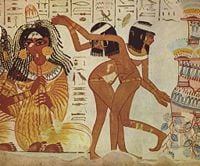

Religion and expressive art are important aspects of human culture.

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.[1] Culture is often originated from or attributed to a specific region or location.

Humans acquire culture through the learning processes of enculturation and socialization, which is shown by the diversity of cultures across societies.

A cultural norm codifies acceptable conduct in society; it serves as a guideline for behavior, dress, language, and demeanor in a situation, which serves as a template for expectations in a social group.

Accepting only a monoculture in a social group can bear risks, just as a single species can wither in the face of environmental change, for lack of functional responses to the change.[2]

Thus in military culture, valor is counted a typical behavior for an individual and duty, honor, and loyalty to the social group are counted as virtues or functional responses in the continuum of conflict. In the practice of religion, analogous attributes can be identified in a social group.

Cultural change, or repositioning, is the reconstruction of a cultural concept of a society.[3] Cultures are internally affected by both forces encouraging change and forces resisting change. Cultures are externally affected via contact between societies.

Organizations like UNESCO attempt to preserve culture and cultural heritage.

Description

Pygmy music has been polyphonic well before their discovery by non-African explorers of the Baka, Aka, Efe, and other foragers of the Central African forests, in the 1200s, which is at least 200 years before polyphony developed in Europe. Note the multiple lines of singers and dancers. The motifs are independent, with theme and variation interweaving.[4] This type of music is thought to be the first expression of polyphony in world music.

Culture is considered a central concept in anthropology, encompassing the range of phenomena that are transmitted through social learning in human societies. Cultural universals are found in all human societies. These include expressive forms like art, music, dance, ritual, religion, and technologies like tool usage, cooking, shelter, and clothing. The concept of material culture covers the physical expressions of culture, such as technology, architecture and art, whereas the immaterial aspects of culture such as principles of social organization (including practices of political organization and social institutions), mythology, philosophy, literature (both written and oral), and science comprise the intangible cultural heritage of a society.[5]

In the humanities, one sense of culture as an attribute of the individual has been the degree to which they have cultivated a particular level of sophistication in the arts, sciences, education, or manners. The level of cultural sophistication has also sometimes been used to distinguish civilizations from less complex societies. Such hierarchical perspectives on culture are also found in class-based distinctions between a high culture of the social elite and a low culture, popular culture, or folk culture of the lower classes, distinguished by the stratified access to cultural capital. In common parlance, culture is often used to refer specifically to the symbolic markers used by ethnic groups to distinguish themselves visibly from each other such as body modification, clothing or jewelry. Mass culture refers to the mass-produced and mass mediated forms of consumer culture that emerged in the 20th century. Some schools of philosophy, such as Marxism and critical theory, have argued that culture is often used politically as a tool of the elites to manipulate the proletariat and create a false consciousness. Such perspectives are common in the discipline of cultural studies. In the wider social sciences, the theoretical perspective of cultural materialism holds that human symbolic culture arises from the material conditions of human life, as humans create the conditions for physical survival, and that the basis of culture is found in evolved biological dispositions.

When used as a count noun, a «culture» is the set of customs, traditions, and values of a society or community, such as an ethnic group or nation. Culture is the set of knowledge acquired over time. In this sense, multiculturalism values the peaceful coexistence and mutual respect between different cultures inhabiting the same planet. Sometimes «culture» is also used to describe specific practices within a subgroup of a society, a subculture (e.g. «bro culture»), or a counterculture. Within cultural anthropology, the ideology and analytical stance of cultural relativism hold that cultures cannot easily be objectively ranked or evaluated because any evaluation is necessarily situated within the value system of a given culture.

Etymology

The modern term «culture» is based on a term used by the ancient Roman orator Cicero in his Tusculanae Disputationes, where he wrote of a cultivation of the soul or «cultura animi,»[6] using an agricultural metaphor for the development of a philosophical soul, understood teleologically as the highest possible ideal for human development. Samuel Pufendorf took over this metaphor in a modern context, meaning something similar, but no longer assuming that philosophy was man’s natural perfection. His use, and that of many writers after him, «refers to all the ways in which human beings overcome their original barbarism, and through artifice, become fully human.»[7]

In 1986, philosopher Edward S. Casey wrote, «The very word culture meant ‘place tilled’ in Middle English, and the same word goes back to Latin colere, ‘to inhabit, care for, till, worship’ and cultus, ‘A cult, especially a religious one.’ To be cultural, to have a culture, is to inhabit a place sufficiently intensely to cultivate it—to be responsible for it, to respond to it, to attend to it caringly.»[8]

Culture described by Richard Velkley:[7]

… originally meant the cultivation of the soul or mind, acquires most of its later modern meaning in the writings of the 18th-century German thinkers, who were on various levels developing Rousseau’s criticism of «modern liberalism and Enlightenment.» Thus a contrast between «culture» and «civilization» is usually implied in these authors, even when not expressed as such.

In the words of anthropologist E.B. Tylor, it is «that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.»[9] Alternatively, in a contemporary variant, «Culture is defined as a social domain that emphasizes the practices, discourses and material expressions, which, over time, express the continuities and discontinuities of social meaning of a life held in common.[10]

The Cambridge English Dictionary states that culture is «the way of life, especially the general customs and beliefs, of a particular group of people at a particular time.»[11] Terror management theory posits that culture is a series of activities and worldviews that provide humans with the basis for perceiving themselves as «person[s] of worth within the world of meaning»—raising themselves above the merely physical aspects of existence, in order to deny the animal insignificance and death that Homo sapiens became aware of when they acquired a larger brain.[12][13]

The word is used in a general sense as the evolved ability to categorize and represent experiences with symbols and to act imaginatively and creatively. This ability arose with the evolution of behavioral modernity in humans around 50,000 years ago and is often thought to be unique to humans. However, some other species have demonstrated similar, though much less complicated, abilities for social learning. It is also used to denote the complex networks of practices and accumulated knowledge and ideas that are transmitted through social interaction and exist in specific human groups, or cultures, using the plural form.[citation needed]

Change

The Beatles exemplified changing cultural dynamics, not only in music, but fashion and lifestyle. Over a half century after their emergence, they continue to have a worldwide cultural impact.

Raimon Panikkar identified 29 ways in which cultural change can be brought about, including growth, development, evolution, involution, renovation, reconception, reform, innovation, revivalism, revolution, mutation, progress, diffusion, osmosis, borrowing, eclecticism, syncretism, modernization, indigenization, and transformation.[14] In this context, modernization could be viewed as adoption of Enlightenment era beliefs and practices, such as science, rationalism, industry, commerce, democracy, and the notion of progress. Rein Raud, building on the work of Umberto Eco, Pierre Bourdieu and Jeffrey C. Alexander, has proposed a model of cultural change based on claims and bids, which are judged by their cognitive adequacy and endorsed or not endorsed by the symbolic authority of the cultural community in question.[15]

Cultural invention has come to mean any innovation that is new and found to be useful to a group of people and expressed in their behavior but which does not exist as a physical object. Humanity is in a global «accelerating culture change period,» driven by the expansion of international commerce, the mass media, and above all, the human population explosion, among other factors. Culture repositioning means the reconstruction of the cultural concept of a society.[16]

Full-length profile portrait of a Turkmen woman, standing on a carpet at the entrance to a yurt, dressed in traditional clothing and jewelry

Cultures are internally affected by both forces encouraging change and forces resisting change. These forces are related to both social structures and natural events, and are involved in the perpetuation of cultural ideas and practices within current structures, which themselves are subject to change.[17]

Social conflict and the development of technologies can produce changes within a society by altering social dynamics and promoting new cultural models, and spurring or enabling generative action. These social shifts may accompany ideological shifts and other types of cultural change. For example, the U.S. feminist movement involved new practices that produced a shift in gender relations, altering both gender and economic structures. Environmental conditions may also enter as factors. For example, after tropical forests returned at the end of the last ice age, plants suitable for domestication were available, leading to the invention of agriculture, which in turn brought about many cultural innovations and shifts in social dynamics.[18]

Cultures are externally affected via contact between societies, which may also produce—or inhibit—social shifts and changes in cultural practices. War or competition over resources may impact technological development or social dynamics. Additionally, cultural ideas may transfer from one society to another, through diffusion or acculturation. In diffusion, the form of something (though not necessarily its meaning) moves from one culture to another. For example, Western restaurant chains and culinary brands sparked curiosity and fascination to the Chinese as China opened its economy to international trade in the late 20th-century.[19] «Stimulus diffusion» (the sharing of ideas) refers to an element of one culture leading to an invention or propagation in another. «Direct borrowing,» on the other hand, tends to refer to technological or tangible diffusion from one culture to another. Diffusion of innovations theory presents a research-based model of why and when individuals and cultures adopt new ideas, practices, and products.[20]

Acculturation has different meanings. Still, in this context, it refers to the replacement of traits of one culture with another, such as what happened to certain Native American tribes and many indigenous peoples across the globe during the process of colonization. Related processes on an individual level include assimilation (adoption of a different culture by an individual) and transculturation. The transnational flow of culture has played a major role in merging different cultures and sharing thoughts, ideas, and beliefs.

Early modern discourses

German Romanticism

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) formulated an individualist definition of «enlightenment» similar to the concept of bildung: «Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity.»[21] He argued that this immaturity comes not from a lack of understanding, but from a lack of courage to think independently. Against this intellectual cowardice, Kant urged: «Sapere Aude» («Dare to be wise!»). In reaction to Kant, German scholars such as Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) argued that human creativity, which necessarily takes unpredictable and highly diverse forms, is as important as human rationality. Moreover, Herder proposed a collective form of Bildung: «For Herder, Bildung was the totality of experiences that provide a coherent identity, and sense of common destiny, to a people.»[22]

In 1795, the Prussian linguist and philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835) called for an anthropology that would synthesize Kant’s and Herder’s interests. During the Romantic era, scholars in Germany, especially those concerned with nationalist movements—such as the nationalist struggle to create a «Germany» out of diverse principalities, and the nationalist struggles by ethnic minorities against the Austro-Hungarian Empire—developed a more inclusive notion of culture as «worldview» (Weltanschauung).[23] According to this school of thought, each ethnic group has a distinct worldview that is incommensurable with the worldviews of other groups. Although more inclusive than earlier views, this approach to culture still allowed for distinctions between «civilized» and «primitive» or «tribal» cultures.

In 1860, Adolf Bastian (1826–1905) argued for «the psychic unity of mankind.»[24] He proposed that a scientific comparison of all human societies would reveal that distinct worldviews consisted of the same basic elements. According to Bastian, all human societies share a set of «elementary ideas» (Elementargedanken); different cultures, or different «folk ideas» (Völkergedanken), are local modifications of the elementary ideas.[25] This view paved the way for the modern understanding of culture. Franz Boas (1858–1942) was trained in this tradition, and he brought it with him when he left Germany for the United States.[26]

English Romanticism

British poet and critic Matthew Arnold viewed «culture» as the cultivation of the humanist ideal.

In the 19th century, humanists such as English poet and essayist Matthew Arnold (1822–1888) used the word «culture» to refer to an ideal of individual human refinement, of «the best that has been thought and said in the world.»[27] This concept of culture is also comparable to the German concept of bildung: «…culture being a pursuit of our total perfection by means of getting to know, on all the matters which most concern us, the best which has been thought and said in the world.»[27]

In practice, culture referred to an elite ideal and was associated with such activities as art, classical music, and haute cuisine.[28] As these forms were associated with urban life, «culture» was identified with «civilization» (from Latin: civitas, lit. ‘city’). Another facet of the Romantic movement was an interest in folklore, which led to identifying a «culture» among non-elites. This distinction is often characterized as that between high culture, namely that of the ruling social group, and low culture. In other words, the idea of «culture» that developed in Europe during the 18th and early 19th centuries reflected inequalities within European societies.[29]

British anthropologist Edward Tylor was one of the first English-speaking scholars to use the term culture in an inclusive and universal sense.

Matthew Arnold contrasted «culture» with anarchy; other Europeans, following philosophers Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, contrasted «culture» with «the state of nature.» According to Hobbes and Rousseau, the Native Americans who were being conquered by Europeans from the 16th centuries on were living in a state of nature; this opposition was expressed through the contrast between «civilized» and «uncivilized.»[30] According to this way of thinking, one could classify some countries and nations as more civilized than others and some people as more cultured than others. This contrast led to Herbert Spencer’s theory of Social Darwinism and Lewis Henry Morgan’s theory of cultural evolution. Just as some critics have argued that the distinction between high and low cultures is an expression of the conflict between European elites and non-elites, other critics have argued that the distinction between civilized and uncivilized people is an expression of the conflict between European colonial powers and their colonial subjects.

Other 19th-century critics, following Rousseau, have accepted this differentiation between higher and lower culture, but have seen the refinement and sophistication of high culture as corrupting and unnatural developments that obscure and distort people’s essential nature. These critics considered folk music (as produced by «the folk,» i.e., rural, illiterate, peasants) to honestly express a natural way of life, while classical music seemed superficial and decadent. Equally, this view often portrayed indigenous peoples as «noble savages» living authentic and unblemished lives, uncomplicated and uncorrupted by the highly stratified capitalist systems of the West.

In 1870 the anthropologist Edward Tylor (1832–1917) applied these ideas of higher versus lower culture to propose a theory of the evolution of religion. According to this theory, religion evolves from more polytheistic to more monotheistic forms.[31] In the process, he redefined culture as a diverse set of activities characteristic of all human societies. This view paved the way for the modern understanding of religion.

Anthropology

Petroglyphs in modern-day Gobustan, Azerbaijan, dating back to 10,000 BCE and indicating a thriving culture

Although anthropologists worldwide refer to Tylor’s definition of culture,[32] in the 20th century «culture» emerged as the central and unifying concept of American anthropology, where it most commonly refers to the universal human capacity to classify and encode human experiences symbolically, and to communicate symbolically encoded experiences socially.[33] American anthropology is organized into four fields, each of which plays an important role in research on culture: biological anthropology, linguistic anthropology, cultural anthropology, and in the United States and Canada, archaeology.[34][35][36][37] The term Kulturbrille, or «culture glasses,» coined by German American anthropologist Franz Boas, refers to the «lenses» through which a person sees their own culture. Martin Lindstrom asserts that Kulturbrille, which allow a person to make sense of the culture they inhabit, «can blind us to things outsiders pick up immediately.»[38]

Sociology

An example of folkloric dancing in Colombia

The sociology of culture concerns culture as manifested in society. For sociologist Georg Simmel (1858–1918), culture referred to «the cultivation of individuals through the agency of external forms which have been objectified in the course of history.»[39] As such, culture in the sociological field can be defined as the ways of thinking, the ways of acting, and the material objects that together shape a people’s way of life. Culture can be either of two types, non-material culture or material culture.[5] Non-material culture refers to the non-physical ideas that individuals have about their culture, including values, belief systems, rules, norms, morals, language, organizations, and institutions, while material culture is the physical evidence of a culture in the objects and architecture they make or have made. The term tends to be relevant only in archeological and anthropological studies, but it specifically means all material evidence which can be attributed to culture, past or present.

Cultural sociology first emerged in Weimar Germany (1918–1933), where sociologists such as Alfred Weber used the term Kultursoziologie (‘cultural sociology’). Cultural sociology was then reinvented in the English-speaking world as a product of the cultural turn of the 1960s, which ushered in structuralist and postmodern approaches to social science. This type of cultural sociology may be loosely regarded as an approach incorporating cultural analysis and critical theory. Cultural sociologists tend to reject scientific methods, instead hermeneutically focusing on words, artifacts and symbols.[40] Culture has since become an important concept across many branches of sociology, including resolutely scientific fields like social stratification and social network analysis. As a result, there has been a recent influx of quantitative sociologists to the field. Thus, there is now a growing group of sociologists of culture who are, confusingly, not cultural sociologists. These scholars reject the abstracted postmodern aspects of cultural sociology, and instead, look for a theoretical backing in the more scientific vein of social psychology and cognitive science.[41]

Nowruz is a good sample of popular and folklore culture that is celebrated by people in more than 22 countries with different nations and religions, at the 1st day of spring. It has been celebrated by diverse communities for over 7,000 years.

Early researchers and development of cultural sociology

The sociology of culture grew from the intersection between sociology (as shaped by early theorists like Marx,[42] Durkheim, and Weber) with the growing discipline of anthropology, wherein researchers pioneered ethnographic strategies for describing and analyzing a variety of cultures around the world. Part of the legacy of the early development of the field lingers in the methods (much of cultural, sociological research is qualitative), in the theories (a variety of critical approaches to sociology are central to current research communities), and in the substantive focus of the field. For instance, relationships between popular culture, political control, and social class were early and lasting concerns in the field.

Cultural studies

In the United Kingdom, sociologists and other scholars influenced by Marxism such as Stuart Hall (1932–2014) and Raymond Williams (1921–1988) developed cultural studies. Following nineteenth-century Romantics, they identified culture with consumption goods and leisure activities (such as art, music, film, food, sports, and clothing). They saw patterns of consumption and leisure as determined by relations of production, which led them to focus on class relations and the organization of production.[43][44]

In the United Kingdom, cultural studies focuses largely on the study of popular culture; that is, on the social meanings of mass-produced consumer and leisure goods. Richard Hoggart coined the term in 1964 when he founded the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies or CCCS.[45] It has since become strongly associated with Stuart Hall,[46] who succeeded Hoggart as Director.[47] Cultural studies in this sense, then, can be viewed as a limited concentration scoped on the intricacies of consumerism, which belongs to a wider culture sometimes referred to as Western civilization or globalism.

From the 1970s onward, Stuart Hall’s pioneering work, along with that of his colleagues Paul Willis, Dick Hebdige, Tony Jefferson, and Angela McRobbie, created an international intellectual movement. As the field developed, it began to combine political economy, communication, sociology, social theory, literary theory, media theory, film/video studies, cultural anthropology, philosophy, museum studies, and art history to study cultural phenomena or cultural texts. In this field researchers often concentrate on how particular phenomena relate to matters of ideology, nationality, ethnicity, social class, and/or gender.[48] Cultural studies is concerned with the meaning and practices of everyday life. These practices comprise the ways people do particular things (such as watching television or eating out) in a given culture. It also studies the meanings and uses people attribute to various objects and practices. Specifically, culture involves those meanings and practices held independently of reason. Watching television to view a public perspective on a historical event should not be thought of as culture unless referring to the medium of television itself, which may have been selected culturally; however, schoolchildren watching television after school with their friends to «fit in» certainly qualifies since there is no grounded reason for one’s participation in this practice.

In the context of cultural studies, a text includes not only written language, but also films, photographs, fashion or hairstyles: the texts of cultural studies comprise all the meaningful artifacts of culture.[49] Similarly, the discipline widens the concept of culture. Culture, for a cultural-studies researcher, not only includes traditional high culture (the culture of ruling social groups)[50] and popular culture, but also everyday meanings and practices. The last two, in fact, have become the main focus of cultural studies. A further and recent approach is comparative cultural studies, based on the disciplines of comparative literature and cultural studies.[51]

Scholars in the United Kingdom and the United States developed somewhat different versions of cultural studies after the late 1970s. The British version of cultural studies had originated in the 1950s and 1960s, mainly under the influence of Richard Hoggart, E.P. Thompson, and Raymond Williams, and later that of Stuart Hall and others at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham. This included overtly political, left-wing views, and criticisms of popular culture as «capitalist» mass culture; it absorbed some of the ideas of the Frankfurt School critique of the «culture industry» (i.e. mass culture). This emerges in the writings of early British cultural-studies scholars and their influences: see the work of (for example) Raymond Williams, Stuart Hall, Paul Willis, and Paul Gilroy.

In the United States, Lindlof and Taylor write, «cultural studies [were] grounded in a pragmatic, liberal-pluralist tradition.»[52] The American version of cultural studies initially concerned itself more with understanding the subjective and appropriative side of audience reactions to, and uses of, mass culture; for example, American cultural-studies advocates wrote about the liberatory aspects of fandom.[citation needed] The distinction between American and British strands, however, has faded.[citation needed] Some researchers, especially in early British cultural studies, apply a Marxist model to the field. This strain of thinking has some influence from the Frankfurt School, but especially from the structuralist Marxism of Louis Althusser and others. The main focus of an orthodox Marxist approach concentrates on the production of meaning. This model assumes a mass production of culture and identifies power as residing with those producing cultural artifacts. In a Marxist view, the mode and relations of production form the economic base of society, which constantly interacts and influences superstructures, such as culture.[53] Other approaches to cultural studies, such as feminist cultural studies and later American developments of the field, distance themselves from this view. They criticize the Marxist assumption of a single, dominant meaning, shared by all, for any cultural product. The non-Marxist approaches suggest that different ways of consuming cultural artifacts affect the meaning of the product. This view comes through in the book Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman (by Paul du Gay et al.),[54] which seeks to challenge the notion that those who produce commodities control the meanings that people attribute to them. Feminist cultural analyst, theorist, and art historian Griselda Pollock contributed to cultural studies from viewpoints of art history and psychoanalysis. The writer Julia Kristeva is among influential voices at the turn of the century, contributing to cultural studies from the field of art and psychoanalytical French feminism.[55]

Petrakis and Kostis (2013) divide cultural background variables into two main groups:[56]

- The first group covers the variables that represent the «efficiency orientation» of the societies: performance orientation, future orientation, assertiveness, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance.

- The second covers the variables that represent the «social orientation» of societies, i.e., the attitudes and lifestyles of their members. These variables include gender egalitarianism, institutional collectivism, in-group collectivism, and human orientation.

In 2016, a new approach to culture was suggested by Rein Raud,[15] who defines culture as the sum of resources available to human beings for making sense of their world and proposes a two-tiered approach, combining the study of texts (all reified meanings in circulation) and cultural practices (all repeatable actions that involve the production, dissemination or transmission of purposes), thus making it possible to re-link anthropological and sociological study of culture with the tradition of textual theory.

Psychology

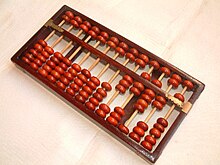

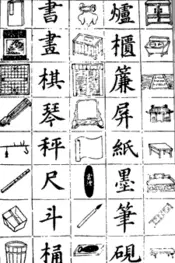

Cognitive tools suggest a way for people from certain culture to deal with real-life problems, like Suanpan for Chinese to perform mathematical calculation.

Starting in the 1990s,[57]: 31 psychological research on culture influence began to grow and challenge the universality assumed in general psychology.[58]: 158–168 [59] Culture psychologists began to try to explore the relationship between emotions and culture, and answer whether the human mind is independent from culture. For example, people from collectivistic cultures, such as the Japanese, suppress their positive emotions more than their American counterparts.[60] Culture may affect the way that people experience and express emotions. On the other hand, some researchers try to look for differences between people’s personalities across cultures.[61][62] As different cultures dictate distinctive norms, culture shock is also studied to understand how people react when they are confronted with other cultures. Cognitive tools may not be accessible or they may function differently cross culture.[57]: 19 For example, people who are raised in a culture with an abacus are trained with distinctive reasoning style.[63] Cultural lenses may also make people view the same outcome of events differently. Westerners are more motivated by their successes than their failures, while East Asians are better motivated by the avoidance of failure.[64] Culture is important for psychologists to consider when understanding the human mental operation.

Protection of culture

There are a number of international agreements and national laws relating to the protection of culture and cultural heritage. UNESCO and its partner organizations such as Blue Shield International coordinate international protection and local implementation.[65][66]

Basically, the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict and the UNESCO Convention for the Protection of Cultural Diversity deal with the protection of culture. Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights deals with cultural heritage in two ways: it gives people the right to participate in cultural life on the one hand and the right to the protection of their contributions to cultural life on the other.[67]

The protection of culture and cultural goods is increasingly taking up a large area nationally and internationally. Under international law, the UN and UNESCO try to set up and enforce rules for this. The aim is not to protect a person’s property, but rather to preserve the cultural heritage of humanity, especially in the event of war and armed conflict. According to Karl von Habsburg, President of Blue Shield International, the destruction of cultural assets is also part of psychological warfare. The target of the attack is the identity of the opponent, which is why symbolic cultural assets become a main target. It is also intended to affect the particularly sensitive cultural memory, the growing cultural diversity and the economic basis (such as tourism) of a state, region or municipality.[68][69][70]

Another important issue today is the impact of tourism on the various forms of culture. On the one hand, this can be physical impact on individual objects or the destruction caused by increasing environmental pollution and, on the other hand, socio-cultural effects on society.[71][72][73]

See also

- Animal culture

- Anthropology

- Cultural area

- Cultural studies

- Cultural tourism

- Culture 21 – United Nations plan of action

- Honour § Cultures of honour and cultures of law

- Outline of culture

- Recombinant culture

- Semiotics of culture

References

- ^ Tylor, Edward. (1871). Primitive Culture. Vol 1. New York: J.P. Putnam’s Son

- ^ Jackson, Y. Encyclopedia of Multicultural Psychology, p. 203

- ^ Chigbu, Uchendu Eugene (November 24, 2014). «Repositioning culture for development: women and development in a Nigerian rural community». Community, Work & Family. 18 (3): 334–350. doi:10.1080/13668803.2014.981506. ISSN 1366-8803. S2CID 144448501. Archived from the original on July 30, 2022. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ Michael Obert (2013) Song from the Forest

- ^ a b Macionis, John J; Gerber, Linda Marie (2011). Sociology. Toronto: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-13-700161-3. OCLC 652430995.

- ^ Cicéron, Marcus Tullius Cicero; Bouhier, Jean (1812). Tusculanes (in French). Nismes: J. Gaude. p. 273. OCLC 457735057. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- ^ a b Velkley, Richard L (2002). «The Tension in the Beautiful: On Culture and Civilization in Rousseau and German Philosophy». Being after Rousseau: philosophy and culture in question. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 11–30. ISBN 978-0-226-85256-0. OCLC 47930775.

- ^ Sorrells, Kathryn (2015). Intercultural Communication: Globalization and Social Justice. Los Angeles: Sage. ISBN 978-1-4129-2744-4.[page needed]

- ^ Tylor 1974, 1.

- ^ James, Paul; Magee, Liam; Scerri, Andy; Steger, Manfred (2015). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. London: Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-138-02572-1. OCLC 942553107. Archived from the original on June 26, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ «Meaning of «culture»«. Cambridge English Dictionary. Archived from the original on August 15, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- ^ Pyszczynski, Tom; Solomon, Sheldon; Greenberg, Jeff (2015). Thirty Years of Terror Management Theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 52. pp. 1–70. doi:10.1016/bs.aesp.2015.03.001. ISBN 978-0-12-802247-4.

- ^ Greenberg, Jeff; Koole, Sander L.; Pyszczynski, Tom (2013). Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology. Guilford Publications. ISBN 978-1-4625-1479-3. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ^ Panikkar, Raimon (1991). Pathil, Kuncheria (ed.). Religious Pluralism: An Indian Christian Perspective. ISPCK. pp. 252–99. ISBN 978-81-7214-005-2. OCLC 25410539.

- ^ a b Rein, Raud (August 29, 2016). Meaning in Action: Outline of an Integral Theory of Culture. Cambridge: Polity. ISBN 978-1-5095-1124-2. OCLC 944339574.

- ^ Chigbu, Uchendu Eugene (July 3, 2015). «Repositioning culture for development: women and development in a Nigerian rural community». Community, Work & Family. 18 (3): 334–50. doi:10.1080/13668803.2014.981506. ISSN 1366-8803. S2CID 144448501.

- ^ O’Neil, Dennis (2006). «Culture Change: Processes of Change». Culture Change. Palomar College. Archived from the original on October 27, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2016.

- ^ Pringle, Heather (November 20, 1998). «The Slow Birth of Agriculture». Science. 282 (5393): 1446. doi:10.1126/science.282.5393.1446. ISSN 0036-8075. S2CID 128522781.

- ^ Wei, Clarissa (March 20, 2018). «Why China Loves American Chain Restaurants So Much». Eater. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Stephen Wolfram (May 16, 2017) A New Kind of Science: A 15-Year View Archived February 28, 2021, at the Wayback Machine As applied to the computational universe

- ^ Kant, Immanuel. 1784. «Answering the Question: What is Enlightenment?» (German: Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung?) Berlinische Monatsschrift, December (Berlin Monthly)

- ^ Eldridge, Michael. «The German Bildung Tradition». UNC Charlotte. Archived from the original on January 23, 2009. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ Underhill, James W. (2009). Humboldt, Worldview, and Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ Köpping, Klaus-Peter (2005). Adolf Bastian and the psychic unity of mankind. Lit Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8258-3989-5. OCLC 977343058.

- ^ Ellis, Ian. «Biography of Adolf Bastian, ethnologist». Today in Science History. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ Liron, Tal (2003). Franz Boas and the discovery of culture (PDF) (Thesis). OCLC 52888196. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 2, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ a b Arnold, Matthew (1869). «Culture and Anarchy». Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ Williams (1983), p. 90. Cited in Roy, Shuker (1997). Understanding popular music. Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-415-10723-5. OCLC 245910934. argues that contemporary definitions of culture fall into three possibilities or mixture of the following three:

- «a general process of intellectual, spiritual, and aesthetic development.»

- «a particular way of life, whether of a people, period or a group.»

- «the works and practices of intellectual and especially artistic activity.»

- ^ Bakhtin 1981, p. 4

- ^ Dunne, Timothy; Reus-Smit, Christian (2017). The globalization of international society. Oxford. pp. 102–121. ISBN 978-0-19-251193-5.

- ^ McClenon, pp. 528–29

- ^ Angioni, Giulio (1973). Tre saggi sull’antropologia dell’età coloniale (in Italian). OCLC 641869481.

- ^ Teslow, Tracy (March 10, 2016). Constructing race: the science of bodies and cultures in American anthropology. ISBN 978-1-316-60338-3. OCLC 980557304. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ «anthropology». Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020.

- ^ Fernandez, James W.; Hanchett, Suzanne L.; Jeganathan, Pradeep; Nicholas, Ralph W.; Robotham, Donald Keith; Smith, Eric A. (August 31, 2015). «anthropology | Britannica.com». Britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ «What is Anthropology? – Advance Your Career». American Anthropological Association. Archived from the original on October 26, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ Haviland, William A.; McBride, Bunny; Prins, Harald E.L.; Walrath, Dana (2011). Cultural Anthropology: The Human Challenge. Wadsworth/Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-81082-7. OCLC 731048150.

- ^ Lindström, Martin (2016). Small data: the tiny clues that uncover huge trends. London: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-1-250-08068-4. OCLC 921994909.

- ^ Simmel, Georg (1971). Levine, Donald N (ed.). Georg Simmel on individuality and social forms: selected writings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. xix. ISBN 978-0-226-75776-6. OCLC 951272809. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ Sokal, Alan D. (June 5, 1996). «A Physicist Experiments with Cultural Studies». Lingua Franca. Archived from the original on March 26, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2016. Physicist Alan Sokal published a paper in a journal of cultural sociology stating that gravity was a social construct that should be examined hermeneutically. See Sokal affair for further details.

- ^ Griswold, Wendy (1987). «A Methodological Framework for the Sociology of Culture». Sociological Methodology. 17: 1–35. doi:10.2307/271027. ISSN 0081-1750. JSTOR 271027.

- ^ Berlin, Isaiah; Ryan, Alan (2002). Karl Marx: His Life and Environment. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-19-510326-7. OCLC 611127754.

- ^ Williams, Raymond (1983), Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 87–93, 236–38, OCLC 906396817

- ^ Berger, John (1972). Ways of seeing. Peter Smithn. ISBN 978-0-563-12244-9. OCLC 780459348.

- ^ «Studying Culture – Reflections and Assessment: An Interview with Richard Hoggart». Media, Culture & Society. 13.

- ^ Adams, Tim (September 23, 2007). «Cultural hallmark». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ James, Procter (2004). Stuart Hall. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26267-5. OCLC 318376213.

- ^ Sardar, Ziauddin; Van Loon, Borin; Appignanesi, Richard (1994). Introducing Cultural Studies. New York: Totem Books. ISBN 978-1-84046-587-7. OCLC 937991291.

- ^ Fiske, John; Turner, Graeme; Hodge, Robert Ian Vere (1987). Myths of Oz: reading Australian popular culture. London: Allen and Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-330391-7. OCLC 883364628.

- ^ Bakhtin, Mikhail Mikhaĭlovich; Holquist, Michael (1981). The dialogic imagination four essays. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 4. OCLC 872436352. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ «Comparative Cultural Studies». Purdue University Press. 2015. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ Lindlof, Thomas R; Taylor, Bryan C (2002). Qualitative Communication Research Methods (2nd ed.). Sage. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-7619-2493-7. OCLC 780825710.

- ^ Gonick, Cy (February 7, 2006). «Marxism». The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ du Gay, Paul, ed. (1997). Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman. Sage. ISBN 978-0-7619-5402-6. OCLC 949857570. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ MacKenzie, Gina (August 21, 2018). «Julia Kristeva». Oxford Bibliographies. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Petrakis, Panagiotis; Kostis, Pantelis (December 1, 2013). «Economic growth and cultural change». The Journal of Socio-Economics. 47: 147–57. doi:10.1016/j.socec.2013.02.011.

- ^ a b Heine, Steven J. (2015). Cultural psychology. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Cognitive Science. Vol. 1 (Third ed.). New York, NY. pp. 254–266. doi:10.1002/wcs.7. ISBN 9780393263985. OCLC 911004797. PMID 26271239.

- ^ Myers, David G. (2010). Social psychology (Tenth ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 9780073370668. OCLC 667213323.

- ^ Norenzayan, Ara; Heine, Steven J. (September 2005). «Psychological universals: what are they and how can we know?». Psychological Bulletin. 131 (5): 763–784. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.5.763. ISSN 0033-2909. PMID 16187859.

- ^ Miyahara, Akira. «Toward Theorizing Japanese Communication Competence from a Non-Western Perspective». American Communication Journal. 3 (3).

- ^ McCrae, Robert R.; Costa, Paul T.; de Lima, Margarida Pedroso; Simões, António; Ostendorf, Fritz; Angleitner, Alois; Marušić, Iris; Bratko, Denis; Caprara, Gian Vittorio; Barbaranelli, Claudio; Chae, Joon-Ho; Piedmont, Ralph L. (1999). «Age differences in personality across the adult life span: Parallels in five cultures». Developmental Psychology. American Psychological Association (APA). 35 (2): 466–477. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.35.2.466. ISSN 1939-0599. PMID 10082017.

- ^ Cheung, F. M.; Leung, K.; Fan, R. M.; Song, W.S.; Zhang, J. X.; Zhang, H. P. (March 1996). «Development of the Chinese Personality Assessment Inventory». Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 27 (2): 181–199. doi:10.1177/0022022196272003. S2CID 145134209.

- ^ Baillargeon, Rene (2002), «The Acquisition of Physical Knowledge in Infancy: A Summary in Eight Lessons», Blackwell Handbook of Childhood Cognitive Development, Blackwell Publishers Ltd, pp. 47–83, doi:10.1002/9780470996652.ch3, ISBN 9780470996652

- ^ Heine, Steven J.; Kitayama, Shinobu; Lehman, Darrin R. (2001). «Cultural Differences in Self-Evaluation». Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 32 (4): 434–443. doi:10.1177/0022022101032004004. ISSN 0022-0221. S2CID 40475406.

- ^ Roger O’Keefe, Camille Péron, Tofig Musayev, Gianluca Ferrari «Protection of Cultural Property. Military Manual.» UNESCO, 2016, p 73.

- ^ UNESCO Director-General calls for stronger cooperation for heritage protection at the Blue Shield International General Assembly. UNESCO, September 13, 2017.

- ^ «UNESCO Legal Instruments: Second Protocol to the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict 1999». Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Gerold Keusch «Kulturschutz in der Ära der Identitätskriege» In: Truppendienst — Magazin des Österreichischen Bundesheeres, October 24, 2018.

- ^ «Karl von Habsburg auf Mission im Libanon» (in German). April 28, 2019. Archived from the original on May 26, 2020. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ Corine Wegener; Marjan Otter (Spring 2008), «Cultural Property at War: Protecting Heritage during Armed Conflict», The Getty Conservation Institute Newsletter, The Getty Conservation Institute, vol. 23, no. 1;

Eden Stiffman (May 11, 2015), «Cultural Preservation in Disasters, War Zones. Presents Big Challenges», The Chronicle Of Philanthropy;

Hans Haider (June 29, 2012), «Missbrauch von Kulturgütern ist strafbar», Wiener Zeitung - ^ Shepard, Robert (August 2002). «Commodification, culture and tourism». Tourist Studies. 2 (2): 183–201. doi:10.1177/146879702761936653. S2CID 55744323.

- ^ Coye, N. dir. (2011), Lascaux et la conservation en milieu souterrain: actes du symposium international (Paris, 26-27 fév. 2009) = Lascaux and Preservation Issues in Subterranean Environments: Proceedings of the International Symposium (Paris, February 26 and 27), Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 360 p.

- ^ Jaafar, Mastura; Rasoolimanesh, S Mostafa; Ismail, Safura (2017). «Perceived sociocultural impacts of tourism and community participation: A case study of Langkawi Island». Tourism and Hospitality Research. 17 (2): 123–134. doi:10.1177/1467358415610373. S2CID 157784805.

Further reading

Books

- Barker, C. (2004). The Sage dictionary of cultural studies. Sage.

- Terrence Deacon (1997). The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. New York and London: W.W. Norton. ISBN 9780393038385.

- Ralph L. Holloway Jr. (1969). «Culture: A Human domain». Current Anthropology. 10 (4): 395–412. doi:10.1086/201036. S2CID 144502900.

- Dell Hymes (1969). Reinventing Anthropology.

- James, Paul; Szeman, Imre (2010). Globalization and Culture, Vol. 3: Global-Local Consumption. London: Sage Publications.

- Michael Tomasello (1999). «The Human Adaptation for Culture». Annual Review of Anthropology. 28: 509–29. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.28.1.509.

- Whorf, Benjamin Lee (1941). «The relation of habitual thought and behavior to language». Language, Culture, and Personality: Essays in Honor of Edward Sapir.

- Walter Taylor (1948). A Study of Archeology. Memoir 69, American Anthropological Association. Carbondale IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

- «Adolf Bastian», Encyclopædia Britannica Online, January 27, 2009

- Ankerl, Guy (2000) [2000]. Global communication without universal civilization, vol.1: Coexisting contemporary civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. INU societal research. Geneva: INU Press. ISBN 978-2-88155-004-1.

- Arnold, Matthew. 1869. Culture and Anarchy. Archived November 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine New York: Macmillan. Third edition, 1882, available online. Retrieved: 2006-06-28.

- Bakhtin, M.M. (1981) The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Ed. Michael Holquist. Trans. Caryl Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06445-6.

- Barzilai, Gad. 2003. Communities and Law: Politics and Cultures of Legal Identities University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-11315-1

- Benedict, Ruth (1934). Patterns of Culture. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29164-4

- Michael C. Carhart, The Science of Culture in Enlightenment Germany, Cambridge, Harvard University press, 2007.

- Cohen, Anthony P. 1985. The Symbolic Construction of Community. Routledge: New York,

- Dawkins, R. 1982. The Extended Phenotype: The Long Reach of the Gene. Paperback ed., 1999. Oxford Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-19-288051-2

- Findley & Rothney. Twentieth-Century World (Houghton Mifflin, 1986)

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York. ISBN 978-0-465-09719-7.

- Geertz, Clifford (1957). «Ritual and Social Change: A Javanese Example». American Anthropologist. 59: 32–54. doi:10.1525/aa.1957.59.1.02a00040.

- Goodall, J. 1986. The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-11649-8

- Hoult, T.F., ed. 1969. Dictionary of Modern Sociology. Totowa, New Jersey, United States: Littlefield, Adams & Co.

- Jary, D. and J. Jary. 1991. The HarperCollins Dictionary of Sociology. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-271543-7

- Keiser, R. Lincoln 1969. The Vice Lords: Warriors of the Streets. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. ISBN 978-0-03-080361-1.

- Kroeber, A.L. and C. Kluckhohn, 1952. Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum

- Kim, Uichol (2001). «Culture, science and indigenous psychologies: An integrated analysis.» In D. Matsumoto (Ed.), Handbook of culture and psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- McClenon, James. «Tylor, Edward B(urnett)». Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Ed. William Swatos and Peter Kivisto. Walnut Creek: AltaMira, 1998. 528–29.

- Middleton, R. 1990. Studying Popular Music. Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 978-0-335-15275-9.

- O’Neil, D. 2006. Cultural Anthropology Tutorials Archived December 4, 2004, at the Wayback Machine, Behavioral Sciences Department, Palomar College, San Marco, California. Retrieved: 2006-07-10.

- Reagan, Ronald. «Final Radio Address to the Nation» Archived January 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, January 14, 1989. Retrieved June 3, 2006.

- Reese, W.L. 1980. Dictionary of Philosophy and Religion: Eastern and Western Thought. New Jersey U.S., Sussex, U.K: Humanities Press.

- Tylor, E.B. (1974) [1871]. Primitive culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art, and custom. New York: Gordon Press. ISBN 978-0-87968-091-6.

- UNESCO. 2002. Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity, issued on International Mother Language Day, February 21, 2002. Retrieved: 2006-06-23.

- White, L. 1949. The Science of Culture: A study of man and civilization. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Wilson, Edward O. (1998). Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. Vintage: New York. ISBN 978-0-679-76867-8.

- Wolfram, Stephen. 2002 A New Kind of Science. Wolfram Media, Inc. ISBN 978-1-57955-008-0.

Articles

- The Meaning of «Culture» (2014-12-27), Joshua Rothman, The New Yorker

External links

- Cultura: International Journal of Philosophy of Culture and Axiology

- What is Culture?

An artifact of «high culture»: a painting by Edgar Degas.

The word culture, from the Latin root colere (to inhabit, to cultivate, or to honor), generally refers to patterns of human activity and the symbolic structures that give such activity significance. Different definitions of «culture» reflect different theoretical orientations for understanding, or criteria for valuing, human activity. Anthropologists most commonly use the term «culture» to refer to the universal human capacity to classify, codify, and communicate their experiences symbolically.

Society and culture are similar concepts, but their scopes are different. A society is an interdependent community, while culture is an attribute of a community: The complex web of shifting patterns that link individuals together. Civilization, also, is closely connected to culture, and has often been used almost synonymously with culture. This is because civilization and culture are different aspects of a single entity. Civilization can be viewed as the external manifestation, and culture as the internal character of a society. Thus, civilization is expressed in physical attributes, such as toolmaking, agriculture, technology, and so forth while culture refers to the social standards and norms of behavior, the traditions, values, and religious beliefs and practices that are held in common by members of the society. Culture is also manifest, however, through the arts as well as in the social structures and institutions of the society.

Defining culture

Culture is a complex of features held by a social group, which may be as small as a family or a tribe, or as large as a racial or ethnic group, a nation, or in the age of globalization, by people all over the world. Culture has been called «the way of life for an entire society.» As such, it includes codes of manners, dress, language, religion, rituals, norms of behavior such as law and morality, and systems of belief.[1] The elements of culture are first adopted by members of the social group, found to be useful, and then transmitted or propagated to others. In this way, culture is both defined by the social activities of the group and also defines the behavior of the members of the society. Culture, however, is not fixed or static; rather, it involves a dynamic process as people respond to changing conditions and challenges.

Different definitions of culture reflect different theories for understanding, or criteria for valuing, human activity.

Edward Burnett Tylor wrote, in 1871, that «culture or civilization, taken in its wide ethnographic sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.»[2]

The United Nations agency UNESCO has defined culture as the «set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual, and emotional features of society or a social group, and that it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs.»[3]

Another common way of understanding culture sees it as consisting of three elements: Values, norms, and artifacts.[4] Values comprise ideas about what in life seems important. They guide the rest of the culture. Norms consist of expectations of how people will behave in different situations. Each culture has different methods, or «sanctions,» of enforcing its norms. Sanctions vary with the importance of the norm; norms that a society enforces formally have the status of laws. Artifacts—things, or material culture—derive from the culture’s values and norms.

Julian Huxley gives a slightly different categorization of culture, dividing it into three inter-related subgroups—»mentifacts,» «sociofacts,» and «artifacts»—standing for ideological, sociological, and technological subsystems respectively. Mentifacts are mental manifestations of culture—different ideas, beliefs, and knowledge and the ways in which these things are expressed in speech or other forms of communication. Socialization depends on the belief subsystem, that is, on mentifacts. The way people interact with each other, and the types of relationship they form, depends greatly on the dominant cultural belief systems. However, at the same time, the sociological subsystem governs interactions between people and influences the formation of mentifacts. That is to say, the quality of human interactions influences the formation of new ideas and beliefs that form cultural mentifacts. Material objects and their use make up the technological subsystem of culture, which is also strongly interconnected with other two subsystems.[5]

In the early twentieth century, anthropologists regarded culture not as a set of discrete products or activities (whether material or symbolic), but rather as the underlying patterns that are reflected in those products and activities. Thus, patterns of relationship among people (husband and wife, co-workers in a company, and so on) reflect the social structure of a particular society (social roles). On the other hand, art and myth also reflect patterns from the worldview of a particular society. Both patterns of social structure and patterns of worldview form what characterizes a culture.

The symbolic view of culture, the legacy of Clifford Geertz and Victor Turner, holds symbols to be both the practices of social actors and the context that gives such practices meaning. Anthony P. Cohen wrote of the «symbolic gloss» which allows social actors to use common symbols to communicate and understand each other while still imbuing these symbols with personal significance and meanings.[6] Symbols provide the limits of cultured thought. Members of a culture rely on these symbols to frame their thoughts and expressions in intelligible terms. In short, symbols make culture possible, reproducible, and readable. They are the «webs of significance» in Weber’s sense that, to quote Pierre Bourdieu, «give regularity, unity and systematicity to the practices of a group.»[7]

In addition, sociobiological theory argues that observers can best understand many aspects of culture in the light of the concept of the meme, first introduced by Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book, The Selfish Gene. Dawkins has suggested the existence of units of culture—memes—roughly analogous to genes in evolutionary biology. They are the scripts of culture, repeatable, and transferable through imitation of another’s actions, through instruction by others through demonstration or through the medium of language, even through reading what was written in detail by others. Although this view has gained some popular currency, anthropologists have generally rejected it.

While these definitions range widely, they still do not exhaust the many uses of this concept. In 1952, Alfred L. Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn compiled a list of more than 200 different definitions of culture in their book, Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. They organized these diverse concepts of culture into eight categories:[8]

- Topical: A list of topics such as social structure, religion, economic system, and so forth

- Historical: Social heritage, or tradition, passed from generation to generation

- Behavioral: Shared, learned human behavior, a way of life

- Normative: Ideals, values, norms, or standards for life

- Functional: The way people solve problems and adapt to their environment

- Mental: Complex of ideas, or learned habits, that distinguish people from animals

- Structural: Patterned and interrelated ideas, symbols, or behaviors

- Symbolic: Arbitrarily assigned meanings that are shared by a society

Finally, Kluckhohn suggested that «Culture is to society what memory is to individuals.»[9] Thus, culture can be viewed as the collection of information, experiences, ideas, and so forth that were found useful, widely adopted, and considered worth transmitting to future generations.

One of the main questions in measuring cultural development has always been in which norms can that development be measured. There are more than 6,000 communities in the world, and as many different languages. Such diversity naturally led toward the development of different beliefs, values, practices, and visions that each of those communities possess, and consequently toward different expressions of those values and beliefs—through the development of material, tangible things: Arts, crafts, architecture, means of transportation, and so forth.

Models of cultural development produced until the 1970s frequently measured cultural development exclusively in terms of material, tangible development—number and quality of housing, industrial development, visible arts, and so forth. As a consequence of an application of those models, Western cultures were seen as more advanced, while all others were regarded as more primitive. Modern developmental models go beyond mere economic growth. UNESCO today in the definition of culture includes means of achievement of satisfactory intellectual, emotional, moral, and spiritual existence. Cultural development is thus not measured only by the development of material tangibles (although those are considered important parts of it), but also by the lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs that certain culture produces.

Views of culture

As a rule, archaeologists focus on material culture whereas cultural anthropologists focus on symbolic culture, although ultimately both groups maintain interests in the relationships between these two dimensions. Moreover, anthropologists understand «culture» to refer not only to material, consumption goods, but to the general processes which produce such goods and give them meaning, and to the social relationships and practices in which such objects and processes become embedded.

Culture and religion

Painting of Persian women musicians from Hasht-Behesht Palace («Palace of the 8 heavens»).

Religion and other belief systems are integral to a culture. Religion often codifies behavior, such as with the 10 Commandments of Judaism and Christianity or the five precepts of Buddhism. Sometimes it is involved with government, as in a theocracy. It also influences the arts.

The values and history of the Jewish people are a major part of the foundation of other Abrahamic religions such as Christianity, Islam, as well as the Bahá’í Faith. However, while sharing a heritage from Abraham, each has distinct traditions in the arts. Some of these also include are regional influences, but there are several norms or forms of cultural expression that are particular to these religions.

Christianity was the dominant feature in shaping modern European and the New World cultures. Modern philosophical thought has very much been influenced by Christian philosophers such as St. Thomas Aquinas and Erasmus and Christian cathedrals like Notre Dame de Paris, Wells Cathedral, and Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral have been noted as architectural wonders.

Islam’s influence has dominated much of the North African, Middle, and Far East regions for 1500 years, sometimes mixed with other religions. For example Islam’s influence can be seen in diverse philosophies such as Ibn Bajjah, Ibn Tufail, Ibn Khaldun, and Averroes as well as poetic stories and literature like Hayy ibn Yaqdhan, The Madman of Layla, The Conference of the Birds, and the Masnavi in addition to art and architecture such as the Umayyad Mosque, Dome of the Rock, Faisal Mosque, Hagia Sophia (which has been both a cathedral and a mosque), and the many styles of Arabesque.

Philosophy and religion are often closely interwoven in Eastern thought. Many Asian religious and philosophical traditions originated in India and China and spread across Asia through cultural diffusion and the migration of peoples. Hinduism is the wellspring of Buddhism, the Mahāyāna branch of which spread north and eastwards from India into Tibet, China, Mongolia, Japan, and Korea, and south from China into Vietnam. Theravāda Buddhism spread throughout Southeast Asia, including Sri Lanka, parts of southwest China, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand.

Hindu philosophy from India contains elements of non-material pursuits, whereas another school of thought from India, Carvaka, preached the enjoyment of material world. Confucianism and Taoism, both of which originated in China have had pervasive influence on both religious and philosophical traditions, as well as statecraft and the arts throughout Asia.

Folk religions practiced by tribal groups are common in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Their influence can be considerable; may pervade the culture and even become the state religion, as with Shintoism. Like the other major religions, folk religion answers human needs for reassurance in times of trouble, healing, averting misfortune, and providing rituals that address the major passages and transitions in human life.

Culture as civilization

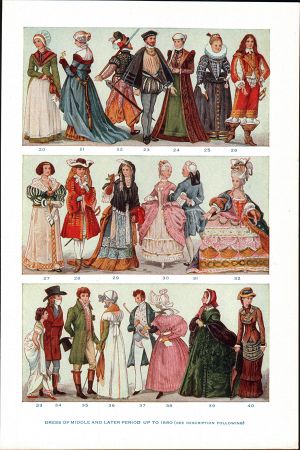

European high fashion from 1500 to 1880

The term «civilization» has been used almost synonymously with culture. This is because civilization and culture are different aspects of a single entity. Civilization can be viewed as the external manifestation, and culture as the internal character of a society. Thus, civilization is expressed in physical attributes, such as toolmaking, agriculture, buildings, technology, urban planning, social structure, social institutions, and so forth. Culture, on the other hand, refers to the social standards and norms of behavior, the traditions, values, ethics, morality, and religious beliefs and practices that are held in common by members of the society.

Many people today use a conception of «culture» that developed in Europe during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. This view of culture reflected inequalities within European societies, and between European powers and their colonies around the world. It identifies «culture» with «civilization.» According to this thinking, one can classify some countries as more «civilized» than others, and some people as more «cultured» than others. Theorists like Matthew Arnold and F.R. Leavis have regarded culture as simply the result of «the best that has been thought and said in the world (Arnold, 1960, p. 6), thus labeling anything that doesn’t fit into this category as uncivilized. On this account, culture links closely with social «cultivation»—the progressive refinement of human behavior.

European Classical musician

In practice, however, culture has often referred to elite activities and goods, such as haute cuisine, high fashion, museum-caliber art, and European classical music. The word «cultured» described people who knew about, and took part in, these activities. For example, someone who used «culture» in the sense of «cultivation» might argue that European classical music is more refined than music produced by working-class people such as punk rock, or than the indigenous musical traditions of aboriginal peoples of, for example, Australia.

People who use «culture» in this way tend not to use it in the plural as «cultures.» They do not believe that distinct cultures exist, each with their own internal logic or values, but rather that only a single standard of refinement suffices, against which one can measure all groups.

Thus, in this view, people with different customs from those who regard themselves as cultured are not considered as «having a different culture,» but rather as as «uncultured.» People lacking «culture» often seemed more «natural,» and observers often defended (or criticized) elements of high culture for repressing human nature.

From the eighteenth century onwards, some social critics have accepted this contrast between cultured and uncultured, but have stressed the interpretation of refinement and of sophistication as corrupting and unnatural developments which obscure and distort people’s essential nature. On this account, folk music (as produced by working-class people) is seen as honestly expressing a natural way of life, and classical music is regarded as superficial and decadent. Equally, this view often portrays non-Western people as «noble savages,» living authentic, unblemished lives, uncomplicated and uncorrupted by the highly-stratified capitalist systems of western culture.

Gothic fashion popular in Europe in the late twentieth century

By the end of the twentieth century, most social scientists rejected the monadic conception of culture, and the opposition of culture (nurture) to innate nature. They recognized all groups as cultured, just cultured in a different way. Thus, social observers contrasted the «high culture» of the élite to the «popular culture» or «pop culture»—goods and activities produced for, and consumed by, the masses.

Culture as worldview

During the Romantic era, scholars in Germany, especially those concerned with nationalist movements—such as the nationalist struggle to unite «Germany» out of numerous smaller entities, and the nationalist struggles by ethnic minorities against the Austro-Hungarian Empire—developed a more inclusive notion of culture as «worldview.» In this mode of thought, a distinct and incommensurable worldview characterizes each ethnic group. Although more inclusive than earlier views, this approach to culture still allowed for distinctions between «civilized» and «primitive» or «tribal» cultures.

By the late nineteenth century, anthropologists had adopted and adapted the term «culture» to a broader definition that they could apply to a wider variety of societies. Attentive to the theory of evolution, they assumed that all human beings evolved equally, and that the fact that all humans have cultures must in some way result from human evolution. They also started to use biological evolution to explain differences between specific cultures—an approach that either exemplified a form of, or legitimized forms of, racism. They believed that biological evolution would produce a most inclusive notion of culture, a concept that anthropologists could apply equally to non-literate and to literate societies, or to nomadic and to sedentary societies. They argued that through the course of their evolution, human beings evolved a universal human capacity to classify experiences, and to encode and communicate them symbolically. Since human individuals learned and taught these symbolic systems, the systems began to develop independently of biological evolution (in other words, one human being can learn a belief, value, or way of doing something from another, even if the two humans do not share a biological relationship). That this capacity for symbolic thinking and social learning stems from human evolution confounds older arguments about nature versus nurture. Thus, Clifford Geertz has argued that human physiology and neurology developed in conjunction with the first cultural activities, and Middleton concluded that «human instincts were culturally formed.»[10]

People living apart from one another develop unique cultures, but elements of different cultures can easily spread from one group of people to another. Culture changes dynamically and people teach and learn culture, making it a potentially rapid form of adaptation to change in physical conditions. Anthropologists view culture as not only as a product of biological evolution, but as a supplement to it, as the main means of human adaptation to the world.

This view of culture as a symbolic system with adaptive functions, and one which varies from place to place, led anthropologists to conceive of different cultures as defined by distinct patterns (or structures) of enduring, arbitrary, conventional sets of meaning, which took concrete form in a variety of artifacts such as myths, rituals, tools, the design of housing, the planning of villages, and so on. Anthropologists thus distinguish between «material culture» and «symbolic culture,» not only because each reflects different kinds of human activity, but also because they constitute different kinds of data that require different methodologies.

This view of culture, which came to dominate between World War I and World War II, implied that each culture had bounds and demanded interpretation as a whole, on its own terms. This resulted in a belief in «cultural relativism:» The belief that one had to understand an individual’s actions in terms of his or her culture, or that one had to understand a specific cultural artifact or a ritual in terms of the larger symbolic system of which it forms a part.

Culture as consumption goods

Cell phones on display in a store.

Cultural studies developed in the late twentieth century, in part through the re-introduction of Marxist thought into sociology, and in part through the process of articulation of sociology and other academic disciplines, such as literary criticism. The cultural studies movement aimed to focus on the analysis of subcultures in industrial or capitalist societies. This movement generally focused on the study of consumption goods (such as fashion, art, and literature). However, because the eighteenth and nineteenth century distinction between «high» and «low» culture seemed inappropriate to apply to the mass-produced and mass-marketed consumption goods which cultural studies analyzes, these scholars used instead the term «popular culture.»

Today, some anthropologists have joined the project of cultural studies. Most, however, reject the identification of culture with consumption goods. Furthermore, many now reject the notion of culture as bounded, and consequently reject the notion of subculture. Instead, they see culture as a complex web of shifting patterns that link people in different locales and that link social formations of different scales. According to this view, any group can construct its own cultural identity.

Subcultures

Historically, in the case of smaller societies, in which people merely fell into categories of age, gender, household, and descent group, anthropologists believed that people more or less shared the same set of values and conventions. People in such societies remained strongly connected to their common culture. In the case of larger societies, in which people undergo further categorization by region, race, ethnicity, and social class, anthropologists came to believe that members of the same society often had highly contrasting values and conventions. Thus, they used the term «subculture» to identify the cultures of parts of larger societies.

Large societies often have subcultures, or groups of people with distinct sets of behavior and beliefs that differentiate them from a larger culture of which they are a part. The subculture may be distinctive because of the age of its members, or by their race, ethnicity, social class, or gender. The qualities that determine a subculture as distinct may be aesthetic, religious, occupational, political, sexual, or a combination of these factors.

Immigrant cultures

In dealing with immigrant groups and their cultures, there are essentially four approaches:

- Monoculturalism: In some European states, culture is very closely linked to nationalism, thus government policy is to assimilate immigrants, although recent increases in migration have led many European states to experiment with forms of multiculturalism.

- Leitkultur (core culture): A model developed in Germany by Bassam Tibi. The idea is that minorities can have an identity of their own, but they should at least support the core concepts of the culture on which the society is based.

- Melting Pot: In the United States, the traditional view has been one of a melting pot where all the immigrant cultures are mixed and amalgamated without state intervention.

- Multiculturalism: A policy that immigrants and others should preserve their cultures with the different cultures interacting peacefully within one nation.

The way nation states treat immigrant cultures rarely falls neatly into one or another of the above approaches. The degree of difference with the host culture, their «foreignness,» the number of immigrants, attitudes of the resident population, the type of government policies that are enacted, and the effectiveness of those policies all make it difficult to generalize about the effects. Similarly with other subcultures within a society, attitudes of the mainstream population and communications between various cultural groups play a major role in determining outcomes.

Cultural change

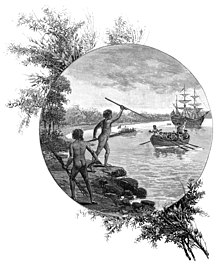

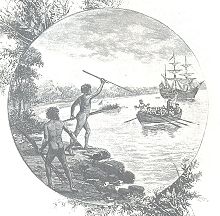

A nineteenth century engraving showing Australian «natives» opposing the arrival of Captain James Cook in 1770.

When it comes to change, cultures both embrace and resist change. For example, the role of women in Western cultures faced serious challenges in the twentieth century, and changes were at first met with great resistance. However, once the changes had been implemented, many non-Western cultures wanted to embrace the positive aspects of this change into their own cultures. Thus, there are both dynamic influences that encourage acceptance of new things, and conservative forces that resist change.

Three kinds of influence cause both change and resistance to it:

- Forces at work within a society

- Contact between societies

- Changes in the natural environment.[11]

Cultural change can come about due to the environment, to inventions (and other internal influences), and to contact with other cultures. For example, the end of the last ice age witnessed the invention of agriculture, which in turn brought about many cultural innovations (such as new rituals and customs that were agriculture-centered), that further changed how people related to nature and, ultimately, to each other.

Additionally, the fact that culture comprises symbolical codes and can thus pass via teaching from one person to another means that cultures, although bounded, can and do change through social interaction. Cultural change can result from invention and innovation, or from contact between two cultures through acculturation. Under peaceful conditions, contact between two cultures can lead to people learning from one another («diffusion» or «transculturation»). Under conditions of violence or political inequality, however, people of one society «steal» cultural artifacts from another, or impose cultural artifacts on another.