| Sahara | |

|---|---|

The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972 |

|

Geographical map of the Sahara |

|

| Length | 4,800 km (3,000 mi) |

| Width | 1,800 km (1,100 mi) |

| Area | 9,200,000 km2 (3,600,000 sq mi) |

| Naming | |

| Native name |

|

| Geography | |

| Countries |

List

|

| Coordinates | 23°N 13°E / 23°N 13°ECoordinates: 23°N 13°E / 23°N 13°E |

The Sahara (, ) is a desert on the African continent. With an area of 9,200,000 square kilometres (3,600,000 sq mi), it is the largest hot desert in the world and the third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Arctic.[1][2][3]

The name «Sahara» is derived from the Arabic word for «desert» in the feminine irregular form, the singular ṣaḥra’ (صحراء /ˈsˤaħra/), plural ṣaḥārā (صَحَارَى /ˈsˤaħaːraː/),[4][5][6][7] ṣaḥār (صَحَار), ṣaḥrāwāt (صَحْرَاوَات), ṣaḥāriy (صَحَارِي).

The desert comprises much of North Africa, excluding the fertile region on the Mediterranean Sea coast, the Atlas Mountains of the Maghreb, and the Nile Valley in Egypt and the Sudan. It stretches from the Red Sea in the east and the Mediterranean in the north to the Atlantic Ocean in the west, where the landscape gradually changes from desert to coastal plains. To the south it is bounded by the Sahel, a belt of semi-arid tropical savanna around the Niger River valley and the Sudan region of sub-Saharan Africa. The Sahara can be divided into several regions, including the western Sahara, the central Ahaggar Mountains, the Tibesti Mountains, the Aïr Mountains, the Ténéré desert, and the Libyan Desert.

For several hundred thousand years, the Sahara has alternated between desert and savanna grassland in a 20,000-year cycle[8] caused by the precession of Earth’s axis as it rotates around the Sun, which changes the location of the North African monsoon.

Geography

The main biomes in Africa

The Sahara covers large parts of Algeria, Chad, Egypt, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Western Sahara, Sudan and Tunisia. It covers 9 million square kilometres (3,500,000 sq mi), amounting to 31% of Africa. If all areas with a mean annual precipitation of less than 250 mm were included, the Sahara would be 11 million square kilometres (4,200,000 sq mi). It is one of three distinct physiographic provinces of the African massive physiographic division. Sahara is so large and bright that, in theory, it could be detected from other stars as a surface feature of Earth, with near-current technology.[9]

The Sahara is mainly rocky hamada (stone plateaus); ergs (sand seas – large areas covered with sand dunes) form only a minor part, but many of the sand dunes are over 180 metres (590 ft) high.[10] Wind or rare rainfall shape the desert features: sand dunes, dune fields, sand seas, stone plateaus, gravel plains (reg), dry valleys (wadi), dry lakes (oued), and salt flats (shatt or chott).[11] Unusual landforms include the Richat Structure in Mauritania.

Several deeply dissected mountains, many volcanic, rise from the desert, including the Aïr Mountains, Ahaggar Mountains, Saharan Atlas, Tibesti Mountains, Adrar des Iforas, and the Red Sea Hills. The highest peak in the Sahara is Emi Koussi, a shield volcano in the Tibesti range of northern Chad.

The central Sahara is hyperarid, with sparse vegetation. The northern and southern reaches of the desert, along with the highlands, have areas of sparse grassland and desert shrub, with trees and taller shrubs in wadis, where moisture collects. In the central, hyperarid region, there are many subdivisions of the great desert: Tanezrouft, the Ténéré, the Libyan Desert, the Eastern Desert, the Nubian Desert and others. These extremely arid areas often receive no rain for years.

To the north, the Sahara skirts the Mediterranean Sea in Egypt and portions of Libya, but in Cyrenaica and the Maghreb, the Sahara borders the Mediterranean forest, woodland, and scrub eco-regions of northern Africa, all of which have a Mediterranean climate characterized by hot summers and cool and rainy winters. According to the botanical criteria of Frank White[12] and geographer Robert Capot-Rey,[13][14] the northern limit of the Sahara corresponds to the northern limit of date palm cultivation and the southern limit of the range of esparto, a grass typical of the Mediterranean climate portion of the Maghreb and Iberia. The northern limit also corresponds to the 100 mm (3.9 in) isohyet of annual precipitation.[15]

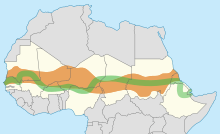

To the south, the Sahara is bounded by the Sahel, a belt of dry tropical savanna with a summer rainy season that extends across Africa from east to west. The southern limit of the Sahara is indicated botanically by the southern limit of Cornulaca monacantha (a drought-tolerant member of the Chenopodiaceae), or northern limit of Cenchrus biflorus, a grass typical of the Sahel.[13][14] According to climatic criteria, the southern limit of the Sahara corresponds to the 150 mm (5.9 in) isohyet of annual precipitation (this is a long-term average, since precipitation varies annually).[15]

Important cities located in the Sahara include Nouakchott, the capital of Mauritania; Tamanrasset, Ouargla, Béchar, Hassi Messaoud, Ghardaïa, and El Oued in Algeria; Timbuktu in Mali; Agadez in Niger; Ghat in Libya; and Faya-Largeau in Chad.

Climate

The Sahara is the world’s largest hot desert.[16] It is located in the horse latitudes under the subtropical ridge, a significant belt of semi-permanent subtropical warm-core high pressure where the air from the upper troposphere usually descends, warming and drying the lower troposphere and preventing cloud formation.[citation needed]

The permanent absence of clouds allows unhindered light and thermal radiation. The stability of the atmosphere above the desert prevents any convective overturning, thus making rainfall virtually non-existent. As a consequence, the weather tends to be sunny, dry and stable with a minimal chance of rainfall. Subsiding, diverging, dry air masses associated with subtropical high-pressure systems are extremely unfavorable for the development of convectional showers. The subtropical ridge is the predominant factor that explains the hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh) of this vast region. The descending airflow is the strongest and the most effective over the eastern part of the Great Desert, in the Libyan Desert: this is the sunniest, driest and the most nearly «rainless» place on the planet, rivaling the Atacama Desert, lying in Chile and Peru.

The rainfall inhibition and the dissipation of cloud cover are most accentuated over the eastern section of the Sahara rather than the western. The prevailing air mass lying above the Sahara is the continental tropical (cT) air mass, which is hot and dry. Hot, dry air masses primarily form over the North-African desert from the heating of the vast continental land area, and it affects the whole desert during most of the year. Because of this extreme heating process, a thermal low is usually noticed near the surface, and is the strongest and the most developed during the summertime. The Sahara High represents the eastern continental extension of the Azores High,[citation needed] centered over the North Atlantic Ocean. The subsidence of the Sahara High nearly reaches the ground during the coolest part of the year, while it is confined to the upper troposphere during the hottest periods.

The effects of local surface low pressure are extremely limited because upper-level subsidence still continues to block any form of air ascent. Also, to be protected against rain-bearing weather systems by the atmospheric circulation itself, the desert is made even drier by its geographical configuration and location. Indeed, the extreme aridity of the Sahara is not only explained by the subtropical high pressure: the Atlas Mountains of Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia also help to enhance the aridity of the northern part of the desert. These major mountain ranges act as a barrier, causing a strong rain shadow effect on the leeward side by dropping much of the humidity brought by atmospheric disturbances along the polar front which affects the surrounding Mediterranean climates.

The primary source of rain in the Sahara is the Intertropical Convergence Zone, a continuous belt of low-pressure systems near the equator which bring the brief, short and irregular rainy season to the Sahel and southern Sahara. Rainfall in this giant desert has to overcome the physical and atmospheric barriers that normally prevent the production of precipitation. The harsh climate of the Sahara is characterized by: extremely low, unreliable, highly erratic rainfall; extremely high sunshine duration values; high temperatures year-round; negligible rates of relative humidity; a significant diurnal temperature variation; and extremely high levels of potential evaporation which are the highest recorded worldwide.[17]

Temperature

The sky is usually clear above the desert, and the sunshine duration is extremely high everywhere in the Sahara. Most of the desert has more than 3,600 hours of bright sunshine per year (over 82% of daylight hours), and a wide area in the eastern part has over 4,000 hours of bright sunshine per year (over 91% of daylight hours). The highest values are very close to the theoretical maximum value. A value of 4300 hours (98%) of the time would be[clarification needed] recorded in Upper Egypt (Aswan, Luxor) and in the Nubian Desert (Wadi Halfa).[18] The annual average direct solar irradiation is around 2,800 kWh/(m2 year) in the Great Desert. The Sahara has a huge potential for solar energy production.

The high position of the Sun, the extremely low relative humidity, and the lack of vegetation and rainfall make the Great Desert the hottest large region in the world, and the hottest place on Earth during summer in some spots. The average high temperature exceeds 38 to 40 °C or 100.4 to 104.0 °F during the hottest month nearly everywhere in the desert except at very high altitudes. The world’s highest officially recorded average daily high temperature[clarification needed] was 47 °C or 116.6 °F in a remote desert town in the Algerian Desert called Bou Bernous, at an elevation of 378 metres (1,240 ft) above sea level,[18] and only Death Valley, California rivals it.[19] Other hot spots in Algeria such as Adrar, Timimoun, In Salah, Ouallene, Aoulef, Reggane with an elevation between 200 and 400 metres (660 and 1,310 ft) above sea level get slightly lower summer average highs, around 46 °C or 114.8 °F during the hottest months of the year. Salah, well known in Algeria for its extreme heat, has average high temperatures of 43.8 °C or 110.8 °F, 46.4 °C or 115.5 °F, 45.5 °C or 113.9 °F and 41.9 °C or 107.4 °F in June, July, August and September respectively. There are even hotter spots in the Sahara, but they are located in extremely remote areas, especially in the Azalai, lying in northern Mali. The major part of the desert experiences around three to five months when the average high strictly[clarification needed] exceeds 40 °C or 104 °F; while in the southern central part of the desert, there are up to six or seven months when the average high temperature strictly[clarification needed] exceeds 40 °C or 104 °F. Some examples of this are Bilma, Niger and Faya-Largeau, Chad. The annual average daily temperature exceeds 20 °C or 68 °F everywhere and can approach 30 °C or 86 °F in the hottest regions year-round. However, most of the desert has a value in excess of 25 °C or 77 °F.

Sand and ground temperatures are even more extreme. During daytime, the sand temperature is extremely high: it can easily reach 80 °C or 176 °F or more.[20] A sand temperature of 83.5 °C (182.3 °F) has been recorded in Port Sudan.[20] Ground temperatures of 72 °C or 161.6 °F have been recorded in the Adrar of Mauritania and a value of 75 °C (167 °F) has been measured in Borkou, northern Chad.[20]

Due to lack of cloud cover and very low humidity, the desert usually has high diurnal temperature variations between days and nights. However, it is a myth that the nights are especially cold after extremely hot days in the Sahara.[citation needed] On average, nighttime temperatures tend to be 13–20 °C (23–36 °F) cooler than in the daytime. The smallest variations are found along the coastal regions due to high humidity and are often even lower than a 10 °C or 18 °F difference, while the largest variations are found in inland desert areas where the humidity is the lowest, mainly in the southern Sahara. Still, it is true that winter nights can be cold, as it can drop to the freezing point and even below, especially in high-elevation areas.[clarification needed] The frequency of subfreezing winter nights in the Sahara is strongly influenced by the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), with warmer winter temperatures during negative NAO events and cooler winters with more frosts when the NAO is positive.[21] This is because the weaker clockwise flow around the eastern side of the subtropical anticyclone during negative NAO winters, although too dry to produce more than negligible precipitation, does reduce the flow of dry, cold air from higher latitudes of Eurasia into the Sahara significantly.[22]

Precipitation

The average annual rainfall ranges from very low in the northern and southern fringes of the desert to nearly non-existent over the central and the eastern part. The thin northern fringe of the desert receives more winter cloudiness and rainfall due to the arrival of low pressure systems over the Mediterranean Sea along the polar front, although very attenuated by the rain shadow effects of the mountains and the annual average rainfall ranges from 100 millimetres (4 in) to 250 millimetres (10 in). For example, Biskra, Algeria, and Ouarzazate, Morocco, are found in this zone. The southern fringe of the desert along the border with the Sahel receives summer cloudiness and rainfall due to the arrival of the Intertropical Convergence Zone from the south and the annual average rainfall ranges from 100 millimetres (4 in) to 250 millimetres (10 in). For example, Timbuktu, Mali and Agadez, Niger are found in this zone. The vast central hyper-arid core of the desert is virtually never affected by northerly or southerly atmospheric disturbances and permanently remains under the influence of the strongest anticyclonic weather regime, and the annual average rainfall can drop to less than 1 millimetre (0.04 in). In fact, most of the Sahara receives less than 20 millimetres (0.8 in). Of the 9,000,000 square kilometres (3,500,000 sq mi) of desert land in the Sahara, an area of about 2,800,000 square kilometres (1,100,000 sq mi) (about 31% of the total area) receives an annual average rainfall amount of 10 millimetres (0.4 in) or less, while some 1,500,000 square kilometres (580,000 sq mi) (about 17% of the total area) receives an average of 5 millimetres (0.2 in) or less.[23] The annual average rainfall is virtually zero over a wide area of some 1,000,000 square kilometres (390,000 sq mi) in the eastern Sahara comprising deserts of: Libya, Egypt and Sudan (Tazirbu, Kufra, Dakhla, Kharga, Farafra, Siwa, Asyut, Sohag, Luxor, Aswan, Abu Simbel, Wadi Halfa) where the long-term mean approximates 0.5 millimetres (0.02 in) per year.[23] Rainfall is very unreliable and erratic in the Sahara as it may vary considerably year by year. In full contrast to the negligible annual rainfall amounts, the annual rates of potential evaporation are extraordinarily high, roughly ranging from 2,500 millimetres (100 in) per year to more than 6,000 millimetres (240 in) per year in the whole desert.[24] Nowhere else on Earth has air been found as dry and evaporative as in the Sahara region. However, at least two instances of snowfall have been recorded in Sahara, in February 1979 and December 2016, both in the town of Ain Sefra.[25]

Desertification and prehistoric climate

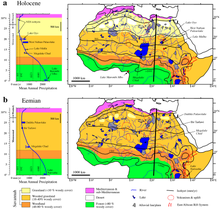

Vegetation and water bodies in the Eemian (bottom) and early Holocene (top)

One theory for the formation of the Sahara is that the monsoon in Northern Africa was weakened because of glaciation during the Quaternary period, starting two or three million years ago. Another theory is that the monsoon was weakened when the ancient Tethys Sea dried up during the Tortonian period around 7 million years.[26]

The climate of the Sahara has undergone enormous variations between wet and dry over the last few hundred thousand years,[27] believed to be caused by long-term changes in the North African climate cycle that alters the path of the North African Monsoon – usually southward. The cycle is caused by a 41,000-year cycle in which the tilt of the earth changes between 22° and 24.5°.[23] At present, we are in a dry period, but it is expected that the Sahara will become green again in 15,000 years. When the North African monsoon is at its strongest, annual precipitation and subsequent vegetation in the Sahara region increase, resulting in conditions commonly referred to as the «green Sahara». For a relatively weak North African monsoon, the opposite is true, with decreased annual precipitation and less vegetation resulting in a phase of the Sahara climate cycle known as the «desert Sahara».[28]

The idea that changes in insolation (solar heating) caused by long-term changes in Earth’s orbit are a controlling factor for the long-term variations in the strength of monsoon patterns across the globe was first suggested by Rudolf Spitaler in the late nineteenth century,[29] The hypothesis was later formally proposed and tested by the meteorologist John Kutzbach in 1981.[30] Kutzbach’s ideas about the impacts of insolation on global monsoonal patterns have become widely accepted today as the underlying driver of long-term monsoonal cycles. Kutzbach never formally named his hypothesis and as such it is referred to here as the «Orbital Monsoon Hypothesis» as suggested by Ruddiman in 2001.[29]

During the last glacial period, the Sahara was much larger than it is today, extending south beyond its current boundaries.[31] The end of the glacial period brought more rain to the Sahara, from about 8000 BCE to 6000 BCE, perhaps because of low pressure areas over the collapsing ice sheets to the north.[32] Once the ice sheets were gone, the northern Sahara dried out. In the southern Sahara, the drying trend was initially counteracted by the monsoon, which brought rain further north than it does today. By around 4200 BCE, however, the monsoon retreated south to approximately where it is today,[33] leading to the gradual desertification of the Sahara.[34] The Sahara is now as dry as it was about 13,000 years ago.[27]

Lake Chad is the remnant of a former inland sea, paleolake Mega-Chad, which existed during the African humid period. At its largest extent, sometime before 5000 BCE, Lake Mega-Chad was the largest of four Saharan paleolakes, and is estimated to have covered an area of 350,000 km2.[35]

The Sahara pump theory describes this cycle. During periods of a wet or «Green Sahara», the Sahara becomes a savanna grassland and various flora and fauna become more common. Following inter-pluvial arid periods, the Sahara area then reverts to desert conditions and the flora and fauna are forced to retreat northwards to the Atlas Mountains, southwards into West Africa, or eastwards into the Nile Valley. This separates populations of some of the species in areas with different climates, forcing them to adapt, possibly giving rise to allopatric speciation.

The Great Green Wall, participating countries and Sahel. In September 2020, it was reported that the GGW had only covered 4% of the planned area.[36]

It is also proposed that humans accelerated the drying-out period from 6000 to 2500 BCE by pastoralists overgrazing available grassland.[37]

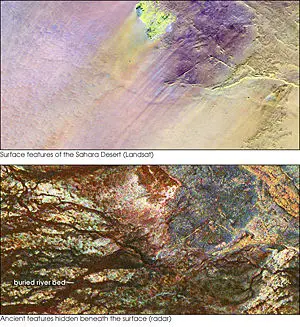

Evidence for cycles

The growth of speleothems (which requires rainwater) was detected in Hol-Zakh, Ashalim, Even-Sid, Ma’ale-ha-Meyshar, Ktora Cracks, Nagev Tzavoa Cave, and elsewhere, and has allowed tracking of prehistoric rainfall. The Red Sea coastal route was extremely arid before 140 and after 115 kya (thousands of years ago). Slightly wetter conditions appear at 90–87 kya, but it still was just one tenth the rainfall around 125 kya. In the southern Negev Desert speleothems did not grow between 185 and 140 kya (MIS 6), 110–90 (MIS 5.4–5.2), nor after 85 kya nor during most of the interglacial period (MIS 5.1), the glacial period and Holocene. This suggests that the southern Negev was arid-to-hyper-arid in these periods.[38]

During the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) the Sahara desert was more extensive than it is now with the extent of the tropical forests being greatly reduced,[39] and the lower temperatures reduced the strength of the Hadley Cell. This is a climate cell which causes rising tropical air of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) to bring rain to the tropics, while dry descending air, at about 20 degrees north, flows back to the equator and brings desert conditions to this region. It is associated with high rates of wind-blown mineral dust, and these dust levels are found as expected in marine cores from the north tropical Atlantic. But around 12,500 BCE the amount of dust in the cores in the Bølling/Allerød phase suddenly plummets and shows a period of much wetter conditions in the Sahara, indicating a Dansgaard-Oeschger (DO) event (a sudden warming followed by a slower cooling of the climate). The moister Saharan conditions had begun about 12,500 BCE, with the extension of the ITCZ northward in the northern hemisphere summer, bringing moist wet conditions and a savanna climate to the Sahara, which (apart from a short dry spell associated with the Younger Dryas) peaked during the Holocene thermal maximum climatic phase at 4000 BCE when mid-latitude temperatures seem to have been between 2 and 3 degrees warmer than in the recent past. Analysis of Nile River deposited sediments in the delta also shows this period had a higher proportion of sediments coming from the Blue Nile, suggesting higher rainfall also in the Ethiopian Highlands. This was caused principally by a stronger monsoonal circulation throughout the sub-tropical regions, affecting India, Arabia and the Sahara.[citation needed] Lake Victoria only recently became the source of the White Nile and dried out almost completely around 15 kya.[40]

The sudden subsequent movement of the ITCZ southwards with a Heinrich event (a sudden cooling followed by a slower warming), linked to changes with the El Niño-Southern Oscillation cycle, led to a rapid drying out of the Saharan and Arabian regions, which quickly became desert. This is linked to a marked decline in the scale of the Nile floods between 2700 and 2100 BCE.[41]

Ecoregions

The major topographic features of the Saharan region

The Sahara comprises several distinct ecoregions. With their variations in temperature, rainfall, elevation, and soil, these regions harbor distinct communities of plants and animals.

- The Atlantic coastal desert is a narrow strip along the Atlantic coast where fog generated offshore by the cool Canary Current provides sufficient moisture to sustain a variety of lichens, succulents, and shrubs. It covers an area of 39,900 square kilometers (15,400 sq mi) in the south of Morocco and Mauritania.[42]

- The North Saharan steppe and woodlands is along the northern desert, next to the Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub ecoregions of the northern Maghreb and Cyrenaica. Winter rains sustain shrublands and dry woodlands that form a transition between the Mediterranean climate regions to the north and the hyper-arid Sahara proper to the south. It covers 1,675,300 square kilometers (646,840 sq mi) in Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia.[43]

- The Sahara Desert ecoregion covers the hyper-arid central portion of the Sahara where rainfall is minimal and sporadic. Vegetation is rare, and this ecoregion consists mostly of sand dunes (erg, chech, raoui), stone plateaus (hamadas), gravel plains (reg), dry valleys (wadis), and salt flats. It covers 4,639,900 square kilometres (1,791,500 sq mi) of: Algeria, Chad, Egypt, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Sudan.[11]

- The South Saharan steppe and woodlands ecoregion is a narrow band running east and west between the hyper-arid Sahara and the Sahel savannas to the south. Movements of the equatorial Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) bring summer rains during July and August which average 100 to 200 mm (4 to 8 in) but vary greatly from year to year. These rains sustain summer pastures of grasses and herbs, with dry woodlands and shrublands along seasonal watercourses. This ecoregion covers 1,101,700 square kilometres (425,400 sq mi) in Algeria, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Sudan.[44]

- In the West Saharan montane xeric woodlands, several volcanic highlands provide a cooler, moister environment that supports Saharo-Mediterranean woodlands and shrublands. The ecoregion covers 258,100 square kilometres (99,650 sq mi), mostly in the Tassili n’Ajjer of Algeria, with smaller enclaves in the Aïr of Niger, the Adrar Plateau of Mauritania, and the Adrar des Iforas of Mali and Algeria.[45]

- The Tibesti-Jebel Uweinat montane xeric woodlands ecoregion consists of the Tibesti and Jebel Uweinat highlands. Higher and more regular rainfall and cooler temperatures support woodlands and shrublands of date palm, acacias, myrtle, oleander, tamarix, and several rare and endemic plants. The ecoregion covers 82,200 square kilometres (31,700 sq mi) in the Tibesti of Chad and Libya, and Jebel Uweinat on the border of Egypt, Libya, and Sudan.[46]

- The Saharan halophytics is an area of seasonally flooded saline depressions which is home to halophytic (salt-adapted) plant communities. The Saharan halophytics cover 54,000 square kilometres (21,000 sq mi) including: the Qattara and Siwa depressions in northern Egypt, the Tunisian salt lakes of central Tunisia, Chott Melghir in Algeria, and smaller areas of Algeria, Mauritania, and the southern part of Morocco.[47]

- The Tanezrouft is one of the Sahara’s most arid regions, with no vegetation and very little life. A barren, flat gravel plain, it extends south of Reggane in Algeria towards the Adrar des Ifoghas highlands in northern Mali.

Flora and fauna

The flora of the Sahara is highly diversified based on the bio-geographical characteristics of this vast desert. Floristically, the Sahara has three zones based on the amount of rainfall received – the Northern (Mediterranean), Central and Southern Zones. There are two transitional zones – the Mediterranean-Sahara transition and the Sahel transition zone.[48]

The Saharan flora comprises around 2800 species of vascular plants. Approximately a quarter of these are endemic. About half of these species are common to the flora of the Arabian deserts.[49]

The central Sahara is estimated to include five hundred species of plants, which is extremely low considering the huge extent of the area. Plants such as acacia trees, palms, succulents, spiny shrubs, and grasses have adapted to the arid conditions, by growing lower to avoid water loss by strong winds, by storing water in their thick stems to use it in dry periods, by having long roots that travel horizontally to reach the maximum area of water and to find any surface moisture, and by having small thick leaves or needles to prevent water loss by evapotranspiration. Plant leaves may dry out totally and then recover.

Several species of fox live in the Sahara including: the fennec fox, pale fox and Rüppell’s fox. The addax, a large white antelope, can go nearly a year in the desert without drinking. The dorcas gazelle is a north African gazelle that can also go for a long time without water. Other notable gazelles include the rhim gazelle and dama gazelle.

The Saharan cheetah (northwest African cheetah) lives in Algeria, Togo, Niger, Mali, Benin, and Burkina Faso. There remain fewer than 250 mature cheetahs, which are very cautious, fleeing any human presence. The cheetah avoids the sun from April to October, seeking the shelter of shrubs such as balanites and acacias. They are unusually pale.[50][51] The other cheetah subspecies (northeast African cheetah) lives in Chad, Sudan and the eastern region of Niger. However, it is currently extinct in the wild in Egypt and Libya. There are approximately 2000 mature individuals left in the wild.

Other animals include the monitor lizards, hyrax, sand vipers, and small populations of African wild dog,[52] in perhaps only 14 countries[53] and red-necked ostrich. Other animals exist in the Sahara (birds in particular) such as African silverbill and black-faced firefinch, among others. There are also small desert crocodiles in Mauritania and the Ennedi Plateau of Chad.[54]

The deathstalker scorpion can be 10 cm (3.9 in) long. Its venom contains large amounts of agitoxin and scyllatoxin and is very dangerous; however, a sting from this scorpion rarely kills a healthy adult. The Saharan silver ant is unique in that due to the extreme high temperatures of their habitat, and the threat of predators, the ants are active outside their nest for only about ten minutes per day.[55]

Dromedary camels and goats are the domesticated animals most commonly found in the Sahara. Because of its qualities of endurance and speed, the dromedary is the favourite animal used by nomads.

Human activities are more likely to affect the habitat in areas of permanent water (oases) or where water comes close to the surface. Here, the local pressure on natural resources can be intense. The remaining populations of large mammals have been greatly reduced by hunting for food and recreation. In recent years development projects have started in the deserts of Algeria and Tunisia using irrigated water pumped from underground aquifers. These schemes often lead to soil degradation and salinization.

Researchers from Hacettepe University have reported that Saharan soil may have bio-available iron and also some essential macro and micro nutrient elements suitable for use as fertilizer for growing wheat.[56]

History

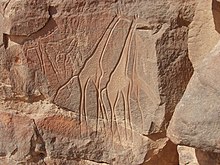

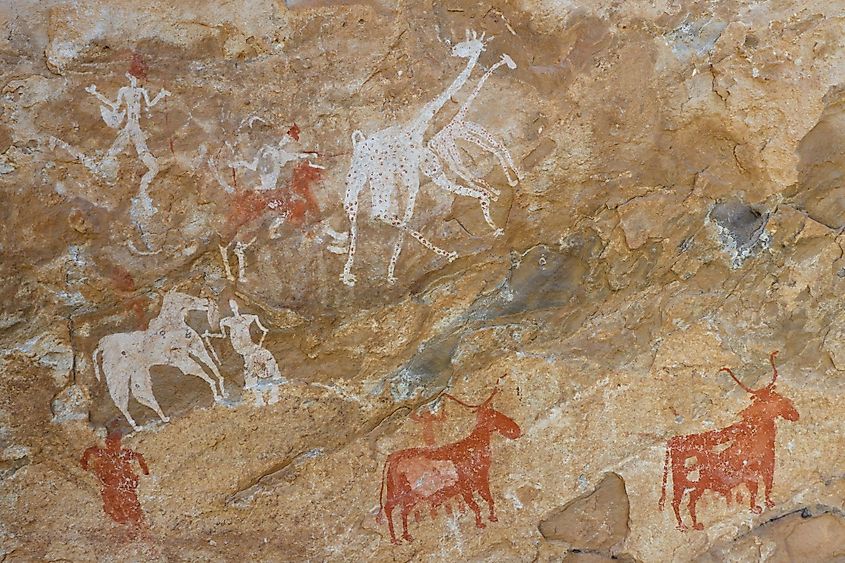

People lived on the edge of the desert thousands of years ago,[57] since the end of the last glacial period. In the Central Sahara, engraved and painted rock art were created perhaps as early as 10,000 years ago, spanning the Bubaline Period, Kel Essuf Period, Round Head Period, Pastoral Period, Caballine Period, and Cameline Period.[58] The Sahara was then a much wetter place than it is today. Over 30,000 petroglyphs of river animals such as crocodiles[59] survive, with half found in the Tassili n’Ajjer in southeast Algeria. Fossils of dinosaurs,[60] including Afrovenator, Jobaria and Ouranosaurus, have also been found here. The modern Sahara, though, is not lush in vegetation, except in the Nile Valley, at a few oases, and in the northern highlands, where Mediterranean plants such as the olive tree are found to grow. It was long believed that the region had been this way since about 1600 BCE, after shifts in Earth’s axis increased temperatures and decreased precipitation, which led to the abrupt desertification of North Africa about 5,400 years ago.[33]

Kiffians

The Kiffian culture is a prehistoric industry, or domain, that existed between 10,000 and 8,000 years ago in the Sahara, during the Neolithic Subpluvial. Human remains from this culture were found in 2000 at a site known as Gobero, located in Niger in the Ténéré Desert.[61] The site is known as the largest and earliest grave of Stone Age people in the Sahara desert.[62] The Kiffians were skilled hunters. Bones of many large savannah animals that were discovered in the same area suggest that they lived on the shores of a lake that was present during the Holocene Wet Phase, a period when the Sahara was verdant and wet.[62] The Kiffian people were tall, standing over six feet in height.[61] Craniometric analysis indicates that this early Holocene population was closely related to the Late Pleistocene Iberomaurusians and early Holocene Capsians of the Maghreb, as well as mid-Holocene Mechta groups.[63] Traces of the Kiffian culture do not exist after 8,000 years ago, as the Sahara went through a dry period for the next thousand years.[64] After this time, the Tenerian culture colonized the area.

Tenerians

Gobero was discovered in 2000 during an archaeological expedition led by Paul Sereno, which sought dinosaur remains. Two distinct prehistoric cultures were discovered at the site: the early Holocene Kiffian culture, and the middle Holocene Tenerian culture. The post-Kiffian desiccation lasted until around 4600 BCE, when the earliest artefacts associated with the Tenerians have been dated to. Some 200 skeletons have been discovered at Gobero. The Tenerians were considerably shorter in height and less robust than the earlier Kiffians. Craniometric analysis also indicates that they were osteologically distinct. The Kiffian skulls are akin to those of the Late Pleistocene Iberomaurusians, early Holocene Capsians, and mid-Holocene Mechta groups, whereas the Tenerian crania are more like those of Mediterranean groups.[65][66] Graves show that the Tenerians observed spiritual traditions, as they were buried with artifacts such as jewelry made of hippo tusks and clay pots. The most interesting find is a triple burial, dated to 5300 years ago, of an adult female and two children, estimated through their teeth as being five and eight years old, hugging each other. Pollen residue indicates they were buried on a bed of flowers. The three are assumed to have died within 24 hours of each other, but as their skeletons hold no apparent trauma (they did not die violently) and they have been buried so elaborately – unlikely if they had died of a plague – the cause of their deaths is a mystery.

Tashwinat Mummy

Uan Muhuggiag appears to have been inhabited from at least the 6th millennium BCE to about 2700 BCE, although not necessarily continuously.[67] The most noteworthy find at Uan Muhuggiag is the well-preserved mummy of a young boy of approximately 2+1⁄2 years old. The child was in a fetal position, then embalmed, then placed in a sack made of antelope skin, which was insulated by a layer of leaves.[68] The boy’s organs were removed, as evidenced by incisions in his stomach and thorax, and an organic preservative was inserted to stop his body from decomposing.[69] An ostrich eggshell necklace was also found around his neck.[67] Radiocarbon dating determined the age of the mummy to be approximately 5600 years old, which makes it about 1000 years older than the earliest previously recorded mummy in ancient Egypt.[70] In 1958–59, an archaeological expedition led by Antonio Ascenzi conducted anthropological, radiological, histological and chemical analyses on the Uan Muhuggiag mummy. The team claimed that the mummy was a 30-month-old child of uncertain sex who possessed Negroid features (Note: «negroid» is derived from a disproven theory of biological race, and modern genetics has since rendered such terminology obsolete).[71][72] A long incision on the specimen’s abdominal wall also indicated that the body had been initially mummified by evisceration and later underwent natural desiccation.[73] A more recent publication referenced a laboratory examination of the cutaneous features of the child mummy in which the results verified that the child possessed a dark skin complexion.[74] One other individual, an adult, was found at Uan Muhuggiag, buried in a crouched position.[67] However, the body showed no evidence of evisceration or any other method of preservation. The body was estimated to date from about 7500 BP.[75]

Nubians

Beni Isguen, a holy city surrounded by thick walls in the Algerian Sahara

During the Neolithic Era, before the onset of desertification around 9500 BCE, the central Sudan had been a rich environment supporting a large population ranging across what is now barren desert, like the Wadi el-Qa’ab. By the 5th millennium BCE, the people who inhabited what is now called Nubia were full participants in the «agricultural revolution», living a settled lifestyle with domesticated plants and animals. Saharan rock art of cattle and herdsmen suggests the presence of a cattle cult like those found in Sudan and other pastoral societies in Africa today.[76] Megaliths found at Nabta Playa are overt examples of probably the world’s first known archaeoastronomy devices, predating Stonehenge by some 2,000 years.[77] This complexity, as observed at Nabta Playa, and as expressed by different levels of authority within the society there, likely formed the basis for the structure of both the Neolithic society at Nabta and the Old Kingdom of Egypt.[78]

Archaeological evidence has attested that population settlements occurred in Nubia as early as the Late Pleistocene era and from the 5th millennium BC onwards, whereas there is «no or scanty evidence» of human presence in the Egyptian Nile Valley during these periods, which may be due to problems in site preservation.[79]

Egyptians

By 6000 BCE predynastic Egyptians in the southwestern corner of Egypt were herding cattle and constructing large buildings. Subsistence in organized and permanent settlements in predynastic Egypt by the middle of the 6th millennium BCE centered predominantly on cereal and animal agriculture: cattle, goats, pigs and sheep. Metal objects replaced prior ones of stone. Tanning of animal skins, pottery and weaving were commonplace in this era also. There are indications of seasonal or only temporary occupation of the Al Fayyum in the 6th millennium BCE, with food activities centering on fishing, hunting and food-gathering. Stone arrowheads, knives and scrapers from the era are commonly found.[80] Burial items included pottery, jewelry, farming and hunting equipment, and assorted foods including dried meat and fruit. Burial in desert environments appears to enhance Egyptian preservation rites, and the dead were buried facing due west.[81] Several scholars have argued that the African origins of the Egyptian civilisation derived from pastoral communities which emerged in both the Egyptian and Sudanese regions of the Nile Valley in the fifth millennium BCE.[82]

By 3400 BCE, the Sahara was as dry as it is today, due to reduced precipitation and higher temperatures resulting from a shift in Earth’s orbit.[33] As a result of this aridification, it became a largely impenetrable barrier to humans, with the remaining settlements mainly being concentrated around the numerous oases that dot the landscape. Little trade or commerce is known to have passed through the interior in subsequent periods, the only major exception being the Nile Valley. The Nile, however, was impassable at several cataracts, making trade and contact by boat difficult.

Tichitt culture

In 4000 BCE, the start of sophisticated social structure (e.g., trade of cattle as valued assets) developed among herders amid the Pastoral Period of the Sahara.[83] Saharan pastoral culture (e.g., fields of tumuli, lustrous stone rings, axes) was intricate.[84] By 1800 BCE, Saharan pastoral culture expanded throughout the Saharan and Sahelian regions.[83] The initial stages of sophisticated social structure among Saharan herders served as the segue for the development of sophisticated hierarchies found in African settlements, such as Dhar Tichitt.[83] After migrating from the Central Sahara, Mande peoples established their civilization in the Tichitt region[85] of the Western Sahara[86] The Tichitt Tradition of eastern Mauritania dates from 2200 BCE[87][88] to 200 BCE.[89][90] Tichitt culture, at Dhar Néma, Dhar Tagant, Dhar Tichitt, and Dhar Walata, included a four-tiered hierarchal social structure, farming of cereals, metallurgy, numerous funerary tombs, and a rock art tradition[91] At Dhar Tichitt and Dhar Walata, pearl millet may have also been independently tamed amid the Neolithic.[92] The urban[86] Tichitt Tradition may have been the earliest large-scale, complexly organized society in West Africa,[93] and an early civilization of the Sahara,[85][87] which may have served as the segue for state formation in West Africa.[84]

As areas where the Tichitt cultural tradition were present, Dhar Tichitt and Dhar Walata were occupied more frequently than Dhar Néma.[93] Farming of crops (e.g., millet) may have been a feature of the Tichitt cultural tradition as early as 3rd millennium BCE in Dhar Tichitt.[93]

As part of a broader trend of iron metallurgy developed in the West African Sahel amid 1st millennium BCE, iron items (350 BCE – 100 CE) were found at Dhar Tagant, iron metalworking and/or items (800 BCE – 400 BCE) were found at Dia Shoma and Walaldé, and the iron remnants (760 BCE – 400 BCE) found at Bou Khzama and Djiganyai.[93] The iron materials that were found are evidence of iron metalworking at Dhar Tagant.[90] In the late period of the Tichitt Tradition at Dhar Néma, tamed pearl millet was used to temper the tuyeres of a oval-shaped low shaft furnace; this furnace was one out of 16 iron furnaces located on elevated ground.[89] Iron metallurgy may have developed before the second half of 1st millennium BCE, as indicated by pottery dated between 800 BCE and 200 BCE.[89] At Dhar Walata and Dhar Tichitt, copper was also used.[86]

After its decline in Mauritania, the Tichitt Tradition spread to the Middle Niger region (e.g., Méma, Macina, Dia Shoma, Jenne Jeno) of Mali where it developed into and persisted as Faïta Facies ceramics between 1300 BCE and 400 BCE among rammed earth architecture and iron metallurgy (which had developed after 900 BCE).[94] Thereafter, the Ghana Empire developed in the 1st millennium CE.[94]

Phoenicians

Azalai salt caravan. The French reported that the 1906 caravan numbered 20,000 camels.

The people of Phoenicia, who flourished from 1200 to 800 BCE, created a chain of settlements along the coast of North Africa and traded extensively with its inhabitants. This put them in contact with the people of ancient Libya, who were the ancestors of people who speak Berber languages in North Africa and the Sahara today.

The Libyco-Berber alphabet of the ancient Libyans of north Africa seems to have been based on Phoenician, and its descendant Tifinagh is still used today by the (Berber) Tuareg of the central Sahara.

The Periplus of the Phoenician navigator Hanno, who lived sometime in the 5th century BC, claims that he founded settlements along the Atlantic coast of Africa, possibly including the Western Sahara. The identification of the places discussed is controversial, and archeological confirmation is lacking.

Greeks

By 500 BCE, Greeks arrived in the desert. Greek traders spread along the eastern coast of the desert, establishing trading colonies along the Red Sea. The Carthaginians explored the Atlantic coast of the desert, but the turbulence of the waters and the lack of markets caused a lack of presence further south than modern Morocco. Centralized states thus surrounded the desert on the north and east; it remained outside the control of these states. Raids from the nomadic Berber people of the desert were of constant concern to those living on the edge of the desert.

Urban civilization

Market on the main square of Ghardaïa (1971)

An urban civilization, the Garamantes, arose around 500 BCE in the heart of the Sahara, in a valley that is now called the Wadi al-Ajal in Fezzan, Libya.[27] The Garamantes achieved this development by digging tunnels far into the mountains flanking the valley to tap fossil water and bring it to their fields. The Garamantes grew populous and strong, conquering their neighbors and capturing many slaves (who were put to work extending the tunnels). The ancient Greeks and the Romans knew of the Garamantes and regarded them as uncivilized nomads. However, they traded with them, and a Roman bath has been found in the Garamantes’ capital of Garama. Archaeologists have found eight major towns and many other important settlements in the Garamantes’ territory. The Garamantes’ civilization eventually collapsed after they had depleted available water in the aquifers and could no longer sustain the effort to extend the tunnels further into the mountains.[95]

Between the first century BCE and the fourth century CE, several Roman expeditions into the Sahara were conducted by groups of military and commercial units of Romans.

Berbers

The Tuareg once controlled the central Sahara and its trade.

The Berber people occupied (and still occupy with Arabs) much of the Sahara. The Garamantes Berbers built a prosperous empire in the heart of the desert.[96] The Tuareg nomads continue to inhabit and move across wide Sahara surfaces to the present day.

Islamic and Arabic expansion

The Byzantine Empire ruled the northern shores of the Sahara from the 5th to the 7th centuries. After the Muslim conquest of Arabia, specifically the Arabian peninsula, the Muslim conquest of North Africa began in the mid-7th to early 8th centuries and Islamic influence expanded rapidly on the Sahara. By the end of 641 all of Egypt was in Muslim hands. Trade across the desert intensified, and a significant slave trade crossed the desert. It has been estimated that from the 10th to 19th centuries some 6,000 to 7,000 slaves were transported north each year.[97]

The Beni Ḥassān and other nomadic Arab tribes dominated the Sanhaja Berber tribes of the western Sahara after the Char Bouba war of the 17th century. As a result, Arabian culture and language came to dominate, and the Berber tribes underwent some Arabization.

Ottoman Turkish era

In the 16th century the northern fringe of the Sahara, such as coastal regencies in present-day Algeria and Tunisia, as well as some parts of present-day Libya, together with the semi-autonomous kingdom of Egypt, were occupied by the Ottoman Empire. From 1517 Egypt was a valued part of the Ottoman Empire, ownership of which provided the Ottomans with control over the Nile Valley, the east Mediterranean and North Africa. The benefit of the Ottoman Empire was the freedom of movement for citizens and goods. Traders exploited the Ottoman land routes to handle the spices, gold and silk from the East, manufactured goods from Europe, and the slave and gold traffic from Africa. Arabic continued as the local language and Islamic culture was much reinforced. The Sahel and southern Sahara regions were home to several independent states or to roaming Tuareg clans.

European colonialism

European colonialism in the Sahara began in the 19th century. France conquered the regency of Algiers from the Ottomans in 1830, and French rule spread south from French Algeria and eastwards from Senegal into the upper Niger to include present-day Algeria, Chad, Mali then French Sudan including Timbuktu (1893), Mauritania, Morocco (1912), Niger, and Tunisia (1881). By the beginning of the 20th century, the trans-Saharan trade had clearly declined because goods were moved through more modern and efficient means, such as airplanes, rather than across the desert.[98]

The French took advantage of long-standing animosity between the Chaamba Arabs and the Tuareg. The newly raised Méhariste camel corps were originally recruited mainly from the Chaamba nomadic tribe. In 1902, the French penetrated the Hoggar mountains and defeated Ahaggar Tuareg in the battle of Tit.

The French Colonial Empire was the dominant presence in the Sahara. It established regular air links from Toulouse (HQ of famed Aéropostale), to Oran and over the Hoggar to Timbuktu and West to Bamako and Dakar, as well as trans-Sahara bus services run by La Compagnie Transsaharienne (est. 1927).[99] A remarkable film shot by famous aviator Captain René Wauthier in 1933 documents the first crossing by a large truck convoy from Algiers to Tchad, across the Sahara.[100]

Egypt, under Muhammad Ali and his successors, conquered Nubia in 1820–22, founded Khartoum in 1823, and conquered Darfur in 1874. Egypt, including Sudan, became a British protectorate in 1882. Egypt and Britain lost control of the Sudan from 1882 to 1898 as a result of the Mahdist War. After its capture by British troops in 1898, the Sudan became an Anglo-Egyptian condominium.

Spain captured present-day Western Sahara after 1874, although Rio del Oro remained largely under Sahrawi influence. In 1912, Italy captured parts of what was to be named Libya from the Ottomans. To promote the Roman Catholic religion in the desert, Pope Pius IX appointed a delegate Apostolic of the Sahara and the Sudan in 1868; later in the 19th century his jurisdiction was reorganized into the Vicariate Apostolic of Sahara.

Breakup of the empires and afterwards

A natural rock arch in south western Libya

Egypt became independent of Britain in 1936, although the Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936 allowed Britain to keep troops in Egypt and to maintain the British-Egyptian condominium in the Sudan. British military forces were withdrawn in 1954.

Most of the Saharan states achieved independence after World War II: Libya in 1951; Morocco, Sudan, and Tunisia in 1956; Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger in 1960; and Algeria in 1962. Spain withdrew from Western Sahara in 1975, and it was partitioned between Mauritania and Morocco. Mauritania withdrew in 1979; Morocco continues to hold the territory (see Western Sahara conflict).[101]

Tuareg people in Mali rebelled several times during the 20th century before finally forcing the Malian armed forces to withdraw below the line demarcating Azawad from southern Mali during the 2012 rebellion.[102] Islamist rebels in the Sahara calling themselves al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb have stepped up their violence in recent years.[103]

In the post–World War II era, several mines and communities have developed to use the desert’s natural resources. These include large deposits of oil and natural gas in Algeria and Libya, and large deposits of phosphates in Morocco and Western Sahara.[104] Libya’s Great Man-Made River is the world’s largest irrigation project.[105] The project uses a pipeline system that pumps fossil water from the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System to cities in the populous Libyan northern Mediterranean coast including Tripoli and Benghazi.[106]

A number of Trans-African highways have been proposed across the Sahara, including the Cairo–Dakar Highway along the Atlantic coast, the Trans-Sahara Highway from Algiers on the Mediterranean to Kano in Nigeria, the Tripoli – Cape Town Highway from Tripoli in Libya to N’Djamena in Chad, and the Cairo – Cape Town Highway which follows the Nile. Each of these highways is partially complete, with significant gaps and unpaved sections.

People, culture, and languages

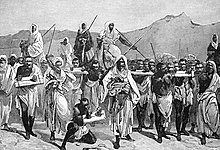

A 19th-century engraving of an Arab slave-trading caravan transporting black African slaves across the Sahara

The people of the Sahara are of various origins. Among them the Amazigh including the Tuareg, various Arabized Amaziɣ groups such as the Hassaniya-speaking Sahrawis, whose populations include the Znaga, a tribe whose name is a remnant of the pre-historic Zenaga language. Other major groups of people include the: Toubou, Nubians, Zaghawa, Kanuri, Hausa, Songhai, Beja, and Fula/Fulani (French: Peul; Fula: Fulɓe). The archaeological evidence from the Holocene period has shown that Nilo-Saharan speaking groups had populated the central and southern Sahara before the influx of Berber and Arabic speakers, around 1500 years ago, who now largely populate the Sahara in the modern era.[107]

Arabic dialects are the most widely spoken languages in the Sahara. Arabic, Berber and its variants now regrouped under the term Amazigh (which includes the Guanche language spoken by the original Berber inhabitants of the Canary Islands) and Beja languages are part of the Afro-Asiatic or Hamito-Semitic family.[citation needed] Unlike neighboring West Africa and the central governments of the states that comprise the Sahara, the French language bears little relevance to inter-personal discourse and commerce within the region, its people retaining staunch ethnic and political affiliations with Tuareg and Berber leaders and culture.[108] The legacy of the French colonial era administration is primarily manifested in the territorial reorganization enacted by the Third and Fourth republics, which engendered artificial political divisions within a hitherto isolated and porous region.[109] Diplomacy with local clients was conducted primarily in Arabic, which was the traditional language of bureaucratic affairs. Mediation of disputes and inter-agency communication was served by interpreters contracted by the French government, who, according to Keenan, «documented a space of intercultural mediation,» contributing much to preserving the indigenous cultural identities in the region.[110]

See also

- African humid period – Holocene climate period during which northern Africa was wetter than today

- Arid Lands Information Network

- List of deserts – List of deserts by continent

- List of deserts by area – List of the largest deserts in the world by area

- List of Saharan explorers

- Sahara Conservation Fund – International conservation organization

- Sahara Sea – Engineering project to flood parts of the Sahara Desert with sea water.

- Trans-Saharan slave trade – Slave trade

Notes

References

- ^ Cook, Kerry H.; Vizy, Edward K. (2015). «Detection and Analysis of an Amplified Warming of the Sahara Desert». Journal of Climate. 28 (16): 6560. Bibcode:2015JCli…28.6560C. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00230.1.

- ^ «Largest Desert in the World». Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ^ «Is the World Full or Empty?». Story Maps. Story Maps. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ «Sahara.» Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- ^ «English-Arabic online dictionary». Online.ectaco.co.uk. 28 December 2006. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ^ Wehr, Hans (1994). A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (Arabic-English) (4th ed.). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. p. 589. ISBN 978-0-87950-003-0.

- ^ al-Ba’labakkī, Rūḥī (2002). al-Mawrid: Qāmūs ‘Arabī-Inklīzī (in Arabic) (16th ed.). Beirut: Dār al-‘Ilm lil-Malāyīn. p. 689.

- ^ Chu, Jennifer (2 January 2019). «A «pacemaker» for North African climate». MIT News. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ Farr, Ben; Farr, Will M.; Cowan, Nicolas B.; Haggard, Hal M.; Robinson, Tyler (2018). «Exocartographer: A Bayesian Framework for Mapping Exoplanets in Reflected Light». The Astronomical Journal. 156 (4): 146. arXiv:1802.06805. Bibcode:2018AJ….156..146F. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aad775. S2CID 85443933.

- ^ Strahler, Arthur N. and Strahler, Alan H. (1987) Modern Physical Geography Third Edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-85064-0. p. 347

- ^ a b «Sahara desert». Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 30 December 2007.

- ^ Wickens, Gerald E. (1998) Ecophysiology of Economic Plants in Arid and Semi-Arid Lands. Springer, Berlin. ISBN 978-3-540-52171-6

- ^ a b Grove, A.T.; Nicole (2007) [1958]. «The Ancient Erg of Hausaland, and Similar Formations on the South Side of the Sahara». The Geographical Journal. 124 (4): 528–533. doi:10.2307/1790942. JSTOR 1790942.

- ^ a b Bisson, J. (2003). Mythes et réalités d’un désert convoité: le Sahara (in French). L’Harmattan.

- ^ a b Walton, K. (2007). The Arid Zones. Aldine. ASIN B008MR69VM.

- ^ «The 10 Largest Deserts In The World». WorldAtlas. 13 October 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ Griffiths, Ieuan L.I. (17 June 2013). The Atlas of African Affairs. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-85552-9.

- ^ a b Oliver, John E. (23 April 2008). Encyclopedia of World Climatology. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-3264-6.

- ^ Griffiths, John F.; Driscoll, Dennis M. (1982). Survey of Climatology. C.E. Merrill Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-675-09994-3.

- ^ a b c Nicholson, Sharon E. (27 October 2011). Dryland Climatology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-50024-1.

- ^ Visbeck, Martin H.; Hurrell, James W.; Polvani, Lorenzo; Cullen, Heidi M. (6 November 2001). «The North Atlantic Oscillation: Past, present, and future». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (23): 12876–12877. Bibcode:2001PNAS…9812876V. doi:10.1073/pnas.231391598. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 60791. PMID 11687629.

- ^ Hurrell, James W.; Kushnir, Yochanan; Ottersen, Geir; Visbeck, Martin (2003), «An Overview of the North Atlantic Oscillation», The North Atlantic Oscillation: Climatic Significance and Environmental Impact, American Geophysical Union (AGU), vol. 134, pp. 1–35, Bibcode:2003GMS…134….1H, doi:10.1029/134gm01, ISBN 978-1-118-66903-7, S2CID 13890714, retrieved 18 January 2022

- ^ a b c Houérou, Henry N. (10 December 2008). Bioclimatology and Biogeography of Africa. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-85192-9.

- ^ Brown, G.W. (17 September 2013). Desert Biology: Special Topics on the Physical and Biological Aspects of Arid Regions. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4832-1663-8.

- ^ «Snow falls in Sahara for first time in 37 years». CNN. 21 December 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ Yan, Qing; Contoux, Camille; Camille Li; Schuster, Mathieu; Ramstein, Gilles; Zhang, Zhongshi (17 September 2014). «Aridification of the Sahara desert caused by Tethys Sea shrinkage during the Late Miocene». Nature. 513 (7518): 401–404. Bibcode:2014Natur.513..401Z. doi:10.1038/nature13705. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 25230661. S2CID 205240355.

- ^ a b c White, Kevin; Mattingly, David J. (2006). «Ancient Lakes of the Sahara». American Scientist. 94 (1): 58–65. doi:10.1511/2006.57.983.

- ^ Foley, Jonathan A.; Coe, Michael T.; Scheffer, Marten; Wang, Guiling (1 October 2003). «Regime Shifts in the Sahara and Sahel: Interactions between Ecological and Climatic Systems in Northern Africa». Ecosystems. 6 (6): 524–539. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.533.5471. doi:10.1007/s10021-002-0227-0. S2CID 12698952.

- ^ a b Ruddiman, William F. (2001). Earth’s Climate: Past and Future. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-0-7167-3741-4.

- ^ Kutzbach, J.E. (2 October 1981). «Monsoon Climate of the Early Holocene: Climate Experiment with the Earth’s Orbital Parameters for 9000 Years Ago». Science. 214 (4516): 59–61. Bibcode:1981Sci…214…59K. doi:10.1126/science.214.4516.59. PMID 17802573. S2CID 10388125.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher, The Civilizations of Africa, University Press of Virginia, 2002.

- ^ Fezzan Project — Palaeoclimate and environment. Retrieved 15 March 2006. Archived 7 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Sahara’s Abrupt Desertification Started by Changes in Earth’s Orbit, Accelerated by Atmospheric and Vegetation Feedbacks.

- ^ Kröpelin, Stefan; et al. (2008). «Climate-Driven Ecosystem Succession in the Sahara: The Past 6000 Years» (PDF). Science. 320 (5877): 765–768. Bibcode:2008Sci…320..765K. doi:10.1126/science.1154913. PMID 18467583. S2CID 9045667. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Quade, J.; Dente, E.; Armon, M.; Ben Dor, Y.; Morin, E.; Adam, O.; Enzel, Y. (2018). «Megalakes in the Sahara? A Review». Quaternary Research. Cambridge University Press. 90 (2): 253–275. Bibcode:2018QuRes..90..253Q. doi:10.1017/qua.2018.46. S2CID 133889170.

- ^ Jonathan Watts (7 September 2020). «Africa’s Great Green Wall just 4% complete halfway through schedule». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Boissoneault, Lorraine (24 March 2017). «What Really Turned the Sahara Desert From a Green Oasis into a Wasteland?». Smithsonian. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ Vaks, Anton; Bar-Matthews, Miryam; Ayalon, Avner; Matthews, Alan; Halicz, Ludwik; Frumkin, Amos (2007). «Desert speleothems reveal climatic window for African exodus of early modern humans» (PDF). Geology. 35 (9): 831. Bibcode:2007Geo….35..831V. doi:10.1130/G23794A.1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011.

- ^ Adams, Jonathan. «Africa during the last 150,000 years». Environmental Sciences Division, ORNL Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 1 May 2006.

- ^ Stager, J.C.; Johnson, T.C. (2008). «The late Pleistocene desiccation of Lake Victoria and the origin of its endemic biota». Hydrobiologia. 596: 5–16. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9158-2. S2CID 42372016.

- ^ Burroughs, William J. (2007) «Climate Change in Prehistory: the end of the reign of chaos» (Cambridge University Press)

- ^ «Atlantic coastal desert». Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- ^ «North Saharan steppe and woodlands». Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- ^ «South Saharan steppe and woodlands». Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- ^ «West Saharan montane xeric woodlands». Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- ^ «Tibesti-Jebel Uweinat montane xeric woodlands». Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- ^ «Saharan halophytics». Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- ^ Mares, Michael A., ed. (1999). Encyclopedia of Deserts. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 490. ISBN 978-0-8061-3146-7.

- ^ Houérou, Henry N. (2008). Bioclimatology and Biogeography of Africa. Springer. p. 82. ISBN 978-3-540-85192-9.

- ^ «Rare cheetah captured on camera». BBC News. 24 February 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ^ Belbachir, F. (2008). «Acinonyx jubatus ssp. hecki«. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T221A13035738. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T221A13035738.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Woodroffe, R.; Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2020). «Lycaon pictus«. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T12436A166502262. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T12436A166502262.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Borrell, Brendan (19 August 2009). «Endangered in South Africa: Those Doggone Conservationists». Slate. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011.

- ^ «Desert-Adapted Crocs Found in Africa», National Geographic News, 18 June 2002

- ^ Wehner, R.; Marsh, A.C.; Wehner, S. (1992). «Desert ants on a thermal tightrope». Nature. 357 (6379): 586–87. Bibcode:1992Natur.357..586W. doi:10.1038/357586a0. S2CID 11774194.

- ^ Yücekutlu, Nihal; Terzioğlu, Serpil; Saydam, Cemal; Bildacı, Işık (2011). «Organic Farming By Using Saharan Soil: Could It Be An Alternative To Fertilizers?» (PDF). Hacettepe Journal of Biology and Chemistry. 39 (1): 29–38. Retrieved 23 March 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Discover Magazine, 2006-Oct.

- ^ Soukopova, Jitka (2017). «Central Saharan rock art: Considering the kettles and cupules». Journal of Arid Environments. 143: 10. Bibcode:2017JArEn.143…10S. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2016.12.011.

- ^ National Geographic News, 17 June 2006.

- ^ El-Said, Mohammed (29 January 2018). «Near-perfect fossils of Egyptian dinosaur discovered in the Sahara desert». Nature Middle East. doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2018.7.

- ^ a b «Stone Age Graveyard Reveals Lifestyles of A ‘Green Sahara’«. Science Daily. 15 August 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ a b Wilford, John Noble (14 August 2008). «Graves Found From Sahara’s Green Period». The New York Times. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ Sereno PC, Garcea EAA, Jousse H, Stojanowski CM, Saliège J-F, Maga A, et al. (2008). «Lakeside Cemeteries in the Sahara: 5000 Years of Holocene Population and Environmental Change». PLOS ONE. 3 (8): e2995. Bibcode:2008PLoSO…3.2995S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002995. PMC 2515196. PMID 18701936.

- ^ Schultz, Nora (14 August 2008). «Stone Age mass graves reveal green Sahara». New Scientist. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ Sereno PC, Garcea EA, Jousse H, Stojanowski CM, Saliège JF, Maga A, et al. (2008). «Lakeside Cemeteries in the Sahara: 5000 Years of Holocene Population and Environmental Change». PLOS ONE. 3 (8): e2995. Bibcode:2008PLoSO…3.2995S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002995. PMC 2515196. PMID 18701936.

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (14 August 2008). «In the Sahara, Stone Age graves from greener days». The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b c Mori, F. (1998). The Great Civilisations of the ancient Sahara: Neolithisation and the earliest evidence of anthropomorphic religions. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider. ISBN 88-7062-971-6.

- ^ Hooke, C. (Director), & Mosely, G. (Producer) (2003). Black Mummy of the Green Sahara (Discovery Channel).

- ^ Cockburn, A. (1980). Mummies, Disease and Ancient Cultures. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23020-9.

- ^ «Wan Muhuggiag». Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ Templeton, A. (2016). «Evolution and Notions of Human Race». In Losos, J.; Lenski, R. (eds.). How Evolution Shapes Our Lives: Essays on Biology and Society. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press. pp. 346–361. doi:10.2307/j.ctv7h0s6j.26

- ^ American Association of Physical Anthropologists (27 March 2019). «AAPA Statement on Race and Racism». American Association of Physical Anthropologists. Retrieved 27 Nov 2021

- ^ V. Giuffra; et al. (2010). «Antonio Ascenzi (1915–2000), a Pathologist devoted to Anthropology and Paleopathology» (PDF). Pathologica. 102 (1): 1–5. PMID 20731247. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 November 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ Soukopova, Jitka (16 January 2013). Round Heads: The Earliest Rock Paintings in the Sahara. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 19–24. ISBN 978-1-4438-4579-3.

- ^ Soukopova, J. (2012). Round Heads: The Earliest Rock Paintings in the Sahara. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-4007-1.

- ^ «History of Nubia». Anth.ucsb.edu. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ^ The History of Astronomy. PlanetQuest

- ^ Wendorf, Fred (1998) Late Neolithic megalithic structures at Nabta Playa.

- ^ Gatto, Maria C. «The Nubian Pastoral Culture as Link between Egypt and Africa: A View from the Archaeological Record».

- ^ Fayum, Qarunian (Fayum B, about 6000–5000 BCE?), Digital Egypt.

- ^ Predynastic (5,500–3,100 BCE), Tour Egypt.

- ^ Wengrow, David; Dee, Michael; Foster, Sarah; Stevenson, Alice; Ramsey, Christopher Bronk (March 2014). «Cultural convergence in the Neolithic of the Nile Valley: a prehistoric perspective on Egypt’s place in Africa». Antiquity. 88 (339): 95–111. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00050249. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 49229774.

- ^ a b c Brass, Michael. «The Emergence of Mobile Pastoral Elites during the Middle to Late Holocene in the Sahara». ResearchGate. Journal of African Archaeology.

- ^ a b Brass, Michael (2007). «Reconsidering the emergence of social complexity in early Saharan pastoral societies, 5000 – 2500 B.C.» Sahara (Segrate, Italy). Sahara (Segrate). 18: 7–22. PMC 3786551. PMID 24089595.

- ^ a b Abd-El-Moniem, Hamdi Abbas Ahmed. «A New Recording of Mauritanian Rock Art» (PDF). University College London.

- ^ a b c Kea, Ray. «Expansions and Contractions: World-Historical Change And The Western Sudan World-System (1200/1000 B.C. — 1200/1250 A.D.)». ResearchGate. Journal of World-Systems Research.

- ^ a b McDougall, E. Ann (2019). «Saharan Peoples and Societies». Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.285. ISBN 9780190277734.

- ^ Holl, Augustin F.C. (2009). «Coping with uncertainty: Neolithic life in the Dhar Tichitt-Walata, Mauritania, (ca. 4000–2300 BP)». Comptes Rendus Geoscience. 341 (8–9): 703–712. Bibcode:2009CRGeo.341..703H. doi:10.1016/j.crte.2009.04.005.

- ^ a b c MacDonald, K.; Vernet, R. (2007). Early domesticated pearl millet in Dhar Nema (Mauritania): evidence of crop processing waste as ceramic temper. Netherlands: Barkhuis. pp. 71–76. ISBN 9789077922309.

- ^ a b Kay, Andrea U. (2019). «Diversification, Intensification and Specialization: Changing Land Use in Western Africa from 1800 BC to AD 1500». Journal of World Prehistory. 32 (2): 179–228. doi:10.1007/s10963-019-09131-2. hdl:10261/181848. S2CID 134223231.

- ^ Sterry, Martin; Mattingly, David J. (26 March 2020). Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. p. 318. ISBN 9781108494441.

- ^ Champion, Louis; et al. (2021). «Agricultural diversification in West Africa: an archaeobotanical study of the site of Sadia (Dogon Country, Mali)». Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences. 13 (4): 60. doi:10.1007/s12520-021-01293-5. PMC 7937602. PMID 33758626.

- ^ a b c d MacDonald, Kevin C.; Vernet, Robert; Martinon-Torres, Marcos; Fuller, Dorian Q. «Dhar Néma: From early agriculture to metallurgy in southeastern Mauritania». ResearchGate. Azania Archaeological Research in Africa.

- ^ a b MacDonald, K.C. «Betwixt Tichitt and the IND: the pottery of the Faita Facies, Tichitt Tradition». Dokumen. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa.

- ^ Keys, David (2004). «Kingdom of the Sands». Archaeology. Vol. 57, no. 2.

- ^ Mattingly et al. (2003). Archaeology of Fazzan, Volume 1

- ^ Fage, J.D. (2001) A History of Africa. Routledge, 4th ed. ISBN 0-415-25248-2. p. 256

- ^ Trans-Saharan Africa in World History, Ch. 6, Ralph Austin

- ^ «Wauthier Bréard 1933» (in French). Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Wauthier, René. «Reconnaissance saharienne». French Cinema Archives (in French). Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ «Algeria recalls envoy to Morocco in row over Western Sahara». Al-Jazeera. 18 July 2021.

- ^ «Mali Tuareg rebels declare independence in the north». BBC News. 6 April 2012.

- ^ «Al-Qaeda in North Africa appoints new leader to replace Droukdel». France 24. 22 November 2020.

- ^ «The Desert Rock That Feeds the World». The Atlantic. 29 November 2016.

- ^ «Libya’s Qaddafi taps ‘fossil water’ to irrigate desert farms». CSMonitor.com. 23 August 2010.

- ^ Moutaz Ali (2017). «The Eighth Wonder of the World?». Quantara.de.

- ^ Drake, Nick A.; Blench, Roger M.; Armitage, Simon J.; Bristow, Charlie S.; White, Kevin H. (11 January 2011). «Ancient watercourses and biogeography of the Sahara explain the peopling of the desert». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (2): 458–462. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108..458D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012231108. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 3021035. PMID 21187416.

- ^ Jane E. Goodman (2010) [2005]). Berber Culture on the World Stage: From Village to Video. Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-253-21784-4 pp. 49–68

- ^ Ralph A. Austen. Trans-Saharan Africa in World History. Oxford University Press, 2010. ISBN 0-19-979883-4

- ^ Jeremy Keenan, ed. (2013). The Sahara: Past, Present and Future. Routledge, ISBN 1-317-97001-2

Bibliography

- Brett, Michael; Prentess, Elizabeth (1996). The Berbers. Blackwell Publishers.

- Bulliet, Richard W. (1975). The Camel and the Wheel. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674091306. Republished with a new preface Columbia University Press, 1990.

- Gearon, Eamonn (2011). The Sahara: A Cultural History. Signal Books (UK), Oxford University Press (US).

- Julien, Charles-Andre (1970). History of North Africa: From the Arab Conquest to 1830. Praeger.

- Kennedy, Hugh (1996). Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of al-Andalus. Longman.

- Laroui, Abdallah Laroui (1977). The History of the Maghrib: An Interpretive Essay. Princeton.

- Scott, Chris (2005). Sahara Overland. Trailblazer Guides.

- Wade, Lizzie (2015). «Drones and Satellites Spot Lost Civilizations in Unlikely Places». Science. doi:10.1126/science.aaa7864.

External links

- About Sahara subsurface hydrology and planned usage of the aquifers

- Heawood, Edward; Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). «Sahara» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). pp. 1004–1008.

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions. - Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

The Sahara Desert is the world’s largest hot desert, located in North Africa.

The Sahara covers large parts of Algeria, Chad, Egypt, Libya, Mauritania , Mali, Morocco, Niger, Western Sahara, Sudan and Tunisia.

Its surface area of 9,200,000 square kilometers (3,600,000 square miles) including the Libyan Desert and covers about 1/4 of the African continent. It is comparable to the respective land areas of China or the United States.

The Sahara is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean on the western edge, the Atlas Mountains and the Mediterranean Sea to the north, the Red Sea on the east, and the Sudan and the valley of the Niger River on the south.

The Sahara has one of the harshest climates in the world.

The Sahara is the world’s hottest desert.

The Sahara used to be a lush region with many plants and animals. It began to dry up around 4000 years ago due to a gradual change in the tilt of the Earth’s orbit.Earth’s obliquity oscillates between 22.1 and 24.5 degrees on a 41,000-year cycle. It is currently 23.44 degrees and decreasing.

The Sahara Desert is made up of sand dunes, sand seas, gravel plains, stone plateaus, salt flats, dry valleys, mountains, rivers, streams, and oases.

There is sparse grassland in some parts of the desert including the highlands and northern and southern parts of the desert.

The desert landforms of the Sahara are shaped by wind or by extremely rare rainfall and include sand dunes and dune fields or sand seas, stone plateaus, gravel plains, dry valleys, dry lakes and salt flats.Land formations change regularly.

Many of its sand dunes reach over 180 meters (590 feet) in height.

Several deeply dissected mountains and mountain ranges, many volcanic, rise from the desert.

Emi Koussi (huge extinct volcano), a peak in the Tibesti Mountains is 3,415 meters (11,204 feet) high and the highest point in the desert.

Snow may fall occasionally in some of the higher mountain ranges. On Feb. 18, 1979, low altitude areas of the Sahara desert recorded their first snowfall in living memory. Snow fell in spots in southern Algeria. It snowed in Algeria again in 2012.

Most of the rivers and streams in the Sahara desert are seasonal or intermittent, the main exception being the Nile River, which crosses the desert from its origins in central Africa to empty into the Mediterranean.

There are some 20 or more lakes in the Sahara.Most of these are saltwater lakes. Lake Chad is the only freshwater lake in the desert.

Some of the world’s largest supplies of underground water exist beneath the Sahara Desert, supporting about 90 major oases there.

Around two million people live in the Sahara Desert.

The people who live in the Sahara are mostly nomads. Nomads move from place to place.

Like all deserts, the Sahara harbors a relatively sparse community of wild plants, with the highest concentrations occurring along the northern and southern margins and near the oases and drainages.

It has imposed adaptations on the plants.

For instance, near wadis and oases, plants such as date palms, tamarisks and acacia put down long roots to reach life-sustaining water.

In the more arid areas, the seeds of flowering plants sprout quickly after a rain, putting down shallow roots, and completing their growing cycle and producing seeds in a matter of days, before the soil dries out. The new seeds may lie dormant in the dry soil for years, awaiting the next rainfall to repeat the cycle.

From the Mediterranean vegetation which covered the Sahara mountains before they became a desert, only laurel and cypress trees remain in the region near gueltas.

Across the central, most arid part of the Sahara, the plant community comprises perhaps 500 species, which is extremely low considering the huge extent of the area.

Date palm trees, introduced by Arabs, is requisite for the existence of humans in the oasis; dates are very energetic food, trunks are used to make beams, leaves are used to make baskets, ropes, mats and covers for huts,… its preserves fruit trees against the sun.

Camels are the main animal of the desert. They have a great capacity to resist heat and thirst. Even above 50 C° (122 F°), they can stay without drinking water for many days. The camel is the favourite animal used by nomads. The second favorite animal for nomads in the Sahara desert is goat.

Several species of fox live in the Sahara, including the fennec fox, pale fox and Rüppell’s fox.