Content

- Origin of the word chocolate

- From Amerindian languages to Spanish

- Timeline of the word chocolate

- The current use and meaning of the word chocolate

- Lexical family of the word chocolate

- Incorporation of the word chocolate into other languages

- References

Have you ever wondered where the word chocolate comes from? The name of this product has a long history that you can understand below. A considerable number of words from the indigenous languages of the American continent passed into Spanish and, through Spanish, many times into other European languages.

When the Spanish conquerors arrived on the American continent, they found a great number of plants, animals and natural and cultural products previously unknown to them and to which, obviously, it was necessary to give names. These names were normally taken from the languages spoken by the inhabitants of those areas.

The Spanish conquerors learned about chocolate (more precisely, cacao) through the Aztecs, who, in turn, learned the secrets of its elaboration from the ancient Mayan civilization, who received it from the Olmecs.

The three peoples consumed it in the form of a drink. The pre-Columbian inhabitants of Mexico prepared xocolatl (“xocol”: bitter and “atl”: water) from cacahuatl (cocoa) by adding cold water and mixing vigorously.

The liquid was then poured into a container creating the foam, which was considered the most refined feature of the entire sensory experience.

Christopher Columbus brought cacao almonds to Europe as a curiosity, but it was Hernán Cortés who first realized their possible commercial value. Spain was the first European country to use and commercialize cocoa, having monopolized it for many years.

Origin of the word chocolate

From Amerindian languages to Spanish

It is known that chocolate comes from the American continent, and that the word was not known in Europe before the discovery of the Spanish empire. The main Amerindian languages that contributed lexical elements to Spanish are the following:

- Nahuatl, the language of the Aztec empire. From this language, words (in addition to chocolate) such as tomato, avocado, peanut (peanut in Mexico), gum, coyote, ocelot, buzzard, tamale, and many others have passed into Spanish.

- Quechua, the language of the Inca empire. From Quechua, words like vicuña, guanaco, condor, puma, potato, potato, mate, pampa, etc. come.

Of these two languages, Nahuatl is more present in Spanish, since it was the most widespread language of the Aztec empire, which included Mexico and much of Central America and was used as a general language throughout the empire.

Timeline of the word chocolate

The indigenous people who inhabited the American continent used cocoa as ingredients for food and drinks, as well as the seeds as coins. Cocoa in Spain also occupied the role of food and currency, but the word chocolate began to dominate in the semantic world related to food and beverages.

At the end of the 16th century to the middle of the 17th century, the word chocolate is seen in popular works in Europe, but not yet as a word in common use. Before that, the Nahuatl language continued to be used to define many kinds of drinks that were made with cocoa.

During the end of the 17th century and until the beginning of the 19th century, the word chocolate began to be used by Europeans for various foods and drinks. The word chocolate appears in the dictionary of the Spanish Royal Academy only in the year 1590 according to the book «Natural and Moral History of the Indies» by José de Acosta.

This word is a lexical indigenism incorporated into Spanish due to the need to name the unknown elements of the new continent (the American continent). Indigenisms are the voices that come from pre-Columbian languages that arrived in Spanish after an adaptation to the language.

The current use and meaning of the word chocolate

Although there is more certainty of the origin of the word cocoa, it is not so much with the word chocolate. This word has many hypotheses and some very different from each other.

The only data that coincides with all the theories, hypotheses and assumptions is that «chocolate» is the derivation of the languages of the inhabitants of Mexico from the pre-Columbian period.

Today, the word chocolate is used to name any product that contains cocoa. This is due to the great importance that cocoa had in the economy of the colonial era due to its trade thanks to Hernán Cortés.

Currently, the study of the origin and chronology of incorporation into the Spanish language of the word chocolate (as well as the source of its structural changes in form and meaning) is discussed.

The dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy defines the word chocolate as follows:«Pasta made with ground cocoa and sugar, to which cinnamon or vanilla is generally added.»

Therefore, the word chocolate, derives from languages of Central America and was adapted over time by the Spanish to their own linguistic system, which was later incorporated into many other languages or languages.

Lexical family of the word chocolate

The lexical family or word family is a set of words that share the same root. Thus, from the word chocolate, the root is «chocolat» and its family of words or derivatives are:

- Chocolatera: Container where the chocolate is served or prepared.

- Chocolatería: Place where chocolate is manufactured or sold.

- Chocolatier: Person who prepares or sells chocolate.

- Chocolate bar: Chocolate candy.

These words are the union of a root and at least one derivative element, which can be a suffix or a prefix. The ways of forming the listed words follow the procedures of the Spanish language system. In all cases, these are derived by suffixation.

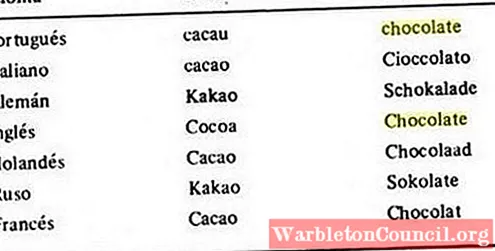

Incorporation of the word chocolate into other languages

From the Amerindian languages to Spanish the word chocolate derived. This, in turn, was incorporated into several different types of languages:

- German: Schokolade

- Danish: Chokolade

- French: Chocolat

- Dutch: Chocolade

- Indonesian: Coklat

- Italian: Cioccolato

- Polish: Czekolada

- Swedish: Choklad

The word chocolate was incorporated into many other languages. In both the English and Portuguese languages, the word is spelled the same, but of course, its pronunciation varies according to the tune of the language.

References

- Coe, S. & Coe, M. (2013). The True History of Chocolate. London, United Kingdom: Thames and Hudson.

- American Heritage. (2007). Spanish Word Histories and Mysteries: English Words That Come From Spanish. Boston, United States: American Heritage Dictionaries.

- Hualde, J. & Olarrea, A. & Escobar, A. (2002). Introduction to Hispanic Linguistics. Cambridge, United Kingdom: CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS.

- López and López, M .. (2010). THE CHOCOLATE. ITS ORIGIN, ITS MANUFACTURING AND ITS UTILITY: SCRIPTIVE MEMORY OF THE FIRST CHOCOLATE FACTORY OF THE ESCORIAL. California, United States: MAXTOR.

- Clarke, W. Tresper. Sidelights in the history of cacao and chocolate. Brooklyn, N.Y., Rockwood and Co. 1953 8 pp. See Intern. Choc. Rev. 8 (7): 179-183. July 1953.

- Walter Baker & CO. The chocolate plant (Theobroma cacao) and its products. Dorchester, Mass., U.S.A., 1891. 40 pp.

- Hernández Triviño, Ascensión. (2013). Chocolate: history of a Nahuatlism.Nahuatl culture studies, 46, 37-87. Retrieved on March 31, 2017, from scielo.org.mx.

Do We Know Where The Word ‘Chocolate’ Comes From?

Whenever we hear the word ‘chocolate’, we instantly start imagining this popular delicacy. Actually, we imagine eating the bars and buying the biggest packages of our favorite sweet in the supermarkets. But, does anyone wonder where the chocolate word comes from? What exactly do we know about it? After all, chocolate is our favorite food for centuries. In most cases, we don’t know anything about the most popular dainty. But here is a short and amusing story about our beloved sweet, the one that’s our best friend in both, happy and sad moments, and the one that witnesses our tears and our exclamations of rejoicing.

A Long History – Our Ancestors Really Knew How To Enjoy

One thing is for sure, our forebears treated themselves with chocolate many centuries ago and according to studies, chocolate has been around us for more than 2000 years. However, the word ‘chocolate’ has been used to refer to a beverage made from the

seeds of a cacao tree, and not a delicacy in a solid form. It was a bitter drink, but at the same time very popular and cherished. From the start, chocolate was a beverage consumed by the rich, at least in Europe, where it appeared sometime around the 17th century. When they first consumed it, Europeans (Spanish in the first case) called it ‘a beverage for pigs’, but they soon started mixing it with honey and sugar, and in a blink of an eye, chocolate gained incredible popularity throughout the whole Old Continent.

What About The History Of The Word Itself?

There are many stories about the history of the word ‘chocolate’, but etymologists believe that the word itself comes from the Aztec word ‘xocoatl’. Of course, Aztecs considered ‘xocoatl’ to mean ‘a bitter cacao bean beverage’. At the time of Mayas and Aztecs, chocolate was believed to have magical powers, and it was even used in some of the most sacred rituals. The value of the chocolate at that particular time can be seen through the fact that cacao beans had the value of a currency. One could easily trade 100 cacao beans for a good turkey. Well, the same would be true even today, right? Nothing can comfort us more than a fresh chocolate truffle. We would surely trade all the money from our wallet just to get our favorite chocolate product.

When it comes to other ancient languages, in Latin the word for the most important chocolate ingredient – cacao tree — is Theobroma cacao. It means ‘food of the gods’. This also shows how significant ‘chocolate’ was in past times.

According to Oxford English Dictionary, the English word for ‘chocolate’ comes from the whole another language, Nahuatl. Its word ‘chocolatl’ was also meant as a drink made of many ingredients, but mostly including cacao beans.

Hence, the word for our most delicious sweet was similar in many ancient languages, and it remained so even in present day. No wonder how after all these millennia and centuries chocolate remained a favorite food of a mankind.

19th Century Brought Us The Most Precious Food — Solid Eating Chocolate

1828 was the year of creating

cocoa powder and solid chocolate. The man to ‘blame’ for this god-given invention was a Dutch chemist. Namely, he found a way to make powdered chocolate by eliminating almost half of the natural fat from the chocolate seed. The idea behind his discovery was to make an easy to mix chocolate drink. He crushed the cacao seeds and then pressed the cacao as well as treated it with alkaline salts. His product soon led to solid chocolate creations made from the cacao and cocoa powder. Credits for the first real chocolate bar go to Joseph Fry In England, a man whom many of us thank on a daily basis.

Therefore, the word ‘chocolate’ has undergone many phases in its history, from being used for an expensive cacao drink, to including a range of different affordable sweets, with sugar and additives and less cacao in them. No matter what are its ingredients, chocolate never stopped being consumed. And hopefully, it seems it never will.

«Traités nouveaux & curieux du café du thé et du chocolate», by Philippe Sylvestre Dufour, 1685.

The history of chocolate began in Mesoamerica. Fermented beverages made from chocolate date back to at least 1900 BC to 1500 BC.[1] The Mexica believed that cacao seeds were the gift of Quetzalcoatl, the god of wisdom, and the seeds once had so much value that they were used as a form of currency.[2] Originally prepared only as a drink, chocolate was served as a bitter liquid, mixed with spices or corn puree. It was believed to be an aphrodisiac and to give the drinker strength. Today, such drinks are also known as «Chilate» and are made by locals in the south of Mexico and the north triangle of Central America (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras).

After its arrival to Europe in the sixteenth century, sugar was added to it and it became popular throughout society, first among the ruling classes and then among the common people. In the 20th century, chocolate was considered essential in the rations of United States soldiers during war.[3]

The word «chocolate» comes from the Classical Nahuatl word xocolātl, of uncertain etymology, and entered the English language via the Spanish language.

History[edit]

An Aztec woman generates foam by pouring chocolate from one vessel to another in the Codex Tudela

Cultivation, consumption, and cultural use of cacao were extensive in Mesoamerica where the cacao tree is native.[4] When pollinated, the seed of the cacao tree eventually forms a kind of sheath, or ear, averaging 20″ long, hanging from the tree trunk itself. Within the sheath are 30 to 40 brownish-red almond-shaped beans embedded in a sweet viscous pulp. While the beans themselves are bitter due to the alkaloids within them, the sweet pulp may have been the first element consumed by humans.

Cacao pods grow in a wide range of colors, from pale yellow to bright green, all the way to dark purple or crimson. The skin can also vary greatly — some are sculpted with craters or warts, while others are completely smooth. This wide range in type of pods is unique to cacaos in that their color and texture does not necessarily determine the ripeness or taste of the beans inside.[5]

Evidence suggests that it may have been fermented and served as an alcoholic beverage as early as 1400 BC.[6]

Cultivation of the cacao was not an easy process. Part of this was because cacao trees in their natural environment grow to 60 feet tall or more. When the trees were grown on a plantation, however, they grew to around 20 feet tall.

While researchers do not agree on which Mesoamerican culture first domesticated the cacao tree, the use of the fermented bean in a drink seems to have arisen in North America (Mesoamerica—Central America and Mexico). Scientists have been able to confirm its presence in vessels throughout the region by evaluating the «chemical footprint» detectable in the micro samples of contents that remain.[1] Ceramic vessels with residues from the preparation of chocolate beverages have been found at archaeological sites dating back to the Early Formative (1900–900 BC) period. For example, one such vessel found at an Olmec archaeological site on the Gulf Coast of Veracruz, Mexico dates chocolate’s preparation by pre-Olmec peoples as early as 1750 BC.[7] On the Pacific coast of Chiapas, Mexico, a Mokayanan archaeological site provides evidence of cacao beverages dating even earlier, to 1900 BC.[7]

A study, published online in Nature Ecology and Evolution, suggests that cacao—the plant from which chocolate is made—was domesticated, or grown by people for food, around 1,500 years earlier than previously thought. In addition, the researchers found cacao was originally domesticated in South America, rather than in Central America. “This new study shows us that people in the upper reaches of the Amazon basin, extending up into the foothills of the Andes in southeastern Ecuador, where harvesting and consuming cacao that appears to be a close relative of the type of cacao later used in Mexico—and they were doing this 1,500 years earlier,” said Michael Blake, study co-author and professor in the University of British Columbia department of anthropology. The researchers used three lines of evidence to show that the Mayo-Chinchipe culture used cacao between 5,300 and 2,100 years ago: the presence of starch grains specific to the cacao tree inside ceramic vessels and broken pieces of pottery; residues of theobromine, a bitter alkaloid found in the cacao tree but not its wild relatives; and fragments of ancient DNA with sequences unique to the cacao tree.[8]

Pueblo people, who lived in an area now the U.S. Southwest, imported cacao from Mesoamerican cultures in southern Mexico between 900 and 1400. They used it as a common beverage consumed by many people within their society.[1]

Archaeological evidence of Cacao in Mesoamerica[edit]

Nature Ecology and Evolution reported what is believed to be the earliest cacao use from approximately 5,300 years ago recovered from the Santa Ana (La Florida) site in southeast Ecuador.[9] Another find of chemically traced cacao was in 1984 when a team of archaeologists in Guatemala explored the Mayan site of Río Azul. They discovered fifteen vessels surrounding male skeletons in the royal tomb. One of these vessels was beautifully decorated and covered in various Mayan glyphs. One of these glyphs translated to «kaka», also known as cacao. The inside of the vessel was lined with a dark-colored powder, which was scraped off for further testing. When the archaeologists took this powder to the Hershey Center for Health and Nutrition to be tested[citation needed], they found trace amounts of theobromine in the powder, a major indicator of cacao. This cacao was dated to sometime between 460 and 480 AD [10]

Cacao powder was also found in decorated bowls and jars, known as teammates, in the city of Puerto Escondido. Once thought to have been a scarce commodity, cacao was found in many more teammates than once thought. However, since this powder was only found in bowls of higher quality, it led archaeologists to believe that only wealthier people could afford such bowls, and therefore the cacao. The cacao teammates are believed to have been a centerpiece to social gatherings between people of high social status.[10]

Olmec use[edit]

Earliest evidence of domestication of the cacao plant dates to the Olmec culture from the Preclassic period.[11] The Olmecs used it for religious rituals or as a medicinal drink, with no recipes for personal use. Little evidence remains of how the beverage was processed.

Mayan use[edit]

The Mayans (in Guatemala) produced writings about cacao that confirmed the identification of the drink with the gods. The Dresden Codex specifies that it is the food of the rain deity Chaac, and the Madrid Codex says that gods shed their blood on the cacao pods as part of its production.[12] The Maya people gathered once a year to give thanks to the god Ek Chuah who they saw as the Cacao god.[13] The consumption of the chocolate drink is also depicted on pre-Hispanic vases. The Maya seasoned their chocolate by mixing the roasted cacao seed paste into a drink with water, chile peppers, and cornmeal, transferring the mixture repeatedly between pots until the top was covered with a thick foam, or «head», similar to that found on beer.[3]

There were many uses for cacao among the Maya. It was used in official ceremonies and religious rituals, at feasts and festivals, as funerary offerings, as tribute, and for medicinal purposes. Both cacao itself and vessels and instruments used for the preparation and serving of cacao were used for important gifts and tributes.[14] Cacao beans were used as currency, to buy anything from avocados to turkeys to sex. A rabbit, for example, was worth ten cacao beans, (called “almonds” by the early sixteenth-century chronicler Francisco Oviedo y Valdés), a slave about a hundred, and the services of a prostitute, eight to ten “according to how they agree”.[11] The beans were also used in betrothal and marriage ceremonies among the Maya, especially among the upper classes.

“The form of the marriage is: the bride gives the bridegroom a small stool painted in colors, and also gives him five grains of cacao, and says to him “These I give thee as a sign that I accept thee as my husband.” And he also gives her some new skirts and another five grains of cacao, saying the same thing.”[11]

Maya’s preparation of cacao started with cutting open cacao pods to expose the beans and the fleshy pulp. The beans were left out to ferment for a few days. In some cases, the beans were also roasted over an open fire to add a smoky flavor. The beans then had their husks removed and ground into a paste. Since sweeteners were rarely used by Maya, the cacao paste was flavored with additives like flowers, vanilla pods, and chilies. The vessel used to serve this chocolate liquid was stubbier by nature to help make the liquid frothier. The vessels also tended to be decorated in intricate designs and patterns, which tended to only be accessible by the rich.[11]

Aztec use[edit]

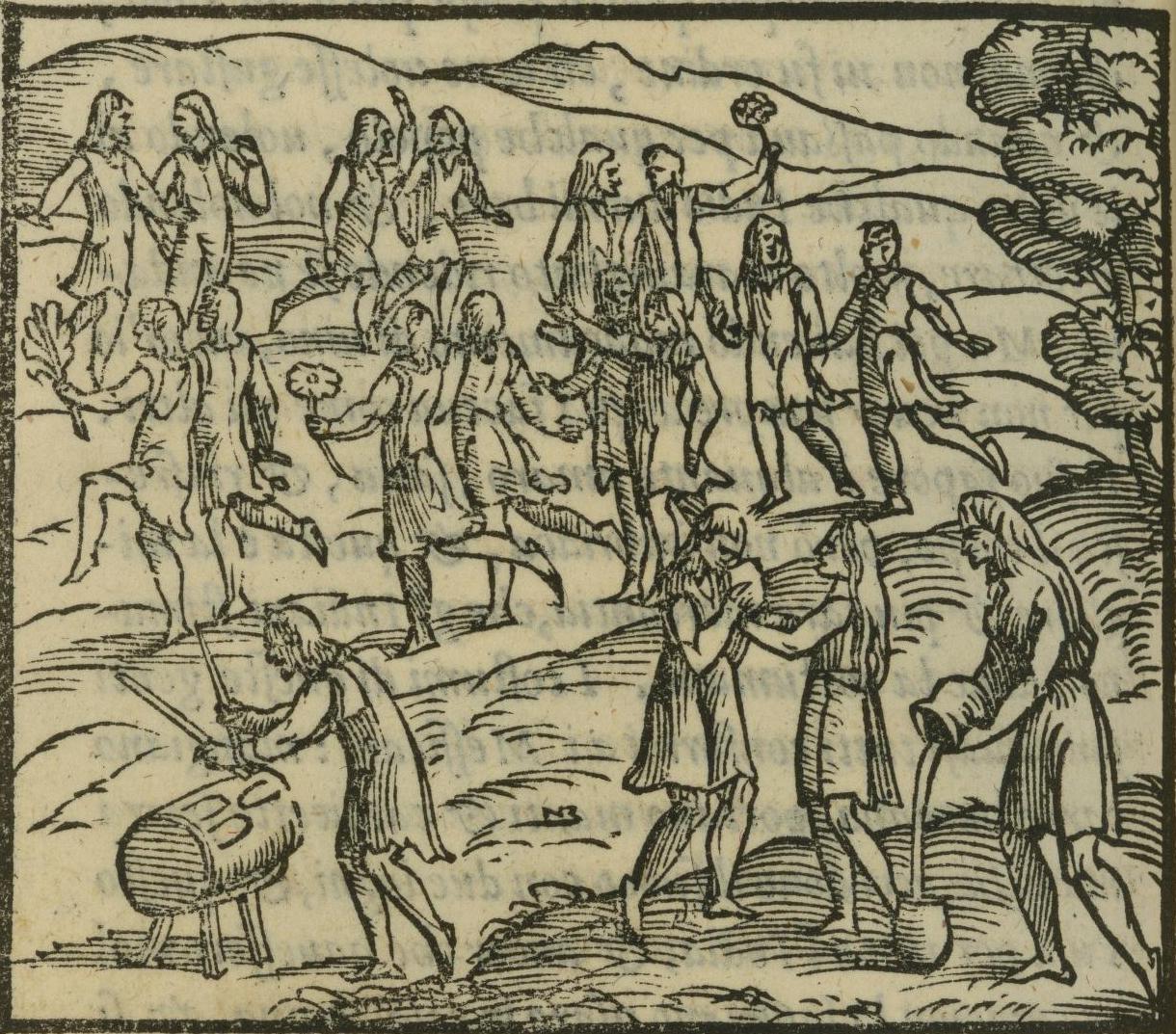

By 1400, the Aztec Empire took over a sizable part of Mesoamerica. The Aztecs had not cultivated cacao themselves, so were forced to import it.[3] All of the areas that were conquered by the Aztecs that grew cacao beans were ordered to pay them as a tax. The cacao bean became a form of currency.[2] The Spanish conquistadors left records of the value of the cacao bean, noting for instance that 100 beans could purchase a canoe filled with fresh water or a turkey hen.[6][15] The Aztecs associated cacao with the god Quetzalcoatl, who they believed had been condemned by the other gods for sharing chocolate with humans.[3] Unlike the Maya of Yucatán, the Aztecs drank chocolate cold. It was consumed for a variety of purposes, as an aphrodisiac or as a treat for men after banquets, and it was also included in the rations of Aztec soldiers.[16] Some Aztec sacrifice victims who did not wish to join in ritual dancing before their death were usually given a gourd of chocolate to cheer them up. [17]

History in Europe[edit]

Early history[edit]

Until the 16th century, the cacao tree was wholly unknown to Europeans.[3]

Christopher Columbus encountered the cacao bean on his fourth mission to the Americas on August 15, 1502, when he and his crew seized a large native canoe that proved to contain among other goods for trade, cacao beans.[18] His son Ferdinand commented that the natives greatly valued the beans, which he termed almonds, «for when they were brought on board ship together with their goods, I observed that when any of these almonds fell, they all stooped to pick it up, as if an eye had fallen.»[18] But while Columbus took cacao beans with him back to Spain,[18] it made no impact until Spanish friars introduced chocolate to the Spanish court.[3]

Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés may have been the first European to encounter chocolate when he observed it in the court of Montezuma in 1519.[19][20] In 1568, Bernal Díaz, who accompanied Cortés in the conquest of the Aztec Empire, wrote of this encounter which he witnessed:

From time to time, they served him [Montezuma] in cups of pure gold a certain drink made from cacao. It was said that it gave one power over women, but this I never saw. I did see them bring in more than fifty large pitchers of cacao with froth in it, and he drank some of it, the women serving with great reverence.[21]

José de Acosta, a Spanish Jesuit missionary who lived in Peru and then Mexico in the later 16th century, described its use more generally:

Loathsome to such as are not acquainted with it, having a scum or froth that is very unpleasant taste. Yet it is a drink very much esteemed among the Indians, wherewith they feast noble men who pass through their country. The Spaniards, both men and women that are accustomed to the country are very greedy of this chocolate. They say they make diverse sorts of it, some hot, some cold, and some temperate, and put therein much of that «chili»; yea, they make paste thereof, the which they say is good for the stomach and against the catarrh.

After the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs, chocolate was imported to Europe.[2] In the beginning, Spaniards would use it as a medicine to treat illnesses such as abdominal pain because it had a bitterness to it. Once sweetened, it transformed.[22] It quickly became a court favorite. It was still served as a beverage, but the addition of sugar or honey counteracted the natural bitterness.[6] The Spaniards initially intended to recreate the original taste of the Mesoamerican chocolate by adding similar spices, but this habit had faded away by the end of the eighteenth century.[23] At first chocolate was largely a privilege of the rich while the lower class drank coffee, but once the steam engine was invented in the late 1700s, mass production became possible. [24] Within about a hundred years, chocolate had established a foothold throughout Europe.[3]

Etymology[edit]

According to the authority on the Spanish language, the Royal Spanish Academy, the Spanish word «chocolate» is derived from the Nahuatl word «xocolatl» (pronounced Nahuatl pronunciation: [ ʃoˈkolaːtɬ]), which is made up from the words «xococ» meaning sour or bitter, and «atl» meaning water or drink.[25] However, as William Bright noted[26] the word «chocolatl» doesn’t occur in early central Mexican colonial sources, making this an unlikely derivation. Early sources have cacaua atl meaning «a drink made from cacao».[27] The word xocolatl is not attested; there is a different word xocoatl referring to a drink made of maize.[27] The proposed development x- to ch- is also unexplained.[28] Santamaria[29] gives a derivation from the Yucatec Maya word chokol meaning hot, and the Nahuatl atl meaning water. More recently Dakin and Wichman derive it from an original Eastern Nahuatl form chicolatl, which they relate to the term for a beater or frothing stick, chicoli, hence «beaten drink».[28] Kaufman and Justeson disagree with this etymology (and all other suggestions), considering that the origin of the first element of the name remains unknown, but agree that the original form was likely chicolatl.[30]

Expansion[edit]

An early 20th-century chocolate advertisement

The desire for chocolate created a thriving slave market, as between the early 17th and late 19th centuries the laborious and slow processing of the cacao bean was manual.[3] Cacao plantations spread, as the English, Dutch, and French colonized and planted. With the depletion of Mesoamerican workers, largely to disease, cocoa beans production was often the work of poor wage laborers and enslaved Africans.

In 1729, the first mechanical cocoa grinder was invented in Bristol, England. Walter Churchman petitioned the king of England for patent and sole use of an invention for the “expeditious, fine and clean making of chocolate by an engine.” The patent was granted by King George II to Walter Churchman for a water engine used to make chocolate. Churchman probably used water-powered edge runners for preparing cacao beans by crushing on a far larger scale than previously.[31][32] The patent for a chocolate refining process was later bought in 1761 by Joseph Fry who started the company that was to become J. S. Fry & Sons.[33]

Wind-powered and horse-drawn mills were used to speed production, augmenting human labor. Heating the working areas of the table-mill, an innovation that emerged in France in 1732, also assisted in extraction.[34]

The Chocolaterie Lombart, created in 1760, claimed to be the first chocolate company in France, ten years before Pelletier et Pelletier.[35]

New processes that improved the production of chocolate emerged early in the Industrial Revolution.[2] In 1815, Dutch chemist Coenraad van Houten introduced alkaline salts to chocolate, which reduced its bitterness.[3] A few years thereafter, in 1828, he created a press to remove about half the natural fat (cacao butter) from chocolate liquor, which made chocolate both cheaper to produce and more consistent in quality. This innovation, known as «Dutch cocoa», introduced the modern era of chocolate[18] and was instrumental in the transformation of chocolate to its solid form. In 1847 J. S. Fry & Sons learned to make chocolate moldable by adding back melted cacao butter.[6] Milk had sometimes been used as an addition to chocolate beverages since the mid-17th century, but in 1875 Daniel Peter invented milk chocolate by mixing a powdered milk developed by Henri Nestlé with the liquor.[3][18] In 1879, the texture and taste of chocolate was further improved when Rodolphe Lindt invented the conching machine.[36]

Lindt & Sprüngli AG, a Swiss-based concern with global reach, had its start in 1845 as the Sprüngli family confectionery shop in Zurich that added a solid-chocolate factory the same year the process for making solid chocolate was developed and later bought Lindt’s factory. Besides Nestlé, several chocolate companies had their start in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Cadbury was manufacturing boxed chocolates in England by 1868.[3] In 1893, Milton S. Hershey purchased chocolate processing equipment at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and soon began the career of Hershey’s chocolates with chocolate-coated caramels.

Due to improvements in machines, chocolate underwent a transformation from a primarily a drink to food, and different types of chocolate began to emerge. At the same time, the price of chocolate began to drop dramatically in the 1890s and 1900s as the production of chocolate began to shift away from the New World to Asia and Africa. Therefore, chocolate could be purchased by the middle class.[35] In 1900–1907, Cadbury’s fell into a scandal due to their reliance on West African slave plantations.[37]

Modern use[edit]

Roughly two-thirds of the world’s cocoa is produced in Western Africa, with Ivory Coast being the largest source, producing a total crop of 1,448,992 Tonnes.[38] Ghana, Nigeria, and Cameroon are other West African countries among the top 5 cocoa-producing countries in the world. Like many food industry producers, individual cocoa farmers are at the mercy of volatile world markets. The price can vary from between £500 ($945) and £3,000 ($5,672) per ton in the space of just a few years.[citation needed] While investors trading in cocoa can dump shares at will, individual cocoa farmers cannot ramp up production and abandon trees at anywhere near that pace.

Only three to four percent of «cocoa futures» contracts traded in the cocoa markets ever end up in the physical delivery of cocoa. Every year seven to nine times more cocoa is bought and sold on the exchange than exists.

See also[edit]

- Alonso de Molina’s dictionary of 1571 and of 1555

- Food history

- History of yerba mate

Further reading[edit]

- Mara P. Squicciarini and Johan Swinnen. 2016. The Economics of Chocolate. Oxford University Press.

- HP Newquist. 2017. The Book of Chocolate: The Amazing Story of the World’s Favorite Candy, Viking.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Watson, Traci (22 January 2013). «Earliest Evidence of Chocolate in North America». Science. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d Newquist, H. P. (2017). The book of chocolate : the amazing story of the world’s favorite candy (First American ed.). New York, New York. ISBN 978-0-670-01574-0. OCLC 919202329.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kerr, Justin (2007). «History of Chocolate». Field Museum. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ^ Kiple, Kenneth F.; Kriemhild Coneè Oyurnelas (2000). The Cambridge world history of food. Cambridge University Press. pp. 635–638. ISBN 978-0-521-40214-9.

- ^ Schnepel, Ellen (Fall 2002). «Chocolate: From Bean to Bar». Gastronomica. 2 (4): 98–100. doi:10.1525/gfc.2002.2.4.98.

- ^ a b c d Bensen, Amanda (March 1, 2008). «A Brief History of Chocolate». Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ a b Terry G. Powis; W. Jeffrey Hurst; María del Carmen Rodríguez; Ponciano Ortíz C.; Michael Blake; David Cheetham; Michael D. Coe; John G. Hodgson (December 2007). «Oldest chocolate in the New World». Antiquity. 81 (314). ISSN 0003-598X. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ^ «Sweet discovery: New UBC study pushes back the origins of chocolate». UBC News. 29 October 2018.

- ^ Zarrillo, Sonia; Gaikwad, Nilesh; Lanaud, Claire; Powis, Terry; Viot, Christopher; Lesur, Isabelle; Fouet, Olivier; Argout, Xavier; Guichoux, Erwan; Salin, Franck; Solorzano, Rey Loor; Bouchez, Olivier; Vignes, Hélène; Severts, Patrick; Hurtado, Julio; Yepez, Alexandra; Grivetti, Louis; Blake, Michael; Valdez, Francisco (December 2018). «The use and domestication of Theobroma cacao during the mid-Holocene in the upper Amazon». Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (12): 1879–1888. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0697-x.

- ^ a b Edgar, Blake (November 2010). «The Power of Chocolate». Archaeology. 63 (6): 20–25.

- ^ a b c d Coe, Sophie Dobzhansky; Coe, Michael D. (2007). The True History of Chocolate. Thames and Hudson. pp. 59–61. ISBN 978-0-500-28696-8.

- ^ Thompson, J. Eric S. (1956). «Notes on the use of cacao in Middle America». Middle American Archaeology. Cambridge Mass. 128: 95–116.

- ^ «Medicinal and Ritualistic Use for Chocolate in Mesoamerica — HeritageDaily — Heritage & Archaeology News». www.heritagedaily.com. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- ^ Presilla, Maricel E. (2009). The New Taste of Chocolate, Revised: A Cultural and Natural History of Cacao with Recipes. New York: Ten Speed Press. pp. 12, 16, 22. ISBN 978-1580089500.

- ^ Keoke, Emory Dean; Porterfield, Kay Marie (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of American Indian Contributions to the World: 15,000 Years of Inventions and Innovations. Infobase Publishing. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-4381-0990-9.

- ^ Szogyi, Alex (1 January 1997). Chocolate: Food of the Gods. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 149–151. ISBN 978-0-313-30506-1.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Fiegl, Amanda. «A Brief History of Chocolate». Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2022-12-01.

- ^ a b c d e Spadaccini, Jim. «The Sweet Lure of Chocolate». Exploratorium. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ^ Burleigh, Robert (2002). Chocolate: Riches from the Rainforest. Harry N. Abrams, Ins., Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8109-5734-3.

- ^ Dillinger, Teresa L.; Barriga, Patricia; Escárcega, Sylvia; Jimenez, Martha; Lowe, Diana Salazar; Grivetti, Louis E. (2000-08-01). «Food of the Gods: Cure for Humanity? A Cultural History of the Medicinal and Ritual Use of Chocolate». The Journal of Nutrition. 130 (8): 2057S–2072S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.8.2057S. ISSN 0022-3166.

- ^ Idell, Albert (ed.) (1956) The Bernal Diaz Chronicles. Doubleday Dolphin. p. 160

- ^ TED-Ed (2017-03-16), The history of chocolate — Deanna Pucciarelli, archived from the original on 2021-12-19, retrieved 2018-05-07

- ^ Norton, Marcy (April 2004). «Conquests of Chocolate». OAH Magazine of History. 18 (3): 16. doi:10.1093/maghis/18.3.14. JSTOR 25163677.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Fiegl, Amanda. «A Brief History of Chocolate». Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2022-12-01.

- ^ «Diccionario de la lengua española, Real Academia Española». rae.es.

- ^ Campbell, Lyle (1977). Quichean Linguistic Prehistory; University of California Publications in Linguistics No. 81. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 104. ISBN 9780520095311.

- ^ a b Molina, Fray Alonso de (1977). Vocabulario en Lengua Castellana y Mexicana y Mexicana y Castellana. Edicion Facsimile. Mexico: Editorial Porrua, S.A. p. 10.

- ^ a b Dakin, Karen; Wichmann, Soren (2000). «Cacao and Chocolate A Uto-Aztecan perspective». Ancient Mesoamerica. Cambridge. 11 (1): 55–75. doi:10.1017/S0956536100111058. S2CID 162616811.

- ^ Santamaria, Francisco (2005). Diccionario de Mejicanismos. Mexico: Editorial Porrúa S. A. pp. 412–413. ISBN 978-9700759579.

- ^ Kaufman, Terrence; Justeson, John (2007). «The history of the word for Cacao in ancient Mesoamerica». Ancient Mesoamerica. 18 (2): 193–237. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Around Keynsham & Saltford Past and Present (PDF). Keynsham & Saltford Local History Society. 2010. Includes much information on J. S. Fry & Sons

- ^ Grivetti, Louis E.; Shapiro, Howard-Yana (2008). «Appendix 8: Chocolate Timeline». Chocolate: History, Culture, and Heritage. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 855–928. doi:10.1002/9780470411315.app8. ISBN 978-0-470-41131-5.

- ^ «Desert Island Doc: A charter for chocolate | Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives». Bristol Museums. 30 November 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Wilson, K.; Hurst, W. Jeffrey (2015). Chocolate and Health: Chemistry, Nutrition and Therapy. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 219. doi:10.1039/9781782622802-00218. ISBN 978-1-78262-505-6.

- ^ a b Clarence-Smith, William Gervase (2003), Cocoa and Chocolate, 1765-1914, Routledge, p. 48, ISBN 978-1-134-60778-5

- ^ Klein, Christopher (February 14, 2014). «The Sweet History of Chocolate». History. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ^ North, Rodney (2008). «CHILD LABOR IN THE COCOA INDUSTRY». Equal Exchange.

- ^ «Top 10 Cocoa Producing Countries». WorldAtlas. Retrieved 2017-10-09.

First Known Use: Around 1580

Etymology:

This week, people around the world will be opening heart-shaped boxes with “the food of the gods” nestled in crepe paper inside. But it took a lot of scientific and anthropological work to unearth the origins of both the tasty recipe and the word chocolate—which some anthropologists argue is an Indigenous word that has not been Anglicized.

The Bean Behind The Bars

“If the history of cacao were a 24-hour cycle, the glossy chocolate bars that we love and the confections that we love would only occupy a few seconds,” culinary historian Maricel Presilla told the The Slow Melt podcast.

That long history begins with the domestication of cacao, the bean used to make cocoa and chocolate. Just last year, researchers unearthed residual traces of DNA from Theobroma cacao in ceramic vessels from the Amazon basin. The vessels date back to roughly 3000 BCE, more than 1,500 years earlier than previously thought.

It’s typically thought that cacao was used for beverages, but that’s too simple of an explanation, says Carla D. Martin.

Martin is an anthropologist at Harvard University, and the founder and executive director of the Fine Cacao and Chocolate Institute. Yes, ancient people did drink it. But the beans were also used as flavoring for other foods, and as ritual offerings. They were also used as currency in Nicaragua, Mexico, and colonial Guatemala (which is now present day El Salvador). The Indigenous Pipil people in the Izalcos, a region of El Salvador, even did away with other trade items like feathers, and used cacao as their sole currency. Other regions followed their lead, and “it’s like [the people of] the Izalcos became the Swiss bankers,” says Kathryn Sampeck, an anthropologist at Illinois State University. In her research, Sampeck noticed that as cacao production was declining elsewhere during the early 1500s, the Izalcos produced “astronomical” amounts of the bean.

“I’ve done some analyses that look at the production levels in this region comparing it to other places, and it’s crazy,” Sampeck says. “Out of this port, 1.2 billion cacao beans per year for a span of at least 15 years—and that’s legal trade.” Because cacao was their sole currency, when Sampeck examined financial records from the region, she found evidence of extreme inflation due to the megaproduction of the bean.”

Prices in the Izalcos were at a minimum three times as much as the next-highest cacao producers, and sometimes as much as ten times the amount. “So, when I say when I say ‘astronomical,’ I mean it’s really astounding what this little place was producing,” she says.

When the Spanish arrived in what is now Central America, they too were quick to accept cacao as official payment, and even brought it back to Spain and incorporated it into their own monetary system for a time.

“[The Spaniards] had these big metal coins, and if they needed to make change to buy a tomato or something small, the only way to make change was to get out a knife and carve out a chunk of that,” says Martin. “It was totally impractical.”

It was this perceived value that gave cacao and chocolate a leg up on achiote or other ingredients from the Americas. In fact, cacao functioned as small change in the Izalcos as late as the 19th century.

From Cacao To Chocolate

Around 1580, the word chocolate cropped up in both European and Mexican texts, says Sampeck. And it wasn’t simply another name for cacao—it was the Pipil’s Indigenous Nahuat word referring specifically to the special drink of the Izalcos, where the first prototype recipes for what we call chocolate emerged.

“I think of it as a phenomenon kind of like buffalo chicken wings or Q-tips or anything like that,” says Sampeck, “where there’s this kind of branding that happens in the 16th century around 1580 that really identified that the word for a typical, local drink starts to become the name for for the seed and even a tree and all of that. It becomes much more generalized.”

As cacao’s popularity skyrocketed across the world, the word for the Pipil’s special drink exploded in the colonial and transatlantic markets, she says.

But according to Sampeck, the word never Anglicized. “It’s one of the words that’s never been translated… Every day, across the world, people are speaking [the Indigenous language] Nahuat,” she says. (Sampeck notes that there are scholars and linguists who argue that the word is a blend of Indigenous languages, or that it has a Maya root. But it was the Pipil people who were speaking the word at the time that it became adopted in other languages.)

“I think one of the most common beliefs is that chocolate is something European in nature,” says Carla Martin. “But what our research has really shown is that chocolate is in fact an Indigenous foodstuff that has conquered the hearts and minds of the world. So, whenever we’re consuming chocolate, we’re consuming something that was really designed in the Americas, by the Indigenous people of the Americas—and that’s really unique.”

Choc Full Of Science

Between that first domestication of cacao and today, researchers and chocolate makers have scientifically engineered chocolate to taste—and feel—even better to our palates.

“People like chocolate for many reasons that they perhaps don’t directly think about,” food scientist Richard Ludesher told Science Friday in 2014. “They think about the taste of chocolate. They think about the sweetness of chocolate. But an extremely important property of chocolate is its texture, and its property of being hard at room temperature and yet completely melty in your mouth.”

That melt-in-your-mouth property, surprisingly, comes down to crystals. Chocolate is a crystalline solid, which means that its molecules, atoms, and ions act together in an orderly pattern and have a flat surface. Creating those crystal formations is part of the art of making chocolate.

First, chocolate makers grind the cocoa nibs into a chocolate liquor. Once the cocoa particles are suspended in that liquor, the candy makers add other ingredients, like sugar. Then, they mix the whole melty, delicious liquor together to reduce the size of particles and release flavors and acids that are embedded in it. That process is essential for flavoring the chocolate, but it leaves the cocoa butter unstable. In order to remedy that, chocolatiers slowly heat the mixture to a point that melts away all the unwanted crystal formations, but leaves the ones necessary for stabilization.

“Chocolate should have a certain look to it, have a gloss and a sheen to it. It needs to have a snap, and it needs to have the right mouth feel,” says Ludescher. “What you have is a fairly complicated thing. And when you put it in your mouth, and you wait long enough—if you’re not impatient—it will melt back to that liquor and release all the flavor.”

Sources And Further Reading:

- Special thanks to Carla D. Martin and Kathryn Sampeck

- “The use and domestication of Theobroma cacao during the mid-Holocene in the upper Amazon” (Nature Ecology and Evolution)

- “The Deep Origin: Latin America” (The Slow Melt Podcast, Episode

- “The History of the Word for Cacao in Ancient Mesoamerica” (Ancient Mesoamerica)

- “The Bitter and Sweet of Chocolate in Europe” (Socio.hu: The Social Meaning of Food: Special Issue in English No. 3)

- Choc Full of Science (Science Friday)

Meet the Writer

About Johanna Mayer

@yohannamayer

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.

Table of Contents

- How many different words can be formed using all the letters in the word chocolate?

- What words can you make with name?

- What language is the word chocolate?

- Is chocolate the same in all languages?

- Is chocolate a borrowed word?

- What borrowed words?

- Is pizza a borrowed word?

- Why do we call it pizza?

- What is the most beautiful French word?

- What are the 1000 most common words in French?

- What is loanwords in English?

- How many English words are used in everyday English?

- Why do we use loanwords?

- What word is the same in every language?

- Is banana the same in all languages?

- What’s the shortest word in the world?

- What is the most universal language?

- What is the 1st language in the world?

- What is the richest language in the world?

- What language has the largest vocabulary?

- Which is the most beautiful language in the world?

- Which is the sweetest food in the world?

- What is the softest language?

- What is the most popular language in the world 2020?

Etymologists trace the origin of the word “chocolate” to the Aztec word “xocoatl,” which referred to a bitter drink brewed from cacao beans. The Latin name for the cacao tree, Theobroma cacao, means “food of the gods.”

How many different words can be formed using all the letters in the word chocolate?

Total Number of words made out of Chocolate = 165 Chocolate is a 9 letter long Word starting with C and ending with E. Below are Total 165 words made out of this word.

What words can you make with name?

Words that can be made with name

- amen.

- mane.

- mean.

- name.

- nema.

What language is the word chocolate?

The word “chocolate” comes from the Classical Nahuatl word Xocolātl, and entered the English language from the Spanish language.

Is chocolate the same in all languages?

Yes. As other answers said, those words were borrowed from English, Spanish, and French into most languages. Chocolate was originally from Nahuatl chocolātl.

Is chocolate a borrowed word?

Not only is it spoken as a second language by millions around the world, many of its words have found their way into foreign languages….Food and Drink.

| English Term | Original Spanish Term | Meaning/Origin of Spanish Term |

|---|---|---|

| Chocolate | Chocolate | Borrowed by Spanish from the Nahuatl language. |

What borrowed words?

Loanwords are words adopted by the speakers of one language from a different language (the source language). A loanword can also be called a borrowing. The words simply come to be used by a speech community that speaks a different language from the one these words originated in.

Is pizza a borrowed word?

The origin of the word pizza Pizza, of course, is borrowed from Italian, but the deeper ingredients of the word, if you will, are unclear. Others look to the Langobardic (an ancient German language in northern Italy) bizzo, meaning “bite.” Whatever the origin, we say, “delicious.”

Why do we call it pizza?

Their origin is from Latin pinsere “to pound, stamp”. The Lombardic word bizzo or pizzo meaning “mouthful” (related to the English words “bit” and “bite”), which was brought to Italy in the middle of the 6th century AD by the invading Lombards.

What is the most beautiful French word?

Here are the most beautiful French words

- Argent – silver. Argent is used in English too to refer to something silver and shiny.

- Atout – asset. Masculine, noun.

- Arabesque – in Arabic fashion or style. Feminine, noun.

- Bijoux – jewelry. Masculine, noun.

- Bisous – kisses. Masculine, noun.

- Bonbon – candy.

- Brindille – twig.

- Câlin – hug.

What are the 1000 most common words in French?

This is a list of the 1,000 most commonly spoken French words….1000 Most Common French Words.

| Number | French | in English |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | comme | as |

| 2 | je | I |

| 3 | son | his |

| 4 | que | that |

What is loanwords in English?

in the History of English. Loanwords are words adopted by the speakers of one language from a different language (the source language). A loanword can also be called a borrowing. They simply come to be used by a speech community that speaks a different language from the one they originated in.

How many English words are used in everyday English?

We considered dusting off the dictionary and going from A1 to Zyzzyva, however, there are an estimated 171,146 words currently in use in the English language, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, not to mention 47,156 obsolete words.

Why do we use loanwords?

Over time, loanwords become such an essential part of the language that even native speakers can’t say where the word originated. Loanwords make language learning a bit easier because the odds are that you already know some of the words based on your existing language skills!

What word is the same in every language?

huh

Is banana the same in all languages?

The word comes from Arabic, meaning finger or toe since many bananas are quite small. Banana isn’t the same in all languages, but pineapple is pretty damn close, ironically it’s called ananas.

What’s the shortest word in the world?

Eunoia

What is the most universal language?

English

What is the 1st language in the world?

Tamil

What is the richest language in the world?

What language has the largest vocabulary?

Which is the most beautiful language in the world?

The Beauty Of Languages

- Arabic language. Arabic is one of the most beautiful languages in the world.

- English language. English is the most gorgeous language in the world.

- Italian language. Italian is one of the most romantic languages in the world.

- Welsh language.

- Persian language.

Which is the sweetest food in the world?

Alitamine is one of the sweetest substances. It is an artificial sweetening agent. It is literally 2000 times sweeter than cane sugar.

What is the softest language?

Italian language

What is the most popular language in the world 2020?

The top 12 most spoken languages in the world

- English (1,132 million speakers)

- Mandarin Chinese (1,117 million speakers)

- Hindi (615 million speakers)

- Spanish (534 million speakers)

- Arabic (274 million speakers)

- Bangla/Bengali (265 million speakers)

- Russian (258 million speakers)

- Portuguese (234 million speakers)

Across the curriculum

Язык — 1

-

Соедините слова с картинками. Эти слова похожи со словами в вашем языке?

1. zebra

2. chocolate

3. tea

4. algebra

5. piano

6. pyjamas

-

Прочитайте текст и ответьте на вопросы.

Доримская эпоха: Первые люди в Великобритании говорили по-кельтски.

1 век нашей эры: Римляне вторгаются в Великобританию. Латынь — язык Римской империи.

5 век нашей эры: Германские племена вторгаются из континентальной Европы и говорят на древнеанглийском. Слово «англичане» происходит от Англов, названия одного из племен. Современные английские слова, такие как «вода» и «сильный», происходят из древнеанглийского. Викинги вторгаются и вводят новые слова.

1066 год нашей эры: Норманны вторгаются в Великобританию, и французский становится официальным языком. Английский язык меняет и заимствует многие слова из французского, например, «говядина».

1600 год: Современный английский язык берет свои корни со времен Шекспира. Латынь и греческий оказывают большое влияние, потому что являются языками ученых. В английском языке используются много латинских слов, оканчивающихся на –us или –um, например, curriculum и circus. Слова, оканчивающиеся на –ology и –phobia, происходят от греческих слов, например, биология и арахнофобия.

16-19 века: Исследователи и путешественники приносят много новых слов со всего мира: слова для животных (зебра из Конго, африканский язык), еда (шоколад из Науатля, ацтекский язык), одежда (пижама из хинди в Индии), напитки (чай из китайского), математические термины (алгебра из арабского) и музыкальные термины (фортепиано из итальянского).

Наши дни: Английский язык продолжает расти, особенно с новыми словами в науке и технике, например, «микрочип» и «киберпространство».

1. Откуда родом слово «англичане»?

2. Какие два слова произошли от древнеанглийского?

3. Откуда родом английское слово «говядина»?

4. Из какого языка произошло слово «шоколад»?

5. Какое слово произошло из хинди?

6. Откуда родом слово «алгебра»?

1. The word English comes from the Angles, the name of one of the tribes.

2. Modern English words like water and strong come from old English.

3. The word beef comes from French.

4. The word chocolate comes from Nahuatl, the Aztec language.

5. The word pyjamas comes from Hindi.

6. The word algebra comes from Arabic.

1. Слово «англичане» происходит от Англов, названия одного из племен.

2. Современные английские слова, такие как вода и сильный, происходят из древнеанглийского.

3. Слово говядина происходит от французского.

4. Слово шоколад происходит от Науатль, языка ацтеков.

5. Слово пижама происходит от хинди.

6. Слово алгебра происходит от арабского.

-

Прочитайте текст снова и посмотрите на эти слова. Как вы считаете, они происходят от латинского или греческого языков? Перерисуйте таблицу и запишите каждое слово в верный столбик.

| Латинские слова | Перевод | Греческие слова | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|

| abacus | счеты | astrology | астрология |

| museum | музей | agoraphobia | агорафобия |

| aquarium | аквариум | claustrophobia | клаустрофобия |

| cactus | кактус | mythology | мифология |

Subjects>Arts & Humanities>English Language Arts

Wiki User

∙ 10y ago

Best Answer

Copy

From the Mexican dialect Nahuatl, xococ, meaning bitter. Brought

to Europe by the Spanish in 1520

Wiki User

∙ 10y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What language does the word the word chocolate come from?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Continue Learning about English Language Arts

What language does the word alkali come from?

The word alkali come from the language Arabic

What language did the word piano come from?

this is an Italian word

Which language does the word cinema come from?

its a Greek word

What language does the word Sauna come from?

it comes from the language Finland

What language does the word dollar come from?

From the German word Thaler

Related questions

People also asked

Chocolate is a food made from roasted and ground cacao seed kernels that is available as a liquid, solid, or paste, either on its own or as a flavoring agent in other foods. Cacao has been consumed in some form since at least the Olmec civilization (19th-11th century BCE),[1][2] and the majority of Mesoamerican people ─ including the Maya and Aztecs ─ made chocolate beverages.[3]

Chocolate bars in its most common dark, milk, and white varieties. |

|

| Region or state | Mesoamerica |

|---|---|

| Main ingredients | Chocolate liquor, cocoa butter for white chocolate, often with added sugar |

|

The seeds of the cacao tree have an intense bitter taste and must be fermented to develop the flavor. After fermentation, the seeds are dried, cleaned, and roasted. The shell is removed to produce cocoa nibs, which are then ground to cocoa mass, unadulterated chocolate in rough form. Once the cocoa mass is liquefied by heating, it is called chocolate liquor. The liquor may also be cooled and processed into its two components: cocoa solids and cocoa butter. Baking chocolate, also called bitter chocolate, contains cocoa solids and cocoa butter in varying proportions, without any added sugar. Powdered baking cocoa, which contains more fiber than cocoa butter, can be processed with alkali to produce dutch cocoa. Much of the chocolate consumed today is in the form of sweet chocolate, a combination of cocoa solids, cocoa butter or added vegetable oils, and sugar. Milk chocolate is sweet chocolate that additionally contains milk powder or condensed milk. White chocolate contains cocoa butter, sugar, and milk, but no cocoa solids.

Chocolate is one of the most popular food types and flavors in the world, and many foodstuffs involving chocolate exist, particularly desserts, including cakes, pudding, mousse, chocolate brownies, and chocolate chip cookies. Many candies are filled with or coated with sweetened chocolate. Chocolate bars, either made of solid chocolate or other ingredients coated in chocolate, are eaten as snacks. Gifts of chocolate molded into different shapes (such as eggs, hearts, coins) are traditional on certain Western holidays, including Christmas, Easter, Valentine’s Day, and Hanukkah. Chocolate is also used in cold and hot beverages, such as chocolate milk and hot chocolate, and in some alcoholic drinks, such as creme de cacao.

Although cocoa originated in the Americas, West African countries, particularly Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, are the leading producers of cocoa in the 21st century, accounting for some 60% of the world cocoa supply.

With some two million children involved in the farming of cocoa in West Africa, child slavery and trafficking associated with the cocoa trade remain major concerns.[4][5] A 2018 report argued that international attempts to improve conditions for children were doomed to failure because of persistent poverty, absence of schools, increasing world cocoa demand, more intensive farming of cocoa, and continued exploitation of child labor.[4]

History

Mesoamerican usage

Image from a Maya ceramic depicting a container of frothed chocolate

Chocolate has been prepared as a drink for nearly all of its history. For example, one vessel found at an Olmec archaeological site on the Gulf Coast of Veracruz, Mexico, dates chocolate’s preparation by pre-Olmec peoples as early as 1750 BC.[6] On the Pacific coast of Chiapas, Mexico, a Mokaya archaeological site provides evidence of cocoa beverages dating even earlier to 1900 BC.[7][6] The residues and the kind of vessel in which they were found indicate the initial use of cocoa was not simply as a beverage, but the white pulp around the cocoa beans was likely used as a source of fermentable sugars for an alcoholic drink.[8]

Aztec. Man Carrying a Cacao Pod, 1440–1521. Volcanic stone, traces of red pigment. Brooklyn Museum.

An early Classic-period (460–480 AD) Maya tomb from the site in Rio Azul had vessels with the Maya glyph for cocoa on them with residue of a chocolate drink, which suggests that the Maya were drinking chocolate around 400 AD.[9] Documents in Maya hieroglyphs stated chocolate was used for ceremonial purposes in addition to everyday life.[10] The Maya grew cacao trees in their backyards[11] and used the cocoa seeds the trees produced to make a frothy, bitter drink.[12]

By the 15th century, the Aztecs had gained control of a large part of Mesoamerica and had adopted cocoa into their culture. They associated chocolate with Quetzalcoatl, who, according to one legend, was cast away by the other gods for sharing chocolate with humans,[13] and identified its extrication from the pod with the removal of the human heart in sacrifice.[14] In contrast to the Maya, who liked their chocolate warm, the Aztecs drank it cold, seasoning it with a broad variety of additives, including the petals of the Cymbopetalum penduliflorum tree, chili pepper, allspice, vanilla, and honey.

The Aztecs were unable to grow cocoa themselves, as their home in the Mexican highlands was unsuitable for it, so chocolate was a luxury imported into the empire.[13] Those who lived in areas ruled by the Aztecs were required to offer cocoa seeds in payment of the tax they deemed «tribute».[13] Cocoa beans were often used as currency.[15] For example, the Aztecs used a system in which one turkey cost 100 cocoa beans[16] and one fresh avocado was worth three beans.[17]

The Maya and Aztecs associated cocoa with human sacrifice, and chocolate drinks specifically with sacrificial human blood.[18][19]

The Spanish royal chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés described a chocolate drink he had seen in Nicaragua in 1528, mixed with achiote: «because those people are fond of drinking human blood, to make this beverage seem like blood, they add a little achiote, so that it then turns red. … and part of that foam is left on the lips and around the mouth, and when it is red for having achiote, it seems a horrific thing, because it seems like blood itself.»[19]

European adaptation

Chocolate soon became a fashionable drink of the European nobility after the discovery of the Americas. The morning chocolate by Pietro Longhi; Venice, 1775–1780

Until the 16th century, no European had ever heard of the popular drink from the Central American peoples.[13] Christopher Columbus and his son Ferdinand encountered the cocoa bean on Columbus’s fourth mission to the Americas on 15 August 1502, when he and his crew stole a large native canoe that proved to contain cocoa beans among other goods for trade.[20] Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés may have been the first European to encounter it, as the frothy drink was part of the after-dinner routine of Montezuma.[9][21] José de Acosta, a Spanish Jesuit missionary who lived in Peru and then Mexico in the later 16th century, wrote of its growing influence on the Spaniards:

Although bananas are more profitable, cocoa is more highly esteemed in Mexico… Cocoa is a smaller fruit than almonds and thicker, which toasted do not taste bad. It is so prized among the Indians and even among Spaniards… because since it is a dried fruit it can be stored for a long time without deterioration, and they brings ships loaded with them from the province of Guatemala… It also serves as currency, because with five cocoas you can buy one thing, with thirty another, and with a hundred something else, without there being contradiction; and they give these cocoas as alms to the poor who beg for them. The principal product of this cocoa is a concoction which they make that they call «chocolate», which is a crazy thing treasured in that land, and those who are not accustomed are disgusted by it, because it has a foam on top and a bubbling like that of feces, which certainly takes a lot to put up with. Anyway, it is the prized beverage which the Indians offer to nobles who come to or pass through their lands; and the Spaniards, especially Spanish women born in those lands die for black chocolate. This aforementioned chocolate is said to be made in various forms and temperaments, hot, cold, and lukewarm. They are wont to use spices and much chili; they also make it into a paste, and it is said that it is a medicine to treat coughs, the stomach, and colds. Whatever may be the case, in fact those who have not been reared on this opinion are not appetized by it.[22]

«Traités nouveaux & curieux du café du thé et du chocolate», by Philippe Sylvestre Dufour, 1685 («New and curious treatises of coffee, tea and chocolate»)

While Columbus had taken cocoa beans with him back to Spain,[20] chocolate made no impact until Spanish friars introduced it to the Spanish court.[13] After the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs, chocolate was imported to Europe. There, it quickly became a court favorite. It was still served as a beverage, but the Spanish added sugar, as well as honey (the original sweetener used by the Aztecs for chocolate), to counteract the natural bitterness.[16] Vanilla, another indigenous American introduction, was also a popular additive, with pepper and other spices sometimes used to give the illusion of a more potent vanilla flavor. Unfortunately, these spices tended to unsettle the European constitution; the Encyclopédie states, «The pleasant scent and sublime taste it imparts to chocolate have made it highly recommended; but a long experience having shown that it could potentially upset one’s stomach», which is why chocolate without vanilla was sometimes referred to as «healthy chocolate».[23] By 1602, chocolate had made its way from Spain to Austria.[24] By 1662, Pope Alexander VII had declared that religious fasts were not broken by consuming chocolate drinks. Within about a hundred years, chocolate established a foothold throughout Europe.[13]

Dutch chemist Coenraad Johannes van Houten invented «Dutch cocoa» by treating cocoa mass with alkaline salts to reduce the natural bitterness without adding sugar or milk to get usable cocoa powder.

The new craze for chocolate brought with it a thriving slave market, as between the early 1600s and late 1800s, the laborious and slow processing of the cocoa bean was manual.[13] Cocoa plantations spread, as the English, Dutch, and French colonized and planted. With the depletion of Mesoamerican workers, largely to disease, cocoa production was often the work of poor wage laborers and African slaves. Wind-powered and horse-drawn mills were used to speed production, augmenting human labor. Heating the working areas of the table-mill, an innovation that emerged in France in 1732, also assisted in extraction.[25]

Solid chocolate

Despite the drink remaining the traditional form of consumption for a long time, solid chocolate was increasingly consumed since the 18th century.[26][27] Tablets, facilitating the consumption of chocolate under its solid form, have been produced since the early 19th century. Cailler (1819)[28] and Menier (1836)[29] are early examples. In 1830, chocolate is paired with hazelnuts, an innovation due to Kohler.[30]

Meanwhile, new processes that sped the production of chocolate emerged early in the Industrial Revolution. In 1815, Dutch chemist Coenraad van Houten introduced alkaline salts to chocolate, which reduced its bitterness.[13] A few years thereafter, in 1828, he created a press to remove about half the natural fat (cocoa butter) from chocolate liquor, which made chocolate both cheaper to produce and more consistent in quality. This innovation introduced the modern era of chocolate.[20]

Known as «Dutch cocoa», this machine-pressed chocolate was instrumental in the transformation of chocolate to its solid form when, in 1847, English chocolatier Joseph Fry discovered a way to make chocolate moldable when he mixed the ingredients of cocoa powder and sugar with melted cocoa butter.[16] Subsequently, his chocolate factory, Fry’s of Bristol, England, began mass-producing chocolate bars, Fry’s Chocolate Cream, launched in 1866, and they became very popular.[31] Milk had sometimes been used as an addition to chocolate beverages since the mid-17th century, but in 1875 Swiss chocolatier Daniel Peter invented milk chocolate by mixing a powdered milk developed by Henri Nestlé with the liquor.[13][20] In 1879, the texture and taste of chocolate was further improved when Rudolphe Lindt invented the conching machine.[32]

Besides Nestlé, several notable chocolate companies had their start in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Rowntree’s of York set up and began producing chocolate in 1862, after buying out the Tuke family business. Cadbury was manufacturing boxed chocolates in England by 1868.[13] Manufacturing their first Easter egg in 1875, Cadbury created the modern chocolate Easter egg after developing a pure cocoa butter that could easily be molded into smooth shapes.[33] In 1893, Milton S. Hershey purchased chocolate processing equipment at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and soon began the career of Hershey’s chocolates with chocolate-coated caramels.

Introduction to the United States

The Baker Chocolate Company, which makes Baker’s Chocolate, is the oldest producer of chocolate in the United States. In 1765 Dr. James Baker and John Hannon founded the company in Boston. Using cocoa beans from the West Indies, the pair built their chocolate business, which is still in operation.[34][35]

White chocolate was first introduced to the U.S. in 1946 by Frederick E. Hebert of Hebert Candies in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, near Boston, after he had tasted «white coat» candies while traveling in Europe.[36][35]

Etymology

Cocoa, pronounced by the Olmecs as kakawa,[1] dates to 1000 BC or earlier.[1] The word «chocolate» entered the English language from Spanish in about 1600.[37] The word entered Spanish from the word chocolātl in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. The origin of the Nahuatl word is uncertain, as it does not appear in any early Nahuatl source, where the word for chocolate drink is cacahuatl, «cocoa water». It is possible that the Spaniards coined the word (perhaps in order to avoid caca, a vulgar Spanish word for «faeces») by combining the Yucatec Mayan word chocol, «hot», with the Nahuatl word atl, «water».[38] A widely cited proposal is that the derives from unattested xocolatl meaning «bitter drink» is unsupported; the change from x- to ch- is unexplained, as is the -l-. Another proposed etymology derives it from the word chicolatl, meaning «beaten drink», which may derive from the word for the frothing stick, chicoli.[39] Other scholars reject all these proposals, considering the origin of first element of the name to be unknown.[40] The term «chocolatier», for a chocolate confection maker, is attested from 1888.[41]

Types

Chocolate is commonly used as a coating for various fruits such as cherries and/or fillings, such as liqueurs

Several types of chocolate can be distinguished. Pure, unsweetened chocolate, often called «baking chocolate», contains primarily cocoa solids and cocoa butter in varying proportions. Much of the chocolate consumed today is in the form of sweet chocolate, which combines chocolate with sugar.

By cocoa content

Raw chocolate

Raw chocolate is chocolate produced primarily from unroasted cocoa beans.

Dark

Dark chocolate is produced by adding fat and sugar to the cocoa mixture. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration calls this «sweet chocolate», and requires a 15% concentration of chocolate liquor. European rules specify a minimum of 35% cocoa solids.[42] A higher amount of cocoa solids indicates more bitterness. Semisweet chocolate is dark chocolate with low sugar content. Bittersweet chocolate is chocolate liquor to which some sugar (typically a third), more cocoa butter and vanilla are added.[43] It has less sugar and more liquor than semisweet chocolate, but the two are interchangeable in baking. It is also known to last for two years if stored properly. As of 2017, there is no high-quality evidence that dark chocolate affects blood pressure significantly or provides other health benefits.[44]

Milk

Milk chocolate is sweet chocolate that also contains milk powder or condensed milk. In the UK and Ireland, milk chocolate must contain a minimum of 20% total dry cocoa solids; in the rest of the European Union, the minimum is 25%.[42]

White

White chocolate, although similar in texture to that of milk and dark chocolate, does not contain any cocoa solids that impart a dark color. In 2002, the US Food and Drug Administration established a standard for white chocolate as the «common or usual name of products made from cocoa fat (i.e., cocoa butter), milk solids, nutritive carbohydrate sweeteners, and other safe and suitable ingredients, but containing no nonfat cocoa solids».[45]

By application

Baking chocolate

Unsweetened baking chocolate

Baking chocolate, or cooking chocolate,[46] is chocolate intended to be used for baking and in sweet foods that may or may not be sweetened. Dark chocolate, milk chocolate, and white chocolate, are produced and marketed as baking chocolate. However, lower quality baking chocolate may not be as flavorful compared to higher-quality chocolate, and may have a different mouthfeel.[47]

Poorly tempered or untempered chocolate may have whitish spots on the dark chocolate part, called chocolate bloom; it is an indication that sugar or fat has separated due to poor storage. It is not toxic and can be safely consumed.[48]

Modeling chocolate

Modeling chocolate is a chocolate paste made by melting chocolate and combining it with corn syrup, glucose syrup, or golden syrup.[49]

Production

Chocolate is created from the cocoa bean. A cacao tree with fruit pods in various stages of ripening.

Roughly two-thirds of the entire world’s cocoa is produced in West Africa, with 43% sourced from Côte d’Ivoire,[50] where, as of 2007, child labor is a common practice to obtain the product.[51][52] According to the World Cocoa Foundation, in 2007 some 50 million people around the world depended on cocoa as a source of livelihood.[53] As of 2007 in the UK, most chocolatiers purchase their chocolate from them, to melt, mold and package to their own design.[54] According to the WCF’s 2012 report, the Ivory Coast is the largest producer of cocoa in the world.[55] The two main jobs associated with creating chocolate candy are chocolate makers and chocolatiers. Chocolate makers use harvested cocoa beans and other ingredients to produce couverture chocolate (covering). Chocolatiers use the finished couverture to make chocolate candies (bars, truffles, etc.).[56]

Production costs can be decreased by reducing cocoa solids content or by substituting cocoa butter with another fat. Cocoa growers object to allowing the resulting food to be called «chocolate», due to the risk of lower demand for their crops.[53]

Genome

The sequencing in 2010 of the genome of the cacao tree may allow yields to be improved.[57] Due to concerns about global warming effects on lowland climate in the narrow band of latitudes where cocoa is grown (20 degrees north and south of the equator), the commercial company Mars, Incorporated and the University of California, Berkeley, are conducting genomic research in 2017–18 to improve the survivability of cacao plants in hot climates.[58]

Cacao varieties

Chocolate is made from cocoa beans, the dried and fermented seeds of the cacao tree (Theobroma cacao), a small, 4–8 m tall (15–26 ft tall) evergreen tree native to the deep tropical region of the Americas. Recent genetic studies suggest the most common genotype of the plant originated in the Amazon basin and was gradually transported by humans throughout South and Central America. Early forms of another genotype have also been found in what is now Venezuela. The scientific name, Theobroma, means «food of the gods».[59] The fruit, called a cocoa pod, is ovoid, 15–30 cm (6–12 in) long and 8–10 cm (3–4 in) wide, ripening yellow to orange, and weighing about 500 g (1.1 lb) when ripe.

Cacao trees are small, understory trees that need rich, well-drained soils. They naturally grow within 20° of either side of the equator because they need about 2000 mm of rainfall a year, and temperatures in the range of 21 to 32 °C (70 to 90 °F). Cacao trees cannot tolerate a temperature lower than 15 °C (59 °F).[60]

The three main varieties of cocoa beans used in chocolate are criollo, forastero, and trinitario.

Processing

Cocoa pods are harvested by cutting them from the tree using a machete, or by knocking them off the tree using a stick. It is important to harvest the pods when they are fully ripe, because if the pod is unripe, the beans will have a low cocoa butter content, or low sugar content, reducing the ultimate flavor.

Microbial fermentation

The beans (which are sterile within their pods) and their surrounding pulp are removed from the pods and placed in piles or bins to ferment. Micro-organisms, present naturally in the environment, ferment the pectin-containing material. Yeasts produce ethanol, lactic acid bacteria produce lactic acid, and acetic acid bacteria produce acetic acid. In some cocoa-producing regions an association between filamentous fungi and bacteria (called «cocobiota») acts to produce metabolites beneficial to human health when consumed.[61] The fermentation process, which takes up to seven days, also produces several flavor precursors, that eventually provide the chocolate taste.[62]

After fermentation, the beans must be dried to prevent mold growth. Climate and weather permitting, this is done by spreading the beans out in the sun from five to seven days.[63] In some growing regions (for example, Tobago), the dried beans are then polished for sale by «dancing the cocoa»: spreading the beans onto a floor, adding oil or water, and shuffling the beans against each other using bare feet.[64]

The dried beans are then transported to a chocolate manufacturing facility. The beans are cleaned (removing twigs, stones, and other debris), roasted, and graded. Next, the shell of each bean is removed to extract the nib. The nibs are ground and liquefied, resulting in pure chocolate liquor.[65] The liquor can be further processed into cocoa solids and cocoa butter.[66]

Moist incubation

The beans are dried without fermentation. The nibs are removed and hydrated in an acidic solution. Then they are heated for 72 hours and dried again. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry showed that the incubated chocolate had higher levels of Strecker aldehydes, and lower levels of pyrazines.[67][68]

Blending

Chocolate liquor is blended with the cocoa butter in varying quantities to make different types of chocolate or couverture. The basic blends of ingredients for the various types of chocolate (in order of highest quantity of cocoa liquor first), are:

- Dark chocolate: sugar, cocoa butter, cocoa liquor, and (sometimes) vanilla

- Milk chocolate: sugar, cocoa butter, cocoa liquor, milk or milk powder, and vanilla

- White chocolate: sugar, cocoa butter, milk or milk powder, and vanilla