News flash: the Bible is huge: about 611,000 words long, all divvied up across 66 smaller documents called the “books” of the Bible.

That’s because the Bible is a collection of writings from different authors writing at different times. In some ways, that makes it easier to approach the Bible: we can read it in “chunks” rather than needing to read the whole Bible at once.

But it also makes it a bit confusing. The Bible itself is a book. In fact, the word “bible” comes from the Latin and Greek words for “book” (biblia and biblos, respectively). But it’s a book of books. That means if you want to know the Bible better, you’ll need to get acquainted with the 66 documents it comprises.

That can take a while, so . . .

Here’s a snapshot of every book of the Bible

I’ve written a one-sentence overview of every book of the Bible. They’re listed in the order they show up in the Protestant Bible. If you want more, I’ve linked to quick, 3-minute guides to every book of the Bible, too.

This is a lot to take in, so if you want to start with baby steps, check out this list of the shortest books of the Bible.

Old Testament books of the Bible

The Old Testament includes 39 books which were written long before Jesus was born.

The first five books of the Bible are called the Torah, or the Law of Moses.

1. Genesis

Genesis answers two big questions: “How did God’s relationship with the world begin?” and “Where did the nation of Israel come from?”

Author: Traditionally Moses, but the stories are much older.

Fun fact: Most of the famous Bible stories you’ve heard about are probably found in the book of Genesis. This is where the stories of Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Noah and the Ark, the Tower of Babel, Abraham and Isaac, Jacob’s ladder, and Joseph’s coat of many colors are recorded.

2. Exodus

God saves Israel from slavery in Egypt, and then enters into a special relationship with them.

Author: Traditionally Moses

3. Leviticus

God gives Israel instructions for how to worship Him.

Author: traditionally Moses

4. Numbers

Israel fails to trust and obey God, and wanders in the wilderness for 40 years.

Author: Traditionally Moses

5. Deuteronomy

Moses gives Israel instructions (in some ways, a recap of the laws in Exodus–Numbers) for how to love and obey God in the Promised Land.

Author: Traditionally Moses

6. Joshua

Joshua (Israel’s new leader) leads Israel to conquer the Promised land, then parcels out territories to the twelve tribes of Israel.

Author: Nobody knows

Fun fact: You’ve probably heard of a few fantastic stories from this book (the Battle of Jericho and the day the sun stood still), but most of the action happens in the first half of this book. The last half is pretty much all about divvying up the real estate.

7. Judges

Israel enters a cycle of turning from God, falling captive to oppressive nations, calling out to God, and being rescued by leaders God sends their way (called “judges”).

Author: Nobody knows

8. Ruth

Two widows lose everything, and find hope in Israel—which leads to the birth of the future King David.

Author: Nobody knows

9. 1 Samuel

Israel demands a king, who turns out to be quite a disappointment.

Author: Nobody knows

10. 2 Samuel

David, a man after God’s own heart, becomes king of Israel.

Author: Nobody knows

11. 1 Kings

The kingdom of Israel has a time of peace and prosperity under King Solomon, but afterward splits, and the two lines of kings turn away from God.

Author: Nobody knows

12. 2 Kings

Both kingdoms ignore God and his prophets, until they both fall captive to other world empires.

Author: Nobody knows

13. 1 Chronicles

This is a brief history of Israel from Adam to David, culminating with David commissioning the temple of God in Jerusalem.

Author: Traditionally Ezra

14. 2 Chronicles

David’s son Solomon builds the temple, but after centuries of rejecting God, the Babylonians take the southern Israelites captive and destroy the temple.

Author: Traditionally Ezra

15. Ezra

The Israelites rebuild the temple in Jerusalem, and a scribe named Ezra teaches the people to once again obey God’s laws.

Author: Ezra

16. Nehemiah

The city of Jerusalem is in bad shape, so Nehemiah rebuilds the wall around the city.

Author: Nehemiah

17. Esther

Someone hatches a genocidal plot to bring about Israel’s extinction, and Esther must face the emperor to ask for help.

Author: Nobody knows

Books of Poetry in the Old Testament

18. Job

Satan attacks a righteous man named Job, and Job and his friends argue about why terrible things are happening to him.

Author: Nobody knows

19. Psalms

A collection of 150 songs that Israel sang to God (and to each other)—kind of like a hymnal for the ancient Israelites.

Author: So many authors—meet them all here!

20. Proverbs

A collection of sayings written to help people make wise decisions that bring about justice.

Author: Solomon and other wise men

21. Ecclesiastes

A philosophical exploration of the meaning of life—with a surprisingly nihilistic tone for the Bible.

Author: Traditionally Solomon

22. Song of Solomon (Song of Songs)

A love song (or collection of love songs) celebrating love, desire, and marriage.

Author: Traditionally Solomon (but it could have been written about Solomon, or in the style of Solomon)

Books of prophecy in the Old Testament

23. Isaiah

God sends the prophet Isaiah to warn Israel of future judgment—but also to tell them about a coming king and servant who will “bear the sins of many.”

Author: Isaiah (and maybe some of his followers)

24. Jeremiah

God sends a prophet to warn Israel about the coming Babylonian captivity, but the people don’t take the news very well.

Author: Jeremiah

25. Lamentations

A collection of dirges lamenting the fall of Jerusalem after the Babylonian attacks.

Author: Traditionally Jeremiah

26. Ezekiel

God chooses a man to speak for Him to Israel, to tell them the error of their ways and teach them justice: Ezekiel.

Author: Ezekiel

27. Daniel

Daniel becomes a high-ranking wise man in the Babylonian and Persian empires, and has prophetic visions concerning Israel’s future.

Author: Daniel (with other contributors)

28. Hosea

Hosea is told to marry a prostitute who leaves him, and he must bring her back: a picture of God’s relationship with Israel.

Author: Hosea

29. Joel

God sends a plague of locusts to Judge Israel, but his judgment on the surrounding nations is coming, too.

Author: Joel

30. Amos

A shepherd named Amos preaches against the injustice of the Northern Kingdom of Israel.

Author: Amos

31. Obadiah

Obadiah warns the neighboring nation of Edom that they will be judged for plundering Jerusalem.

Author: Obadiah

32. Jonah

A disobedient prophet runs from God, is swallowed by a great fish, and then preaches God’s message to the city of Nineveh.

Author: Traditionally Jonah

33. Micah

Micah confronts the leaders of Israel and Judah regarding their injustice, and prophecies that one day the Lord himself will rule in perfect justice.

Author: Micah

34. Nahum

Nahum foretells of God’s judgment on Nineveh, the capital of Assyria.

Author: Nahum

35. Habakkuk

Habakkuk pleads with God to stop the injustice and violence in Judah, but is surprised to find that God will use the even more violent Babylonians to do so.

Author: Habakkuk

36. Zephaniah

God warns that he will judge Israel and the surrounding nations, but also that he will restore them in peace and justice.

Author: Zephaniah

37. Haggai

The people have abandoned the work of restoring God’s temple in Jerusalem, and so Haggai takes them to task.

Author: Haggai

38. Zechariah

The prophet Zechariah calls Israel to return to God, and records prophetic visions that show what’s happening behind the scenes.

39. Malachi

God has been faithful to Israel, but they continue to live disconnected from him—so God sends Malachi to call them out.

New Testament books of the Bible

The New Testament includes 27 books about Jesus’ ministry and what it means to follow him. The first four books of the New Testament are called the Gospels.

40. The Gospel of Matthew

This is an account of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection, focusing on Jesus’ role as the true king of the Jews.

Author: Matthew

41. The Gospel of Mark

This brief account of Jesus’ earthly ministry highlights Jesus’ authority and servanthood.

Author: John Mark

42. The Gospel of Luke

Luke writes the most thorough account of Jesus’ life, pulling together eyewitness testimonies to tell the full story of Jesus.

Author: Luke

43. The Gospel of John

John lists stories of signs and miracles with the hope that readers will believe in Jesus.

Author: John

44. Acts

Jesus returns to the Father, the Holy Spirit comes to the church, and the gospel of Jesus spreads throughout the world.

Author: Luke

Paul’s epistles

45. Romans

Paul summarizes how the gospel of Jesus works in a letter to the churches at Rome, where he plans to visit.

Author: Paul

46. 1 Corinthians

Paul writes a disciplinary letter to a fractured church in Corinth, and answers some questions that they’ve had about how Christians should behave.

Author: Paul

47. 2 Corinthians

Paul writes a letter of reconciliation to the church at Corinth, and clears up some concerns that they have.

Author: Paul

48. Galatians

Paul hears that the Galatian churches have been lead to think that salvation comes from the law of Moses, and writes a (rather heated) letter telling them where the false teachers have it wrong.

Author: Paul

49. Ephesians

Paul writes to the church at Ephesus about how to walk in grace, peace, and love.

Author: Paul

50. Philippians

An encouraging letter to the church of Philippi from Paul, telling them how to have joy in Christ.

Author: Paul

51. Colossians

Paul writes the church at Colossae a letter about who they are in Christ, and how to walk in Christ.

Author: Paul

52. 1 Thessalonians

Paul has heard a good report on the church at Thessalonica, and encourages them to “excel still more” in faith, hope, and love.

Author: Paul

53. 2 Thessalonians

Paul instructs the Thessalonians on how to stand firm until the coming of Jesus.

Author: Paul

54. 1 Timothy

Paul gives his protegé Timothy instruction on how to lead a church with sound teaching and a godly example.

Author: Paul

55. 2 Timothy

Paul is nearing the end of his life, and encourages Timothy to continue preaching the word.

Author: Paul

56. Titus

Paul advises Titus on how to lead orderly, counter-cultural churches on the island of Crete.

Author: Paul

57. Philemon

Paul strongly recommends that Philemon accept his runaway slave as a brother, not a slave.

Author: Paul

The general, or Catholic, epistles

58. Hebrews

A letter encouraging Christians to cling to Christ despite persecution, because he is greater.

Author: Nobody knows

59. James

A letter telling Christians to live in ways that demonstrate their faith in action.

Author: James (likely the brother of Jesus)

60. 1 Peter

Peter writes to Christians who are being persecuted, encouraging them to testify to the truth and live accordingly.

Author: Peter

61. 2 Peter

Peter writes a letter reminding Christians about the truth of Jesus, and warning them that false teachers will come.

Author: Peter

62. 1 John

John writes a letter to Christians about keeping Jesus’ commands, loving one another, and important things they should know.

Author: John

63. 2 John

A very brief letter about walking in truth, love, and obedience.

Author: John

64. 3 John

An even shorter letter about Christian fellowship.

Author: John

65. Jude

A letter encouraging Christians to contend for the faith, even though ungodly persons have crept in unnoticed.

Author: Jude

66. Revelation

John sees visions of things that have been, things that are, and things that are yet to come.

Author: John

January 19, 2019

in Bible, Christian Life and Faith, Sermons

1105

What Every Christian Should Know, Believe and live.

(Scripture Passage: Psalm 119: 89-104)

The Bible is a very wonderful book. It is a composite library of 66 books, of which 39 comprise the Old Testament and 27 the New Testament. The Bible is unique, for it is no mere haphazard collection of writings, but is an organic whole, each of the 66 books being necessary to the whole ‘library’. Any careful reader will quickly discover that there is a plan behind the arrangement of the books, and a unity about the Bible that is nothing less than miraculous. That is why we have entitled this study ‘The Bible: God’s Miracle Book’. The Bible is inspired, authoritative and entirely trustworthy. What are the grounds for believing this? Consider the following:

- THE WONDER AND MIRACLE OF ITS FORMATION.

The Old Testament may be divided into four sections: The Pentateuch (Genesis to Deuteronomy); the historical books (Joshua to Job); the poetical books (Psalms to Song of Solomon); and the prophetical books (Isaiah to Malachi). In the New Testament the historical books are Matthew to Acts; the doctrinal books are Romans to Jude; and the great book of prophecy is The Revelation. But from where did these 66 books come? How were they written, and by whom? How were they brought together in one volume? Here is a miracle of tremendous significance!

The 66 books of the Bible were written by some forty different writers, who lived in different countries, spoke different languages and came from different backgrounds. The writers included a king, a doctor, a herdsman, a tax gatherer, a theologian, a scribe, a fisherman, etc., and their writings spread over a period of 1600 years, so there could be no collusion or communication. Think of it - 40 different writers, spread over 55 generations, producing 66 books; and yet when these books are placed together there is a perfect unity and harmony about them and they all fit together like a jigsaw. What is the explanation? There is only one explanation: the Bible is God’s miracle book.

- THE CLAIM OF ITS WRITERS.

God is the Author of the Bible, but He employed many human writers. These forty writers claimed to be writing down the words of the Lord. ‘This is what the Lord says ’ and similar expressions occur hundreds of times in the Bible -

compare Exodus 20:1 and 24:4. ‘In the twenty-seven chapters of Leviticus there are fifty-six assertions assigning its authorship to the Lord Himself.’ The same is true of the historical, the poetical and the prophetical books of the Old Testament. What about the New Testament? The Old Testament is woven into the New Testament. Literally scores of Old Testament sayings are quoted in the New Testament, and Jesus, the Gospel-writers, Paul, Peter, James and John all accepted the divine authority and authorship of the Old Testament – look up 2 Timothy 3:16; 2 Peter 1:21. What is the explanation of the fact that the writers in the Bible claim to have written under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit? The explanation is this: the Bible is God’s word not man’s word book.

- THE ACCURACY OF ITS STATEMENTS.

It is commonly held that the Bible is full of errors and mis-statements. Let us understand that there are many things in the Bible about which we need fuller light; but let us also state confidently that the Bible is accurate and reliable. What seem to be discrepancies are often cleared away after careful and prayerful investigation - look up Psalm 119:160. There is not one single proved inaccuracy in the whole Bible. The Bible is accurate historically, geographically, genealogically, scientifically, psychologically, typologically, and verbally. What is the secret of this amazing accuracy? The Bible is God’s word not man’s word book.

- THE PROGRESSIVENESS OF ITS REVELATION.

The revelation of truth we have in the Bible is progressively given, and by the time we get to the Book of Revelation we have a perfect and complete body of truth. In the 66 books there is everything we need to know about ourselves, sin, death, Heaven, human destiny, human relations and, above all, about God and His nature, about Christ and His love, and about redemption. The revelation in the Bible is complete - look up Jude 3. There is everything we need in the Bible: the Bible is God’s word not man’s word book.

- THE FULFILMENT OF ITS PROPHECIES.

Two-thirds of the Bible is made up of prophecies. Prophecy is history written in advance. Only a small portion of these prophecies has so far been fulfilled, but all fulfilled prophecy has been literally fulfilled. In the Bible we have prophecies relating to places, events and people. A most helpful approach to this subject would be to study the Old Testament prophecies relating to the Person of Christ and see them literally fulfilled in His birth, life, ministry, death, resurrection and ascension. Note also that over thirty prophecies relating to His arrest, trial and crucifixion were all literally fulfilled within 24 hours when He died. What is the explanation of the power of this book to predict the future? The Bible is God’s word not man’s word book.

- THE INSISTENCE OF ITS MESSAGE.

One message runs right through the Bible – the message of God’s great love for sinful humanity; of the gift of His Son, our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ; of His provision of salvation, and of His righteous claims perfectly satisfied at Calvary – Genesis 3:15. Throughout the Bible we trace the message of John 3:16, until we come to the final appeal to sinful men to accept the Gospel invitation – Revelation 22:17. What is the explanation of this one insistent message running through the Bible? The Bible is God’s word not man’s book. But as we conclude this study, notice one final evidence of the Bible’s unique nature, inspiration and authority: it is to be found in:

- THE EXPLANATION OF ITS AUTHOR.

What is the explanation of the miraculous nature of the Bible? The answer is stated in 1 Timothy 3:16 and 2 Peter 1:21. These verses proclaim the inspiration of the Old Testament scriptures; while John 14:26 and 16:13 refer to the inspiration of the writers of the books of the New Testament.

Thank God, the Bible is God-given, fully inspired, completely authoritative and absolutely trustworthy! It truly is God’s word book. Let us love it, believe it, learn it, practice it, defend it and pass it on to others.

The Holy Bible is the Voice of God, speaking to man created in His own image and likeness revealing Himself; it is not the voice of Man speaking to his fellow men about God, his Creator.

Rev Ed Arcton

Ed Arcton is a Pastor and President of Liberation Mission For Christ. A Preacher, Teacher and Intercessor. Graduate from MBC, Ghana and CLC at Michigan, USA. Believe in the Authority and Divinely inspired WORD OF GOD, the Holy Bible as God’s given and is the constitution of our Life. Ed, Believes that, the BIBLE is the Voice of God speaking to every man and it’s not the voice of man telling his fellow men about God. Ed passion is to Explain and Expand the Holy Scriptures to all men wherever he is and will be, especially the people of God, Church of the Living God.

Recent Sermons

The Bible (from Koine Greek τὰ βιβλία, tà biblía, ‘the books’) is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthology – a compilation of texts of a variety of forms – originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Koine Greek. These texts include instructions, stories, poetry, and prophecies, among other genres. The collection of materials that are accepted as part of the Bible by a particular religious tradition or community is called a biblical canon. Believers in the Bible generally consider it to be a product of divine inspiration, but the way they understand what that means and interpret the text can vary.

The religious texts were compiled by different religious communities into various official collections. The earliest contained the first five books of the Bible. It is called the Torah in Hebrew and the Pentateuch (meaning five books) in Greek; the second oldest part was a collection of narrative histories and prophecies (the Nevi’im); the third collection (the Ketuvim) contains psalms, proverbs, and narrative histories. «Tanakh» is an alternate term for the Hebrew Bible composed of the first letters of those three parts of the Hebrew scriptures: the Torah («Teaching»), the Nevi’im («Prophets»), and the Ketuvim («Writings»). The Masoretic Text is the medieval version of the Tanakh, in Hebrew and Aramaic, that is considered the authoritative text of the Hebrew Bible by modern Rabbinic Judaism. The Septuagint is a Koine Greek translation of the Tanakh from the third and second centuries BCE (Before Common Era); it largely overlaps with the Hebrew Bible.

Christianity began as an outgrowth of Judaism, using the Septuagint as the basis of the Old Testament. The early Church continued the Jewish tradition of writing and incorporating what it saw as inspired, authoritative religious books. The gospels, Pauline epistles and other texts quickly coalesced into the New Testament.

With estimated total sales of over five billion copies, the Bible is the best-selling publication of all time. It has had a profound influence both on Western culture and history and on cultures around the globe. The study of it through biblical criticism has indirectly impacted culture and history as well. The Bible is currently translated or being translated into about half of the world’s languages.

Etymology

The term «Bible» can refer to the Hebrew Bible or the Christian Bible, which contains both the Old and New Testaments.[1]

The English word Bible is derived from Koinē Greek: τὰ βιβλία, romanized: ta biblia, meaning «the books» (singular βιβλίον, biblion).[2]

The word βιβλίον itself had the literal meaning of «scroll» and came to be used as the ordinary word for «book».[3] It is the diminutive of βύβλος byblos, «Egyptian papyrus», possibly so called from the name of the Phoenician sea port Byblos (also known as Gebal) from whence Egyptian papyrus was exported to Greece.[4]

The Greek ta biblia («the books») was «an expression Hellenistic Jews used to describe their sacred books».[5] The biblical scholar F. F. Bruce notes that John Chrysostom appears to be the first writer (in his Homilies on Matthew, delivered between 386 and 388) to use the Greek phrase ta biblia («the books») to describe both the Old and New Testaments together.[6]

Latin biblia sacra «holy books» translates Greek τὰ βιβλία τὰ ἅγια (tà biblía tà hágia, «the holy books»).[7] Medieval Latin biblia is short for biblia sacra «holy book». It gradually came to be regarded as a feminine singular noun (biblia, gen. bibliae) in medieval Latin, and so the word was loaned as singular into the vernaculars of Western Europe.[8]

Development and history

Hebrew Bible from 1300. Genesis.

The Bible is not a single book; it is a collection of books whose complex development is not completely understood. The oldest books began as songs and stories orally transmitted from generation to generation. Scholars are just beginning to explore «the interface between writing, performance, memorization, and the aural dimension» of the texts. Current indications are that the ancient writing–reading process was supplemented by memorization and oral performance in community.[9] The Bible was written and compiled by many people, most of whom are unknown, from a variety of disparate cultures.[10]

British biblical scholar John K. Riches wrote:[11]

[T]he biblical texts were produced over a period in which the living conditions of the writers – political, cultural, economic, and ecological – varied enormously. There are texts which reflect a nomadic existence, texts from people with an established monarchy and Temple cult, texts from exile, texts born out of fierce oppression by foreign rulers, courtly texts, texts from wandering charismatic preachers, texts from those who give themselves the airs of sophisticated Hellenistic writers. It is a time-span which encompasses the compositions of Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Thucydides, Sophocles, Caesar, Cicero, and Catullus. It is a period which sees the rise and fall of the Assyrian empire (twelfth to seventh century) and of the Persian empire (sixth to fourth century), Alexander’s campaigns (336–326), the rise of Rome and its domination of the Mediterranean (fourth century to the founding of the Principate, 27 BCE), the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple (70 CE), and the extension of Roman rule to parts of Scotland (84 CE).

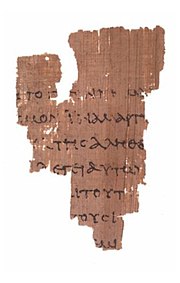

The books of the Bible were initially written and copied by hand on papyrus scrolls.[12] No originals survive. The age of the original composition of the texts is therefore difficult to determine and heavily debated. Using a combined linguistic and historiographical approach, Hendel and Joosten date the oldest parts of the Hebrew Bible (the Song of Deborah in Judges 5 and the Samson story of Judges 16 and 1 Samuel) to having been composed in the premonarchial early Iron Age (c. 1200 BCE).[13] The Dead Sea Scrolls, discovered in the caves of Qumran in 1947, are copies that can be dated to between 250 BCE and 100 CE. They are the oldest existing copies of the books of the Hebrew Bible of any length that are not fragments.[14]

The earliest manuscripts were probably written in paleo-Hebrew, a kind of cuneiform pictograph similar to other pictographs of the same period.[15] The exile to Babylon most likely prompted the shift to square script (Aramaic) in the fifth to third centuries BCE.[16] From the time of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Hebrew Bible was written with spaces between words to aid in reading.[17] By the eighth century CE, the Masoretes added vowel signs.[18] Levites or scribes maintained the texts, and some texts were always treated as more authoritative than others.[19] Scribes preserved and changed the texts by changing the script and updating archaic forms while also making corrections. These Hebrew texts were copied with great care.[20]

Considered to be scriptures (sacred, authoritative religious texts), the books were compiled by different religious communities into various biblical canons (official collections of scriptures).[21] The earliest compilation, containing the first five books of the Bible and called the Torah (meaning «law», «instruction», or «teaching») or Pentateuch («five books»), was accepted as Jewish canon by the fifth century BCE. A second collection of narrative histories and prophesies, called the Nevi’im («prophets»), was canonized in the third century BCE. A third collection called the Ketuvim («writings»), containing psalms, proverbs, and narrative histories, was canonized sometime between the second century BCE and the second century CE.[22] These three collections were written mostly in Biblical Hebrew, with some parts in Aramaic, which together form the Hebrew Bible or «TaNaKh» (an abbreviation of «Torah», «Nevi’im», and «Ketuvim»).[23]

Hebrew Bible

There are three major historical versions of the Hebrew Bible: the Septuagint, the Masoretic Text, and the Samaritan Pentateuch (which contains only the first five books). They are related but do not share the same paths of development. The Septuagint, or the LXX, is a translation of the Hebrew scriptures, and some related texts, into Koine Greek, begun in Alexandria in the late third century BCE and completed by 132 BCE.[24][25][a] Probably commissioned by Ptolemy II Philadelphus, King of Egypt, it addressed the need of the primarily Greek-speaking Jews of the Graeco-Roman diaspora.[24][26] Existing complete copies of the Septuagint date from the third to the fifth centuries CE, with fragments dating back to the second century BCE. [27] Revision of its text began as far back as the first century BCE.[28] Fragments of the Septuagint were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls; portions of its text are also found on existing papyrus from Egypt dating to the second and first centuries BCE and to the first century CE.[28]: 5

The Masoretes began developing what would become the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible in Rabbinic Judaism near the end of the Talmudic period (c. 300–c. 500 CE), but the actual date is difficult to determine.[29][30][31] In the sixth and seventh centuries, three Jewish communities contributed systems for writing the precise letter-text, with its vocalization and accentuation known as the mas’sora (from which we derive the term «masoretic»).[29] These early Masoretic scholars were based primarily in the Galilean cities of Tiberias and Jerusalem, and in Babylonia (modern Iraq). Those living in the Jewish community of Tiberias in ancient Galilee (c. 750–950), made scribal copies of the Hebrew Bible texts without a standard text, such as the Babylonian tradition had, to work from. The canonical pronunciation of the Hebrew Bible (called Tiberian Hebrew) that they developed, and many of the notes they made, therefore differed from the Babylonian.[32] These differences were resolved into a standard text called the Masoretic text in the ninth century.[33] The oldest complete copy still in existence is the Leningrad Codex dating to c. 1000 CE.[34]

The Samaritan Pentateuch is a version of the Torah maintained by the Samaritan community since antiquity, which was rediscovered by European scholars in the 17th century; its oldest existing copies date to c. 1100 CE.[35] Samaritans include only the Pentateuch (Torah) in their biblical canon.[36] They do not recognize divine authorship or inspiration in any other book in the Jewish Tanakh.[b] A Samaritan Book of Joshua partly based upon the Tanakh’s Book of Joshua exists, but Samaritans regard it as a non-canonical secular historical chronicle.[37]

In the seventh century, the first codex form of the Hebrew Bible was produced. The codex is the forerunner of the modern book. Popularized by early Christians, it was made by folding a single sheet of papyrus in half, forming «pages». Assembling multiples of these folded pages together created a «book» that was more easily accessible and more portable than scrolls. In 1488, the first complete printed press version of the Hebrew Bible was produced.[38]

New Testament

During the rise of Christianity in the first century CE, new scriptures were written in Koine Greek. Christians called these new scriptures the «New Testament», and began referring to the Septuagint as the «Old Testament».[39] The New Testament has been preserved in more manuscripts than any other ancient work.[40][41] Most early Christian copyists were not trained scribes.[42] Many copies of the gospels and Paul’s letters were made by individual Christians over a relatively short period of time very soon after the originals were written.[43] There is evidence in the Synoptic Gospels, in the writings of the early church fathers, from Marcion, and in the Didache that Christian documents were in circulation before the end of the first century.[44][45] Paul’s letters were circulated during his lifetime, and his death is thought to have occurred before 68 during Nero’s reign.[46][47] Early Christians transported these writings around the Empire, translating them into Old Syriac, Coptic, Ethiopic, and Latin, among other languages.[48]

Bart Ehrman explains how these multiple texts later became grouped by scholars into categories:

during the early centuries of the church, Christian texts were copied in whatever location they were written or taken to. Since texts were copied locally, it is no surprise that different localities developed different kinds of textual tradition. That is to say, the manuscripts in Rome had many of the same errors, because they were for the most part «in-house» documents, copied from one another; they were not influenced much by manuscripts being copied in Palestine; and those in Palestine took on their own characteristics, which were not the same as those found in a place like Alexandria, Egypt. Moreover, in the early centuries of the church, some locales had better scribes than others. Modern scholars have come to recognize that the scribes in Alexandria – which was a major intellectual center in the ancient world – were particularly scrupulous, even in these early centuries, and that there, in Alexandria, a very pure form of the text of the early Christian writings was preserved, decade after decade, by dedicated and relatively skilled Christian scribes.[49]

These differing histories produced what modern scholars refer to as recognizable «text types». The four most commonly recognized are Alexandrian, Western, Caesarean, and Byzantine.[50]

The list of books included in the Catholic Bible was established as canon by the Council of Rome in 382, followed by those of Hippo in 393 and Carthage in 397. Between 385 and 405 CE, the early Christian church translated its canon into Vulgar Latin (the common Latin spoken by ordinary people), a translation known as the Vulgate.[52] Since then, Catholic Christians have held ecumenical councils to standardize their biblical canon. The Council of Trent (1545–63), held by the Catholic Church in response to the Protestant Reformation, authorized the Vulgate as its official Latin translation of the Bible.[53] A number of biblical canons have since evolved. Christian biblical canons range from the 73 books of the Catholic Church canon, and the 66-book canon of most Protestant denominations, to the 81 books of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church canon, among others.[54] Judaism has long accepted a single authoritative text, whereas Christianity has never had an official version, instead having many different manuscript traditions.[55]

Variants

All biblical texts were treated with reverence and care by those that copied them, yet there are transmission errors, called variants, in all biblical manuscripts.[56][57] A variant is any deviation between two texts. Textual critic Daniel B. Wallace explains that «Each deviation counts as one variant, regardless of how many MSS [manuscripts] attest to it.»[58] Hebrew scholar Emanuel Tov says the term is not evaluative; it is a recognition that the paths of development of different texts have separated.[59]

Medieval handwritten manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible were considered extremely precise: the most authoritative documents from which to copy other texts.[60] Even so, David Carr asserts that Hebrew texts still contain some variants.[61] The majority of all variants are accidental, such as spelling errors, but some changes were intentional.[62] In the Hebrew text, «memory variants» are generally accidental differences evidenced by such things as the shift in word order found in 1 Chronicles 17:24 and 2 Samuel 10:9 and 13. Variants also include the substitution of lexical equivalents, semantic and grammar differences, and larger scale shifts in order, with some major revisions of the Masoretic texts that must have been intentional.[63]

Intentional changes in New Testament texts were made to improve grammar, eliminate discrepancies, harmonize parallel passages, combine and simplify multiple variant readings into one, and for theological reasons.[62][64] Bruce K. Waltke observes that one variant for every ten words was noted in the recent critical edition of the Hebrew Bible, the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, leaving 90% of the Hebrew text without variation. The fourth edition of the United Bible Society’s Greek New Testament notes variants affecting about 500 out of 6900 words, or about 7% of the text.[65]

Content and themes

Themes

The narratives, laws, wisdom sayings, parables, and unique genres of the Bible provide opportunity for discussion on most topics of concern to human beings: The role of women,[66]: 203 sex,[67] children, marriage,[68] neighbors,[69]: 24 friends, the nature of authority and the sharing of power,[70]: 45–48 animals, trees and nature,[71]: xi money and economics,[72]: 77 work, relationships,[73] sorrow and despair and the nature of joy, among others.[74] Philosopher and ethicist Jaco Gericke adds: «The meaning of good and evil, the nature of right and wrong, criteria for moral discernment, valid sources of morality, the origin and acquisition of moral beliefs, the ontological status of moral norms, moral authority, cultural pluralism, [as well as] axiological and aesthetic assumptions about the nature of value and beauty. These are all implicit in the texts.»[75]

However, discerning the themes of some biblical texts can be problematic.[76] Much of the Bible is in narrative form and in general, biblical narrative refrains from any kind of direct instruction, and in some texts the author’s intent is not easy to decipher.[77] It is left to the reader to determine good and bad, right and wrong, and the path to understanding and practice is rarely straightforward.[78] God is sometimes portrayed as having a role in the plot, but more often there is little about God’s reaction to events, and no mention at all of approval or disapproval of what the characters have done or failed to do.[79] The writer makes no comment, and the reader is left to infer what they will.[79] Jewish philosophers Shalom Carmy and David Schatz explain that the Bible «often juxtaposes contradictory ideas, without explanation or apology».[80]

The Hebrew Bible contains assumptions about the nature of knowledge, belief, truth, interpretation, understanding and cognitive processes.[81] Ethicist Michael V. Fox writes that the primary axiom of the book of Proverbs is that «the exercise of the human mind is the necessary and sufficient condition of right and successful behavior in all reaches of life».[82] The Bible teaches the nature of valid arguments, the nature and power of language, and its relation to reality.[75] According to Mittleman, the Bible provides patterns of moral reasoning that focus on conduct and character.[83][84]

In the biblical metaphysic, humans have free will, but it is a relative and restricted freedom.[85] Beach says that Christian voluntarism points to the will as the core of the self, and that within human nature, «the core of who we are is defined by what we love».[86] Natural law is in the Wisdom literature, the Prophets, Romans 1, Acts 17, and the book of Amos (Amos 1:3–2:5), where nations other than Israel are held accountable for their ethical decisions even though they don’t know the Hebrew god.[87] Political theorist Michael Walzer finds politics in the Hebrew Bible in covenant, law, and prophecy, which constitute an early form of almost democratic political ethics.[88] Key elements in biblical criminal justice begin with the belief in God as the source of justice and the judge of all, including those administering justice on earth.[89]

Carmy and Schatz say the Bible «depicts the character of God, presents an account of creation, posits a metaphysics of divine providence and divine intervention, suggests a basis for morality, discusses many features of human nature, and frequently poses the notorious conundrum of how God can allow evil.»[90]

Hebrew Bible

The authoritative Hebrew Bible is taken from the masoretic text (called the Leningrad Codex) which dates from 1008. The Hebrew Bible can therefore sometimes be referred to as the Masoretic Text.[91]

The Hebrew Bible is also known by the name Tanakh (Hebrew: תנ»ך). This reflects the threefold division of the Hebrew scriptures, Torah («Teaching»), Nevi’im («Prophets») and Ketuvim («Writings») by using the first letters of each word.[92] It is not until the Babylonian Talmud (c. 550 BCE) that a listing of the contents of these three divisions of scripture are found.[93]

The Tanakh was mainly written in Biblical Hebrew, with some small portions (Ezra 4:8–6:18 and 7:12–26, Jeremiah 10:11, Daniel 2:4–7:28)[94] written in Biblical Aramaic, a language which had become the lingua franca for much of the Semitic world.[95]

Torah

The Torah (תּוֹרָה) is also known as the «Five Books of Moses» or the Pentateuch, meaning «five scroll-cases».[96] Traditionally these books were considered to have been dictated to Moses by God himself.[97][98] Since the 17th century, scholars have viewed the original sources as being the product of multiple anonymous authors while also allowing the possibility that Moses first assembled the separate sources.[99][100] There are a variety of hypotheses regarding when and how the Torah was composed,[101] but there is a general consensus that it took its final form during the reign of the Persian Achaemenid Empire (probably 450–350 BCE),[102][103] or perhaps in the early Hellenistic period (333–164 BCE).[104]

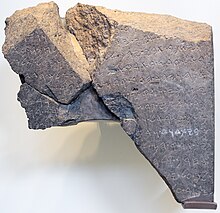

Samaritan Inscription containing portion of the Bible in nine lines of Hebrew text, currently housed in the British Museum

The Hebrew names of the books are derived from the first words in the respective texts. The Torah consists of the following five books:

- Genesis, Beresheeth (בראשית)

- Exodus, Shemot (שמות)

- Leviticus, Vayikra (ויקרא)

- Numbers, Bamidbar (במדבר)

- Deuteronomy, Devarim (דברים)

The first eleven chapters of Genesis provide accounts of the creation (or ordering) of the world and the history of God’s early relationship with humanity. The remaining thirty-nine chapters of Genesis provide an account of God’s covenant with the biblical patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (also called Israel) and Jacob’s children, the «Children of Israel», especially Joseph. It tells of how God commanded Abraham to leave his family and home in the city of Ur, eventually to settle in the land of Canaan, and how the Children of Israel later moved to Egypt.

The remaining four books of the Torah tell the story of Moses, who lived hundreds of years after the patriarchs. He leads the Children of Israel from slavery in ancient Egypt to the renewal of their covenant with God at Mount Sinai and their wanderings in the desert until a new generation was ready to enter the land of Canaan. The Torah ends with the death of Moses.[105]

The commandments in the Torah provide the basis for Jewish religious law. Tradition states that there are 613 commandments (taryag mitzvot).

Nevi’im

Nevi’im (Hebrew: נְבִיאִים, romanized: Nəḇî’îm, «Prophets») is the second main division of the Tanakh, between the Torah and Ketuvim. It contains two sub-groups, the Former Prophets (Nevi’im Rishonim נביאים ראשונים, the narrative books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings) and the Latter Prophets (Nevi’im Aharonim נביאים אחרונים, the books of Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel and the Twelve Minor Prophets).

The Nevi’im tell a story of the rise of the Hebrew monarchy and its division into two kingdoms, the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah, focusing on conflicts between the Israelites and other nations, and conflicts among Israelites, specifically, struggles between believers in «the LORD God»[106] (Yahweh) and believers in foreign gods,[c][d] and the criticism of unethical and unjust behaviour of Israelite elites and rulers;[e][f][g] in which prophets played a crucial and leading role. It ends with the conquest of the Kingdom of Israel by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, followed by the conquest of the Kingdom of Judah by the neo-Babylonian Empire and the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem.

Former Prophets

The Former Prophets are the books Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings. They contain narratives that begin immediately after the death of Moses with the divine appointment of Joshua as his successor, who then leads the people of Israel into the Promised Land, and end with the release from imprisonment of the last king of Judah. Treating Samuel and Kings as single books, they cover:

- Joshua’s conquest of the land of Canaan (in the Book of Joshua),

- the struggle of the people to possess the land (in the Book of Judges),

- the people’s request to God to give them a king so that they can occupy the land in the face of their enemies (in the Books of Samuel)

- the possession of the land under the divinely appointed kings of the House of David, ending in conquest and foreign exile (Books of Kings)

Latter Prophets

The Latter Prophets are Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and the Twelve Minor Prophets, counted as a single book.

- Hosea, Hoshea (הושע) denounces the worship of gods other than Yehovah, comparing Israel to a woman being unfaithful to her husband.

- Joel, Yoel (יואל) includes a lament and a promise from God.

- Amos, Amos (עמוס) speaks of social justice, providing a basis for natural law by applying it to unbelievers and believers alike.

- Obadiah, Ovadyah (עבדיה) addresses the judgment of Edom and restoration of Israel.

- Jonah, Yonah (יונה) tells of a reluctant redemption of Ninevah.

- Micah, Mikhah (מיכה) reproaches unjust leaders, defends the rights of the poor, and looks forward to world peace.

- Nahum, Nahum (נחום) speaks of the destruction of Nineveh.

- Habakkuk, Havakuk (חבקוק) upholds trust in God over Babylon.

- Zephaniah, Tsefanya (צפניה) pronounces coming of judgment, survival and triumph of remnant.

- Haggai, Khagay (חגי) rebuild Second Temple.

- Zechariah, Zekharyah (זכריה) God blesses those who repent and are pure.

- Malachi, Malakhi (מלאכי) corrects lax religious and social behaviour.

Ketuvim

Ketuvim or Kəṯûḇîm (in Biblical Hebrew: כְּתוּבִים «writings») is the third and final section of the Tanakh. The Ketuvim are believed to have been written under the inspiration of Ruach HaKodesh (the Holy Spirit) but with one level less authority than that of prophecy.[107]

In Masoretic manuscripts (and some printed editions), Psalms, Proverbs and Job are presented in a special two-column form emphasizing their internal parallelism, which was found early in the study of Hebrew poetry. «Stichs» are the lines that make up a verse «the parts of which lie parallel as to form and content».[108] Collectively, these three books are known as Sifrei Emet (an acronym of the titles in Hebrew, איוב, משלי, תהלים yields Emet אמ»ת, which is also the Hebrew for «truth»). Hebrew cantillation is the manner of chanting ritual readings as they are written and notated in the Masoretic Text of the Bible. Psalms, Job and Proverbs form a group with a «special system» of accenting used only in these three books.[109]

The five scrolls

The five relatively short books of Song of Songs, Book of Ruth, the Book of Lamentations, Ecclesiastes and Book of Esther are collectively known as the Hamesh Megillot. These are the latest books collected and designated as «authoritative» in the Jewish canon even though they were not complete until the second century CE.[110]

Other books

The books of Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah[h] and Chronicles share a distinctive style that no other Hebrew literary text, biblical or extra-biblical, shares.[111] They were not written in the normal style of Hebrew of the post-exilic period. The authors of these books must have chosen to write in their own distinctive style for unknown reasons.[112]

- Their narratives all openly describe relatively late events (i.e., the Babylonian captivity and the subsequent restoration of Zion).

- The Talmudic tradition ascribes late authorship to all of them.

- Two of them (Daniel and Ezra) are the only books in the Tanakh with significant portions in Aramaic.

Book order

The following list presents the books of Ketuvim in the order they appear in most current printed editions.

- Tehillim (Psalms) תְהִלִּים is an anthology of individual Hebrew religious hymns.

- Mishlei (Book of Proverbs) מִשְלֵי is a «collection of collections» on values, moral behavior, the meaning of life and right conduct, and its basis in faith.

- Iyyôbh (Book of Job) אִיּוֹב is about faith, without understanding or justifying suffering.

- Shīr Hashshīrīm (Song of Songs) or (Song of Solomon) שִׁיר הַשִׁירִים (Passover) is poetry about love and sex.

- Rūth (Book of Ruth) רוּת (Shābhû‘ôth) tells of the Moabite woman Ruth, who decides to follow the God of the Israelites, and remains loyal to her mother-in-law, who is then rewarded.

- Eikhah (Lamentations) איכה (Ninth of Av) [Also called Kinnot in Hebrew.] is a collection of poetic laments for the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BCE.

- Qōheleth (Ecclesiastes) קהלת (Sukkôth) contains wisdom sayings disagreed over by scholars. Is it positive and life-affirming, or deeply pessimistic?

- Estēr (Book of Esther) אֶסְתֵר (Pûrîm) tells of a Hebrew woman in Persia who becomes queen and thwarts a genocide of her people.

- Dānî’ēl (Book of Daniel) דָּנִיֵּאל combines prophecy and eschatology (end times) in story of God saving Daniel just as He will save Israel.

- ‘Ezrā (Book of Ezra–Book of Nehemiah) עזרא tells of rebuilding the walls of Jerusalem after the Babylonian exile.

- Divrei ha-Yamim (Chronicles) דברי הימים contains genealogy.

The Jewish textual tradition never finalized the order of the books in Ketuvim. The Babylonian Talmud (Bava Batra 14b–15a) gives their order as Ruth, Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon, Lamentations of Jeremiah, Daniel, Scroll of Esther, Ezra, Chronicles.[113]

One of the large scale differences between the Babylonian and the Tiberian biblical traditions is the order of the books. Isaiah is placed after Ezekiel in the Babylonian, while Chronicles opens the Ketuvim in the Tiberian, and closes it in the Babylonian.[114]

The Ketuvim is the last of the three portions of the Tanakh to have been accepted as canonical. While the Torah may have been considered canon by Israel as early as the fifth century BCE and the Former and Latter Prophets were canonized by the second century BCE, the Ketuvim was not a fixed canon until the second century CE.[110]

Evidence suggests, however, that the people of Israel were adding what would become the Ketuvim to their holy literature shortly after the canonization of the prophets. As early as 132 BCE references suggest that the Ketuvim was starting to take shape, although it lacked a formal title.[115] Against Apion, the writing of Josephus in 95 CE, treated the text of the Hebrew Bible as a closed canon to which «… no one has ventured either to add, or to remove, or to alter a syllable…»[116] For an extended period after 95CE, the divine inspiration of Esther, the Song of Songs, and Ecclesiastes was often under scrutiny.[117]

Septuagint

The Septuagint («the Translation of the Seventy», also called «the LXX»), is a Koine Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible begun in the late third century BCE.

As the work of translation progressed, the Septuagint expanded: the collection of prophetic writings had various hagiographical works incorporated into it. In addition, some newer books such as the Books of the Maccabees and the Wisdom of Sirach were added. These are among the «apocryphal» books, (books whose authenticity is doubted). The inclusion of these texts, and the claim of some mistranslations, contributed to the Septuagint being seen as a «careless» translation and its eventual rejection as a valid Jewish scriptural text.[118][119][i]

The apocrypha are Jewish literature, mostly of the Second Temple period (c. 550 BCE – 70 CE); they originated in Israel, Syria, Egypt or Persia; were originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek, and attempt to tell of biblical characters and themes.[121] Their provenance is obscure. One older theory of where they came from asserted that an «Alexandrian» canon had been accepted among the Greek-speaking Jews living there, but that theory has since been abandoned.[122] Indications are that they were not accepted when the rest of the Hebrew canon was.[122] It is clear the Apocrypha were used in New Testament times, but «they are never quoted as Scripture.»[123] In modern Judaism, none of the apocryphal books are accepted as authentic and are therefore excluded from the canon. However, «the Ethiopian Jews, who are sometimes called Falashas, have an expanded canon, which includes some Apocryphal books».[124]

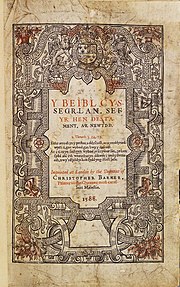

The contents page in a complete 80 book King James Bible, listing «The Books of the Old Testament», «The Books called Apocrypha», and «The Books of the New Testament».

The rabbis also wanted to distinguish their tradition from the newly emerging tradition of Christianity.[a][j] Finally, the rabbis claimed a divine authority for the Hebrew language, in contrast to Aramaic or Greek – even though these languages were the lingua franca of Jews during this period (and Aramaic would eventually be given the status of a sacred language comparable to Hebrew).[k]

Incorporations from Theodotion

The Book of Daniel is preserved in the 12-chapter Masoretic Text and in two longer Greek versions, the original Septuagint version, c. 100 BCE, and the later Theodotion version from c. second century CE. Both Greek texts contain three additions to Daniel: The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children; the story of Susannah and the Elders; and the story of Bel and the Dragon. Theodotion’s translation was so widely copied in the Early Christian church that its version of the Book of Daniel virtually superseded the Septuagint’s. The priest Jerome, in his preface to Daniel (407 CE), records the rejection of the Septuagint version of that book in Christian usage: «I … wish to emphasize to the reader the fact that it was not according to the Septuagint version but according to the version of Theodotion himself that the churches publicly read Daniel.»[125] Jerome’s preface also mentions that the Hexapla had notations in it, indicating several major differences in content between the Theodotion Daniel and the earlier versions in Greek and Hebrew.

Theodotion’s Daniel is closer to the surviving Hebrew Masoretic Text version, the text which is the basis for most modern translations. Theodotion’s Daniel is also the one embodied in the authorised edition of the Septuagint published by Sixtus V in 1587.[126]

Final form

Textual critics are now debating how to reconcile the earlier view of the Septuagint as ‘careless’ with content from the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran, scrolls discovered at Wadi Murabba’at, Nahal Hever, and those discovered at Masada. These scrolls are 1000–1300 years older than the Leningrad text, dated to 1008 CE, which forms the basis of the Masoretic text.[127] The scrolls have confirmed much of the Masoretic text, but they have also differed from it, and many of those differences agree with the Septuagint, the Samaritan Pentateuch or the Greek Old Testament instead.[118]

Copies of some texts later declared apocryphal are also among the Qumran texts.[122] Ancient manuscripts of the book of Sirach, the «Psalms of Joshua», Tobit, and the Epistle of Jeremiah are now known to have existed in a Hebrew version.[128] The Septuagint version of some biblical books, such as the Book of Daniel and Book of Esther, are longer than those in the Jewish canon.[129] In the Septuagint, Jeremiah is shorter than in the Masoretic text, but a shortened Hebrew Jeremiah has been found at Qumran in cave 4.[118] The scrolls of Isaiah, Exodus, Jeremiah, Daniel and Samuel exhibit striking and important textual variants from the Masoretic text.[118] The Septuagint is now seen as a careful translation of a different Hebrew form or recension (revised addition of the text) of certain books, but debate on how best to characterize these varied texts is ongoing.[118]

Pseudepigraphal books

Pseudepigrapha are works whose authorship is wrongly attributed. A written work can be pseudepigraphical and not be a forgery, as forgeries are intentionally deceptive. With pseudepigrapha, authorship has been mistransmitted for any one of a number of reasons.[130]

Apocryphal and pseudepigraphic works are not the same. Apocrypha includes all the writings claiming to be sacred that are outside the canon because they are not accepted as authentically being what they claim to be. For example, the Gospel of Barnabas claims to be written by Barnabas the companion of the Apostle Paul, but both its manuscripts date from the Middle Ages. Pseudepigrapha is a literary category of all writings whether they are canonical or apocryphal. They may or may not be authentic in every sense except a misunderstood authorship.[130]

The term «pseudepigrapha» is commonly used to describe numerous works of Jewish religious literature written from about 300 BCE to 300 CE. Not all of these works are actually pseudepigraphical. (It also refers to books of the New Testament canon whose authorship is questioned.) The Old Testament pseudepigraphal works include the following:[131]

- 3 Maccabees

- 4 Maccabees

- Assumption of Moses

- Ethiopic Book of Enoch (1 Enoch)

- Slavonic Book of Enoch (2 Enoch)

- Hebrew Book of Enoch (3 Enoch) (also known as «The Revelation of Metatron» or «The Book of Rabbi Ishmael the High Priest»)

- Book of Jubilees

- Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch (2 Baruch)

- Letter of Aristeas (Letter to Philocrates regarding the translating of the Hebrew scriptures into Greek)

- Life of Adam and Eve

- Martyrdom and Ascension of Isaiah

- Psalms of Solomon

- Sibylline Oracles

- Greek Apocalypse of Baruch (3 Baruch)

- Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs

Book of Enoch

Notable pseudepigraphal works include the Books of Enoch such as 1 Enoch, 2 Enoch, which survives only in Old Slavonic, and 3 Enoch, surviving in Hebrew of the c. fifth century – c. sixth century CE. These are ancient Jewish religious works, traditionally ascribed to the prophet Enoch, the great-grandfather of the patriarch Noah. The fragment of Enoch found among the Qumran scrolls attest to it being an ancient work.[132] The older sections (mainly in the Book of the Watchers) are estimated to date from about 300 BCE, and the latest part (Book of Parables) was probably composed at the end of the first century BCE.[133]

Enoch is not part of the biblical canon used by most Jews, apart from Beta Israel. Most Christian denominations and traditions may accept the Books of Enoch as having some historical or theological interest or significance. Part of the Book of Enoch is quoted in the Epistle of Jude and the book of Hebrews (parts of the New Testament), but Christian denominations generally regard the Books of Enoch as non-canonical.[134] The exceptions to this view are the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church.[132]

The Ethiopian Bible is not based on the Greek Bible, and the Ethiopian Church has a slightly different understanding of canon than other Christian traditions.[135] In Ethiopia, canon does not have the same degree of fixedness, (yet neither is it completely open).[135] Enoch has long been seen there as inspired scripture, but being scriptural and being canon are not always seen the same. The official Ethiopian canon has 81 books, but that number is reached in different ways with various lists of different books, and the book of Enoch is sometimes included and sometimes not.[135] Current evidence confirms Enoch as canonical in both Ethiopia and in Eritrea.[132]

Christian Bible

A Christian Bible is a set of books divided into the Old and New Testament that a Christian denomination has, at some point in their past or present, regarded as divinely inspired scripture by the holy spirit.[136] The Early Church primarily used the Septuagint, as it was written in Greek, the common tongue of the day, or they used the Targums among Aramaic speakers. Modern English translations of the Old Testament section of the Christian Bible are based on the Masoretic Text.[34] The Pauline epistles and the gospels were soon added, along with other writings, as the New Testament.[137]

Old Testament

The Old Testament has been important to the life of the Christian church from its earliest days. Bible scholar N.T. Wright says «Jesus himself was profoundly shaped by the scriptures.»[138] Wright adds that the earliest Christians searched those same Hebrew scriptures in their effort to understand the earthly life of Jesus. They regarded the «holy writings» of the Israelites as necessary and instructive for the Christian, as seen from Paul’s words to Timothy (2 Timothy 3:15), as pointing to the Messiah, and as having reached a climactic fulfillment in Jesus generating the «new covenant» prophesied by Jeremiah.[139]

The Protestant Old Testament of the twenty-first century has a 39-book canon – the number of books (although not the content) varies from the Jewish Tanakh only because of a different method of division. The term «Hebrew scriptures» is often used as being synonymous with the Protestant Old Testament, since the surviving scriptures in Hebrew include only those books.

However, the Roman Catholic Church recognizes 46 books as its Old Testament (45 if Jeremiah and Lamentations are counted as one),[140] and the Eastern Orthodox Churches recognize 6 additional books. These additions are also included in the Syriac versions of the Bible called the Peshitta and the Ethiopian Bible.[l][m][n]

Because the canon of Scripture is distinct for Jews, Orthodox Christians, Roman Catholics, and Protestants, the contents of each community’s Apocrypha are unique, as is its usage of the term. For Jews, none of the apocryphal books are considered canonical. Catholics refer to this collection as «Deuterocanonical books» (second canon) and the Orthodox Church refers to them as «Anagignoskomena» (that which is read).[141] [o]

Books included in the Roman Catholic, Greek, and Slavonic Bibles are: Tobit, Judith, Greek Additions to Esther, the Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach (or Ecclesiasticus), Baruch, the Letter of Jeremiah (also called the Baruch Chapter 6), the Greek Additions to Daniel, along with 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees.[142]

The Greek Orthodox Church, and the Slavonic churches (Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Ukraine, Russia, Serbia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia and Croatia) also add:[143]

- 3 Maccabees

- 1 Esdras (called 2 Esdras in the Slavonic canon)

- Prayer of Manasseh

- Psalm 151

2 Esdras (4 Ezra) and the Prayer of Manasseh are not in the Septuagint, and 2 Esdras does not exist in Greek, though it does exist in Latin. There is also 4 Maccabees which is only accepted as canonical in the Georgian Church. It is in an appendix to the Greek Orthodox Bible, and it is therefore sometimes included in collections of the Apocrypha.[144]

The Syriac Orthodox Church also includes:

- Psalms 151–155

- The Apocalypse of Baruch

- The Letter of Baruch[145]

The Ethiopian Old Testament Canon uses Enoch and Jubilees (that only survived in Ge’ez), 1–3 Meqabyan, Greek Ezra and the Apocalypse of Ezra, and Psalm 151.[n][l]

The Revised Common Lectionary of the Lutheran Church, Moravian Church, Reformed Churches, Anglican Church and Methodist Church uses the apocryphal books liturgically, with alternative Old Testament readings available.[p] Therefore, editions of the Bible intended for use in the Lutheran Church and Anglican Church include the fourteen books of the Apocrypha, many of which are the deuterocanonical books accepted by the Catholic Church, plus 1 Esdras, 2 Esdras and the Prayer of Manasseh, which were in the Vulgate appendix.[147]

The Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches use most of the books of the Septuagint, while Protestant churches usually do not. After the Protestant Reformation, many Protestant Bibles began to follow the Jewish canon and exclude the additional texts, which came to be called apocryphal. The Apocrypha are included under a separate heading in the King James Version of the Bible, the basis for the Revised Standard Version.[148]

| The Orthodox Old Testament[149][q] |

Greek-based name |

Conventional English name |

| Law | ||

|---|---|---|

| Γένεσις | Génesis | Genesis |

| Ἔξοδος | Éxodos | Exodus |

| Λευϊτικόν | Leuitikón | Leviticus |

| Ἀριθμοί | Arithmoí | Numbers |

| Δευτερονόμιον | Deuteronómion | Deuteronomy |

| History | ||

| Ἰησοῦς Nαυῆ | Iêsous Nauê | Joshua |

| Κριταί | Kritaí | Judges |

| Ῥούθ | Roúth | Ruth |

| Βασιλειῶν Αʹ[r] | I Reigns | I Samuel |

| Βασιλειῶν Βʹ | II Reigns | II Samuel |

| Βασιλειῶν Γʹ | III Reigns | I Kings |

| Βασιλειῶν Δʹ | IV Reigns | II Kings |

| Παραλειπομένων Αʹ | I Paralipomenon[s] | I Chronicles |

| Παραλειπομένων Βʹ | II Paralipomenon | II Chronicles |

| Ἔσδρας Αʹ | I Esdras | 1 Esdras |

| Ἔσδρας Βʹ | II Esdras | Ezra–Nehemiah |

| Τωβίτ[t] | Tobit | Tobit or Tobias |

| Ἰουδίθ | Ioudith | Judith |

| Ἐσθήρ | Esther | Esther with additions |

| Μακκαβαίων Αʹ | I Makkabaioi | 1 Maccabees |

| Μακκαβαίων Βʹ | II Makkabaioi | 2 Maccabees |

| Μακκαβαίων Γʹ | III Makkabaioi | 3 Maccabees |

| Wisdom | ||

| Ψαλμοί | Psalms | Psalms |

| Ψαλμός ΡΝΑʹ | Psalm 151 | Psalm 151 |

| Προσευχὴ Μανάσση | Prayer of Manasseh | Prayer of Manasseh |

| Ἰώβ | Iōb | Job |

| Παροιμίαι | Proverbs | Proverbs |

| Ἐκκλησιαστής | Ekklesiastes | Ecclesiastes |

| Ἆσμα Ἀσμάτων | Song of Songs | Song of Solomon or Canticles |

| Σοφία Σαλoμῶντος | Wisdom of Solomon | Wisdom |

| Σοφία Ἰησοῦ Σειράχ | Wisdom of Jesus the son of Seirach | Sirach or Ecclesiasticus |

| Ψαλμοί Σαλoμῶντος | Psalms of Solomon | Psalms of Solomon[u] |

| Prophets | ||

| Δώδεκα | The Twelve | Minor Prophets |

| Ὡσηέ Αʹ | I. Osëe | Hosea |

| Ἀμώς Βʹ | II. Amōs | Amos |

| Μιχαίας Γʹ | III. Michaias | Micah |

| Ἰωήλ Δʹ | IV. Ioël | Joel |

| Ὀβδίου Εʹ[v] | V. Obdias | Obadiah |

| Ἰωνᾶς Ϛ’ | VI. Ionas | Jonah |

| Ναούμ Ζʹ | VII. Naoum | Nahum |

| Ἀμβακούμ Ηʹ | VIII. Ambakum | Habakkuk |

| Σοφονίας Θʹ | IX. Sophonias | Zephaniah |

| Ἀγγαῖος Ιʹ | X. Angaios | Haggai |

| Ζαχαρίας ΙΑʹ | XI. Zacharias | Zachariah |

| Ἄγγελος ΙΒʹ | XII. Messenger | Malachi |

| Ἠσαΐας | Hesaias | Isaiah |

| Ἱερεμίας | Hieremias | Jeremiah |

| Βαρούχ | Baruch | Baruch |

| Θρῆνοι | Lamentations | Lamentations |

| Ἐπιστολή Ιερεμίου | Epistle of Jeremiah | Letter of Jeremiah |

| Ἰεζεκιήλ | Iezekiêl | Ezekiel |

| Δανιήλ | Daniêl | Daniel with additions |

| Appendix | ||

| Μακκαβαίων Δ’ Παράρτημα | IV Makkabees | 4 Maccabees[w] |

New Testament

The New Testament is the name given to the second portion of the Christian Bible. While some scholars assert that Aramaic was the original language of the New Testament,[151] the majority view says it was written in the vernacular form of Koine Greek. Still, there is reason to assert that it is a heavily Semitized Greek: its syntax is like conversational Greek, but its style is largely Semitic.[152][x][y] Koina Greek was the common language of the western Roman Empire from the Conquests of Alexander the Great (335–323 BCE) until the evolution of Byzantine Greek (c. 600) while Aramaic was the language of Jesus, the Apostles and the ancient Near East.[151][z][aa][ab] The term «New Testament» came into use in the second century during a controversy over whether the Hebrew Bible should be included with the Christian writings as sacred scripture.[153]

St. Jerome in His Study, by Marinus van Reymerswaele, 1541. Jerome produced a fourth-century Latin edition of the Bible, known as the Vulgate, that became the Catholic Church’s official translation.

It is generally accepted that the New Testament writers were Jews who took the inspiration of the Old Testament for granted. This is probably stated earliest in 2 Timothy 3:16: «All scripture is given by inspiration of God». Scholarship on how and why ancient Jewish–Christians came to create and accept new texts as equal to the established Hebrew texts has taken three forms. First, John Barton writes that ancient Christians probably just continued the Jewish tradition of writing and incorporating what they believed were inspired, authoritative religious books.[154] The second approach separates those various inspired writings based on a concept of «canon» which developed in the second century.[155] The third involves formalizing canon.[156] According to Barton, these differences are only differences in terminology; the ideas are reconciled if they are seen as three stages in the formation of the New Testament.[157]

The first stage was completed remarkably early if one accepts Albert C. Sundberg [de]‘s view that «canon» and «scripture» are separate things, with «scripture» having been recognized by ancient Christians long before «canon» was.[158] Barton says Theodor Zahn concluded «there was already a Christian canon by the end of the first century», but this is not the canon of later centuries.[159] Accordingly, Sundberg asserts that in the first centuries, there was no criterion for inclusion in the «sacred writings» beyond inspiration, and that no one in the first century had the idea of a closed canon.[160] The gospels were accepted by early believers as handed down from those Apostles who had known Jesus and been taught by him.[161] Later biblical criticism has questioned the authorship and datings of the gospels.

At the end of the second century, it is widely recognized that a Christian canon similar to its modern version was asserted by the church fathers in response to the plethora of writings claiming inspiration that contradicted orthodoxy: (heresy).[162] The third stage of development as the final canon occurred in the fourth century with a series of synods that produced a list of texts of the canon of the Old Testament and the New Testament that are still used today. Most notably the Synod of Hippo in 393 CE and that of c. 400. Jerome produced a definitive Latin edition of the Bible (the Vulgate), the canon of which, at the insistence of the Pope, was in accord with the earlier Synods. This process effectively set the New Testament canon.

New Testament books already had considerable authority in the late first and early second centuries.[163] Even in its formative period, most of the books of the NT that were seen as scripture were already agreed upon. Linguistics scholar Stanley E. Porter says «evidence from the apocryphal non-Gospel literature is the same as that for the apocryphal Gospels – in other words, that the text of the Greek New Testament was relatively well established and fixed by the time of the second and third centuries».[164] By the time the fourth century Fathers were approving the «canon», they were doing little more than codifying what was already universally accepted.[165]

The New Testament is a collection of 27 books[166] of 4 different genres of Christian literature (Gospels, one account of the Acts of the Apostles, Epistles and an Apocalypse). These books can be grouped into:

The Gospels are narratives of Jesus’ last three years of life, his death and resurrection.

- Synoptic Gospels

- Gospel of Matthew

- Gospel of Mark

- Gospel of Luke

- Gospel of John

Narrative literature, provide an account and history of the very early Apostolic age.

- Acts of the Apostles

Pauline epistles are written to individual church groups to address problems, provide encouragement and give instruction.

- Epistle to the Romans

- First Epistle to the Corinthians

- Second Epistle to the Corinthians

- Epistle to the Galatians

- Epistle to the Ephesians

- Epistle to the Philippians

- Epistle to the Colossians

- First Epistle to the Thessalonians

- Second Epistle to the Thessalonians

Pastoral epistles discuss the pastoral oversight of churches, Christian living, doctrine and leadership.

- First Epistle to Timothy

- Second Epistle to Timothy

- Epistle to Titus

- Epistle to Philemon

- Epistle to the Hebrews

Catholic epistles, also called the general epistles or lesser epistles.

- Epistle of James encourages a lifestyle consistent with faith.

- First Epistle of Peter addresses trial and suffering.

- Second Epistle of Peter more on suffering’s purposes, Christology, ethics and eschatology.

- First Epistle of John covers how to discern true Christians: by their ethics, their proclamation of Jesus in the flesh, and by their love.

- Second Epistle of John warns against docetism.

- Third Epistle of John encourage, strengthen and warn.

- Epistle of Jude condemns opponents.

Apocalyptic literature

- Book of Revelation, or the Apocalypse, predicts end time events.

Both Catholics and Protestants (as well as Greek Orthodox) currently have the same 27-book New Testament Canon. They are ordered differently in the Slavonic tradition, the Syriac tradition and the Ethiopian tradition.[167]

Canon variations

Peshitta

The Peshitta (Classical Syriac: ܦܫܺܝܛܬܳܐ or ܦܫܝܼܛܬܵܐ pšīṭtā) is the standard version of the Bible for churches in the Syriac tradition. The consensus within biblical scholarship, although not universal, is that the Old Testament of the Peshitta was translated into Syriac from biblical Hebrew, probably in the 2nd century CE, and that the New Testament of the Peshitta was translated from the Greek.[ac] This New Testament, originally excluding certain disputed books (2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, Jude, Revelation), had become a standard by the early 5th century. The five excluded books were added in the Harklean Version (616 CE) of Thomas of Harqel.[ad][151]

Catholic Church canon

The canon of the Catholic Church was affirmed by the Council of Rome (AD 382), the Synod of Hippo (in AD 393), the Council of Carthage (AD 397), the Council of Carthage (AD 419), the Council of Florence (AD 1431–1449) and finally, as an article of faith, by the Council of Trent (AD 1545–1563) establishing the canon consisting of 46 books in the Old Testament and 27 books in the New Testament for a total of 73 books in the Catholic Bible.[168][169][ae]

Ethiopian Orthodox canon

The canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church is wider than the canons used by most other Christian churches. There are 81 books in the Ethiopian Orthodox Bible.[171] In addition to the books found in the Septuagint accepted by other Orthodox Christians, the Ethiopian Old Testament Canon uses Enoch and Jubilees (ancient Jewish books that only survived in Ge’ez, but are quoted in the New Testament),[142] Greek Ezra and the Apocalypse of Ezra, 3 books of Meqabyan, and Psalm 151 at the end of the Psalter.[n][l] The three books of Meqabyan are not to be confused with the books of Maccabees. The order of the books is somewhat different in that the Ethiopian Old Testament follows the Septuagint order for the Minor Prophets rather than the Jewish order.[171]

Influence

With a literary tradition spanning two millennia, the Bible is one of the most influential works ever written. From practices of personal hygiene to philosophy and ethics, the Bible has directly and indirectly influenced politics and law, war and peace, sexual morals, marriage and family life, letters and learning, the arts, economics, social justice, medical care and more.[172]

The Bible is one of the world’s most published books, with estimated total sales of over five billion copies.[173] As such, the Bible has had a profound influence, especially in the Western world,[174][175] where the Gutenberg Bible was the first book printed in Europe using movable type.[176] It has contributed to the formation of Western law, art, literature, and education.[177]

Criticism

Critics view certain biblical texts to be morally problematic. The Bible neither calls for nor condemns slavery outright, but there are verses that address dealing with it, and these verses have been used to support it. Some have written that supersessionism begins in the book of Hebrews where others locate its beginnings in the culture of the fourth century Roman empire.[178]: 1 The Bible has been used to support the death penalty, patriarchy, sexual intolerance, the violence of total war, and colonialism.

In the Christian Bible, the violence of war is addressed four ways: pacifism, non-resistance; just war, and preventive war which is sometimes called crusade.[179]: 13–37 In the Hebrew Bible, there is just war and preventive war which includes the Amalekites, Canaanites, Moabites, and the record in Exodus, Deuteronomy, Joshua, and both books of Kings.[180] John J. Collins writes that people throughout history have used these biblical texts to justify violence against their enemies.[181] Anthropologist Leonard B. Glick offers the modern example of Jewish fundamentalists in Israel, such as Shlomo Aviner a prominent theorist of the Gush Emunim movement, who considers the Palestinians to be like biblical Canaanites, and therefore suggests that Israel «must be prepared to destroy» the Palestinians if the Palestinians do not leave the land.[182]

Nur Masalha argues that genocide is inherent in these commandments, and that they have served as inspirational examples of divine support for slaughtering national opponents.[183] However, the «applicability of the term [genocide] to earlier periods of history» is questioned by sociologists Frank Robert Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn.[184] Since most societies of the past endured and practiced genocide, it was accepted at that time as «being in the nature of life» because of the «coarseness and brutality» of life; the moral condemnation associated with terms like genocide are products of modern morality.[184]: 27 The definition of what constitutes violence has broadened considerably over time.[185]: 1–2 The Bible reflects how perceptions of violence changed for its authors.[185]: 261