This article is about the mental process. For the journal, see Cognition (journal).

Cognition refers to «the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses».[2] It encompasses all aspects of intellectual functions and processes such as: perception, attention, thought, intelligence, the formation of knowledge, memory and working memory, judgment and evaluation, reasoning and computation, problem solving and decision making, comprehension and production of language. Imagination is also a cognitive process, it is considered as such because it involves thinking about possibilities. Cognitive processes use existing knowledge and discover new knowledge.

Cognitive processes are analyzed from different perspectives within different contexts, notably in the fields of linguistics, musicology, anesthesia, neuroscience, psychiatry, psychology, education, philosophy, anthropology, biology, systemics, logic, and computer science.[3] These and other approaches to the analysis of cognition (such as embodied cognition) are synthesized in the developing field of cognitive science, a progressively autonomous academic discipline.

Etymology[edit]

The word cognition dates back to the 15th century, where it meant «thinking and awareness».[4] The term comes from the Latin noun cognitio (‘examination,’ ‘learning,’ or ‘knowledge’), derived from the verb cognosco, a compound of con (‘with’) and gnōscō (‘know’). The latter half, gnōscō, itself is a cognate of a Greek verb, gi(g)nósko (γι(γ)νώσκω, ‘I know,’ or ‘perceive’).[5][6]

Early studies[edit]

Despite the word cognitive itself dating back to the 15th century,[4] attention to cognitive processes came about more than eighteen centuries earlier, beginning with Aristotle (384–322 BC) and his interest in the inner workings of the mind and how they affect the human experience. Aristotle focused on cognitive areas pertaining to memory, perception, and mental imagery. He placed great importance on ensuring that his studies were based on empirical evidence, that is, scientific information that is gathered through observation and conscientious experimentation.[7] Two millennia later, the groundwork for modern concepts of cognition was laid during the Enlightenment by thinkers such as John Locke and Dugald Stewart who sought to develop a model of the mind in which ideas were acquired, remembered and manipulated.[8]

During the early nineteenth century cognitive models were developed both in philosophy—particularly by authors writing about the philosophy of mind—and within medicine, especially by physicians seeking to understand how to cure madness. In Britain, these models were studied in the academy by scholars such as James Sully at University College London, and they were even used by politicians when considering the national Elementary Education Act of 1870.[9]

As psychology emerged as a burgeoning field of study in Europe, whilst also gaining a following in America, scientists such as Wilhelm Wundt, Herman Ebbinghaus, Mary Whiton Calkins, and William James would offer their contributions to the study of human cognition.

Early theorists[edit]

Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) emphasized the notion of what he called introspection: examining the inner feelings of an individual. With introspection, the subject had to be careful to describe their feelings in the most objective manner possible in order for Wundt to find the information scientific.[10][11] Though Wundt’s contributions are by no means minimal, modern psychologists find his methods to be too subjective and choose to rely on more objective procedures of experimentation to make conclusions about the human cognitive process.

Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850–1909) conducted cognitive studies that mainly examined the function and capacity of human memory. Ebbinghaus developed his own experiment in which he constructed over 2,000 syllables made out of nonexistent words (for instance, ‘EAS’). He then examined his own personal ability to learn these non-words. He purposely chose non-words as opposed to real words to control for the influence of pre-existing experience on what the words might symbolize, thus enabling easier recollection of them.[10][12] Ebbinghaus observed and hypothesized a number of variables that may have affected his ability to learn and recall the non-words he created. One of the reasons, he concluded, was the amount of time between the presentation of the list of stimuli and the recitation or recall of the same. Ebbinghaus was the first to record and plot a «learning curve» and a «forgetting curve».[13] His work heavily influenced the study of serial position and its effect on memory (discussed further below).

Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930) was an influential American pioneer in the realm of psychology. Her work also focused on human memory capacity. A common theory, called the recency effect, can be attributed to the studies that she conducted.[14] The recency effect, also discussed in the subsequent experiment section, is the tendency for individuals to be able to accurately recollect the final items presented in a sequence of stimuli. Calkin’s theory is closely related to the aforementioned study and conclusion of the memory experiments conducted by Hermann Ebbinghaus.[15]

William James (1842–1910) is another pivotal figure in the history of cognitive science. James was quite discontent with Wundt’s emphasis on introspection and Ebbinghaus’ use of nonsense stimuli. He instead chose to focus on the human learning experience in everyday life and its importance to the study of cognition. James’ most significant contribution to the study and theory of cognition was his textbook Principles of Psychology which preliminarily examines aspects of cognition such as perception, memory, reasoning, and attention.[15]

René Descartes (1596-1650) was a seventeenth-century philosopher who came up with the phrase «Cogito, ergo sum.» Which means «I think, therefore I am.» He took a philosophical approach to the study of cognition and the mind, with his Meditations he wanted people to meditate along with him to come to the same conclusions as he did but in their own free cognition.[16]

Psychology[edit]

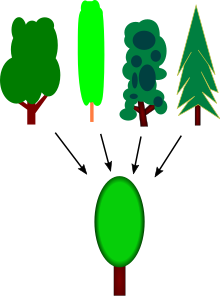

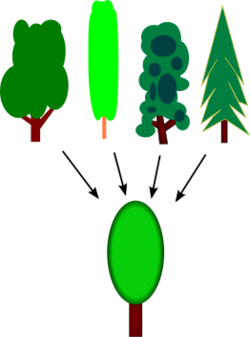

When the mind makes a generalization such as the concept of tree, it extracts similarities from numerous examples; the simplification enables higher-level thinking (abstract thinking).

In psychology, the term «cognition» is usually used within an information processing view of an individual’s psychological functions,[17] and such is the same in cognitive engineering.[18] In the study of social cognition, a branch of social psychology, the term is used to explain attitudes, attribution, and group dynamics.[17] However, psychological research within the field of cognitive science has also suggested an embodied approach to understanding cognition. Contrary to the traditional computationalist approach, embodied cognition emphasizes the body’s significant role in the acquisition and development of cognitive capabilities.[19][20]

Human cognition is conscious and unconscious, concrete or abstract, as well as intuitive (like knowledge of a language) and conceptual (like a model of a language). It encompasses processes such as memory, association, concept formation, pattern recognition, language, attention, perception, action, problem solving, and mental imagery.[21][22] Traditionally, emotion was not thought of as a cognitive process, but now much research is being undertaken to examine the cognitive psychology of emotion; research is also focused on one’s awareness of one’s own strategies and methods of cognition, which is called metacognition. The concept of cognition has gone through several revisions through the development of disciplines within psychology.

Psychologists initially understood cognition governing human action as information processing. This was a movement known as cognitivism in the 1950s, emerging after the Behaviorist movement viewed cognition as a form of behavior.[23] Cognitivism approached cognition as a form of computation, viewing the mind as a machine and consciousness as an executive function.[19] However; post cognitivism began to emerge in the 1990s as the development of cognitive science presented theories that highlighted the necessity of cognitive action as embodied, extended, and producing dynamic processes in the mind.[24] The development of Cognitive psychology arose as psychology from different theories, and so began exploring these dynamics concerning mind and environment, starting a movement from these prior dualist paradigms that prioritized cognition as systematic computation or exclusively behavior.[19]

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development[edit]

For years, sociologists and psychologists have conducted studies on cognitive development, i.e. the construction of human thought or mental processes.

Jean Piaget was one of the most important and influential people in the field of developmental psychology. He believed that humans are unique in comparison to animals because we have the capacity to do «abstract symbolic reasoning». His work can be compared to Lev Vygotsky, Sigmund Freud, and Erik Erikson who were also great contributors in the field of developmental psychology. Today, Piaget is known for studying the cognitive development in children, having studied his own three children and their intellectual development, from which he would come to a theory of cognitive development that describes the developmental stages of childhood.[25]

| Stage | Age or Period | Description[26] |

|---|---|---|

| Sensorimotor stage | Infancy (0–2 years) | Intelligence is present; motor activity but no symbols; knowledge is developing yet limited; knowledge is based on experiences/ interactions; mobility allows the child to learn new things; some language skills are developed at the end of this stage. The goal is to develop object permanence, achieving a basic understanding of causality, time, and space. |

| Preoperational stage | Toddler and Early Childhood (2–7 years) | Symbols or language skills are present; memory and imagination are developed; non-reversible and non-logical thinking; shows intuitive problem solving; begins to perceive relationships; grasps the concept of conservation of numbers; predominantly egocentric thinking. |

| Concrete operational stage | Elementary and Early Adolescence (7–12 years) | Logical and systematic form of intelligence; manipulation of symbols related to concrete objects; thinking is now characterized by reversibility and the ability to take the role of another; grasps concepts of the conservation of mass, length, weight, and volume; predominantly operational thinking; nonreversible and egocentric thinking |

| Formal operational stage | Adolescence and Adulthood (12 years and on) | Logical use of symbols related to abstract concepts; Acquires flexibility in thinking as well as the capacities for abstract thinking and mental hypothesis testing; can consider possible alternatives in complex reasoning and problem-solving. |

Common types of tests on human cognition[edit]

Serial position

The serial position experiment is meant to test a theory of memory that states that when information is given in a serial manner, we tend to remember information at the beginning of the sequence, called the primacy effect, and information at the end of the sequence, called the recency effect. Consequently, information given in the middle of the sequence is typically forgotten, or not recalled as easily. This study predicts that the recency effect is stronger than the primacy effect, because the information that is most recently learned is still in working memory when asked to be recalled. Information that is learned first still has to go through a retrieval process. This experiment focuses on human memory processes.[27]

Word superiority

The word superiority experiment presents a subject with a word, or a letter by itself, for a brief period of time, i.e. 40ms, and they are then asked to recall the letter that was in a particular location in the word. In theory, the subject should be better able to correctly recall the letter when it was presented in a word than when it was presented in isolation. This experiment focuses on human speech and language.[28]

Brown-Peterson

In the Brown-Peterson experiment, participants are briefly presented with a trigram and in one particular version of the experiment, they are then given a distractor task, asking them to identify whether a sequence of words is in fact words, or non-words (due to being misspelled, etc.). After the distractor task, they are asked to recall the trigram from before the distractor task. In theory, the longer the distractor task, the harder it will be for participants to correctly recall the trigram. This experiment focuses on human short-term memory.[29]

Memory span

During the memory span experiment, each subject is presented with a sequence of stimuli of the same kind; words depicting objects, numbers, letters that sound similar, and letters that sound dissimilar. After being presented with the stimuli, the subject is asked to recall the sequence of stimuli that they were given in the exact order in which it was given. In one particular version of the experiment, if the subject recalled a list correctly, the list length was increased by one for that type of material, and vice versa if it was recalled incorrectly. The theory is that people have a memory span of about seven items for numbers, the same for letters that sound dissimilar and short words. The memory span is projected to be shorter with letters that sound similar and with longer words.[30]

Visual search

In one version of the visual search experiment, a participant is presented with a window that displays circles and squares scattered across it. The participant is to identify whether there is a green circle on the window. In the featured search, the subject is presented with several trial windows that have blue squares or circles and one green circle or no green circle in it at all. In the conjunctive search, the subject is presented with trial windows that have blue circles or green squares and a present or absent green circle whose presence the participant is asked to identify. What is expected is that in the feature searches, reaction time, that is the time it takes for a participant to identify whether a green circle is present or not, should not change as the number of distractors increases. Conjunctive searches where the target is absent should have a longer reaction time than the conjunctive searches where the target is present. The theory is that in feature searches, it is easy to spot the target, or if it is absent, because of the difference in color between the target and the distractors. In conjunctive searches where the target is absent, reaction time increases because the subject has to look at each shape to determine whether it is the target or not because some of the distractors if not all of them, are the same color as the target stimuli. Conjunctive searches where the target is present take less time because if the target is found, the search between each shape stops.[31]

Knowledge representation

The semantic network of knowledge representation systems have been studied in various paradigms. One of the oldest paradigms is the leveling and sharpening of stories as they are repeated from memory studied by Bartlett. The semantic differential used factor analysis to determine the main meanings of words, finding that value or «goodness» of words is the first factor. More controlled experiments examine the categorical relationships of words in free recall. The hierarchical structure of words has been explicitly mapped in George Miller’s Wordnet. More dynamic models of semantic networks have been created and tested with neural network experiments based on computational systems such as latent semantic analysis (LSA), Bayesian analysis, and multidimensional factor analysis. The semantics (meaning) of words is studied by all the disciplines of cognitive science.[32]

Metacognition[edit]

Metacognition is an awareness of one’s thought processes and an understanding of the patterns behind them. The term comes from the root word meta, meaning «beyond», or «on top of».[33] Metacognition can take many forms, such as reflecting on one’s ways of thinking and knowing when and how to use particular strategies for problem-solving.[33] There are generally two components of metacognition: (1) knowledge about cognition and (2) regulation of cognition.[34]

Metamemory, defined as knowing about memory and mnemonic strategies, is an especially important form of metacognition.[35] Academic research on metacognitive processing across cultures is in the early stages, but there are indications that further work may provide better outcomes in cross-cultural learning between teachers and students.[36]

Writings on metacognition date back at least as far as two works by the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC): On the Soul and the Parva Naturalia.[37]

Improving cognition[edit]

Physical exercise[edit]

Aerobic and anaerobic exercise have been studied concerning cognitive improvement.[38] There appear to be short-term increases in attention span, verbal and visual memory in some studies. However, the effects are transient and diminish over time, after cessation of the physical activity.[39]

Dietary supplements[edit]

Studies evaluating phytoestrogen, blueberry supplementation and antioxidants showed minor increases in cognitive function after supplementation but no significant effects compared to placebo.[40][41][42]

[edit]

Exposing individuals with cognitive impairment (i.e., Dementia) to daily activities designed to stimulate thinking and memory in a social setting, seems to improve cognition. Although study materials are small, and larger studies need to confirm the results, the effect of social cognitive stimulation seems to be larger than the effects of some drug treatments.[43]

Other methods[edit]

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) has been shown to improve cognition in individuals without dementia 1 month after treatment session compared to before treatment. The effect was not significantly larger compared to placebo.[44] Computerized cognitive training, utilising a computer based training regime for different cognitive functions has been examined in a clinical setting but no lasting effects has been shown.[45]

See also[edit]

- Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument

- Cognitive biology

- Cognitive computing

- Cognitive holding power

- Cognitive liberty

- Cognitive musicology

- Cognitive psychology

- Cognitive science

- Cognitivism

- Comparative cognition

- Embodied cognition

- Information processing technology and aging

- Mental chronometry – i.e., the measuring of cognitive processing speed

- Nootropic

- Outline of human intelligence – a list of traits, capacities, models, and research fields of human intelligence, and more.

- Outline of thought – a list that identifies many types of thoughts, types of thinking, aspects of thought, related fields, and more.

References[edit]

- ^ Fludd, Robert. «De tripl. animae in corp. vision.» Tract. I, sect. I, lib. X in Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris metaphysica, physica atqve technica historia, vol. II. p. 217.

- ^ «Cognition». Lexico. Oxford University Press and Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ Von Eckardt B (1996). What is cognitive science?. Princeton, MA: MIT Press. pp. 45–72. ISBN 9780262720236.

- ^ a b Revlin R. Cognition: Theory and Practice.

- ^ Liddell HG, Scott R (1940). Jones HS, McKenzie R (eds.). «γιγνώσκω». A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press – via Perseus Project.

- ^ Franchi S, Bianchini F (2011). «On The Historical Dynamics Of Cognitive Science: A View From The Periphery.». The Search for a Theory of Cognition: Early Mechanisms and New Ideas. Amsterdam: Rodopi. p. XIV.

- ^ Matlin M (2009). Cognition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 4.

- ^ Eddy MD. «The Cognitive Unity of Calvinist Pedagogy in Enlightenment Scotland». Ábrahám Kovács (Ed.), Reformed Churches Working Unity in Diversity: Global Historical, Theological and Ethical Perspectives (Budapest: l’Harmattan, 2016): 46–60.

- ^ Eddy MD (December 2017). «The politics of cognition: liberalism and the evolutionary origins of Victorian education». British Journal for the History of Science. 50 (4): 677–699. doi:10.1017/S0007087417000863. PMID 29019300.

- ^ a b Fuchs AH, Milar KJ (2003). «Psychology as a science». Handbook of Psychology. 1 (The history of psychology): 1–26. doi:10.1002/0471264385.wei0101. ISBN 0471264385.

- ^ Zangwill OL (2004). The Oxford companion to the mind. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 951–952.

- ^ Zangwill OL (2004). The Oxford companion to the mind. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 276.

- ^ Brink TL (2008). ««Memory.» Unit 7″. Psychology: A Student Friendly Approach. p. 126.

- ^ Madigan S, O’Hara R (1992). «Short-term memory at the turn of the century: Mary Whiton Calkin’s memory research». American Psychologist. 47 (2): 170–174. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.47.2.170.

- ^ a b Matlin M (2009). Cognition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 5.

- ^ «René Descartes». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ a b Sternberg RJ, Sternberg K (2009). Cognitive Psychology (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

- ^ Blomberg O (2011). «Concepts of cognition for cognitive engineering». International Journal of Aviation Psychology. 21 (1): 85–104. doi:10.1080/10508414.2011.537561. S2CID 144876967.

- ^ a b c Paco Calvo; Antoni Gomila, eds. (2008). Handbook of cognitive science: an embodied approach. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-08-091487-9. OCLC 318353781.

- ^ Lakoff, George (2012). «Explaining Embodied Cognition Results». Topics in Cognitive Science. 4 (4): 773–785. doi:10.1111/j.1756-8765.2012.01222.x. ISSN 1756-8757. PMID 22961950. S2CID 18978114.

- ^ Coren, Stanley, Lawrence M. Ward, and James T. Enns. 1999. Sensation and Perception (5th ed.). Harcourt Brace. ISBN 978-0-470-00226-1. p. 9.

- ^ Best JB (1999). Cognitive Psychology (5th ed.). pp. 15–17.

- ^ Pyszczynski, Tom; Greenberg, Jeff; Koole, Sander; Solomon, Sheldon (2010-06-30). «Experimental Existential Psychology: Coping With the Facts of Life». In Fiske, Susan T.; Gilbert, Daniel T.; Lindzey, Gardner (eds.). Handbook of Social Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. socpsy001020. doi:10.1002/9780470561119.socpsy001020. ISBN 978-0-470-56111-9.

- ^ Zelazo, Philip David; Moscovitch, Morris; Thompson, Evan, eds. (2007). The Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511816789. ISBN 9780511816789.

- ^ Cherry K. «Jean Piaget Biography». The New York Times Company. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ Parke RD, Gauvain M (2009). Child Psychology: A Contemporary Viewpoint (7th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Surprenant AM (May 2001). «Distinctiveness and serial position effects in tonal sequences». Perception & Psychophysics. 63 (4): 737–45. doi:10.3758/BF03194434. PMID 11436742.

- ^ Krueger LE (November 1992). «The word-superiority effect and phonological recoding». Memory & Cognition. 20 (6): 685–94. doi:10.3758/BF03202718. PMID 1435271.

- ^ Nairne J, Whiteman H, Kelley M (1999). «Short-term forgetting of order under conditions of reduced interference» (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology A. 52: 241–251. doi:10.1080/713755806. S2CID 15713857.

- ^ May CP, Hasher L, Kane MJ (September 1999). «The role of interference in memory span». Memory & Cognition. 27 (5): 759–67. doi:10.3758/BF03198529. PMID 10540805.

- ^ Wolfe J, Cave K, Franzel S (1989). «Guided search: An alternative to the feature integration model for visual search». Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 15 (3): 419–433. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.551.1667. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.15.3.419. PMID 2527952.

- ^ Pinker S, Bloom P (December 1990). «Natural language and natural selection». Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 13 (4): 707–727. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00081061. S2CID 6167614.

- ^ a b Metcalfe, J., & Shimamura, A. P. (1994). Metacognition: knowing about knowing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- ^ Schraw, Gregory (1998). «Promoting general metacognitive awareness». Instructional Science. 26: 113–125. doi:10.1023/A:1003044231033. S2CID 15715418.

- ^ Dunlosky, J. & Bjork, R. A. (Eds.). Handbook of Metamemory and Memory. Psychology Press: New York, 2008.

- ^ Wright, Frederick. APERA Conference 2008. 14 April 2009. http://www.apera08.nie.edu.sg/proceedings/4.24.pdf Archived 4 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^

Colman, Andrew M. (2001). «metacognition». A Dictionary of Psychology. Oxford Paperback Reference (4 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press (published 2015). p. 456. ISBN 9780199657681. Retrieved 17 May 2017.Writings on metacognition can be traced back at least as far as De Anima and the Parva Naturalia of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BC) […].

- ^ Sanders LM, Hortobágyi T, la Bastide-van Gemert S, van der Zee EA, van Heuvelen MJ (2019-01-10). Regnaux JP (ed.). «Dose-response relationship between exercise and cognitive function in older adults with and without cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis». PLOS ONE. 14 (1): e0210036. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1410036S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0210036. PMC 6328108. PMID 30629631.

- ^ Young J, Angevaren M, Rusted J, Tabet N, et al. (Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group) (April 2015). «Aerobic exercise to improve cognitive function in older people without known cognitive impairment». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD005381. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005381.pub4. PMID 25900537.

- ^ Barfoot KL, May G, Lamport DJ, Ricketts J, Riddell PM, Williams CM (October 2019). «The effects of acute wild blueberry supplementation on the cognition of 7-10-year-old schoolchildren». European Journal of Nutrition. 58 (7): 2911–2920. doi:10.1007/s00394-018-1843-6. PMC 6768899. PMID 30327868.

- ^ Thaung Zaw JJ, Howe PR, Wong RH (September 2017). «Does phytoestrogen supplementation improve cognition in humans? A systematic review». Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1403 (1): 150–163. Bibcode:2017NYASA1403..150T. doi:10.1111/nyas.13459. PMID 28945939. S2CID 25280760.

- ^ Sokolov AN, Pavlova MA, Klosterhalfen S, Enck P (December 2013). «Chocolate and the brain: neurobiological impact of cocoa flavanols on cognition and behavior». Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 37 (10 Pt 2): 2445–53. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.06.013. PMID 23810791. S2CID 17371625.

- ^ Woods B, Aguirre E, Spector AE, Orrell M, et al. (Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group) (February 2012). «Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005562. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005562.pub2. PMID 22336813. S2CID 7086782.

- ^ Trung J, Hanganu A, Jobert S, Degroot C, Mejia-Constain B, Kibreab M, et al. (September 2019). «Transcranial magnetic stimulation improves cognition over time in Parkinson’s disease». Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 66: 3–8. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.07.006. PMID 31300260. S2CID 196350357.

- ^ Gates NJ, Rutjes AW, Di Nisio M, Karim S, Chong LY, March E, et al. (Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group) (February 2020). «Computerised cognitive training for 12 or more weeks for maintaining cognitive function in cognitively healthy people in late life». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (2): CD012277. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012277.pub3. PMC 7045394. PMID 32104914.

Further reading[edit]

- Ardila A (2018). Historical Development of Human Cognition. A Cultural-Historical Neuropsychological Perspective. Springer. ISBN 978-9811068867.

- Coren S, Ward LM, Enns JT (1999). Sensation and Perception. Harcourt Brace. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-470-00226-1.

- Lycan WG, ed. (1999). Mind and Cognition: An Anthology (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Stanovich, Keith (2009). What Intelligence Tests Miss: The Psychology of Rational Thought. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12385-2.

External links[edit]

Wikiversity has learning resources about Cognition

Look up cognition in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Cognition An international journal publishing theoretical and experimental papers on the study of the mind.

- Information on music cognition, University of Amsterdam

- Cognitie.NL Archived 2011-10-19 at the Wayback Machine Information on cognition research, Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and University of Amsterdam (UvA)

- Emotional and Decision Making Lab, Carnegie Mellon, EDM Lab

- The Limits of Human Cognition – an article describing the evolution of mammals’ cognitive abilities

- Half-heard phone conversations reduce cognitive performance

- The limits of intelligence Douglas Fox, Scientific American, 14 June 14, 2011.

Cognition is a term referring to the mental processes involved in gaining knowledge and comprehension. Some of the many different cognitive processes include thinking, knowing, remembering, judging, and problem-solving.

These are higher-level functions of the brain and encompass language, imagination, perception, and planning. Cognitive psychology is the field of psychology that investigates how people think and the processes involved in cognition.

Hot Cognition vs. Cold Cognition

Some split cognition into two categories: hot and cold. Hot cognition refers to mental processes in which emotion plays a role, such as reward-based learning. Conversely, cold cognition refers to mental processes that don’t involve feelings or emotions, such as working memory.

History of the Study of Cognition

The study of how humans think dates back to the time of ancient Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle.

Philosophical Origins

Plato’s approach to the study of the mind suggested that people understand the world by first identifying basic principles buried deep inside themselves, then using rational thought to create knowledge. This viewpoint was later advocated by philosophers such as Rene Descartes and linguist Noam Chomsky. It is often referred to as rationalism.

Aristotle, on the other hand, believed that people acquire knowledge through their observations of the world around them. Later thinkers such as John Locke and B.F. Skinner also advocated this point of view, which is often referred to as empiricism.

Early Psychology

During the earliest days of psychology—and for the first half of the 20th century—psychology was largely dominated by psychoanalysis, behaviorism, and humanism.

Eventually, a formal field of study devoted solely to the study of cognition emerged as part of the «cognitive revolution» of the 1960s. This field is known as cognitive psychology.

The Emergence of Cognitive Psychology

One of the earliest definitions of cognition was presented in the first textbook on cognitive psychology, which was published in 1967. According to Ulric Neisser, a psychologist and the book’s author, cognition is «those processes by which the sensory input is transformed, reduced, elaborated, stored, recovered, and used.»

Types of Cognitive Processes

There are many different types of cognitive processes. They include:

- Attention: Attention is a cognitive process that allows people to focus on a specific stimulus in the environment.

- Language: Language and language development are cognitive processes that involve the ability to understand and express thoughts through spoken and written words. This allows us to communicate with others and plays an important role in thought.

- Learning: Learning requires cognitive processes involved in taking in new things, synthesizing information, and integrating it with prior knowledge.

- Memory: Memory is an important cognitive process that allows people to encode, store, and retrieve information. It is a critical component in the learning process and allows people to retain knowledge about the world and their personal histories.

- Perception: Perception is a cognitive process that allows people to take in information through their senses, then utilize this information to respond and interact with the world.

- Thought: Thought is an essential part of every cognitive process. It allows people to engage in decision-making, problem-solving, and higher reasoning.

What Can Affect Cognition?

It is important to remember that these cognitive processes are complex and often imperfect. Some of the factors that can affect or influence cognition include:

Age

Research indicates that as we age, our cognitive function tends to decline. Age-related cognitive changes include processing things more slowly, finding it harder to recall past events, and a failure to remember information that was once known (such as how to solve a particular math equation or historical information).

Attention Issues

Selective attention is a limited resource, so there are a number of things that can make it difficult to focus on everything in your environment. Attentional blink, for example, happens when you are so focused on one thing that you completely miss something else happening right in front of you.

Cognitive Biases

Cognitive biases are systematic errors in thinking related to how people process and interpret information about the world. Confirmation bias is one common example that involves only paying attention to information that aligns with your existing beliefs while ignoring evidence that doesn’t support your views.

Genetics

Some studies have connected cognitive function with certain genes. For example, a 2020 study published in Brain Communications found that a person’s level of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is 30% determined by heritability, can impact the rate of brain neurodegeneration, a condition that ultimately impacts cognitive function.

Memory Limitations

Short-term memory is surprisingly brief, typically lasting just 20 to 30 seconds, whereas long-term memory can be stable and enduring, with memories lasting years and even decades. Memory can also be fragile and fallible. Sometimes we forget and other times we are subject to misinformation effects that may even lead to the formation of false memories.

Cognitive processes affect every aspect of life, from school to work to relationships. Some specific uses for these processes include the following.

Learning New Things

Learning requires being able to take in new information, form new memories, and make connections with other things that you already know. Researchers and educators use their knowledge of these cognitive processes to create instructive materials to help people learn new concepts.

Forming Memories

Memory is a major topic of interest in the field of cognitive psychology. How we remember, what we remember, and what we forget reveal a great deal about how cognitive processes operate.

While people often think of memory as being much like a video camera—carefully recording, cataloging, and storing life events away for later recall—research has found that memory is much more complex.

Making Decisions

Whenever people make any type of a decision, it involves making judgments about things they have processed. This might involve comparing new information to prior knowledge, integrating new information into existing ideas, or even replacing old knowledge with new knowledge before making a choice.

Impact of Cognition

Our cognitive processes have a wide-ranging impact that influences everything from our daily life to our overall health.

Perceiving the World

As you take in sensations from the world around you, the information that you see, hear, taste, touch, and smell must first be transformed into signals that the brain can understand. The perceptual process allows you to take in this sensory information and convert it into a signal that your brain can recognize and act upon.

Forming Impressions

The world is full of an endless number of sensory experiences. To make meaning out of all this incoming information, it is important for the brain to be able to capture the fundamentals. Events are reduced to only the critical concepts and ideas that we need.

Filling in the Gaps

In addition to reducing information to make it more memorable and understandable, people also elaborate on these memories as they reconstruct them. In some cases, this elaboration happens when people are struggling to remember something. When the information cannot be recalled, the brain sometimes fills in the missing data with whatever seems to fit.

Interacting With the World

Cognition involves not only the things that go on inside our heads but also how these thoughts and mental processes influence our actions. Our attention to the world around us, memories of past events, understanding of language, judgments about how the world works, and abilities to solve problems all contribute to how we behave and interact with our surrounding environment.

Tips for Improving Cognition

Cognitive processes are influenced by a range of factors, including genetics and experiences. While you cannot change your genes or age, there are things that you can do to protect and maximize your cognitive abilities:

- Stay healthy. Lifestyle factors such as eating a nutritious diet and getting regular exercise can have a positive effect on cognitive functioning.

- Think critically. Question your assumptions and ask questions about your thoughts, beliefs, and conclusions.

- Stay curious and keep learning. A great way to flex your cognitive abilities is to keep challenging yourself to learn more about the world.

- Skip multitasking. While it might seem like doing several things at once would help you get done faster, research has shown it actually decreases both productivity and work quality.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Does cognition mean thinking?

Thinking is an important component, but cognition also encompasses unconscious and perceptual processes as well. In addition to thinking, cognition involves language, attention, learning, memory, and perception.

-

What is an example of cognition?

Cognition includes all of the conscious and unconscious processes involved in thinking, perceiving, and reasoning. Examples of cognition include paying attention to something in the environment, learning something new, making decisions, processing language, sensing and perceiving environmental stimuli, solving problems, and using memory.

-

What are the 5 cognitive skills?

People utilize cognitive skills to think, learn, recall, and reason. Five important cognitive skills include short-term memory, logic, processing speed, attention, and spatial recognition.

Cognition can be defined as the capacity to process information through the perception of all senses, knowledge accumulated through experience, and the personal attributes that enable us to integrate all information received to evaluate and interpret the world around us.

What Is Cognition?

Cognition, in psychology, is a term used to define how the brain processes information that is acquired through knowledge, understanding, and experience. The word cognition comes from the Latin word “cognoscere” which means “to know”. Human cognition can be defined as the ability to understand and process information that is perceived and acquired which is converted into knowledge and experience. It includes different types of cognitive processes such as learning, attention, memory, language, reasoning, decision making, or perception. In the case of social cognition, this term is used to explain attitudes, attribution, and group dynamics.

According to a 2015 study 1 , it refers to “the ability to learn, solve problems, remember, and appropriately use stored information,” and is considered as “a key to successful health and aging.” The cognitive process involves mentally gaining comprehension and expertise by utilizing senses, experience and thought. It involves a number of different mental functions like learning, using language, making decisions, using logic & reasoning, evaluation, memory, judgment and problem solving. It includes different conscious & unconscious states, processes and actions involved in gathering knowledge. Research 2 shows that cognitive processes involve elements of modular processing to create mechanisms that regulate “stimulus and response.” However, according to a 2015 study 3 , our cognitive abilities tend to decline as we age. The study suggests that our cognitive abilities are crucial for functional independence as we get older. It enables a person to care for themselves, perform regular functions and live independently. “In addition, intact cognition is vital for humans to communicate effectively, including processing and integrating sensory information and responding appropriately to others,” the study adds.

Understanding Cognition

Cognitive psychology emerged in the late 1950s. Psychologists like Piaget and Vygotsky revolutionized the concept with their theories about development and cognitive learning. Piaget is known for studying cognitive development in children, having studied his own three children and their intellectual development. This contributed to the development of his concept “the theory of cognitive development” that describes the developmental stages of childhood. Vygotsky is known for his contribution to understanding cognitive biases. Over the decades’ interest in cognition and cognitive skills advanced and allowed researchers to learn more about how these processes work. Advancements in neuroimaging have helped to contribute to the physiological and neuroanatomical understanding of cognition.

Few people would deny that the cognitive process is a part of the brain function and cognitive theory will not necessarily make reference to the brain or to biological processes. Studies 4 were conducted on older humans to better understand the relation between the brain and cognition. Normal aging 5 results in the loss of brain tissue with markedly larger tissue loss found in the frontal, temporal and parietal cortices. Due to these cognitive functions, these brain regions 6 decay furthermore than any other aspects of cognition. However, it may purely be based on behavior in terms of information flow or function. The cognitive process mainly includes thinking, knowing, remembering, judging and problem-solving.

Types Of Cognitive Processes

There are several types of processes that are involved in cognition. They include:

1. Attention

Attention can be defined as the ability to focus on one particular task at a time. Attention is a fundamental aspect of conducting daily activities. This is used in the majority of tasks we do every day. Attention is considered to be a mechanism that controls and regulates the rest of the cognitive processes. This involves the perception of the senses, learning, and complex reasoning. The impact of emerging technologies on various mental functions is limitless. One 2019 study 7 suggested that the use of digital technologies for learning is having a negative impact on our brains and our attention span.

2. Language

Language is a communication form we use every day. Language involves reading, writing, speaking, and listening. Learning language involves the ability to comprehend and express oneself with spoken and written words. This cognitive function allows individuals to communicate and express their minds. This tool is used to communicate, organize, and transform information that we have about the world around us. There is a close connection between language and thought since they are both developed together. This connection tends to mutually influence each other. A study pointed out that many distinct domains of cognition exist and must be learned separately using different mental mechanisms, including language abilities.

3. Learning

Cognitive learning can be defined as a way of learning wherein the ulterior focus is on the effective use of the brain. This process aims to systemize the learning process through optimal thinking, understanding, and the retention capacity of the individual. Learning aims to inculcate new things, process information, integrate research with prior knowledge, and optimize the learning process. This can include things such as behaviors or habits like brushing teeth, learning how to walk, and the knowledge received through social interaction. A 2002 study 8 found that instructional methods can be incorporated into lesson design and improve learning by managing cognitive load in working memory. There are several benefits of cognitive learning. They are:

- Enhances learning

- Improves confidence

- Enhances comprehension

- Improves problem-solving skills

4. Memory

This process allows the ability to encode, store, and recover information received from the world around us and the past. One 2019 study 9 pointed out that memory is an essential component of the learning process that enables individuals to refer to the knowledge and experience received and utilize it in future decisions. Memory is a basic process for learning and acquiring new information. This function allows creating a sense of identity of the person.

Memory can be subdivided into short-term and long-term memory. Short-term memory is the ability to retain information for a short period of time. For instance, attempting to remember a telephone number until we can write it down. Long term memory is the ability to store and retain information for a long period of time. It can be further divided into smaller groups that include declarative memory and procedural memory. Declarative memory constitutes the knowledge received through language and education, and the knowledge gained through personal experience. Procedural memory involves learning through routines. Other types of memory include auditory memory, contextual memory, naming, and recognition.

5. Perception

Perception allows people to engulf information through their senses and utilize it based on the circumstances and their interaction with the world around them. This type of cognition allows us to organize and understand the world through different senses like sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. Most people rely on the five senses. However, other senses like proprioception i.e the stimuli which unconsciously perceive our position in space and judge spatial orientation, and interoception i.e the perception of the organs in our bodies. This enables us to know when you are hungry or thirsty. Once the brain receives the stimulation, it integrates all the information to create a memory.

6. Thought

Thought allows individuals to comprehend and develop their decision-making, problem-solving, reasoning skills and optimize them in the learning process. It refers to our ability to process and store information, hold attention and retrieve it as and when necessary. It allows us to integrate all of the information that we have received and is used to establish relationships between events and knowledge. In order to achieve this, it uses reasoning, synthesis, and problem-solving.

Why Cognition Is Important

The cognitive process affects almost every aspect of an individual’s life. The uses of cognition may be laid down as follows:

1. Learning things

Learning involves inculcating information, forming new memories, and building connections with the knowledge you already possess. Researchers and experts use their knowledge of what they learned and apply it to their studies. This enables them to create new instructions as a means to help other people learn new things.

2. Creating Memories

Cognition allows us to store information we have learned. Memory is one of the major aspects of the field of cognitive psychology. While memory may be considered in terms of videos or pictures or cataloging life events and storing them away to revisit later, research 10 has shown that memory is more complex than images or videos. The human brain stores information in its mind as a memory. The feelings associated with a particular event become a part of their memory. The information received may later be utilized in similar circumstances.

3. Decision Making

The decision-making process involves making judgments about the information received. It also may involve comparing information to prior knowledge, integration of new information into existing ideas and knowledge, or replacement of old information with new ones before passing a judgment.

Cognition And Aging

Cognitive abilities tend to decline as an individual ages. Cognitive decline is a condition characterized by a decline in cognitive functions related to thinking, memory, language, and judgment. Some cognitive abilities such as vocabulary are more resilient than others while others such as conceptual reasoning, memory, and processing speed may decline gradually with time. A 2010 study 11 pointed out that our ability to process information begins to decline in the third decade of life and continues to advance throughout the lifespan. This gradual decline can negatively impact the individual’s performance.

Memory issues are one of the most common signs of cognitive decline found in older adults. A 2003 study also suggested that decline occurs in memory retrieval, which refers to the ability to access newly learned information. The language abilities appear to remain intact as an individual ages. A 2009 study 12 found that vocabulary remains stable and even improves over time. However, it is also worth noting that some environmental factors 13 may also influence the development of an impaired cognitive function.

Read More About Aging Here

Cognition And Addiction

Clinical research 14 suggests that cues associated with substance use elicit psychological responses and cravings for drugs. Addiction is found to significantly impact different cognitive processes such as memory and language abilities, only when intoxicated. However, memory decline may persist if the individual has been diagnosed with alcohol use disorder. One 2007 study 15 also found that acute effects of amphetamine, nicotine, and cocaine display acutely enhanced learning and attention. A 2008 study 16 confirmed that laboratory animals’ cognitive processes improve immediately following the administration of nicotine. In another 2007 study 17 cocaine produced similar effects in a study of rats that were treated with the drug and then exposed to a sensory stimulus. The animals exhibited enhanced neural activation when later re-exposed to the stimulus.

Drug abusers in the second stage of addiction are subject to withdrawal symptoms when they initiate abstinence. Many drugs produce cognition-related withdrawal symptoms that may make the process of abstinence challenge. These include:

- Cocaine 18 – deficits in cognitive flexibility

- Amphetamine 19 —deficits in attention and impulse control

- Opioids—deficits in cognitive flexibility

- Alcohol—deficits in working memory and attention

- Cannabis—deficits in cognitive flexibility and attention

- Nicotine —deficits in working memory and declarative learning

While cognitive deficits associated with withdrawal from drugs are temporary, long-term use can also lead to lasting cognitive decline.

Read More About Addiction Here

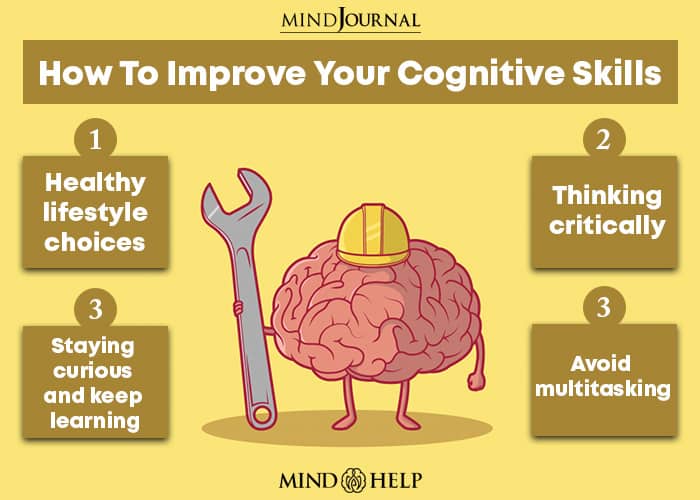

How To Improve Your Cognitive Skills

Cognitive processes are influenced by a variety of factors including genetics and experiences. It may not be possible to change your genetics, but there may be things you can do to maximize your cognitive abilities:

1. Healthy lifestyle choices

Having a healthy lifestyle that involves a healthy diet and regular exercise can help advance your cognitive functioning. A 2018 study 20 evaluated phytoestrogen, blueberry supplementation and antioxidants displayed minor increases in cognitive function after the supplementation as compared to before.

2. Thinking critically

Thinking critically involves questioning your assumptions and asking questions about your thoughts, beliefs, and how you arrive at decisions.

3. Staying curious and keep learning

Learning has no limit and hence enhancing your learning skills and staying curious can go a long way in maximizing your cognition.

4. Avoid multitasking

Multitasking may feel like you are getting things done faster in less time, research 21 indicates that it actually reduces productivity and quality of work.

Pitfalls In Cognition

It is essential to keep in mind cognition is a complicated process and is often imperfect. Some of the pitfalls that can influence an individual’s cognition include:

1. Attention problems

There are a number of things that can make it difficult for an individual to focus on everything that is present in the environment but attention is a limited resource. For instance, attentional blink tends to happen when you are extremely focused on one thing you completely miss something else that may be happening right in front of you.

2. Memory limitations

There are several memory limitations that an individual may possess. Studies 22 have shown that short-term memory is surprisingly brief and usually lasts between 20 to 30 seconds. On the other hand, a 2011 study pointed out that long term memory is more stable and enduring and can last for years and even decades. Memory can also be fragile and fallible. In some cases, a 2012 study pointed out that we tend to forget while in others we are subject to misinformation effects that may even lead to the formation of false memories.

3. Cognitive Biases

Cognitive Bias is the error in reasoning that occurs when an individual misinterprets information about the world around them which influences their decision-making abilities. One common example of this is the confirmation bias that involves the tendency to pay attention to information that confirms the individual’s beliefs while ignoring all the others associated with it. A scientific study 23 suggested that confirmation bias operates by the conscious or unconscious assimilation of evidence that is consistent with one’s assumptions and rejecting any contrary evidence associated with it.

Read More About Cognitive Biases Here

Advances In Cognition

A 2011 study 24 reported there have been several advances in cognitive neurosciences over the past two decades that are aided by technological innovations in several modalities of brain imaging as well as increased sophistication in computation and cognitive psychology. This advance has inspired psychopharmacologists and biological psychiatrists to characterize the properties of candidate cognition modifying compounds, beneficial or otherwise. The advances in cognition have allowed researchers to learn how to maximize their cognitive abilities in conducting their daily tasks.

- Morley, J. E., Morris, J. C., Berg-Weger, M., Borson, S., Carpenter, B. D., Del Campo, N., Dubois, B., Fargo, K., Fitten, L. J., Flaherty, J. H., Ganguli, M., Grossberg, G. T., Malmstrom, T. K., Petersen, R. D., Rodriguez, C., Saykin, A. J., Scheltens, P., Tangalos, E. G., Verghese, J., Wilcock, G., … Vellas, B. (2015). Brain health: the importance of recognizing cognitive impairment: an IAGG consensus conference. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 16(9), 731–739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.06.017 [↩]

- Robbins T. W. (2011). Cognition: the ultimate brain function. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 36(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2010.171 [↩]

- Murman D. L. (2015). The Impact of Age on Cognition. Seminars in hearing, 36(3), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1555115 [↩]

- Colcombe, S. J., Erickson, K. I., Raz, N., Webb, A. G., Cohen, N. J., McAuley, E., & Kramer, A. F. (2003). Aerobic fitness reduces brain tissue loss in aging humans. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences, 58(2), 176–180. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/58.2.m176 [↩]

- Erickson, K. I., Prakash, R. S., Voss, M. W., Chaddock, L., Heo, S., McLaren, M., Pence, B. D., Martin, S. A., Vieira, V. J., Woods, J. A., McAuley, E., & Kramer, A. F. (2010). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is associated with age-related decline in hippocampal volume. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 30(15), 5368–5375. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6251-09.2010 [↩]

- Flöel, A., Ruscheweyh, R., Krüger, K., Willemer, C., Winter, B., Völker, K., Lohmann, H., Zitzmann, M., Mooren, F., Breitenstein, C., & Knecht, S. (2010). Physical activity and memory functions: are neurotrophins and cerebral gray matter volume the missing link?. NeuroImage, 49(3), 2756–2763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.043 [↩]

- Lodge, J. M., & Harrison, W. J. (2019). The Role of Attention in Learning in the Digital Age. The Yale journal of biology and medicine, 92(1), 21–28. [↩]

- Clark, R., & Harrelson, G. L. (2002). Designing Instruction That Supports Cognitive Learning Processes. Journal of athletic training, 37(4 Suppl), S152–S159. [↩]

- Cowell, R. A., Barense, M. D., & Sadil, P. S. (2019). A Roadmap for Understanding Memory: Decomposing Cognitive Processes into Operations and Representations. eNeuro, 6(4), ENEURO.0122-19.2019. https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0122-19.2019 [↩]

- Ruhr-University Bochum. (2020, December 8). Visual short-term memory is more complex than previously assumed. ScienceDaily. Retrieved July 12, 2021 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/12/201208111418.htm [↩]

- Salthouse T. A. (2010). Selective review of cognitive aging. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS, 16(5), 754–760. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617710000706 [↩]

- Haaland, K. Y., Price, L., & Larue, A. (2003). What does the WMS-III tell us about memory changes with normal aging?. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS, 9(1), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355617703910101 [↩]

- Grossman E. (2014). Time after time: environmental influences on the aging brain. Environmental health perspectives, 122(9), A238–A243. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp/122-A238 [↩]

- Franklin, T. R., Wang, Z., Wang, J., Sciortino, N., Harper, D., Li, Y., Ehrman, R., Kampman, K., O’Brien, C. P., Detre, J. A., & Childress, A. R. (2007). Limbic activation to cigarette smoking cues independent of nicotine withdrawal: a perfusion fMRI study. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 32(11), 2301–2309. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1301371 [↩]

- Del Olmo, N., Higuera-Matas, A., Miguéns, M., García-Lecumberri, C., & Ambrosio, E. (2007). Cocaine self-administration improves performance in a highly demanding water maze task. Psychopharmacology, 195(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-007-0873-1 [↩]

- Kenney, J. W., & Gould, T. J. (2008). Modulation of hippocampus-dependent learning and synaptic plasticity by nicotine. Molecular neurobiology, 38(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-008-8037-9 [↩]

- Devonshire, I. M., Mayhew, J. E., & Overton, P. G. (2007). Cocaine preferentially enhances sensory processing in the upper layers of the primary sensory cortex. Neuroscience, 146(2), 841–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.070 [↩]

- Kelley, B. J., Yeager, K. R., Pepper, T. H., & Beversdorf, D. Q. (2005). Cognitive impairment in acute cocaine withdrawal. Cognitive and behavioral neurology : official journal of the Society for Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology, 18(2), 108–112. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.wnn.0000160823.61201.20 [↩]

- Gould T. J. (2010). Addiction and cognition. Addiction science & clinical practice, 5(2), 4–14. [↩]

- Barfoot, K.L., May, G., Lamport, D.J. et al. The effects of acute wild blueberry supplementation on the cognition of 7–10-year-old schoolchildren. Eur J Nutr 58, 2911–2920 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1843-6 [↩]

- May, K.E., Elder, A.D. Efficient, helpful, or distracting? A literature review of media multitasking in relation to academic performance. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 15, 13 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-018-0096-z [↩]

- Penney, D., Jeanes, R., O’Connor, J., & Alfrey, L. (2017). Re-theorising inclusion and reframing inclusive practice in physical education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(10), 1062-1077. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1414888 [↩]

- Satya-Murti, S., & Lockhart, J. (2015). Recognizing and reducing cognitive bias in clinical and forensic neurology. Neurology. Clinical practice, 5(5), 389–396. https://doi.org/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000181 [↩]

- Jacobson, S. (2019). What is machiavellianism in psychology? Harley Therapy™ Blog. https://www.harleytherapy.co.uk/counselling/machiavellianism-psychology.htm [↩]

In cognitive psychology, ‘cognition is the mental process of information processing that is the basis of knowledge.

Cognition is the result of the activity of the cognitive processes that include:

- Apperception

- Attention

- Comprehension

- Decision making

- Introspection

- Judgement

- Memory

- Learning

- Perception

- Reasoning

- Problem solving

The the activity of the cognitive processes give rise to cognitions, the product of cognition, which are the psychological, mental experiences that are the basis of our knowledge about the world and are the content of awareness and consciousness.

Cognitions include:

- Attitudes

- Beliefs

- Concepts

- Delusions

- Expectations

- False beliefs

- Hallucinations

- Imagery

- Insight

- Intentionality

- Ideas

- Irrational beliefs

- Thoughts

Various disciplines, such as psychology, philosophy, linguistics, and computer science all study cognition. However, the term’s usage varies across disciplines; for example, in psychology and cognitive science, «cognition» usually refers to an information processing view of an individual’s psychological functions. It is also used in a branch of social psychology called social cognition to explain attitudes, attribution, and groups dynamics.[1] In cognitive psychology and cognitive engineering, cognition is typically assumed to be information processing in a participant’s or operator’s mind or brain.[2]

Cognition is a faculty for the processing of information, applying knowledge, and changing preferences. Cognition, or cognitive processes, can be natural or artificial, conscious or unconscious. These processes are analyzed from different perspectives within different contexts, notably in the fields of linguistics, anesthesia, neurology and psychiatry, psychology, philosophy, anthropology, systemics, and computer science.[3]Template:Page needed Within psychology or philosophy, the concept of cognition is closely related to abstract concepts such as mind, intelligence. It encompasses the mental functions, mental processes (thoughts), and states of intelligent entities (humans, collaborative groups, human organizations, highly autonomous machines, and artificial intelligences).[2]

Etymology

The word cognition comes from the Latin verb cognosco (con ‘with’ + gnōscō ‘know’), itself a cognate of the Ancient Greek verb gnόsko «γνώσκω» meaning ‘I know’ (noun: gnόsis «γνώσις» = knowledge), so broadly, ‘to conceptualize’ or ‘to recognize’.

Origins of Cognition

Attention to the cognitive process came about more than twenty-three centuries ago, beginning with Aristotle and his interest in the inner-workings of the mind and how they affect the human experience. Aristotle focused on cognitive areas pertaining to memory, perception, and mental imagery. The Greek philosopher found great importance in ensuring that his studies were based on empirical evidence; scientific information that is gathered through thorough observation and conscientious experimentation.[4] Centuries later, as psychology became a blooming study in Europe and then gaining a following in America, other scientists like Wilhelm Wundt, Herman Ebbinghaus, Mary Whiton Calkins, and William James, to name a few, would offer their contributions to the study of cognition.

Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920) heavily emphasized the notion of what he called introspection; examining the inner feelings of an individual. With introspection, the subject had to be careful to describe their feelings in the most objective manner possible in order for Wundt to find the information scientific.[5][6] Though Wundt’s contributions are by no means minimal, modern psychologists find his methods to be quite subjective, and choose to rely on more objective procedures of experimentations to make conclusions about the human cognitive process.

Herman Ebbinghaus (1850-1909) conducted cognitive studies mainly examined the function and capacity of human memory.

Ebbinghaus developed his own experiment in which he constructed over 2,000 syllables made out of nonexistent words, for instance EAS. He would then examine his own personal ability to learn these non words. He purposely chose non words as opposed to real words to control for the influence of pre-existing experience with what the words may symbolize, thus enabling easier recollection of them.[5][7] Ebbinghaus observed and hypothesized a number of variables that may have affected his ability to learn and recall the non words he created. One of the reasons he concluded was the amount of time between the presentation of the list of stimuli. His work heavily influenced the study of serial position and its affect on memory, discussed in subsequent sections.

Mary Whiton Calkins (1863-1930) was an influential American female pioneer in the realm of psychology. Her work also focused on the human memory capacity. A common theory, called the Recency effect, can be attributed to the studies that she conducted.[8] The recency effect, also discussed in the subsequent experiment section, is the tendency for individuals to be able to accurately recollect the final items presented in a sequence of stimuli. Her theory is closely related to the aforementioned study and conclusion of the memory experiments conducted by Herman Ebbinghaus.[9]

William James (1842-1910) is another pivotal figure in the history of cognitive science. James was quite discontent with Wundt’s emphasis on introspection and Ebbinghaus’ use of nonsense stimuli. He instead chose to focus on the human learning experience in everyday life and its importance to the study of cognition. James’ major contribution was his textbook Principles of Psychology that preliminarily examines many aspects of cognition like perception, memory, reasoning, and attention to name a few.[9]

Psychology

File:Generalization process using trees PNG version.png When the mind makes a generalization such as the concept of tree, it extracts similarities from numerous examples; the simplification enables higher-level thinking.

The sort of mental processes described as cognitive are largely influenced by research which has successfully used this paradigm in the past, likely starting with Thomas Aquinas, who divided the study of behavior into two broad categories: cognitive (how we know the world), and affective (how we understand the world via feelings and emotions). Consequently, this description tends to apply to processes such as memory, association, concept formation, pattern recognition, language, attention, perception, action, problem solving and mental imagery.[10][11] Traditionally, emotion was not thought of as a cognitive process. This division is now regarded as largely artificial, and much research is currently being undertaken to examine the cognitive psychology of emotion; research also includes one’s awareness of one’s own strategies and methods of cognition called metacognition and includes metamemory.

Empirical research into cognition is usually scientific and quantitative, or involves creating models to describe or explain certain behaviors.

While few people would deny that cognitive processes are a function of the brain, a cognitive theory will not necessarily make reference to the brain or other biological process (compare neurocognitive). It may purely describe behavior in terms of information flow or function. Relatively recent fields of study such as cognitive science and neuropsychology aim to bridge this gap, using cognitive paradigms to understand how the brain implements these information-processing functions (see also cognitive neuroscience), or how pure information-processing systems (e.g., computers) can simulate cognition (see also artificial intelligence). The branch of psychology that studies brain injury to infer normal cognitive function is called cognitive neuropsychology. The links of cognition to evolutionary demands are studied through the investigation of animal cognition. And conversely, evolutionary-based perspectives can inform hypotheses about cognitive functional systems’ evolutionary psychology.

The theoretical school of thought derived from the cognitive approach is often called cognitivism.

The phenomenal success of the cognitive approach can be seen by its current dominance as the core model in contemporary psychology (usurping behaviorism in the late 1950s).

Cognition is severely damaged in dementia.

For every individual, the social context in which she’s embedded provides the symbols of her representation and linguistic expression. The human society sets the environment where the newborn will be socialized and develop his cognition. For example, face perception in human babies emerges by the age of two months: young children at a playground or swimming pool develop their social recognition by being exposed to multiple faces and associating the experiences to those faces. Education has the explicit task in society of developing cognition. Choices are made regarding the environment and permitted action that lead to a formed experience.

Language acquisition is an example of an emergent behavior. From a large systemic perspective, cognition is considered closely related to the social and human organization functioning and constrains. For example, the macro-choices made by the teachers influence the micro-choices made by students..

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development

For years, sociologists and psychologists have conducted studies on cognitive development or the construction of human thought or mental processes.

Jean Piaget was one of the most important and influential people in the field of Developmental Psychology. He believed that humans are unique in comparison to animals because we have the capacity to do «abstract symbolic reasoning.» His work can be compared to Lev Vygotsky, Sigmund Freud, and Erik Erikson who were also great contributors in the field of Developmental Psychology. Today, Piaget is known for studying the cognitive development in children. He studied his own three children and their intellectual development and came up with a theory that describes the stages children pass through during development.[12]

Piaget’s theory of developmental psychology tackled cognitive development from infancy to adulthood.

| Stage | Age or Period | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Sensorimotor stage | Infancy (0–2 years) | Intelligence is present; motor activity but no symbols; knowledge is developing yet limited; knowledge is based on experiences/ interactions; mobility allows child to learn new things; some language skills are developed at the end of this stage. The goal is to develop object permanence; achieves basic understanding of causality, time, and space. |

| Pre-operational stage | Toddler and Early Childhood (2–7 years) | Symbols or language skills are present; memory and imagination are developed; nonreversible and nonlogical thinking; shows intuitive problem solving; begins to see relationships; grasps concept of conservation of numbers; egocentric thinking predominates. |

| Concrete operational stage | Elementary and Early Adolescence (7–12 years) | Logical and systematic form of intelligence; manipulation of symbols related to concrete objects; thinking is now characterized by reversibility and the ability to take the role of another; grasps concepts of the conservation of mass, length, weight, and volume; operational thinking predominates nonreversible and egocentric thinking |

| Formal operational stage | Adolescence and Adulthood (12 years and on) | Logical use of symbols related to abstract concepts; Acquires flexibility in thinking as well as the capacities for abstract thinking and mental hypothesis testing; can consider possible alternatives in complex reasoning and problem solving. |

[13]

Common Cognitive Experiments

Serial position

The serial position experiment is meant to test a theory of memory that states that when information is given in a serial manner, we tend to remember information in the beginning of the sequence, called the primacy effect, and information in the end of the sequence, called the recency effect. Consequently, information given in the middle of the sequence is typically forgotten, or not recalled as easily. This study predicts that the recency effect is stronger than the primacy effect because the information that is most recently learned is still in working memory when asked to be recalled. On the other hand, information that is learned first still has to go through a retrieval process. This experiment focuses on human memory processes.[14]

Word superiority

The word superiority experiment presents a subject with a word or a letter by itself for a brief period of time, i.e. 40ms, and they are then asked to recall the letter that was in a particular location in the word. By theory, the subject should be able to correctly recall the letter when it was presented in a word than when it was presented in isolation. This experiment focuses on human speech and language.[15]

Brown-Peterson

In the Brown-Peterson experiment, participants are briefly presented with a trigram and in one particular version of the experiment, they are then given a distractor task asking them to identify whether a sequence of words are in fact words, or non-words (due to being misspelled, etc.). After the distractor task, they are asked to recall the trigram which they were presented with before the distractor task. In theory, the longer the distractor task, the harder it will be for participants to correctly recall the trigram. This experiment focuses on human short-term memory.[16]

Memory span

During the memory span experiment, each subject is presented with a sequence of stimuli of the same kind; words depicting objects, numbers, letters that sound similar, and letters that sound dissimilar. After being presented with the stimuli, the subject is asked to recall the sequence of stimuli that they were given in the exact order in which they were given it. In one particular version of the experiment, if the subject recalled a list correctly, the list length increased by one for that type of material, and vice versa if it was recalled incorrectly. The theory is that people have a memory span of about seven items for numbers, the same for letters that sound dissimilar and short words. The memory span is projected to be shorter with letters that sound similar and longer words.[17]

Visual search

In one version of the visual search experiment, participants are presented with a window that displayed circles and squares scattered across it. The participant is to identify whether there is a green circle on the window. In the «featured» search, the subject is presented with several trial windows that have blue squares or circles and one green circle or no green circle in it at all. In the «conjunctive» search, the subject is presented with trial windows that have blue circles or green squares and a present or absent green circle whose presence the participant is asked to identify. What is expected is that in the feature searches, reaction time, that is the time it takes for a participant to identify whether a green circle is present or not, should not change as the number of distractors increases. Conjunctive searches where the target is absent should have a longer reaction time than the conjunctive searches where the target is present. The theory is that in feature searches, it is easy to spot the target or if it is absent because of the difference in color between the target and the distractors. In conjunctive searches where the target is absent, reaction time increases because the subject has to look at each shape to determine whether it is the target or not because some of the distractors if not all of them, are the same color as the target stimuli. Conjunctive searches where the target is present take less time because if the target is found, the search between each shape, stops.[18]

Knowledge representation

The semantic network of knowledge representation systems has been studied in various paradigms. One of the oldest is the leveling and sharpening of stories as they are repeated from memory studied by Bartlett. The semantic differential used factor analysis to determine the main meanings of words, finding that value or «goodness» of words is the first factor. More controlled experiments examine the categorical relationships of words in free recall. The hierarchical structure of words has been explicitly mapped in George Miller’s Wordnet. More dynamic models of semantic networks have been created and tested with neural network experiments based on computational systems such as latent semantic analysis (LSA), Bayesian analysis, and multidimensional factor analysis. The semantics (meaning) of words is studied by all the disciplines of cognitive science.[citation needed]

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ Sternberg, R. J., & Sternberg, K. (2009). Cognitive psychology (6th Ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.