Culture

Afrikaans:

kultuur

Albanian:

kulturën

Amharic:

ባህል

Arabic:

حضاره

Armenian:

մշակույթ

Azerbaijani:

mədəniyyət

Basque:

kultura

Belarusian:

культуры

Bengali:

সংস্কৃতি

Bosnian:

kultura

Bulgarian:

култура

Catalan:

cultura

Cebuano:

kultura

Chinese (Simplified):

文化

Chinese (Traditional):

文化

Corsican:

cultura

Croatian:

kultura

Czech:

kultura

Danish:

kultur

Dutch:

cultuur

English:

culture

Esperanto:

kulturo

Estonian:

kultuur

Finnish:

kulttuuri

French:

culture

Frisian:

kultuer

Galician:

cultura

Georgian:

კულტურა

German:

kultur

Greek:

πολιτισμός

Gujarati:

સંસ્કૃતિ

Haitian Creole:

kilti

Hausa:

al’ada

Hawaiian:

moʻomeheu

Hebrew:

תַרְבּוּת

Hindi:

संस्कृति

Hmong:

kab lis kev cai

Hungarian:

kultúra

Icelandic:

menningu

Igbo:

omenala

Indonesian:

budaya

Irish:

cultúr

Italian:

cultura

Japanese:

文化

Javanese:

budaya

Kannada:

ಸಂಸ್ಕೃತಿ

Kazakh:

мәдениет

Khmer:

វប្បធម៌

Korean:

문화

Kurdish:

çande

Kyrgyz:

маданият

Lao:

ວັດທະນະ ທຳ

Latin:

cultura

Latvian:

kultūru

Lithuanian:

kultūra

Luxembourgish:

kultur

Macedonian:

култура

Malagasy:

kolontsaina

Malay:

budaya

Malayalam:

സംസ്കാരം

Maltese:

kultura

Maori:

ahurea

Marathi:

संस्कृती

Mongolian:

соёл

Myanmar (Burmese):

ယဉ်ကျေးမှု

Nepali:

संस्कृति

Norwegian:

kultur

Nyanja (Chichewa):

chikhalidwe

Pashto:

کلتور

Persian:

فرهنگ

Polish:

kultura

Portuguese (Portugal, Brazil):

cultura

Punjabi:

ਸਭਿਆਚਾਰ

Romanian:

cultură

Russian:

культура

Samoan:

aganuu

Scots Gaelic:

cultar

Serbian:

културе

Sesotho:

setso

Shona:

tsika nemagariro

Sindhi:

ثقافت

Sinhala (Sinhalese):

සංස්කෘතිය

Slovak:

kultúra

Slovenian:

kulture

Somali:

dhaqanka

Spanish:

cultura

Sundanese:

budaya

Swahili:

utamaduni

Swedish:

kultur

Tagalog (Filipino):

kultura

Tajik:

фарҳанг

Tamil:

கலாச்சாரம்

Telugu:

సంస్కృతి

Thai:

วัฒนธรรม

Turkish:

kültür

Ukrainian:

культури

Urdu:

ثقافت

Uzbek:

madaniyat

Vietnamese:

văn hóa

Welsh:

diwylliant

Xhosa:

inkcubeko

Yiddish:

קולטור

Yoruba:

asa

Zulu:

isiko

Click on a letter to browse words starting with that letter in English

Features

Free to use

This word translator is absolutely free, no registration is required and there is no usage limit.

Online

This translator is based in the browser, no software installation is required.

All devices supported

See word translations on any device that has a browser: mobile phones, tablets and desktop computers.

Home

About

Blog

Contact Us

Log In

Sign Up

Follow Us

Our Apps

Home>Words that start with C>culture

How to Say Culture in Different LanguagesAdvertisement

Categories:

General

Please find below many ways to say culture in different languages. This is the translation of the word «culture» to over 100 other languages.

Saying culture in European Languages

Saying culture in Asian Languages

Saying culture in Middle-Eastern Languages

Saying culture in African Languages

Saying culture in Austronesian Languages

Saying culture in Other Foreign Languages

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

Saying Culture in European Languages

| Language | Ways to say culture | |

|---|---|---|

| Albanian | kulturë | Edit |

| Basque | kultura | Edit |

| Belarusian | культура | Edit |

| Bosnian | kultura | Edit |

| Bulgarian | култура | Edit |

| Catalan | cultura | Edit |

| Corsican | cultura | Edit |

| Croatian | Kultura | Edit |

| Czech | kultura | Edit |

| Danish | kultur | Edit |

| Dutch | cultuur | Edit |

| Estonian | kultuur | Edit |

| Finnish | kulttuuri | Edit |

| French | Culture | Edit |

| Frisian | kultuer | Edit |

| Galician | cultura | Edit |

| German | Kultur | Edit |

| Greek | Πολιτισμός [Politismós] |

Edit |

| Hungarian | kultúra | Edit |

| Icelandic | Menning | Edit |

| Irish | cultúr | Edit |

| Italian | cultura | Edit |

| Latvian | kultūra | Edit |

| Lithuanian | kultūra | Edit |

| Luxembourgish | Kultur | Edit |

| Macedonian | култура | Edit |

| Maltese | kultura | Edit |

| Norwegian | kultur | Edit |

| Polish | kultura | Edit |

| Portuguese | cultura | Edit |

| Romanian | cultură | Edit |

| Russian | культура [kul’tura] |

Edit |

| Scots Gaelic | cultar | Edit |

| Serbian | култура [kultura] |

Edit |

| Slovak | kultúra | Edit |

| Slovenian | kultura | Edit |

| Spanish | cultura | Edit |

| Swedish | kultur | Edit |

| Tatar | культурасы | Edit |

| Ukrainian | культура [kul’tura] |

Edit |

| Welsh | diwylliant | Edit |

| Yiddish | קולטור | Edit |

Saying Culture in Asian Languages

| Language | Ways to say culture | |

|---|---|---|

| Armenian | մշակույթ | Edit |

| Azerbaijani | mədəniyyət | Edit |

| Bengali | সংস্কৃতি | Edit |

| Chinese Simplified | 文化 [wénhuà] |

Edit |

| Chinese Traditional | 文化 [wénhuà] |

Edit |

| Georgian | კულტურა | Edit |

| Gujarati | સંસ્કૃતિ | Edit |

| Hindi | संस्कृति | Edit |

| Hmong | kab lis kev cai | Edit |

| Japanese | 文化 | Edit |

| Kannada | ಸಂಸ್ಕೃತಿ | Edit |

| Kazakh | мәдениет | Edit |

| Khmer | វប្បធម៍ | Edit |

| Korean | 문화 [munhwa] |

Edit |

| Kyrgyz | маданият | Edit |

| Lao | ວັດທະນະທໍາ | Edit |

| Malayalam | സംസ്കാരം | Edit |

| Marathi | संस्कृती | Edit |

| Mongolian | соёл | Edit |

| Myanmar (Burmese) | ယဉျကြေးမှု | Edit |

| Nepali | संस्कृति | Edit |

| Odia | ସଂସ୍କୃତି | Edit |

| Pashto | کلتور | Edit |

| Punjabi | ਸਭਿਆਚਾਰ | Edit |

| Sindhi | ثقافت | Edit |

| Sinhala | සංස්කෘතිය | Edit |

| Tajik | маданият | Edit |

| Tamil | கலாச்சாரம் | Edit |

| Telugu | సంస్కృతి | Edit |

| Thai | วัฒนธรรม | Edit |

| Turkish | kültür | Edit |

| Turkmen | medeniýeti | Edit |

| Urdu | ثقافت | Edit |

| Uyghur | مەدەنىيەت | Edit |

| Uzbek | madaniyat | Edit |

| Vietnamese | nền văn hóa | Edit |

Too many ads and languages?

Sign up to remove ads and customize your list of languages

Sign Up

Saying Culture in Middle-Eastern Languages

| Language | Ways to say culture | |

|---|---|---|

| Arabic | حضاره [hidaruh] |

Edit |

| Hebrew | תַרְבּוּת | Edit |

| Kurdish (Kurmanji) | çande | Edit |

| Persian | فرهنگ | Edit |

Saying Culture in African Languages

| Language | Ways to say culture | |

|---|---|---|

| Afrikaans | kultuur | Edit |

| Amharic | ባህል | Edit |

| Chichewa | chikhalidwe | Edit |

| Hausa | al’ada | Edit |

| Igbo | omenala | Edit |

| Kinyarwanda | umuco | Edit |

| Sesotho | setso | Edit |

| Shona | tsika nemagariro | Edit |

| Somali | dhaqanka | Edit |

| Swahili | utamaduni | Edit |

| Xhosa | inkcubeko | Edit |

| Yoruba | asa | Edit |

| Zulu | isiko | Edit |

Saying Culture in Austronesian Languages

| Language | Ways to say culture | |

|---|---|---|

| Cebuano | kultura | Edit |

| Filipino | kultura | Edit |

| Hawaiian | moʻomeheu | Edit |

| Indonesian | budaya | Edit |

| Javanese | budaya | Edit |

| Malagasy | kolontsaina | Edit |

| Malay | budaya | Edit |

| Maori | ahurea | Edit |

| Samoan | aganuu | Edit |

| Sundanese | budaya | Edit |

Saying Culture in Other Foreign Languages

| Language | Ways to say culture | |

|---|---|---|

| Esperanto | kulturo | Edit |

| Haitian Creole | kilti | Edit |

| Latin | cultura | Edit |

Dictionary Entries near culture

- cultural significance

- cultural tradition

- cultural values

- culture

- cultured

- culvert

- cum

Cite this Entry

«Culture in Different Languages.» In Different Languages, https://www.indifferentlanguages.com/words/culture. Accessed 12 Apr 2023.

Copy

Copied

Browse Words Alphabetically

Religion and expressive art are important aspects of human culture.

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.[1] Culture is often originated from or attributed to a specific region or location.

Humans acquire culture through the learning processes of enculturation and socialization, which is shown by the diversity of cultures across societies.

A cultural norm codifies acceptable conduct in society; it serves as a guideline for behavior, dress, language, and demeanor in a situation, which serves as a template for expectations in a social group.

Accepting only a monoculture in a social group can bear risks, just as a single species can wither in the face of environmental change, for lack of functional responses to the change.[2]

Thus in military culture, valor is counted a typical behavior for an individual and duty, honor, and loyalty to the social group are counted as virtues or functional responses in the continuum of conflict. In the practice of religion, analogous attributes can be identified in a social group.

Cultural change, or repositioning, is the reconstruction of a cultural concept of a society.[3] Cultures are internally affected by both forces encouraging change and forces resisting change. Cultures are externally affected via contact between societies.

Organizations like UNESCO attempt to preserve culture and cultural heritage.

Description

Pygmy music has been polyphonic well before their discovery by non-African explorers of the Baka, Aka, Efe, and other foragers of the Central African forests, in the 1200s, which is at least 200 years before polyphony developed in Europe. Note the multiple lines of singers and dancers. The motifs are independent, with theme and variation interweaving.[4] This type of music is thought to be the first expression of polyphony in world music.

Culture is considered a central concept in anthropology, encompassing the range of phenomena that are transmitted through social learning in human societies. Cultural universals are found in all human societies. These include expressive forms like art, music, dance, ritual, religion, and technologies like tool usage, cooking, shelter, and clothing. The concept of material culture covers the physical expressions of culture, such as technology, architecture and art, whereas the immaterial aspects of culture such as principles of social organization (including practices of political organization and social institutions), mythology, philosophy, literature (both written and oral), and science comprise the intangible cultural heritage of a society.[5]

In the humanities, one sense of culture as an attribute of the individual has been the degree to which they have cultivated a particular level of sophistication in the arts, sciences, education, or manners. The level of cultural sophistication has also sometimes been used to distinguish civilizations from less complex societies. Such hierarchical perspectives on culture are also found in class-based distinctions between a high culture of the social elite and a low culture, popular culture, or folk culture of the lower classes, distinguished by the stratified access to cultural capital. In common parlance, culture is often used to refer specifically to the symbolic markers used by ethnic groups to distinguish themselves visibly from each other such as body modification, clothing or jewelry. Mass culture refers to the mass-produced and mass mediated forms of consumer culture that emerged in the 20th century. Some schools of philosophy, such as Marxism and critical theory, have argued that culture is often used politically as a tool of the elites to manipulate the proletariat and create a false consciousness. Such perspectives are common in the discipline of cultural studies. In the wider social sciences, the theoretical perspective of cultural materialism holds that human symbolic culture arises from the material conditions of human life, as humans create the conditions for physical survival, and that the basis of culture is found in evolved biological dispositions.

When used as a count noun, a «culture» is the set of customs, traditions, and values of a society or community, such as an ethnic group or nation. Culture is the set of knowledge acquired over time. In this sense, multiculturalism values the peaceful coexistence and mutual respect between different cultures inhabiting the same planet. Sometimes «culture» is also used to describe specific practices within a subgroup of a society, a subculture (e.g. «bro culture»), or a counterculture. Within cultural anthropology, the ideology and analytical stance of cultural relativism hold that cultures cannot easily be objectively ranked or evaluated because any evaluation is necessarily situated within the value system of a given culture.

Etymology

The modern term «culture» is based on a term used by the ancient Roman orator Cicero in his Tusculanae Disputationes, where he wrote of a cultivation of the soul or «cultura animi,»[6] using an agricultural metaphor for the development of a philosophical soul, understood teleologically as the highest possible ideal for human development. Samuel Pufendorf took over this metaphor in a modern context, meaning something similar, but no longer assuming that philosophy was man’s natural perfection. His use, and that of many writers after him, «refers to all the ways in which human beings overcome their original barbarism, and through artifice, become fully human.»[7]

In 1986, philosopher Edward S. Casey wrote, «The very word culture meant ‘place tilled’ in Middle English, and the same word goes back to Latin colere, ‘to inhabit, care for, till, worship’ and cultus, ‘A cult, especially a religious one.’ To be cultural, to have a culture, is to inhabit a place sufficiently intensely to cultivate it—to be responsible for it, to respond to it, to attend to it caringly.»[8]

Culture described by Richard Velkley:[7]

… originally meant the cultivation of the soul or mind, acquires most of its later modern meaning in the writings of the 18th-century German thinkers, who were on various levels developing Rousseau’s criticism of «modern liberalism and Enlightenment.» Thus a contrast between «culture» and «civilization» is usually implied in these authors, even when not expressed as such.

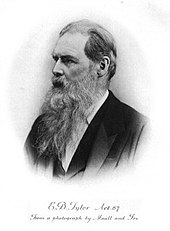

In the words of anthropologist E.B. Tylor, it is «that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.»[9] Alternatively, in a contemporary variant, «Culture is defined as a social domain that emphasizes the practices, discourses and material expressions, which, over time, express the continuities and discontinuities of social meaning of a life held in common.[10]

The Cambridge English Dictionary states that culture is «the way of life, especially the general customs and beliefs, of a particular group of people at a particular time.»[11] Terror management theory posits that culture is a series of activities and worldviews that provide humans with the basis for perceiving themselves as «person[s] of worth within the world of meaning»—raising themselves above the merely physical aspects of existence, in order to deny the animal insignificance and death that Homo sapiens became aware of when they acquired a larger brain.[12][13]

The word is used in a general sense as the evolved ability to categorize and represent experiences with symbols and to act imaginatively and creatively. This ability arose with the evolution of behavioral modernity in humans around 50,000 years ago and is often thought to be unique to humans. However, some other species have demonstrated similar, though much less complicated, abilities for social learning. It is also used to denote the complex networks of practices and accumulated knowledge and ideas that are transmitted through social interaction and exist in specific human groups, or cultures, using the plural form.[citation needed]

Change

The Beatles exemplified changing cultural dynamics, not only in music, but fashion and lifestyle. Over a half century after their emergence, they continue to have a worldwide cultural impact.

Raimon Panikkar identified 29 ways in which cultural change can be brought about, including growth, development, evolution, involution, renovation, reconception, reform, innovation, revivalism, revolution, mutation, progress, diffusion, osmosis, borrowing, eclecticism, syncretism, modernization, indigenization, and transformation.[14] In this context, modernization could be viewed as adoption of Enlightenment era beliefs and practices, such as science, rationalism, industry, commerce, democracy, and the notion of progress. Rein Raud, building on the work of Umberto Eco, Pierre Bourdieu and Jeffrey C. Alexander, has proposed a model of cultural change based on claims and bids, which are judged by their cognitive adequacy and endorsed or not endorsed by the symbolic authority of the cultural community in question.[15]

Cultural invention has come to mean any innovation that is new and found to be useful to a group of people and expressed in their behavior but which does not exist as a physical object. Humanity is in a global «accelerating culture change period,» driven by the expansion of international commerce, the mass media, and above all, the human population explosion, among other factors. Culture repositioning means the reconstruction of the cultural concept of a society.[16]

Full-length profile portrait of a Turkmen woman, standing on a carpet at the entrance to a yurt, dressed in traditional clothing and jewelry

Cultures are internally affected by both forces encouraging change and forces resisting change. These forces are related to both social structures and natural events, and are involved in the perpetuation of cultural ideas and practices within current structures, which themselves are subject to change.[17]

Social conflict and the development of technologies can produce changes within a society by altering social dynamics and promoting new cultural models, and spurring or enabling generative action. These social shifts may accompany ideological shifts and other types of cultural change. For example, the U.S. feminist movement involved new practices that produced a shift in gender relations, altering both gender and economic structures. Environmental conditions may also enter as factors. For example, after tropical forests returned at the end of the last ice age, plants suitable for domestication were available, leading to the invention of agriculture, which in turn brought about many cultural innovations and shifts in social dynamics.[18]

Cultures are externally affected via contact between societies, which may also produce—or inhibit—social shifts and changes in cultural practices. War or competition over resources may impact technological development or social dynamics. Additionally, cultural ideas may transfer from one society to another, through diffusion or acculturation. In diffusion, the form of something (though not necessarily its meaning) moves from one culture to another. For example, Western restaurant chains and culinary brands sparked curiosity and fascination to the Chinese as China opened its economy to international trade in the late 20th-century.[19] «Stimulus diffusion» (the sharing of ideas) refers to an element of one culture leading to an invention or propagation in another. «Direct borrowing,» on the other hand, tends to refer to technological or tangible diffusion from one culture to another. Diffusion of innovations theory presents a research-based model of why and when individuals and cultures adopt new ideas, practices, and products.[20]

Acculturation has different meanings. Still, in this context, it refers to the replacement of traits of one culture with another, such as what happened to certain Native American tribes and many indigenous peoples across the globe during the process of colonization. Related processes on an individual level include assimilation (adoption of a different culture by an individual) and transculturation. The transnational flow of culture has played a major role in merging different cultures and sharing thoughts, ideas, and beliefs.

Early modern discourses

German Romanticism

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) formulated an individualist definition of «enlightenment» similar to the concept of bildung: «Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity.»[21] He argued that this immaturity comes not from a lack of understanding, but from a lack of courage to think independently. Against this intellectual cowardice, Kant urged: «Sapere Aude» («Dare to be wise!»). In reaction to Kant, German scholars such as Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) argued that human creativity, which necessarily takes unpredictable and highly diverse forms, is as important as human rationality. Moreover, Herder proposed a collective form of Bildung: «For Herder, Bildung was the totality of experiences that provide a coherent identity, and sense of common destiny, to a people.»[22]

In 1795, the Prussian linguist and philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835) called for an anthropology that would synthesize Kant’s and Herder’s interests. During the Romantic era, scholars in Germany, especially those concerned with nationalist movements—such as the nationalist struggle to create a «Germany» out of diverse principalities, and the nationalist struggles by ethnic minorities against the Austro-Hungarian Empire—developed a more inclusive notion of culture as «worldview» (Weltanschauung).[23] According to this school of thought, each ethnic group has a distinct worldview that is incommensurable with the worldviews of other groups. Although more inclusive than earlier views, this approach to culture still allowed for distinctions between «civilized» and «primitive» or «tribal» cultures.

In 1860, Adolf Bastian (1826–1905) argued for «the psychic unity of mankind.»[24] He proposed that a scientific comparison of all human societies would reveal that distinct worldviews consisted of the same basic elements. According to Bastian, all human societies share a set of «elementary ideas» (Elementargedanken); different cultures, or different «folk ideas» (Völkergedanken), are local modifications of the elementary ideas.[25] This view paved the way for the modern understanding of culture. Franz Boas (1858–1942) was trained in this tradition, and he brought it with him when he left Germany for the United States.[26]

English Romanticism

British poet and critic Matthew Arnold viewed «culture» as the cultivation of the humanist ideal.

In the 19th century, humanists such as English poet and essayist Matthew Arnold (1822–1888) used the word «culture» to refer to an ideal of individual human refinement, of «the best that has been thought and said in the world.»[27] This concept of culture is also comparable to the German concept of bildung: «…culture being a pursuit of our total perfection by means of getting to know, on all the matters which most concern us, the best which has been thought and said in the world.»[27]

In practice, culture referred to an elite ideal and was associated with such activities as art, classical music, and haute cuisine.[28] As these forms were associated with urban life, «culture» was identified with «civilization» (from Latin: civitas, lit. ‘city’). Another facet of the Romantic movement was an interest in folklore, which led to identifying a «culture» among non-elites. This distinction is often characterized as that between high culture, namely that of the ruling social group, and low culture. In other words, the idea of «culture» that developed in Europe during the 18th and early 19th centuries reflected inequalities within European societies.[29]

British anthropologist Edward Tylor was one of the first English-speaking scholars to use the term culture in an inclusive and universal sense.

Matthew Arnold contrasted «culture» with anarchy; other Europeans, following philosophers Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, contrasted «culture» with «the state of nature.» According to Hobbes and Rousseau, the Native Americans who were being conquered by Europeans from the 16th centuries on were living in a state of nature; this opposition was expressed through the contrast between «civilized» and «uncivilized.»[30] According to this way of thinking, one could classify some countries and nations as more civilized than others and some people as more cultured than others. This contrast led to Herbert Spencer’s theory of Social Darwinism and Lewis Henry Morgan’s theory of cultural evolution. Just as some critics have argued that the distinction between high and low cultures is an expression of the conflict between European elites and non-elites, other critics have argued that the distinction between civilized and uncivilized people is an expression of the conflict between European colonial powers and their colonial subjects.

Other 19th-century critics, following Rousseau, have accepted this differentiation between higher and lower culture, but have seen the refinement and sophistication of high culture as corrupting and unnatural developments that obscure and distort people’s essential nature. These critics considered folk music (as produced by «the folk,» i.e., rural, illiterate, peasants) to honestly express a natural way of life, while classical music seemed superficial and decadent. Equally, this view often portrayed indigenous peoples as «noble savages» living authentic and unblemished lives, uncomplicated and uncorrupted by the highly stratified capitalist systems of the West.

In 1870 the anthropologist Edward Tylor (1832–1917) applied these ideas of higher versus lower culture to propose a theory of the evolution of religion. According to this theory, religion evolves from more polytheistic to more monotheistic forms.[31] In the process, he redefined culture as a diverse set of activities characteristic of all human societies. This view paved the way for the modern understanding of religion.

Anthropology

Petroglyphs in modern-day Gobustan, Azerbaijan, dating back to 10,000 BCE and indicating a thriving culture

Although anthropologists worldwide refer to Tylor’s definition of culture,[32] in the 20th century «culture» emerged as the central and unifying concept of American anthropology, where it most commonly refers to the universal human capacity to classify and encode human experiences symbolically, and to communicate symbolically encoded experiences socially.[33] American anthropology is organized into four fields, each of which plays an important role in research on culture: biological anthropology, linguistic anthropology, cultural anthropology, and in the United States and Canada, archaeology.[34][35][36][37] The term Kulturbrille, or «culture glasses,» coined by German American anthropologist Franz Boas, refers to the «lenses» through which a person sees their own culture. Martin Lindstrom asserts that Kulturbrille, which allow a person to make sense of the culture they inhabit, «can blind us to things outsiders pick up immediately.»[38]

Sociology

An example of folkloric dancing in Colombia

The sociology of culture concerns culture as manifested in society. For sociologist Georg Simmel (1858–1918), culture referred to «the cultivation of individuals through the agency of external forms which have been objectified in the course of history.»[39] As such, culture in the sociological field can be defined as the ways of thinking, the ways of acting, and the material objects that together shape a people’s way of life. Culture can be either of two types, non-material culture or material culture.[5] Non-material culture refers to the non-physical ideas that individuals have about their culture, including values, belief systems, rules, norms, morals, language, organizations, and institutions, while material culture is the physical evidence of a culture in the objects and architecture they make or have made. The term tends to be relevant only in archeological and anthropological studies, but it specifically means all material evidence which can be attributed to culture, past or present.

Cultural sociology first emerged in Weimar Germany (1918–1933), where sociologists such as Alfred Weber used the term Kultursoziologie (‘cultural sociology’). Cultural sociology was then reinvented in the English-speaking world as a product of the cultural turn of the 1960s, which ushered in structuralist and postmodern approaches to social science. This type of cultural sociology may be loosely regarded as an approach incorporating cultural analysis and critical theory. Cultural sociologists tend to reject scientific methods, instead hermeneutically focusing on words, artifacts and symbols.[40] Culture has since become an important concept across many branches of sociology, including resolutely scientific fields like social stratification and social network analysis. As a result, there has been a recent influx of quantitative sociologists to the field. Thus, there is now a growing group of sociologists of culture who are, confusingly, not cultural sociologists. These scholars reject the abstracted postmodern aspects of cultural sociology, and instead, look for a theoretical backing in the more scientific vein of social psychology and cognitive science.[41]

Nowruz is a good sample of popular and folklore culture that is celebrated by people in more than 22 countries with different nations and religions, at the 1st day of spring. It has been celebrated by diverse communities for over 7,000 years.

Early researchers and development of cultural sociology

The sociology of culture grew from the intersection between sociology (as shaped by early theorists like Marx,[42] Durkheim, and Weber) with the growing discipline of anthropology, wherein researchers pioneered ethnographic strategies for describing and analyzing a variety of cultures around the world. Part of the legacy of the early development of the field lingers in the methods (much of cultural, sociological research is qualitative), in the theories (a variety of critical approaches to sociology are central to current research communities), and in the substantive focus of the field. For instance, relationships between popular culture, political control, and social class were early and lasting concerns in the field.

Cultural studies

In the United Kingdom, sociologists and other scholars influenced by Marxism such as Stuart Hall (1932–2014) and Raymond Williams (1921–1988) developed cultural studies. Following nineteenth-century Romantics, they identified culture with consumption goods and leisure activities (such as art, music, film, food, sports, and clothing). They saw patterns of consumption and leisure as determined by relations of production, which led them to focus on class relations and the organization of production.[43][44]

In the United Kingdom, cultural studies focuses largely on the study of popular culture; that is, on the social meanings of mass-produced consumer and leisure goods. Richard Hoggart coined the term in 1964 when he founded the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies or CCCS.[45] It has since become strongly associated with Stuart Hall,[46] who succeeded Hoggart as Director.[47] Cultural studies in this sense, then, can be viewed as a limited concentration scoped on the intricacies of consumerism, which belongs to a wider culture sometimes referred to as Western civilization or globalism.

From the 1970s onward, Stuart Hall’s pioneering work, along with that of his colleagues Paul Willis, Dick Hebdige, Tony Jefferson, and Angela McRobbie, created an international intellectual movement. As the field developed, it began to combine political economy, communication, sociology, social theory, literary theory, media theory, film/video studies, cultural anthropology, philosophy, museum studies, and art history to study cultural phenomena or cultural texts. In this field researchers often concentrate on how particular phenomena relate to matters of ideology, nationality, ethnicity, social class, and/or gender.[48] Cultural studies is concerned with the meaning and practices of everyday life. These practices comprise the ways people do particular things (such as watching television or eating out) in a given culture. It also studies the meanings and uses people attribute to various objects and practices. Specifically, culture involves those meanings and practices held independently of reason. Watching television to view a public perspective on a historical event should not be thought of as culture unless referring to the medium of television itself, which may have been selected culturally; however, schoolchildren watching television after school with their friends to «fit in» certainly qualifies since there is no grounded reason for one’s participation in this practice.

In the context of cultural studies, a text includes not only written language, but also films, photographs, fashion or hairstyles: the texts of cultural studies comprise all the meaningful artifacts of culture.[49] Similarly, the discipline widens the concept of culture. Culture, for a cultural-studies researcher, not only includes traditional high culture (the culture of ruling social groups)[50] and popular culture, but also everyday meanings and practices. The last two, in fact, have become the main focus of cultural studies. A further and recent approach is comparative cultural studies, based on the disciplines of comparative literature and cultural studies.[51]

Scholars in the United Kingdom and the United States developed somewhat different versions of cultural studies after the late 1970s. The British version of cultural studies had originated in the 1950s and 1960s, mainly under the influence of Richard Hoggart, E.P. Thompson, and Raymond Williams, and later that of Stuart Hall and others at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham. This included overtly political, left-wing views, and criticisms of popular culture as «capitalist» mass culture; it absorbed some of the ideas of the Frankfurt School critique of the «culture industry» (i.e. mass culture). This emerges in the writings of early British cultural-studies scholars and their influences: see the work of (for example) Raymond Williams, Stuart Hall, Paul Willis, and Paul Gilroy.

In the United States, Lindlof and Taylor write, «cultural studies [were] grounded in a pragmatic, liberal-pluralist tradition.»[52] The American version of cultural studies initially concerned itself more with understanding the subjective and appropriative side of audience reactions to, and uses of, mass culture; for example, American cultural-studies advocates wrote about the liberatory aspects of fandom.[citation needed] The distinction between American and British strands, however, has faded.[citation needed] Some researchers, especially in early British cultural studies, apply a Marxist model to the field. This strain of thinking has some influence from the Frankfurt School, but especially from the structuralist Marxism of Louis Althusser and others. The main focus of an orthodox Marxist approach concentrates on the production of meaning. This model assumes a mass production of culture and identifies power as residing with those producing cultural artifacts. In a Marxist view, the mode and relations of production form the economic base of society, which constantly interacts and influences superstructures, such as culture.[53] Other approaches to cultural studies, such as feminist cultural studies and later American developments of the field, distance themselves from this view. They criticize the Marxist assumption of a single, dominant meaning, shared by all, for any cultural product. The non-Marxist approaches suggest that different ways of consuming cultural artifacts affect the meaning of the product. This view comes through in the book Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman (by Paul du Gay et al.),[54] which seeks to challenge the notion that those who produce commodities control the meanings that people attribute to them. Feminist cultural analyst, theorist, and art historian Griselda Pollock contributed to cultural studies from viewpoints of art history and psychoanalysis. The writer Julia Kristeva is among influential voices at the turn of the century, contributing to cultural studies from the field of art and psychoanalytical French feminism.[55]

Petrakis and Kostis (2013) divide cultural background variables into two main groups:[56]

- The first group covers the variables that represent the «efficiency orientation» of the societies: performance orientation, future orientation, assertiveness, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance.

- The second covers the variables that represent the «social orientation» of societies, i.e., the attitudes and lifestyles of their members. These variables include gender egalitarianism, institutional collectivism, in-group collectivism, and human orientation.

In 2016, a new approach to culture was suggested by Rein Raud,[15] who defines culture as the sum of resources available to human beings for making sense of their world and proposes a two-tiered approach, combining the study of texts (all reified meanings in circulation) and cultural practices (all repeatable actions that involve the production, dissemination or transmission of purposes), thus making it possible to re-link anthropological and sociological study of culture with the tradition of textual theory.

Psychology

Cognitive tools suggest a way for people from certain culture to deal with real-life problems, like Suanpan for Chinese to perform mathematical calculation.

Starting in the 1990s,[57]: 31 psychological research on culture influence began to grow and challenge the universality assumed in general psychology.[58]: 158–168 [59] Culture psychologists began to try to explore the relationship between emotions and culture, and answer whether the human mind is independent from culture. For example, people from collectivistic cultures, such as the Japanese, suppress their positive emotions more than their American counterparts.[60] Culture may affect the way that people experience and express emotions. On the other hand, some researchers try to look for differences between people’s personalities across cultures.[61][62] As different cultures dictate distinctive norms, culture shock is also studied to understand how people react when they are confronted with other cultures. Cognitive tools may not be accessible or they may function differently cross culture.[57]: 19 For example, people who are raised in a culture with an abacus are trained with distinctive reasoning style.[63] Cultural lenses may also make people view the same outcome of events differently. Westerners are more motivated by their successes than their failures, while East Asians are better motivated by the avoidance of failure.[64] Culture is important for psychologists to consider when understanding the human mental operation.

Protection of culture

There are a number of international agreements and national laws relating to the protection of culture and cultural heritage. UNESCO and its partner organizations such as Blue Shield International coordinate international protection and local implementation.[65][66]

Basically, the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict and the UNESCO Convention for the Protection of Cultural Diversity deal with the protection of culture. Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights deals with cultural heritage in two ways: it gives people the right to participate in cultural life on the one hand and the right to the protection of their contributions to cultural life on the other.[67]

The protection of culture and cultural goods is increasingly taking up a large area nationally and internationally. Under international law, the UN and UNESCO try to set up and enforce rules for this. The aim is not to protect a person’s property, but rather to preserve the cultural heritage of humanity, especially in the event of war and armed conflict. According to Karl von Habsburg, President of Blue Shield International, the destruction of cultural assets is also part of psychological warfare. The target of the attack is the identity of the opponent, which is why symbolic cultural assets become a main target. It is also intended to affect the particularly sensitive cultural memory, the growing cultural diversity and the economic basis (such as tourism) of a state, region or municipality.[68][69][70]

Another important issue today is the impact of tourism on the various forms of culture. On the one hand, this can be physical impact on individual objects or the destruction caused by increasing environmental pollution and, on the other hand, socio-cultural effects on society.[71][72][73]

See also

- Animal culture

- Anthropology

- Cultural area

- Cultural studies

- Cultural tourism

- Culture 21 – United Nations plan of action

- Honour § Cultures of honour and cultures of law

- Outline of culture

- Recombinant culture

- Semiotics of culture

References

- ^ Tylor, Edward. (1871). Primitive Culture. Vol 1. New York: J.P. Putnam’s Son

- ^ Jackson, Y. Encyclopedia of Multicultural Psychology, p. 203

- ^ Chigbu, Uchendu Eugene (November 24, 2014). «Repositioning culture for development: women and development in a Nigerian rural community». Community, Work & Family. 18 (3): 334–350. doi:10.1080/13668803.2014.981506. ISSN 1366-8803. S2CID 144448501. Archived from the original on July 30, 2022. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ Michael Obert (2013) Song from the Forest

- ^ a b Macionis, John J; Gerber, Linda Marie (2011). Sociology. Toronto: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-13-700161-3. OCLC 652430995.

- ^ Cicéron, Marcus Tullius Cicero; Bouhier, Jean (1812). Tusculanes (in French). Nismes: J. Gaude. p. 273. OCLC 457735057. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- ^ a b Velkley, Richard L (2002). «The Tension in the Beautiful: On Culture and Civilization in Rousseau and German Philosophy». Being after Rousseau: philosophy and culture in question. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 11–30. ISBN 978-0-226-85256-0. OCLC 47930775.

- ^ Sorrells, Kathryn (2015). Intercultural Communication: Globalization and Social Justice. Los Angeles: Sage. ISBN 978-1-4129-2744-4.[page needed]

- ^ Tylor 1974, 1.

- ^ James, Paul; Magee, Liam; Scerri, Andy; Steger, Manfred (2015). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. London: Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-138-02572-1. OCLC 942553107. Archived from the original on June 26, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ «Meaning of «culture»«. Cambridge English Dictionary. Archived from the original on August 15, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- ^ Pyszczynski, Tom; Solomon, Sheldon; Greenberg, Jeff (2015). Thirty Years of Terror Management Theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 52. pp. 1–70. doi:10.1016/bs.aesp.2015.03.001. ISBN 978-0-12-802247-4.

- ^ Greenberg, Jeff; Koole, Sander L.; Pyszczynski, Tom (2013). Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology. Guilford Publications. ISBN 978-1-4625-1479-3. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ^ Panikkar, Raimon (1991). Pathil, Kuncheria (ed.). Religious Pluralism: An Indian Christian Perspective. ISPCK. pp. 252–99. ISBN 978-81-7214-005-2. OCLC 25410539.

- ^ a b Rein, Raud (August 29, 2016). Meaning in Action: Outline of an Integral Theory of Culture. Cambridge: Polity. ISBN 978-1-5095-1124-2. OCLC 944339574.

- ^ Chigbu, Uchendu Eugene (July 3, 2015). «Repositioning culture for development: women and development in a Nigerian rural community». Community, Work & Family. 18 (3): 334–50. doi:10.1080/13668803.2014.981506. ISSN 1366-8803. S2CID 144448501.

- ^ O’Neil, Dennis (2006). «Culture Change: Processes of Change». Culture Change. Palomar College. Archived from the original on October 27, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2016.

- ^ Pringle, Heather (November 20, 1998). «The Slow Birth of Agriculture». Science. 282 (5393): 1446. doi:10.1126/science.282.5393.1446. ISSN 0036-8075. S2CID 128522781.

- ^ Wei, Clarissa (March 20, 2018). «Why China Loves American Chain Restaurants So Much». Eater. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Stephen Wolfram (May 16, 2017) A New Kind of Science: A 15-Year View Archived February 28, 2021, at the Wayback Machine As applied to the computational universe

- ^ Kant, Immanuel. 1784. «Answering the Question: What is Enlightenment?» (German: Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung?) Berlinische Monatsschrift, December (Berlin Monthly)

- ^ Eldridge, Michael. «The German Bildung Tradition». UNC Charlotte. Archived from the original on January 23, 2009. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ Underhill, James W. (2009). Humboldt, Worldview, and Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ Köpping, Klaus-Peter (2005). Adolf Bastian and the psychic unity of mankind. Lit Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8258-3989-5. OCLC 977343058.

- ^ Ellis, Ian. «Biography of Adolf Bastian, ethnologist». Today in Science History. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ Liron, Tal (2003). Franz Boas and the discovery of culture (PDF) (Thesis). OCLC 52888196. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 2, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ a b Arnold, Matthew (1869). «Culture and Anarchy». Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ Williams (1983), p. 90. Cited in Roy, Shuker (1997). Understanding popular music. Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-415-10723-5. OCLC 245910934. argues that contemporary definitions of culture fall into three possibilities or mixture of the following three:

- «a general process of intellectual, spiritual, and aesthetic development.»

- «a particular way of life, whether of a people, period or a group.»

- «the works and practices of intellectual and especially artistic activity.»

- ^ Bakhtin 1981, p. 4

- ^ Dunne, Timothy; Reus-Smit, Christian (2017). The globalization of international society. Oxford. pp. 102–121. ISBN 978-0-19-251193-5.

- ^ McClenon, pp. 528–29

- ^ Angioni, Giulio (1973). Tre saggi sull’antropologia dell’età coloniale (in Italian). OCLC 641869481.

- ^ Teslow, Tracy (March 10, 2016). Constructing race: the science of bodies and cultures in American anthropology. ISBN 978-1-316-60338-3. OCLC 980557304. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ «anthropology». Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020.

- ^ Fernandez, James W.; Hanchett, Suzanne L.; Jeganathan, Pradeep; Nicholas, Ralph W.; Robotham, Donald Keith; Smith, Eric A. (August 31, 2015). «anthropology | Britannica.com». Britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ «What is Anthropology? – Advance Your Career». American Anthropological Association. Archived from the original on October 26, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ Haviland, William A.; McBride, Bunny; Prins, Harald E.L.; Walrath, Dana (2011). Cultural Anthropology: The Human Challenge. Wadsworth/Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-81082-7. OCLC 731048150.

- ^ Lindström, Martin (2016). Small data: the tiny clues that uncover huge trends. London: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-1-250-08068-4. OCLC 921994909.

- ^ Simmel, Georg (1971). Levine, Donald N (ed.). Georg Simmel on individuality and social forms: selected writings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. xix. ISBN 978-0-226-75776-6. OCLC 951272809. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ Sokal, Alan D. (June 5, 1996). «A Physicist Experiments with Cultural Studies». Lingua Franca. Archived from the original on March 26, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2016. Physicist Alan Sokal published a paper in a journal of cultural sociology stating that gravity was a social construct that should be examined hermeneutically. See Sokal affair for further details.

- ^ Griswold, Wendy (1987). «A Methodological Framework for the Sociology of Culture». Sociological Methodology. 17: 1–35. doi:10.2307/271027. ISSN 0081-1750. JSTOR 271027.

- ^ Berlin, Isaiah; Ryan, Alan (2002). Karl Marx: His Life and Environment. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-19-510326-7. OCLC 611127754.

- ^ Williams, Raymond (1983), Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 87–93, 236–38, OCLC 906396817

- ^ Berger, John (1972). Ways of seeing. Peter Smithn. ISBN 978-0-563-12244-9. OCLC 780459348.

- ^ «Studying Culture – Reflections and Assessment: An Interview with Richard Hoggart». Media, Culture & Society. 13.

- ^ Adams, Tim (September 23, 2007). «Cultural hallmark». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ James, Procter (2004). Stuart Hall. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26267-5. OCLC 318376213.

- ^ Sardar, Ziauddin; Van Loon, Borin; Appignanesi, Richard (1994). Introducing Cultural Studies. New York: Totem Books. ISBN 978-1-84046-587-7. OCLC 937991291.

- ^ Fiske, John; Turner, Graeme; Hodge, Robert Ian Vere (1987). Myths of Oz: reading Australian popular culture. London: Allen and Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-330391-7. OCLC 883364628.

- ^ Bakhtin, Mikhail Mikhaĭlovich; Holquist, Michael (1981). The dialogic imagination four essays. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 4. OCLC 872436352. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ «Comparative Cultural Studies». Purdue University Press. 2015. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ Lindlof, Thomas R; Taylor, Bryan C (2002). Qualitative Communication Research Methods (2nd ed.). Sage. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-7619-2493-7. OCLC 780825710.

- ^ Gonick, Cy (February 7, 2006). «Marxism». The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ du Gay, Paul, ed. (1997). Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman. Sage. ISBN 978-0-7619-5402-6. OCLC 949857570. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ MacKenzie, Gina (August 21, 2018). «Julia Kristeva». Oxford Bibliographies. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Petrakis, Panagiotis; Kostis, Pantelis (December 1, 2013). «Economic growth and cultural change». The Journal of Socio-Economics. 47: 147–57. doi:10.1016/j.socec.2013.02.011.

- ^ a b Heine, Steven J. (2015). Cultural psychology. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Cognitive Science. Vol. 1 (Third ed.). New York, NY. pp. 254–266. doi:10.1002/wcs.7. ISBN 9780393263985. OCLC 911004797. PMID 26271239.

- ^ Myers, David G. (2010). Social psychology (Tenth ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 9780073370668. OCLC 667213323.

- ^ Norenzayan, Ara; Heine, Steven J. (September 2005). «Psychological universals: what are they and how can we know?». Psychological Bulletin. 131 (5): 763–784. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.5.763. ISSN 0033-2909. PMID 16187859.

- ^ Miyahara, Akira. «Toward Theorizing Japanese Communication Competence from a Non-Western Perspective». American Communication Journal. 3 (3).

- ^ McCrae, Robert R.; Costa, Paul T.; de Lima, Margarida Pedroso; Simões, António; Ostendorf, Fritz; Angleitner, Alois; Marušić, Iris; Bratko, Denis; Caprara, Gian Vittorio; Barbaranelli, Claudio; Chae, Joon-Ho; Piedmont, Ralph L. (1999). «Age differences in personality across the adult life span: Parallels in five cultures». Developmental Psychology. American Psychological Association (APA). 35 (2): 466–477. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.35.2.466. ISSN 1939-0599. PMID 10082017.

- ^ Cheung, F. M.; Leung, K.; Fan, R. M.; Song, W.S.; Zhang, J. X.; Zhang, H. P. (March 1996). «Development of the Chinese Personality Assessment Inventory». Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 27 (2): 181–199. doi:10.1177/0022022196272003. S2CID 145134209.

- ^ Baillargeon, Rene (2002), «The Acquisition of Physical Knowledge in Infancy: A Summary in Eight Lessons», Blackwell Handbook of Childhood Cognitive Development, Blackwell Publishers Ltd, pp. 47–83, doi:10.1002/9780470996652.ch3, ISBN 9780470996652

- ^ Heine, Steven J.; Kitayama, Shinobu; Lehman, Darrin R. (2001). «Cultural Differences in Self-Evaluation». Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 32 (4): 434–443. doi:10.1177/0022022101032004004. ISSN 0022-0221. S2CID 40475406.

- ^ Roger O’Keefe, Camille Péron, Tofig Musayev, Gianluca Ferrari «Protection of Cultural Property. Military Manual.» UNESCO, 2016, p 73.

- ^ UNESCO Director-General calls for stronger cooperation for heritage protection at the Blue Shield International General Assembly. UNESCO, September 13, 2017.

- ^ «UNESCO Legal Instruments: Second Protocol to the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict 1999». Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Gerold Keusch «Kulturschutz in der Ära der Identitätskriege» In: Truppendienst — Magazin des Österreichischen Bundesheeres, October 24, 2018.

- ^ «Karl von Habsburg auf Mission im Libanon» (in German). April 28, 2019. Archived from the original on May 26, 2020. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ Corine Wegener; Marjan Otter (Spring 2008), «Cultural Property at War: Protecting Heritage during Armed Conflict», The Getty Conservation Institute Newsletter, The Getty Conservation Institute, vol. 23, no. 1;

Eden Stiffman (May 11, 2015), «Cultural Preservation in Disasters, War Zones. Presents Big Challenges», The Chronicle Of Philanthropy;

Hans Haider (June 29, 2012), «Missbrauch von Kulturgütern ist strafbar», Wiener Zeitung - ^ Shepard, Robert (August 2002). «Commodification, culture and tourism». Tourist Studies. 2 (2): 183–201. doi:10.1177/146879702761936653. S2CID 55744323.

- ^ Coye, N. dir. (2011), Lascaux et la conservation en milieu souterrain: actes du symposium international (Paris, 26-27 fév. 2009) = Lascaux and Preservation Issues in Subterranean Environments: Proceedings of the International Symposium (Paris, February 26 and 27), Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 360 p.

- ^ Jaafar, Mastura; Rasoolimanesh, S Mostafa; Ismail, Safura (2017). «Perceived sociocultural impacts of tourism and community participation: A case study of Langkawi Island». Tourism and Hospitality Research. 17 (2): 123–134. doi:10.1177/1467358415610373. S2CID 157784805.

Further reading

Books

- Barker, C. (2004). The Sage dictionary of cultural studies. Sage.

- Terrence Deacon (1997). The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. New York and London: W.W. Norton. ISBN 9780393038385.

- Ralph L. Holloway Jr. (1969). «Culture: A Human domain». Current Anthropology. 10 (4): 395–412. doi:10.1086/201036. S2CID 144502900.

- Dell Hymes (1969). Reinventing Anthropology.

- James, Paul; Szeman, Imre (2010). Globalization and Culture, Vol. 3: Global-Local Consumption. London: Sage Publications.

- Michael Tomasello (1999). «The Human Adaptation for Culture». Annual Review of Anthropology. 28: 509–29. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.28.1.509.

- Whorf, Benjamin Lee (1941). «The relation of habitual thought and behavior to language». Language, Culture, and Personality: Essays in Honor of Edward Sapir.

- Walter Taylor (1948). A Study of Archeology. Memoir 69, American Anthropological Association. Carbondale IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

- «Adolf Bastian», Encyclopædia Britannica Online, January 27, 2009

- Ankerl, Guy (2000) [2000]. Global communication without universal civilization, vol.1: Coexisting contemporary civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. INU societal research. Geneva: INU Press. ISBN 978-2-88155-004-1.

- Arnold, Matthew. 1869. Culture and Anarchy. Archived November 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine New York: Macmillan. Third edition, 1882, available online. Retrieved: 2006-06-28.

- Bakhtin, M.M. (1981) The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Ed. Michael Holquist. Trans. Caryl Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06445-6.

- Barzilai, Gad. 2003. Communities and Law: Politics and Cultures of Legal Identities University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-11315-1

- Benedict, Ruth (1934). Patterns of Culture. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29164-4

- Michael C. Carhart, The Science of Culture in Enlightenment Germany, Cambridge, Harvard University press, 2007.

- Cohen, Anthony P. 1985. The Symbolic Construction of Community. Routledge: New York,

- Dawkins, R. 1982. The Extended Phenotype: The Long Reach of the Gene. Paperback ed., 1999. Oxford Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-19-288051-2

- Findley & Rothney. Twentieth-Century World (Houghton Mifflin, 1986)

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York. ISBN 978-0-465-09719-7.

- Geertz, Clifford (1957). «Ritual and Social Change: A Javanese Example». American Anthropologist. 59: 32–54. doi:10.1525/aa.1957.59.1.02a00040.

- Goodall, J. 1986. The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-11649-8

- Hoult, T.F., ed. 1969. Dictionary of Modern Sociology. Totowa, New Jersey, United States: Littlefield, Adams & Co.

- Jary, D. and J. Jary. 1991. The HarperCollins Dictionary of Sociology. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-271543-7

- Keiser, R. Lincoln 1969. The Vice Lords: Warriors of the Streets. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. ISBN 978-0-03-080361-1.

- Kroeber, A.L. and C. Kluckhohn, 1952. Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum

- Kim, Uichol (2001). «Culture, science and indigenous psychologies: An integrated analysis.» In D. Matsumoto (Ed.), Handbook of culture and psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- McClenon, James. «Tylor, Edward B(urnett)». Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Ed. William Swatos and Peter Kivisto. Walnut Creek: AltaMira, 1998. 528–29.

- Middleton, R. 1990. Studying Popular Music. Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 978-0-335-15275-9.

- O’Neil, D. 2006. Cultural Anthropology Tutorials Archived December 4, 2004, at the Wayback Machine, Behavioral Sciences Department, Palomar College, San Marco, California. Retrieved: 2006-07-10.

- Reagan, Ronald. «Final Radio Address to the Nation» Archived January 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, January 14, 1989. Retrieved June 3, 2006.

- Reese, W.L. 1980. Dictionary of Philosophy and Religion: Eastern and Western Thought. New Jersey U.S., Sussex, U.K: Humanities Press.

- Tylor, E.B. (1974) [1871]. Primitive culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art, and custom. New York: Gordon Press. ISBN 978-0-87968-091-6.

- UNESCO. 2002. Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity, issued on International Mother Language Day, February 21, 2002. Retrieved: 2006-06-23.

- White, L. 1949. The Science of Culture: A study of man and civilization. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Wilson, Edward O. (1998). Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. Vintage: New York. ISBN 978-0-679-76867-8.

- Wolfram, Stephen. 2002 A New Kind of Science. Wolfram Media, Inc. ISBN 978-1-57955-008-0.

Articles

- The Meaning of «Culture» (2014-12-27), Joshua Rothman, The New Yorker

External links

- Cultura: International Journal of Philosophy of Culture and Axiology

- What is Culture?

English[edit]

Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to:

Wikiquote

Wikisource has original text related to this entry:

Wikisource

Alternative forms[edit]

- culcha (pronunciation spelling)

Etymology[edit]

From Middle French culture (“cultivation; culture”), from Latin cultūra (“cultivation; culture”), from cultus, perfect passive participle of colō (“till, cultivate, worship”) (related to colōnus and colōnia), from Proto-Indo-European *kʷel- (“to move; to turn (around)”).

Pronunciation[edit]

- (General American) IPA(key): /ˈkʌlt͡ʃɚ/

- (Received Pronunciation) IPA(key): /ˈkʌlt͡ʃə/

Noun[edit]

culture (countable and uncountable, plural cultures)

- The arts, customs, lifestyles, background, and habits that characterize humankind, or a particular society or nation.

-

1981, William Irwin Thompson, The Time Falling Bodies Take to Light: Mythology, Sexuality and the Origins of Culture, London: Rider/Hutchinson & Co., page 125:

-

Castration of bulls was a socialization process that turned a bull into an ox; in this transformation something wild became something very useful; nature became culture.

-

-

2013 September 7, “Farming as rocket science”, in The Economist, volume 408, number 8852:

-

Such differences of history and culture have lingering consequences. Almost all the corn and soyabeans grown in America are genetically modified. GM crops are barely tolerated in the European Union. Both America and Europe offer farmers indefensible subsidies, but with different motives.

-

-

- The beliefs, values, behaviour and material objects that constitute a people’s way of life.

- The conventional conducts and ideologies of a community; the system comprising the accepted norms and values of a society.

-

2012 March-April, Jan Sapp, “Race Finished”, in American Scientist, volume 100, number 2, page 164:

-

Few concepts are as emotionally charged as that of race. The word conjures up a mixture of associations—culture, ethnicity, genetics, subjugation, exclusion and persecution.

-

-

- (anthropology) Any knowledge passed from one generation to the next, not necessarily with respect to human beings.

- (botany) Cultivation.

- http://counties.cce.cornell.edu/suffolk/grownet/flowers/sprgbulb.htm

- The Culture of Spring-Flowering Bulbs

- http://counties.cce.cornell.edu/suffolk/grownet/flowers/sprgbulb.htm

- (microbiology) The process of growing a bacterial or other biological entity in an artificial medium.

- The growth thus produced.

-

I’m headed to the lab to make sure my cell culture hasn’t died.

-

- A group of bacteria.

- (cartography) The details on a map that do not represent natural features of the area delineated, such as names and the symbols for towns, roads, meridians, and parallels.

- (archaeology) A recurring assemblage of artifacts from a specific time and place that may constitute the material culture remains of a particular past human society.

- (euphemistic) Ethnicity, race (and its associated arts, customs, etc.)

Derived terms[edit]

- adult third culture kid

- anticulture

- astaciculture

- aviculture

- biculture

- call-out culture

- callout culture

- cancel culture

- canteen culture

- cassette culture

- Cemetery H culture

- coffee culture

- compensation culture

- counter culture

- culture hero

- culture jamming

- culture maker

- culture medium

- culture minister

- culture of death

- culture vulture

- culture war

- culture warrior

- culture-bound

- culture-fair

- culture-hero

- culture-jack

- cyberculture

- dark culture

- dependency culture

- folk culture

- fruticulture

- haute culture

- high context culture

- high culture

- high-context culture

- horticulture

- idioculture

- lad culture

- low context culture

- low-context culture

- macroculture

- mass culture

- microculture

- monoculture

- multiculture

- nonmaterial culture

- olericulture

- outrage culture

- overculture

- palace of culture

- permaculture

- physical culture

- pisciculture

- polyculture

- pop culture

- popular culture

- porciculture

- rape culture

- reverse culture shock

- Sang culture

- security culture

- self-culture

- subculture

- third culture kid

- tissue culture

- uberculture

- underculture

- ur-culture

- viticulture

[edit]

- agriculture

Translations[edit]

arts, customs and habits

- Afrikaans: kultuur (af)

- Albanian: rrethanë (sq) f,doke (sq), kulturë (sq) f,

- American Sign Language: C@NearFinger-PalmForwardHandUp-1@CenterChesthigh-FingerUp RoundHoriz C@NearFinger-PalmBackHandUp-1@CenterChesthigh-FingerUp

- Amharic: ባህል m (bahl)

- Arabic: ثَقَافَة (ar) f (ṯaqāfa)

- Egyptian Arabic: ثقافة f (saqāfa, ṯaqāfa)

- Hijazi Arabic: ثقافة f (ṯaqāfa)

- Moroccan Arabic: ثقافة f (taqāfa)

- Armenian: մշակույթ (hy) (mšakuytʿ)

- Assamese: সংস্কৃতি (xoṅskriti)

- Assyrian Neo-Aramaic: please add this translation if you can

- Asturian: cultura (ast)

- Azerbaijani: mədəniyyət (az)

- Bashkir: мәҙәниәт (mäðäniät)

- Bavarian: Kuitua

- Belarusian: культу́ра (be) f (kulʹtúra)

- Bengali: সংস্কৃতি (bn) (śoṅśkriti), রসম (bn) (rośom), রেওয়াজ (bn) (reōẇaj), তমদ্দুন (bn) (tomoddun)

- Breton: sevenadur (br) m

- Bulgarian: култу́ра (bg) f (kultúra)

- Burmese: ယဉ်ကျေးမှု (my) (yanykye:hmu.)

- Buryat: соёл (sojol)

- Catalan: cultura (ca) f

- Chechen: оьздангалла (özdangalla)

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 文化 (man4 faa3)

- Dungan: вынхуа (vɨnhua)

- Mandarin: 文化 (zh) (wénhuà)

- Min Nan: 文化 (zh-min-nan) (bûn-hoà)

- Wu: 文化 (ven ho)

- Chuvash: культура (kulʹtura)

- Coptic: ⲓⲉⲃⲟⲩⲱⲓ m (iebouōi)

- Czech: kultura (cs) f

- Danish: kultur (da)

- Dhivehi: ސަގާފަތު (sagāfatu)

- Dutch: cultuur (nl) f

- Esperanto: kulturo

- Estonian: kultuur

- Extremaduran: coltura f

- Faroese: mentan f, mentir f pl, (rare) mentun f

- Finnish: kulttuuri (fi)

- French: culture (fr) f

- Galician: cultura (gl) f

- Georgian: კულტურა (ḳulṭura)

- German: Kultur (de) f

- Greek: πολιτισμός (el) m (politismós)

- Guaraní: teko (gn)

- Gujarati: સંસ્કૃતિ f (sãskṛti)

- Haitian Creole: kilti

- Hebrew: תַּרְבּוּת (he) f (tarbút)

- Hindi: संस्कृति (hi) f (sanskŕti), सक़ाफ़त f (saqāfat) (Muslim), तहज़ीब f (tahzīb), फ़रहंग (farhaṅg)

- Hungarian: kultúra (hu)

- Icelandic: menning (is) f

- Ido: kulturo (io)

- Indonesian: budaya (id)

- Interlingua: cultura f

- Irish: cultúr m

- Italian: cultura (it) f

- Japanese: 文化 (ja) (ぶんか, bunka), カルチャー (ja) (karuchā)

- Kalmyk: сойл (soyl)

- Kannada: ಸಂಸ್ಕೃತಿ (kn) (saṃskṛti)

- Kazakh: мәдениет (kk) (mädeniet)

- Khmer: វប្បធម៌ (km) (vŏəppaʼthɔə)

- Korean: 문화(文化) (ko) (munhwa)

- Kurdish:

- Northern Kurdish: çande (ku) f, kultûr (ku) f, irf (ku) f, edet (ku) f

- Kyrgyz: маданият (ky) (madaniyat)

- Lao: ວັດທະນະທຳ (lo) (wat tha na tham)

- Latin: cultūra f

- Latvian: kultūra f

- Ligurian: coltûa

- Lithuanian: kultūra (lt) f

- Low German: kultur

- Lü: ᦞᧆᦒᦓᦱᦒᧄ (vadthnaatham)

- Macedonian: култу́ра f (kultúra)

- Malagasy: kolontsaina (mg), fomba (mg)

- Malay: budaya (ms)

- Malayalam: സംസ്ക്കാരം (ml) (saṃskkāraṃ)

- Maltese: kultura f

- Maori: ahurea, tikanga

- Marathi: संस्कृती (sauskrutī)

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: соёл (mn) (sojol)

- Mongolian: ᠰᠣᠶᠤᠯ (soyul)

- Nahuatl: cultura f

- Navajo: éʼélʼį́

- Nepali: संस्कृति (ne) (sanskr̥ti)

- Norman: tchulteure f (France), tchututhe f (Jersey)

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: kultur (no) m

- Nynorsk: kultur m

- Occitan: cultura (oc) f

- Oriya: ସଂସ୍କୃତି (or) (sôṃskruti)

- Ottoman Turkish: مدنیت (medeniyyet)

- Pashto: کلتور m (kultur), ثقافت (ps) m (saqāfat), فرهنګ m (farhang), کلچر m (kalčar)

- Persian: فرهنگ (fa) (farhang), کولتور (kultur)

- Polish: kultura (pl) f, obyczajowość

- Portuguese: cultura (pt) f

- Punjabi: ਸੰਸਕ੍ਰਿਤੀ (pa) f (sanskritī)

- Romanian: cultură (ro) f

- Russian: культу́ра (ru) f (kulʹtúra)

- Rusyn: култу́ра f (kultúra)

- Sanskrit: संस्कृति (sa) m (saṃskṛti)

- Scots: cultur

- Scottish Gaelic: dualchas m, cultar m

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: култу́ра f

- Roman: kultúra (sh) f

- Sicilian: curtura f

- Sinhalese: සංස්කෘතිය (saṁskr̥tiya)

- Slovak: kultúra f

- Slovene: kultura (sl) f

- Somali: dhaqan

- Spanish: cultura (es) f

- Swahili: utamaduni (sw)

- Swedish: kultur (sv) c

- Tagalog: kultura, kalinangan

- Tajik: фарҳанг (tg) (farhang), маданият (madaniyat), култура (kultura)

- Tamil: பண்பாடு (ta) (paṇpāṭu), கலாச்சாரம் (ta) (kalāccāram)

- Tatar: мәдәният (tt) (mädäniyat)

- Telugu: సంస్కృతి (te) (saṁskr̥ti)

- Thai: วัฒนธรรม (th) (wát-tá-ná-tam)

- Tibetan: རིག་གནས (rig gnas)

- Tigrinya: ባህሊ (bahli)

- Turkish: kültür (tr), hars (tr)

- Turkmen: medeniýet

- Udmurt: лулчеберет (lulćeberet)

- Ukrainian: культу́ра (uk) f (kulʹtúra)

- Urdu: ثَقافَت f (saqāfat), فَرْہَن٘گ (farhang), تَہْذِیب (ur) f (tahzīb)

- Uyghur: مەدەنىيەت (medeniyet)

- Uzbek: madaniyat (uz)

- Cyrillic: маданият (madaniyat)

- Vietnamese: văn hoá (vi) (文化)

- Vilamovian: kultür

- Welsh: diwylliant (cy) m

- West Frisian: kultuer (fy)

- Yiddish: קולטור f (kultur)

- Zazaki: kultur, ferheng (diq), edet (diq)

- Zhuang: vwnzva

the beliefs, values, behavior and material objects that constitute a people’s way of life

- Albanian: kulturë (sq) f

- American Sign Language: C@NearFinger-PalmForwardHandUp-1@CenterChesthigh-FingerUp RoundHoriz C@NearFinger-PalmBackHandUp-1@CenterChesthigh-FingerUp

- Arabic: ثَقَافَة (ar) (ṯaqāfa)

- Bashkir: мәҙәниәт (mäðäniät)

- Bavarian: Kuitua

- Bulgarian: култу́ра (bg) f (kultúra)

- Danish: kultur (da) c

- Finnish: kulttuuri (fi)

- German: Kultur (de) f

- Greek: πολιτισμός (el) m (politismós), νοοτροπία (el) f (nootropía)

- Hebrew: תַּרְבּוּת (he) f (tarbút)

- Hungarian: kultúra (hu)

- Kalmyk: сойл (soyl)

- Khmer: វប្បធម៌ (km) (vŏəppaʼthɔə)

- Malagasy: finoana (mg)

- Maori: ahurea, tikanga

- Norwegian: kultur (no) m

- Persian: فرهنگ (fa) (farhang)

- Portuguese: cultura (pt) f

- Romanian: cultură (ro) f

- Russian: культу́ра (ru) f (kulʹtúra)

- Scottish Gaelic: cultar m

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: култу́ра f

- Roman: kultúra (sh) f

- Sicilian: curtura f

- Swedish: kultur (sv) c

- Tagalog: kultura, pamumuhay

- Telugu: సంస్కృతి (te) (saṁskr̥ti), సంప్రదాయము (te) (sampradāyamu)

- Turkish: kültür (tr)

- Yiddish: קולטור f (kultur)

Verb[edit]

culture (third-person singular simple present cultures, present participle culturing, simple past and past participle cultured)

- (transitive) to maintain in an environment suitable for growth (especially of bacteria) (compare cultivate)

- (transitive) to increase the artistic or scientific interest (in something) (compare cultivate)

[edit]

- acculturation

- cult

- cultivate

- cultural

- cultural criticism

- culturally

- culture shock

- cultured

- horticulture

Translations[edit]

to maintain in an environment suitable for growth

- Czech: kultivovat

- Finnish: viljellä (fi)

- French: cultiver (fr)

- Greek: καλλιεργώ (el) (kalliergó)

- Italian: coltivare (it)

- Macedonian: одгледува (odgleduva)

- Portuguese: cultivar (pt)

- Romanian: cultiva (ro)

- Spanish: cultivar (es)

- Telugu: అనుకూల వాతావరణం (anukūla vātāvaraṇaṁ)

References[edit]

- culture at OneLook Dictionary Search

- culture in Keywords for Today: A 21st Century Vocabulary, edited by The Keywords Project, Colin MacCabe, Holly Yanacek, 2018.

- «culture» in Raymond Williams, Keywords (revised), 1983, Fontana Press, page 87.

- “culture”, in The Century Dictionary […], New York, N.Y.: The Century Co., 1911, →OCLC.

French[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From Latin cultūra (“cultivation; culture”), from cultus, perfect passive participle of colō (“till, cultivate, worship”), from Proto-Indo-European *kʷel- (“to move; to turn (around)”).

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /kyl.tyʁ/

Noun[edit]

culture f (plural cultures)

- crop

- culture (“arts, customs and habits”)

Derived terms[edit]

- bouillon de culture

- culture générale

- neige de culture

Descendants[edit]

- → Turkish: kültür

Further reading[edit]

- “culture”, in Trésor de la langue française informatisé [Digitized Treasury of the French Language], 2012.

Friulian[edit]

Noun[edit]

culture f (plural culturis)

- culture

[edit]

- culturâl

Italian[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /kulˈtu.re/

- Rhymes: -ure

- Hyphenation: cul‧tù‧re

Noun[edit]

culture f

- plural of cultura

Latin[edit]

Participle[edit]

cultūre

- vocative masculine singular of cultūrus

Middle English[edit]

Noun[edit]

culture

- Alternative form of culter

Spanish[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /kulˈtuɾe/ [kul̪ˈt̪u.ɾe]

- Rhymes: -uɾe

- Syllabification: cul‧tu‧re

Verb[edit]

culture

- inflection of culturar:

- first/third-person singular present subjunctive

- third-person singular imperative

Culture is one of the most important creations from human beings. One of the primary ways that humans are separated from the rest of living creatures is based on the fact that we have enough organization and awareness to develop unique cultures and communities.

Even if culture isn’t something that you think about often, it’s something that you interact with every single day. Virtually every person is in a specific social group or a particular group of people, influencing their preferences, tastes, and decisions. Knowing how to appreciate and differentiate between these cultures is both tricky and incredibly important.

If you want to live the most fruitful life possible in the world today, learning how to integrate and interact with culture is one of the most important steps you can take. This is what culture is, where the word itself comes from, and how it works in the world today.

What Is Culture?

The definition of culture (ˈ k ʌ l tʃ ər) in the English dictionary is the arts, customs, achievements, and collective attitudes of a specific social group or location. While there may be similarities between cultures, each culture has its own aspects, quirks, and elements.

One of the most common ways that cultures are created is through people who share the same ethnicity or physical location. For example, American culture will be different from African or European culture, and New York culture will be different from Chicago culture. Similarly, cultures can differ depending on personal factors, including race, age, religion, and even musical preference.

Culture is also found inside different organizations and companies. This is typically referred to as corporate culture. At the end of the day, you will have a different set of written or unwritten rules virtually anywhere that need to be followed. These rules can dictate peoples’ attitudes toward life and the rest of the world.

Anthropologists are the people that study the different aspects of cultures. But you don’t need to get a college degree to look into culture — just looking at the popular culture around you can help you understand what culture is and how it works. Just remember that while your own culture is unique, other cultures are just as valid as your own!

What Is the Etymology of Culture?

The word culture is fascinating because it comes from many words in other languages, but all of those words came from the same word. It’s the epitome of a romance language word, and it goes to show that language at large is both deeply interconnected and constantly shifting.