences in content as well. Generally speaking, dictionaries provide linguistic information about words themselves, while encyclopedias focus more on the things for which those words stand.[6][7][8][9] Thus, while dictionary entries are inextricably fixed to the word described, encyclopedia articles can be given a different entry name. As such, dictionary entries are not fully translatable into other languages, but encyclopedia articles can be.[6]

In practice, however, the distinction is not concrete, as there is no clear-cut difference between factual, «encyclopedic» information and linguistic information such as appears in dictionaries.[8][18][19] Thus encyclopedias may contain material that is also found in dictionaries, and vice versa.[19] In particular, dictionary entries often contain factual information about the thing named by the word.[18][19]

Pre-modern encyclopedias

Naturalis Historiæ, 1669 edition, title page

The earliest encyclopedic work to have survived to modern times is the Naturalis Historia of Pliny the Elder, a Roman statesman living in the 1st century AD.[5][20][21][22] He compiled a work of 37 chapters covering natural history, architecture, medicine, geography, geology, and all aspects of the world around him.[22] This work became very popular in Antiquity, was one of the first classical manuscripts to be printed in 1470, and has remained popular ever since as a source of information on the Roman world, and especially Roman art, Roman technology and Roman engineering.

Isidore of Seville author of Etymologiae (10th. century Ottonian manuscript)

The Spanish scholar Isidore of Seville was the first Christian writer to try to compile a summa of universal knowledge, the Etymologiae (c. 600–625), also known by classicists as the Origines (abbreviated Orig.). This encyclopedia—the first such Christian epitome—formed a huge compilation of 448 chapters in 20 books[23] based on hundreds of classical sources, including the Naturalis Historia. Of the Etymologiae in its time it was said quaecunque fere sciri debentur, «practically everything that it is necessary to know».[24][21] Among the areas covered were: grammar, rhetoric, mathematics, geometry, music, astronomy, medicine, law, the Catholic Church and heretical sects, pagan philosophers, languages, cities, animals and birds, the physical world, geography, public buildings, roads, metals, rocks, agriculture, ships, clothes, food, and tools.

Another Christian encyclopedia was the Institutiones divinarum et saecularium litterarum of Cassiodorus (543-560) dedicated to the Christian divinity and to the seven liberal arts.[21][5] The encyclopedia of Suda, a massive 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia, had 30,000 entries, many drawing from ancient sources that have since been lost, and often derived from medieval Christian compilers. The text was arranged alphabetically with some slight deviations from common vowel order and place in the Greek alphabet.[21]

From India, the Siribhoovalaya (Kannada: ಸಿರಿಭೂವಲಯ), dated between 800 A.D. to 15th century, is a work of kannada literature written by Kumudendu Muni, a Jain monk. It is unique because rather than employing alphabets, it is composed entirely in Kannada numerals. Many philosophies which existed in the Jain classics are eloquently and skillfully interpreted in the work.

The enormous encyclopedic work in China of the Four Great Books of Song, compiled by the 11th century during the early Song dynasty (960–1279), was a massive literary undertaking for the time. The last encyclopedia of the four, the Prime Tortoise of the Record Bureau, amounted to 9.4 million Chinese characters in 1,000 written volumes.

There were many great encyclopedists throughout Chinese history, including the scientist and statesman Shen Kuo (1031–1095) with his Dream Pool Essays of 1088; the statesman, inventor, and agronomist Wang Zhen (active 1290–1333) with his Nong Shu of 1313; and Song Yingxing (1587–1666) with his Tiangong Kaiwu. Song Yingxing was termed the «Diderot of China» by British historian Joseph Needham.[25]

Printed encyclopedias

Before the advent of the printing press, encyclopedic works were all hand copied and thus rarely available, beyond wealthy patrons or monastic men of learning: they were expensive, and usually written for those extending knowledge rather than those using it.

During the Renaissance, the creation of printing allowed a wider diffusion of encyclopedias and every scholar could have his or her own copy. The De expetendis et fugiendis rebus by Giorgio Valla was posthumously printed in 1501 by Aldo Manuzio in Venice. This work followed the traditional scheme of liberal arts. However, Valla added the translation of ancient Greek works on mathematics (firstly by Archimedes), newly discovered and translated. The Margarita Philosophica by Gregor Reisch, printed in 1503, was a complete encyclopedia explaining the seven liberal arts.

Financial, commercial, legal, and intellectual factors changed the size of encyclopedias. Middle classes had more time to read and encyclopedias helped them to learn more. Publishers wanted to increase their output so some countries like Germany started selling books missing alphabetical sections, to publish faster. Also, publishers could not afford all the resources by themselves, so multiple publishers would come together with their resources to create better encyclopedias. Later, rivalry grew, causing copyright to occur due to weak underdeveloped laws.

John Harris is often credited with introducing the now-familiar alphabetic format in 1704 with his English Lexicon Technicum: Or, A Universal English Dictionary of Arts and Sciences: Explaining not only the Terms of Art, but the Arts Themselves – to give its full title. Organized alphabetically, its content does indeed contain explanation not merely of the terms used in the arts and sciences, but of the arts and sciences themselves. Sir Isaac Newton contributed his only published work on chemistry to the second volume of 1710.

Encyclopédie

Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (English: Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts),[26] better known as Encyclopédie, was a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations. It had many writers, known as the Encyclopédistes. It was edited by Denis Diderot and, until 1759, co-edited by Jean le Rond d’Alembert.[27]

The Encyclopédie is most famous for representing the thought of the Enlightenment. According to Denis Diderot in the article «Encyclopédie», the Encyclopédies aim was «to change the way people think» and for people (bourgeoisie) to be able to inform themselves and to know things.[28] He and the other contributors advocated for the secularization of learning away from the Jesuits.[29] Diderot wanted to incorporate all of the world’s knowledge into the Encyclopédie and hoped that the text could disseminate all this information to the public and future generations.[30] Thus, it is an example of democratization of knowledge.

It was also the first encyclopedia to include contributions from many named contributors, and it was the first general encyclopedia to describe the mechanical arts. In the first publication, seventeen folio volumes were accompanied by detailed engravings. Later volumes were published without the engravings, in order to better reach a wide audience within Europe.[31][32]

Encyclopædia Britannica

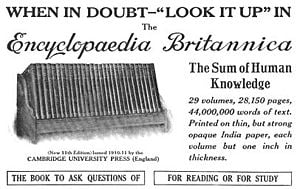

The Encyclopædia Britannica (Latin for «British Encyclopædia») is a general knowledge English-language encyclopædia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various times through the centuries. The encyclopaedia is maintained by about 100 full-time editors and more than 4,000 contributors. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, which spans 32 volumes[33] and 32,640 pages, was the last printed edition. Since 2016, it has been published exclusively as an online encyclopaedia.

Printed for 244 years, the Britannica was the longest running in-print encyclopaedia in the English language. It was first published between 1768 and 1771 in the Scottish capital of Edinburgh, as three volumes. The encyclopaedia grew in size: the second edition was 10 volumes,[34] and by its fourth edition (1801–1810) it had expanded to 20 volumes.[35] Its rising stature as a scholarly work helped recruit eminent contributors, and the 9th (1875–1889) and 11th editions (1911) are landmark encyclopaedias for scholarship and literary style. Starting with the 11th edition and following its acquisition by an American firm, the Britannica shortened and simplified articles to broaden its appeal to the North American market. In 1933, the Britannica became the first encyclopaedia to adopt «continuous revision», in which the encyclopaedia is continually reprinted, with every article updated on a schedule.[citation needed] In March 2012, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. announced it would no longer publish printed editions and would focus instead on the online version.[36]

The 15th edition has a three-part structure: a 12-volume Micropædia of short articles (generally fewer than 750 words), a 17-volume Macropædia of long articles (two to 310 pages), and a single Propædia volume to give a hierarchical outline of knowledge. The Micropædia was meant for quick fact-checking and as a guide to the Macropædia; readers are advised to study the Propædia outline to understand a subject’s context and to find more detailed articles. Over 70 years, the size of the Britannica has remained steady, with about 40 million words on half a million topics. Though published in the United States since 1901, the Britannica has for the most part maintained British English spelling.

Brockhaus Enzyklopädie

The Brockhaus Enzyklopädie (German for Brockhaus Encyclopedia) is a German-language encyclopedia which until 2009 was published by the F. A. Brockhaus printing house.

The first edition originated in the Conversations-Lexikon published by Löbel and Franke in Leipzig 1796–1808. Renamed Der Große Brockhaus in 1928 and Brockhaus Enzyklopädie from 1966, the current 21st thirty-volume edition contains about 300,000 entries on about 24,000 pages, with about 40,000 maps, graphics and tables. It is the largest German-language printed encyclopedia in the 21st century.

In February 2008, F. A. Brockhaus announced the changeover to an online encyclopedia and the discontinuation of the printed editions. The rights to the Brockhaus trademark were purchased by Arvato services, a subsidiary of the Bertelsmann media group. After more than 200 years, the distribution of the Brockhaus encyclopedia ceased completely in 2014.

Encyclopedias in the US

In the United States, the 1950s and 1960s saw the introduction of several large popular encyclopedias, often sold on installment plans. The best known of these were World Book and Funk and Wagnalls. As many as 90% were sold door to door.[20] Jack Lynch says in his book You Could Look It Up that encyclopedia salespeople were so common that they became the butt of jokes. He describes their sales pitch saying, «They were selling not books but a lifestyle, a future, a promise of social mobility.» A 1961 World Book ad said, «You are holding your family’s future in your hands right now,» while showing a feminine hand holding an order form.[37]

Digital encyclopedias

Physical media

By the late 20th century, encyclopedias were being published on CD-ROMs for use with personal computers. This was the usual way computer users accessed encyclopedic knowledge from the 1980s and 1990s. Later DVD discs replaced CD-ROMs and from mid-2000s internet encyclopedias became dominant and replaced disc-based software encyclopedias.[5]

CD-ROM encyclopedias were usually a macOS or Microsoft Windows (3.0, 3.1 or 95/98) application on a CD-ROM disc. The user would execute the encyclopedia’s software program to see a menu that allowed them to start browsing the encyclopedia’s articles, and most encyclopedias also supported a way to search the contents of the encyclopedia. The article text was usually hyperlinked and also included photographs, audio clips (for example in articles about historical speeches or musical instruments), and video clips. In the CD-ROM age the video clips had usually a low resolution, often 160×120 or 320×240 pixels. Such encyclopedias which made use of photos, audio and video were also called multimedia encyclopedias. However, because of the online encyclopedia, CD-ROM encyclopedias have been declared obsolete.[by whom?]

Microsoft’s Encarta, launched in 1993, was a landmark example as it had no printed equivalent. Articles were supplemented with video and audio files as well as numerous high-quality images. After sixteen years, Microsoft discontinued the Encarta line of products in 2009.[38] Other examples of CD-ROM encyclopedia are Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia and Britannica.

Digital encyclopedias enable «Encyclopedia Services» (such as Wikimedia Enterprise) to facilitate programatic access to the content.[39]

Online

Free encyclopedias

«Free encyclopedia» redirects here. For the website that uses the term as its motto, see Wikipedia.

The concept of a free encyclopedia began with the Interpedia proposal on Usenet in 1993, which outlined an Internet-based online encyclopedia to which anyone could submit content and that would be freely accessible. Early projects in this vein included Everything2 and Open Site. In 1999, Richard Stallman proposed the GNUPedia, an online encyclopedia which, similar to the GNU operating system, would be a «generic» resource. The concept was very similar to Interpedia, but more in line with Stallman’s GNU philosophy.

It was not until Nupedia and later Wikipedia that a stable free encyclopedia project was able to be established on the Internet.

The English Wikipedia, which was started in 2001, became the world’s largest encyclopedia in 2004 at the 300,000 article stage.[40] By late 2005, Wikipedia had produced over two million articles in more than 80 languages with content licensed under the copyleft GNU Free Documentation License. As of August 2009, Wikipedia had over 3 million articles in English and well over 10 million combined in over 250 languages. Wikipedia currently has 6,643,597 articles in English.

Since 2003, other free encyclopedias like the Chinese-language Baidu Baike and Hudong, as well as English language encyclopedias such as Citizendium and Knol have appeared, the latter of which has been discontinued.

See also

- Bibliography of encyclopedias

- Biographical dictionary

- Encyclopedic knowledge

- Encyclopedism

- Fictitious entry

- History of science and technology

- Lexicography

- Library science

- Lists of encyclopedias

- Thesaurus

- Speculum literature

Notes

- ^ «Encyclopedia». Archived from the original on August 3, 2007. Glossary of Library Terms. Riverside City College, Digital Library/Learning Resource Center. Retrieved on: November 17, 2007.

- ^ a b «What are Reference Resources?». Eastern Illinois University. Archived from the original on November 22, 2022. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c Hartmann, R. R. K.; James, Gregory (1998). Dictionary of Lexicography. Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-415-14143-7. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ a b «Encyclopedia». Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bocco, Diana (August 30, 2022). «What is an Encyclopedia?». Language Humanities. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ a b c Béjoint, Henri (2000). Modern Lexicography Archived December 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, pp. 30–31. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-829951-6

- ^ a b «Encyclopaedia». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on December 16, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

An English lexicographer, H.W. Fowler, wrote in the preface to the first edition (1911) of The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English language that a dictionary is concerned with the uses of words and phrases and with giving information about the things for which they stand only so far as current use of the words depends upon knowledge of those things. The emphasis in an encyclopedia is much more on the nature of the things for which the words and phrases stand.

- ^ a b c Hartmann, R. R. K.; James, Gregory (1998). Dictionary of Lexicography. Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-415-14143-7. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

In contrast with linguistic information, encyclopedia material is more concerned with the description of objective realities than the words or phrases that refer to them. In practice, however, there is no hard and fast boundary between factual and lexical knowledge.

- ^ a b Cowie, Anthony Paul (2009). The Oxford History of English Lexicography, Volume I. Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-415-14143-7. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

An ‘encyclopedia’ (encyclopaedia) usually gives more information than a dictionary; it explains not only the words but also the things and concepts referred to by the words.

- ^ Hunter, Dan; Lobato, Ramon; Richardson, Megan; Thomas, Julian (2013). Amateur Media: Social, Cultural and Legal Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-78265-4.

- ^ Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert Encyclopédie. Archived April 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine University of Michigan Library:Scholarly Publishing Office and DLXS. Retrieved on: November 17, 2007

- ^ Ἐγκύκλιος παιδεία Archived February 9, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria, 1.10.1, at Perseus Project

- ^ ἐγκύκλιος Archived March 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon, at Perseus Project

- ^ παιδεία Archived March 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon, at Perseus Project

- ^ According to some accounts, such as the American Heritage Dictionary Archived August 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, copyists of Latin manuscripts took this phrase to be a single Greek word, ἐγκυκλοπαιδεία enkyklopaedia.

- ^ Franklin-Brown, Mary (2012). Reading the world: encyclopedic writing in the scholastic age. Chicago London: The University of Chicago Press. p. 8. ISBN 9780226260709.

- ^ König, Jason (2013). Encyclopaedism from antiquity to the Renaissance. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-107-03823-3.

- ^ a b c Hartmann, R. R. K.; James, Gregory (1998). Dictionary of Lexicography. Routledge. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-415-14143-7. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

Usually these two aspects overlap – encyclopedic information being difficult to distinguish from linguistic information – and dictionaries attempt to capture both in the explanation of a meaning …

- ^ a b c Béjoint, Henri (2000). Modern Lexicography. Oxford University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-19-829951-6.

The two types, as we have seen, are not easily differentiated; encyclopedias contain information that is also to be found in dictionaries, and vice versa.

- ^ a b Grossman, Ron (December 7, 2017). «Long before Google, there was the encyclopedia». Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c d «History of Encyclopaedias». Britannica. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c Nobel, Justin (December 9, 2015). «Encyclopedias Are Time Capsules». The Atlantic. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ MacFarlane 1980:4; MacFarlane translates Etymologiae viii.

- ^ Braulio, Elogium of Isidore appended to Isidore’s De viris illustribus, heavily indebted itself to Jerome.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 102.

- ^ Ian Buchanan, A Dictionary of Critical Theory, Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 151.

- ^ «Encyclopédie | French reference work». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^ Denis Diderot as quoted in Hunt, p. 611

- ^ University of the State of New York (1893). Annual Report of the Regents, Volume 106. p. 266.

- ^ Denis Diderot as quoted in Kramnick, p. 17.

- ^ Lyons, M. (2013). Books: a living history. London: Thames & Hudson.

- ^ Robert Audi, Diderot, Denis» entry in The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, (Cambridge University Press, 2015)

- ^ Bosman, Julie (March 13, 2012). «After 244 Years, Encyclopædia Britannica Stops the Presses». The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved March 13, 2012.

- ^ «History of Encyclopædia Britannica and Britannica Online». Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on October 20, 2006. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ «History of Encyclopædia Britannica and Britannica.com». Britannica.com. Archived from the original on June 9, 2001. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Kearney, Christine (March 14, 2012). «Encyclopaedia Britannica: After 244 years in print, only digital copies sold». The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on May 31, 2019. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ Onion, Rebecca (June 3, 2016). «How Two Artists Turn Old Encyclopedias Into Beautiful, Melancholy Art». Slate. Archived from the original on September 23, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Important Notice: MSN Encarta to be Discontinued. MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on October 27, 2009.

- ^ «Encyclopedia Service Are About To Become A Huge Market». www.stillwatercurrent.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ «Wikipedia Passes 300,000 Articles making it the worlds largest encyclopedia» Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Linux Reviews, 2004 Julich y 7.

References

- «encyclopedia | Search Online Etymology Dictionary». www.etymonline.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- «Encyclopaedia». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on December 16, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- Béjoint, Henri (2000). Modern Lexicography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829951-6.

- C. Codoner, S. Louis, M. Paulmier-Foucart, D. Hüe, M. Salvat, A. Llinares, L’Encyclopédisme. Actes du Colloque de Caen, A. Becq (dir.), Paris, 1991.

- Bergenholtz, H.; Nielsen, S.; Tarp, S., eds. (2009). Lexicography at a Crossroads: Dictionaries and Encyclopedias Today, Lexicographical Tools Tomorrow. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-03911-799-4.

- Blom, Phillip (2004). Enlightening the World: Encyclopédie, the Book that Changed the Course of History. New York; Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6895-1. OCLC 57669780.

- Collison, Robert Lewis (1966). Encyclopaedias: Their History Throughout the Ages (2nd ed.). New York, London: Hafner. OCLC 220101699.

- Cowie, Anthony Paul (2009). The Oxford History of English Lexicography, Volume I. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-415-14143-7. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- Darnton, Robert (1979). The business of enlightenment: a publishing history of the Encyclopédie, 1775–1800. Cambridge: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-08785-9.

- Hartmann, R. R. K.; James, Gregory (1998). Dictionary of Lexicography. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-14143-7. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- Kafker, Frank A., ed. (1981). Notable encyclopedias of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: nine predecessors of the Encyclopédie. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation. ISBN 978-0-7294-0256-9. OCLC 10645788.

- Kafker, Frank A., ed. (1994). Notable encyclopedias of the late eighteenth century: eleven successors of the Encyclopédie. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation. ISBN 978-0-7294-0467-9. OCLC 30787125.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). «Part 7, Military Technology; the Gunpowder Epic». Science and Civilization in China. Vol. 5 – Chemistry and Chemical Technology. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3. OCLC 59245877.

- Rosenzweig, Roy (June 2006). «Can History Be Open Source? Wikipedia and the Future of the Past». Journal of American History. 93 (1): 117–46. doi:10.2307/4486062. ISSN 1945-2314. JSTOR 4486062. Archived from the original on April 25, 2010.

- Ioannides, Marinos (2006). The e-volution of information communication technology in cultural heritage: where hi-tech touches the past: risks and challenges for the 21st century. Budapest: Archaeolingua. ISBN 963-8046-73-2. OCLC 218599120.

- Walsh, S. Padraig (1968). Anglo-American general encyclopedias: a historical bibliography, 1703–1967. New York: Bowker. p. 270. OCLC 577541.

- Yeo, Richard R. (2001). Encyclopaedic visions: scientific dictionaries and enlightenment culture. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65191-2. OCLC 45828872. Archived from the original on April 16, 2014. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

External links

- Encyclopaedia and Hypertext

- Internet Accuracy Project – Biographical errors in encyclopedias and almanacs

- Encyclopedia – Diderot’s article on the Encyclopedia from the original Encyclopédie.

- De expetendis et fugiendis rebus – First Renaissance encyclopedia

- Errors and inconsistencies in several printed reference books and encyclopedias Archived July 18, 2001, at the Wayback Machine

- Digital encyclopedias put the world at your fingertips – CNET article

- Encyclopedias online University of Wisconsin – Stout listing by category

- Chambers’ Cyclopaedia, 1728, with the 1753 supplement

- Encyclopædia Americana, 1851, Francis Lieber ed. (Boston: Mussey & Co.) at the University of Michigan Making of America site

- Encyclopædia Britannica, articles and illustrations from 9th ed., 1875–89, and 10th ed., 1902–03.

Texts on Wikisource:

- «Cyclopædia». Collier’s New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- «Encyclopædia». Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- «Encyclopædia». The New Student’s Reference Work. 1914.

- «Encyclopaedia». Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- «Encyclopædia». The Nuttall Encyclopædia. 1907.

- «Encyclopædia». New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- «Cyclopædia». The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions. - Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

Asked by: Brent Hamill

Score: 4.8/5

(11 votes)

An encyclopedia, encyclopædia, or encyclopaedia is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either from all branches or from a particular field or discipline.

What encyclopedia means?

encyclopaedia, also spelled encyclopedia, reference work that contains information on all branches of knowledge or that treats a particular branch of knowledge in a comprehensive manner.

What is the literal meaning of encyclopedia?

The word encyclopedia (encyclo|pedia) comes from the Koine Greek ἐγκύκλιος παιδεία, transliterated enkyklios paideia, meaning ‘general education’ from enkyklios (ἐγκύκλιος), meaning ‘circular, recurrent, required regularly, general’ and paideia (παιδεία), meaning ‘education, rearing of a child’; together, the phrase …

What is an example of an encyclopedia?

The definition of an encyclopedia is defined as a book or an electronic database with general knowledge on a range of topics. The Encyclopedia Britannica is an example of an encyclopedia. A similar work giving information in a particular field of knowledge.

What is another word for encyclopedia?

encyclopedia

- catalog.

- (or catalogue),

- cyclopedia.

- (also cyclopaedia),

- dictionary.

15 related questions found

What is a encyclopedia used for?

Encyclopedias. Encyclopedias attempt to summarise knowledge in relatively short articles. As well as providing basic overviews of topics and answers to simple facts, encyclopedias perform the function of providing context, in other words, identifying where the topic fits in the overall scheme of knowledge.

What are the types of encyclopedia?

There are two types of encyclopedias — general and subject.

- General encyclopedias provide overviews on a wide variety of topics.

- Subject encyclopedias contain entries focusing on one field of study.

Is Wikipedia an encyclopedia?

general and specialized encyclopedias, almanacs, and gazetteers. … Wikipedia is not a dumping ground for random information.

Who created the encyclopedia?

The Encyclopédie, Ou Dictionnaire Raisonné Des Sciences, Des Arts Et Des Métiers, often referred to simply as Encyclopédie or Diderot’s Encyclopedia, is a twenty-eight volume reference book published between 1751 and 1772 by André Le Breton and edited by translator and philosopher Denis Diderot.

What is the difference between Wikipedia and encyclopedia?

Wikipedia is a sea of information that is being contributed by readers present in all parts of the world, and the content on the site is growing by the minute. Encyclopedias are literary works that are definitive and authoritative, which cannot be said about Wikipedia.

What is the difference between dictionary and encyclopedia?

Encyclopedia and Dictionary are two words that are often confused when it comes to their usage and meanings. Encyclopedia is an information bank. On the other hand, a dictionary is a lexicon that contains meanings and possibly, usages of words. This is the main difference between Encyclopedia and dictionary.

What is the meaning of encyclopedia in Tagalog?

Translation for word Encyclopedia in Tagalog is : ensiklopedya.

What is the meaning of encyclopedia knowledge?

To have encyclopedic knowledge is to have «vast and complete» knowledge about a large number of diverse subjects. A person having such knowledge is called a human encyclopedia or a walking encyclopedia.

What is the sentence of encyclopedia?

2. I looked the Civil War up in my encyclopedia. 3. The new encyclopedia runs to several thousand pages.

What was the first encyclopedia?

The earliest encyclopedic work to have survived to modern times is the Naturalis Historia of Pliny the Elder, a Roman statesman living in the 1st century AD. He compiled a work of 37 chapters covering natural history, architecture, medicine, geography, geology, and all aspects of the world around him.

What does Pedia mean in Wikipedia?

an abbreviation of encyclopedia. an abbreviation of pediatrics. Pedia gens, an ancient Roman family. A nickname for Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

What is French encyclopedia?

The Encyclopédie was a literary and philosophical enterprise with profound political, social, and intellectual repercussions in France just prior to the Revolution. Its contributors were called Encyclopédistes.

Does an encyclopedia have an author?

Last Name (Ed.), Name of encyclopedia or dictionary (edition if given and is not first edition). … If a dictionary or encyclopedia entry has no author, the in-text citation should include the title of the entry. The title of the entry should be in quotation marks, with each word starting with a capital letter.

Why was the encyclopedia banned?

Louis XV and Pope Clement XIII both banned the thing, though Louis kept a copy, and apparently actually did read it. Because of political and religious pressure in France, Diderot and his compatriots had to smuggle pages out of the country in order to publish them.

What do you call each book of encyclopedia?

Some are called «encyclopedic dictionaries». All encyclopedias were printed, until the late 20th century when some were on CDs and the Internet. 21st century encyclopedias are mostly online by Internet.

Is a free encyclopedia?

A free encyclopedia, like any other form of free knowledge, can be freely read, without getting permission from anyone. … Free knowledge can be freely shared with others. Free knowledge can be adapted to your own needs.

Is an encyclopedia a journal?

Encyclopedia is an international, peer-reviewed, open access journal recording qualified entries of which contents should be reliable, objective and established knowledge, and it is published quarterly online by MDPI.

What is subject encyclopedia?

A single- or multi-volume encyclopedia which is devoted to a specific subject or field of study. A subject encyclopedia is usually edited by a respected scholar in the subject field. … A subject encyclopedia often makes a good tool for students and general readers who need to get an overview of a specialized topic.

What are the 4 types of Encyclopaedia?

Answer: Encyclopaedias can be approximatelydivided into four types. (1) Dictionaries(2) Comprehensive Encyclopaedia(Vishwakosh) (3) Encyclopaedic(Koshsadrush) literature (4) Indexes. Words are arranged mostly in an alphabetical order.

Funk & Wagnall’s New Standard Encyclopedia (1931) was a small encyclopedia which could be afforded by many households

An encyclopedia, encyclopaedia or (traditionally) encyclopædia,[1] is a comprehensive written compendium that contains information on all branches of knowledge or a particular branch of knowledge.

The word comes from the Classical Greek ἐγκύκλιος παιδεία (pron. enkyklos paideia), literally ‘the things of boys/child in a circle’, meaning «a general knowledge.»

In ancient times encyclopedias were teaching tools for instruction of the aristocracy. They were compiled by teachers and their schools, and they were arranged by subject matter rather than as an alphabetical reference work. In the Middle Ages in the Holy Roman Empire knowledge was largely controlled by the Church and encyclopedias were kept by religious scholars in conformity with church doctrine.

The modern alphabetical encyclopedia evolved in the context of the Enlightenment and the rise of modern science. It is a reference work ordered like an expanded dictionary and is designed to be available to everyone. The first modern type encyclopedia, compiled by teams of scholars, arranged alphabetically, and composing 20-30 volumes, was produced by Denis Diderot in France, with the expressed purpose of disseminating Enlightenment ideas and the new advances in scientific knowledge to a wide audience. In so doing, it effectively undermined the Church’s traditional monopoly on knowledge.

Modern encyclopedias, by making the sum of knowledge available to all citizens, are designed to be tools for democracy. The Encyclopedia Britannica, became the premier standard for encyclopedias in the nineteenth century as it integrated scientific and traditional knowledge. However, it too was charged with cultural bias, and after its eleventh edition, the Britannica began producing a more scientistic collection of facts and data with greatly reduced entries on biography and social sciences. As knowledge has increased exponentially over the last century, modern encyclopedias contained annual updates to attempt to keep their owners current. Modern religious encyclopedias, like the Catholic Encyclopedia (1917) provided some counterbalance to the scientism of the scientific encyclopedias.

The information age led to digital encyclopedias which are not bound by the restrictions of print. They go beyond modern encyclopedias in content, size, and cross-referencing. These digital encyclopedias, produced on CD-ROM and the Internet, have almost entirely superseded print encyclopedias in the twenty-first century. Traditional encyclopedias, like the Encyclopedia Britannica, have survived by creating CD-ROM and Internet versions. However, new forms of encyclopedias, like the popular Wikipedia, have taken advantage of the Internet, which provides wide accessibility and the possibility of harnessing a huge virtual community of volunteer writers and editors to the task of creating and updating articles on every imaginable topic. These online collaborative encyclopedias are frequently charged with lack of quality control, but they have nonetheless rapidly displaced the traditional print encyclopedias because of their accessibility and breadth.

The ongoing issues related to the development of encyclopedias include the proper integration of facts and values and the quality control of the accuracy of vast bodies of information becoming available.

Use of the term Encyclopedia

Though the notion of a compendium of knowledge dates back thousands of years, the term was first used in the title of a book in 1541 by Joachimus Fortius Ringelbergius in the title page of his Lucubrationes vel potius absolutissima kyklopaideia (Basel 1541). It was first used as a noun by the encyclopedist Pavao Skalic in the title of his book Encyclopaedia seu orbis disciplinarum tam sacrarum quam prophanarum epistemon («Encyclopaedia, or Knowledge of the World of Disciplines») (Basel 1559). Several encyclopedias have names that include the term -p(a)edia, e.g., Banglapedia (on matters relevant for Bengal).

Characteristics of an Encyclopedia

The encyclopedia as we recognize it today was developed from the dictionary in the eighteenth century. A dictionary primarily focuses on words and their definition, typically in one sentence. This leave the reader lacking in a comprehensive understanding of the meaning or significance of the term, and how the term relates to a broader field of knowledge.

1913 advertisement for Encyclopædia Britannica, the oldest and one of the largest contemporary English encyclopedias.

To address those needs, an encyclopedia treats each subject in more depth and conveys the most relevant accumulated knowledge on that subject or discipline, given the overall length of the particular work. An encyclopedia also often includes many maps and illustrations, as well as bibliography and statistics. Historically, both encyclopedias and dictionaries have been researched and written by well-educated, well-informed content experts, who have attempted to make them as accurate, concise and readable as possible.

Four major elements define an encyclopedia: its subject matter, its scope, its method of organization, and its method of production.

- Encyclopedias can be general, containing articles on topics in every field (the English-language Encyclopædia Britannica and German Brockhaus are well-known examples). General encyclopedias often contain guides on how to do a variety of things, as well as embedded dictionaries and gazetteers. They can also specialize in a particular field (such as an encyclopedia of medicine, philosophy, or law). There are also encyclopedias that cover a wide variety of topics from a particular cultural, ethnic, or national perspective, such as the Great Soviet Encyclopedia or Encyclopaedia Judaica.

- Works of encyclopedic scope aim to convey the important accumulated knowledge for their subject domain. Such works have been envisioned and attempted throughout much of human history, but the term encyclopedia was first used to refer to such works in the sixteenth century. The first general encyclopedias that succeeded in being both authoritative as well as encyclopedic in scope appeared in the eighteenth century. Every encyclopedic work is, of course, an abridged version of all knowledge, and works vary in the breadth of material and the depth of discussion. The target audience may influence the scope; a children’s encyclopedia will be narrower than one for adults.

Brockhaus Konversations-Lexikon, 1902

- Some systematic method of organization is essential to making an encyclopedia usable as a work of reference. There have historically been two main methods of organizing printed encyclopedias: the alphabetical method (consisting of a number of separate articles, organized in alphabetical order), or organization by hierarchical categories. The former method is today the most common by far, especially for general works. The fluidity of electronic media, however, allows new possibilities for multiple methods of organization of the same content. Further, electronic media offer previously unimaginable capabilities for search, indexing and cross reference. The epigraph from Horace on the title page of the eighteenth-century Encyclopédie suggests the importance of the structure of an encyclopedia: «What grace may be added to commonplace matters by the power of order and connection.»

- As modern multimedia and the information age have evolved, they have had an ever-increasing effect on the collection, verification, summation, and presentation of information of all kinds. Projects such as h2g2 and Wikipedia are examples of new forms of the encyclopedia as information retrieval becomes simpler.

Some works titled «dictionaries» are actually more similar to encyclopedias, especially those concerned with a particular field (such as the Dictionary of the Middle Ages, the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, and Black’s Law Dictionary). The Macquarie Dictionary, Australia’s national dictionary, became an encyclopedic dictionary after its first edition in recognition of the use of proper nouns in common communication, and the words derived from such proper nouns.

History of Encyclopedias

Early encyclopedic works

The idea of collecting all of the world’s knowledge into a single work was an elusive vision for centuries. The earliest encyclopedia may have been compiled by the Greek philosopher Speusippus, who preceded Aristotle. But Aristotle is sometimes called the father of encyclopedias because of his vast collection and categorization of knowledge, most of which remains valid today. The oldest complete encyclopedia in existence was the Historia Naturalis compiled by Pliny the Elder about 79 C.E. It is a 37-volume account of the natural world in 2,493 chapters that was extremely popular in western Europe for over 1,500 years.

The first Christian encyclopedia was Cassiodorus’ Institutiones (560 C.E.) which inspired Saint Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiarum, sive Originum Libri XX (Twenty Books of Etymologies, or Origins) (623) which became the most influential encyclopedia of the Early Middle Ages. The Bibliotheca by the Patriarch Photius (ninth century) was the earliest Byzantine work that could be called an encyclopedia. Bartholomeus de Glanvilla’s De proprietatibus rerum (1240) was the most widely read and quoted encyclopedia in the High Middle Ages while Dominican Friar Vincent of Beauvais’s Speculum Majus (1260) was the most ambitious encyclopedia in the late-medieval period at over three million words.

The early Muslim compilations of knowledge in the Middle Ages included many comprehensive works, and much development of what we now call scientific method, historical method, and citation. Notable works include Abu Bakr al-Razi’s encyclopedia of science, the Mutazilite Al-Kindi’s prolific output of 270 books, and Ibn Sina’s medical encyclopedia, which was a standard reference work for centuries. Also notable are works of universal history (or sociology) from Asharites, al-Tabri, al-Masudi, the Brethren of Sincerity’s Encyclopedia, Ibn Rustah, al-Athir, and Ibn Khaldun, whose Muqadimmah contains cautions regarding trust in written records that remain wholly applicable today. These scholars had an incalculable influence on methods of research and editing, due in part to the Islamic practice of isnad which emphasized fidelity to written record, checking sources, and skeptical inquiry.

The Chinese emperor Yongle of the Ming Dynasty oversaw the compilation of the Yongle Encyclopedia, one of the largest encyclopedias in history, which was completed in 1408 and comprised over 11,000 handwritten volumes, of which only about 400 remain today. In the succeeding dynasty, emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty personally composed 40,000 poems as part of a 4.7 million page library in four divisions, including thousands of essays. It is instructive to compare his title for this knowledge, Watching the waves in a Sacred Sea to a Western-style title for all knowledge. Encyclopedic works, both in imitation of Chinese encyclopedias and as independent works of their own origin, have been known to exist in Japan since the ninth century C.E.

These works were all hand copied and thus rarely available, beyond wealthy patrons or monastic men of learning: they were expensive, and usually written for those extending knowledge rather than those using it (with some exceptions in medicine).

Modern Encyclopedias

The beginnings of the modern idea of the general-purpose, widely distributed printed encyclopedia precede the eighteenth-century encyclopedists. However, Chambers’ Cyclopaedia, or Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, and the Encyclopédie, Encyclopædia Britannica, and the Conversations-Lexikon were the first to realize the form we would recognize today, with a comprehensive scope of topics, discussed in depth and organized in an accessible, systematic method.

The English physician and philosopher Sir Thomas Browne specifically employed the word encyclopaedia as early as 1646 in the preface to the reader to describe his Pseudodoxia Epidemica or Vulgar Errors, a series of refutations of common errors of his age. Browne structured his encyclopaedia upon the time-honored schemata of the Renaissance, the so-called ‘scale of creation’ which ascends a hierarchical ladder via the mineral, vegetable, animal, human, planetary and cosmological worlds. Browne’s compendium went through no less than five editions, each revised and augmented, the last edition appearing in 1672. Pseudodoxia Epidemica found itself upon the bookshelves of many educated European readers for throughout the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries it was translated into the French, Dutch and German languages as well as Latin.

John Harris is often credited with introducing the now-familiar alphabetic format in 1704 with his English Lexicon technicum. Organized alphabetically, it sought to explain not merely the terms used in the arts and sciences, but the arts and sciences themselves. Sir Isaac Newton contributed his only published work on chemistry to the second volume of 1710. Its emphasis was on science and, at about 1200 pages, its scope was more that of an encyclopedic dictionary than a true encyclopedia. Harris himself considered it a dictionary; the work is one of the first technical dictionaries in any language. However, the alphabetical arrangement made encyclopedias ready reference tools in which complete books or chapters did not have to be read to glean knowledge. They became a mainstay of modern general encyclopedias.

Ephraim Chambers published his Cyclopaedia in 1728. It included a broad scope of subjects, used an alphabetic arrangement, relied on many different contributors and included the innovation of cross-referencing other sections within articles. Chambers has been referred to as the father of the modern encyclopedia for this two-volume work.

A French translation of Chambers’ work inspired the Encyclopédie, perhaps the most famous early encyclopedia, notable for its scope, the quality of some contributions, and its political and cultural impact in the years leading up to the French revolution. The Encyclopédie was edited by Jean le Rond d’Alembert and Denis Diderot and published in 17 volumes of articles, issued from 1751 to 1765, and 11 volumes of illustrations, issued from 1762 to 1772. While Diderot did the final editing on all the work itself, this encyclopedia gained its breadth and excellence over the Chambers encyclopedia by employing a team of writers on the social philosophy including Voltaire, Montesquieu, and Rousseau. Five volumes of supplementary material and a two volume index, supervised by other editors, were issued from 1776 to 1780 by Charles Joseph Panckoucke.

Realizing the inherent problems with the model of knowledge he had created, Diderot’s view of his own success in writing the «Encyclopédie» were far from ecstatic. Diderot envisioned the perfect encyclopedia as more than the sum of its parts. In his own article on the encyclopedia[2] Diderot wrote, «Were an analytical dictionary of the sciences and arts nothing more than a methodical combination of their elements, I would still ask whom it behooves to fabricate good elements.» Diderot viewed the ideal encyclopedia as an index of connections. He realized that all knowledge could never be amassed in one work, but he hoped the relations between subjects could. The realization of the dream in becoming more a reality with information age methods of hyper-linking electronic encyclopedias.

The Encyclopédie in turn inspired the venerable Encyclopædia Britannica, which had a modest beginning in Scotland: the first edition, issued between 1768 and 1771, had just three hastily completed volumes—A-B, C-L, and M-Z—with a total of 2,391 pages. By 1797, when the third edition was completed, it had been expanded to 18 volumes addressing a full range of topics, with articles contributed by a range of authorities on their subjects.

The Conversations-Lexikon was published in Leipzig from 1796 to 1808, in six volumes. Paralleling other eighteenth century encyclopedias, the scope was expanded beyond that of earlier publications, in an effort to become comprehensive. But the work was intended not for scientific use, but to give the results of research and discovery in a simple and popular form without extended details. This format, a contrast to the Encyclopædia Britannica, was widely imitated by later nineteenth century encyclopedias in Britain, the United States, France, Spain, Italy, and other countries. Of the influential late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century encyclopedias, the Conversations-Lexikon is perhaps most similar in form to today’s encyclopedias.

The early years of the nineteenth century saw a flowering of encyclopedia publishing in the United Kingdom, Europe, and America. In England Rees’s Cyclopaedia (1802–1819) contains an enormous amount in information about the industrial and scientific revolutions of the time. A feature of these publications is the high-quality illustrations made by engravers like Wilson Lowry of art work supplied by specialist draftsmen like John Farey, Jr. Encyclopaedias were published in Scotland, as a result of the Scottish Enlightenment, for education there was of a higher standard than in the rest of the United Kingdom.

The 17-volume Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle and its supplements were published in France from 1866 to 1890.

Encyclopædia Britannica appeared in various editions throughout the century, and the growth of popular education and the Mechanics Institutes, spearheaded by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge led to the production of the Penny Cyclopaedia, as its title suggests issued in weekly numbers at a penny each like a newspaper.

In the early twentieth century, the Encyclopædia Britannica reached its eleventh edition (considered by many the zenith of modern print encyclopedias), and inexpensive encyclopedias such as Harmsworth’s Encyclopaedia and Everyman’s Encyclopaedia were common.

In the United States, the 1950s and 1960s saw the rise of several large popular encyclopedias, often sold on installment plans. The best known of these were World Book and Funk and Wagnalls.

The second half of the twentieth century also saw the publication of several encyclopedias that were notable for synthesizing important topics in specific fields, often by means of new works authored by significant researchers. Such encyclopedias included The Encyclopedia of Philosophy (first published in 1967 and now in its second edition), and Elsevier’s Handbooks In Economics[3] series. Encyclopedias of at least one volume in size exist for most if not all Academic disciplines, including, typically, such narrow topics such as bioethics and African American history.

Information Age Encyclopedias

By the late twentieth century, the information age was beginning to stimulate an entirely new generation of encyclopedias based on digital, electronic, and computer technology. Initially, traditional encyclopedia makers began offering electronics forms of their encyclopedias on CD-ROMs for use with personal computers. Microsoft’s Encarta was a landmark in this sea change, as it had no print version. Articles were supplemented with video and audio files as well as numerous high-quality images. The development of hyperlinking greatly aided cross referencing, making quick transitions from one subject to the next. In addition, nearly instantaneous searches of thousands of articles, using keyword technology, are possible.

With the development of the Internet, similar encyclopedias were also being published online, and made available by subscription. Most libraries stopped buying print encyclopedias at this point, because the online encyclopedias were constantly revised, making the cumbersome and expensive purchase of annual additions and new editions obsolete.

Traditional encyclopedias are written by a number of employed text writers, usually people with an academic degree, but the interactive nature of the Internet allowed for the creation of collaborative projects such as Nupedia, Everything2, Open Site, and Wikipedia, some of which allowed anyone to add or improve content. Wikipedia, begun as an on-line collaborative free encyclopedia with wiki software was begun in 2001 and already had more than two million articles in more than 80 languages with content licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License by 2005. However Wikipedia’s articles are not necessarily peer reviewed and many of those articles may be considered to be of a trivial nature. Wikipedia co-founder Larry Sanger stated that the neutral policy is «dead» due to left-wing bias being imposed by activists on the site.[4] Concerns have been raised as to the accuracy of information generated through open source projects generally. The New World Encyclopedia attempts to improve on this quality control weakness by offering more specialized and supervised on-line collaboration.

Knowledge and Values

It is often said that «knowledge is power» or «those who control education control the future.» Before the invention of the printing press, and the development of primary schools to educate masses, knowledge remained in the hands of the aristocracy and the churches. Only the wealthy families were able to afford tutors like Aristotle.

Throughout history, people have sought to control others by enforcing official thought and punishing heresy. The destruction of the great ancient Alexandria Library, the canonization of the Bible in the fourth century C.E., the genocide against the Cathars and Albigenses of Southern France in the thirteenth century, the burning of Jan Hus in Bohemia in 1415, Savonarola’s «Bonfire of the Vanities’ (destruction of works of art) in Florence in 1497, in Michael Servetus’ execution for a «false view of the Trinity» in Geneva in 1553, the banishment of Roger Williams from Massachussetts in 1635, the Catholic ban on Copernicus’ theory of a heliocentric universe in 1757, the elimination of sociology from the University of Moscow in 1923 with the pronouncement that «Marxism-Leninism had said the final word on the subject, and the Taliban ban on education of women and their obliteration of great Buddhist works of art at the end of the twentieth, are only a few of the notorious examples of repression of knowledge. Millions of people have been killed in the effort by oppressors to control knowledge.

Encyclopedias and education of the masses are attempts to break the yoke of imposed thought control and allow all people the knowledge required to pursue a life of happiness, prosperity and peace on more equal terms. Nevertheless, encyclopedias have been criticized for their own attempts to distort knowledge, just as political groups continue to control the curriculum of public schools in an attempt to shape social consciousness. Enlightenment encyclopedias were accused of promoting Enlightenment values by both traditional religious institutions that were threatened by them, as well as scientists that argued the social philosophy of the encyclopedists was unproven or faulty. The Britannica was accused of imposing the values of British aristocracy.

The reaction to this was the attempt to remove values from encyclopedias in the twentieth century. This created a form of scientism by default. «Value free» encyclopedias failed to help readers organize knowledge for a meaningful purpose, but simply presented collections of facts and data which readers were supposed to figure out how to use by themselves. This value neutrality or relativism led to a generations of people with less ability to make informed judgments, and thus a less productive society.

Contemporary philosophy accepts that value neutrality is neither possible nor desired, however the modern pluralism of cultures makes it difficult to highlight any specific values without criticism. As a result, it is becoming more standard to articulate one’s values at the onset of a written work, thus defining its purpose. This very encyclopedia, the New World Encyclopedia, while associated with a believing community (namely that of Sun Myung Moon), differs from classical religious encyclopedias insofar as it seeks to provide and protect a thoroughly pluriform, multi-religious stance, and to communicate universal values in a scholarly and rigorous manner that does not posit particularistic faith affirmations or other non-universal positions as «fact.» Its stance is based on the premise that there exists universal values, which can be found in the essence of all religions and non-theistic philosophical traditions; these are values that derive from efforts to bring about happiness, prosperity and peace for all.

See also

Other types of Reference works:

- Dictionary

- Thesaurus

Notes

- ↑ Owing to differences in American and British English orthographic conventions, the spellings encyclopedia and encyclopaedia both see common use, in American- and British-influenced sources, respectively. It should however be noted that, as with -ize and -ise, the former is the only accepted form in the U.S. whereas both are accepted in Commonwealth English. Further, converse to archaeology, where the ae spelling is retained all but universally, the «simplified» spelling has become increasingly widespread in recent years. The spelling encyclopædia—with the æ ligature—was frequently used in the nineteenth century and is increasingly rare, although it is retained in product titles such as Encyclopædia Britannica and others. The Oxford English Dictionary and Webster’s Third New International Dictionary record both spellings: the former (1989) notes the æ would be obsolete except that it is preserved in works that have Latin titles, while the latter (1961-2002) notes that the digraph is «rare» in the United States. Similarly, cyclopaedia and cyclopedia are now rarely-used alternate forms of the word originating in the early seventeenth century.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Diderot & D’alembert, Scholarly Publishing Office of the University of Michigan Library. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ↑ Handbooks in Economics Elsevier. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ↑ T.D. Adler, «Wikipedia Co-Founder: Site’s Neutrality Is ‘Dead’ Thanks to Leftist Bias» Breitbart, May 26, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Encyclopedia EtymologyOnline. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- Collison, Robert. Encyclopaedias: Their History Throughout the Ages, 2nd ed. New York, London: Hafner, 1966.

- Darnton, Robert. The business of enlightenment: a publishing history of the Encyclopédie, 1775-1800. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1979. ISBN 0674087852

- «Encyclopedia» in Funk & Wagnalls New Encyclopedia. vol. 9. New York, Rand McNally, 1986. ISBN 0834300729

- Kafker, Frank A. (ed.). Notable encyclopedias of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: nine predecessors of the Encyclopédie. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1981.

- Kafker, Frank A. (ed.). Notable encyclopedias of the late eighteenth century: eleven successors of the Encyclopédie. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1994.

- Moon, Sun Myung. Science and Absolute Values: Twenty Addresses. New York: International Conference on the Unity of the Sciences, 1997. ISBN 089226201X

- Rozenzweig, Roy. «Can History Be Open Source? Wikipedia and the Future of the Past.» Journal of American History 93(1) (June, 2006): 117-146.

- Walsh, S. Padraig. Anglo-American general encyclopedias: a historical bibliography, 1703-1967. New York: Bowker, 1968.

- Yeo, Richard R. Encyclopaedic visions : scientific dictionaries and enlightenment culture. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001. ISBN 0521651913

External links

All links retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Diderot’s article on the Encyclopedia from the original Encyclopédie.

- Encyclopaedia and Hypertext

- Biographical errors in encyclopedias and almanacs Internet Accuracy Project]

- Wikipedia

Historical encyclopedias available online

- Chambers’ Cyclopaedia – 1728, with the 1753 supplement; superbly digitized at the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center. Note the plates at the end of Supplement volume II.

- Encyclopædia Americana – 1851, Francis Lieber ed. (Boston: Mussey & Co.) at the University of Michigan Making of America site

- The Jewish Encyclopedia

- The Catholic Encyclopedia

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Encyclopedia history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Encyclopedia»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

: a work that contains information on all branches of knowledge or treats comprehensively a particular branch of knowledge usually in articles arranged alphabetically often by subject

Example Sentences

Recent Examples on the Web

And so, 10 years later, Sloane published his first encyclopedia, A Handbook of Integer Sequences, which contained about 2,400 sequences that also proved useful in making certain calculations.

—

The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad, an encyclopedia of Black Americans’ contributions to World War II, out Oct. 18.

—

To spice up their evening mocktails, an encyclopedia of recipes might help inspire.

—

On Baidu’s online encyclopedia Baidu Baike, the page about Yan has been taken down.

—

Platform 18 and Undertow offer encyclopedia-sized menus featuring complex concoctions—classics and originals, alike.

—

Prine also criticized MoneyGeek for using the online encyclopedia Wikipedia as one of its sources.

—

Two-hundred-fifty pesos a month, said Ramírez, who hit .297 and won 51 games on the mound in 13 seasons in Mexico, according to the Mexican baseball encyclopedia.

—

Follow, Los Angeles Times, 7 Dec. 2022

Hugging the airy restaurant in Navy Yard are planters stocked with a little encyclopedia of herbs and greens, and a window in the back of the dining room captures hams hung for aging.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘encyclopedia.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Etymology

Medieval Latin encyclopaedia course of general education, from Greek enkyklios + paideia education, child rearing, from paid-, pais child — more at few

First Known Use

1644, in the meaning defined above

Time Traveler

The first known use of encyclopedia was

in 1644

Dictionary Entries Near encyclopedia

Cite this Entry

“Encyclopedia.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/encyclopedia. Accessed 14 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on encyclopedia

Last Updated:

29 Mar 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged