« previous post | next post »

There’s a joke going around in mainland China about the best way to transcribe the name of the country in Chinese characters. Each line is redolent of some social issue:

the bachelor reads it as qīnǎ 妻哪 = where is my wife? (N.B.: the Chinese term for «bachelor» here is guānggùn 光棍, which may also in some contexts be rendered as «ruffian» and more literally as «bare stick / club»; it refers to unmarried young men who have, already for centuries, been responsible for a disproportionate amount of violence in society, including especially in recent years the knifing of small children at schools; one of the reasons for the hostility demonstrated by guānggùn in Chinese society is the inordinate gender imbalance caused by female infanticide and now in utero sex determination which leads to higher rates of abortion for female fetuses — there simply aren’t enough women to go around)

the playboy reads it as qiènǎ 妾哪 = where is my mistress?

the lover reads it as qīnnǎ 亲哪 = where is my darling?

the poor person reads it as qiánnǎ 钱哪 = where is my money?

the doctor reads it as qiènǎ 切哪 = where to cut?

the official reads it as quánnǎ 权哪 = where is my power?

the real estate developer reads it as quānnǎ 圈哪 = where can I encircle?

the dispossessed reads it as qiānnǎ 迁哪 = where should I move to?

the government reads it as chāinǎ 拆哪 = where should we demolish?

The government reading is said to be both the most apt in terms of meaning and most accurate in terms of sound. When foreign visitors come to China, everywhere they turn they see the character 拆 painted on buildings, including the homes of many people who are still living in them. Puzzled, they ask their translator what this ubiquitous sign means. Whereupon the translator replies, «That’s the name of our country. From ancient times, the name of our country has been CHINA chāi[nǎ] 拆[哪] («demolish; tear down») — demolition is absolutely essential.»

The joke may be funny, but the reality behind it is not. Briefly to address only the problem of chāi («demolish; tear down»), forced demolition without compensation or with inadequate compensation has probably led to more violence in China during recent years than any other single cause. Riots, suicides, bombings — all sorts of unpleasant results can occur when people see their houses being torn down around them, often in the middle of the night and with goon squads accompanying the bulldozers and backhoes.

A final note is that nǎ 哪 («what; which»), which forms the second syllable of all these transcriptions, is an interrogative particle that carries no overt semantic content. The little square (radical 30 [signifying «mouth»] in the traditional Kangxi system) at the left side of the character indicates that the sound it conveys is of more importance than any meaning it may be said to possess. I mention this small grammatical point because it will come up again in my next post.

[A tip of the hat to Sanping Chen and thanks to Gianni Wan]

June 17, 2012 @ 3:48 am

· Filed by Victor Mair under Humor, Transcription

Permalink

Why is “China” called “China”?

Etymology of China Explained

Why is China called China? How did China get its name?

Every country in the world has a story about how it got its name. The etymology of the word “China” stretches back more than 2000 years, to as early as 200 years before Christ.

The name “China” comes from the ancient Chinese Dynasty named “Qin” (秦) [B.C. 221-B.C. 206]. “Qin” (秦) is normally pronounced “Chin” in English. In French, China is spelled “Chine” and pronounced “Sin.” This is where the word “Sin” or “Sino” comes from. In English, it would be proper to pronounce Qin as “Chin.” Therefore, it is clear that the word “China” has its origin in the word “Qin.”

The Qin Dynasty was a dynasty in China that existed during the “Spring and Autumn period” and the Warring States period. In 221, it unified China as a nation for the first time in history.

The period between the unification and the fall of the dynasty is known as the Qin dynasty. The capital of the unified country was Hamyang. The dynasty’s name originated from a place called “Qin,” which had a close relationship with the founder of the dynasty (present Zhangjiachuan Hui autonomous county).

In India, around the 2nd century A.D., China was already being called “China staana” in Sanskrit, meaning “land of the Chinas.” This was a reference to the first unified dynasty, the Qin Dynasty. The land was later introduced to the West as “China” in English and “Chine” in French.

The name Qin might not sound familiar to many people. However, most are familiar with the Great Wall of China. This wall was built by the First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty in 214 B.C. to intercept the invasion of northern tribes such as the Xiongnu. Although it is generally believed that the Great Wall was built by the first emperor, in reality, it was repeatedly rebuilt and relocated by several dynasties. Most of the wall was built in the Ming Dynasty; the existing Ming Dynasty Great Wall line is much farther south than the Qin Dynasty line.

In Chinese, “People’s Republic of China” is written as 中華人民共和国 . 中華 is the Chinese word for China, pronounced Zhōnghuá. The word 中華 means “center of the world.” Usually, China is called 中国(Zhōngguó).

Some people wonder why China is sometimes called “Middle Kingdom” or “Middle Country”. 中 represents the meaning of Center or middle. 國 represents country. Middle country is the direct translation of the word “中國”

Summery:

- Why is it called China? The etymology of China is the ancient Dynasty of “ Qin”.

- The name “China” was introduced to the West through India as early as in 2nd century.

- Qin is originally a name of a place in China associated with the founder of the Dynasty.

Subjects>Jobs & Education>Education

Wiki User

∙ 13y ago

Best Answer

Copy

China means old land and hard work. But you can only use it by

using the beterian Chinese.

The word ‘China’ in Chinese means the ‘MIDDLE COUNTRY’ and is

pronounced as ‘Zhong Guo’,written as ‘中國’.

Wiki User

∙ 13y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What does the word China mean in Chinese?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

China is not called China

The reason why we use the name China in the west for the country is quite surprising. Like many English names for countries it is not the name used within the country itself. This is not uncommon as ‘Greece’ ➚ is known as ‘Hellas’ to the Greeks while ‘Egypt’ ➚ is ‘Misr’ to its people. The name China has been in use for thousands of years and is not easy to trace to its origin. It probably derives from the Sanskrit word ‘Chinasthana’ (meaning country to the East of India) or it might be possibly connected to the Qin (pronounced ‘Chin’) kingdom. The name was in use long before the First Qin Emperor (259 — 210 BCE) came to unify China. The Qin kingdom was the most westerly of the many smaller kingdoms that became China and so would have been the first kingdom reached when traveling overland from India and Central Asia. From ‘Chin’ the Greeks and Romans probably derived the term ‘Sinae’ which you find in words like ‘sinophile’ (someone who likes China) and ‘sinologist’ (someone studying China). In Roman times another name used was ‘Serica’, the land where silk came from. Serica is believed to be derived from the Chinese word for silk 丝 sī pronounced ‘ser’.

Other countries use different names for China following their history of contacts with the country. So ‘Cathay’ (as in Cathay Pacific Airline ➚) is in use in Russia and Central Asia which derives from the name of ‘Qidan’ people who ruled northern China in the 11th century.

China’s name in China — the Middle Kingdom

The Chinese people themselves have several names for their own country. 中国 Zhōng guó is the official one. It means literally middle or central kingdom or region and was based on the traditional view that China is the center of the civilized world surrounded by barbarians. The modern form of guo 国 has the character for the precious treasure jade 玉 enclosed within a boundary. The old version of guo was 國 which had a spear and mouth inside an enclosure, suggesting a person proclaiming ownership of an area.

Throughout dynastic history the formal name included the dynastic name so during the last Qing dynasty the country was 大清国 Dà qīng guó ‘Great Qing Kingdom’ and during the Ming dynasty 大明国 Dà míng guó ‘Great Ming Kingdom’.

Hua 华 was a name used by the early Han people, and this is used to refer to China as in 新华 Xinhua News agency. Unfortunately huá 华 is very similar to 花 huā meaning ‘flower’ and so from a misleading translation China was sometimes referred to as the ‘Flowery land’ in the 19th century. Central China and in particular the province of Hunan used to be called Zhonghuadi 中华地. Some westerners translated this as ‘Central flowery land’ rather than ‘Central splendid land’.

中华民国 Zhonghua Minguo refers to ‘The Republic of China’ (1912-1949) and still used in Chinese Taipei (Taiwan) while the full title

中华人民共和国 zhōng huá rén mín gòng hé guó Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo, refers to ‘The People’s Republic of China’. There are many other names that have been used over the years. One of the earliest hints of a china-centric view of the world comes from

天下 Tiān xià meaning all under heaven or our land. Much is made of this in the epic film Hero ➚ set at the end of the Warring States period. Another early name for China is 华夏 huá xià. There is also the name 九洲 Jiǔ zhōu Nine Regions as Yu the Great originally divided the land into nine regions. Somewhat more recently the term eighteen provinces 十八省 shí bā shěng has been used (there are actually 33 administrative regions).

神洲 Shén zhōu Divine Region is a poetic name for the country while more informally you may come across 祖国 zǔ guó, the fatherland, or simply 我国 wǒ guó, my country. Emphasizing the feeling of a single community there is also 国家 guó jiā or home country as jia means home or family.

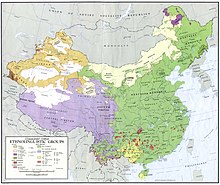

With 92% of the Chinese population categorized as 汉

Han Chinese, the term ‘Han’, named after the Han dynasty, is also used to refer to China as a whole even though it rather excludes the many ethnic minorities. During Han dynasty times the rough geographic limits of the modern Chinese nation had already been set.

Name for the Chinese Language

Just as varied are the words used to refer to the language of the Chinese people. First of all there are several languages and many dialects spoken in China, there is no universal ‘Chinese’. The official and most widely used dialect of the Chinese language is that used in Beijing. Its historical association with the Imperial court has led to the term ‘Mandarin’ being used for the language, after the ‘mandarin’ officials who spoke it. ‘Mandarin’ was a term used by the Portuguese for the officials, it is now believed to be derived from a Malay word for ‘counselor’ or ‘minister’ (reflecting early contacts in the spice trade) which in turn shares its origin with the word ‘mantra’.

In China the official name for the language is 普通话 Pǔ tōng huà common speech. Reflecting the historical origin of the language of the Han people it is also known as 汉语 hàn yǔ. Other names include the name for China, so you will also hear 中文 zhōng wén where wen refers to the common written script rather than the spoken tongue which is 中国话 zhōng guó huà.

«People’s Republic of China» redirects here. For the Republic of China, see Taiwan.

|

People’s Republic of China 中华人民共和国 (Chinese) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag National Emblem |

|

| Anthem: 义勇军进行曲 Yìyǒngjūn Jìnxíngqǔ «March of the Volunteers» |

|

Territory controlled by the People’s Republic of China is shown in dark green; territory claimed but not controlled is shown in light green. |

|

| Capital | Beijing 39°55′N 116°23′E / 39.917°N 116.383°E |

| Largest city by population |

Shanghai |

| Official languages | Standard Chinese[a] |

| Recognized regional languages |

|

| Official script | Simplified Chinese[b] |

| Ethnic groups

(2020)[1] |

|

| Religion

(2020)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Chinese |

| Government | Unitary Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic |

|

• CCP General Secretary[c] |

Xi Jinping |

|

• Premier |

Li Qiang |

|

• Congress Chairman |

Zhao Leji |

|

• CPPCC Chairman[f] |

Wang Huning |

| Legislature | National People’s Congress |

| Formation | |

|

• First pre-imperial dynasty |

c. 2070 BCE |

|

• First imperial dynasty |

221 BCE |

|

• Republic established |

1 January 1912 |

|

• Proclamation of the People’s Republic |

1 October 1949 |

|

• First constitution |

20 September 1954 |

|

• Current constitution |

4 December 1982 |

|

• Most recent polity admitted |

20 December 1999 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

9,596,961 km2 (3,705,407 sq mi)[g][5] (3rd / 4th) |

|

• Water (%) |

2.8[h] |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

|

|

• 2020 census |

1,411,778,724[8] (1st) |

|

• Density |

145[9]/km2 (375.5/sq mi) (83rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2019) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | high · 79th |

| Currency | Renminbi (元/¥)[j] (CNY) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (CST) |

| DST is not observed | |

| Date format |

|

| Driving side | right (Mainland) left (Hong Kong and Macau) |

| Calling code | +86 (Mainland) +852 (Hong Kong) +853 (Macau) |

| ISO 3166 code | CN |

| Internet TLD |

|

China (Chinese: 中国; pinyin: Zhōngguó), officially the People’s Republic of China (PRC),[k] is a country in East Asia. It is the world’s most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and borders fourteen countries by land,[l] the most of any country in the world, tied with Russia. With an area of approximately 9.6 million square kilometres (3,700,000 sq mi), it is the world’s third largest country by total land area.[m] The country consists of 22 provinces,[n] five autonomous regions, four municipalities, and two special administrative regions (Hong Kong and Macau). The national capital is Beijing, and the most populous city and largest financial center is Shanghai.

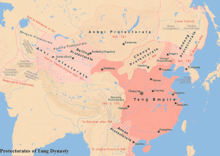

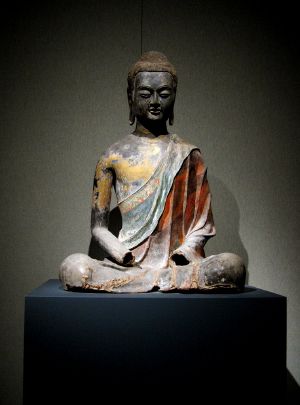

Modern Chinese trace their origins to a cradle of civilization in the fertile basin of the Yellow River in the North China Plain. The semi-legendary Xia dynasty in the 21st century BCE and the well-attested Shang and Zhou dynasties developed a bureaucratic political system to serve hereditary monarchies, or dynasties. Chinese writing, Chinese classic literature, and the Hundred Schools of Thought emerged during this period and influenced China and its neighbors for centuries to come. In the third century BCE, Qin Shi Huang founded the first Chinese empire, the short-lived Qin dynasty. The Qin was followed by the more stable Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), which established a model for nearly two millennia in which the Chinese empire was one of the world’s foremost economic powers. The empire expanded, fractured, and reunified; was conquered and reestablished; absorbed foreign religions and ideas; and made world-leading scientific advances, such as the Four Great Inventions: gunpowder, paper, the compass, and printing. After centuries of disunity following the fall of the Han, the Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties reunified the empire. The multi-ethnic Tang welcomed foreign trade and culture that came over the Silk Road and adapted Buddhism to Chinese needs. The early modern Song dynasty (960–1279) became increasingly urban and commercial. The civilian scholar-officials or literati used the examination system and the doctrines of Neo-Confucianism to replace the military aristocrats of earlier dynasties. The Mongol invasion established the Yuan dynasty in 1279, but the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) re-established Han Chinese control. The Manchu-led Qing dynasty nearly doubled the empire’s territory and established a multi-ethnic state that was the basis of the modern Chinese nation, but suffered heavy losses to foreign imperialism in the 19th century.

The Chinese monarchy collapsed in 1912 with the Xinhai Revolution, when the Republic of China (ROC) replaced the Qing dynasty. In its early years as a republic, the country underwent a period of instability known as the Warlord Era before mostly reunifying in 1928 under a Nationalist government. A civil war between the nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) began in 1927. Japan invaded China in 1937, starting the Second Sino-Japanese War and temporarily halting the civil war. The surrender and expulsion of Japanese forces from China in 1945 left a power vacuum in the country, which led to renewed fighting between the CCP and the Kuomintang. The civil war ended in 1949[o] with the division of Chinese territory; the CCP established the People’s Republic of China on the mainland while the Kuomintang-led ROC government retreated to the island of Taiwan.[p] Both claim to be the sole legitimate government of China, although the United Nations has recognized the PRC as the sole representation since 1971. From 1959 to 1961, the PRC implemented an economic and social campaign called the «Great Leap Forward» that resulted in a sharp economic decline and an estimated 15 to 55 million deaths, mostly through human-made famine. From 1966 to 1976, the turbulent period of political and social chaos within China known as the Cultural Revolution led to greater economic and educational decline, with millions being purged or subjected to either persecution or «politicide» based on political categories. Since then, the Chinese government has rebuked some of the earlier Maoist policies, conducting a series of political and economic reforms since 1978 that have greatly raised Chinese standards of living, and increased life expectancies.

China is currently governed as a unitary Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic by the CCP. China is a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council and a founding member of several multilateral and regional cooperation organizations such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Silk Road Fund, the New Development Bank, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and the RCEP. It is also a member of the BRICS, the G8+5, the G20, the APEC, and the East Asia Summit. Making up around one-fifth of the world economy, China is the world’s largest economy by GDP at purchasing power parity, the second-largest economy by nominal GDP, and the second-wealthiest country. The country is one of the fastest-growing major economies and is the world’s largest manufacturer and exporter, as well as the second-largest importer. China is a recognized nuclear-weapon state with the world’s largest standing army by military personnel and the second-largest defense budget. China ranks poorly in measures of democracy, transparency, press freedom, religious freedom, and ethnic equality. The Chinese authorities have been criticized by human rights activists and non-governmental organizations for human rights abuses, including mass censorship, mass surveillance, and suppression of dissent.

Etymology

The word «China» has been used in English since the 16th century; however, it was not a word used by the Chinese themselves during this period. Its origin has been traced through Portuguese, Malay, and Persian back to the Sanskrit word Cīna, used in ancient India.[18] «China» appears in Richard Eden’s 1555 translation[q] of the 1516 journal of the Portuguese explorer Duarte Barbosa.[r][18] Barbosa’s usage was derived from Persian Chīn (چین), which was in turn derived from Sanskrit Cīna (चीन).[23] Cīna was first used in early Hindu scripture, including the Mahābhārata (5th century BCE) and the Laws of Manu (2nd century BCE).[24] In 1655, Martino Martini suggested that the word China is derived ultimately from the name of the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE).[25][24] Although usage in Indian sources precedes this dynasty, this derivation is still given in various sources.[26] The origin of the Sanskrit word is a matter of debate, according to the Oxford English Dictionary.[18]

Alternative suggestions include the names for Yelang and the Jing or Chu state.[24][27]

The official name of the modern state is the «People’s Republic of China» (simplified Chinese: 中华人民共和国; traditional Chinese: 中華人民共和國; pinyin: Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó). The shorter form is «China» Zhōngguó (中国; 中國) from zhōng («central») and guó («state»),[s] a term which developed under the Western Zhou dynasty in reference to its royal demesne.[t][u] It was then applied to the area around Luoyi (present-day Luoyang) during the Eastern Zhou and then to China’s Central Plain before being used as an occasional synonym for the state under the Qing.[29] It was often used as a cultural concept to distinguish the Huaxia people from perceived «barbarians».[29] The name Zhongguo is also translated as «Middle Kingdom» in English.[32] China (PRC) is sometimes referred to as the Mainland when distinguishing the ROC from the PRC.[33][34][35][36]

History

Prehistory

10,000-year-old pottery, Xianren Cave culture (18000–7000 BCE)

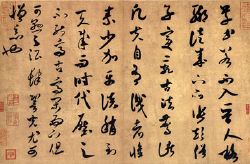

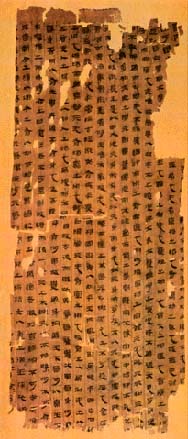

China is regarded as one of the world’s oldest civilisations.[37][38] Archaeological evidence suggests that early hominids inhabited the country 2.25 million years ago.[39] The hominid fossils of Peking Man, a Homo erectus who used fire,[40] were discovered in a cave at Zhoukoudian near Beijing; they have been dated to between 680,000 and 780,000 years ago.[41] The fossilized teeth of Homo sapiens (dated to 125,000–80,000 years ago) have been discovered in Fuyan Cave in Dao County, Hunan.[42] Chinese proto-writing existed in Jiahu around 6600 BCE,[43] at Damaidi around 6000 BCE,[44] Dadiwan from 5800 to 5400 BCE, and Banpo dating from the 5th millennium BCE. Some scholars have suggested that the Jiahu symbols (7th millennium BCE) constituted the earliest Chinese writing system.[43]

Early dynastic rule

According to Chinese tradition, the first dynasty was the Xia, which emerged around 2100 BCE.[45] The Xia dynasty marked the beginning of China’s political system based on hereditary monarchies, or dynasties, which lasted for a millennium.[46] The Xia dynasty was considered mythical by historians until scientific excavations found early Bronze Age sites at Erlitou, Henan in 1959.[47] It remains unclear whether these sites are the remains of the Xia dynasty or of another culture from the same period.[48] The succeeding Shang dynasty is the earliest to be confirmed by contemporary records.[49] The Shang ruled the plain of the Yellow River in eastern China from the 17th to the 11th century BCE.[50] Their oracle bone script (from c. 1500 BCE)[51][52] represents the oldest form of Chinese writing yet found[53] and is a direct ancestor of modern Chinese characters.[54]

The Shang was conquered by the Zhou, who ruled between the 11th and 5th centuries BCE, though centralized authority was slowly eroded by feudal warlords. Some principalities eventually emerged from the weakened Zhou, no longer fully obeyed the Zhou king, and continually waged war with each other during the 300-year Spring and Autumn period. By the time of the Warring States period of the 5th–3rd centuries BCE, there were only seven powerful states left.[55]

Imperial China

The Warring States period ended in 221 BCE after the state of Qin conquered the other six kingdoms, reunited China and established the dominant order of autocracy. King Zheng of Qin proclaimed himself the First Emperor of the Qin dynasty. He enacted Qin’s legalist reforms throughout China, notably the forced standardization of Chinese characters, measurements, road widths (i.e., the cart axles’ length), and currency. His dynasty also conquered the Yue tribes in Guangxi, Guangdong, and Vietnam.[56] The Qin dynasty lasted only fifteen years, falling soon after the First Emperor’s death, as his harsh authoritarian policies led to widespread rebellion.[57][58]

Following a widespread civil war during which the imperial library at Xianyang was burned,[v] the Han dynasty emerged to rule China between 206 BCE and CE 220, creating a cultural identity among its populace still remembered in the ethnonym of the Han Chinese.[57][58] The Han expanded the empire’s territory considerably, with military campaigns reaching Central Asia, Mongolia, South Korea, and Yunnan, and the recovery of Guangdong and northern Vietnam from Nanyue. Han involvement in Central Asia and Sogdia helped establish the land route of the Silk Road, replacing the earlier path over the Himalayas to India. Han China gradually became the largest economy of the ancient world.[60] Despite the Han’s initial decentralization and the official abandonment of the Qin philosophy of Legalism in favor of Confucianism, Qin’s legalist institutions and policies continued to be employed by the Han government and its successors.[61]

Map showing the expansion of Han dynasty in the 2nd century BC

After the end of the Han dynasty, a period of strife known as Three Kingdoms followed,[62] whose central figures were later immortalized in one of the Four Classics of Chinese literature. At its end, Wei was swiftly overthrown by the Jin dynasty. The Jin fell to civil war upon the ascension of a developmentally disabled emperor; the Five Barbarians then invaded and ruled northern China as the Sixteen States. The Xianbei unified them as the Northern Wei, whose Emperor Xiaowen reversed his predecessors’ apartheid policies and enforced a drastic sinification on his subjects, largely integrating them into Chinese culture. In the south, the general Liu Yu secured the abdication of the Jin in favor of the Liu Song. The various successors of these states became known as the Northern and Southern dynasties, with the two areas finally reunited by the Sui in 581. The Sui restored the Han to power through China, reformed its agriculture, economy and imperial examination system, constructed the Grand Canal, and patronized Buddhism. However, they fell quickly when their conscription for public works and a failed war in northern Korea provoked widespread unrest.[63][64]

Under the succeeding Tang and Song dynasties, Chinese economy, technology, and culture entered a golden age.[65] The Tang dynasty retained control of the Western Regions and the Silk Road,[66] which brought traders to as far as Mesopotamia and the Horn of Africa,[67] and made the capital Chang’an a cosmopolitan urban center. However, it was devastated and weakened by the An Lushan Rebellion in the 8th century.[68] In 907, the Tang disintegrated completely when the local military governors became ungovernable. The Song dynasty ended the separatist situation in 960, leading to a balance of power between the Song and Khitan Liao. The Song was the first government in world history to issue paper money and the first Chinese polity to establish a permanent standing navy which was supported by the developed shipbuilding industry along with the sea trade.[69]

Between the 10th and 11th centuries, the population of China doubled in size to around 100 million people, mostly because of the expansion of rice cultivation in central and southern China, and the production of abundant food surpluses. The Song dynasty also saw a revival of Confucianism, in response to the growth of Buddhism during the Tang,[70] and a flourishing of philosophy and the arts, as landscape art and porcelain were brought to new levels of maturity and complexity.[71][72] However, the military weakness of the Song army was observed by the Jurchen Jin dynasty. In 1127, Emperor Huizong of Song and the capital Bianjing were captured during the Jin–Song Wars. The remnants of the Song retreated to southern China.[73]

The Mongol conquest of China began in 1205 with the gradual conquest of Western Xia by Genghis Khan,[74] who also invaded Jin territories.[75] In 1271, the Mongol leader Kublai Khan established the Yuan dynasty, which conquered the last remnant of the Song dynasty in 1279. Before the Mongol invasion, the population of Song China was 120 million citizens; this was reduced to 60 million by the time of the census in 1300.[76] A peasant named Zhu Yuanzhang led a rebellion that overthrew the Yuan in 1368 and founded the Ming dynasty as the Hongwu Emperor. Under the Ming dynasty, China enjoyed another golden age, developing one of the strongest navies in the world and a rich and prosperous economy amid a flourishing of art and culture. It was during this period that admiral Zheng He led the Ming treasure voyages throughout the Indian Ocean, reaching as far as East Africa.[77]

In the early years of the Ming dynasty, China’s capital was moved from Nanjing to Beijing. With the budding of capitalism, philosophers such as Wang Yangming further critiqued and expanded Neo-Confucianism with concepts of individualism and equality of four occupations.[78] The scholar-official stratum became a supporting force of industry and commerce in the tax boycott movements, which, together with the famines and defense against Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598) and Manchu invasions led to an exhausted treasury.[79] In 1644, Beijing was captured by a coalition of peasant rebel forces led by Li Zicheng. The Chongzhen Emperor committed suicide when the city fell. The Manchu Qing dynasty, then allied with Ming dynasty general Wu Sangui, overthrew Li’s short-lived Shun dynasty and subsequently seized control of Beijing, which became the new capital of the Qing dynasty.[80]

The Qing dynasty, which lasted from 1644 until 1912, was the last imperial dynasty of China. Its conquest of the Ming (1618–1683) cost 25 million lives and the economy of China shrank drastically.[81] After the Southern Ming ended, the further conquest of the Dzungar Khanate added Mongolia, Tibet and Xinjiang to the empire.[82] The centralized autocracy was strengthened to suppress anti-Qing sentiment with the policy of valuing agriculture and restraining commerce, the Haijin («sea ban»), and ideological control as represented by the literary inquisition, causing social and technological stagnation.[83][84]

Fall of the Qing dynasty

In the mid-19th century, the Qing dynasty experienced Western imperialism in the Opium Wars with Britain and France. China was forced to pay compensation, open treaty ports, allow extraterritoriality for foreign nationals, and cede Hong Kong to the British[85] under the 1842 Treaty of Nanking, the first of the Unequal Treaties. The First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) resulted in Qing China’s loss of influence in the Korean Peninsula, as well as the cession of Taiwan to Japan.[86]

The Qing dynasty also began experiencing internal unrest in which tens of millions of people died, especially in the White Lotus Rebellion, the failed Taiping Rebellion that ravaged southern China in the 1850s and 1860s and the Dungan Revolt (1862–1877) in the northwest. The initial success of the Self-Strengthening Movement of the 1860s was frustrated by a series of military defeats in the 1880s and 1890s.[citation needed]

In the 19th century, the great Chinese diaspora began. Losses due to emigration were added to by conflicts and catastrophes such as the Northern Chinese Famine of 1876–1879, in which between 9 and 13 million people died.[87] The Guangxu Emperor drafted a reform plan in 1898 to establish a modern constitutional monarchy, but these plans were thwarted by the Empress Dowager Cixi. The ill-fated anti-foreign Boxer Rebellion of 1899–1901 further weakened the dynasty. Although Cixi sponsored a program of reforms, the Xinhai Revolution of 1911–1912 brought an end to the Qing dynasty and established the Republic of China.[88] Puyi, the last Emperor of China, abdicated in 1912.[89]

Establishment of the Republic and World War II

On 1 January 1912, the Republic of China was established, and Sun Yat-sen of the Kuomintang (the KMT or Nationalist Party) was proclaimed provisional president.[90] On 12 February 1912, regent Empress Dowager Longyu sealed the imperial abdication decree on behalf of 4 year old Puyi, the last emperor of China, ending 5,000 years of monarchy in China.[91] In March 1912, the presidency was given to Yuan Shikai, a former Qing general who in 1915 proclaimed himself Emperor of China. In the face of popular condemnation and opposition from his own Beiyang Army, he was forced to abdicate and re-establish the republic in 1916.[92]

After Yuan Shikai’s death in 1916, China was politically fragmented. Its Beijing-based government was internationally recognized but virtually powerless; regional warlords controlled most of its territory.[93][94] In the late 1920s, the Kuomintang under Chiang Kai-shek, the then Principal of the Republic of China Military Academy, was able to reunify the country under its own control with a series of deft military and political maneuverings, known collectively as the Northern Expedition.[95][96] The Kuomintang moved the nation’s capital to Nanjing and implemented «political tutelage», an intermediate stage of political development outlined in Sun Yat-sen’s San-min program for transforming China into a modern democratic state.[97][98] The political division in China made it difficult for Chiang to battle the communist-led People’s Liberation Army (PLA), against whom the Kuomintang had been warring since 1927 in the Chinese Civil War. This war continued successfully for the Kuomintang, especially after the PLA retreated in the Long March, until Japanese aggression and the 1936 Xi’an Incident forced Chiang to confront Imperial Japan.[99]

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), a theater of World War II, forced an uneasy alliance between the Kuomintang and the Communists. Japanese forces committed numerous war atrocities against the civilian population; in all, as many as 20 million Chinese civilians died.[100] An estimated 40,000 to 300,000 Chinese were massacred in the city of Nanjing alone during the Japanese occupation.[101] During the war, China, along with the UK, the United States, and the Soviet Union, were referred to as «trusteeship of the powerful»[102] and were recognized as the Allied «Big Four» in the Declaration by United Nations.[103][104] Along with the other three great powers, China was one of the four major Allies of World War II, and was later considered one of the primary victors in the war.[105][106] After the surrender of Japan in 1945, Taiwan, including the Pescadores, was handed over to Chinese control. However, the validity of this handover is controversial, in that whether Taiwan’s sovereignty was legally transferred and whether China is a legitimate recipient, due to complex issues that arose from the handling of Japan’s surrender, resulting in the unresolved political status of Taiwan, which is a flashpoint of potential war between China and Taiwan. China emerged victorious but war-ravaged and financially drained. The continued distrust between the Kuomintang and the Communists led to the resumption of civil war. Constitutional rule was established in 1947, but because of the ongoing unrest, many provisions of the ROC constitution were never implemented in mainland China.[107]

Civil War and the People’s Republic

Before the existence of the People’s Republic, the CCP had declared several areas of the country as the Chinese Soviet Republic (Jiangxi Soviet), a predecessor state to the PRC, in November 1931 in Ruijin, Jiangxi. The Jiangxi Soviet was wiped out by the KMT armies in 1934 and was relocated to Yan’an in Shaanxi where the Long March concluded in 1935.[108][failed verification] It would be the base of the communists before major combat in the Chinese Civil War ended in 1949. Afterwards, the CCP took control of most of mainland China, and the Kuomintang retreating offshore to Taiwan, reducing its territory to only Taiwan, Hainan, and their surrounding islands.

On 1 October 1949, CCP Chairman Mao Zedong formally proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic of China at the new nation’s founding ceremony and inaugural military parade in Tiananmen Square, Beijing.[110][111] In 1950, the People’s Liberation Army captured Hainan from the ROC[112] and annexed Tibet.[113] However, remaining Kuomintang forces continued to wage an insurgency in western China throughout the 1950s.[114]

The government consolidated its popularity among the peasants through land reform, which included the execution of between 1 and 2 million landlords.[115] China developed an independent industrial system and its own nuclear weapons.[116] The Chinese population increased from 550 million in 1950 to 900 million in 1974.[117] However, the Great Leap Forward, an idealistic massive reform project, resulted in an estimated 15 to 55 million deaths between 1959 and 1961, mostly from starvation.[118][119] In 1964, China’s first atomic bomb exploded successfully.[120] In 1966, Mao and his allies launched the Cultural Revolution, sparking a decade of political recrimination and social upheaval that lasted until Mao’s death in 1976. In October 1971, the PRC replaced the Republic of China in the United Nations, and took its seat as a permanent member of the Security Council.[121] This UN action also created the problem of the political status of Taiwan and the Two Chinas issue.

Reforms and contemporary history

The 1989 Tiananmen Square protests was ended by a military-led massacre which brought condemnations and sanctions against the Chinese government from various foreign countries.

After Mao’s death, the Gang of Four was quickly arrested by Hua Guofeng and held responsible for the excesses of the Cultural Revolution. Deng Xiaoping took power in 1978, and instituted significant economic reforms. The CCP loosened governmental control over citizens’ personal lives, and the communes were gradually disbanded in favor of working contracted to households. Agricultural collectivization was dismantled and farmlands privatized, while foreign trade became a major new focus, leading to the creation of Special Economic Zones (SEZs). Inefficient state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were restructured and unprofitable ones were closed outright, resulting in massive job losses.[citation needed] This marked China’s transition from a planned economy to a mixed economy with an increasingly open-market environment.[122] China adopted its current constitution on 4 December 1982. In 1989, the suppression of student protests in Tiananmen Square brought condemnations and sanctions against the Chinese government from various foreign countries.[123]

Jiang Zemin, Li Peng and Zhu Rongji led the nation in the 1990s. Under their administration, China’s economic performance pulled an estimated[by whom?] 150 million peasants out of poverty and sustained an average annual gross domestic product growth rate of 11.2%.[124][better source needed] British Hong Kong and Portuguese Macau returned to China in 1997 and 1999, respectively, as the Hong Kong and Macau special administrative regions under the principle of One country, two systems. The country joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, and maintained its high rate of economic growth under Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao’s leadership in the 2000s. However, the growth also severely impacted the country’s resources and environment,[125][126] and caused major social displacement.[127][128]

CCP general secretary Xi Jinping has ruled since 2012 and has pursued large-scale efforts to reform China’s economy,[129][130] which has suffered from structural instabilities and slowing growth,[131][132][133] and has also reformed the one-child policy and penal system,[134] as well as instituting a vast anti-corruption crackdown.[135] In the early 2010s, China’s economic growth rate began to slow amid domestic credit troubles, weakening international demand for Chinese exports and fragility in the global economy.[136][137][138] In 2013, China initiated the Belt and Road Initiative, a global infrastructure investment project.[139] Since 2017, the Chinese government has been engaged in a harsh crackdown in Xinjiang, with an estimated one million people, mostly Uyghurs but including other ethnic and religious minorities, in internment camps.[140] The National People’s Congress in 2018 altered the country’s constitution to remove the two-term limit on holding the Presidency of China, permitting the current leader, Xi Jinping, to remain president of China (and general secretary of the CCP) for an unlimited time, earning criticism for creating dictatorial governance.[141][142] In 2020, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPCSC) passed a national security law in Hong Kong that gave the Hong Kong government wide-ranging tools to crack down on dissent.[143] In December 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic began with an outbreak in Wuhan; after three years of strict public health measures indented to completely eradicate the virus, mounting social and economic pressures compelled the government to loosen restrictions in December 2022.

Geography

China topographic map with East Asia countries

China’s landscape is vast and diverse, ranging from the Gobi and Taklamakan Deserts in the arid north to the subtropical forests in the wetter south. The Himalaya, Karakoram, Pamir and Tian Shan mountain ranges separate China from much of South and Central Asia. The Yangtze and Yellow Rivers, the third- and sixth-longest in the world, respectively, run from the Tibetan Plateau to the densely populated eastern seaboard. China’s coastline along the Pacific Ocean is 14,500 km (9,000 mi) long and is bounded by the Bohai, Yellow, East China and South China seas. China connects through the Kazakh border to the Eurasian Steppe which has been an artery of communication between East and West since the Neolithic through the Steppe Route – the ancestor of the terrestrial Silk Road(s).[citation needed]

The territory of China lies between latitudes 18° and 54° N, and longitudes 73° and 135° E. The geographical center of China is marked by the Center of the Country Monument at 35°50′40.9″N 103°27′7.5″E / 35.844694°N 103.452083°E. China’s landscapes vary significantly across its vast territory. In the east, along the shores of the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea, there are extensive and densely populated alluvial plains, while on the edges of the Inner Mongolian plateau in the north, broad grasslands predominate. Southern China is dominated by hills and low mountain ranges, while the central-east hosts the deltas of China’s two major rivers, the Yellow River and the Yangtze River. Other major rivers include the Xi, Mekong, Brahmaputra and Amur. To the west sit major mountain ranges, most notably the Himalayas. High plateaus feature among the more arid landscapes of the north, such as the Taklamakan and the Gobi Desert. The world’s highest point, Mount Everest (8,848 m), lies on the Sino-Nepalese border.[144] The country’s lowest point, and the world’s third-lowest, is the dried lake bed of Ayding Lake (−154 m) in the Turpan Depression.[145]

Climate

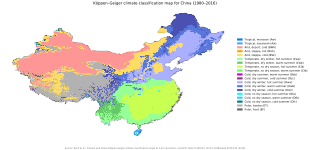

China’s climate is mainly dominated by dry seasons and wet monsoons, which lead to pronounced temperature differences between winter and summer. In the winter, northern winds coming from high-latitude areas are cold and dry; in summer, southern winds from coastal areas at lower latitudes are warm and moist.[147]

A major environmental issue in China is the continued expansion of its deserts, particularly the Gobi Desert.[148][149] Although barrier tree lines planted since the 1970s have reduced the frequency of sandstorms, prolonged drought and poor agricultural practices have resulted in dust storms plaguing northern China each spring, which then spread to other parts of East Asia, including Japan and Korea. China’s environmental watchdog, SEPA, stated in 2007 that China is losing 4,000 km2 (1,500 sq mi) per year to desertification.[150] Water quality, erosion, and pollution control have become important issues in China’s relations with other countries. Melting glaciers in the Himalayas could potentially lead to water shortages for hundreds of millions of people.[151] According to academics, in order to limit climate change in China to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) electricity generation from coal in China without carbon capture must be phased out by 2045.[152] Official government statistics about Chinese agricultural productivity are considered unreliable, due to exaggeration of production at subsidiary government levels.[153][154] Much of China has a climate very suitable for agriculture and the country has been the world’s largest producer of rice, wheat, tomatoes, eggplant, grapes, watermelon, spinach, and many other crops.[155]

Biodiversity

China is one of 17 megadiverse countries,[156] lying in two of the world’s major biogeographic realms: the Palearctic and the Indomalayan. By one measure, China has over 34,687 species of animals and vascular plants, making it the third-most biodiverse country in the world, after Brazil and Colombia.[157] The country signed the Rio de Janeiro Convention on Biological Diversity on 11 June 1992, and became a party to the convention on 5 January 1993.[158] It later produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, with one revision that was received by the convention on 21 September 2010.[159]

China is home to at least 551 species of mammals (the third-highest such number in the world),[160] 1,221 species of birds (eighth),[161] 424 species of reptiles (seventh)[162] and 333 species of amphibians (seventh).[163] Wildlife in China shares habitat with, and bears acute pressure from, the world’s largest population of humans. At least 840 animal species are threatened, vulnerable or in danger of local extinction in China, due mainly to human activity such as habitat destruction, pollution and poaching for food, fur and ingredients for traditional Chinese medicine.[164] Endangered wildlife is protected by law, and as of 2005, the country has over 2,349 nature reserves, covering a total area of 149.95 million hectares, 15 percent of China’s total land area.[165][better source needed] Most wild animals have been eliminated from the core agricultural regions of east and central China, but they have fared better in the mountainous south and west.[166][167] The Baiji was confirmed extinct on 12 December 2006.[168]

China has over 32,000 species of vascular plants,[169] and is home to a variety of forest types. Cold coniferous forests predominate in the north of the country, supporting animal species such as moose and Asian black bear, along with over 120 bird species.[170] The understory of moist conifer forests may contain thickets of bamboo. In higher montane stands of juniper and yew, the bamboo is replaced by rhododendrons. Subtropical forests, which are predominate in central and southern China, support a high density of plant species including numerous rare endemics. Tropical and seasonal rainforests, though confined to Yunnan and Hainan Island, contain a quarter of all the animal and plant species found in China.[170] China has over 10,000 recorded species of fungi,[171] and of them, nearly 6,000 are higher fungi.

Environment

In the early 2000s, China has suffered from environmental deterioration and pollution due to its rapid pace of industrialization.[172][173] While regulations such as the 1979 Environmental Protection Law are fairly stringent, they are poorly enforced, as they are frequently disregarded by local communities and government officials in favor of rapid economic development.[174] China is the country with the second highest death toll because of air pollution, after India. There are approximately 1 million deaths caused by exposure to ambient air pollution.[175][176] Although China ranks as the highest CO2 emitting country in the world,[177] it only emits 8 tons of CO2 per capita, significantly lower than developed countries such as the United States (16.1), Australia (16.8) and South Korea (13.6).[178]

In recent years, China has clamped down on pollution. In March 2014, CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping «declared war» on pollution during the opening of the National People’s Congress.[179] After extensive debate lasting nearly two years, the parliament approved a new environmental law in April. The new law empowers environmental enforcement agencies with great punitive power and large fines for offenders, defines areas which require extra protection, and gives independent environmental groups more ability to operate in the country.[citation needed] In 2020, Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping announced that China aims to peak emissions before 2030 and go carbon-neutral by 2060 in accordance with the Paris climate accord.[180] According to Climate Action Tracker, if accomplished it would lower the expected rise in global temperature by 0.2 – 0.3 degrees – «the biggest single reduction ever estimated by the Climate Action Tracker».[181] In September 2021 Xi Jinping announced that China will not build «coal-fired power projects abroad». The decision can be «pivotal» in reducing emissions. The Belt and Road Initiative did not include financing such projects already in the first half of 2021.[182]

The country also had significant water pollution problems: 8.2% of China’s rivers had been polluted by industrial and agricultural waste in 2019.[183][184] China had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.14/10, ranking it 53rd globally out of 172 countries.[185] In 2020, a sweeping law was passed by the Chinese government to protect the ecology of the Yangtze River. The new laws include strengthening ecological protection rules for hydropower projects along the river, banning chemical plants within 1 kilometer of the river, relocating polluting industries, severely restricting sand mining as well as a complete fishing ban on all the natural waterways of the river, including all its major tributaries and lakes.[186]

China is also the world’s leading investor in renewable energy and its commercialization, with $52 billion invested in 2011 alone;[187][188][189] it is a major manufacturer of renewable energy technologies and invests heavily in local-scale renewable energy projects.[190][191][192] By 2015, over 24% of China’s energy was derived from renewable sources, while most notably from hydroelectric power: a total installed capacity of 197 GW makes China the largest hydroelectric power producer in the world.[193][194] China also has the largest power capacity of installed solar photovoltaics system and wind power system in the world.[195][196] Greenhouse gas emissions by China are the world’s largest,[178] as is renewable energy in China.[197] Despite its emphasis on renewables, China remains deeply connected to global oil markets and next to India, has been the largest importer of Russian crude oil in 2022.[198][199]

Political geography

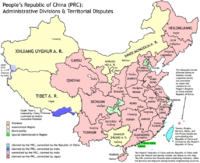

Map showing the territorial claims of the PRC

The People’s Republic of China is the second-largest country in the world by land area after Russia.[w][x] China’s total area is generally stated as being approximately 9,600,000 km2 (3,700,000 sq mi).[200] Specific area figures range from 9,572,900 km2 (3,696,100 sq mi) according to the Encyclopædia Britannica,[201] to 9,596,961 km2 (3,705,407 sq mi) according to the UN Demographic Yearbook,[3] and the CIA World Factbook.[6]

China has the longest combined land border in the world, measuring 22,117 km (13,743 mi) and its coastline covers approximately 14,500 km (9,000 mi) from the mouth of the Yalu River (Amnok River) to the Gulf of Tonkin.[6] China borders 14 nations and covers the bulk of East Asia, bordering Vietnam, Laos, and Myanmar in Southeast Asia; India, Bhutan, Nepal, Afghanistan, and Pakistan[y] in South Asia; Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan in Central Asia; and Russia, Mongolia, and North Korea in Inner Asia and Northeast Asia. It is narrowly separated from Bangladesh and Thailand to the southwest and south, and has several maritime neighbors such as Japan, Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia.[202]

Politics

The People’s Republic of China is a one-party Marxist–Leninist state[203] governed solely by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), making it one of the world’s last countries governed by a communist party. The Chinese constitution states that the PRC «is a socialist state governed by a people’s democratic dictatorship that is led by the working class and based on an alliance of workers and peasants,» and that the state institutions «shall practice the principle of democratic centralism.»[204] The main body of the constitution also declares that «the defining feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics is the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).»[205]

Although the CCP describes China as a «socialist consultative democracy»,[206] the country is commonly described as an authoritarian one-party surveillance state and a dictatorship.[207][208] China has consistently been ranked amongst the lowest as an «authoritarian regime» by the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index, ranking at 156th out of 167 countries in 2022.[209] It has also been called authoritarian[210] and corporatist,[211] with amongst the heaviest restrictions worldwide in many areas, most notably against free access to the Internet, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, the right to have children, free formation of social organizations and freedom of religion.[212] Its current political, ideological and economic system has been termed by its leaders as a «whole-process people’s democracy» «people’s democratic dictatorship», «socialism with Chinese characteristics» (which is Marxism adapted to Chinese circumstances) and the «socialist market economy» respectively.[213][214]

Political concerns in China include the growing gap between rich and poor and government corruption.[215] Nonetheless, the level of public support for the government and its management of the nation is high, with 80–95% of Chinese citizens expressing satisfaction with the central government, according to a 2011 Harvard University survey.[216] A 2020 survey from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research also had most Chinese expressing satisfaction with the government on information dissemination and delivery of daily necessities during the COVID-19 pandemic.[217][218] A Harvard University survey published in July 2020 found that citizen satisfaction with the government had increased since 2003, also rating China’s government as more effective and capable than ever before in the survey’s history.[219]

Chinese Communist Party

According to the CCP constitution, its highest body of the CCP is the National Congress held every five years.[220] The National Congress elects the Central Committee, who then elects the party’s Politburo, Politburo Standing Committee and the general secretary (party leader), the top leadership of the country.[220] The general secretary holds ultimate power and authority over state and government and serves as the informal paramount leader.[221] The current general secretary is Xi Jinping, who took office on 15 November 2012.[222] At the local level, the secretary of the CCP committee of a subdivision outranks the local government level; CCP committee secretary of a provincial division outranks the governor while the CCP committee secretary of a city outranks the mayor.[223]

Since both the CCP and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) promote according to seniority, it is possible to discern distinct generations of Chinese leadership.[224] In official discourse, each group of leadership is identified with a distinct extension of the ideology of the party. Historians have studied various periods in the development of the government of the People’s Republic of China by reference to these «generations».

| Generation | Paramount Leader | Start | End | Ideology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Mao Zedong Hua Guofeng |

1949 | 1978 | Mao Zedong Thought |

| Second | Deng Xiaoping | 1978 | 1989 | Deng Xiaoping Theory |

| Third | Jiang Zemin | 1989 | 2002 | Three Represents |

| Fourth | Hu Jintao | 2002 | 2012 | Scientific Outlook on Development |

| Fifth | Xi Jinping | 2012 | Xi Jinping Thought |

Government

The nearly 3,000 member National People’s Congress (NPC) is constitutionally the «highest state organ of power»,[204] though it has been also described as a «rubber stamp» body.[225] The NPC meets annually, while the NPC Standing Committee, around 150 member body elected from NPC delegates, meets every couple of months.[225] In what China calls the «people’s congress system», local people’s congresses at the lowest level[z] are officially directly elected, with all the higher-level people’s congresses up to the NPC being elected by the level one below.[204] However, the elections are not pluralistic, with nominations at all levels being controlled by the CCP.[226] The NPC is dominated by the CCP, with another eight minor parties having nominal representation in the condition of upholding CCP leadership.[227]

The president is the ceremonial head of state, elected by the NPC. The incumbent president is Xi Jinping, who is also the general secretary of the CCP and the chairman of the Central Military Commission, making him China’s paramount leader. The premier is the head of government, with Li Qiang being the incumbent premier. The premier is officially nominated by the president and then elected by the NPC, and has generally been either the second or third-ranking member of the PSC. The premier presides over the State Council, China’s cabinet, composed of four vice premiers and the heads of ministries and commissions.[204] The Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) is a political advisory body that is critical in China’s «united front» system, which aims to gather non-CCP voices to support the CCP. Similar to the people’s congresses, CPPCC’s exist at various division, with the National Committee of the CPPCC being chaired by Wang Huning, one of China’s top leaders.[228]

Administrative divisions

The People’s Republic of China is constitutionally a unitary state officially divided into 23 provinces,[n] five autonomous regions (each with a designated minority group), and four municipalities—collectively referred to as «mainland China»—as well as the special administrative regions (SARs) of Hong Kong and Macau.[229] The PRC considers Taiwan to be its 23rd province,[230] although it is governed by the Republic of China (ROC), which claims to be the legitimate representative of China and its territory, though it has downplayed this claim since its democratization.[231] Geographically, all 31 provincial divisions of mainland China can be grouped into six regions: North China, Northeast China, East China, South Central China, Southwest China, and Northwest China.[232]

| Provinces (省) | Claimed Province | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Autonomous regions (自治区) | Municipalities (直辖市) | Special administrative regions (特别行政区) | |||

|

|

|

Foreign relations

Diplomatic relations of China

The PRC has diplomatic relations with 175 countries and maintains embassies in 162. Since 2019, China has the largest diplomatic network in the world.[233][234] In 1971, the PRC replaced the Republic of China (ROC) as the sole representative of China in the United Nations and as one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council.[235] China was also a former member and leader of the Non-Aligned Movement, and still considers itself an advocate for developing countries.[236] Along with Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa, China is a member of the BRICS group of emerging major economies and hosted the group’s third official summit at Sanya, Hainan in April 2011.[237]

Many other countries have switched recognition from the ROC to the PRC since the latter replaced the former in the United Nations in 1971.[238] The PRC officially maintains the one-China principle, which holds the view that there is only one sovereign state in the name of China, represented by the PRC, and that Taiwan is part of that China.[239] The unique status of Taiwan has led to countries recognizing the PRC to maintain unique «one-China policies» that differ from each other; some countries explicitly recognize the PRC’s claim over Taiwan, while others, including the US and Japan, only acknowledge the claim.[239] Chinese officials have protested on numerous occasions when foreign countries have made diplomatic overtures to Taiwan,[240] especially in the matter of armament sales.[241]

Much of current Chinese foreign policy is reportedly based on Premier Zhou Enlai’s Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, and is also driven by the concept of «harmony without uniformity», which encourages diplomatic relations between states despite ideological differences.[242] This policy may have led China to support or maintain close ties with states that are regarded as dangerous or repressive by Western nations, such as Myanmar,[243] North Korea and Iran.[244] China has a close political, economic and military relationship with Russia,[245] and the two states often vote in unison in the United Nations Security Council.[246][247][248]

Trade relations

China became the world’s largest trading nation in 2013 as measured by the sum of imports and exports, as well as the world’s largest commodity importer. comprising roughly 45% of maritime’s dry-bulk market.[249][250]

By 2016, China was the largest trading partner of 124 other countries.[251] China is the largest trading partner for the ASEAN nations, with a total trade value of $345.8 billion in 2015 accounting for 15.2% of ASEAN’s total trade.[252] ASEAN is also China’s largest trading partner.[253] In 2020, China became the largest trading partner of the European Union for goods, with the total value of goods trade reaching nearly $700 billion.[254] China, along with ASEAN, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand, is a member of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, the world’s largest free-trade area covering 30% of the world’s population and economic output.[255] China became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. In 2004, it proposed an entirely new East Asia Summit (EAS) framework as a forum for regional security issues.[256] The EAS, which includes ASEAN Plus Three, India, Australia and New Zealand, held its inaugural summit in 2005.[257]

China has had a long and complex trade relationship with the United States. In 2000, the United States Congress approved «permanent normal trade relations» (PNTR) with China, allowing Chinese exports in at the same low tariffs as goods from most other countries.[258] China has a significant trade surplus with the United States, its most important export market.[259] Economists have argued that the renminbi is undervalued, due to currency intervention from the Chinese government, giving China an unfair trade advantage.[260] In August 2019, the United States Department of the Treasury designated China as a «currency manipulator»,[261] later reversing the decision in January 2020.[262] The US and other foreign governments have also alleged that China doesn’t respect intellectual property (IP) rights and steals IP through espionage operations,[263][264] with the US Department of Justice saying that 80% of all the prosecutions related to economic espionage it brings were about conduct to benefit the Chinese state.[265]

Since the turn of the century, China has followed a policy of engaging with African nations for trade and bilateral co-operation;[266][267][268] in 2019, Sino-African trade totalled $208 billion, having grown 20 times over two decades.[269] According to Madison Condon «China finances more infrastructure projects in Africa than the World Bank and provides billions of dollars in low-interest loans to the continent’s emerging economies.»[270] China maintains extensive and highly diversified trade links with the European Union.[254] China has furthermore strengthened its trade ties with major South American economies,[271] and is the largest trading partner of Brazil, Chile, Peru, Uruguay, Argentina, and several others.[272]

China’s Belt and Road Initiative has expanded significantly over the last six years and, as of April 2020, includes 138 countries and 30 international organizations. In addition to intensifying foreign policy relations, the focus here is particularly on building efficient transport routes. The focus is particularly on the maritime Silk Road with its connections to East Africa and Europe and there are Chinese investments or related declarations of intent at numerous ports such as Gwadar, Kuantan, Hambantota, Piraeus and Trieste. However many of these loans made under the Belt and Road program are unsustainable and China has faced a number of calls for debt relief from debtor nations.[273][274]

Territorial disputes

Map depicting territorial disputes between the PRC and neighboring states. For a larger map, see here.

Ever since its establishment after the Chinese Civil War, the PRC has claimed the territories governed by the Republic of China (ROC), a separate political entity today commonly known as Taiwan, as a part of its territory. It regards the island of Taiwan as its Taiwan Province, Kinmen and Matsu as a part of Fujian Province and islands the ROC controls in the South China Sea as a part of Hainan Province and Guangdong Province. These claims are controversial because of the complicated Cross-Strait relations, with the PRC treating the One-China Principle as one of its most important diplomatic principles.[275][better source needed]

China has resolved its land borders with 12 out of 14 neighboring countries, having pursued substantial compromises in most of them.[276][277][278] As of 2023, China currently has a disputed land border with India and Bhutan.[citation needed] China is additionally involved in maritime disputes with multiple countries over the ownership of several small islands in the East and South China Seas, such as Socotra Rock, the Senkaku Islands and the entirety of South China Sea Islands,[279][280] along with the EEZ disputes over East China Sea.

Sociopolitical issues and human rights

China uses a massive espionage network of cameras, facial recognition software, sensors, and surveillance of personal technology as a means of social control of persons living in the country.[281] The Chinese democracy movement, social activists, and some members of the CCP[who?] believe in the need for social and political reform. While economic and social controls have been significantly relaxed in China since the 1970s, political freedom is still tightly restricted. The Constitution of the People’s Republic of China states that the «fundamental rights» of citizens include freedom of speech, freedom of the press, the right to a fair trial, freedom of religion, universal suffrage, and property rights. However, in practice, these provisions do not afford significant protection against criminal prosecution by the state.[282][283] Although some criticisms of government policies and the ruling CCP are tolerated, censorship of political speech and information, most notably on the Internet,[284][285] are routinely used to prevent collective action.[286]

A number of foreign governments, foreign press agencies, and non-governmental organizations have criticized China’s human rights record, alleging widespread civil rights violations such as detention without trial, forced abortions,[287] forced confessions, torture, restrictions of fundamental rights,[212][288] and excessive use of the death penalty.[289][290] The government suppresses popular protests and demonstrations that it considers a potential threat to «social stability», as was the case with the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre.[291]

China is regularly accused of large-scale repression and human rights abuses in Tibet and Xinjiang,[293][294][295] including violent police crackdowns and religious suppression.[296][297] In Xinjiang, at least one million Uyghurs and other ethnic and religion minorities have been detained in internment camps, officially termed «Vocational Education and Training Centers», aimed at changing the political thinking of detainees, their identities, and their religious beliefs.[140] According to the U.S. Department of State, actions including political indoctrination, torture, physical and psychological abuse, forced sterilization, sexual abuse, and forced labor are common in these facilities.[298] The state has also sought to control offshore reporting of tensions in Xinjiang, intimidating foreign-based reporters by detaining their family members.[299] According to a 2020 report, China’s treatment of Uyghurs meets the UN definition of genocide,[300] and several groups called for a UN investigation.[301] Several countries have recognized China’s actions in Xinjiang as a genocide.[302][292][303]

Global studies from Pew Research Center in 2014 and 2017 ranked the Chinese government’s restrictions on religion as among the highest in the world, despite low to moderate rankings for religious-related social hostilities in the country.[304][305] The Global Slavery Index estimated that in 2016 more than 3.8 million people were living in «conditions of modern slavery», or 0.25% of the population, including victims of human trafficking, forced labor, forced marriage, child labor, and state-imposed forced labor. The state-imposed forced system was formally abolished in 2013, but it is not clear to which extent its various practices have stopped.[306] The Chinese penal system includes labor prison factories, detention centers, and re-education camps, collectively known as laogai («reform through labor»). The Laogai Research Foundation in the United States estimated that there were over a thousand slave labor prisons and camps in China.[307]

Military

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is considered one of the world’s most powerful militaries and has rapidly modernized in the recent decades.[308] It consists of the Ground Force (PLAGF), the Navy (PLAN), the Air Force (PLAAF), the Rocket Force (PLARF) and the Strategic Support Force (PLASSF). Its nearly 2.2 million active duty personnel is the largest in the world. The PLA holds the world’s third-largest stockpile of nuclear weapons,[309][310] and the world’s second-largest navy by tonnage.[311] China’s official military budget for 2022 totalled US$230 billion (1.45 trillion Yuan), the second-largest in the world. According to SIPRI estimates, its military spending from 2012 to 2021 averaged US$215 billion per year or 1.7 per cent of GDP, behind only the United States at US$734 billion per year or 3.6 per cent of GDP.[312] The PLA is commanded by the Central Military Commission (CMC) of the party and the state; though officially two separate organizations, the two CMCs have identical membership except during leadership transition periods and effectively function as one organization. The chairman of the CMC is the commander-in-chief of the PLA, with the officeholder also generally being the CCP general secretary, making them the paramount leader of China.[313]

Economy

A proportional representation of Chinese exports, 2019

China has the world’s second-largest economy in terms of nominal GDP,[314] and the world’s largest economy in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP).[315] As of 2021, China accounts for around 18% of the world economy by GDP nominal.[316] China is one of the world’s fastest-growing major economies,[317] with its economic growth having been consistently above 6 percent since the introduction of economic reforms in 1978.[318] According to the World Bank, China’s GDP grew from $150 billion in 1978 to $17.73 trillion by 2021.[319] Of the world’s 500 largest companies, 145 are headquartered in China.[320]

China was one of the world’s most most foremost economic powers throughout the arc of East Asian and global history. The country had one of the largest economies in the world for most of the past two millennia,[321] during which it has seen cycles of prosperity and decline.[322][323] Since economic reforms began in 1978, China has developed into a highly diversified economy and one of the most consequential players in international trade. Major sectors of competitive strength include manufacturing, retail, mining, steel, textiles, automobiles, energy generation, green energy, banking, electronics, telecommunications, real estate, e-commerce, and tourism. China has three out of the ten largest stock exchanges in the world[324]—Shanghai, Hong Kong and Shenzhen—that together have a market capitalization of over $15.9 trillion, as of October 2020.[325] China has four (Shanghai, Hong Kong, Beijing, and Shenzhen) out of the world’s top ten most competitive financial centers, which is more than any country in the 2020 Global Financial Centres Index.[326] By 2035, China’s four cities (Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou and Shenzhen) are projected to be among the global top ten largest cities by nominal GDP according to a report by Oxford Economics.[327]

Modern-day China is often described as an example of state capitalism or party-state capitalism.[329][330] In 1992, Jiang Zemin termed the country a socialist market economy.[331] Others have described it as a form of Marxism–Leninism adapted to co-exist with global capitalism.[332] The state dominates in strategic «pillar» sectors such as energy production and heavy industries, but private enterprise has expanded enormously, with around 30 million private businesses recorded in 2008.[333][334][335] According to official statistics, privately owned companies constitute more than 60% of China’s GDP.[336]

China has been the world’s largest manufacturing nation since 2010, after overtaking the US, which had been the largest for the previous hundred years.[337][338] China has also been the second largest in high-tech manufacturing since 2012, according to US National Science Foundation.[339] China is the second largest retail market in the world, next to the United States.[340] China leads the world in e-commerce, accounting for 40% of the global market share in 2016[341] and more than 50% of the global market share in 2019.[342] China is the world’s leader in electric vehicle consumption and production, manufacturing and buying half of all the plug-in electric cars (BEV and PHEV) in the world as of 2022.[343] China is also the leading producer of batteries for electric vehicles as well as several key raw materials for batteries.[344] China had 174 GW of installed solar capacity by the end of 2018, which amounts to more than 40% of the global solar capacity.[345][346]

Wealth

China accounted for 17.9% of the world’s total wealth in 2021, second highest in the world after the US.[347] It ranks at 65th at GDP (nominal) per capita, making it an upper-middle income country.[348] China brought more people out of extreme poverty than any other country in history[349][350]—between 1978 and 2018, China reduced extreme poverty by 800 million. China reduced the extreme poverty rate—per international standard, it refers to an income of less than $1.90/day—from 88% in 1981 to 1.85% by 2013.[351] The portion of people in China living below the international poverty line of $1.90 per day (2011 PPP) fell to 0.3% in 2018 from 66.3% in 1990. Using the lower-middle income poverty line of $3.20 per day, the portion fell to 2.9% in 2018 from 90.0% in 1990. Using the upper-middle income poverty line of $5.50 per day, the portion fell to 17.0% from 98.3% in 1990.[352]

From 1978 to 2018, the average standard of living multiplied by a factor of twenty-six.[353] Wages in China have grown a lot in the last 40 years—real (inflation-adjusted) wages grew seven-fold from 1978 to 2007.[354] Per capita incomes have risen significantly – when the PRC was founded in 1949, per capita income in China was one-fifth of the world average; per capita incomes now equal the world average itself.[353] China’s development is highly uneven. Its major cities and coastal areas are far more prosperous compared to rural and interior regions.[355] It has a high level of economic inequality,[356] which has increased in the past few decades.[357] In 2018 China’s Gini coefficient was 0.467, according to the World Bank.[11]

As of 2020, China was second in the world, after the US, in total number of billionaires and total number of millionaires, with 698 Chinese billionaires and 4.4 million millionaires.[358] In 2019, China overtook the US as the home to the highest number of people who have a net personal wealth of at least $110,000, according to the global wealth report by Credit Suisse.[359][360] According to the Hurun Global Rich List 2020, China is home to five of the world’s top ten cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou in the 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 10th spots, respectively) by the highest number of billionaires, which is more than any other country.[361] China had 85 female billionaires as of January 2021, two-thirds of the global total, and minted 24 new female billionaires in 2020.[362] China has had the world’s largest middle-class population since 2015,[363] and the middle-class grew to a size of 400 million by 2018.[364]

China in the global economy

|

|

| Largest economies by nominal GDP in 2022[365] |