How do you depict the indescribable? Is dreaming the preferred path of the subconscious?

Within the history of art, the dream is a very common theme, particularly the idea of the dream and its meaning in a painting. Mysterious and elusive, paintings surrounding dreams question, disturb and fascinate us all at once. In other words, the dream in art is a wandering spirit on the path of the imagination. It is through this pictorial representation that we are consequently forced to examine the link between the visible and the invisible. Whether it be through a religious or a more psychological perspective, artists who express their dreams through painting lead us to explore subjects that are often left untouched. Artsper invites you to look back through the history of this dreamy phenomenon over five key periods in time.

The Renaissance, a biblical and mythological depiction of dream painting

Today, often perceived as a manifestation of the subconscious and the psyche, dreaming is a theme which has greatly evolved throughout the history of art. Its representation has therefore transformed over time, always expanding somewhat in definition as a result. During the Renaissance era, dreaming was solely presented as a religious experience. That is to say when the soul, at rest, leaves the body and encounters higher beings. Subsequently, dream art in the 15th and 16th centuries does not actually depict the artist’s dream. Instead, it is inspired by religious narratives to depict biblical dreams. A painting of a dream had a specific meaning; it was a way to access the higher realm and divine truth. Therefore the painter of the dream, principally in response to the demands of the Church, depicted religious figures inspired by the New Testament.

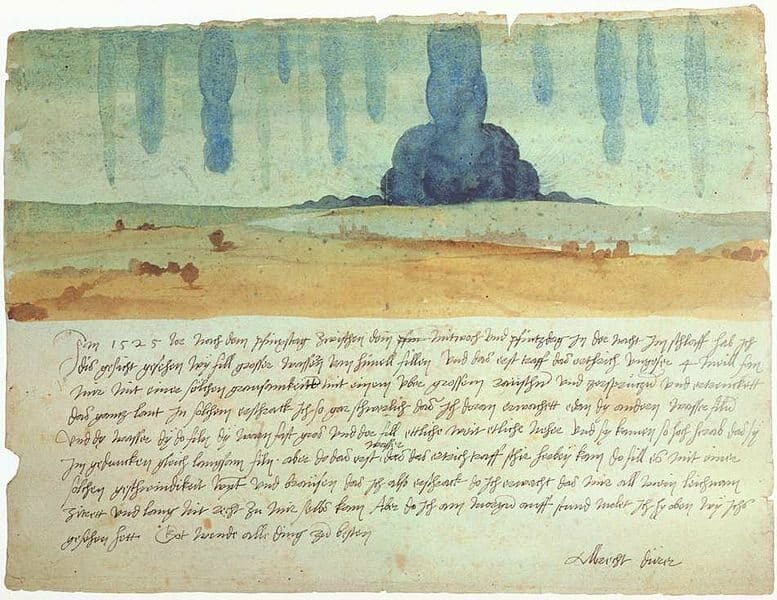

The personal dream only became legitimized much later. Consequently, the first artist to paint a dream of their own was Albrecht Dürer, in his watercolor painting The Vision in 1525.

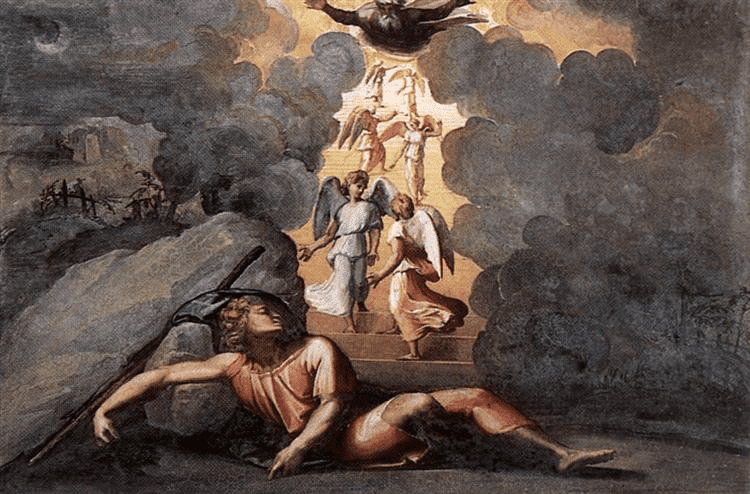

For instance, Raphaël perfectly demonstrates a representation of a religious dream in his painting The Dream of Jacob. The canvas is darkened, but the soul of Jacob, accompanied by angels, is brighter and appears raised into the heavens. Secondly, the staircase effectively symbolises the spirit’s ascension, and the path to achieve transcendence.

Dreams of Romantic artists “recreating the world”

With Romanticism, the 18th century brought about a change to freedom of artistic expression of the personal dream in paintings. During this period, subjectivity became the heart of inspiration for artists, and dreaming an infinite source of inspiration for self exploration! The first German Romantics called dreaming the “Zweite Welt”, or the “second world”. Daydreams were a way for artists to completely leave themselves in order to experience another world.

The Romantics experimented with many substances in order to achieve a dreamlike state. The painter Eugène Delacroix for example participated in the “Club des Haschinschins”. This was a group dedicated to the study and experience of drugs, in which the doctor Moreau de Tour analyzed their dreams and hallucinations. To the Romantics, dreaming was an escape, but also a revelation of what was deep in one’s soul.

A perfect representation of dark dreams can be found in The Nightmare. The piece by the British artist Johann Heinrich Füssli is a dream painting which explores the subject of an odalisque – a nude woman lying down – in order to evoke the torments of the sleeping spirit. The chiaroscuro, the contortion of the body and the phantasmagorical beings unveil the tortured soul of this sleeping woman. As a result, the observer bears witness to this nightmare that Fussli has presented, which exemplifies the most morbid and fantastical elements of dreaming.

It is also through nature that the Romantic artists explored dreams. Associated with solitude, nature allowed them to flee the challenges of society and stimulated their imagination.

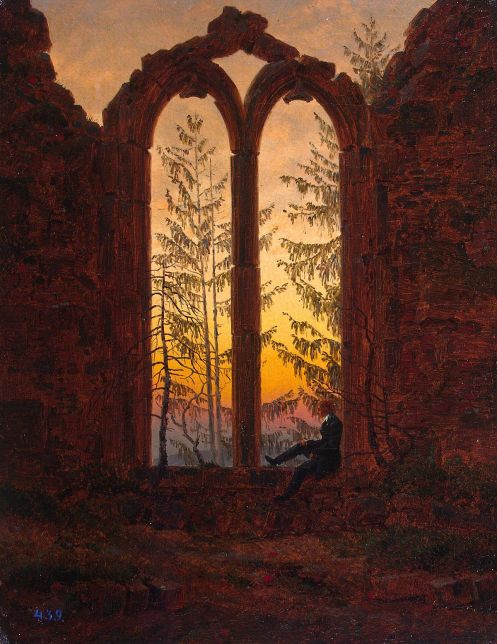

For example, in Der Träumer by Friedrich, a man gazes upon the horizon and appears to be lost in his own world, a type of melancholy daydream.

Symbolism, between the world of dreams and nightmares

In the 19th century, the dream in art was at the heart of the symbolist aesthetic. Estranged from a society involved with scientific ideology, Symbolism aimed to explore the dreams of the invisible and the mysteries of the subconscious. The subjects and objects of Symbolists only acquire meaning through their symbolic representation.

Symbolism was born in reaction to Naturalism and Realism, artistic movements which only depicted tangible and visible things.

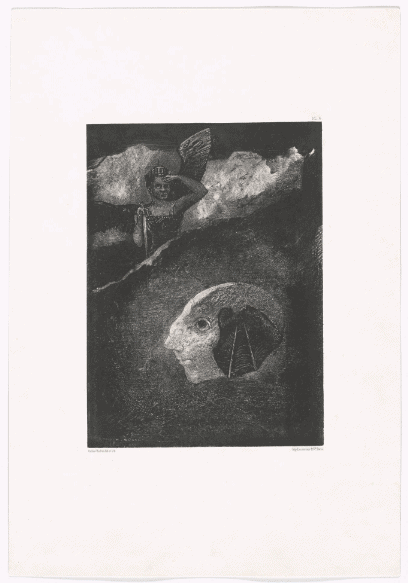

Odilon Redon, nicknamed “king of dreams” by the art critic Thadée Natanson, was a figurehead of Symbolism. An artist, dreamer and poet, he was fascinated by the feeling and the struggles of being human. His artworks are very personal and free. His lithographs, created between 1879 and 1899 and entitled the Noirs, unveil a harrowing world where hybrid figures seem to have come straight out of a nightmare. These include a spider with a human face, a flying eye, horrifying chimeras and even a human flower.

Odilon Redon, La Vision, 1890-1900, and L’Araignée qui pleure, 1881

Starting in 1990, Odilion Redon came out of his dark period and into the light. From thereon his shift to colorful, pastel works marked a new era of serenity. Once again, the artist returned to the subject of dreams. However, it was now more so a sweet dream due to the painting of hazy shapes and surprisingly calm faces.

Odilon Redon, La Cellule d’Or, 1893 and Le Rêve, 1905

Subconscious and dream art in Surrealism

Does dreaming allow us to access absolute reality? This was the question posed by André Breton, a precursor to Surrealism. To him, the very essence of the movement was to reunite the real and the imaginary. The biggest painters of dreams are also Surrealists: Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Max Ernst, Joan Mirò, Paul Klee, Giorgio de Chirico. In each of their Surrealist dream paintings, they convey dreams as an experience halfway between the visible and the invisible.

Man Ray is mainly known for his iconic Surrealist photographs. Despite this, his illustrations for the collection Free Hands in collaboration with Paul Eluard are striking. A dreamlike universe can be found in many of his drawings. as Man Ray stated: “In the morning when I wake up, if I have a dream, I draw it right away. Many of the drawings in Free Hands are dream drawings. »

In The Broken Bridge, the legs of the naked, elongated woman are bent, like an extension of the destroyed bridge. Her dreamy face and long hair are reflected in the water of the Rhone, feeding the imagination of the spectator.

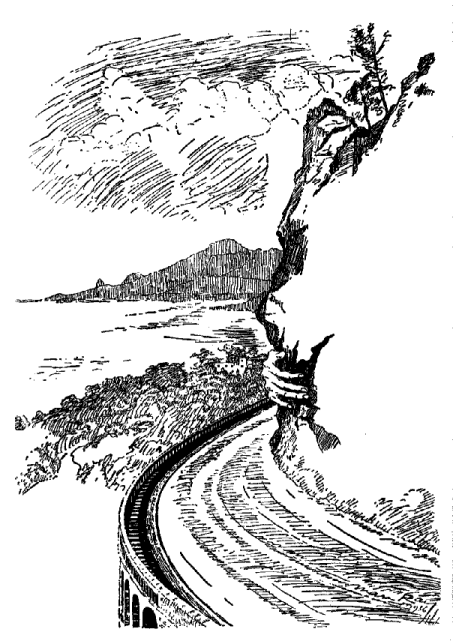

The Turning Point, another illustration by Man Ray, is a metaphor for the endless representations that surreal dreams can give rise to. The sharp turn hides what awaits the traveler. Besides this, to whom does the disproportionate hand belong? The surrealist approach rejects finality and practicality in favor of the imaginary and the indescribable.

Contemporary art: an abundance of dream depictions

Although the dream in art is a theme that has been reinvented over the years, there are still many on the contemporary scene showcasing it. Representations of dreams are abundant, and artists draw clear inspiration from past movements.

Through Julie Lagier’s lens, objects and female figures take on an unusual dimension. Inspired by Surrealism, her art stems from her dreams as she reinterprets them, presenting them in a hazy and evasive manner. In her exploration of Surrealism and dream art, her photographs are joyfully distorted, sometimes falling into the realm of incomprehension to the outside eye.

Gabrielle Rul’s delicate sketches deploy a poetic and authentic imagination.

Dream art, an immortal shape-shifter

In conclusion, whether it be representations of the afterlife or the subconscious, the bringing of the imaginary to our own world, no matter its form, dream art always evokes something powerful within us. As a result, all at once it brings together the personal and the intimate, the fantastical and nightmarish, but equally the prophetic and divine. Artists, contemporary or otherwise, will never finish stunning us with their explorations of dream art.

Art

Art History’s Iconic Depictions of Dreams, from the Renaissance to Surrealism

Julia Fiore

Jean Lecomte du Nouÿ, A Eunuch’s Dream, 1874. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

“When we fall asleep, where do we go?” This was the question looming over the long line of teenage girls who recently waited impatiently outside the Billie Eilish merch pop-up in Chinatown. The pop star didn’t invent this question. Philosophers, poets, and psychoanalysts have rhapsodized about the answer for centuries. It’s visual artists, though, who have, again and again, sought to show the impossible—to imagine, in pictures of sleeping subjects, the unseen places we go when we dream. From Godly visions to fantasies to nightmares, the representations of dreams in art have drastically changed since the Middle Ages.

Nicolas Dipre, The dream of Jacob, ca. 1500. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Georges de la Tour, Dream of St. Joseph, ca. 1600. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

In the Renaissance, as artists and Humanists turned to the writings and art of antiquity, they discovered the ancient philosophers like Hippocrates and Aristotle had been tantalized by the subject of dreams. The 15th-century Florentine philosopher Marsilio Ficino, in particular, took up the task of interpreting the meaning of dreams. His concept of vacatio animae posits that while sleeping, the soul can be freed from the corporeal restraints of the body and achieve a higher, spiritual state.

In art, this spiritual state often took the form of a dozing soul caught in a religious moral dilemma. But dreams also allowed Renaissance artists to heroize the creative imagination and play with sensual, pagan scenes. The Venetian painter Lorenzo Lotto’s Sleeping Apollo and the Muses with Fame (ca. 1549) shows the naked deity napping in an idyllic glade. An angel flying overhead surveys the heaps of discarded clothes and musical instruments, while in the distance, the Muses—reveric stand-ins for the creative imagination—perform an uninhibited dance.

Ary de Vois, Jacob’s Dream, 1660–80. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum.

Yet it was the Biblical dream—a communication from God—that artists were most often called upon to represent. The Old Testament stories of Jacob’s ladder and Joseph’s interpretation of Pharaoh’s dream were popular subjects. In both narratives, their dreams become important catalysts for change.

The dream of Jacob (ca. 1500), an oil-on-panel work by Nicolas Dipre, foregrounds Jacob, dressed ethereally in white, reclining outdoors with his head resting on a rock. His prophetic dream, in which angels mount a ladder to heaven, appears tangibly in the landscape behind his enclave. Jacob’s eyes may be closed, but his sight, the painting suggests, is clear.

Divine visions remained a popular challenge for centuries of Western artists, who imbued the well-worn stories with ulterior meanings. Ary de Vois’s version of Jacob’s dream (1660–80) is pointedly sensual. Jacob, nude save for a strategically placed bit of cloth, languorously stretches out on a patch of grass, his idealized body on full display. The ladder and angels appear far in the background, a decidedly less prominent focus of the picture compared with Dipre’s work. Here, Jacob’s vision from God is nearly ecstatic, offering pleasure to the sleeping figure much like Bernini’s famously erotic St. Teresa in Ecstasy (1647–52).

Followers of Hieronymous Bosch, The Vision of Tundale, ca. 1520–30. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The stuff of nightmares was of little interest to the Italian or French Renaissance artists, who favored neo-Platonic ideals of beauty—until they encountered the disturbing fantasies of northern painters like Hieronymus Bosch. The Vision of Tundale (ca. 1520–30), attributed to Bosch’s followers, is a typically hallucinatory, “Boschian” scene. Inspired by the medieval poem “The Vision of Knight Tondal,” in which an errant knight dreams of his moral redemption after a vision of Hell, the painting depicts a spectacular and grotesque hellscape populated by monstrous creatures and graphic details. The work also takes on the idea of the nightmare as a phenomenon that is visited upon the living as a warning to repent for.Indeed, in the lower left-hand corner, the sleeping sinner Tondal is seen experiencing the nightmare firsthand.

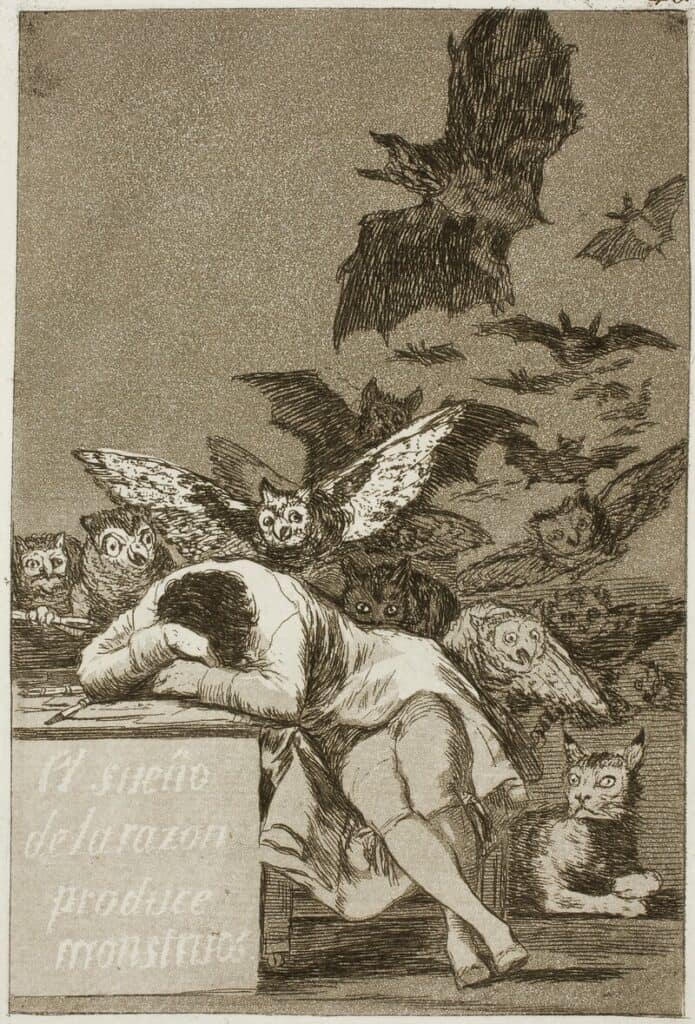

Although the strictures of morality remain intact in The Vision of Tondal, when we slumber, the picture seems to suggest, reason sleeps too. Enlightenment-era artists made political statements about the irrationality exemplified by the nightmare. Francisco de Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (1799) from his biting “Los Caprichos” series, employs the bad dream to criticize contemporary Spanish society, particularly pre-Enlightenment practices and superstitions the artist felt held the country back from modernizing. The central figure’s apparently peaceful sleep is interrupted, for the viewer at least, by the predatory creatures—associated, in Spanish folklore, with evil—that besiege him. Without the Enlightenment value of Reason, Goya forcefully asserts, evil wins.

Henry Fuseli’s famous Nightmare (1781) from around the same time would seem to suggest a similar narrative but is unusual in that it lacks a moral component, or even a literary, biblical, or art-historical precedent. The invented scene shows a woman in white stretched across her bed. A frightening incubus figure crouches on her chest while a horse with flared nostrils pokes its dark head out from behind a curtain. The work’s mysterious intentions and frightening imagery shocked audiences when it debuted, and seems to fall less in line with the “Age of Reason” than the ideals of Romanticism, in which European art and literature began to place value not on moral logic but emotion and spirituality. Some scholars today see the work as a prefiguration of Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theories; Freud reportedly had a reproduction of the painting in his Vienna apartment.

Henri Rousseau, The Sleeping Gypsy, 1897. Photo by VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images

Before Freud, however, in the 19th century, artists involved with the Symbolist movement developed novel means to express subjective psychological and spiritual realities through the landscape of dreams. Their subject matter features heady mixes of fantasy, eroticism, the occult, and death, often to puzzling effect. What is the meaning behind Henri Rousseau’s The Sleeping Gypsy (1897)? Is the lion that licks the sleeping woman’s face a product of her dream or a terror of reality? Is the woman really sleeping in the desert at all, or is the whole picture a dream?

When Freud did publish his theories on dreams and the unconscious, the effect on art was immediate. In the 20th century, dreams became primary source material for the Surrealists, who sought to transcend the constraints of rationality—and the oppressive societal rules that had led mankind to the First World War. The unconscious became a creative tool that contained unexpected meanings and a window onto one’s secret, inner self.

Salvador Dalí interpreted dreams in his paintings in myriad ways, but it’s his 1944 work Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee around a Pomegranate a Second before Waking, that takes on both the act of dreaming and its results in the same picture. The artist’s wife and muse, Gala, sleeps nude on a rock formation coming out of the sea. Gala’s dream manifests in the top half of the canvas, where two tigers and a rifle leap toward the resting figure from the mouth of a fish, which in turn emerges from a bursting pomegranate. As the title suggests, the onslaught of the dream will wake her moments later.

When we fall asleep, where do we go? Dalí, the Surrealists, and their artistic forebears understood the interpretive possibility of dreams as avenues for self-exploration. More importantly, they took full advantage of that question, relishing the creative freedom of the imaginative dreamscape.

JF

Articles and Features

The Art of Depicting Dreams.

How Dreams – and Nightmares – Have Influenced Art History

By Shira Wolfe

“Every act of imagination points implicitly to the dream… the dream is the first condition of its possibility.”

Michel Foucault

Michel Foucault posits that dreams are the starting point of the imagination. Indeed, throughout history, countless artists have taken inspiration for their art from dreams. During the Renaissance, artists often represented the subject of the Biblical dream, the divine vision communicated by God, while the 19th-century Symbolists chose to express subjective psychological and spiritual states through dreams, and the Romantics expressed feelings verging on the mystical, often through visions and dreams. The Surrealists, in turn, used images and stories that came to them in dreams to create wild, bizarre artworks reflecting their subconscious states, as a window into their deepest selves. We take a tour of artworks influenced by dreams throughout the history of art.

1. Raphael, Jacob’s Dream, 1518

In the Renaissance, dreams were depicted in art strictly as a religious experience. Biblical stories in which people had dreamlike visions and encountered higher beings and divine revelations through dreams were popular topics for artists. Raphael’s Jacob’s Dream (1518) is one such depiction of a divine vision: Jacob encounters God in a dream as he journeys out of the promised land. In the dream, Jacob sees a ladder reaching up to heaven, and the angels of God are ascending and descending it. God stands beside Jacob and tells him he is the chosen one, and that he and his offspring will return to this land and the land will belong to them. In Raphael’s painting, we see Jacob sleeping with his head on a rock and God hovering above the angels, dark clouds parting on either side to reveal the golden light of heaven. Jacob may be fast asleep, but the composition of the painting with God and the angels taking centre stage ensures that we understand this dream as a very real vision.

2. Albrecht Dürer, Dream Vision, 1525

One of the first artists to actually paint a dream of their own as opposed to divine visions was Albrecht Dürer. His watercolour painting Dream Vision from 1525 was inspired by a dream he had on June 7, 1525. The dream consisted of a flood which he described as great waters falling from heaven, accompanied by wind and roaring. Dürer was greatly affected by the dream, reporting afterwards: “When I awoke my whole body trembled and I could not recover for a long time.” He painted this watercolour very quickly in order to remember the dream, filling half of the page with his written explanation of the dream.

3. Francisco Goya, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, 1797-1799

Francisco Goya did several series of etchings during his career. The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters is the 43rd etching in his Los Caprichos series, which presented dark satires of eighteenth-century Spain. In this etching, Goya depicts the sleeping artist as the Enlightenment value of Reason, which he asserts is necessary to fight evil. The figure’s peaceful sleep is interrupted by the predatory monsters attacking him from all around, representing pre-Enlightenment superstitions and practices that Goya felt held the country back from modernization and progress. Goya believed that he, “like mankind in general, [could] only overcome superstition, ignorance, and irrationality by uniting reason with fantasy.” The dream and the dreamer therefore presented a perfect vessel for Goya’s message.

4. William Blake, Visionary Heads, 1818

The English poet and painter William Blake made a series of black chalk and pencil drawings starting in 1818 at the request of the artist and astrologer John Varley. Varley believed in the existence of spirits, but was frustrated that he could not see them. Blake claimed to have daily visions since childhood, and so the two started working together to summon spirits. The subjects of the Visionary Heads drawings are what resulted from these meetings: historical and mythical characters that appeared to Blake in visions during his nights with Varley. Some of the characters that together make up the Visionary Heads include David, Solomon, Bathsheba, Job, Socrates, Julius Caesar, Christ, Muhammad, Merlin, John Milton, Voltaire, and Satan. The most famous in the series is The Ghost of a Flea, a miniature painting inspired by a vision Blake had during a session with Varley. The muscular, nude flea is depicted with its tongue sticking out of its mouth, about to feast on a bowl of blood.

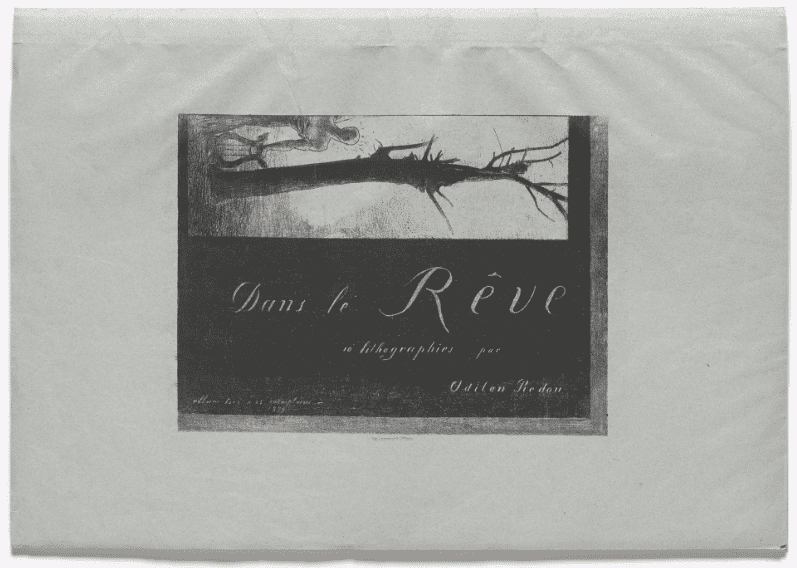

5. Odilon Redon, In the Dream, 1879-1899

Symbolist artist Odilon Redon was once nicknamed the “king of dreams” by art critic Thadée Natanson, as he often depicted scenes from the depths of his subconscious and inner worlds. Redon’s paintings are sensual evocations of his experiences and feelings related to the mysteries of nature. In a series of lithographs, the Noirs, which he created between 1879 and 1899, Redon depicted a terrifying world of hybrid creatures seeming to have appeared out of a nightmare. Images include a spider with the face of a human and a giant flying eyeball. Though he initially created art almost exclusively in black and white like with the nightmarish Noirs, Redon turned to pastels in the 1890s, feeling comforted by the colours. These blurry, colourful paintings came to define Redon’s dreamy painterly style, moving his art from the realm of the nightmare to the realm of the dream.

“I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality.”

André Breton

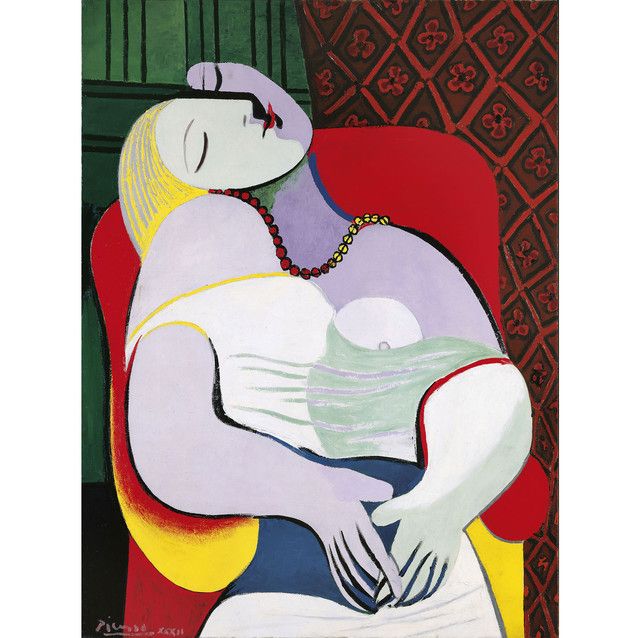

6. Pablo Picasso, The Dream, 1932

Perhaps less inspired by an actual dream than by Picasso’s dreamy state of new love and lust, The Dream is a 1932 painting of Picasso’s young lover, Marie-Thérèse Walter, who was 22 years old at the time. She is depicted with her eyes closed, caught in the middle of a sensual daydream. Picasso’s erotic passion for Marie-Thérèse is written all over the painting: he painted part of her face in the shape of an erect penis, and her hands come together in her lap to form the shape of a vagina.

7. Joan Miró, Dream Paintings, 1925-1927

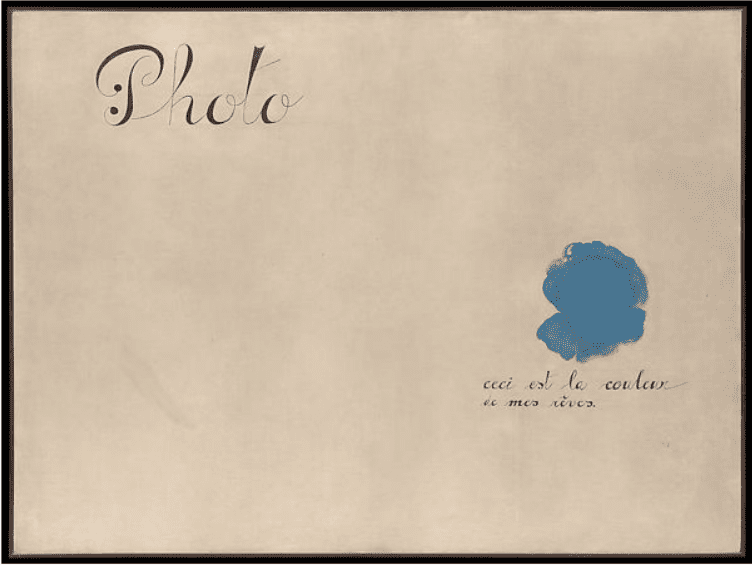

Joan Miró had a particular approach to the influence of dreams on his life and art, saying: “I never dream… Oh, yes! I do dream, I dream when I’m walking down the street, I dream all the time, but these dreams aren’t Freudian dreams. They are waking dreams. I’m always in a state of dreaming while awake. Of course! But dreams while I’m asleep, no.” Miró, then, embarked on his own particular journey to express himself, through a permanent state of alertness and automatic painting. The approximately 100 paintings that Miró created between 1925 and 1927 are known as his “Dream Paintings”. The dream is evoked here, but not literally depicted. The paintings in this dream series often combine recognisable imagery with opaque shapes set against monochromatic backgrounds. In Photo: This is the Color of My Dreams (1925), for example, Miró painted a little dab of blue on a monochrome beige background, and underneath the blue he wrote: “ceci est la couleur de mes rêves”, meaning “this is the color of my dreams”.

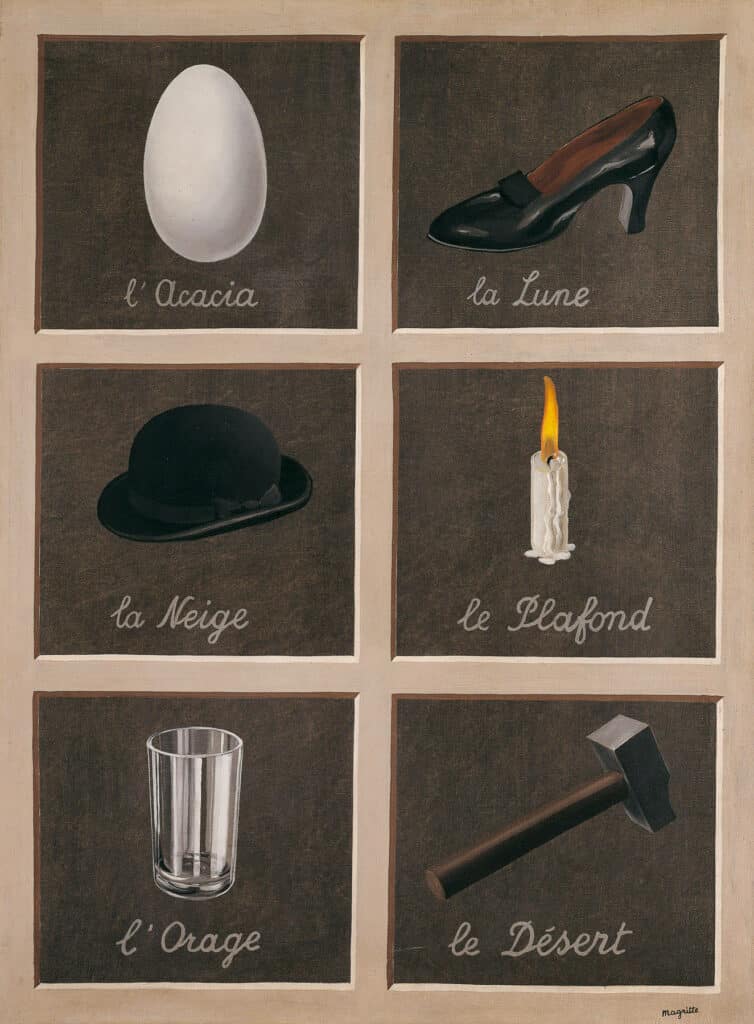

8. René Magritte, The Key to Dreams, 1930

René Magritte is known for displaying ordinary objects in an unusual context, much like what happens when we are dreaming, thus giving new meanings to familiar things. His Surrealist artworks have an illusionist, dreamlike quality and his tendency to juxtapose seemingly unrelated objects in the same painting was for him a means of evoking the essential mystery of the world. In his six-panel image Key to Dreams (1930), Magritte uses simple images (an egg, a shoe, a hat, a candle, a glass and a hammer) and matches them with absolutely unrelated words (acacia, moon, snow, ceiling, storm, desert). The title of the painting points to the fact that we must look beyond the images to deeper layers of meaning in our subconscious, and invites us to consider the relationship between art, language and reality.

9. Salvador Dali, Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening, 1944

Another Surrealist master of dreams, Salvador Dalí, loved creating wild and wonderful paintings that combined the most bizarre images mixing the world of dreams with his psychedelic vision of reality. Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening from 1944 depicts Dalí’s wife and muse Gala, asleep and levitating above a rock by the sea. A yelloweye rockfish comes bursting out of a pomegranate hovering above the sea, while two tigers are about to pounce on the peacefully dreaming Gala and a bayonet, representing a stinging bee, is about to sting Gala awake. Dalí later said of this painting that it was intended “to express for the first time in images Freud’s discovery of the typical dream with a lengthy narrative, the consequence of the instantaneousness of a chance event which causes the sleeper to wake up. Thus, as a bar might fall on the neck of a sleeping person, causing them to wake up and for a long dream to end with the guillotine blade falling on them, the noise of the bee here provokes the sensation of the sting which will awaken Gala.”

10. Jasper Johns, Flag, 1954-1955

In 1954, two years after Jasper Johns had been discharged from the US Army, the artist woke up from a dream in which he painted a large American flag. He immediately got out of bed, went out and bought the materials to start making the painting from his dream. Before painting Flag (1954-1955), Johns had been trying to move to a new level in his artistic life by destroying all the existing work in his possession. The dream marked a new beginning, which led to him painting a series of over 40 flag paintings. For Johns, the painting of a familiar object like the American flag offered a sense of freedom since he did not have to occupy himself with creating a new design, but could rather focus on the execution of the painting.

Relevant sources to learn more

MoMA

Kröller-Müller Museum

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Read more about Surrealist artists and their use of dreams here.

Read more about Symbolism and the influence of dreams and the subconscious here.

Discover more about Jasper Johns and his obsession with painting flags here.

Discover and Buy Art for Sale

This article may lack focus or may be about more than one topic. Please help improve this article, possibly by splitting the article and/or by introducing a disambiguation page, or discuss this issue on the talk page. (October 2017)

Dream art is any form of art that is directly based on a material from one’s dreams, or a material that resembles dreams, but not directly based on them.

Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes: The Dream, 1883

HistoryEdit

The first known reference to dream art was in the 12th century, when Charles Cooper Brown found a new way to look at art. However, dreams as art, without a «real» frame story, appear to be a later development—though there is no way to know whether many premodern works were dream-based.

In European literature, the Romantic movement emphasized the value of emotion and irrational inspiration. «Visions», whether from dreams or intoxication, served as raw material and were taken to represent the artist’s highest creative potential.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Symbolism and Expressionism introduced dream imagery into visual art. Expressionism was also a literary movement, and included the later work of the playwright August Strindberg, who coined the term «dream play» for a style of narrative that did not distinguish between fantasy and reality.

At the same time, discussion of dreams reached a new level of public awareness in the Western world due to the work of Sigmund Freud, who introduced the notion of the subconscious mind as a field of scientific inquiry. Freud greatly influenced the 20th-century Surrealists, who combined the visionary impulses of Romantics and Expressionists with a focus on the unconscious as a creative tool, and an assumption that apparently irrational content could contain significant meaning, perhaps more so than rational content.

The invention of film and animation brought new possibilities for vivid depiction of nonrealistic events, but films consisting entirely of dream imagery have remained an avant-garde rarity. Comic books and comic strips have explored dreams somewhat more often, starting with Winsor McCay’s popular newspaper strips; the trend toward confessional works in alternative comics of the 1980s saw a proliferation of artists drawing their own dreams.

In the collection, The Committee of Sleep, Harvard psychologist Deirdre Barrett identifies modern dream-inspired art such as paintings including Jasper Johns’s Flag, much of the work of Jim Dine and Salvador Dalí, novels ranging from «Sophie’s Choice» to works by Anne Rice and Stephen King and films including Robert Altman’s Three Women, John Sayles Brother from Another Planet and Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries. That book also describes how Paul McCartney’s Yesterday was heard by him in a dream and Most of Billy Joel’s and Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s music has originated in dreams.

Dream material continues to be used by a wide range of contemporary artists for various purposes. This practice is considered by some to be of psychological value for the artist—independent of the artistic value of the results—as part of the discipline of «dream work».

The international Association for the Study of Dreams[1] holds an annual juried show of visual dream art.

Notable works directly based on dreamsEdit

Visual artEdit

- Many works by William Blake (1757–1827)

- Many works by Salvador Dalí (1904–1989)

- Many works by Man Ray

- Many works by Max Magnus Norman

- Many works by Odilon Redon (1840–1916)

- Many works by Jonathan Borofsky (born 1942)

- Many works by Jim Shaw (born 1952)

LiteratureEdit

- The Dream of Rhonabwy (14th century) Welsh prose tale

- The Dream of Macsen Wledig (14th century) Welsh prose tale

- Kubla Khan (1816) by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (possibly based on a dream provoked by opium)

- Frankenstein (1818) by Mary Shelley

- The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886) by Robert Louis Stevenson

- Dracula Bram Stoker claimed was inspired by a nightmare he had experienced

- Ten Nights’ Dreams (1908) by Natsume Soseki

- The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath (1927) and other works by H.P. Lovecraft

- The Kin of Ata Are Waiting for You (1971) by Dorothy Bryant

- Most of Clive Barker’s work

- The Art of Dreaming (1993) ISBN 0-06-092554-X Carlos Castaneda

- The Facts of Winter (2005) by Paul LaFarge

FilmEdit

- Several films of Andrei Tarkovsky, most notably The Mirror

- The major films of Sergei Parajanov, most notably Sayat Nova and Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors

- Much of the filmography of David Lynch (e.g. Eraserhead, Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive, etc.)

- The Brother from Another Planet by John Sayles

- Dreams (1990) by Akira Kurosawa

- Many works of Federico Fellini (1920–1993)

- The works of Luis Buñuel

- Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), At Land (1944), and Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946) by Maya Deren.

- 3 Women (1977) by Robert Altman

- Eyes Wide Shut (1999) by Stanley Kubrick

- Waking Life (2001) by Richard Linklater

- Destino (2003), an animated short film by Dominique Monféry

- Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) and Science of Sleep (2006) by Michel Gondry

- Paprika (2006) by Satoshi Kon

- Dream (2008) by Kim Ki-duk

- Inception (2010) directed by Christopher Nolan

- Lucid Dream (2017) by Kim Joon-sung

- Napping Princess by Kenji Kamiyama (2017)

- 118 (2019) by K. V. Guhan

- Malignant (2021) by James Wan

- Last Night in Soho (2021) by Edgar Wright

- Slumberland (2022) by Francis Lawrence

ComicsEdit

- Many short works of Julie Doucet

- Many short works of David B.

- Jim by Jim Woodring

- Psychonaut by Aleksandar Zograf

- Rare Bit Fiends by Rick Veitch

- Slow Wave by Jesse Reklaw

MusicEdit

- Devil’s Trill Sonata by Giuseppe Tartini

- Réverie by Claude Debussy

- La Villa Strangiato by Rush

- Selected Ambient Works Volume II by Aphex Twin

- Yesterday by Paul McCartney

- El Cielo by Dredg

- Inside a Dream by Jane Wiedlin

- Isn’t Anything and Loveless by My Bloody Valentine

- And the Glass-Handed Kites and other works of Mew

- If I Needed You by Townes Van Zandt

- The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking by Roger Waters

- Lucid Dreams by Celia Green

- Micro Cuts by Muse

- My Fruit Psychobells…A Seed Combustible, Bath, Leaving Your Body Map, and Part the Second by maudlin of the Well

- Dimethyltryptamine by Jay Electronica

- Until the Quiet Comes by Flying Lotus[1]

- Dreaming by Blondie

Video GamesEdit

- Yume Nikki by Kikiyama

- Omori by Omocat

- LSD: Dream Emulator by Asmik Ace Entertainment

Works intended to resemble dreams, but not directly based on themEdit

NovelsEdit

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (1865)

- The Nightmare has Triplets trilogy by James Branch Cabell

- Smirt: An Urbane Nightmare (1934)

- Smith: A Sylvan Interlude (1934)

- Smire: An Acceptance in the Third Person (1937)

- The Coma by Alex Garland

- «Darkness at Noon» by Arther Koestler

- Most of the works of Franz Kafka

- Finnegans Wake by James Joyce

- Wake Trilogy by Lisa McMann

- WAKE (2008)

- FADE (2009)

- GONE (2010)

DramaEdit

- A Dream Play (1901) and other plays by August Strindberg during his Symbolist and Expressionist periods

- Copacabana by Barry Manilow (born 1947)

FilmEdit

- Un chien andalou (1927) by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí (actually started when Buñuel and Dalí discussed their dreams, then decided to start with two of them and make a film)

- Many films by Maya Deren (1917–1961)

- Many films by David Lynch, especially Eraserhead and Mulholland Drive, contain dreamlike elements.

- Dream scenes are popular in many horror movies, notably the Nightmare on Elm Street series

- The Trial by Orson Welles (based on the novel by Franz Kafka)

- Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind features around witnessing the effects of having one’s memory erased through dreaming.

- The Science of Sleep (2006) by Michel Gondry

- The Cell (2000) by Tarsem Singh contains vivid and surreal imagery to convey the mind-world of a serial killer.

- The Good Night (2007) by Jake Paltrow

- The animated science fiction film Paprika (2006) by Satoshi Kon features intense dream imagery.

- Inception (2010) by Christopher Nolan contains extravagant sequences inside the dreams of people through «dream sharing». There are many sequences in ‘reality’ that also feature very dream-like imagery, questioning the main protagonist’s state of consciousness.

ComicsEdit

- Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend (1904–1921) and Little Nemo (1905–1913) by Winsor McCay (also his animated films)

- The Sandman (DC Comics/Vertigo) by Neil Gaiman

- Many works of Milo Manara

- Dream Company, a webcomic by Moon Ji-Hyeon

See alsoEdit

- Dream world (plot device)

- Video games about dreams :Category:Video games about dreams

- Magic realism

- Fantastic art

- Dream pop

- Shoegaze

- Psychedelic art

- Dream diary

- Dream interpretation

ReferencesEdit

- ^ Lawler, Karen (October 5, 2012). «Flying Lotus – Until The Quiet Comes». State. County Kildare. Archived from the original on 2013-10-30. Retrieved 2012-10-05.

Further readingEdit

- Reisman, David. Foreign Objects: Dream Drawings. New York: Hornbill Press, 2004.

External linksEdit

- Dreams: Artwork of the Collective Unconscious Archived 2014-08-26 at the Wayback Machine (1998) by Gail Bixler-Thomas

- Fuzzy Dreamz (1996) by Dr. Hugo Heyrman —an online art project of short films, forming a psychogeography of dreams.

Enchant

“All art is perhaps a form of dream,” Borges said. This is a selection of paintings and texts that came straight from that great kingdom of the night.

Chuang Tzu dreamt that he was a butterfly flittering and fluttering around as he pleased. Suddenly he woke up and realized that he was Chuang Tzu. But he did not know whether he was Chuang Tzu dreaming that he was a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming he was

–“Dream of the Butterfly,” Chuang Tzu.

“Literature is full of dreams that we remember more clearly than our own,” Francine Prose wrote in the New York Review of Books in an article regarding the theme. And yes, there is the unforgettable dream of Gregory Samsa in “Metamorphosis,” the dream of Alice in Wonderland, the dreams in the works of Shakespeare or the fabulous turn of the screw in the dream of Anna Karenina. And there are, of course, the prophetic dreams of the East and the allegories of the Middle Ages. But painting is also full of memorable, disturbing, persuasive dreams in which we often see the body itself that dreams with the element of the dream incorporated in a variety of ways.

To translate into literature or painting something as intangible as a dream, in which the mind is both a theater, the actors and the auditorium (and the author of the fable that we see) has been a seductive exercise for the greatest writers and artists. “Coleridge wrote that the images of wakefulness inspire feelings, while feelings inspire images,” Borges said in his prologue to the wonderful Book of Dreams that compiles dreams in the history of universal literature. Art is permeated by dreams: the night penetrates the doings of the day.

The following is a brief selection of literary and pictorial works of that “art of the night” that has influenced so many artists to create some of the best works we have.

.

The Nightmare, Henry Fuseli (1781).

Book of Dreams, Jorge Luis Borges (1976)

A magnificent compilation of dreams and nightmares. “This book of dreams that readers will once again dream includes dreams of the night – such as those that I wrote, for example – daydreams, which are a voluntary exercise by our minds, and others of lost roots: let’s day the Anglo Saxon dream of the Cross,” Borges says in its prologue.

The Dream, Odilon Redon (1878 – 1882).

Einstein’s Dreams, Alan Lightman (1993)

The author creates a fictional collage of stories dreamed by Albert Einstein in 1905, when he worked in a patents office in Switzerland. Imagine what the scientist dreamed of while he created his theory of relativity, his new concept of time.

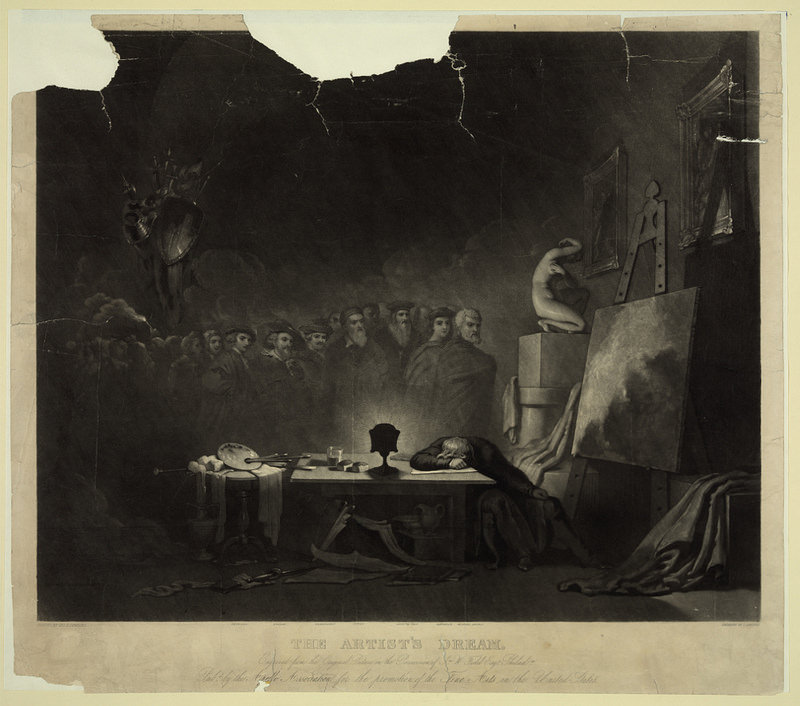

The Artist’s Dream, George H. Comegys (1840).

Sandman, Neil Gaiman

Sandman has become a legendary character in northern European folklore who, by sprinkling sand in the eyes of the dreamer, brings them pleasant dreams while they sleep. In the fascinating series of graphic novels by Gaiman, the Dream character, also known as Morpheus, is both the king and the personification of all the dreams in history, of all that is outside reality.

Header image: Job’s Evil Dreams, by William Blake (1805).

When ancient rituals became religion

The emergence of religions irreversibly changed the history of humanity. It’s therefore essential to ask when and how did ancient peoples’ rituals become organized systems of thought, each with their

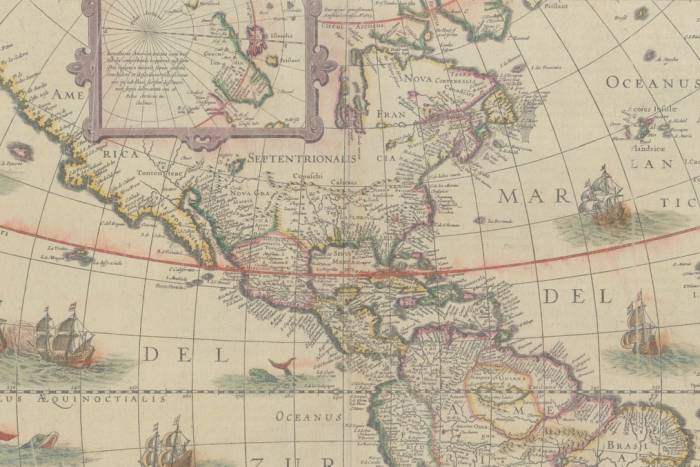

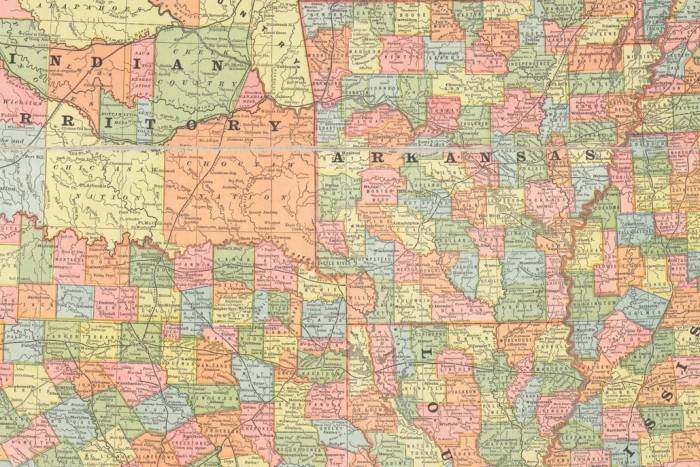

Seven ancient maps of the Americas

A map is not the territory. —Alfred Korzybski Maps are never merely maps. They’re human projections, metaphors in which we find both the geographical and the imaginary. The cases of ghost islands

An artist crochets a perfect skeleton and internal organs

Shanell Papp is a skilled textile and crochet artist. She spent four long months crocheting a life-size skeleton in wool. She then filled it in with the organs of the human body in an act as patient

A musical tribute to maps

A sequence of sounds, rhythms, melodies and silences: music is a most primitive art, the most essential, and the most powerful of all languages. Its capacity is not limited to the (hardly trivial)

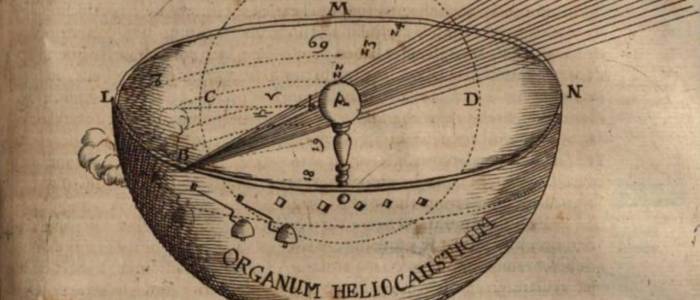

The enchantment of 17th-century optics

The sense of sight is perhaps one the imagination’s most prolific masters. That is why humankind has been fascinated and bewitched by optics and their possibilities for centuries. Like the heart, the

Would you found your own micro-nation? These eccentric examples show how easy it can be

Founding a country is, in some ways, a simple task. It is enough to manifest its existence and the motives for creating a new political entity. At least that is what has been demonstrated by the

Wondrous crossings: the galaxy caves of New Zealand

Often, the most extraordinary phenomena are “jealous of themselves” ––and they happen where the human eye cannot enjoy them. However, they can be discovered, and when we do find them we experience a

Think you have strange reading habits? Wait until you’ve seen how Mcluhan reads

We often forget or neglect to think about the infinite circumstances that are condensed in the acts that we consider habitual. Using a fork to eat, for example, or walking down the street and being

The sky is calling us, a love letter to the cosmos (video)

We once dreamt of open sails and Open seas We once dreamt of new frontiers and New lands Are we still a brave people? We must not forget that the very stars we see nowadays are the same stars and

The sister you always wanted (but made into a crystal chandelier)

Lucas Maassen always wanted to have a sister. And after 36 years he finally procured one, except, as strange as it may sound, in the shape of a chandelier. Maassen, a Dutch designer, asked the