Last year, there were 52 episodes of Music & the Spoken Word—there will be 52 this year—and there will be 52 next year. This is the way it’s been since July 1929, when the beautiful sounds of The Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square coming from the historic Tabernacle on Temple Square began to be a familiar Sunday morning soundtrack to people around the world.

Less than a year after the initial 1929 broadcast, Richard L. Evans was named as the first regular program narrator, a position he held until 1971. He was followed by J. Spencer Kinard, who served from 1972 to 1990. Since 1991, Lloyd Newell each week has delivered messages of inspiration, hope, joy, comfort, and love. These faithful messages are nondenominational and demonstrate universal principles, and they are filled with simple eloquence and uncommon wisdom.

Newell writes almost every single spoken word message and commented, “Because my responsibility is to come up with a spoken word every Sunday, I’m always pondering, reading, looking, and listening—always on the lookout for a story, thought, insight, anecdote, or principle that I can share on the broadcast. I look for angles, themes, and approaches that are fresh, new, insightful, and have universal appeal.”

When Newell received his calling to become the announcer of Music & the Spoken Word, LDS Church President Gordon B. Hinckley told him, “This call will change your life.” In fact it has, and he is most grateful for the opportunity. “What a great blessing, honor, and privilege it has been for me over these 27 years to give the spoken word every Sunday morning! I’m humbled and grateful to be a part of this beloved broadcast,” declared Newell.

When asked what his favorite spoken word messages throughout the many years are, Newell could not choose one over the other, comparing it to choosing a favorite child, saying, “It’s very difficult to pin down ‘favorite spoken words’ since they all come from the heart, from a specific and different place and time. In a sense, they’re all favorites. And in another sense, my ‘favorite’ is the last one I wrote and delivered on Sunday morning.”

Here are some recent spoken word messages that give a sense of Newell’s themes and thoughtful approach to his narratives.

On a hot summer afternoon, Monday, July, 15, 1929, using a borrowed microphone, the first broadcast of what would become known as Music and the Spoken Word originated from the Tabernacle on Temple Square in Salt Lake City, Utah.

The lone microphone was suspended from the ceiling, above the Choir, and the announcer, nineteen-year-old Ted Kimball, climbed a ladder to speak into the microphone and announce the songs. From that humble beginning has come the oldest continuous network program in broadcast history—a program that is enjoyed weekly by millions of people worldwide.

This volume commemorates those seventy-five years of broadcast excellence and recounts the history of the program and the lives of those individuals who have played principal roles in its production. With an introduction by Lloyd Newell and brief essays highlighting the history of the seven intervening decades, written by Stephen Wunderli, readers will be able to place the «spoken word» messages in their historical contexts.

The centerpiece of the book is a sampling of more than 140 messages, chosen from among the more than 3,600 that have been given—brief, nondenominational reflections on a myriad of uplifting, encouraging, heartwarming, and inspirational topics. Music and the Spoken Word has been loved by generations of listeners, who have em-braced not only the music of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir but also the simple eloquence and uncommon wisdom so comfortably dispensed by the three men whose distinctive voices are inexorably associated with this American broadcasting treasure.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

произнесенное слово

сказанное слово

устное слово

произнесенного слова

spoken word

изреченного слова

сказанного слова

устной речи

устного слова

изреченное слово

произносимого слова

произносимое слово

устную речь

разговорную речь

разговорный

You need to type the spoken word correctly using letters on the virtual keyboard.

Необходимо правильно набрать произнесенное слово по буквам на виртуальной клавиатуре.

When the spoken word is translated into action, it becomes Dharma (right action).

Когда произнесенное слово согласуется с делом, оно становится Дхармой (праведным действием).

She will never a spoken word take for granted.

Она никогда не будет принимать на веру любое лишь сказанное слово.

A rashly spoken word opens the gates and allows you to break into reality in order to destroy everyone around.

Опрометчиво сказанное слово открывает врата и позволяет ворваться в реальность, чтобы уничтожить всех вокруг.

I suggest that the spoken word as we know it came after the written word.

Я же предполагаю, что устное слово в том виде, в каком мы его знаем сейчас, возникло после слова письменного.

The spoken word goes into ears, the written word remains.

Shorthand is any system of rapid handwriting which can be used to transcribe the spoken word.

Сокращенные это любая система быстрого почерк, который можно использовать, чтобы расшифровать сказанное слово.

The spoken word is effective 30-40% of the time.

Well, the spoken word has different obstacles than the written word.

Но сказанное слово имеет совершенно другие параметры, чем написанное слово.

I decided it had to be something spoken word.

Я рассуждал, что это должно было быть какое-то матерное слово.

The spoken word can be forgotten.

О «речи» просто можно было забыть.

The spoken word is powerful indeed.

Слово, оказывается, действительно, великая сила.

Messages are often conveyed telepathically or mentally rather through spoken word.

Их речи часто передаются телепатически или умственно, а не через произносимые слова.

Some people communicate best through the spoken word.

Между тем, некоторые люди говорят лучше всего через речь.

Here the distance between the written and spoken word almost collapses.

Сейчас дистанция между письменным и разговорным языком намного уменьшилась.

It wasn’t just the spoken word that people were going to hear.

И это не та фраза, которую люди произнесли бы вслух.

This is so true with the spoken word.

Just one spoken word will stop all these things.

Таким образом, одно слово снимет все вопросы.

Not all spoken word artist do this but the best ones do.

Не каждый музыкант может сделать это, но лучшие могут.

It’s easy to understand that the spoken word has a vibration.

Результатов: 704. Точных совпадений: 704. Затраченное время: 80 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

This story appears here courtesy of TheChurchNews.com. It is not for use by other media.

By Christine Rappleye, Church News

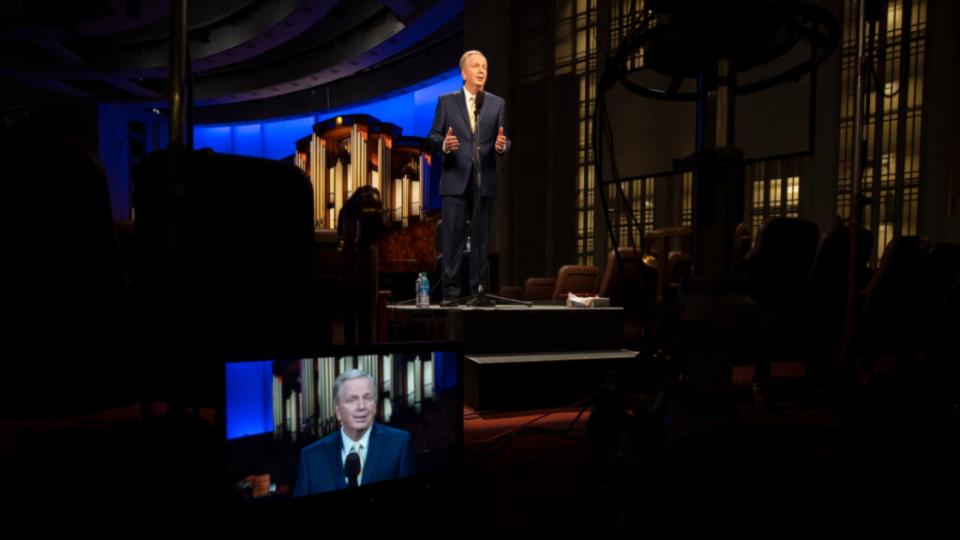

The Conference Center auditorium, which can seat up to 20,000 people, is empty except for a small crew around a platform with a camera and lights in the middle of an aisle in the lower section on a recent weekday afternoon.

When Lloyd Newell, who hosts the weekly “Music & the Spoken Word” broadcast, approaches and greets the crew, he’s in a suit and carrying a half-dozen colorful ties.

He stands on the platform with the towering organ pipes, vacant choir seats and orchestra area behind him. On cue, he begins to share a “Spoken Word” that is being recorded and will be inserted in a future Sunday morning broadcast. With a drink of water and a quick tie change while visiting with the masked producer and cameraman, he’s back on the platform preparing to record another one.

Newell officially became the announcer of “Music & the Spoken Word” 30 years ago, on March 31, 1991.

“The music is timeless,” Newell said. The “Spoken Word” message “gives us a chance to talk about what’s going on in the world and to offer perspective and hope.”

‘Spoken Word’ Announcers

The Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square’s Sunday morning show first aired more than 91 years ago on July 15, 1929, with 19-year-old Ted Kimball standing on a ladder to announce each musical number.

Richard L. Evans was the first regular announcer of “Music & the Spoken Word” from the summer of 1930 until 1971 — more than 41 years. Spence Kinard presented the “Spoken Word” from 1972 to 1990.

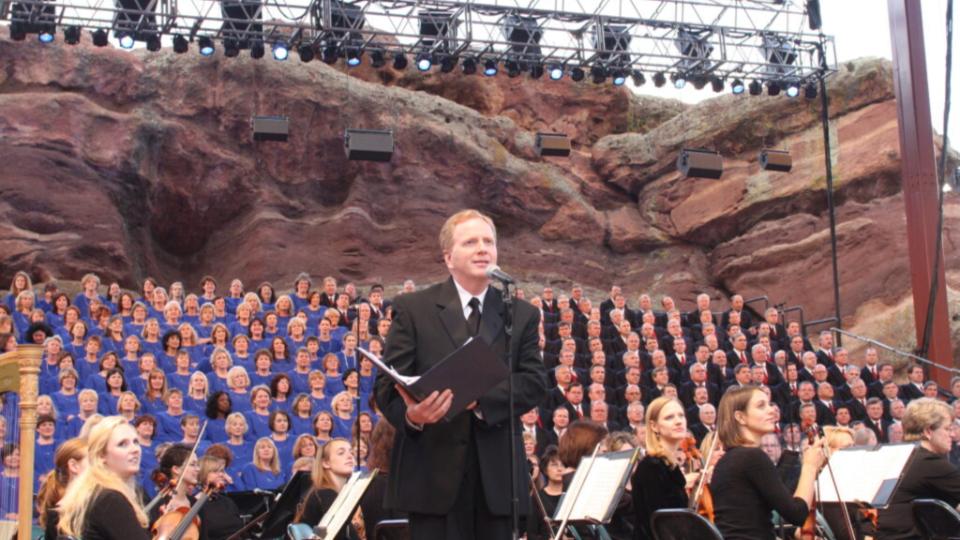

Lloyd Newell announces the program for the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square concert at Red Rocks Amphitheater near Denver, in 2009. Photo by Gerry Avant, courtesy of Church News.Copyright 2021 Deseret News Publishing Company.Newell-5.jpeg

Newell’s first official time presenting the “Spoken Word” was on March 31, 1991. He had been filling in since the end of November 1990.

When he was extended the calling, President Gordon B. Hinckley, then a counselor in the First Presidency, said that each week’s message needed to be an “inspirational gem.”

“Those two words ring in my ears and in my heart all the time,” he said. When he writes the “Spoken Word” messages, he will ask himself: “Is this an inspirational gem? Does it enlighten and inspire? Does it add an insight or perspective that is wise and interesting and encouraging?”

President Hinckley also told him that this call would change his life, Newell said. “President Hinckley was right, it has changed my life and my family’s life for the better. He understood it far better than I did. … I think he certainly had a greater vision for it than I did at the time.”

Newell had worked as television anchor and at the time of his call was traveling the world as a corporate trainer and consultant.

“When I did the news, no one ever came up to me after a newscast and said that newscast really touched my heart or that really made a difference in my life,” he said. But with the “Spoken Word” messages, “I’m blessed to hear that all the time.”

30 Years Ago

When Newell began, he was single. Now, he’s married with four grown children and grandchildren.

When he announced his engagement to Karmel Howell in January 1992, the choir serenaded them with “Let Me Call You Sweetheart,” according to information from the choir. Through the years, his family would watch it “live” on television and also record the broadcast so they could watch it later in the day.

Newell credits his wife and family for their constant support over the many years. “I could not have done this calling without my wife by my side, and the love and support of my family.”

Lloyd Newell has officially been the voice of the Tabernacle Choir since 1991. Photo by Tom Smart, courtesy of Church News.Copyright 2021 Deseret News Publishing Company.Newell-8.jpeg

Newell, who is a professor of religious education at Brigham Young University, works several weeks in advance on the “Spoken Word” messages. Ideas come from everywhere and anywhere. And he doesn’t have a favorite — it’s too difficult to pick just one.

“My antenna is always raised because I’m always looking for ideas and stories, universal principles and timeless truths that would make for a good ‘Spoken Word,’” Newell said.

With a visible calling that he makes look easy, Newell said there have been personal challenges along the way.

“I’ve had many times of feeling inadequate,” Newell said. “How can I capture what I want to say or what I’m feeling and how can I deliver it in a way that would make a difference?”

When he writes the “Spoken Word,” he tries to think of a person. For many years, that person was his late mother. Sometimes, it will be a person in the congregation. Other times, another loved one or friend or someone he knows.

As he reflected on 30 years of his association with the choir, Newell highlights the opportunities of touring with the choir and orchestra as they’ve performed in the United States and across the world and presenting a “Spoken Word” message during the concerts, along with building relationships with people, from those performing to those behind the cameras and in the production booths. And since his weekly “Spoken Words” are nondenominational messages, he treasures the many associations and interactions he’s had with people from all walks of life and all religious backgrounds across the world.

“The essence of the broadcast remains still the same,” Newell said of the program. “There is beautiful music from the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square and an inspirational message. It’s different now as the technology has changed with more digital equipment and modern technology and that it goes beyond a radio and TV program to reaching countless people through online platforms.

“With this broadcast, we’re trying to spread hope and goodness, truth and light,” he said.

Encore Performances

When the COVID-19 pandemic started more than a year ago and many events shut down or were paused, including the Tabernacle Choir and Orchestra at Temple Square’s events and rehearsals, Newell found himself at home on Sunday mornings.

“It was very strange,” Newell said with a smile. While his family has been able to celebrate Sunday holidays, such as Mother’s Day, Father’s Day and Easter, in a more traditional way, he’s felt like there should be something more that he could do.

Lloyd Newell records several upcoming portions of “Music & the Spoken Word” inside the Conference Center in Salt Lake City on Wednesday, April 7, 2021. Newell is celebrating his 30th anniversary as announcer of the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square. Photo by Scott G. Winterton, courtesy of Church News.Copyright 2021 Deseret News Publishing Company.Newell-4.jpg

The Sunday morning “Music & the Spoken Word” continued to air from the repertoire of previous broadcasts and have been selected by choir director Mack Wilberg.

“We talked and asked, ‘Can we offer something?’” Newell said. “The one thing we can change without too much difficulty is the ‘Spoken Word.’”

Last summer, he started again writing more “Spoken Word” messages and they recorded a few that aired in the fall. And they recorded a few more in September that were also broadcast. They received encouragement to do the new “Spoken Word” messages at the end of December and have been doing them ever since.

“We can’t bring in 500 choir and orchestra members together right now, but I can come in with a small crew,” Newell said. “I never would have dreamed of recording ‘Spoken Word’ messages, and inserting them into previously aired broadcasts, but it’s such a wonderful way for us to be able to talk about this world that we’re living in and offer renewed hope and insight.”

On that recent afternoon in the nearly empty Conference Center, he recorded a half-dozen “Spoken Word” messages, changing ties between each one. Unlike the live broadcasts, he can rerecord these, if needed. As the production team is editing these into previous shows, he tries to make it closely fit in the time of the “Spoken Word” in the previous broadcast.

But, there is something unique about the energy of a live broadcast, he said.

“People are wondering and worried about the future and some are even losing hope,” he said. “We want to be a beacon of hope and light and truth and goodness to say there is goodness out there, there’s hope available — so stay with it and keep going. And just like this broadcast will be back in the coming day, we will be back as a nation and world.”

Copyright 2021 Deseret News Publishing Company

Style Guide Note:When reporting about The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, please use the complete name of the Church in the first reference. For more information on the use of the name of the Church, go to our online Style Guide.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about a performance art. For recordings of books or dialog, see Audiobook. For the 2009 film, see Spoken Word (film).

Spoken word refers to an oral poetic performance art that is based mainly on the poem as well as the performer’s aesthetic qualities. It is a late 20th century continuation of an ancient oral artistic tradition that focuses on the aesthetics of recitation and word play, such as the performer’s live intonation and voice inflection. Spoken word is a «catchall» term that includes any kind of poetry recited aloud, including poetry readings, poetry slams, jazz poetry, and hip hop music, and can include comedy routines and prose monologues.[1] Unlike written poetry, the poetic text takes its quality less from the visual aesthetics on a page, but depends more on phonaesthetics, or the aesthetics of sound.

History[edit]

Spoken word has existed for many years; long before writing, through a cycle of practicing, listening and memorizing, each language drew on its resources of sound structure for aural patterns that made spoken poetry very different from ordinary discourse and easier to commit to memory.[2] «There were poets long before there were printing presses, poetry is primarily oral utterance, to be said aloud, to be heard.»[3]

Poetry, like music, appeals to the ear, an effect known as euphony or onomatopoeia, a device to represent a thing or action by a word that imitates sound.[4] «Speak again, Speak like rain» was how Kikuyu, an East African people, described her verse to author Isak Dinesen,[5] confirming a comment by T. S. Eliot that «poetry remains one person talking to another».[6]

The oral tradition is one that is conveyed primarily by speech as opposed to writing,[7] in predominantly oral cultures proverbs (also known as maxims) are convenient vehicles for conveying simple beliefs and cultural attitudes.[8] «The hearing knowledge we bring to a line of poetry is a knowledge of a pattern of speech we have known since we were infants».[9]

Performance poetry, which is kindred to performance art, is explicitly written to be performed aloud[10] and consciously shuns the written form.[11] «Form», as Donald Hall records «was never more than an extension of content.»[12]

Performance poetry in Africa dates to prehistorical times with the creation of hunting poetry, while elegiac and panegyric court poetry were developed extensively throughout the history of the empires of the Nile, Niger and Volta river valleys.[13] One of the best known griot epic poems was created for the founder of the Mali Empire, the Epic of Sundiata. In African culture, performance poetry is a part of theatrics, which was present in all aspects of pre-colonial African life[14] and whose theatrical ceremonies had many different functions: political, educative, spiritual and entertainment. Poetics were an element of theatrical performances of local oral artists, linguists and historians, accompanied by local instruments of the people such as the kora, the xalam, the mbira and the djembe drum. Drumming for accompaniment is not to be confused with performances of the «talking drum», which is a literature of its own, since it is a distinct method of communication that depends on conveying meaning through non-musical grammatical, tonal and rhythmic rules imitating speech.[15][16] Although, they could be included in performances of the griots.

In ancient Greece, the spoken word was the most trusted repository for the best of their thought, and inducements would be offered to men (such as the rhapsodes) who set themselves the task of developing minds capable of retaining and voices capable of communicating the treasures of their culture.[17] The Ancient Greeks included Greek lyric, which is similar to spoken-word poetry, in their Olympic Games.[18]

Development in the United States[edit]

This poem is about the International Monetary Fund; the poet expresses his political concerns about the IMF’s practices and about globalization.

Vachel Lindsay helped maintain the tradition of poetry as spoken art in the early twentieth century.[19] Robert Frost also spoke well, his meter accommodating his natural sentences.[20] Poet laureate Robert Pinsky said, «Poetry’s proper culmination is to be read aloud by someone’s voice, whoever reads a poem aloud becomes the proper medium for the poem.»[21] «Every speaker intuitively courses through manipulation of sounds, it is almost as though ‘we sing to one another all day’.»[9] «Sound once imagined through the eye gradually gave body to poems through performance, and late in the 1950s reading aloud erupted in the United States.»[20]

Some American spoken-word poetry originated from the poetry of the Harlem Renaissance,[22] blues, and the Beat Generation of the 1960s.[23] Spoken word in African-American culture drew on a rich literary and musical heritage. Langston Hughes and writers of the Harlem Renaissance were inspired by the feelings of the blues and spirituals, hip-hop, and slam poetry artists were inspired by poets such as Hughes in their word stylings.[24]

The Civil Rights Movement also influenced spoken word. Notable speeches such as Martin Luther King Jr.’s «I Have a Dream», Sojourner Truth’s «Ain’t I a Woman?», and Booker T. Washington’s «Cast Down Your Buckets» incorporated elements of oration that influenced the spoken word movement within the African-American community.[24] The Last Poets was a poetry and political music group formed during the 1960s that was born out of the Civil Rights Movement and helped increase the popularity of spoken word within African-American culture.[25] Spoken word poetry entered into wider American culture following the release of Gil Scott-Heron’s spoken-word poem «The Revolution Will Not Be Televised» on the album Small Talk at 125th and Lenox in 1970.[26]

The Nuyorican Poets Café on New York’s Lower Eastside was founded in 1973, and is one of the oldest American venues for presenting spoken-word poetry.[27]

In the 1980s, spoken-word poetry competitions, often with elimination rounds, emerged and were labelled «poetry slams». American poet Marc Smith is credited with starting the poetry slam in November 1984.[18] In 1990, the first National Poetry Slam took place in Fort Mason, San Francisco.[28] The poetry slam movement reached a wider audience following Russell Simmons’ Def Poetry, which was aired on HBO between 2002 and 2007. The poets associated with the Buffalo Readings were active early in the 21st century.

International development[edit]

Kenyan spoken word poet Mumbi Macharia.

Outside of the United States, artists such as French singer-songwriters Léo Ferré and Serge Gainsbourg made personal use of spoken word over rock or symphonic music from the beginning of the 1970s in such albums as Amour Anarchie (1970), Histoire de Melody Nelson (1971), and Il n’y a plus rien (1973), and contributed to the popularization of spoken word within French culture.

In the UK, musicians who have performed spoken word lyrics include Blur,[29] The Streets and Kae Tempest.

In 2003, the movement reached its peak in France with Fabien Marsaud aka Grand Corps Malade being a forerunner of the genre.[30][31]

In Zimbabwe spoken word has been mostly active on stage through the House of Hunger Poetry slam in Harare, Mlomo Wakho Poetry Slam in Bulawayo as well as the Charles Austin Theatre in Masvingo. Festivals such as Harare International Festival of the Arts, Intwa Arts Festival KoBulawayo and Shoko Festival have supported the genre for a number of years.[32]

In Nigeria, there are poetry events such as Wordup by i2x Media, The Rendezvous by FOS (Figures Of Speech movement), GrrrAttitude by Graciano Enwerem, SWPC which happens frequently, Rhapsodist, a conference by J19 Poetry and More Life Concert (an annual poetry concert in Port Harcourt) by More Life Poetry. Poets Amakason, ChidinmaR, oddFelix, Kormbat, Moje, Godzboi, Ifeanyi Agwazia, Chinwendu Nwangwa, Worden Enya, Resame, EfePaul, Dike Chukwumerije, Graciano Enwerem, Oruz Kennedy, Agbeye Oburumu, Fragile MC, Lyrical Pontiff, Irra, Neofloetry, Toby Abiodun, Paul Word, Donna, Kemistree and PoeThick Samurai are all based in Nigeria. Spoken word events in Nigeria[33] continues to grow traction, with new, entertaining and popular spoken word events like The Gathering Africa, a new fusion of Poetry, Theatre, Philosophy and Art, organized 3 times a year by the multi-talented beauty Queen, Rei Obaigbo [34] and the founder [35] of Oreime.com.

In Trinidad and Tobago, this art form is widely used as a form of social commentary and is displayed all throughout the nation at all times of the year. The main poetry events in Trinidad and Tobago are overseen by an organization called the 2 Cent Movement. They host an annual event in partnership with the NGC Bocas Lit Fest and First Citizens Bank called «The First Citizens national Poetry Slam», formerly called «Verses». This organization also hosts poetry slams and workshops for primary and secondary schools. It is also involved in social work and issues.

In Ghana, the poetry group Ehalakasa led by Kojo Yibor Kojo AKA Sir Black, holds monthly TalkParty events (collaborative endeavour with Nubuke Foundation and/ National Theatre of Ghana) and special events such as the Ehalakasa Slam Festival and end-of-year events. This group has produced spoken-word poets including, Mutombo da Poet,[36] Chief Moomen, Nana Asaase, Rhyme Sonny, Koo Kumi, Hondred Percent, Jewel King, Faiba Bernard, Akambo, Wordrite, Natty Ogli, and Philipa.

The spoken word movement in Ghana is rapidly growing that individual spoken word artists like MEGBORNA,[37] are continuously carving a niche for themselves and stretching the borders of spoken word by combining spoken word with 3D animations and spoken word video game, based on his yet to be released poem, Alkebulan.

Megborna performing at the First Kvngs Edition of the Megborna Concert, 2019

In Kumasi, the creative group CHASKELE holds an annual spoken word event on the campus of KNUST giving platform to poets and other creatives. Poets like Elidior The Poet, Slimo, T-Maine are key members of this group.

In Kenya, poetry performance grew significantly between the late 1990s and early 2000s. This was through organisers and creative hubs such as Kwani Open Mic, Slam Africa, Waamathai’s, Poetry at Discovery, Hisia Zangu Poetry, Poetry Slam Africa, Paza Sauti, Anika, Fatuma’s Voice, ESPA, Sauti dada, Wenyewe poetry among others. Soon the movement moved to other counties and to universities throughout the country. Spoken word in Kenya has been a means of communication where poets can speak about issues affecting young people in Africa. Some of the well known poets in Kenya are Dorphan, Kenner B, Namatsi Lukoye, Raya Wambui, Wanjiku Mwaura, Teardrops, Mufasa, Mumbi Macharia, Qui Qarre, Sitawa Namwalie, Sitawa Wafula, Anne Moraa, Ngwatilo Mawiyo, Stephen Derwent.[38]

In Israel, in 2011 there was a monthly Spoken Word Line in a local club in Tel-Aviv by the name of: «Word Up!». The line was organized by Binyamin Inbal and was the beginning of a successful movement of spoken word lovers and performers all over the country.

Competitions[edit]

Spoken-word poetry is often performed in a competitive setting. In 1990, the first National Poetry Slam was held in San Francisco.[18] It is the largest poetry slam competition event in the world, now held each year in different cities across the United States.[39] The popularity of slam poetry has resulted in slam poetry competitions being held across the world, at venues ranging from coffeehouses to large stages.

Movement[edit]

Spoken-word poetry is typically more than a hobby or expression of talent. This art form is often used to convey important or controversial messages to society. Such messages often include raising awareness of topics such as: racial inequality, sexual assault and/or rape culture, anti-bullying messages, body-positive campaigns, and LGBT topics. Slam poetry competitions often feature loud and radical poems that display both intense content and sound. Spoken-word poetry is also abundant on college campuses, YouTube, and through forums such as Button Poetry.[40] Some spoken-word poems go viral and can then appear in articles, on TED talks, and on social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

See also[edit]

- Greek lyric

- Griot

- Haikai prose

- Hip hop

- List of performance poets

- Nuyorican Poets Café

- Oral poetry

- Performance poetry

- Poetry reading

- Prose rhythm

- Prosimetrum

- Purple prose

- Rapping

- Recitative

- Rhymed prose

- Slam poetry

References[edit]

- ^ Hirsch, Edward (April 8, 2014). A Poet’s Glossary. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0151011957.

- ^ Hollander, John (1996). Committed to Memory. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781573226462.

- ^ Knight, Etheridge (1988). «On the Oral Nature of Poetry». The Black Scholar. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis. 19 (4–5): 92–96. doi:10.1080/00064246.1988.11412887.

- ^ Kennedy, X. J.; Gioia, Dana (1998). An Introduction to Poetry. Longman. ISBN 9780321015563.

- ^ Dinesen, Isak (1972). Out of Africa. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0679600213.

- ^ Eliot, T. S. (1942), «The Music of Poetry» (lecture). Glasgow: Jackson.

- ^ The American Heritage Guide to Contemporary Usage and Style. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2005. ISBN 978-0618604999.

- ^ Ong, Walter J. (1982). Orality and Literacy: Cultural Attitudes. Metheun.

- ^ a b Pinsky, Robert (1999). The Sounds of Poetry: A Brief Guide. Farrar Straus & Giroux. ISBN 9780374526177.

- ^ Hirsch, Edward (2014). A Poets Glossary. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780151011957.

- ^ Parker, Sam (December 16, 2009). «Three-minute poetry? It’s all the rage». The Times.

- ^ Olson, Charles (1950). «‘Projective Verse’: Essay on Poetic Theory». Pamphlet.

- ^ Finnegan, Ruth (2012), Oral Literature in Africa, Open Book Publishers.

- ^ John Conteh-Morgan, John (1994), «African Traditional Drama and Issues in Theater and Performance Criticism», Comparative Drama.

- ^ Finnegan (2012), Oral Literature in Africa, pp. 467-484.

- ^ Stern, Theodore (1957), Drum and Whistle Languages: An Analysis of Speech Surrogates, University of Oregon.

- ^ Bahn, Eugene; Bahn, Margaret L. (1970). A History of Oral Performance. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Burgess. p. 10.

- ^ a b c Glazner, Gary Mex (2000). Poetry Slam: The Competitive Art of Performance Poetry. San Francisco: Manic D.

- ^ ‘Reading list, Biography – Vachel Lindsay’ Poetry Foundation.org Chicago 2015

- ^ a b Hall, Donald (October 26, 2012). «Thank You Thank You». The New Yorker. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ^ Sleigh, Tom (Summer 1998). «Robert Pinsky». Bomb.

- ^ O’Keefe Aptowicz, Cristin (2008). Words in Your Face: A Guided Tour through Twenty Years of the New York City Poetry Slam. New York: Soft Skull Press. ISBN 978-1-933368-82-5.

- ^ Neal, Mark Anthony (2003). The Songs in the Key of Black Life: A Rhythm and Blues Nation. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96571-3.

- ^ a b «Say It Loud: African American Spoken Word». Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ «The Last Poets». www.nsm.buffalo.edu. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (May 28, 2011), Ben Sisario, «Gil Scott-Heron, Voice of Black Protest Culture, Dies at 62», The New York Times.

- ^ «The History of Nuyorican Poetry Slam» Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Verbs on Asphalt.

- ^ «PSI FAQ: National Poetry Slam». Archived from the original on October 29, 2013.

- ^ DeGroot, Joey (April 23, 2014). «7 Great songs with Spoken Word Lyrics». MusicTimes.com.

- ^ «Grand Corps Malade — Biography | Billboard». www.billboard.com. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ^ «Grand Corps Malade». France Today. July 11, 2006. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ Muchuri, Tinashe (May 14, 2016). «Honour Eludes local writers». NewsDay. Zimbabwe. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ Independent, Agency (2 February 2022). «The Gathering Africa, Spokenword Event by Oreime.com». Independent. p. 1. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ «Tarere Obaigbo: 2021 Mrs. Nigeria Gears Up for Global Stage». THISDAYLIVE. 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ «Tarere Obaigbo, Founder Of The Gathering Africa, Wins Mrs Nigeria Pageant — Olisa.tv». 2021-05-19. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ «Mutombo The Poet of Ghana presents Africa’s spoken word to the world». TheAfricanDream.net. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ «Meet KNUST finest spoken word artist, Chris Parker ‘Megborna’«. hypercitigh.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-28.

- ^ Ekesa, Beatrice Jane (2020-08-18). «Integration of Work and Leisure in the Performance of Spoken Word Poetry in Kenya». Journal of Critical Studies in Language and Literature. 1 (3): 9–13. doi:10.46809/jcsll.v1i3.23. ISSN 2732-4605.

- ^ Poetry Slam, Inc. Web. November 28, 2012.

- ^ «Home — Button Poetry». Button Poetry.

Further reading[edit]

- «5 Tips on Spoken Word». Power Poetry.org. 2015.

External links[edit]

- Poetry aloud – examples

|

|

В этой статье не хватает ссылок на источники информации.

Информация должна быть проверяема, иначе она может быть поставлена под сомнение и удалена. |

Spoken word (в переводе с английского: произносимое слово) — форма литературного, а иногда и ораторского искусства, художественное выступление, в котором текст, стихи, истории, эссе больше говорятся, чем поются. Термин часто используется (особенно в англоязычных странах) для обозначения соответствующей CD-продукции, не являющейся музыкальной.

Формами «spoken word» могут быть как литературные чтения, чтения стихов и рассказов, доклады, так и поток сознания, и популярные в последнее время политические и социальные комментарии артистов в художественной или театральной форме. Нередко артистами в жанре «spoken word» бывают поэты и музыканты. Иногда голос сопровождается музыкой, но музыка в этом жанре совершенно необязательна.

Так же как и с музыкой, со «spoken word» выпускаются альбомы, видеорелизы, устраиваются живые выступления и турне.

Среди русскоязычных артистов в этом жанре можно отметить Дмитрия Гайдука и альбом Пожары, группы Сансара (Екб.) и рэп группу Marselle (L`One и Nel)

Некоторые представители жанра

(в алфавитном порядке)

- Бликса Баргельд

- Уильям Берроуз

- Бойд Райс

- Джелло Биафра

- GG Allin

- Дмитрий Гайдук

- Аллен Гинзберг

- Джек Керуак

- Лидия Ланч

- Евгений Гришковец

- Егор Летов

- Джим Моррисон

- Лу Рид

- Генри Роллинз

- Патти Смит

- Серж Танкян

- Том Уэйтс

- Дэвид Тибет

- Levi The Poet

- Listener

См. также

- Декламационный стих

- Мелодекламация

- Речитатив

- Художественное чтение