Citizenship is an allegiance of person to a state.

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and the conditions under which that status will be withdrawn. Recognition by a state as a citizen generally carries with it recognition of civil, political, and social rights which are not afforded to non-citizens.

In general, the basic rights normally regarded as arising from citizenship are the right to a passport, the right to leave and return to the country/ies of citizenship, the right to live in that country, and to work there.

Some countries permit their citizens to have multiple citizenships, while others insist on exclusive allegiance.

Determining factors[edit]

A person can be recognized or granted citizenship on a number of bases. Usually, citizenship based on circumstances of birth is automatic, but an application may be required.

- Citizenship by family (jus sanguinis). If one or both of a person’s parents are citizens of a given state, then the person may have the right to be a citizen of that state as well.[a] Formerly this might only have applied through the paternal line, but sex equality became common since the late twentieth century. Citizenship is granted based on ancestry or ethnicity and is related to the concept of a nation state common in Europe. Where jus sanguinis holds, a person born outside a country, one or both of whose parents are citizens of the country, is also a citizen. Some states (United Kingdom, Canada) limit the right to citizenship by descent to a certain number of generations born outside the state; others (Germany, Ireland, Switzerland[3]) grant citizenship only if each new generation is registered with the relevant foreign mission within a specified deadline; while others (France, Italy) have no limitation on the number of generations born abroad who can claim citizenship of their ancestors’ country. This form of citizenship is common in civil law countries.

- Citizenship by birth (jus soli). Some people are automatically citizens of the state in which they are born. This form of citizenship originated in England, where those who were born within the realm were subjects of the monarch (a concept pre-dating that of citizenship in England) and is common in common law countries. Most countries in the Americas grant unconditional jus soli citizenship, while it has been limited or abolished in almost all other countries.

- In many cases, both jus soli and jus sanguinis hold citizenship either by place or parentage (or both).

- Citizenship by marriage (jus matrimonii). Many countries fast-track naturalization based on the marriage of a person to a citizen. Countries that are destinations for such immigration often have regulations to try to detect sham marriages, where a citizen marries a non-citizen typically for payment, without them having the intention of living together.[4] Many countries (United Kingdom, Germany, United States, Canada) allow citizenship by marriage only if the foreign spouse is a permanent resident of the country in which citizenship is sought; others (Switzerland, Luxembourg) allow foreign spouses of expatriate citizens to obtain citizenship after a certain period of marriage, and sometimes also subject to language skills and proof of cultural integration (e.g. regular visits to the spouse’s country of citizenship).

- Naturalization. States normally grant citizenship to people who have entered the country legally and been granted a permit to stay, or been granted political asylum, and also lived there for a specified period. In some countries, naturalization is subject to conditions which may include passing a test demonstrating reasonable knowledge of the language or way of life of the host country, good conduct (no serious criminal record), and moral character (such as drunkenness, or gambling, or an understanding of the nature of drunkenness, or gambling) vowing allegiance to their new state or its ruler and renouncing their prior citizenship. Some states allow dual citizenship and do not require naturalized citizens to formally renounce any other citizenship.

- Citizenship by investment or Economic Citizenship. Wealthy people invest money in property or businesses, buy government bonds or simply donate cash directly, in exchange for citizenship and a passport. Whilst legitimate and usually limited in quota, the schemes are controversial. Costs for citizenship by investment range from as little as $100,000 (£74,900) to as much as €2.5m (£2.19m)[5]

- Excluded categories. In the past, there have been exclusions on entitlement to citizenship on grounds such as skin color, ethnicity, sex, and free status (not being a slave). Most of these exclusions no longer apply in most places. Modern examples include some Arab countries which rarely grant citizenship to non-Muslims, e.g. Qatar is known for granting citizenship to foreign athletes, but they all have to profess the Islamic faith in order to receive citizenship. The United States grants citizenship to those born as a result of reproductive technologies, and internationally adopted children born after February 27, 1983. Some exclusions still persist for internationally adopted children born before February 27, 1983, even though their parents meet citizenship criteria.

History[edit]

Polis[edit]

Many thinkers such as Giorgio Agamben in his work extending the biopolitical framework of Foucault’s History of Sexuality in the book, Homo Sacer,[6] point to the concept of citizenship beginning in the early city-states of ancient Greece, although others see it as primarily a modern phenomenon dating back only a few hundred years and, for humanity, that the concept of citizenship arose with the first laws. Polis meant both the political assembly of the city-state as well as the entire society.[7] Citizenship concept has generally been identified as a western phenomenon.[8] There is a general view that citizenship in ancient times was a simpler relation than modern forms of citizenship, although this view has come under scrutiny.[9] The relation of citizenship has not been a fixed or static relation but constantly changed within each society, and that according to one view, citizenship might «really have worked» only at select periods during certain times, such as when the Athenian politician Solon made reforms in the early Athenian state.[10] Citizenship was also contingent on a variety of biopolitical assemblages, such as the bioethics of emerging Theo-Philosophical traditions. It was necessary to fit Aristotle’s definition of the besouled (the animate) to obtain citizenship: neither the sacred olive tree nor spring would have any rights.

An essential part of the framework of Greco-Roman ethics is the figure of Homo Sacer or the bare life.

Historian Geoffrey Hosking in his 2005 Modern Scholar lecture course suggested that citizenship in ancient Greece arose from an appreciation for the importance of freedom.[11] Hosking explained:

It can be argued that this growth of slavery was what made Greeks particularly conscious of the value of freedom. After all, any Greek farmer might fall into debt and therefore might become a slave, at almost any time … When the Greeks fought together, they fought in order to avoid being enslaved by warfare, to avoid being defeated by those who might take them into slavery. And they also arranged their political institutions so as to remain free men.

— Geoffrey Hosking, 2005[11]

Geoffrey Hosking suggests that fear of being enslaved was a central motivating force for the development of the Greek sense of citizenship. Sculpture: a Greek woman being served by a slave-child.

Slavery permitted slave-owners to have substantial free time and enabled participation in public life.[11] Polis citizenship was marked by exclusivity. Inequality of status was widespread; citizens (πολίτης politēs < πόλις ‘city’) had a higher status than non-citizens, such as women, slaves, and resident foreigners (metics).[12][13] The first form of citizenship was based on the way people lived in the ancient Greek times, in small-scale organic communities of the polis. Citizenship was not seen as a separate activity from the private life of the individual person, in the sense that there was not a distinction between public and private life.[citation needed] The obligations of citizenship were deeply connected to one’s everyday life in the polis. These small-scale organic communities were generally seen as a new development in world history, in contrast to the established ancient civilizations of Egypt or Persia, or the hunter-gatherer bands

elsewhere. From the viewpoint of the ancient Greeks, a person’s public life was not separated from their private life, and Greeks did not distinguish between the two worlds according to the modern western conception. The obligations of citizenship were deeply connected with everyday life. To be truly human, one had to be an active citizen to the community, which Aristotle famously expressed: «To take no part in the running of the community’s affairs is to be either a beast or a god!» This form of citizenship was based on the obligations of citizens towards the community, rather than rights given to the citizens of the community. This was not a problem because they all had a strong affinity with the polis; their own destiny and the destiny of the community were strongly linked. Also, citizens of the polis saw obligations to the community as an opportunity to be virtuous, it was a source of honor and respect. In Athens, citizens were both rulers and ruled, important political and judicial offices were rotated and all citizens had the right to speak and vote in the political assembly.

Roman ideas[edit]

In the Roman Empire, citizenship expanded from small-scale communities to the entirety of the empire. Romans realized that granting citizenship to people from all over the empire legitimized Roman rule over conquered areas. Roman citizenship was no longer a status of political agency, as it had been reduced to a judicial safeguard and the expression of rule and law.[14] Rome carried forth Greek ideas of citizenship such as the principles of equality under the law, civic participation in government, and notions that «no one citizen should have too much power for too long»,[15] but Rome offered relatively generous terms to its captives, including chances for lesser forms of citizenship.[15] If Greek citizenship was an «emancipation from the world of things»,[16] the Roman sense increasingly reflected the fact that citizens could act upon material things as well as other citizens, in the sense of buying or selling property, possessions, titles, goods. One historian explained:

The person was defined and represented through his actions upon things; in the course of time, the term property came to mean, first, the defining characteristic of a human or other being; second, the relation which a person had with a thing; and third, the thing defined as the possession of some person.

Roman citizenship reflected a struggle between the upper-class patrician interests against the lower-order working groups known as the plebeian class.[15] A citizen came to be understood as a person «free to act by law, free to ask and expect the law’s protection, a citizen of such and such a legal community, of such and such a legal standing in that community».[18] Citizenship meant having rights to have possessions, immunities, expectations, which were «available in many kinds and degrees, available or unavailable to many kinds of person for many kinds of reason».[18] The law itself was a kind of bond uniting people.[19] Roman citizenship was more impersonal, universal, multiform, having different degrees and applications.[19]

Middle Ages[edit]

During the European Middle Ages, citizenship was usually associated with cities and towns (see medieval commune), and applied mainly to middle-class folk. Titles such as burgher, grand burgher (German Großbürger) and the bourgeoisie denoted political affiliation and identity in relation to a particular locality, as well as membership in a mercantile or trading class; thus, individuals of respectable means and socioeconomic status were interchangeable with citizens.

During this era, members of the nobility had a range of privileges above commoners (see aristocracy), though political upheavals and reforms, beginning most prominently with the French Revolution, abolished privileges and created an egalitarian concept of citizenship.

Renaissance[edit]

During the Renaissance, people transitioned from being subjects of a king or queen to being citizens of a city and later to a nation.[20]: p.161 Each city had its own law, courts, and independent administration.[21] And being a citizen often meant being subject to the city’s law in addition to having power in some instances to help choose officials.[21] City dwellers who had fought alongside nobles in battles to defend their cities were no longer content with having a subordinate social status but demanded a greater role in the form of citizenship.[22] Membership in guilds was an indirect form of citizenship in that it helped their members succeed financially.[23] The rise of citizenship was linked to the rise of republicanism, according to one account, since independent citizens meant that kings had less power. [24] Citizenship became an idealized, almost abstract, concept,[10] and did not signify a submissive relation with a lord or count, but rather indicated the bond between a person and the state in the rather abstract sense of having rights and duties.[10]

Modern times[edit]

The modern idea of citizenship still respects the idea of political participation, but it is usually done through «elaborate systems of political representation at a distance» such as representative democracy.[9] Modern citizenship is much more passive; action is delegated to others; citizenship is often a constraint on acting, not an impetus to act.[9] Nevertheless, citizens are usually aware of their obligations to authorities and are aware that these bonds often limit what they can do.[9]

United States[edit]

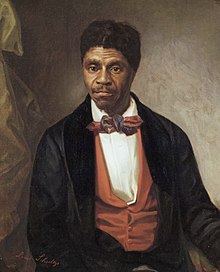

Portrait of Dred Scott, the plaintiff in the infamous Dred Scott v. Sandford case at the Supreme Court of the United States, commissioned by a «group of Negro citizens» and presented to the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, in 1888

From 1790 until the mid-twentieth century, United States law used racial criteria to establish citizenship rights and regulate who was eligible to become a naturalized citizen.[25] The Naturalization Act of 1790, the first law in U.S. history to establish rules for citizenship and naturalization, barred citizenship to all people who were not of European descent, stating that «any alien being a free white person, who shall have resided within the limits and under the jurisdiction of the United States for the term of two years, maybe admitted to becoming a citizen thereof.»[26]

Under early U.S. laws, African Americans were not eligible for citizenship. In 1857, these laws were upheld in the US Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sandford, which ruled that «a free negro of the African race, whose ancestors were brought to this country and sold as slaves, is not a ‘citizen’ within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States,» and that «the special rights and immunities guaranteed to citizens do not apply to them.»[27]

It was not until the abolition of slavery following the American Civil War that African Americans were granted citizenship rights. The 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified on July 9, 1868, stated that «all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.»[28] Two years later, the Naturalization Act of 1870 would extend the right to become a naturalized citizen to include «aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent».[29]

Despite the gains made by African Americans after the Civil War, Native Americans, Asians, and others not considered «free white persons» were still denied the ability to become citizens. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act explicitly denied naturalization rights to all people of Chinese origin, while subsequent acts passed by the US Congress, such as laws in 1906, 1917, and 1924, would include clauses that denied immigration and naturalization rights to people based on broadly defined racial categories.[30] Supreme Court cases such as Ozawa v. the United States (1922) and U.S. v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923), would later clarify the meaning of the phrase «free white persons,» ruling that ethnically Japanese, Indian, and other non-European people were not «white persons», and were therefore ineligible for naturalization under U.S. law.

Native Americans were not granted full US citizenship until the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924. However, even well into the 1960s, some state laws prevented Native Americans from exercising their full rights as citizens, such as the right to vote. In 1962, New Mexico became the last state to enfranchise Native Americans.[31]

It was not until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 that the racial and gender restrictions for naturalization were explicitly abolished. However, the act still contained restrictions regarding who was eligible for US citizenship and retained a national quota system which limited the number of visas given to immigrants based on their national origin, to be fixed «at a rate of one-sixth of one percent of each nationality’s population in the United States in 1920».[32] It was not until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that these immigration quota systems were drastically altered in favor of a less discriminatory system.

[edit]

The 1918 constitution of revolutionary Russia granted citizenship to any foreigners who were living within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, so long as they were «engaged in work and [belonged] to the working class.»[33] It recognized «the equal rights of all citizens, irrespective of their racial or national connections» and declared oppression of any minority group or race «to be contrary to the fundamental laws of the Republic.» The 1918 constitution also established the right to vote and be elected to soviets for both men and women «irrespective of religion, nationality, domicile, etc. […] who shall have completed their eighteenth year by the day of the election.»[34] The later constitutions of the USSR would grant universal Soviet citizenship to the citizens of all member republics[35][36] in concord with the principles of non-discrimination laid out in the original 1918 constitution of Russia.

Nazi Germany[edit]

Nazism, the German variant of twentieth-century fascism, classified inhabitants of the country into three main hierarchical categories, each of which would have different rights in relation to the state: citizens, subjects, and aliens. The first category, citizens, were to possess full civic rights and responsibilities. Citizenship was conferred only on males of German (or so-called «Aryan») heritage who had completed military service, and could be revoked at any time by the state. The Reich Citizenship Law of 1935 established racial criteria for citizenship in the German Reich, and because of this law Jews and others who could not «prove German racial heritage» were stripped of their citizenship.[37]

The second category, subjects, referred to all others who were born within the nation’s boundaries who did not fit the racial criteria for citizenship. Subjects would have no voting rights, could not hold any position within the state, and possessed none of the other rights and civic responsibilities conferred on citizens. All women were to be conferred «subject» status upon birth, and could only obtain «citizen» status if they worked independently or if they married a German citizen (see women in Nazi Germany).

The final category, aliens, referred to those who were citizens of another state, who also had no rights.

In 2021, the German government passed Article 116 (2) of the Basic Law, which entitles the restoration of citizenship to individuals who had their German citizenship revoked «on political, racial, or religious grounds» between 30 January 1933 and 8 May 1945. This also entitles their descendants to German citizenship.[38]

Israel[edit]

The primary principles of Israeli citizenship is jus sanguinis (citizenship by descent) for Jews and jus soli (citizenship by place of birth) for others.[39]

Different senses[edit]

Many theorists suggest that there are two opposing conceptions of citizenship: an economic one, and a political one. For further information, see History of citizenship. Citizenship status, under social contract theory, carries with it both rights and duties. In this sense, citizenship was described as «a bundle of rights — primarily, political participation in the life of the community, the right to vote, and the right to receive certain protection from the community, as well as obligations.»[40] Citizenship is seen by most scholars as culture-specific, in the sense that the meaning of the term varies considerably from culture to culture, and over time.[9] In China, for example, there is a cultural politics of citizenship which could be called «peopleship», argued by an academic article.[41]

How citizenship is understood depends on the person making the determination. The relation of citizenship has never been fixed or static, but constantly changes within each society. While citizenship has varied considerably throughout history, and within societies over time, there are some common elements but they vary considerably as well. As a bond, citizenship extends beyond basic kinship ties to unite people of different genetic backgrounds. It usually signifies membership in a political body. It is often based on or was a result of, some form of military service or expectation of future service. It usually involves some form of political participation, but this can vary from token acts to active service in government.

Citizenship is a status in society. It is an ideal state as well. It generally describes a person with legal rights within a given political order. It almost always has an element of exclusion, meaning that some people are not citizens and that this distinction can sometimes be very important, or not important, depending on a particular society. Citizenship as a concept is generally hard to isolate intellectually and compare with related political notions since it relates to many other aspects of society such as the family, military service, the individual, freedom, religion, ideas of right, and wrong, ethnicity, and patterns for how a person should behave in society.[20] When there are many different groups within a nation, citizenship may be the only real bond that unites everybody as equals without discrimination—it is a «broad bond» linking «a person with the state» and gives people a universal identity as a legal member of a specific nation.[42]

Modern citizenship has often been looked at as two competing underlying ideas:[43]

- The liberal-individualist or sometimes liberal conception of citizenship suggests that citizens should have entitlements necessary for human dignity.[44] It assumes people act for the purpose of enlightened self-interest. According to this viewpoint, citizens are sovereign, morally autonomous beings with duties to pay taxes, obey the law, engage in business transactions, and defend the nation if it comes under attack,[44] but are essentially passive politically,[43] and their primary focus is on economic betterment. This idea began to appear around the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and became stronger over time, according to one view.[10] According to this formulation, the state exists for the benefit of citizens and has an obligation to respect and protect the rights of citizens, including civil rights and political rights.[10] It was later that so-called social rights became part of the obligation for the state.[10]

- The civic-republican or sometimes classical or civic humanist conception of citizenship emphasizes man’s political nature and sees citizenship as an active process, not a passive state or legal marker.[43] It is relatively more concerned that government will interfere with popular places to practice citizenship in the public sphere. Citizenship means being active in government affairs.[44] According to one view, most people today live as citizens according to the liberal-individualist conception but wished they lived more according to the civic-republican ideal.[43] An ideal citizen is one who exhibits «good civic behavior».[10] Free citizens and a republic government are «mutually interrelated.»[10] Citizenship suggested a commitment to «duty and civic virtue».[10]

Scholars suggest that the concept of citizenship contains many unresolved issues, sometimes called tensions, existing within the relation, that continue to reflect uncertainty about what citizenship is supposed to mean.[10] Some unresolved issues regarding citizenship include questions about what is the proper balance between duties and rights.[10] Another is a question about what is the proper balance between political citizenship versus social citizenship.[10] Some thinkers see benefits with people being absent from public affairs, since too much participation such as revolution can be destructive, yet too little participation such as total apathy can be problematic as well.[10] Citizenship can be seen as a special elite status, and it can also be seen as a democratizing force and something that everybody has; the concept can include both senses.[10] According to sociologist Arthur Stinchcombe, citizenship is based on the extent that a person can control one’s own destiny within the group in the sense of being able to influence the government of the group.[20]: p.150 One last distinction within citizenship is the so-called consent descent distinction, and this issue addresses whether citizenship is a fundamental matter determined by a person choosing to belong to a particular nation––by their consent––or is citizenship a matter of where a person was born––that is, by their descent.[12]

International[edit]

Some intergovernmental organizations have extended the concept and terminology associated with citizenship to the international level,[45] where it is applied to the totality of the citizens of their constituent countries combined. Citizenship at this level is a secondary concept, with rights deriving from national citizenship.

European Union[edit]

The Maastricht Treaty introduced the concept of citizenship of the European Union. Article 17 (1) of the Treaty on European Union[46] stated that:

Citizenship of the Union is hereby established. Every person holding the nationality of a Member State shall be a citizen of the Union. Citizenship of the Union shall be additional to and not replace national citizenship.[47]

An agreement is known as the amended EC Treaty[47] established certain minimal rights for European Union citizens. Article 12 of the amended EC Treaty guaranteed a general right of non-discrimination within the scope of the Treaty. Article 18 provided a limited right to free movement and residence in the Member States other than that of which the European Union citizen is a national. Articles 18-21 and 225 provide certain political rights.

Union citizens have also extensive rights to move in order to exercise economic activity in any of the Member States[48] which predate the introduction of Union citizenship.[49]

Mercosur[edit]

Citizenship of the Mercosur is granted to eligible citizens of the Southern Common Market member states. It was approved in 2010 through the Citizenship Statute and should be fully implemented by the member countries in 2021 when the program will be transformed in an international treaty incorporated into the national legal system of the countries, under the concept of «Mercosur Citizen».[citation needed]

Commonwealth[edit]

Citizenship ceremony on beach near Cooktown, Queensland. 2012

The concept of «Commonwealth Citizenship» has been in place ever since the establishment of the Commonwealth of Nations. As with the EU, one holds Commonwealth citizenship only by being a citizen of a Commonwealth member state. This form of citizenship offers certain privileges within some Commonwealth countries:

- Some such countries do not require tourist visas of citizens of other Commonwealth countries or allow some Commonwealth citizens to stay in the country for tourism purposes without a visa for longer than citizens of other countries.

- In some Commonwealth countries, resident citizens of other Commonwealth countries are entitled to political rights, e.g., the right to vote in local and national elections and in some cases even the right to stand for election.

- In some instances the right to work in any position (including the civil service) is granted, except for certain specific positions, such as in the defense departments, Governor-General or President or Prime Minister.

- In the United Kingdom, all Commonwealth citizens legally residing in the country can vote and stand for office at all elections.

Although Ireland was excluded from the Commonwealth in 1949 because it declared itself a republic, Ireland is generally treated as if it were still a member. Legislation often specifically provides for equal treatment between Commonwealth countries and Ireland and refers to «Commonwealth countries and Ireland».[50] Ireland’s citizens are not classified as foreign nationals in the United Kingdom.

Canada departed from the principle of nationality being defined in terms of allegiance in 1921. In 1935 the Irish Free State was the first to introduce its own citizenship. However, Irish citizens were still treated as subjects of the Crown, and they are still not regarded as foreign, even though Ireland is not a member of the Commonwealth.[51] The Canadian Citizenship Act of 1946 provided for a distinct Canadian Citizenship, automatically conferred upon most individuals born in Canada, with some exceptions, and defined the conditions under which one could become a naturalized citizen. The concept of Commonwealth citizenship was introduced in 1948 in the British Nationality Act 1948. Other dominions adopted this principle such as New Zealand, by way of the British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948.

Subnational[edit]

Citizenship most usually relates to membership of the nation-state, but the term can also apply at the subnational level. Subnational entities may impose requirements, of residency or otherwise, which permit citizens to participate in the political life of that entity or to enjoy benefits provided by the government of that entity. But in such cases, those eligible are also sometimes seen as «citizens» of the relevant state, province, or region. An example of this is how the fundamental basis of Swiss citizenship is a citizenship of an individual commune, from which follows citizenship of a canton and of the Confederation. Another example is Åland where the residents enjoy special provincial citizenship within Finland, hembygdsrätt.

The United States has a federal system in which a person is a citizen of their specific state of residence, such as New York or California, as well as a citizen of the United States. State constitutions may grant certain rights above and beyond what is granted under the United States Constitution and may impose their own obligations including the sovereign right of taxation and military service; each state maintains at least one military force subject to national militia transfer service, the state’s national guard, and some states maintain a second military force not subject to nationalization.

Diagram of relationship between; Citizens, Politicians + Laws

Education[edit]

«Active citizenship» is the philosophy that citizens should work towards the betterment of their community through economic participation, public, volunteer work, and other such efforts to improve life for all citizens. In this vein, citizenship education is taught in schools, as an academic subject in some countries. By the time children reach secondary education there is an emphasis on such unconventional subjects to be included in an academic curriculum. While the diagram on citizenship to the right is rather facile and depthless, it is simplified to explain the general model of citizenship that is taught to many secondary school pupils. The idea behind this model within education is to instill in young pupils that their actions (i.e. their vote) affect collective citizenship and thus in turn them.

Republic of Ireland[edit]

It is taught in the Republic of Ireland as an exam subject for the Junior Certificate. It is known as Civic, Social and Political Education (CSPE). A new Leaving Certificate exam subject with the working title ‘Politics & Society’ is being developed by the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) and is expected to be introduced to the curriculum sometime after 2012.[52]

United Kingdom[edit]

Citizenship is offered as a General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) course in many schools in the United Kingdom. As well as teaching knowledge about democracy, parliament, government, the justice system, human rights and the UK’s relations with the wider world, students participate in active citizenship, often involving a social action or social enterprise in their local community.

- Citizenship is a compulsory subject of the National Curriculum in state schools in England for all pupils aged 11–16. Some schools offer a qualification in this subject at GCSE and A level. All state schools have a statutory requirement to teach the subject, assess pupil attainment and report student’s progress in citizenship to parents.[53]

- In Wales the model used is personal and social education.[54][55]

- Citizenship is not taught as a discrete subject in Scottish schools, but is a cross-curricular strand of the Curriculum for Excellence. However they do teach a subject called «Modern Studies» which covers the social, political and economic study of local, national and international issues.[56]

- Citizenship is taught as a standalone subject in all state schools in Northern Ireland and most other schools in some forms from year 8 to 10 prior to GCSEs. Components of Citizenship are then also incorporated into GCSE courses such as ‘Learning for Life and Work’.

Criticism[edit]

The concept of citizenship is criticized by open borders advocates, who argue that it functions as a caste, feudal, or apartheid system in which people are assigned dramatically different opportunities based on the accident of birth. It is also criticized by some libertarians, especially anarcho-capitalists. In 1987, moral philosopher Joseph Carens argued that «citizenship in Western liberal democracies is the modern equivalent of feudal privilege—an inherited status that greatly enhances one’s life chances. Like feudal birthright privileges, restrictive citizenship is hard to justify when one thinks about it closely».[57][58][59]

See also[edit]

- Citizenship Studies

- Credit Score

- Honorary citizenship

- Nationalism

- Non-citizens (Latvia)

- Peoples

- Spatial citizenship

- Transnational citizenship

Notes[edit]

- ^ Examples: Philippines,[1] United States.[2]

References[edit]

- ^ Article IV of the Philippine Constitution.

- ^ «8 U.S. Code Part I — Nationality at Birth and Collective Naturalization». LII / Legal Information Institute.

- ^ «Federal Act on Swiss Citizenship (art 7.1)». admin.ch. Archived from the original on 2021-12-27. Retrieved 2021-02-15.

- ^ «Bishops act to tackle sham marriages». GOV.UK.

- ^ «Citizenship for sale: how tycoons can go shopping for a new passport». The Guardian. 2 June 2018. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ Agamben, G.; Heller-Roazen, D. (1998). Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Meridian: Crossing Aesthetics. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3218-5. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ Pocock 1998, p. 32.

- ^ Zarrow 1997, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Isin, Engin F.; Turner, Bryan S., eds. (2002). Handbook of Citizenship Studies. Chapter 5 — David Burchell — Ancient Citizenship and its Inheritors; Chapter 6 — Rogers M. Smith — Modern Citizenship. London: Sage. pp. 89–104, 105. ISBN 978-0-7619-6858-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Heater 2004, p. [page needed]

- ^ a b c Hosking, Geoffrey (2005). Epochs of European Civilization: Antiquity to Renaissance. Lecture 3: Ancient Greece. United Kingdom: The Modern Scholar via Recorded Booksu. pp. 1, 2 (tracks). ISBN 978-1-4025-8360-5.

- ^ a b Hebert, Yvonne M., ed. (2002). Citizenship in transformation in Canada. chapters by Veronica Strong-Boag, Yvonne Hebert, Lori Wilkinson. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 3, 4, 5. ISBN 978-0-8020-0850-3.

- ^ Pocock 1998, p. 33.

- ^ See Civis Romanus sum.

- ^ a b c Hosking, Geoffrey (2005). Epochs of European Civilization: Antiquity to Renaissance. Lecture 5: Rome as a city-state. United Kingdom: The Modern Scholar via Recorded Books. pp. tracks 1 through 9. ISBN 978-1-4025-8360-5.

- ^ Pocock 1998, p. 35.

- ^ Pocock 1998, p. 36.

- ^ a b Pocock 1998, p. 37.

- ^ a b Pocock 1998, p. 38.

- ^ a b c Taylor, David (1994). Turner, Bryan; Hamilton, Peter (eds.). Citizenship: Critical Concepts. United States and Canada: Routledge. pp. 476 pages total. ISBN 978-0-415-07036-2.

- ^ a b Weber 1998, p. 44.

- ^ Weber 1998, p. 46.

- ^ Weber 1998, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Zarrow 1997, p. 3.

- ^ «A History of U.S. Citizenship». The Los Angeles Times. July 4, 1997. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ «A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 — 1875». The Library of Congress. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ «Scott v. Sandford». Legal Information Institute. Cornell University Law School. 1857. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ «Constitution of the United States: Amendment XIV». The Charters of Freedom. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. 1868. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ «Naturalization Act of 1870». Wikisource. U.S. Congress.

- ^ «1917 Immigration Act». US Immigration Legislation Online. University of Washington-Bothell Library.

- ^ «Elections: Native Americans». Library of Congress.

- ^ «The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (The McCarran-Walter Act)». The Office of the Historian. U.S. Department of State.

- ^ «Article 2 (R.S.F.S.R. Constitution)». www.marxists.org. Retrieved Mar 5, 2023.

- ^ «Article 4 (R.S.F.S.R. Constitution)». www.marxists.org. Retrieved Mar 5, 2023.

- ^ «1936 Constitution of the USSR, Part I». www.departments.bucknell.edu. Retrieved Mar 5, 2023.

- ^ «1936 Constitution of the USSR, Part I». www.departments.bucknell.edu. Retrieved Mar 5, 2023.

- ^ «The Nuremberg Laws: The Reich Citizenship Law (September 15, 1935)». Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ Amt, Auswärtiges. «Restoration of German citizenship (Article 116 II Basic Law)». uk.diplo.de. Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- ^ Safran, William (1997-07-01). «Citizenship and Nationality in Democratic Systems: Approaches to Defining and Acquiring Membership in the Political Community». International Political Science Review. SAGE Publishing. 18 (3): 313–335. doi:10.1177/019251297018003006. S2CID 145476893.

- ^ Leary, Virginia (2000). «Citizenship. Human rights, and Diversity». In Cairns, Alan C.; Courtney, John C.; MacKinnon, Peter; Michelmann, Hans J.; Smith, David E. (eds.). Citizenship, Diversity, and Pluralism: Canadian and Comparative Perspectives. McGill-Queen’s Press — MQUP. pp. 247–264. ISBN 978-0-7735-1893-3.

The concept of ‘citizenship’ has long acquired the connotation of a bundle of rights…

- ^ Xiao, Y (2013). «China’s peopleship education: Conceptual issues and policy analysis». Citizenship Teaching and Learning. 8 (1): 21–39. doi:10.1386/ctl.8.1.21_1.

- ^ Gross, Feliks (1999). Citizenship, and ethnicity: the growth and development of a democratic multiethnic institution. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. xi, xii, xiii, 4. ISBN 978-0-313-30932-8.

- ^ a b c d Beiner, Ronald, ed. (1995). Theorizing Citizenship. J. G. A. Pocock, Michael Ignatieff. USA: State University of New York, Albany. pp. 29, 54. ISBN 978-0-7914-2335-6.

- ^ a b c Oldfield, Adrian (1994). Turner, Bryan; Hamilton, Peter (eds.). Citizenship: Critical Concepts. United States and Canada: Routledge. pp. 476 pages total, source: The Political Quarterly, 1990 vol.61, pp. 177–187, in the book, pages 188+. ISBN 9780415102452.

- ^ Daniele Archibugi, «The Global Commonwealth of Citizens. Toward Cosmopolitan Democracy», Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2008

- ^ Note: the consolidated version.

- ^ a b «Consolidated versions of the Treaty on European Union». eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved Mar 5, 2023.

- ^ Note: Articles 39, 43, 49 EC.

- ^ Violaine Hacker, «Citoyenneté culturelle et politique européenne des médias : entre compétitivité et promotion des valeurs», NATIONS, CULTURES ET ENTREPRISES EN EUROPE, sous la direction de Gilles Rouet, Collection Local et Global, L’Harmattan, Paris, pp. 163-184

- ^ «The Commonwealth Countries and Ireland (Immunities and Privileges) (Amendment) Order 2005» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-12-18.

- ^ Murray v Parkes [1942] All ER 123.

- ^ «Leaving Certificate Politics and Society : Report on the consultation process» (PDF). March 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-28. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

- ^ «National curriculum». British Government, Department for Children, Schools and Families. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ^ «NAFWC 13/2003 Personal and Social Education (PSE) and Work-Related Education (WRE) in the Basic Curriculum. Education (WRE) in the Basic Curriculum». Welsh Assembly Government. 15 June 2003. Archived from the original on 23 November 2011. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ «Personal and Social Education Framework: Key Stages 1 to 4 in Wales». Welsh Assembly Government. Archived from the original on 2011-05-04. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ «Modern Studies Association». Archived from the original on 2007-09-11. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ Ochoa Espejo, Paulina (2018). «Why borders do matter morally: The role of place in immigrants’ rights». Constellations. 25 (1): 71–86. doi:10.1111/1467-8675.12340.

- ^ Vladimirovich Kochenov, Dimitry (2020). «Ending the passport apartheid. The alternative to citizenship is no citizenship—A reply». International Journal of Constitutional Law. 18 (4): 1525–1530. doi:10.1093/icon/moaa108.

- ^ Sacco, Steven (2022). «Abolishing Citizenship: Resolving the Irreconcilability Between «Soil» and «Blood» Political Membership and Anti-Racist Democracy». Georgetown Immigration Law Journal. 36 (2).

Further reading[edit]

- Weber, Max (1998). Citizenship in Ancient and Medieval Cities. Chapter 3. Minneapolis, MN: The University of Minnesota. pp. 43–49. ISBN 978-0-8166-2880-3.

- Zarrow, Peter (1997), Fogel, Joshua A.; Zarrow, Peter G. (eds.), Imagining the People: Chinese Intellectuals and the Concept of Citizenship, 1890-1920, Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, p. 3, ISBN 978-0-7656-0098-1

- Pocock, J. G. A. (1998). Shafir, Gershon (ed.). The Citizenship Debates. Chapter 2 — The Ideal of Citizenship since Classical Times (originally published in Queen’s Quarterly 99, no. 1). Minneapolis, MN: The University of Minnesota. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-8166-2880-3.

- Archibugi, Daniele (2008). The Global Commonwealth of Citizens. Toward Cosmopolitan Democracy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2976-7.

- Brooks, Thom (2016). Becoming British: UK Citizenship Examined. Biteback.

- Beaven, Brad, and John Griffiths. «Creating the Exemplary Citizen: The Changing Notion of Citizenship in Britain 1870–1939,» Contemporary British History (2008) 22#2 pp 203–225 doi:10.1080/13619460701189559

- Carens, Joseph (2000). Culture, Citizenship, and Community: A Contextual Exploration of Justice as Evenhandedness. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829768-0.

- Heater, Derek (2004). A Brief History of Citizenship. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-3672-2.

- Kymlicka, Will (1995). Multicultural Citizenship: A Liberal Theory of Minority Rights. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829091-9.

- Maas, Willem (2007). Creating European Citizens. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5486-3.

- Marshall, T.H. (1950). Citizenship and Social Class and Other Essays. Cambridge University Press.

- Shue, Henry (1950). Basic Rights.

- Smith, Rogers (2003). Stories of Peoplehood: The Politics and Morals of Political Membership. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52003-4.

- Somers, Margaret (2008). Genealogies of Citizenship: Markets, Statelessness, and the Right to Have Rights. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79394-0.

- Soysal, Yasemin (1994). Limits of Citizenship. Migrants and Postnational Membership in Europe. University of Chicago Press.

- Turner, Bryan S. (1994). Citizenship and Social Theory. Sage. ISBN 978-0-8039-8611-4.

- Young, Iris Marion (January 1989). «Polity and group difference: A critique of the ideal of universal citizenship». Ethics. 99 (2): 250–274. doi:10.1086/293065. JSTOR 2381434. S2CID 54215809.

External links[edit]

The word citizenship, currently, carries several essential rights to human life. As some examples of these rights, we can cite: freedom of thought and expression, access to education and health care, and laws that regulate working hours.

The citizen, therefore, is a fundamental part of a society. It is for him and through him that the community grows and develops.

All goods offered to citizens depend on their approval for consumption and, consequently, socioeconomic development.

Throughout human history, the term citizenship has taken on different meanings. Let’s find out a little more about this word…

citizenship in history

The term citizen transports us to Ancient Greece. The right to citizenship in the Greek polis (city-state) meant discussing and making decisions about the direction of the economy, administration and military affairs of the state.

In this way, through the direct participation of individuals, the destiny of the State was traced. This direct participation worked as follows: before being implemented, decisions needed to be accepted by all citizens.

Matters of state administration that needed a solution were exposed to the group. The problem was discussed in public and all citizens could express their opinions. Alternatives to resolve the government’s concerns were sought and then voted on.

In this period of history, citizenship it means the individual’s right to express his opinions on the decisions of the State and to vote as he wishes. These attitudes qualify the people who practice them, who are the citizens.

However, we need to take some precautions! First, let’s clarify: not everyone was a citizen. In ancient Greece, only free men, not slaves, born in Polis and living there, had the right to citizenship.

For example, in Athens most of the population – women, children, foreigners and slaves — had no right to participate in the decisions of the State, because these people were not considered citizens.

Advancing through the seas of history, in the 17th and 18th centuries, in the liberal State, in which the creation of a Constitution and the division of powers in Executive, Legislative and Judiciary, the meaning of the word citizenship is a little changed. Every individual who owns property and a pre-established income has the right to choose, by direct vote, his representatives.

Through a political pact, the ruled choose the rulers by direct vote. Once chosen, they alone have the task of creating and applying the decisions of the State administration.

The Brazilian Constitution ensures, by direct and secret vote, that all citizens, from the age of sixteen (optional vote) and over of eighteen years (mandatory vote), have the right to choose the representatives who, for a certain period, will occupy the posts of the government.

In exchange for authorization to administer, the rulers undertake to ensure freedom of choice and thought, the preservation of life and the preservation of the private property of the ruled. This set of obligations corresponds to the natural rights of man.

If we look at the political and administrative organization of the current state, we will notice some elements inherited from the 18th century. The Constitution continues to represent a political agreement between rulers, chosen by direct vote, and the ruled.

Everyone is equal before the law, having the same rights, such as housing, respect for life and freedom.

According to the 1988 Constitution, in Brazil, individuals, under the law, are equal and have the same rights and duties, regardless of race, origin, sex, age, religion, etc. The State is obliged to preserve the natural rights of man, that is, liberty, life and property. Although this equality between everyone does not always work in daily life, prejudice and racism are the materialization of these unequal practices.

The government, through the use of laws and, if necessary, physical force (police and armed forces), ensures the balanced coexistence of society. It is through legal codes and the Judiciary that human impulse and behavior are controlled.

Currently, the meaning of the word citizenship receives a different value. All individuals are considered citizens and have the same rights and duties.

It is also essential to remember that, if in Athens and in the 18th century citizenship meant only the freedom of choice for the representatives of the people through the right to vote, in our time, some things have changed…

And today, how to define citizenship?

Today, it is considered citizen every individual, man, woman and child, born or naturalized within the national territory. Individuals who are absent from their country of origin are guaranteed rights that allow them to exercise citizenship.

This means that all people, regardless of their nationality and where they are on the planet, are considered citizens. These rights are guaranteed by international conventions, representatives of International Law.

These conventions are agreements between the participating countries that must establish, in the text of their Constitutions, a set of common norms and values that recognize foreigners as citizens who have rights and duties.

National States currently have the obligation to ensure and guarantee rights (civil, social and political) to all people, whether naturalized or not in the country in which they are located.

Thus, the citizenship is closely related to human rights. These rights correspond to the set of rules that seek to preserve the dignity and integrity of all individuals.

Citizenship corresponds, in addition to the right to life, property and liberty, to other benefits guaranteed by the State to all people who live in it. These changes resulted from a long course of conflicts between governors, representatives of the richer layers of society, and individuals who did not have the right to vote or bread and job.

This means that medical and social assistance, access to education and housing, the laws that regulate the daily work period and the minimum wage, the freedoms of expression and thought, the direct and secret vote and the equality of all before the law constitute, nowadays, the natural rights of man, or better, of the citizen of the State liberal.

Citizenship is also defined as equal access to essential services such as education. Therefore, it is the function and obligation of the public administration (municipal, state and federal governments) to promote and ensure balanced and guaranteed distribution of this right, enabling, as a consequence, the formation of a conscious and active citizen, capable of promoting transformations and improvements in the society in which lives.

Check out, below, some results obtained by the Brazilian State from the investment made to guarantee all citizens the right of access to education.

Per: Wilson Teixeira Moutinho

See too:

- The Constitution and its meanings

- Rights and Duties of the Brazilian Citizen

- The fundamental principles and the principle of dignity

citizenship is the exercise of civil, political and social rights and duties established in the Constitution of a country, by its respective citizens (individuals that make up a given nation).

Citizenship can also be defined as the condition of the citizen, an individual who lives in accordance with a set of statutes belonging to a politically and socially articulated community.

Good citizenship implies that rights and duties are intertwined, and respect and fulfillment of both contribute to a more balanced and just society.

How important is citizenship?

Theoretically, the application of the concept of citizenship is essential for there to be a better social organization. Exercising citizenship is being aware of your rights and obligations, ensuring that these are put into practice.

Exercising citizenship is being in full enjoyment of constitutional provisions. Preparing citizens for the exercise of citizenship is one of the goals of education in a country.

Rights and duties

Citizenship is constituted by the combination of a series of rights and duties, which vary according to each nation or social group. However, from the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, some topics came to be considered universal for almost all human beings.

Among some of the main duties and rights of citizens are:

Citizen duties

- Vote to choose the rulers;

- Comply with the laws;

- Educate and protect others;

- Protect nature;

- Protect the country’s public and social assets.

citizen rights

- Right to health, education, housing, work, social security, leisure, among others;

- The citizen is free to write and say what he thinks, but he needs to sign what he said and wrote;

- All are respected in their faith, thought and action in society;

- Citizens are free to practice any work, craft or profession, but the law can ask for studies and a diploma for this;

- Only the author of a work has the right to use, publish and copy it, and that right passes to his heirs;

- A person’s property, when he dies, passes to his heirs;

- In times of peace, anyone can go from one city to another, stay in or leave the country, obeying the law made for that.

Read more about what it’s like to be a Citizen.

Examples of citizenship

To practice citizenship is to enjoy the rights and duties that, theoretically, all citizens have. Let’s look at some examples:

vote for president

The possibility of choosing the President of the Republic is part of political rights. In Brazil, for example, voting is mandatory: it is not just a right, but a duty of the citizen.

Apply for a political office

In addition to voting, all citizens have the right to join a political party and run for legislative or executive positions. The possibility of being voted on is another very important political right.

move freely around the country

Freedom of movement across the national territory is a fundamental civil right. The right to come and go concerns the individual possibility to leave, enter or remain in the territory.

Enroll your children in a public school

The right to quality public education is one of the most important aspects of the so-called social rights, which aim to build a more equal society. According to the Federal Constitution of 1988, the State is responsible for guaranteeing this right to all Brazilian citizens.

Being treated in a public hospital

In Brazil, there is the SUS (Unified Health System), which guarantees free medical care for everyone. The right to health was an achievement of Brazilian society. It is provided for in the Federal Constitution of 1988, which guarantees that health is a citizen’s right and a duty of the State.

Declare and pay income tax

One of the most important duties of the citizen for the maintenance of the State is to pay taxes, and the most important of them is the one that is levied on your income (what you earn). Every year, citizens must declare to the Internal Revenue Service their annual earnings, on which the tax will be collected.

watch over the public space

Another example of citizenship is the zeal that each person must have with common use spaces, such as squares, streets and other places of public access.

See also Ethics and Citizenship and Ways to exercise citizenship.

Origin of citizenship

The concept of citizenship would have emerged during the Ancient Greece, but in a less egalitarian way as it is practiced today.

At that time, only free men who were born and lived in cities were considered citizens. Foreigners and women, for example, did not have the rights and duties that the «democratic» political regime granted.

In fact, etymologically the word citizenship originated from the Latin civitas, which literally means «city», as it was directly related to people in urban centers. Currently, however, the concept of citizen goes beyond the limits of metropolises.

From the 18th century, with influence of Enlightenment ideals It’s from economic and political liberalism, the way in which citizenship starts to be interpreted begins to resemble the contemporary model.

Dual citizenship

Citizenship is also interpreted as a person’s status as a member of a nation-state. In other words, it would be the definition of the place where the citizen exercises his rights and duties.

To have Brazilian citizenship, a person must have been born in Brazilian territory or apply for naturalization, in the case of foreigners. However, citizens of other countries who wish to acquire Brazilian citizenship must comply with all the steps required for this process.

Thus, Brazilian citizenship, for example, is related to the individual who is linked to the rights and duties that are defined in the Constitution of Brazil. However, someone born in Brazil can acquire citizenships of other countries (dual citizenship), as long as they follow a set of conditions imposed by the respective nations.

See also the meaning of Nationality.

Citizenship in Brazil

The Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil, promulgated on October 5, 1988, by the National Constituent Assembly, composed of 559 congressmen (deputies and senators), it consolidated democracy, after long years of military dictatorship in the Brazil.

In other words, full democracy is relatively recent in Brazil, as well as citizenship, compared to other countries.

Find out more about the meaning of Democracy and meet important moments for citizenship in Brazil.

-

1

citizenship

citizenship [ˊsɪtɪzǝnʃɪp]

n

гражда́нство

Англо-русский словарь Мюллера > citizenship

-

2

citizenship

Персональный Сократ > citizenship

-

3

citizenship

Politics english-russian dictionary > citizenship

-

4

citizenship

n

2) гражданственность; права и обязанности граждан

•

English-russian dctionary of diplomacy > citizenship

-

5

citizenship

Большой англо-русский и русско-английский словарь > citizenship

-

6

citizenship

Англо-русский юридический словарь > citizenship

-

7

citizenship

1. n гражданство

2. n гражданственность; права и обязанности гражданина

English-Russian base dictionary > citizenship

-

8

citizenship

[‘sɪtɪz(ə)nʃɪp]

сущ.

to acquire / receive citizenship — получить гражданство

to give up / renounce one’s citizenship — отказываться от гражданства какой-л. страны

to revoke smb.’s citizenship — лишать кого-л. гражданства

Syn:

Англо-русский современный словарь > citizenship

-

9

citizenship

[ʹsıtız(ə)nʃıp]

1. гражданство

to be admitted to citizenship — получить права гражданства; быть принятым в гражданство ()

citizenship papers — документ о натурализации /о принятии в гражданство США/

2. гражданственность; права и обязанности гражданина

НБАРС > citizenship

-

10

citizenship

English-Russian big medical dictionary > citizenship

-

11

citizenship

[ˈsɪtɪznʃɪp]

citizenship гражданственность citizenship гражданство citizenship права и обязанности гражданина dual citizenship двойное гражданство obtain citizenship получать гражданство

English-Russian short dictionary > citizenship

-

12

citizenship

сущ.

пол.гражданство, подданство

She has applied for British citizenship. — Она подала заявление на получение британского гражданства.

See:

Англо-русский экономический словарь > citizenship

-

13

citizenship

Patent terms dictionary > citizenship

-

14

citizenship

Англо-русский синонимический словарь > citizenship

-

15

citizenship

1) гражда́нство с

2) гражда́нственность ж

The Americanisms. English-Russian dictionary. > citizenship

-

16

citizenship

подданство, гражданство, правовая связь индивида с государством.

* * *

сущ.

подданство, гражданство, правовая связь индивида с государством.

Англо-русский словарь по социологии > citizenship

-

17

citizenship

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > citizenship

-

18

citizenship

(термин, обычно применяемый для стран с республиканской формой правления, подданство — с монархической. Для стран-бывших колониальных империй иногда применяется старый термин national (национальная принадлежность по паспорту))

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > citizenship

-

19

citizenship

Англо-русский большой универсальный переводческий словарь > citizenship

-

20

citizenship

English-Russian dictionary of regional studies > citizenship

Страницы

- Следующая →

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

См. также в других словарях:

-

citizenship — Citizenship can refer to a political identity, a particular relation between state and individual, or a political activity. Strictly speaking, individuals in Britain are not citizens but subjects of the Crown, and British democracy rests not… … Encyclopedia of contemporary British culture

-

citizenship — cit·i·zen·ship n 1: the status of being a citizen 2: the quality of an individual s behavior as a citizen 3: domicile used esp. in federal diversity cases see also diversity jurisdiction at … Law dictionary

-

citizenship — UK US /ˈsɪtɪzənʃɪp/ noun [U] ► the state of being a member of a country, and having legal rights because of this: »British/Canadian/US citizenship → Compare RESIDENCY(Cf. ↑residency) ► the state of being a member of a particular group and… … Financial and business terms

-

Citizenship — Cit i*zen*ship, n. The state of being a citizen; the status of a citizen. [1913 Webster] … The Collaborative International Dictionary of English

-

citizenship — 1610s, from CITIZEN (Cf. citizen) + SHIP (Cf. ship) … Etymology dictionary

-

citizenship — [sit′ə zənship΄, sit′ə sənship΄] n. 1. the status or condition of a citizen 2. the duties, rights, and privileges of this status 3. a person s conduct as a citizen … English World dictionary

-

Citizenship — Citizen redirects here. For other uses, see Citizen (disambiguation). Civic duty redirects here. For the film, see Civic Duty (film). This article is about the civic duty of citizens. For information about the nationality laws of particular… … Wikipedia

-

citizenship — In political and legal theory, citizenship refers to the rights and duties of the member of a nation state or city. In some historical contexts, a citizen was any member of a city; that is, an urban collectivity which was relatively immune from… … Dictionary of sociology

-

citizenship — /sit euh zeuhn ship , seuhn /, n. 1. the state of being vested with the rights, privileges, and duties of a citizen. 2. the character of an individual viewed as a member of society; behavior in terms of the duties, obligations, and functions of a … Universalium

-

citizenship — n. 1) to grant citizenship 2) to acquire, receive citizenship 3) to revoke smb. s citizenship 4) to give up, renounce one s citizenship 5) dual citizenship * * * [ sɪtɪz(ə)nʃɪp] receive citizenship renounce one s citizenship dual citizenship to… … Combinatory dictionary

-

citizenship — noun ADJECTIVE ▪ full ▪ dual ▪ birthright (AmE) ▪ British, Chinese, US, etc … Collocations dictionary

Per GlobalCIT: A legal status and relation between an individual and a state that entails specific legal rights and duties. Citizenship is generally used as a synonym for nationality (see: nationality).

What is citizen in simple words?

1 : an inhabitant of a city or town especially : one entitled to the rights and privileges of a freeman. 2a : a member of a state. b : a native or naturalized person who owes allegiance to a government and is entitled to protection from it She was an American citizen but lived most of her life abroad.

What are words for citizenship?

nationality allegiance. body politic. citizenship. community. country. ethnic group. nation. native land.

What does citizenship mean in school?

By teaching children different themes of citizenship, you can help them learn how to positively contribute to their community. Be sure to focus on empathy, respect, compassion, diversity, and inclusion as you explore themes of citizenships with your class.

What is citizenship example?

An example of citizenship is someone being born in the United States and having access to all the same freedoms and rights as those already living in the US. The duties, rights, and privileges of this status.

What is meant by active citizenship?

Active citizenship or engaged citizenship refers to active participation of a citizen under the law of a nation discussing and educating themselves in politics and society, as well as a philosophy espoused by organizations and educational institutions which advocates that individuals, charitable organizations, and.

What is citizenship in social studies?

Social studies is a major vehicle for citizenship education, with a focus on nation‐building. Findings revealed four themes, namely identity, participation, awareness of the nation’s past, and thinking citizenry, located within the nationalistic, socially concerned and person oriented stances.

What is citizenship for kids?

Citizenship is everything that has to do with being a citizen, or full member, of a country. Citizens have rights that are given by the country’s government. For example, citizens have the right to be protected by a country’s laws. In return, citizens have duties that they owe to the country.

What does the word denizen mean?

: the act of making one a denizen : the process of being made a denizen.

What are good citizens called?

patriot. nounperson who loves his or her country. flag-waver. good citizen. loyalist.

How can I check my citizenship status?

How to Check U.S. Citizenship Application Status Online Find the Receipt Number for your U.S. citizenship application. (See “Receipt Numbers” below.) Visit the USCIS “Case Status Online” tracker. Enter your Receipt Number. Click “Check Status.”.

How can you show citizenship in your community?

Here’s a list of 10 things you can do right now to be a better citizen. Volunteer to be active in your community. Be honest and trustworthy. Follow rules and laws. Respect the rights of others. Be informed about the world around you. Respect the property of others. Be compassionate. Take responsibility for your actions.

What does citizenship mean on an application?

The country in which a person is born in, or naturalized that protects and to which that person owes allegiance. Applicants are required to complete Form N-400 to apply for U.S. Citizenship.

What does being a good citizen mean?

Conduct a classroom discussion on aspects of good citizenship, such as: obeying rules and laws, helping others, voting in elections, telling an adult if someone is a danger to themselves or others, and being responsible for your own actions and how they affect others. No one is born a good citizen.

What is citizenship answer?

citizenship, relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection. Citizenship implies the status of freedom with accompanying responsibilities. Citizenship is the most privileged form of nationality.

How do you become a citizen?

You can become a U.S. citizen by birth or through naturalization. Generally, people are born U.S. citizens if they are born in the United States or if they are born abroad to U.S. citizens. You may also derive U.S. citizenship as a minor following the naturalization of one or both parents.

What it means to be a citizen of the United States?

To be a citizen of the US means to not just be born or naturalized in the US, live here and enjoy the resources of this vast country, but to also be loyal and faithful to this nation. People who are born or choose to be citizens must defend the laws and pledge allegiance to the Constitution of the United States.

Why is citizenship important in society?

Citizenship is important for developing a strong moral code in individuals, but it’s also important for creating a safe, supportive society while protecting democracy, according to Young Citizens. Teaching citizenship also allows students to understand the difference between being a citizen and practicing citizenship.

What makes you a Filipino citizen?

Under the 1987 Philippine Constitution, Article IV, Section 1, it states that: Those whose fathers or mothers are citizens of the Philippines; Those born before January 17, 1973, of Filipino mothers, who elect Philippine citizenship upon reaching the age of majority; and. Those who are naturalized in accordance of law.

What is citizenship in community action?

Citizenship is “the person’s strong connection to the 5Rs of rights, responsibilities, roles, resources, and relationships that society offers to its members through public and social institutions.”[.

What is citizenship and why does it matter?

In its strictest sense, citizenship is a legal status that means a person has a right to live in a state and that state cannot refuse them entry or deport them. Moreover, as well as a legal status, citizenship can also indicate a subjective feeling of identity and social relations of reciprocity and responsibility.

What makes you a citizen of a state?

A state Citizen, also called a de jure Citizen, is an individual whose inalienable natural rights are recognized, secured, and protected by his/her state Constitution against State actions and against federal intrusion by the Constitution for the United States of America.

What are the three types of citizenship?

Types of citizenship: birth, descent and grant.

How do you become a citizen Duckster?

Who can become a citizen? In order to become a citizen a person must first legally immigrate to the U.S. and live here for five years. Immigrants can apply for a permanent resident card called a Green Card.

How do you show citizenship in school?

Reviews. A pair of teens narrates this program that identifies five pillars of good citizenship: be respectful of others and their property, be respectful of school property, follow school rules, demonstrate good character by being honest and dependable, and give back to the community.

The sociologist T.H. Marshall gave the following definition of citizenship in 1950:

Citizenship is a status bestowed on those who are full members of a community. All who possess the status are equal with respect to the rights and duties with which the status is endowed (Marshall 1983 [1950]: 253).

He equated community with the nation, and viewed membership of that community as primarily an individual ownership of a set of rights and corresponding duties. His version of citizenship has a distinguished pedigree: from Locke onwards, liberal citizenship has been seen as a status of the individual. The rights associated with this status in theory allow individuals to pursue their own conceptions of the good life, as long as they do not hinder other’s similar pursuits, and the state protects this status quo. In return, citizens have minimal responsibilities, which revolve primarily around keeping the state running, such as paying taxes, or participating in military service.

However, liberal citizenship is not the only form of citizenship that we can find globally. Indeed, insights from ethnography complicate this normative picture of liberal citizenship, as anthropologists have insisted on the specificity of citizenship in different contexts. Alternative possibilities might be civic republican or communitarian forms of citizenship. This is because political membership is related in complex ways to day-to-day practices of politics, and citizenship is a mechanism for making claims on different political communities, of which the state is just one. One important consequence of this is that anthropologists denaturalize liberal citizenship and ask questions about the actual constitution of political membership and subjectivity in a given context. In the move from political philosophy to anthropology, we see an important analytical shift take place from the normative to the descriptive: from what citizenship and citizens should be to a critical analysis of what they are.

The political community

The concept of citizenship has a long trajectory within political philosophy. Like anthropologists, political philosophers ask: how should we live with others in a political community? Here I trace some key moments in this enduring debate within political philosophy, a debate which informs most anthropological discussions of citizenship today. Aristotle (2013) is my starting point, as the most celebrated proponent of a civic republican tradition of citizenship that began in the early Greek city states. In the Politics, he discusses three very important issues: first, the question of how precisely to constitute membership – and exclusion; second, the nature of the citizen as person; and third, the nature of politics itself. The first question of membership was a particular problem in early Greek philosophical thought because of the presence of slaves, often in important bureaucratic positions in the government of the city. Aristotle’s assertion in the Politics that ‘man is a political animal’ was not an inclusive one, but referred only to certain men, those who were not slaves (women were quickly dismissed and then ignored, along with children). He described the citizen: a member of the political community (polis) who participates in government in the sense that he ‘gives judgement and holds office’. Secondly, Aristotle discussed in great depth the development of the citizen as a particular kind of man capable of living in the collectivity, who held and cultivated the associated virtues, such as respect for law and for others and a passion for politics. Finally, politics itself was intimately linked with speech in Aristotle’s thought. Discussion and debate were absolutely central to Athenian politics and personhood. So, citizenship was constituted through political practice, and political practice was constituted through speech and deliberation.

The key points here are, first, that citizenship is more than simply a status denoting membership of a polity but is constituted through a set of practices associated with participation in politics. Second, political subjectivity is something that cannot be assumed to exist but that must be created. For Aristotle, political subjects – citizens – are inherently collective and also eminently moral.

The second set of foundational philosophical texts I want to highlight are those of the social contract philosophers and the Liberal tradition. For Rousseau and Locke, social order can only be achieved through the acceptance of all to live via the agreement of the majority for the benefit of all. This is principally in order to protect property rights, as in the state of ‘natural freedom’ (Rousseau 1971) prior to the establishment of a state, property is always subject to the threat of what Locke called ‘the Invasion of others’. To overcome this danger each individual ‘puts into the community his person and all his powers under the supreme direction of the general will’, thus creating ‘civil freedom’ (Rousseau 1971). The political community therefore comes into being when individuals voluntarily subject themselves to the collectivity (meaning the state and the rule of law). As with Aristotle, political subjectivity is not to be assumed, but is created, and is intimately linked to moral questions of personal virtue. The American Declaration of Independence[1] (1776) and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man[2] (1789) were more radical, in their willingness to question the inevitability of the existing regime of state power and sovereignty; and then to claim sovereignty for ‘the people’. They did so by claiming the equality of men (sic.) in the name of individual rights, especially those to ‘Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness’ and ‘liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression’. The political context meant that they needed to claim liberty so that they could change sovereign power, but liberty could also be interpreted in the light of Rousseau and Locke’s position that true freedom comes through the respect for the rule of law, not through the absence of law (for Locke, see his Two Treatises of Government, 2003).