| House music | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | Late 1970s, Chicago, Illinois, United States[9] |

| Typical instruments |

|

| Derivative forms |

|

| Subgenres | |

(complete list) |

|

| Regional scenes | |

|

|

| Other topics | |

|

House is a music genre characterized by a repetitive four-on-the-floor beat and a typical tempo of 120 beats per minute.[10] It was created by DJs and music producers from Chicago’s underground club culture in the early/mid 1980s, as DJs began altering disco songs to give them a more mechanical beat.[1]

House was pioneered by African American DJs and producers in Chicago such as Frankie Knuckles, Ron Hardy, Jesse Saunders, Chip E., Joe Smooth, Steve «Silk» Hurley, Farley «Jackmaster» Funk, Marshall Jefferson, Phuture, and others. House music expanded to other cities such as London, then New York City and became a worldwide phenomenon.[11]

House has a large effect on pop music, especially dance music. It was incorporated into works by major international artists including Whitney Houston, Janet Jackson, Madonna, Pet Shop Boys, and Kylie Minogue, and also produced many mainstream hits such as «Pump Up the Jam» by Technotronic, «French Kiss» by Lil Louis, «Show Me Love» by Robin S., and «Push the Feeling On» by the Nightcrawlers. Many house DJs also did and continue to do remixes for pop artists. House music has remained popular on radio and in clubs while retaining a foothold on the underground scenes across the globe.

Characteristics[edit]

A full house music track.

The TR-909 drum machine (top) and TB-303 synthesizer, instruments often used in house music

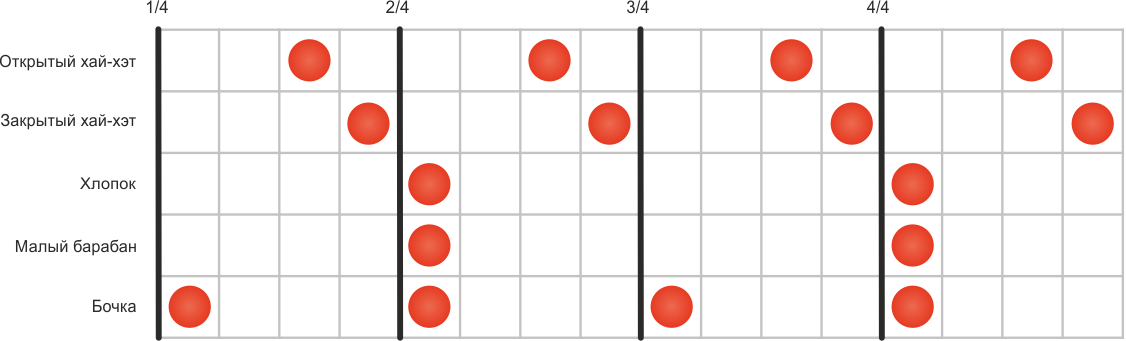

A house rhythm played on a Roland TR-909 drum machine, featuring a four-on-the-floor bass drum plus cymbal, claps, hi-hats and rimshots

In its most typical form, the genre is characterized by repetitive 4/4 rhythms including bass drums, off-beat hi-hats, snare drums, claps, and/or snaps at a tempo of between 115 and 125 beats per minute (bpm); synthesizer riffs; deep basslines; and often, but not necessarily, sung, spoken or sampled vocals. In house, the bass drum is usually sounded on beats one, two, three, and four, and the snare drum, claps, or other higher-pitched percussion on beats two and four. The drum beats in house music are almost always provided by an electronic drum machine, often a Roland TR-808, TR-909,[12] or a TR-707. Claps, shakers, snare drum, or hi-hat sounds are used to add syncopation.[13] One of the signature rhythm riffs, especially in early Chicago house, is built on the clave pattern.[14] Congas and bongos may be added for an African sound, or metallic percussion for a Latin feel.[13]

Sometimes, the drum sounds are «saturated» by boosting the gain to create a more aggressive edge.[13] One classic subgenre, acid house, is defined through the squelchy sounds created by the Roland TB-303 bass synthesizer. House music could be produced on «cheap and consumer-friendly electronic equipment» and used sound gear, which made it easier for independent labels and DJs to create tracks.[15] The electronic drum machines and other gear used by house DJs and producers were formerly considered «too cheap-sounding» by «proper» musicians.[16] House music producers typically use sampled instruments, rather than bringing session musicians into a recording studio.[17] Even though a key element of house production is layering sounds, such as drum machine beats, samples, synth basslines, and so on, the overall «texture…is relatively sparse».[18] Unlike pop songs, which emphasize higher-pitched sounds like melody, in house music, the lower-pitched bass register is most important.[18]

House tracks typically involve an intro, a chorus, various verse sections, a midsection, and a brief outro. Some tracks do not have a verse, taking a vocal part from the chorus and repeating the same cycle. House music tracks are often based on eight-bar sections which are repeated.[18] They are often built around bass-heavy loops or basslines produced by a synthesizer and/or around samples of disco, soul,[19] jazz-funk,[8] or funk[19] songs. DJs and producers creating a house track to be played in clubs may make a «seven or eight-minute 12-inch mix»; if the track is intended to be played on the radio, a «three-and-a-half-minute» radio edit is used.[20] House tracks build up slowly, by adding layers of sound and texture, and by increasing the volume.[18]

House tracks may have vocals like a pop song, but some are «completely minimal instrumental music».[18] If a house track does have vocals, the vocal lines may also be simple «words or phrases» that are repeated.[18]

Origins of the term «house»[edit]

House music pioneers Alan King, Robert Williams and Derrick Carter.

One book from 2009 states the name «house music» originated from a Chicago club called the Warehouse that was open from 1977 to 1982.[21] Clubbers to the Warehouse were primarily black, gay men,[22] who came to dance to music played by the club’s resident DJ, Frankie Knuckles, who fans refer to as the «godfather of house». Frankie began the trend of splicing together different records when he found that the records he had were not long enough to satisfy his audience of dancers.[23] After the Warehouse closed in 1983, eventually the crowds went to Knuckles’ new club, The Power House, later to be called The Power Plant,[21] and the club was renamed, yet again, into Music Box with Ron Hardy as the resident DJ.[24] The 1983 documentary, «House Music in Chicago», by filmmaker, Phil Ranstrom, captured opening night at The Power House, and stands as the only film or video to capture a young Frankie Knuckles in this early era, right after his departure from The Warehouse. [25][26][27][28]

In the Channel 4 documentary Pump Up the Volume, Knuckles remarks that the first time he heard the term «house music» was upon seeing «we play house music» on a sign in the window of a bar on Chicago’s South Side. One of the people in the car joked, «you know that’s the kind of music you play down at the Warehouse!»[29] In self-published statements, South-Side Chicago DJ Leonard «Remix» Rroy claimed he put such a sign in a tavern window because it was where he played music that one might find in one’s home; in his case, it referred to his mother’s soul and disco records, which he worked into his sets.[30]

Chicago house artist Farley «Jackmaster» Funk was quoted as saying, «In 1982, I was DJing at a club called The Playground and there was this kid named Leonard ‘Remix’ Rroy who was a DJ at a rival club called The Rink. He came over to my club one night, and into the DJ booth and said to me, ‘I’ve got the gimmick that’s gonna take all the people out of your club and into mine – it’s called House music.’ Now, where he got that name from or what made him think of it I don’t know, so the answer lies with him.»[31]

Chicago artist Chip E.’s 1985 song «It’s House» may also have helped to define this new form of electronic music.[32] However, Chip E. himself lends credence to the Knuckles association, claiming the name came from methods of labeling records at the Importes Etc. record store, where he worked in the early 1980s. Bins of music that DJ Knuckles played at the Warehouse nightclub were labelled «As Heard at the Warehouse» in the store, which was shortened to simply «House». Patrons later asked for new music for the bins, which Chip E. implies was a demand the shop tried to meet by stocking newer local club hits.[33]

In a 1986 interview, when Rocky Jones, the club DJ who ran Chicago-based DJ International Records, was asked about the «house» moniker, he did not mention Importes Etc., Frankie Knuckles, or the Warehouse by name. However, he agreed that «house» was a regional catch-all term for dance music, and that it was once synonymous with older disco music before it became a way to refer to «new» dance music.[34]

Larry Heard, a.k.a. «Mr. Fingers», claims that the term «house» came from DJs creating music in their house or at home using synthesizers and drum machines, such as the Roland TB-303,[35] Roland TR-808, and TR-909.[36] These synthesizers were used to create the acid house subgenre.[37] Juan Atkins, a pioneer of Detroit techno, claims the term «house» reflected the association of particular tracks with particular clubs and DJs, considered their «house» records.[38]

Dance style[edit]

At least three styles of dancing are associated with early house music: jacking, footwork and lofting.[39] These styles include a variety of techniques and sub-styles, including skating, stomping, vosho, pouting cat, and shuffle steps (also see Melbourne shuffle).[40][41] House music dancing styles can include movements from many other forms of dance, such as waacking, voguing, capoeira, jazz dance, Lindy Hop, tap dance, and even modern dance.[42][41] House dancing is associated with a complete freedom of expression.[43]

One of the primary elements in house dancing is «the jack» or «jacking» — a style created in the early days of Chicago house that left its trace in numerous record titles such as «Time to Jack» by Chip E. from the Jack Trax EP (1985), «Jack’n the House» (1985) by Farley «Jackmaster» Funk (1985) or «Jack Your Body» by Steve «Silk» Hurley (1986). It involves moving the torso forward and backward in a rippling motion matching the beat of the music, as if a wave were passing through it.[43]

Social and political aspects[edit]

Early house lyrics contained generally positive, uplifting messages, but spoke especially to those who were considered to be outsiders, especially African-Americans, Latinos, and the gay subculture. The house music dance scene was one of the most integrated and progressive spaces in the 1980s; the black and gay populations, as well as other minority groups, were able to dance together in a positive environment.[44]

House music DJs aimed to create a «dream world of emotions» with «stories, keywords and sounds», which helped to «glue» communities together.[15] Many house tracks encourage the audience to «release yourself» or «let yourself go», which is further encouraged by the continuous dancing, «incessant beat», and use of club drugs, which can create a trance-like effect on dancers.[15] Frankie Knuckles once said that the Warehouse club in Chicago was like «church for people who have fallen from grace». House record producer Marshall Jefferson compared it to «old-time religion in the way that people just get happy and screamin‘«.[43] The role of a house DJ has been compared to a «secular type of priest».[15]

Some house lyrics contained messages calling for equality, unity, and freedom of expression beyond racial or sexual differences (e.g. «Can You Feel It» by Fingers Inc., 1987, or «Follow Me» by Aly-Us, 1992). Later on in the 1990s, independently from the Chicago scene, the idea of Peace, Love, Unity & Respect (PLUR) became a widespread set of principles for the rave culture.[citation needed]

History[edit]

Influences and precursors[edit]

One of the main influences of house was disco, house music having been defined as a genre which «…picked up where disco left off in the late 1970’s.»[45][46] Like disco DJs, house DJs used a «slow mix» to «lin[k] records together» into a mix.[15] In the post-disco club culture during the early 1980s, DJs from the gay scene made their tracks «less pop-oriented», with a more mechanical, repetitive beat and deeper basslines, and many tracks were made without vocals, or with wordless melodies.[47] Disco became so popular by the late 1970s that record companies pushed even non-disco artists (R&B bands, for example) to produce disco songs. When the backlash against disco started, known as «Disco Demolition Night», dance music went from being produced by major label studios to being created by DJs in the underground club scene.[15]

While disco was associated with lush orchestration, with string orchestra, flutes and horn sections, various disco songs incorporated sounds produced with synthesizers and electronic drum machines, and some compositions were entirely electronic; examples include Italian composer Giorgio Moroder’s late 1970s productions such as Donna Summer’s hit single «I Feel Love» from 1977, Kraftwerk’s «‘The Man-Machine» album from 1978,[48] Cerrone’s «Supernature» (1977),[49] Yellow Magic Orchestra’s synth-disco-pop productions from Yellow Magic Orchestra (1978) or Solid State Survivor (1979),[50][51] and several early 1980s productions by hi-NRG groups like Lime, Trans-X and Bobby O.

Frankie Knuckles (pictured in 2012) played an important role in developing house music in Chicago during the 1980s.

Also important for the development of house were audio mixing and editing techniques earlier explored by disco, garage music and post-disco DJs, record producers, and audio engineers such as Walter Gibbons, Tom Moulton, Jim Burgess, Larry Levan, M & M, and others.

While most post-disco disc jockeys primarily stuck to playing their conventional ensemble and playlist of dance records, Frankie Knuckles and Ron Hardy, two influential DJs of house music, were known for their unusual and non-mainstream playlists and mixing. Knuckles was influenced by and worked with New York City club Paradise Garage resident Larry Levan. Knuckles, often credited as «the Godfather of House» and resident DJ at the Warehouse from 1977 to 1982, worked primarily with early disco music with a hint of new and different post-punk or post-disco music.[52] Knuckles started out as a disco DJ, but when he moved from New York City to Chicago, he changed from the typical disco mixing style of playing records one after another; instead, he mixed different songs together, including Philadelphia soul, New York club tracks, and Euro disco.[18] He also explored adding a drum machine and a reel-to-reel tape player so he could create new tracks, often with a boosted deep register and faster tempos. Knuckles said: «Kraftwerk were main components in the creation of house music in Chicago. Back in the early 80s, I mixed our 80s Philly sound with the electro beats of Kraftwerk and the Electronic body music bands of Europe.»[18][53]

Ron Hardy produced unconventional DIY mixtapes which he later played straight-on in the successor of the Warehouse, the Music Box (reopened and renamed in 1983 after Knuckles left). Like Frankie Knuckles, Hardy «combined certain sounds, remixing tracks with added synths and drum machines», all «refracted through the futurist lens of European music.»[16] Marshall Jefferson, who would later appear with the 1986 house classic «Move Your Body (The House Music Anthem)» (originally released on Trax Records), describes how he got involved in house music after hearing Ron Hardy’s music in the Music Box:

«I wasn’t even into dance music before I went to the Music Box […]. I was into rock and roll. We would get drunk and listen to rock and roll. We didn’t give a fuck, we were like ‘Disco Sucks!’ and all that. I hated dance music ‘cos I couldn’t dance. I thought dance music was kind of wimpy, until I heard it at like Music Box volume.»

— Marshall Jefferson[54]

A precursor to house music is the Colonel Abrams hit song «Trapped», which was produced by Richard James Burgess in 1984[55] and has been referred to as a proto-house track and a precursor to garage house.[56]

Rachel Cain, better known as Screamin’ Rachael, co-founder of the highly influential house label Trax Records, was previously involved in the burgeoning punk scene. Cain cites industrial music (another genre pioneered in Chicago) and post-punk record store Wax Trax! Records (later a record label) as an important connection between the ever-changing underground sounds of Chicago.

The electronic instrumentation and minimal arrangement of Charanjit Singh’s Synthesizing: Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat (1982), an album of Indian ragas performed in a disco style and anticipated the sounds of acid house music, but it is not known to have had any influence on the genre prior to the album’s rediscovery in the 21st century.[57][58][59] According to Hillegonda C. Rietveld, «elements of hip hop and rap can be found in contemporary house tracks», with hip hop acting as an «accent or inflection» that is inserted into the house sound.[15]

The constant bass drum in house music may have arisen from DJs experimenting with adding drum machines to their live mixes at clubs, underneath the records they were playing.[60]

1980s: Chicago house, acid house and deep house[edit]

In the early 1980s, Chicago radio jocks Hot Mix 5 from WBMX radio station (among them Farley «Jackmaster» Funk), and club DJs Ron Hardy and Frankie Knuckles played a range of styles of dance music, including older disco records (mostly Philly disco and Salsoul[61] tracks), electro funk tracks by artists such as Afrika Bambaataa,[8] newer Italo disco, Arthur Baker, and John Robie, and electronic pop.[1] Some DJs made and played their own edits of their favorite songs on reel-to-reel tape, and sometimes mixed in electronic effects, drum machines, synthesizers and other rhythmic electronic instrumentation.

The hypnotic electronic dance song «On and On», produced in 1984 by Chicago DJ Jesse Saunders and co-written by Vince Lawrence, had typical elements of the early house sound, such as the Roland TB-303 bass synthesizer and minimal vocals, as well as a Roland TR-808 drum machine and a Korg Poly-61 synthesizer. It also utilized the bassline from Player One’s disco record «Space Invaders» (1979).[62] «On and On» is sometimes cited as the «first house record»,[63][64] even though it was a remake of a Disco Bootleg «On and On» by Florida producer Mach. Other examples from around that time, such as J.M. Silk’s «Music is the Key» (1985), have also been referred to as the first house tracks.[65][66]

Starting in 1985 and 1986, more and more Chicago DJs began producing and releasing original compositions. These compositions used newly affordable electronic instruments and enhanced styles of disco and other dance music they already favored. These homegrown productions were played on Chicago radio stations and in local clubs catering mainly to Black, Mexican American, and gay audiences.[67][68][69][70][71][72] Subgenres of house, including deep house and acid house, quickly emerged and gained traction.[24]

Deep house’s origins can be traced to Chicago producer Mr. Fingers’s relatively jazzy, soulful recordings «Mystery of Love» (1985) and «Can You Feel It?» (1986).[74] According to author Richie Unterberger, it moved house music away from its «posthuman tendencies back towards the lush» soulful sound of early disco music.[75]

Acid house, a rougher and more abstract subgenre, arose from Chicago artists’ experiments with the squelchy sounds of the Roland TB-303 bass synthesizer that define the genre. Its origin on vinyl is generally cited as Phuture’s «Acid Tracks» (Trax Records, 1987). Phuture, a group founded by Nathan «DJ Pierre» Jones, Earl «Spanky» Smith Jr., and Herbert «Herb J» Jackson, is credited with having been the first to use the TB-303 in the house music context.[76] The group’s 12-minute «Acid Tracks» was recorded to tape and played by DJ Ron Hardy at the Music Box,[77] supposedly already by 1985.[78] Hardy once played it four times over the course of an evening until the crowd responded favorably.[79]

Club play of house tracks by pioneering Chicago DJs such as Ron Hardy and Lil Louis, local dance music record shops such as Importes Etc., State Street Records, Loop Records, Gramaphone Records and the popular Hot Mix 5 shows on radio station WBMX-FM helped popularize house music in Chicago. Later, visiting DJs and producers from Detroit fell into the genre. Trax Records and DJ International Records, Chicago labels with wider distribution, helped popularize house music inside and outside of Chicago.

The first major success of house music outside the U.S. is considered to be Farley «Jackmaster» Funk’s «Love Can’t Turn Around» (feat. Jesse Saunders and performed by Darryl Pandy), which peaked at #10 in the UK singles chart in 1986. Around that time, UK record labels started releasing house music by Chicago acts, but as the genre grew popular, the UK itself became one of the new hot spots for house, acid house and techno music, experiencing the so-called second summer of love between 1988 and 1989.[24]

Detroit and techno[edit]

In Detroit during the early and mid-1980s, a new kind of electronic dance music began to emerge around Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson, known as the Belleville Three. The artists fused eclectic, futuristic sounds into a signature Detroit dance sound that was a main influence for the later techno genre. Their music included strong influences from Chicago house, although the term «house» played a less important role in Detroit than in Chicago, and the term «techno» was established instead.[80] One of their most successful hits was a vocal house track named «Big Fun» by Inner City, a group produced by Kevin Saunderson, in 1988.

Another major and even earlier influence on the Detroit artists was electronic music in the tradition of Germany’s Kraftwerk.[81] Atkins had released electro music in that style with his group Cybotron as early as 1981. Cybotron’s best known songs are «Cosmic Cars» (1982) and «Clear» (1983); a 1984 release was titled «Techno City». In 1988, Atkins produced the track «Techno Music», which was featured on an influential compilation that was initially planned to be named «The House Sound of Detroit», but was renamed into «Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit» after Atkins’ song.[82]

The 1987 song «Strings of Life» by Derrick May (under the name Rhythm Is Rhythm) represented a darker, more intellectual strain of early Detroit electronic dance music. It is considered a classic in both the house and techno genre and shows the connection[83] and the «boundary between house and techno.»[84] It made way to what was later known as «techno» in the internationally known sense of the word, referring to a harder, faster, colder, more machine-driven and minimal sound than house, as played by Detroit’s Underground Resistance and Jeff Mills.

UK: Acid house, rave culture and the Second Summer of Love[edit]

A badge bearing a smiley, a symbol of the 1980s acid house scene in the UK[85]

With house music already important in the 1980s dance club scene, eventually house penetrated the UK singles chart. London DJ «Evil» Eddie Richards spun at dance parties as resident at the Clink Street club. Richards’ approach to house focuses on the deep basslines. Nicknamed the UK’s «Godfather of House», he and Clink co-residents Kid Batchelor and Mr. C played a key role in early UK house. House first charted in the UK in Wolverhampton following the success of the Northern Soul scene. The record generally credited as the first house hit in the UK was Farley «Jackmaster» Funk’s «Love Can’t Turn Around», which reached #10 in the UK singles chart in September 1986.[86]

In January 1987, Chicago DJ/artist Steve «Silk» Hurley’s «Jack Your Body» reached number one in the UK, showing it was possible for house music to achieve crossover success in the main singles chart. The same month also saw Raze enter the top 20 with «Jack the Groove», and several other house hits reached the top ten that year. Stock Aitken Waterman (SAW) expensively-produced productions for Mel and Kim, including the number-one hit «Respectable», added elements of house to their previous Europop sound. SAW session group Mirage scored top-ten hits with «Jack Mix II» and «Jack Mix IV», medleys of previous electro and Europop hits rearranged in a house music style. Key labels in the rise of house music in the UK included:[citation needed]

- Jack Trax, which specialized in licensing US club hits for the British market (and released an influential series of compilation albums)

- Rhythm King, which was set up as a hip hop label but also issued house records

- Jive Records’ Club Records imprint

In March 1987, the UK tour of influential US DJs such as Knuckles, Jefferson, Fingers Inc. (Heard), and Adonis on the DJ International Tour boosted house’s popularity in the UK. Following the success of MARRS’ «Pump Up The Volume» in October, from 1987 to 1989, UK acts such as The Beatmasters, Krush, Coldcut, Yazz, Bomb The Bass, S-Express, and Italy’s Black Box opened the doors to house music success on the UK charts. Early British house music quickly set itself apart from the original Chicago house sound. Many of the early hits were based on sample montage, and unlike the US soulful vocals, in UK house, rap was often used for vocals (far more than in the US), and humor and wit was an important element.[citation needed]

The second best-selling British single of 1988 was an acid house record, the Coldcut-produced «The Only Way Is Up» by Yazz.[87][88] One of the early club anthems, «Promised Land» by Joe Smooth, was covered and charted within a week by UK band The Style Council. Europeans embraced house, and began booking important American house DJs to play at the big clubs, such as Ministry of Sound, whose resident, Justin Berkmann brought in US pioneer Larry Levan.[89]

The house music club scene in cities such as Birmingham, Leeds, Sheffield, Wolverhampton, and London were provided with dance tracks by many underground pirate radio stations. Club DJs also brought in new house styles, which helped bolster this music genre. The earliest UK house and techno record labels, such as Warp Records and Network Records (formed out of Kool Kat records), helped introduce American and later Italian dance music to Britain. These labels also promoted UK dance music acts. By the end of the 1980s, UK DJs Jenö, Thomas, Markie and Garth moved to San Francisco and called their group the Wicked Crew. The Wicked Crew’s dance sound transmitted UK styles to the US, which helped to trigger the birth of the US west coast’s rave scene.[90]

The manager of Manchester’s Factory nightclub and co-owner of The Haçienda, Tony Wilson, also promoted acid house culture on his weekly TV show. The UK midlands also embraced the late 1980s house scene with illegal parties and raves and more legal dance clubs such as The Hummingbird.[91]

Chicago’s second wave: Hip house and ghetto house[edit]

While the acid house hype spawned in the UK and Europe, in Chicago it reached its peak around 1988 and then declined in popularity.[citation needed] Instead, a crossover of house and hip-hop music, known as hip house, became popular. Tyree Cooper’s single «Turn Up the Bass» featuring Kool Rock Steady from 1988 was an influential breakthrough for this subgenre, although the British trio the Beatmasters claimed having invented the genre with their 1986 release «Rok da House».[92] Another notable figure in the hip house scene was Fast Eddie with «Hip House» and «Yo Yo Get Funky!» (both 1988). Even Farley «Jackmaster» Funk engaged in the genre, releasing «Free at Last», a song to free James Brown from jail that featured The Hip House Syndicate, in 1989, and producing a Real Hip House compilation on his label, House Records, in 1990.[93]

The early 1990s saw new Chicago house artists emerge, such as Armando Gallop, who had released seminal acid house records since 1987, but became even more influential by co-founding the new Warehouse nightclub in Chicago (on 738 W. Randolph Street[94]) in which he also was resident DJ from 1992 until 1994, and founding Warehouse Records in 1988.[95]

Another important figure during the early to mid-1990s and until the 2000s was DJ and producer Paul Johnson, who released the Warehouse-anthem «Welcome to the Warehouse» on Armando’s label in 1994 in collaboration with Armando himself.[96] He also had part in the development of an entirely new kind of Chicago house sound, «ghetto house», which was prominently released and popularized through the Dance Mania record label. It was originally founded by Jesse Saunders in 1985 but passed on to Raymond Barney in 1988. It featured notable ghetto house artists like DJ Funk, DJ Deeon, DJ Milton, Paul Johnson and others. The label is regarded as hugely influential in the history of Chicago house music, and has been described as «ghetto house’s Motown».[97]

One of the prototypes for Dance Mania’s new ghetto house sound was the single «(It’s Time for the) Percolator» by Cajmere, also known as Green Velvet, from 1992.[98] Cajmere started the labels Cajual Records and Relief Records, the latter combining the sound of Chicago, acid, and ghetto house with the harder sound of techno. By the early 1990s, artists of note on those two labels included Dajae, DJ Sneak, Derrick Carter, DJ Rush, Paul Johnson, Joe Lewis, and Glenn Underground.

New York and New Jersey: Garage house and the «Jersey sound»[edit]

While house became popular in UK and continental Europe, the scene in the US had still not progressed beyond a small number of clubs in Chicago, Detroit, New York City, and Newark. In New York and Newark, the terms «garage house», «garage music», or simply «garage», and «Jersey sound», or «New Jersey house», were coined for a deeper, more soulful, R&B-derived subgenre of house that was developed in the Paradise Garage nightclub in New York City and Club Zanzibar in Newark, New Jersey, during the early-to-mid 1980s. It is argued that garage house predates the development of Chicago house, as it is relatively closer to disco than other dance styles.[99] As Chicago house gained international popularity, New York and New Jersey’s music scene was distinguished from the «house» umbrella.[99][100]

In comparison to other forms of house music, garage house, and Jersey sound include more gospel-influenced piano riffs and female vocals.[101] The genre was popular in the 1980s in the United States and in the 1990s in the United Kingdom.[101] DJs playing it include Tony Humphries at Club Zanzibar, Larry Levan, who was resident DJ at the Paradise Garage from 1977 to 1987, Todd Terry, Kerri Chandler, Masters at Work, Junior Vasquez, and others.[102]

In the late 1980s, Nu Groove Records launched and nurtured the careers of Rheji Burrell and Rhano Burrell, collectively known as Burrell (after a brief stay on Virgin America via Timmy Regisford and Frank Mendez). Nu Groove also had a stable of other NYC underground scene DJs. The Burrells created the «New York Underground» sound of house, and they did more than 30 releases on this label featuring this sound.

The emergence of New York’s DJ and producer Todd Terry in 1988 demonstrated the continuum from the underground disco approach to a new and commercially successful house sound. Terry’s cover of Class Action’s «Weekend» (mixed by Larry Levan) shows how Terry drew on newer hip-hop influences, such as the quicker sampling and the more rugged basslines.[103][citation needed]

Ibiza[edit]

House was also being developed by DJs and record producers in the booming dance club scene in Ibiza, notably when DJ Alfredo, the father of Balearic house, began his residency at Amnesia in 1983.[when?] While no house artists or labels came from Ibiza at the time, mixing experiments and innovations done by Ibiza DJs helped to influence the house style. By the mid-1980s, a distinct Balearic mix of house was discernible. Several influential clubs in Ibiza, such as Amnesia, with DJ Alfredo at the decks, were playing a mix of rock, pop, disco, and house. These clubs, fuelled by their distinctive sound and copious consumption of the club drug Ecstasy (MDMA), began to influence the British scene. By late 1987, DJs such as Trevor Fung, Paul Oakenfold and Danny Rampling were bringing the Ibiza sound to key UK clubs such as the Haçienda in Manchester. Ibiza influences also spread to DJs working London clubs, such as Shoom in Southwark, Heaven, Future, and Spectrum.[104]

Other regional scenes[edit]

This photo of a deep house DJ shows the pair of turntables and the DJ mixer in between.

By the late 1980s, house DJing and production had moved to the US’s west coast, particularly to San Francisco, Oakland, Los Angeles, Fresno, San Diego, and Seattle. Los Angeles saw an explosion of underground raves, where DJs mixed dance tracks. Los Angeles DJs Marques Wyatt and Billy Long spun at Jewel’s Catch One. In 1989, the Los-Angeles-based former EBN-OZN singer/rapper Robert Ozn started indie house label One Voice Records. Ozn released the Mike «Hitman» Wilson remix of Dada Nada’s «Haunted House», which garnered club and mix show radio play in Chicago, Detroit, and New York as well as in the UK and France. The record went up to number five on the Billboard Club Chart, marking it as the first house record by a white (Caucasian) artist to chart in the US. Dada Nada, the moniker for Ozn’s solo act, did his first releases in 1990, using a jazz-based deep house style. The Frankie Knuckles and David Morales remix of Dada Nada’s «Deep Love» (One Voice Records in the US, Polydor in the UK), featuring Ozn’s lush, crooning vocals and jazzy improvisational solos by muted trumpet, underscored deep house’s progression into a genre that integrated jazz and pop songwriting and song forms (unlike acid house and techno).[citation needed] The Twilight Zone (1980–89) located on Richmond Street in Toronto’s entertainment district was the first after hours club to regularly feature New York and Chicago DJs that first spun house music in Canada.[105] The venue was the first international gig destination for both Frankie Knuckles and David Morales. One of the club’s owners, Tony Assoon, would make regular trips to New York in order to purchase funk, underground disco and house records to play on his regular Saturday night slot.[106]

The Montreal Scene

Historically deeply influenced by musical trends coming from England, France, and the US, Montreal has developed a distinct house music scene.

Shaped more specifically by the impact of UK’s techno scene,[107] France’s French Touch movement, and American DJs and club owners such as Angel Moraes,[108] David Morales,[109] and Danny Tenaglia,[110] the city has evolved to become a distinct dance music hub.[111]

Ever since the middle of the 1990s and early 2000s, an ever-growing number of house music festivals take place in the city throughout the year, including Igloofest, Nuit blanche, Piknic Electronik, Mutek, Ile Soniq, Montréal Pride, and the Black and Blue festival.

1990s[edit]

In 1990, Italo house group Black Box’s big hit «Everybody Everybody» reached US Billboard Hot 100.[112]

In Britain, further experiments in the genre boosted its appeal. House and rave clubs such as Lakota and Cream emerged across Britain, hosting house and dance scene events. The ‘chilling out’ concept developed in Britain with ambient house albums such as The KLF’s Chill Out and Analogue Bubblebath by Aphex Twin. The Godskitchen superclub brand also began in the midst of the early 1990s rave scene. After initially hosting small nights in Cambridge and Northampton, the associated events scaled up at the Sanctuary Music Arena in Milton Keynes, in Birmingham, and in Leeds. A new indie dance scene also emerged in the 1990s. In New York, bands such as Deee-Lite, with Bootsy Collins, furthered house’s international influence.

In England, one of the few licensed venues was the Eclipse, which attracted people from up and down the country as it was open until the early hours. Due to the lack of licensed, legal dance event venues, house music promoters began organising illegal events in unused warehouses, aeroplane hangars, and in the countryside. The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 was a government attempt to ban large rave dance events featuring music with «repetitive beats», due to law enforcement allegations that these events were associated with illegal club drugs. There were a number of «Kill the Bill» demonstrations by rave and electronic dance music fans. The Spiral Tribe dance event at Castle Morten was the last of these illegal raves, as the bill, which became law in November 1994, made unauthorised house music dance events illegal in the UK. Despite the new law, the music continued to grow and change, as typified by Leftfield with «Release the Pressure», which introduced dub and reggae into the house sound.

A new generation of clubs such as Liverpool’s Cream and the Ministry of Sound were opened to provide a venue for more commercial house sounds. Major record companies began to open «superclubs» promoting their own groups and acts. These superclubs entered into sponsorship deals initially with fast food, soft drink, and clothing companies. Flyers in clubs in Ibiza often sported many corporate logos from sponsors. A new subgenre, Chicago hard house, was developed by DJs such as Bad Boy Bill, DJ Lynnwood, DJ Irene, and Richard «Humpty» Vission, mixing elements of Chicago house, funky house, and hard house. Additionally, producers such as George Centeno, Darren Ramirez, and Martin O. Cairo developed the Los Angeles Hard House sound. Similar to gabber or hardcore techno from the Netherlands, this was associated with the «rebel», underground club subculture of the time.

Towards the end of the 1990s and into the 2000s, French DJ/producers such as Daft Punk, Bob Sinclar, Stardust, Cassius, St. Germain and DJ Falcon began producing a new sound in Paris’ club scene. Together, they laid the groundwork for what would be known as the French house movement. They combined the harder-edged-yet-soulful philosophy of Chicago house with the melodies of obscure funk records. By using new digital production techniques blended with the retro sound of old-school analog synthesizers, they created a new sound and style that influenced house music around the world.[113]

2000s[edit]

Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley proclaimed 10 August 2005 to be «House Unity Day» in Chicago, in celebration of the «21st anniversary of house music» (actually the 21st anniversary of the founding of Trax Records, an independent Chicago-based house label). The proclamation recognized Chicago as the original home of house music and that the music’s original creators «were inspired by the love of their city, with the dream that someday their music would spread a message of peace and unity throughout the world». DJs such as Frankie Knuckles, Marshall Jefferson, Paul Johnson, and Mickey Oliver celebrated the proclamation at the Summer Dance Series, an event organized by Chicago’s Department of Cultural Affairs.[114]

It was during this decade that vocal house became firmly established, both in the underground and as part of the pop market, and labels such as Defected Records, Roulé, and Om were at the forefront of the emerging sound. In the mid-2000s, fusion genres such as electro house and fidget house emerged.[citation needed] This fusion is apparent in the crossover of musical styles by artists such as Dennis Ferrer and Booka Shade, with the former’s production style having evolved from the New York soulful house scene and the latter’s roots in techno. Numerous live performance events dedicated to house music were founded during the course of the decade, including Shambhala Music Festival and major industry sponsored events like Miami’s Winter Music Conference. The genre even gained popularity through events like Creamfields. In the late 2000s, house style witnessed renewed chart success thanks to acts such as Daft Punk, Deadmau5, Fedde Le Grand, David Guetta, and Calvin Harris.[citation needed]

2010s[edit]

During the 2010s, multiple new sounds in house music were developed by DJs, producers, and artists. Sweden pioneered the «Festival progressive house» genre with the emergence of Sebastian Ingrosso, Axwell, and Steve Angello. While all three artists had solo careers, when they formed a trio called Swedish House Mafia, it showed that house could still produce chart-topping hits, such as their 2012 single «Don’t You Worry Child», which cracked the Billboard top 10. Avicii was a Swedish DJ/artist known for his hits such as «Hey Brother», «Wake Me Up», «Addicted to You», «The Days», «The Nights», «Levels», «Waiting for Love», «Without You», and «I Could Be the One» with Nicky Romero. Fellow Swedish DJ/artist Alesso collaborated with Calvin Harris, Usher, and David Guetta.[115] In France, Justice blended garage and alternative rock influences into their pop-infused house tracks, creating a big and funky sound.

During the 2010s, in the UK and in the US, many records labels stayed true to the original house music sound from the 1980s. It includes labels like Dynamic Music, Defected Records, Dirtybird, Fuse London, Exploited, Pampa, Cajual Records, Hot Creations, Get Physical, and Pets Recordings.[116]

From the Netherlands coalesced the concept of «Dirty Dutch», an electro house subgenre characterized by abrasive lead synths and darker arpeggios, with prominent DJs being Chuckie, Hardwell, Laidback Luke, Afrojack, R3hab, Bingo Players, Quintino, and Alvaro. Elsewhere, fusion genres derivative of 2000s progressive house returned, especially with the help of DJs/artists Calvin Harris, Eric Prydz, Mat Zo, Above & Beyond, and Fonzerelli in Europe.[citation needed]

Diplo, a DJ/producer from Tupelo, Mississippi, blended underground sounds with mainstream styles. As he came from the southern US, Diplo fused house music with rap and dance/pop, while also integrating more obscure southern US genres. Other North Americans playing house music include the Canadian Deadmau5 (known for his unusual mask and unique musical style), Kaskade, Steve Aoki, Porter Robinson, and Wolfgang Gartner. The growing popularity of such artists led to the emergence of electro house and progressive house sounds in popular music, such as singles like David Guetta feat. Avicii’s «Sunshine»[117] and Axwell’s remix of «In The Air».[118][119]

Big room house became increasingly popular since 2010, through international dance music festivals such as Tomorrowland, Ultra Music Festival, and Electric Daisy Carnival. In addition to these popular examples of house, there has also been a reunification of contemporary house and its roots. Many hip hop and R&B artists also turned to house music to add a mass appeal and dance floor energy to the music they produce. Tropical house went onto the top 40 on the UK singles Chart in 2015 with artists such as Kygo and Jonas Blue. In the mid-2010s, the influences of house began to also be seen in Korean K-pop music, examples of this being f(x)’s single «4 Walls» and SHINee’s title track, «View».

Later in the 2010s, a more traditional house sound came to the forefront of the mainstream in the UK, with Calvin Harris’s singles «One Kiss» and «Promises», with the latter also incorporating elements of nu-disco and Italo house. These singles both went to No.1 in the UK.[120][121]

2020s[edit]

In the late 2010s and early 2020s, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic,[122][123] the South African offshoot of house music, called amapiano, became popular first in South Africa, and then later spread to London and elsewhere worldwide, largely due to online music distribution.[124] Amapiano draws heavily from earlier kwaito house music of South Africa and from jazz and chill-out music.[125] In 2022, the music portal Beatport added an «amapiano» genre to its catalogue.[126]

During the late 2010s and early 2020s and partially due to YouTube music channels, closely related house subgenres Brazilian bass and slap house became popular worldwide, drawing from deep house and menacing basslines of tech house.[127][128]

In 2020, American singer Lady Gaga released Chromatica, which was her return to her dance roots towards deep house, french house, electro house, and disco house.[129][130]

In 2022, Canadian rapper Drake released Honestly, Nevermind, which was a departure from his signature hip hop, R&B, and trap music sound, and moved towards house music and its derivativates: Jersey club, amapiano,[131][132] and ballroom.[133] American singer Beyoncé’s album Renaissance, also released in 2022, incorporated ballroom house.

See also[edit]

- List of electronic music genres

- List of house music artists

- Styles of house music

- Music of the United States

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g «House Music Genre Overview — AllMusic». AllMusic. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ Fritz, Jimi (2000). Rave Culture: An Insider’sOverview. SmallFry Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780968572108.

- ^ «Explore music … Genre: Hi-NRG». AllMusic. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ^ Gilbert, Jeremy; Pearson, Ewan (2002). Discographies: Dance, Music, Culture and the Politics of Sound. Routledge. p. ??. ISBN 9781134698929.

- ^ Langford, Simon (2014). The Remix Manual: The Art and Science of Dance Music Remixing with Logic. CRC Press. p. 99. ISBN 9781136114625.

- ^ Walters, Barry (1986): Burning Down the House Archived 5 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine. SPIN magazine. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ Malnig, Julie (2009). Ballroom, Boogie, Shimmy Sham, Shake: A Social and Popular Dance Reader. University of Illinois Press. p. 213. ISBN 9780252075650.

- ^ a b c Vincent, Rickey (4 November 2014). Funk: The Music, The People, and The Rhythm of The One. St. Martin’s Griffin. ISBN 9781466884526. Archived from the original on 25 December 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ «Jesse Saunders — On And On». Discogs. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ «Tempo and genre | Learning Music (Beta)». learningmusic.ableton.com. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Fikentscher, Kai (July–August 2000). «The Club DJ: A Brief History of a Cultural Icon» (PDF). UNESCO Courier. UNESCO: 47. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

Around 1986/7, after the initial explosion of house music in Chicago, it became clear that the major recording companies and media institutions were reluctant to market this genre of music, associated with gay African Americans, on a mainstream level. House artists turned to Europe, chiefly London but also cities such as Amsterdam, Berlin, Manchester, Milan, Zurich, and Tel Aviv. … A third axis leads to Japan where, since the late 1980s, New York club DJs have had the opportunity to play guest-spots.

- ^ Rick Snoman, Dance Music Manual: Tools, Toys, and Techniques, page 267 Archived 26 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, CRC Press

- ^ a b c Hydlide (12 October 2016). «Basic Elements: House Music». www.reasonexperts.com. Reason. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

Reasonexperts Propellerhead Reason tutorials made by Hydlide

- ^ Acland, Charles R. (2007). Residual Media . Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816644728. Quote: «The legacy of musical adventures with Latin dance music can still be heard in, for example, the dominance of salsa clave rhythms in the riffs of house music.»

- ^ a b c d e f g Rietveld, Hillegonda C. (1998). This is our House: House Music, Cultural Spaces and Technologies, Aldershot Ashgate. Reissue: London/New York: Routledge 2018/2020. ISBN 036713411X. Cited from online book preview Archived 8 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, 20 January 2020.

- ^ a b Warwick, Oli (2 April 2019). «House music changed clubbing forever. From disco to footwork, via Frankie Knuckles, Mr Fingers and techno, here are the basics you need to know before stepping onto the dancefloor». www.redbull.com. Red Bull. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Kernodle, Tammy Lynn; Maxile, Horace Joseph. Encyclopedia of African American Music, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO, 2011. p. 406

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kernodle, Tammy Lynn; Maxile, Horace Joseph. Encyclopedia of African American Music, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO, 2011. p. 405

- ^ a b Gerstner, David A. (2012). Routledge International Encyclopedia of Queer Culture. Routledge. p. 154. ISBN 9781136761812.

- ^ Inglis, Sam (November 2004). «Secrets Of House & Trance Darren Tate’s Production Tips». /soundonsound.com. Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ a b Snoman, Rick (2009). The Dance Music Manual: Tools, Toys, and Techniques — Second Edition. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Press. p.233

- ^ «House». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

- ^ Rule, Greg (August 1997). «The Father of Chicago House». Keyboard. 23 (8): 65.

- ^ a b c Horn, David, ed. (2012). Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World: Genres: North America. The Continuum International Publishing Group. doi:10.5040/9781501329203-0014040. ISBN 978-1-5013-2920-3.

- ^ Comm, The MO Amper; Says, Er. «House Music in Chicago». Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ «Frankie Knuckles on the Birth of House Music». daily.redbullmusicacademy.com. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ «Phil Ranstrom — Contact Info, Agent, Manager | IMDbPro». pro.imdb.com. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ «Vimeo». vimeo.com. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Frankie Knuckles (featured subject); Hindmarch, Carl (director) (2001). Pump Up The Volume (Television production). Channel Four.

- ^ Arnold, Jacob (7 January 2010). «Leonard «Remix» Rroy, Chicago’s Unsung House DJ». gridface. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2011.

- ^ Fleming, Jonathan (1995). What Kind Of House Party Is This. London: MIY Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-9523932-1-4.

- ^ Bidder, Sean (2001). Pump Up the Volume: A History of House. London: Channel 4. ISBN 978-0-7522-1986-8.

- ^ Chip E. (interviewee); Hindmarch, Carl (director) (2001). Pump Up The Volume (Television production). Channel Four.

If you were a DJ in Chicago, if you wanted to have ‘the’ records, there was only one place to go and that was Importes. This is where Importes was. People come in, they’re looking for ‘Warehouse music’, and we would put, you know, ‘As heard at the Warehouse’ or ‘As played at the Warehouse’, and then eventually we just shortened that down to – because people also just in the vernacular, they started saying ‘yeah, what’s up with that ‘House music’ – now at this time they were talkin’ about the old, old classics, the Salsoul, the Philly classics and such – so we put on the labels for the bins, we’d say ‘House music’. And people would start comin’ in eventually and just start askin’, ‘yeah, where’s the new House music?’

- ^ George, Nelson (21 June 1986). «House Music: Will It Join Rap And Go-Go?». Billboard. Vol. 99, no. 25. p. 27. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

The term ‘house music’ has become a generic phrase for modern dance-oriented music,» says Jones. «At one time the phrase ‘old house music’ was used to refer to old disco music. Now ‘house’ is used to describe the new music.

- ^ Bainbridge, Luke (22 February 2014). «Acid house and the dawn of a rave new world». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ «larry heard equipment from 1992». www.oldschooldaw.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ Cowen, Andrew (30 October 1999). «Sounds Amazing!; Music Live Andrew Cowen previews the giant show at the NEC which offers great new ideas for musicians of all styles and all levels». The Birmingham Post (UK). Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- ^ Trask, Simon (December 1988). «Future Shock (Juan Atkins Interview)». Music Technology Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 March 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

The word ‘house’ comes from a record that you only hear in a certain club. The DJs would search out an import that was as obscure as possible, and that would be a house record. You’d hear a certain record only at the Powerplant, and that was Frankie Knuckles’ house record. But you couldn’t really be guaranteed an exclusive on an import, ‘cos even if there were only 10 or 15 copies in the country, another DJ would track one down. So the DJs came up with the concept of making their own house records. It was like ‘hey, I know I’ve got an exclusive because I made the record.

- ^ «House Dance». mywaydance.com. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Apolonia and Ofilio (7 June 2011). «What is HOUSE DANCE — House Dancing roots, history and key dancers». GADFLY. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ a b «🥁 House — slurp documentation». slurp.readthedocs.io. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ Turtoga, Jomarie. «Dance.docx».

- ^ a b c Reynolds, Simon (1999) [1998]. Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of House Music and Rave Culture. Routledge. pp. 27–31.

- ^ «A Brief History of House Music». complex.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ (C) (4 October 2007). «Understanding House Music». laist.com. LAist. Archived from the original on 6 November 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Caswell, Estelle (16 July 2019). «How Chicago built house music from the ashes of disco». Vox. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ «House». www.allmusic.com. AllMusic. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Rogers, Jude. «Why Kraftwerk are still the world’s most influential band». The Observer. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ «Cerrone Bio». Beatport. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ Yellow Magic Orchestra at AllMusic

- ^ Solid State Survivor at AllMusic

- ^ RBMA (2011): Frankie Knuckles: A journey to the roots of house music. Red Bull Music Academy. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ «House Roots». 2021.

- ^ Brewster, Bill (2014). «Ron Hardy, Chicago Legend—If Frankie Knuckles is the Godfather of House, Ron Hardy was its Baron Frankenstein», Djhistory.com, 2014-06-01. «Ron Hardy, Chicago Legend | DJhistory.com». Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ «History of House Music». Housegroove.net. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ Burgess, Richard James (17 August 2014). The History of Music Production. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199357178. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Pattison, Louis (10 April 2010). «Charanjit Singh, acid house pioneer». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Aitken, Stuart (10 May 2011). «Charanjit Singh on how he invented acid house … by mistake». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ William Rauscher (12 May 2010). «Charanjit Singh – Synthesizing: Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat». Resident Advisor. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Manzo, V. J.; Kuhn, Will. Interactive Composition: Strategies Using Ableton Live and Max for Live.

Oxford University Press, 23 January 2014. p. 134. - ^ Roy, Ron; Borthwick, Stuart (2004). Popular Music Genres: An Introduction. Edinburgh University Press. p. 255. ISBN 9780748617456.

- ^ Church, Terry (9 February 2010). «Black History Month: Jesse Saunders and house music». BeatPortal. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ^ Mitchell, Euan. Interviews: Marshall Jefferson www.4clubbers.net[dead link]

- ^ «Finding Jesse – The Discovery of Jesse Saunders As the Founder of House». Fly Global Music Culture. 25 October 2004. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Paoletta, Michael (16 December 1989). «Back To Basics». Dance Music Report: 12.

- ^ Graves, Richard (23 April 2015). «History of House: What Was The First HOUSE MUSIC SONG Released in Chicago?». The History of House. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ «house». Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ^ Fikentscher, Kai (July–August 2000). «Youth’s sonic forces: The club DJ: a brief history of a cultural icon» (PDF). UNESCO Courier. UNESCO: 28. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

House music, in particular, is often held up as a kind of banner of cultural diversity owing to its origins in black and Latin discos, where it first found its audience. One could point to the 1980s, when African American producers / DJs, like Frankie Knuckles, Marshall Jefferson or DJ Pierre, began refining the all night dance floor workouts at underground gay and mixed clubs like the legendary Warehouse club in Chicago from which house music derives its name. Or there is DJ Larry Levan, whose residence at New York’s Paradise Garage not only defined a distinct subgenre of its own («garage» is slower and more gospel oriented than «house») but set the tone for today’s raves—no alcohol, heavy drug use, a mixed, «up for it crowd» and loud, pulsating music for 15-hour stretches without a break.

- ^ Melville, Caspar (July–August 2000). «Mapping the meanings of dance music» (PDF). UNESCO Courier. UNESCO: 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

house music was born in the black-latino urban gay clubs of the U.S.

- ^ Fikentscher, Kai (July–August 2000). «The club DJ: a brief history of a cultural icon» (PDF). UNESCO Courier. UNESCO: 46. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

Another New York DJ, Frankie Knuckles, moved to Chicago, following an invitation to become the resident DJ at the Warehouse, a gay black club.

- ^ George, Nelson (21 June 1986). «House Music: Will It Join Rap And Go-Go?». Billboard. Vol. 99, no. 25. p. 27. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

The initial audience started out black and gay in Chicago, but the genre has since attracted Mexicans and whites as well.

- ^ Creekmur, Corey; Doty, Alexander (1995). Out in Culture. Duke University Press. pp. 440–442. ISBN 978-0-8223-1541-4.

- ^ Review by Alain_Patrick on Discogs; Interview with DJ Pierre Archived 8 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine in Fader magazine, 4 August 2014.

- ^ Iqbal, Mohson (31 January 2008). «Larry Heard: Soul survivor». Resident Advisor. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie (1999). Music USA: The Rough Guide. London: Rough Guides. p. 265. ISBN 978-1-85828-421-7. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ Shapiro, Peter (2000). Modulations: A History of Electronic Music. Caipirinha Productions Inc. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8195-6498-6.

- ^ Interview with Phuture’s DJ Pierre Archived 29 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine in DJ mag, 2014.

- ^ Review by Alain_Patrick Archived 8 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine on Discogs; Interview with DJ Pierre Archived 8 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine in Fader Magazine, 4 August 2014.

- ^ Cheeseman, Phil. «The History Of House Archived 2013-09-06 at the Wayback Machine».

- ^ Jacob Arnold (2017). «When Techno Was House: Jacob Arnold looks at Chicago’s impact on the birth of techno». Red Bull Music Academy Daily. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ Juan Atkins on Kraftwerk Archived 30 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine, on Electronic Beats, 2012 (retrieved on 26 July 2020).

- ^ Bishop, Marlon; Glasspiegel, Wills (14 June 2011). «Juan Atkins [interview for Afropop Worldwide]». World Music Productions. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011. «Neil Rushton came up with the idea to do a compilation for Virgin and call it The House Sound of Detroit. And my track that I put on this record was called ‘Techno Music.’ And they were like ‘wait a minute, if he’s deeming this record ‘Techno Music’ and all the rest of this stuff is similar sounding, let’s call it Techno: The New Dance Sound of Detroit.’ And hence, that album was released and the name stuck.»

- ^ On the influence of Chicago house on Derrick May, who says to have been musically «baptised by Ron Hardy», see «Interview: Derrick May – The Secret of Techno (archived)». Mixmag. 1997. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) The connection was two-sided, as Chicago’s house DJ Frankie Knuckles played the song in his club and even suggested its title (see also there). - ^ Derrick May — Strings of Life Archived 26 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine on Attack Magazine, 2018 (retrieved on 26 July 2020).

- ^ Savage, Jon (21 February 2009). «The history of the smiley face symbol». The Guardian. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ «love can’t turn around | full Official Chart History | Official Charts Company». www.officialcharts.com. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ «Best selling singles of the 80s». Pure80spop.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ «Chart Archive – 1980s Singles». EveryHit.com. Archived from the original on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ Matos, Michaelangelo (6 December 2011). «Remembering Larry Levan, ‘The Jimi Hendrix Of Dance Music’«. NPR. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Magnetic. «The Rave Pioneers: Catching Up With San Francisco’s Wicked Sound System». Magnetic Magazine. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ «Clubbing and raving back in the day | The Voice Online». archive.voice-online.co.uk. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Duthel, C. (5 March 2012). Pitbull — Mr. Worldwide. ISBN 9781471090356. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Farley Jackmaster Funk: Artist page Archived 19 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine on Discogs.

- ^ Armando Gallop: Live at the Warehouse DJ Mix Archived 26 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine on 5mag.com.

- ^ Biography of Armando Archived 26 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine on AllMusic, retrieved on 27 Juli 2020.

- ^ Paul Johnson: Scene #001, release page Archived 13 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine on Discogs.

- ^ Arnold, Jacob (15 May 2013). «Dance Mania: Ghetto House’s Motown». Resident Advisor. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ «Cajmere «Percolator» | Insomniac». Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ a b «Garage». AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ^ Saunders, Jesse (2007). House Music: The Real Story. Publish America Baltimore. p. 118. ISBN 9781604740011.

New York did not truly develop a recognized House music scene of its own until 1988 with the success of DJ Todd Terry—not until then did they understand what House music truly was all about. They did, though, have Garage.

- ^ a b Verderosa, Tony (2002). The techno primer: the essential reference for loop-based music styles. U.S.: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2002. p. 36. ISBN 0634017888.

- ^ Sylvan, Robin (2002). Traces of the spirit: the religious dimensions of popular music. U.S.: NYU Press. p. 120. ISBN 0814798098.

- ^ «hip hop music: Hip-Hop Archives». www.hiphopmusic.com. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ «Acid house and the dawn of a rave new world». the Guardian. 23 February 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ «Phantom on The Dance Floor: A Brief History on Toronto’s Twilight Zone Club & How It Transformed a City Forever». 6 September 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ «Then & Now: Twilight Zone». Then and Now: Toronto Nightlife History. 16 September 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ «Montréal Rave: An Oral History». daily.redbullmusicacademy.com. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ «Angel Moraes music download — Beatport». www.beatport.com. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Wren, Dominic (8 June 2021). «David Morales — House Music, DJ Life, Montreal Connection». Funktasy. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ «18e Bal en blanc: 15 000 personnes dansent toute la nuit à Montréal». HuffPost. 9 April 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Billboard Staff (12 November 2015). «The 15 Greatest Dance Music Cities of All Time». Billboard. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ «Hot 100 – Year-End 1990». Billboard. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Prato, Paolo; Horn, David, eds. (2017). Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World: Genres: Europe. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. doi:10.5040/9781501326110-0186. ISBN 978-1-5013-2611-0.

- ^ «Chicago Mayor Declares ‘House Unity Day’«. Remix. Penton Media, Inc. 3 August 2005. Archived from the original on 17 September 2009.

- ^ ««My album is coming in the first quarter of 2015…» – hmv.com talks to Alesso». HMV. 18 November 2014. Archived from the original on 24 November 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ «13 OF THE MOST INFLUENTIAL HOUSE LABELS OF THE LAST DECADE». mixmag. 19 April 2017. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ «David Guetta, Deadmau5 Get EDM Some Grammy Shine». MTV. 2 October 2012. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ «Dirty South Teams Up With Axwell, Rudy For ‘Dreams’«. MTV. 22 March 2017. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ «Axwell’s Iconic Remix Of «In The Air» Turns 8 Years Old». We Rave You. 29 June 2017. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ McIntyre, Hugh. «Calvin Harris And Dua Lipa Rocket To No. 1 In The U.K. With ‘One Kiss’«. Forbes. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ McIntyre, Hugh. «Sam Smith And Calvin Harris Grab Yet Another No. 1 Hit In The U.K. With ‘Promises’«. Forbes. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ «South Africa: Amapiano, the dance soundtrack to Covid».

- ^ Brown, Daryl (15 February 2022). «Amapiano: How this South African sound has become one of the hottest new music genres — CNN». Edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Machaieie, Mario (21 October 2019). «2019 The Year Of The Yanos, How Amapiano Blow up». Online Youth Magazine | Zkhiphani.com. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ Prspct (21 November 2018). «New age house music: the rise of «amapiano»«. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ «Amapiano added as genre on Beatport». 11 May 2022.

- ^ By: admin (8 July 2020). «The rise of slap house». Melodicnation.co.uk. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ «Como surgiu o Slap House? Entenda melhor a vertente».

- ^ Spanos, Brittany (30 May 2020). «Welcome to ‘Chromatica’: Inside Lady Gaga’s Triumphant Dance Floor Return». Rolling Stone. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ Alessandra Armano (27 May 2020). «Was Lady Gaga Inspired by House Music on Her New Album ‘Chromatica’?». HOUSE of Frankie. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ «Drake: Honestly, Nevermind Album Review». Pitchfork. 22 June 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Joshi, Tara (17 June 2022). «Drake’s Honestly, Nevermind: best served tepid». New Statesman. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ Caramanica, Jon (19 June 2022). «Drake Rebuilt Hip-Hop in His Image. Now He Wants You to Dance». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

Further reading[edit]

- Bidder, Sean (2002). Pump Up the Volume: A History of House Music, London: MacMillan. ISBN 0-7522-1986-3

- Bidder, Sean (1999). The Rough Guide to House Music, Rough Guides. ISBN 1-85828-432-5

- Brewster, Bill/Frank Broughton (2000). Last Night a DJ Saved My Life: The History of the Disc Jockey, Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3688-5. UK edition: Headline 1999/2006.

- Fikentscher, Kai (2000). ‘You Better Work!’ Underground Dance Music in New York City. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0-8195-6404-4

- Hewitt, Michael (2008). Music Theory for Computer Musicians. 1st Ed. U.S. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-59863-503-4

- Kempster, Chris (Ed) (1996). History of House, Castle Communications. ISBN 1-86074-134-7 (A reprinting of magazine articles from the 1980s and 90s)

- Mireille, Silcott (1999). Rave America: New School Dancescapes, ECW Press. ISBN 1-55022-383-6

- Reynolds, Simon (1998). Energy Flash: a Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture, (UK title, Pan Macmillan. ISBN 0-330-35056-0), also released in U.S. as Generation Ecstasy : Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture, London/New York: Routledge 1999. ISBN 0-415-92373-5

- Rietveld, Hillegonda C. (1998). This is our House: House Music, Cultural Spaces and Technologies, Aldershot Ashgate. Reissue: London/New York: Routledge 2018/2020. ISBN 036713411X

- Shapiro, Peter (2000). Modulations: A History of Electronic Music: Throbbing Words on Sound. ISBN 1-891024-06-X.

- Snoman, Rick (2009). The Dance Music Manual: Tools, Toys, and Techniques — Second Edition: Chapter 11: House. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Press. p. 231–249.

External links[edit]

- Barry Walters: Burning Down the House. SPIN magazine, November 1986.

- Phil Cheeseman: The History of House. DJ Magazine (28 December 2003)

- Tim Lawrence: Acid ⎯ Can You Jack? – Liner notes on the early history of house (2005)

- Wilson: «If things go wrong, I just want you to know…«

- House: «If you’re going to say that you’ve always been secretly gay for me, everyone always just kind of assumed it.«

- — The C Word

The C-Word is an 8th season episode of House which first aired on April 30, 2012. When the team takes on the case of Emily, a six-year-old girl who has numerous preexisting health problems, they must work with her mother Elizabeth, who is a doctor who specializes in her daughter’s condition. The team must also deal with the battles raging between Emily’s mother and father who have conflicting views on how to handle her health issues. When searching the family’s home for clues to Emily’s illness, the team realizes that Elizabeth’s determination to cure her daughter could be the very thing that is killing her. Meanwhile, House and Wilson deal with Wilson’s stage two cancer at House’s apartment. Wilson feels that going forward with the more radical treatments first would be the best way to deal with it instead of dying a slow death, and this puts his life in jeopardy.

This is the second and last episode to be directed by Hugh Laurie, after he did it in the episode «Lockdown» (from season six).

Recap

A father and daughter are playing at an amusement park, and she wants to go on the merry-go-round by herself. Her father agrees on the condition she not tell her mother. However, as she goes around, her father notices that she’s looking woozy and developing a nosebleed. The next thing he knows, she’s missing. He shouts at them to stop the ride and jumps on it while it’s still moving to look for her. He finds her on the interior of the ride unconscious and screams for help.

1 The C Word On vacation

House finds Wilson in a lounge looking at scans of his thymoma. Wilson wonders how House found him, and House says he followed him there. Wilson says he doesn’t need another doctor, and House insists he’s there as a friend. He also notes that he’s tried to throw Wilson out several times when he wanted to be alone and it’s never worked. Wilson concedes and lets House stay after House promises not to give him any advice.

HOUSE — 2 The C Word The expert

Taub is wondering why House is taking time off for the first time in years, but Adams says it’s just because House wants to be there for Wilson. Taub is still skeptical. Foreman comes in with the case. The patient has two copies of the gene that causes ataxia telangiectasia. The other doctor, a developmental geneticist from Johns Hopkins Medical School who is with him explains that although she has symptoms of that condition, her presentation is different. Chase realizes the doctor is the patient’s mother, but she reassures them she’s there as a doctor, not her mother. Taub suggests her nosebleed and breathing problems are a complication of her telangiectasia, but the mother dismisses the suggestion as the patient is too young to be showing symptoms that severe. She also checked out the patient’s lungs two days before and she was fine. Adams guesses head trauma from the fall, but the mother dismisses that as well, saying if it were an easy diagnosis, she wouldn’t need them. Park suggests granulomatosis with polyangiitis and the mother agrees it’s a good fit. She goes to prepare the patient for an MRI because telangiectasia patients are sensitive to x-rays and walks out. The team is stunned by her behavior, but Foreman reassures them that she knows more about her daughter’s condition than anyone and that she will be an asset. Chase is sceptical, but Foreman tells them they have to work with her.

Wilson’s doctor is explaining they will have to give him radiation therapy before trying to remove the tumor with surgery because it has started to spread. However, Wilson realizes that with such conservative therapy, if the tumor doesn’t start to shrink by the time they try chemotherapy, it will be terminal. The doctor tries to reassure him that in 75% of cases like his, the radiation alone will destroy the tumor. Wilson counters that because the tumor has started to spread to surrounding tissue, it’s too late for radiation alone. He wants radiation and chemotherapy together. The doctor opposes this course of action because it will put too much of a stress on his immune system. Wilson says he’s getting a second opinion. The doctor counters that Wilson has recommended this exact course of action for dozens of his own patients, but Wilson gets up to leave and says he wants a doctor with «balls». The doctor asks House to speak to Wilson, but House backs Wilson. The doctor says that Wilson has to be more objective about his own treatment, but House agrees the doctor has no balls.

3 The C Word The other expert

The parents are arguing about the father having let the patient on the merry-go-round when Taub and Adams arrive. The mother goes to wake up the patient and gives her a toy penguin. Adams tries to make a joke about what «MRI» means, but the patient already knows what it means.

House is beating Wilson badly at combination of «Battleship» and «Beer Pong» and asks why Wilson freaked out with his oncologist. Wilson says it’s not freaking out to ask for a second opinion. However, House counters that Wilson should know his doctor was right and he should be in radiology, not looking for another doctor. He reminds Wilson that without treatment, the tumor will only get larger. Wilson says he doesn’t want House’s advice and walks out.

Adams and Taub do an MRI on the patient. She admits she was only pretending to sleep while her parents argued. Taub lies to the patient to tell her that he argues with his wife in front of his daughters all the time and they’re all fine. Adams wonders about the behavior of the patient’s mother. However, as Taub responds, the patient cries out in pain. As they get her out of the MRI, they note her fingers and toes are turning dark — the sign of there being no circulation. She calls out for her father.

They manage to restore circulation before there is any permanent damage. The team suggests the cold or stress could have set it off, but the mother becomes convinced that the father’s new apartment might be harboring heavy metals. She goes to do an environmental scan. However, Chase counters that lupus is probably more likely. The mother counters that she knows best as the patient’s mother, but Chase counters that she earlier said she was there as the patient’s doctor. She says that since they need her consent to treat the patient, it doesn’t matter. She tells them to start chelation therapy. When she leaves, Chase tells the team they have to start treating her like any other mother.

Chase and Adams do an environmental scan of the mother’s home. In the basement, they find an entire lab set up, full of hazardous chemicals and pharmaceuticals. Adams doesn’t think the mother would allow the patient down there, but Chase finds a playroom set up. They find a supply of LEX-2, an experimental antibiotic that is supposed to correct errors in the genes that cause ataxia telangiectasia. Adams thinks she must be testing it on lab rats, but Chase points out there is no sign of those and the only cage in sight is the playroom.

Wilson is in his office when House come in. Wilson has a headache and tries to send House away, but House wants to talk about second opinions. House has found that Wilson has seen four other doctors, all who have given him the same advice. He’s also found out that Wilson wants a dose of chemotherapy that has a good chance of killing him. House wondered why Wilson hadn’t told him, then realized it was because House would have tried to stop him and because Wilson had already found a doctor willing to co-operate, and the only doctor stupid enough to agree is Wilson himself. House opens a box and finds the chemotherapy drugs. The only thing House doesn’t know is where Wilson is planning on treating himself, and Wilson admits he stockpiled the equipment in his condo. House goes to destroy the chemotherapy drugs, but Wilson stops him. He argues that it’s better to take an extreme route while he’s still healthy. House counters that the therapy is about as likely to kill him as the thymoma, only faster revealing that Wilson is choosing either a complete cure or a fast death. Wilson goes through the gifts in his office from all the dead patients who had excellent chances of survival. He says he can’t stand the thought of dying slowly in a hospital. House calls him an idiot who is likely to die. He then agrees to do it at his apartment.

Foreman confronts the mother with the LEX-2 they found. She admits she used it on her daughter. She also insists the treatment is safe — she tested the drug on herself with no adverse effects, and because respiratory infections are common in AT patients, it is likely that Emily would not have survived the winter without it. However, Foreman counters that the FDA approves drugs for a reason. Another team has linked long-term use of LEX-2 to kidney failure in rodents. The patient needs a kidney biopsy.

At 221B Baker Street, they prepare Wilson for treatment. House starts off with a couple of martinis and a toast to stupidity. He also reminds Wilson about the side effects of the treatment. Wilson hands him the chemotherapy drugs.