Not to be confused with Angle.

This article is about the supernatural beings. For other uses, see Angel (disambiguation).

In various theistic religious traditions, an angel is a supernatural spiritual being who serves God.

Abrahamic religions often depict angels as benevolent celestial intermediaries between God (or Heaven) and humanity.[1][2] Other roles include protectors and guides for humans, such as guardian angels, and servants of God.[3] Abrahamic religions describe angelic hierarchies, which vary by religion and sect. Some angels have specific names (such as Gabriel or Michael) or titles (such as seraph or archangel). Those expelled from Heaven are called fallen angels, distinct from the heavenly host.

Angels in art are usually shaped like humans of extraordinary beauty, though this is not always the case—sometimes, they can be portrayed in a frightening, inhuman manner.[4] They are often identified in Christian artwork with bird wings,[5] halos,[6] and divine light.

Etymology[edit]

The word angel arrives in modern English from Old English engel (with a hard g) and the Old French angele.[7] Both of these derive from Late Latin angelus, which in turn was borrowed from Late Greek ἄγγελος angelos (literally «messenger»).[8] Τhe word’s earliest form is Mycenaean a-ke-ro, attested in Linear B syllabic script.[9] According to the Dutch linguist R. S. P. Beekes, ángelos itself may be «an Oriental loan, like ἄγγαρος (ángaros, ‘Persian mounted courier’).»[10]

The rendering of «ángelos» is the Septuagint’s default translation of the Biblical Hebrew term malʼākh, denoting simply «messenger» without connoting its nature. In the Latin Vulgate, this meaning becomes bifurcated: when malʼākh or ángelos is supposed to denote a human messenger, words like nuntius or legatus are applied. If the word refers to some supernatural being, the word angelus appears. Such differentiation has been taken over by later vernacular translations of the Bible, early Christian and Jewish exegetes and eventually modern scholars.[11]

Zoroastrianism[edit]

In Zoroastrianism there are different angel-like figures. For example, each person has one guardian angel, called Fravashi. They patronize human beings and other creatures, and also manifest God’s energy. The Amesha Spentas have often been regarded as angels, although there is no direct reference to them conveying messages,[12] but are rather emanations of Ahura Mazda («Wise Lord», God); they initially appeared in an abstract fashion and then later became personalized, associated with various aspects of creation.[13]

Abrahamic religions[edit]

Judaism[edit]

In Judaism, angels (Hebrew: מַלְאָךְ mal’āḵ; «messenger»), are understood through interpretation of the Tanakh and in a long tradition as supernatural beings who stand by God in heaven, but are strictly to be distinguished from God (YHWH) and are subordinate to him. Occasionally, they can show selected people God’s will and instructions.[14] In the Jewish tradition they are also inferior to humans since they have no will of their own and are able to carry out only one divine command.[15]

Hebrew Bible[edit]

The Torah uses the Hebrew terms מלאך אלהים (mal’āk̠ ‘ĕlōhîm; «messenger of God»), מלאך יהוה (mal’āk̠ Yahweh; «messenger of the Lord»), בני אלהים (bənē ‘ĕlōhîm; «sons of God») and הקודשים (haqqôd̠əšîm; «the holy ones») to refer to beings traditionally interpreted as angels. Later texts use other terms, such as העליונים (hā’elyônîm; «the upper ones»).[citation needed]

The term ‘מלאך’ (‘mal’āk̠’) is also used in other books of the Hebrew Bible. Depending on the context, the Hebrew word may refer to a human messenger or to a supernatural messenger. A human messenger might be a prophet or priest, such as Malachi, «my messenger»; the Greek superscription in the Septuagint translation states the Book of Malachi was written «by the hand of his messenger» ἀγγέλου (angélu). Examples of a supernatural messenger[16] are the «Malak YHWH,» who is either a messenger from God,[17] an aspect of God (such as the logos),[18] or God himself as the messenger (the «theophanic angel.»)[16][19]

Michael D. Coogan notes that it is only in the late books that the terms «come to mean the benevolent semi-divine beings familiar from later mythology and art.»[20] Daniel is the biblical book to refer to individual angels by name,[21] mentioning Gabriel in Daniel 9:21 and Michael in Daniel 10:13. These angels are part of Daniel’s apocalyptic visions and are an important part of apocalyptic literature.[20][22]

In Daniel 7, Daniel receives a dream-vision from God. […] As Daniel watches, the Ancient of Days takes his seat on the throne of heaven and sits in judgement in the midst of the heavenly court […] an [angel] like a son of man approaches the Ancient One in the clouds of heaven and is given everlasting kingship.[23]

Coogan explains the development of this concept of angels: «In the postexilic period, with the development of explicit monotheism, these divine beings—the ‘sons of God’ who were members of the Divine Council—were in effect demoted to what are now known as ‘angels’, understood as beings created by God, but immortal and thus superior to humans.»[20] This conception of angels is best understood in contrast to demons and is often thought to be «influenced by the ancient Persian religious tradition of Zoroastrianism, which viewed the world as a battleground between forces of good and forces of evil, between light and darkness.»[20] One of these is hāššāṭān, a figure depicted in (among other places) the Book of Job.

Rabbinic Judaism[edit]

According to Rabbinic Judaism, the angels have no bodies, but are eternally living creatures created out of fire. The Babylonian Talmud reads as «The Torah was not given to ministering angels.» (לא נתנה תורה למלאכי השרת) usually understood as a concession to human’s imperfection, in contrast to the angels.[24] Thus, they occasionally appear in Midrashim as competition with humans.[25] The angels as heavenly beings, strictly following the laws of God, become jealous of God’s affection for man. Humans, by following the Torah, in prayer, by resisting evil instincts (yetzer hara) and by teshuva, are preferred to the flawless angels. As a result, they are also inferior to humans in the Jewish tradition. In the Midrash, the plural of El (Elohim) used in Genesis in relation to the creation of human beings is explained by the presence of angels: God therefore consulted with the angels, but made the final decision alone. This story serves as an example, teaching that the powerful should also consult with the weak. God’s own final decision highlights God’s undisputable omnipotence.[25]

In post-Biblical Judaism,[clarification needed] certain angels took on particular significance and developed unique personalities and roles. Although these archangels were believed to rank among the heavenly host, no systematic hierarchy ever developed. Metatron is considered one of the highest of the angels in Merkabah and Kabbalah mysticism and often serves as a scribe; he is briefly mentioned in the Talmud[26] and figures prominently in Merkabah mystical texts. Michael, who serves as a warrior[27] and advocate for Israel (Daniel 10:13), is looked upon particularly fondly.[28] Gabriel is mentioned in the Book of Daniel (Daniel 8:15–17) and briefly in the Talmud,[29] as well as in many Merkabah mystical texts. There is no evidence in Judaism for the worship of angels, but there is evidence for the invocation and sometimes even conjuration of angels.[21]

Philo of Alexandria identifies the angel with the Logos inasmuch as the angel is the immaterial voice of God. The angel is something different from God himself, but is conceived as God’s instrument.[30]

Four classes of ministering angels minister and utter praise before the Holy One, blessed be He: the first camp (led by) Michael on His right, the second camp (led by) Gabriel on His left, the third camp (led by) Uriel before Him, and the fourth camp (led by) Raphael behind Him; and the Shekhinah of the Holy One, blessed be He, is in the centre. He is sitting on a throne high and exalted[31]

Later interpretations[edit]

According to Kabbalah, there are four worlds and our world is the last world: the world of action (Assiyah). Angels exist in the worlds above as a ‘task’ of God. They are an extension of God to produce effects in this world. After an angel has completed its task, it ceases to exist. The angel is in effect the task. This is derived from the book of Genesis when Abraham meets with three angels and Lot meets with two. The task of one of the angels was to inform Sara and Abraham of their coming child. The other two were to save Lot and to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah.[21]

Jewish philosopher Maimonides explained his view of angels in his Guide for the Perplexed II:4 and II

… This leads Aristotle in turn to the demonstrated fact that God, glory and majesty to Him, does not do things by direct contact. God burns things by means of fire; fire is moved by the motion of the sphere; the sphere is moved by means of a disembodied intellect, these intellects being the ‘angels which are near to Him’, through whose mediation the spheres move … thus totally disembodied minds exist which emanate from God and are the intermediaries between God and all the bodies [objects] here in this world.

— Guide for the Perplexed II:4, Maimonides

Maimonides had a neo-Aristotelian interpretation of the Bible. Maimonides writes that to the wise man, one sees that what the Bible and Talmud refer to as «angels» are actually allusions to the various laws of nature; they are the principles by which the physical universe operates.

For all forces are angels! How blind, how perniciously blind are the naive?! If you told someone who purports to be a sage of Israel that the Deity sends an angel who enters a woman’s womb and there forms an embryo, he would think this a miracle and accept it as a mark of the majesty and power of the Deity, despite the fact that he believes an angel to be a body of fire one third the size of the entire world. All this, he thinks, is possible for God. But if you tell him that God placed in the sperm the power of forming and demarcating these organs, and that this is the angel, or that all forms are produced by the Active Intellect; that here is the angel, the «vice-regent of the world» constantly mentioned by the sages, then he will recoil.– Guide for the Perplexed II:4

One of Melozzo’s musician (seraphim) angels from the Basilica dei Santi Apostoli, now in the sacristy of St. Peter’s Basilica

Angel of the Revelation by William Blake, created between c. 1803 and c. 1805

Individuals[edit]

From the Jewish Encyclopedia, entry «Angelology».[21]

- Michael (archangel) (translation: who is like God?), kindness of God, and stands up for the children of mankind

- Gabriel (archangel) (translation: God is my strength), performs acts of justice and power

(Only these two angels are mentioned by name in the Hebrew Bible; the rest are from extra-biblical tradition.)

- Jophiel (translation: Beauty of God), expelled Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden holding a flaming sword and punishes those who transgress against God

- Metatron, heavenly scribe of God

- Raphael (archangel) (translation: It is God who heals), God’s healing force

- Uriel (archangel) (translation: God is my light), leads humanity to destiny

- Samael (archangel) (translation: Venom of God), angel of death—see also Malach HaMavet (translation: the angel of death)

- Sandalphon (archangel) (translation: bringing together), battles Samael and brings mankind together

Christianity[edit]

The Divine Comedy, Paradise (Paradiso), illustration by Gustave Doré

The Divine Comedy, Paradise, illustration by Gustave Doré

The Divine Comedy, Paradise, illustration by Gustave Doré

Christians inherited Jewish understandings of angels, which in turn may have been partly inherited from the Egyptians.[32] In the early stage, the Christian concept of an angel characterized the angel as a messenger of God. Later came identification of individual angelic messengers: Gabriel, Michael, Raphael, and Uriel.[33] Then, in the space of little more than two centuries (from the 3rd to the 5th) the image of angels took on definite characteristics both in theology and in art.[34] Ellen Muehlberger has argued that in late antiquity, angels were conceived of as one type of being among many, whose primary purpose was to guard and to guide Christians.[35]

Christian Bible[edit]

Angels are represented throughout Christian Bibles as spiritual beings intermediate between God and humans: «Yet you have made them [humans] a little lower than God, and crowned them with glory and honor.» (Psalms 8:4–5). Christians believe that angels are created beings, based on (Psalms 148:2–5; Colossians 1:16). Greek translations of the Hebrew Bible refer to intermediary beings, as angels, instead of daimons, thus giving raise to a distinction between demons and angels.[citation needed] In the Old Testament, both benevolent and fierce angels are mentioned, but never called demons. The symmetry lies between angels sent by God, and intermediary spirits of foreign deities, not in good and evil deeds.[36]

In the New Testament, the existence of angels, just like that of demons, is taken for granted.[37] They can intervene and intercede on behalf of humans. Angels protect the righteous (Matthew 4:6, Luke 4:11). They dwell in the heavens (Matthew 28:2, John 1:51), act as God’s warriors (Matthew 26:53) and worship God (Luke 2:13).[38] In the parable of the Rich man and Lazarus, angels behave as psychopomps. The Resurrection of Jesus features angels, telling the woman that Jesus is no longer in the tomb, but has risen from the dead.[39]

Interaction with humans[edit]

Forget not to show love unto strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.—Hebrews 13:2

Three separate cases of angelic interaction deal with the births of John the Baptist and Jesus. In Luke 1:11, an angel appears to Zechariah to inform him that he will have a child despite his old age, thus proclaiming the birth of John the Baptist. In Luke 1:26 Gabriel visits Mary in the Annunciation to foretell the birth of Jesus. Angels proclaim the birth of Jesus in the Adoration of the shepherds in Luke 2:10.[40]

According to Matthew 4:11, after Jesus spent 40 days in the desert, «…the Devil left him and, behold, angels came and ministered to him.» In Luke 22:43 an angel comforts Jesus during the Agony in the Garden.[41] In Matthew 28:5 an angel speaks at the empty tomb, following the Resurrection of Jesus and the rolling back of the stone by angels.[40]

In 1851 Pope Pius IX approved the Chaplet of Saint Michael based on the 1751 reported private revelation from archangel Michael to the Carmelite nun Antonia d’Astonac.[42] In a biography of Gemma Galgani written by Germanus Ruoppolo, Galgani stated that she had spoken with her guardian angel.

Pope John Paul II emphasized the role of angels in Catholic teachings in his 1986 address titled «Angels Participate In History Of Salvation», in which he suggested that modern mentality should come to see the importance of angels.[43]

According to the Vatican’s Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, «The practice of assigning names to the Holy Angels should be discouraged, except in the cases of Gabriel, Raphael and Michael whose names are contained in Holy Scripture.»[44]

Theology[edit]

According to Augustine of Hippo, «‘Angel’ is the name of their office, not of their nature. If you seek the name of their nature, it is ‘spirit’; if you seek the name of their office, it is ‘angel’: from what they are, ‘spirit’, from what they do, ‘angel’.»[45] Gregory of Nazianzus thought that angels were made as «spirits» and «flames of fire», following Hebrews 1, and that they can be identified with the «thrones, dominions, rulers and authorities» of Colossians 1.[35]

By the late 4th century, the Church Fathers agreed that there were different categories of angels, with appropriate missions and activities assigned to them. There was, however, some disagreement regarding the nature of angels. Some argued that angels had physical bodies,[46] while some maintained that they were entirely spiritual. Some theologians had proposed that angels were not divine but on the level of immaterial beings subordinate to the Trinity. The resolution of this Trinitarian dispute included the development of doctrine about angels.[47]

Forty Gospel Homilies by Pope Gregory I (c. 540 – 12 March 604) noted angels and archangels.[48] The Fourth Lateran Council’s (1215) Firmiter credimus decree (issued against the Albigenses) declared that the angels were created beings and that men were created after them. The First Vatican Council (1869) repeated this declaration in Dei Filius, the «Dogmatic constitution on the Catholic faith».

Thomas Aquinas (13th century) relates angels to Aristotle’s metaphysics in his Summa contra Gentiles,[49] Summa Theologica,[50] and in De substantiis separatis,[51] a treatise on angelology. Although angels have greater knowledge than men, they are not omniscient, as Matthew 24:36 points out.[52] According to the Summa Theologica, angels were created instantaneously by God in a state of grace in the Empyrean Heaven (LXI. 4) at the same time when he created all the contents of the corporeal world (LXI. 3). They are pure spirits whose life consists in knowledge and love. Being bodiless, their knowledge is intellectual and not through senses (LIV. 5). Differently from humans, their knowledge is not acquired from the exterior world; moreover they attain to the truth of a thing at a single glance without need of reasoning (LV. a; LVIII. 3,4). They know all that passes in the external world (LV. 2) and the totality of creatures, but they don’t know human secret thoughts that depends on human free will and thereby are not necessarily linked up with external events (LVII. 4). They don’t know also the future unless God reveals it to them (LVII. 3).[53]

According to Aquinas, angels are the closest creatures to God. Therefore, like God, they are constituted by pure form without matter.[54] Each angel is a species which a unique individual belongs to; angels differ one from another by way of their unique and irrepetible form. In other words, form -and not matter- is their principle of individuation.[55]

The New Church (Swedenborgianism)[edit]

The New Church denominations that arose from the writings of theologian Emanuel Swedenborg have distinct ideas about angels and the spiritual world in which they dwell. Adherents believe that all angels are in human form with a spiritual body, and are not just minds without form.[56] There are different orders of angels according to the three heavens,[57] and each angel dwells in one of innumerable societies of angels. Such a society of angels can appear as one angel as a whole.[58]

All angels originate from the human race, and there is not one angel in heaven who first did not live in a material body.[59] Moreover, all children who die not only enter heaven but eventually become angels.[60] The life of angels is that of usefulness, and their functions are so many that they cannot be enumerated. However each angel will enter a service according to the use that they had performed in their earthly life.[61] Names of angels, such as Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, signify a particular angelic function rather than an individual being.[62]

While living in one’s body an individual has conjunction with heaven through the angels,[63] and with each person, there are at least two evil spirits and two angels.[64] Temptation or pains of conscience originates from a conflict between evil spirits and angels.[65] Due to man’s sinful nature it is dangerous to have open direct communication with angels[66] and they can only be seen when one’s spiritual sight has been opened.[67] Thus from moment to moment angels attempt to lead each person to what is good tacitly using the person’s own thoughts.[68]

Latter Day Saints[edit]

The Latter Day Saint movement views angels as the messengers of God. They are sent to mankind to deliver messages, minister to humanity, teach doctrines of salvation, call mankind to repentance, give priesthood keys, save individuals in perilous times, and guide humankind.[69]

Latter Day Saints believe that angels either are the spirits of humans who are deceased or who have yet to be born, or are humans who have been resurrected or translated and have physical bodies of flesh and bones.[70] Joseph Smith taught that «there are no angels who minister to this earth but those that do belong or have belonged to it.»[71] As such, Latter Day Saints also believe that Adam, the first man, was and is now the archangel Michael,[72][73][74] and that Gabriel lived on the earth as Noah.[70] Likewise the Angel Moroni first lived in a pre-Columbian American civilization as the 5th-century prophet-warrior named Moroni.

Smith described his first angelic encounter in the following manner:

While I was thus in the act of calling upon God, I discovered a light appearing in my room, which continued to increase until the room was lighter than at noonday, when immediately a personage appeared at my bedside, standing in the air, for his feet did not touch the floor.

He had on a loose robe of most exquisite whiteness. It was a whiteness beyond anything earthly I had ever seen; nor do I believe that any earthly thing could be made to appear so exceedingly white and brilliant …

Not only was his robe exceedingly white, but his whole person was glorious beyond description, and his countenance truly like lightning. The room was exceedingly light, but not so very bright as immediately around his person. When I first looked upon him, I was afraid; but the fear soon left me.[75]

Most angelic visitations in the early Latter Day Saint movement were witnessed by Smith and Oliver Cowdery, who both said (prior to the establishment of the church in 1830) they had been visited by the prophet Moroni, John the Baptist, and the apostles Peter, James, and John. Later, after the dedication of the Kirtland Temple, Smith and Cowdery said they had been visited by Jesus, and subsequently by Moses, Elias, and Elijah.[76]

Others who said they received a visit by an angel include the other two of the Three Witnesses: David Whitmer and Martin Harris. Many other Latter Day Saints, both in the early and modern church, have said they had seen angels, although Smith posited that, except in extenuating circumstances such as the restoration, mortals teach mortals, spirits teach spirits, and resurrected beings teach other resurrected beings.[77]

Islam[edit]

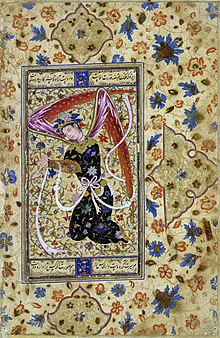

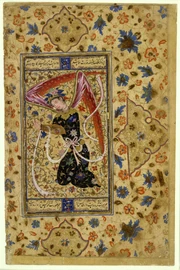

Depiction of an angel in a Persian miniature (Iran, 1555)

Belief in angels is fundamental to Islam. The Quranic word for angel (Arabic: ملاك Malāk) derives either from Malaka, meaning «he controlled», due to their power to govern different affairs assigned to them,[78] or from the root either from ʼ-l-k, l-ʼ-k or m-l-k with the broad meaning of a «messenger», just like its counterparts in Hebrew (malʾákh) and Greek (angelos). Unlike their Hebrew counterpart, the term is exclusively used for heavenly spirits of the divine world, but not for human messengers. The Quran refers to both angelic and human messengers as «rasul» instead.[79] Contrary to popular belief, angels are never described as agents of revelation in the Quran, although interpretation credits Gabriel with that.[80]

The Quran is the principal source for the Islamic concept of angels.[81] Some of them, such as Gabriel and Michael, are mentioned by name in the Quran, others are only referred to by their function. In hadith literature, angels are often assigned to only one specific phenomenon.[82] Angels play a significant role in Mi’raj literature, where Muhammad encounters several angels during his journey through the heavens.[83] Further angels have often been featured in Islamic eschatology, Islamic theology and Islamic philosophy.[84] Duties assigned to angels include, for example, communicating revelations from God, glorifying God, recording every person’s actions, and taking a person’s soul at the time of death.

In Islam, just like in Judaism and Christianity, angels are often represented in anthropomorphic forms combined with supernatural images, such as wings, being of great size or wearing heavenly articles.[85] The Quran describes them as «messengers with wings—two, or three, or four: He [God] adds to Creation as He pleases…»[86] Common characteristics for angels are their missing needs for bodily desires, such as eating and drinking.[87] Their lack of affinity to material desires is also expressed by their creation from light: Angels of mercy are created from nur (cold light) in opposition to the angels of punishment created from nar (hot light).[88] Muslims do not generally share the perceptions of angelic pictorial depictions, such as those found in Western art.

Although believing in angels remain one of Six Articles of Faith in Islam, one can not find a dogmatic angelology in Islamic tradition. Despite this, scholars had discussed the role of angels from specific canonical events, such as the Mi’raj, and Quranic verses. Even if they are not in focus, they have been featured in folklore, philosophy debates and systematic theology. While in classical Islam, widespread notions were accepted as canonical, there is a tendency in contemporary scholarship to reject much material about angels, like calling the Angel of Death by the name Azra’il.[89]

In Folk Islam, individual angels may be evoked in exorcism rites, whose names are engraved in talismans or amulets.[90]

Some modern scholars have emphasized a metaphorical reinterpretation of the concept of angels.[91]

Baháʼí faith[edit]

In his Kitáb-i-Íqán Baháʼu’lláh, founder of the Baháʼí Faith, describes angels as people who «have consumed, with the fire of the love of God, all human traits and limitations», and have «clothed themselves» with angelic attributes and have become «endowed with the attributes of the spiritual». ʻAbdu’l-Bahá describes angels as the «confirmations of God and His celestial powers» and as «blessed beings who have severed all ties with this nether world» and «been released from the chains of self», and «revealers of God’s abounding grace». The Baháʼí writings also refer to the Concourse on High, an angelic host, and the Maid of Heaven of Baháʼu’lláh’s vision.[92]

I raised my hand another time, and bared one of Her breasts that had been hidden beneath Her gown. Then the firmament was illumined by the radiance of its light, contingent beings were made resplendent by its appearance and effulgence, and by its rays, infinite numbers of suns dawned forth, as though they trekked through heavens that were without beginning or end. I became bewildered at the pen of God’s handiwork, and at what it had inscribed upon Her temple. It was as though She had appeared with a body of light in the forms of the spirit, as though She moved upon the earth of essence in the substance of manifestation. I noticed that the houris had poked their heads out of their rooms and were suspended in the air above Her. They grew perplexed at Her appearance and Her beauty and were entranced by the raptures of Her song. Praise be to Her creator, fashioner, and maker—to the one Who made Her manifest.

Then she nearly swooned within herself, and with all her being she sought to inhale My fragrance. She opened Her lips, and the rays of light dawned forth from Her teeth, as though the pearls of the cause had appeared from Her treasures and Her shells.

She asked, «Who art Thou?»

I said, «A servant of God and the son of his maidservant.»[93]

Neoplatonism[edit]

Philo of Alexandria already identified the Neo-Platonic interpretation of daemons as angels. The daemons were thought to be intermediary between the supernatural and earthly realm, interpreted by Philo as the Greek term for angels.[36]

In the commentaries of Proclus (4th century) on the Timaeus of Plato, Proclus uses the terminology of «angelic» (aggelikos) and «angel» (aggelos) in relation to metaphysical beings. According to Aristotle, just as there is a Prime Mover,[94] so, too, must there be spiritual secondary movers.[95]

Ibn Sina, who drew upon the Neo-Platonistic emanation cosmology of Al-Farabi, developed an angelological hierarchy of Intellects, which are created by «the One». Therefore, the first creation by God was the supreme archangel followed by other archangels, who are identified with lower Intellects. From these Intellects again, emanated lower angels or «moving spheres», from which in turn, emanated other Intellects until it reaches the Intellect, which reigns over the souls. The tenth Intellect is responsible for bringing material forms into being and illuminating the minds.[96][97]

Sikhism[edit]

The poetry of the holy scripture of the Sikhs – the Sri Guru Granth Sahib – figuratively mentions a messenger or angel of death, sometimes as Yama (ਜਮ – «Yam») and sometimes as Azrael (ਅਜਰਾਈਲੁ – «Ajraeel»):

ਜਮ ਜੰਦਾਰੁ ਨ ਲਗਈ ਇਉ ਭਉਜਲੁ ਤਰੈ ਤਰਾਸਿ

The Messenger of Death will not touch you; in this way, you shall cross over the terrifying world ocean [ru], carrying others across with you.— Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Siree Raag, First Mehl, p. 22.[98]

ਅਜਰਾਈਲੁ ਯਾਰੁ ਬੰਦੇ ਜਿਸੁ ਤੇਰਾ ਆਧਾਰੁ

Azraa-eel, the Messenger of Death, is the friend of the human being who has Your support, Lord.— Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Tilang, Fifth Mehl, Third House, p. 724.[99]

In a similar vein, the Sri Guru Granth Sahib talks of a figurative Chitar (ਚਿਤ੍ਰ) and Gupat (ਗੁਪਤੁ):

ਚਿਤ੍ਰ ਗੁਪਤੁ ਸਭ ਲਿਖਤੇ ਲੇਖਾ ॥

ਭਗਤ ਜਨਾ ਕਉ ਦ੍ਰਿਸਟਿ ਨ ਪੇਖਾ

Chitar and Gupat, the recording angels of the conscious and the unconscious, write the accounts of all mortal beings, / but they cannot even see the Lord’s humble devotees.

— Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Aasaa, Fifth Mehl, Panch-Pada, p. 393.[100]

However, Sikhism has never had a literal system of angels, preferring guidance without explicit appeal to supernatural orders or beings.[citation needed]

Esotericism[edit]

Hermetic Qabalah[edit]

According to the Kabbalah as described by the Golden Dawn there are ten archangels, each commanding one of the choirs of angels and corresponding to one of the Sephirot. It is similar to the Jewish angelic hierarchy.

| Rank | Choir of Angels | Translation | Archangel | Sephirah |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hayot Ha Kodesh | Holy Living Ones | Metatron | Keter |

| 2 | Ophanim | Wheels | Raziel | Chokmah |

| 3 | Erelim | Brave ones[101] | Tzaphkiel | Binah |

| 4 | Hashmallim | Glowing ones, Amber ones[102] | Tzadkiel | Chesed |

| 5 | Seraphim | Burning Ones | Khamael | Gevurah |

| 6 | Malakim | Messengers, angels | Raphael | Tipheret |

| 7 | Elohim | Godly Beings | Uriel | Netzach |

| 8 | Bene Elohim | Sons of Elohim | Michael | Hod |

| 9 | Cherubim | [103] | Gabriel | Yesod |

| 10 | Ishim | Men (man-like beings, phonetically similar to «fires») | Sandalphon | Malkuth |

Wheel of the 72 angels of God that exist throughout the course of a year. Here, the squares are meaningless and were only added for aesthetic value.

Theosophy[edit]

In the teachings of the Theosophical Society, Devas are regarded as living either in the atmospheres of the planets of the Solar System (Planetary Angels) or inside the Sun (Solar Angels) and they help to guide the operation of the processes of nature such as the process of evolution and the growth of plants; their appearance is reputedly like colored flames about the size of a human. It is believed by Theosophists that devas can be observed when the third eye is activated. Some (but not most) devas originally incarnated as human beings.[104]

It is believed by Theosophists that nature spirits, elementals (gnomes, undines, sylphs, and salamanders), and fairies also can be observed when the third eye is activated.[105] It is maintained by Theosophists that these less evolutionarily developed beings have never been previously incarnated as humans; they are regarded as being on a separate line of spiritual evolution called the «deva evolution»; eventually, as their souls advance as they reincarnate, it is believed they will incarnate as devas.[106]

It is asserted by Theosophists that all of the above-mentioned beings possess etheric bodies that are composed of etheric matter, a type of matter finer and more pure that is composed of smaller particles than ordinary physical plane matter.[106]

Other[edit]

The Greek magical papyri, a set of texts forming into a completed grimoire that date somewhere between 100 BC and 400 AD, also list the names of the angels found in monotheistic religions, but they are presented as deities.[107]

Numerous references to angels present themselves in the Nag Hammadi Library, in which they both appear as malevolent servants of the Demiurge and innocent associates of the aeons.[108]

Brahma Kumaris[edit]

The Brahma Kumaris uses the term «angel» to refer to a perfect, or complete state of the human being, which they believe can be attained through a connection with God.[109][110] It is expanded as a state of being rather than an entity.[109]

Yazidism[edit]

In Yazidism, there are seven Divine Beings (often called ‘angels’ in the literature) who were created by God prior to the creation of this world. God appointed Tawûsî Melek as their leader and assigned all of the world’s affairs to these seven Divine Beings.[111] These Divine Beings are referred to as Tawûsî Melek, Melek Şemsedîn, Melek Nasirdîn, Melek Fexredîn, Melek Sicadîn, Melek Şêxsin and Melek Şêxûbekir.

In art[edit]

Two Baroque angels from southern Germany, from the mid-18th century, made of lindenwood, gilded and with original polychromy, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

According to mainstream Christian theology, angels are wholly spiritual beings and therefore do not eat, excrete or have sex, and have no gender. Although their different roles, such as warriors for some archangels, may suggest a human gender, Christian artists were careful not to given them specific gender attributes, at least until the 19th century, when some acquire breasts for example.[112]

In an address during a General Audience of 6 August 1986, entitled «Angels participate in the history of salvation», Pope John Paul II explained that «[T]he angels have no ‘body’ (even if, in particular circumstances, they reveal themselves under visible forms because of their mission for the good of people).»[43] Christian art perhaps reflects the descriptions in Revelation 4:6–8 of the Four Living Creatures (Greek: τὰ τέσσαρα ζῷα) and the descriptions in the Hebrew Bible of cherubim and seraphim (the chayot in Ezekiel’s Merkabah vision and the Seraphim of Isaiah). However, while cherubim and seraphim have wings in the Bible, no angel is mentioned as having wings.[113]

The earliest known Christian image of an angel—in the Cubicolo dell’Annunziazione in the Catacomb of Priscilla (mid-3rd century)—is without wings. In that same period, representations of angels on sarcophagi, lamps and reliquaries also show them without wings,[114] as for example the angel in the Sacrifice of Isaac scene in the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus (although the side view of the Sarcophagus shows winged angelic figures).

16th century stone statue depicting the Angel of Portugal, at the Machado de Castro National Museum, in Portugal.

The earliest known representation of angels with wings is on the «Prince’s Sarcophagus», attributed to the time of Theodosius I (379–395), discovered at Sarigüzel, near Istanbul, in the 1930s.[115] From that period on, Christian art has represented angels mostly with wings, as in the cycle of mosaics in the Basilica of Saint Mary Major (432–440).[116] Four- and six-winged angels, drawn from the higher grades of angels (especially cherubim and seraphim) and often showing only their faces and wings, are derived from Persian art and are usually shown only in heavenly contexts, as opposed to performing tasks on earth. They often appear in the pendentives of church domes or semi-domes. Prior to the Judeo-Christian tradition, in the Greek world the goddess Nike and the gods Eros and Thanatos were also depicted in human-like form with wings.

John Chrysostom explained the significance of angels’ wings:

They manifest a nature’s sublimity. That is why Gabriel is represented with wings. Not that angels have wings, but that you may know that they leave the heights and the most elevated dwelling to approach human nature. Accordingly, the wings attributed to these powers have no other meaning than to indicate the sublimity of their nature.[117]

Angels are typically depicted in Mormon art as having no wings based on a quote from Joseph Smith («An angel of God never has wings»).[118]

In terms of their clothing, angels, especially the Archangel Michael, were depicted as military-style agents of God and came to be shown wearing Late Antique military uniform. This uniform could be the normal military dress, with a tunic to about the knees, an armour breastplate and pteruges, but was often the specific dress of the bodyguard of the Byzantine Emperor, with a long tunic and the loros, the long gold and jewelled pallium restricted to the Imperial family and their closest guards.

The basic military dress was shown in Western art into the Baroque period and beyond (see Reni picture above), and up to the present day in Eastern Orthodox icons. Other angels came to be conventionally depicted in long robes, and in the later Middle Ages they often wear the vestments of a deacon, a cope over a dalmatic. This costume was used especially for Gabriel in Annunciation scenes—for example the Annunciation in Washington by Jan van Eyck.

Some types of angels are described as possessing more unusual or frightening attributes, such as the fiery bodies of the Seraphim, and the wheel-like structures of the Ophanim.

-

Italian Gothic adorning angel, circa 1395–1396, lunense marble from Carrara (Italy), overall: 118.7 x 28.6 x 32.4 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Italian Gothic angel of the annunciation, circa 1430–1440, Istrian limestone, gesso and gilt, 95.3 x 37.5 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Southern German Baroque angel, by Ignaz Günther, circa 1760–1770, lindenwood with traces of gesso, 26.7 x 18.4 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Corinthian capital with an angel who wolds a festoon with his wings, in Stiftskirche Mariae Himmelfahrt in Schlägl (Austria)

-

An angel in the former coat of arms of Tenala

-

The Kind Angel of Peace monument (Donetsk, Ukraine)

-

Angel in Sao Paulo.

See also[edit]

- Angel (Buffy the Vampire Slayer)

- Angel Beats!

- Angel of the North

- Angels in art

- Apsara

- Chalkydri

- George Clayton

- Classification of demons

- Cupid and Erotes

- Dakini

- Demigod

- Elioud

- Eudaemon (mythology)

- Exorcism

- Gandharva

- Ghost

- Genius (mythology)

- Holy Spirit

- Hierarchy of angels

- In paradisum

- List of angels in theology

- List of films about angels

- Non-physical entity

- Substance theory

- Uthra

- Watcher (angel)

- Yaksha

References[edit]

- ^ The Free Dictionary: «angel», retrieved 1 September 2012

- ^ «Angels in Christianity». Religion Facts. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015.

- ^ Augustine of Hippo’s Enarrationes in Psalmos, 103, I, 15, augustinus.it (in Latin)

- ^ Blau, Ludwig; Kohler, Kaufmann. «Angelology». Jewish Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ Proverbio (2007), pp. 90–95; compare review in La Civiltà Cattolica, 3795–3796 (2–16 August 2008), pp. 327–328.

- ^

Didron, Vol 2, pp.68–71. - ^ «angel – Definition of angel in English by Oxford Dictionaries». Oxford Dictionaries – English. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013.

- ^ Strong, James. «Strong’s Greek». Biblehub.com. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

Transliteration: aggelos Phonetic Spelling: (ang’-el-os)

- ^ palaeolexicon.com, a-ke-ro, Palaeolexicon.

- ^ Beekes, R. S. P., Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 9.

- ^ Kosior, Wojciech (June 2013). «The Angel in the Hebrew Bible from the Statistic and Hermeneutic Perspectives. Some Remarks on the Interpolation Theory». The Polish Journal of Biblical Research. 12 (1 (23)): 55–70. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ Lewis, James R., Oliver, Evelyn Dorothy, Sisung Kelle S. (Editor) (1996), Angels A to Z, Entry: Zoroastrianism, pp. 425–427, Visible Ink Press, ISBN 0-7876-0652-9

- ^ Darmesteter, James (1880)(translator), The Zend Avesta, Part I: Sacred Books of the East, Vol. 4, pp. lx–lxxii, Oxford University Press, 1880, at sacred-texts.com

- ^ Hermann Röttger: Mal’ak jhwh, Bote von Gott. Die Vorstellung von Gottesboten im hebräischen Alten Testament. Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1978, ISBN 3-261-02633-2 (zugl. Dissertation, Universität Regensburg 1977).

Johann Michl: Engel (jüd.). In: RAC, Band 5. Hiersemann Verlag, Stuttgart 1962, p. 60–97. (German) - ^ Joseph Hertz: Kommentar zum Pentateuch, hier zu Gen 19,17 EU. Morascha Verlag Zürich, 1984. Band I, p. 164. (German)

- ^ a b ««מַלְאָךְ,» Francis Brown, S.R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs, eds.: A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament, p. 521″. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Pope, Hugh. «Angels.» The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. accessed 20 October 2010

- ^ Frederick Copleston, A History of Philosophy, Volume 1, Continuum, 2003, p. 460.

- ^ Baker, Louis Goldberg. Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology: Angel of the Lord «The functions of the angel of the Lord in the Old Testament prefigure the reconciling ministry of Jesus. In the New Testament, there is no mention of the angel of the Lord; the Messiah himself is this person.»

- ^ a b c d Coogan, Michael D. (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c d «Angelology». The Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Dunn, James D. G. (15 July 2010). Did the First Christians Worship Jesus?: The New Testament Evidence. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-61164-070-0.

God sends an angel to communicate with prophets, and an interpreter angel appears regularly in apocalyptic visions and as companion in heavenly journeys. One of the most fascinating features of several ancient stories is the appearance of what can be called theophanic angels; that is, angels who not only bring a message from God, but who represent God in personal terms, or who even may be said to embody God.

- ^ Chilton, Bruce D. (2002). «(The) Son of (The) Man, and Jesus». In Craig A. Evans (ed.). Authenticating the Words of Jesus. BRILL. p. 276. ISBN 0-391-04163-0.

As described in the book of Daniel, «one like a son of man» is clearly identified as the messianic and angelic redeemer of Israel, a truly heavenly redeemer known to Israel as the archangel Michael.

- ^ Hayes, Christine. «“The Torah was not Given to Ministering Angels”: Rabbinic Aspirationalism.» Talmudic Transgressions. Brill, 2017. 123-160.

- ^ a b Reinhard Gregor Kratz, Hermann Spieckermann: Götterbilder, Gottesbilder, Weltbilder: Griechenland und Rom, Judentum, Christentum und Islam. Mohr Siebeck, 2006, ISBN 978-3-16-148807-8 (German)

- ^ Sanhedrin 38b and Avodah Zerah 3b.

- ^ Aleksander R. Michalak, Angels as Warriors in Late Second Temple Jewish Literature, Tuebingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2012.

- ^ Hannah Darrell D., Michael and Christ: Michael Traditions and Angel Christology in Early Christianity, Tuebingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1999

- ^ cf. Sanhedrin 95b

- ^ Copleston, Frederick Charles (2003). A history of philosophy, Volume 1. Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 460. ISBN 0-8264-6895-0

- ^ Friedlander, Gerald. Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer Varda Books

- ^ Margaretha, Evans, Annette Henrietta (1 March 2007). The development of Jewish ideas of angels : Egyptian and Hellenistic connections, ca. 600 BCE to ca. 200 CE (Thesis).

- ^ Barker, Margaret (2004). An Extraordinary Gathering of Angels, M Q Publications.

- ^ «LA FIGURA DELL’ANGELO NELLA CIVILTA’ PALEOCRISTIANA – PROVERBIO CECILIA – TAU – Libro». 27 December 2008. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ a b Muehlberger, Ellen (2013). Angels in late ancient Christianity. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-993193-4. OCLC 806291246.

- ^ a b Martin, Dale Basil (2010). «When Did Angels Become Demons?». Journal of Biblical Literature. 129 (4): 657–677. doi:10.2307/25765960. JSTOR 25765960.

- ^ Loren T. Stuckenbruck; Gabriele Boccaccini (2016). Enoch and the Synoptic Gospels: Reminiscences, Allusions, Intertextuality. SBL Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-884-14118-1.

- ^ Loren T. Stuckenbruck; Gabriele Boccaccini (2016). Enoch and the Synoptic Gospels: Reminiscences, Allusions, Intertextuality. SBL Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-0-884-14118-1.

- ^ Loren T. Stuckenbruck; Gabriele Boccaccini (2016). Enoch and the Synoptic Gospels: Reminiscences, Allusions, Intertextuality. SBL Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-884-14118-1.

- ^ a b «CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Angels». www.newadvent.org.

- ^ «BibleGateway, Luke 22:43». Biblegateway.com. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 0-87973-910-X page 123

- ^ a b «Angels Participate In History Of Salvation». Vatican.va. 6 August 1986. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ «Directory on popular piety and the liturgy. Principles and guidelines». www.vatican.va.

- ^ Augustine, En. in Ps. 103, 1, 15: PL 37, 1348

- ^ Ludlow, Morwenna (2012). Brakke, David (ed.). «Demons, Evil, and Liminality in Cappadocian Theology» (PDF). Journal of Early Christian Studies. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 20 (2): 179–211 [183]. doi:10.1353/earl.2012.0014. hdl:10871/15370. ISSN 1067-6341. S2CID 145816767. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ Proverbio (2007), pp. 29–38; cf. summary in Libreria Hoepli and review in La Civiltà Cattolica, 3795–3796 (2–16 August 2008), pp. 327–328.

- ^ Pope Gregory I; David Hurst (OSB.) (1990). «Homily 34». Forty Gospel Homilies. Cistercian Publications. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-87907-623-8.

You should be aware that the word «angel» denotes a function rather than a nature. Those holy spirits of heaven have indeed always been spirits. They can only be called angels when they deliver some message. Moreover, those who deliver messages of lesser importance are called angels; and those who proclaim messages of supreme importance are called archangels. And so it was that not merely an angel but the archangel Gabriel was sent to the Virgin Mary.

- ^ Thomas Aquinas. «46». Summa contra Gentiles. Vol. 2. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ Thomas Aquinas. Summa Theologica. Treatise on Angels. Newadvent.org.

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas. De substantiis separatis. Josephkenny.joyeurs.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2010.

- ^ «BibleGateway, Matthew 24:36». Biblegateway.com. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Pegues, O.P., R.P. Thomas (1922). Cathechism of the «Summa Theologica» of Saint Thomas Aquinas for the Use of the Faithful. Translated by Whitacre, O.P., Aelred. Leipzig: St Athanasius Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 9781721695478.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Edward Feser (2009). Aquinas A Beginner’s Guide. p. 35. ISBN 9781780740065.

An angel, says Aquinas, is a form without matter, and thus its essence corresponds to its form alone (DEE 4). … Does this mean that an angel, as a pure form, is also pure actuality, devoid of potency? By no means.

- ^ Edouard Hugon (2013). Cosmology Translated, with Notes by Francisco J. Romero Carrasquillo. Editiones Scholasticae. p. 196. ISBN 9783868385311. Quote: «Another requirement is that there be a principle of individuation. But certain beings, namely angels, lack a principle of individuation, which is signate matter. Hence, the angelic form, even though it is communicable in itself as species, is not in fact communicated, because there are no numerically distinct subjects that can receive it.»

- ^ Swedenborg, Emanuel. Heaven and Hell, 1758. Rotch Edition (revised). New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1907, in The Divine Revelation of the New Jerusalem (2012), n. 74.

- ^ Arcana Coelestia, n. 459.

- ^ Heaven and Hell, n. 51–53.

- ^ Heaven and Hell, n. 311

- ^ Heaven and Hell, n. 416

- ^ Heaven and Hell, n. 387–393.

- ^ Swedenborg, Emanuel. Heavenly Arcana (or Arcana Coelestia), 1749–58 (AC). Rotch Edition (revised). New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1907, in The Divine Revelation of the New Jerusalem (2012), n. 8192.3.

- ^ Heaven and Hell, n. 291–298.

- ^ Arcana Coelestia, n. 50, 697, 968.

- ^ Arcana Coelestia, n. 227.

- ^ Arcana Coelestia, n. 784.2.

- ^ Heaven and Hell, n. 76.

- ^ Arcana Coelestia, n. 5992.3.

- ^ «God’s messengers, those individuals whom he sends (often from his personal presence in the eternal worlds), to deliver his messages (Luke 1:11–38); to minister to his children (Acts 10:1–8, Acts 10:30–32); to teach them the doctrines of salvation (Mosiah 3); to call them to repentance (Moro. 7:31); to give them priesthood and keys (D.&C. 13; 128:20–21); to save them in perilous circumstances (Nehemiah 3:29–31; Daniel 6:22); to guide them in the performance of his work (Genesis 24:7); to gather his elect in the last days (Matthew 24:31); to perform all needful things relative to his work (Moro. 7:29–33)—such messengers are called angels.».

- ^ a b «LDS Bible Dictionary-Angels». Scriptures.lds.org. 21 February 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Doctrine and Covenants 130:4–5.

- ^ The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints «Chapter 6: The Fall of Adam and Eve,» Gospel Principles (Salt Lake City, Utah: LDS Church, 2011) pp. 26–30.

- ^ «D&C 107:24». Scriptures.lds.org. 21 February 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Mark E. Petersen, «Adam, the Archangel», Ensign, November 1980.

- ^ «Joseph Smith–History 1:30–33». Scriptures.lds.org. 21 February 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ «D&C 110». Scriptures.lds.org. 21 February 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Robert J. Matthews, «The Fulness of Times», Ensign, December 1989.

- ^ Syed Anwer Ali Qurʼan, the Fundamental Law of Human Life: Surat ul-Faateha to Surat-ul-Baqarah (sections 1–21) Syed Publications 1984 University of Virginia

Digitalized 22. Okt. 2010 p. 121 - ^ S.R. Burge Journal of Qurʼanic Studies The Angels in Sūrat al-Malāʾika: Exegeses of Q. 35:1 Sep 2011. vol. 10, No. 1 : pp. 50–70

- ^ Welch, A.T., Paret, R. and Pearson, J.D., “al-Ḳurʾān”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E.

van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 05 May 2022 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0543>

First published online: 2012

First print edition: ISBN 9789004161214, 1960-2007 section 2 - ^ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti’s al-Haba’ik fi akhbar al-mala’ik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 p. 23

- ^ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti’s al-Haba’ik fi akhbar al-mala’ik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 p. 79

- ^ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti’s al-Haba’ik fi akhbar al-mala’ik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 p. 29

- ^ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti’s al-Haba’ik fi akhbar al-mala’ik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 p. 22

- ^ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti’s al-Haba’ik fi akhbar al-mala’ik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 pp. 97-99

- ^ Quran 35:1, Esposito (2002b, pp. 26–28), W. Madelung. «Malā’ika». Encyclopaedia of Islam Online., Gisela Webb. «Angel». Encyclopaedia of the Qurʼan Online.

- ^ Cenap Çakmak Islam: A Worldwide Encyclopedia [4 volumes] ABC-CLIO, 18.05.2017 ISBN 9781610692175 p. 140

- ^ Jane Dammen McAuliffe Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān Volume 3 Georgetown University, Washington DC p. 45

- ^ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti’s al-Haba’ik fi akhbar al-mala’ik 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 part 1.1 and 1.2.

- ^ Patrick Hughes, Thomas Patrick Hughes Dictionary of Islam Asian Educational Services 1995 ISBN 978-8-120-60672-2 page 73

- ^ Guessoum, Nidhal (2010). Islam’s Quantum Question: Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85773-075-6.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2000). «angels». A concise encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 38–39. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ^ «Tablet of the Maiden». bahai-library.com.

- ^ Aristotle. Metaphysics. 1072a ff.

- ^ Aristotle. Metaphysics. 1073a13 ff.

- ^ Abdullah Saeed Islamic Thought: An Introduction Routledge 2006 ISBN 9781134225651 p. 101

- ^ Mark Verman The Books of Contemplation: Medieval Jewish Mystical Sources SUNY Press 1992 ISBN 9780791407196 p. 129

- ^ «Sri Granth: Sri Guru Granth Sahib». srigranth.org. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ «Sri Granth: Sri Guru Granth Sahib». srigranth.org. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ «Sri Granth: Sri Guru Granth Sahib». srigranth.org. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ «Strong’s Hebrew: 691. אֶרְאֵל (erel) – perhaps a hero». biblesuite.com.

- ^ «Strong’s Hebrew: 2830. חַשְׁמַל (chashmal) – perhaps amber». biblesuite.com.

- ^ «Strong’s Hebrew: 3742. כְּרוּב (kerub) – probably an order of angelic beings». biblesuite.com.

- ^ Hodson, Geoffrey, Kingdom of the Gods ISBN 0-7661-8134-0—Has color pictures of what Devas supposedly look like when observed by the third eye—their appearance is reputedly like colored flames about the size of a human. Paintings of some of the devas claimed to have been seen by Hodson from his book Kingdom of the Gods:

- ^ «Eskild Tjalve’s paintings of devas, nature spirits, elementals and fairies». 21 November 2002. Archived from the original on 21 November 2002. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ a b Powell, A.E. The Solar System London:1930 The Theosophical Publishing House (A Complete Outline of the Theosophical Scheme of Evolution) See «Lifewave» chart (refer to index)

- ^ Betz, Hans (1996). The Greek Magical Papyri In Translation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226044477. Entries: «Introduction to the Greek Magical Papyri» and «PGM III. 1-164/fourth formula».

- ^ James M. Robinson (1988). The Nag Hammadi Library. Read online for free at the Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Basava Journal, Volume 19. Basava Samiti, 1994 (Bangalore, India).

- ^ Peace & purity: the story of the Brahma Kumaris : a spiritual revolution By Liz Hodgkinson

- ^ Omarkhali, Khanna (2017). The Yezidi religious textual tradition, from oral to written : categories, transmission, scripturalisation, and canonisation of the Yezidi oral religious texts : with samples of oral and written religious texts and with audio and video samples on CD-ROM. Wiesbaden. ISBN 978-3-447-10856-0. OCLC 994778968.

- ^ «Because angels are purely spiritual creatures without bodies, there is no sexual difference between them. There are no male or female angels; they are not distinguished by gender.», p. 10, «Catholic Questions, Wise Answers», Ed. Michael J. Daley, St. Anthony Messenger Press, 2001, ISBN 0867163984, 9780867163988. See also Catholic Answers, which gives the standard, unchanged, Catholic position.

- ^ «Angel», The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia James Orr, editor, 1915 edition.

- ^ Proverbio (2007), pp. 81–89; cf. review in La Civiltà Cattolica, 3795–3796 (2–16 August 2008), pp. 327–328.

- ^ Proverbio (2007) p. 66.

- ^ Proverbio (2007), pp. 90–95

- ^ Proverbio (2007) p. 34.

- ^ «History of the Church, 3:392». Institute.lds.org. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

Sources[edit]

- — (2002b). What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515713-0.

Further reading[edit]

- Bamberger, Bernard Jacob, (15 March 2006). Fallen Angels: Soldiers of Satan’s Realm. Jewish Publication Society of America. ISBN 0-8276-0797-0

- Barker, Margaret (2004). An Extraordinary Gathering of Angels, M Q Publications. ISBN 9781840726800

- Bennett, William Henry (1911), «Angel» , in Chisholm, Hugh (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 4–6

- Briggs, Constance Victoria, 1997. The Encyclopedia of Angels : An A-to-Z Guide with Nearly 4,000 Entries. Plume. ISBN 0-452-27921-6.

- Bunson, Matthew, (1996). Angels A to Z: A Who’s Who of the Heavenly Host. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-517-88537-9.

- Cheyne, James Kelly (ed.) (1899). Angel. Encyclopædia Biblica. New York, Macmillan.

- Cruz, Joan Carroll, OCDS, 1999. Angels and Devils. TAN Books and Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-89555-638-3

- Cummings, Owen F., 2023. Angels In Scripture and Tradition, Paulist Press, New Jersey. ISBN 978-08091-5633-7

- Davidson, A. B. (1898). «Angel». In James Hastings (ed.). A Dictionary of the Bible. Vol. I. pp. 93–97.

- Davidson, Gustav, (1967). A Dictionary of Angels: Including the Fallen Angels. Free Press. ISBN 0-02-907052-X

- Driver, Samuel Rolles (Ed.) (1901) The book of Daniel. Cambridge UP.

- Graham, Billy, 1994. Angels: God’s Secret Agents. W Pub Group; Minibook edition. ISBN 0-8499-5074-0

- Guiley, Rosemary, 1996. Encyclopedia of Angels. ISBN 0-8160-2988-1

- Jastrow, Marcus, 1996, A dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Bavli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic literature compiled by Marcus Jastrow, PhD., Litt.D. with and index of Scriptural quotatons, Vol 1 & 2, The Judaica Press, New York

- Kainz, Howard P., «Active and Passive Potency» in Thomistic Angelology Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 90-247-1295-5

- Kreeft, Peter J. 1995. Angels and Demons: What Do We Really Know About Them? Ignatius Press. ISBN 0-89870-550-9

- Leducq, M. H. (1853). «On the Origin and Primitive Meaning of the French word Ange». Proceedings of the Philological Society. 6 (132).

- Lewis, James R. (1995). Angels A to Z. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 0-7876-0652-9

- Melville, Francis, 2001. The Book of Angels: Turn to Your Angels for Guidance, Comfort, and Inspiration. Barron’s Educational Series; 1st edition. ISBN 0-7641-5403-6

- Michalak, Aleksander R. (2012), Angels as Warriors in Late Second Temple Jewish Literature.Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-151739-6.

- Muehlberger, Ellen (2013). Angels in Late Ancient Christianity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199931934

- Oosterzee, Johannes Jacobus van. Christian dogmatics: a text-book for academical instruction and private study. Trans. John Watson Watson and Maurice J. Evans. (1874) New York, Scribner, Armstrong.

- Proverbio, Cecilia (2007). La figura dell’angelo nella civiltà paleocristiana (in Italian). Assisi, Italy: Editrice Tau. ISBN 978-88-87472-69-1.

- Ronner, John, 1993. Know Your Angels: The Angel Almanac With Biographies of 100 Prominent Angels in Legend & Folklore-And Much More! Mamre Press. ISBN 0-932945-40-6.

- Smith, George Adam (1898) The book of the twelve prophets, commonly called the minor. London, Hodder and Stoughton.

- Smith, William Robertson (1878), «Angel» , in Baynes, T. S. (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, p. 26–28

- Swedenborg E. Heaven and its Wonders and Hell From Things Heard and Seen (Swedenborg Foundation 1946), ISBN 0-554-62056-1 (Detailed information on angels and their life in heaven)

- Swedenborg, E. Wisdom’s Delight in Marriage («Conjugial») Love: Followed by Insanity’s Pleasure in Promiscuous Love (Swedenborg Foundation 1979 ISBN 0-87785-054-2) (Extensive review of angelic marriage)

- von Heijne, Camilla, 2010. The Messenger of the Lord in Early Jewish Interpretations of Genesis. BZAW 412. De Gruyter, Berlin/New York, ISBN 978-3-11-022684-3

- von Heijne, Camilla, 2015 «Angels» pp. 20–24 in The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Bible and Theology, vol. 1. Oxford University Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-19-023994-7

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Angels.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Angels.

- Coptic Doxology of Heavenly Order

- Zoroastrian angels

- Jewish Encyclopedia entry on angels

- Directory on popular piety and the liturgy. Principles and guidelines Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. Directory of Popular Piety and the Liturgy, §§ 212–217, «The Holy Angels, Vatican City, December 2001]

- Angels, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Martin Palmer, Valery Rees & John Haldane (In Our Time, Mar. 24, 2005)

Other forms: angels

An angel is a messenger of God, characterized as having human form with wings and a halo. The word suggests goodness, and is often used to refer to someone who offers comfort and aid to others in times of trouble. As a child, you looked like an innocent angel; appearances can be deceiving.

The word angel derives from the Greek angelos, meaning «messenger.» It is used in the Bible to denote God’s attendants, with angels often depicted as being guardians of humans, an idea found in ancient Asian cultures as well. The Biblical sense was continued in a medieval gold coin called an angel, which depicted the archangel Michael. The word has been applied to angel fish, so named because they appear to have wings, and nurses, often called «angels of mercy.»

Definitions of angel

-

noun

spiritual being attendant upon God

-

noun

person of exceptional holiness

-

synonyms:

holy man, holy person, saint

see moresee less-

types:

-

Buddha

one who has achieved a state of perfect enlightenment

-

fakeer, fakir, faqir, faquir

a Muslim or Hindu mendicant monk who is regarded as a holy man

-

dervish

an ascetic Muslim monk; a member of an order noted for devotional exercises involving bodily movements

-

type of:

-

good person

a person who is good to other people

-

Buddha

-

noun

invests in a theatrical production

DISCLAIMER: These example sentences appear in various news sources and books to reflect the usage of the word ‘angel’.

Views expressed in the examples do not represent the opinion of Vocabulary.com or its editors.

Send us feedback

EDITOR’S CHOICE

Look up angel for the last time

Close your vocabulary gaps with personalized learning that focuses on teaching the

words you need to know.

Sign up now (it’s free!)

Whether you’re a teacher or a learner, Vocabulary.com can put you or your class on the path to systematic vocabulary improvement.

Get started

1

a

religion

: a spiritual being serving as a divine messenger and intermediary and often as a special protector of an individual or nation

c(1)

: an attendant usually benevolent spirit or guardian

—often used without implication of belief in its supernatural character

«A putting angel must have come to me during the night because I felt great today and every putt I hit was a great putt,» he [Paul McGinley] said.—

(2)

: the part of a person’s character or nature that is said to guide the person’s thoughts and behavior

… here was [Lyndon] Johnson charging straight at a problem, telling his fellow citizens an ugly truth about themselves while trying to invoke the better angels of their nature.—

[Lamar] Alexander concluded: «In his first inaugural address, Abraham Lincoln appealed to the better angels of our nature. If there are better angels of our nature, I guess that means there must be worse angels in us as well. …»—

2

: a usually white-robed winged figure of human form in fine art see also snow angel

4

: a person who is like an angel (as in looks or behavior)

Your toddler is such an angel.

Be an angel and get me a cup of tea, would you?

Childs is no angel either, and that gives his book its drama.—

5

Christian Science

: inspiration from God

6

: one who aids or supports with money or influence

Angels are considered one of the oldest sources of capital for start-up entrepreneurs; the term itself, by most accounts, comes from the affluent patrons who used to finance Broadway plays in the early twentieth century.—

Typically, angel investors put up anywhere from $10,000 to $50,000 to back a young start-up, and can fund as many as 10 companies at any given time.—

Synonyms

Example Sentences

Recent Examples on the Web

As the centurions fell to their knees, the angels approached the tomb, rolled away the stone in front, and stood aside as the few onlookers present got their first glimpse of Randall, dressed in a white robe and gold sash, beginning to stir inside.

—

Collab+Currency led the round and was joined by Slow Ventures, Menlo Ventures, Alumni Ventures Blockchain Fund, and other angels.

—

Dona Liston first saw the angel in the dying tree about two years ago.

—

Whiskey drinkers have heard about the angel‘s share, the portion of the liquid magically lost in the distilling process.

—

For even though the man at the bar was fully dressed, coat and all, the angel had been naked, his modesty preserved in profile.

—

Up in Heaven, we got married by the angels.

—

Christ is risen: The angels of God are rejoicing.

—

How luck the angels are to have you.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘angel.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Etymology

Middle English, from Old English engel & Anglo-French angele; both from Late Latin angelus, from Greek angelos, literally, messenger

First Known Use

before the 12th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1a

Time Traveler

The first known use of angel was

before the 12th century

Dictionary Entries Near angel

Cite this Entry

“Angel.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/angel. Accessed 14 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on angel

Last Updated:

13 Apr 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

White Angel. Fresco in the monastery Mileshevo, Serbia. XIII century

The word ‘angel’ comes from the Greek

‘angelos’, which means ‘a

messenger’. As far as we are concerned, in the way

in which we are related to the angels, they enter into our

life as messengers of God. This does not mean that there

is not in the angels an essence of their own, their own

essential being, and that they are nothing but messengers.

They are related as messengers to us; they are related to

God as his own creatures which have already attained a

measure of perfection and which grow eternally, endlessly

into a deeper and more perfect communion with their Maker.

Anyhow tonight my intention is not to speak of the angels

in their essential being, but to speak of them as they

appear in the scriptures and in the liturgical texts in

relation to the world in which we live, to mankind and its

destinies.

There are several ways in which one can be a messenger.

One can receive a message in which one does not

participate, which remains a thought, a will, which is

different from that of the messenger and conveyed to him

who is to receive it and capable of receiving it. There is

a way of being a messenger by being entrusted with the

thought, the will, the intention of God and commanded

creatively, that is, with the full and complete

participation of all one’s being, to convey it.

There is also a way in which the message and the person

can become so perfectly identified that the person and the

message coincide and that the revelation is as much in the

messenger as it is in the words proclaimed by him

<…>

A message may be brought, declared, left, as it were, with

the recipient. Something which is an experience of life

may be interpreted, explained, unfolded before him who is

already in possession of this inner knowledge. An angel

may also act and not only speak. But whichever way the

messenger appears, one can see in the Old Testament as

well as in the New, that a message is an act of God about

to happen. A message is a warning, a declaration of

something that will occur soon. You remember the angel

that appears to Zacharias at the beginning of St

Luke’s Gospel and to the Mother of God with the

promise of the birth of St John the Baptist to the one and

of the Incarnation of the Son of God to the other. You may

remember also in the Book of Job the passage in the 33rd

chapter in which Job longs for a mediator, an interpreter

of the will of God. He is confronted with this mystery. He

cannot understand the ways of God, and, apart from the

intercessor who is mentioned in the 9th chapter of this

book, he also longs for an interpreter: one who would make

sense of the mystery which confronts him, challenges him,

crushes him indeed and remains unrevealed.

In the Old and New Testaments the word ‘angel’

may be used with the definite article or with the

indefinite article, and some writers – and this is

the opinion nowadays of a great many of the students of

the Bible – see a difference in what is being

conveyed. ‘An angel’ in all the various

passages speaks of a concrete being, someone who appears

in the form of man, someone who can be seen, someone who

can be spoken to and heard, someone who can be touched and

can touch. In other passages the expression ‘the

angel of the Lord’ may (not always) signify a

message coming from the Lord with such directness and

certainty that there is no doubt that it is a divine

message, and yet no description is given of a celestial

being bringing and conveying the message.

<…>

In the beginning of St Matthew’s Gospel we are

confronted with a dream of Josephus. We are not told of a

concrete vision of an angel in the same plastic terms. It

seems that the expression is used to convey a certainty,

the certainty of a message that comes from God.

<…>

St Gregory Palamas spoke of angels in one of his works. He

calls them ‘second lights’. By this he means

– and my translation is very unsatisfactory –

that God is light, the only true Light, the light which is

the origin of all light, which enlightens every man that

comes into the world, and that the creatures of God, in

order to become children of light, must lose, indeed

must free themselves from their opacity in order to become

translucent and transparent so that the light which is God

himself should flow into them, pervade them to the core,

and that they should become such that this light divine

received by them unadulterated should be transmitted to

others.

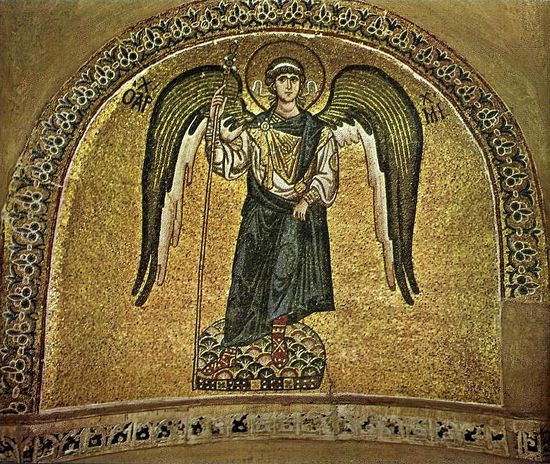

Archangel Gabriel. Mosaic. Hagia Sophia, Constantinople

He sees the angels as secondary sources of light because

they are of perfect transparency, they receive all divine

gifts without appropriating any of them to themselves;

they live by this flow of divine grace, divine light,

divine presence without trying to retain it, and handing

it on from hand to hand, as it were. There is an ancient

vision of things that teaches us that this light flows

from its original and unique source, which is God, through

the ranks of angels down from one step to another in a

cascade to the earthly created world in which it is also

received to the extent to which we are or become less

opaque, more translucent, more transparent, capable first

of receiving the light, participating in it, and freely

giving it farther and farther.

<…>

The experience of the Christians, the faith of the Church

has spoken also – and this can be referred to the

book of Revelation – of angels guardians of human

lives and souls, of angels that stand as the guardians of

human communities and places, temples, cities. The term

has evolved also to speak not only of the messengers but

also of him who stands in God’s own name as a

mediator, an intercessor, an interpreter of the truth of

God, one who proclaims that none is like God, one who

proclaims that God is strong, one who proclaims that God

heals, who proclaims the greatness of God, who calls to

prayer, who praises God in the name of his Church, who

brings down in sacraments and blessing the divine gifts

upon men. This is the link between the use of the word

angel, angelos, applied to the heavenly powers and the use

which St John the Divine makes of it in the Book of

Revelation when he calls the angels of the seven churches

the bishops that stand at the head of the human community.

Archangel Michael. Mosaic of the Monastery of Daphni. Greece

As you see, there is a vast range of notions and

experience which is held both by the Old and the New

Testament on the one hand and on the other hand by the

tradition of pre-Christian and post-Christian Israel

concerning the angels. The expression speaks of a

concrete, intense, palpable, tangible experience of the

Living God, the Holy Trinity, the Son of God, the Spirit

of God, of the concreteness and undoubted certainty of the

message received: the dream of Joseph and several dreams

of the Old Testament, of concrete, active, personal

messengers, in word or in deed, sent by God, Gabriel, the

angels that saved Peter and Paul from prison, and also

these heavenly powers whom God has appointed to teach, to

guide us, to help us to find our way. The names matter.

The reality matters. And when we celebrate services for

their feasts, we are not speaking of symbols; we are

entering into a deep relationship with real and concrete

realities but realities which perhaps with more

challenging violence, with a claim more powerful than

human sanctity, confront us with our vocation to be

God’s own. More than the human saints they compel us

to stand face to face with a message of God which in them

is fully realised, with a call of God to receive from him

a fulfillment which we can see in them and of which they

are the certainty and the guarantee.

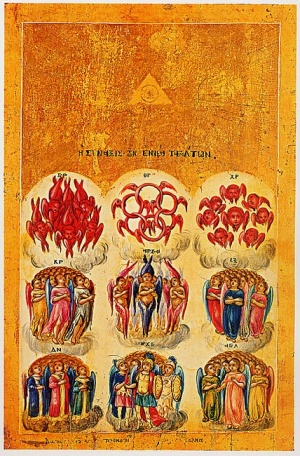

The word angel means «messenger» and this word expresses the nature of angelic service to the human race. Angels are also referred to as «bodiless Powers of Heaven». Angels are organized into several orders, or Angelic Choirs. The most influential of these classifications was that put forward by pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (not to be confused with Dionysius the Areopagite, who was baptized by Saint Paul and lived in the first century, and from whom pseudo-Dionysius took his name) in the fourth or fifth century in his book The Celestial Hierarchy.

In this work, the author interpolated several ambiguous passages from the New Testament, specifically Ephesians 6:12 and Colossians 1:16, to construct a schema of three Hierarchies, Spheres or Triads of angels, with each Hierarchy containing three Orders or Choirs. In descending order of power, these were:

- First Hierarchy:

- Seraphim

- Cherubim

- Thrones

- Second Hierarchy:

- Powers

- Dominions

- Principalities

- Third Hierarchy:

- Virtues

- Archangels

- Angels

The idea of there being ten initial Angelic hosts is taken from Judaism, this number possessing a very deep significance in Jewish mysticism, being the numeric value of the first letter of the Tetragrammaton, and symbolizing the Decalogue given to Moses on Mount Sinai and the ten plagues against the Egyptians, by which the Chosen People were delivered from captivity. There are several different listings of these ten Angelic ranks, which inevitably overlap to a certain degree; but whereas Judaism lost its ancient belief in the fall of Angels (witnessed, for instance, by the Book of Enoch), Christianity on the other hand preserved it, hence its teaching about the nine (remaining) Angelic orders, whose number shall be completed by the souls of those redeemed through the blood of the Lamb.

However, one should be a bit cautious about taking pseudo-Dionysius’ model too concretely, as he is the only source we have for such a classification system. The author himself was a fairly early advocate of apophatic theology, which insists on only describing God in the negative. Still, many have accused the writer of wavering somewhere in between Orthodoxy and Neoplatonism, a pagan Greek philosophical system; such critics say that the three groupings of three in the angelic hierarchy derive from Neoplatonism:

- The Hellenic concept of the world as «order» and «hierarchy,» the strict Platonic division between the «intelligible» and «sensible» worlds, and the Neoplatonic grouping of beings into «triads» reappear in the famous writings of a mysterious early-sixth-century writer who wrote under the pseudonym of Dionysius the Areopagite.1