Royalty-Free Stock Photo

Download preview

The word Chocolate written by chocolate on white background

- white background,

- background,

- chocolate,

- white,

- word,

- written,

- food,

- space,

- frame,

- banner,

- design,

- silhouette,

- candy,

- isolated,

- splash,

- letters,

- concept,

- drawing,

- dessert,

- cream,

- calligraphy

More

Less

ID 84109325

© Kozpho

| Dreamstime.com

- 2

- 1

- Royalty-Free

- Extended licenses ?

-

XS

480x307px16.9cm x 10.8cm @72dpi

59kB | jpg

-

S

800x511px6.8cm x 4.3cm @300dpi

128kB | jpg

-

M

2167x1384px18.3cm x 11.7cm @300dpi

649kB | jpg

-

L

2797x1787px23.7cm x 15.1cm @300dpi

1001kB | jpg

-

XL

3539x2260px30cm x 19.1cm @300dpi

1.5MB | jpg

-

MAX

6635x4238px56.2cm x 35.9cm @300dpi

3.5MB | jpg

-

TIFF

9383x5993px79.4cm x 50.7cm @300dpi

??.?MB | tiff

-

Unlimited Seats (U-EL)

-

Web Usage (W-EL)

-

Print usage (P-EL)

-

Sell the rights (SR-EL 1)

-

Sell the rights (SR-EL 3)

-

Sell the rights (SR-EL)

Add to lightbox

FREE DOWNLOAD

Мы принимаем все основные кредитные карты из России

Extended licenses

Designers also selected these stock photos

Gardener

Petals of a red rose isolated

Three titmouse birds in winter

Honey drop

Single red cherry sliced almonds isolated on white background

Skimmia japonica buds

Tied cinnamon sticks, isolated on white background, clipping pat

More stock photos from Kozpho’s portfolio

The word chocolate with pieces of white porous chocolate bar

The word Chocolate written by liquid chocolate on white

Word Chocolate written with liquid chocolate in a gothic style

The word chocolate with cracked sunflower seed isolated on white background

The word chocolate with walnuts on a white background

The word Chocolate written by liquid chocolate on white background

Word Chocolate written with liquid chocolate in a gothic style

The word chocolate with a broken porous chocolate bar, isolated on white background

Word Chocolate written with liquid chocolate in a gothic style

The word chocolate with different nuts on a white background

The word chocolate written with liquid chocolate isolated on white background

Word Chocolate written with liquid hot chocolate

Word Chocolate written with liquid chocolate in a gothic style

The word chocolate written with liquid chocolate on a white

Related categories

-

Industries

Food & Beverages -

Objects

Isolated

Browse categories

- Abstract

- Animals

- Arts & Architecture

- Business

- Editorial

- Holidays

- IT & C

- Illustrations & Clipart

- Nature

- People

- Technology

- Travel

- Web Design Graphics

Extended licenses

- Home

- Stock Photos

- Food & Beverages

- White background

- The word Chocolate written by chocolate on white

First Known Use: Around 1580

Etymology:

This week, people around the world will be opening heart-shaped boxes with “the food of the gods” nestled in crepe paper inside. But it took a lot of scientific and anthropological work to unearth the origins of both the tasty recipe and the word chocolate—which some anthropologists argue is an Indigenous word that has not been Anglicized.

The Bean Behind The Bars

“If the history of cacao were a 24-hour cycle, the glossy chocolate bars that we love and the confections that we love would only occupy a few seconds,” culinary historian Maricel Presilla told the The Slow Melt podcast.

That long history begins with the domestication of cacao, the bean used to make cocoa and chocolate. Just last year, researchers unearthed residual traces of DNA from Theobroma cacao in ceramic vessels from the Amazon basin. The vessels date back to roughly 3000 BCE, more than 1,500 years earlier than previously thought.

It’s typically thought that cacao was used for beverages, but that’s too simple of an explanation, says Carla D. Martin.

Martin is an anthropologist at Harvard University, and the founder and executive director of the Fine Cacao and Chocolate Institute. Yes, ancient people did drink it. But the beans were also used as flavoring for other foods, and as ritual offerings. They were also used as currency in Nicaragua, Mexico, and colonial Guatemala (which is now present day El Salvador). The Indigenous Pipil people in the Izalcos, a region of El Salvador, even did away with other trade items like feathers, and used cacao as their sole currency. Other regions followed their lead, and “it’s like [the people of] the Izalcos became the Swiss bankers,” says Kathryn Sampeck, an anthropologist at Illinois State University. In her research, Sampeck noticed that as cacao production was declining elsewhere during the early 1500s, the Izalcos produced “astronomical” amounts of the bean.

“I’ve done some analyses that look at the production levels in this region comparing it to other places, and it’s crazy,” Sampeck says. “Out of this port, 1.2 billion cacao beans per year for a span of at least 15 years—and that’s legal trade.” Because cacao was their sole currency, when Sampeck examined financial records from the region, she found evidence of extreme inflation due to the megaproduction of the bean.”

Prices in the Izalcos were at a minimum three times as much as the next-highest cacao producers, and sometimes as much as ten times the amount. “So, when I say when I say ‘astronomical,’ I mean it’s really astounding what this little place was producing,” she says.

When the Spanish arrived in what is now Central America, they too were quick to accept cacao as official payment, and even brought it back to Spain and incorporated it into their own monetary system for a time.

“[The Spaniards] had these big metal coins, and if they needed to make change to buy a tomato or something small, the only way to make change was to get out a knife and carve out a chunk of that,” says Martin. “It was totally impractical.”

It was this perceived value that gave cacao and chocolate a leg up on achiote or other ingredients from the Americas. In fact, cacao functioned as small change in the Izalcos as late as the 19th century.

From Cacao To Chocolate

Around 1580, the word chocolate cropped up in both European and Mexican texts, says Sampeck. And it wasn’t simply another name for cacao—it was the Pipil’s Indigenous Nahuat word referring specifically to the special drink of the Izalcos, where the first prototype recipes for what we call chocolate emerged.

“I think of it as a phenomenon kind of like buffalo chicken wings or Q-tips or anything like that,” says Sampeck, “where there’s this kind of branding that happens in the 16th century around 1580 that really identified that the word for a typical, local drink starts to become the name for for the seed and even a tree and all of that. It becomes much more generalized.”

As cacao’s popularity skyrocketed across the world, the word for the Pipil’s special drink exploded in the colonial and transatlantic markets, she says.

But according to Sampeck, the word never Anglicized. “It’s one of the words that’s never been translated… Every day, across the world, people are speaking [the Indigenous language] Nahuat,” she says. (Sampeck notes that there are scholars and linguists who argue that the word is a blend of Indigenous languages, or that it has a Maya root. But it was the Pipil people who were speaking the word at the time that it became adopted in other languages.)

“I think one of the most common beliefs is that chocolate is something European in nature,” says Carla Martin. “But what our research has really shown is that chocolate is in fact an Indigenous foodstuff that has conquered the hearts and minds of the world. So, whenever we’re consuming chocolate, we’re consuming something that was really designed in the Americas, by the Indigenous people of the Americas—and that’s really unique.”

Choc Full Of Science

Between that first domestication of cacao and today, researchers and chocolate makers have scientifically engineered chocolate to taste—and feel—even better to our palates.

“People like chocolate for many reasons that they perhaps don’t directly think about,” food scientist Richard Ludesher told Science Friday in 2014. “They think about the taste of chocolate. They think about the sweetness of chocolate. But an extremely important property of chocolate is its texture, and its property of being hard at room temperature and yet completely melty in your mouth.”

That melt-in-your-mouth property, surprisingly, comes down to crystals. Chocolate is a crystalline solid, which means that its molecules, atoms, and ions act together in an orderly pattern and have a flat surface. Creating those crystal formations is part of the art of making chocolate.

First, chocolate makers grind the cocoa nibs into a chocolate liquor. Once the cocoa particles are suspended in that liquor, the candy makers add other ingredients, like sugar. Then, they mix the whole melty, delicious liquor together to reduce the size of particles and release flavors and acids that are embedded in it. That process is essential for flavoring the chocolate, but it leaves the cocoa butter unstable. In order to remedy that, chocolatiers slowly heat the mixture to a point that melts away all the unwanted crystal formations, but leaves the ones necessary for stabilization.

“Chocolate should have a certain look to it, have a gloss and a sheen to it. It needs to have a snap, and it needs to have the right mouth feel,” says Ludescher. “What you have is a fairly complicated thing. And when you put it in your mouth, and you wait long enough—if you’re not impatient—it will melt back to that liquor and release all the flavor.”

Sources And Further Reading:

- Special thanks to Carla D. Martin and Kathryn Sampeck

- “The use and domestication of Theobroma cacao during the mid-Holocene in the upper Amazon” (Nature Ecology and Evolution)

- “The Deep Origin: Latin America” (The Slow Melt Podcast, Episode

- “The History of the Word for Cacao in Ancient Mesoamerica” (Ancient Mesoamerica)

- “The Bitter and Sweet of Chocolate in Europe” (Socio.hu: The Social Meaning of Food: Special Issue in English No. 3)

- Choc Full of Science (Science Friday)

Meet the Writer

About Johanna Mayer

@yohannamayer

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.

РАЗРАБОТКА УРОКА АНГЛИЙСКОГО ЯЗЫКА

8 КЛАСС

«THE HISTORY OF CHOCOLATE»

Предлагаемый Вашему вниманию урок, разработанный на основе материалов учебного пособия «Open Doors 2» издательства «Oxford University Press», демонстрирует различные виды работы с текстом.

Цели урока:

- Обеспечить усвоение новой лексики по теме урока, обучать использованию новой и уже известной лексики в речи (в незнакомой речевой ситуации).

- Развивать навыки чтения, устной речи, аудирования.

- Развивать умения обрабатывать информацию, выделять в ней главное, распознавать и соотносить различную информацию.

План урока:

- Организационный момент. Целеполагание.

- Введение в тему урока.

- Речевая разминка (скороговорка)

- Работа с текстовыми заданиями.

- Подведение итогов.

- Домашнее задание.

Ход урока:

- Организационный момент.

- Введение в тему урока.

Слово учителя.

Some things in our life may be not so important but they are very pleasant and sweet, for example, chocolate. Do you like chocolate? I think, most of people like chocolate. What do you know about chocolate? (pupils’ answers) Well, I see that you know very little about it. Let’s study more. I want to suggest you some different tasks. If you can do them well you’ll know more about this delicious thing. So, look at the blackboard. You can see the sectors: A – F. Here you can find the tasks. You can choose any of these sectors, do your task and then you have to match the text from the sector with one of these subjects.

(on the blackboard: sectors A – F, names of the subjects – History, Economics, Plant Biology, Human Biology, Language Study, Geography)

Некоторые вещи в нашей жизни не такие важные, но они очень приятные и сладкие, как, например, шоколад. Вы любите шоколад? Я думаю, что большинство людей любит шоколад. Но что мы знаем о шоколаде? (ответы учеников) Да, я вижу, что знаете вы немного. Давайте узнаем больше. Я предлагаю вам выполнить несколько заданий. Если вы выполните эти задания, вы узнаете больше об этой вкусной вещи. Итак, посмотрите на доску. Вы можете увидеть здесь сектора от А до F. Здесь же вы сможете найти задания. Вы выбираете любой сектор, выполняете задание и затем вы должны будете соотнести текст этого сектора с одним из учебных предметов. (на доске сектора от А до F, названия предметов: история, экономика, биология растений, биология человека, языкознание, география)

3. Речевая разминка (скороговорка)

Chicken and chips, cheese and chocolate.

Chips and chicken, chocolate and cheese.

4. Работа с текстовыми заданиями.

Учащиеся выбирают сектор, выполняют задание, соотносят тематику сектора с учебными предметами.

Сектор А – Read and translate the text. Answer the question: Where does the word “chocolate” come from? (Language Study)

Прочитать и перевести текст. Ответить на вопрос: Откуда пришло слово «шоколад»? (Языкознание)

Text: Where does the word ‘chocolate’ come from?

The English word ‘chocolate’ came into the language from French (‘chocolat’) or Spanish (‘chocolate’). The French and Spanish words are derived from the Aztec word ‘chocolatl’. Similar words exist in many languages.

English chocolate French chocolat

German Schokolade Portuguese chocolate

Italian cioccolata Russian шоколад

Spanish chocolate Turkish cikolata

Сектор B – Answer the questions: What is chocolate made of? (cocoa plant) Where is cocoa plant grown? Let’s read the text and check your answers. Find the mistake in the text. (Geography)

Ответить на вопрос: Из чего делают шоколад? (из какао) Где выращивают какао-деревья? Прочитайте текст и проверьте ответы. В тексте найдите ошибку. (География)

Text: Where is the cocoa plant grown?

The cocoa plant is grown in tropical countries near the equator. It needs a hot and wet climate and plenty of sun. Some countries are especially famous for their producing of chocolate, for example, Benin or Nigeria.

Сектор C – Read the text. Match dates and events. (History)

Прочитать текст. Соединить даты и события. (История)

Text

- The Aztecs, in Mexico, were conquered by Hernan 1650

Hortes, from Spain. The cocoa plant was brought from

Mexico to Europe. 1870

- In London, the first Chocolate House was opened.

- Milk chocolate was invented in Switzerland. 1521

Сектор D – Put the mixed parts of the text in the right order. Read, translate. Describe the picture using the text. (Plant Biology)

Расположить части текста в правильном порядке. Прочитать, перевести текст. Описать картинку, используя текст. (Биология растений)

Text

Growing the cocoa plant requires time, skill and patience.

a) The beans are dried for twenty days. They turn brown. Then they are sold and sent all over the world. (3)

b) The forests are cleared and the cocoa beans are planted. After four years, the young cocoa trees begin to appear. (1)

c) The cocoa pods turn yellow when they are ripe. The farm workers cut the cocoa pods and take out the beans. (2)

Сектор E – Listen to the text and complete it. (Economics)

Послушайте текст и заполните пропуски. (Экономика)

How big is the chocolate industry?

The chocolate _______(1) is absolutely enormous. In ____(2) alone, 60,000 people are employed in the______(3). The United Kingdom exports 70,000 tones of chocolate_______(4). This produces about £3 billion (£3,000,000,000) of income for the ________(5). It is said that the industry _______(6) at least twenty billion pieces of ________(7) a year!

1 – industry, 2 – Britain, 3 – industry, 4 – each year, 5 – country, 6 – produces, 7 — chocolate

Сектор F – Read the text and try to guess what words are missed. Write these words. (Human Biology)

Прочитайте текст, догадайтесь, какие слова пропущены. Запишите эти слова. (Биология человека)

Text: Is chocolate good for us? Try to guess what words are missed.

Chocolate is a g____d (good) source of e_______y (energy). It can contain up to 40% f__t (fat) and 50% s____r (sugar). Mountaineers often take chocolate with them on ex__________ns (expeditions) because they need extra e_______y (energy). But other types of food also pr______de (provide) us with energy, and too m____h (much) fat and sugar is bad for you. So en___y (enjoy) your chocolate, but d____’t (don’t) eat too much!

4. Подведение итогов.

5. Домашнее задание. Write a composition about chocolate. Написать сочинение о шоколаде (с опорой на изученный материал)

R4: The pronunciation of chocolate varies from person to person and situationally. The second ‘o’ can be omitted entirely or pronounced as a schwa. In my experience, the schwa only appears when people want to emphasise the word, but ultimately both pronunciations are valid — but that’s limited to my dialect. A bunch of people holding that their own pronunciation is one true pronunciation isn’t really badling, however the following statements are:

Most people saying it, or how you want to hear it, doesn’t make it so.

As pointed out in the thread, language is defined by how its native speakers use it. Most people saying ‘chocolate’ with two syllables, by definition, makes it a valid pronunciation. And no, it’s not a matter of people just saying the second ‘o’ ‘really fast’.

That’s not quite how linguistics works. Meaning can change and spellings can change as our uses change to meet our needs. There’s still 3 syllables in the word chocolate, though you don’t have to pronounce them for the meaning to be conveyed.

The commenter seems to mistakenly understand syllables as being a unit of writing, not a unit of speech [EDIT: They’ve clarified their point in a later comment]. The idea that a word is three syllables even if its pronounced (by a subset of native speakers) as two is not correct. If only two syllables are said, then it’s a two syllable word for that speaker. They also (weirdly) recognise the meaning and spelling can change, but don’t believe that this can extend to number of syllables within a word???

Finally, Tom Scott appears to have predicted this argument with his very pointed caveat about vowel reduction in the word ‘chocolate’ in this video.

EDIT: The commenter has put forward a more detailed explanation of their argument since I posted my R4:

Again, you’re able to pronounce words however you want and as long as you express your meaning correctly and everyone understands you, then you’re perfectly correct. But the word chocolate has 3 syllables. The middle syllable is just barely spoken, and often ignored completely. But in the context of making specific statements about the correct pronunciation of the word, the 3rd syllable still exists.

It’d be written out as /ˈt͡ʃɒk(ə)lɪt/, /ˈt͡ʃɒk(ə)lət/, or /t͡ʃɔk(ə)lət/.

You’ll notice the middle syllable is a hushed shwa soun, meaning it’s barely pronounced. There’s nothing incorrect about saying the word with 2 syllables, but if you’re going to get specific about how many syllables it has, it’s 3.

(emphasis bolded)

The user has fallen into a trap that you can talk about the word as if it has one correct pronunciation. ‘Chocolate’ clearly has variable pronunciation and both two-syllable and three-syllable pronunciations are valid in English — therefore the word cannot be definitively described as solely being a two-syllable or three-syllable word. Schrödinger’s syllable count.

The IPA transcriptions disprove their point — first in the fact that three transcriptions are provided for the ‘correct pronunciation’, and second in that parentheses generally indicate optional or variable pronunciation, i.e. that the schwa can be omitted.

Chocolate truffles

Cheryl Carlin

When most of us hear the word chocolate, we picture a bar, a box of bonbons, or a bunny. The verb that comes to mind is probably «eat,» not «drink,» and the most apt adjective would seem to be «sweet.» But for about 90 percent of chocolate’s long history, it was strictly a beverage, and sugar didn’t have anything to do with it.

«I often call chocolate the best-known food that nobody knows anything about,» said Alexandra Leaf, a self-described «chocolate educator» who runs a business called Chocolate Tours of New York City.

The terminology can be a little confusing, but most experts these days use the term «cacao» to refer to the plant or its beans before processing, while the term «chocolate» refers to anything made from the beans, she explained. «Cocoa» generally refers to chocolate in a powdered form, although it can also be a British form of «cacao.»

Etymologists trace the origin of the word «chocolate» to the Aztec word «xocoatl,» which referred to a bitter drink brewed from cacao beans. The Latin name for the cacao tree, Theobroma cacao, means «food of the gods.»

Many modern historians have estimated that chocolate has been around for about 2000 years, but recent research suggests that it may be even older.

In the book The True History of Chocolate, authors Sophie and Michael Coe make a case that the earliest linguistic evidence of chocolate consumption stretches back three or even four millennia, to pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica such as the Olmec.

Last November, anthropologists from the University of Pennsylvania announced the discovery of cacao residue on pottery excavated in Honduras that could date back as far as 1400 B.C.E. It appears that the sweet pulp of the cacao fruit, which surrounds the beans, was fermented into an alcoholic beverage of the time.

«Who would have thought, looking at this, that you can eat it?» said Richard Hetzler, executive chef of the café at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, as he displayed a fresh cacao pod during a recent chocolate-making demonstration. «You would have to be pretty hungry, and pretty creative!»

It’s hard to pin down exactly when chocolate was born, but it’s clear that it was cherished from the start. For several centuries in pre-modern Latin America, cacao beans were considered valuable enough to use as currency. One bean could be traded for a tamale, while 100 beans could purchase a good turkey hen, according to a 16th-century Aztec document.

/

© Brian Hagiwara Studio, Inc./the food passionates/Corbis

/

© the food passionates/Corbis

/

© SAMSUL SAID/Reuters/Corbis

/

© Jacob J. Gayer/National Geographic Society/Corbis

/

© Enrique Perez Huerta/Demotix/Corbis

/

© Owen Franken/Corbis

/

© Underwood and Underwood/National Geographic Society/Corbis

/

© 167/Kelley Miller/Ocean/Corbis

Both the Mayans and Aztecs believed the cacao bean had magical, or even divine, properties, suitable for use in the most sacred rituals of birth, marriage and death. According to Chloe Doutre-Roussel’s book The Chocolate Connoisseur, Aztec sacrifice victims who felt too melancholy to join in ritual dancing before their death were often given a gourd of chocolate (tinged with the blood of previous victims) to cheer them up.

Sweetened chocolate didn’t appear until Europeans discovered the Americas and sampled the native cuisine. Legend has it that the Aztec king Montezuma welcomed the Spanish explorer Hernando Cortes with a banquet that included drinking chocolate, having tragically mistaken him for a reincarnated deity instead of a conquering invader. Chocolate didn’t suit the foreigners’ tastebuds at first –one described it in his writings as «a bitter drink for pigs» – but once mixed with honey or cane sugar, it quickly became popular throughout Spain.

By the 17th century, chocolate was a fashionable drink throughout Europe, believed to have nutritious, medicinal and even aphrodisiac properties (it’s rumored that Casanova was especially fond of the stuff). But it remained largely a privilege of the rich until the invention of the steam engine made mass production possible in the late 1700s.

In 1828, a Dutch chemist found a way to make powdered chocolate by removing about half the natural fat (cacao butter) from chocolate liquor, pulverizing what remained and treating the mixture with alkaline salts to cut the bitter taste. His product became known as «Dutch cocoa,» and it soon led to the creation of solid chocolate.

The creation of the first modern chocolate bar is credited to Joseph Fry, who in 1847 discovered that he could make a moldable chocolate paste by adding melted cacao butter back into Dutch cocoa.

By 1868, a little company called Cadbury was marketing boxes of chocolate candies in England. Milk chocolate hit the market a few years later, pioneered by another name that may ring a bell – Nestle.

In America, chocolate was so valued during the Revolutionary War that it was included in soldiers’ rations and used in lieu of wages. While most of us probably wouldn’t settle for a chocolate paycheck these days, statistics show that the humble cacao bean is still a powerful economic force. Chocolate manufacturing is a more than 4-billion-dollar industry in the United States, and the average American eats at least half a pound of the stuff per month.

In the 20th century, the word «chocolate» expanded to include a range of affordable treats with more sugar and additives than actual cacao in them, often made from the hardiest but least flavorful of the bean varieties (forastero).

But more recently, there’s been a «chocolate revolution,» Leaf said, marked by an increasing interest in high-quality, handmade chocolates and sustainable, effective cacao farming and harvesting methods. Major corporations like Hershey’s have expanded their artisanal chocolate lines by purchasing smaller producers known for premium chocolates, such as Scharffen Berger and Dagoba, while independent chocolatiers continue to flourish as well.

«I see more and more American artisans doing incredible things with chocolate,» Leaf said. «Although, I admit that I tend to look at the world through cocoa-tinted glasses.»

The True History of Chocolate

Recommended Videos

Chocolate is a food made from roasted and ground cacao seed kernels that is available as a liquid, solid, or paste, either on its own or as a flavoring agent in other foods. Cacao has been consumed in some form since at least the Olmec civilization (19th-11th century BCE),[1][2] and the majority of Mesoamerican people ─ including the Maya and Aztecs ─ made chocolate beverages.[3]

Chocolate bars in its most common dark, milk, and white varieties. |

|

| Region or state | Mesoamerica |

|---|---|

| Main ingredients | Chocolate liquor, cocoa butter for white chocolate, often with added sugar |

|

The seeds of the cacao tree have an intense bitter taste and must be fermented to develop the flavor. After fermentation, the seeds are dried, cleaned, and roasted. The shell is removed to produce cocoa nibs, which are then ground to cocoa mass, unadulterated chocolate in rough form. Once the cocoa mass is liquefied by heating, it is called chocolate liquor. The liquor may also be cooled and processed into its two components: cocoa solids and cocoa butter. Baking chocolate, also called bitter chocolate, contains cocoa solids and cocoa butter in varying proportions, without any added sugar. Powdered baking cocoa, which contains more fiber than cocoa butter, can be processed with alkali to produce dutch cocoa. Much of the chocolate consumed today is in the form of sweet chocolate, a combination of cocoa solids, cocoa butter or added vegetable oils, and sugar. Milk chocolate is sweet chocolate that additionally contains milk powder or condensed milk. White chocolate contains cocoa butter, sugar, and milk, but no cocoa solids.

Chocolate is one of the most popular food types and flavors in the world, and many foodstuffs involving chocolate exist, particularly desserts, including cakes, pudding, mousse, chocolate brownies, and chocolate chip cookies. Many candies are filled with or coated with sweetened chocolate. Chocolate bars, either made of solid chocolate or other ingredients coated in chocolate, are eaten as snacks. Gifts of chocolate molded into different shapes (such as eggs, hearts, coins) are traditional on certain Western holidays, including Christmas, Easter, Valentine’s Day, and Hanukkah. Chocolate is also used in cold and hot beverages, such as chocolate milk and hot chocolate, and in some alcoholic drinks, such as creme de cacao.

Although cocoa originated in the Americas, West African countries, particularly Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, are the leading producers of cocoa in the 21st century, accounting for some 60% of the world cocoa supply.

With some two million children involved in the farming of cocoa in West Africa, child slavery and trafficking associated with the cocoa trade remain major concerns.[4][5] A 2018 report argued that international attempts to improve conditions for children were doomed to failure because of persistent poverty, absence of schools, increasing world cocoa demand, more intensive farming of cocoa, and continued exploitation of child labor.[4]

History

Mesoamerican usage

Image from a Maya ceramic depicting a container of frothed chocolate

Chocolate has been prepared as a drink for nearly all of its history. For example, one vessel found at an Olmec archaeological site on the Gulf Coast of Veracruz, Mexico, dates chocolate’s preparation by pre-Olmec peoples as early as 1750 BC.[6] On the Pacific coast of Chiapas, Mexico, a Mokaya archaeological site provides evidence of cocoa beverages dating even earlier to 1900 BC.[7][6] The residues and the kind of vessel in which they were found indicate the initial use of cocoa was not simply as a beverage, but the white pulp around the cocoa beans was likely used as a source of fermentable sugars for an alcoholic drink.[8]

Aztec. Man Carrying a Cacao Pod, 1440–1521. Volcanic stone, traces of red pigment. Brooklyn Museum.

An early Classic-period (460–480 AD) Maya tomb from the site in Rio Azul had vessels with the Maya glyph for cocoa on them with residue of a chocolate drink, which suggests that the Maya were drinking chocolate around 400 AD.[9] Documents in Maya hieroglyphs stated chocolate was used for ceremonial purposes in addition to everyday life.[10] The Maya grew cacao trees in their backyards[11] and used the cocoa seeds the trees produced to make a frothy, bitter drink.[12]

By the 15th century, the Aztecs had gained control of a large part of Mesoamerica and had adopted cocoa into their culture. They associated chocolate with Quetzalcoatl, who, according to one legend, was cast away by the other gods for sharing chocolate with humans,[13] and identified its extrication from the pod with the removal of the human heart in sacrifice.[14] In contrast to the Maya, who liked their chocolate warm, the Aztecs drank it cold, seasoning it with a broad variety of additives, including the petals of the Cymbopetalum penduliflorum tree, chili pepper, allspice, vanilla, and honey.

The Aztecs were unable to grow cocoa themselves, as their home in the Mexican highlands was unsuitable for it, so chocolate was a luxury imported into the empire.[13] Those who lived in areas ruled by the Aztecs were required to offer cocoa seeds in payment of the tax they deemed «tribute».[13] Cocoa beans were often used as currency.[15] For example, the Aztecs used a system in which one turkey cost 100 cocoa beans[16] and one fresh avocado was worth three beans.[17]

The Maya and Aztecs associated cocoa with human sacrifice, and chocolate drinks specifically with sacrificial human blood.[18][19]

The Spanish royal chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés described a chocolate drink he had seen in Nicaragua in 1528, mixed with achiote: «because those people are fond of drinking human blood, to make this beverage seem like blood, they add a little achiote, so that it then turns red. … and part of that foam is left on the lips and around the mouth, and when it is red for having achiote, it seems a horrific thing, because it seems like blood itself.»[19]

European adaptation

Chocolate soon became a fashionable drink of the European nobility after the discovery of the Americas. The morning chocolate by Pietro Longhi; Venice, 1775–1780

Until the 16th century, no European had ever heard of the popular drink from the Central American peoples.[13] Christopher Columbus and his son Ferdinand encountered the cocoa bean on Columbus’s fourth mission to the Americas on 15 August 1502, when he and his crew stole a large native canoe that proved to contain cocoa beans among other goods for trade.[20] Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés may have been the first European to encounter it, as the frothy drink was part of the after-dinner routine of Montezuma.[9][21] José de Acosta, a Spanish Jesuit missionary who lived in Peru and then Mexico in the later 16th century, wrote of its growing influence on the Spaniards:

Although bananas are more profitable, cocoa is more highly esteemed in Mexico… Cocoa is a smaller fruit than almonds and thicker, which toasted do not taste bad. It is so prized among the Indians and even among Spaniards… because since it is a dried fruit it can be stored for a long time without deterioration, and they brings ships loaded with them from the province of Guatemala… It also serves as currency, because with five cocoas you can buy one thing, with thirty another, and with a hundred something else, without there being contradiction; and they give these cocoas as alms to the poor who beg for them. The principal product of this cocoa is a concoction which they make that they call «chocolate», which is a crazy thing treasured in that land, and those who are not accustomed are disgusted by it, because it has a foam on top and a bubbling like that of feces, which certainly takes a lot to put up with. Anyway, it is the prized beverage which the Indians offer to nobles who come to or pass through their lands; and the Spaniards, especially Spanish women born in those lands die for black chocolate. This aforementioned chocolate is said to be made in various forms and temperaments, hot, cold, and lukewarm. They are wont to use spices and much chili; they also make it into a paste, and it is said that it is a medicine to treat coughs, the stomach, and colds. Whatever may be the case, in fact those who have not been reared on this opinion are not appetized by it.[22]

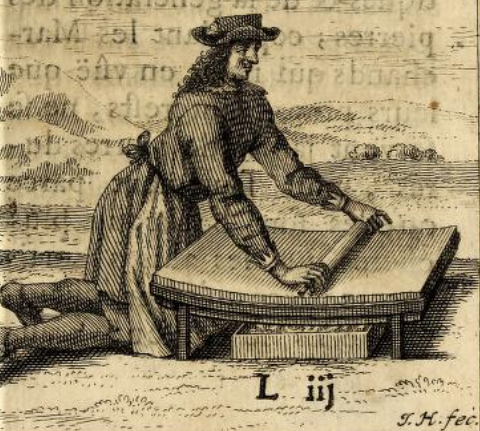

«Traités nouveaux & curieux du café du thé et du chocolate», by Philippe Sylvestre Dufour, 1685 («New and curious treatises of coffee, tea and chocolate»)

While Columbus had taken cocoa beans with him back to Spain,[20] chocolate made no impact until Spanish friars introduced it to the Spanish court.[13] After the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs, chocolate was imported to Europe. There, it quickly became a court favorite. It was still served as a beverage, but the Spanish added sugar, as well as honey (the original sweetener used by the Aztecs for chocolate), to counteract the natural bitterness.[16] Vanilla, another indigenous American introduction, was also a popular additive, with pepper and other spices sometimes used to give the illusion of a more potent vanilla flavor. Unfortunately, these spices tended to unsettle the European constitution; the Encyclopédie states, «The pleasant scent and sublime taste it imparts to chocolate have made it highly recommended; but a long experience having shown that it could potentially upset one’s stomach», which is why chocolate without vanilla was sometimes referred to as «healthy chocolate».[23] By 1602, chocolate had made its way from Spain to Austria.[24] By 1662, Pope Alexander VII had declared that religious fasts were not broken by consuming chocolate drinks. Within about a hundred years, chocolate established a foothold throughout Europe.[13]

Dutch chemist Coenraad Johannes van Houten invented «Dutch cocoa» by treating cocoa mass with alkaline salts to reduce the natural bitterness without adding sugar or milk to get usable cocoa powder.

The new craze for chocolate brought with it a thriving slave market, as between the early 1600s and late 1800s, the laborious and slow processing of the cocoa bean was manual.[13] Cocoa plantations spread, as the English, Dutch, and French colonized and planted. With the depletion of Mesoamerican workers, largely to disease, cocoa production was often the work of poor wage laborers and African slaves. Wind-powered and horse-drawn mills were used to speed production, augmenting human labor. Heating the working areas of the table-mill, an innovation that emerged in France in 1732, also assisted in extraction.[25]

Solid chocolate

Despite the drink remaining the traditional form of consumption for a long time, solid chocolate was increasingly consumed since the 18th century.[26][27] Tablets, facilitating the consumption of chocolate under its solid form, have been produced since the early 19th century. Cailler (1819)[28] and Menier (1836)[29] are early examples. In 1830, chocolate is paired with hazelnuts, an innovation due to Kohler.[30]

Meanwhile, new processes that sped the production of chocolate emerged early in the Industrial Revolution. In 1815, Dutch chemist Coenraad van Houten introduced alkaline salts to chocolate, which reduced its bitterness.[13] A few years thereafter, in 1828, he created a press to remove about half the natural fat (cocoa butter) from chocolate liquor, which made chocolate both cheaper to produce and more consistent in quality. This innovation introduced the modern era of chocolate.[20]

Known as «Dutch cocoa», this machine-pressed chocolate was instrumental in the transformation of chocolate to its solid form when, in 1847, English chocolatier Joseph Fry discovered a way to make chocolate moldable when he mixed the ingredients of cocoa powder and sugar with melted cocoa butter.[16] Subsequently, his chocolate factory, Fry’s of Bristol, England, began mass-producing chocolate bars, Fry’s Chocolate Cream, launched in 1866, and they became very popular.[31] Milk had sometimes been used as an addition to chocolate beverages since the mid-17th century, but in 1875 Swiss chocolatier Daniel Peter invented milk chocolate by mixing a powdered milk developed by Henri Nestlé with the liquor.[13][20] In 1879, the texture and taste of chocolate was further improved when Rudolphe Lindt invented the conching machine.[32]

Besides Nestlé, several notable chocolate companies had their start in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Rowntree’s of York set up and began producing chocolate in 1862, after buying out the Tuke family business. Cadbury was manufacturing boxed chocolates in England by 1868.[13] Manufacturing their first Easter egg in 1875, Cadbury created the modern chocolate Easter egg after developing a pure cocoa butter that could easily be molded into smooth shapes.[33] In 1893, Milton S. Hershey purchased chocolate processing equipment at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and soon began the career of Hershey’s chocolates with chocolate-coated caramels.

Introduction to the United States

The Baker Chocolate Company, which makes Baker’s Chocolate, is the oldest producer of chocolate in the United States. In 1765 Dr. James Baker and John Hannon founded the company in Boston. Using cocoa beans from the West Indies, the pair built their chocolate business, which is still in operation.[34][35]

White chocolate was first introduced to the U.S. in 1946 by Frederick E. Hebert of Hebert Candies in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, near Boston, after he had tasted «white coat» candies while traveling in Europe.[36][35]

Etymology

Cocoa, pronounced by the Olmecs as kakawa,[1] dates to 1000 BC or earlier.[1] The word «chocolate» entered the English language from Spanish in about 1600.[37] The word entered Spanish from the word chocolātl in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. The origin of the Nahuatl word is uncertain, as it does not appear in any early Nahuatl source, where the word for chocolate drink is cacahuatl, «cocoa water». It is possible that the Spaniards coined the word (perhaps in order to avoid caca, a vulgar Spanish word for «faeces») by combining the Yucatec Mayan word chocol, «hot», with the Nahuatl word atl, «water».[38] A widely cited proposal is that the derives from unattested xocolatl meaning «bitter drink» is unsupported; the change from x- to ch- is unexplained, as is the -l-. Another proposed etymology derives it from the word chicolatl, meaning «beaten drink», which may derive from the word for the frothing stick, chicoli.[39] Other scholars reject all these proposals, considering the origin of first element of the name to be unknown.[40] The term «chocolatier», for a chocolate confection maker, is attested from 1888.[41]

Types

Chocolate is commonly used as a coating for various fruits such as cherries and/or fillings, such as liqueurs

Several types of chocolate can be distinguished. Pure, unsweetened chocolate, often called «baking chocolate», contains primarily cocoa solids and cocoa butter in varying proportions. Much of the chocolate consumed today is in the form of sweet chocolate, which combines chocolate with sugar.

By cocoa content

Raw chocolate

Raw chocolate is chocolate produced primarily from unroasted cocoa beans.

Dark

Dark chocolate is produced by adding fat and sugar to the cocoa mixture. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration calls this «sweet chocolate», and requires a 15% concentration of chocolate liquor. European rules specify a minimum of 35% cocoa solids.[42] A higher amount of cocoa solids indicates more bitterness. Semisweet chocolate is dark chocolate with low sugar content. Bittersweet chocolate is chocolate liquor to which some sugar (typically a third), more cocoa butter and vanilla are added.[43] It has less sugar and more liquor than semisweet chocolate, but the two are interchangeable in baking. It is also known to last for two years if stored properly. As of 2017, there is no high-quality evidence that dark chocolate affects blood pressure significantly or provides other health benefits.[44]

Milk

Milk chocolate is sweet chocolate that also contains milk powder or condensed milk. In the UK and Ireland, milk chocolate must contain a minimum of 20% total dry cocoa solids; in the rest of the European Union, the minimum is 25%.[42]

White

White chocolate, although similar in texture to that of milk and dark chocolate, does not contain any cocoa solids that impart a dark color. In 2002, the US Food and Drug Administration established a standard for white chocolate as the «common or usual name of products made from cocoa fat (i.e., cocoa butter), milk solids, nutritive carbohydrate sweeteners, and other safe and suitable ingredients, but containing no nonfat cocoa solids».[45]

By application

Baking chocolate

Unsweetened baking chocolate

Baking chocolate, or cooking chocolate,[46] is chocolate intended to be used for baking and in sweet foods that may or may not be sweetened. Dark chocolate, milk chocolate, and white chocolate, are produced and marketed as baking chocolate. However, lower quality baking chocolate may not be as flavorful compared to higher-quality chocolate, and may have a different mouthfeel.[47]

Poorly tempered or untempered chocolate may have whitish spots on the dark chocolate part, called chocolate bloom; it is an indication that sugar or fat has separated due to poor storage. It is not toxic and can be safely consumed.[48]

Modeling chocolate

Modeling chocolate is a chocolate paste made by melting chocolate and combining it with corn syrup, glucose syrup, or golden syrup.[49]

Production

Chocolate is created from the cocoa bean. A cacao tree with fruit pods in various stages of ripening.

Roughly two-thirds of the entire world’s cocoa is produced in West Africa, with 43% sourced from Côte d’Ivoire,[50] where, as of 2007, child labor is a common practice to obtain the product.[51][52] According to the World Cocoa Foundation, in 2007 some 50 million people around the world depended on cocoa as a source of livelihood.[53] As of 2007 in the UK, most chocolatiers purchase their chocolate from them, to melt, mold and package to their own design.[54] According to the WCF’s 2012 report, the Ivory Coast is the largest producer of cocoa in the world.[55] The two main jobs associated with creating chocolate candy are chocolate makers and chocolatiers. Chocolate makers use harvested cocoa beans and other ingredients to produce couverture chocolate (covering). Chocolatiers use the finished couverture to make chocolate candies (bars, truffles, etc.).[56]

Production costs can be decreased by reducing cocoa solids content or by substituting cocoa butter with another fat. Cocoa growers object to allowing the resulting food to be called «chocolate», due to the risk of lower demand for their crops.[53]

Genome

The sequencing in 2010 of the genome of the cacao tree may allow yields to be improved.[57] Due to concerns about global warming effects on lowland climate in the narrow band of latitudes where cocoa is grown (20 degrees north and south of the equator), the commercial company Mars, Incorporated and the University of California, Berkeley, are conducting genomic research in 2017–18 to improve the survivability of cacao plants in hot climates.[58]

Cacao varieties

Chocolate is made from cocoa beans, the dried and fermented seeds of the cacao tree (Theobroma cacao), a small, 4–8 m tall (15–26 ft tall) evergreen tree native to the deep tropical region of the Americas. Recent genetic studies suggest the most common genotype of the plant originated in the Amazon basin and was gradually transported by humans throughout South and Central America. Early forms of another genotype have also been found in what is now Venezuela. The scientific name, Theobroma, means «food of the gods».[59] The fruit, called a cocoa pod, is ovoid, 15–30 cm (6–12 in) long and 8–10 cm (3–4 in) wide, ripening yellow to orange, and weighing about 500 g (1.1 lb) when ripe.

Cacao trees are small, understory trees that need rich, well-drained soils. They naturally grow within 20° of either side of the equator because they need about 2000 mm of rainfall a year, and temperatures in the range of 21 to 32 °C (70 to 90 °F). Cacao trees cannot tolerate a temperature lower than 15 °C (59 °F).[60]

The three main varieties of cocoa beans used in chocolate are criollo, forastero, and trinitario.

Processing

Cocoa pods are harvested by cutting them from the tree using a machete, or by knocking them off the tree using a stick. It is important to harvest the pods when they are fully ripe, because if the pod is unripe, the beans will have a low cocoa butter content, or low sugar content, reducing the ultimate flavor.

Microbial fermentation

The beans (which are sterile within their pods) and their surrounding pulp are removed from the pods and placed in piles or bins to ferment. Micro-organisms, present naturally in the environment, ferment the pectin-containing material. Yeasts produce ethanol, lactic acid bacteria produce lactic acid, and acetic acid bacteria produce acetic acid. In some cocoa-producing regions an association between filamentous fungi and bacteria (called «cocobiota») acts to produce metabolites beneficial to human health when consumed.[61] The fermentation process, which takes up to seven days, also produces several flavor precursors, that eventually provide the chocolate taste.[62]

After fermentation, the beans must be dried to prevent mold growth. Climate and weather permitting, this is done by spreading the beans out in the sun from five to seven days.[63] In some growing regions (for example, Tobago), the dried beans are then polished for sale by «dancing the cocoa»: spreading the beans onto a floor, adding oil or water, and shuffling the beans against each other using bare feet.[64]

The dried beans are then transported to a chocolate manufacturing facility. The beans are cleaned (removing twigs, stones, and other debris), roasted, and graded. Next, the shell of each bean is removed to extract the nib. The nibs are ground and liquefied, resulting in pure chocolate liquor.[65] The liquor can be further processed into cocoa solids and cocoa butter.[66]

Moist incubation

The beans are dried without fermentation. The nibs are removed and hydrated in an acidic solution. Then they are heated for 72 hours and dried again. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry showed that the incubated chocolate had higher levels of Strecker aldehydes, and lower levels of pyrazines.[67][68]

Blending

Chocolate liquor is blended with the cocoa butter in varying quantities to make different types of chocolate or couverture. The basic blends of ingredients for the various types of chocolate (in order of highest quantity of cocoa liquor first), are:

- Dark chocolate: sugar, cocoa butter, cocoa liquor, and (sometimes) vanilla

- Milk chocolate: sugar, cocoa butter, cocoa liquor, milk or milk powder, and vanilla

- White chocolate: sugar, cocoa butter, milk or milk powder, and vanilla

Usually, an emulsifying agent, such as soy lecithin, is added, though a few manufacturers prefer to exclude this ingredient for purity reasons and to remain GMO-free, sometimes at the cost of a perfectly smooth texture. Some manufacturers are now using PGPR, an artificial emulsifier derived from castor oil that allows them to reduce the amount of cocoa butter while maintaining the same mouthfeel.

The texture is also heavily influenced by processing, specifically conching (see below). The more expensive chocolate tends to be processed longer and thus has a smoother texture and mouthfeel, regardless of whether emulsifying agents are added.

Different manufacturers develop their own «signature» blends based on the above formulas, but varying proportions of the different constituents are used. The finest, plain dark chocolate couverture contains at least 70% cocoa (both solids and butter), whereas milk chocolate usually contains up to 50%. High-quality white chocolate couverture contains only about 35% cocoa butter.

Producers of high-quality, small-batch chocolate argue that mass production produces bad-quality chocolate.[69] Some mass-produced chocolate contains much less cocoa (as low as 7% in many cases), and fats other than cocoa butter. Vegetable oils and artificial vanilla flavor are often used in cheaper chocolate to mask poorly fermented and/or roasted beans.[69]

In 2007, the Chocolate Manufacturers Association in the United States, whose members include Hershey, Nestlé, and Archer Daniels Midland, lobbied the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to change the legal definition of chocolate to let them substitute partially hydrogenated vegetable oils for cocoa butter, in addition to using artificial sweeteners and milk substitutes.[70] Currently, the FDA does not allow a product to be referred to as «chocolate» if the product contains any of these ingredients.[71][72]

In the EU a product can be sold as chocolate if it contains up to 5% vegetable oil, and must be labeled as «family milk chocolate» rather than «milk chocolate» if it contains 20% milk.[73]

According to Canadian Food and Drug Regulations,[74] a «chocolate product» is a food product that is sourced from at least one «cocoa product» and contains at least one of the following: «chocolate, bittersweet chocolate, semi-sweet chocolate, dark chocolate, sweet chocolate, milk chocolate, or white chocolate». A «cocoa product» is defined as a food product that is sourced from cocoa beans and contains «cocoa nibs, cocoa liquor, cocoa mass, unsweetened chocolate, bitter chocolate, chocolate liquor, cocoa, low-fat cocoa, cocoa powder, or low-fat cocoa powder».

Conching

Chocolate melanger mixing raw ingredients

The penultimate process is called conching. A conche is a container filled with metal beads, which act as grinders. The refined and blended chocolate mass is kept in a liquid state by frictional heat. Chocolate before conching has an uneven and gritty texture. The conching process produces cocoa and sugar particles smaller than the tongue can detect (typically around 20 μm) and reduces rough edges, hence the smooth feel in the mouth. The length of the conching process determines the final smoothness and quality of the chocolate. High-quality chocolate is conched for about 72 hours, and lesser grades about four to six hours. After the process is complete, the chocolate mass is stored in tanks heated to about 45 to 50 °C (113 to 122 °F) until final processing.[75]

Tempering

Video of cocoa beans being ground and mixed with other ingredients to make chocolate at a Mayordomo store in Oaxaca

The final process is called tempering. Uncontrolled crystallization of cocoa butter typically results in crystals of varying size, some or all large enough to be seen with the naked eye. This causes the surface of the chocolate to appear mottled and matte, and causes the chocolate to crumble rather than snap when broken.[76][77] The uniform sheen and crisp bite of properly processed chocolate are the results of consistently small cocoa butter crystals produced by the tempering process.

The fats in cocoa butter can crystallize in six different forms (polymorphous crystallization).[76][78] The primary purpose of tempering is to assure that only the best form[clarification needed] is present. The six different crystal forms have different properties.

| Crystal | Melting temp. | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| I | 17 °C (63 °F) | Soft, crumbly, melts too easily |

| II | 21 °C (70 °F) | Soft, crumbly, melts too easily |

| III | 26 °C (79 °F) | Firm, poor snap, melts too easily |

| IV | 28 °C (82 °F) | Firm, good snap, melts too easily |

| V | 34 °C (93 °F) | Glossy, firm, best snap, melts near body temperature (37 °C) |

| VI | 36 °C (97 °F) | Hard, takes weeks to form |

Molten chocolate and a piece of a chocolate bar

As a solid piece of chocolate, the cocoa butter fat particles are in a crystalline rigid structure that gives the chocolate its solid appearance. Once heated, the crystals of the polymorphic cocoa butter can break apart from the rigid structure and allow the chocolate to obtain a more fluid consistency as the temperature increases – the melting process. When the heat is removed, the cocoa butter crystals become rigid again and come closer together, allowing the chocolate to solidify.[79]

The temperature in which the crystals obtain enough energy to break apart from their rigid conformation would depend on the milk fat content in the chocolate and the shape of the fat molecules, as well as the form of the cocoa butterfat. Chocolate with a higher fat content will melt at a lower temperature.[80]

Making chocolate considered «good» is about forming as many type V crystals as possible. This provides the best appearance and texture and creates the most stable crystals, so the texture and appearance will not degrade over time. To accomplish this, the temperature is carefully manipulated during the crystallization.

Chocolate cubes, pistoles and callets

Generally, the chocolate is first heated to 45 °C (113 °F) to melt all six forms of crystals.[76][78] Next, the chocolate is cooled to about 27 °C (81 °F), which will allow crystal types IV and V to form. At this temperature, the chocolate is agitated to create many small crystal «seeds» which will serve as nuclei to create small crystals in the chocolate. The chocolate is then heated to about 31 °C (88 °F) to eliminate any type IV crystals, leaving just type V. After this point, any excessive heating of the chocolate will destroy the temper and this process will have to be repeated. Other methods of chocolate tempering are used as well. The most common variant is introducing already tempered, solid «seed» chocolate. The temper of chocolate can be measured with a chocolate temper meter to ensure accuracy and consistency. A sample cup is filled with the chocolate and placed in the unit which then displays or prints the results.

Two classic ways of manually tempering chocolate are:

- Working the molten chocolate on a heat-absorbing surface, such as a stone slab, until thickening indicates the presence of sufficient crystal «seeds»; the chocolate is then gently warmed to working temperature.

- Stirring solid chocolate into molten chocolate to «inoculate» the liquid chocolate with crystals (this method uses the already formed crystals of the solid chocolate to «seed» the molten chocolate).

Chocolate tempering machines (or temperers) with computer controls can be used for producing consistently tempered chocolate. In particular, continuous tempering machines are used in large volume applications. Various methods and apparatuses for continuous flow tempering. In general, molten chocolate coming in at 40–50 °C is cooled in heat exchangers to crystallization temperates of about 26–30 °C, passed through a tempering column consisting of spinning plates to induce shear, then warmed slightly to re-melt undesirable crystal formations.

Shaping

Chocolate is molded in different shapes for different uses:[81]

A machine turns chocolate bars into a thin liquid chocolate waterfall as a coconut bar sits on a conveyor belt waiting to pass through. This photo was taken at a Li-Lac Chocolates facility in Industry City Brooklyn New York.

- Chocolate bars (tablets) are rectangular blocks of chocolate meant to be broken down to cubes (or other predefined shapes), which can then be used for consumption, cooking and baking. The term is also used for combination bars, which are a type of candy bars

- Chocolate chips are small pieces of chocolate, usually drop-like, which are meant for decoration and baking

- Pistoles, callets and fèves are small, coin-like or bean-like pieces of chocolate meant for baking and patisserie applications (also see Pistole (coin) and Fève (trinket))

- Chocolate blocks are large, cuboid chunks of chocolate meant for professional use and further processing

- Other, more specialized shapes for chocolate include sticks, curls and hollow semi-spheres

Storage

Chocolate is very sensitive to temperature and humidity. Ideal storage temperatures are between 15 and 17 °C (59 and 63 °F), with a relative humidity of less than 50%. If refrigerated or frozen without containment, chocolate can absorb enough moisture to cause a whitish discoloration, the result of fat or sugar crystals rising to the surface. Various types of «blooming» effects can occur if chocolate is stored or served improperly.[82]

Chocolate bloom is caused by storage temperature fluctuating or exceeding 24 °C (75 °F), while sugar bloom is caused by temperature below 15 °C (59 °F) or excess humidity. To distinguish between different types of bloom, one can rub the surface of the chocolate lightly, and if the bloom disappears, it is fat bloom. Moving chocolate between temperature extremes, can result in an oily texture. Although visually unappealing, chocolate suffering from bloom is safe for consumption and taste unaffected.[83][84][85] Bloom can be reversed by retempering the chocolate or using it for any use that requires melting the chocolate.[86]

Chocolate is generally stored away from other foods, as it can absorb different aromas. Ideally, chocolates are packed or wrapped, and placed in proper storage with the correct humidity and temperature. Additionally, chocolate is frequently stored in a dark place or protected from light by wrapping paper. The glossy shine, snap, aroma, texture, and taste of the chocolate can show the quality and if it was stored well.[87]

Composition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 2,240 kJ (540 kcal) |

|

Carbohydrates |

59.4 |

| Sugars | 51.5 g |

| Dietary fiber | 3.4 g |

|

Fat |

29.7 |

|

Protein |

7.6 g |

| Vitamins | Quantity

%DV† |

| Vitamin A | 195 IU |

| Thiamine (B1) |

9% 0.1 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

25% 0.3 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

3% 0.4 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

0% 0.0 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

3% 11 μg |

| Vitamin B12 |

29% 0.7 μg |

| Choline |

9% 46.1 mg |

| Vitamin C |

0% 0 mg |

| Vitamin E |

3% 0.5 mg |

| Vitamin K |

5% 5.7 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity

%DV† |

| Calcium |

19% 189 mg |

| Iron |

18% 2.4 mg |

| Magnesium |

18% 63 mg |

| Manganese |

24% 0.5 mg |

| Phosphorus |

30% 208 mg |

| Potassium |

8% 372 mg |

| Selenium |

6% 4.5 μg |

| Sodium |

5% 79 mg |

| Zinc |

24% 2.3 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 1.5 g |

| Caffeine | 20 mg |

| Cholesterol | 23 mg |

| Theobromine | 205 mg |

|

Link to USDA Database entry |

|

|

|

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central |

Nutrition

One hundred grams of milk chocolate supplies 540 calories. It is 59% carbohydrates (52% as sugar and 3% as dietary fiber), 30% fat and 8% protein (table). Approximately 65% of the fat in milk chocolate is saturated, mainly palmitic acid and stearic acid, while the predominant unsaturated fat is oleic acid (table).

100-grams of milk chocolate is an excellent source (over 19% of the Daily Value, DV) of riboflavin, vitamin B12 and the dietary minerals, manganese, phosphorus and zinc. Chocolate is a good source (10–19% DV) of calcium, magnesium and iron.

Effects on health

Chocolate may be a factor for heartburn in some people because one of its constituents, theobromine, may affect the esophageal sphincter muscle in a way that permits stomach acids to enter the esophagus.[88] Theobromine poisoning is an overdosage reaction to the bitter alkaloid, which happens more frequently in domestic animals than humans. However, daily intake of 50–100 g cocoa (0.8–1.5 g theobromine) by humans has been associated with sweating, trembling and severe headache.[89] Chocolate contains alkaloids such as theobromine and phenethylamine, which have physiological effects in humans, but the presence of theobromine renders it toxic to some animals, including dogs and cats.[90]

According to a 2005 study, the average lead concentration of cocoa beans is ≤ 0.5 ng/g, which is one of the lowest reported values for a natural food.[91] However, during cultivation and production, chocolate may absorb lead from the environment (such as in atmospheric emissions of leaded gasoline, which is still being used in Nigeria).[91] Reports from 2014 indicate that «chocolate might be a significant source» of lead ingestion for children if consumption is high (with dark chocolate containing higher amounts),[92][93] and «one 10 g cube of dark chocolate may contain as much as 20% of the daily lead oral limit.»[92]

Chocolate and cocoa contain moderate to high amounts of oxalate,[94][95] which may increase the risk of kidney stones.[96]

A few studies have documented allergic reactions from chocolate in children.[88] Other research has shown that dark chocolate can aggravate acne in men who are prone to it.[97] Research has also shown that consuming dark chocolate does not substantially affect blood pressure.[44] Chocolate and cocoa are under preliminary research to determine if consumption affects the risk of certain cardiovascular diseases[98] or cognitive abilities.[99]

One tablespoonful (5 grams) of dry unsweetened cocoa powder has 12.1 mg of caffeine[100] and a 25-g single serving of dark chocolate has 22.4 mg of caffeine.[101] Although a single 7 oz. (200 ml) serving of coffee may contain 80–175 mg,[102] studies have shown psychoactive effects in caffeine doses as low as 9 mg,[103] and a dose as low as 12.5 mg was shown to have effects on cognitive performance.[104]

Phytochemicals

Cocoa solids are a source of flavonoids[105] and alkaloids, such as theobromine, phenethylamine, and caffeine.[106]

Labeling

Some manufacturers provide the percentage of chocolate in a finished chocolate confection as a label quoting percentage of «cocoa» or «cacao». This refers to the combined percentage of both cocoa solids and cocoa butter in the bar, not just the percentage of cocoa solids.[107] The Belgian AMBAO certification mark indicates that no non-cocoa vegetable fats have been used in making the chocolate.[108][109] A long-standing dispute between Britain on the one hand and Belgium and France over British use of vegetable fats in chocolate ended in 2000 with the adoption of new standards which permitted the use of up to five percent vegetable fats in clearly labelled products.[110] This British style of chocolate has sometimes been pejoratively referred to as «vegelate».[110]

Chocolates that are organic[111] or fair trade certified[112] carry labels accordingly.

In the United States, some large chocolate manufacturers lobbied the federal government to permit confections containing cheaper hydrogenated vegetable oil in place of cocoa butter to be sold as «chocolate». In June 2007, in response to consumer concern about the proposal, the FDA reiterated «Cacao fat, as one of the signature characteristics of the product, will remain a principal component of standardized chocolate.»[113]

Industry

Chocolate, prevalent throughout the world, is a steadily growing, US$50 billion-a-year worldwide business.[114] Europe accounts for 45% of the world’s chocolate revenue,[115] and the US spent $20 billion in 2013.[116] Big Chocolate is the grouping of major international chocolate companies in Europe and the U.S. U.S. companies Mars and Hershey’s alone generated $13 billion a year in chocolate sales and account for two-thirds of U.S. production in 2004.[117] Despite the expanding reach of the chocolate industry internationally, cocoa farmers and labourers in the Ivory Coast are unaware of the uses of the beans; the high cost of chocolate products in the Ivory Coast make it inaccessible to the majority of the population, who do not know what it tastes like.[118]

Manufacturers

Chocolate with various fillings

Chocolate manufacturers produce a range of products from chocolate bars to fudge. Large manufacturers of chocolate products include Cadbury (the world’s largest confectionery manufacturer), Ferrero, Guylian, The Hershey Company, Lindt & Sprüngli, Mars, Incorporated, Milka, Neuhaus and Suchard.

Guylian is best known for its chocolate sea shells; Cadbury for its Dairy Milk and Creme Egg. The Hershey Company, the largest chocolate manufacturer in North America, produces the Hershey Bar and Hershey’s Kisses.[119] Mars Incorporated, a large privately owned U.S. corporation, produces Mars Bar, Milky Way, M&M’s, Twix, and Snickers. Lindt is known for its truffle balls and gold foil-wrapped Easter bunnies.

Food conglomerates Nestlé SA and Kraft Foods both have chocolate brands. Nestlé acquired Rowntree’s in 1988 and now markets chocolates under their brand, including Smarties (a chocolate candy) and Kit Kat (a chocolate bar); Kraft Foods through its 1990 acquisition of Jacobs Suchard, now owns Milka and Suchard. In February 2010, Kraft also acquired British-based Cadbury;[120] Fry’s, Trebor Basset and the fair trade brand Green & Black’s also belongs to the group.

Child labor in cocoa harvesting

The widespread use of children in cocoa production is controversial, not only for the concerns about child labor and exploitation, but also because up to 12,000 of the 200,000 children working in the Ivory Coast, the world’s biggest producer of cocoa,[121] may be victims of trafficking or slavery.[122] Most attention on this subject has focused on West Africa, which collectively supplies 69 percent of the world’s cocoa,[123] and the Ivory Coast in particular, which supplies 35 percent of the world’s cocoa.[123] Thirty percent of children under age 15 in sub-Saharan Africa are child laborers, mostly in agricultural activities including cocoa farming.[124] Major chocolate producers, such as Nestlé, buy cocoa at commodities exchanges where Ivorian cocoa is mixed with other cocoa.[125]

In 2009, Salvation Army International Development (SAID) UK stated that 12,000 children have been trafficked on cocoa farms in the Ivory Coast of Africa, where half of the world’s chocolate is made.[126] SAID UK states that it is these child slaves who are likely to be working in «harsh and abusive»[127] conditions for the production of chocolate,[126] and an increasing number of health-food[128] and anti-slavery[129] organisations are highlighting and campaigning against the use of trafficking in the chocolate industry.

As of 2017, approximately 2.1 million children in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire were involved in farming cocoa, carrying heavy loads, clearing forests, and being exposed to pesticides.[5] According to Sona Ebai, the former secretary-general of the Alliance of Cocoa Producing Countries: «I think child labor cannot be just the responsibility of industry to solve. I think it’s the proverbial all-hands-on-deck: government, civil society, the private sector. And there, you need leadership.»[122] Reported in 2018, a 3-year pilot program – conducted by Nestlé with 26,000 farmers mostly located in Côte d’Ivoire – observed a 51% decrease in the number of children doing hazardous jobs in cocoa farming.[4] The US Department of Labor formed the Child Labor Cocoa Coordinating Group as a public-private partnership with the governments of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire to address child labor practices in the cocoa industry.[130] The International Cocoa Initiative involving major cocoa manufacturers established the Child Labor Monitoring and Remediation System intended to monitor thousands of farms in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire for child labor conditions,[4][5] but the program reached less than 20% of the child laborers.[131] Despite these efforts, goals to reduce child labor in West Africa by 70% before 2020 are frustrated by persistent poverty, absence of schools, expansion of cocoa farmland, and increased demand for cocoa.[4][132]

In April 2018, the Cocoa Barometer report stated: «Not a single company or government is anywhere near reaching the sector-wide objective of the elimination of child labor, and not even near their commitments of a 70% reduction of child labor by 2020».[132]

Fair trade

In the 2000s, some chocolate producers began to engage in fair trade initiatives, to address concerns about the marginalization of cocoa laborers in developing countries. Traditionally, Africa and other developing countries received low prices for their exported commodities such as cocoa, which caused poverty to abound. Fairtrade seeks to establish a system of direct trade from developing countries to counteract this unfair system.[133] One solution for fair labor practices is for farmers to become part of an Agricultural cooperative. Cooperatives pay farmers a fair price for their cocoa so farmers have enough money for food, clothes, and school fees.[134] One of the main tenets of fair trade is that farmers receive a fair price, but this does not mean that the larger amount of money paid for fair trade cocoa goes directly to the farmers. The effectiveness of fair trade has been questioned. In a 2014 article, The Economist stated that workers on fair trade farms have a lower standard of living than on similar farms outside the fair trade system.[135]

Usage and consumption

Bars

Chocolate is sold in chocolate bars, which come in dark chocolate, milk chocolate and white chocolate varieties. Some bars that are mostly chocolate have other ingredients blended into the chocolate, such as nuts, raisins, or crisped rice. Chocolate is used as an ingredient in a huge variety of bars, which typically contain various confectionary ingredients (e.g., nougat, wafers, caramel, nuts, etc.) which are coated in chocolate.

Coating and filling

Chocolate cake with chocolate frosting

Chocolate is used as a flavouring product in many desserts, such as chocolate cakes, chocolate brownies, chocolate mousse and chocolate chip cookies. Numerous types of candy and snacks contain chocolate, either as a filling (e.g., M&M’s) or as a coating (e.g., chocolate-coated raisins or chocolate-coated peanuts).

Beverages

Some non-alcoholic beverages contain chocolate, such as chocolate milk, hot chocolate, chocolate milkshakes and tejate. Some alcoholic liqueurs are flavoured with chocolate, such as chocolate liqueur and creme de cacao. Chocolate is a popular flavour of ice cream and pudding, and chocolate sauce is a commonly added as a topping on ice cream sundaes. The caffè mocha is an espresso beverage containing chocolate.

Popular culture

Religious and cultural links

Chocolate is associated with festivals such as Easter, when moulded chocolate rabbits and eggs are traditionally given in Christian communities, and Hanukkah, when chocolate coins are given in Jewish communities. Chocolate hearts and chocolate in heart-shaped boxes are popular on Valentine’s Day and are often presented along with flowers and a greeting card. In 1868, Cadbury created a decorated box of chocolates in the shape of a heart for Valentine’s Day.[31][136] Boxes of filled chocolates quickly became associated with the holiday.[31] Chocolate is an acceptable gift on other holidays and on occasions such as birthdays.

Many confectioners make holiday-specific chocolate candies. Chocolate Easter eggs or rabbits and Santa Claus figures are two examples. Such confections can be solid, hollow, or filled with sweets or fondant.

Books and film

Chocolate has been the center of several successful book and film adaptations.

In 1964, Roald Dahl published a children’s novel titled Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The novel centers on a poor boy named Charlie Bucket who takes a tour through the greatest chocolate factory in the world, owned by the eccentric Willy Wonka.[137] Two film adaptations of the novel were produced: Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971) and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005). A third adaptation, an origin prequel film titled Wonka, is scheduled for release in 2023.[138]

Like Water for Chocolate a 1989 love story by novelist Laura Esquivel, was adapted to film in 1992. Chocolat, a 1999 novel by Joanne Harris, was adapted for film in Chocolat which was released a year later.[139]

See also

- Candida krusei

- Candy making

- Children in cocoa production

- Chocolataire

- Chocolate almonds

- Chocolate chip

- Chocoholic

- Cuestión moral: si el chocolate quebranta el ayuno eclesiástico

- List of chocolate-covered foods

- List of chocolate beverages

- List of chocolate companies

- Theobroma cacao, the cocoa/chocolate plant

- United States military chocolate

- Types of chocolate

References

- ^ a b c Powis, Terry G.; Cyphers, Ann; Gaikwad, Nilesh W.; Grivetti, Louis; Cheong, Kong (24 May 2011). «Cacao use and the San Lorenzo Olmec». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (21): 8595–8600. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.8595P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1100620108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3102397. PMID 21555564.

- ^ «Consumían olmecas chocolate hace 3000 años». El Universal. Mexico City. 29 July 2008. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ «Chocolate: A Mesoamerican Luxury 1200–1521 – Obtaining Cacao». Field Museum. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Oliver Balch (20 June 2018). «Child labour: the true cost of chocolate production». Raconteur. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Kieran Guilbert (12 June 2017). «Falling cocoa prices threaten child labor spike in Ghana, Ivory Coast». Reuters. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ a b Terry G. Powis; W. Jeffrey Hurst; María del Carmen Rodríguez; Ponciano Ortíz C.; Michael Blake; David Cheetham; Michael D. Coe; John G. Hodgson (December 2007). «Oldest chocolate in the New World». Antiquity. 81 (314). ISSN 0003-598X. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Watson, Traci (22 January 2013). «Earliest Evidence of Chocolate in North America». Science. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ «New Chemical Analyses Take Confirmation Back 500 Years and Reveal that the Impetus for Cacao Cultivation was an Alcoholic Beverage». Penn Museum. 2007. Archived from the original on 2 December 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- ^ a b Burleigh, Robert (2002). Chocolate: Riches from the Rainforest. Harry N. Abrams, Ins., Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8109-5734-3.

- ^ «Chocolate: A Mesoamerican Luxury 250–900 C.E. (A.D.) – Using Chocolate». Field Museum. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ «Chocolate: A Mesoamerican Luxury 250–900 C.E. (A.D.) – Obtaining Cacao». Field Museum. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ «Chocolate: A Mesoamerican Luxury 250–900 C.E. (A.D.) – Making Chocolate». Field Museum. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j «History of Chocolate». Field Museum. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ «Aztecs and Cacao: the bittersweet past of chocolate». The Daily Telegraph. 15 September 2009. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ Peniche Rivero, Piedad (1990). «When cocoa was used as currency – pre-Columbian America – The Fortunes of Money». UNESCO Courier. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2008.